Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

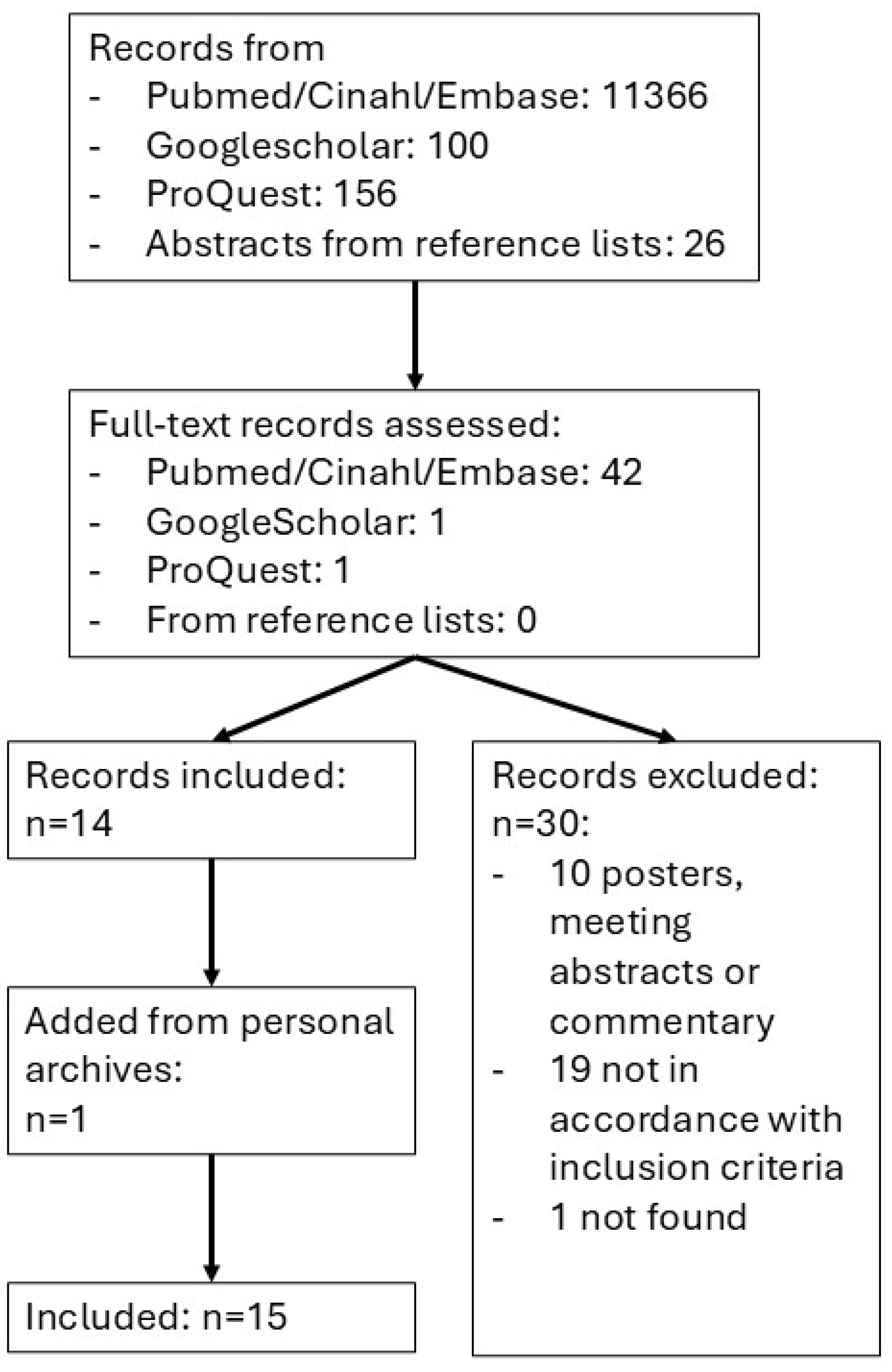

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Processing of Search Results and Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

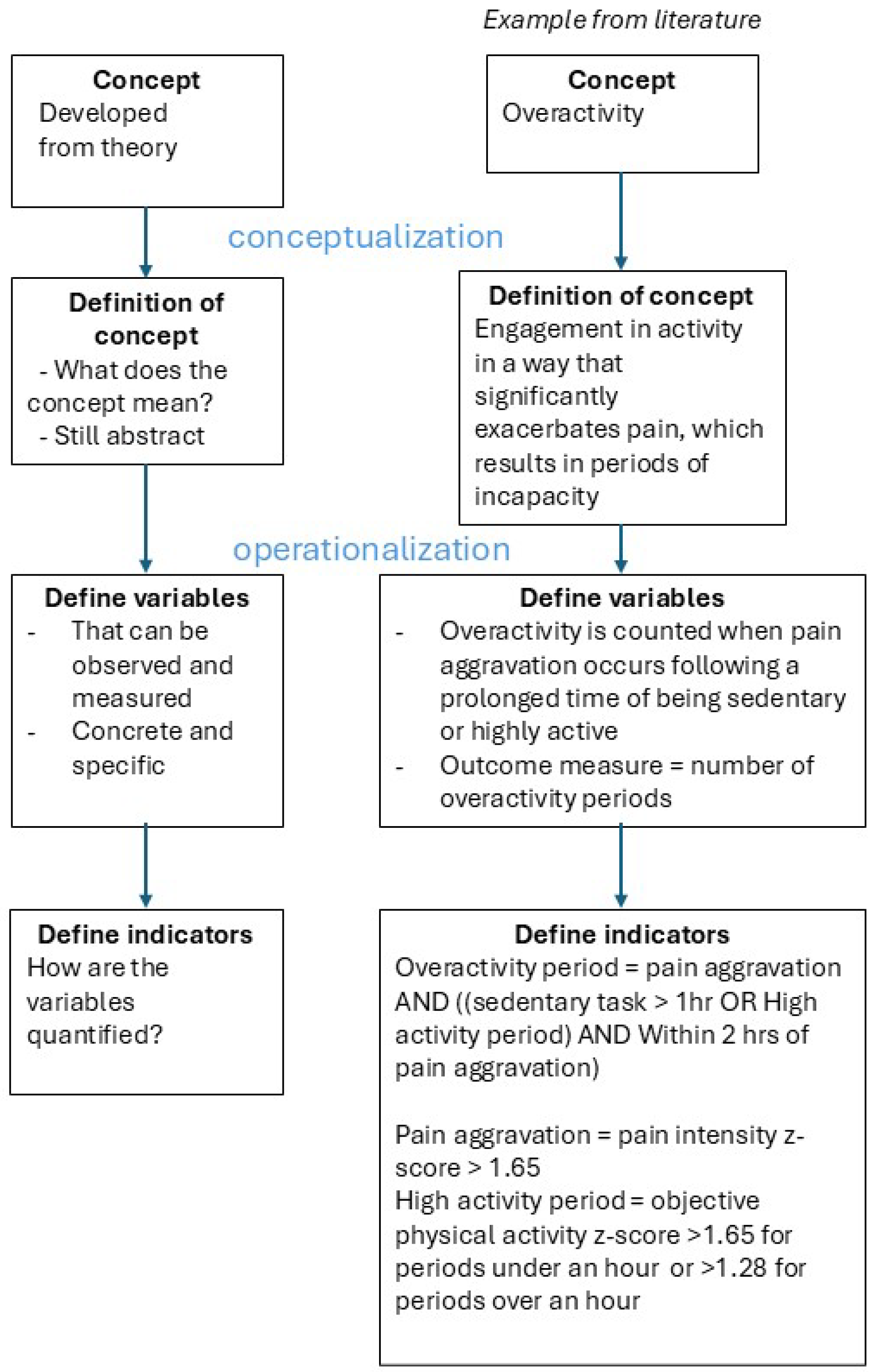

3.2. Concepts of Investigation, Definitions, Variables and Indicators

Concepts and Definitions (Conceptualization)

Variables and Indicators (Operationalization)

3.3. Measurement Properties and Data Processing

3.4. Validity of Conceptualization and Operationalization

Discussion and Conclusions

Recommendations

Strengths and Limitations

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | Activity patterns |

| CP | Chronic pain |

Appendix A. Search Strings

- Chronic pain

- Accelerometry

- NOT animals

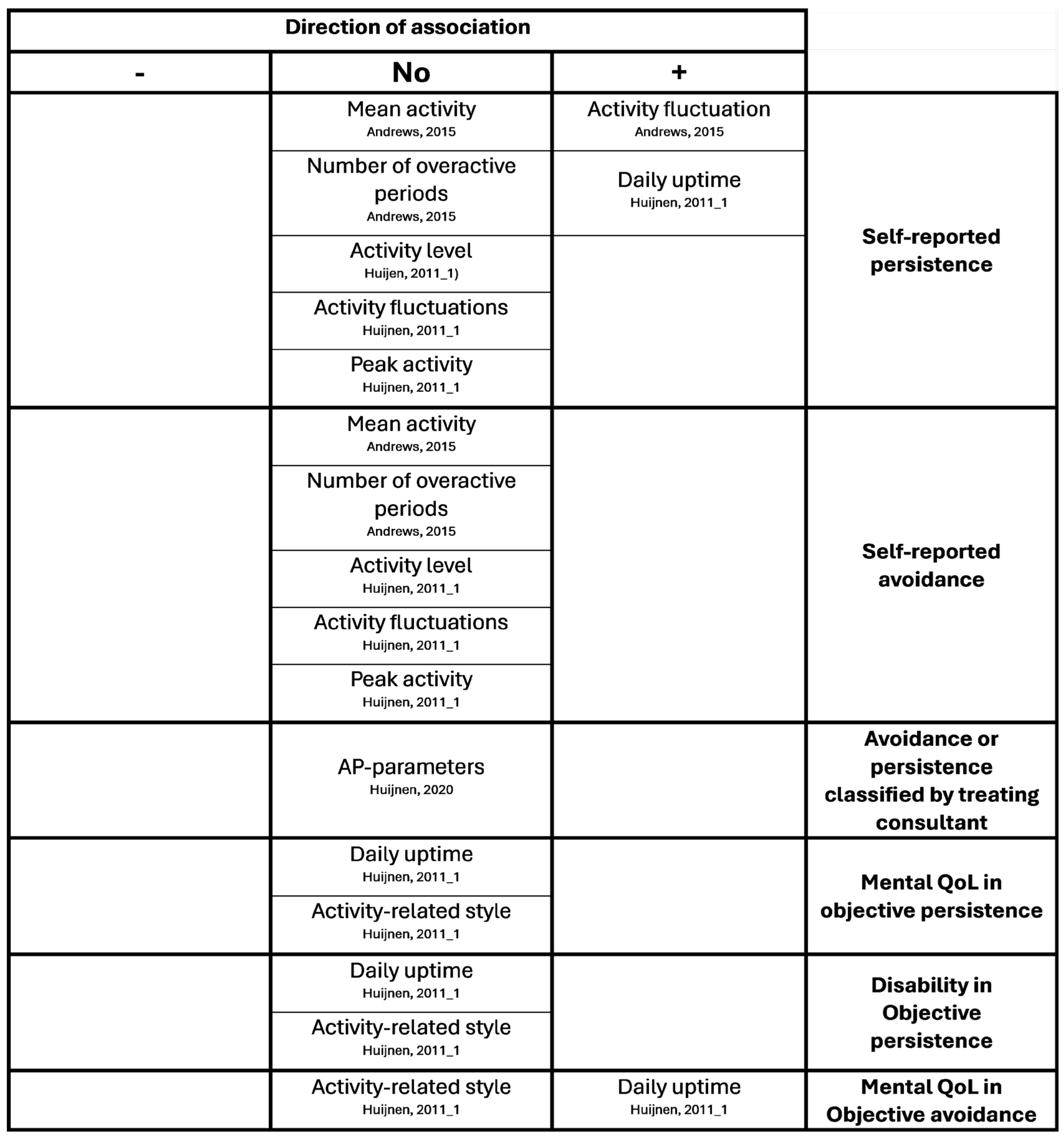

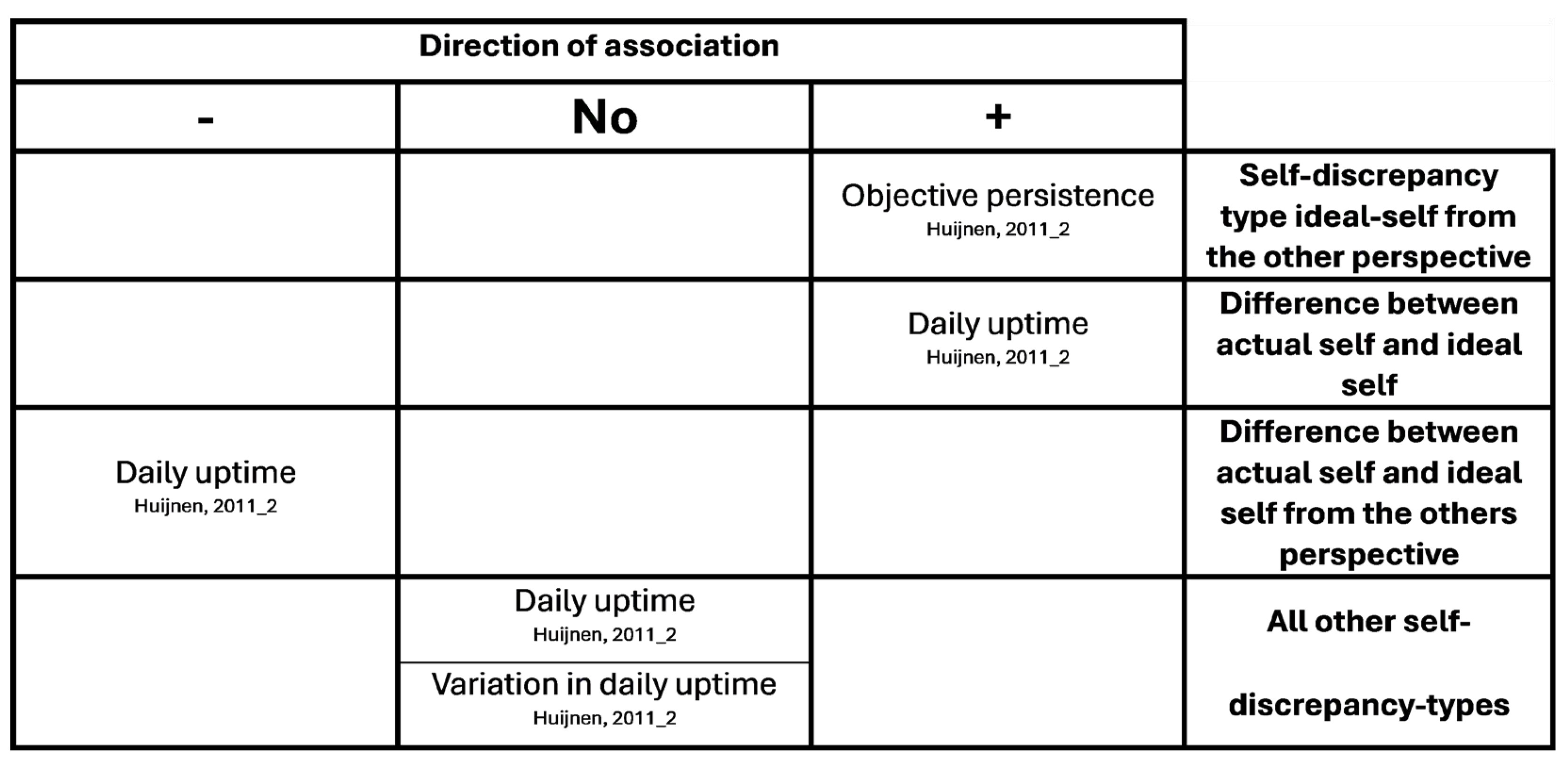

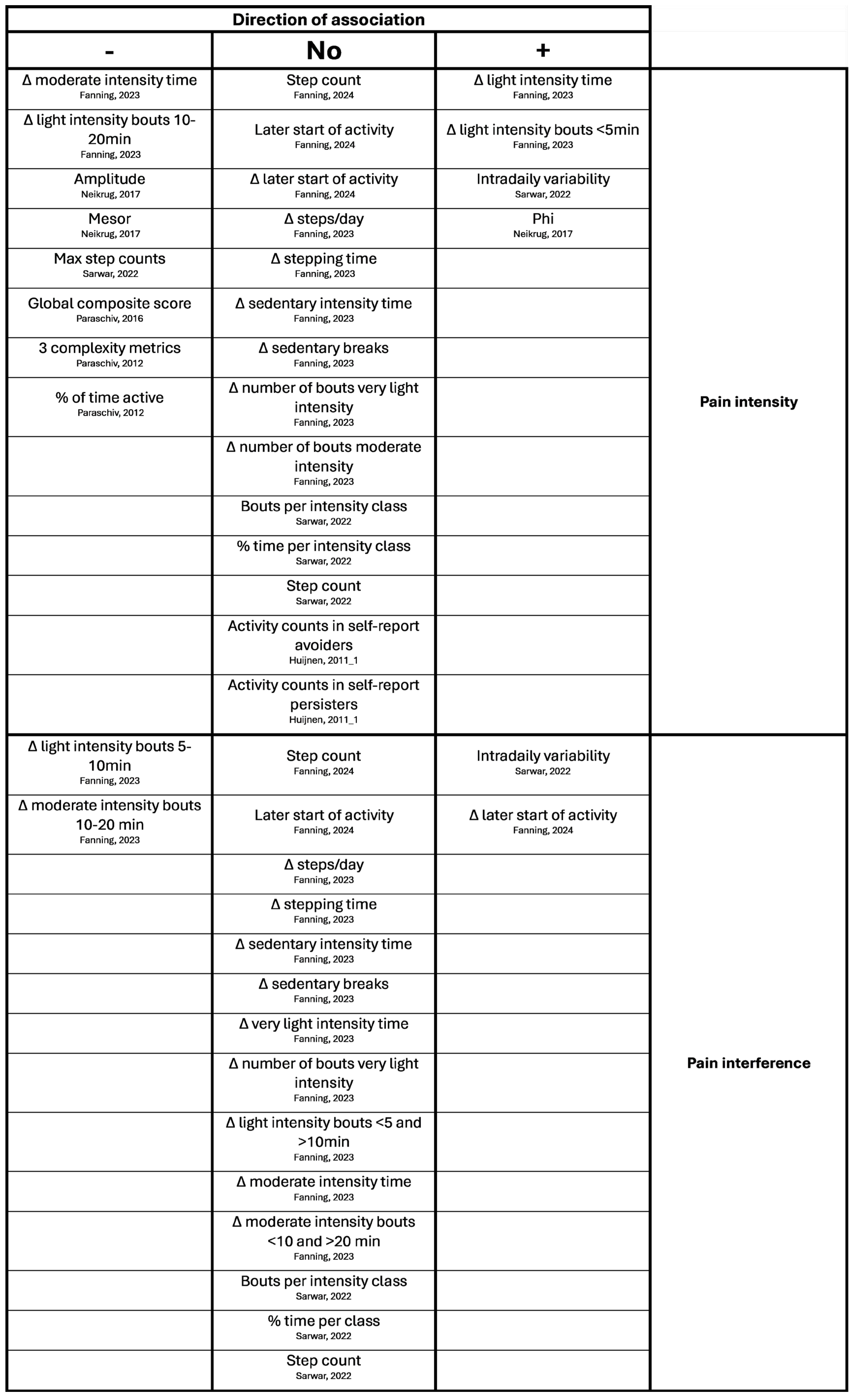

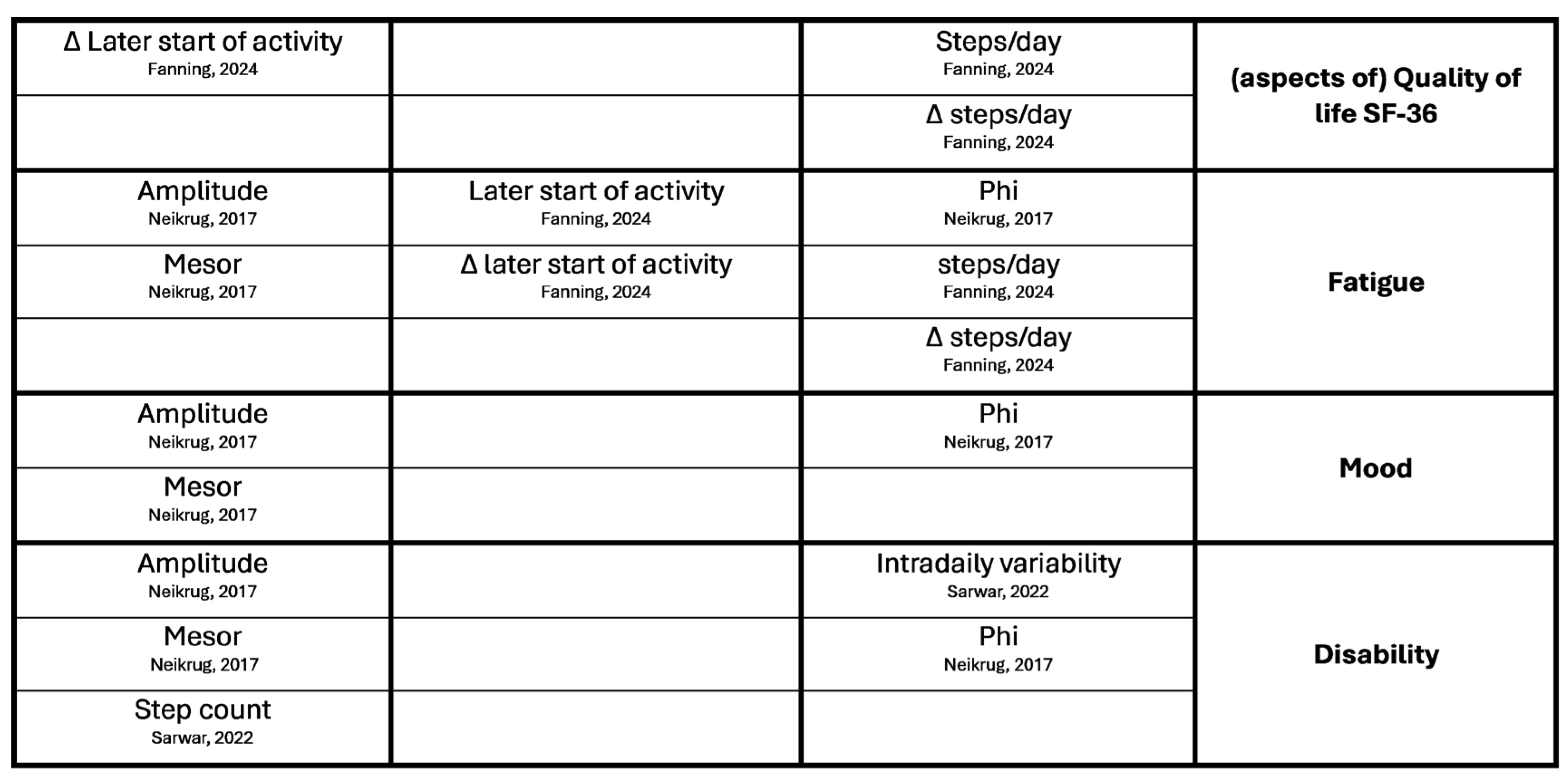

Appendix B. Overview of Results of Hypotheses Testing with Associations

References

- Treede, R.D. et al., “Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11),” Jan. 01, 2019, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [CrossRef]

- Breivik, H.; Collett, B.; Ventafridda, V.; Cohen, R.; Gallacher, D., “Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment,” European Journal of Pain, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 287, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Van Rysewyk, S. et al., “Understanding the Lived Experience of Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence Syntheses,” Br J Pain, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 592–605, 2023. [CrossRef]

- De-Diego-Cordero, R.; Velasco-Domínguez, C.; Aranda-Jerez, A.; Vega-Escaño, J., “The Spiritual Aspect of Pain: An Integrative Review,” J Relig Health, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 159–184, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Meints, S.M.; Edwards, R.R., “Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes,” Dec. 20, 2018, Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M., “Chronic Pain 1 Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances,” 2021. [Online]. Available: www.thelancet.com.

- Hassett, A.L.; Williams, D.A., “Non-pharmacological treatment of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain,” 2011, Bailliere Tindall Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Cane, D.; Nielson, W.R.; Mazmanian, D., “Patterns of pain-related activity: Replicability, treatment-related changes, and relationship to functioning,” Pain, vol. 159, no. 12, pp. 2522–2529, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Racine, M. et al., “Pain-related Activity Management Patterns and Function in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome,” Clinical Journal of Pain, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 122–129, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Esteve, R.; Ramírez-Maestre, C.; Peters, M.L.; Serrano-Ibáñez, E.R.; Ruíz-Párraga, G.T.; López-Martínez, A.E., “Development and initial validation of the activity patterns scale in patients with chronic pain,” Journal of Pain, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 451–461, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Kindermans, H.P.J.; Roelofs, J.; Goossens, M.E.J.B.; Huijnen, I.P.J.; Verbunt, J.A.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S., “Activity patterns in chronic pain: Underlying dimensions and associations with disability and depressed mood,” Journal of Pain, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 1049–1058, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, S.; Kindermans, H., “A self-regulation perspective on avoidance and persistence behavior in chronic pain: New theories, new challenges?,” Feb. 21, 2015, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [CrossRef]

- Hasenbring, M.I.; Psych, D.; Verbunt, J.A., “Fear-avoidance and Endurance-related Responses to Pain: New Models of Behavior and Their Consequences for Clinical Practice,” Clin J Pain, vol. 26, no. 9, 2010, [Online]. Available: www.clinicalpain.com|747.

- Ridgers, N.D.; Denniss, E.; Burnett, A.J.; Salmon, J.; Verswijveren, S.J.J.M., “Defining and reporting activity patterns: a modified Delphi study,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, vol. 20, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cane, D.; Nielson, W.R.; Mccarthy, M.; Mazmanian, D., “Pain-related Activity Patterns Measurement, Interrelationships, and Associations With Psychosocial Functioning,” 2013. [Online]. Available: www.clinicalpain.com|435.

- McCracken, L.M.; Samuel, V.M., “The role of avoidance, pacing, and other activity patterns in chronic pain,” Pain, vol. 130, no. 1–2, pp. 119–125, Jul. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.E.; Strong, J.; Meredith, P.J., “Activity pacing, avoidance, endurance, and associations with patient functioning in chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” 2012, W.B. Saunders. [CrossRef]

- Wertli, M.M.; Rasmussen-Barr, E.; Held, U.; Weiser, S.; Bachmann, L.M.; Brunner, F., “Fear-avoidance beliefs - A moderator of treatment efficacy in patients with low back pain: A systematic review,” Spine Journal, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 2658–2678, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Fehrmann, E.; Fischer-Grote, L.; Kienbacher, T.; Tuechler, K.; Mair, P.; Ebenbichler, G., “Perceived psychosocial stressors and coping resources in chronic low back pain patients as classified by the avoidance-endurance model,” Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, vol. 3, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, J. et al., “Endurance and avoidance response patterns in pain patients: Application of action control theory in pain research,” PLoS One, vol. 16, no. 3 March, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Racine, M. et al., “Pain-Related Activity Management Patterns as Predictors of Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome,” Pain Medicine (United States), vol. 21, no. 2, pp. E191–E200, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Teichmüller, K.; Kübler, A.; Rittner, H.L.; Kindl, G.K., “Avoidance and Endurance Responses to Pain Before and with Advanced Chronification: Preliminary Results from a Questionnaire Survey in Adult Patients with Non-Cancer Pain Conditions,” J Pain Res, vol. 17, pp. 2473–2481, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv-Ionescu, A. et al., “Concern about Falling and Complexity of Free-Living Physical Activity Patterns in Well-Functioning Older Adults,” Gerontology, vol. 64, no. 6, pp. 603–611, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, K.; et al., “Decreased Fractal Correlation in Diurnal Physical Activity in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome,” Methods Inf Med, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 26–29, 2004.

- Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Buchser, E.; Rutschmann, B.; Aminian, K., “Nonlinear analysis of human physical activity patterns in health and disease,” Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys, vol. 77, no. 2, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Prince, S.A.; Adamo, K.B.; Hamel, M.E.; Hardt, J.; Gorber, S.C.; Tremblay, M., “A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: A systematic review,” Nov. 06, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.L. et al., “Feasibility, Validity, and Responsiveness of Self-Report and Objective Measures of Physical Activity in Patients With Chronic Pain,” PM and R, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 858–867, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Van Weering, M.G.H.; Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.M.R.; Hermens, H.J., “The relationship between objectively and subjectively measured activity levels in people with chronic low back pain,” Clin Rehabil, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 256–263, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Verbunt, J.A.; Huijnen, I.P.J.; Köke, A., “Assessment of physical activity in daily life in patients with musculoskeletal pain,” Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Fitzsimons, C.; Baker, G., “Should we reframe how we think about physical activity and sedentary behaviour measurement? Validity and reliability reconsidered,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, vol. 13, no. 1, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.A. et al., “Reliability and validity of two multidimensional self-reported physical activity questionnaires in people with chronic low back pain,” Musculoskelet Sci Pract, vol. 27, pp. 65–70, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.L. et al., “Feasibility, Validity, and Responsiveness of Self-Report and Objective Measures of Physical Activity in Patients With Chronic Pain,” PM and R, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 858–867, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- McGovney, K.D.; Curtis, A.F.; McCrae, C.S., “Actigraphic Physical Activity, Pain Intensity, and Polysomnographic Sleep in Fibromyalgia,” Behavioral Sleep Medicine, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 383–396, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Morelhão, P.K. et al., “Physical activity and disability measures in chronic non-specific low back pain: a study of responsiveness,” Clin Rehabil, vol. 32, no. 12, pp. 1684–1695, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.G.; Wellburn, S.; McDonough, S.; Martin, D.J.; Batterham, A.M., “The association between displacement of sedentary time and chronic musculoskeletal pain: an isotemporal substitution analysis,” Physiotherapy (United Kingdom), vol. 103, no. 4, pp. 471–477, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Backes, A.; Gupta, T.; Schmitz, S.; Fagherazzi, G.; van Hees, V.; Malisoux, L., “Advanced analytical methods to assess physical activity behavior using accelerometer time series: A scoping review,” Jan. 01, 2022, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.T.; Wang, C.; Hsiao, C.K., “Data Analytics in Physical Activity Studies With Accelerometers: Scoping Review,” 2024, JMIR Publications Inc. [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Bertrand, A.M.; Robert, T.; Chèze, L., “Measuring objective physical activity in people with chronic low back pain using accelerometers: a scoping review,” 2023, Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E., “Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach,” BMC Med Res Methodol, vol. 18, no. 1, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H., “ICD-11 for morbidity and mortality statistics, MG30.02 Chronic primary musculoskeletal pain. https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#1236923870.”.

- Treede, R.D. et al., “A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11,” Pain, vol. 156, no. 6, pp. 1003–1007, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C. et al., “PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation,” Oct. 02, 2018, American College of Physicians. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J., “Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version),” JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Verbunt, J.A.; Huijnen, I.P.J.; Seelen, H.A.M., “Assessment of Physical Activity by Movement Registration Systems in Chronic Pain Methodological Considerations SPECIAL TOPIC SERIES 496 |.” [Online]. Available: www.clinicalpain.com.

- Danilevicz, I.M.; Vidil, S.; Landré, B.; Dugravot, A.; van Hees, V.T.; Sabia, S., “Reliable measures of rest-activity rhythm fragmentation: how many days are needed?,” European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, vol. 21, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.L.; Swartz, A.M.; Cashin, S.E.; Strath, S.J., “How many days of monitoring predict physical activity and sedentary behaviour in older adults?,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, vol. 8, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.M. et al., “Number of days required to measure sedentary time and physical activity using accelerometery in rheumatoid arthritis: a reliability study,” Rheumatol Int, vol. 43, no. 8, pp. 1459–1465, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Huijnen, I.P.J.; Schasfoort, F.C.; Smeets, R.J.E.M.; Sneekes, E.; Verbunt, J.A.; Bussmann, J.B.J., “Subgrouping patients with chronic low back pain: What are the differences in actual daily life behavior between patients classified as avoider or persister?,” J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 303–311, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Huijnen, I.P.J. et al., “Differences in activity-related behaviour among patients with chronic low back pain,” European Journal of Pain, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 748–755, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Huijnen, I.P.J. et al., “Effects of self-discrepancies on activity-related behaviour: Explaining disability and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain,” Pain, vol. 152, no. 9, pp. 2165–2172, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Reneman, M.F.; Preuper, R.H.S.; Otten, E.; Lamoth, C.J., “Relationship between physical activity and central sensitization in chronic low back pain: Insights from machine learning,” Comput Methods Programs Biomed, vol. 232, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.E.; Strong, J.; Meredith, P.J., “Overactivity in chronic pain: Is it a valid construct?,” Pain, vol. 156, no. 10, pp. 1991–2000, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.E.; Ireland, D.; Deen, M.; Varnfield, M., “Clinical utility of a mHealth assisted intervention for activity modulation in chronic pain: The pilot implementation of pain ROADMAP,” European Journal of Pain (United Kingdom), vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 749–765, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- van de Schoot, R. et al., “An open source machine learning framework for efficient and transparent systematic reviews,” Nat Mach Intell, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 125–133, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Boetje, J.; van de Schoot, R., “The SAFE procedure: a practical stopping heuristic for active learning-based screening in systematic reviews and meta-analyses,” Syst Rev, vol. 13, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Herbelet, S.; Tuinman, P.R.; Terwee, C.B., “Content validity: judging the relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility of an outcome measurement instrument – a COSMIN perspective,” J Clin Epidemiol, vol. 185, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B. et al., “COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study,” May 01, 2018, Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B. et al., “The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes,” J Clin Epidemiol, vol. 63, no. 7, pp. 737–745, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Korszun, A.; Young, E.A.; Engleberg, N.C.; Brucksch, C.B.; Greden, J.F.; Crofford, L.A., “Use of actigraphy for monitoring sleep and activity levels in patients with fibromyalgia and depression,” J Psychosom Res, vol. 52, pp. 439–443, 2002.

- Solis, R.F.M., “Physical activity and its association with pain-related distress and pain processing before and after exercise-induced low back pain. Dissertation.,” 2016.

- Neikrug, A.B.; Donaldson, G.; Iacob, E.; Williams, S.L.; Hamilton, C.A.; Okifuji, A., “Activity rhythms and clinical correlates in fibromyalgia,” Pain, vol. 158, no. 8, pp. 1417–1429, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Liszka-Hackzell, J.J.; Martin, D.P., “An analysis of the relationship between activity and pain in chronic and acute low back pain,” Anesth Analg, vol. 99, no. 2, pp. 477–481, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Perruchoud, C.; Buchser, E.; Aminian, K., “Barcoding human physical activity to assess chronic pain conditions,” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 2, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Perruchoud, C.; Rutschmann, B.; Buchser, E.; Aminian, K., “Quantifying dimensions of physical behavior in chronic pain conditions,” J Neuroeng Rehabil, vol. 13, no. 1, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Fanning, J.; Brooks, A.K.; Irby, M.B.; N’dah, K.W.; Rejeski, W.J., “Associations Between Patterns of Daily Stepping Behavior, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Pain Symptoms Among Older Adults with Chronic Pain: A Secondary Analysis of Two Randomized Controlled Trials,” Clin Interv Aging, vol. 19, pp. 459–470, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fanning, J. et al., “Associations between patterns of physical activity, pain intensity, and interference among older adults with chronic pain: a secondary analysis of two randomized controlled trials,” Frontiers in Aging, vol. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Agu, E.O.; Polcari, J.; Ciroli, J.; Nephew, B.; King, J., “PainRhythms: Machine learning prediction of chronic pain from circadian dysregulation using actigraph data — a preliminary study,” Smart Health, vol. 26, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.E.; Strong, J.; Meredith, P.J.; D’arrigo, R.G., “Association Between Physical Activity and Sleep in Adults With Chronic Pain: A Momentary, Within-Person Perspective,” 2014. [Online]. Available: https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/94/4/499/2735639.

- Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Buchser, E.E.; Rutschmann, B.; Najafi, B.; Aminian, K., “Ambulatory system for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of gait and posture in chronic pain patients treated with spinal cord stimulation,” Gait Posture, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 113–125, Oct. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Brond, J.C., “ActigraphCounts. https://github.com/jbrond/actigraphcounts.”.

- Wilson, I.B.; Cleary, P.D., “Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes.,” JAMA, vol. 273, no. 1, pp. 59–65, Jan. 1995.

- Kindermans, H.P.J.; Roelofs, J.; Goossens, M.E.J.B.; Huijnen, I.P.J.; Verbunt, J.A.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S., “Activity patterns in chronic pain: Underlying dimensions and associations with disability and depressed mood,” Journal of Pain, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 1049–1058, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Bianchim, M.S.; McNarry, M.A.; Larun, L.; Mackintosh, K.A., “Calibration and validation of accelerometry to measure physical activity in adult clinical groups: A systematic review,” Dec. 01, 2019, Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Mielke, G.I.; de Almeida, M.; Ekelund, U.; Rowlands, A.V.; Reichert, F.F.; Crochemore-Silva, I., “Absolute intensity thresholds for tri-axial wrist and waist accelerometer-measured movement behaviors in adults,” Scand J Med Sci Sports, vol. 33, no. 9, pp. 1752–1764, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Brady, R.; Brown, W.J.; Hillsdon, M.; Mielke, G.I., “Patterns of Accelerometer-Measured Physical Activity and Health Outcomes in Adults: A Systematic Review,” Jul. 01, 2022, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [CrossRef]

- Staudenmayer, J.; He, S.; Hickey, A.; Sasaki, J.; Freedson, P., “Methods to estimate aspects of physical activity and sedentary behavior from high-frequency wrist accelerometer measurements,” J Appl Physiol, vol. 119, pp. 396–403, 2015. [CrossRef]

- COSMIN, “How to select and report a Patient-Reported Outcome (Measure) – PRO(M)?2024-Kopie.pdf,” Web Page.

- Gagnier, J.J. et al., “COSMIN reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures: version 2.0,” Quality of Life Research, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chan, S. et al., “CAPTURE-24: A large dataset of wrist-worn activity tracker data collected in the wild for human activity recognition,” Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Huijnen, I.P.J. et al., “Do depression and pain intensity interfere with physical activity in daily life in patients with Chronic Low Back Pain?,” Pain, vol. 150, no. 1, pp. 161–166, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Migueles, J.H. et al., “Accelerometer Data Collection and Processing Criteria to Assess Physical Activity and Other Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Practical Considerations,” Sep. 01, 2017, Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, A.; Desai, F.; Stewart, T.; Duncan, S.; MacKay, L., “Application of raw accelerometer data and machine-learning techniques to characterize human movement behavior: A systematic scoping review,” 2020, Human Kinetics Publishers Inc. [CrossRef]

- Crouter, S.E.; Flynn, J.I.; Bassett, D.R., “Estimating physical activity in youth using a wrist accelerometer,” Med Sci Sports Exerc, vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 944–951, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- Farrahi, V.; Niemela, M.; Tjurin, P.; Kangas, M.; Korpelainen, R.; Jamsa, T., “Evaluating and Enhancing the Generalization Performance of Machine Learning Models for Physical Activity Intensity Prediction from Raw Acceleration Data,” IEEE J Biomed Health Inform, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 27–38, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Farrahi, V.; Niemelä, M.; Kangas, M.; Korpelainen, R.; Jämsä, T., “Calibration and validation of accelerometer-based activity monitors: A systematic review of machine-learning approaches,” Feb. 01, 2019, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Pulsford, R.M. et al., “The impact of selected methodological factors on data collection outcomes in observational studies of device-measured physical behaviour in adults: A systematic review,” Dec. 01, 2023, BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Ozemek, C.; Kirschner, M.M.; Wilkerson, B.S.; Byun, W.; Kaminsky, L.A., “Intermonitor reliability of the GT3X+ accelerometer at hip, wrist and ankle sites during activities of daily living,” Physiol Meas, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 129–138, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

| Author (year) | Study design |

Aim of the study related to AP |

Sample size | Sample description |

Sex (female/male) |

Age (sd), range |

| Andrews (2014)[68] | Cross-sectional | (part of the research) Associations of overactivity with sleep |

50 | CP from MPC, outpatient, persistent non-cancer at least 3 months, generalized pain affecting gross movement, English literate, >18yrs, exclusion = sleep disorder. | 30/20 | 53.22 (10.68), 33-73 |

| Andrews (2015)[52] | Cross-sectional | Associations of objective overactivity with self-report overactivity and avoidance |

68 | CP from MPC, non-cancer, generalized distribution with impact on gross movement. | 44/24 | 52.85, (11.40), 25-73 |

| Andrews (2023)[53] | Longitudinal cohort baseline, week 7 and week 13 | Differences in pacing and avoidance pre- and post- treatment | 20 | CP from tertiary MPC, selection on overactivity behavior with difficulty implementing pacing strategies and activity-related exacerbations. | 9/11 | 46.9, (NR), 20-67 |

| Fanning (2023)[66] | Longitudinal cohort, Baseline and week 12 |

Associations of time spent in and bout lengths of different stepping intensities with pain intensity and interference. Change after 12 weeks behavioral program on PA or 12-week control group. |

41 | CP at least at two sites of neck, shoulder, back, hip or knee, included by physician for online telecoaching and mHealth intervention, BMI 30-45 kg/m2, self-reported to be low active, weight stable and no contraindications for exercise. |

30/11 | 69.61 (6.48) |

| Fanning (2024)[65] | Longitudinal cohort, Baseline and week 12 |

Associations of stepping patterns with pain and QoL. Change after 12 weeks behavioral program on weight loss and PA. |

68 | CP at least at two sites of neck, shoulder, back, hip or knee, included by physician for online telecoaching and mHealth intervention, BMI 30-45 kg/m2, self-reported to be low active, weight stable and no contraindications for exercise. |

52/16 | 69.53 (6.74) |

| Huijnen (2011_1)[49] | Cross-sectional | Differences between avoiders, persisters, mixed performers and healthy performers as classified by POAM-P questionnaire Associations of pain intensity with objective activity in avoiders and persisters |

116 | CLBP from MPC, HDR and via advertisement, 18-65, no specific pathology, no psychiatric disease, no pregnancy | 36/43 | Avoiders 45.7 (9.8) , persisters 48.2 (8.4), mixed 44.2 (10.9), functional 50.6 (12.5) |

| Huijnen (2011_2)[50] | Longitudinal cohort, baseline, 6 months | Associations between self-discrepancy type and objective avoidance and persistence. Change over time. |

116 | CLBP from MPC, HDR and via advertisement, 18-65, no specific pathology, no psychiatric disease, no pregnancy | T1 39/45, T2 23/26 | 47.5 (10.5), 47.8 (10.9) |

| Huijnen (2020)[48] | Cross-sectional | Differences in objective avoidance and persistence between patients classified by their treating consultant as avoider or persister | 16 | CLBP from MPC and HDR (>6 months, 18-65), no specific pathology, no pregnancy, no pacemaker, no serious psychiatric disorder | 8/8 | Avoiders 50 37.5-55.0, persisters 46 45.0-59.0 |

| Liszka-Hackzell (2004)[62] | Longitudinal cohort 3 weeks continuously |

Differences between subgroups of chronic and acute pain | 15 CLBP, 15 acute pain | CLBP from MPC, pain >6 months. 18-75yrs, (acute <2wks) | CLBP 7/8 Acute 6/9 |

CLBP 51 (10.2) Acute 46 (10.6) |

| Neikrug (2017)[61] | Cross-sectional | Associations of activity rhythm parameters with FMS symptoms | 292 | Fibromyalgia from MPC, community physicians and advertisement | 272/20 | 45.1 (11.1), 21-65 |

| Paraschiv (2008)[25] | Cross-sectional | Differences of dynamics of human activity between CP and no pain. | 15 CP, 15 no pain | patients from MPC who are candidate for SCS | 7/8 | 66 (14) |

| Paraschiv (2012)[63] | Cross-sectional | Associations of dynamics of physical activity with categorized pain intensity (mild, moderate, severe) and age | 60 CP, 15 no pain | Patients from MPC who are candidate for SCS | 18/42 | No pain: 57 (14), severe pain middle age: 54 (9), moderate pain old age: 71 (14), severe pain old age: 74 (8) |

| Paraschiv (2016)[64] | Cross-sectional | Differences of parameters quantifying the multidimensionality of physical behavior between subgroups mild pain and moderate to severe pain | 74 CP, 18 no pain | 74 CP patients with chronic intractable pain and candidate for SCS | 48/44 | 63 (14) |

| Sarwar (2022)[67] | Cross-sectional | Develop machine learning algorithm to predict pain, pain intensity, pain interference and disability from cumulative and relative activity measures, sleep measures and rest activity rhythm measures. Associations between rhythm measures and pain intensity, interference and disability |

25 CP, 27 no pain | 25 CP mixed | 10/12, (3 sex not specified) | NR |

| Zheng (2023)[51] | Cross-sectional | Differences of physical activity intensity patterns between subgroups in CLBP with high and low central sensitization. Differences with conventional cut-point approach. |

42 | Primary CLBP from MPC | 27/15 | 39.6 (12.6) |

| Author (year) | Concept related to activity patterns | Definition of concept (conceptualization) | Definition of variables (operationalization) | Indicators for variables |

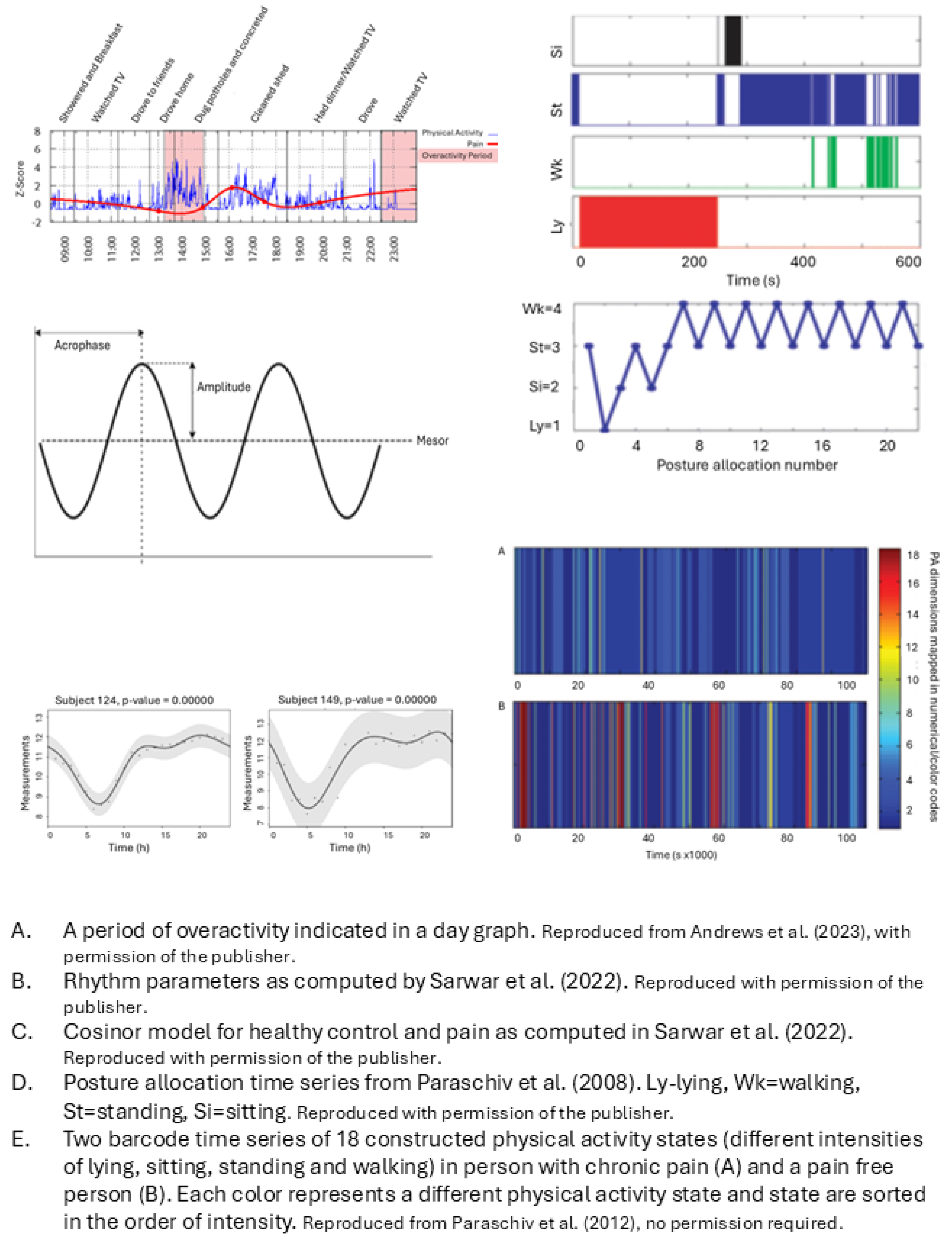

| Andrews (2014) | (part of the research) Overactivity |

Overactivity: high levels of activity → severe pain aggravation + inactivity → sawtooth activity pattern with pain and activity fluctuating greatly over time |

Sawtooth pattern = higher fluctuation value of timeseries of vector magnitude of activity counts per minute | Fluctuation value = Root mean square of difference of 2 successive cumulative 15 min vector magnitude |

| Andrews (2015) | Overactivity |

Overactivity: being active in a way that significantly exacerbates pain → periods of incapacity |

Level of overactivity = number of overactive periods An overactive period is counted when pain aggravation occurs following a prolonged time of being sedentary or highly active |

Overactive period = pain aggravation (pain intensity z-score >1.65) AND sedentary task > 1hr OR High activity period (objective physical activity z-score > 1.65) for periods under an hour or >1.28 for periods over an hour. Within 2 hrs of pain aggravation |

| Andrews (2023) | Pacing Overactivity |

Overactivity: too long on an activity (being active or sedentary with sustained spinal position) → pain aggravation Pacing: decreased frequency of overactivity periods |

As Andrews (2015) | As Andrews (2015) |

| Fanning (2023) |

The pattern of PA accumulation (i.e. bout length) and rest accumulation | The pattern is described as 1. the time spent in light and moderate physical activity and in rest and 2. the breaks within light and moderate physical activity and rest Hypothesis: Greater sedentary time, fewer sedentary breaks, and sustained participation in more intensive activity will result in worse pain outcome |

Activity intensity equals Steps/minute Time spent in rest = Minutes/day being low-active in a seated or lying posture Time being active = Average daily steps and time stepping at different intensities Number of sedentary breaks = Postural shifts from sit to stand Breaks within activity intensities = count of bouts of a certain length (<1 min, 1-5 min, 5-10 min, 10-20 min and >20 min) for each activity intensity |

Activity intensity: Moderate: 100-125 steps/min Light: 75-100 steps/min Very light: <75 steps/min Rest: minutes classified by software as low-active in seated or lying position |

| Fanning (2024) | The pattern of PA intensity throughout the day |

PA intensity equals stepping frequency (steps/minute) The PA pattern per participant can be expressed by Fourier functions It is hypothesized that patterns will differentiate in timing of activity and rest and in amplitude |

To summarize the PA pattern per participant, a 9-basis Fourier function is derived from each timeseries of steps/minute | Two different types of Fourier functions were distinguished with functional Principal Component Analysis: 1. Amount of stepping 2. Early vs. late risers |

| Huijnen (2011_1) | Avoidance Persistence |

Avoidance: try to escape from activities that are expected to increase pain or injury → low activity levels Persistence: continue activities despite pain until completion → increasing pain → forced rest → sawtooth pattern + longer daily uptime because of postponed rest |

1. Persistence = higher physical activity level, more fluctuations, longer daily uptime than avoiders 2. Persistence = increased pain after increased activity |

1a. Daily uptime = wear time. 1b. Mean total activity score = mean counts per day from raw data 1c. Highest activity score = 80% power of highest activity score of monitoring period 1d. Fluctuation score = sum of activity counts during 15 minutes, then root mean square of difference of 2 subsequent 15 minute-periods 2. Increased pain after activity = association between pain and activity level over time with two level hierarchical linear regression analysis |

| Huijnen (2011_2) | Avoidance Persistence |

Not mentioned, but as Huijnen 2011_1 (oral comment) | Persistence = higher scores on daily uptime and activity related style than avoidance |

Daily uptime as in Huijnen 2011_1. Activity related style is linear combination of daily uptime, mean total activity score, fluctuation score as in Huijnen 2011_1 |

| Huijnen (2020) | Avoidance Persistence |

Avoidance: catastrophizing thoughts about pain + fear of movement → lower daily activity levels Persistence: doing too much, not respecting one’s physical limits and experiencing a rebound effect of over-activity → activity levels similar to people without pain |

Avoiders will differ from persisters in 1. Overall daily activity level 2. Duration of being active vs sedentary , 3. Mean general motility (as a measure of intensity; m/s2), and walking motility 4. Number of transitions, and/or 5. Distribution of active vs sedentary behavior |

Distribution measures: 1. Number of active and sedentary bouts, i.e. periods classified as standing, walking, running, cycling or non-cyclic movements vs sitting or lying 2. Median bout length of active and sedentary behavior 3. Covariance of variation of bout length 4. Fragmentation: number of bouts of physical activity or sedentary divided by total duration of activity or sedentary. 5. W-index for activity or sedentary behavior = (total time of bout lengths above median bout length)/total duration. |

| Liszka-Hackzell (2004) | Activity-related pain | Increased activity → increased pain (with acute pain, not with CP) | Cross-correlation between pain level and activity counts per minute with time lag up to 60 minutes | Cross-correlation at different time lags of interpolated pain levels and activity level time series resampled to one sample every 10 min, with time-lags up to 60 min |

| Neikrug (2017) | Activity rhythms in fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) | Activity rhythms factor in activity level, timing and duration over multiple days | Activity rhythm parameters: 1. Mesor, 2. Amplitude, 3. Phi, averaged over measurement period And the daily variation (standard error) of these 3 parameters compared to weekly average |

1. Mesor = mean activity level in units of the actigraph 2. Amplitude = distance between mesor and peak of curve, according to fitted 24-hr cosine model 3. Phi = time of day of the average peak activity over the week |

| Paraschiv (2008) | Dynamics of human activity |

Dynamics of human activity captured by timeseries of: Sequence of postures Timing Time spent in a posture Any combination |

The temporal pattern of each timeseries is quantified with fractal analysis and symbolic dynamic statistics 4 time series: 1. Sequence of posture allocation. 2. Duration of walking periods. 3. Timing of activity-rest transitions as point process. 4. Context dependent symbolic description of the sequence of successive activity-rest periods. |

1. Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA) on categorical time series of posture allocation of 4 classified postures (lying, sitting, standing, walking) 2. Cumulative Distribution Function and DFA on sequence of walking episodes characterized by their duration 3. Fano Factor Analysis on time series of the moment in time of transitions from rest (sitting and lying) to activity (standing and walking) and v.v. 4. Symbolic dynamics statistics on symbol series created by coding the comparison of the duration of each activity period with the rest periods just before and after. Values are 0 or 1, 0 = rest period equals activity period. Constructing word sequences from the symbol series |

| Paraschiv (2012) | Dynamics of sequences of various physical activity states | Dynamics of states are related to structural complexity. Structural complexity depends on the variety of physical activity states and their occurrence in time |

Structural complexity: metrics from timeseries of physical activity states: 2 states of lying/sitting dependent on acceleration, 4 states of standing dependent on acceleration, 11 states of walking dependent on cadence and duration |

Metrics are determined from timeseries of 18 possible physical activity states, variety of states, temporal structure of state-sequence 1. Complexity metrics: information entropy, Lempel-Ziv complexity and sample entropy 2. Quantitative global metrics: time% spent walking and/or standing 3. Composite deterministic score: sum of the three normalized complexity scores * time% being active 4. Composite statistical score with linear discrimination analysis |

| Paraschiv (2016) | Multidimensionality of physical behavior | Individual physical behavior: Multidimensional attributes (like type, intensity and duration of activities, movements and postures) Dynamic attributes (the change over time) Relational attributes (factors that modulate behavioral patterns) |

Multidimensionality = composite score from metrics quantifying Type Duration Intensity Temporal pattern |

Composite score from factor analysis with metrics: 1. % of time walking, % of time on feet 2. 0.975th upper quartile of bout lengths of being active 3. Excess rest vs deficit rest by plotting cumulative distribution of excess and deficit rest and calculate Kolmogorov-Smirnov distance 4. three types of entropy on timeseries of 18 different states described in Paraschiv 2012 |

| Sarwar (2022) | Rest-activity circadian rhythm |

Rest-activity rhythm is quantified by Parameters derived from a fitted cosine curve Intradaily (hour to hour) variability (IV) as a measure of circadian disturbance. IV = the change of activity level from hour to hour. Higher IV indicates more daytime napping or nighttime arousal |

Rhythm is quantified with 1. Eight rhythmic features from a cosine curve fitted to 24h timeseries of activity counts and 2. Intradaily variability of hour-to-hour activity counts |

Eight rhythmic features from a cosine curve that is fitted to a 24h timeseries of activity counts: 1. Mesor 2. Acrophase 3. Amplitude, 4. Relative amplitude = amplitude/mesor 5. Multi-scale entropy (pearson's sample entropy), 6. Mean activity during the most active 10h (M10, as an estimate of daily activity), 7. Mean activity during the least active 5h (L5, as an estimate of nocturnal activity), 8. rest-activity relative amplitude ((M10-L5)/(M10+L5)), Intradaily variability: Where: N is the total number of datapoints, xi are the individual data points and μ is their mean |

| Zheng .(2023) | PA intensity patterns |

PA intensity patterns: Temporal organization of PA intensity levels Transition between PA intensity levels |

Pattern: Bout duration of 5 hidden states reflecting 5 intensity levels Accumulated time per hidden state per day Transition probability from one hidden state to every other hidden state Hidden states: Derived from accelerometer time series with a machine learning algorithm Reflect 5 intensity classes |

Pattern = One value of bout duration per intensity class One value of accumulated time per intensity Values for transition probability from each intensity to each other intensity |

| Author (year) | Device |

Wear location |

Measurement frequency | Duration |

Other principal variables for AP-related concept of study |

Other variables for associations, differences between groups or treatment results |

Valid data definition | Epoch length | Conversion method |

| Andrews (2014) | GT3X Actigraph | NR | 30 Hz | 5 days + nights, at least 1 weekend day | Pain intensity 11-point VAS, (mood, stress, catastrophizing) 6x/day | Parameters of sleep derived from accelerometry | NR | 1 minute | Activity counts per minute and then vector count per minute |

| Andrews (2015) | GT3X Actigraph | NR | 30 Hz | 5 days, at least 1 weekend day | Pain intensity 11-point VAS, 6 times/day at random intervals. Diary | Self-reported approach to activity (PARQ) | 4 complete days for each parameter | 1 minute | Activity counts per minute and then vector count per minute |

| Andrews (2023) | GT3X Actigraph | Waist | NR | 5 days | Pain intensity (not specified), 1/hr, interpolated to 1/min | Average pain, average activity level, medication intake, self-reported overactivity, avoidance, depression, anxiety, stress and time in leisure, social, rest or productive tasks. | (1) At least 75% of waking hours could be accounted for by diary activities entered in the Pain ROADMAP app and (2) Actigraph data were available for this same time period. At least five of the 7days of monitoring needed to be classified as a valid data collection day for the whole monitoring period to be considered valid |

1 minute | GT3X automatically converses changes in tri-axial acceleration to activity counts per minute. Vector magnitude from activity counts per minute in 3 axes was calculated |

| Fanning (2023) |

ActivPAL 4 |

Upper midline of thigh | NR | 7 days | None | PROMIS Pain intensity scale, PROMIS Pain interference scale | 3 days | NR |

Data processing with PALBatch 8.11.63. Classification to stepping, lying and sitting with CREA algorithm 1.3 Ambulatory activity intensity is derived from stepping cadence bands |

| Fanning (2024) |

ActivPAL 4 | Upper midline of thigh | NR | 7 days | None | PROMIS Pain intensity scale, PROMIS Pain interference scale, Health-related quality of life with SF-36 (physical function, emotional role limitations, physical role limitations, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, social function, pain and general health) | 3 days | 1 minute | Data processing with PALBatch 8.11.63. Data classification with CREA algorithm 1.3. Both not specified |

| Huijnen (2011_1) | RT3 | NR | NR | 14 days | Pain intensity 8x/day 7-point Likert-scale | Classification of participants as avoider, persister, mixed performer or functional performer with POAM-P | At least 5 days including 1 weekend day. 1 valid day has at least 10hrs. | 1 minute | 1. Resultant vector from 3D signal. 2. counts per minute of exceedance of predefined threshold. For association with pain: mean activity signal between two pain measurements |

| Huijnen (2011_2) | RT3 | NR | NR | 14 days | None | Self-discrepancy type with HSQ, age, gender, pain duration, mean pain intensity | At least 5 days including 1 weekend day. | 1 minute | As in Huijnen 2011 (1) |

| Huijnen (2020) | VitaMove activity monitor | Chest + left and right thigh | 128 Hz | 5 days | None | Classification of participants as avoider or persister by treating consultant | Number of days flexible. | 1 sec for analyses of postures, motions and transitions | Detection of postures and motions 1/sec with VitaScore Software |

| Liszka-Hackzell (2004) | AW-64 actiwatch | Non-dominant arm | NR | 3 weeks | Pain 11-point VAS at least every 90 minutes | Having chronic or acute LBP | At least 14 complete days of activity and pain | 1 minute | Activity was sampled as accumulated counts/minute |

| Neikrug (2017) | MicroMini-Motionlogger Actigraph | Non-dominant wrist | 32 Hz | 7 days | None | Pain severity and interference (MPI), physical impairment and functioning (FIQ), fatigue (MFI), mood (CESD), sleep (from actigraph) | Equal or less than 1 night missing or less than 8hrs missing data during the day | 1 minute | With actigraph Action-3 software, outcome parameter not specified |

| Paraschiv (2008) | 1 biaxial and 1 uniaxial accelerometer ADXL202 + gyroscope | Biaxial chest, uni-axial thigh, gyroscope thigh + shank | 40 Hz | 5 weekdays, 8hrs/day | None | None | NR | 1 sec | Discrete wavelet transformation, Savitzky-Golay smoothing filters and numerical gradient on raw data. Then: 1. type of activity with previously developed algorithm [69] 2. intensity of walking from mean walking cadence during each walking period. 3. intensity of sitting lying standing with trunk acceleration norm |

| Paraschiv (2012) | 3x biaxial ADXL202 + gyroscope | Sternum, mediolateral thigh, shank | 40 Hz | 5 weekdays, 8hrs/day | None | Pain-score classified as no, moderate and severe pain. Age classified as middle age and old age | NR | 1 sec | As Paraschiv et al. (2008) |

| Paraschiv (2016) | 2x triaxial MMA7341LT + gyroscope |

Sternum and mediolateral axis of thigh | 40 Hz | 5 weekdays, 8hrs/day | None | Pain-score VAS classified as mild pain (VAS≤4) and moderate to severe pain (VAS>4), | NR | 1 sec | As Paraschiv et al. (2008) |

| Sarwar (2022) | Actigraph GT3X | Wrist | NR | 5 days +nights on weekdays | None | Average pain intensity, pain interference and disability with PROMIS-29 v2.0 | Days with at least 20% of complete data were included | 1 hour | Activity and sleep variables with algorithms from ActiLife software, resampled to 1 hr and smoothed with 3h simple moving average |

| Zheng (2023) | GT3X | Front right hip (Anterior superior iliac spine) | 100 Hz | Approx. 1 week, excl sleeping and bathing | None | Central sensitization symptoms with CSI | Days with complete 24hr covered. 4 days, randomly selected | 5 sec | Gravity effects removed from raw data, vector magnitude calculated, averaged over 5s. For comparison with conventional cut points approach: Resampled to 30 Hz, then bandpass Butterworth filter with 4 orders, then filter with coefficient matrices from Brønd [70] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).