Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Objectives

- Evaluate the theoretical and practical concepts of production potential and productivity in agricultural economics.

- Analyze the historical development and current status of Nigeria’s agricultural sector and its importance to the national economy.

- Identify the key production resources available in Nigeria and assess their effectiveness and utilization in agricultural development.

- Assess productivity trends and measures across Nigeria’s agricultural zones, focusing on the comparative performance of land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurship.

- Examine major agricultural products, their regional distribution, levels of self-sufficiency, and export potential.

2.2. Scope

- Covers all subsectors of agriculture including crop production, livestock, and agro-processing.

- Considers the roles of gender, youth, and smallholder farmers in agricultural productivity.

- Analyses national agricultural data from major institutions like the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), World Bank, FAOSTAT, and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

- Reviews policy frameworks such as the Agricultural Transformation Agenda (ATA), Green Alternative, and Anchor Borrowers’ Programme.

- Integrates environmental sustainability, infrastructure challenges, technological adoption, and market accessibility as cross-cutting themes influencing productivity.

3. The Idea of Production Potential and Productivity in Economic Theory

3.1. The Concept of Production Potential and Productivity

3.1.1. Historical Evolution of the Concepts

3.1.2. Importance in Economic Analysis

3.1.3. Measurement and Indicators

3.2. Resources of Production Factors

3.2.1. Land, Natural Resources and Technology

3.2.2. Labour and Entrepreneurship

3.2.3. Capital

3.3. Relations Between Production Factors

3.3.1. Economic Models and Theories

3.3.2. Policy Implications

4. Productivity of Production Factors

4.1. Productivity Measures

4.2. Trends in Agricultural Productivity in Nigeria

4.3. Opportunities for Youth and Women in Agriculture

4.4. Innovative Farming Techniques

4.5. The Role of ICT in Modernizing Agriculture

4.6. Socioeconomic Barriers to Agricultural Productivity

- Bureaucratic Loan Processes: Financial institutions demand stringent requirements from borrowers which include asking for collateral objects and detailed financial documentation and heavy paperwork demands. A combination of demands which exceeds what smallholder farmers possess prevents them from completing official loan applications since many lack basic education and formal land titles.

- Limited Financial Inclusion in Rural Areas: Financial inclusion programmes fail to reach their full potential since formal banks rarely extend their services to rural areas of Nigeria. Farmer populations located in distant locations encounter major obstacles when trying to reach financial institutions because the travel distances prolong the process and create high costs for borrowing.

- High Risk Perception: Poor agricultural investments scare financial institutions because unpredictable weather patterns, pest outbreaks and price fluctuations make farming a high-risk industry. The assessment of high risk within agriculture prevents banks from providing credit to farmers especially those practicing rain-fed agriculture.

5. Production of Main Agricultural Products

5.1. Major Agricultural Products and Their Regional Distribution

5.2. Self-Sufficiency Indicators

5.3. Potential for Export and Economic Diversification

6. Conclusions

- Nigeria has vast areas of arable land and a climate that supports the production of a wide variety of crops. However, poor land management, weak irrigation systems, land degradation, and growing desertification in northern regions have reduced productivity. Most smallholder farmers still rely on rain-fed farming, making them vulnerable to unpredictable weather.

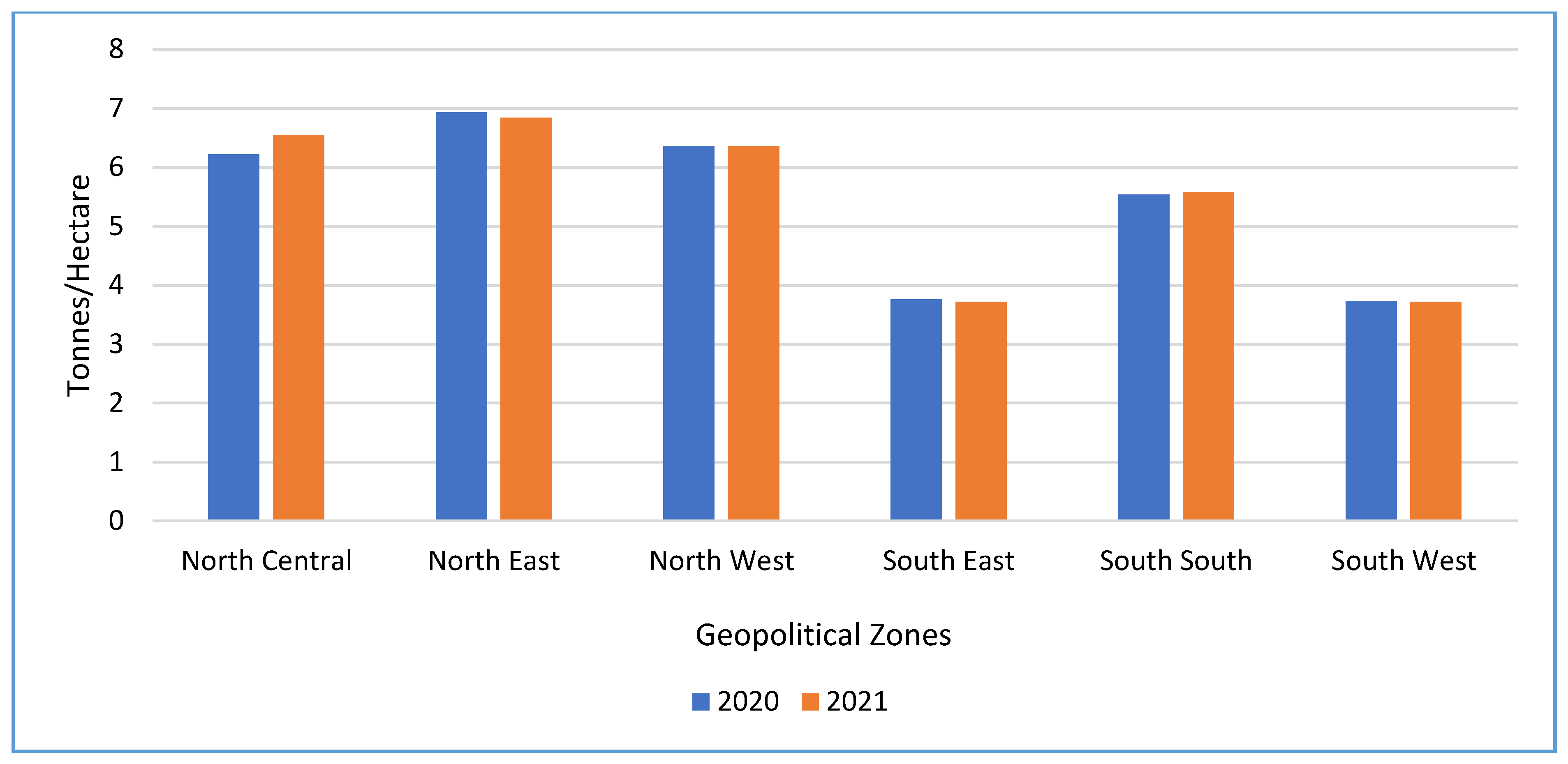

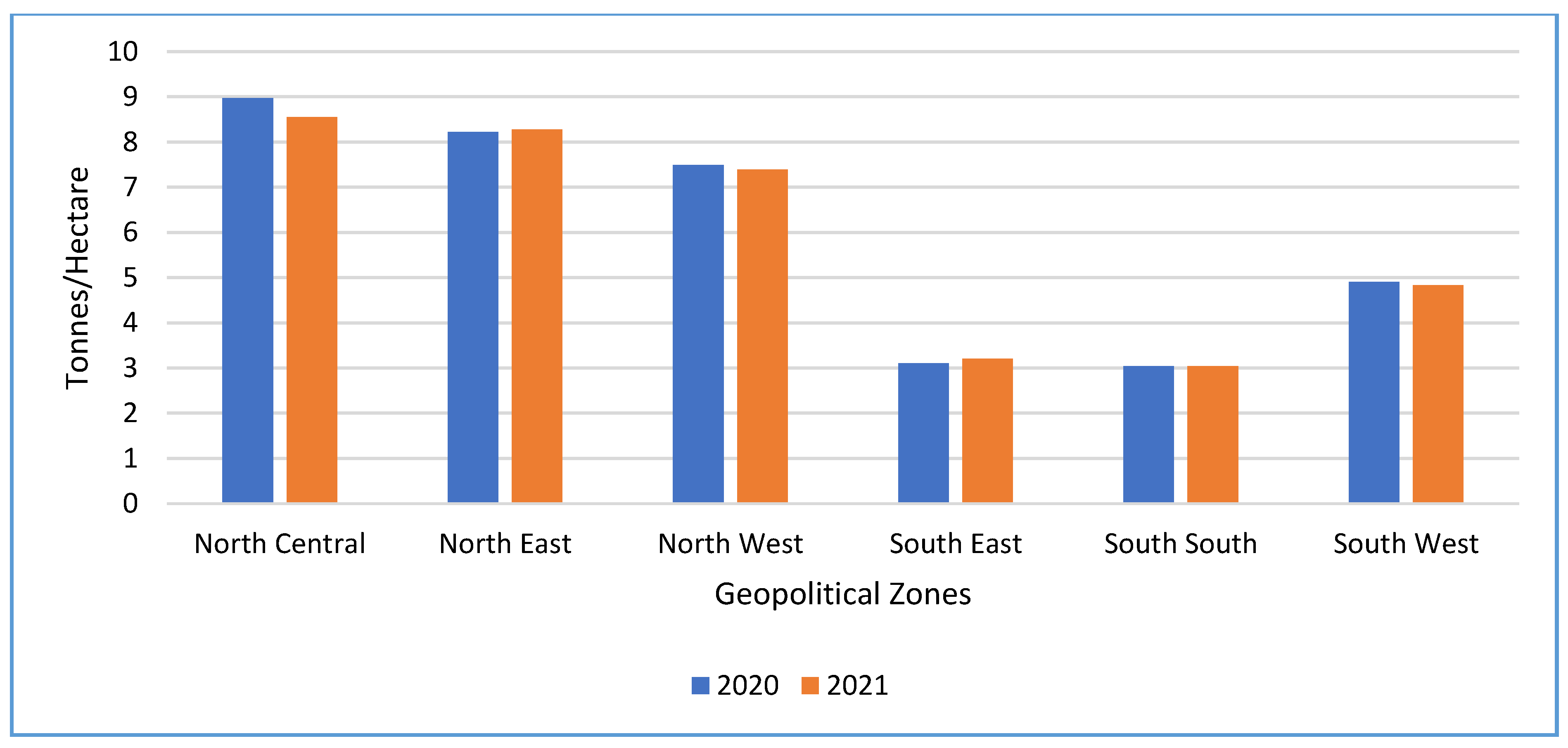

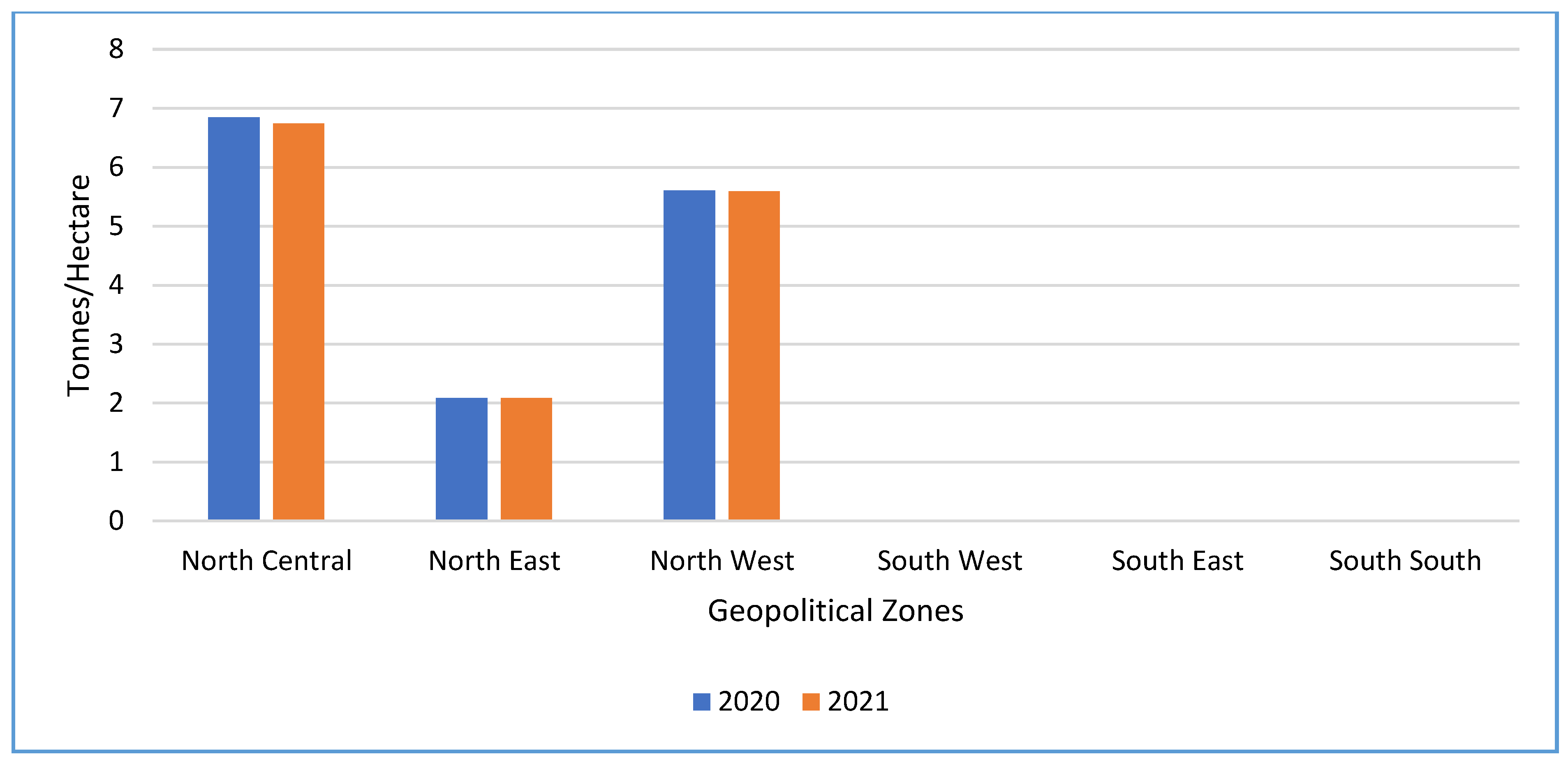

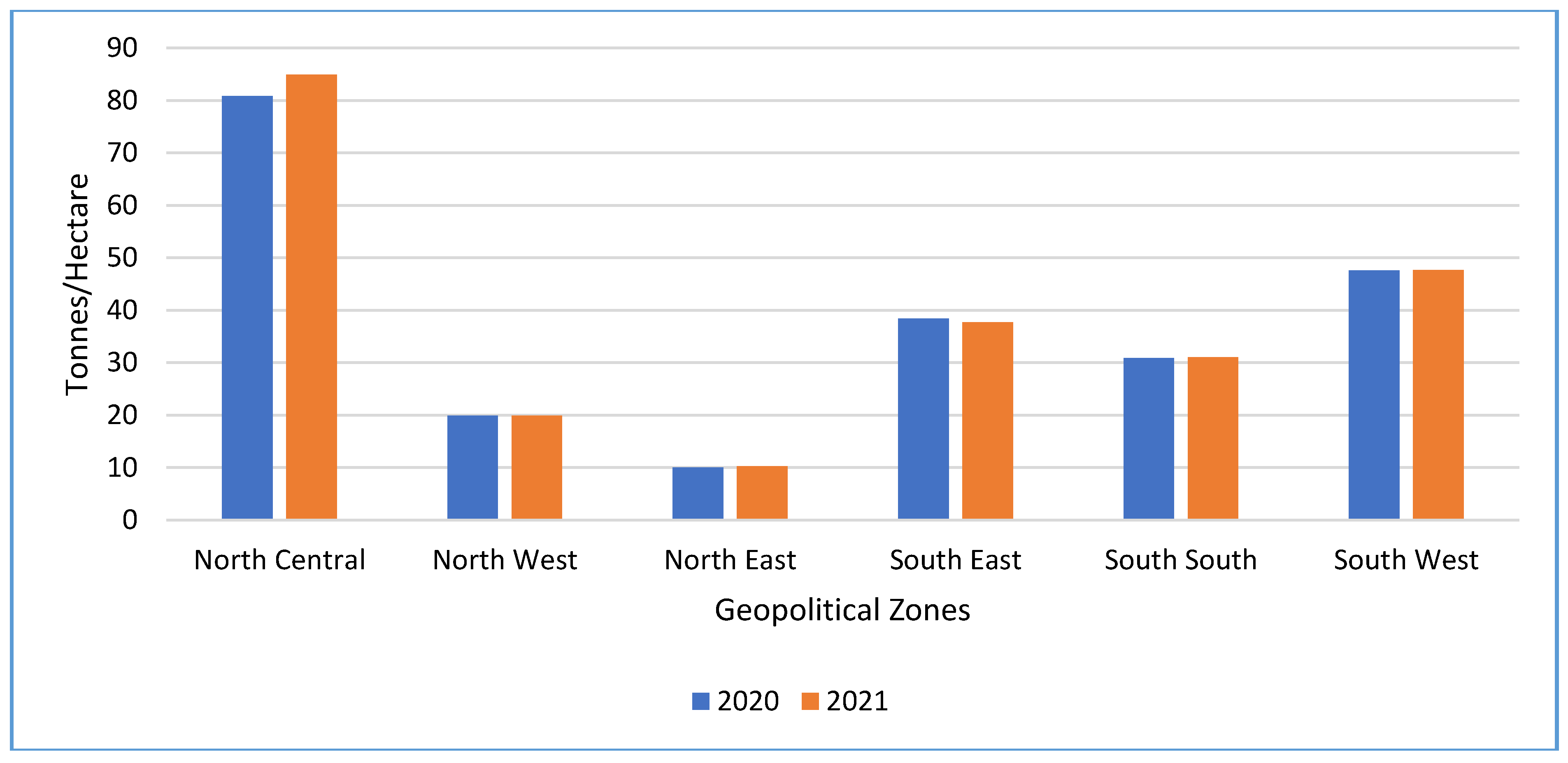

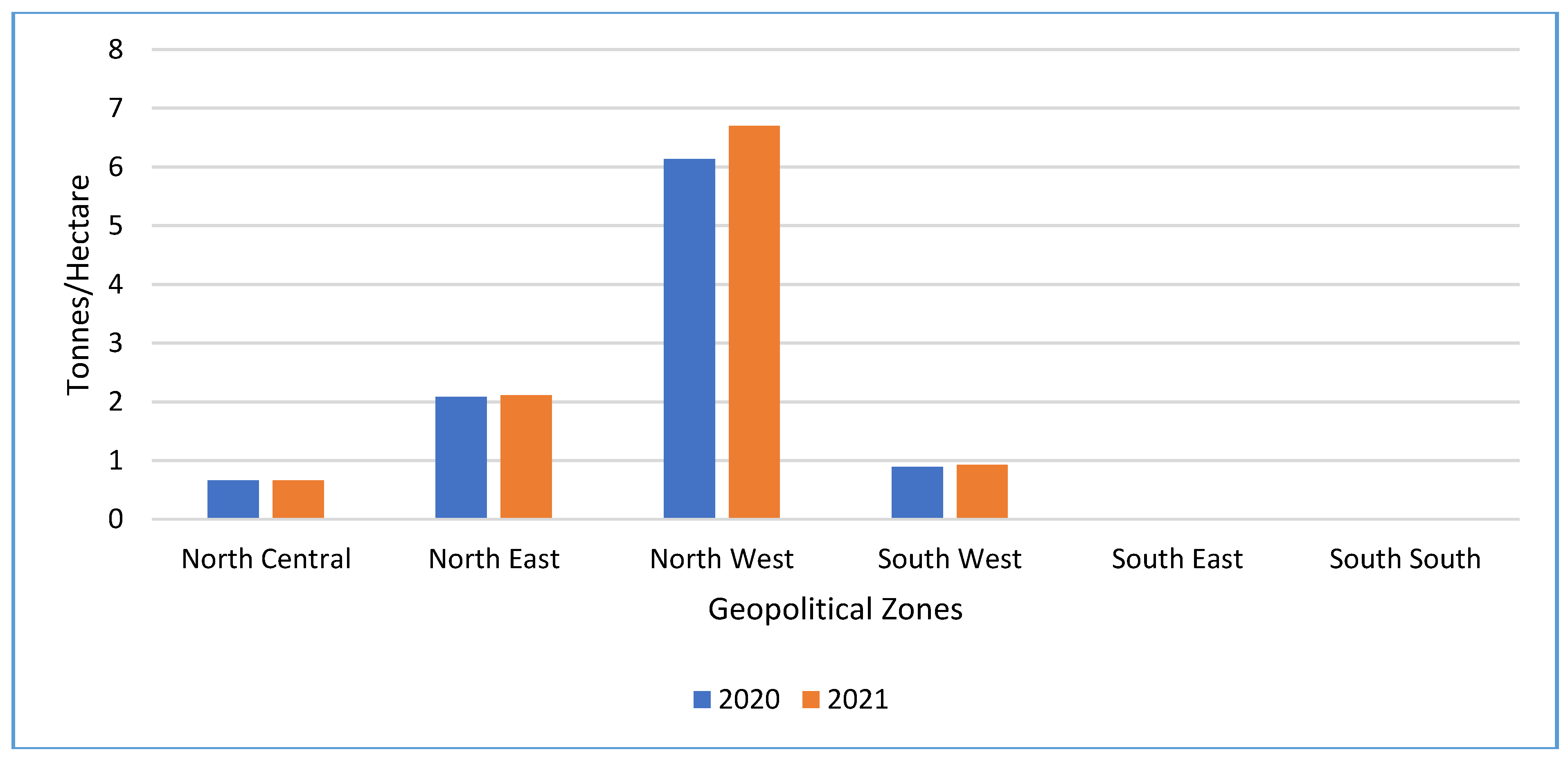

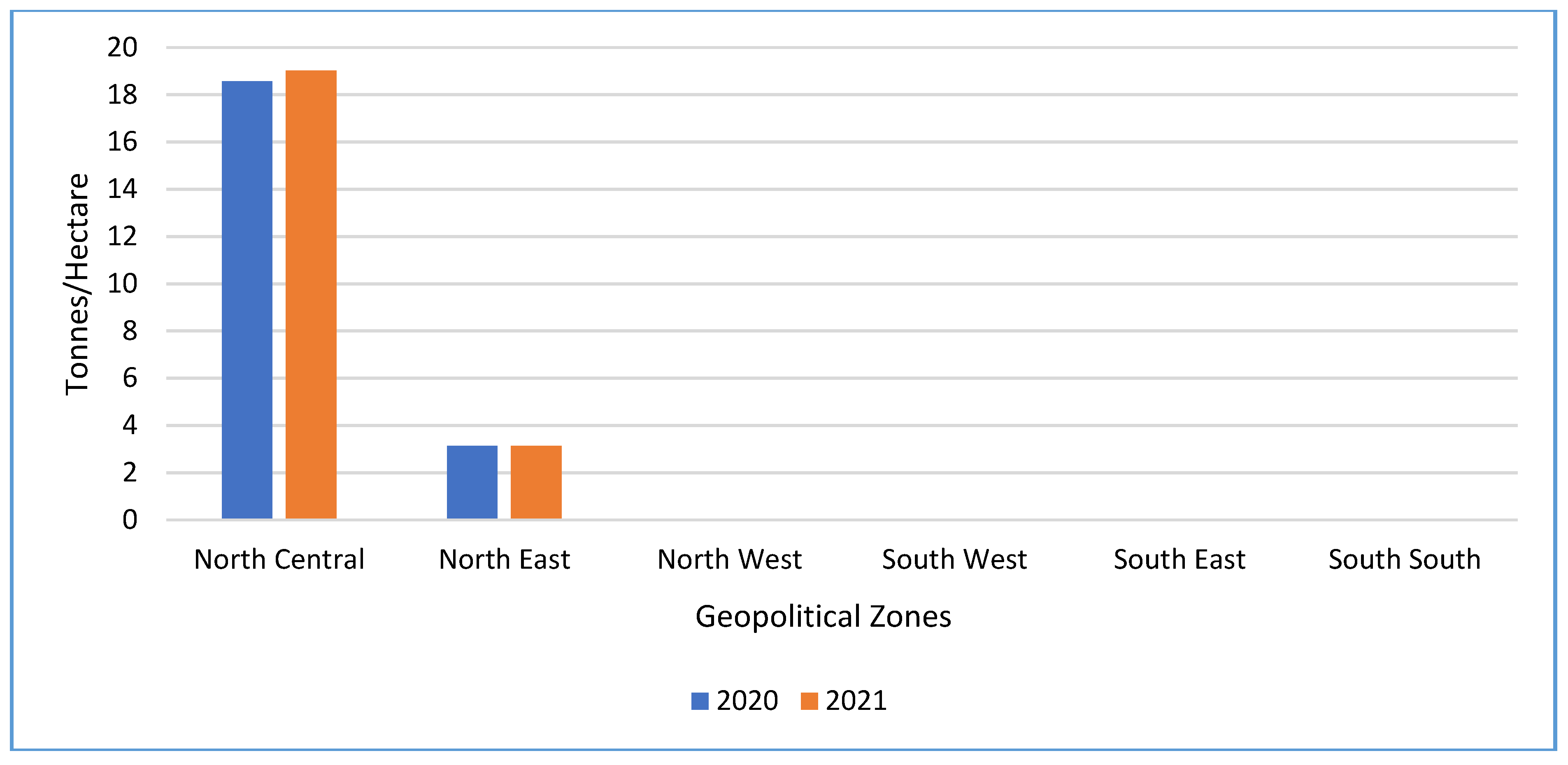

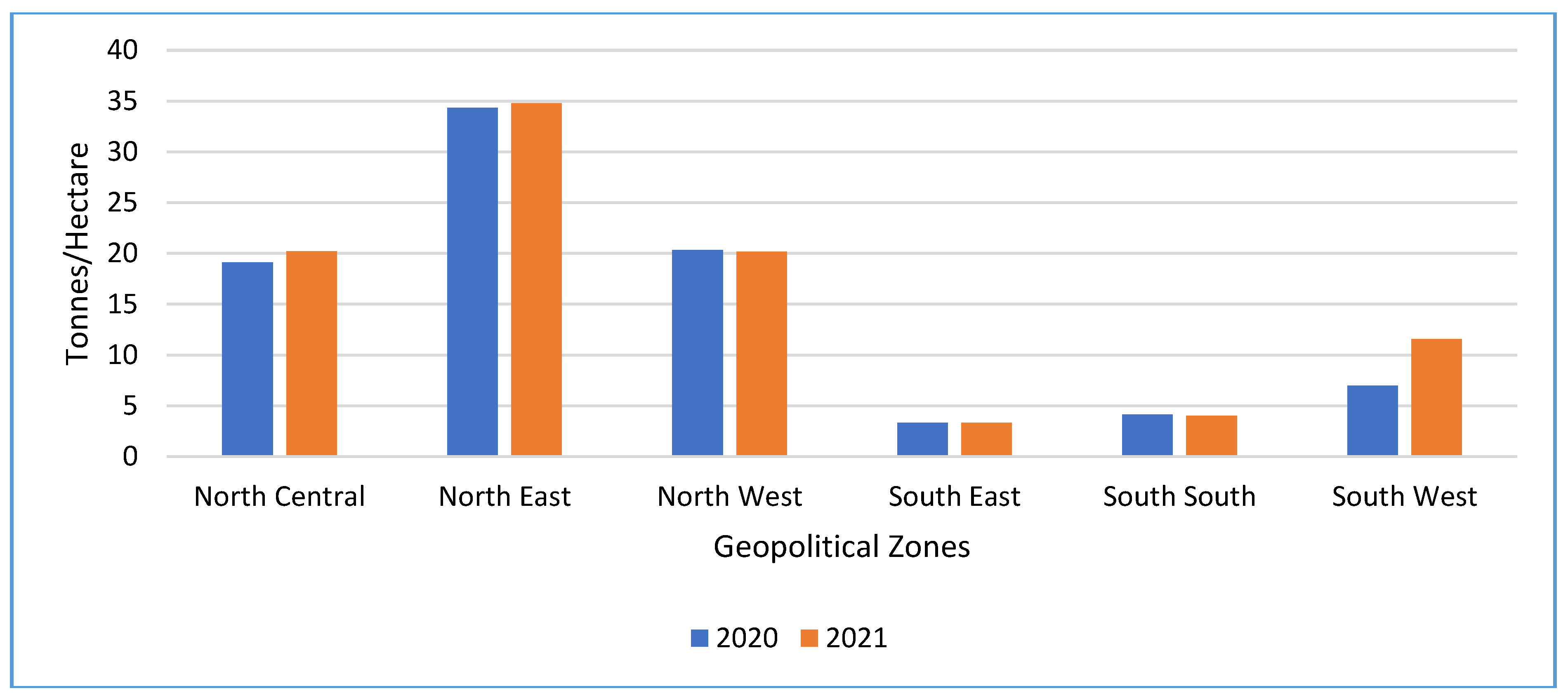

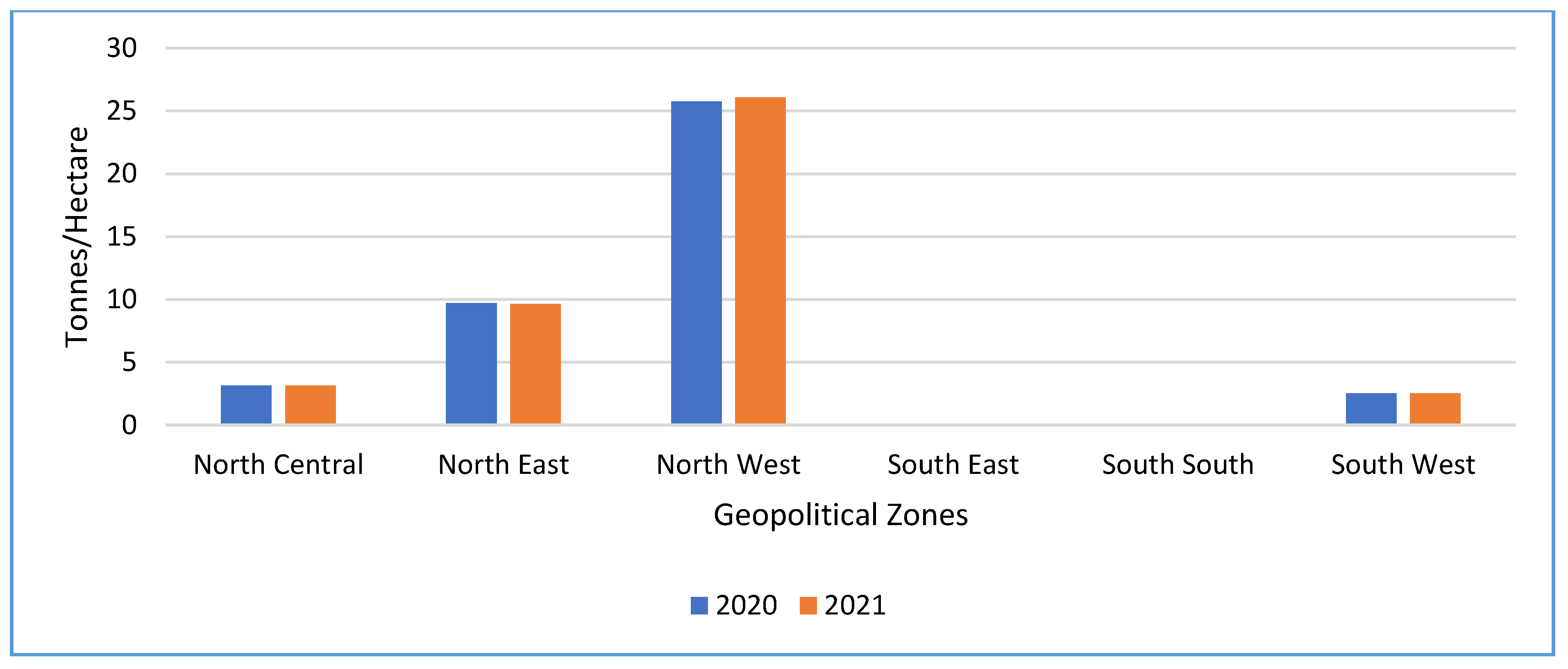

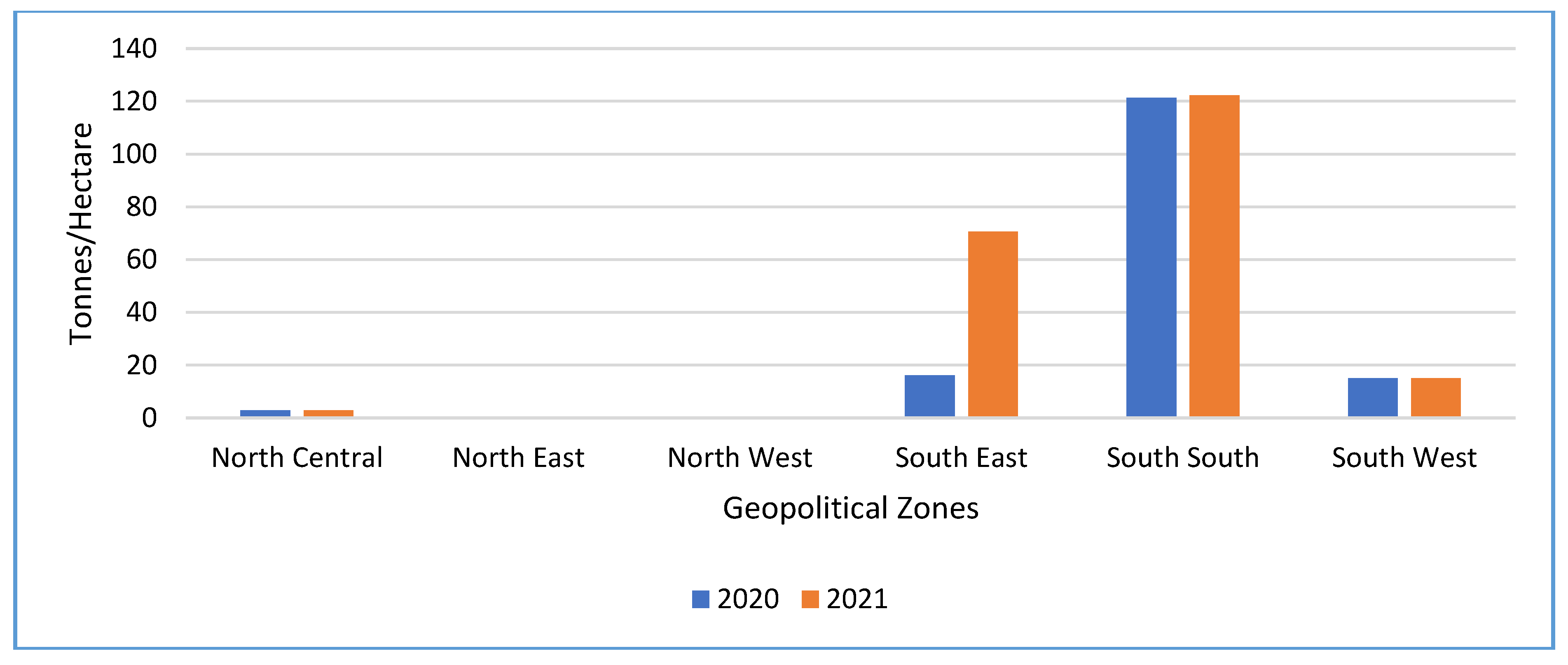

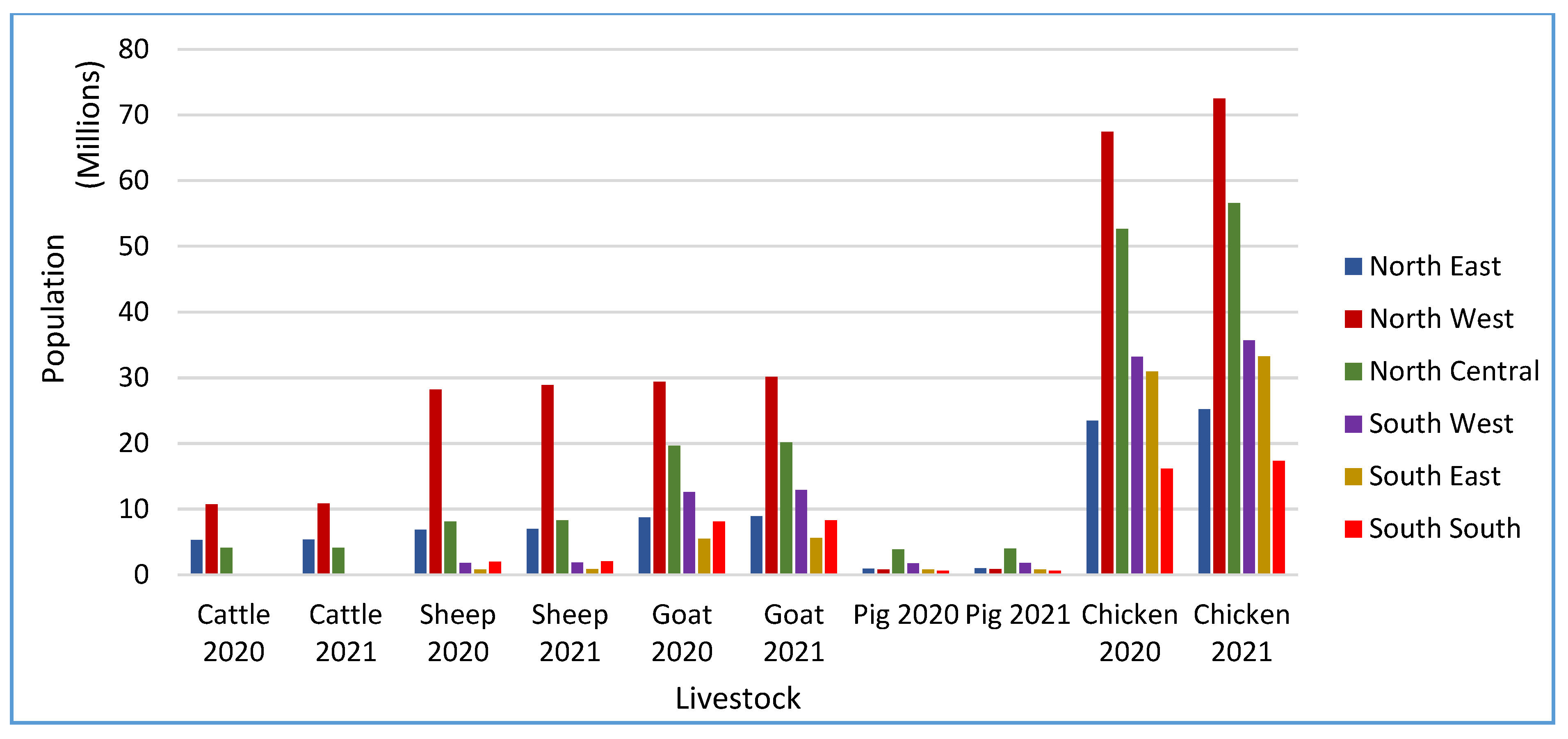

- The regional analysis of agricultural productivity demonstrated strong geographic specialization. Northern Nigeria leads in cereals and legume production, while the southern regions dominate in tubers, oil crops, and vegetables. Ginger, yam, cassava, tomatoes, and cotton all showed impressive regional productivity improvements in recent years, indicating a positive government response and private interventions in select zones. However, national-level constraints like limited mechanization, inadequate access to improved seeds, and insufficient extension services still hinder wider growth

- The sector's mixed performance in achieving self-sufficiency, with crops like rice, maize, and yam demonstrating significant gains over the past decade, while cassava, millet, and animal products show wide fluctuations. The self-sufficiency ratio for rice rose impressively from 64.9% in 2012 to 115.5% in 2022, highlighting the positive effect of targeted policies such as the Anchor Borrowers’ Programme and border restrictions. Conversely, crops like cassava saw a drop from 246.1% to 169.2% within the same period, reflecting rising demand and post-harvest losses due to poor infrastructure and limited processing capacity.

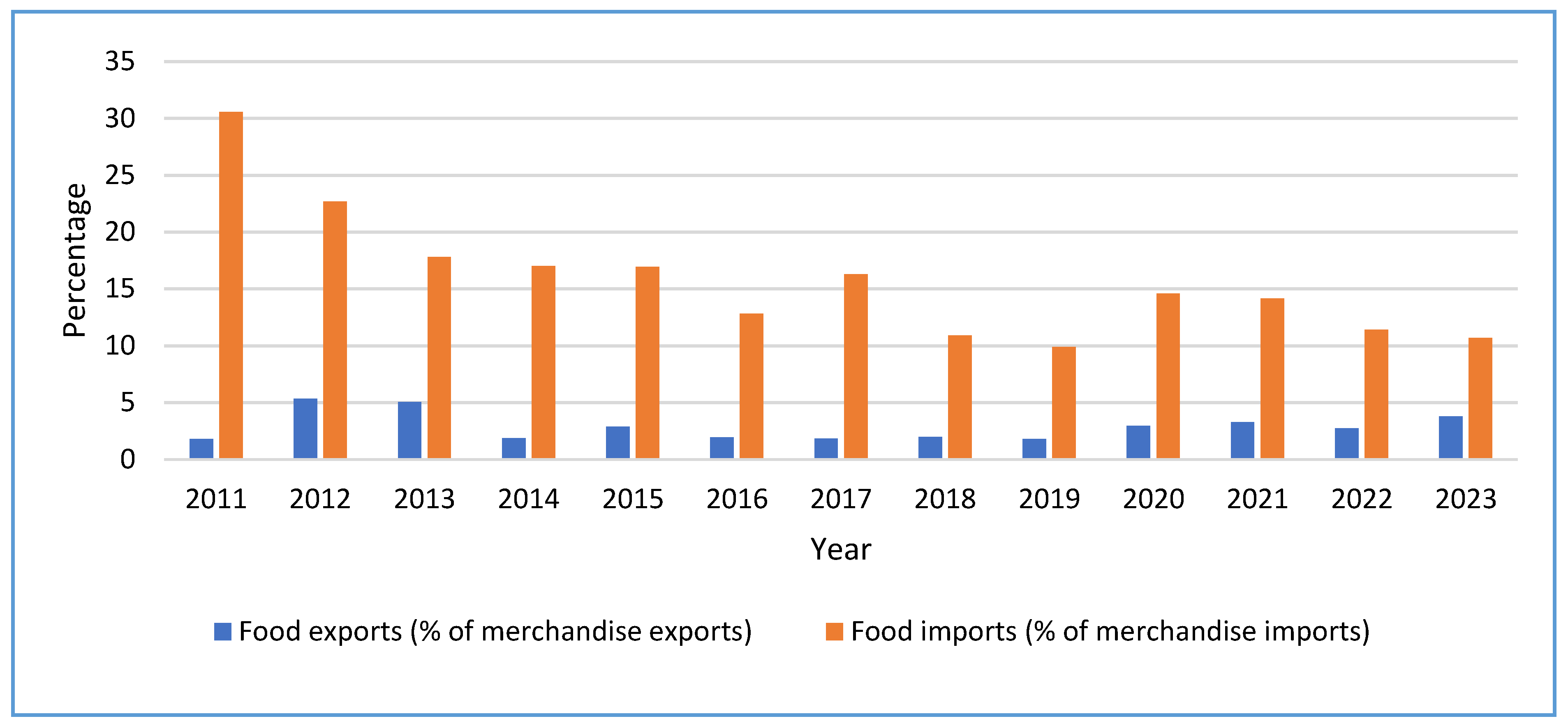

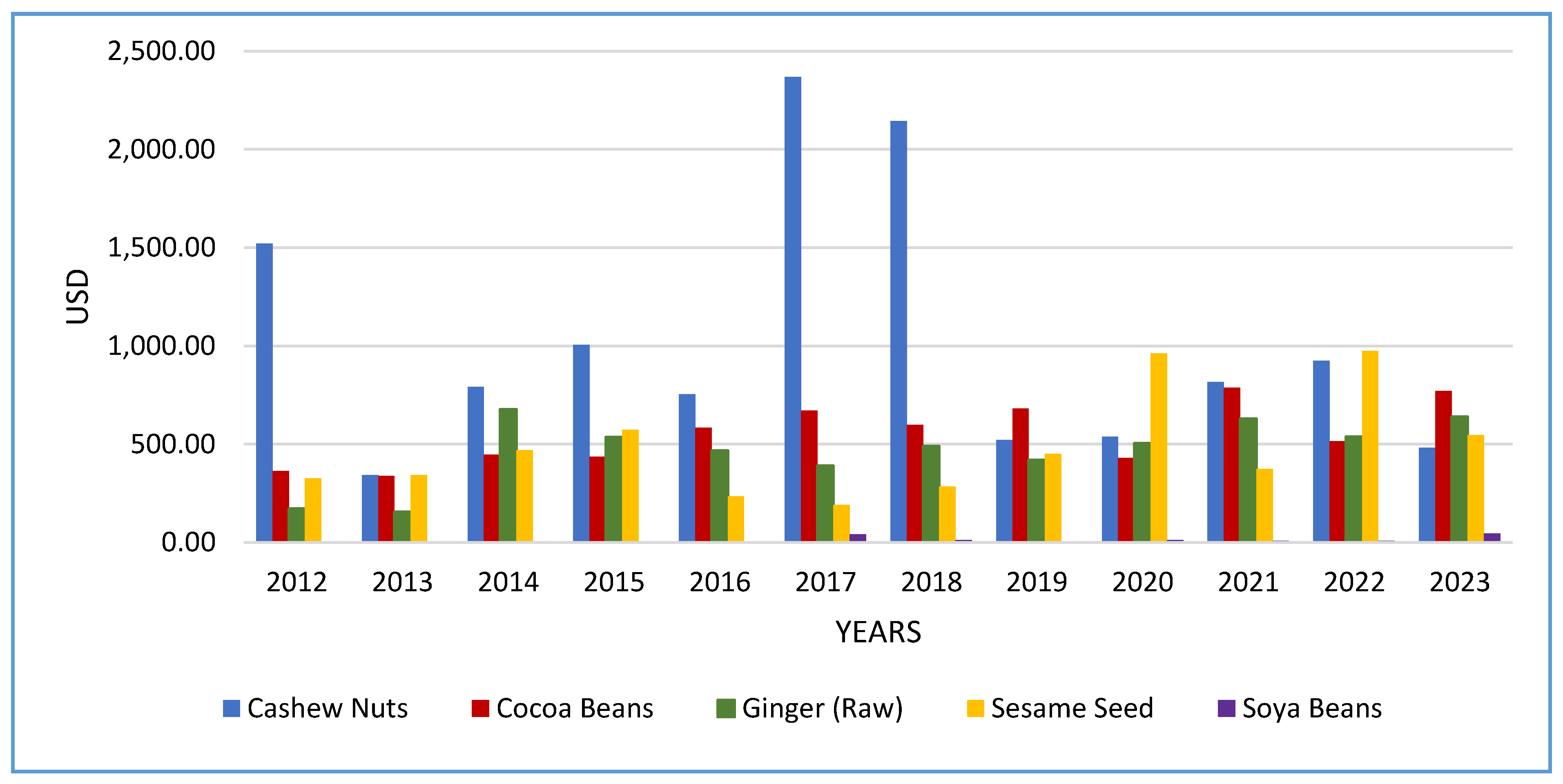

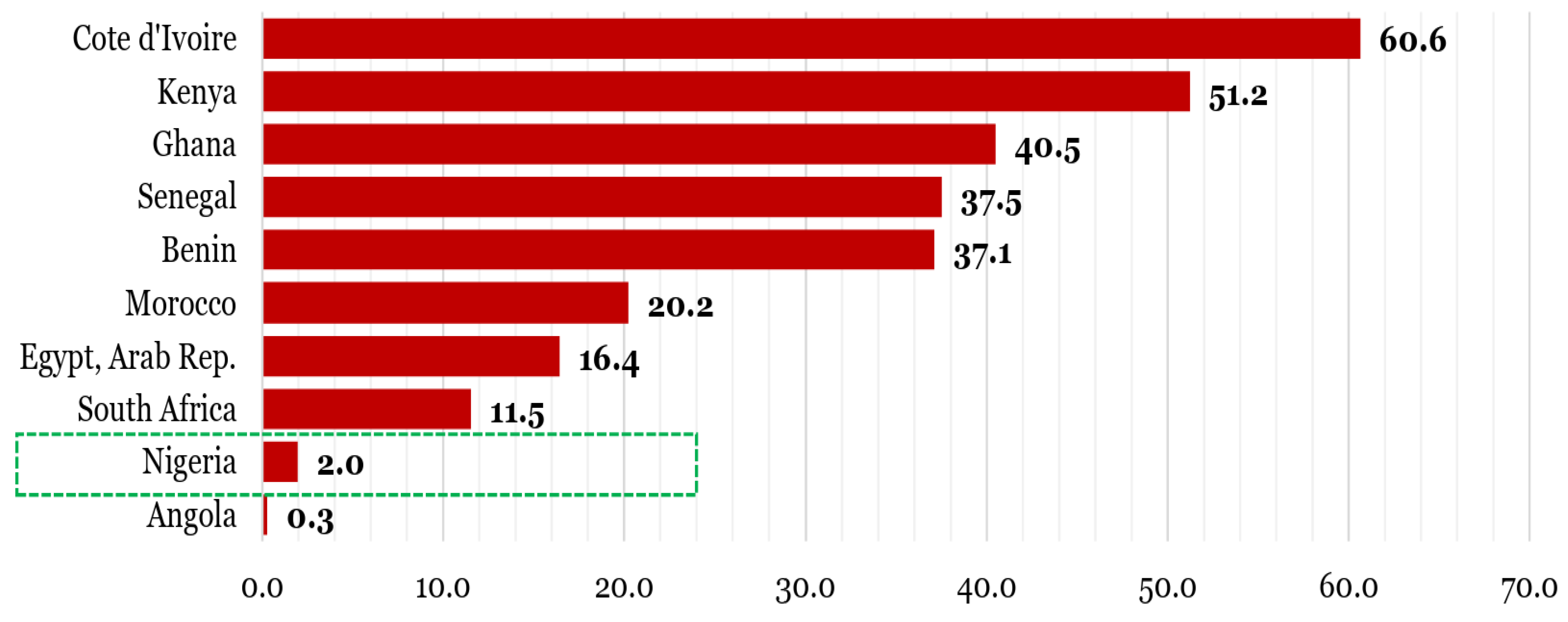

- On the export front, Nigeria continues to underperform despite having vast potential. Agricultural exports accounted for only 3.8% of total exports in 2023, with cashew nuts as the leading contributor. However, the export share of cashew also declined from 28.2% in 2012 to 4.3% in 2023, indicating instability in production and a lack of value addition. Products like cocoa, sesame, and ginger contributed minimally to the national export portfolio despite their global market demand. These findings reveal that export potential remains largely untapped due to weak agro-processing, poor market access, and inconsistent trade policies.

- Furthermore, the analysis identified several critical challenges affecting productivity: lack of infrastructure, limited credit access, gender disparities in land ownership, and environmental threats such as climate change and deforestation. While public-private partnerships and programs like the Green Alternative and Agricultural Transformation Agenda show promise, gaps in funding, implementation, and monitoring limit their long-term impact.

- Improve Resource Utilization and Technology Adoption – There is a need to promote better use of land, labour, and capital through the adoption of modern technologies like mechanization, ICT, and precision agriculture. Training and extension services should be increased for farmers.

- Strengthen Infrastructure and Investment – Investment in rural infrastructure such as irrigation, storage, and processing facilities should be prioritized. Government support through increased budget allocation, public-private partnerships, and credit schemes will help boost productivity and reduce post-harvest losses.

- Address Policy and Regulatory Barriers – Agricultural policies should be well-implemented and consistent to encourage private sector participation. Trade policies must also support agricultural exports by removing unnecessary barriers and creating an enabling environment for growth.

- Support Youth and Women Participation in Agriculture – Programs that offer access to land, training, and finance should be expanded to empower youth and women. Encouraging agripreneurship will improve productivity and reduce unemployment in rural areas.

- Boost Value Addition and Trade Opportunities – To achieve self-sufficiency, especially in regional production, targeted support such as improved seeds in the North and better storage in the South should be encouraged. Nigeria must also invest more in agro-processing and improve product standards to meet export requirements in order to reduce imports. Strengthening regional trade hubs and promoting exportable crops will enhance the country’s trade performance and economic diversification.

References

- Abdelsadek, Y., & Kacem, I. (2022). Productivity improvement based on a decision support tool for optimization of constrained delivery problem with time windows. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 165, 107876. [CrossRef]

- Abdulai, S., Zakariah, A., &Donkoh, S. A. (2018b). Adoption of rice cultivation technologies and its effect on technical efficiency in Sagnarigu District of Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 4(1): 1424296. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, R., Najim, M., & Esham, M. (2024). Agriculture for Sustainable Development to Empower Smallholder Farming Communities. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 19(3), 462–474. [CrossRef]

- Abdulwaheed, A. (2019). Benefits of Precision Agriculture in Nigeria. London Journal of Research in Science: Natural and Formal, 19(2), 29-34. https://www.journalspress.com/LJRS_Volume19/507_Benefits-of-Precision-Agriculture-in-Nigeria.pdf.

- Abdurakhmonov, B. I. (2025). Perspective Chapter: Vertical Farming Innovations – A Brief Overview. In Greenhouses - Cultivation Strategies for the Future [Working title]. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Abobatta, W. F. & Fouad, F. W. (2024). Sustainable Agricultural Development: Introduction and Overview. In W. Abobatta & W. Hussain (Eds.), Achieving Food Security Through Sustainable Agriculture (pp. 1-28). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I. R. (2021). Predictors of inequalities in land ownership among Nigerian households: Implications for sustainable development. Land Use Policy, 101, 105194. [CrossRef]

- ACAPS. (2019, October 17). Floods in Borno, Delta, Kebbi, and Kogi states: Briefing note [Briefing note]. https://reliefweb.int/attachments/bd692958-0034-3f20-99da-fee212d0990b/20191017_acaps_start_briefing_note_nigeria_floods.pdf.

- Actionaid, (2023). Analysis of the 2024 proposed agriculture budget. Retrieved 5th January, 2025 from https://nigeria.actionaid.org/publications/2023/analysis-2024-proposed-agriculture-budget.

- Adebunmi, A. O., Ajala, A. K., & Ganiyu, M. O. (2024). Farm mechanization innovation capacity and rice productivity: Evidence from small scale rice farmers in Kwara State, Nigeria. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 9(9), 2102-2107. [CrossRef]

- Adegbaju, M. S., Ajose, T., Adegbaju, I. E., Omosebi, T., Ajenifujah-Solebo, S. O., Falana, O. Y., Shittu, O. B., Adetunji, C. O., & Akinbo, O. (2024). Genetic engineering and genome editing technologies as catalyst for Africa’s food security: the case of plant biotechnology in Nigeria. Frontiers in Genome Editing, 6:1398813. [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, A., & Alluri, K. (2006). Using ODL aided by ICT and internet to increase agricultural productivity in rural Nigeria. The Fourth Pan-Commonwealth Forum on Open Learning (PCF4). Commonwealth of Learning and the Caribbean Consortium. http://pcf4.dec.uwi.edu/viewpaper.php?id=148.

- Adekunle, I. O. (2013). Precision Agriculture: Applicability and Opportunities for Nigerian Agriculture. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 13(9), 1230-1237 http://www.idosi.org/mejsr/mejsr13(9)13/16.pdf.

- Adenugba, A. O., & Raji-Mustapha, N. O. (2013). The role of women in promoting agricultural productivity and developing skills for improved quality of life in rural areas. IOSR Journal of Engineering (IOSRJEN), 3(8, V5), 51–58. https://www.iosrjen.org/Papers/vol3_issue8%20(part-5)/H03855158.pdf.

- Adesehinwa, A. O., Boladuro, B. A., Dunmade, A. S., Idowu, A. B., Moreki, J. C., & Wachira, A. M. (2024). Pig production in Africa: current status, challenges, prospects and opportunities. Animal Bioscience, 37(4), 730.

- Adesoye, A., Akinola, O., & Akinbobola, T. (2018). Impact of Agricultural Inputs on Agricultural Productivity and Economic Growth in Nigeria. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 27(3), 1-10. (Available at: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajer/article/view/166028).

- Adesugba, M.; Mavrotas, G. Youth Employment, Agricultural Transformation and Rural Labour Dynamics; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/publication/youth-employment-agricultural-transformation-and-rural-labour-dynamics-nigeria (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Adetunbi, S. I., & Olayemi, A. W. (2024). Awareness Level of Farmers on Agricultural Related Softwares for Improved Agricultural Production: Panacea for Food Insecurity in Iseyin Local Government Area of Oyo State. American Journal of Agriculture, 6(3), 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Adewuyi, S. A., Tolorunju, E. T., Olusanya, I. O., & Abdulazeez, O. A. (2024). Determinants and Constraints of Access to Credit by Poultry Egg Farmers in Ogun State Nigeria. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics and Sociology, 42(11), 357–365. [CrossRef]

- Adeyolanu, D. T., & Okelola, O. E. (2024). Irrigation Water Management and Food Security in Nigeria. African Journal of Agriculture and Food Science, 7(4), 117–132. [CrossRef]

- Adisa, R. S., Adefalu, L. L., Olatinwo, L. K., Balogun, K. S., & Ogunmadeko, O. O. (2015). Determinants of post-harvest losses of yam among yam farmers in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Bulletin of the Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Kyushu University, 38(1), 073-078.

- Afanasiev, M.M. (2006). A Model of the Production Potential with Managed Factors of Inefficiency. Applied Econometrics, 4, 74-89.

- Agber, T., Iortima, P.I., Imbur, E.N. (2013) Lessons from implementation of Nigeria’s past national agricultural programs for the transformation agenda. American Journal of Research Communication, 1(10): 238-253. http://www.usa-journals.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Agber1_Vol110.pdf.

- Agbola, T., 2004. Readings in Urban and Regional Planning. Macmillan Nigeria Limited, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria, pp. 179.

- Agbor, U. I., & Eteng, F. O. (2018). Challenges of rural women in agricultural production and food sufficiency in Cross River State, Nigeria. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 5(12), 385–400. [CrossRef]

- AgroCares. (2023). Understanding the role of soil testing in modern agriculture. Retrieved from https://agrocares.com/understanding-the-role-of-soil-testing-in-modern-agriculture/.

- Ahungwa, G. T., Haruna, U., & Abdusalam, R. Y. (2014). Trend Analysis of the Contribution of Agriculture to the Gross Domestic Product of Nigeria (1960 - 2012). IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science, 7(1), 50–55. [CrossRef]

- Ajie, E. N., & Uche, C. (2025). Climate Smart Agriculture in Food Insecurity Mitigation in Nigeria: A Conceptual Evaluation. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics and Sociology, 43(1), 63–71. [CrossRef]

- Akinbode, S. O., Folorunso, O., Olutoberu, T. S., Olowokere, F. A., Adebayo, M., Azeez, S. O., Hammed, S. G., & Busari, M. A. (2024). Farmers’ perception and practice of soil fertility management and conservation in the era of digital soil information systems in Southwest Nigeria. Agriculture, 14(7), 1182. [CrossRef]

- Akinborode, T. I., & Olaoye, F. L. (2024). Vegetable production in Nigeria: the growth and limiting factors. [CrossRef]

- Akinkuolie, T. A., Ogunbode, T. O., & Adekiya, A. O. (2025). Resilience to climate-induced food insecurity in Nigeria: a systematic review of the role of adaptation strategies in flood and drought mitigation. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 8. [CrossRef]

- Akinnagbe, O. M. (2023). Use of Conservation Practices among Arable Crop Farmers in Oyo State, Nigeria. The Journal of Agricultural Extension, 27(2), 104–113. [CrossRef]

- Akpan, S. B., Udoh, E. J., Nkanta, V. S., Patrick, I.-m. V. (2025). The Impact of Credit Policy Environment on Agricultural Output in Nigeria. Research in Agricultural Sciences, 56(1), 39-49. [CrossRef]

- Alhaji, I. H. (2008). Revitalizing Technical and Vocational Education Training for Poverty Eradication and Sustainable Development Through Agricultural Education. African Research Review, 2(1), 152–161. [CrossRef]

- Ammani, A. A. (2012). An Investigation into the Relationship between Agricultural Production and Formal Credit Supply in Nigeria. International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 2(1), 46–52. [CrossRef]

- An, L., & Reimer, J. J. (2021). The US market for agricultural labor: Evidence from the National Agricultural Workers Survey. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(3), 1125-1139. [CrossRef]

- Anigbogu, T. U., Agbasi, O. E., & Okoli, I. (2015). Socioeconomic Factors Influencing Agricultural Production among Cooperative Farmers in Anambra State, Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Economics and Management Sciences, 4(3), 43–58. [CrossRef]

- Anyichie-Odis, A. I. (2023). Commentary: Highlighting the need for pesticides safety training in Nigeria: A survey of farm households in Rivers State. Frontiers in Public Health. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.988855/full.

- Anyiro, C. O., Emerole, C. O., Osondu, C. K., Udah, S. C., & Ugorji, S. E. (2013). Labour-use efficiency by smallholder yam farmers in abia state nigeria: a labour-use requirement frontier approach. International Journal of Food and Agricultural Economics (IJFAEC), 1(1), 151–163. [CrossRef]

- Anyoha, N. P. O., Udemba, C., Ogbonnaya, A., & Okoroma, E. (2023). Causes of cassava post-harvest losses among farmers in Imo State, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Extension, 27(2), 73-79.

- Ashiegbu, G., Man, N., Sharifuddin, J., Buda, M., & Adesope, O. M. (2024). Impacts of Climate Variability on Agricultural Activities and Availability of Agroforestry Practices in Southeast Nigeria. Journal of Global Innovations in Agricultural Sciences, 613–623. [CrossRef]

- Asiegbu, O. V., Ezekwe, I. C., & Raimi, M. O. (2022). Assessing pesticides residue in water and fish and its health implications in the Ivo river basin of South-eastern Nigeria. MOJ Public Health, 11(2), 136–142. [CrossRef]

- Aspects of integrated pest management. (2024). Indian Scientific Journal of Research in Engineering and Management, 08(06), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Ayoade, J. A., & Adeola, A. O. (2008). Constraints to domestic industrialization of cassava in Osun State, southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment, 6(2–3), 158–161.

- Ayodeji, A. O., Rauf, A. J., Joshua, Y., Fapojuwo, O. E., & Alabi, S. O. (2021). Constraints to women’s empowerment in agriculture in rural farming areas in Oyo State, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Extension, 26(1), 86-91. [CrossRef]

- Baccaro, L., & Hadziabdic, S. (2024). Operationalizing growth models. Quality & Quantity, 58(2), 1325-1360. [CrossRef]

- Baccaro, L., & Pontusson, J. (2022). The politics of growth models. Review of Keynesian Economics, 10(2), 204-221. [CrossRef]

- Baccaro, L., & Pontusson, J. (2023). The politics of growth models. In Varieties of Capitalism (pp. 76-93). Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Bag, A., Ray, S., & Pal, M. K. (2021). Is productivity growth in the manufacturing sector a driving force toward mitigating global recession? A cross-country explanation from panel data: 1990–2018. In A. Bag, S. Ray, & M. K. Pal (Eds.), Productivity Growth in the Manufacturing Sector: Mitigating Global Recession (pp. 3-15). Emerald Publishing Limited. [CrossRef]

- Bagin, M. (2022). Theoretical and methodological principles of evaluating the efficiency of agricultural land use. Innovation and Sustainability, 4, 180-185. [CrossRef]

- Baier, S. L., Dwyer, G. P., Jr., & Tamura, R. (2002). How important are capital and total factor productivity for economic growth? (Working Paper No. 2002-2a). Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA. [CrossRef]

- Balana, Bedru B.; and Fasoranti, Adetunji S. (2022). A historical review of fertilizer policies in Nigeria. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2145. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). [CrossRef]

- Ball, V. E., Bureau, J.-C., Nehring, R., & Somwaru, A. (1997). Agricultural productivity revisited. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79(4), 1045-1063. [CrossRef]

- Bamigboye, F. O., & Ademola, E. O. (2019). Internet of Things: The present status, future impacts and challenges in Nigerian agriculture. In L. Strous & V. Cerf (Eds.), Internet of things: Information processing in an increasingly connected world (IFIPIoT 2018, IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, Vol. 548, pp. 211–217). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Barthelemy D., David J. (eds) (2001): Production Rights in European Agriculture. INRA Editions, Elsevier, Amsterdam: 197.

- Begho, T., & Ogisi, O. D. (2014). Bayes Approach to the Estimation of Technical Efficiency and Returns to Scale in Agriculture: A Case of Nigeria. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics and Sociology, 3(4), 275–284. [CrossRef]

- Belokopytov, A. V., Moskaleva, N. V., Matveeva, E., & Shevtsova, T. (2022). Management and rational use of land resources in agriculture. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 979(1), 012022-012022. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E. O., Ola, O., Lang, H., & Buchenrieder, G. (2021). Public-private cooperation and agricultural development in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review of Nigerian growth enhancement scheme and e-voucher program. Food Security, 13(1), 129–140. [CrossRef]

- Bergeaud, A., Cette, G., & Lecat, R. (2017). Total factor productivity in advanced countries: A long-term perspective. International Productivity Monitor, (32), 6-24.

- Bhuvana, N., Srinivasa, A. K., & Shankara, M. H. (2024). Information and communication technology in agriculture. In Futuristic Trends in Social Sciences (Vol. 3, Book 7, pp. 1–15). IIP Series. [CrossRef]

- Billault, A. (2023). Adam Smith as a historian of economic thought. Proceedings of the International Conference on Economic History, 35-47. [CrossRef]

- Boguslavskay, S. (2020). Structure of production and economic potential of the region. Economics, Finance and Management Review, 2, 16–22. [CrossRef]

- Botnaryuk, M. V., & Ksenzova, N. N. (2023). Cobb-Douglas production function for evaluating seaport activity. Scientific Problems of Water Transport, (74), 85-95. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, İ., & Kaya, M. V. (2021). Agricultural production index: International comparison. Agricultural Economics-Zemedelska Ekonomika, 67(6), 236-245. [CrossRef]

- Breure, T. S., Estrada-Carmona, N., Petsakos, A., Gotor, E., Jansen, B. R., & Groot, J. (2024). A systematic review of the methodology of trade-off analysis in agriculture. Nature Food, 5, 211-220. [CrossRef]

- Building Nigeria’s Response to Climate Change (BNRCC) Project. (2011). National adaptation strategy and plan of action on climate change for Nigeria (NASPA-CCN). Federal Ministry of Environment, Special Climate Change Unit. Retrieved from https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/nig211219.pdf.

- Castro, N. R., Barros, G. S. C., Almeida, A. N., Gilio, L., & Morais, A. C. P. (2020). The Brazilian agribusiness labor market: Measurement, characterization and analysis of income differentials. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, 58(1), e192298. [CrossRef]

- Cayssials, G., & Picasso, S. (2020). The Solow-Swan model with endogenous population growth. Journal of Dynamics and Games, 7(3), 197-208. [CrossRef]

- CBN (2010). Central Bank of Nigeria: Statistical Bulletin, 2010 Edition.

- Central Bank of Nigeria. (2016, December). Anchor Borrowers’ Programme guidelines. Development Finance Department. Retrieved from https://www.cbn.gov.ng/out/2017/dfd/anchor%20borrowers%20programme%20guidelines%20-dec%20%202016.pdf .

- CGIAR. (2023). Seed Equal Initiative. Retrieved from https://www.cgiar.org/initiative/seed-equal/.

- Chaubey, V., Sharanappa, D. S., Mohanta, K. K., Mishra, V. N., & Mishra, L. N. (2022). Efficiency and productivity analysis of the Indian agriculture sector based on the Malmquist-DEA technique. Universal Journal of Agricultural Research, 10(4), 331-343. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R. P., & Yee, Y. (1964). The mechanics of agricultural productivity and economic growth. Journal of Farm Economics, 46(5), 1051-1061.

- Chukwunweike, A. B. (2023). Critical analysis of factors affecting land use allocation in delta state, Nigeria 2012-2022. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 10(1), 941-950. [CrossRef]

- Chyrak, I. (2022). David Ricardo – recognized leader in classical political economy (to the 250th anniversary of his birth). The Herald of Economics, 1, 171-190. [CrossRef]

- Clark, G. (2014). The Industrial Revolution. Research Papers in Economics, 2, 217-262. [CrossRef]

- CNBC Africa. (2024). Will Nigeria’s high interest rate impact investment in agriculture sector?. Retrieved from https://www.cnbcafrica.com/media/6349873096112/will-nigerias-high-interest-rate-impact-investment-in-agriculture-sector/.

- Crafts, N. (2021). Understanding productivity growth in the Industrial Revolution. The Economic History Review, 74(2), 309-338. [CrossRef]

- Crafts, N., & O’Rourke, K. H. (2014). Twentieth Century Growth. In P. Aghion & S. N. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth (Vol. 2, pp. 263-346). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Creel, J., & Iacopetta, M. (2015). Macroeconomic policy and potential growth. Sciences Po publications, 1-32.

- Cretu, S., & Lupu, M. L. (2020). Opportunities for the development of public administration by measuring labor productivity. In S. L. Fotea, I. Ş. Fotea, & S. A. Văduva (Eds.), Challenges and opportunities to develop organizations through creativity, technology and ethics (pp. 135-142). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Crush, J., 2013. Linking food security, migration and development. International Migration, 51(5), 61-75. [CrossRef]

- Cutanda, A. (2022). The elasticity of substitution and labor-saving innovations in the Spanish regions. Estudios de Economía, 49(2), 123-144. [CrossRef]

- Dahiru, M., & Ayiwulu, E. (2025). Sustainable Land Management for Enhanced Environmental Sustainability and Productivity amongst Resource-Poor Farmers in Nigeria. African Journal of Environment and Natural Science Research, 8(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Dang, T. N. Y., Nguyen, T. H., & Dao, T. T. A. (2023). The impact of capital investments on firm financial performance – Empirical evidence from the listed food and agriculture companies in Vietnam. Vietnam Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 6(1), 1735-1744. [CrossRef]

- Darku, A. B., Malla, S., & Tran, K. C. (2013). Historical review of agricultural productivity studies (pp. 1-51). Technical Report. Department of Economics, University of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3522.4803.

- David, B. C., Tutuwa, J. A., Tadawu, R. H., Jesse, P. S., Ogu, E. O., Sunday, O. G., Nuhu, I., & Haruna, P. G. (2023). Investigation of Organochlorines Residue in Stored Cereals from Some Selected Markets in Jalingo, Nigeria. International Journal of Education, Culture, and Society, 2(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- DeBoe, G. (2020). Impacts of agricultural policies on productivity and sustainability performance in agriculture: A literature review. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 141. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- DeVries, J., & Toenniessen, G. (2001). Securing the harvest: Biotechnology, breeding, and seed systems for African crops. CABI Publishing. https://books.google.pl/books?id=b5iL6da4QmcC.

- Diewert, W. E., & Fox, K. J. (2019). Productivity indexes and national statistics: Theory, methods and challenges. Research Papers in Economics, 707-759. [CrossRef]

- Djambaska, E., Lozanoska, A., & Piperkova, I. (2022). Productivity as a source of economic growth - current situation and prospect in the Republic of North Macedonia. Economic Development, 24(2), 31-45. [CrossRef]

- Dontsop Nguezet, P. M., Okoruwa, V. O., Adeoti, A. I., & Adenegan, K. O. (2012). Productivity Impact Differential of Improved Rice Technology Adoption Among Rice Farming Households in Nigeria. Journal of Crop Improvement, 26(1), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Dorosh, P. A., & Malek, M. (2016). Rice imports, prices, and challenges for trade policy. In P. A. Dorosh & M. Malek (Eds.), The Nigerian rice economy (Chapter 7). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Dutse, F., Egwuma, H., Dodo, E. Y., Danladi, E. B., & Iliya, D. (2024). Assessment of female youth participation in agricultural livelihood generating activities in Gwagwalada Area Council, Abuja, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Economics, Environment and Social Science, 10(2), 169–179. [CrossRef]

- Dykas, P., Tokarski, T., & Wisła, R. (2023). The Solow model of economic growth: Application to contemporary macroeconomic issues. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Dziurakh, Y. (2022). Essence and classification of investments as a financial and economic category. Наукoві записки (Scientific Notes), 1(25(53)), 87-94. [CrossRef]

- Effiong, M. O. (2010). Variability of climate parameters and food crop yields in Nigeria: A statistical analysis (2010–2023). Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(16), 9321. [CrossRef]

- Egun, A. C. (2009). Focusing Agricultural Education for Better Productivity in Nigeria in the 21st Century. International Journal of Embedded Systems, 1(2), 87–90. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=cdb702d2c2e630f5d7d8c8b2240cdb760c88cb87.

- Eheazu, C. L. (2023). Promoting Conservation Agriculture in Rural Nigeria: Relevance of Environmental Literacy Education. International Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development Studies, 10(1), 16–37. [CrossRef]

- Ekakitie, G. W., & Enakireru, E. O. (2024). Redressing the challenges of unsustainable utilization of forestry resources in nigeria. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 12(12), e4234. [CrossRef]

- Eneji, R. I., & Akwaji, F. (2018). Evolution, Strategies and Problems of Poverty-Alleviating Agricultural Policies and Programmes in Nigeria. Advances in Applied Sociology, 8(12), 699–720. [CrossRef]

- Erondu, C. I., & Nwakanma, E. (2025). Human Security and Environmental Crisis in Nigeria: Addressing Interconnected Threats to Sustainable Development. African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research, 8(1), 85–96. [CrossRef]

- Eslake, S. (2011). Productivity: The lost decade [Paper presentation]. Reserve Bank of Australia Annual Policy Conference, HC Coombs Conference Centre, Kirribilli, Sydney.

- Evteev, S. R. (2023). On the issue of evaluation and analysis of labor productivity. Učenye zapiski Rossijskoj Akademii predprinimatelʹstva. Rolʹ i mesto predprinimatelʹstva v èkonomike Rossii, 22(1), 9-14. [CrossRef]

- Fabbe, K., Khanna, T., Elkins, C. M., Gillman, Z., Kyrkopoulou, E., & Teodorovicz, T. (2021). Babban Gona: Great Farm (Revised December 2022). Harvard Business School Case 722-027. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=61490.

- Fabina, J., & Wright, M. L. J. (2013). Where has all the productivity growth gone? Chicago Fed Letter, No. 306, January 2013. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/a/fip/fedhle/y2013ijann306.html.

- FAO. (2016). AQUASTAT Country Profile – Nigeria (p. 10). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy.

- FAO. (2018). Nigeria: Small family farms country factsheet. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8ce31a78-2848-4388-87a9-a3b1abb73e40/content.

- FAO. (2020). World Food and Agriculture - Statistical Yearbook 2020. Rome. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2022). RuLIS – Rural Livelihoods Information System. In: FAO. Rome. Cited March 2022. https://www.fao.org/in-action/rural-livelihoods-dataset-rulis/data-application/data/by-indicator/en.

- FAO. (2023). Capital stock. In: FAOSTAT. Rome. [Cited December 2023]. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/CS.

- FAO. (2025). Climate-smart agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture/en/.

- FAOSTAT (2019): Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/defult.aspx//ancor.

- Fariati, W.T. (2022). Pengaruh pengawasan, disiplin, dan motivasi kerja terhadap produktivitas kerja pegawai Toserba Yogya Sukabumi. Jurnal Bisnis & Birokrasi: Jurnal Ilmu Administrasi dan Organisasi, 5(2), 97-116. [CrossRef]

- Fawole, B. E., & Aderinoye-Abdulwahab, S. A. (2021). Farmers’ adoption of climate smart practices for increased productivity in Nigeria. In N. Oguge, D. Ayal, L. Adeleke, & I. da Silva (Eds.), African handbook of climate change adaptation (pp. 495–508). Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, S., Kanth, R. H., Singh, P., & Baba, Z. A. (2024). Conservation Agriculture is a Sustainable Approach for Future. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics and Sociology, 42(7), 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Fedrets, O. V., Stovba, V. O., & Solodchuk, T. V. (2022). The essence and features of formation of the management system of production capacity of the enterprise. Economics and Management of Enterprises, 1(13), 74-79. [CrossRef]

- FMARD (Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development). 2010. “ECOWAP/CAADP Process: National Agricultural Investment Plan (NAIP) 2010–2013.” http://www.inter-reseaux.org/IMG/pdf_NATIONAL_AGRIC-_INVEST-_PLAN_FINAL_AUG17.pdf.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2025). Smallholders Data Portrait. Family Farming Knowledge Platform. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/family-farming/data-sources/dataportrait/farm-size/en.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2020). Time to scale up and support Africa’s Great Green Wall. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/Time-to-scale-up-and-support-Africa-s-Great-Green-Wall/en.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2019). FAO trains farmers on use and handling of agrochemicals. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/nigeria/news/detail-events/en/c/1234859/.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2019). Integrated pest management. In Pest and pesticide management. FAO. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/pest-and-pesticide-management/ipm/integrated-pest-management/en/.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2023). Agricultural investments and capital stock 2012–2022: Global and regional trends (FAOSTAT Analytical Brief 75). Rome: FAO. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2024, May 28). FAO conducted training on reducing pesticide use and related risks. FAO. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/countryprofiles/news-archive/detail-news/en/c/1697497/ .

- Forteza, F. J., Carretero-Gómez, J. M., & Sesé, A. (2017). Effects of organizational complexity and resources on construction site risk. Journal of Safety Research, 62, 185–198. [CrossRef]

- Gaddis, Isis, Rahul Lahoti, and Wenjie Li. (2018). “Gender Gaps in Property Ownership in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Policy Research Working Paper 8573, World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Gallardo, R. K., & Sauer, J. (2018). Adoption of labor-saving technologies in agriculture. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 10(1), 185-206. [CrossRef]

- Galor, O., & Özak, Ö. (2015). Land productivity and economic development: Caloric suitability vs. agricultural suitability. Anthropology of Agriculture & Nutrition eJournal. [CrossRef]

- Gandy, R., & Mulhearn, C. (2021). Allowing for unemployment in productivity measurement. SN Business & Economics, 1(1), 10-38. [CrossRef]

- Gangotena, S. J., & Safner, R. (2021). A tale of two capitals: Modeling the interaction between ideas, physical capital, and growth. Social Science Research Network. [CrossRef]

- Gensch, L., Jantke, K., Rasche, L., & Schneider, U. A. (2024). Pesticide risk assessment in European agriculture: Distribution patterns, ban-substitution effects and regulatory implications. Environmental Pollution, 348, 123836. [CrossRef]

- George, T., Bagazonzya, H. K., Ballantyne, P. G., Belden, C., Birner, R., Castello, R. del, Castren, T., Choudhary, V., Dixie, G., Donovan, K., Edge, P., Hani, M., Harrod, J., Jamsen, P., Jantunen, T., Jayaraman, N., Maru, A., Majumdar, S., Manfre, C., … Treinen, S. (2011). ICT in agriculture: Connecting smallholders to knowledge, networks, and institutions (pp. 1–428). Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/455701468340165132.

- Gidanmana, U. P. (2020). Transforming Nigeria’s Agricultural Value Chain. World Journal of Innovative Research (WJIR), 9(3),6-12. [CrossRef]

- Gidanmana, U. P. (2020). Transforming Nigeria's agricultural value chain. World Journal of Innovative Research (WJIR), 9(3), 6–12. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D., & Vaughan, R. (2011). The historical role of the production function in economics and business. American Journal of Business Education, 4(4), 25-30. [CrossRef]

- Graskemper, V. (2021). Entrepreneurship in agriculture – Farmer typology, determinants and values (Doctoral dissertation, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen). [CrossRef]

- Gu, S., Zheng, L., & Yi, S. (2007). Problems of rural migrant workers and policies in the new period of urbanization. China Population, Resources and Environment, 17(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Gulaiya, S., Singh, S., Kaur, R., Joshi, M., Gautam, K. K. S., Adhikari, A. V., Yadav, K., Goyal, S., Kumar, R., & Kakkar, P. H. (2025). A Review on Conservation Agriculture: Challenges, Opportunities and Pathways to Sustainable Farming. Journal of Scientific Research and Reports, 31(1), 97–107. [CrossRef]

- Hamzat, L. (2019, June 19). Great Green Wall: Key to Nigeria’s greatness. EnviroNews Nigeria. Retrieved January 11, 2025, from https://www.environewsnigeria.com/great-green-wall-key-to-nigerias-greatness/.

- Hatzenbuehler, P. L., Mavrotas, G., & Amare, M. (2023). Differences in peri-urban and rural farm production decisions amid policy change in Nigeria. World Development Perspectives, 32, 100541. [CrossRef]

- Higham, C. F. W. (2023). The impact of physical capital and human capital (level of education) on growth in Indonesia. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Pembangunan, 30(2), 115-130. [CrossRef]

- Hnatkivskyi, B. M. (2021). Theoretical approaches to understanding the potential of economic growth of agricultural business entities. Ukrainian Journal of Applied Economics, 6(1), 400-406. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E. S., Nendel, C., Ajayi, A. E., Berg-Mohnicke, M., & Schulz, S. (2025). Simulating and mapping the risks and impact of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) and white grub (Holotrichia serrata) in maize production outlooks for Nigeria under climate change. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 385, 109534. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H. K., Hendriks, S. L., & Schönfeldt, H. C. (2023). The effect of land tenure across food security outcomes among smallholder farmers using a flexible conditional difference-in-difference approach. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S. S., & Aliero, H. M. (2012). An analysis of farmers’ access to formal credit in the rural areas of Nigeria. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 7(47), 6249-6253. [CrossRef]

- Igwe, C. F. (2015). Observations on the Spatial Patterns of Agricultural Production in Nigeria. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 5(10), 42–45. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234661033.pdf.

- Ikenwa, K. O., Sulaimon, A.-H. A., & Kuye, O. L. (2017). Transforming the Nigerian Agricultural Sector into an Agribusiness Model – the Role of Government, Business, and Society. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae: Economics and Business, 5(1), 71–115. [CrossRef]

- Ikoyo-Eweto, G. O. (2022). Adoption of information and communication technologies in enhancing food security among small-scale farmers in Delta State, Nigeria. Journal of Agripreneurship and Sustainable Development, 5(3), 141–151. [CrossRef]

- Ilesanmi, J. O., Bello, T. O., Oladoyin, O. P., & Akinbola, A. E. (2024). Evaluating the Effect of Microcredit on Rural Livelihoods: A Case Study of Farming Households in Southwest Nigeria. International Journal of Economic, Finance and Business Statistics, 2(5), 289–302. [CrossRef]

- Imoloame, E. O., Yusuf, O. J., Abdulra’uf, L. B., & Aliyu, T. H. (2024). Integrated pest management practices and pesticide residue in okra among farmers in Kwara State. [CrossRef]

- Imran, S., Salim, S. V., & Adam, E. (2023). Optimization the use of production factors and rice farming income. Jambura Agribusiness Journal, 4(2), 48-58. [CrossRef]

- Iniodu, P. U. (2002). Appropriate technology for sustainable agriculture in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Discovery and Innovation, 14 (1), 119–129. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/dai/article/view/15432.

- International Crisis Group. (2014, April 3). Curbing violence in Nigeria (II): The Boko Haram insurgency (Africa Report No. 216). https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/curbing-violence-nigeria-ii-boko-haram-insurgency.

- International Fertilizer Organization (IFA). (2022). Precision Agriculture - Improving nutrient use efficiency with precision agriculture. Retrieved from https://www.fertilizer.org/science/innovation/precision-agriculture/.

- Iootty, M., Bizhan, A., & Correa, P. G. (2022). Policy Diagnosis and Recommendations. In M. Iootty, A. Bizhan, & P. G. Correa (Eds.), Boosting Productivity in Kazakhstan with Micro-Level Tools: Analysis and Policy Lessons (pp. 23-60). International Development in Focus. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1910-0_ch3.

- Ismaila, U., Gana, A. S., Tswanya, N. M., & Dogara, D. (2010). Cereals production in Nigeria: Problems, constraints and opportunities for betterment. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 5(12), 1341–1350. https://academicjournals.org/journal/AJAR/article-full-text-pdf/89BF94F35305.pdf.

- Ivanova, O., & Chatzouz, M. (2019). Sectoral productivity growth and innovation policies. Research Papers in Economics. University Library of Munich, Germany. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/93488/1/MPRA_paper_93488.pdf (accessed on 07 July 2024).

- Iye, E. L., & Bilsborrow, P. E. (2013). Assessment of the availability of agricultural residues on a zonal basis for medium- to large-scale bioenergy production in Nigeria. Biomass & Bioenergy, 48, 66–74. [CrossRef]

- Jauhari, S., Minarsih, S., Hindarwati, Y., Pramono, J., Susila, A., Sudarto, S., Basuki, S., Hariyanto, W., Utomo, B., Suhendrata, T., Oelviani, R., Arianti, F. D., Supriyo, A., Aristya, V. E., & Samijan, S. (2025). Rice yield enhancement and environmental sustainability with precision nutrient management. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 11(1), 77-92. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. E., Takeshima, H., Gyimah-Brempong, K., & Kuku-Shittu, O. (2013). Policy options for accelerated growth and competitiveness of the domestic rice economy in Nigeria (NSSP Policy Note 35). International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://hdl.handle.net/10568/153649.

- Juhász, R., Juhász, R., Juhász, R., Squicciarini, M. P., Voigtländer, N., Voigtländer, N., & Voigtländer, N. (2020). Technology adoption and productivity growth: Evidence from industrialization in France. NBER Working Paper Series. Working Paper 27503. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved July 9, 2020, from Social Science Research Network website: https://doi.org/10.3386/W27503.

- Kakwagh V.V.; Aderonmu J.A. & Ikwuba A. (2011). Land Fragmentation and Agricultural Development in Tivland of Benue State, Nigeria. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences, 3(2), pp. 54-58.

- Kamińska, W. (2016). Poziom wykształcenia zasobów wiejskiej siły roboczej w Polsce. Analiza przestrzenna. Studia Obszarów Wiejskich, 41, 9-30. [CrossRef]

- Kareem, F. O., Martínez-Zarzoso, I., & Brümmer, B. (2022). What drives Africa’s inability to comply with EU standards? Insights from Africa’s institution and trade facilitation measures. European Journal of Development Research, 35(4), 938–973. [CrossRef]

- Kareem, R. O. (2015). Agricultural Development and Political Economy: A Review of the Nigerian Experience.

- Kareem, R. O., Bakare, H. A., Raheem, K. A., Ologunla, S. E., Alawode, O. O., Ademoyewa, G. R., & Bakare, R. O. (2013). Analysis of factors influencing agricultural output in Nigeria: Macro-economics perspectives. 1(1), 9.

- Kareska, K. (2025). Challenges and Strategic Solutions for Sustainable Agriculture. Social Science Research Network. [CrossRef]

- Koshkalda, I., Iukhno, A., Stupen, N., Dorozhko, Y., & Muzyka, N. (2023). Management of land resources with consideration of agricultural land zoning indices. Review of Economics and Finance, 21, 343-350. [CrossRef]

- Kreneva S., Halturina E., Larionova T., Shvetsov M., Tereshina V. (2015): Influence of factors of production on efficiency of production systems. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6: 411–418.

- Kumar, A., Vikanksha, Singh, J. (2025). Integrated pest management through biological control. In The role of entomopathogenic fungi in agriculture (1st ed., pp. 54–76). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L. (2017). Productiveness vs productivity. Management Dynamics, 17(2), 70-79. Article 7. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Tiwari, P., Daniel, S., Kumar, K. R., Mishra, I., KS, A., & Shah, D. G. (2024). Agroforestry Systems: A Pathway to Resilient and Productive Landscapes. International Journal of Enviornment and Climate Change, 14(12), 177–193. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Singh, D. R., Singh, N. P., Jha, G. K., & Kumar, S. (2022). Impact of natural resource conservation technology on productivity and technical efficiency in rainfed areas of Southern India. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 67(2), 356–377. [CrossRef]

- Kurz, H. (2022). Malthus and the Classics (Not Walras and the Marginalists) as the major inspiring source in the history of economic thought. In The Principle of Effective Demand and Classical Economics (pp. 50-78). [CrossRef]

- Kuye, O. O., James, E. U., & Oniah, M. O. (2008). Policy Priorities in Rural Women Empowerment Sustainability, Poverty and Food Security in Nigeria. Journal of Agriculture, Forestry and the Social Sciences, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- Lanz, B., Dietz, S., & Swanson, T. (2018). Global economic growth and agricultural land conversion under uncertain productivity improvements in agriculture. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100(2), 545-569. [CrossRef]

- Latopa, A.-L. A., & Rashid, S. N. S. A. (2015). The Impacts of Integrated Youth Training Farm as a Capacity Building Center for Youth Agricultural Empowerment in Kwara State, Nigeria. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(5), 524. [CrossRef]

- Latruffe L. (2010): Competitiveness, productivity and efficiency in the agricultural and agri-food sectors. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Working Papers, No. 30. OECD Publishing.

- Lemishko, O. O. (2022). Eculiarities of capital formation process in agriculture. Conference Proceedings “Competitiveness and Sustainable Development”, 185. [CrossRef]

- Lencucha, R., Pal, N. E., Appau, A., Thow, A. M., & Drope, J. (2020). Government policy and agricultural production: A scoping review to inform research and policy on healthy agricultural commodities. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Letseku, V., & Grové, B. (2022). Crop water productivity, applied water productivity and economic decision making. Water, 14(10), 1598. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-h., Xiong, W., Duan, W., & Xiong, Y. (2023). Evaluation on substitution of energy transition—An empirical analysis based on factor elasticity. Frontiers in Energy Research, 10. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y., Sun, P., Tang, R., & Zhang, C. (2022). Efficient resource allocation contracts to reduce adverse events. Operations Research. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberg, E. (2025). Economics of pesticide use and regulation. In T. Lundgren, M. Bostian, & S. Managi (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Energy, Natural Resource, and Environmental Economics (Second Edition) (Vol. 3, pp. 59-73). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Liverpool-Tasie, L. S. O., Omonona, B. T., Sanou, A., & Ogunleye, W. (2016). Fertilizer use and farmer productivity in Nigeria: The way forward – A reflection piece [Guiding Investments in Sustainable Agricultural Intensification in Africa (GISAIA)]. AgEcon Search. Retrieved from https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/234952/files/Reflection_piece_NigeriaFINAL.pdf.

- Lovell, C. A. K. (2016). Recent developments in productivity analysis. Pacific Economic Review, 21(4), 417-444. [CrossRef]

- Lubis, A. Z., Setiawan, B. M., & Prasetyo, E. (2021). Analysis of efficiency of use of production factors in rice farming polluted and unpolluted by slaughterhouses waste in Penggaron Kidul Semarang. HABITAT, 32(1), 17–25. [CrossRef]

- Macrotrends. (2025). Nigeria arable land 1961-2025. Retrieved 03/19/2025, from https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/nga/nigeria/arable-land.

- Mahanto, S., Chattopadhyay, R., Kundu, S., & Kanthal, S. (2024). Precision farming: Innovations, techniques and sustainability. International Journal of Agriculture Extension and Social Development, 7(4), 42-47 https://doi.org/10.33545/26180723.2024.v7.i4a.513.

- Mahtaney, P. (2021). The link between productivity and economic progress: Issues and insights. In Structural Transformation (pp. 17-37). Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Maklakova, E., Sysoev, M. (2022). Comparison of views of Adam Smith, Alfred Marshall, David Ricardo. In Materials of the International Scientific and Practical Forum "Manager of the Year" (pp. 157-161). [CrossRef]

- Marks-Bielska, R. (2022). Agricultural land as a public good. Scientific Papers of SGGW, European Policies, Finance and Marketing, 28(77), 119-128. [CrossRef]

- Martins, G., Ehinmentan, B., Mafimisebi, P., America, A., & Gbadero, G. (2024). Sustainable water resource management in nigeria: challenges, integrated water resource management implementation, and national development. International Journal of Trendy Rresearch in Engineering and Technology, 09(01), 08–16. [CrossRef]

- Maryam, K., Gladys, A. A., Nabieu, D. O.-S., & Baah, A. K. (2021). Entrepreneurship and agriculture resources on national productivity in Africa: Exploring for complementarities, synergies and thresholds. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 15(5), 643-664. [CrossRef]

- Matyja M. (2016): Resources based factors of competitiveness of agricultural enterprises. Management, 20: 368–381.

- Mbaya, H., Lillico, S. G., Kemp, S., Simm, G., & Raybould, A. (2022). Regulatory frameworks can facilitate or hinder the potential for genome editing to contribute to sustainable agricultural development. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, K. R., Bru, S. L. (1992). Economics: Principles, industry, and politics. Republic of Moscow.

- McMillan, M. S., Harttgen, K. (2014). What is driving the 'African Growth Miracle'? (No. w20077). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- McMillan, M., Rodrik, D., Verduzco-Gallo, Í. (2014). Globalization, structural change, and productivity growth, with an update on Africa. World development, 63, 11-32.

- Mejía-Matute, S. R., Pinos-Luzuriaga, L. G., Tonon-Ordóñez, L. B. (2023). Función de producción Cobb-Douglas: Una revisión bibliográfica. Revista Economía y Negocios (UTE - En línea), 14(2), 74-95. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N. (2024). Assessment of the Use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in Agricultural Extension Service Delivery among Farmers in Yobe State, Nigeria. International Journal of Smart Agriculture, 2(1), 11–19. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S. D., Suleiman, N. A., Olamide, B. S., Olamide, K. M., & Yusuf, M. O. (2024). The Contribution of Value Added Tax to Federally Collected Revenue in Nigeria: A trend Analysis 1994-2022. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square, pp 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, A., & Baba, Y. T. (2018). Herdsmen-farmers’ conflicts and rising security threats in Nigeria. Studies in Politics and Society (Thematic Edition), 7(1), 1-20.

- Murray, A., & Sharpe, A. (2016). Partial versus total factor productivity: Assessing resource use in natural resource industries in Canada (No. 2016-20). Centre for the Study of Living Standards. Prepared for the Smart Prosperity Institute.

- Musa, H. A. (2021). Economic Diversification and Export Growth: The Role of Agriculture in Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Allied Research, 3(2), 12-25.(Available at: https://jearecons.com/index.php/jearecons/article/view/156).

- Naik, I. G., & Navaneetham, B. (2024). Impact of ICT on Productivity, Market Access, and Risk Management in Agriculture. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(5), 2264–2271. [CrossRef]

- Nalluri, N., & Karri, V. R. (2023). Superior effect of nature based solutions in soil and water management for sustainable agriculture. Plant Science Today. [CrossRef]

- Nara, B. B., Lengoiboni, M., & Zevenbergen, J. A. (2021). Testing a fit-for-purpose (FFP) model for strengthening customary land rights and tenure to improve household food security in Northwest Ghana. Land use policy, 109, 105646.

- Naswem, A. A., Okwoche, V. A., & Age, A. I. (2016). Mainstreaming sustainability in the Nigerian agricultural transformation agenda. World, 3(1), 054-059. http://premierpublishers.org/wrjas/180420161152.

- National Emergency Management Agency. (2024). 2024 Floods National Emergency Operations Center (NEOC) National Secretariat situation report: No. 4 (as at 22nd October, 2024). Retrieved from https://nema.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/SitRep-No-4-221024.pdf.

- Naumenko, A., & Moosavian, S. A. Z. N. (2016). Clarifying theoretical intricacies through the use of conceptual visualization: Case of production theory in advanced microeconomics. Applied Economics and Finance, 3(4), 103-122. [CrossRef]

- Nnanna, I., & Arua, J. E. (2022). Productivity improvement through work study techniques: A case of a modern rice mill in Ikwo, Ebonyi State. Journal of Engineering Research and Reports, 23(12), 193-203. [CrossRef]

- Novichenko, L. (2022). Labor productivity: Analysis of indicators and increase reserves. International Scientific Journal "Internauka," Series: "Economic Sciences," 3(59). [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A., & Różańska-Boczula, M. (2019). Differentiation in the production potential and efficiency of farms in the member states of the European Union. Agricultural Economics – Czech, 65(9), 395–403. [CrossRef]

- Nuhu, T., & Kawu, Y. U. (2024). Assessment of sheep production practices and constraints in Yobe State, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Animal Production, 51(1), 85–94.

- Nura, A.Y. (2022). Spatial technology adoption amongst African Development Bank community based agriculture and rural development programme beneficiaries in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Agriculture and Agricultural Technology, 2(1), 78–92. [CrossRef]

- Nwanojuo, M. A., Anumudu, C. K., & Onyeaka, H. (2025). Impact of Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) in Nigeria, a Review of the Future of Farming in Africa. Agriculture, 15(2), 117. [CrossRef]

- Nwoko, C. O., Umeohana, S., Anyanwu, J., Izunobi, L., & Peter-Onoh, C. A. (2024). Carbon Stock Assessment of Four Selected Agroforestry Systems in Owerri-West Local Government Area, Nigeria. International Journal of Enviornment and Climate Change, 14(3), 207–216. [CrossRef]

- Nyambo, P., Malobane, M. E., Nciizah, A. D., & Mupambwa, H. A. (2024). Strengthening Crop Production in Marginal Lands Through Conservation Agriculture: Insights from Sub-Saharan Africa Research (pp. 97–111). [CrossRef]

- Nyanda, S. S., & Gbigbi, T. M. (2024). Unlocking the Potential of Agriculture through Land Tenure Security: Lessons from Delta State, Nigeria. 3(1), 90–104. [CrossRef]

- Obayelu, A. E., Moncho, C. M. D., & Diai, C. C. (2016). Technical efficiency of production of quality protein maize between adopters and nonadopters, and the determinants in Oyo State, Nigeria. Review of Agricultural and Applied Economics, XIX (Number 2, 2016): 29–38.http://roaae.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/10/RAAE_2_2016_Obayelu_et_al.pdf.

- Obayelu, O. A., Ajibobare, A. O., Adepoju, A. O., & Ayanboye, A. O. (2023). Youths’ Participation in Urban Agriculture in Ibadan Metropolis, Nigeria (pp. 28–40). CABI. [CrossRef]

- OECD/APO. (2022). Preface by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. In Identifying the Main Drivers of Productivity Growth: A Literature Review. OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Ogundari, K. (2009, August 16–22). A meta-analysis of technical efficiency in Nigerian agriculture [Conference paper]. International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE) 2009 Conference, Beijing, China. [CrossRef]

- Ogundari, K., Amos, T. T., & Okoruwa, V. O. (2012). A Review of Nigerian Agricultural Efficiency Literature, 1999–2011: What Does One Learn from Frontier Studies? African Development Review, 24(1), 93–106. [CrossRef]

- Ogunlela, Y. I., Mukhtar, A. A. (2009). Gender issues in agriculture and rural development in Nigeria: The role of women. Humanity & Social Sciences Journal, 4(1), 19–30. IDOSI Publications. https://www.idosi.org/hssj/hssj4(1)09/3.pdf.

- Ogunmola, O. O., Afolabi, C. O., Adesina, C. A., & IleChukwu, K. A. (2021). A comparative analysis of the profitability and technical efficiency of vegetable production under two farming systems in Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Sciences (Belgrade), 66(1), 87-104.

- Ogunniyi, A.; Babu, S.C.; Balana, B.; Andam, K.S. National Extension Policy and State-Level Implementation: The Case of Cross River State, Nigeria; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Volume 1951, Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/publication/national-extension-policy-and-state-level-implementation-case-cross-river-state-nigeria (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Ohikere, J. Z., & Ejeh, A. F. (2012). The potentials of agricultural biotechnology for food security and economic empowerment in Nigeria. Archives of Applied Science Research, 4(2), 906–913. https://www.scholarsresearchlibrary.com/articles/the-potentials-of-agricultural-biotechnology-for-food-security-and-economic-empowerment-in-nigeria.pdf.

- Ojadi, F. I. (2022). Global agricultural value chains: The case of yam export from Nigeria. In Africa and Sustainable Global Value Chains (pp. 169-193). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Ojo, A., Adeyemi, O., Kayode, F., Oyebamiji, O., Onabolu, A., Grema, A., .. & Ajieroh, V. (2023). Evidence-based design process for nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions: a case study of the advancing local dairy development programme in Nigeria. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 44(1_suppl), S27-S40.

- Ojonye, S. M., Nuga, K. A., Omotola, A. A., Philips, S. A., & Esho, O. (2019). Agricultural production and economic growth in Nigeria: A VAR approach. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 10(6), 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Ojumu, F. O., Aminu, O. O., & Oyesola, O. B. (2023). Constraints to Livestock Production among Rural Households in Southwest Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Extension, 28(1), 68-77.

- Okafor, C., Udobi, N. A. (2024). An Analysis of the Difference Between Traditional Land Tenure Systems and the Land Use Act, No 6 of 1978, Nigeria. 4(3), 90–103. [CrossRef]

- OKOH, P. A., Oladokun, A. (2024). Using digital resources in agriculture as a strategy for curbing hunger crisis in Nigeria. Nigeria Journal of Home Economics (ISSN: 2782-8131), 12(10), 116–123. [CrossRef]

- Okojie, C. E. E. (1991). Achieving Selfreliance in Food Production in Nigeria: Maximising the Contribution of Rural Women. Journal of Social Development in Africa, 6(2), 33–52. https://archive.lib.msu.edu/DMC/African%20Journals/pdfs/social%20development/vol6no2/jsda006002007.pdf.

- Okompu, D. A., Ofiaju, J. A., Dennis, A., & Otunaruke, P. E. (2025). Credit Access among Arable Crop Farmers in Ondo State, Nigeria. Implication for Agricultural Productivity Enhancement. Journal of Economics and Trade, 10(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Okunola, A. M. (2017). Capital investment: lubricant of the engine of production process in agricultural sector – evidence from Nigeria. Agricultural and Resource Economics: International Scientific E-Journal, 3(4), 20–32. https://ideas.repec.org/a/ags/areint/267892.html.

- Olomola, A. S. (2020). Evaluating the impact of agricultural input subsidy scheme on farmers' productivity, food security, and nutrition outcomes in the Northcentral and Southwest regions of Nigeria (AERC Working Paper No. BMGF-001). African Economic Research Consortium.

- Olotuah, A.O., 2005. Urbanisation, urban poverty, and housing inadequacy. In: Proceedings of Africa Union of Architects Congress, Abuja, Nigeria, pp. 185–199.

- Olu-Adeyemi, L. (2017). Federalism in Nigeria: Problems, prospects and the imperative of restructuring. International Journal of Advances in Social Science and Humanities, 5(8), 40–52. Available at https://www.ijassh.com/index.php/IJASSH/article/view/33.

- Olubunmi-Ajayi, T. S., Akinrinola, O. O., Ibrahim, A. T., & Adeyemi, I. O. (2025). Assessing Technical, Economic, and Allocative Efficiencies of Maize-Rice-Based Farmers Across Scale Economies in Southwest Nigeria. Agriculture Archives, 4(1), 01–09. [CrossRef]

- Oluwambe, T. M., & Oludaunsi, S. A. (2017). Agricultural biotechnology, the solution to food crisis in Nigeria. Advances in Plants and Agriculture Research, 6(4), 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Omokaro, G. O., Idama, V., Airueghian, E. O., & Michael, I. (2024). Water Resources, Pollution, Integrated Management and Practices in Nigeria – An Overview. American Journal of Environmental Economics, 3(1), 5–18. [CrossRef]

- Omoregje, A. U. (1990). Problems of food storage and preservation in Nigeria: An overview. Tropicultura, 8(2), 55–58.

- Onokerhoraye, A. G. (1976). The pattern of housing, Benin, Nigeria. Ekistics, 41 (No), 242.

- Orikpe, E. A., & Orikpe, G. O. (2013). Information and Communication Technology and Enhancement of Agricultural Extension Services in the New Millennium. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 3(4), 155. [CrossRef]

- Osabohien, R., Osabuohien, E., & Urhie, E. (2019). Agricultural Export and Economic Growth in Nigeria: An ARDL Approach. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 331, 012002. (Available at: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/331/1/012002). [CrossRef]

- Oshatunberu, M. A., Oladimeji, A., Sawyerr, H. O., Afolabi, O. O., Raimi, M. O. (2023). Concentrations of Pesticides Residues in Grain Sold at Selected Markets of Southwest Nigeria. Natural Resources for Human Health, 3(4), 387-402. [CrossRef]

- Osuji, E. E., Anosike, F. C., Obasi, I. O., Nwachukwu, E. U., Obi, J. N., Orji, J. E., Inyang, P., Chinaka, I. C., Osang, E. A., Iroegbu, C. S., Nzeakor, F. C., & Onu, S. E. (2023). Integration of climate smart agro-technologies and efficient post-harvest operations in changing weather conditions in Nigeria. Journal of Agriculture and Crops, 9, 281–292. [CrossRef]

- Otitoju, M. A., & Ochimana, D. D. (2016). Determinants of farmers’ access to fertilizer under fertilizer task force distribution system in Kogi State, Nigeria. Cogent Economics & Finance, 4(1), 1225347. [CrossRef]

- Otitoju, M. A., Fidelis, E. S., Otene, E. O., & Anigoro, D. O. (2023). Review of Climate Smart Agricultural Technologies Adoption and Use in Nigeria. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 7(8), 827-838. [CrossRef]

- Oyaniran, T. (2020, September). AfCFTA: Opportunities in Africa agricultural products and markets [Workshop presentation]. PwC Nigeria. https://www.pwc.com/ng/en/assets/pdf/afcfta-agribusiness-agricultural-products-and-markets.pdf.

- Oyebanjo, O., Ologbon, O. A. C., Osinowo, O. H. & Ogunaike, M. G. (2022). Labour Production Efficiency among Arable Crop Farm Households in Southwest Nigeria FUW Trends in Science and Technology Journal, 7(2), pp. 1073-1079.

- Oyegbami, A. B., Idowu, A. B., et al. (2024). Knowledge and Economic Loss of Pig Farmers to African Swine–Fever in Lagos State, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences & Environmental Management, 28(10). https://www.fao.org/nigeria/news/detail-events/en/c/1329363/.

- Oyewo, I. O., Adeoye, A. S., Adesope, A. A., Adisa, A. S., Oke, O. S., Farayola, C. O., Elesho, R. O., & Aluko, A. K. (2023). Contributive effect of land management indicators to farmers’ farmland conservation in Oyo State, Nigeria. NIU Journal of Social Sciences, 9(3), 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Özgül, M., & Çomakli, E. (2023). The strategy of utilizing unused lands for production purposes in Turkey. Turkish Journal of Range and Forage Science, 4(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Paris, A. (2010). The evolution of capital productivity in Greek manufacturing. Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal, 2(2&3), 141-161.

- Pawlewicz A., Pawlewicz K. (2018): Regional differences in agricultural production potential in the European Union Member States. In: Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference Economic Science for Rural Development, No. 47, Jelgava, LLU ESAF, May 9–11, 2018: 483–489.

- Pereira, F. L., Pena, I., & Silva, G. N. (2019). A framework for the sustainable control and optimization of resources in agriculture. In 2019 IEEE 58th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC) (pp. 2344-2349). [CrossRef]

- Pérez, H. G. de J., & Ortega, M. V. (2021). Mathematical economics in the explanation of economic growth in economies with endogenous and exogenous technological change. Revista Brasileira de Risco e Seguro, 10(5), 101-109. [CrossRef]

- Peter, B. I., & Brownson, C. D. (2022). Innovative entrepreneurship and development of SME opportunities among agricultural entrepreneurs in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. The International Journal of Business and Management, 10(6). [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, E. (2024). Exploring the synergy between lean management and the Nordic welfare state ethos: Case study of HUS (Master’s study). Aalto University. Retrieved from https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:aalto-202406234824.

- Poltavets, A. M. (2022). Strategic principles of land resources management in main activities of agrarian enterprises. Ukraïnsʹkij žurnal prikladnoï ekonomìki, 7(3), 180-185. [CrossRef]

- Poltavets, A. M. (2022). The establishment of a system of sustainable land use as a key factor of effective land resource management in the management system of agricultural enterprises. Bulletin of Khmelnytskyi National University, 312(6(2)), 278-282. [CrossRef]

- Pratama, R., Siang, I. S., & Sabirin, S. (2023). Plantation sector in Central Kalimantan Province: Optimization of production factor use. Journal Magister Ilmu Ekonomi Universitas Palangka Raya: GROWTH, 9(1), 20-27. [CrossRef]

- Pratiknyo, Y., Bangun, W., Hidayah, Z., & Kambara, R. (2023). Cobb-Douglas production in the Volterra integral equation. Asian Journal of Entrepreneurship and Family Business (AJEFB), 7(1), 11-24. [CrossRef]

- Raufu, M., Fajobi, D. T., Dlamini-Mazibuko, B. P., Miftaudeen-Raufu, A., & Olalere, J. O. (2025). Agricultural Credit Guarantee Scheme Funds and Agricultural Performance in Nigeria. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach Research and Science, 3(01), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Petrick, M. Trade-Offs among Sustainability Goals in the Central Asian Livestock Sector: A Research Review; Justus-Liebig Universitat: Giessen, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–149. [Google Scholar].

- Rymarczyk, J. (2022). The change in the traditional paradigm of production under the influence of Industrial Revolution 4.0. Businesses, 2(2), 188-200. [CrossRef]

- Sahudin, Z., & Subramaniam, G. (2023). The effects of health, labor, and capital towards labor productivity in manufacturing industries. Information Management and Business Review, 15(1(I)SI), 121-130. [CrossRef]

- Salman, K. K. (2015). Political Economy of Fertilizer Subsidy Implementation Process in Nigeria. International Journal of Innovation and Scientific Research, 19(2), 347–363. https://www.ijisr.issr-journals.org/abstract.php?article=IJISR-15-065-05.

- Samuel, S. D. (2021). Enhancement of youth involvement in agricultural extension advisory services through capacity building: a solution to unemployment in Nigeria. American International Journal of Agricultural Studies, 5(1), 22-30. [CrossRef]

- Sanou, J., Tengberg, A., Bazié, H. R., & Ostwald, M. (2023). Assessing trade-offs between agricultural productivity and ecosystem functions: A review of science-based tools? Land, 12(7), 1329. [CrossRef]

- Sarap, N. S. (2020). Use of information and communication technology in agriculture development. International Journal of Applied Research, 6(5), 462–464. https://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/?year=2020&vol=6&issue=5&part=G&ArticleId=7801.

- Secinaro, S., Dal Mas, F., Massaro, M., & Calandra, D. (2022). Exploring agricultural entrepreneurship and new technologies: Academic and practitioners' views. British Food Journal, 124(7), 2096-2113. [CrossRef]

- Shaibu, U. (2024). Agricultural Sector Policy Periods and Growth Pattern in Nigeria (1960–2020): Implications on Agricultural Performance. IntechOpen eBooks. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, N., Sankaralingam, S., & Vishal, S. (2023). Smart agriculture using modern technologies. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS) (pp. 2025-2030). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. (2023). Cultivating sustainable solutions: Integrated pest management (IPM) for safer and greener agronomy. Corporate Sustainable Management Journal, 1(2), 103-108. [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, A. I. (2022). Labor productivity as an economic category and a generalized indicator of efficiency. Social’no-trudovye issledovaniya, 48(3), 27-34. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Zhu, J., & Charles, V. (2021). Data science and productivity: A bibliometric review of data science applications and approaches in productivity evaluations. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 72(5), 975-988. [CrossRef]

- Siebers, P.-O., Aickelin, U., Battisti, G., Celia, H., Clegg, C., Fu, X., De Hoyos, R. E., Iona, A., Petrescu, A. I., & Peixoto, A. (2008). Enhancing productivity: The role of management practices. Advanced Institute of Management Research Paper No. 065. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1309605 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1309605.

- Silver, M., & Bennett, A. (1986). Potential productivity: Concepts and application. Omega-international Journal of Management Science, 14, 443-452.

- Singh, R. (2024). Assessing the Impact of Sustainable Agriculture Practices on Biodiversity Conservation. Journal of Sustainable Solutions, 1(3), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, J. K. (2023). Economies of the factors affecting crop production in India: Analysis based on Cobb-Douglas production function. Sumerianz Journal of Economics and Finance, 6(1), 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Sithole, A., & Olorunfemi, O. (2024). Sustainable Agricultural Practices in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Adoption Trends, Impacts, and Challenges Among Smallholder Farmers. Sustainability, 16(22), 9766. [CrossRef]

- Siudek T., Zawojska A. (2014): Competitiveness in the economic concepts, theories and empirical research. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum, Oeconomia, 13: 91–108.

- Šlander Wostner, S., Križanič, F., Brezovnik, B., & Vojinović, B. (2023). Total factor productivity and the significance of the public sector. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 69 E(2023), 118-132. [CrossRef]

- Sobalaje, A. J., & Adigun, G. O. (2013). Use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) by Yam Farmers in Boluwaduro Local Government Area of Osun State, Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 1018. University of Nebraska - Lincoln. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2457&context=libphilprac.

- Sørensen, C.A.G., Kateris, D., & Bochtis, D. (2019). ICT innovations and smart farming. In M. Salampasis & T. Bournaris (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in modern agricultural development: HAICTA 2017 (Vol. 953, pp. 1–19). Communications in Computer and Information Science. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Souza, T. A. A. de, Santos, H. C. Z. A., & Cunha, M. S. da. (2020). Panorama de longo prazo entre crescimento e produtividade no Brasil (1980-2014). Revista de Desenvolvimento Econômico, 1(45).

- Srinatha, T. N., Abhishek, G. J., Kumar, P., Aravinda, B. J., Baruah, D., Gireesh, S., Thakur, N., & Perumal, A. (2024). Agricultural Policy Reforms and their Effects on Smallholder Farmers: A Comprehensive Review. Archives of Current Research International, 24(6), 467–474. [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J., & Caiazza, R. (2023). Trends shaping the future of agrifood. In Agricultural Value Chains - Some Selected Issues. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Stasi, A., & Tan, W. C. D. (2023). The regulatory framework. In An introduction to legal, regulatory and intellectual property rights issues in biotechnology (pp. 24-39). [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2023). Consumption of fertilizer per area of arable land worldwide from 1966 to 2021 (in kilograms per hectare). Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1287873/global-consumption-of-fertilizer-per-area/.

- The Guardian. (2015, November 25). Anchor Borrowers’ Scheme raising stake in agric financing. The Guardian Nigeria. https://guardian.ng/business-services/money/anchor-borrowers-scheme-raising-stake-in-agric-financing.

- Timmer, C.P.; Akkus, S. The structural transformation as a pathway out of poverty: Analytics, empirics and politics. Cent. Glob. Dev. Work. Pap. 2008, pp. 1–60. Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/91306/wp150.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Titenko, Z. (2023). Modeling the impact of capital investments on the financial security of agrarian enterprises. Bìoekonomìka ta agrarnij bìznes, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, H., & Tiwari, H. (2023). Analyzing Development Induced Trade-Offs: A Case Study of Loktak Multipurpose Project (LMP) in Manipur. In Sustainable Development Goals in Northeast India: Challenges and Achievements (pp. 571-585). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Tramutoli, V., Samela, C., Coluzzi, R., Chavarriga Améstica, D. F., (2023). Development of algorithms based on the integration of meteorological data and remote sensing indices for the identification of low-productivity agricultural areas. EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, EGU-12958. [CrossRef]

- Tugga, S. E., Hassan, A. A., & Ojeleye, O. A. (2023). Profitability analysis of sorghum small-scale farmers in selected local government areas of Gombe State, Nigeria. Journal of Agripreneurship and Sustainable Development, 6(1), 47–55.

- Uçak, H., Çelik, S. & Kurt H. (2023). Land resources and agricultural exports nexus. Folia Oeconomica Stetinensia, 23(1), 284-300. [CrossRef]

- Udoh, E. J. (2005). Demand and control of credit from informal sources by rice producing females of Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Journal of Agriculture and Social Sciences, 1(2), 152-155.

- Udondian, N. S., & Robinson, E. J. Z. (2018). Exploring Agricultural Intensification: A Case Study of Nigerian Government Rice and Cassava Initiatives. International Journal of Agricultural Economics, 3(5), 118-128. [CrossRef]

- Uduji, J. I., Okolo-Obasi, E. N., & Asongu, S. A. (2019). Farmers’ food price volatility and Nigeria’s Growth Enhancement Support Scheme. African Governance and Development Institute Working Paper, 19/075. https://ideas.repec.org/p/agd/wpaper/19-075.html.

- Umar, M. L., Mohammed, S. B., Ishiyaku, M. F., Adamu, R. S., Utono, I. M., Addae, P. C., Kollo, A. I., Nwankwo, O. F., & Bolarinwa, O. (2022). Development and Commercialization of Bt-Cowpea in Nigeria: Implication for National Development. In Agricultural Biotechnology, Biodiversity and Bioresources Conservation and Utilization (pp. 69-78). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Uneze, C. (2013). Adopting Agripreneurship Education for Nigeria’s Quest for Food Security in Vision 20:2020. Greener Journal of Educational Research, 3(9), 411–415. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Collabourative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (UN-REDD). (2024). Q&A: Nigeria's forests are fast disappearing. Steps are needed to protect their benefits to the economy and environment. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2024-03-qa-nigeria-forests-fast-benefits.html.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2022). Policy recommendations. In Aligning Economic Development and Water Policies in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) (pp. 43-47). [CrossRef]

- United Nations Nigeria. (2022). Common country analysis 2022. United Nations. https://nigeria.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-07/Common%20Country%20Analysis%202022_Nigeria.pdf.

- Usman L., R., Anditiaman, N. M., Rahim, I., Arifuddin, R., & Tumpu, M. (2023). Labor productivity study in construction projects viewed from influence factors. Civil Engineering Journal, 9(3), 583-595. [CrossRef]

- Usman, H. I. (2021). Nigeria Pesticides Consumption Profile. Journal of Research in Weed Science, 4(4), 257-263. doi:10.26655/JRWEEDSCI.2021.4.1.

- Usubamatov, R. (2018). Productivity Theory for Industrial Engineering (1st ed.). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Wahab, K., Adedokun, L. A., & Onibokun, A. G. (1990). Urban housing conditions. In: Onibokun, A.G. (Ed.), Urban Housing in Nigeria. Nigeria Institute of Social and Economic Research Ibadan. 144-173.

- Wang, G., Hausken, K. (2023). Comparing growth models with other investment methods. Journal of Finance and Investment Analysis, 12(1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. L., Heisey, P., Schimmelpfennig, D., & Ball, E. (2015). U.S. Agricultural Productivity Growth: The Past, Challenges, and the Future. Amber Waves: The Economics of Food, Farming, Natural Resources, and Rural America, 2015(8), 1. [CrossRef]

- Williams, E., & Agbo, S. (2013). Evaluation of the Use of Ict in Agricultural Technology Delivery to Farmers in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Journal of Information Engineering and Applications, 3(10), 18–26. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JIEA/article/download/7632/8050.