Submitted:

08 November 2023

Posted:

09 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and registration

2.2. Eligibility criteria

2.3. Information sources & Search strategy

2.4. Study selection

2.5. Data collection process & Data items

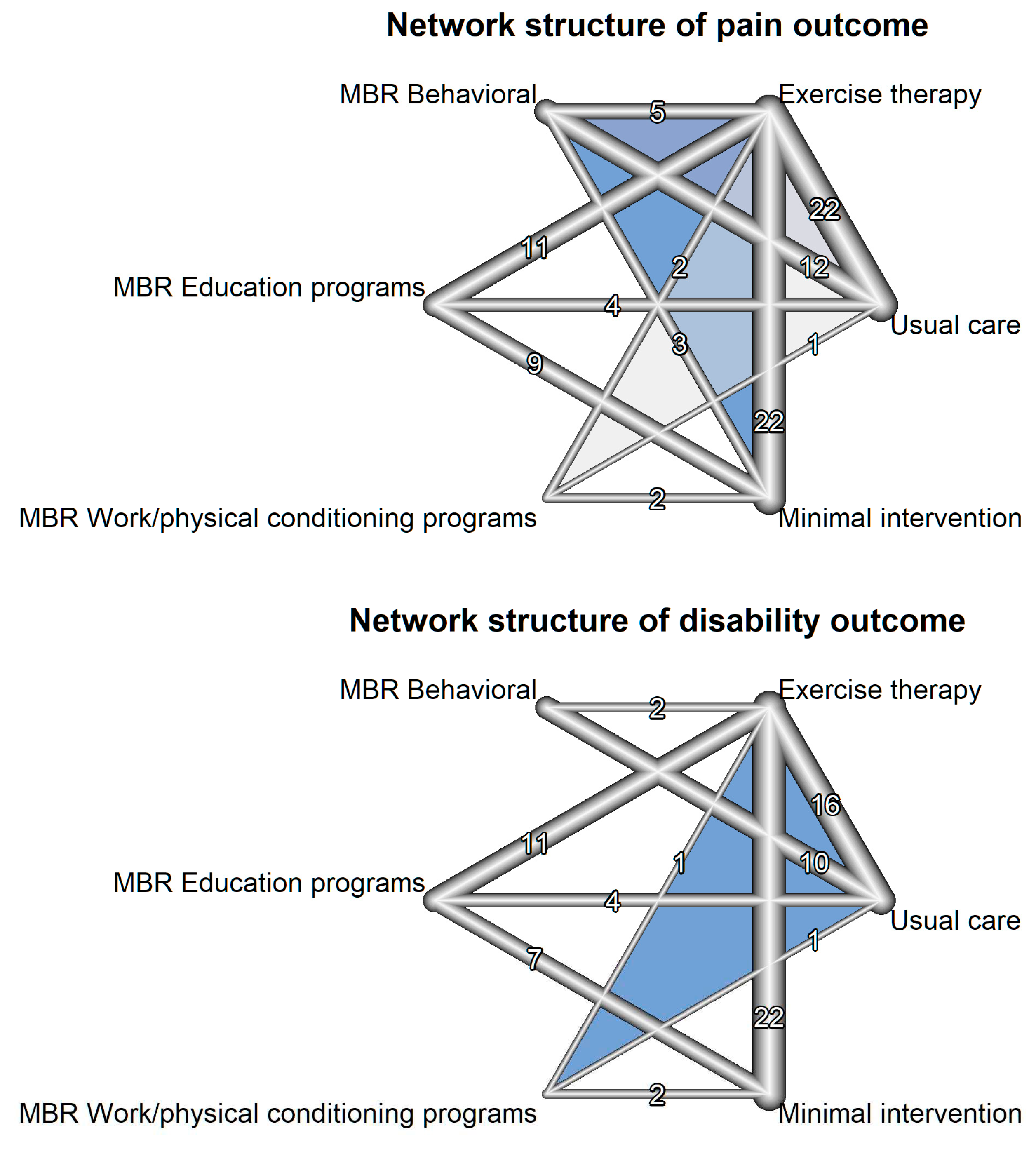

2.6. Geometry of the network

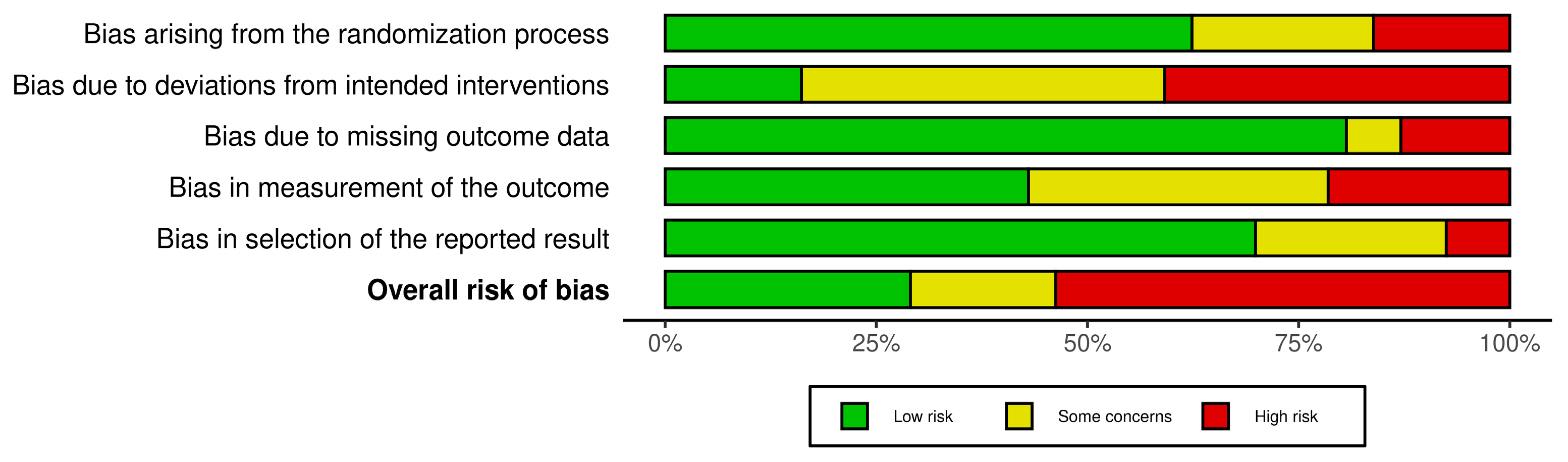

2.7. Risk of bias within individual studies and across studies

2.8. Summary measures

2.9. Planned methods of analysis

2.10. Assessment of Heterogeneity & Inconsistency

2.11. Additional analyses

3. Results

3.1. Study selection & Included studies charateristics

3.2. Presentation of network structure & summary of network geometry

3.3. Risk of bias within studies

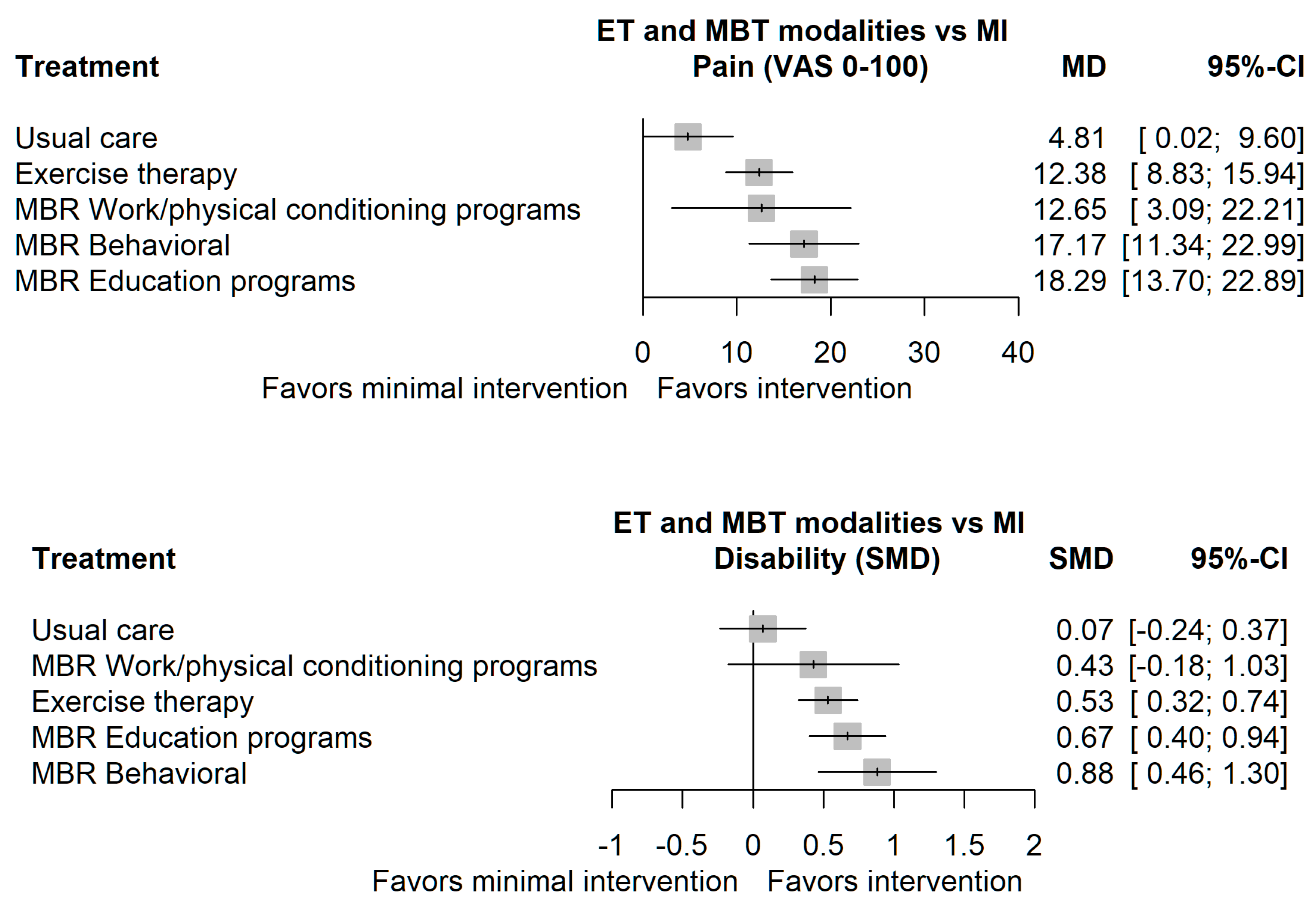

3.4. Results of comparions & synthesis of results

3.5. Exploration for heterogeneity & inconsistency

3.6. Risk of bias across studies

3.7. Results of additional analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations for stakeholders

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allegri, M.; Montella, S.; Salici, F.; Valente, A.; Marchesini, M.; Compagnone, C.; Baciarello, M.; Manferdini, M.E.; Fanelli, G. Mechanisms of Low Back Pain: A Guide for Diagnosis and Therapy. F1000Research 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meucci, R.D.; Fassa, A.G.; Faria, N.M.X. Prevalence of Chronic Low Back Pain: Systematic Review. Rev. Saúde Pública 2015, 49, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Social Report 2023: Leaving No One Behind In An Ageing World. Available online: http://desapublications.un.org/publications/world-social-report-2023-leaving-no-one-behind-ageing-world (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Burden of Low Back Pain, 1990-2020, Its Attributable Risk Factors, and Projections to 2050: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e316–e329. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatoye, F.; Gebrye, T.; Ryan, C.G.; Useh, U.; Mbada, C. Global and Regional Estimates of Clinical and Economic Burden of Low Back Pain in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.Z.; Fritz, J.M.; Silfies, S.P.; Schneider, M.J.; Beneciuk, J.M.; Lentz, T.A.; Gilliam, J.R.; Hendren, S.; Norman, K.S. Interventions for the Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: Revision 2021. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 51, CPG1–CPG60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhowimel, A.; AlOtaibi, M.; Radford, K.; Coulson, N. Psychosocial Factors Associated with Change in Pain and Disability Outcomes in Chronic Low Back Pain Patients Treated by Physiotherapist: A Systematic Review. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6, 2050312118757387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.B.; Maher, C.G.; Pinto, R.Z.; Traeger, A.C.; Lin, C.-W.C.; Chenot, J.-F.; van Tulder, M.; Koes, B.W. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Non-Specific Low Back Pain in Primary Care: An Updated Overview. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2018, 27, 2791–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, F.G.; Whelan, K.; van der Beek, A.J.; van der Es-Lambeek, L.C.; Ojajärvi, A.; Verbeek, J.H. Physical Conditioning as Part of a Return to Work Strategy to Reduce Sickness Absence for Workers with Back Pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD001822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamper, S.J.; Apeldoorn, A.T.; Chiarotto, A.; Smeets, R.J.E.M.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Guzman, J.; van Tulder, M.W. Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation for Chronic Low Back Pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD000963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjalainen, K.; Malmivaara, A.; Pohjolainen, T.; Hurri, H.; Mutanen, P.; Rissanen, P.; Pahkajärvi, H.; Levon, H.; Karpoff, H.; Roine, R. Mini-Intervention for Subacute Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Spine 2003, 28, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianola, S.; Andreano, A.; Castellini, G.; Moja, L.; Valsecchi, M.G. Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation for Chronic Low Back Pain: The Need to Present Minimal Important Differences Units in Meta-Analyses. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, B.; Salanti, G.; Caldwell, D.M.; Chaimani, A.; Schmid, C.H.; Cameron, C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Straus, S.; Thorlund, K.; Jansen, J.P.; et al. The PRISMA Extension Statement for Reporting of Systematic Reviews Incorporating Network Meta-Analyses of Health Care Interventions: Checklist and Explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurak, I.; Delaš, K.; Erjavec, L.; Locatelli, I. Network Meta-Analysis of Exercise Therapy and Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation for Chronic Low Back Pain 2022.

- van Erp, R.M.A.; Huijnen, I.P.J.; Jakobs, M.L.G.; Kleijnen, J.; Smeets, R.J.E.M. Effectiveness of Primary Care Interventions Using a Biopsychosocial Approach in Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Pain Pract. Off. J. World Inst. Pain 2019, 19, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veritas Health Innovation Covidence Systematic Review Software Available online: www.covidence.org.

- Hayden, J.A.; Ellis, J.; Ogilvie, R.; Malmivaara, A.; Tulder, M.W. van Exercise Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-Bias VISualization (Robvis): An R Package and Shiny Web App for Visualizing Risk-of-Bias Assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. Ranking Treatments in Frequentist Network Meta-Analysis Works without Resampling Methods. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julian PT Higgins; Tianjing Li; Jonathan J Deeks Chapter 6: Choosing Effect Measures and Computing Estimates of Effect. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; 2022.

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Papakonstantinou, T.; Salanti, G.; Efthimiou, O.; Schwarzer, G. Netmeta: An R Package for Network Meta-Analysis Using Frequentist Methods. J. Stat. Softw. 2023, 106, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.A.; Maharaj, S.S.; Van Oosterwijck, J. Effects of Dynamic Stabilization Exercises and Muscle Energy Technique on Selected Biopsychosocial Outcomes for Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Scand J Pain 2021, 21, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almhdawi, K.A.; Obeidat, D.S.; Kanaan, S.F.; Oteir, A.O.; Mansour, Z.M.; Alrabbaei, H. Efficacy of an Innovative Smartphone Application for Office Workers with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Rehabil 2020, 34, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvani E; Shirvani H; Shamsoddini A Neuromuscular Exercises on Pain Intensity, Functional Disability, Proprioception, and Balance of Military Personnel with Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Can. Chiropr. Assoc. 2021 Aug652193-206 2021.

- Barone Gibbs, B.; Hergenroeder, A.; Perdomo, S.; Kowalsky, R.; Delitto, A.; Jakicic, J. Reducing Sedentary Behaviour to Decrease Chronic Low Back Pain: The Stand Back Randomised Trial. Occup. Env. Med. 2018, 75, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodes Pardo, G.; Lluch Girbes, E.; Roussel, N.A.; Gallego Izquierdo, T.; Jimenez Penick, V.; Pecos Martin, D. Pain Neurophysiology Education and Therapeutic Exercise for Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borys, C.; Lutz, J.; Strauss, B.; Altmann, U. Effectiveness of a Multimodal Therapy for Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Regarding Pre-Admission Healthcare Utilization. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.O.P.; Maher, C.G.; Latimer, J.; Hodges, P.W.; Herbert, R.D.; Refshauge, K.M.; McAuley, J.H.; Jennings, M.D. Motor Control Exercise for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, C.; Romiti, D. Effectiveness of Back School Program versus Hydrotherapy in Elderly Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Acta Biomed 2014, 85, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Diaz, D.; Romeu, M.; Velasco-Gonzalez, C.; Martinez-Amat, A.; Hita-Contreras, F. The Effectiveness of 12weeks of Pilates Intervention on Disability, Pain and Kinesiophobia in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta-Vargas, A.I.; Adams, N.; Salazar, J.A.; Belles, A.; Hazañas, S.; Arroyo-Morales, M. Deep Water Running and General Practice in Primary Care for Non-Specific Low Back Pain versus General Practice Alone: Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Rheumatol. 2012, 31, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnall, B.D.; Roy, A.; Chen, A.L.; Ziadni, M.S.; Keane, R.T.; You, D.S.; Slater, K.; Poupore-King, H.; MacKey, I.; Kao, M.-C.; et al. Comparison of a Single-Session Pain Management Skills Intervention with a Single-Session Health Education Intervention and 8 Sessions of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 13401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasahayam, A.J.; Siang Lim, C.K.; Goh, M.R.; Lim You, J.P.; Pua, P.Y. Delivering a Back School Programme with a Cognitive Behavioural Modification: A Randomised Pilot Trial on Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain and Functional Disability. Proc Singap. Healthc. 2014, 23, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donzelli, S.; Di Domenica, F.; Cova, A.M.; Galletti, R.; Giunta, N. Two Different Techniques in the Rehabilitation Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. Medicophys. 2006, 42, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour, N.; Thamsborg, G.; Oefeldt, A.; Lundsgaard, C.; Stender, S. Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized, Clinical Trial Comparing Group-Based Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation and Intensive Individual Therapist-Assisted Back Muscle Strengthening Exercises. Spine 2010, 35, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmus, D.; Unal, M.; Kuru, O. How Effective Is a Modified Exercise Program on Its Own or with Back School in Chronic Low Back Pain? A Randomized-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2014, 27, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, H.; Klaber Moffett, J.A.; Moser, J.S.; Fairbank, J.C. Randomised Controlled Trial for Evaluation of Fitness Programme for Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. BMJ 1995, 310, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.N.; Costa, L.D.C.M.; Hancock, M.J.; De Souza, F.S.; de Oliveira Gomes, G.V.F.; De Almeida, M.O.; Costa, L.O.P. McKenzie Method of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy Was Slightly More Effective than Placebo for Pain, but Not for Disability, in Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomised Placebo Controlled Trial with Short and Longer Term Follow-u. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, T.; Refshauge, K.; McAuley, J.; Hubscher, M.; Goodall, S.; Smith, L. Combined Education and Patient-Led Goal Setting Intervention Reduced Chronic Low Back Pain Disability and Intensity at 12 Months: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 1424–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, E.; Wileman, V.; Galea Holmes, M.; McCracken, L.M.; Norton, S.; Moss-Morris, R.; Noonan, S.; Barcellona, M.; Critchley, D. Physical Therapy Informed by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (PACT) Versus Usual Care Physical Therapy for Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pain 2020, 21, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldby, L.J.; Moore, A.P.; Doust, J.; Trew, M.E. A Randomized Controlled Trial Investigating the Efficiency of Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy on Chronic Low Back Disorder. Spine Phila Pa 1976 2006, 31, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.M.; Maher, C.G.; Lam, P.; Ferreira, M.; Latimer, J. Tai Chi Exercise for Treatment of Pain and Disability in People with Persistent Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Care Res 2011, 63, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haufe S; Wiechmann K; Stein L; Kuck M; Smith A; Meineke S; Zirkelbach Y; Rodriguez Duarte S; Drupp M; Tegtbur U Low-Dose, Non-Supervised, Health Insurance Initiated Exercise for the Treatment and Prevention of Chronic Low Back Pain in Employees. Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2017 Jun126e0178585 2017.

- Highland, K.B.; Schoomaker, A.; Rojas, W.; Suen, J.; Ahmed, A.; Zhang, Z.; Carlin, S.F.; Calilung, C.E.; Kent, M.; McDonough, C.; et al. Benefits of the Restorative Exercise and Strength Training for Operational Resilience and Excellence Yoga Program for Chronic Low Back Pain in Service Members: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaromi, M.; Kukla, A.; Szilagyi, B.; Simon-Ugron, A.; Bobaly, V.K.; Makai, A.; Linek, P.; Acs, P.; Leidecker, E. Back School Programme for Nurses Has Reduced Low Back Pain Levels: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e895–e902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaromi, M.; Nemeth, A.; Kranicz, J.; Laczko, T.; Betlehem, J. Treatment and Ergonomics Training of Work-Related Lower Back Pain and Body Posture Problems for Nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, R.K.; Leboeuf-Yde, C.; Wedderkopp, N.; Sorensen, J.S.; Manniche, C. Rest versus Exercise as Treatment for Patients with Low Back Pain and Modic Changes. A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. BMC Med. 2012, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jousset, N.; Fanello, S.; Bontoux, L.; Dubus, V.; Billabert, C.; Vielle, B.; Roquelaure, Y.; Penneau-Fontbonne, D.; Richard, I. Effects of Functional Restoration versus 3 Hours per Week Physical Therapy: A Randomized Controlled Study. Spine 2004, 29, 487–493; discussion 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kääpä, E.H.; Frantsi, K.; Sarna, S.; Malmivaara, A. Multidisciplinary Group Rehabilitation versus Individual Physiotherapy for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Trial. Spine Phila Pa 1976 2006, 31, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, D.; Radha, S.; Smith, F.; Wardlaw, D.; Scott, N.; Rege, A.; Pope, M. Evaluation of Perifacet Injections and Paraspinal Muscle Rehabilitation in Treatment of Low Back Pain. A Randomised Controlled Trial. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2012, 14, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankaanpää, M.; Taimela, S.; Airaksinen, O.; Hänninen, O. The Efficacy of Active Rehabilitation in Chronic Low Back Pain. Effect on Pain Intensity, Self-Experienced Disability, and Lumbar Fatigability. Spine Phila Pa 1976 1999, 24, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Akhter, S.; Soomro, R.R.; Ali, S.S. The Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with General Exercises versus General Exercises Alone in the Management of Chronic Low Back Pain. Pak. J. Pharma Sci. 2014, 27, 1113–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Khodadad, B.; Letafatkar, A.; Hadadnezhad, M.; Shojaedin, S. Comparing the Effectiveness of Cognitive Functional Treatment and Lumbar Stabilization Treatment on Pain and Movement Control in Patients With Low Back Pain. Sports Health 2020, 12, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-S.; An, J.; Kim, J.-O.; Lee, M.-Y.; Lee, B.-H. Effects of Pain Neuroscience Education Combined with Lumbar Stabilization Exercise on Strength and Pain in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. 2022, 12, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Lee, J.; Oh, S.; Kim, S.; Yoon, B. Effectiveness of Simulated Horseback Riding for Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Sport Rehabil. 2020, 29, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofotolis, N.; Kellis, E. Effects of Two 4-Week Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation Programs on Muscle Endurance, Flexibility, and Functional Performance in Women with Chronic Low Back Pain. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koldaş Doğan, S.; Sonel Tur, B.; Kurtaiş, Y.; Atay, M.B. Comparison of Three Different Approaches in the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain. Clin. Rheumatol. 2008, 27, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Negi, M.P.S.; Sharma, V.P.; Shukla, R.; Dev, R.; Mishra, U.K. Efficacy of Two Multimodal Treatments on Physical Strength of Occupationally Subgrouped Male with Low Back Pain. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2009, 22, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, V.P.; Negi, M.P.S. Efficacy of Dynamic Muscular Stabilization Techniques (DMST) over Conventional Techniques in Rehabilitation of Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 2651–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuvacic, G.; Fratini, P.; Padulo, J.; Antonio, D.I.; De Giorgio, A. Effectiveness of Yoga and Educational Intervention on Disability, Anxiety, Depression, and Pain in People with CLBP: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Complement Ther. Clin. Pr. 2018, 31, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, M.; Scherbe, S.; Cicholas, B. Randomized Controlled Trial on the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavior Group Therapy in Chronic Back Pain Patients. J. Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2014, 27, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masharawi, Y.; Nadaf, N. The Effect of Non-Weight Bearing Group-Exercising on Females with Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Single Blind Controlled Pilot Study. J. Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2013, 26, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazloum, V.; Sahebozamani, M.; Barati, A.; Nakhaee, N.; Rabiei, P. The Effects of Selective Pilates versus Extension-Based Exercises on Rehabilitation of Low Back Pain. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2018, 22, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaskey, M.A.; Wirth, B.; Schuster-Amft, C.; de Bruin, E.D. Postural Sensorimotor Training versus Sham Exercise in Physiotherapy of Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: An Exploratory Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalsen, A.; Jeitler, M.; Kessler, C.S.; Steckhan, N.; Robens, S.; Ostermann, T.; Kandil, F.I.; Stankewitz, J.; Berger, B.; Jung, S.; et al. Yoga, Eurythmy Therapy and Standard Physiotherapy (YES-Trial) for Patients With Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Three-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pain 2021, 22, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, G.C.; Costa, L.O.; Galvanin, T.; Cabral, C.M. Efficacy of the Addition of Modified Pilates Exercises to a Minimal Intervention in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monticone, M.; Ambrosini, E.; Rocca, B.; Magni, S.; Brivio, F.; Ferrante, S. A Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Programme Improves Disability, Kinesiophobia and Walking Ability in Subjects with Chronic Low Back Pain: Results of a Randomised Controlled Pilot Study. Eur. Spine J. 2014, 23, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monticone, M.; Ambrosini, E.; Rocca, B.; Cazzaniga, D.; Liquori, V.; Foti, C. Group-Based Task-Oriented Exercises Aimed at Managing Kinesiophobia Improved Disability in Chronic Low Back Pain. Eur. J. Pain. 2016, 20, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monticone, M.; Ferrante, S.; Rocca, B.; Baiardi, P.; Dal Farra, F.; Foti, C. Effect of a Long-Lasting Multidisciplinary Program on Disability and Fear-Avoidance Behaviors in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morone, G.; Iosa, M.; Paolucci, T.; Fusco, A.; Alcuri, R.; Spadini, E.; Saraceni, V.M.; Paolucci, S. Efficacy of Perceptive Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain through a New Tool: A Randomized Clinical Study. Clin. Rehabil. 2012, 26, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morone, G.; Paolucci, T.; Alcuri, M.R.; Vulpiani, M.C.; Matano, A.; Bureca, I.; Paolucci, S.; Saraceni, V.M. Quality of Life Improved by Multidisciplinary Back School Program in Patıents with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Single Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 47, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moseley, L. Combined Physiotherapy and Education Is Efficacious for Chronic Low Back Pain. Aust. J. Physiother. 2002, 48, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambi, G.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Alsubaie, S.F.; Saleh, A.K.; Verma, A.; Abdelaziz, M.A.; Alkathiry, A.A. Short-Term Psychological and Hormonal Effects of Virtual Reality Training on Chronic Low Back Pain in Soccer Players. J. Sport Rehabil. 2021, 30, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narouei, S.; Barati, A.H.; Akuzawa, H.; Talebian, S.; Ghiasi, F.; Akbari, A.; Alizadeh, M.H. Effects of Core Stabilization Exercises on Thickness and Activity of Trunk and Hip Muscles in Subjects with Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2020, 24, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassif, H.; Brosset, N.; Guillaume, M.; Delore-Milles, E.; Tafflet, M.; Buchholz, F.; Toussaint, J.-F. Evaluation of a Randomized Controlled Trial in the Management of Chronic Lower Back Pain in a French Automotive Industry: An Observational Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natour, J.; Cazotti, Ld. e A.; Ribeiro L.H.; Baptista A.S.; Jones A. Pilates Improves Pain, Function and Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, M.K.; Wilson, P.H.; Goyen, J. Operant-Behavioural and Cognitive-Behavioural Treatment for Chronic Low Back Pain. BEHAV RES THER 1991, 29, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keeffe, M.; O’Sullivan, P.; Purtill, H.; Bargary, N.; O’Sullivan, K. Cognitive Functional Therapy Compared with a Group-Based Exercise and Education Intervention for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT). Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okafor UA; Solanke TA; Akinbo SR; Odebiyi DO Effect of Aerobic Dance on Pain, Functional Disability and Quality of Life on Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. South Afr. J. Physiother. 201268311-14 2012.

- Patti, A.; Bianco, A.; Paoli, A.; Messina, G.; Montalto, M.A.; Bellafiore, M.; Battaglia, G.; Iovane, A.; Palma, A. Pain Perception and Stabilometric Parameters in People with Chronic Low Back Pain after a Pilates Exercise Program: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Medicine 2016, 95, e2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paungmali, A.; Joseph, L.H.; Sitilertpisan, P.; Pirunsan, U.; Uthaikhup, S. Lumbopelvic Core Stabilization Exercise and Pain Modulation Among Individuals with Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain. Pain Pr. 2017, 17, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrozzi, M.J.; Leaver, A.; Ferreira, P.H.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Jones, M.K.; Mackey, M.G. Addition of MoodGYM to Physical Treatments for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chiropr Man Thera 2019, 27, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phattharasupharerk, S.; Purepong, N.; Eksakulkla, S.; Siriphorn, A. Effects of Qigong Practice in Office Workers with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Control Trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2019, 23, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, D.; Cruz, E.B.; Caeiro, C. Aquatic Exercise and Pain Neurophysiology Education versus Aquatic Exercise Alone for Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polaski, A.M.; Phelps, A.L.; Smith, T.J.; Helm, E.R.; Morone, N.E.; Szucs, K.A.; Kostek, M.C.; Kolber, B.J. Integrated Meditation and Exercise Therapy: A Randomized Controlled Pilot of a Combined Nonpharmacological Intervention Focused on Reducing Disability and Pain in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiei, P.; Sheikhi, B.; Letafatkar, A. Comparing Pain Neuroscience Education Followed by Motor Control Exercises With Group-Based Exercises for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Pr. 2021, 21, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche-Leboucher, G.; Petit-Lemanac’H, A.; Bontoux, L.; Dubus-Bausiere, V.; Parot-Shinkel, E.; Fanello, S.; Penneau-Fontbonne, D.; Fouquet, N.; Legrand, E.; Roquelaure, Y.; et al. Multidisciplinary Intensive Functional Restoration versus Outpatient Active Physiotherapy in Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Spine 2011, 36, 2235–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydeard, R.; Leger, A.; Smith, D. Pilates-Based Therapeutic Exercise: Effect on Subjects with Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain and Functional Disability: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Orthop Sports Phys. Ther. 2006, 36, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.O.B.D.; Castro, J.B.P.; Nunes, R.A.M.; Silva, G.C.P.S.M.D.; Oliveira, J.G.M.; Lima, V.P.; Vale, R.G.S. Effects of Two Training Programs on Health Variables in Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Pain Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saper, R.B.; Lemaster, C.; Delitto, A.; Sherman, K.J.; Herman, P.M.; Sadikova, E.; Stevans, J.; Keosaian, J.E.; Cerrada, C.J.; Femia, A.L.; et al. Yoga, Physical Therapy, or Education for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Noninferiority Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saper, R.B.; Sherman, K.J.; Cullum-Dugan, D.; Davis, R.B.; Phillips, R.S.; Culpepper, L. Yoga for Chronic Low Back Pain in a Predominantly Minority Population: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Altern Ther. Health Med. 2009, 15, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schinhan, M.; Neubauer, B.; Pieber, K.; Gruber, M.; Kainberger, F.; Castellucci, C.; Olischar, B.; Maruna, A.; Windhager, R.; Sabeti-Aschraf, M. Climbing Has a Positive Impact on Low Back Pain: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2016, 26, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, M.; Sarrafzadeh, J.; Jamshidi, A.; Zarabi, V.; Pourahmadi, M.R. The Effect of Core Stability and General Exercise on Abdominal Muscle Thickness in Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain Using Ultrasound Imaging. Physiother Theory Pr. 2016, 32, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaughnessy, M.; Caulfield, B. A Pilot Study to Investigate the Effect of Lumbar Stabilisation Exercise Training on Functional Ability and Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2004, 27, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, K.J.; Cherkin, D.C.; Wellman, R.D.; Cook, A.J.; Hawkes, R.J.; Delaney, K.; Deyo, R.A. A Randomized Trial Comparing Yoga, Stretching, and a Self-Care Book for Chronic Low Back Pain. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 2019–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilbrook, H.E.; Cox, H.; Hewitt, C.E.; Kang’ombe, A.R.; Chuang, L.-H.; Jayakody, S.; Aplin, J.D.; Semlyen, A.; Trewhela, A.; Watt, I.; et al. Yoga for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torstensen, T.A.; Ljunggren, A.E.; Meen, H.D.; Odland, E.; Mowinckel, P.; Geijerstam, S.A. Efficiency and Costs of Medical Exercise Therapy, Conventional Physiotherapy, and Self-Exercise in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Pragmatic, Randomized, Single-Blinded, Controlled Trial with 1-Year Follow- Up. Spine 1998, 23, 2616–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tritilanunt, T.; Wajanavisit, W. The Efficacy of an Aerobic Exercise and Health Education Program for Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Med. Assoc. Thai 2001, 84 Suppl 2, S528–533. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.A.; Clancy, S.; McQuade, K.J.; Cardenas, D.D. Effectiveness of Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Component Analysis. J CONSULT CLIN PSYCHOL 1990, 58, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenza, M.C.; Rodriguez-Torres, J.; Cabrera-Martos, I.; Diaz-Pelegrina, A.; Aguilar-Ferrandiz, M.E.; Castellote-Caballero, Y. Results of a Pilates Exercise Program in Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Roer, N.; Van Tulder, M.; Barendse, J.; Knol, D.; Van Mechelen, W.; De Vet, H. Intensive Group Training Protocol versus Guideline Physiotherapy for Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. Spine J. 2008, 17, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Erp, R.M.A.; Huijnen, I.P.J.; Ambergen, A.W.; Verbunt, J.A.; Smeets, R.J.E.M. Biopsychosocial Primary Care versus Physiotherapy as Usual in Chronic Low Back Pain: Results of a Pilot-Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Physiother. 2021, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibe Fersum, K.; O’Sullivan, P.; Skouen, J.S.; Smith, A.; Kvale, A. Efficacy of Classification-Based Cognitive Functional Therapy in Patients with Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Pain 2013, 17, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.M.R.; Hermens, H.J.; Wever, D.; Gorter, M.; Rinket, J.; Ijzerman, M.J. Differences in Outcome of a Multidisciplinary Treatment between Subgroups of Chronic Low Back Pain Patients Defined Using Two Multiaxial Assessment Instruments: The Multidimensional Pain Inventory and Lumbar Dynamometry. Clin. Rehabil. 2004, 18, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walti, P.; Kool, J.; Luomajoki, H. Short-Term Effect on Pain and Function of Neurophysiological Education and Sensorimotor Retraining Compared to Usual Physiotherapy in Patients with Chronic or Recurrent Non-Specific Low Back Pain, a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waseem, M.; Karimi, H.; Gilani, S.A.; Hassan, D. Treatment of Disability Associated with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain Using Core Stabilization Exercises in Pakistani Population. J. Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2019, 32, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weifen, W.; Muheremu, A.; Chaohui, C.; Md, L.W.; Lei, S. Effectiveness of Tai Chi Practice for Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain on Retired Athletes: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Musculoskelet Pain 2013, 21, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams A; Wiggers J; O’Brien KM; Wolfenden L; Yoong SL; Hodder RK; Lee H; Robson EK; McAuley JH; Haskins R; et al. The Effectiveness of a Healthy Lifestyle Intervention, for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Pain 2018 Jun15961137-1146 2018.

- Williams, K.; Abildso, C.; Steinberg, L.; Doyle, E.; Epstein, B.; Smith, D.; Hobbs, G.; Gross, R.; Kelley, G.; Cooper, L. Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Efficacy of Iyengar Yoga Therapy on Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine 2009, 34, 2066–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-A.; Wu, P.-K.; Ho, S.-Y.; Chou, C.-Y.; Huang, S.-F. Pilates-Based Core Exercise Improves Health-Related Quality of Life in People Living with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Pilot Study. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2021, 27, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadro, J.R.; Shirley, D.; Simic, M.; Mousavi, S.J.; Ceprnja, D.; Maka, K.; Sung, J.; Ferreira, P. Video-Game-Based Exercises for Older People With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlledtable Trial (GAMEBACK). Phys. Ther. 2019, 99, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wan, L.; Wang, X. The Effect of Health Education in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Int. Med. Res. 2014, 42, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Yu, Q.; Lo, W.L.A.; Li, T.; Wang, C.H. Does M-Health-Based Exercise (Guidance plus Education) Improve Efficacy in Patients with Chronic Low-Back Pain? A Preliminary Report on the Intervention’s Significance. Trials 2022, 23, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, X.; Xiao, T.; Liu, X.; Yeung, A.S.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, Q. The Effects of Tai Chi Chuan Versus Core Stability Training on Lower-Limb Neuromuscular Function in Aging Individuals with Non-Specific Chronic Lower Back Pain. Med. Kaunas 2019, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Chu, H. Quantifying Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis. Biometrics 2018, 74, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieminen, L.K.; Pyysalo, L.M.; Kankaanpää, M.J. Prognostic Factors for Pain Chronicity in Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. PAIN Rep. 2021, 6, e919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population characteristics | Mean (min, max) | # of studies | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male [%] | 31.18% | 72 | 6476 |

| Age [years] | 44.61 (21.4 to 73.63) | 88 | 7432 |

| BMI | 25.89 (20.77 to 35) | 61 | 5075 |

| Symptom duration [months] | 53.6 (5.3 to 222) | 40 | 4101 |

| Intervention duration [weeks] | 9.01 (1 to 24) | 84 | 7163 |

| # of hours per week | 2.3 (0.12 to 30) | 80 | 6867 |

| MI | . | 14.56 (10.41; 18.71) |

14.03 (-0.59; 28.65) |

9.96 (-1.68; 21.59) |

14.06 (7.43; 20.68) |

| 4.81 (0.02; 9.60) |

UC | 9.08 (4.90; 13.27) |

0.20 (-17.86; 18.26) |

11.43 (5.59; 17.28) |

11.26 (1.62; 20.90) |

| 12.38 (8.83; 15.94) |

7.57 (3.95; 11.20) |

ET | 1.53 (11.59; 14.64) |

10.27 (1.78; 18.77) |

9.99 (4.17; 15.80) |

| 12.65 (3.09; 22.21) |

7.84 (-1.99; 17.68) |

0.27 (-9.19; 9.73) |

MBR-WR | . | . |

| 17.17 (11.34; 22.99) |

12.36 (7.52; 17.20) |

4.79 (-0.36; 9.93) |

4.52 (-6.02; 15.05) |

MBR-BE | . |

| 18.29 (13.70; 22.89) |

13.49 (8.42; 18.55) |

5.91 (1.67; 10.16) |

5.64 (-4.49; 15.77) |

1.13 (-5.19; 7.44) |

MBR-ED |

| MI | . | 0.55 (-0.24; 1.35) |

0.66 (0.42; 0.89) |

0.28 (-0.12; 0.68) |

. |

| 0.07 (-0.24; 0.37) |

UC | -0.11 (-1.15; 0.92) |

0.44 (0.17; 0.71) |

0.73 (0.17; 1.30) |

0.81 (0.46; 1.16) |

| 0.43 (-0.18; 1.03) |

0.36 (-0.28; 0.99) |

MBR-WR | -0.05 (-1.10; 0.99) |

. | . |

| 0.53 (0.32; 0.74) |

0.46 (0.23; 0.70) |

0.10 (-0.51; 0.72) |

ET | 0.36 (0.03; 0.69) |

0.37 (-0.36; 1.10) |

| 0.67 (0.40; 0.94) |

0.60 (0.29; 0.91) |

0.24 (-0.40; 0.89) |

0.14 (-0.11; 0.39) |

MBR-ED | . |

| 0.88 (0.46; 1.30) |

0.81 (0.49; 1.13) |

0.45 (-0.24; 1.15) |

0.35 (-0.02; 0.72) |

0.21 (-0.21; 0.64) |

MBR-BE |

| Pain outcome | Disability outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Treatment | P-score | P-score | Treatment | Rank |

| 1 | MBR-ED | 0.899 | 0.940 | MBR-BE | 1 |

| 2 | MBR-BE | 0.826 | 0.761 | MBR-ED | 2 |

| 3 | MBR-WR | 0.559 | 0.559 | ET | 3 |

| 4 | ET | 0.503 | 0.496 | MBR-WR | 4 |

| 5 | UC | 0.207 | 0.161 | UC | 5 |

| 6 | MI | 0.006 | 0.082 | MI | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).