3. The Hydrodesulfurization Process

3.1. Hydrotreating Processes

Among the various processes for obtaining petroleum products free of undesirable heteroatoms, there are operations of great importance for petroleum refining, known as Hydrotreating (HDT) processes. HDT can be applied to a wide variety of streams: solvents, distillates (light, middle, and heavy), residues, and fuels (Alonso, G. et al., 2005).

During HDT, hydrogenation reactions (HID) of unsaturated compounds and hydrogenolysis reactions of carbon-heteroatom bonds (sulfur, metals or metalloids, nitrogen, and oxygen) mainly occur. All reactions are exothermic; therefore, temperature control in the reactor, especially in the catalytic bed, is very important during operation. HDT consists primarily of the reactions HDS, HDN, HDO, and HDM, which are briefly mentioned below (Climent, O. et al., 2012):

• Hydrodesulfurization (HDS). It leads to the removal of sulfur from petroleum compounds by converting them to H2S and products in the form of hydrocarbons with lower molecular weight and boiling points.

• Hydrodenitrogenation (HDN). Nitrogen removal is performed to minimize catalyst poisoning in subsequent processes, as they are a source of coke formation during catalytic cracking and inhibit the reaction by adsorption on acid sites.

• Hydrodeoxygenation (HDO). Oxygenated compounds are present at low concentrations in petroleum, increasing with the boiling point. The process to remove the oxygen present is also carried out.

• Hydrodemetallization (HDM). Traces of nickel and vanadium (330 ppm Ni+V in Maya crude) are present in petroleum, generally in the form of porphyrins or chelating compounds. These compounds can be deposited on catalysts during the conversion process in the form of transition metal sulfides (Ni3S2, V3S4, and V2S3). This deposition poisons the catalytic material, reducing the number of active sites (the area where the substrate binds for catalysis) and impeding the transport of reactants due to a potential blockage of the pores [GOSSELINK, J.W. 1998].

The hydrodesulfurization process eliminates sulfur-containing compounds and, simultaneously, nitrogen-containing compounds, ensuring compliance with environmental regulations established for the import, export, and use of fuels.

Sulfur is one of the main pollutants in diesel and gasoline. Sulfur content in crude oil varies between 1,000 and 30,000 ppm, meaning that removing it from fuels requires a significant economic effort. Growing concerns about pollution, accompanied by stricter environmental regulations, have led to the development of strategies to mitigate the negative effects of sulfur-containing compounds in oil, which can cause malfunctions in plants and refineries, such as catalyst poisoning in catalytic reforming equipment and sulfur dioxide emissions generated by fuel use in vehicles, vessels, furnaces, among others.

Sulfur content in fuels is a concern because, during combustion, it is converted into SOx, which contributes to acid rain; therefore, as sulfur levels decrease beyond a certain point, the health and environmental benefits increase considerably (Climent, M., 2012).

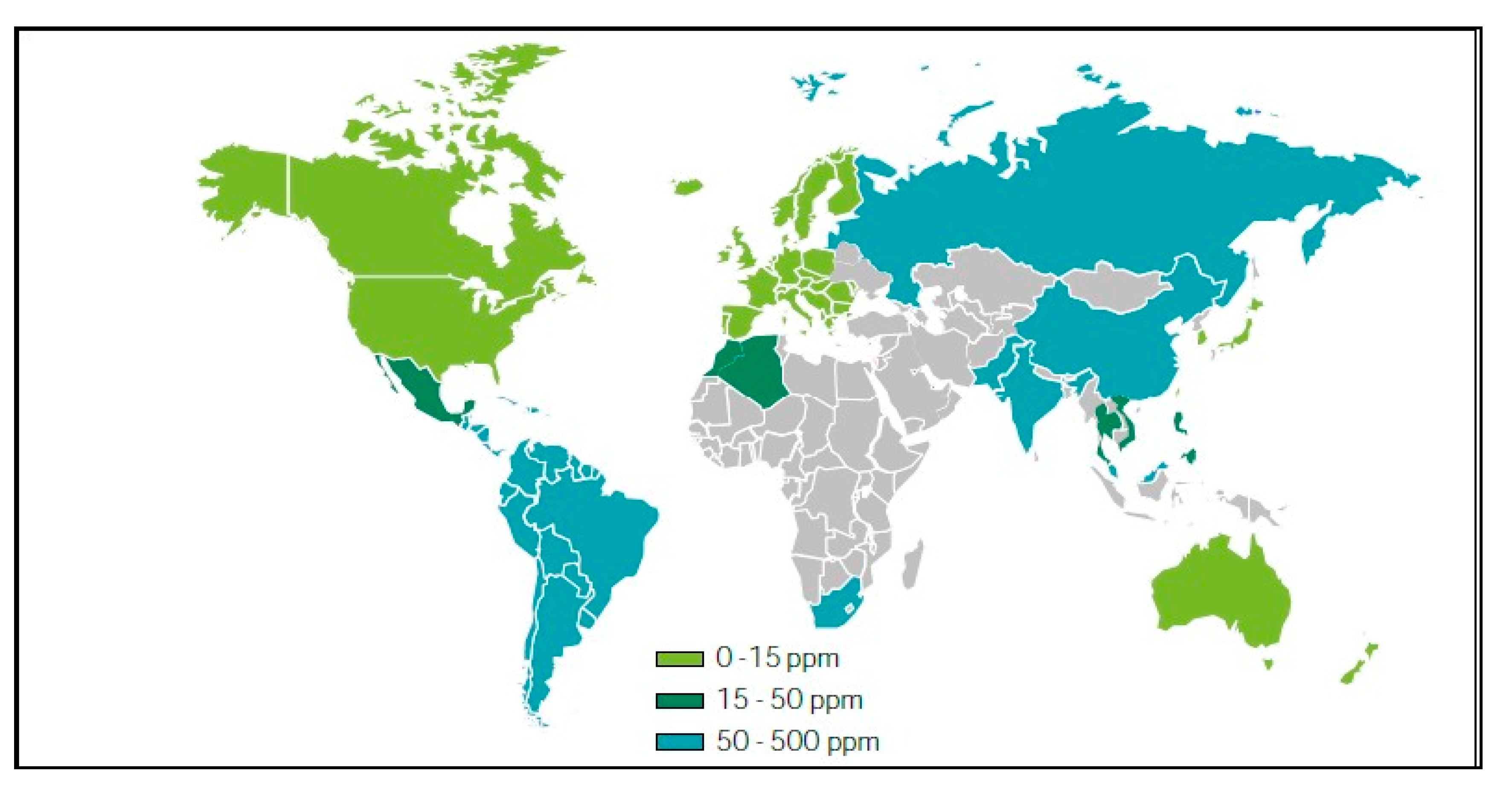

In this regard, NOM-086-SEMARNAT-SENER-SCFI-2011 "Specifications of fossil fuels for environmental protection" establishes the maximum allowable sulfur content in fuels for motor transport, which must not exceed 15 ppm by weight. Consequently, improved processes and more active catalysts are required to reduce the heteroatom content in fuels. Internationally, the permitted sulfur levels in diesel are quite stringent, as shown in

Figure 3.2.

Currently, there are four commonly used hydrodesulfurization processes (

Table 2.3).

Sulfur is a contaminant that can be removed to levels below 500 ppm with the aid of bifunctional catalysts such as NiMo/AlO and CoMo/AlO. Above this value, the remaining sulfur in the middle distillates represents very stable sulfur compounds with dibenzothiophene-type di-aromatic structures (flolaus, A., Marafi, A., & Mohan S.R., 2010).

Deep hydrodesulfurization requires catalysts with higher sulfur removal activity. The active phase of conventional hydrodesulfurization catalysts is composed of sulfided species such as MoS or WS, which are promoted with metals such as Co, Ni, and in some cases, both. Efficient formation of the effective active phase is achieved when the promoter is located at the edges and corners of the MoS crystallites. Therefore, the catalyst preparation and activation method is crucial for obtaining more active catalysts (Flores, O. et al., 2020).

Hydrodesulfurization (HDS) is a process designed to reduce the percentage of sulfur found in petroleum fractions. It is carried out in the presence of hydrogen and a catalyst. Environmental regulations in many countries require more "friendly" transportation fuels with lower sulfur contents (10 ppm in ultra-low sulfur diesel) (Gabriel Alonso Nuñez et al., 2015; Stanislaus, A. et al., 2010).

3.1. Mechanisms of Hydrodesulfurization Reactions

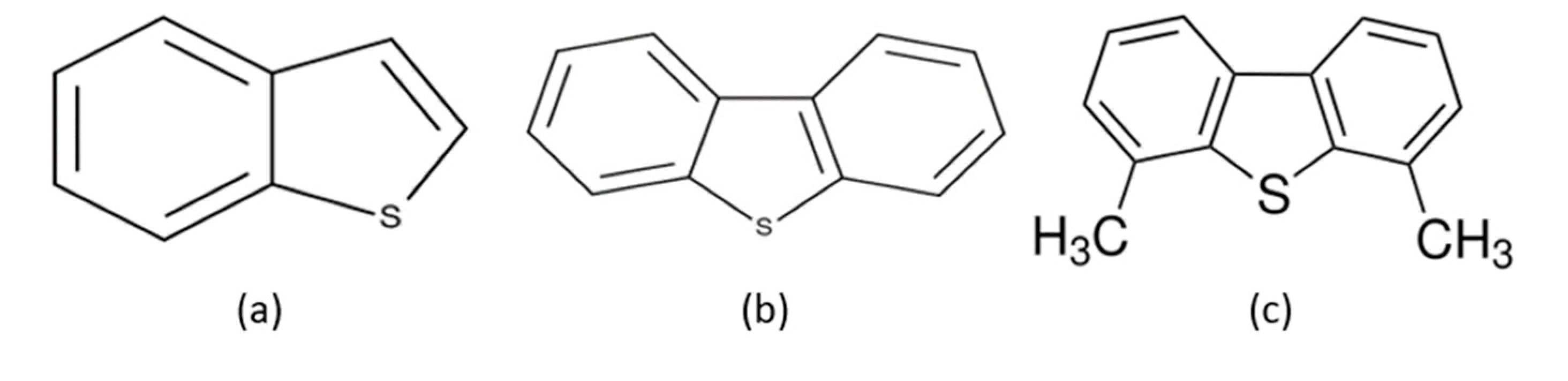

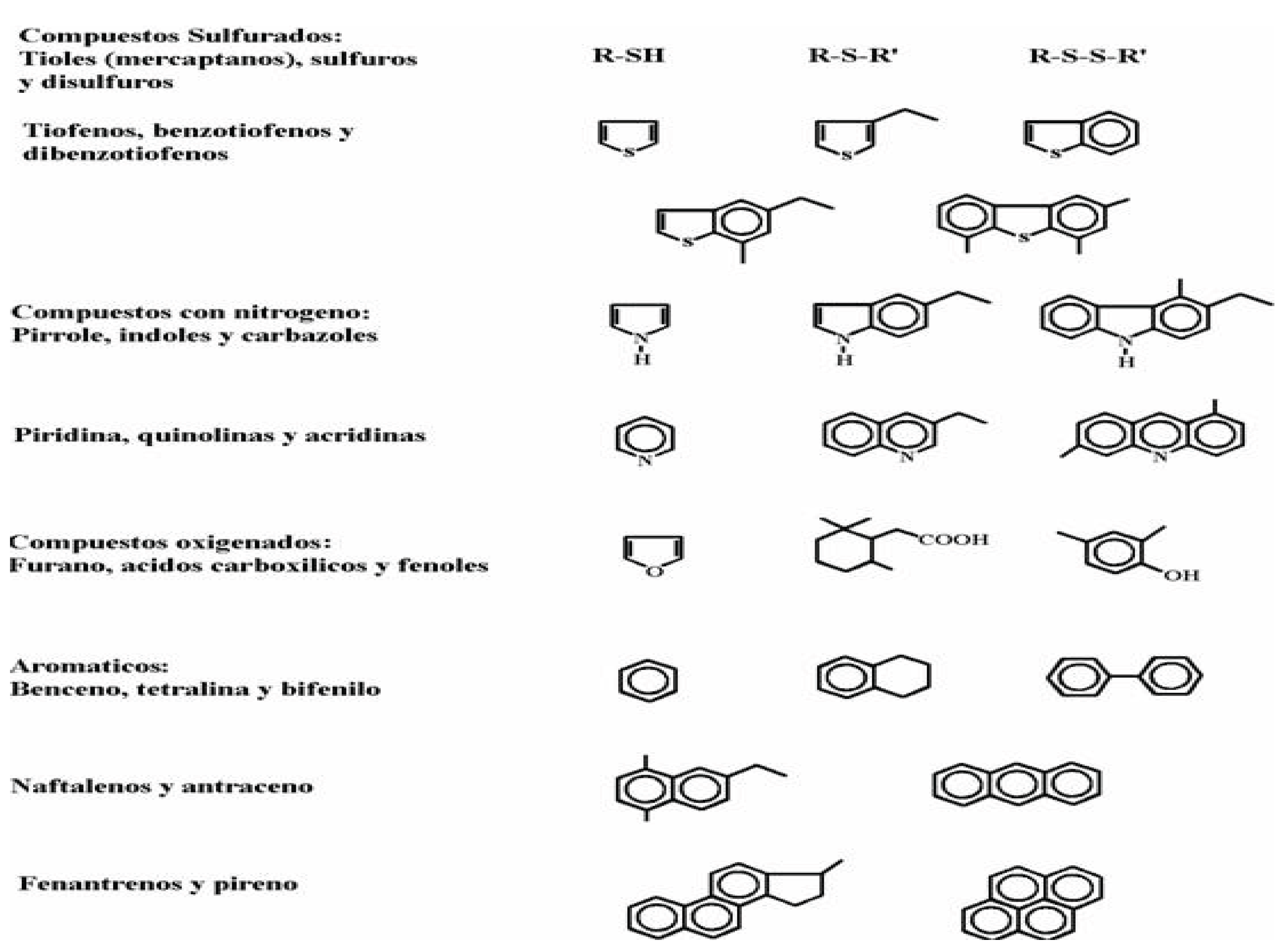

In petroleum fractions, sulfur-containing compounds (

Table 2.4) are generally classified into two types:

• Non-heterocyclic: thiols (mercaptans, SSR), sulfides (RSR), and disulfides (RSSR).

• Heterocyclic: compounds containing several thiophenes (one or more rings), and sometimes with alkyl or aryl substituents.

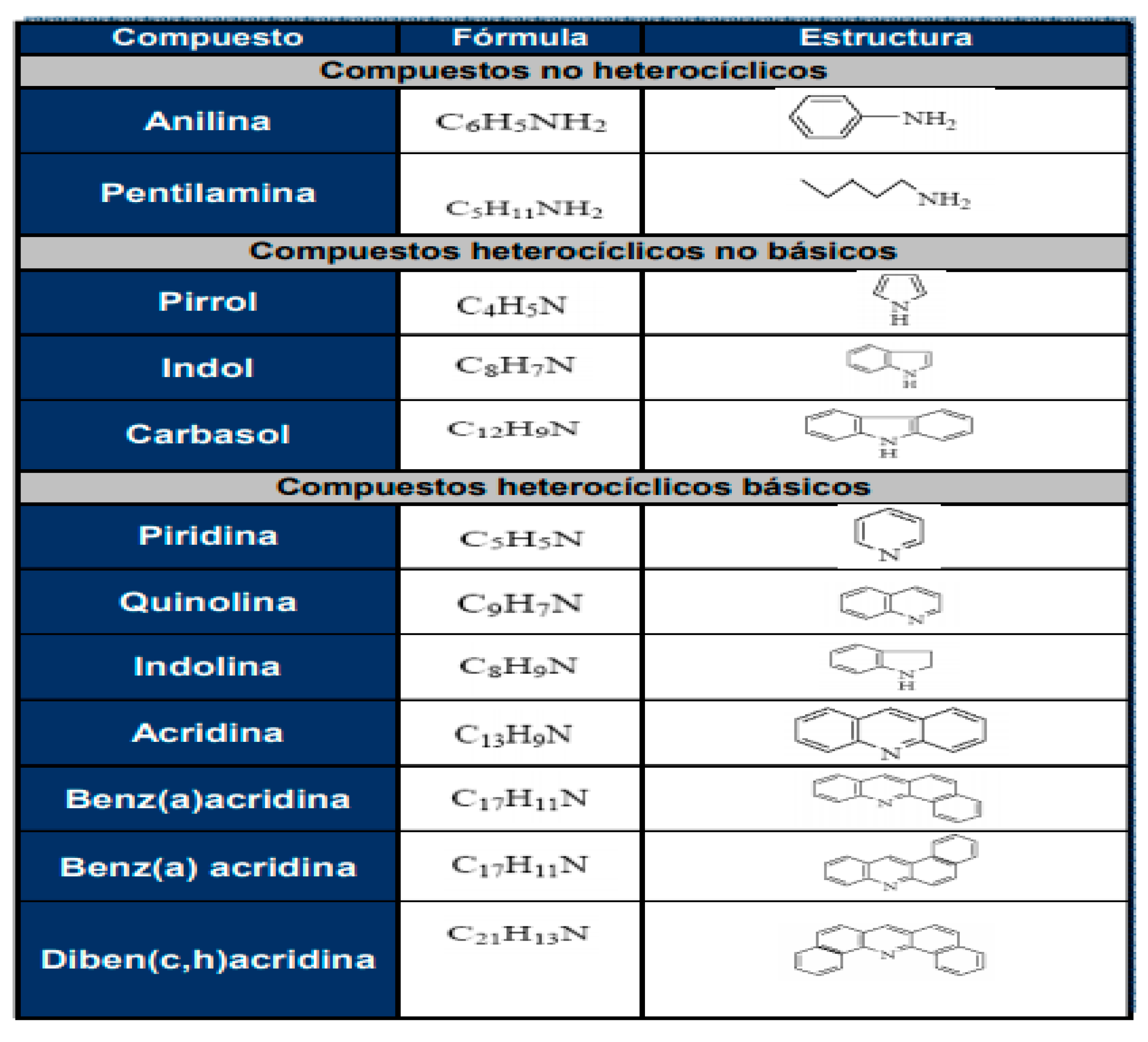

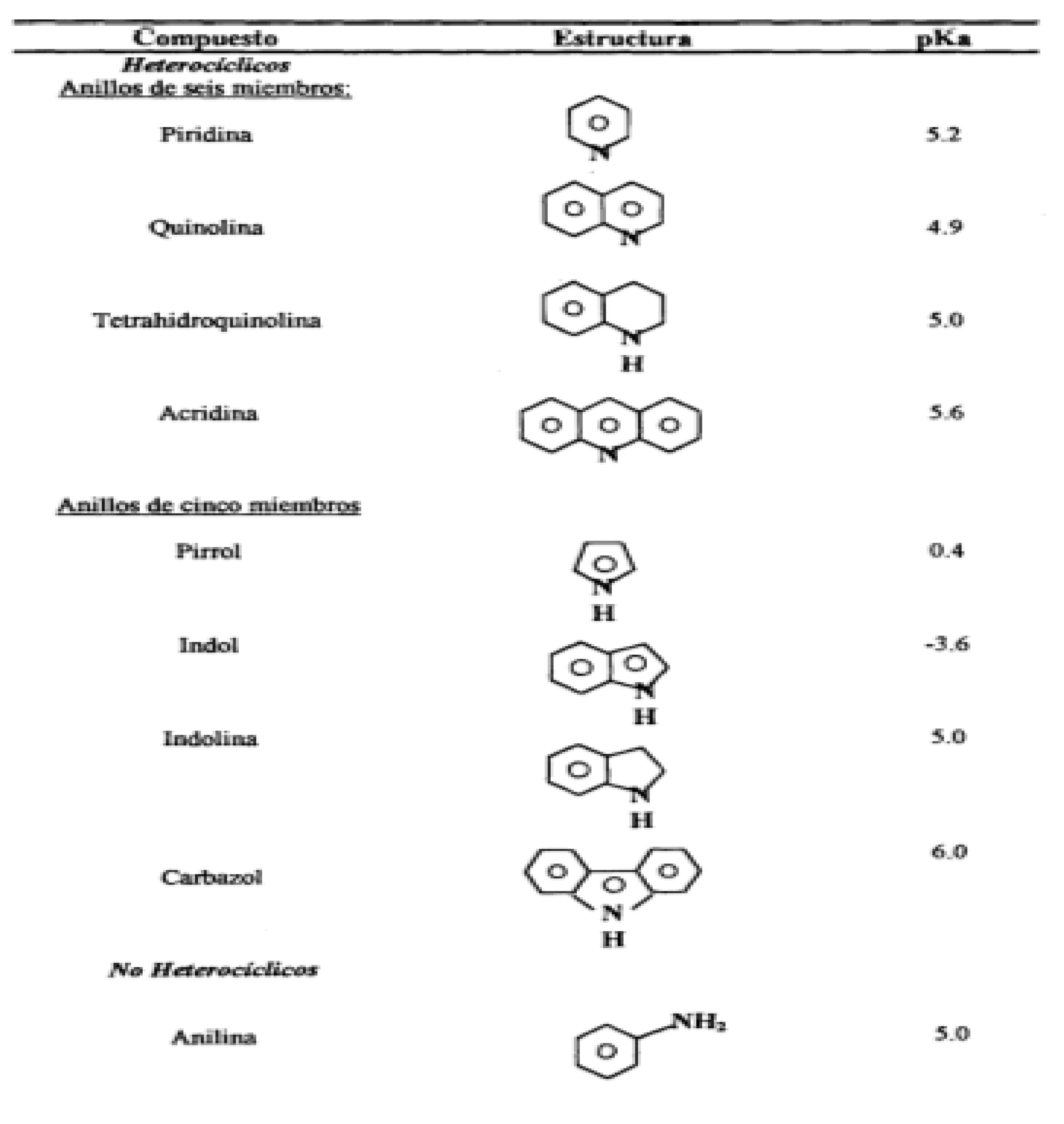

Nitrogen-containing compounds are also divided into two types (Table 2.6):

• Non-heterocyclic: compounds derived from aniline.

• Heterocyclic: compounds such as pyridine, quinolines, and acridines, which are present in larger quantities and are more difficult to process.

Nitrogen, along with sulfur, are the most prevalent elements in Maya crude oil. Most of the sulfur is organically bound, and very little is found as hydrogen sulfide and elemental sulfur. The sulfur species most commonly found in crude oils are alkyl benzothiophene derivatives, dibenzothiophene (DBT), benzonaphthiophene, and penthiophene (

Figure 3.3). Because these compounds are less reactive, they are more difficult to transform by HDT. Therefore, the DBT compound is considered a model molecule for studying the HDS process.

In 1980, Houlla et al (M. HOUALLA. ET COL 1980) proposed in detail the routes followed by the HDS reactions of DBT (

Figure 3.4), which are currently the basis for the study of these reactions. It is observed that the conversion of DBT can be carried out through two parallel routes: by direct hydrodesulfurization (DSD), producing biphenyl (BF), and the second by hydrogenation (HID) acquiring tetrahydrodibenzothiophene (THDBT) or hexahydrodibenzothiophene (HHDBT), followed by desulfurization to form cyclohexylbenzene (CHB) and subsequently bicyclohexyl (BCH).

Nitrogen compounds naturally present in atmospheric diesel fuel and light cycle oil used as feedstock for diesel fuel production have been identified as strong inhibitors of hydrodesulfurization reactions, even when present at very low concentrations (Yongtan Yang, 2008). These nitrogen compounds are also of great importance due to their tendency to strongly adsorb to the catalytic sites of HDS catalysts, causing their deactivation and hindering the hydrodesulfurization rate.

The nitrogen compounds found in petroleum derivatives (fuels or lubricating oils) are classified into two types: heterocyclic and non-heterocyclic. The latter include anilines and aliphatic amines. Heterocyclic nitrogen compounds are usually divided into two groups: those with six-membered pyridine rings and those with five-membered pyrrole rings (A.R. Katritzky, 2010). These two groups of heterocyclic nitrogen compounds have different electron configurations, and therefore interact with the catalyst surface in different ways (some examples are shown in

Figure 3.5).

In contrast, because the nitrogen electron pair of six-membered heteroaromatic rings is not involved in the π electron cloud, it is therefore available to be shared with acids. These compounds are strong bases; due to the electronegative nature of the nitrogen atom in the pyridine ring, six-membered heteroaromatic rings are relatively electron-deficient (π-deficient) compared to their benzene counterparts. Compounds of this type are likely to preferentially use nitrogen to make initial contact with the catalyst surface, provided that the heteroatom is not sterically hindered.

The basicity of these nitrogen compounds allows them to interact with the acidic active sites on the catalyst surface in one of two ways: they can accept protons from the surface (Brönsted acidity) or they can donate unpaired electron pairs to electron-deficient sites on the same surface (Lewis acidity).

Figure 3.6 shows some pKa (logarithm of the reciprocal of the acid ion concentration) values for typical nitrogen compounds from light petroleum fractions (A.R. Katritzky, 2010). The higher the pKa value, the more basic the compound.

As can be seen, the saturated nitrogen of a heterocycle can lead to a higher pKa than the corresponding unsaturated nitrogen (

Figure 3.6). It is important to note that, in terms of pKa, indoline and tetrahydroquinoline behave like substituted anilines.

Catalytic hydrodenitrogenation (HDN) is coupled with hydrodesulfurization during hydrotreating. Although it has long been recognized that HDN is more difficult than HDS, refiners have given it little importance due to the comparatively small amounts of nitrogenous compounds present in conventional petroleum sources and a lack of awareness of the negative effects of these compounds on product stability. This situation, however, is changing, primarily due to the need to process heavy or low-quality crude oils, which are rich in nitrogenous compounds. Currently, conventional HDS technology has been adapted to carry out HDN (T. Ohtsuka, 1977; P. Grange, 1980; H. Tops, 1984), despite the fact that it is often not the most suitable for nitrogen removal (J.R. Katzer et al., 1979).

3.2. Hydrodesulfurization Units

In recent years, catalytic hydrodesulfurization (HDS) has become more important due to stringent environmental restrictions and the lower quality of crude oil. In this context, new specifications for sulfur in diesel have been established in different countries, for example, less than 0.0015% by weight (ultra-low sulfur diesel) in the United States and Canada, while in Japan and Europe, sulfur concentrations have been projected below 0.0010–0.0015% by weight.

Worldwide, experience and research have shown that the production of low-sulfur fuels is affordable with current technology. Incentives, increasing regulations, and taxes have led to the full introduction of low- and ultra-low-sulfur fuels much more rapidly than expected in the United States, Europe, Japan, and Hong Kong. Low-sulfur fuels (50 ppm) allow for greater benefits by incorporating advanced control technologies for diesel vehicles. Diesel particulate filters can be used with low-sulfur fuels, but only achieve approximately 50% control efficiency. Selective catalytic reduction can be applied in this case to achieve NOx emission control greater than 80% (Climent, M., 2012). Ultra-low-sulfur fuels (10 ppm) allow the use of NOx absorption equipment, increasing NOx control to levels above 90% in both diesel and gasoline vehicles. This allows for more efficient engine designs, which are incompatible with current emissions control systems. Particulate filters reach their maximum efficiency with ultra-low sulfur fuels, with a reduction of nearly 100% ppm.

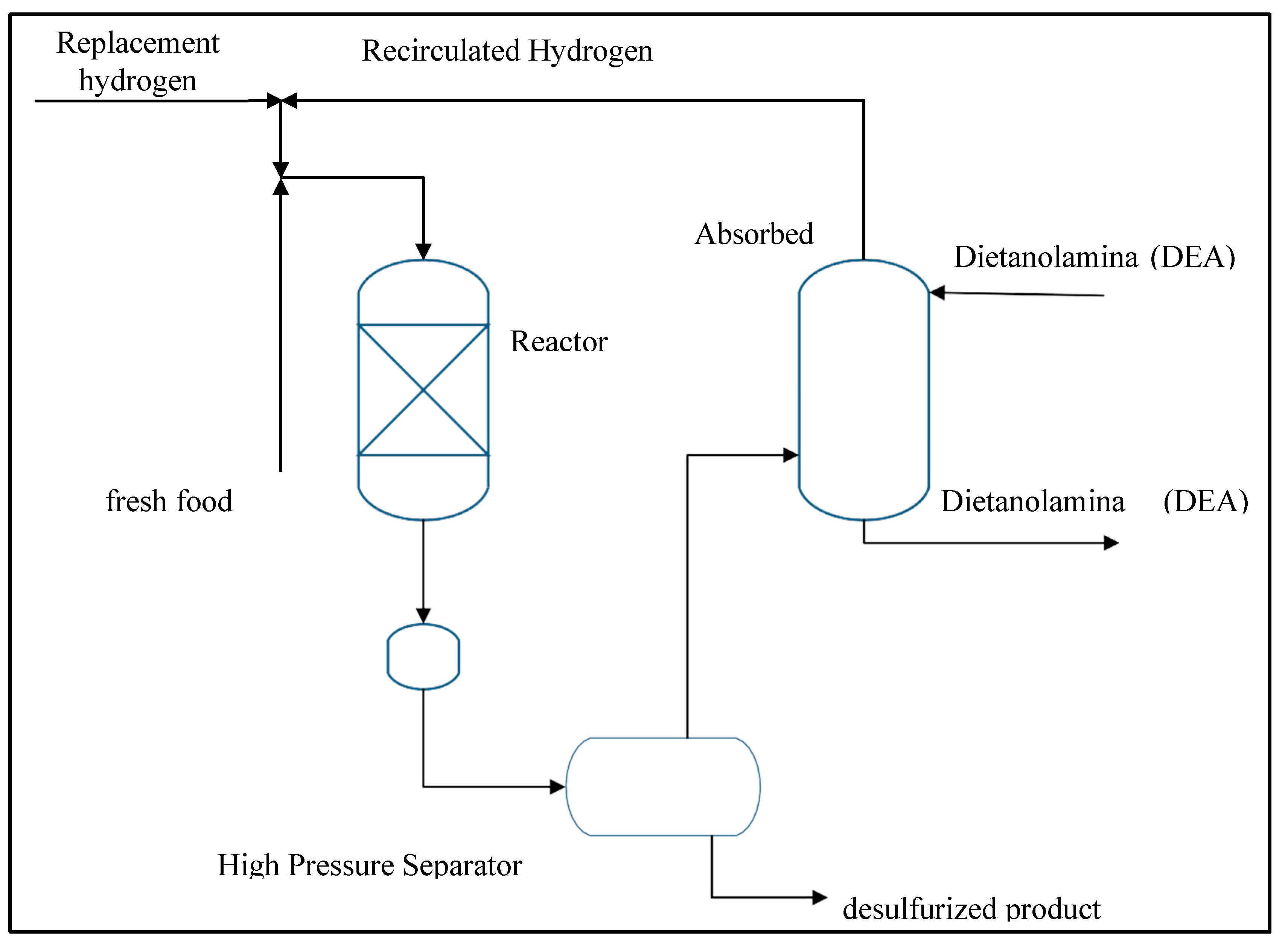

Hydrodesulfurization is the most recognized physicochemical technique for the removal of sulfur-containing compounds (Speight J. G., 2000). In this process, petroleum fractions, both light and heavy, containing sulfur compounds undergo a reaction with hydrogen in the presence of a bifunctional catalyst. This reaction generates hydrocarbons that have lost their sulfur content and hydrogen sulfide (HS). It is crucial to note that HS is continuously removed, as it acts as an inhibitor in HDS reactions and deactivates the catalyst. A typical schematic of a hydrodesulfurization plant (one of the key operations in hydrotreating) is shown in

Figure 3.7.

The level of desulfurization depends on several factors, including the nature of the oil fraction to be treated (composition and types of sulfur compounds present), the selectivity and activity of the catalyst used (active site concentration, support properties, among others), the reaction conditions (pressure, temperature, hydrogen/hydrocarbon ratio, LHSV), and the process design. This process is mainly divided into three sections:

• Reactor section or reaction section.

• Recycle gas section.

• Product recovery section.

3.3. Three-phase reactors

The "Trickle-bed" reactor can be considered a type of fixed-bed reactor operating in three phases: solid (catalyst), liquid, and gas.

Uses of "Trickle-bed" reactors:

• HDT (Hydrotreating of naphtha and heavy gas oils).

• Hydrocracking.

• “Hydrorefining” of lubricating oils.

In HDT reactors, high pressures keep part of the feed in a liquid state, while the gas phase composed of hydrogen and the light oil fraction is produced, and the catalyst is contained in a fixed structure. Solid-liquid-gas reactor systems are used in reactions that occur at relatively low rates and require a considerable amount of catalyst.

3.4. Nature of the Feed

The selection of the correct intensity depends on the type of cut to be hydrogenated. Generally, less stringent conditions are used for distillates; in contrast, more stringent conditions are applied for residues and decomposition products.

3.5. Reactor Operating Variables

HDS reactors are designed to remove sulfur and other contaminants from feed gas oils and supply low-sulfur components for fuel oil blending. Depending on the process operating conditions, various degrees of hydrogenation can be achieved. The main operating variables that allow for proper plant operation are:

• Temperature.

• Hydrogen partial pressure.

• Space velocity (LHSV).

• Hydrogen-hydrocarbon ratio.

Reducing the LHSV improves impurity removal due to increased time spent in the reactor.

Increasing the temperature and hydrogen partial pressure improves sulfur and nitrogen removal, as well as hydrogen utilization. Increasing pressure also promotes hydrogen saturation and limits coke generation. Increasing the space velocity decreases conversion, hydrogen utilization, and coke production. Although increasing temperature improves sulfur and nitrogen removal, excessively high temperatures should be avoided due to increased coke formation.

• Temperature

The severity of the treatment increases linearly with temperature, as reaction rates increase; this causes an increase in coke accumulation on the catalyst, reducing its useful life and effectiveness. Hydrogen consumption rises to a peak and then decreases due to the initiation of dehydrogenation and decomposition reactions. The temperature is kept as low as possible to meet the required activity level, thereby minimizing coke consumption and preventing catalyst inactivation. However, the temperature is gradually increased to counteract the decrease in activity caused by catalyst aging. The temperature ranges between 260°C and 380°C.

• Pressure

The influence of pressure is directly related to the impact of recirculation gas concentration and the hydrogen-to-hydrocarbon ratio. Increasing pressure improves the removal of sulfur, nitrogen, and oxygen, and the conversion of aromatic compounds, in addition to having a positive effect on carbon deposition reduction. The pressure can vary between 10 and 70 kg/cm2.

• Space velocity

In industrial installations, this measurement ranges between 1 and 10 vol (vol h-1).

Reducing the space velocity favors hydrogenation. However, since the catalyst volume remains constant in the system, the only way to decrease the space velocity is by reducing the inlet flow.

• Hydrogen-to-hydrocarbon ratio

It can be noted that an increase in this value results in a reduction of coke deposits on the catalyst, which prolongs its useful life.

Its range varies between 250 and 4,000 ft3/bbl.

4. Catalysts

Catalysts are materials that facilitate the acceleration of a chemical reaction and are not modified during the reaction. The process by which a chemical transformation occurs with the help of a catalyst is called catalysis (Levenspiel, 2007). The basic components of catalysts and the different types that exist can be classified as follows (Green and Perry, 2008).

• Active agent. This is the primary constituent responsible for the catalytic function and includes metals, semiconductors, and insulators.

• Support. Materials frequently used as catalytic supports are porous solids with a high specific surface area, which are classified as follows:

o Inert supports such as silica (SiO2)

o Supports with catalytic activity such as aluminas (Al2O3), aluminosilicates, and zeolites.

o Supports that influence the catalytic activity of the active phase, such as titania (TiO2).

• Promoter. Substances added to enhance the physical and chemical functions of the catalyst are known as promoters. Their purpose is to improve catalytic properties, increasing their activity, selectivity, and resistance to deactivation. Although promoters are added in relatively small quantities, their selection is often decisive for the catalyst's properties. Promoters can be incorporated into the catalyst at some stage of the chemical processing of the catalyst components. In some cases, promoters are added during the course of the reaction. There are two types of promoters:

o Textural, which contribute to greater stability of the active phase.

o Electronic, which increase activity.

The presence of Ni or Co promoters in Mo or W sulfides improves the catalyst's resistance to poisoning. These types of promoters are widely used for a wide variety of feedstocks, but primarily in the treatment of heavy crude oils and vacuum residues [Green and Perry, 2008]. NiMo-based catalysts are more active in hydrogenation reactions than CoMo-based catalysts and consume a greater amount of hydrogen per mole of sulfur removed. NiMo-based catalysts are more selective for nitrogen removal and more tolerant of nitrogen content in streams than CoMo-based catalysts (Green and Perry, 2008).

As a result, research related to the production of ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD) has gained the interest of the scientific community worldwide (STANISLAUS, A., ET AL., 2010). The renewed interest in ULSD research is related to the need for a better understanding of the factors that affect deep diesel HDS down to low sulfur levels. The challenges of producing fuels with ultra-low sulfur contents in an economically feasible manner are one of the main goals for refiners to improve existing technologies and develop new technologies, including catalysts, processes, and reactors. The development and application of more active and stable catalysts are among the most desired options, as they can improve productivity and increase product quality without negative impacts on investment capital. One of the HDS procedures, on which this research project proposal is based, is the increase in catalytic activity through the formulation of better catalysts. In the synthesis of a heterogeneous catalyst, it is of great importance to define the type and characteristics of the support material and the active phases to be incorporated.

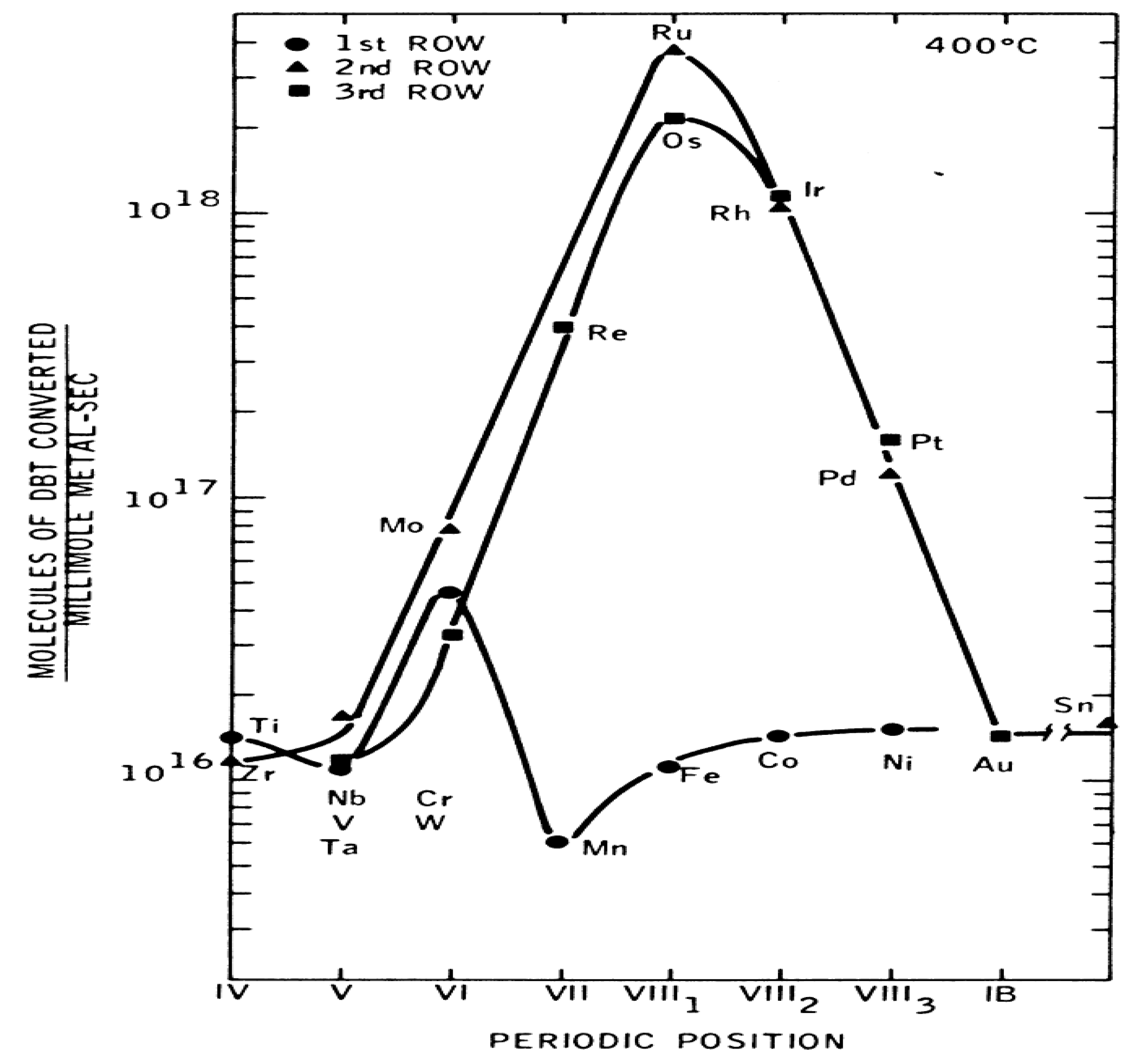

4.1. Transition Metal Sulfides (TMS)

Transition metal sulfides play an important role in the petroleum industry. Due to their resistance to poisoning, TMS are unique catalysts for the removal of heteroatoms (S, N, O) in the presence of large amounts of hydrogen. HDS of organic molecules such as those mentioned above is generally carried out with Mo and W sulfides and is promoted by Group VIII elements such as Ni and Co (Ledoux et al., 1986; Chianelli et al., 2005). The catalytic activity of SMTs has been systematically studied as a function of the metal’s position in the periodic table (LEDOUX, ET AL., 1986; CHIANELLI, ET AL., 2005). DBT was used as a model molecule at 400°C and high pressures, obtaining an HDS activity variation curve of DBT for different transition metal sulfides which is shown in

Figure 4.8. The results indicated that the second and third rows (4d and 5d respectively) of the SMTs are much more active, with a maximum for group VIII metal sulfide systems. However, the first row (3d) did not show a clear behavior; they were less active, showing the lowest activity for manganese. A similar behavior was observed in the HDS of thiophene with SMTs (LEDOUX, ET AL., 1986; CHIANELLI, ET AL., 2005). The order of activity observed was as follows:

Third row: RuS2>Rh2S3>PdS>MoS2>NbS2>ZrS2

Second row: OsSx>IrSx>ReS2>PtS>WS2>TaS2

Catalyst selection for certain processes is based on activity, selectivity, and lifetime studies. This is often a very long and difficult task. Once the right catalyst that provides the desired product quality at a reasonable cost is found, the search for a better catalyst immediately begins (Pecaro, T.A., 1981; Chianelli, et al., 2005).

In hydroprocessing, catalyst selection depends primarily on the required conversion and the characteristics of the processed feedstock. As mentioned above, feed characteristics vary considerably, and the number of impurities and physical properties thus determine the choice of catalyst. This suggests that there is no universal catalyst or suitable catalyst system for hydroprocessing different crude feedstocks. Regarding physical and chemical properties, a wide range of hydroprocessing catalysts has been developed for commercial applications (Che., M.S., et al., 2006).

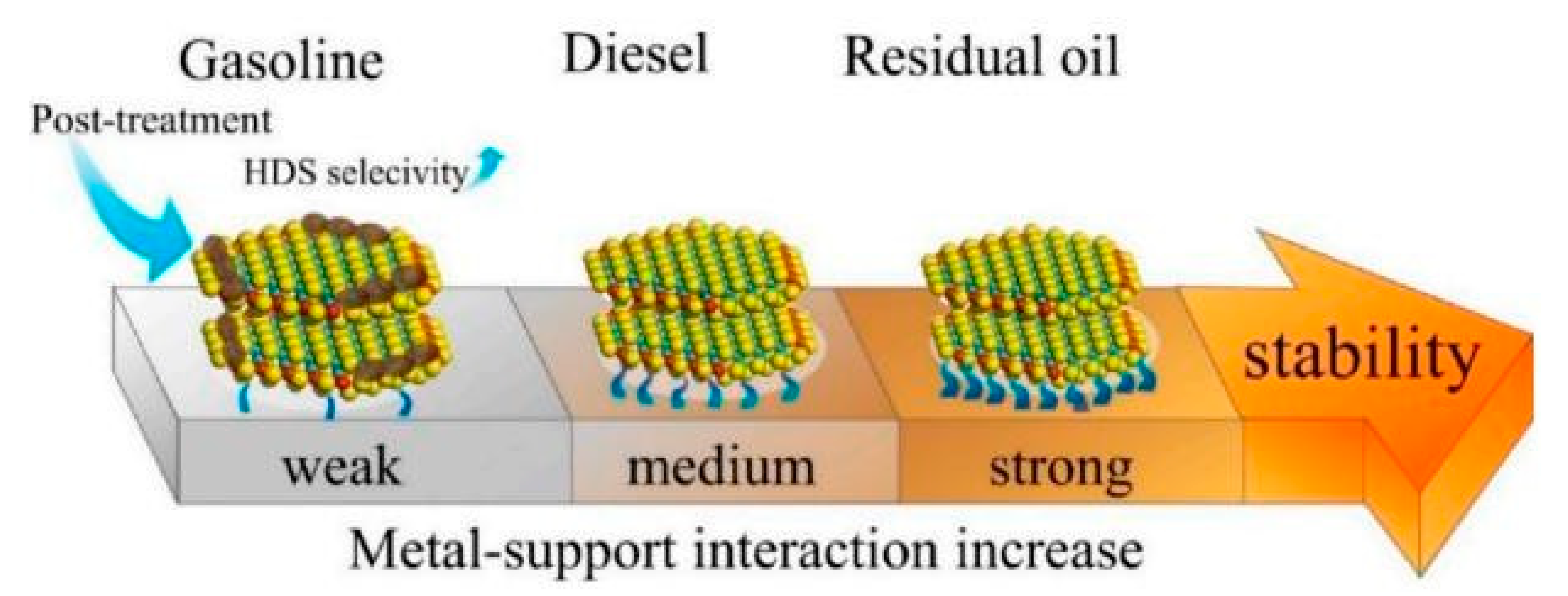

4.2. Supported Catalysts for HDS: The Role of the Support in Active Sulfide Phases

The nature of the support generally plays a key role in the morphology, dispersion, and, obviously, in the catalytic activity of the prepared catalysts (Che, M.S., et al., 2006). Furthermore, it is well known that conventional alumina is not a completely inert carrier under reaction conditions and could allow the migration of active promoters, such as Ni or Co, to its outermost surface, forming subsurface spinels (Gutierrez, O.Y., et al., 2014) or promote isomerization reactions depending on the acidic nature of these ions. In previous reports, (Topsøe et al., 2007) recognized that if the interaction between the CoMoS phases and the alumina carrier could be eliminated or at least considerably reduced, the new sulfided structures would have greater intrinsic activity. This led them to propose the existence of a different structure with less support interaction, which they called the CoMoS type II phase. Since then, much research has been conducted attempting to modulate the interaction of the support with the active phases (Shimada, 2003). It is now well accepted that catalysts for different petroleum fractions should exhibit slight differences related to metal support interactions. Therefore, modulation of the dispersion of the active phase on the alumina is the determining factor for activity, selectivity, and stability (

Figure 4.9).

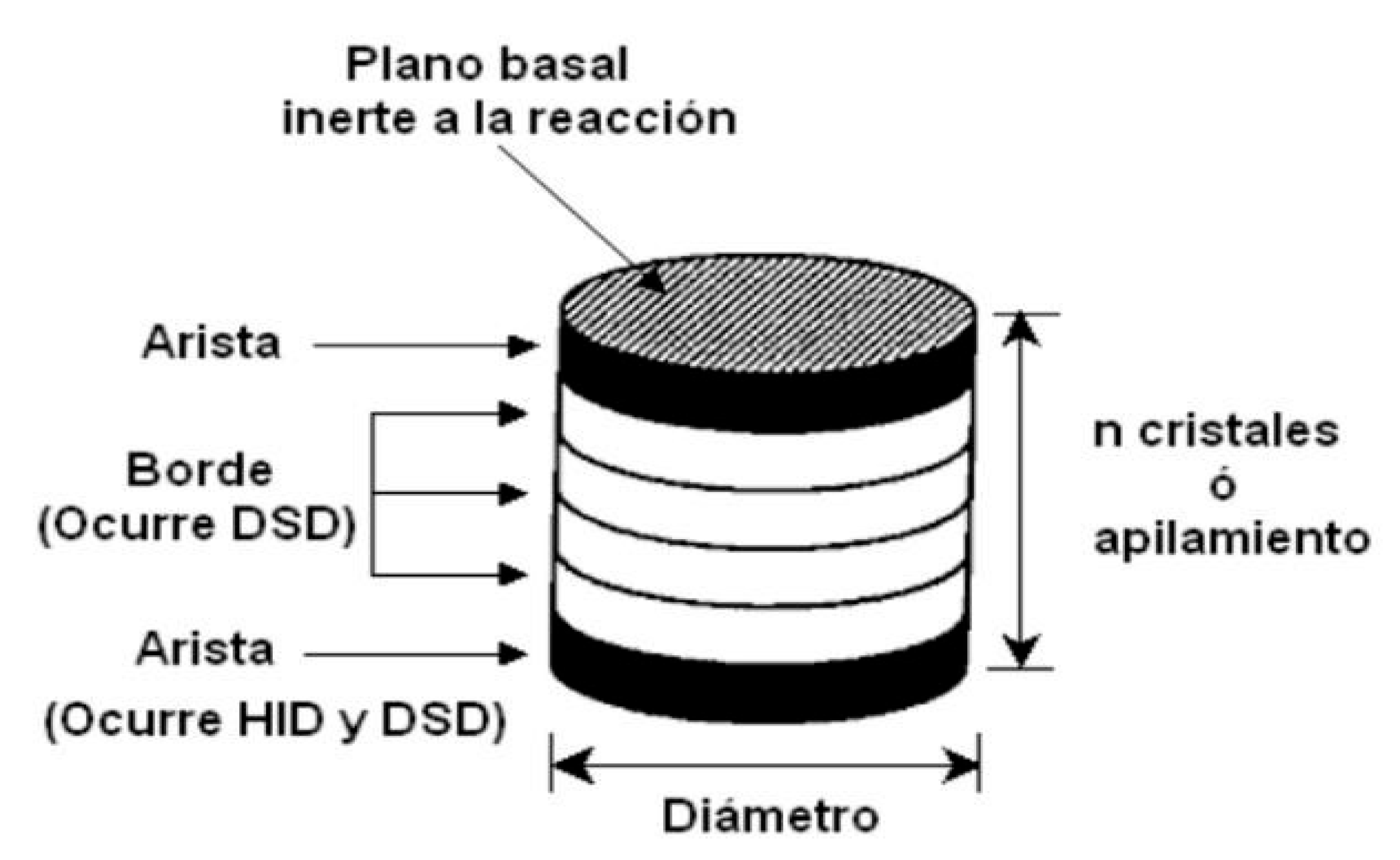

In this regard, there has been extensive research into understanding the effect of the support. The dispersion, average stacking and length of MoS

2 or WS

2 sheets, and the way in which metal sulfides adhere to the support surface are the subject of several investigations (Nihn et al., 2011). Early reports mentioned that the catalytic performance of MoS

2-based catalysts depends largely on their morphology, but also on their orientation, as sheets can be attached by the edge or by the basal planes (Shimada, 2003) depending on the support (

Figure 4.10).

Usually, on gamma-alumina, preferential binding is via the basal (111) and (100) planes since these show relatively weak and intermediate interactions with MoS2 structures as Barat et al., 2016 (Bara., et al., 2016) have recently shown. In contrast, the (110) plane displayed highly dispersed and oriented oxide particles with strong metal-support interactions. Because of this, the authors associated this plane with small, weakly stacked MoS2 sheets and a very low degree of sulfidation.

4.3. Al2O3 Supports

Alumina is one of the most widely used supports in the refining industry due to its surface physicochemical properties, which can be regulated by the degree of dehydration. These properties, in turn, are modified by the calcination temperature. Among aluminas, the gamma phase is very important due to its characteristics: specific surface areas (180 to 320 m2/g), pore volume, pore diameters, among others, which make it suitable for use as a support for active substances in HDT catalysts.

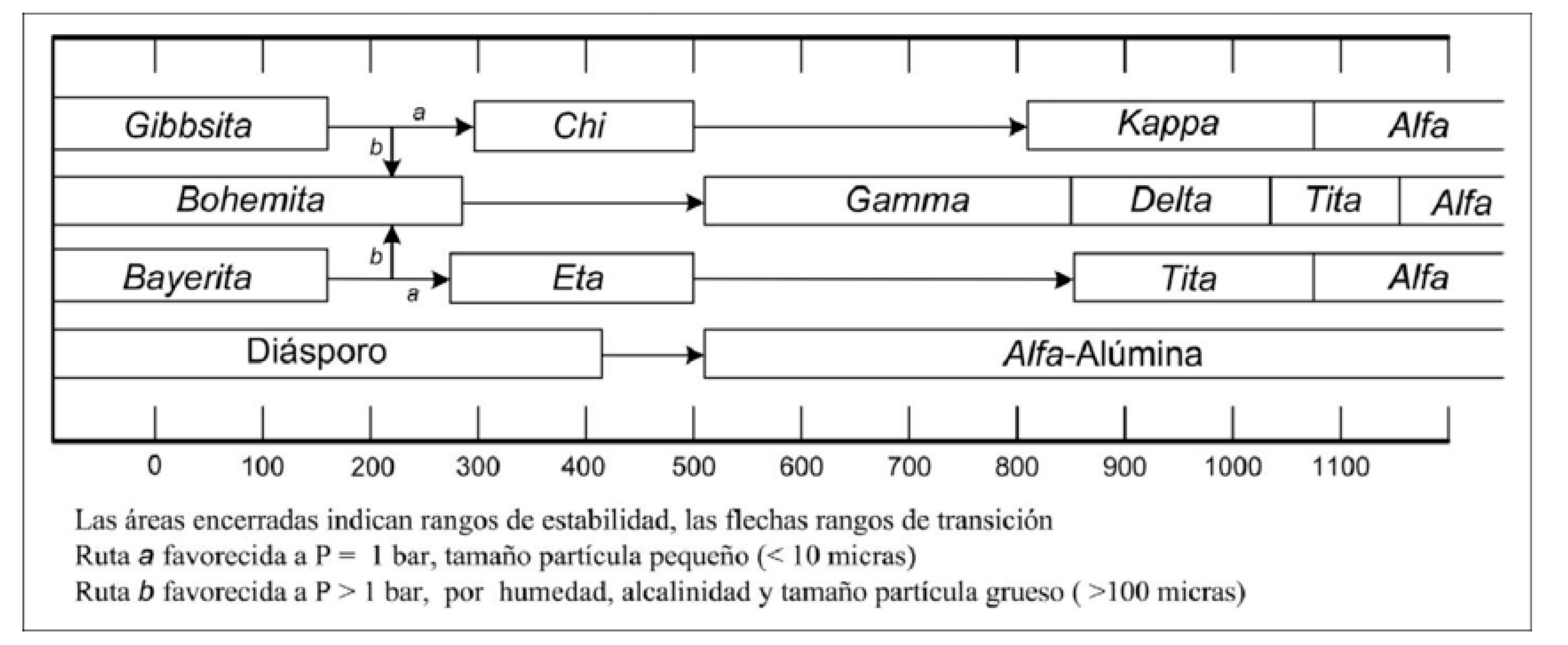

Aluminas are readily found in nature as aluminum hydroxides; these are gibbite (γ-Al2O3.3H2O), boehmite (γ-Al2O3.H2O), and diaspore (β-Al2O3.H2O). Bauxite is composed of the three main aluminum hydroxides. Another phase, although rare in nature, is bayerite (β-Al2O3.3H2O), which is easily prepared by various methods with other aluminum compounds (Chagas, L. H.; et al., 2014).

The dehydration of aluminum hydroxides produces a series of transition aluminas known as oxides with diverse properties and applications depending on the remaining hydroxyl (OH) groups in the structure. The dehydration achieved by heat treatment of aluminas is irreversible; complete dehydration of aluminum hydroxides (T>1373o K) results in the most stable known phase: crystalline α-Al2O3 with very low specific areas of 1 to 5 m2/g. The phase is thermally stable from absolute zero to its melting point (2273 K) (H. J. Eding et al., 1962).

Figure 4.11 schematizes the alumina phases obtained by dehydration with heating in the presence of air. The phase transition depends on the starting material, its crystallinity, the heating rate, and impurities (Gitzen, 1970). In this way, aluminas with very specific characteristics can be obtained; for example, to obtain aluminas with large crystal sizes (100 µm), route b can be followed, which is favored by humidity and alkalinity. Route a produces aluminas with very small crystal sizes (less than 10 µm). The alumina phase used for the support preparation was gamma alumina (γ-Al

2O

3), because it calcines at temperatures of 773° K. Therefore, it is most likely a material that initiates the phase change (boehmite to gamma), which is why it is believed to have small crystals on its surface. The dehydration or elimination of hydroxyl groups causes the formation of cavities or holes that give this material a high specific surface area (180 to 500 m

2/g), making it very useful for dispersing catalytic substances, lowering the cost of metals (or active phases) that require maximum dispersion over the support surface.

4.4. Structure of γ-Al2O3

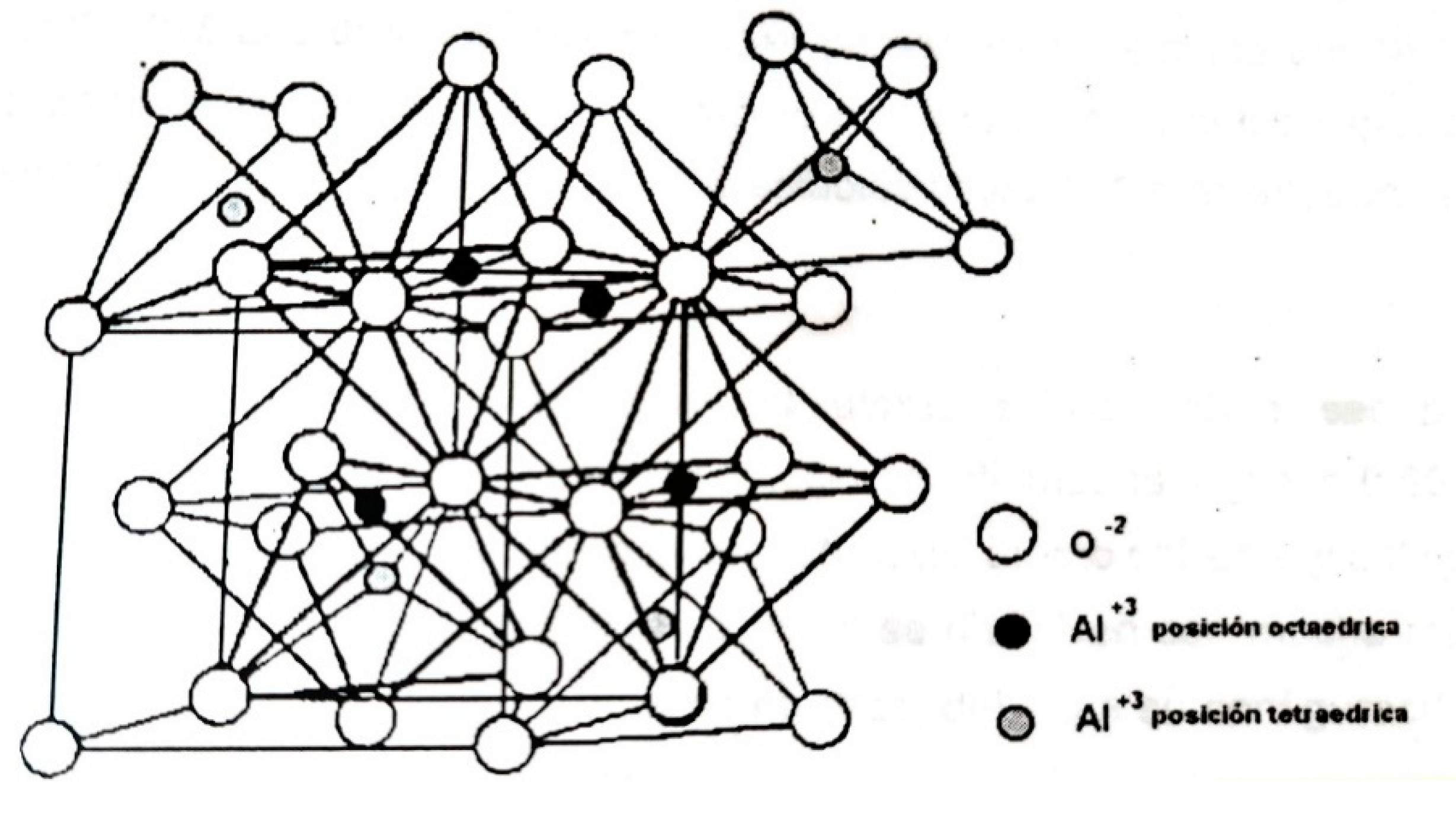

According to the literature, this phase of alumina exhibits a characteristic structure called a spinel (or spinel defect). Many binary or ternary oxides frequently used in catalysis crystallize in structures like this.

Figure 4.12 shows the spinel structure, which presents more or less tightly packed cells of oxygen ions and aluminum ions (Al

3+) in octahedral and tetrahedral positions, and which differ sequentially with superimposed oxygen-packed layers (Haber, 1981). In this figure, tetrahedra and octahedra are observed where some oxygen atoms are shared between these tetrahedra and octahedra that make up the cell. There are many ways in which spinel defects can form in the structure, depending on the cation vacancies in the cell in tetrahedra and octahedra. In the structure, only 1/8 of the tetrahedral sites and 1/2 of the octahedral sites are occupied, so the solubility of cations in the spinel structure is apparently due to the occupation of cations in the interstices of tetrahedra and octahedra or their substitution by atoms of the structure (unit cell). Many other cations can be occluded in the interstitial vacancies depending on their properties or characteristics, both physical and chemical; atomic size, valences, electronegativity, etc. Consequently, many multicomponent systems can be obtained, regulating their properties by the addition of suitable cations and their appropriate composition, since they are believed to have an influence on the catalytic activity of these oxides (binary or ternary).

4.5. Incorporation of Ions into γ-Al2O3

Currently, catalysts are being developed that are capable of maintaining their catalytic properties (activity, selectivity, and stability) for longer periods of time and targeting a specific reaction. For example, in the case of CoMo/γ-Al2O3 catalysts in the sulfide state (Bataille, 2000), the goal is to maintain high hydrodesulfurization activity and controlled hydrogenation by controlling the catalyst's acidic properties (number and type of acid or base sites) through the incorporation of certain metal ions, alkaline, alkaline earth, and even some rare earths, especially those from the lanthanide series (Lewandowsky, 2003).

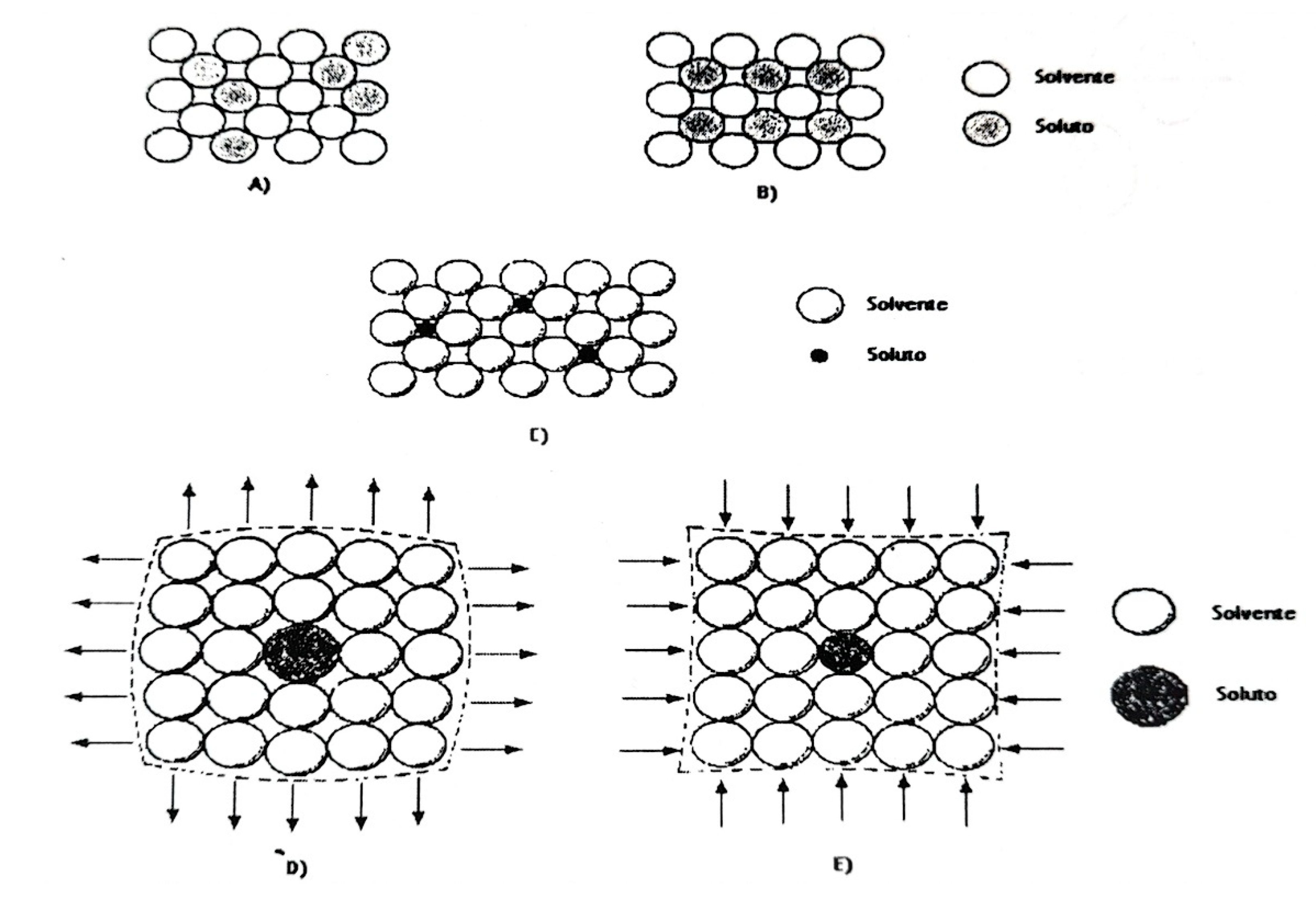

The addition of ions to the catalyst support aims to modify the surface physicochemical properties (acidity and number of acid sites), textural properties (pore volume, pore diameter, surface area, etc.), and thermal and mechanical properties of the catalyst. The interaction of these modifying ions with the support is analyzed using the atomic properties of these ions and the Hume-Rothery rules for solid solutions. These rules typically conform to two models: substitutional solid solution or interstitial solid solution. On the other hand, the Hume-Rothery rules are not absolute, but they can serve as a guide to the factors that favor broad solid solubility. These factors are as follows:

Solid substitution solution

Atomic size: The relative difference between the atomic diameters of the two species must be less than 15%, otherwise, solubility is very limited.

Crystal structure: The solvent and solute atoms must crystallize in the same structure, e.g., face-centered cubic, hexagonal, etc.

Valence: The solute and solvent atoms must have the same valency.

Reactivity: The two species must be chemically similar and must be close in the electrochemical series. Chemical reactions between species tend to favor the formation of stable compounds before forming solid solutions.

Interstitial solid solution

Atomic size: The diameters of the solute atom must be small compared to the solvent atom (diameter ratio less than 0.59).

Crystal structure: The structure of the solvent and solute atoms does not matter.

Solubility in metals: Solute atoms dissolve much more easily in transition metals than in other metals due to their electron configuration (d and f orbitals, electron-free).

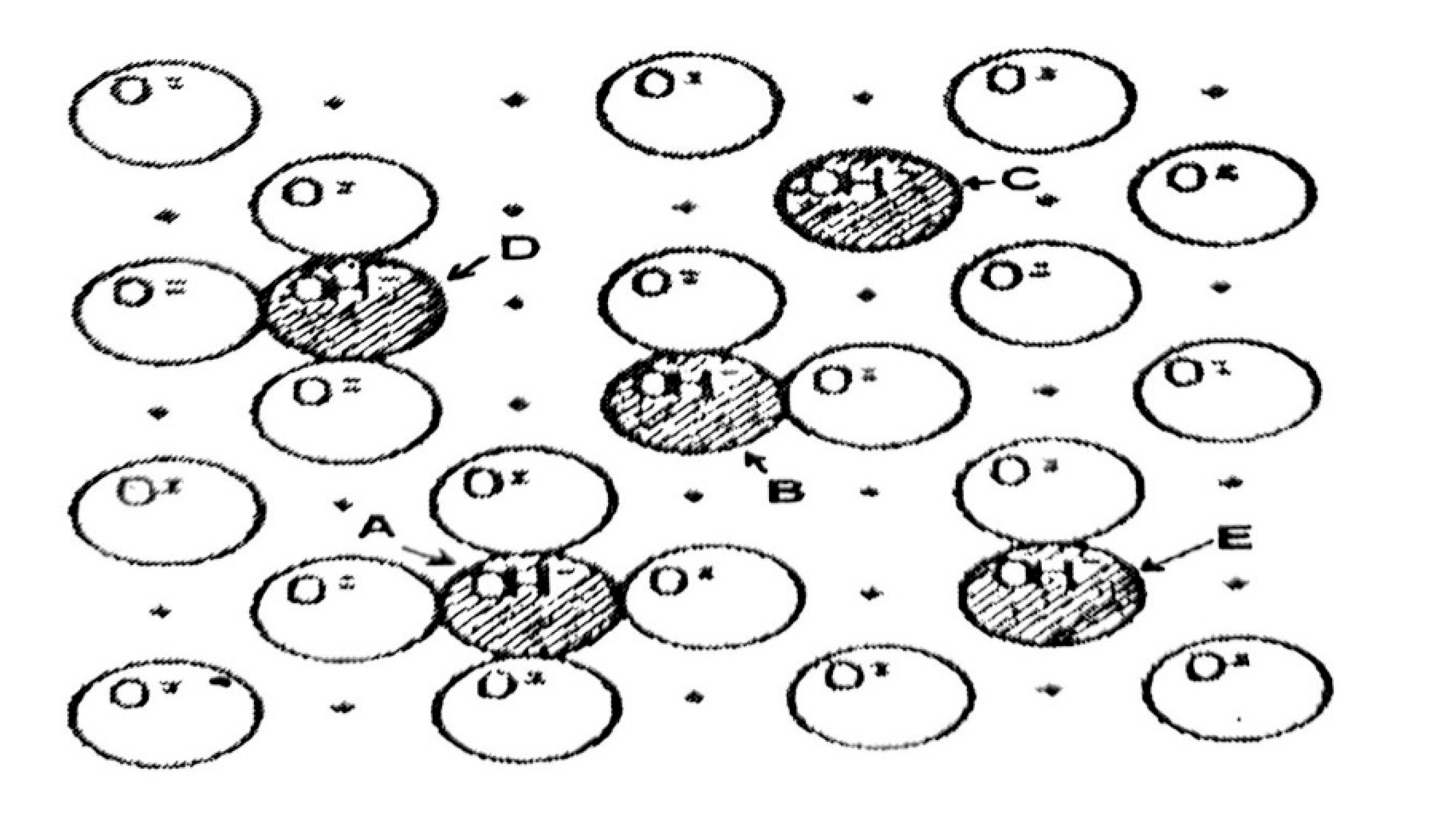

The possible arrangements of ions and the effects produced by solute atoms on the structural lattice are shown in

Figure 4.13.

4.6. Acidity of the Alumina-Based Support

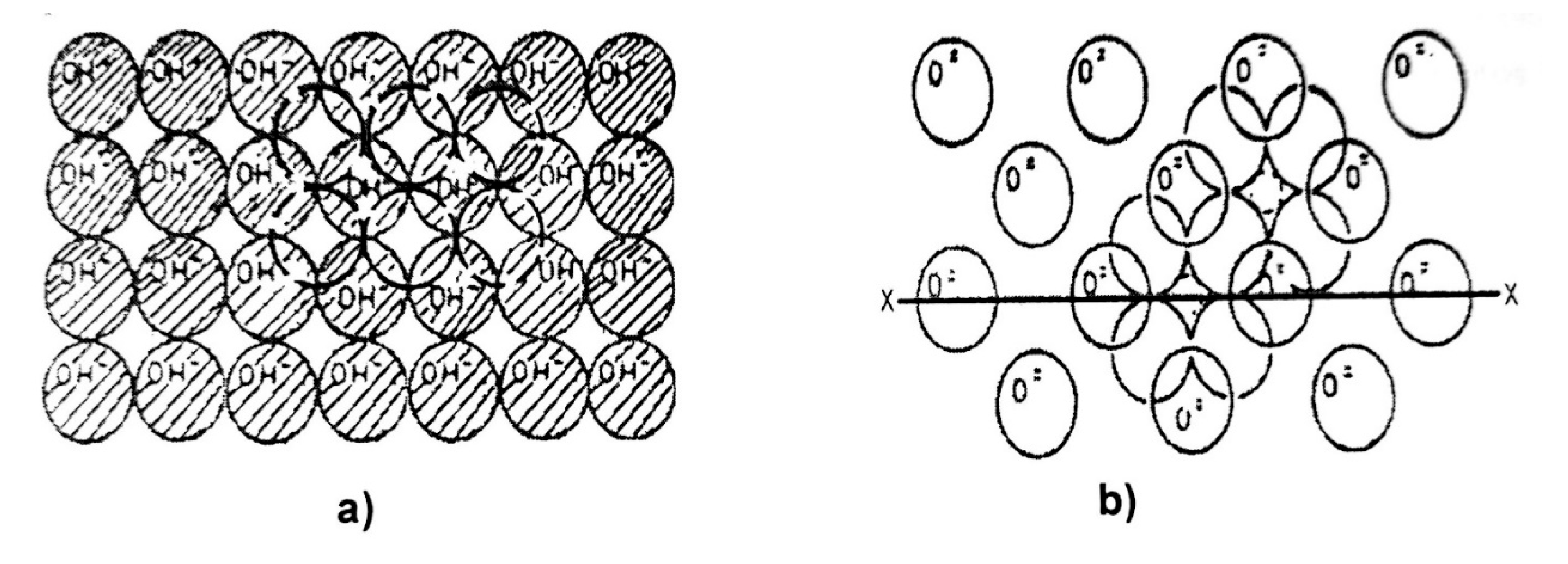

Alumina is characterized by naturally containing essential water in its structure (OH groups) and by hydration during synthesis processes. When hydrated, it forms a monolayer of OH

-1 ions (

Figure 4.14a), which are responsible for its physicochemical properties, especially the acidity of the support. During calcination, adjacent hydroxyl ions (OH

-1) combine randomly to form a water molecule (evacuated by temperature) and an oxygen ion (O

-2), reducing the presence of acid sites. Complete calcination of alumina results in a structure free of OH

-1 groups, as shown in

Figure 4.14b. The hydroxyl groups (OH) remaining from calcination and the release of water cause some disorder in the alumina structure. which presents different types of sites depending on the OH groups present and the nearby O

2- ions.

Figure 4.15 schematically shows the probable sites of the OH

-1 groups remaining after calcination, which are responsible for the acidity of the support.

The random distribution of these sites throughout the alumina matrix results in surface heterogeneity, with up to five types of sites with four or no oxide ions nearby, as shown in

Figure 4.15. In this figure, the sites marked A are the most basic, due to an excess of electrons; while the most acidic sites are marked C, as they have a deficiency of electrons compared to the site marked A. Sites B, D, and E represent sites of intermediate acidity or basicity (Haber, 1981).

4.7. Catalysts Supported on SBA-15

In 1998, Zhao D. et al. synthesized a mesoporous material called SBA-15 in an acidic medium, producing a two-dimensional hexagonally ordered material. The result was a structure with large tunable pore sizes greater than 300 Å, obtained through the use of amphiphilic copolymer blocks.

In 2007, Gutiérrez O. et al. prepared a series of Mo and NiMo catalysts supported on SBA-15 modified with different ZrO loadings using the chemical grafting method, with the aim of studying the effect of ZrO on the hydrodesulfurization of 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene. The results showed that the incorporation of ZrO led to improved dispersion of the Mo species and improved the catalyst activity. The addition of Ni also improved the dispersion of Mo species and led to a tendency toward the direct hydrodesulfurization route.

In 2008, Escobar, J. et al., used EDTA and citric acid as chelating agents during the preparation of NiMo catalysts supported on TiO2-ZrO2 mixed oxides. A clear benefit of the chelating agent was evident when the sulfided catalysts were tested in dibenzothiophene, concluding that the concentration of EDTA and citric acid to maximize activity was different for each (Ni/EDTA = 1 and Ni/citric acid 1:2). These molar ratios appear to correspond to complete nickel impregnation.

In 2008, Gutiérrez, O. et al., synthesized NiMo catalysts supported on ZrO2-SBA-15 by varying the Mo loading, and tested them in a deep hydrodesulfurization reaction (4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene). The results showed that the addition of ZrO improved the dispersion of the metals. In terms of activity, the catalysts showed an increase of almost double the activity obtained with a reference NiMo/γ-AlO catalyst. It was also concluded that the optimal metal loading was 18% MoO and 4.5% NiO.

Alumina-supported Co(Ni)Mo(W) catalysts are typically used in HDS reactions [LU WANG, YONGNA ZHANG, ET AL., 2009]. The use of alumina supports is due to their remarkable mechanical and textural properties and relatively low cost.

In 2010, Klimova, T. et al., conducted a study comparing the benefits of adding TiO2 and ZrO2 in SBA-15, instead of using pure supports of these oxides and γ-alumina in catalysts for hydrodesulfurization. The materials were tested in the hydrodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene. The results showed that the catalysts supported on TiO2-SBA-15 and ZrO2-SBA-15 had higher activity than the other materials, including the reference γ-alumina catalyst.

In 2013, Chandra, K., et al., prepared a series of NiMo catalysts supported on SBA-15, doping the support with Ti or Zr, and studied the effect of the heteroatom on the catalyst. The catalysts were tested in HDS and HDN reactions. The results showed that the catalysts doped with only one element, either Zr or Ti, achieved better activity than the catalyst doped with both elements and the undoped material.

The development of desulfurization processes has been reported using solvents, zeolites, and catalytic methods (Alvarez & Ancheyta, 2008; Babich & Moulijn, 2003; Huirache-Acuña et al., 2014), the latter being the main driver of catalytic hydrotreatment (Liu et al., 2007), with transition metal formulations such as molybdenum (Mo), tungsten (W), cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), and iron (Fe), which exhibit high activity compared to other elements.

In 2014, Peña, L., et al., developed a series of CoMo catalysts supported on SBA-15 prepared with citric acid and EDTA as chelating agents, with MoO3 loadings of 6.12 and 18% by weight. Catalysts prepared without chelating agents showed a crystalline phase (β-CoMoO4) with the lowest metal loading detected by XRD. The addition of chelating agents to the impregnation solution prevented the precipitation of this crystalline phase on the SBA-15 surface. Catalytic activity showed a significant improvement when the metal species were impregnated in the presence of EDTA or citric acid.

Several methods have been developed to prepare more active phases. In this context, improving the degree of dispersion of the active phases is of great importance to increase the activity of HDS catalysts.

In 2016, Viera, A., et al., prepared a series of NiMo catalysts supported on Ti- and Zr-modified SiO2 using the hydrothermal and sol-gel methods, and these were tested in thiophene hydrodesulfurization. The results showed that the Zr-modified catalysts were more active in thiophene hydrodesulfurization than the Ti-modified catalysts, due to the fact that Ti interacts more strongly with Mo and does not allow for good dispersion and formation of the MoS2 species. Furthermore, it was found that the sol-gel preparation method is faster than the traditional method, leading to a reduction in catalyst manufacturing costs.

On the other hand, it is well known that the presence of nitrogen-containing compounds such as carbazole and quinoline inhibit deep HDS reactions due to the competitive adsorption of sulfur and nitrogen compounds onto the catalyst's active sites (T.A. Zepeda, et al., 2016).

In 2017, Zelenak, V., et al., prepared a series of mesoporous silica materials doped with metal ions (Al, Ti, Zr) and tested them for the adsorption of methane and carbon dioxide. It was observed that doping the SBA-15 support with metals improved carbon dioxide adsorption compared to the pure SBA-15 reference material, due to greater interaction with metal cations on the material surface.

Later, in 2021, Fouad K. Mahd et al. reported the effect on catalytic activity of inserting tungsten metal (W) into trimetallic W-Mo-Co supported on gamma-alumina (γ-AlO) as a heterogeneous catalyst for hydrodesulfurization (HDS) in an oil refinery. A bimetallic Co5Mo15/γ-Al2O3 catalyst and a trimetallic Co5Mo14W1/γ-Al2O3 catalyst were synthesized using incipient moisture impregnation. The synthesized trimetallic Co5Mo14W1/γ-Al2O3 catalyst exhibited improved catalytic performance, with 88% sulfur hydroremoval percentage based on a petroleum naphtha HDS reaction compared to 82% for the bimetallic Co5-15Mo/γ-Al2O3 catalyst under the same operating conditions at a pressure of 11.5 bar, a temperature of 598o K, and a reaction time of 3 h. This enhanced catalytic activity can be attributed to the presence of tungsten increasing the number of metallic sites on the reaction surface of the catalyst.

4.8. Deactivation of HDT Catalysts

The loss of efficiency becomes apparent during operation, as the rate of hydrotreating reactions decreases over time. In practice within a refinery, this reduction in activity is counteracted by raising the temperature (Meena Marafi et al. 2010). Therefore, efforts are being made to develop more efficient and stable catalysts to minimize activity loss. This reduces catalyst usage and the need to regenerate spent catalysts. Deactivation assessment depends on multiple factors, including feedstock characteristics, operating conditions, and catalyst configuration, among others. It is important to note that there is a significant difference in catalyst deactivation in the hydrotreating of heavy versus light materials; in the case of heavy catalysts, the process is more complicated.

Most catalysts cannot maintain constant efficiency throughout their entire service life. These catalysts are prone to deactivation, which means their performance decreases over time.

Catalyst deactivation is a key element in the planning and operation of catalytic processes. As indicated in

Table 4.3 (Dufresne P., 2007), in hydrotreating, the three main reasons for deactivation are: plugging of the porous structure due to the accumulation of coke or metal sulfides (also known as fouling), which occurs during the first few days of operation; as well as sintering of the active phase and distribution, where the deactivation rate varies depending on process conditions, the feed, the catalyst itself, and the deactivation mechanism; and poisoning of the catalyst's active sites by the strong adsorption of molecules such as nitrogen compounds or coke.

The end of the useful life of HDS catalysts is generally determined by the degree of activity that meets product requirements, but it can also be caused by a malfunction in the unit (such as a pressure increase, compressor failure, or lack of hydrogen), or by a scheduled plant shutdown. Therefore, some catalysts are not considered spent when they are removed from the reactor and are sent for regeneration, while others reach their limit, meaning they experience high temperatures at the end of their cycle, thus accumulating a considerable amount of coke. For this reason, the percentage of coke in used HDS catalysts varies significantly, ranging from 5 to 25% by weight, with the average in diesel units being between 10 and 15% by weight. Catalyst life cycles in atmospheric oil processing systems (ULSD) or vacuum gas oils are between 1 and 2 years, for waste treatment plants it is 0.5 to 1 year, and for naphtha hydrotreating it can extend to 5 years or more.

4.9. Catalytic Reactivation

Meena Marafi et al. (2010) define catalytic reactivation as the method of removing accumulated coke from the catalyst surface in order to restore its initial catalytic activity to its maximum potential, recovering both the active surface and porosity. Generally, for effective regeneration, the level of metallic contaminants (Ni and V) in the catalyst used must be less than 5% by weight. Otherwise, at least 80% of the original activity recovery cannot be achieved during the reactivation process. This level of catalyst activity recovery is easy to achieve with catalysts used in the hydrotreating of light atmospheric distillates. Achieving this level of recovery is complicated when the catalyst surface contains both coke and metals deposited from the feedstock. The procedure that restores activity by removing coke and metals is called catalyst rejuvenation.

4.10. Ex-situ Reactivation

The most commonly used method for activity recovery is coke removal through an oxidative regeneration process using diluted air or a combination of air and steam at temperatures of 400–500°C. Other oxidizing agents can also be used, with ex-situ regeneration being the most effective, as it is carried out outside the reactor, thus preventing corrosion problems. This oxidative regeneration method has been in commercial use for several decades. Additionally, steam and carbon dioxide (CO2) are used as oxidants. Some researchers, such as Meena Marafi et al. (2010), indicate that this technique can produce highly active catalysts, achieving 94% recovery in HDS activity and 89% recovery in specific area. Another available method is coke removal through reductive regeneration using H2. However, this procedure has not yet been developed commercially.

Most catalyst revitalization methods employing non-oxidative approaches focus on the selective leaching of contaminating metals from catalysts that have lost effectiveness, using organic acids.

4.11. In-situ Reactivation

In-situ reactivation is carried out within the reactor, or in-situ, to remove buildup on the catalyst surface through the use of various solvents. However, the effect of this alternative is limited, so after heating to obtain the necessary mechanical strength and removing the solvent from the catalyst, greater dispersion of the active metals is achieved through the use of chelating agents (compounds that form complexes with heavy metal ions). This same method is also applied to regenerated catalysts.

4.12. Industrial Regeneration

In the early 1970s, most refineries regenerated their catalysts on-site, using fixed-bed reactors. This process requires the provision of air and contact systems to incinerate the coke from the spent catalyst, as well as scrubbing facilities to prevent environmental problems related to the emission of the gas generated during regeneration, which includes sulfur, nitrogen, and carbon oxides. Both temperature and oxygen concentration are monitored during coke combustion to prevent sintering of the active phase and its loss due to reactions with the support. Hot spots and temperature variations occur during the in situ regeneration process. Furthermore, catalyst fines remaining in the bed can cause reactor fouling and poor reactor distribution upon restart. Currently, more than 90% of refineries opt for off-site hydrotreating catalyst regeneration services.

Off-site hydrotreating catalyst regeneration processes achieve improved activity recovery thanks to rigorous temperature control during regeneration, more accurate evaluation for catalyst reuse through characterization, and quality control testing to remove fines and chips that can cause pressure drop issues. Globally, three main companies offer this off-site regeneration service: Eurecat, Porocel, and Tricat, each employing their own technology, including a rotary kiln, a belt kiln, and a fluidized bed kiln, respectively.

4.13. Spent Catalysts and Management Alternatives

Furimsky et al. (1999) reviewed research on the environmental management, disposal, and utilization of spent catalysts in refineries. Refineries have several alternatives, such as reducing the production of spent catalyst recycling waste through metal recovery and treating discarded catalysts for safe disposal and reintegration to manufacture new catalyst and other valuable materials.

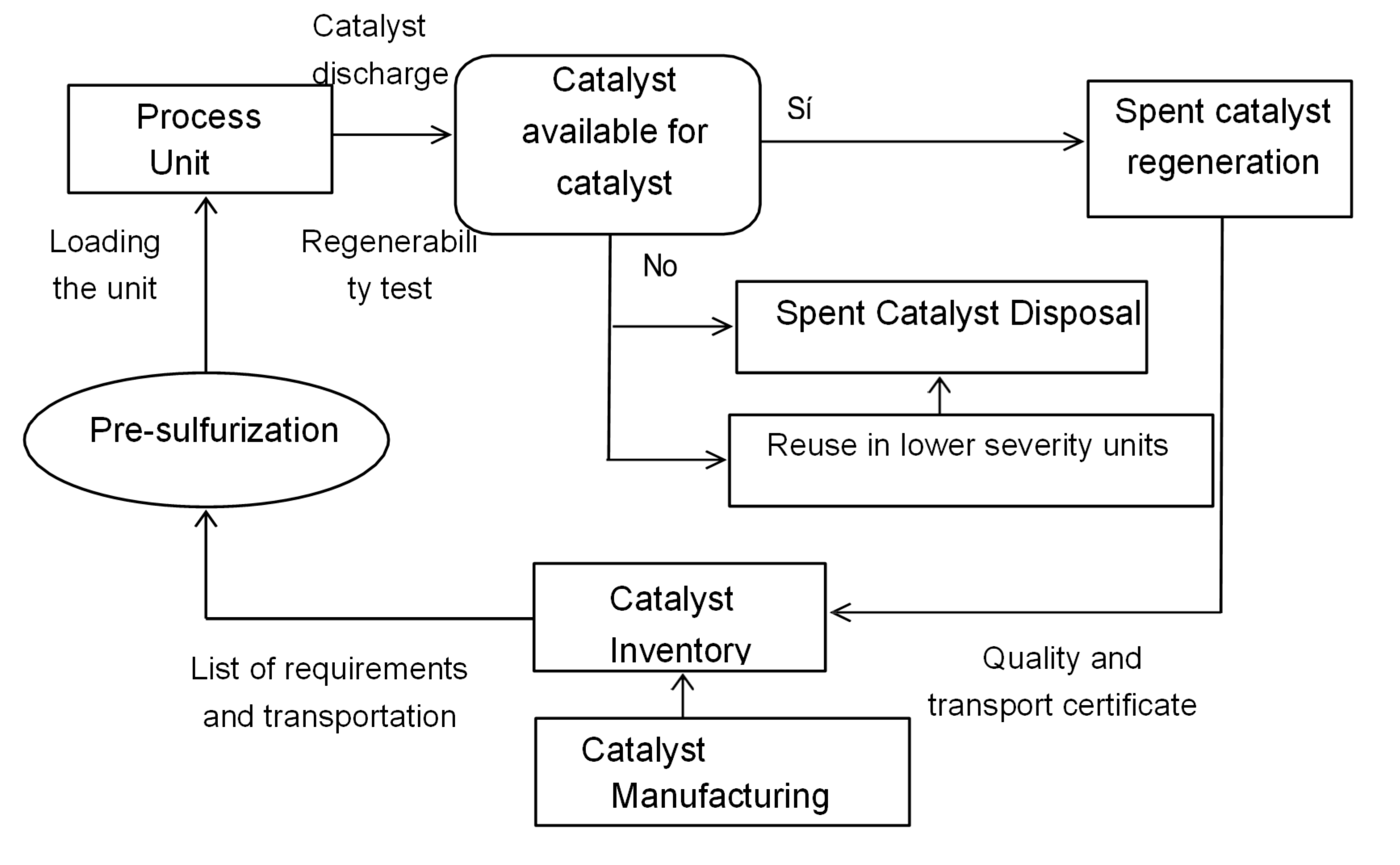

Catalysts play a role in various processes and have specific life cycles that allow them to be used effectively for various purposes.

Figure 4.16 shows a simplified diagram of a catalyst's life cycle, which begins with its production and storage. Depending on the process needs, it is transported to the industrial plant and introduced into appropriate reactors. It is then activated through a presulfurization process, which involves converting the metal oxides into their sulfide form (active phase) using sulfurizing agents containing sulfur, such as hydrogen sulfide (H

2S). Occasionally, the catalyst is presulfurized outside the reactor.

Once the industrial plant has been in operation for a certain period of time, the catalyst is removed and a decision is made whether it is regenerated or stored in the catalyst inventory for later use in the same process or in other less intensive processes, or whether it is disposed of as industrial waste. Catalysts used in hydrotreating are based on γ-alumina and generally include molybdenum or tungsten oxides combined with nickel or cobalt oxides. Catalysts used for hydrotreating heavy petroleum fractions lose effectiveness due to the accumulation of coke and metals on their surfaces, substances that are inherent to the nature of the hydrocarbons they process (Absi-Halabi M., Stanislaus A. & Trimm D. L., 1991). These catalysts undergo rapid initial deactivation by coke formation. Over time, coke formation decreases, but the catalyst continues to deactivate, mainly due to the accumulation of metals on its surface. At the end of the process, this catalyst is called spent catalyst (Furimsky E., et al., 1999).

Spent catalysts can contain between 5% and 25% by weight of carbon (sometimes even more) and sulfur. The amount of accumulated metals depends largely on the concentration of metals such as vanadium and nickel in the mixture. Other common contaminants include iron, from the corrosion of tanks, pipes, and heat exchangers, as well as silica, resulting from the decomposition of antifoam additives, among others.

Furthermore, although catalyst recycling and regeneration capacities are likely to increase, the demand for new catalyst will not decrease due to the increase in its use, driven by stricter regulations on pollutant emissions. Large quantities of these catalysts are required in the hydrotreating process of heavy fractions, resulting in the accumulation of high inventories of spent catalysts. These catalysts are a significant source for metal recovery, generating both economic and environmental benefits.

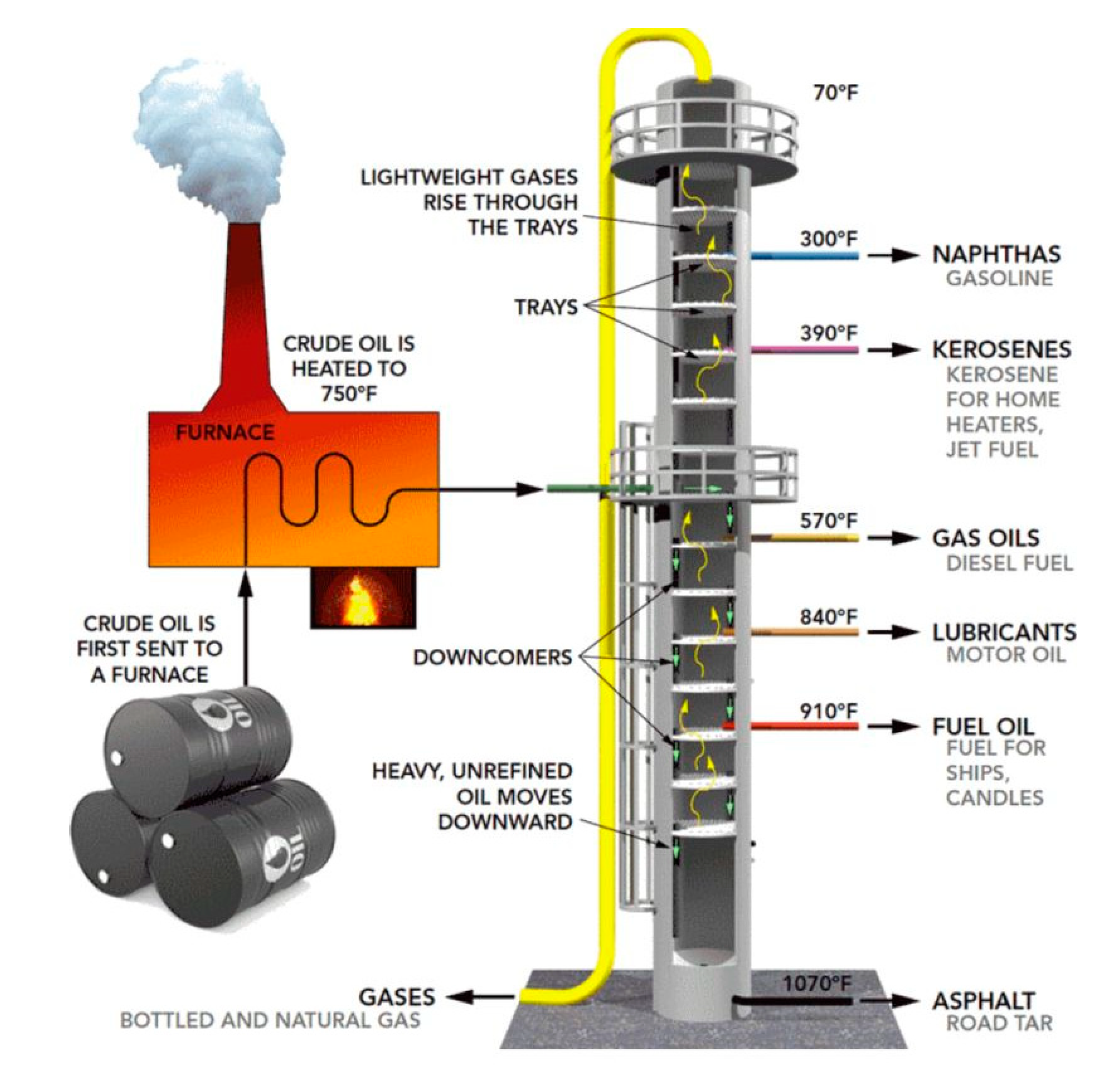

Figure 2.1.

Fractionation tower (Taken from Climent Olmedo, María José. 2021).

Figure 2.1.

Fractionation tower (Taken from Climent Olmedo, María José. 2021).

Figure 3.2.

Permitted sulfur levels in diesel worldwide (Petroleum Products Outlook 2010-2025, SENER).

Figure 3.2.

Permitted sulfur levels in diesel worldwide (Petroleum Products Outlook 2010-2025, SENER).

Figure 3.3.

(Taken and modified from P. Scherer et al., 2009).

Figure 3.3.

(Taken and modified from P. Scherer et al., 2009).

Figure 3.4.

Proposed reaction pathways for DBT HDS, numbers shown correspond to pseudo-first order rate constants at 300°C in [L/(g of catalyst] (Taken from M. Houalla. et al. 1980).

Figure 3.4.

Proposed reaction pathways for DBT HDS, numbers shown correspond to pseudo-first order rate constants at 300°C in [L/(g of catalyst] (Taken from M. Houalla. et al. 1980).

Figure 3.5.

Nitrogen-containing compounds present in petroleum (Taken from J.R. Katzer, R. Sivasubramanian, Cut. Rev.- ai. Eng. 20, 1979).

Figure 3.5.

Nitrogen-containing compounds present in petroleum (Taken from J.R. Katzer, R. Sivasubramanian, Cut. Rev.- ai. Eng. 20, 1979).

Figure 3.6.

Nitrogen compounds in fossil fuels. (From A.R. Katritzky, “Handbook of Heterocyclic Chemistry,” Pergamon Press, 2010).

Figure 3.6.

Nitrogen compounds in fossil fuels. (From A.R. Katritzky, “Handbook of Heterocyclic Chemistry,” Pergamon Press, 2010).

Figure 3.7.

Diagram of a Hydrodesulfurization Unit (Stanislaus A. et al, 2010).

Figure 3.7.

Diagram of a Hydrodesulfurization Unit (Stanislaus A. et al, 2010).

Figure 4.8.

Variation of DBT HDS activity for different transition metal sulfides (Taken from Chianelli, et al; 2005).

Figure 4.8.

Variation of DBT HDS activity for different transition metal sulfides (Taken from Chianelli, et al; 2005).

Figure 4.9.

Metal-support interactions in hydrotreating catalysts depending on the intended use by Nie et al., (2018).

Figure 4.9.

Metal-support interactions in hydrotreating catalysts depending on the intended use by Nie et al., (2018).

Figure 4.10.

“Edge-edge” model for unpromoted transition metal sulfides (Taken from Daage, et al 1994).

Figure 4.10.

“Edge-edge” model for unpromoted transition metal sulfides (Taken from Daage, et al 1994).

Figure 4.11.

Phases of alumina, obtained by the dehydration of aluminum hydroxides. (Taken from Gitzen, 1970).

Figure 4.11.

Phases of alumina, obtained by the dehydration of aluminum hydroxides. (Taken from Gitzen, 1970).

Figure 4.12.

Common spinel structure of some complex oxides. (Taken from Haber. J, 1981).

Figure 4.12.

Common spinel structure of some complex oxides. (Taken from Haber. J, 1981).

Figure 4.13.

Schematic diagram illustrating the relative positions of solvent and solute atoms in a solid solution: A) random substitution, B) ordered substitution, C) interstitial. D) compression effect, E) tension effect. [Taken from Bataille, 2000].

Figure 4.13.

Schematic diagram illustrating the relative positions of solvent and solute atoms in a solid solution: A) random substitution, B) ordered substitution, C) interstitial. D) compression effect, E) tension effect. [Taken from Bataille, 2000].

Figure 4.14.

Structure of γ-Al2O3: a) hydrated surface, b) fully calcined or dehydrated surface. [Taken from Haber, 1981].

Figure 4.14.

Structure of γ-Al2O3: a) hydrated surface, b) fully calcined or dehydrated surface. [Taken from Haber, 1981].

Figure 4.15.

Surface model of γ-Al2O3. [Taken from Haber,1981].

Figure 4.15.

Surface model of γ-Al2O3. [Taken from Haber,1981].

Figure 4.16.

Life cycle of a catalyst (Absi-Halabi et al., 1991).

Figure 4.16.

Life cycle of a catalyst (Absi-Halabi et al., 1991).

Table 2.1.

Properties of oil types in Mexico [LÓPEZ-SALINAS ET COL., 2010].

Table 2.1.

Properties of oil types in Mexico [LÓPEZ-SALINAS ET COL., 2010].

| Characteristics |

Maya |

Istmo |

Olmeca |

Altamira |

| API Gravity |

21.3 |

33.1 |

38.7 |

16.5 |

| Elemental analysis (%p) |

|

| Carbon |

83.96 |

85.4 |

85.91 |

84.96 |

| Hydrogen |

1.8 |

12.68 |

12.8 |

1.7 |

| Oxygen |

0.35 |

0.33 |

0.23 |

0.36 |

| Nitrogen |

0.32 |

0.14 |

0.07 |

0.34 |

| Sulfur |

3.57 |

1.45 |

0.99 |

6.0 |

| H/C Ratio |

1.687 |

1.782 |

1.788 |

1.69 |

| Metals (ppm) |

|

| Nickel |

53.4 |

10.2 |

1.6 |

53.9 |

| Vanadium |

298.1 |

52.7 |

8 |

299 |

| Asphaltenes (%p) |

|

| nC5

|

14.1 |

3.63 |

1.05 |

15 |

| nC7

|

11.32 |

3.34 |

0.75 |

12 |

Table 2.2.

Mixtures of hydrocarbons obtained in the distillation of petroleum.

Table 2.2.

Mixtures of hydrocarbons obtained in the distillation of petroleum.

| Fraction |

Number of carbon atoms per molecule |

| Non-condensable gas |

C1-C2

|

| Liquefied gas (LP) |

C3-C4

|

| Gasoline |

C5-C9

|

| Kerosene |

C10-C14

|

| Diesel |

C15-C23

|

| Lubricants and paraffins |

C20-C35

|

| Heavy fuel oil |

C25-C35

|

| Asphalts |

>C39

|

Table 2.3.

Main heteroatom removal processes [CLIMENT, M, 2012].

Table 2.3.

Main heteroatom removal processes [CLIMENT, M, 2012].

| Process |

Function |

| Hydrocracking |

Convert diesel fuel to gasoline and eliminate heterocompounds. |

| Hydrodesulfurization of gasoline |

Eliminate undesirable products such as sulfur and nitrogen from gasoline. |

| Catalytic naphtha hydrodesulfurization |

Reduce sulfur content to below 15 parts per million in gasoline. |

| Hydrodesulfurization of coking and vacuum gas oils |

Reduce the sulfur content in diesel and gas oil products. |

Table 2.4.

Compounds containing sulfur and nitrogen present in petroleum (Taken and modified from P. Scherer et al., 2009).

Table 2.4.

Compounds containing sulfur and nitrogen present in petroleum (Taken and modified from P. Scherer et al., 2009).

Table 4.3.

Main causes of deactivation in hydrotreating catalysts.

Table 4.3.

Main causes of deactivation in hydrotreating catalysts.

| Catalytic process |

Catalyst |

Cause of deactivation |

| |

|

Coke Deposits |

Sintering of the active phase |

Poisoning |

| Diesel hydrodesulfurization |

CoMo- NiMo/Al2O3

|

+++ |

++ |

+ a

|

| Hydrotreatment of waste |

NiMo- CoMo/Al2O3

|

+++ |

+ |

+++ b

|

Table 2.5.

Post-treatment construction in Mexico's refineries.

Table 2.5.

Post-treatment construction in Mexico's refineries.

| REFINERY |

CONSTRUCTION |

| Cadereyta |

A 42,500-barrel-per-day catalytic gasoline desulfurization plant, with an amine regeneration unit, elevated burner, pumping equipment for hydrocarbons and sour water, complementary facilities, and integrations. |

Madero

|

Two catalytic gasoline desulfurization plants with a capacity of 20,000 barrels per day, two amine regeneration units, an elevated burner, pumping equipment for hydrocarbons and bitter waters, complementary facilities, and integrations. |

Minatitlán

|

A 25,000-barrel-per-day catalytic gasoline desulfurization plant, an amine regeneration plant, complementary auxiliary service systems, and their integration into the refinery. |

| Salina Cruz |

Two catalytic gasoline desulfurization plants with a capacity of 25,000 barrels per day, two amine regeneration plants, complementary auxiliary service systems, and their integration into the refinery. |

Tula

|

A 30,000-barrel-per-day catalytic gasoline desulfurization plant, an amine regeneration plant, complementary auxiliary service systems, and their integration into the refinery. |

Salamanca

|

A 25,000-barrel-per-day catalytic gasoline desulfurization plant, an amine regeneration plant, complementary auxiliary service systems, and their integration into the refinery. |

Table 2.4.

Maximum permissible limits of sulfur in fuels, according to the Mexican official standard NOM-086-SEMARNAT-SENER-SCFI-2011.

Table 2.4.

Maximum permissible limits of sulfur in fuels, according to the Mexican official standard NOM-086-SEMARNAT-SENER-SCFI-2011.

| Product |

Sulfur content (ppm S weight) |

| Premium Gasoline |

October 2011: 80 |

MAGNA Gasoline |

January 2011: 500

October 2011: 80

January 2009 30 |

PEMEX DIESEL |

January 2011: 500

January 2011: 15

January 2011: 10 |

| Agricultural and marine diesel |

5000 |

| industrial diesel |

500 |

| Jet fuel |

3000 |

| LP Gas |

140 |

| Domestic Diesel |

500 |