1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) characterized by cumulative and often irreversible neurologic damage has no established cure and continues to challenge therapeutic advancements [

1]; WHO. Current pharmacologic treatments offer symptomatic relief but may also produce undesirable side effects, underscoring the need for alternative non-pharmacological interventions in MS management [

2,

3]. Neurorehabilitation approaches particularly those leveraging non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) present a promising avenue for enhancing functional abilities without medication reliance addressing both motor and cognitive deficits that contribute to quality-of-life declines in MS [

4,

5]. 45–70% of individuals have cognitive impairments [

6,

7] and can emerge early progressively worsening over time thereby contributing to a reduced quality of life and impaired social functioning [

8,

9]. Motor dysfunction, affecting up to 80% of individuals with MS can result from muscle weakness, abnormal gait, balance issues and fatigue [

10]. Furthermore, the interplay between cognitive and motor dysfunction is significant with cognitive decline linked to increased risk of falls and greater motor impairment [

11].

In MS the distinctions between pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention one must explore both the therapeutic use of drugs and alternative methods that improve health without medication. Rehabilitation plays a critical role and focuses on enhancing functional abilities mitigating symptoms and improving the quality of life for pwMS making it an essential component of comprehensive MS care. Other rehabilitation approach such as electrical or magnetic stimulation to modulate activity in the cerebral cortex, potentially inducing long-lasting neuroplastic changes [

12]. Among these techniques tDCS and rTMS are the most widely studied [

13,

14,

15].

Last thirty decades NIBS in rehabilitation has received considerable attention. rTMS has been shown to enhance upper and lower extremity functions and modulate cortical excitability [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Yang et al. (2013) are the first to combine rTMS and treadmill-walking training and reported electrophysiological and functional changes in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) [

20]. To date, much of the evidence has focused on symptoms like pain [

21], cognitive and fatigue [

22] with limited data available on its influence on motor outcomes with pwMS. Furthermore, there are no established guidelines for the therapeutic use of NIBS in MS [

23]. This review aims to offer a detailed analysis of the effects of NIBS techniques in MS gait rehabilitation exploring their efficacy application and potential to enhance the quality of life for MS patients. By synthesizing current research this review will provide insights into future clinical applications and research directions in the field of MS rehabilitation.

Pathophysiology, Primarily from the demyelination and axonal damage affecting neural pathways that control movement and coordination, this damage which is central t0 disrupts the communication between the brain and muscles leading to various motor impairments. Key features of gait disturbances include muscle weakness, spasticity, impaired proprioception, and balance issues, all contributing to an unsteady and often slow gait pattern [

24].

Spasticity, a hallmark symptop particularly affects the lower limbs leading to rigidity and reduced range of motion which in turn hampers step length and walking speed [

25]. Sensory ataxia or a lack of coordination due to impaired sensory feedback is also common. This ataxia stems from lesions in the cerebellum or proprioceptive pathways crucial for maintaining smooth and coordinated gait [

26]. In addition, fatigue another frequent MS symptom exacerbates gait instability especially during prolonged walking activities further reducing walking endurance and safety [

27].

Lesions in the spinal cord and brainstem additionally disrupt the neural circuits involved in motor control and contribute to balance deficits increasing the risk of falls. The cumulative effect of these symptoms leads to a distinct “MS gait” often characterized by asymmetry, reduced stride length and compromised postural control which significantly impacts mobility and quality of life [

28].

EDSS, Hauser ambulation index score used to assess walking disability in MS [

29,

30]. The T25FWT is used to assess maximal walking speed over a short distance, measured in seconds, as part of the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC). To perform the T25FWT, the patient is instructed to walk 25 feet as quickly as possible, but safely, along a clearly marked course. The test is immediately repeated by having the patient walk back the same distance, and the T25FWT score is calculated as the average time of the two trials [

31,

32,

33]. The 6MWT evaluates walking endurance [

34]. For this test, the patient is instructed to walk as far and as fast as possible within a 6-minute period, with the total distance covered used as the score. Both the T25FWT and 6MWT are simple, easily quantifiable tests that can be administered by personnel with minimal training and require minimal time to execute.

Neuroplasticity and Gait

Neuroplasticity enables the brain to reorganize its neural circuits to compensate for deficits an essential factor in MS-related gait dysfunction. Variables such as age at disease onset influence premorbid cognitive functional reserve which affects neuroplastic potential. Post-diagnosis MS patients may experience diminished brain plasticity and a decreased capacity for remyelination [

35,

36]. Additionally, sex differences in MS impact damage and repair mechanisms influencing variations in functional connectivity within the brain [

37,

38]. Lesion characteristics such as type, location, extent, and severity significantly impact neuroplastic adaptation [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Acute inflammation influences brain responses depending on the functional systems involved, with affected systems sometimes returning to baseline post-inflammation [

39,

40,

41,

46] However, chronic inflammation can drive sustained functional reorganization by altering local plasticity [

44,

47].

Harnessing neuroplasticity offers a rehabilitation pathway for functional recovery in MS. Evidence from stroke recovery underscores that neuroplasticity-driven interventions can rewire neural circuits and improve motor function despite severe impairments [

48,

49]. Similar principles apply in MS, where neuroplastic potential enables functional gains through training [

50]. Combining NIBS with motor training enhances these effects; for example, stimulating the primary motor cortex (M1) increases cortical excitability and reinforces pathways essential for gait [

44]. In MS, even short-term right-hand visuomotor task practice can reorganize ipsilateral sensorimotor regions, correlating with disability levels [

39]. Long-term practice similarly restructures cognitive systems, enabling unique compensatory strategies. Techniques like constraint-induced movement therapy, successful in stroke, are under evaluation for MS, as they promote contralateral sensorimotor adaptation [

51,

52]. Neuroplasticity in MS supports motor performance improvements even amidst severe dysfunction [

50]. Cognitive rehabilitation can similarly augment brain functional reserve especially in pediatric MS cases [

53,

54,

55,

56]. Motor imagery practice (MIP) is another effective strategy sharing motor control mechanisms with physical movements and enhancing rehabilitation outcomes [

57,

58,

59].

Emerging device-based therapies including neuroprosthetics for motor recovery and cognitive enhancement tools are promising in MS rehabilitation [

60,

61], supported by the preserved plasticity across the disease spectrum [

50]. NIBS techniques like repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) hold potential for enhancing synaptic plasticity and cortical excitability in motor regions, such as M1 and the supplementary motor area (SMA). Recent studies highlight NIBS’s potential for improving walking speed and endurance, illustrating its capacity to enhance motor cortex excitability and strengthen adaptive plasticity in MS patients [

62].

Mechanism

The mechanisms underlying NIBS effects on motor cortex excitability, specifically using rTMS and tDCS. Both techniques aim to modulate the neurophysiological processes of the motor cortex to either enhance or inhibit corticospinal excitability. rTMS modulates motor cortex excitability through the repeated application of magnetic pulses at specified frequencies, allowing for causal inferences about the motor cortexs role in behavior (Rotenberg et al., 2014). Depending on the stimulation frequency rTMS can lead to either facilitation or suppression of corticospinal excitability. Theta burst stimulation (TBS) a patterned form of rTMS mimics natural brain oscillations and induces NMDA receptor-dependent plasticity contributing to both short- and long-term effects on motor function [

63,

64].

tDCS operates by applying weak electrical currents to modulate cortical excitability in a polarity-dependent manner. Anodal tDCS enhances excitability by shifting the resting membrane potential towards depolarization while cathodal stimulation reduces excitability by promoting hyperpolarization [

65,

66,

67]. These effects although influenced by stimulation intensity can lead to improved motor function, as seen in various studies on motor impairments [

68]. Together, rTMS and tDCS offer complementary methods to explore and modify the neurophysiological substrates of motor dysfunction, with applications in both research and clinical settings.

Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Intervention

Pharmacological interventions may help improve gait dysfunction in pwMS. An important aspect of these interventions is identifying specific impairments, such as spasticity through neurological evaluation, as spasticity is a major contributor to gait impairment in MS. Pharmacological treatments aimed at reducing spasticity can, in turn, improve walking performance for pwMS. Medications are administered through various methods including oral medications, intrathecal baclofen, and intramuscular botulinum toxin injections, each offering potential benefits depending on the patients individual symptoms and needs [

69,

70].

Non-pharmacological interventions play an essential role in managing gait dysfunction in MS, providing a range of therapeutic options beyond medication. The physical interventions, maintain or increase the length of spastic muscles and reduce contractures by increasing soft tissue extensibility through viscous deformation and structural adaptation of muscles and other soft tissues and by changing the excitability of motoneurons innervating the spastic muscles [

71,

72,

73]. Gait dysfunction due to ataxia and somatosensory deficits in individuals with MS can often be managed effectively with the assistance of mobility aids, such as a cane or walker. These devices help improve gait by widening the base of support, which enhances postural stability. For individuals with diminished sensory input in the lower limbs, using these aids provides additional sensory feedback through the upper limbs, which can partially compensate for reduced proprioception by bypassing affected spinal pathway [

74]. In addition, balance-specific exercise programs have been shown to improve balance in people with MS. Recent evidence suggests that targeted balance training, including innovative approaches such as torso weighting, virtual reality-based exercises, and visuoproprioceptive training, may positively impact both balance and walking ability in MS patients [

75,

76,

77,

78].

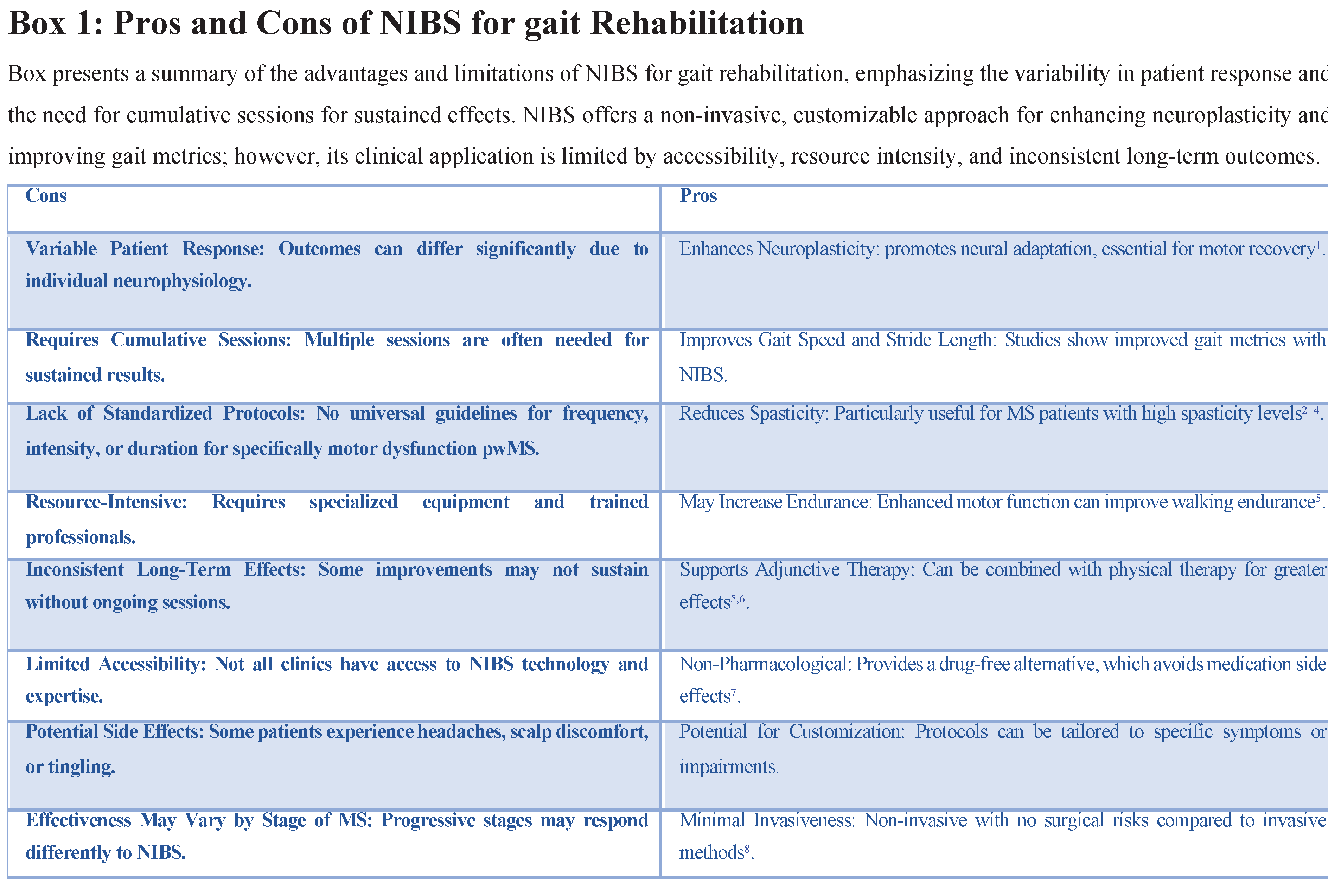

However, an emerging area of interest is NIBS, Last three decades a variety of NIBS have been invented to improve brain plasticity and enhance neural function of the human brain. There were two neuromodulations frequently using in pwMS which helps to improve cognitive, motor enhancement, reduce spasticity level in pwMS [

79]. and high frequency rTMS has significant changes in gait parameters [

4,

80].

a technique with promising potential to enhance gait rehabilitation and offer unique mechanisms that may positively impact motor function and gait by targeting specific brain regions involved in movement control.

2. Evidence of NIBS in Gait Rehabilitation

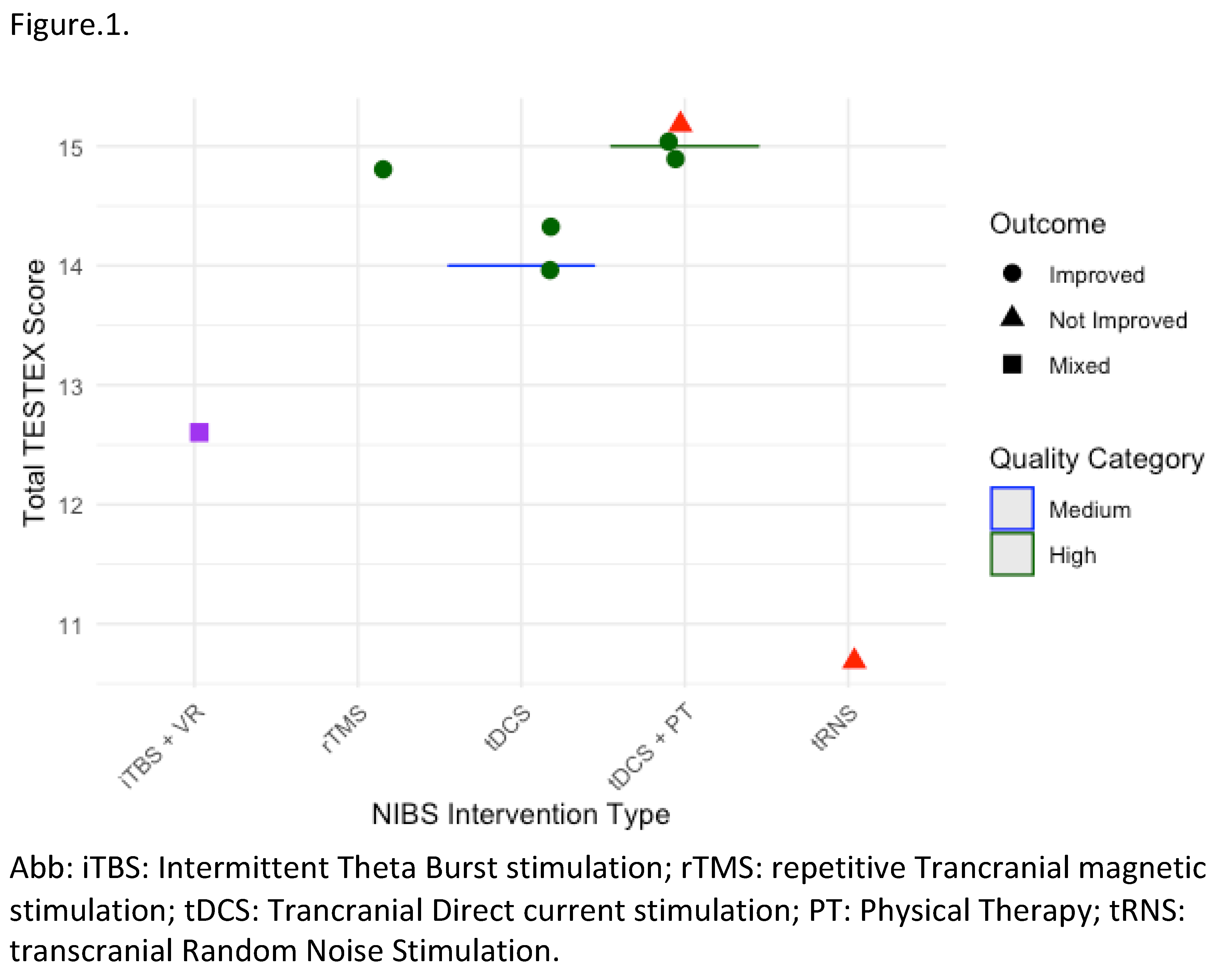

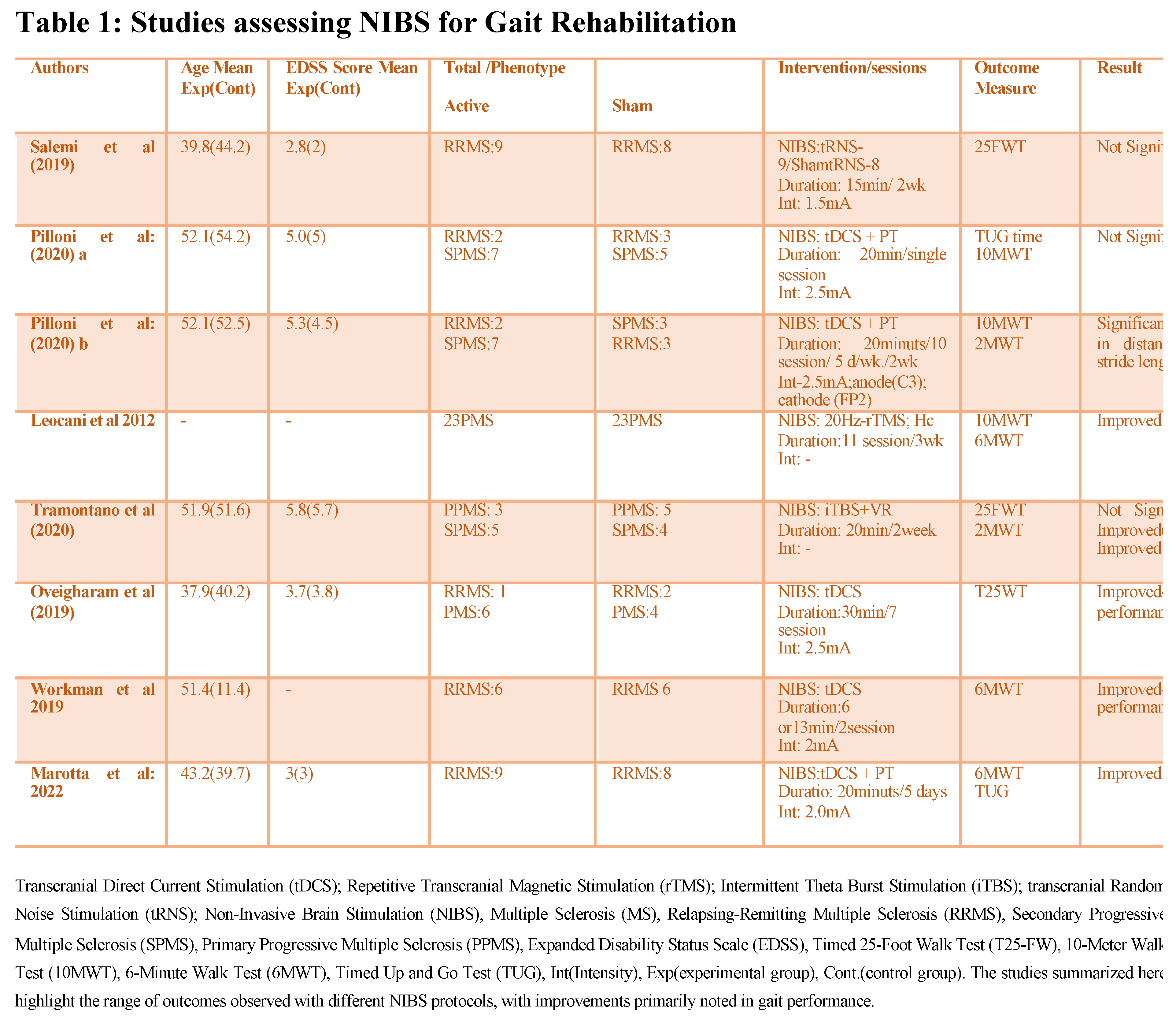

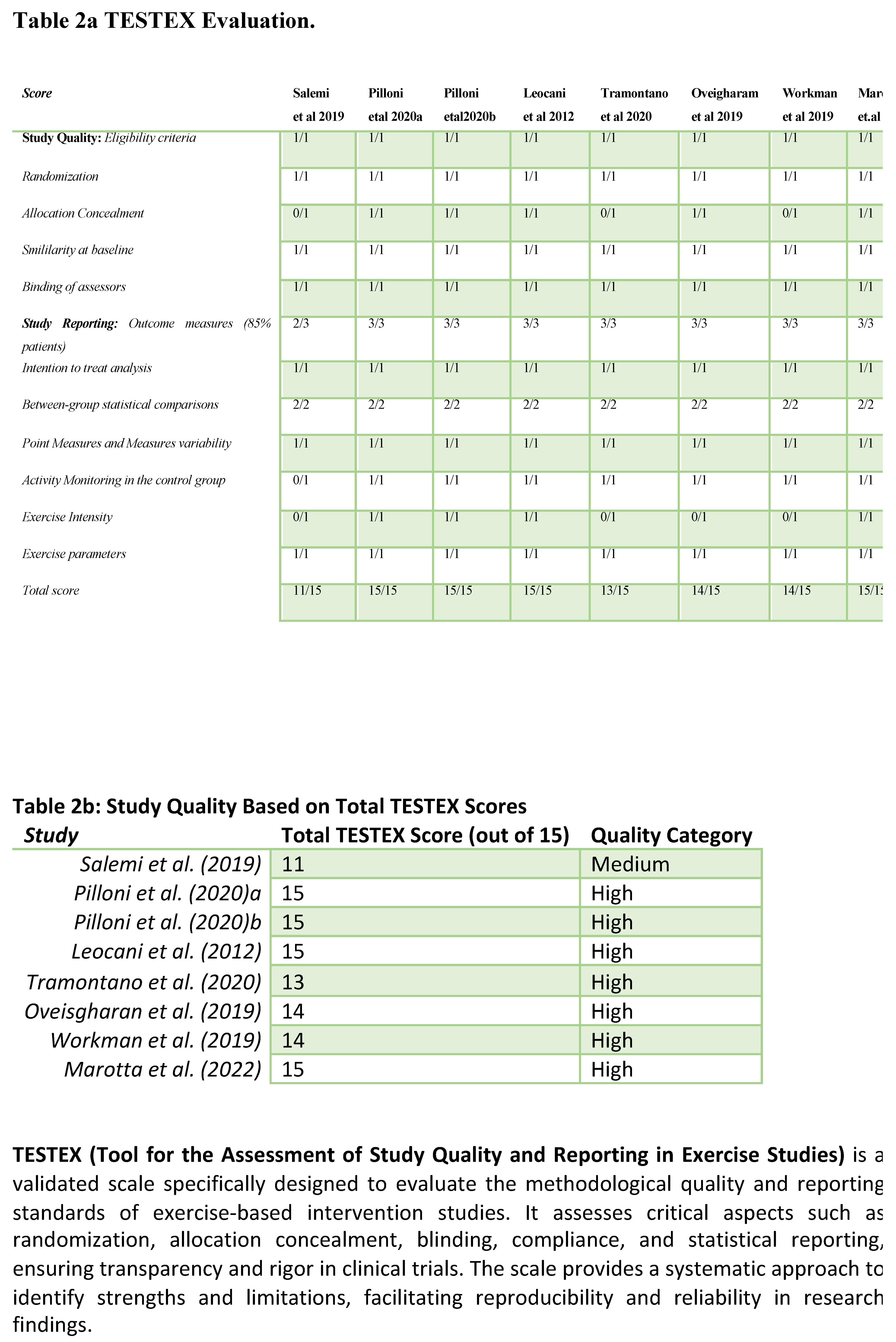

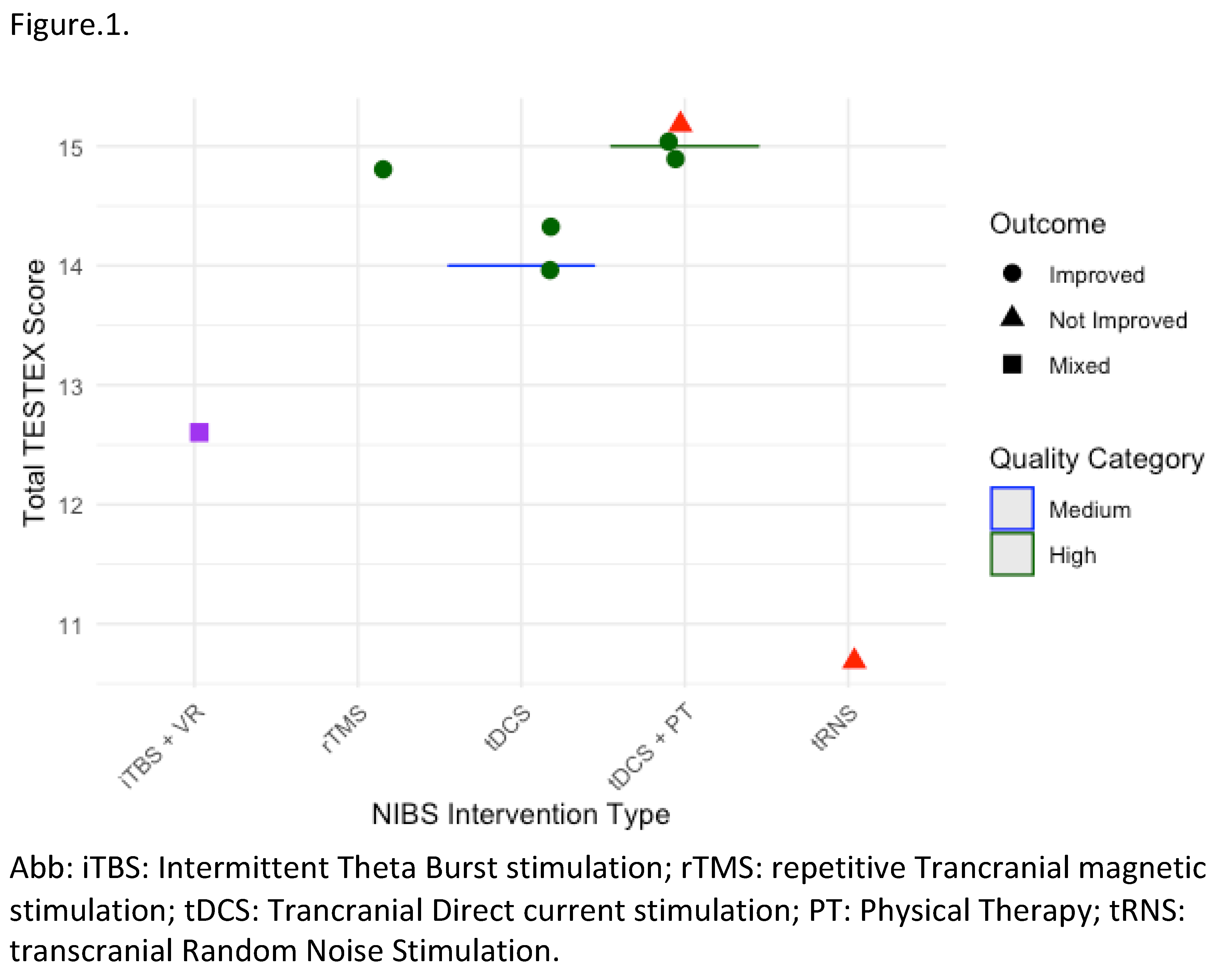

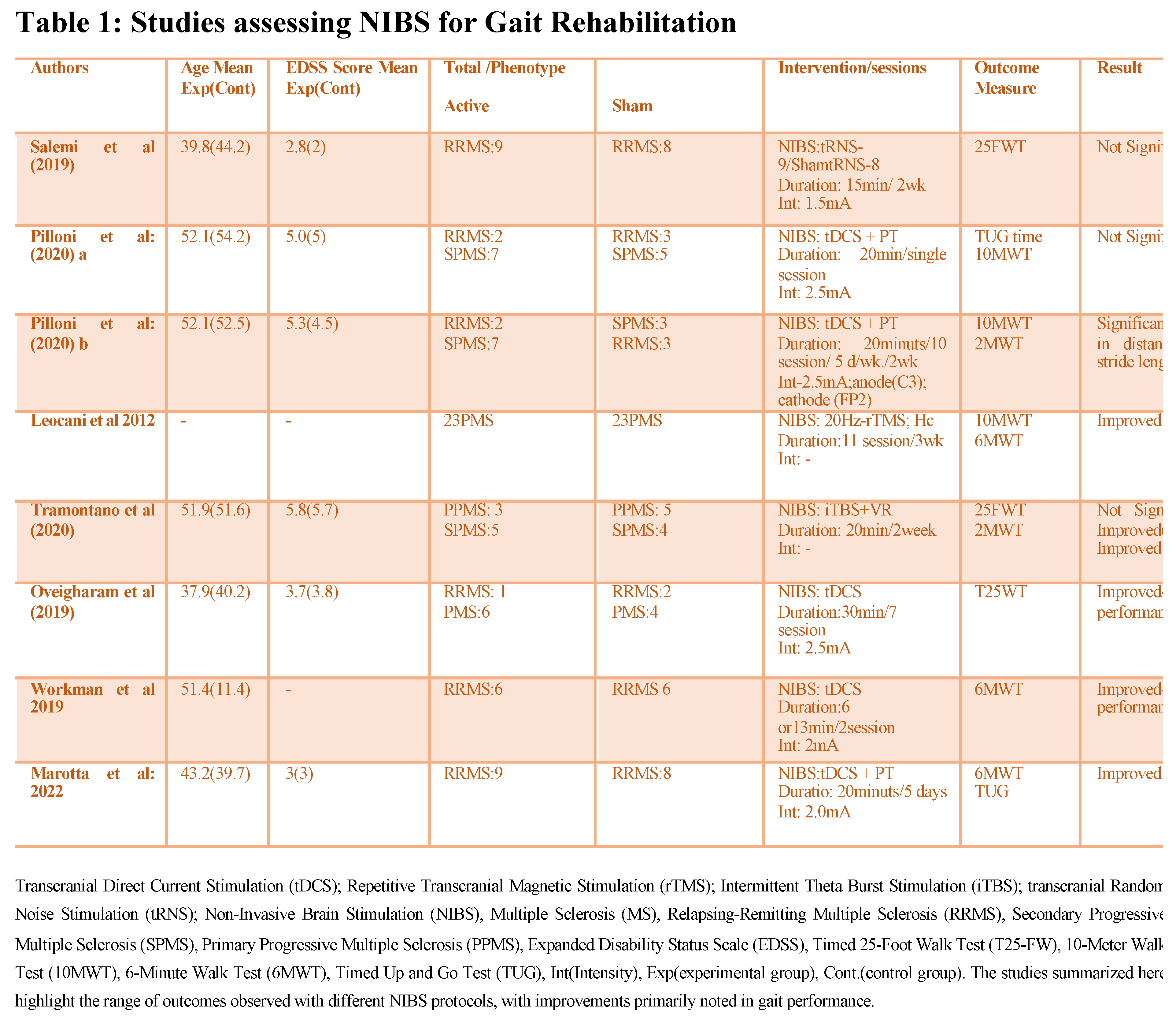

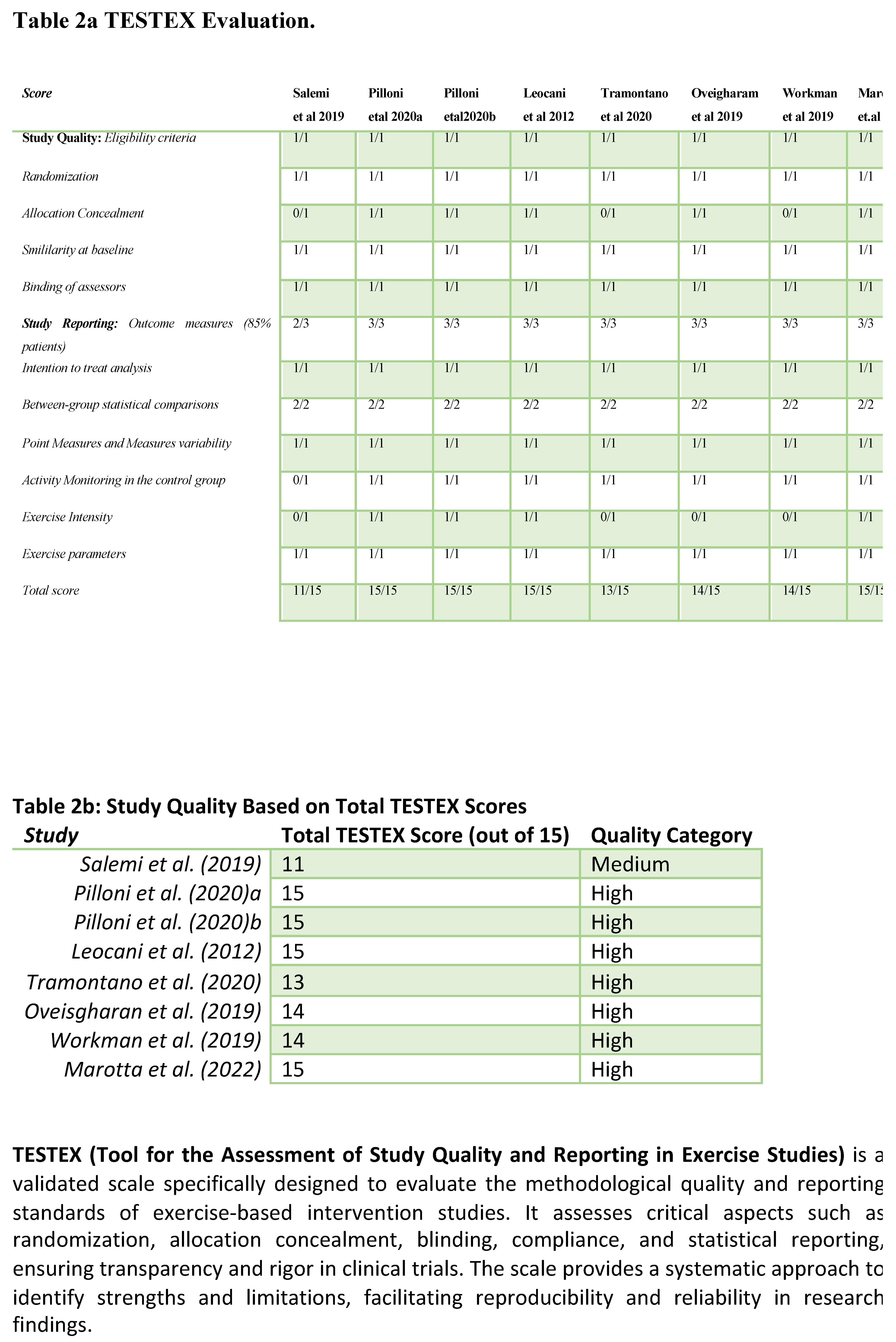

Review of clinical studies on NIBS has shown potential in improving gait in PMS. However, the evidence varies with outcomes dependent on stimulation parameters MS phenotypes and the specific gait metrics assessed Tables 1–3, Figure 1.

Gait Improvement Metrics and Outcomes: Studies have investigated NIBS impact on key gait parameters such as walking speed, endurance, stride length, and spasticity reduction. For instance, Pilloni et al. (2020) used tDCS with physical therapy (PT) over ten 20-minute sessions (2.5 mA, anode at C3, cathode at FP2), reporting significant gains in gait speed, stride length, and endurance in SPMS patients. Improvements in the 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT) and 2-Minute Walk Test (2MWT) metrics suggest that higher-intensity and cumulative sessions of tDCS can reinforce neuroplasticity and motor function gains. In a similar vein, Leocani et al. (2012) applied high frequency rTMS (20 Hz) in 11 sessions over three weeks, demonstrating notable improvements in gait speed and endurance for PPMS patients. Significant improvements in the 10MWT and 6MWT metrics illustrate that repeated high-frequency rTMS sessions can provide meaningful motor benefits particularly for patients with severe spasticity [

81,

82].

Comparative Effectiveness of NIBS Protocols: Evidence shows differences in effectiveness across NIBS protocols. rTMSfor example, frequently shows success in reducing spasticity and enhancing endurance. Leocani et al. (2012) observed sustained spasticity reduction following 11 high-frequency sessions (20 Hz, motor cortex stimulation), whereas Iodice et al. (2015) found that five sessions of 2 mA tDCS did not produce significant improvements in spasticity. These differences suggest that rTMS may engage motor pathways more effectively for spasticity management while tDCS may be more effective when combined with PT and aimed at enhancing other gait parameters. Pilloni et al. (2020) also noted that cumulative tDCS sessions combined with PT (20 minutes, 2.5 mA) improved gait parameters underscoring the importance of session frequency and integration with physical rehabilitation for optimal results. This comparison highlights how session frequency, intensity, and combination with active therapy play key roles in maximizing NIBS efficacy [

81,

83].

Short-term Versus Sustained Effects of NIBS: Although short-term gains in gait and motor function are well-documented sustaining these benefits without continuous sessions presents challenges. Leocani et al. (2012) found that high-frequency rTMS produced immediate gains in gait speed and endurance. however, these benefits diminished within weeks if sessions were not repeated. Mori et al. (2011) observed that cumulative high-frequency rTMS sessions led to longer-lasting improvements indicating that ongoing treatment may be essential to maintain gains. In contrast, Salemi et al. (2019) found that 15-minute, 1.5 mA tRNS (transcranial random noise stimulation) sessions over two weeks did not produce significant changes in T25FWT scores. This outcome highlights that certain NIBS protocols may require higher intensities longer durations or combination with physical therapy to achieve consistent gait improvements [

49,

82,

84].

Patient-Specific Responses and Variability: Some studies indicate that higher-intensity cumulative protocols are more effective in SPMS and PPMS with significant spasticity. Tramontano et al. (2020) combined iTBS (20 minutes) with virtual reality (VR) for two weeks, reporting notable improvements in gait and balance among both PPMS and SPMS patients, suggesting that adjunctive therapy enhances NIBS outcome. Additionally, patient demographics impact outcomes with younger patients and those with shorter disease durations typically showing better responses. Marotta et al. (2022) applied 20-minute tDCS (2 mA) with PT over five days, leading to improved gait velocity in a younger cohort on the 6MWT and TUG (Timed Up and Go) tests [

85,

86]. The absence of established procedures is a significant obstacle to more extensive NIBS in clinical settings. Efforts to generalize results are complicated by the broad variations in intensity duration and electrode placement found in studies. Treatment consistency across clinics would be enhanced by standardized recommendations that take into account the MS phenotype and particular gait abnormalities. The availability of NIBS is limited by accessibility issues, such as the requirement for specialized equipment and skilled staff. Additionally, not all environments can support resource-intensive cumulative sessions, highlighting the significance of protocol optimization to maximize benefits within realistic limitations.

3. Comparison of Outcomes with Conventional Rehabilitation Approaches

When evaluating the outcomes of NIBS in comparison to conventional rehabilitation for gait improvement in pwMS, distinct advantages and some shared benefits emerge.

rTMS/iTBS Versus Conventional Rehabilitation: Studies have demonstrated that rTMS and iTBS, particularly when used alongside traditional PT can enhance gait rehabilitation outcomes. Mori et al. (2011) found that 13 sessions of high-frequency rTMS significantly reduced spasticity and improved gait endurance effects which lasted up to two weeks post-intervention. The combination of HF- rTMS with PT produced more pronounced improvements in walking endurance and LL function compared to conventional PT alone suggesting a synergistic effect between motor cortex stimulation and physical rehabilitation. Similarly, San et al. (2019) observed that iTBS combined with physical therapy led to greater improvements in fatigue, mobility, and quality of life than PT alone. These results indicate that rTMS and iTBS can amplify the benefits of traditional rehabilitation likely by enhancing neuroplasticity in motor pathways critical for gait function [

87,

88].

tDCS Versus Conventional Rehabilitation: Studies examining tDCS combined with PT have also shown encouraging results particularly for improving gait metrics like speed, stride length, and endurance. Pilloni et al. (2020) demonstrated that 10 sessions of 20-minute, 2.5 mA tDCS with concurrent PT produced sustained improvements in gait speed and stride length, with effects lasting up to one month. This finding contrasts with conventional rehabilitation alone, which typically shows only modest, short-term gains in gait performance. However, tDCS outcomes can vary depending on protocol specifics. Oveisgharan et al. (2019) reported significant improvement in the T25FW after seven sessions of 30-minute, 2.5 mA tDCS, whereas Iodice et al. (2015) found no significant reduction in lower limb spasticity after a shorter five-session protocol. These results suggest that sustained and higher-intensity tDCS protocols may be more effective for motor function improvement in MS than conventional therapy alone

(Nombela-Cabrera R, et al. 2023) [

83,

89,

90,

91].

Enhanced Neuroplasticity and Sustained Outcomes: One of the primary advantages of NIBS over conventional rehabilitation alone is its potential to promote long-lasting neuroplastic changes. HF- rTMS, as shown in Leocani et al. (2012), enhanced gait speed and endurance in progressive MS patients beyond the effects seen with PT alone, likely due to its ability to stimulate motor cortex excitability and support neural adaptation. Additionally, combining NIBS with conventional therapy appears to extend the durability of treatment effects. Marotta et al. (2022) observed that tDCS with PT maintained improvements in gait velocity on the 6MWT for weeks post-treatment, whereas similar gains with conventional therapy alone often diminish without ongoing sessions [

82,

86]. Even while it can be helpful, conventional therapy frequently falls short of producing long-lasting improvements in gait impairment associated with MS. Strength and balance exercises are the main emphasis of traditional therapy; while they can be beneficial, they could not adequately address central neuroplasticity. On the other hand, NIBS methods such as rTMS and tDCS target cortical regions that are specifically involved in motor control, providing a mechanism that directly affects neural circuits linked to gait.

4. Tailoring NIBS Protocols Based on Different Gait Impairments

Spastic Gait: with significant spasticity, HF- rTMS targeting the primary motor cortex (M1) has been shown to effectively reduce spasticity and improve gait parameters like stride length and walking speed. Studies indicate that a HF approach (e.g., 20 Hz) over multiple sessions may be optimal for reducing spasticity making it suitable for patients with pronounced muscle tightness impacting gait [

92].

Coordination and Endurance Deficits: In cases where gait impairment is primarily due to poor coordination or reduced endurance, tDCS may be more beneficial. Positioning the anode over M1 and the cathode over the contralateral frontopolar region with moderate intensity (e.g., 2-2.5 mA) for repeated sessions can help improve lower limb coordination and endurance. Studies show that online tDCS during gait training particularly with extended and cumulative sessions enhances outcomes related to gait distance and endurance [

86,

90,

93].

Cumulative vs. Single Session Protocols: For lasting benefits, a cumulative approach with frequent sessions (e.g., 10–15 sessions over 2–3 weeks) tends to show more durable improvements compared to single sessions [

81]. Tailoring session frequency and duration according to patient response can maximize effectiveness especially in PMS where motor impairments are more pronounced.

Progression Stage Considerations: As MS progresses, gait impairments can worsen due to both damage and secondary muscular weakness. Early stages may benefit from higher-intensity frequent protocols to stimulate neuroplasticity and strengthen motor control pathways. In later stages, lower-frequency or shorter-duration protocols may be better tolerated and still provide functional gains without overexerting the patient [

4,

94,

95,

96].

Combination with PT: Studies demonstrate that combining NIBS with PT can enhance the effects of both interventions. incorporating tDCS or rTMS during active gait training can reinforce motor learning and improve walking ability more effectively than NIBS or PT alone [

97].

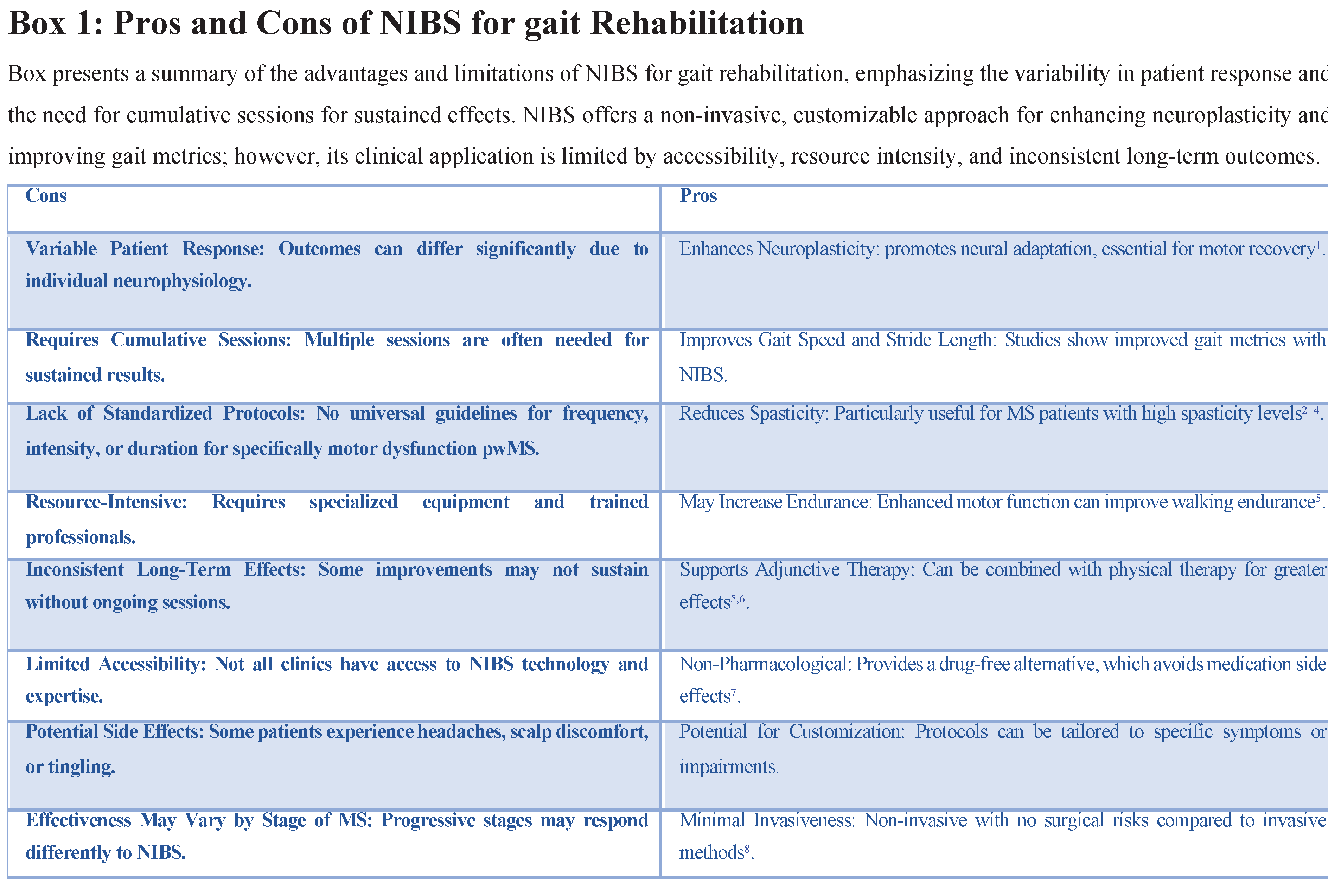

5. Challenges and Limitations

One major limitation is the absence of standardized protocols for NIBS in MS rehabilitation. Studies vary widely in terms of stimulation parameters including intensity, duration, frequency and target areas. This lack of consistency makes it difficult to compare results across studies and limits the ability to establish universal guidelines for clinicians. Standardizing protocols that consider specific MS phenotypes and gait impairments would improve reproducibility and help define best practices for NIBS in MS.

Variability in Patient Responses: Patient response to NIBS is highly variable influenced by individual neurophysiology disease progression and other comorbid conditions. While some patients show marked improvement in gait metrics others experience limited or no benefit from the same protocols. This variability makes it challenging to predict outcomes and complicates efforts to design personalized treatment plans that ensure effectiveness.

Short-Term Versus Long-Term Efficacy:Although many studies report short-term improvements in gait function the sustainability of these effects remains uncertain. Benefits like reduced spasticity and improved gait speed often diminish within weeks if treatment is not maintained. There is limited evidence on the long-term efficacy of NIBS and whether these gains can be sustained without continuous intervention. Addressing this gap requires longitudinal studies to evaluate the durability of NIBS outcomes and to explore protocols for maintaining improvements over time [

98].

Resource and Accessibility Constraints: NIBS requires specialized equipment trained personnel and often repeated sessions which can be resource-intensive. Many rehabilitation centers lack access to the necessary technology and expertise particularly in rural or underserved areas. This limited accessibility restricts the widespread adoption of NIBS for MS gait rehabilitation and poses a significant barrier to equitable care. Solutions such as developing more affordable and user-friendly NIBS devices or establishing home-based stimulation protocols could improve access.

Potential Side Effects and Patient Tolerance: Although NIBS is generally well-tolerated some patients experience side effects like headaches scalp discomfort or tingling sensations. These adverse effects may affect patient compliance especially in protocols that require frequent sessions. Additionally, progressive MS patients with greater fatigue and sensitivity may have lower tolerance for longer or higher-intensity protocols. Balancing effectiveness with patient comfort is crucial and further research on minimizing side effects while maintaining therapeutic benefits is needed.

Gap in Combination Therapy Research: While combining NIBS with PT shows potential to enhance neuroplasticity and functional outcomes there is a lack of in-depth research on how best to integrate these interventions. The optimal timing, duration, and intensity of combined NIBS and PT sessions are not yet well understood leaving room for future studies to explore how to maximize the synergistic effects of these therapies. Clarifying these parameters could help establish protocols that make the most of both approaches for long-term benefits.

Stage-Specific Protocol Development: MS is a progressive disease and gait impairments can vary significantly across different stages. Early-stage patients may respond better to HF and high-intensity NIBS protocols while later-stage patients might require lower-intensity shorter sessions to avoid fatigue. There is currently a gap in research focused on tailoring NIBS protocols to specific stages of MS which could enhance patient outcomes by ensuring the right protocol is used at the right time.

6. Conclusion and Future Directions

Current research demonstrates that personalized NIBS protocols can effectively enhance gait performance in MS patients, particularly when cumulative sessions are used and when stimulation parameters are tailored to individual needs. Both rTMS and tDCS have shown promise in improving metrics like gait speed, stride length, and muscle activation [

87,

89]. However, variability in patient response and the challenges of integrating NIBS into everyday clinical practice limit its broader application. Clinicians need to carefully consider disease stage and specific motor impairments when designing NIBS interventions to maximize their effectiveness. Future research should focus on large-scale clinical trials to determine the long-term efficacy of NIBS in MS, as well as to explore optimal stimulation parameters for different stages of disease progression. Additionally, there is a need to explore combination therapies integrating NIBS with physical therapy cognitive training or pharmacological treatments to enhance overall patient outcomes. Another avenue for future exploration is the development of home-based NIBS systems that allow patients to receive remote stimulation sessions. This would improve accessibility and allow for ongoing treatment without the need for frequent hospital visits [

99,

100]. Moreover, continued research should investigate the mechanisms underlying NIBS to refine its application and understand how it can best support neuroplasticity in pwMS Combining NIBS with traditional physical therapy has been found to boost neuroplastic changes maximizing recovery potential [

97,

101,

102]. Current evidence suggests that NIBS, when combined with traditional physical therapies, may provide additional benefits by facilitating motor cortex activation and reinforcing gait training outcomes.

References

- Ghasemi, N.; Razavi, S.; Nikzad, E. Multiple Sclerosis: Pathogenesis, Symptoms, Diagnoses and Cell-Based Therapy. Cell J 2017, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Amatya, B. Rehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017, 98, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Turner-Stokes, L.; Ng, L.; Kilpatrick, T. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for adults with multiple sclerosis. Postgrad Med J 2008, 84, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; et al. Efficacy of non-invasive brain stimulation on cognitive and motor functions in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1091252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, M.G.; et al. Virtual reality in multiple sclerosis rehabilitation: A review on cognitive and motor outcomes. J Clin Neurosci 2019, 65, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaravalloti, N.D.; DeLuca, J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2008, 7, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: from phenomenology to neurobiological mechanisms. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2024, 131, 871–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højsgaard Chow, H.; et al. Progressive multiple sclerosis, cognitive function, and quality of life. Brain Behav 2018, 8, e00875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; et al. Social cognition in multiple sclerosis and its subtypes: A meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 52, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begemann, M.J.; Brand, B.A.; Ćurčić-Blake, B.; Aleman, A.; Sommer, I.E. Efficacy of non-invasive brain stimulation on cognitive functioning in brain disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2020, 50, 2465–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orio, V.L.; et al. Cognitive and motor functioning in patients with multiple sclerosis: neuropsychological predictors of walking speed and falls. J Neurol Sci 2012, 316, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-C.; et al. Frontal Beta Activity in the Meta-Intention of Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Clin EEG Neurosci 2021, 52, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boes, A.D.; et al. Noninvasive Brain Stimulation: Challenges and Opportunities for a New Clinical Specialty. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2018, 30, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Rothwell, J.; Capogna, M. Noninvasive Stimulation of the Human Brain: Activation of Multiple Cortical Circuits. Neuroscientist 2018, 24, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; et al. The effects of motor cortex rTMS on corticospinal descending activity. Clin Neurophysiol 2010, 121, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, E.M.; Farweez, H.M.; Islam, H. Therapeutic effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor function in Parkinson’s disease patients. Eur J Neurol 2003, 10, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefaucheur, J.-P.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Clin Neurophysiol 2014, 125, 2150–2206. [Google Scholar]

- Lefaucheur, J.-P.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Clin Neurophysiol 2017, 128, 56–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomarev, M.P.; et al. Placebo-controlled study of rTMS for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2006, 21, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-R.; et al. Combination of rTMS and treadmill training modulates corticomotor inhibition and improves walking in Parkinson disease: a randomized trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2013, 27, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchella, C.; et al. Non-invasive Brain and Spinal Stimulation for Pain and Related Symptoms in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 547069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafi, A.; Mohseni-Bandpei, M.A.; Seydi, M. The effect of tDCS on the fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Clin Neurosci 2020, 78, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Valero-Cabre, A.; Pascual-Leone, A. Noninvasive human brain stimulation. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2007, 9, 527–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, H.J.; Newell, P.; Haas, B.; Marsden, J.F.; Freeman, J.A. Identification of risk factors for falls in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther 2013, 93, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethoux, F.; Bennett, S. Evaluating walking in patients with multiple sclerosis: which assessment tools are useful in clinical practice? Int J MS Care 2011, 13, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.L.; et al. Gait and balance impairment in early multiple sclerosis in the absence of clinical disability. Mult Scler 2006, 12, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucic, S.; Burke, D.; Kiernan, M.C. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms and management. Clin Neurophysiol 2010, 121, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer-Alster, S.; et al. Longitudinal relationships between disability and gait characteristics in people with MS. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.L.; et al. Intensive immunosuppression in progressive multiple sclerosis. A randomized, three-arm study of high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide, plasma exchange, and ACTH. N Engl J Med 1983, 308, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, G.R.; et al. Development of a multiple sclerosis functional composite as a clinical trial outcome measure. Brain 1999, 122 Pt 5, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, A.; et al. The timed 25-foot walk in a large cohort of multiple sclerosis patients. Multiple Sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2021, 28, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, M.D.; et al. Clinically meaningful performance benchmarks in MS: Timed 25-Foot Walk and the real world. Neurology 2013, 81, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandell, B.A.; Smirnakis, S.M. Plasticity and stability of visual field maps in adult primary visual cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009, 10, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.J.M.; Zhao, C.; Sim, F.J. Ageing and CNS remyelination. Neuroreport 2002, 13, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzilli, C.; et al. ‘Gender gap’ in multiple sclerosis: magnetic resonance imaging evidence. Eur J Neurol 2003, 10, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonheim, M.M.; et al. Gender-related differences in functional connectivity in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2012, 18, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, H.; et al. Evidence for adaptive functional changes in the cerebral cortex with axonal injury from multiple sclerosis. Brain 2000, 123 Pt 11, 2314–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzapesa, D.M.; Rocca, M.A.; Rodegher, M.; Comi, G.; Filippi, M. Functional cortical changes of the sensorimotor network are associated with clinical recovery in multiple sclerosis. Hum Brain Mapp 2008, 29, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, P.; et al. A longitudinal fMRI study on motor activity in patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain 2005, 128, 2146–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; et al. The motor cortex shows adaptive functional changes to brain injury from multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2000, 47, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werring, D.J.; et al. Recovery from optic neuritis is associated with a change in the distribution of cerebral response to visual stimulation: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000, 68, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, M.A.; et al. Preserved brain adaptive properties in patients with benign multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2010, 74, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audoin, B.; et al. Magnetic resonance study of the influence of tissue damage and cortical reorganization on PASAT performance at the earliest stage of multiple sclerosis. Hum Brain Mapp 2005, 24, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toosy, A.T.; et al. Adaptive cortical plasticity in higher visual areas after acute optic neuritis. Ann Neurol 2005, 57, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.S.; et al. Chronic brain inflammation impairs two forms of long-term potentiation in the rat hippocampal CA1 area. Neurosci Lett 2009, 456, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbetta, M.; Kincade, M.J.; Lewis, C.; Snyder, A.Z.; Sapir, A. Neural basis and recovery of spatial attention deficits in spatial neglect. Nat Neurosci 2005, 8, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, F.; et al. Effects of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation on chronic neuropathic pain in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Pain 2010, 11, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassini, V.; et al. Neuroplasticity and functional recovery in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2012, 8, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J. Neurorehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: foundations, facts and fiction. Curr Opin Neurol 2005, 18, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, V.W.; et al. Constraint-Induced Movement therapy can improve hemiparetic progressive multiple sclerosis. Preliminary findings. Mult Scler 2008, 14, 992–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumowski, J.F.; Wylie, G.R.; Deluca, J.; Chiaravalloti, N. Intellectual enrichment is linked to cerebral efficiency in multiple sclerosis: functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence for cognitive reserve. Brain 2010, 133, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solari, A.; et al. Computer-aided retraining of memory and attention in people with multiple sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. J Neurol Sci 2004, 222, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, N.B.; et al. Evaluation of cognitive assessment and cognitive intervention for people with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002, 72, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portaccio, E.; et al. Cognitive rehabilitation in children and adolescents with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 2010, 31, S275–S278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, S.J.; Levine, P.; Leonard, A. Mental practice in chronic stroke: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Stroke 2007, 38, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Szaflarski, J.P.; Eliassen, J.C.; Pan, H.; Cramer, S.C. Cortical plasticity following motor skill learning during mental practice in stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009, 23, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotze, M.; Cohen, L.G. Volition and imagery in neurorehabilitation. Cogn Behav Neurol 2006, 19, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; et al. Multiple sclerosis: effects of cognitive rehabilitation on structural and functional MR imaging measures--an explorative study. Radiology 2012, 262, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolelis, M.A.L.; Lebedev, M.A. Principles of neural ensemble physiology underlying the operation of brain-machine interfaces. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009, 10, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavazzi, E.; et al. Neuroplasticity and Motor Rehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review on MRI Markers of Functional and Structural Changes. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-Z.; Edwards, M.J.; Rounis, E.; Bhatia, K.P.; Rothwell, J.C. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 2005, 45, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-Z.; Chen, R.-S.; Rothwell, J.C.; Wen, H.-Y. The after-effect of human theta burst stimulation is NMDA receptor dependent. Clin Neurophysiol 2007, 118, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, M.A.; et al. Effects of frontal transcranial direct current stimulation on emotional state and processing in healthy humans. Front Psychiatry 2012, 3, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol 527 Pt 2000, 3, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagg, C.J.; Nitsche, M.A. Physiological basis of transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroscientist 2011, 17, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.S.; Hoffman, R.L.; Clark, B.C. Preliminary evidence that anodal transcranial direct current stimulation enhances time to task failure of a sustained submaximal contraction. PLoS One 2013, 8, e81418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novarella, F.; et al. Persistence with Botulinum Toxin Treatment for Spasticity Symptoms in Multiple Sclerosis. Toxins 2022, 14, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzi, F.M.; et al. Outcomes, complications, and dosing of intrathecal baclofen in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Neurosurgical Focus 2024, 56, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smania, N.; et al. Rehabilitation procedures in the management of spasticity. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2010, 46, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bovend’Eerdt, T.J.; et al. The Effects of Stretching in Spasticity: A Systematic Review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2008, 89, 1395–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, S.; Khamis, S. Effects of functional electrical stimulation on gait in people with multiple sclerosis – A systematic review. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2017, 13, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, D.; Jonsdottir, J.; Zocchi, M.; Regola, A. Effects of balance exercises on people with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil 2007, 21, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widener, G.L.; Allen, D.D.; Gibson-Horn, C. Randomized clinical trial of balance-based torso weighting for improving upright mobility in people with multiple sclerosis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009, 23, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulk, G.D. Locomotor training and virtual reality-based balance training for an individual with multiple sclerosis: a case report. J Neurol Phys Ther 2005, 29, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosperini, L.; Leonardi, L.; De Carli, P.; Mannocchi, M.L.; Pozzilli, C. Visuo-proprioceptive training reduces risk of falls in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2010, 16, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannelli, M.; Borriello, G.; Castri, P.; Prosperini, L.; Pozzilli, C. Early physiotherapy after injection of botulinum toxin increases the beneficial effects on spasticity in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil 2007, 21, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.T.; Jalinous, R.; Freeston, I.L. Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex. Lancet 1985, 1, 1106–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhan, A.M.; Subramanian, P.; Pallaveshi, L.; Barnes, B.; Montero-Odasso, M. Modulation of the Left Prefrontal Cortex with High Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Facilitates Gait in Multiple Sclerosis. Case Rep Neurol Med 2015, 2015, 251829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilloni, G.; et al. Gait and Functional Mobility in Multiple Sclerosis: Immediate Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) Paired With Aerobic Exercise. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deep rTMS with H-Coil Associated with Rehabilitation Enhances Improvement of Walking Abilities in Patients with Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: Randomized, Controlled, Double Blind Study (S49.007). Israeli Research Community Portal https://cris.iucc.ac.il/en/publications/deep-rtms-with-h-coil-associated-with-rehabilitation-enhances-imp/fingerprints/.

- Iodice, R.; Dubbioso, R.; Ruggiero, L.; Santoro, L.; Manganelli, F. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of motor cortex does not ameliorate spasticity in multiple sclerosis. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2015, 33, 487–492. [Google Scholar]

- Salemi, G.; et al. Application of tRNS to improve multiple sclerosis fatigue: a pilot, single-blind, sham-controlled study. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2019, 126, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, M.; et al. Cerebellar Intermittent Theta-Burst Stimulation Combined with Vestibular Rehabilitation Improves Gait and Balance in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: a Preliminary Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Cerebellum 2020, 19, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, N.; et al. Efficacy of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) on Balance and Gait in Multiple Sclerosis Patients: A Machine Learning Approach. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, F.; et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation primes the effects of exercise therapy in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2011, 258, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şan, A.U.; Yılmaz, B.; Kesikburun, S. The Effect of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Spasticity in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. J Clin Neurol 2019, 15, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilloni, G.; et al. Walking in multiple sclerosis improves with tDCS: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2020, 7, 2310–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oveisgharan, S.; Karimi, Z.; Abdi, S.; Sikaroodi, H. The use of brain stimulation in the rehabilitation of walking disability in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized double-blind clinical trial study. Iran J Neurol 2019, 18, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nombela-Cabrera, R.; et al. Effectiveness of transcranial direct current stimulation on balance and gait in patients with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2023, 20, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centonze, D.; et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex ameliorates spasticity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2007, 68, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workman, C.D.; Kamholz, J.; Rudroff, T. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for the treatment of a Multiple Sclerosis symptom cluster. Brain Stimul 2020, 13, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leocani, L.; Chieffo, R.; Gentile, A.; Centonze, D. Beyond rehabilitation in MS: Insights from non-invasive brain stimulation. Mult Scler 2019, 25, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseri, A.; Roozbeh, M.; Kazemi, R.; Lotfinia, S. Brain stimulation for patients with multiple sclerosis: an umbrella review of therapeutic efficacy. Neurol Sci 2024, 45, 2549–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B.H. de S.; Andrade, P.H.S. de & Luvizutto, G.J. Does non-invasive brain stimulation improve spatiotemporal gait parameters in people with multiple sclerosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2024, 37, 350–359. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; et al. Non-invasive brain stimulation enhances the effect of physiotherapy for balance and mobility impairment in people with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2024, 92, 106149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridding, M.C.; Rothwell, J.C. Is there a future for therapeutic use of transcranial magnetic stimulation? Nat Rev Neurosci 2007, 8, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Barrios, K.; et al. Home-based transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and motor imagery for phantom limb pain using statistical learning to predict treatment response: an open-label study protocol. Princ Pract Clin Res 2021, 7, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Charvet, L.E.; et al. Remotely supervised transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Results from a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Mult Scler 2018, 24, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsaei, M.; et al. Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on gait and balance of persons with Multiple Sclerosis: A narrative review. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2024, 82, 105415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhaleem, N.; et al. Combined Effect of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation with Mirror Therapy for Improving Motor Function in Patients with Stroke: a Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 2024, 12, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).