3. Landscape analysis: Types of Evidence Produced and Used in the Agricultural Sector in West Africa

Across ECOWAS, evidence is conceptualized broadly, encompassing multiple sources and types of knowledge used to inform agricultural policymaking. Although the ECOWAS Commission does not provide a formal, explicit definition, literature reviews and stakeholder interviews indicate that evidence primarily includes research outputs generated by universities and national research centers, consultancy studies, and statistical data produced by national institutes of statistics (ECOWAS, 2024; Thoto et al., 2023; Uneke et al., 2022). Additionally, insights, perspectives, and information shared by diverse interest groups—such as the private sector, farmers' organizations, and civil society actors—are also recognized as valuable forms of evidence, significantly contributing to the formulation and orientation of agricultural policies within the region.

3.1. Agricultural Data System

At the country level, each West African nation is engaged in efforts to collect agricultural data, with the National Agricultural Census being a key example. However, the data collected is often outdated and not detailed enough to support policy decisions (Bouët et al., 2024; Carletto et al., 2017; Hollinger & Staatz, 2015). For example, data from the World Bank Statistical Capacity Index reveal an inconsistency in the conduct of agricultural censuses across the West African nations examined between 2016 and 2020 (World Bank, 2021). While some countries like Cabo Verde, Burkina Faso, Cote d'Ivoire, Niger, Senegal, and Togo demonstrate a relatively consistent pattern of having conducted at least one census within the preceding decade for each year, a substantial number of countries, including Benin, Mali, Nigeria, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea-Bissau, exhibit either periods of absence or complete lack of recent census data within the observed timeframe. This inconsistency highlights a critical weakness in the regional agricultural data ecosystem. Also, the data tends to focus primarily on crop production, which provides only a partial picture of the agricultural ecosystem. Effective agricultural data systems should go beyond basic metrics like crop yields and encompass critical components of the agricultural value chain, such as access to seeds, fertilizers, and market data—both formal and informal.

Moreover, data on key areas like seed systems, fertilizer markets, and arable land often exist in silos across the private sector (e.g., East West Seeds’ sales data, Omnia Fertilizer’s market analysis), government entities (e.g., agricultural inputs import from customs agencies), civil society organizations (e.g., ROPPA’s farmers member data), and international organizations (e.g., AfricaRice’s variety research, IFDC’s market studies, FAO’s land cover data). This fragmentation hinders comprehensive analysis and timely decision-making. Additionally, agricultural data is often generated within the framework of large, donor-funded projects, which compromises the sustainability of these data collection efforts and limits their long-term impact. A notable example in the region is the West Africa Agricultural Productivity Program (WAAPP), funded by the World Bank from 2011 to 2019. While WAAPP successfully established a system for data collection, analysis, and reporting on agricultural technologies, research skills, and agricultural productivity at both national and regional levels (World Bank, 2020), respondents from national agricultural research institutes in the region have reported that the system is no longer functioning at its previous capacity since the project’s conclusion.

At the regional level, agricultural data consolidation and analysis are particularly low, which impedes the ability to track agricultural trends and formulate effective regional policies. In many cases, international databases such as FAOStat or the World Bank Open Data platform are more widely regarded and trusted than national databases. As some respondents have highlighted, they prefer FAOStat because it has comparable datasets, it is more easily accessible than national agricultural databases and it has recognized authority in food and agriculture statistics.

Under ECOWAP, ECO-AGRIS (ECOWAS Agricultural Information System) was created to address these challenges. ECO-AGRIS is intended to be a regional agricultural information system that monitors food security at both the regional and country levels. Developed with technical assistance from CILSS (the Permanent Inter-State Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel), ECO-AGRIS was designed to better inform decision-making and policy processes. Following the conclusion of the European Union’s €18 million funding, the ECOAGRIS system has been inactive since 2019. This inactivity stems from persistent challenges related to capacity, coordination, and funding, which have collectively prevented the timely circulation of crucial agricultural data necessary for effective decision-making in the region (ECOWAS, 2024; European Union, 2016). Despite its potential, ECO-AGRIS has yet to fully realize its role in establishing and maintaining a good agricultural data system in West Africa.

3.2. Research in the West African Agricultural Ecosystem

Research in the agricultural sector in West Africa involves a diverse array of actors, each contributing to the generation of knowledge in different ways. Key contributors include universities, national agricultural research centers, international research organizations, think tanks, consultancy firms, and regional organizations. While each plays a critical role, there are significant gaps in the overall coordination and effectiveness of research, especially in terms of its translation into policy.

At the national level, universities and national agricultural research centers are essential sources of agricultural knowledge. However, there is a noticeable gap in formal mechanisms to ensure that the research conducted in these institutions is translated into actionable policy insights. Despite producing a large body of knowledge, universities often lack the institutionalized structures that would enable them to engage directly with policymakers or inform the ECOWAP framework. For instance, in Benin—as is the case in many West African countries—universities and faculties of agriculture fall under the Ministry of Higher Education rather than the Ministry of Agriculture (Thoto et al., 2023) This institutional arrangement presents a structural barrier that limits the systematic integration of academic research into agricultural policymaking processes.

Consultancy firms and individual consultants, both local and international, are highly active in the knowledge production space in West Africa, even though they are not classified as research centers. These firms and individuals often dominate agricultural research activities by responding to calls for services or project-based assignments. As a result, many reports and studies in the agricultural sector used by institutions like ECOWAS are produced by consultants rather than academic or research institutions. This dynamic is partly due to the structure of funding and procurement processes in the region, where projects often require external “service providers” rather than institutions like universities to carry out research or produce reports. Additionally, one interviewee from the study highlighted another reason, stating that “officers in development institutions tend to prefer reports from consultants rather than university researchers because academic studies are often perceived as overly scientific, theoretical, and disconnected from agricultural practical realities.” Consequently, consultancy firms such as IRAM, Inter-Réseaux, LARES, SAHEL Consulting and individual consultants have become important contributors to the knowledge base that informs initiatives like ECOWAP.

At the regional level, CORAF (West and Central African Council for Agricultural Research and Development) is tasked with playing the role of the anchor institution for agricultural research in the region. However, the region is crowded with multiple research institutions, which often results in fragmented efforts and a lack of coordination. CGIAR centers, CILSS and the OECD Sahel and West Africa Club also play significant roles in regional agricultural research, but there is a continued need for more consolidated efforts and enhanced regional analysis.

The agricultural research agenda in West Africa is largely driven by donor funding (Arvanitis et al., 2022; Beintema & Stads, 2017). This reliance on external financing means that research priorities are often aligned with donor interests and funding cycles, rather than long-term regional needs. The absence of a formal system to track and document agricultural research needs at the regional level by ECOWAS further compounds this issue. As a result, agricultural research is often fragmented, with various organizations pursuing research agendas that may not be fully aligned with the needs of the region’s agricultural policy.

Policy research, in particular, remains a limited area of focus. While there is extensive research on the biophysical aspects of agriculture, less attention has been given to the policy dimensions such as policy design, regional policy implementation, impact evaluation, which are critical for driving institutional reforms, market integration, and governance in the sector. A shift toward policy-oriented research is essential for addressing the complex challenges facing agricultural development in West Africa, such as land tenure, market access, and rural development.

One promising example of regional collaboration in agricultural research is the OECD Sahel and West Africa Club. The Club serves as a platform for data mapping, informed analyses, and strategic dialogue, helping to better anticipate transformations in the region and their territorial impacts. As a member of the Club, ECOWAS benefits from its analyses and insights into regional agricultural issues. This model could be expanded by strengthening the capacity of local think tanks and institutionalizing their role in providing on-demand policy analysis. A more structured approach to engaging think tanks and research institutions at both national and regional levels would help ensure that agricultural policies are grounded in solid evidence and responsive to the needs of the agricultural sector.

3.3. Expert Knowledge as a Type of Evidence in the West African Agricultural Ecosystem

In the West African agricultural ecosystem, expert knowledge plays a critical role in informing policymaking and shaping agricultural strategies. This type of evidence is often captured through workshops, technical sessions, and consultations where non-state actors, researchers, and other technical experts come together to share their knowledge and contribute to the policy process. Expert knowledge in this context refers to the insights, perspectives, and recommendations provided by individuals and organizations with specialized expertise in agriculture, economics, policy, and related fields. These contributions are vital in addressing the complex challenges of agricultural development in the region.

At these workshops and technical sessions, non-state actors such as farmers’ organizations, civil society groups, and local stakeholders provide invaluable knowledge based on their direct experiences with agricultural systems. Organizations like ROPPA (the West African Network of Farmers' Organizations), which represents the interests of smallholder farmers, contribute their practical insights into issues such as market access, land rights, and food security. This form of knowledge, rooted in the daily realities of farming communities, helps policymakers understand the challenges faced at the grassroots level and design policies that are more responsive to the needs of farmers (Mongbo & Aguemon, 2015). These actors also bring forward indigenous knowledge and traditional agricultural practices, which are often overlooked in formal research but are essential for sustainable and locally adapted agricultural development.

Researchers from universities and other institutions also participate in these forums, offering expert knowledge based on their research findings. While universities and research institutions in West Africa produce significant amounts of knowledge on topics like crop yields, soil fertility, climate resilience, and agricultural technology, this knowledge is not always integrated into the policymaking process. Workshops and technical sessions provide a crucial platform for these researchers to directly interact with policymakers and other stakeholders, ensuring that their findings are translated into actionable policy insights.

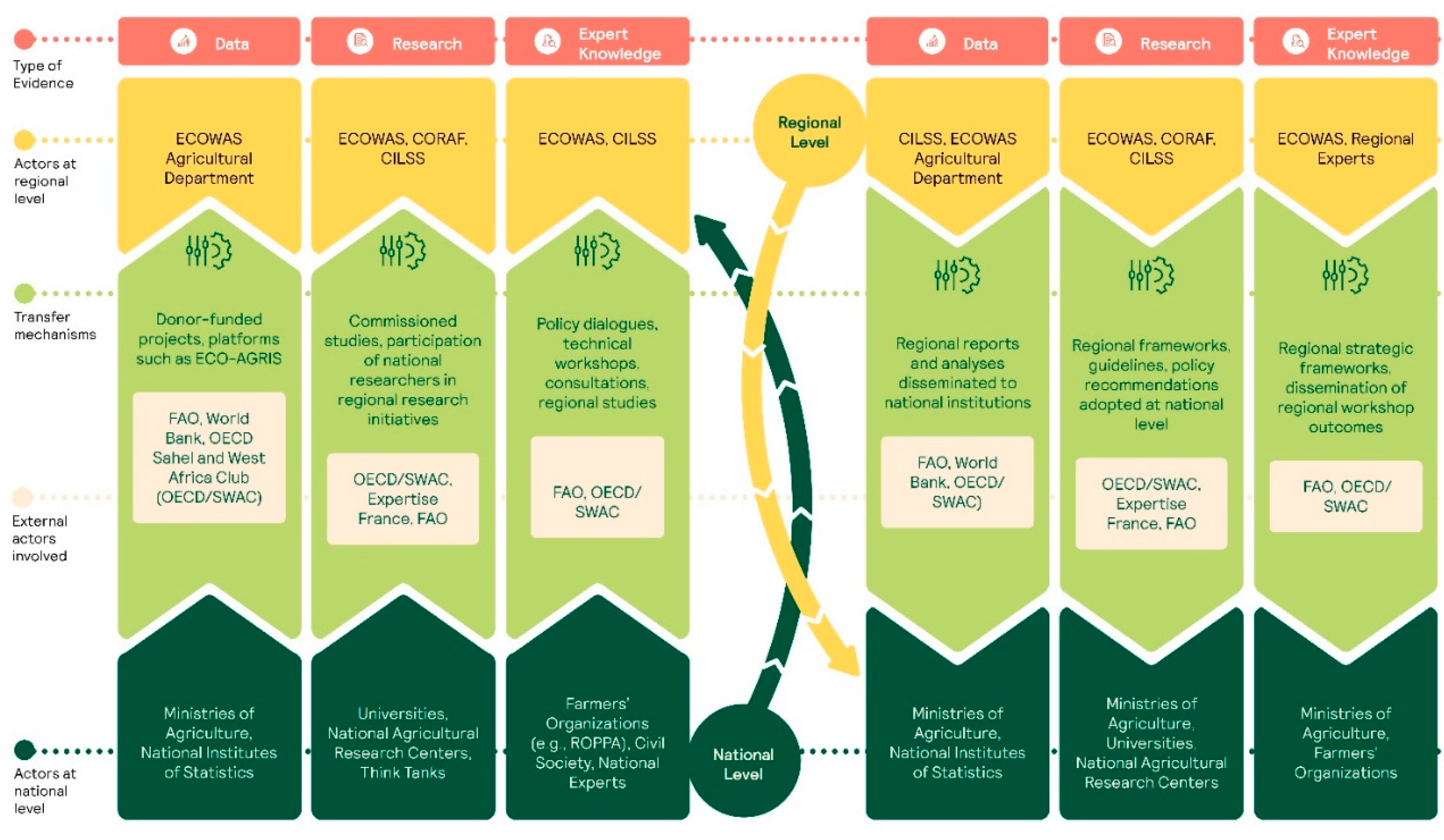

5. Results: Evidence Flow Between National and Regional Ecosystems

The flow of evidence between national and regional ecosystems is a critical aspect of agricultural policy development in West Africa. This process ensures that the policies designed at the regional level are informed by the realities, needs, and experiences of individual countries, while also enabling national policymakers to benefit from regional insights and best practices (

Figure 1). Different types of evidence, such as statistical data, research outputs, expert knowledge, and stakeholder consultations, circulate between the national and regional levels, each playing a crucial role in shaping decisions that address both local and broader regional agricultural challenges.

5.1. Data

In the context of agricultural policymaking in West Africa, data is primarily collected at the national level, with national institutions such as ministries of agriculture or national institutes of statistics playing a central role in gathering relevant agricultural data. This data typically reflects national agricultural conditions, including production levels, socio-economic indicators, food security metrics, and trade figures. These national datasets serve as the foundational evidence for formulating regional policies and strategies like ECOWAP.

Once collected, data is often shared with regional organizations, such as ECOWAS agricultural department, through specific institutional arrangements. These arrangements are typically tied to large-scale, donor-funded projects, which serve as platforms for data exchange. Ministries of agriculture or national statistics institutes often provide their data to regional organizations for analysis, with the aim of informing regional decision-making. However, while data is transferred to regional instances, such as ECOWAS bodies or other regional organizations, the process often lacks formal, institutionalized mechanisms for ensuring smooth and consistent data flow. This creates inefficiencies and can lead to delays in the analysis and use of data at the regional level.

A significant challenge is the lack of consolidation and analytical capabilities at the regional level. Most national institutions in West Africa face constraints related to data processing and analysis, which limits their ability to generate actionable insights locally. As a result, data is often sent to external institutions or international organizations for processing and analysis. For instance, organizations like the OECD Sahel and West Africa Club (OECD/SWAC) play a pivotal role in analyzing and synthesizing agricultural data at the regional level (Allen, 2017; Staatz & Hollinger, 2016; Valerio, 2024). These organizations consolidate data from various countries and produce regional analyses, which are then shared with stakeholders within the region. OECD/SWAC’s efforts, while important, underscore the gap in regional analytical capacity.

Moreover, data collected at the national level may leave the region entirely before being made available for use at the regional level. International organizations like the FAO and the World Bank often receive national data, which is then processed alongside other international data sources to create global datasets, such as FAOStats and the World Bank Open Data platform. These international platforms then make this data available to regional stakeholders, which adds another layer of complexity and delay in accessing timely and relevant data for decision-making at the regional level.

An important initiative in addressing these challenges was the creation of ECO-AGRIS, the ECOWAS Agricultural Information System. The platform was designed to facilitate the flow of agricultural data between national and regional levels, aiming to create a more streamlined process for data sharing, analysis, and policy formulation. However, despite its potential, ECO-AGRIS has remained inactive since 2019, limiting its ability to play the crucial role it was intended to in enabling real-time data access and analysis. This highlights the broader issue of underutilized regional platforms and the need for sustained commitment and investment in data systems that can bridge the gap between national data collection and regional policy analysis.

5.2. Research

In the West African agricultural policy landscape, research evidence flows both from the national level to the regional level and vice versa. National researchers produce valuable insights that are directly relevant to regional policymaking, and these insights are often captured and integrated into the decision-making processes at the regional level. This flow of evidence plays a significant role in shaping the agricultural policies that are ultimately adopted within the ECOWAS framework.

At the national level, researchers from universities, national agricultural research centers, and think tanks contribute data and findings that can inform regional agricultural policies. In some instances, national researchers are commissioned to provide evidence for regional studies. For example, researchers from national universities often act as regional experts in the development of policy analyses, such as the review of fertilizer policies across ECOWAS countries (Honfoga, 2016). These experts bring valuable national perspectives, ensuring that regional policies reflect the specific needs and contexts of individual countries. By participating in regional research initiatives, national researchers effectively contribute to the creation of regional insights and policy directions, showcasing a clear flow of evidence from national to regional levels.

Regional research, in turn, often builds upon national-level studies to generate insights that are applicable across multiple countries. This process was evident in the development of the ECOWAP policy, where national research findings were compiled, synthesized, and analyzed to create regional insights. In this way, the regional research process benefits from the wealth of data and knowledge generated at the national level. By aggregating national findings, regional research offers a more comprehensive view of the agricultural landscape, identifying shared challenges and opportunities that can be addressed through coordinated regional action.

Research evidence also flows in the opposite direction, from the regional level to the national level. ECOWAS, with the support of regional and international partners such as FAO, Expertise France, CILSS, and the OECD Sahel and West Africa Club, produces various regional studies that inform policy processes at the national level. These regional studies often focus on broader issues such as regional integration, food security, and market dynamics, which have direct implications for national agricultural policies. For instance, regional studies may influence national regulations and policies through the development of regional frameworks and guidelines, such as those related to trade, food security, and agricultural subsidies. National governments then adopt these regional recommendations, integrating them into their own policy frameworks and ensuring alignment with the broader regional objectives.

Through this bi-directional flow of research evidence, both national and regional ecosystems benefit from a more integrated approach to agricultural policymaking. National research informs regional policy frameworks, ensuring that they are contextually relevant and rooted in the realities of individual countries. In turn, regional research provides national governments with valuable insights and frameworks for addressing agricultural challenges at the national level. This symbiotic relationship between national and regional research helps foster a more cohesive and effective agricultural policy across West Africa, contributing to greater regional integration and improved food security outcomes.

5.3. Expert Knowledge

Expert knowledge plays a vital role in shaping agricultural policy in West Africa, and its flow between national and regional ecosystems is a key component of the policy development process. National expertise is regularly mobilized at the regional level, often through policy dialogues, technical workshops, or regional studies conducted by individual national experts or groups of experts from various countries. This process ensures that national contexts and local experiences are reflected in regional policy decisions, helping to make the policies more relevant and effective.

An important way in which expert knowledge flows from national to regional levels is through the participation of interest group representatives such as farmers' organizations and other stakeholders. These organizations, which have national chapters across ECOWAS member states, serve as important vehicles for conveying national insights and experiences to the regional level. By consolidating the views and concerns of their members at the national level, these organizations help shape the positions shared at the regional level. For example, farmers' organizations represent the lived experiences of smallholder farmers, sharing challenges such as market access, land tenure, and food security. These contributions provide policymakers at the regional level with a grounded understanding of the issues facing the agricultural sector in each country.

The knowledge shared through these dialogues and consultations is often a reflection of national experiences, practices, and perspectives. For instance, during policy discussions on agricultural value chains, representatives from farmers' organizations may share practical insights drawn from the realities faced by farmers in different countries. These insights, based on lived experiences, inform the regional policy-making process by highlighting specific challenges and proposing solutions that are both locally relevant and scalable across the region.

Additionally, expert knowledge is contributed through regional studies conducted by national experts. These experts, selected for their technical expertise and deep understanding of national agricultural contexts, often work as part of regional teams to produce research and analysis that informs the broader regional agenda. For example, a study on fertilizers policy in ECOWAS countries may be led by national experts who contribute insights into the local conditions, challenges, and opportunities within their respective countries (Honfoga, 2016) These individual contributions are then aggregated to create a regional understanding of the issue, which can inform policy recommendations for the entire West African region.

In this process, evidence tends to flow more from national to regional levels, where it is consolidated, synthesized, and used to shape broader policy frameworks. The flow of expert knowledge ensures that the regional policies reflect the nuances and complexities of each country's agricultural landscape. This collaborative exchange of expert knowledge between national and regional ecosystems helps create a more inclusive and context-aware policy process, which is essential for addressing the diverse agricultural challenges faced by countries in West Africa.

6. Discussion: Key Insights and Proposals for Improved Evidence Use in Regional Contexts

ECOWAS has long recognized the importance of evidence in guiding policymaking, and this proactive approach has been evident since the early 2000s.

The case study shows that, even in its early stages, ECOWAS took significant steps to mobilize and use data for policymaking, particularly in the development of the ECOWAP policy. From the outset, ECOWAS demonstrated a clear commitment to ensuring that decisions were informed by reliable, evidence-based data, setting a precedent for future policymaking.

In the development of ECOWAP, the organization initiated a thorough diagnostic phase, brought together key stakeholders, and mobilized a consortium of regional and international consulting firms. These efforts produced a range of evidence, including country-specific reports, regional synthesis notes, and statistical analyses that shaped the framework of the policy. This early investment in data collection and research underlines ECOWAS’s recognition of the role evidence plays in crafting policies that address real challenges and opportunities.

Moreover, ECOWAS actively sought out expert knowledge and consultation to guide its policies. The engagement of national experts and consultants in the design of ECOWAP demonstrated the foresight to incorporate a wide range of perspectives and evidence sources into decision-making, ensuring that policies would be both data-driven and contextually relevant.

This early proactive approach to evidence use reflects a strong institutional commitment to informed decision-making. ECOWAS’s initiatives set a model for how regional organizations can leverage evidence to drive policy success. Building on this foundation, ECOWAS can further institutionalize evidence use throughout the entire policymaking process, from design to implementation, to ensure policies remain responsive and adaptable to emerging challenges. This could include creating dedicated platforms for continuous data collection, analysis, and feedback, ensuring evidence is a central component of decision-making at every stage.

The evidence landscape in ECOWAS's agricultural policymaking is dominated by external actors, such as consultancy firms and international organizations, with universities and national research centers playing a marginal role despite their potential contribution.

In the process of evidence production for agricultural policymaking in ECOWAS, a distinct gap exists between the local production of knowledge and its use in regional policy formulation. While national institutions, including universities and agricultural research centers, generate valuable evidence, they are not consistently integrated into the policy process at the regional level. Instead, consultancy firms – both local and international – often dominate the agricultural knowledge production landscape. These firms are frequently hired for specific projects and are responsible for producing much of the data and reports that inform policy.

International organizations like FAO, the World Bank, and the OECD Sahel and West Africa Club also contribute significant data and research to regional policymaking, acting as key external providers of evidence. For instance, the OECD/SWAC consolidates regional agricultural data and provides analytical insights. These organizations, while offering crucial support, also distance evidence production from the local context, as much of the analysis happens externally, particularly in Paris for OECD/SWAC, rather than within West Africa itself.

The marginalization of universities and national research centers is a critical issue. While individual researchers may participate as experts in regional policy discussions, there is no formal mechanism for universities to systematically contribute to policy processes. Their involvement is largely ad hoc and mediated through consulting firms or as individual experts, rather than through institutionalized engagements that would allow for a consistent flow of research directly influencing regional policies.

ECOWAS should work towards institutionalizing the involvement of universities, national research centers, and think tanks in the regional policymaking process. Just as agricultural producer organizations have successfully found a place in policy discussions, universities and think tanks could similarly form a collective force of proposal to ensure their voices are heard. A formalized framework could be established to facilitate the consistent integration of academic research into policy dialogues, ensuring that evidence generated at the national level is effectively channeled into regional policy development. This could involve the creation of dedicated research-to-policy units within ECOWAS, linking these units with national research centers and academic institutions. By fostering direct partnerships between ECOWAS and universities, these institutions would have a more substantial, ongoing role in producing evidence for policymaking, enabling them to contribute their expertise and context-specific knowledge at every stage of the policy process. Such a mechanism would help ensure that agricultural policies are grounded in rigorous research and are responsive to the evolving challenges faced by the region.

The lack of formalized mechanisms for data transfer between national and regional levels, compounded by limited regional data analysis capacity, impedes the timely use of agricultural data for decision-making at ECOWAS.

Data is primarily collected at the national level in West African countries, with ministries of agriculture and national statistical agencies being the main actors responsible for gathering agricultural data. However, this data often fails to be effectively utilized at the regional level due to the lack of formal mechanisms for its transfer. While regional organizations like ECOWAS rely on national data to inform policy decisions, the process is ad hoc and dependent on project-specific institutional arrangements, which are often driven by donor funding. This situation results in delays and inefficiencies in the flow of data.

A critical challenge is the lack of regional capacity to consolidate and analyze this data once it reaches regional organizations. National data often needs to be processed externally, such as at the OECD/SWAC, FAO, or the World Bank, which adds an extra layer of delay in providing timely insights for regional decision-making. Even when data is shared within the region, ECO-AGRIS, the ECOWAS Agricultural Information System, was designed to facilitate data sharing but has been inactive since 2019, further stalling the flow of actionable data within ECOWAS.

Moreover, the reliance on external organizations for data processing results in a disconnection between the regional context and the analytical approach used. Data collected from different countries is often processed in a manner that might not fully reflect the unique socio-economic and agricultural contexts of each nation, thus limiting the effectiveness of the resulting analyses for regional policymaking.

To improve the flow and use of data, ECOWAS should prioritize the activation and strengthening of the ECO-AGRIS platform to facilitate real-time data access and analysis. Additionally, there is a need for investment in regional data analysis capabilities to ensure that agricultural data can be processed locally by trained experts who understand the regional context. This would reduce the dependency on external actors and ensure that regional decision-making is based on accurate, timely, and contextually relevant data.

The flow of research evidence between national and regional levels is fragmented limiting its effectiveness in influencing regional agricultural policies.

In the context of agricultural policymaking in ECOWAS, research evidence flows both from national to regional levels and vice versa, but this flow is often fragmented and dependent on external actors. National research institutions, including universities and agricultural research centers, produce valuable research that could inform regional policies. However, the connection between national research and regional policymaking is not always formalized. National researchers may contribute to regional research initiatives through participation as experts in specific studies or through their involvement in consulting firms hired for regional projects. For example, national researchers were integral in the regional fertilizer policy review in ECOWAS, providing insights grounded in their local agricultural contexts. Yet, these contributions are often ad hoc and lack institutionalized mechanisms for systematic integration into regional policy processes.

At the regional level, ECOWAS and regional organizations like CORAF, CILSS, and the OECD Sahel and West Africa Club often commission or conduct research that is used to inform national policies. Regional studies and analyses are critical for understanding broader agricultural trends and regional integration opportunities. These studies, while valuable, are typically commissioned by external donors or international organizations, meaning that the research agenda is often shaped by the priorities of these external actors rather than being driven by regional needs. Furthermore, the reliance on international research institutions for regional studies results in a disconnection between the research process and the local context. As a result, while regional studies may generate useful insights, they often do not capture the full complexity of national agricultural realities.

Research evidence also flows in the opposite direction, with regional studies informing national policies. For example, ECOWAS's regional frameworks, such as the RAIP and NAIPs, provide guidelines and strategies that are adopted at the national level. These frameworks are shaped by regional research, but the degree to which they are adopted or adapted by national governments often depends on national priorities and the level of engagement from local stakeholders.

However, this bi-directional flow of research evidence is impeded by a lack of formal coordination and integration mechanisms. The absence of a structured framework to track research needs at the regional level, as well as limited engagement between national research institutions and regional policymakers, means that research findings are not always used effectively. Research that could significantly influence regional policy is often sidelined due to gaps in the integration process and the fragmented nature of the agricultural research ecosystem.

To enhance the flow and use of research evidence, ECOWAS should establish a formal mechanism for continuous engagement between national research institutions and regional policymakers. This could involve the creation of a regional research coordination body that actively facilitates the exchange of research evidence between national and regional levels. Additionally, ECOWAS could work to ensure that research agendas are driven by regional needs rather than external funding priorities. By strengthening the institutional framework for integrating research into policy development, ECOWAS can create a more coherent and effective system for evidence-informed policymaking across West Africa. Moreover, fostering partnerships between national universities, research centers, and regional bodies will ensure that both national realities and regional objectives are reflected in agricultural policies.

Expert knowledge, particularly from non-state actors like farmers’ organizations, is essential in shaping regional agricultural policies, but its flow from national to regional levels remains largely informal and dependent on strategic interests.

Expert knowledge, especially from national stakeholders such as farmers' organizations, civil society, and technical experts, plays a pivotal role in informing regional agricultural policies. These groups provide valuable insights based on their on-the-ground experiences and understanding of local agricultural systems. Farmers' organizations, like those represented by ROPPA, offer important perspectives on issues such as market access, food security, and land rights, which are often overlooked by formal research but are critical for effective policy design.

However, the flow of this expert knowledge from national to regional levels remains largely informal. Non-state actors often share their insights during policy dialogues and technical workshops, where they contribute based on their lived experiences. These contributions are not always integrated into structured, institutionalized decision-making processes. Furthermore, while national experts may participate in regional studies, the lack of formal channels for their continuous involvement in the policy development process means that their influence is often episodic rather than systemic.

In regional policy debates, expert knowledge can sometimes be overshadowed by political and strategic interests. Although knowledge from experts can provide nuanced and context-specific recommendations, regional decisions are often influenced by the political and economic priorities of different stakeholders. In these instances, expert knowledge takes a backseat to competing interests, which diminishes its potential to drive evidence-based policymaking.

To enhance the role of expert knowledge in regional policymaking, ECOWAS should create more structured mechanisms for engaging non-state actors, particularly farmers' organizations, research institutions, and civil society groups. This could include establishing regular consultations with these groups, formalizing their participation in the policymaking process, and creating platforms for continuous dialogue between national experts and regional policymakers. By institutionalizing the flow of expert knowledge, ECOWAS can ensure that regional agricultural policies are better aligned with the needs and realities of local agricultural systems.

External funding plays a central role in driving agricultural research and evidence use in ECOWAS, but it often leads to donor-driven agendas that may not fully align with the region's long-term agricultural priorities or local contexts.

A critical factor influencing the production and use of evidence in agricultural policymaking in ECOWAS is the dominance of external funding. Most of the agricultural research and evidence generation activities, both at the national and regional levels, are supported by international donors such as the EU, the World Bank, USAID, and various UN agencies. This reliance on external funding shapes the research priorities and methodologies, as they often reflect the interests and goals of the donor organizations rather than the regional or national agricultural development strategies.

For instance, the development of the National Agricultural Investment Plans (NAIPs) and the Regional Agricultural Investment Plan (RAIP) was largely influenced by donor funding. While these plans were instrumental in driving agricultural development goals in West Africa, the lack of long-term, sustainable funding from ECOWAS member states has meant that these plans often depend on external actors for implementation. This dependency leads to the misalignment of regional priorities with the funding mechanisms, as donor-driven agendas may focus on specific issues that are not necessarily the most pressing for the region in the long term.

The external financing model also impacts the institutionalization of evidence use. For example, organizations such as the OECD Sahel and West Africa Club, the FAO, and the World Bank often conduct research and provide evidence that directly feeds into regional policy processes. However, these organizations are primarily driven by their own funding cycles and mandates, which means that evidence production is not always aligned with the specific needs of ECOWAS or the agricultural sector in the region. As a result, policy decisions may be shaped by evidence that does not fully reflect the local context or the evolving priorities of West African countries.

Moreover, this funding model undermines the internalization of knowledge production and analysis within regional institutions like ECOWAS. The reliance on external consultants and international organizations for research and data analysis has hindered the development of strong, local analytical capacities within the region. As a result, ECOWAS and its member states lack the sustainable, institutionalized capacity to generate and analyze agricultural data independently. This external dependency limits the ownership and control that regional actors have over the policymaking process.

To reduce the over-reliance on external funding, ECOWAS should prioritize the development of local research and analytical capacity. This could involve investing in the institutional strengthening of regional bodies like CORAF, CILSS as well as national research centers and universities, to foster more locally-driven agricultural research. ECOWAS could also create mechanisms to better align donor funding with regional priorities, ensuring that research agendas and funding streams are more responsive to the long-term agricultural needs of the region. Additionally, ECOWAS should work to establish a sustainable funding model that encourages member states to take more ownership of agricultural policy development and research funding. This would not only promote more regionally relevant evidence but also ensure that West Africa has the capacity to respond to its agricultural challenges in a way that is independent and self-sustaining.

While evidence use is well documented during policy planning and formulation, there is a critical need to sustain this evidence culture throughout the implementation phase.

While evidence use in agricultural policymaking in ECOWAS is generally well-documented during the policy planning and formulation phases, the integration of evidence into the implementation phase remains vague and less transparent. This is particularly evident in the case of ECOWAP, where substantial effort is made to incorporate data, research, and expert knowledge into policy design. However, the actual utilization of evidence in the execution of these policies—and the mechanisms for ongoing monitoring and evaluation—are less well defined, pointing to a significant gap in the "evidence culture" during policy implementation.

The planning stages of the ECOWAP framework, for instance, benefit from extensive consultations, data gathering, and expert opinions, leading to detailed reference documents and policy scenarios. Stakeholders from different sectors—such as national governments, international organizations, consultancy firms, and civil society—play an active role in providing evidence, which is then synthesized into the policy’s guiding principles. This evidence-informed planning phase is crucial for shaping a coherent regional agricultural strategy that is aligned with the development goals of ECOWAS.

However, as the policy transitions from planning to implementation, the evidence that informed its creation appears to become less prominent in guiding the day-to-day decisions, operations, and monitoring of the policy’s outcomes. A key issue is the lack of a well-established evaluation culture within ECOWAS, which makes it difficult to continuously track the effectiveness of the policies once they are implemented. This issue is further compounded by the absence of a formalized framework for evaluation, as seen in the early years of ECOWAP's implementation. The 2006-2010 action plan, for example, laid out ambitious goals for agricultural development but lacked concrete mechanisms for monitoring progress or conducting impact evaluations. This oversight meant that, despite having a robust policy design phase, the actual assessment of whether those policies were achieving their intended outcomes was weak or incomplete.

As highlighted in the case study, while ECOWAS and its partners have made some attempts to evaluate the effectiveness of ECOWAP, such as through the FAO’s 2015-2016 evaluation and the 2015 International Conference on West African Agriculture, these efforts have often been limited. The ad-hoc nature of these evaluations—often led by external organizations—suggests a lack of institutionalized processes for regularly collecting evidence during implementation. Moreover, without a strong evaluation culture embedded within the policy cycle, there is little ongoing feedback loop that can inform adjustments or improvements to the policy.

The lack of consistent M&E mechanisms at the regional level further exacerbates this issue. Although the ECOWAP framework includes M&E components, these systems often face challenges such as inadequate funding, lack of coordination, and poor data quality. As a result, the evidence that should be used to inform policy adjustments is not consistently gathered, analyzed, or acted upon. Furthermore, since national-level research and data collection are often externalized or fragmented, it becomes challenging to track the policy’s impact in real time, which further weakens the connection between evidence and implementation.

An important consideration is that the policy implementation phase requires a different kind of evidence use—one that is not only based on initial data but also on continuous monitoring and adaptation. The absence of an effective feedback mechanism prevents the necessary adjustments that could improve policy effectiveness and achieve desired agricultural outcomes. A more integrated evaluation process is needed to maintain the evidence culture throughout the policy lifecycle.

To address this gap, ECOWAS should invest in building a stronger internal evaluation culture, one that moves beyond the planning and design phases and into the implementation phase. This could include strengthening the capacity of national institutions to conduct real-time evaluations and fostering a more collaborative relationship between regional bodies like ECOWAS and national actors. Additionally, establishing formalized M&E frameworks with clear indicators and regular assessment intervals would ensure that evidence continues to guide policy decisions during implementation, enabling timely interventions where needed.

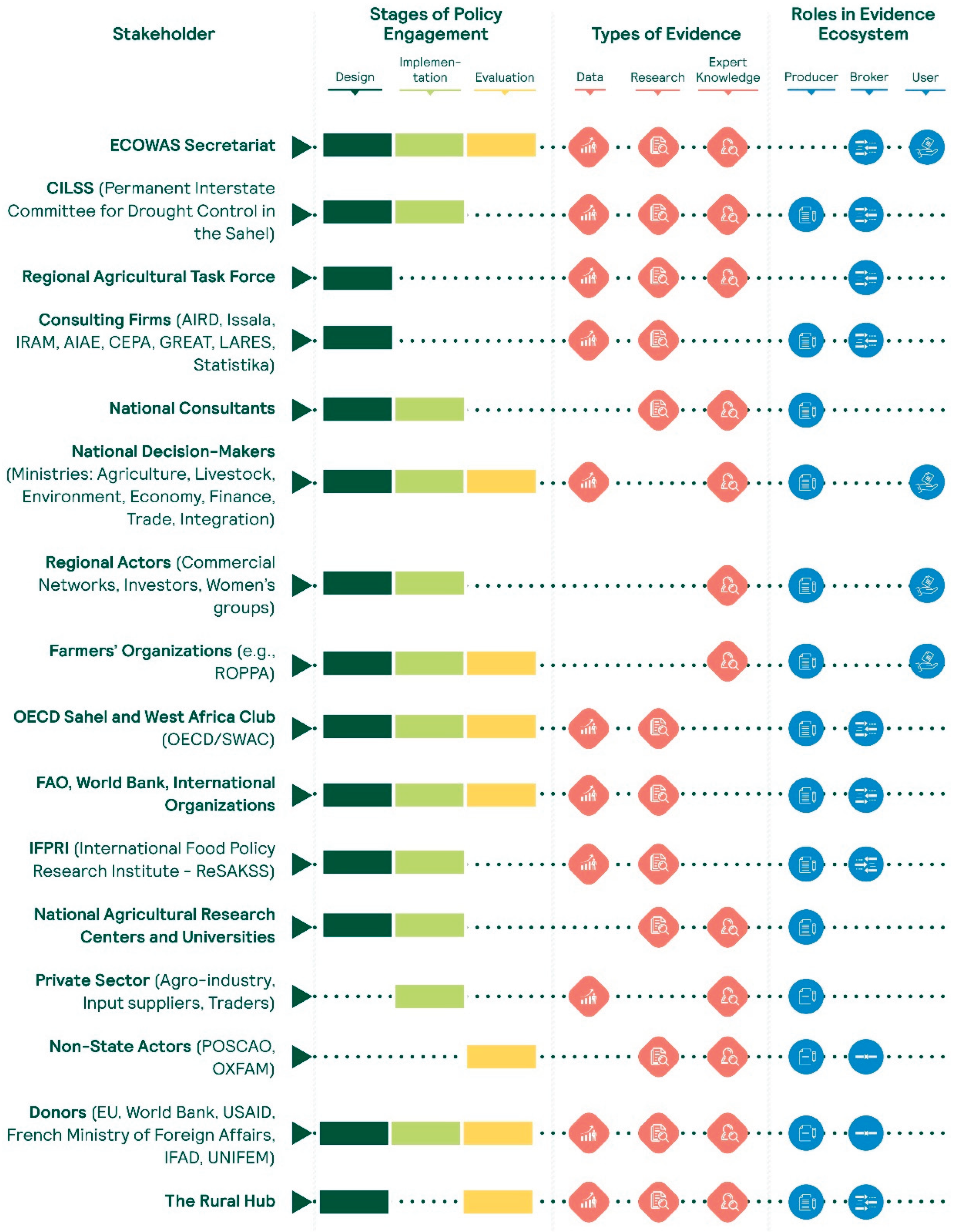

The multiplicity of actors involved in regional agricultural policymaking creates fragmentation and undermines effective coordination and coherence of efforts within ECOWAS.

The ECOWAS agricultural policy ecosystem includes a diverse array of stakeholders—regional institutions, national governments, international donors, development partners, consultancy firms, research institutions, private sector entities, and civil society organizations (

Figure 2). ECOWAS demonstrated leadership in establishing a clear regional policy framework, notably through the Regional Agricultural Investment Programme (RAIP) and associated structures such as the Regional Agency for Agriculture and Food (RAAF). However, despite these institutional mechanisms, effective coordination among stakeholders remains challenging.

One significant driver of this fragmentation is the presence of parallel intervention frameworks promoted and funded by various development partners. Institutions such as CILSS (Permanent Inter-State Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel), despite being officially designated as the technical arm for ECOWAS in the implementation of ECOWAP, often independently implement donor-funded regional programmes without direct involvement from ECOWAS bodies (Oxfam 2015). Similarly, WAEMU’s adoption of its separate Programme for Agricultural Transformation highlights the multiplicity of frameworks operating concurrently, sometimes without clear alignment to ECOWAP’s strategic objectives.

Interviewees and analyses emphasize that development partners frequently opt to channel resources through institutions they perceive as less restrictive or more efficient than ECOWAS itself. This perception is partly driven by the limited operational capacity of ECOWAS’s own structures, notably the RAAF, which development partners view as lacking sufficient autonomy, management capacity, and resources. Consequently, large international donors, including the World Bank and European Commission, often choose alternative platforms, further diluting the coordination role of ECOWAS.

Moreover, the ECOWAP Group, initially intended to function as a central coordination mechanism for regional development partners, has struggled to convene major donors consistently and effectively. The lack of systematic and integrated coordination mechanisms between ECOWAS, WAEMU, CILSS, and other regional or international actors has significantly reduced the coherence of agricultural policies and interventions, limiting the effectiveness and long-term impact of regional agricultural initiatives.

To address these challenges, it is essential to establish a unified regional agricultural policy framework that clearly delineates mandates, enhances the autonomy and capacity of ECOWAS structures like the RAAF, and aligns interventions from development partners. Strengthening ECOWAS’s institutional leadership and creating streamlined, effective coordination mechanisms that integrate all actors—including international donors and regional institutions—would significantly enhance the coherence, alignment, and overall impact of agricultural policy interventions across West Africa.