Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Analyses

2.3.1. Microbiological Analysis

2.3.2. Sensory Analysis

2.3.3. Volatile Organic Compound Identification

2.3.4. Allyl-Isothiocyanate Quantification

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

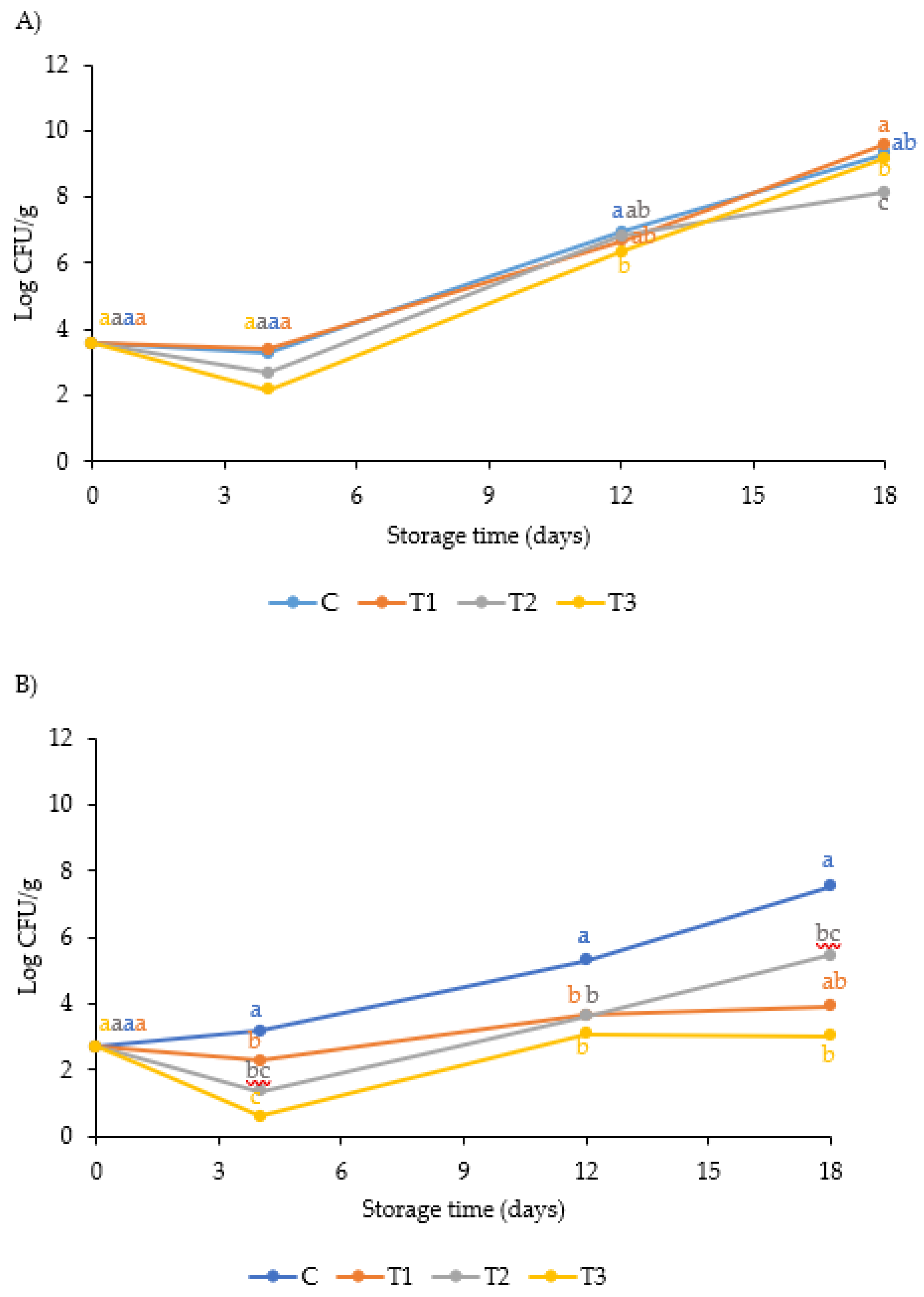

3.1. Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Activity of AITC

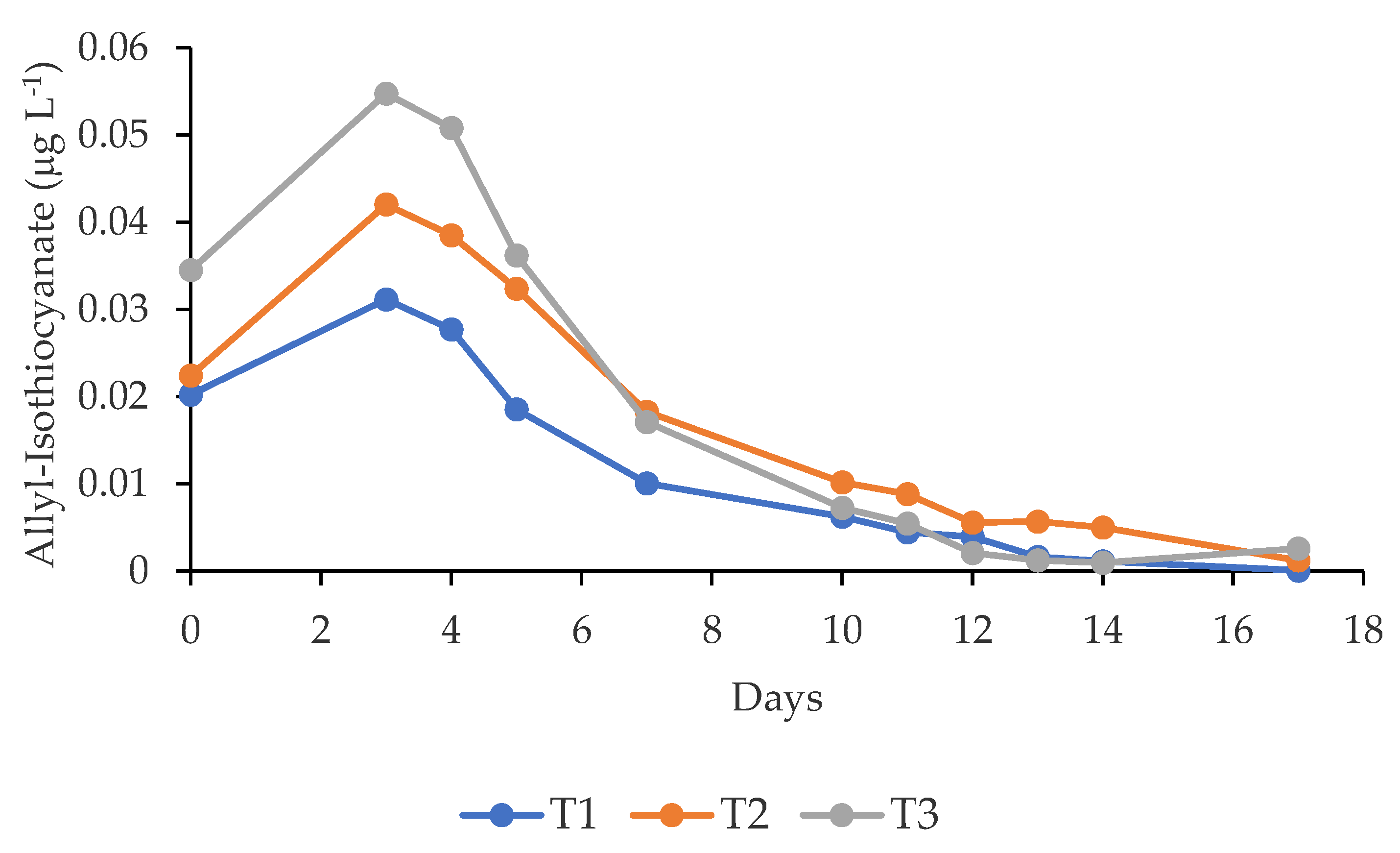

3.2. Allyl-Isothiocyanate Released from Mustard Seeds

3.3. Sensory Aroma of Tench During Storage Time

3.4. Volatile Compound Aroma of Tench During Storage Time

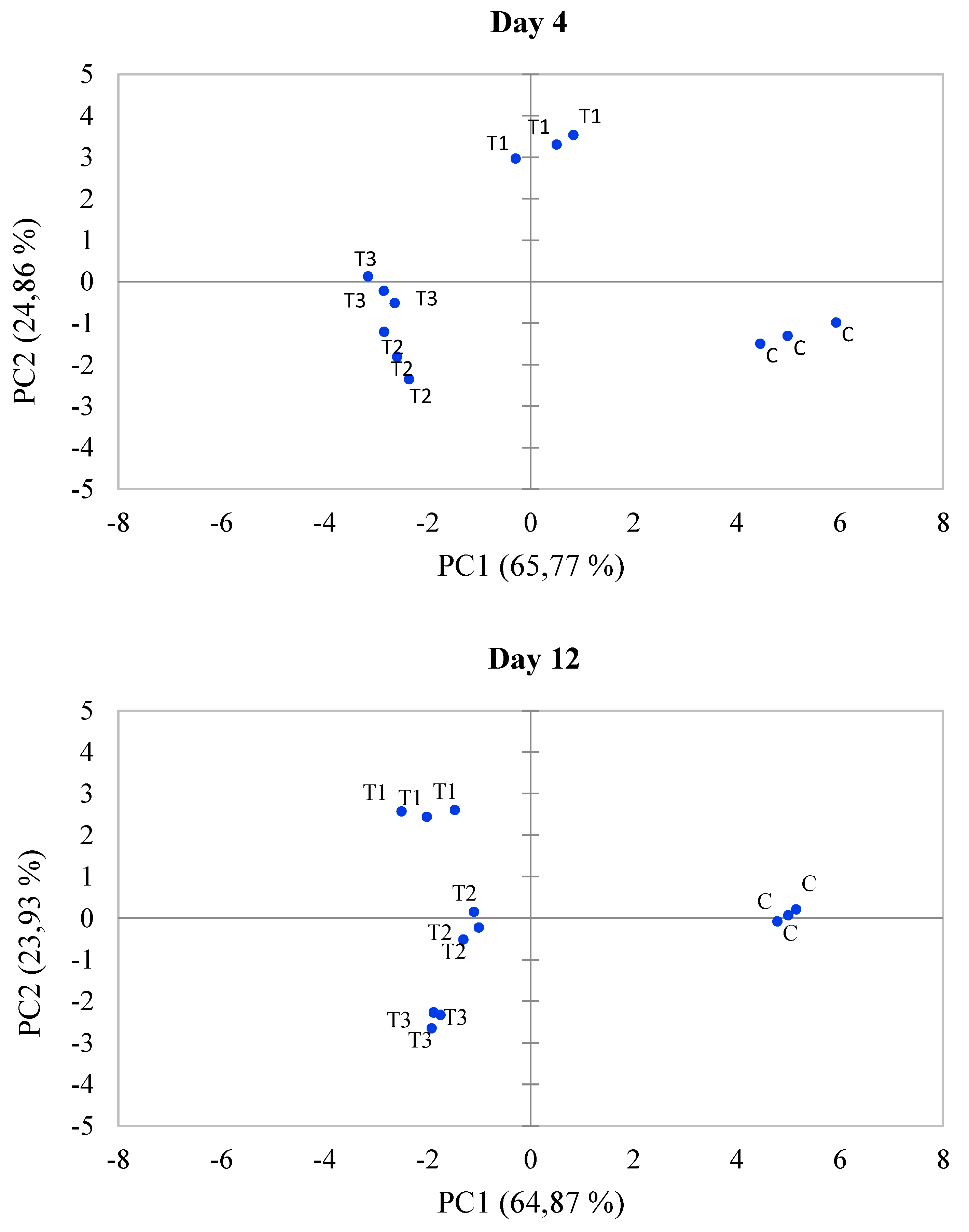

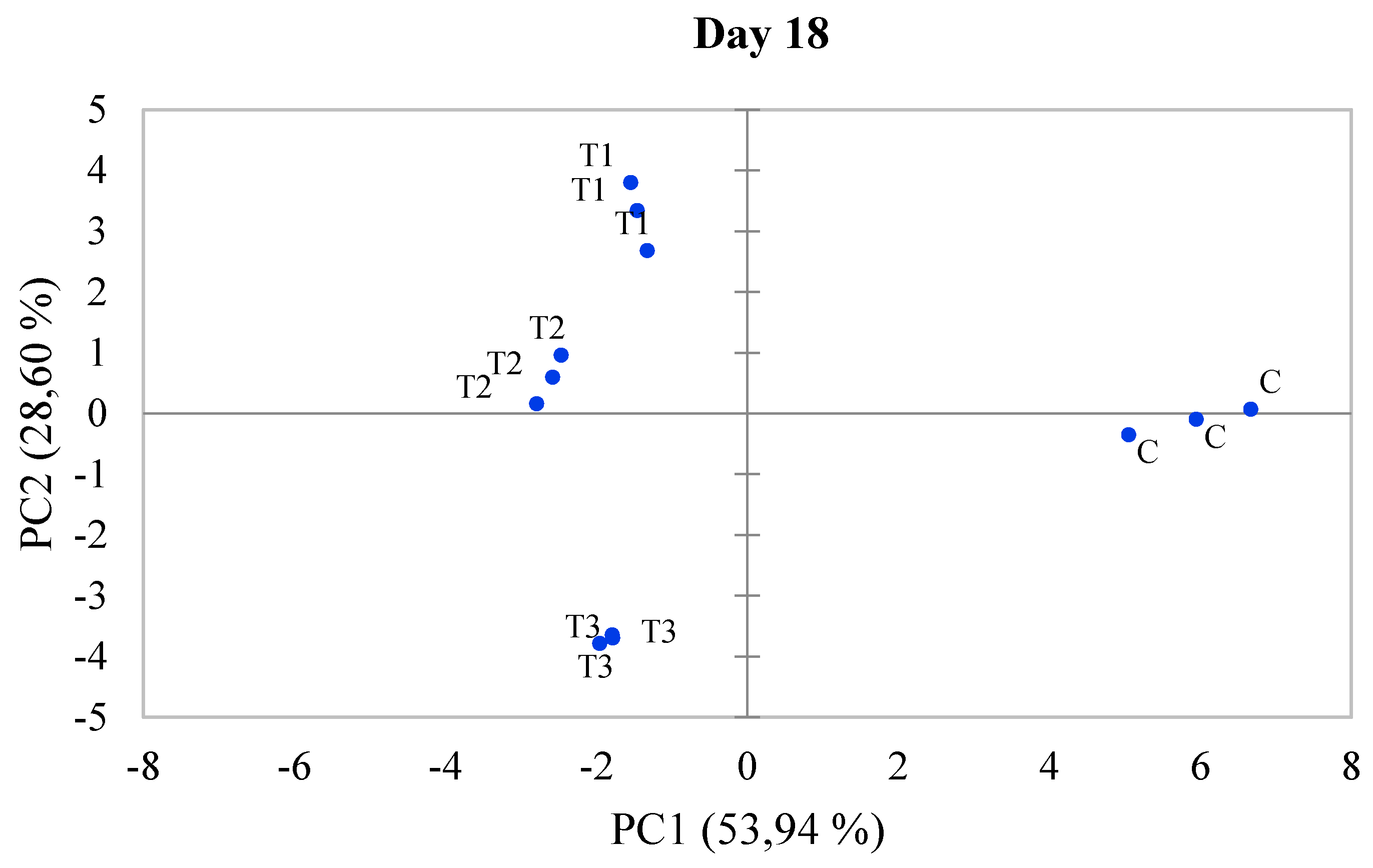

3.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AITC | Allyl Isothiocyanate |

| AMMS | Aerobic Mesophilic Microorganisms |

| BHT | Butylated Hydroxytoluene |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| TCMs | Total Coliform Microorganisms |

References

- Cantillo, J.; Martín, J.; Román, C. Determinants of fishery and aquaculture products consumption at home in the EU28. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Allison, E.H.; Beard, T.D.; Arlinghaus, R.; Arthington, A.H.; Bartley, D.M.; Cowx, I.G.; Fuentevilla, C.; Leonard, N.J.; Lorenzen, K.; Lynch, A.J.; Nguyen, V.M.; Young, S-J.; Taylor, W.W. On the sustainability of inland fisheries: finding a future for the forgotten. Ambio 2016, 45, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, R.; Guillen, J.; García, I.L.; Asche, F.; Garlock, T.; Kreiss, C. M…., Tveteras, R. An analysis of the European aquaculture industry using the aquaculture performance indicators. Aquac. Econ. Mgmt 2025, 29, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, 2022. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. Rome, Italy. ISBN:978-92-5-136364-5.

- CFP, 2022. Common fisheries policy, European Commission. https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/policy/common-fisheries-policy-cfp_en.

- Kottelat, M.; Freyhof, J. Handbook of European freshwater fishes 2007. ISBN 978-2-8399-0298-4.

- Karaiskou, N.; Gkagkavouzis, K.; Minoudi, S.; Botskaris, D.; Markou, K.; Kalafatakis, S.; Antonopoulou, E.; Triantafyllidis, A. Genetic structure and divergence of Tinca tinca European populations. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 97, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Fatle, F.A.; Meleg, E.E.; Sallai, Z.; Szabó, G.; Várkonyi, E.; Urbányi, B.; Kovács, B.; Molnár, T.; Lehoczky, I. Genetic structure and diversity of native tench (Tinca tinca L. 1758) populations in Hungary - Establishment of basic knowledge base for a breeding program. Diversity 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AESAN/BEDCA, 2010. Base de Datos Española de Composición de Alimentos. https://www.bedca.net/bdpub/.

- Kolek, L.; Inglot, M. Integrated cage-pond carp farming for increased aquaculture production. Fish. Aquat. Life 2023, 31, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Gómez, M.J.; Barea-Ramos, J.D.; Ruiz-Canales, A.; Martín-Vertedor, D. A circular economy framework for Tinca tinca valorization for stuffed Spanish-style table olive. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghareeb, W.R.; Elhelaly, A.E.; Abdallah, D.; El-Sherbiny, H.; Darwish, W. Formation of biogenic amines in fish: dietary intakes and health risk assessment. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 3123–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfino, L.; Mattie, L.; Silva, M.; Araujo, M.; Tormen, L.; Bainy, E. Evaluation of moringa and Lavandula extracts as natural antioxidants in tilapia fish burger. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2023, 21, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnejad, S.; Nouri, M.; Safari, D.S. Obtaining of chickpea protein isolate and its application as coating enriched with essential oils from Satureja Hortensis and Satureja Mutica in egg at room temperature. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansche, F.S.; Kühn, C.; Nickel, M.; Rohn, S.; Dekker, M. Leaching and degradation kinetics of glucosinolates during boiling of Brassica oleracea vegetables and the formation of their breakdown products. Food Chem. 2018, 15, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, R.; Lim, L.T. Release of allyl isothiocyanate from mustard seed meal powder. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurek, M.; Laridon, Y.; Torrieri, E.; Guillard, V.; Pant, A.; Stramm, C.; Gontard, N.; Guillaume, C. A mathematical model for tailoring antimicrobial packaging material containing encapsulated volatile compounds. IFSET 2017, 42, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolino, D.; Giarratana, F.; Beninati, C.; Ziino, G.; Giuffrida, A.; Panebianco, A. Effects of allyl isothiocyanate on the shelf-life of Gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata) fillets. Czech J. Food Sci. 2016, 34, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, K.; Fernández-No, I.C.; Barros-Velázquez, J.; Gallardo, J.M.; Calo-Mata, P.; Cañas, B. Species differentiation of seafood spoilage and pathogenic gram-negative bacteria by MALDI-TOF mass fingerprinting. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 3169–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Decree 53/2013. Normas básicas aplicables para la protección de los animales utilizados en experimentación y otros fines científicos, incluyendo la docencia.

- Villanueva, N.D.M.; Petenate, A.J.; Silva, M.A.A.P. Performance of the hybrid hedonic scale as compared to the traditional hedonic, self-adjusting and ranking scales. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, R.; Martín-Tornero, E.; Lozano, J.; Boselli, E.; Arroyo, P.; Meléndez, F.; Martín-Vertedor, D. E-Nose discrimination of abnormal fermentations in Spanish-Style Green Olives. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morra, M.J.; Kirkegaard, J.A. Isothiocyanate release from soil-incorporated Brassica tissues. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walayat, N.; Tang, W.; Wang, X.; Yi, M.; Guo, L.; Ding, Y.; Liu, J.; Ahmad, I.; Ranjha, M.M.A.N. Quality evaluation of frozen and chilled fish: a review. eFood 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C. L.; Freitas, J. A.; Lourenço, L. F.; Araujo, E. A.; Joele, M. R. S. P. Microbiological contamination of surfaces in fish industry. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 8, 425–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bahurmiz, O.M.; Ahmad, R.; Ismail, N.; Adzitey, F.; Sulaiman, S.F. Antimicrobial activity of selected essential oils on Pseudomonas species associated with spoilage of fish with emphasis on cinnamon essential oil. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2020, 29, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Hong, H.; Zhang, L.; Luo, Y. Spoilage-related microbiota in fish and crustaceans during storage: research progress and future trends. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 252–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, K.; Friedrich, L.; Dalmadi, I.; Kisko, G. Evaluation of In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Bioactive Compounds and the Effect of Allyl-Isothiocyanate on Chicken Meat Quality under Refrigerated Conditions. App. Sci. 2023, 13, 10953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaimat, A. N.; Holley, R. A. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes on Cooked Cured Chicken Breasts by Acidified Coating Containing Allyl Isothiocyanate or Deodorized Oriental Mustard Extract. Food Microbiol. 2016, 57, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, K.; Friedrich, L.; Kisko, G.; Ayari, E.; Nemeth, C.; Dalmadi, I. Use of allyl-Isothiocyanate and carvacrol to preserve fresh chicken meat during chilling storage. Czech J. Food Sci. 2019, 37, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacon, P. A.; Muthukumarasamy, P.; Holley, R. A. Elimination of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from Fermented Dry Sausages at an Organoleptically Acceptable Level of Microencapsulated Allyl Isothiocyanate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 3096–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H. E.; Sheen, S. Effect of High-Pressure Processing Allyl Isothiocyanate, and Acetic Acid Stresses on Salmonella Survivals, Storage, and Appearance Color in Raw Ground Chicken Meat. Food Control 2021, 123, 1007784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, A.; Valenti, D.; Giarratana, F.; Ziino, G.; Panebianco, A. A new approach to modelling the shelf-life of Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barea-Ramos, J.D.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Calvo, P.; Meléndez, F.; Lozano, J.; Martín-Vertedor, D. Inhibition of Botrytis cinerea in tomatoes by allyl-isothiocyanate release from black mustard (Brassica nigra) seeds and detection by E-nose. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L. F.; Bordin, K.; de Lara, G. H. C.; Saladino, F.; Quiles, J. M.; Meca, G.; Luciano, F. B. Fumigation of Brazil nuts with allyl isothiocyanate to inhibit the growth of Aspergillus parasiticus and aflatoxin production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladino, F.; Quiles, J. M.; Luciano F., B.; Manes, J.; Fernández-Franzón, M.; Meca, G. Shelf life improvement of the loaf bread using allyl, phenyl and benzyl isothiocyanates against Aspergillus parasiticus. LWT - Food Sci Technol 2017, 78, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J-H.; Sun, D-W.; Zeng, X-A.; Liu, D. Recent advances in methods and techniques for freshness quality determination and evaluation of fish and fish fillets: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci.Nutr. 2015, 55, 1012-1225.

- Olafsdottir, G.; Nesvadba, P.; Di Natale, C.; Careche, M.; Oehlenschläger, J.; Tryggvadóttir, S.; Schubring, R.; Kroeger, M.; Heia, K.; Esaiassen, M.; Macagnano, A.; Jorgensen, B.M. Multisensor for fish quality determination. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walayat, N.; Liu, J.; Nawaz, A.; Aadil, R.M.; López-Pedrouso, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Role of food hydrocolloids as antioxidants along with modern processing techniques on the surimi protein gel textural properties, developments, limitation and future perspectives. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Walayat, N.; Ding, Y.; Liu, J. The role of trifunctional cryoprotectans in the frozen storage of aquatic foods: Recent developments and future recommendations. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.X.; Chong, Y.Q.; Ding, Y.T.; Gu, S.Q.; Liu, L. Determination of the effects of different washing processes on aroma characteristics in silver carp mince by MMSE-GC-MS, e-nose and sensory evaluation. Food Chem. 2016, 207, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Qian, Y.L.; Magana, A.A.; Xiong, S.; Quian, M.C. Comparative characterization of aroma compounds in silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix), pacific whiting (Merluccius productus), and Alaska pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) surimi by aroma extract dilution analysis, odor activity value, and aroma recombination studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 10403–10413. [Google Scholar]

- Varlet, V.; Knockaert, C.; Prost, C.; Serot, T. Comparison of odor-active volatile compounds of fresh and smoked salmon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3391–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivekanandan-Giri, A.; Byun, J.; Pennathur, S. Quantitative analysis of amino acid oxidation markers by tandem mass spectrometry. Methods in Enzymology 2011, 491, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Analysis of key volatile compounds and quality properties of tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) fillets during cold storage: based on thermal desorption coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (TD-GC-MS). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 184, 115051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros-Castillo, J.C.; Calderón-Santoyo, M.; Cuevas-Glory, L.F.; Calderón-Chiu, C.; Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A. Contribution of glycosidically bound compounds to aroma potential of jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus lam). Flavour and Fragrance Journal 2023, 38, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, R.; Gui, M.; Jiang, Z.; Li, P. Identification of the specific spoilage organism in farmed sturgeon (Acipenser baerii) fillets and its associated quality and flavour change during ice storage. Foods 2021, 10, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L-m.; Wu, W.; Tao, N-p.; Li, Y-q.; Wu, N.; Qin, X. Characterization of important odorants in four steamed Coilia ectenes from China by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-olfactometry. Fish Sci. 2015, 81, 947-957.

- Li, Y.; Yuan, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, M.; Gao, R. Analysis of the changes of volatile flavor compounds in a traditional Chinese shrimp paste during fermentation based on electronic nose, SPME-GC-MS and HS-GC-IMS. FSHW 2023, 12, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Luo, L.; Chen, G. Study on seafood volatile profile characteristics during storage and its potential use for freshness evaluation by headspace solid phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 659, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.N.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Laghari, Z.A.; Nie, P. Molecular and functional characterization of zinc finger aspartate-histidine-cysteine (DHHC)-type containing 1, ZDHHC1 in Chinese perch Siniperca chuatsi. Fish & Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 130, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Cengiz, N.; Guclu, G.; Kelebek, H.; Mazi, H.; Selli, S. Characterization of volatile compounds in the water samples from rainbow trout aquaculture ponds eliciting off-odors: understanding locational and seasonal effects. Environ. Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Ren, X.; Li, Y.; Mao, L. The beneficial effects of grape seed, sage and oregano extracts on the quality and volatile flavor component of hairtail fish balls during cold storage at 4 ºC. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2019, 101, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, P.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, R.; Feng, X.; Kan, J. Deodorizing effects of rosemary extract on silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and determination of its deodorizing components. J. Food Sci. 2021, 87, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mi, S.; Liu, R. B.; Sang, Y. X.; Wang, X. H. Evaluation of volatile compounds during the fermentation process of yogurts by Streptococcus thermophilus based on odor activity value and heat map analysis. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Gong, G.; Li, N.; Gao, P.; Hou, T.; Zhu, J.; Abulikemu, B. Mechanism of flavor changes in Northern Pike (Esox lucius) during refrigeration revealed by UHPLC-MS metabolomics and GC-IMS. Food Biosci. 2025, 60, 106557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Benjakul, S.; Sanmartin, C.; Ying, X.; Ma, L.; Xiao, G.; Yu, J.; Liu, G.; Deng, S. Changes of volatile flavor compounds in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) during storage, as evaluated by headspace gas chromatography-Ion mobility spectrometry and principal component analysis. Foods 2021, 10, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Fresh fish | Rotten fish | River | |||||||||

| Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 12 | Day 18 | Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 12 | Day 18 | Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 12 | Day 18 | |

| C | 7.4 ± 1.1A | 6.6 ± 0.9aAB | 6.1 ± 1.7aB | 1.6 ± 1.1bC | nd | nd | nd | 3.8 ± 1.7a | 6.2 ± 0.8A | 5.0 ± 2.9aAB | 5.5 ± 1.7aAB | 3.5 ± 2.1aB |

| T1 | 6.9 ± 1.0aA | 5.1 ± 1.5abB | 1.2 ± 0.7bC | nd | nd | 2.5 ± 1.4a | 4.8 ± 2.0aA | 4.4 ± 1.4abA | 2.7 ± 1.9aA | |||

| T2 | 6.7 ± 1.1aA | 3.6 ± 0.9bB | 2.9 ± 1.2bB | nd | nd | 2.5 ± 1.5a | 4.9 ± 1.9ªA | 3.1 ± 1.6bA | 3.3 ± 1.1aA | |||

| T3 | 6.6 ± 1.5aA | 3.8 ± 1.4bB | 2.8 ± 1.4aB | nd | nd | 2.1 ± 1.3a | 4.6 ± 1.2aA | 3.1 ± 1.5bA | 2.7 ± 1.3aA | |||

| Treatments | Sulphur | Ammonia | Pungent | |||||||||

| Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 12 | Day 18 | Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 12 | Day 18 | Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 12 | Day 18 | |

| C | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.3 ± 0.9 | nd | nd | nd | 1.4 ± 1.0a |

| T1 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.0 ± 0.5a | |||

| T2 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.1 ± 0.8a | |||

| T3 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.2 ± 1.0a | |||

| LRI | VOCs | Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 12 | Day 18 | |||||||||

| C | C | T1 | T2 | T3 | C | T1 | T2 | T3 | C | T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| Hydrocarbons | ||||||||||||||

| 731.0 | Hexane, 3-methyl- | 73.2 | 238.2 | 147.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 890.5 | Hexane, 2,4-dimethyl- | 1.1 | 1.0 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 957.7 | 1,3-cyclohexadiene | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.3 | nd | nd | nd |

| 967.1 | 3,5,5-trimethyl-1-hexene | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.4 | nd | nd | nd |

| TOTAL | 74.3 | 239.2 | 147.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 3.7 | nd | nd | nd | |

| Alcohols | ||||||||||||||

| 748.1 | 3-methyl-1-butanol | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 11.9 | nd |

| 862.9 | 1-hexanol | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 972.8 | 1-octen-3-ol | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.9 | nd | 0.9 | nd |

| 1022 | 2-ethyl-1-hexanol | 7.7 | 26.6 | 23.2 | 7.5 | nd | 38.0 | 30.3 | 22.4 | 13.9 | 33.0 | 26.0 | 23.4 | nd |

| 1626 | 2,6-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-(1- oxopropyl) phenol |

65.0 | 21.5 | 9.4 | nd | nd | 15.1 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 14.4 | 10.4 | 5.3 | nd |

| TOTAL | 72.7 | 48.1 | 32.6 | 7.5 | nd | 53.0 | 40.3 | 31.9 | 21.9 | 115.7 | 37.4 | 47.1 | nd | |

| Benzenoids | ||||||||||||||

| 765 | Toluene | 6.0 | 7.6 | 5.0 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 848 | Ethylbenzene | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.5 | nd | nd | nd | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 857 | Benzene, 1,3-dimethyl | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.4 | 7.8 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 4.8 | nd |

| 863 | o-xylene | 6.3 | nd | 6.3 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 880 | p-xylene | 2.5 | 2.8 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 950 | Benzene-1-ethyl-4-methyl | 2.7 | 3.5 | 3.0 | nd | nd | nd | 2.5 | 1.9 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 980 | Benzene, 1,2,3-trimethyl- | 3.5 | 4.4 | 6.5 | nd | nd | nd | 6.5 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 4.1 | nd | nd | 1.6 |

| 1279 | Butylated hydroxytoluene | 4.2 | 6.7 | nd | nd | nd | 40.7 | 31.7 | 28.9 | 26.6 | 152.2 | 103.2 | 64.0 | 47.4 |

| 1361 | Benzene, hexamethyl | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 7.7 | 4.0 | nd |

| 1300 | Indole | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 10.7 |

| TOTAL | 28.6 | 27.5 | 23.4 | nd | nd | 42.1 | 50.3 | 39.4 | 37.0 | 162.0 | 116.8 | 72.8 | 47.4 | |

| LRI | VOCs | Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 9 | Day 18 | |||||||||

| C | C | T1 | T2 | T3 | C | T1 | T2 | T3 | C | T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| Isothiocyanate | ||||||||||||||

| 873 | Allyl isothiocyanate | nd | nd | 19.4 | 16.3 | 24.5 | nd | 6.0 | 9.9 | 13.9 | nd | 2.3 | 4.5 | 5.4 |

| 922 | 1-Isothiocyanatobutane | nd | nd | 5.8 | 3.4 | 4.3 | nd | 5.2 | 13.2 | 10.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| TOTAL | nd | nd | 25.2 | 19.7 | 28.9 | nd | 11.2 | 23.1 | 24.1 | nd | 2.3 | 4.5 | nd | |

| Ketones | ||||||||||||||

| 882 | 2-heptanone | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 18.8 | 10.4 | 5.5 | 5.9 |

| 1082 | 2-dodecanone | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 18.2 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 44.9 | 35.1 | 10.3 | 8.6 |

| TOTAL | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 18.2 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 63.7 | 45.5 | 15.7 | 14.6 | |

| Acetates | ||||||||||||||

| 742 | Acetic acid | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 188.3 | 193.3 | nd |

| 1072 | 4-hexen-1-ol, acetate | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 12.4 | nd | nd |

| 1266 | 11-tetradecen-1-ol, acetate | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 77.2 | nd | nd |

| TOTAL | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 277.8 | 193.3 | nd | |

| Aldehydes | ||||||||||||||

| 1094 | Nonanal | 10.9 | 3.0 | 6.3 | nd | 4.3 | 2.4 | 7.2 | 6.3 | 6.9 | nd | 8.1 | 8.0 | 9.1 |

| 1118 | 2,5-bis[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]benzaldehyde | 9.8 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 5.0 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 10.3 | 9.7 | 6.2 |

| TOTAL | 20.7 | 9.4 | 15.0 | 7.0 | 13.0 | 7.4 | 12.9 | 11.8 | 15.6 | 7.7 | 18.4 | 17.7 | nd | |

| Others | ||||||||||||||

| 954 | Dimethyl trisulfide | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 5.6 | nd | nd | nd |

| 871 | Butanoic acid, 3-methyl- | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 17.2 | nd | nd | nd |

| 1017 | D-limonene | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.2 | nd | nd | 2.2 | 1.6 | nd | nd | nd | 2.6 |

| TOTAL | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.5 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.2 | 1.6 | 22.9 | nd | nd | 2.6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).