Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women globally, and due to breakthroughs in early detection and treatment, survival rates are improving. Nevertheless, the enduring consequences, such as fatigue, anxiety, depression, and sexual dysfunction, are frequently linked to survival, potentially diminishing overall well-being and quality of life. The stage of cancer is likely to influence the psychological distress encountered by persons with different cancer types and their diverse requirements for supportive care (Y.H. Chou et al.2020) . Likewise, physical, psychological, occupational, social, and sexual issues induce stress in several women confronting the diagnosis and initial treatment phase of breast cancer. Breast cancer survivors exhibit heightened anxiety on the likelihood of cancer recurrence and mortality (B. Thewes et al. 2016). Thus, among breast cancer survivors, post-treatment exercise regimens have too been involved to improve quality of life related to mental well-being, as exercise has been acknowledged for its multifaceted advantages in the physical, psychological, and emotional realms during the survivorship period but despite its well-established benefits, starting and continuing regular physical activity can be extremely tough for many victims due to meantime, lack of confidence and knowledge about the pros of exercise for their cancer outcomes after therapies (A.C. Furmaniak et al. 2016). In this context, the adoption and adherence to exercise among the general population, particularly cancer survivors, have been comprehended and enhanced through numerous psychological theories and motivational tactics (S. Pudkasam et al. 2018). Motivational interviewing (MI) has been effective in facilitating decision-making and diminishing resistance to behavioural change among cancer survivors (F. E. Klonek et al. 2015). Research advocating for corporeal movement among breast cancer fighters has received considerable focus within the oncology sector, owing remarkable projection and consequences (F. Cebral et al. 2011). We intend to discover the emotional (psychological) barriers encountered by survivors of this disease in managing the stress of their condition and participating in physical exercise programs intended to improve their living standard concerning psychological healthiness. To enhance the acceptability and commitment to bodily activities among these individuals, we scrutinize the validity of three psychological theories, one behavioural modification model, and the notion of motivational interviewing (MI).

Figure 1.

Illustrates that breast cancer survivors usually experience lasting consequences.

Figure 1.

Illustrates that breast cancer survivors usually experience lasting consequences.

Methodology

This study employs Medline, PubMed, Google Scholar, and publications predominantly published between 2014 and 2024 to examine research on strength of mind among survivors of breast cancer and the benefits of physical working or exercise plans informed by theories of psychological alterations, concerning the adherence to this program. The major search phrases utilised were breast cancer survivor in relation to psychological health, physical activity, and exercise adherence.

Furthermore, evaluated were reference lists of examined papers for other pertinent sources. Articles not in English were left out, first title and abstracts were checked to find suitable research and afterwards thorough evaluation of complete manuscripts included was done.

Breast Cancer Survivors and Mental Healthiness

Consequently, throughout the changeover from dynamic treatment to follow-up survivorship or maintenance, such patients who fight with breast cancer might face mental health challenges, including body image distortion, sexual dysfunction, fear, sadness, and anxiety concerning their cancer prognosis, along with difficulties related to their employment and familial relationships (Y. H. Chou et al. 2020 and B. Thewes et al. 2016). Due mostly to vasomotor effects (night sweats and hot flashes) and urogenital symptoms (vaginal dryness and decreased libido) following chemotherapy and radiation treatment, younger breast cancer survivors experiencing menopausal symptoms have been reported to have increased mood disturbance compared to older breast cancer survivors (R. J. Santen et al. 2017). These negative effects including changed body image may affect a close relationship with their partner (M. F. Laus et al. 2018). Furthermore, thirty percent of breast cancer survivors say changes in their treatment (from curative to supportive) because they feel abandoned (Y. H. Chou et al. 2020 and F. Williams & S. C. Jeanetta 2016). The current study of breast cancer survivors demonstrates that medical symptoms, treatment side effects (such as fatigue, nausea, discomfort, and difficulties having sex), and marital relationship disruption are all linked to immediate and long-term stressors after diagnosis (D. L. Lovelace et al. 2019). Breast cancer survivors’ levels of stress are likely correlated with their mental health and can cause them to reevaluate their social positions and feel confused about their future (I. Novakov 2024). About one year before diagnosis, over thirty percent of survivors of breast cancer report to have suffered mentally, particularly from sadness and anxiety. Furthermore, one-month post-diagnosis, the incidence of mental illnesses related to stress and mood disorders reaches its zenith in this demographic (R. A. Marrie et al. 2019).

Elements Influencing Psychological Stress and Handling

There is usually a significant association among cancer survivors’ age, gender, education, marital status, kind of cancer, and psychological well-being (E. D. Patsou et al. 2018). Moreover, among breast cancer survivors, psychological disorders like hopelessness (depression), unease (anxiety), diminished devoutness, and reduced sexual gratification are significantly affected by age (D. Wei et al. 2016). According to studies on breast cancer survivors, about half of those under the age of fifty could have depressed symptoms (F. Izci et al. 2016). Younger survivors may encounter greater temperament disturbances and inferior inner adaptation compared to adults, attributable to reproductive concerns and unsatisfactory sexual interactions (M. Maleki et al. 2021). Prolonged recovery from chemotherapy and radiation therapy may mitigate the distressing sensation of concern regarding disease recurrence, notwithstanding the potential positive correlation between neurotic personalities and this fear among breast cancer survivors (R. Micha 2017).

Positive and negative adjustment has been the classification for the coping mechanisms. Fighting spirit that is, seeking social support and information, defines adaptive psychological coping and may help breast cancer survivors to reduce recurrence and extend their survival time (Y. H. Chou et al. 2020 and R. B. Benson et al. 2020. Breast cancer survivors are often characterized by fatalism, indicating a passive acceptance of their condition, or by feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, which can increase their relative risk of mortality (T. V. Merluzzi et al. 2024). Some women who have survived breast cancer say they feel stressed even if they bravely fight their disease (F. Masood and F. Kamran 2023). Still, support from their family is absolutely vital for them to pass the cancer road.

It has been reported that many breast cancer survivors engage in avoidance coping because they may struggle with social limitation, especially when it comes to their loved ones (R. Y. Hu et al. 2021). Consequently, having trouble communicating their feelings about breast cancer exacerbates their mental health, leading to elevated stress, hopelessness, and anxiety (S. Pudkasam et al. 2018). The survivor’s spouse or partner is also impacted by dealing with breast cancer. For example, people could discuss their concerns regarding related cancer problems and collaborate to find solutions (J. J. Mao et al. 2022). To augment mental healthiness and elevate eminence of life and survival rates, health practitioners must evaluate each survivor’s response to cancer and their dealing attitudes (M. Mehrabizadeh et al. 2024).

Figure 2.

Depicts the mental well-being of breast cancer survivors.

Figure 2.

Depicts the mental well-being of breast cancer survivors.

Breast Cancer Survivors and Exercise Adherence

The promotion of physical activity among cancer survivors remains challenging due to many hurdles that hinder acceptance and commitment to cancer rehabilitation programs (S. J. Hardcastle et al. 2018). One of the challenges that breast cancer patients have is a lack of confidence in the advantages of exercise in reducing the risk of long-term breast cancer and the side effects of treatment (J. M. Binkley et al. 2012). According to one study, thirty-two percent of breast cancer survivors stop working out twelve months later. Among the mentioned causes were less education, lack of activity before diagnosis, postmenopausal physical and psychological issues (M. Corbett 2002). Moreover, grownup cancer survivors sometimes mention time difficulties and over-all health problems (S. S. Coughlin et al. 2019).

In the United States, barriers to physical activity among minor female survivors’ groups (American, Hispanic and African) involved fatigue, familial errands, physical limitations, transport matters, employment obligations, and negative perceptions of exercise (M. Seven et al. 2023). Following the completion of a prescribed exercise program, this cancer survivors will probably want supplementary motivation to enhance their exercise adherence (M. Browall et al. 2018). Utilising theoretical models of exercise behaviour may prove beneficial. Theories encompassed are; theory of planned behaviour (TPB), self-determination theory (SDT), trans-theoretical model (TTM), social cognitive theory (SCT) (S. A. H. Friederichs et al. 2016). The execution of exercise lineups based on these concepts has revealed certain adherence paybacks. MI has proven to be an efficient instrument for promoting behavioural change and motivating cancer sufferers to maintain an exercise regimen.

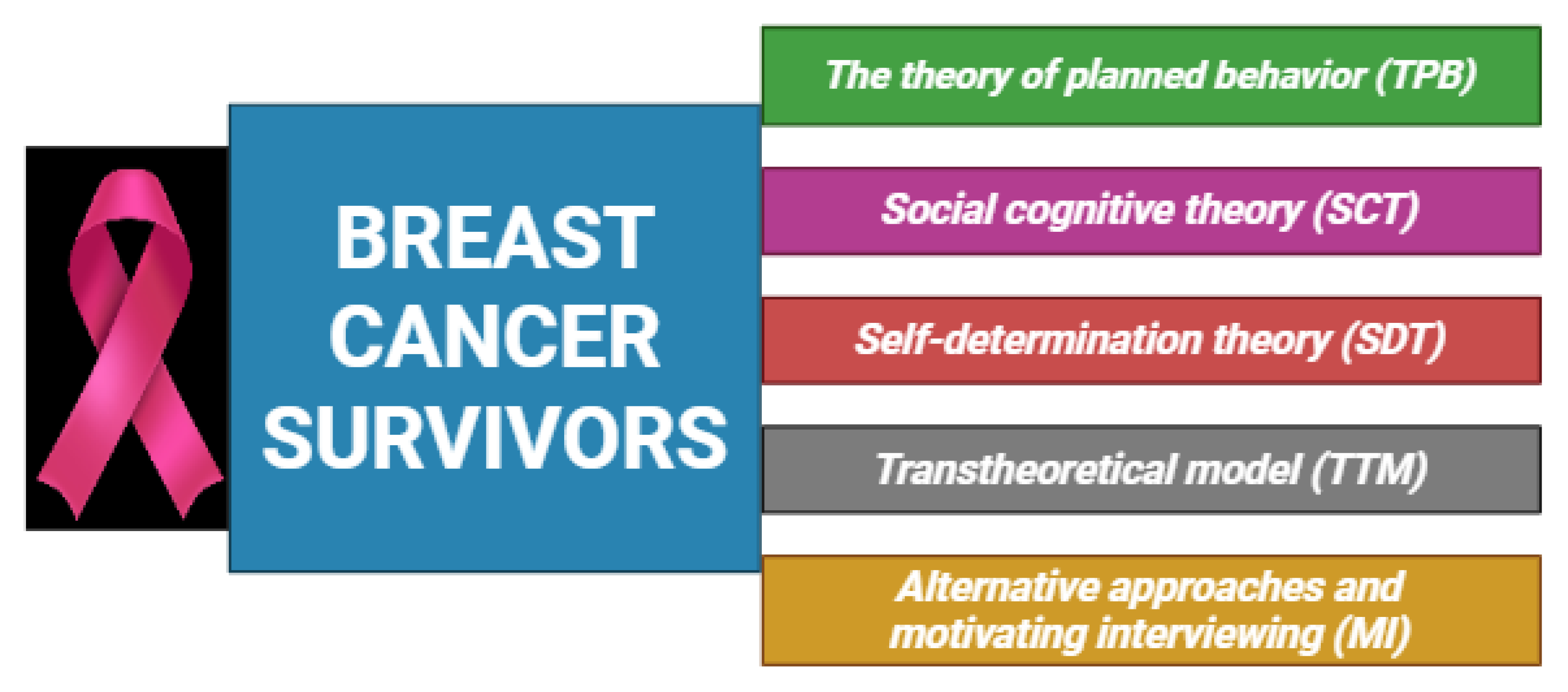

Figure 3.

Shows the adherence to exercise among breast cancer patients.

Figure 3.

Shows the adherence to exercise among breast cancer patients.

Theories of Behavioural Variation Towards Physical Exercise in BCS

Effectiveness and comprehensiveness of all theories employed in the investigation of physical exercise regimens for breast cancer survivors’ post-treatment were assessed (R. Micha 2017). Nevertheless, numerous investigations are not much inclined to adequately examine the perilous determinants of efficiency of program, specifically those influencing the behaviour of breast cancer survivors regarding the use of behavioural change models (M. Perperidi et al. 2023). The researcher is advised to employ Intervention Mapping (IM) to create plans for BCS (S. Kim et al. 2019). IM (a valid evaluative approach and a framework) allows researchers to develop intervention programs grounded in optimal concepts for particular populations (L. Cambon and F. Alla 2021).

Established theories, such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), Self-Determination Theory (SDT), and Transtheoretical Model (TTM), have been employed to inform physical exercise programs for breast cancer survivors. Specifically, TTM and SCT were extensively utilised from 2014 to 2024 (A.C. Furmaniak et al. 2016). Research has shown the advantages of different supervisory methods, including email and telephone counselling, on program efficacy (M. Langarizadeh et al. 2017). The following is a summary of several theories that have been employed to enhance the motivation of breast cancer survivors to engage in and maintain physical activity programs, as well as an analysis of their limitations and usefulness.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

TPB suggests that attitude, subjective norm, and perceived control may help predict an individual’s intention to participate in an activity (M. Altaawallbeh et al. 2015). A person’s attitude is a judgment of their own behavioral performance, whereas the subjective standard is their seeming belief in the principles of behavior. Perceived control is a person’s confidence in their capacity to regulate their behavior (M. S. Ding and S. Budic 2016). According to earlier TPB studies, the main factors influencing exercise participation in a range of cancer patients, especially those who have breast cancer are perceived control and intention to exercise (C. Zhang et al. 2022). While, the other elements, confidence and the help of a significant individual, are probably going to help them to keep on exercising (A. Coull and G. Pugh 2021).

In contrast, a recent meta-analysis examined the deteriorating relationship between intention, attitude, and physical activity behaviour in the context of genuine obstacles, such as an individual’s prior behaviour (M. S. Hagger and K. Hamilton 2024). For instance, past behaviors can reduce the impact of attitude on exercise intention in a similar sense as intention on exercise behavior. Studies on the promotion of physical activity using TPB indicated varied levels of intention and physical activity behavior; the variance is most likely affected by perceived self-efficacy (S. V. Ahmadi et al. 2017). Furthermore, not all research has been favorable to TPB in improving exercise behavior. For instance, an analysis exposed just a modest correlation amid exercise, planning and intention execution after 12 weeks in patients of breast cancer (N. Travier et al. 2015). Therefore, alternative hypotheses should be taken into account in creating intervention plans to encourage women in the several phases of breast cancer to adopt exercise and physical activity programs.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

This theory is grounded in the mutual interaction of personal elements including physical traits, emotions, and social support, human behavior, and its surroundings (G. Freeman and D. Y. Wohn 2017). The idea of self-efficacy is one of the primary determinants of SCT. Studies of self-efficacy have found that exercise behavior is influenced (F. Wang et al. 2022). Professionals should also concentrate on the development of the participants and apply optimistic strengthening (V. Gunaretnam 2021) as a corporeal activity advancement program that provided evidence about social supports and self-efficacy to Hispanic breast cancer survivors via weekly phone calls and newsletters revealed that a higher level of exercise self-efficacy beliefs was associated with physical activity intensity (M. Seven et al. 2023 and V. Gunaretnam 2021).

Through the use of tracking one’s own measures (action monitored by accelerometer) and supervision, an SCT-based activity project for survivors was successfully finished (F. G. Stacey et al. 2015). Despite the fact that a three-month intervention program can enhance self-efficacy and reduce perceived barriers to physical activity, Exercise intensity and theory construct factors (e.g., self-worth, consequence anticipation, perceptual hurdles, and goal planning) do not correlate (M. Karloh et al. 2023). In the same vein, previous studies that have utilised SCT have demonstrated that the physical activity behaviour of breast cancer survivors is minimally influenced by task self-efficacy, social support, and role models (B. Rodrigues et al. 2023). Therefore, future research should investigate the potential of SCT to improve physical activity behaviour and the role of the underlying processes in promoting adoption and adherence among cancer patients, with a particular emphasis on qualitative process assessments (T. V. Merluzzi et al. 2024).

Theory of Self-Determination

The cornerstone of this theory is the assumption that humans are motivated to act when their basic needs such as; autonomy, relatedness, and competence are met. Any behaviour has extrinsic to intrinsic motivation as its basis on a spectrum (L. S. Morris et al. 2022). when people engage in exercise behaviour for extrinsic motivations, such as rewards and/or external demands (such as a health professional’s advice). Conversely, intrinsically motivated behaviour is carried out since the person finds it fun, delightful, or of interest (Y. H. Chou et al. 2020). According to SDT, the goal of treatment should be to get people to exercise for their own reasons. Consequently, behaviours that are motivated by internal motivation are more likely to develop into practices and be sustained over time. A study that employed SDT found that breast cancer survivors who follow physical exercise guidelines achieve higher scores on measures of intrinsic motivation and autonomous control than those who do not (E. V. Carraca et al. 2023). Furthermore, degrees of social support seem to be somewhat closely correlated with motivating orientation (intrinsic vs. extrinsic). It is necessary to have higher degrees of social support leading to six times more intrinsic drive among breast cancer survivors (T. C. Lin et al. 2015). Increased social support for practicing exercise would therefore be wise in future interventions.

Transtheoretical Model OR TTM

Based on this model of behavioural modification, one is probably going to pass through six phases of motivating willingness to modify their health practices which include preliminary contemplation, planning, conduct, upkeep and finality (J. M. Binkley et al. 2012). However, these dynamic phases of behavioural modifications can be either constant or consistent and deteriorating (M. Browall et al. 2018). An intercession can be developed to facilitate the transition in various stages, such as the transition from no intention to willingness, the strategy for making a start to action, or the maintenance of a behaviour to prevent it from changing. This is contingent upon the stage in which individuals find themselves. Therefore, the level of the stage a person is in will probably affect the effectiveness of several intervention ideas and approaches (R. A. Marrie et al. 2019). Depending on their stage of life, participants should get suitable direction on fitness programmes for their decision making (F. E. Klonek et al. 2015). TTM has been demonstrated to enhance self-assurance and diminish negative attitudes towards workout when integrated into a physical exercise program for breast cancer survivors. The intervention program utilised introspection as a recreational reward and delivered lectures and discussions on behaviour change (I. Novakov 2024). The findings indicate that the survivors of breast cancer in the intercession group underwent a more unconventional period of transformation compared to those in standard care group (preparation and action versus activity and maintenance) (T. V. Merluzzi et al. 2024). Furthermore, significantly correlated with the degree of self-efficacy was the stage of altering progression (T. C. Lin et al. 2015). This study, however, failed to establish the correlation between stage of behaviour change and perceived negative impact of exercise (S. J. Hardcastle et al. 2018).

Motivating Interviewing (MI) and Alternative Approaches

Breast cancer survivors demonstrated enhanced fitness behaviors and higher levels of physical activity through a variety of other approaches which encompass assistance from society, interpersonal connections, and participatory techniques (K. Wright 2016). Oversight has been provided for exercise intervention programs for breast cancer survivors as community-based, home-based, and center-based (M. Langarizadeh et al. 2017) however, still other delivery strategies such as; email and phone therapy among them have also shown promises (d. M. Hilty et al. 2017). At last, pedometers and accelerometers (self-monitoring tools) have been introduced with success to encourage adherence (T. S. Marin et al. 2019).

Additionally, this theory is being effectively helpful in physical exertion lineups that involve a variety of patient and non-patient demographics. An efficient strategy to start health behavioural modification has been demonstrated by MI, a client-centered approach (M. S. Hagger and K. Hamilton 2024). Although there isn’t a well-defined theoretical framework for understanding the MI process, the idea that people are naturally capable of developing individually through psychological features is a similar premise between MI and SDT (S. V. Ahmadi et al. 2017). The survivors’ capacity to self-care significantly improved in a case, as a result of an treatment that invigorated medical staff to employ MI to motivate patients to exercise frequently in order to avert lymphoedema (R. Micha 2017). Particularly because it has primarily been carried out on breast cancer patients and survivors to promote physical activity and a healthy lifestyle (S. S. Coughlin et al. 2019), for the sustainability of an active lifestyle, research on the adoption of exercise adherence interventions like MI using behavioural change-related theories may be worthwhile (E. James et al. 2016).

Figure 5.

Displays the theories and approaches for behaviour changes in BCS.

Figure 5.

Displays the theories and approaches for behaviour changes in BCS.

Using MI to Encourage Physical Activity Adherence for Breast Cancer Survivors

It has been exposed that by MI method, across six separate phone calls (15 minutes every two weeks) after active treatments improves self-efficacy in overweight Pakistani breast cancer survivors’ food control and exercise engagement throughout a 12-week period. In actuality, this approach showed up to 70% adherence rates (D. L. Lovelace et al. 2019). In order to promote exercise adherence in survivors of breast cancer, 16-week pilot research of a home-based approach that combined aerobic and weight training enhanced weekly exercise time, aerobic fitness, and quality of life by employing MI through in-person and telephone encounters (T. S. Marin et al. 2019) so, the programs adherence depends much on encouraging self-efficacy and self-confidence (K. J. Picha and D. M. Howell 2018). Participating in a fitness routine with MI for six months (one in-person counseling encounter and two telephone interactions) can raise the average weekly intensity of sporting activities for long-term breast cancer survivors who have high self-efficacy attitudes toward fitness behavior (D. M. Hilty et al. 2017).

Furthermore, MI is an extremely effective method for motivating individuals with breast cancer to engage in physical activity during their treatment. Specifically, MI by phone counselling for a period of 12 months was associated with a positive outcome in the context of encouraging patients to lessen their physique by workout and restricted nutrition throughout medication or chemotherapy (B. Rodrigues et al. 2023). MI has been acknowledged as a useful strategy to encourage personal behaviour modification even if it’s ideal implementation is yet unknown (S. Pudkasam et al. 2018). However, additional research is obligatory to examine optimal practice of MI and associated factors that influence exercise devotion in survivors of breast cancer (B. Thewes et al. 2016).

Exercise and Sexual Health Among Survivors of Breast Cancer

Among the most often overlooked and undertreated side effects of breast cancer and its treatments is sexual dysfunction as the physical alterations that impact sexual health include vaginal dryness, decreased libido, dyspareunia (pain during intercourse), and body image disorders brought on by chemotherapy, hormone therapy, mastectomy, and radiations (S. Vegunta et al. 2022). However, by addressing hormonal balance, body confidence, and psychological well-being, exercise is essential for improving sexual health because frequent exercise helps control androgen and estrogen levels, which can improve sexual response and libido (A. M. Stanton et al. 2018). Furthermore, those who become more physically fit tend to have a more favorable body image, which boosts their confidence in close relationships and increases their level of sexual satisfaction. Additionally, exercise is a potent stress and mood-regulation technique that lowers anxiety and depression, two conditions that are known to affect sexual performance (P. Xue et al. 2025). Also, exercise promotes emotional stability and improves general wellbeing, which makes sexual experiences more satisfying and enjoyable.

Conclusion and Future Prospects

Regular exercise offers cancer survivors major advantages. Therefore, it is crucial to create initiatives and apply techniques to enable these people to start and follow physical activity or exercise regimens. This can be facilitated by a variety of theories and process models, including TPB, SCT, SDT, and TTM. It appears that MI is a reliable approach to enhancing adherence. Researchers could utilise MI and the proposed theories, models, and methodologies to create effective workout plans. Development of these initiatives should also take into account the particular obstacles and problems experienced by people with breast cancer as well as their stage of life.

Emotional, spiritual, and social distress are reported by approximately half of breast cancer survivors. In connection with their long-term cancer diagnosis, prognosis, treatment side effects, and apprehension about cancer recurrence, they experience anxiety, foreboding, and despair. Additionally, socializing, intimacy with partners, physical and sexual ability, and body image are likely to be impacted by breast cancer.

Given the strong correlation between these cancer-related stresses and how people perceive illness, their perspective on breast cancer may have an impact on how they cope and adjust. Positively seeing illness management, breast cancer survivors tend to use a suitable coping mechanism to handle anxiety and reduce their cancer-based unease. For instance, their mental wellness-related eminence of life is enhanced due to their active participation in healthy programs, which is motivated by their combative spirit. This is particularly evident in their ability to receive social and familial support. It is likely that the application of these hypothetical models and MI perceptions in programs promoting physical activeness will augment critical factors of behavioural modification, including self-efficacy, self-regulation, and perceived control, which are essential for physical activity rendezvous. Nevertheless, there exist certain constraints associated with employing such contexts to delineate the relationship amongst critical factors of respective framework and behavioural vicissitudes in breast cancer survivors. Furthermore, the development of a motivating strategy for the increase in physical activity participation is contingent upon an understanding of the factors that affect breast cancer survivors, particularly psychological stress. Although psychological theories are employed to encourage the health of breast cancer survivors by altering their behaviour, additional investigation with explicit determinants is essential to comprehend the variables of adherence and sustainability in physical exercise.

Authors Contributions

M.G.H., M.U.A., S.N., H.Y., made substantial contributions to conceptual design and conduction of this study. M.G.H. and M.U.A. reviewed literature, and wrote article. Images were designed by M.G.H. and Critical revisions and corrections of the article were done by S.N. and H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was available for this study.

Acknowledgment

We offer a token of tribute to those who have published their studies and data on different platforms for critical review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Y. H. Chou, V. Chia-Rong Hsieh, X. X. Chen, T. Y. Huang, and S. H. Shieh, “Unmet supportive care needs of survival patients with breast cancer in different cancer stages and treatment phases,” Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 231–236, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Thewes, S. Lebel, C. Seguin Leclair, and P. Butow, “A qualitative exploration of fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) amongst Australian and Canadian breast cancer survivors,” Support. Care Cancer, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 2269–2276, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Furmaniak, M. Menig, and M. H. Markes, “Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer,” Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., vol. 2016, no. 9, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Pudkasam et al., “Physical activity and breast cancer survivors: Importance of adherence, motivational interviewing and psychological health,” Maturitas, vol. 116, pp. 66–72, 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. E. Klonek, A. V. Güntner, N. Lehmann-Willenbrock, and S. Kauffeld, “Using Motivational Interviewing to reduce threats in conversations about environmental behavior,” Front. Psychol., vol. 6, no. July, pp. 1–16, 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Cebral, Jua; Mut and C. Weir, Jane; Putman, “基因的改变NIH Public Access,” Bone, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Santen, C. A. Stuenkel, S. R. Davis, J. A. V. Pinkerton, A. Gompel, and M. A. Lumsden, “Managing menopausal symptoms and associated clinical issues in breast cancer survivors,” J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., vol. 102, no. 10, pp. 3647–3661, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Laus, S. S. Almeida, and L. A. Klos, “Body image and the role of romantic relationships,” Cogent Psychol., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Williams and S. C. Jeanetta, “Lived experiences of breast cancer survivors after diagnosis, treatment and beyond: Qualitative study,” Heal. Expect., vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 631–642, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Lovelace, L. R. McDaniel, and D. Golden, “Long-Term Effects of Breast Cancer Surgery, Treatment, and Survivor Care,” J. Midwifery Women’s Heal., vol. 64, no. 6, pp. 713–724, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Novakov, “A Closer Look into the Correlates of Spiritual Well-Being in Women with Breast Cancer: The Mediating Role of Social Support,” Spirit. Psychol. Couns., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 113–132, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Marrie et al., “Rising incidence of psychiatric disorders before diagnosis of immune-mediated inflammatory disease,” Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 333–342, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. D. Patsou, G. T. Alexias, F. G. Anagnostopoulos, and M. V. Karamouzis, “Physical activity and sociodemographic variables related to global health, quality of life, and psychological factors in breast cancer survivors,” Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag., vol. 11, pp. 371–381, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Wei, X.-Y. Liu, Y.-Y. Chen, X. Zhou, and H.-P. Hu, “Effectiveness of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual intervention in breast cancer survivors: An integrative review,” Asia-Pacific J. Oncol. Nurs., vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 226–232, 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Izci, A. S. Ilgun, E. Findikli, and V. Ozmen, “Psychiatric Symptoms and Psychosocial Problems in Patients with Breast Cancer,” J. Breast Heal., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 94–101, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Maleki, A. Mardani, M. Ghafourifard, and M. Vaismoradi, “Qualitative exploration of sexual life among breast cancer survivors at reproductive age,” BMC Womens. Health, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Micha, “HHS Public Access,” Physiol. Behav., vol. 176, no. 1, pp. 100–106, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Benson, B. Cobbold, E. Opoku Boamah, C. P. Akuoko, and D. Boateng, “Challenges, Coping Strategies, and Social Support among Breast Cancer Patients in Ghana,” Adv. Public Heal., vol. 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. V. Merluzzi, N. Salamanca-Balen, E. J. Philip, J. M. Salsman, and A. Chirico, “Integration of Psychosocial Theory into Palliative Care: Implications for Care Planning and Early Palliative Care,” Cancers (Basel)., vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 1–17, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Masood and F. Kamran, “Perceptions and Lived Experiences of Breast Cancer Survivors,” Pakistan J. Psychol. Res., vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 165–182, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Y. Hu et al., “Stress, coping strategies and expectations among breast cancer survivors in China: a qualitative study,” BMC Psychol., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Mao et al., “Integrative oncology: Addressing the global challenges of cancer prevention and treatment,” CA. Cancer J. Clin., vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 144–164, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Mehrabizadeh, Z. Zaremohzzabieh, M. Zarean, S. Ahrari, and A. R. Ahmadi, “Narratives of resilience: Understanding Iranian breast cancer survivors through health belief model and stress-coping theory for enhanced interventions,” BMC Womens. Health, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 552, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Hardcastle, C. Maxwell-Smith, S. Kamarova, S. Lamb, L. Millar, and P. A. Cohen, “Factors influencing non-participation in an exercise program and attitudes towards physical activity amongst cancer survivors,” Support. Care Cancer, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 1289–1295, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Binkley et al., “Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment side effects and the prospective surveillance model for physical rehabilitation for women with breast cancer,” Cancer, vol. 118, no. SUPPL.8, pp. 2207–2216, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Corbett, “Article in Press Article in Press,” Eff. grain boundaries paraconductivity YBCO, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2002.

- S. S. Coughlin, R. J. Paxton, N. Moore, J. L. Stewart, and J. Anglin, “Survivorship issues in older breast cancer survivors,” Breast Cancer Res. Treat., vol. 174, no. 1, pp. 47–53, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Seven et al., “Abstract A105: Healthy behaviors among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic people affected by cancer during the post-treatment survivorship,” Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., vol. 32, no. 12_Supplement, pp. A105–A105, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Browall, S. Mijwel, H. Rundqvist, and Y. Wengström, “Physical Activity During and After Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer: An Integrative Review of Women’s Experiences,” Integr. Cancer Ther., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 16–30, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. A. H. Friederichs, A. Oenema, C. Bolman, and L. Lechner, “Motivational interviewing and self-determination theory in a web-based computer tailored physical activity intervention: A randomized controlled trial,” Psychol. Heal., vol. 31, no. 8, pp. 907–930, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Perperidi et al., “Identifying the effective behaviour change techniques in nutrition and physical activity interventions for the treatment of overweight/obesity in post-treatment breast cancer survivors: a systematic review,” Cancer Causes Control, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 683–703, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Kim et al., “Development of an exercise adherence program for breast cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue—an intervention mapping approach,” Support. Care Cancer, vol. 27, no. 12, pp. 4745–4752, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Cambon and F. Alla, “Understanding the complexity of population health interventions: assessing intervention system theory (ISyT),” Heal. Res. Policy Syst., vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Langarizadeh, M. S. Tabatabaei, K. Tavakol, M. Naghipour, A. Rostami, and F. Moghbeli, “Telemental health care, an effective alternative to conventional mental care: A systematic review,” Acta Inform. Medica, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 240–246, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Altawallbeh, F. Soon, W. Thiam, and S. Alshourah, “Mediating role of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control in the relationships between their respective salient beliefs and behavioural intention to adopt e-learning among instructors in Jordanian universities.,” J. Educ. Pract., vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 152–160, 2015.

- M. S. DINC and S. BUDIC, “The Impact of Personal Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavioural Control on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Women,” Eurasian J. Bus. Econ., vol. 9, no. 17, pp. 23–35, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, N. Lu, S. Qin, W. Wu, F. Cheng, and H. You, “Theoretical Explanation of Upper Limb Functional Exercise and Its Maintenance in Postoperative Patients With Breast Cancer,” Front. Psychol., vol. 12, no. January, pp. 1–10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Coull and G. Pugh, “Maintaining physical activity following myocardial infarction: a qualitative study,” BMC Cardiovasc. Disord., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Hagger and K. Hamilton, “Longitudinal tests of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis,” Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol., vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 198–254, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. V. Ahmadi Tabatabaei, H. Eftekhar Ardabili, A. A. Haghdoost, M. Dastoorpoor, N. Nakhaee, and M. Shams, “Factors affecting physical activity behavior among women in kerman based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB),” Iran. Red Crescent Med. J., vol. 19, no. 10, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Travier et al., “Effects of an 18-week exercise programme started early during breast cancer treatment: A randomised controlled trial,” BMC Med., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. Freeman and D. Y. Wohn, “Social support in eSports: Building emotional and esteem support from instrumental support interactions in a highly competitive environment,” CHI Play 2017 - Proc. Annu. Symp. Comput. Interact. Play, pp. 435–447, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Wang et al., “A Study on the Correlation Between Undergraduate Students’ Exercise Motivation, Exercise Self-Efficacy, and Exercise Behaviour Under the COVID-19 Epidemic Environment,” Front. Psychol., vol. 13, no. July, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Gunaretnam, “A Study on Increasing Positive Behaviors Using Positive Reinforcement Techniques,” Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci., vol. 05, no. 07, pp. 198–219, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. G. Stacey, E. L. James, K. Chapman, K. S. Courneya, and D. R. Lubans, “A systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognitive theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors,” J. Cancer Surviv., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 305–338, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Karloh et al., “Breaking barriers to rehabilitation: the role of behavior change theories in overcoming the challenge of exercise-related behavior change,” Brazilian J. Phys. Ther., vol. 27, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Rodrigues, E. V. Carraça, B. B. Francisco, I. Nobre, H. Cortez-Pinto, and I. Santos, “Theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review,” J. Cancer Surviv., pp. 1464–1480, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Morris, M. M. Grehl, S. B. Rutter, M. Mehta, and M. L. Westwater, “On what motivates us: A detailed review of intrinsic v. extrinsic motivation,” Psychol. Med., vol. 52, no. 10, pp. 1801–1816, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. V. Carraça et al., “Promoting physical activity through supervised vs motivational behavior change interventions in breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors (PAC-WOMAN): protocol for a 3-arm pragmatic randomized controlled trial,” BMC Cancer, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. C. Lin, J. S. C. Hsu, H. L. Cheng, and C. M. Chiu, “Exploring the relationship between receiving and offering online social support: A dual social support model,” Inf. Manag., vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 371–383, 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Wright, “Communication in health-related online social support groups/communities: A review of research on predictors of participation, applications of social support theory, and health outcomes,” Rev. Commun. Res., vol. 4, pp. 65–87, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Hilty, S. Chan, T. Hwang, A. Wong, and A. M. Bauer, “Advances in mobile mental health: opportunities and implications for the spectrum of e-mental health services,” mHealth, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 34–34, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Marin et al., “Constance Kourbelis,” vol. 6811, 2019.

- E. James et al., “Comparative efficacy of simultaneous versus sequential multiple health behavior change interventions among adults: A systematic review of randomised trials,” Prev. Med. (Baltim)., vol. 89, pp. 211–223, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Picha and D. M. Howell, “A model to increase rehabilitation adherence to home exercise programmes in patients with varying levels of self-efficacy,” Musculoskeletal Care, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 233–237, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Vegunta, C. L. Kuhle, J. A. Vencill, P. H. Lucas, and D. M. Mussallem, “Sexual Health after a Breast Cancer Diagnosis: Addressing a Forgotten Aspect of Survivorship,” J. Clin. Med., vol. 11, no. 22, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Stanton, A. B. Handy, and C. M. Meston, “The Effects of Exercise on Sexual Function in Women,” Sex. Med. Rev., vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 548–557, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Xue, X. Du, and J. Kong, “Age-dependent mechanisms of exercise in the treatment of depression: a comprehensive review of physiological and psychological pathways,” Front. Psychol., vol. 16, no. April, 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).