Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

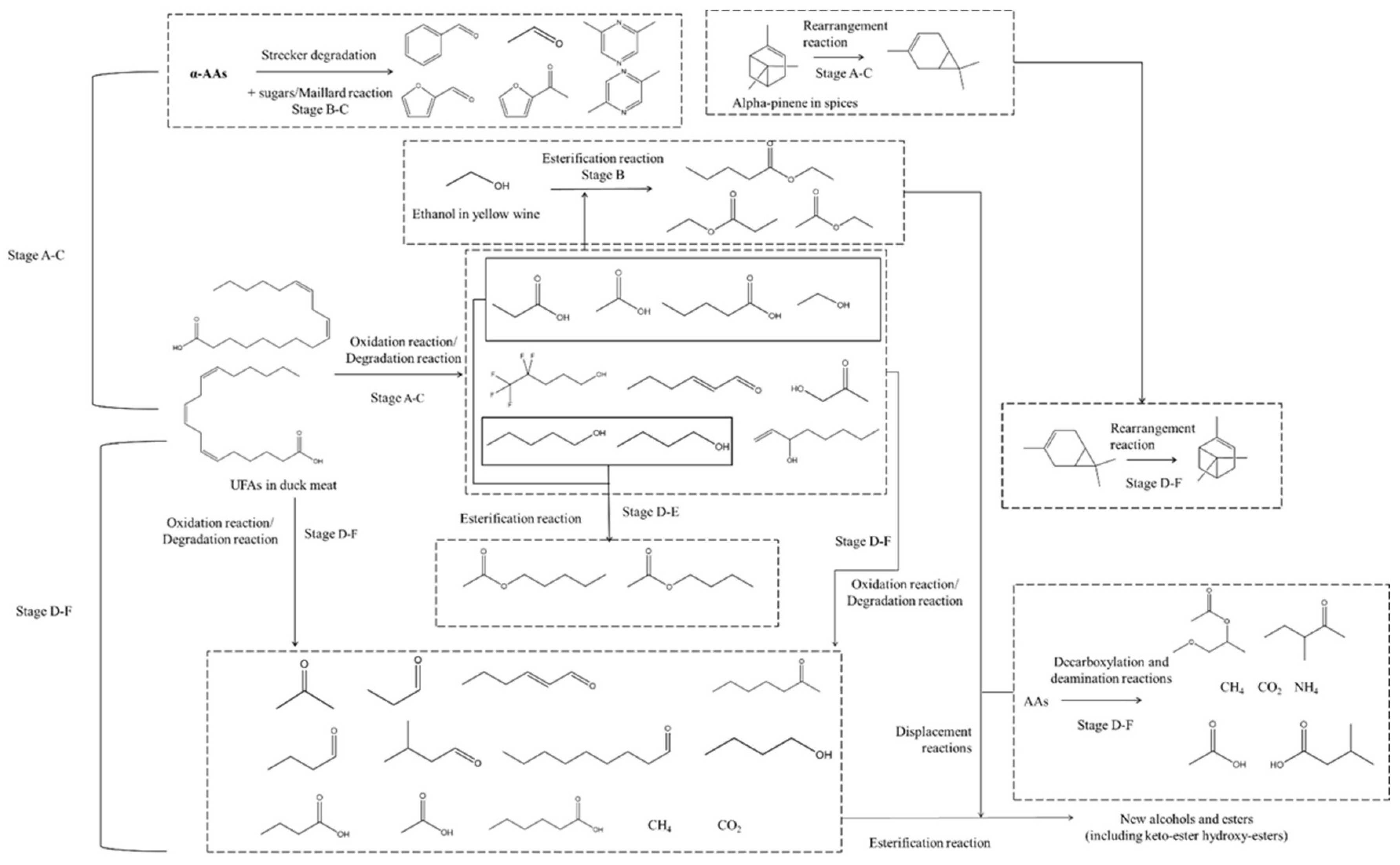

This study revealed the physicochemical, microbial, flavor and sensory changes in sauced duck from the marinating phase to the end of storage, divided into six stages (stages A-F). The changes in color, total plate count, total volatile basic nitrogen, and thiobarbituric acid reactive substance at different stages were clarified. We utilized 16S rRNA gene sequencing, GC-IMS, and GC-MS to explore the changes in bacterial flora, fatty acid composition, and flavor characters. The dominant bacteria identified in stages A-C included Psychrobacter, Flavobacterium, and Pseudomonas, while Lactobacillus and Staphylococcus dominated during stages D-F. Aldehydes, esters, alcohols, and ketones emerged as the main flavor compounds. Several unsaturated fatty acids significantly (P< 0.05) decreased from stage A to stage F. The sensory quality of sauced duck improved. The potential reactions and correlation analysis of sauced duck samples across different stages were performed. 3-Methy-1-butanol could be a crucial indicator of sauced duck’s overall quality. This research could support reference for the treatment optimization of sauced duck products.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Sauced Duck Preparation

2.3. Experimental Group Design

2.4. Determination of Edible Indexes

2.5. Fatty Acid Analysis

2.6. Sensory Evaluation

2.7. Microbial Community Analysis

2.8. Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical and Physical Changes of Samples Across Different Stages Were Analyzed

3.2. The Microbial Biomarkers of Samples Were Identified at Different Stages

3.3. The Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis of Flavor Compounds of Samples at Different Were Performed

3.4. The Biomarker 3-Carene Were Clarified Through Correlation Analysis

3.5. The Potential Chemical Reactions Were Predicted Based on the Previous Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| AA | amino acid |

| ANOSIM | analysis of similarities |

| CTAB/SDS | cetyltrimethylammonium bromide/sodium docecyl sulfate-based |

| DT | drift time |

| FA | free fatty acid |

| GC-IMS | gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry |

| GC-MS | gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| HCl | hydrochloric acid |

| LDA | linear discriminant analysis |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MgO | magnesium oxide |

| MRPP | multi-response permutation procedure |

| MUFA | mono-unsaturated fatty acid |

| MW | molecular weight |

| NaCl | sodium chloride |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| PCoA | principal coordinate analysis |

| PUFA | poly-unsaturated fatty acid |

| RI | retention index |

| RIP rel | normalization treatment |

| RT | retention time |

| SFA | saturated fatty acid |

| Stage A | samples collected after marinating and before cooking |

| Stage B | samples collected after cooking and before drying |

| Stage C | samples collected after drying and before storage |

| Stage D | samples stored after 5 d |

| Stage E | samples stored after 10 d |

| Stage F | samples stored after 15 d |

| TBARS | thiobarbituric acid reactive substance |

| TPC | total plate count |

| T-VBN | total volatile basic nitrogen |

| UPGMA | unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean |

| UFA | unsaturated fatty acid |

References

- Álvarez, M.; Andrade, M.J.; García, C.; Rondán, J.J.; Núñez, F. Effects of preservative agents on quality attributes of dry-cured fermented sausages. Foods 2020, 9, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, M.S.; Kwon, J.H.; Ahmad, R.S.; Ameer, K.; Ahmad, S.; Jo, Y. Influence of E-beam irradiation on microbiological and physicochemical properties and fatty acid profile of frozen duck meat. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassey, A.P.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Odeyemi, O.A.; Frimpong, E.B.; Ye, K.; Li, C.; Zhou, G. Assessment of quality characteristics and bacterial community of modified atmosphere packaged chilled pork loins using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing analysis. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y. A possible systematic culinary approach for spent duck meat: Sous-vide cuisine and its optimal cooking condition. Poultry Sci. 2023, 102, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, M.; Xu, L.; Gu, T.; Sun, Y.; Xia, Q.; He, J.; Pan, D.; Lu, L. Investigation into the characteristic volatile flavor of old duck. Food Chem. X 2023, 20, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. . UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wu, Z.; Xia, Q.; Pan, D. Mechanisms of inhibition of prevailing spoilage bacteria Weissella viridescens in sauced duck product by e-beam irradiation synergistic modified atmosphere packaging. Food Control 2024, 159, 110261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeraerts, W.; Pothakos, V.; De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. Diversity of the dominant bacterial species on sliced cooked pork products at expiration date in the Belgian retail. Food Microbiol. 2017, 65, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeraerts, W.; De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. Mapping the dominant microbial species diversity at expiration date of raw meat and processed meats from equine origin, an underexplored meat ecosystem, in the Belgian retail. Int. J. of Food Microbiol. 2019, 289, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ali, S.; Abid, M.; Cao, J.; Jabbar, S.; Tume, R.K.; Zhou, G. Improved duck meat quality by application of high pressure and heat: A study of water mobility and compartmentalization, protein denaturation and textural properties. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, C.; He, J.; Wu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Pan, D.; Tian, H.; Xia, Q. Combining e-beam irradiation and modified atmosphere packaging as a preservation strategy to improve physicochemical and microbiological properties of sauced duck product. Food Control 2022, 136, 108889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, W.; Ren, D. The safety evaluation of chilled pork from online platform in China. Food Control. 2019, 96, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Kong, F.; Xing, S.; He, Z.; Bai, L.; Sun, J.; Tan, X.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, G.; Wen, J. (). Dominant changes in the breast muscle lipid profiles of broiler chickens with wooden breast syndrome revealed by lipidomics analyses. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechno. 2022, 13, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Yang, H.; Li, N.; Lu, L.; Yang, C.; Jin, P.; Xiao, Y. Molecular characterization, developmental expression, and modulation of occludin by early intervention with Clostridium butyricum in Muscovy ducks. Poultry Sci. 2021, 100, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Lyu, W.; Zeng, T.; Wang, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G.; Lu, L.; Yang, H.; Xiao, Y. . Duck gut metagenome reveals the microbiome signatures linked to intestinal regional, temporal development, and rearing condition. iMeta 2024, e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, E.; Dzieciol, M.; Pinior, B.; Neubauer, V.; Metzler-Zebeli, B.U.; Wagner, M.; Schmitz-Esser, S. High diversity of viable bacteria isolated from lymph nodes of slaughter pigs and its possible impacts for food safety. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 1420–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Xia, C.; Zeng, T.; Xia, Q.; Zhou, C.; Cao, J.; He, J.; Pan, D.; Wang, D. The joint effects of ultrasound and modified atmosphere packaging on the storage of sauced ducks. LWT 2023, 177, 114561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Bergman, N.H.; Phillippy, A.M. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a Web browser. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasinska, E.; Rutkowska, J.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Tambor, K. Effects of cooking methods on changes in fatty acids contents, lipid oxidation and volatile compounds of rabbit meat. LWT 2019, 110, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, M.; Sahu, P.P. Meat quality assessment using Au patch electrode Ag-SnO2/SiO2/Si MIS capacitive gas sensor at room temperature. Food Chem. 2020, 324, 126893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, X.; and Huang, A. A metabolomics-based approach investigates volatile flavor formation and characteristic compounds of the Dahe black pig dry-cured ham. Meat Sci. 2019, 15, 107904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; He, Y.; Cheng, S.; He, J.; Pan, D.; Cao, J.; Sun, Y. Free fatty acids responsible for characteristic aroma in various sauced-ducks. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; He, J.; Duan, M.; Chang, Y.; Gu, T.; Tian, Y.; Cai, Z.; Zeng, T.; Lu, L. Effects of lactic acid bacteria-derived fermented feed on the taste and quality of duck meat. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Luan, D.; Sun, J.; Huang, M.; Wang, B.; Zheng, Y. Quality changes of duck meat during thermal sterilization processing caused by microwave, stepwise retort, and general retort heating. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1016942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Cui, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, P.; Pu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, B. Analysis of the volatile compounds in Fuliji roast chicken during processing and storage based on GC-IMS. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Lin, W.; Sun, Y.; Pan, D.; Xia, Q.; Zhou, C.; He, J. Relationship between flavor characteristics and lipid oxidation in air-dried beef at different roasting stages. Int. J. Gastron. Food S. 2024, 37, 100988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yang, C.; Song, Y.; Qiang, Y.; Han, D.; Zhang, C. Changes provoked by altitudes and cooking methods in physicochemical properties, volatile profile, and sensory characteristics of yak meat. Food Chem. X. 2023, 20, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | Stage | |||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| L* | 32.1 ± 0.3a | 48.2 ± 0.8f | 46.5 ± 0.3e | 44.3 ± 0.2d | 42.5 ± 0.1c | 41.3 ± 0.1b |

| a* | 8.2 ± 0.9a | 10.5 ± 0.3b | 11.2 ± 0.6c | 11.5 ± 0.1c | 12.6 ± 0.5d | 12.1 ± 0.3d |

| b* | 5.8 ± 0.6a | 6.0 ± 1.2b | 7.0 ± 0.4c | 7.8 ± 0.6d | 8.1 ± 0.3d | 8.2 ± 0.3d |

| T-VBN (mg/ 100 g) | 5.92 ± 0.42a | 6.85 ± 0.25b | 7.12 ± 0.92b | 20.25 ± 0.89c | 24.58 ± 0.43d | 48.20 ± 1.06e |

| TBARS (mg/ kg) | 0.16 ± 0.00a | 0.27 ± 0.03b | 0.58 ± 0.05c | 0.96 ± 0.08d | 1.37 ± 0.02e | 2.13 ± 0.15f |

| TPC (log10 CFU /g) | 1.82 ± 0.02a | 2.24 ± 0.06b | 2.20 ± 0.05b | 6.85 ± 0.01c | 7.82 ± 0.12d | 8.45 ± 0.08e |

| No. | Compound | CAS# | Formula | MW | RI | Rt (s) |

Dt (RIP rel) |

Comment |

Description |

| Aldehydes (n = 19) | |||||||||

| 1 | Benzaldehyde | C100527 | C7H6O | 106.1 | 1553.6 | 1406.451 | 1.157 | Bitter Almond, Brunt sugar, Cherry, Malt, Roasted Pepper | |

| 2 | Nonanal | C124196 | C9H18O | 142.2 | 1406.4 | 1023.341 | 1.48016 | Fat, Floral, Green, Lemon | |

| 3 | (E)-2-Heptenal | C18829555 | C7H12O | 112.2 | 1334.5 | 876.019 | 1.26147 | Monomer | Almond, Fat, Fruit |

| 1334.9 | 876.877 | 1.67092 | Dimer | ||||||

| 4 | (E)-2-Hexenal | C6728263 | C6H10O | 98.1 | 1234.5 | 711.029 | 1.18832 | Monomer | \ |

| 1235.1 | 712.002 | 1.51718 | Dimer | ||||||

| 5 | Heptanal | C111717 | C7H14O | 114.2 | 1199.8 | 662.503 | 1.33641 | Monomer | Citrus, Fat, Green, Nut |

| 1199.8 | 662.503 | 1.69504 | Dimer | ||||||

| 6 | (E)-2-Pentenal | C1576870 | C5H8O | 84.1 | 1152.5 | 569.553 | 1.10533 | Monomer | \ |

| 1152.7 | 570.014 | 1.3599 | Dimer | ||||||

| 7 | Hexanal | C66251 | C6H12O | 100.2 | 1103.8 | 482.051 | 1.27572 | Monomer | Apple, Fat, Fresh, Green, Oil |

| 1104.2 | 482.69 | 1.56344 | Dimer | ||||||

| 8 | Pentanal | C110623 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 1004.9 | 361.067 | 1.42311 | Almond, Bitter, Malt, Oil, Pungent | |

| 9 | 3-Methylbutanal | C590863 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 931.3 | 305.536 | 1.4039 | \ | |

| 10 | Acetal | C105577 | C6H14O2 | 118.2 | 910.8 | 292.146 | 1.02663 | Creamy, Fruit, Pleasant, Tropical Fruit | |

| 11 | Butanal | C123728 | C4H8O | 72.1 | 889.9 | 279.149 | 1.11717 | Banana, Green, Pungent | |

| 12 | 2-Methylpropanal | C78842 | C4H8O | 72.1 | 830.7 | 245.279 | 1.2818 | Burnt, Caramel, Cocoa, Green, Malt | |

| 13 | Propanal | C123386 | C3H6O | 58.1 | 821.0 | 240.159 | 1.14324 | Floral, Pungent, Solvent | |

| 14 | Acetaldehyde | C75070 | C2H4O | 44.1 | 763.5 | 211.803 | 0.97998 | Floral, Green Apple | |

| 15 | 2-Propenal | C107028 | C3H4O | 56.1 | 868.1 | 266.153 | 1.05955 | \ | |

| 16 | Methional | C3268493 | C4H8OS | 104.2 | 1477.2 | 1192.512 | 1.0955 | Cooked potato, Soy | |

| 17 | 3-Methyl-2-butenal | C107868 | C5H8O | 84.1 | 1216.3 | 685.268 | 1.09732 | Almond, Roasted | |

| 18 | 2-Methyl-2-pentenal | C623369 | C6H10O | 98.1 | 1200.1 | 663.004 | 1.5201 | Fruit | |

| 19 | Octanal | C124130 | C8H16O | 128.2 | 1304.0 | 820.167 | 1.40635 | Citrus, Fat, Green, Oil, Pungent | |

| Esters (n = 19) | |||||||||

| 1 | Methyl octanoate | C111115 | C9H18O2 | 158.2 | 1449.1 | 1122.052 | 1.42791 | Fruit, Orange, Wax, Wine | |

| 2 | (E)-2-Octenal | C2548870 | C8H14O | 126.2 | 1441.5 | 1103.868 | 1.33835 | Dandelion, Fat, Fruit, Grass, Green, Spice | |

| 3 | Hexyl propionate | C2445763 | C9H18O2 | 158.2 | 1343.7 | 893.679 | 1.41894 | Fruit | |

| 4 | 1-Penten-3-ol | C616251 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 1178.8 | 623.205 | 0.94299 | Butter, Fish, Green, Oxidized, Wet Earth | |

| 5 | Methyl 2-methylbutanoate | C868575 | C6H12O2 | 116.2 | 1016.1 | 372.882 | 1.18714 | Apple, Fruit, Green Apple, Strawberry | |

| 6 | Ethyl acetate | C141786 | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 898.2 | 284.269 | 1.33393 | Aromatic, Brandy, Grape | |

| 7 | Methyl acetate | C79209 | C3H6O2 | 74.1 | 852.9 | 257.488 | 1.19263 | Ester, Green | |

| 8 | Ethyl propanoate | C105373 | C5H10O2 | 102.1 | 976.8 | 337.437 | 1.45329 | Apple, Pineapple, Rum, Strawberry | |

| 9 | Ethyl isobutyrate | C97621 | C6H12O2 | 116.2 | 984.2 | 342.951 | 1.55756 | \ | |

| 10 | Propyl acetate | C109604 | C5H10O2 | 102.1 | 997.3 | 353.19 | 1.47936 | Celery, Floral, Pear, Red Fruit | |

| 11 | Ethyl 3-methylbutanoate | C108645 | C7H14O2 | 130.2 | 1084.0 | 453.619 | 1.27631 | Apple, Fruit, Pineapple, Sour | |

| 12 | Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | C7452791 | C7H14O2 | 130.2 | 1071.1 | 437.077 | 1.25299 | Apple, Ester, Green Apple, Kiwi, Strawberry | |

| 13 | Isoamyl acetate | C123922 | C7H14O2 | 130.2 | 1139.7 | 545.17 | 1.30207 | Monomer | Apple, Banana, Pear |

| 1139.7 | 545.17 | 1.74786 | Dimer | ||||||

| 14 | Ethyl butanoate | C105544 | C6H12O2 | 116.2 | 1056.6 | 419.151 | 1.55878 | Apple, Butter, Cheese, Pineapple, Strawberry | |

| 15 | Butyl acetate | C123864 | C6H12O2 | 116.2 | 1091.1 | 462.925 | 1.2589 | Monomer | Apple, Banana |

| 16 | 1-Methoxy-2-propyl acetate | C108656 | C6H12O3 | 132.2 | 1242.7 | 723.096 | 1.14241 | \ | |

| 17 | Pentyl acetate | C628637 | C7H14O2 | 130.2 | 1187.5 | 642.203 | 1.31303 | Apple, Banana, Pear | |

| 18 | Ethyl hexanoate | C123660 | C8H16O2 | 144.2 | 1248.3 | 731.416 | 1.34219 | Apple Peel, Brandy, Fruit Gum, Overripe Fruit, Pineapple | |

| 19 | Ethyl pentanoate | C539822 | C7H14O2 | 130.2 | 1180.5 | 626.931 | 1.68337 | Apple, Dry Fish, Herb, Nut, Yeast | |

| Alcohols (n = 13) | |||||||||

| 1 | 1-Octen-3-ol | C3391864 | C8H16O | 128.2 | 1488.6 | 1222.062 | 1.16669 | Cucumber, Earth, Fat, Floral, Mushroom | |

| 2 | 1-Hexanol | C111273 | C6H14O | 102.2 | 1373.6 | 953.204 | 1.33238 | Monomer | Banana, Flower, Grass, Herb |

| 1373.6 | 953.204 | 1.63689 | Dimer | ||||||

| 3 | 1-Heptanol | C111706 | C7H16O | 116.2 | 1489.1 | 1223.36 | 1.40403 | \ | |

| 4 | Acetoin | C513860 | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 1302.7 | 817.787 | 1.06521 | Monomer | Butter, Creamy, Green Pepper |

| 1303.2 | 818.758 | 1.33106 | Dimer | ||||||

| 5 | 1-Pentanol | C71410 | C5H12O | 88.1 | 1267.5 | 760.526 | 1.25791 | Monomer | Balsamic, Fruit, Green, Pungent, Yeast |

| 1268.1 | 761.497 | 1.51126 | Dimer | ||||||

| 6 | 3-Methyl-1-butanol | C123513 | C5H12O | 88.1 | 1223.6 | 695.501 | 1.24185 | Monomer | Burnt, Cocoa, Floral, Malt |

| 1224.3 | 696.471 | 1.49164 | Dimer | ||||||

| 7 | 1-Butanol | C71363 | C4H10O | 74.1 | 1163.7 | 591.908 | 1.18249 | Monomer | Fruit |

| 1163.7 | 591.908 | 1.37859 | Dimer | ||||||

| 8 | 2-Methyl-1-propanol | C78831 | C4H10O | 74.1 | 1113.0 | 497.38 | 1.17445 | Monomer | Apple, Bitter, Cocoa, Wine |

| 1113.3 | 498.019 | 1.37055 | Dimer | ||||||

| 9 | 1-Propanol | C71238 | C3H8O | 60.1 | 1058.7 | 421.718 | 1.11306 | Monomer | Alcohol, Candy, Pungent |

| 1058.7 | 421.718 | 1.25436 | Dimer | ||||||

| 10 | 2-Butanol | C78922 | C4H10O | 74.1 | 1042.2 | 402.026 | 1.14873 | Monomer | \ |

| 1042.5 | 402.42 | 1.32433 | Dimer | ||||||

| 11 | Ethanol | C64175 | C2H6O | 46.1 | 944.7 | 314.594 | 1.04172 | Monomer | \ |

| 945.8 | 315.382 | 1.12678 | Dimer | ||||||

| 12 | 2-Propanol | C67630 | C3H8O | 60.1 | 934.8 | 307.899 | 1.09111 | Floral | |

| 13 | cis-2-Penten-1-ol | C1576950 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 1341.3 | 889.042 | 0.94555 | \ | |

| Ketones (n = 11) | |||||||||

| 1 | 1-Hydroxy-2-propanone | C116096 | C3H6O2 | 74.1 | 1317.8 | 844.962 | 1.05629 | Monomer | Butter, Herb, Malt, Pungent |

| 1317.8 | 844.962 | 1.05629 | Dimer | ||||||

| 2 | 2-Heptanone | C110430 | C7H14O | 114.2 | 1195.4 | 656.68 | 1.26504 | Blue Cheese, Fruit, Green, Nut, Spice | |

| 3 | 4-Methyl-3-penten-2-one | C141797 | C6H10O | 98.1 | 1147.5 | 559.973 | 1.12301 | \ | |

| 4 | 1-Penten-3-one | C1629589 | C5H8O | 84.1 | 1034.3 | 392.968 | 1.09385 | Fish, Green, Mustard, Pungent | |

| 5 | 4-Methyl-2-pentanone | C108101 | C6H12O | 100.2 | 1029.4 | 387.454 | 1.48622 | \ | |

| 6 | 2-Pentanone | C107879 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 1003.4 | 359.492 | 1.35177 | Fruit, Pungent | |

| 7 | 2-Butanone | C78933 | C4H8O | 72.1 | 918.7 | 297.266 | 1.24339 | Fragrant, Fruit, Pleasant | |

| 8 | Acetone | C67641 | C3H6O | 58.1 | 838.7 | 249.612 | 1.11443 | Pungent | |

| 9 | 3-Methyl-2-pentanone | C565617 | C6H12O | 100.2 | 1040.2 | 399.732 | 1.47772 | \ | |

| 10 | Cyclopentanone | C120923 | C5H8O | 84.1 | 1202.5 | 666.24 | 1.1045 | Mint, Cool | |

| 11 | Dihydro-2(3H)-furanone | C96480 | C4H6O2 | 86.1 | 1711.3 | 1977.29 | 1.08782 | Caramel, Cheese, Roasted Nut | |

| Acids (n = 4) | |||||||||

| 1 | Propanoic acid | C79094 | C3H6O2 | 74.1 | 1638.6 | 1689.857 | 1.11514 | Fat, Fruit, Pungent, Silage, Soy | |

| 2 | Butanoic acid | C107926 | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 1705.5 | 1952.665 | 1.16147 | Butter, Cheese, Sour | |

| 3 | Acetic acid | C64197 | C2H4O2 | 60.1 | 1505.5 | 1267.521 | 1.05921 | Monomer | Acid, Fruit, Pungent, Sour, Vinegar |

| 1505.9 | 1268.819 | 1.15624 | Dimer | ||||||

| 4 | 2-Methylpropanoic acid | C79312 | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 1635.5 | 1678.655 | 1.15151 | Burnt, Butter, Cheese, Sweat | |

| Others (n = 18) | |||||||||

| 1 | 2,6-Dimethylpyrazine | C108509 | C6H8N2 | 108.1 | 1362.7 | 931.124 | 1.14579 | Cocoa, Coffee, Green, Roast Beef, Roasted Nut | |

| 2 | Ammonia | C7664417 | H3N | 17.0 | 1273.1 | 769.261 | 0.84576 | Dimer | \ |

| 1273.7 | 770.231 | 0.90642 | Monomer | ||||||

| 3 | Methylpyrazine | C109080 | C5H6N2 | 94.1 | 1279.9 | 779.937 | 1.09376 | Cocoa, Green, Hazelnut, Popcorn, Roasted | |

| 4 | 2-Pentylfuran | C3777693 | C9H14O | 138.2 | 1247.0 | 729.469 | 1.2472 | Butter, Floral, Fruit, Green Bean | |

| 5 | o-Xylene | C95476 | C8H10 | 106.2 | 1194.0 | 654.739 | 1.08127 | \ | |

| 6 | 3-Carene | C13466789 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1149.5 | 563.805 | 1.20821 | Lemon | |

| 7 | Dimethyl disulfide | C624920 | C2H6S2 | 94.2 | 1072.1 | 438.259 | 1.13775 | Cabbage, Garlic, Onion | |

| 8 | alpha-Pinene | C80568 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1029.4 | 387.454 | 1.23104 | Cedarwood, Pine, Sharp | |

| 9 | Dimethyl sulfide | C75183 | C2H6S | 62.1 | 795.5 | 227.163 | 0.95529 | Cabbage, Organic, Sulfur, Wet Earth | |

| 10 | Ethylbenzene | C100414 | C8H10 | 106.2 | 1135.4 | 537.092 | 1.09147 | \ | |

| 11 | Unidentified 1 | \ | \ | 0 | 1119.6 | 508.818 | 1.09608 | \ | |

| 12 | Unidentified 2 | \ | \ | 0 | 1148.5 | 561.814 | 1.32483 | \ | |

| 13 | Furfural | C98011 | C5H4O2 | 96.1 | 1500.0 | 1252.624 | 1.09377 | Almond, Baked Potatoes, Bread, Burnt, Spice | |

| 14 | Dipropyl disulfide | C629196 | C6H14S2 | 150.3 | 1421.2 | 1056.408 | 1.26895 | Cooked Meat, Garlic, Onion, Pungent, Sulfur | |

| 15 | 3-Ethylpyridine | C536787 | C7H9N | 107.2 | 1388.7 | 984.954 | 1.09723 | Nuts | |

| 16 | 2,5-Dimethylpyrazine | C123320 | C6H8N2 | 108.1 | 1354.5 | 914.793 | 1.10361 | Cocoa, Roast Beef, Roasted Nut | |

| 17 | Unidentified 3 | \ | \ | 0 | 1207.3 | 672.711 | 1.15699 | ||

| 18 | 2-Acetylfuran | C1192627 | C6H6O2 | 110.1 | 1543.9 | 1377.171 | 1.12539 | Balsamic, Cocoa, Coffee |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).