3.1. Soil Structural Stability

Soil structure durability, as assessed in this study, refers to the ability of soil aggregates to resist disintegration in water and maintain their structural integrity. This is a complex property influenced by multiple factors. Soil particles are bound into aggregates of various sizes through mechanisms such as microbial exudates and organic matter compounds [

23]. The stability of these aggregates provides important insights into soil functioning and is a key indicator of soil quality and health in agroecosystems [

24]. Stable aggregates are more resilient to environmental stress, reduce erosion, improve the protective function of organic matter [

25], and increase the soil’s resistance to climate change.

In the first year of the experiment, at the beginning of the growing season, soil structural stability did not differ significantly across the studied treatments and ranged from 28.6% to 39% (

Table 3).

When assessing the change in structural stability over time, it was observed that in almost all treatment plots, this indicator decreased by approximately 20 percentage points. The smallest decline in structural stability was recorded in the plots where Persian clover and blue-flowered alfalfa were used as intercrops, with a negative change of about 14–15 percentage points. This may be attributed to the fact that, in these plots, both the intercrops and weeds likely covered the soil surface more rapidly at the beginning of the growing period, thereby providing better protection of the soil against adverse meteorological conditions.

Analysis of the second year of the experiment revealed that soil structural stability in most of the studied treatments remained like that observed in spring 2023. This suggests that the soil structure did not recover over the winter period. During the 2024 growing season, structural stability improved in all examined soils by 10–20 percentage points, indicating that meteorological conditions may have been more favourable. Notably, common oats used as an intercrop had the most positive effect on improving this indicator, with structural stability increasing by nearly 20 percentage points. Since soil structure is closely linked to soil organic carbon content, these results may be explained by the fact that oats are known to accumulate relatively high levels of organic carbon. Previous studies have shown that common oats can accumulate almost twice as much organic carbon as weeds [

26].

After two years of experimentation, only minor changes in soil structural stability were observed. The most pronounced positive effect was recorded in the treatment where blue-flowered alfalfa was intercropped in the first year and common oat in the second. In this treatment, aggregate stability increased by 3.6 percentage points. In contrast, all other treatments showed a decline in soil structural stability, ranging from 2.2 to 9.3 percentage points. These results suggest that maintaining or enhancing soil structure and its stability requires rapid germination and early canopy development of intercrops, to cover the inter-row zones. This vegetation would act as a protective layer, mitigating the effects of adverse meteorological conditions. Supporting findings from other studies confirm this trend. Gentsch et al. [

27] demonstrated that intercropping with clover and phacelia significantly increased soil aggregate stability compared to a bare fallow control. Dai et al. [

28] reported that the presence of peas in the rotation increased the proportion of water-stable aggregates by 68.61% relative to plots without cover crops. Seidel et al. [

29] investigated maize-bean intercrops, also observed a significant improvement in aggregate stability compared to maize monocultures. Mendis et al. [

30] found that an intercrop mixture of rye (

Secale cereale L.), crimson clover (

Trifolium incarnatum L.), and daikon radish (

Raphanus sativus L. var.

longipinnatus) improved soil moisture retention and increased organic matter content, both contributing positively to soil structural stability in maize agroecosystems.

Nitrogen is one of the most essential macronutrients required by plants in substantial quantities. It plays a critical role in numerous physiological and biochemical processes, including the synthesis of amino acids and proteins (which serve structural functions), nutrient transport, and more. Nitrogen has a particularly significant influence on both crop yield and quality [

31]. Scientific studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between total soil nitrogen and soil organic carbon content. The biomass of soil microorganisms is also strongly affected by both indicators. These findings highlight total nitrogen as a key indicator of soil quality, with its depletion closely associated with processes of soil degradation [

32].

In the spring of the first experimental year (2023), total nitrogen content in the soil ranged from 0.11% to 0.13% (

Table 4). By autumn 2023, the lowest total nitrogen level (0.12%) was recorded in the first control treatment, where only inter-row loosening was applied. This reduction may be attributed to nitrogen leaching or volatilization during the growing season, as the inter-row spaces were not protected by vegetation or crop residues. According to Porwollik et al. [

33], the use of cover crops in combination with tillage can reduce annual nitrogen leaching by an average of 39%. In contrast, all other treatments exhibited higher total nitrogen levels, ranging from 0.13% to 0.14%.

In the second year of the experiment (2024), at the beginning of the growing season, the total nitrogen (Ntot.) content in all studied soils showed minimal variation, ranging from 0.11% to 0.12%. By the end of the growing season, a slight increase was observed, with SUM-N levels rising to 0.13–0.14%. Although the change was not statistically significant, it may be attributed to the mineralisation of nitrogen from the crop residues remaining from the previous season (2023).

The change in total nitrogen after two years of the experiment was negligible, with the maximum difference reaching only 0.01 percentage points. This suggests that, in most cases, endogenous crop rotations did not negatively impact total nitrogen levels in the soil. The results indicate that the inclusion of intercropping may have positive impact to the increase of this indicator.

The cultivation of maize contributed to the stabilisation of total nitrogen levels in the soil. In some cases, slight positive changes in this indicator were also observed; however, further investigation is required to confirm these trends. These results may appear somewhat unexpected, given that no mono-nitrogen fertilisers were applied during the experiment. Nitrogen availability was limited to the amount present in the complex fertiliser used for starter fertilisation. Moreover, both maize and intercropped plants compete for nitrogen. Under such conditions, a decline in total nitrogen content would typically be anticipated over a two-year period. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that growing leguminous cover crops for at least one season may be sufficient to maintain a favourable soil nitrogen balance over two years.

According to Chai et al. [

34], cereal–legume mixed cropping systems offer more efficient utilisation of synthetic nitrogen compared to non-legume monocultures. This efficiency arises from interspecific competition and the ability of legumes to biologically fix atmospheric nitrogen, which can then be partially transferred to adjacent cereal crops. Furthermore, Liu et al. [

35] reported that total soil nitrogen content was statistically significantly higher—ranging from 4.4% to 14.3%—in mixed intercropping systems at all stages of maize growth compared to monoculture systems.

For example, Fan et al. [

36] demonstrated that peas grown in mixed cropping systems can achieve biological nitrogen fixation rates ranging from 119 to 238 kg ha⁻¹ and the mineral nitrogen concentration in the topsoil at the rows of maize was found to be up to 33% higher compared to maize grown in monoculture. In such intercropping systems, species like common vetch (

Vicia sativa L.) and pea (

Pisum sativum L.) have proven particularly effective when combined with maize (

Zea mays L.). This approach not only enhances maize yields but also improves resource use efficiency and supports agricultural sustainability [

37].

The integration of legumes into cropping systems contributes significantly to soil fertility by serving as a natural nitrogen source, thereby reducing the dependence on synthetic nitrogen fertilisers, and by enhancing soil organic carbon sequestration [

38]. Legume-based intercropping systems promote symbiotic nitrogen fixation, enabling a reduction in mineral nitrogen input by up to 26% without compromising crop yields [

39]. Moreover, Li et al. [

40] highlight that efficient mixed cropping systems enhance not only symbiotic but also non-symbiotic nitrogen fixation, further supporting the sustainable management of nitrogen in agroecosystems.

3.3. Soil Mobile Phosphorus

Phosphorus is a macronutrient and one of the key limiting factors for plant productivity. It plays a crucial role in essential physiological processes, including photosynthesis, respiration, and energy transfer [

41]. In addition, phosphorus significantly influences root system development. The relationship between the root system, soil microorganisms, and phosphorus compounds is highly interdependent. The uptake of phosphorus, along with other nutrients, is often mediated by microbial activity. Soil microorganisms can convert insoluble forms of phosphorus into plant-available forms or stimulate root growth, thereby enhancing the root surface area and improving nutrient acquisition efficiency [

42]. However, with the intensification of agriculture, phosphorus unavailability is becoming an increasing issue. In many cases, suboptimal soil pH leads to the transformation of phosphorus into insoluble forms that are inaccessible to plants. As a result, even soils with adequate total phosphorus content may still fail to meet the phosphorus requirements of crops, leading to nutrient deficiencies [

43].

In the spring of the first year of the experiment (2023), the mobile phosphorus content of the fields varied between 227 and 250 mg kg

-1 (

Table 5).

Autumn agrochemical analyses indicated that the mobile phosphorus content in the soil did not change significantly during the first growing season, remaining within the range of 225 to 270 mg kg⁻¹. The highest, though not statistically significant, level of mobile phosphorus (270 mg kg⁻¹) was recorded in the second control treatment, where maize inter-rows were mulched with weed biomass. Data from the second year of the experiment (2024) revealed an overall increase in mobile phosphorus content at the end of the growing season across all tested treatments. The most pronounced increases were observed in the soils of the first and second control treatments, where inter-row loosening and weed mulching practices were applied, respectively.

The analysis of mobile phosphorus dynamics over the two-year period (2023–2024) revealed a consistent increasing trend across all treatments’ soils. The most notable increases in mobile phosphorus were observed in the soils where maize experienced the least competition from other plants. These findings suggest that the use of endogenous crop rotation sequences does not adversely affect mobile phosphorus availability in the soil. Although Sun et al. [

44] reported that alfalfa exhibited 3.0–5.7 times greater competitive ability than maize when co-cultivated, resulting in a 17–36% reduction in maize root growth, a 24% decrease in phosphorus uptake, and a 12% decline in yield. So, the current study did not observe similar negative outcomes under the implemented rotation systems.

In conclusion, intercropping did not have a detrimental effect on mobile phosphorus content. This finding is particularly noteworthy, as it might initially be assumed that higher plant density—resulting from the presence of both maize and intercropped plants—would lead to increased phosphorus uptake and subsequent depletion. While this was partly reflected in the slightly lower mobile phosphorus levels observed in intercropped treatments compared to maize-only controls, a positive overall trend was evident across all treatments. These results indicate that intercropping can be implemented without compromising soil phosphorus availability.

According to Zhu et al. [

45], legume and cereal crops have developed various strategies to regulate phosphorus availability within plant-soil systems. Research conducted in northwestern China demonstrated that reducing phosphorus fertilizer rates from 150 to 75 kg ha⁻¹ in a mixed maize-bean cropping system stimulated bean plants to enhance the dissolution of phosphorus-related cations and the formation of complex compounds [

46]. Furthermore, Wu et al. [

47] reported that intercropping legumes with maize improved soil phosphorus availability, positively influencing maize growth. Similarly, Li et al. [

48] found that intercropping wheat, maize, and soybean resulted in significantly higher phosphorus uptake per unit area compared to monocultures, directly contributing to increased yields.

Researchers have found that the intercropped blue-flowered alfalfa increased the uptake of phosphorus from the soil compared to a monocrop of maize [

49]. According to a study by Wang et al. [

50], the interaction between the roots of maize and alfalfa is crucial to improve the phosphorus use efficiency and the productivity of intercropping. These results were also obtained in this experiment. Research data show that the ability of plants to uptake and efficiently utilise phosphorus in response to the crop type depends on their physiological and metabolic characteristics, as well as on the environmental conditions [

51,

52]. With minimal yet balanced fertilization, endogenous rotational chains do not have a negative impact on the amount of mobile phosphorus present in the soil, and the change remains positive.

3.4. Soil Mobile Potassium

When plants have a balanced uptake of potassium fertilizer, they are less adversely affected by frost, drought, pests, and diseases. This results in higher yields, healthier plants, and improved produce quality [

53]. Unfortunately, intensive farming systems often rely on excessive nitrogen fertilizers, leading to nutrient imbalances in the soil.

In the first year of the experiment (2023), the mobile potassium content in the soil ranged from 103 to 122 mg kg⁻¹ (

Table 6). In 2024, a general upward trend in mobile potassium levels was observed across all treatments. The highest concentration was recorded in the soil of the second control treatment, where weed mulch was applied (208 mg kg⁻¹). Notably, in both years of the experiment, the mobile potassium content in nearly all soil samples remained stable, showing no depletion in values between the beginning and the end of the growing season. However, it is noteworthy that in the second year of the experiment, the lowest mobile potassium content—though not statistically significant—was observed in the soil of the treatment where spring barley was intercropped with maize, showing a decrease of 23 mg kg⁻¹, or 20.2%. This decline may be attributed to the relatively high potassium requirements of both maize and spring barley. Therefore, nutrient uptake should be carefully considered when using spring barley in intercropping systems. Interestingly, Mariscal-Sancho et al. [

54] reported contrasting findings, showing that intercropping spring barley with maize had the most beneficial effect on soil microbial activity and nutrient availability, resulting in the highest maize biomass and nutrient status. In contrast, barley performed poorly when intercropped to wheat, highlighting the potential drawbacks of multicropping two plants from the same botanical genus.

An analysis of changes in mobile potassium over the two-year experiment revealed that, in most cases, soil potassium content decreased by 0.5 to 14.0 mg kg⁻¹. However, the rotation involving blue-flowered alfalfa intercropped in the first year and oats in the second year, had the most positive outcome, with an increase of 7.0 mg kg⁻¹ in mobile potassium. Although an overall decline in potassium was observed after two years, it is noteworthy that this reduction did not occur immediately after the growing season in autumn but rather following the winter period. This suggests that the loss of mobile potassium may be attributed to leaching or transformation into forms less available to plants during winter. These data suggest that mobile potassium was lost through leaching or converted into forms unavailable to plants during the winter period. We can conclude that intercropping did not have a significant negative impact on the mobile potassium content of the soil. Although maize has a relatively high potassium requirement, it might initially be assumed that maize would compete with intercrops for nutrients, potentially leading to a decline in soil potassium levels. However, this was not observed. In the first year of the experiment, it can be observed that the intercropped leguminous (Crimson clover, Persian clover, blue-flowered alfalfa) increased the mobile potassium content of the soil during the growing season. Very similar findings are reported by other researchers who have also observed an increase in soil-mobile potassium when using leguminous crops [

55]. However, there is a tendency for the content of this element to decrease quite sharply after winter, which could be due to leaching.

3.5. Soil Mobile Magnesium

Magnesium is the macronutrient that is most associated with photosynthesis in plants, as it is the element that constitutes chlorophyll [

56]. Although it is less required by plants compared to the main macronutrients, i.e., nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, the importance of magnesium for plants is undeniable, as a higher level of mobile magnesium in the soil results in a higher level of chlorophyll in the leaves of the plant, with a direct impact on the intensity of photosynthesis and plant yield [

57].

In the spring of the first year of the experiment (2023), the amount of mobile magnesium in the soil varied between 560 and 791 mg kg

-1. At the end of the growing season, it can be observed that the content of this element remained similar in most of the soils of the treatments. The highest mobile magnesium (not statistically significant) content was found in the second control treatment with weed mulch. Harasim The comparison of the values at the beginning and at the end of the growing season in the soil of this treatment, it was found that the mobile magnesium content increased by 152 mg kg

-1 or 25.0%. Similar findings were noted by Harasim et al. [

58], who discovered that mulching with rye and white mustard increased the phosphorus and magnesium content of the soil. In the second year of the experiment, the mobile magnesium content of the soil varied between 504 and 707 mg kg

-1. In this year, the highest positive change (169 mg kg

-1) was observed in the soil of the first control, where the inter-rows were loosened. In all the other treatments, the content of this element did not change significantly when comparing the results at the beginning and end of the growing season. However, the soils of all treatments are classified as soils with high mobile magnesium content, so even a light decrease in this element in some of the treatments will not adversely affect soil quality.

An analysis of the change in mobile magnesium between 2023 and 2024 shows that after the two years of the study, the most significant decreases in mobile magnesium are observed in most of the soils of the investigated treatments. Partly, these results can be explained by the fact, that the amount of this element decreased mainly in the soils of the treatments where maize was intercropped with other plants. However, very similar results were obtained in the soil of the first treatment, with a decrease of 84 mg kg-1 in mobile magnesium after two years.

In conclusion, the multi-cropping did not have a significant effect on the mobile magnesium content of the soil in most cases. The two years of data do not show a clear trend, as the results are quite different in the first and second year. The fact that the cultivation of cover crops does not have a significant effect on the mobile magnesium content of the soil has also been found by other researchers [

59]. The magnesium content of the soil is closely related to soil pH and should therefore be considered in a comprehensive manner. Although there is a trend towards a decrease in mobile magnesium content in some treatments, there is no significant change in pH after two years. It can therefore be concluded that the application of endogenous rotations does not have a significant impact on the mobile magnesium content.

3.6. Interaction of Chemical and Physical Soil Properties

A correlation analysis of soil agrochemical and physical properties showed that as the total nitrogen content of the soil increased, so did the soil structural stability (

Table 8). In 2023 there was a strong correlation (r=0.786) and in 2024 there was a reliably strong correlation (r=0.836*) between these indicators. Other researchers have found that soil structure is most influenced by the amount of soil organic matter [Jastrow, Miller, 2018]. Most of the soil nitrogen (approximately 90%) is contained in organic matter, which explains the strong relationship between soil structural stability and total nitrogen content [

60]. A strong correlation between these two factors has also been found by other foreign researchers [

61]. According to Zang et al. [

62], oat and soybean root exudates increased soil carbon and nitrogen content, which may have a positive effect on soil fertility and structure. Thus, this analysis showed that all the mobile chemical elements studied (i.e., mobile phosphorus, potassium and magnesium) are in most cases quite strongly correlated with each other. In 2023, mobile phosphorus levels correlated strongly (moderately in 2024) with mobile magnesium levels in the soil. There was also a reliably strong correlation between mobile phosphorus and mobile potassium in soil (r=0.970**). Scientists have determined that maintaining a specific nutrient ratio is essential for achieving optimal crop productivity. For example, maize grains (e.g., 1 kg) can contain between 0.6 and 5.2 g of phosphorus and 1.0–9.7 g of potassium. From these data, it can be estimated that the ratio of phosphorus to potassium in cereals is about 1:1.8 [

63]. The interlinkages of the different nutrient elements are also demonstrated by Lybig’s law of the minimum, which reveals that the yield depends on the factor that is most deficient [

64]. However, in 2024, these trends have not always been confirmed at the experiment. This may have been due to different meteorological conditions, which also had a significant impact on the uptake of nutrients from the soil throughout the growing season.

In the second year of the study, a significant positive correlation was observed between mobile magnesium content and soil pH, indicating that as mobile magnesium levels increased, the soil became more alkaline (r = 0.860). This finding supports the role of magnesium as a key element influencing soil pH, as confirmed by previous studies [

65]. The increase in mobile magnesium contributes to soil neutralisation reactions, resulting in pH changes [

66]. In 2023, a strong correlation was also identified between soil pH and soil structural stability (r = 0.763). Previous research has shown that calcium and magnesium ions interact with soil clay particles, enhancing the formation of stable soil aggregates [

67]. However, this trend was not observed in the 2024 data of the experiment.

3.7. Complex Evaluation

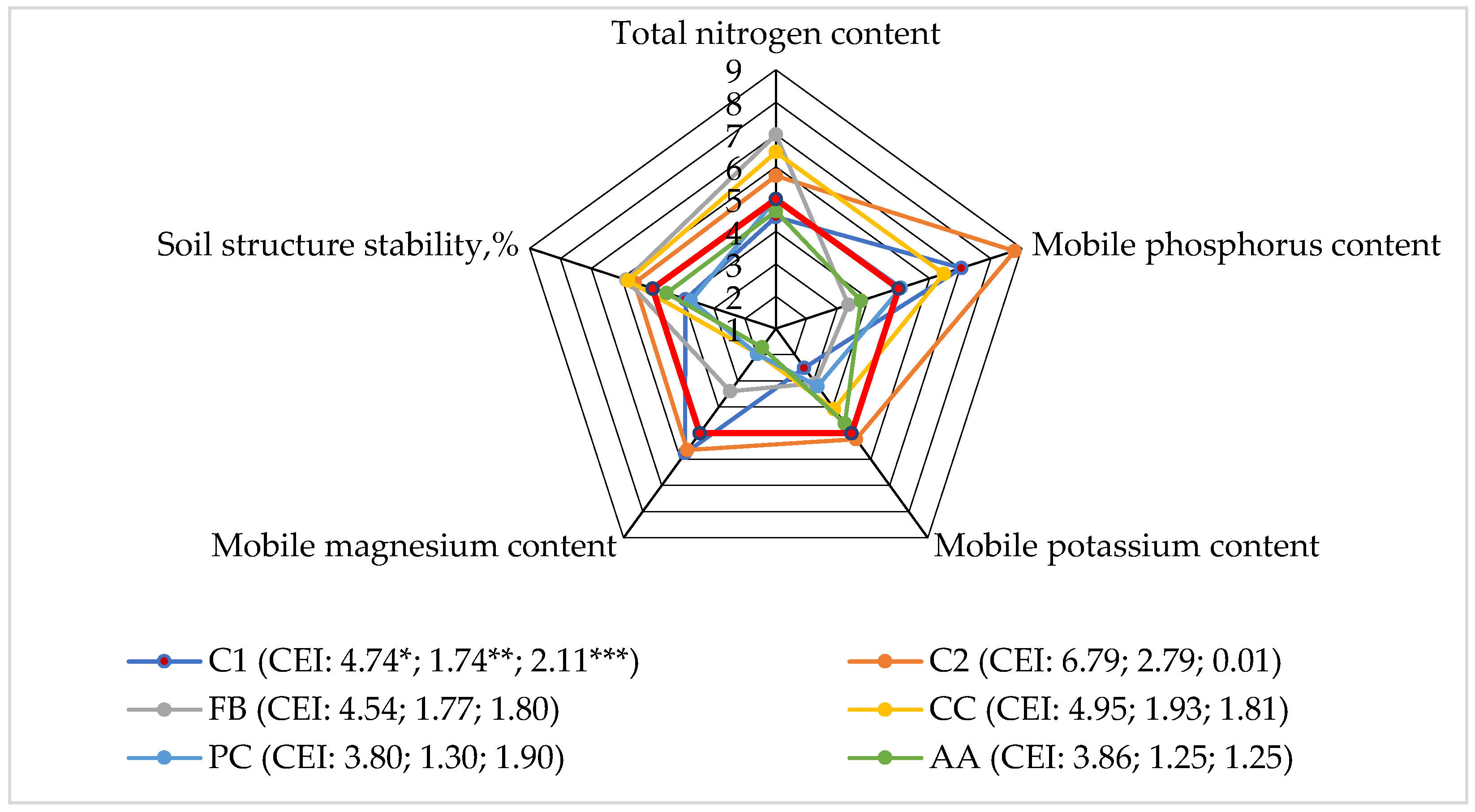

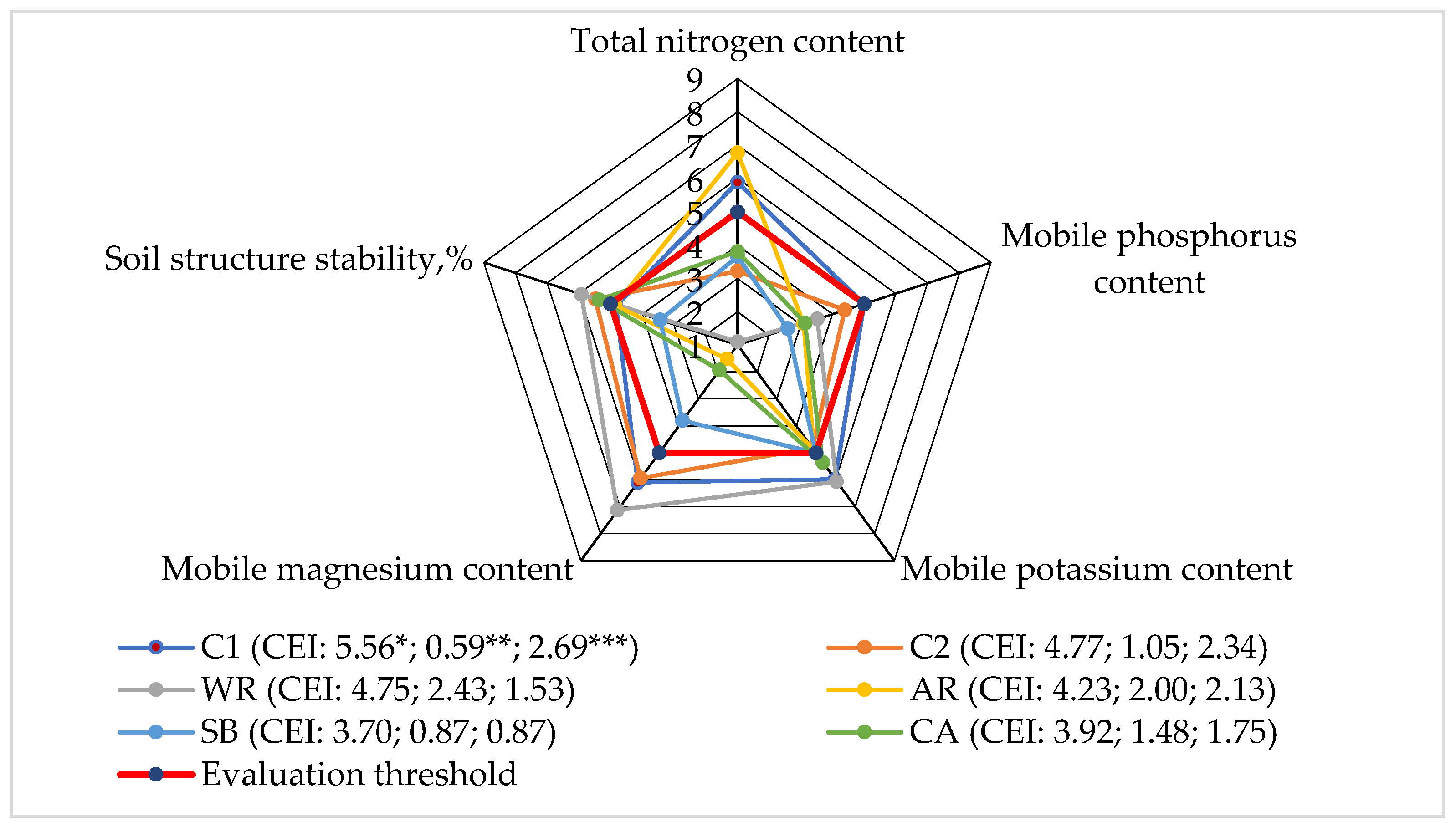

We found that the most important indicators used to assess endogenous systems are soil stability, total nitrogen, mobile phosphorus, mobile potassium and magnesium. These key indicators, which reflect the levels of endogenous rotations, also interact with other indicators of the system. We have carried out an integrated assessment of the chemical and physical properties of the soil based on the description of the system levels and the internal interactions (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

In 2023, weed mulching had the highest overall CEI value (6.79). The most noteworthy parameter is the mobile phosphorus content in the soil. In addition to a high CEI value, the purple clover intercropped in maize had a very good balance between phosphorus and nitrogen parameters. In a complex assessment, intercropped crimson clover and blue-flowered alfalfa were mostly within the CEI assessment threshold.

In 2024, inter-row loosening in maize mono-crop treatment had the highest CEI value. This treatment significantly exceeded the assessment threshold for nitrogen, stable aggregates and mobile phosphorus (

Figure 2). Mulching of inter-rows with weeds (CEI = 4.77) also exceeded the assessment thresholds, especially for total nitrogen and potassium in the soil. Nevertheless, the agronomic practices of this treatment maintained a balanced impact to the soil, which may be favourable for long-term sustainability.

The results of the complex assessment for intercropped common oats (CA) and spring barley (SB) fell within acceptable evaluation thresholds. Ryegrass (AR) demonstrated better outcomes in terms of nitrogen and potassium levels, although deficiencies in phosphorus and magnesium were noted. In contrast, the spring barley (SB) and common oat (CA) treatments showed only marginal improvements in nitrogen content or soil structural stability, with an overall limited impact on key agrochemical soil parameters. According to Masson et al. [

68], intercropped plants significantly influence the soil nutriment web conditions by providing additional soil organic matter (SOM) and nutrient inputs to the soil.