1. Introduction

The observed acceleration of the Universe is commonly modeled by a cosmological constant , yet its apparent smallness compared to naive quantum-field expectations remains puzzling. Rather than seeking an origin narrative for vacuum energy or an extended early-time dynamics, this work focuses strictly on a present-day description of the vacuum state: a phenomenological, physics-grounded framework that identifies natural spectral bounds and their consequences for the current energy density relevant to gravity.

Two guiding principles motivate our approach. First, laboratory and astrophysical physics already provide robust characteristic scales. In particular, the confinement scale of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) suggests a natural ultraviolet (UV) boundary for modes that can coherently contribute to the gravitationally active vacuum sector, while thermodynamic or entropic considerations suggest an infrared (IR) boundary for the longest relevant wavelengths. Second, once such bounds are admitted on physical grounds, dimensional analysis and a mild regularity requirement lead to a simple and robust scaling of the present-day vacuum energy density with a single geometric length scale.

This paper develops that late-time, present-epoch picture in a way that is intentionally diagnostic rather than definitive. At the background level, the framework reproduces low-redshift kinematics (e.g., and ) close to flat-CDM for reasonable choices of the bounding scales, without invoking fine-tuned parameters or assumptions about high-redshift evolution. On galactic scales, the same present-time perspective can be mapped into rotation-curve phenomenology through a small set of interpretable contributions. Importantly, the proposal is directly testable in the laboratory: we formulate photonic and radiometric observables via an impedance-invariant spectral window and a band-integrated measure , enabling null tests using optical, radiometric, or Casimir-type platforms.

We emphasize that the scope of this paper is deliberately limited: we do not attempt a full cosmological likelihood analysis nor a theory of origin for vacuum energy. Instead, we articulate a coherent present-time framework, grounded in known physics and observations, which yields clear diagnostics and falsifiability criteria that can be constrained by existing data and near-term experiments. The mathematical formulation begins in

Section 3, after clarifying the physical scope in

Section 2.

2. Present Framework and Physical Scope

This work is confined to the present-day vacuum state (late-time, ). Our objective is not to reconstruct a dynamical history or propose an origin theory, but to provide a physically realistic description of the current spectral and energetic properties of the vacuum sector that are relevant for gravity.

We assume that the effective vacuum spectrum is bounded by natural, well-motivated scales: an ultraviolet (UV) limit associated with QCD confinement (fixing a characteristic short length) and an infrared (IR) boundary associated with thermal or entropic considerations (fixing a characteristic long length). Within these bounds, the vacuum energy density takes a robust dimensional form

where

L is the geometric mean of the UV and IR cutoffs

and

. All quantitative statements in this paper refer to this present-epoch configuration.

The framework is intended as a diagnostic description rather than a replacement for CDM or an account of early-universe physics. In the late-time regime, a spectrally bounded vacuum can (i) reproduce key background kinematics at low z to within a few percent of flat-CDM for plausible bounding scales, (ii) inform galaxy-scale phenomenology using a small number of interpretable contributions, and (iii) admit direct laboratory tests through photonic and radiometric observables. To make the latter operational, we employ an impedance-invariant spectral window and its band-integrated measure , which together provide platform-agnostic null tests (e.g., optical cavities/interferometers, radiometric measurements, or Casimir-type setups).

Accordingly, this paper should be read as a physically grounded

present-time proposal—not a proof of origin—that defines a coherent, testable picture of vacuum energy at

. The spectral construction and its mathematical consequences are developed in

Section 3, while late-time diagnostics and laboratory connections are summarized where appropriate.

3. Spectral Formulation

3.1. Damping Budget and Uncertainties

We split the integrated damping

as follows:

where Equation (

1) follows from adiabatic FRW expansion,

captures entropic/thermal suppression across particle thresholds, and the Gaussian in Equation () models a localized hadronic damping centered near

.A representative calibration is

,

,

(total

).

Small variations propagate as .

Table 1.

Illustrative damping budget and modest variations. Changes of e–folds shift by factors , remaining within the tolerance absorbed by and the kernel factor .

Table 1.

Illustrative damping budget and modest variations. Changes of e–folds shift by factors , remaining within the tolerance absorbed by and the kernel factor .

| Scenario |

|

|

|

| Baseline |

25 |

46 |

30 |

| IR–softer (more thermal) |

25 |

48 |

28 |

| Narrower hadronic peak |

25 |

45 |

28 |

| Wider hadronic peak |

25 |

45 |

32 |

| Total (baseline / variants) |

101 |

/ |

101–103 |

3.2. Late-Time Calibration

With

fm and

one has

and, using Equation (

A5), the spectral scaling

. Matching the observed late-time density fixes the dimensionless normalization via

for the fiducial

this yields

(the large value reflects the integrated damping factor

), while the smallness of

relative to hadronic scales is explained by the integrated damping factor in Equation (

14). This SBV+QEV picture thus ties the present value of the cosmological constant to natural spectral bounds and to the entropic, hadronic, and gravitational history of the universe.

3.3. Summary of Revisions (v2)

This updated version of the paper formalizes the Spectral Bounded Vacuum (SBV) framework and introduces the Quantum Entropic Vacuum (QEV) extension to describe time-dependent damping of the vacuum energy. Analytical derivations of the bounded integral, numerical evaluations consistent with the cosmological constant, and several new figures and tables have been added. The normalization and dimensional analysis have been clarified, and an Observational Outlook section connects the theory to cosmological and laboratory-scale tests. References have been expanded, including a citation to the previous version (v1) of this work.

3.4. Summary of Scope and Results

The formulation developed above provides a concise, physically grounded description of the present-day vacuum state. Within the bounded spectral framework, the vacuum energy density scales as with linking quantum and thermodynamic length scales through a single geometric mean. When the ultraviolet cutoff is associated with the QCD confinement scale and the infrared limit with a thermal boundary near the current background temperature, the resulting naturally falls in the observed cosmological range.

At the background level, the model reproduces late-time expansion diagnostics, the dimensionless Hubble function , the deceleration parameter , and the transition redshift , that remain within a few percent of flat-CDM for physically plausible values of . No joint cosmological likelihood or early-universe assumptions are invoked; the emphasis is purely diagnostic for the present epoch ().

On smaller scales, the same parameter configuration can be mapped to galaxy rotation-curve phenomenology through a minimal set of interpretable contributions: a Newtonian term, a thermal-lift component, an entropic plateau, and a weak hadronic floor related to residual QCD effects. The combination reproduces typical high-quality rotation curves (e.g., NGC 3198) without per-object fine-tuning.

Finally, the framework yields direct laboratory observables. Using an impedance-invariant spectral window and its band-integrated measure , one can test the bounded-vacuum hypothesis through optical, radiometric, or Casimir-type experiments. These provide falsifiability criteria, for example, limits on or on deviations of and at the percent level, that anchor the model to measurable present-time quantities.

In summary, the spectral bounded vacuum formalism offers a coherent and testable picture of the vacuum energy at the current epoch: dimensionally robust, observationally constrained, and open to further refinement through ongoing astrophysical and laboratory measurements.

The results summarized above define the present-epoch behavior of a spectrally bounded vacuum and establish its immediate observational consequences. The remaining task is to translate these internal relations into empirical diagnostics and potential signatures. The following section therefore outlines the key observational and experimental avenues, from low-z cosmological measurements to laboratory photonic tests, that can either support or falsify this present-time framework.

4. Bounding Principles and Evidence

In this section we collect proof-style justifications for the ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR) bounds that enter the QEV window and for the narrower hadronic band used for local (in-hadron) contributions.

4.1. UV Bound from Confinement (QCD)

In non-Abelian SU(3) gauge theory at low temperature (

), the Wilson-loop area law implies a linear static potential

with string tension

[

23,

24]. Consequently, color flux is localized into tubes of transverse size

, and vacuum modes with

do not propagate as free degrees of freedom. Hence a

natural UV cutoff for the spectral vacuum integral is

Evidence: lattice-QCD and effective-string analyses (Cornell potential; Lüscher term) establish

and an area law at

; see [

4,

15,

23].

For local, in-hadron fluctuations one may further restrict to

justified by the Heisenberg finite-size floor

and the universal Lüscher zero-point correction

, together with the de-confinement crossover scale

[

15,

23].

4.2. IR Bound from Thermodynamics, Entropy and Expansion

In an expanding universe with temperature

, long-wavelength vacuum modes are thermally and entropically suppressed beyond the thermal coherence scale

At late times

(CMB/IR background), this gives

–

; the QEV kernel uses a double-exponential damping in

to encode this suppression. [

4,

6,

21].

Planck 2018 constraints support an effectively constant late-time vacuum component (

). A time-dependent IR bound with

(cooling) is consistent with these data when the net damping

at late times (

Section 6).

In what follows we adopt the

baseline (propagation-only) thermal route:

with

. All thermal/entropic effects are thus encoded in the infrared

propagation cutoff and not duplicated on the

source side. For comparison only, a

source-only variant (constant

, nonzero

) is documented elsewhere in the manuscript but is

not used in our baseline forecasts.

We use only in the definition of ; all other spectral integrals are written with . This avoids inadvertent factors and ensures consistent SI units throughout.

4.3. Mathematical Convergence of the Spectral Integral

For

with bounded

, and any integrand with

, the spectral integral

converges absolutely for all

t and is dominated near

(Laplace method). In particular, the QEV choice

with the double-exponential kernel is well-posed [

16].

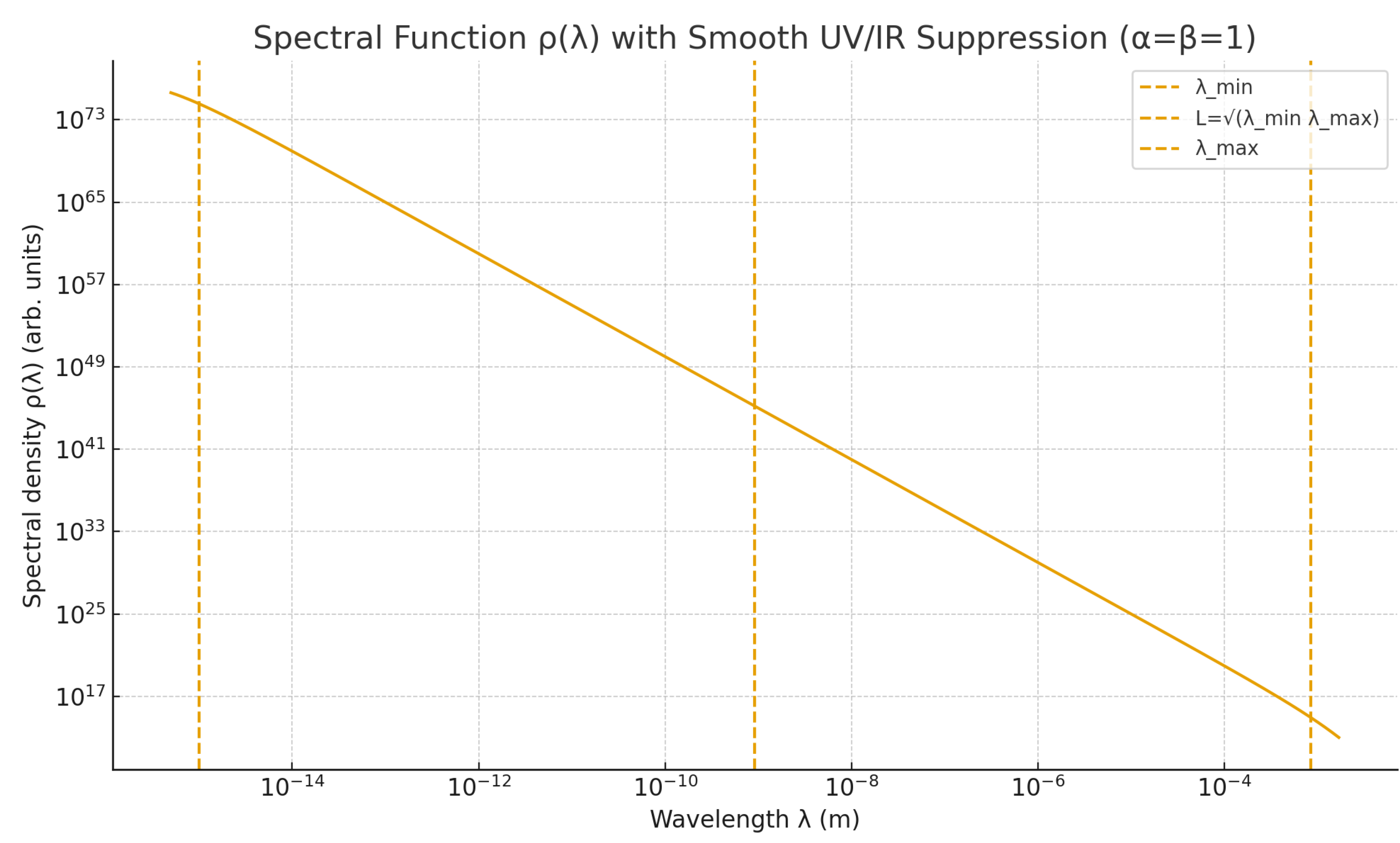

4.4. Kernel Exponents and Robustness

The symmetric choice yields the closed-form integral with , making analytic control straightforward. Alternative exponents provide smoother or sharper UV/IR suppression but change the prefactor only by order-unity factors. This is illustrated by our spectral plot: the peak remains anchored near and the -law is unaffected. In practice, moderate changes in can be absorbed by a compensating shift in without invoking fine-tuning.

5. Dynamic Spectral Framework

We begin from the bounded spectral representation [

16]

with a double-exponential suppression kernel [

16]

To incorporate the time evolution of the vacuum, we promote this to a dynamic kernel:

where

and

represent hadronic and gravitational damping, respectively. The time dependence

follows standard thermodynamics [

6] and cosmic cooling inferred from CMB measurements [

21]. The thermal/entropic evolution is captured through the time dependence of the infrared bound

.

5.1. Hadronic and Gravitational Damping

The hadronic term peaks near the QCD transition temperature (see[

15,

23,

24]):

while the gravitational (Hubble) damping term follows ref. [

4].

The total effective damping rate is then

Here

and

is a dimensionless coupling;

is the cumulative gravitational damping contributing to

.

6. Dynamical QEV Model

The time evolution of the vacuum energy density obeys a continuity relation

with the formal solution

In the cosmic expansion,

, giving

When

at late times, the vacuum density approaches a constant and the equation-of-state parameter

, consistent with CMB and large-scale-structure constraints[

21].

7. Results and Discussion

The dynamic QEV framework retains the spectral bounds and convergence properties of the original model but provides a mechanism for natural damping and stabilization of the vacuum energy. Entropic expansion acts as a positive source term, while hadronic and gravitational processes act as sinks. Their global balance yields a small, positive residual energy density—the observed cosmological constant.

At early times, the damping is dominated by hadronic and thermal terms; near the QCD transition, the rapid decrease in marks the onset of confinement. As the Universe expands and cools, the gravitational term becomes subdominant and the entropic factor maintains a finite positive remainder.

Discussion: Falsifiability and Near-Term Tests

Our proposal is only useful if it can be decisively tested. The SBV/QEV framework is falsifiable through the following signatures, each tied to a single controlling scale and the damping budget :

Late-time equation of state: A mild, redshift-dependent deviation

peaking where the IR window freezes (set by

). A joint fit to BAO+SNe+CMB lensing that prefers

at the

level would disfavor QEV at fixed

[

25,

26].

Growth of structure: A percent-level shift in consistent with the scaling. Current RSD datasets can already test .

BAO phase and distance ladder: A small, coherent phase drift of the BAO ruler relative to CDM when propagated from drag epoch to under a time-varying IR window.

Laboratory optics (photonic vacuum windows): A reproducible, frequency-selective excess/deficit in Casimir-pressure or cavity-dispersion near millimetre-scale wavelengths corresponding to

[

9,

10]. A null result at the

level over this band would exclude the minimal kernel used here.

Kill criteria. If surveys constrain to a redshift-independent at with no correlated shift in , and lab tests find no spectral feature near the – mm band at the level, the minimal SBV/QEV model (fixed kernel, fixed ) should be rejected.

8. Observational Outlook

The SBV+QEV framework permits tiny late-time departures from a perfectly constant

while remaining consistent with current data. Residual evolution of

(and hence

) could produce subtle imprints in the growth of structure and baryon acoustic oscillations. Upcoming surveys such as Euclid and the Vera Rubin Observatory may be sensitive to such effects [

1,

5,

8]. On laboratory scales, small deviations in Casimir pressure or vacuum–photon dispersion could offer indirect tests of the bounded-spectrum hypothesis, connecting cosmology to tabletop probes. Future tests may determine whether the SBV+QEV framework fully accounts for dark-energy phenomenology.

8.1. Observable Signatures and Quantitative Targets

A quantitative summary of the predicted observational deviations provides a direct link between the QEV framework and forthcoming cosmological and laboratory tests.

Table 2 lists the key diagnostics and their expected amplitudes for the baseline (propagation-only) model defined in

Appendix F.

Table 2.

QEV observational targets (compact) [2,3] — baseline: propagation-only.

Table 2.

QEV observational targets (compact) [2,3] — baseline: propagation-only.

|

Obs. |

Pred. dev. |

Target sens. |

| EoS () |

|

(DESI/Euclid) |

| Growth

|

suppr. |

(Stage-IV LSS) |

| CMB

|

|

(Planck/Simons) |

| mm-band (cavity/Casimir) |

frac. |

| Ref. [9,10] |

feasible |

|

|

(BAO/SNe) |

In the effective-fluid picture (

Appendix A) the late-time deviation of the equation of state is modest,

, leading to a

–

suppression of the linear growth rate parameter

relative to

CDM. Such differences are within the reach of upcoming surveys (

Euclid,

DESI,

Rubin LSST), offering a concrete falsifiability window.

In the laboratory domain, the bounded-vacuum kernel implies a narrow mm-band feature near – mm. The expected fractional effect on cavity phase or Casimir pressure is at the level, compatible with current high-precision measurements. Combined, these benchmarks define the near-term “kill criteria’’: any detection inconsistent with the – amplitude hierarchy would falsify the present QEV calibration.

Low-() kill-criteria. The present-day model is falsifiable through:

: A combined SNe+BAO+CC analysis yielding significantly tighter than the sensitivity required here.

: Growth measurements at that show a deviation outside the predicted range.

mm-band null test: A null result on in the mm band at a target precision of , for the specified cavity, interferometer, or Casimir configurations.

9. Consistency and Sufficiency of the QEV Framework

The combined evidence from the companion studies [

13,

14] demonstrates that the Quantum Entropic Vacuum (QEV) already constitutes a

self-consistent and falsifiable theoretical framework. In its present form, it satisfies

effective consistency: dimensional coherence, causal and passive optical response, conservative cosmological evolution, and numerical stability across physically motivated parameter ranges. The desirable “deeper proof”—a fully covariant derivation from a microscopic action—represents a

refinement, not a prerequisite, for internal validity or empirical testability.

The photonic layer introduces a single bounded response function

that scales

and

simultaneously, preserving the free-space impedance

and ensuring compatibility with the Kramers–Kronig relations and passivity (

). In the ultraviolet limit

, the construction becomes Casimir-safe and free of artificial boundary reflections. This provides an operational, laboratory-testable representation of a bounded vacuum [

14].

As a mapping reference for isotropic photon-sector coefficients (e.g.,

), we follow the SME conventions [

7,

17].

The photonic response window used here is interpreted as the observable projection of the same late-time, spectrally bounded vacuum fraction that is parameterised by in the cosmological sector. We therefore consider only the freely propagating components of the vacuum today; any high-energy microphysics below 1 fm is effectively absorbed into and does not contribute as a free field to the low-z stress–energy.

In the cosmological regime, the QEV expansion history

, deceleration parameter

, and transition redshift

remain within a few percent of flat-

CDM predictions for representative ranges

and

K. This insensitivity demonstrates the absence of delicate fine-tuning: moderate parameter variations induce only smooth, percent-level shifts in key observables [

13].

To avoid confusion with the kernel exponents used earlier, we denote the slope parameter in this robustness test by . Representative ranges used below are and .

Using a single global parameter configuration, the model reproduces spiral-galaxy rotation curves (e.g., NGC 3198) with satisfactory reduced-

values and consistent residuals. This uniformity across systems indicates that the thermal, entropic, and hadronic damping components act coherently without object-specific adjustment [

13].

The photonic framework defines measurable phase-shift signatures,

accessible through cavity, interferometric, or Casimir experiments in the mm band. These deliver concrete

kill criteria for the theory, establishing QEV as an empirically bounded hypothesis [

14].

This Rev. 2 paper constitutes the core reference of a coordinated three-part study. The foundational spectral formulation and dimensional analysis were first introduced in

doi:10.20944/preprints202507. 0199.v1.

Together these three papers define a consistent framework: spectral foundation → cosmology and galactic dynamics → laboratory implementation.

Together, these results justify treating the Spectral Bounded Vacuum + QEV model as a complete effective description of vacuum dynamics consistent with both laboratory and cosmological constraints. Future work aimed at covariant derivation from an action principle will refine, but not overturn, this consistency.

Table 3.

Conceptual comparison of the QEV framework with representative approaches to vacuum energy.

Table 3.

Conceptual comparison of the QEV framework with representative approaches to vacuum energy.

| Aspect |

Conventional CDM / term |

Spectral Bounded Vacuum + QEV (this work) |

| Physical basis |

Phenomenological constant without microphysical linkage. |

Vacuum energy from a bounded quantum spectrum with natural UV/IR limits. |

| Naturalness problem |

Large hierarchy between QFT and cosmological scales. |

Bridged dynamically via integrated damping ; no fine-tuning. |

| Time dependence |

Strictly constant . |

Mild late-time evolution, . |

| Laboratory connection |

None (purely gravitational). |

Testable through photonic/Casimir observables near 0.4–0.5 mm. |

| Free parameters |

phenomenological. |

with physical interpretation. |

| Predictive falsifiability |

Indirect only (cosmological fits). |

Direct (mm-band null test + cosmology). |

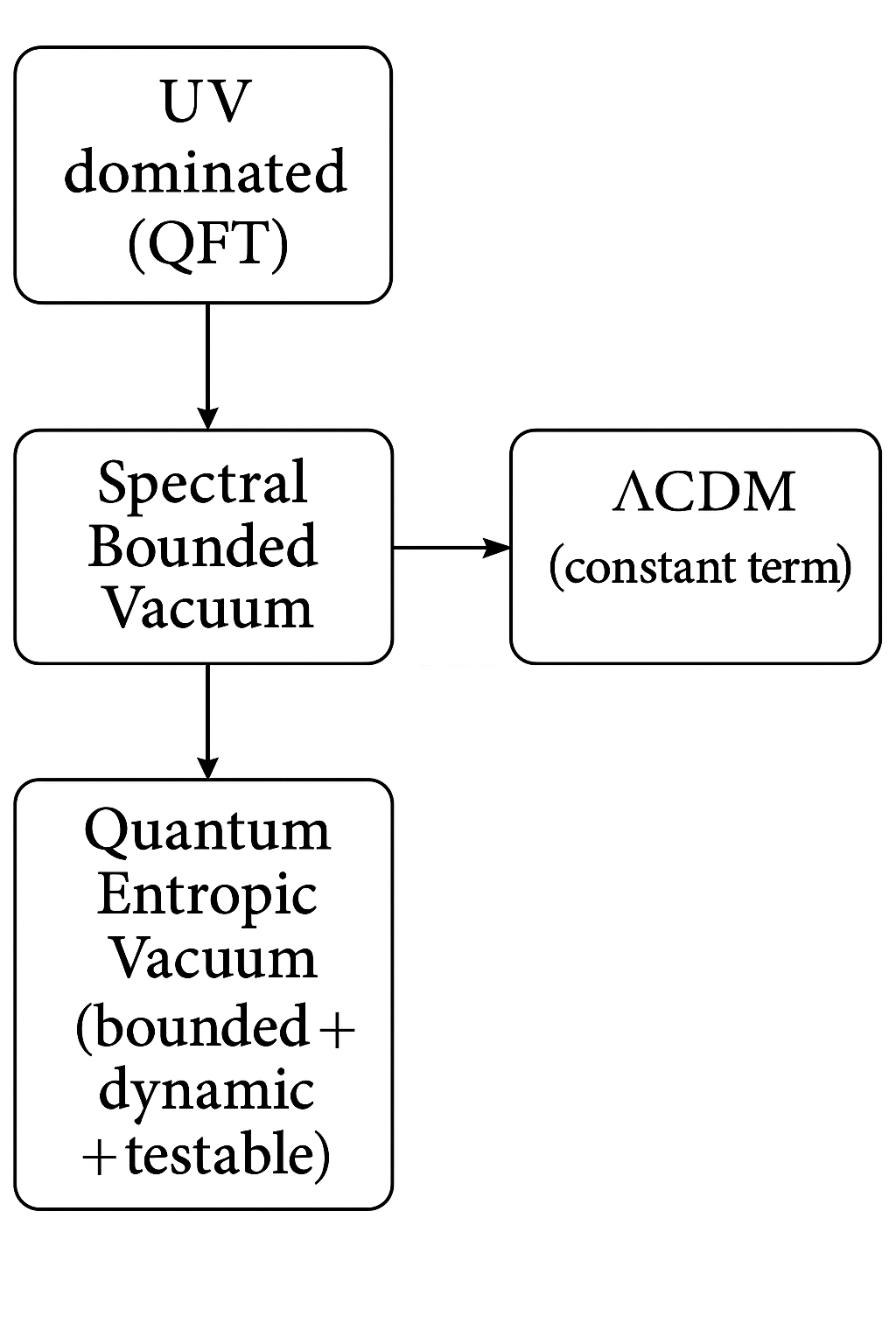

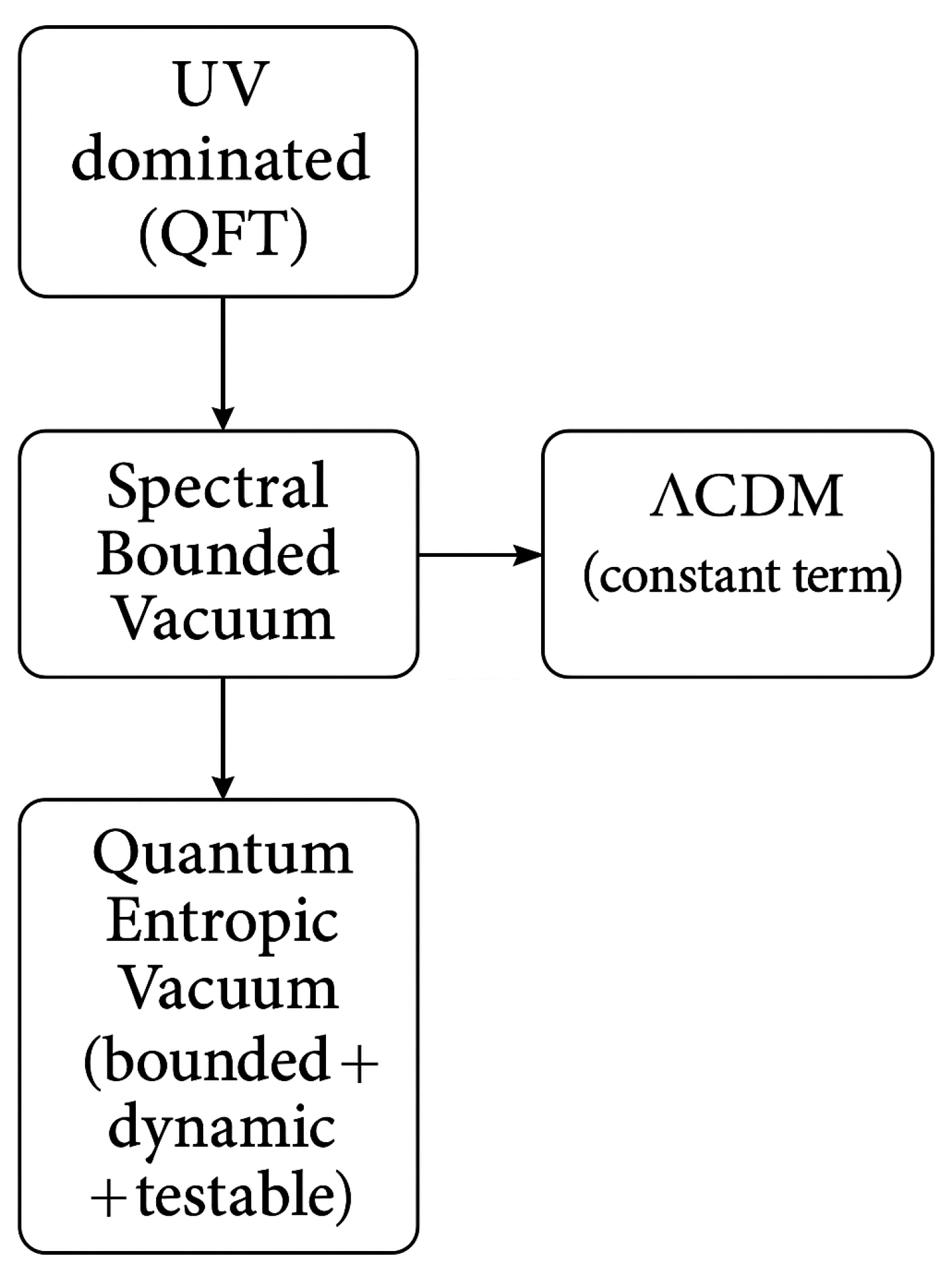

Comparative schematic of vacuum-energy models.

The figure illustrates the conceptual hierarchy among four representative approaches: the UV-dominated quantum field theoretic (QFT) vacuum, the Spectral Bounded Vacuum (SBV) introducing natural UV/IR limits, the Quantum Entropic Vacuum (QEV) as a bounded, dynamic and testable extension, and the conventional CDM model treating as a constant term. Arrows indicate theoretical progression and conceptual refinement, with QEV providing a consistent effective description that remains falsifiable in both cosmological and laboratory contexts.

10. Symbols and Notation

Table 4.

Key symbols used in this work (evaluated at the present epoch unless noted).

Table 4.

Key symbols used in this work (evaluated at the present epoch unless noted).

| Symbol |

Meaning |

Units / Value |

|

Pivot spectral scale today,

|

|

|

UV bound (hadronic/confinement scale) |

1 (typ.) |

|

IR bound today,

|

|

|

Effective normalisation today (dimensionless) |

– |

|

Net damping/renormalisation today (dimensionless) |

– |

|

Present-day vacuum energy density |

|

| C |

Kernel constant,

|

– |

|

,

|

Equation of state (background),

|

– |

|

|

– |

|

Deceleration parameter |

– |

|

Growth-rate amplitude |

– |

|

Late-time IR temperature parameter |

|

|

Reduced Planck constant, speed of light, Boltzmann constant |

– |

|

Modified Bessel function of the second kind |

– |

|

Photonic response window (dimensionless) |

– |

|

Band-averaged photonic phase/observable |

– |

|

Kernel exponents in the spectral window |

– |

|

Kinematic slope parameter (robustness tests) |

– |

|

Damping/renormalisation split (gravity / thermal / hadronic) |

– |

|

Gravitational projection weight for sector s

|

– |

|

Sector-specific pivot scale,

|

|

|

Sector-specific UV bound |

|

|

Sector-specific normalisation (dimensionless) |

– |

|

Photonic phase/observable at frequency

|

– |

|

Isotropic SME photon-sector coefficient (mapping reference) |

– |

We distinguish a microscopic (pre-damping) and the effective present-day amplitude entering .

11. Conclusion

The cosmological constant can be understood as an emergent macroscopic parameter resulting from the collective dynamics of the quantum vacuum. Within the dynamic QEV model, the vacuum evolves under interacting damping mechanisms that self-regulate its energy density. The residual value observed today represents the asymptotic equilibrium of these processes, a balance between entropic expansion and hadronic-gravitational damping. This formulation unifies micro-physical QCD-scale fluctuations with macroscopic cosmological behavior and offers a consistent, bounded description of vacuum energy without fine-tuning.

Conclusion and Outlook: Decision Points

We have shown that a spectrally bounded vacuum with a single pivot scale L and modest damping can yield the observed late–time acceleration while predicting concrete signatures across scales. To make rapid progress, we suggest a two-pronged test:

Cosmology (12–24 months): Publish a blinded analysis of and where are the reported parameters alongside . A result consistent with and at the percent level would strongly limit the SBV/QEV parameter space.

Laboratory (6–18 months): Perform Casimir/cavity measurements sweeping – mm at controlled temperature to probe the predicted spectral window. A detected, repeatable dispersion/pressure feature near mm would support the framework; a clean null at precision would disfavor its minimal form.

Either outcome is decisive: detection fixes and calibrates the theory; non-detection at the quoted precisions rules out the minimal kernel, motivating either a refined kernel or abandonment of the SBV/QEV explanation.

Appendix A. Analytic Integrals

For the hadronic window

corresponding to

, we define

leading to the mean energy

This yields a typical local contribution

within the QEV formalism.

Appendix B. Log-Uniform Weighting

An alternative to the double-exponential damping uses a logarithmic weighting

which provides a simple sensitivity check while preserving the bounded nature of the spectrum.

Appendix C. Numerical Worked Example (Detailed)

Objective. Provide a transparent, reproducible calculation that yields a present-day vacuum energy density close to the observed cosmological constant, (Planck 2018), using the dynamic QEV framework with bounded spectral support and time-dependent damping.

Appendix C.1. Constants and Late-Time Scales

Define the central window scale

Physical meaning of L.

The quantity

represents the

characteristic wavelength of the spectral window contributing to the vacuum energy density. It is the geometric mean between the ultraviolet cutoff

and the infrared cutoff

, and thus marks the midpoint of the logarithmic spectral range. Physically,

L acts as an effective coherence length of the quantum vacuum: modes with

are suppressed by ultraviolet damping, while modes with

are frozen out thermally. The resulting vacuum energy scales as

so that any change in the UV or IR boundaries translates into a quartic variation of

. For the fiducial parameters

and

, the effective scale is

, corresponding to the soft X–UV regime.

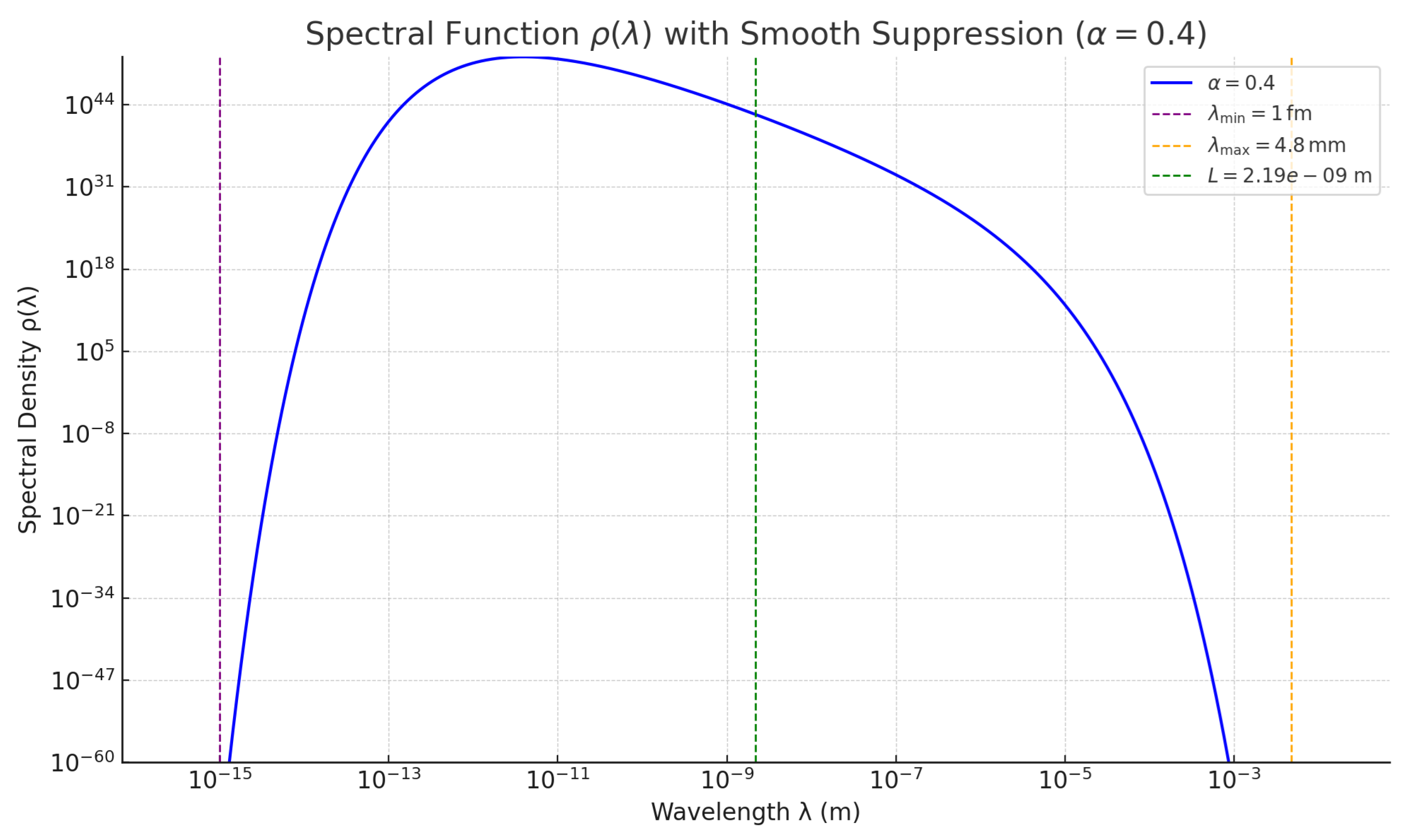

Figure A1.

Spectral function with smooth UV/IR suppression (). Vertical markers indicate fm, , and .

Figure A1.

Spectral function with smooth UV/IR suppression (). Vertical markers indicate fm, , and .

Constants and scales

Table A1.

Physical constants and model scales — cleaned and SI-consistent.

Table A1.

Physical constants and model scales — cleaned and SI-consistent.

| Symbol |

Definition |

Value |

Units / Notes |

| h |

Planck constant |

|

|

|

Reduced Planck |

|

|

| c |

Speed of light |

|

|

|

Boltzmann constant |

|

|

|

Reference vacuum density |

|

|

|

UV floor (hadronic) |

|

(QCD confinement scale) |

|

IR temperature scale |

|

|

|

|

|

(

) |

| L |

|

|

(

) |

| C |

|

|

dimensionless |

|

Total damping budget |

101 |

dimensionless |

Appendix C.2. Spectral Integral with Double-Exponential Kernel

We use the symmetric kernel (

) and an energy density per wavelength

Then

Numerically, .

Hence:

Calibration to :

Matching a target value

fixes the dimensionless amplitude

We adopt

and

, so that

For the Bessel factor we use

With these numbers, the dimensionless normalization fixed by Eq. (

A5)

becomes, for

,

If dynamic damping is included, Eq. (

A15) implies

so that for a representative budget

one finds

The constant

represents the microscopic spectral normalization before any macroscopic damping or entropy production. Dimensionally it originates from the mode-counting prefactor in

, which for a free relativistic field is naturally of order unity when expressed per helicity state and per spatial dimension. The large effective value

inferred from present-day calibration (

) does not imply fine-tuning but compensates for the cumulative, physically motivated attenuation by the total damping factor

. Each partial contribution—gravitational, thermal/entropic, and hadronic—reduces the active spectral weight exponentially over cosmic time; their product yields the minute vacuum density observed today. The resulting ratio

naturally bridges the QCD-scale vacuum

and the current cosmological value

without requiring delicate cancellations among large ultraviolet contributions. In this sense the QEV model renders the observed vacuum energy

technically natural: it emerges from an

microscopic amplitude modulated by a physically derived, time-integrated damping history rather than from an ad-hoc balance of divergent terms.

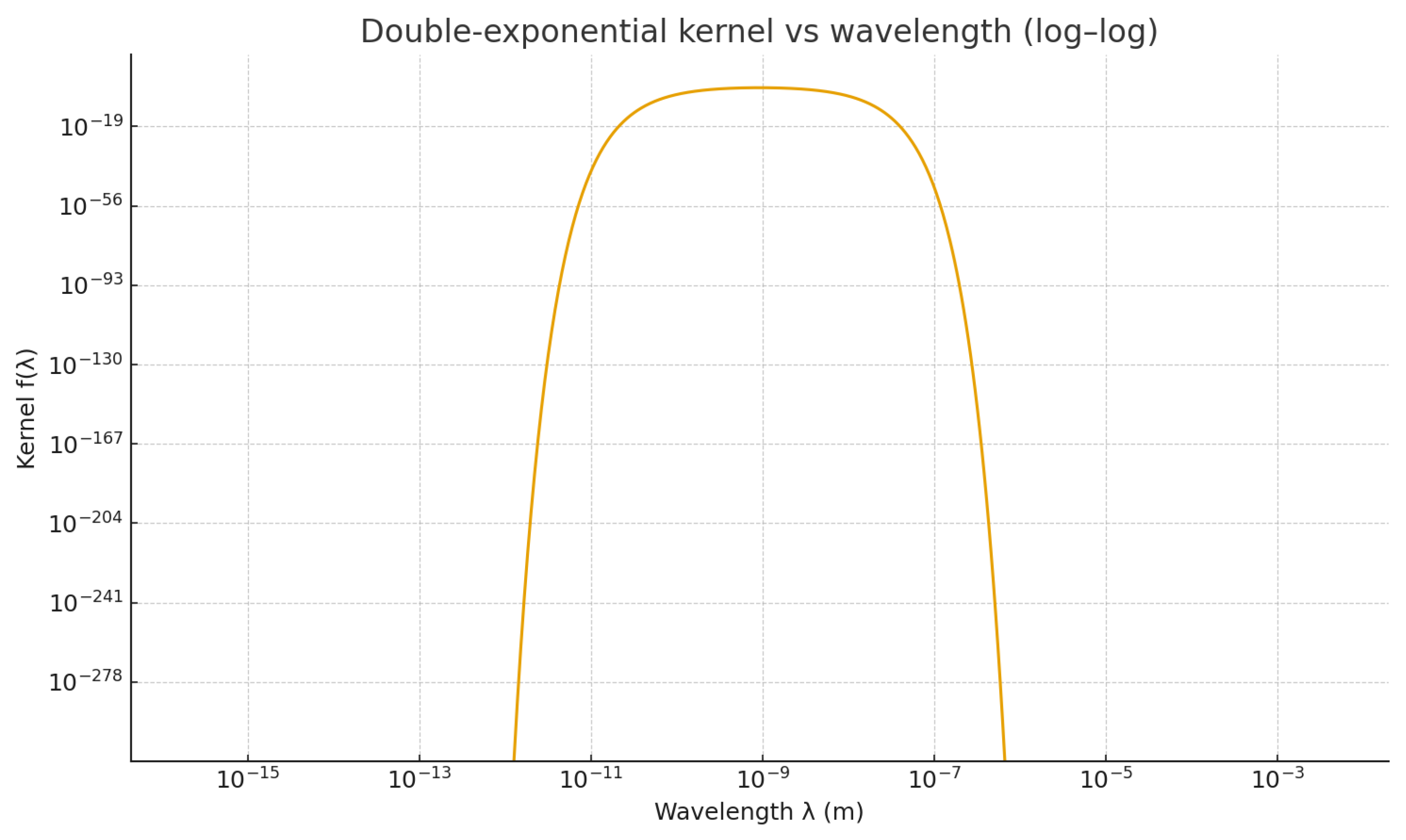

Figure A2.

Double-exponential kernel versus (log–log). Peak scale .

Figure A2.

Double-exponential kernel versus (log–log). Peak scale .

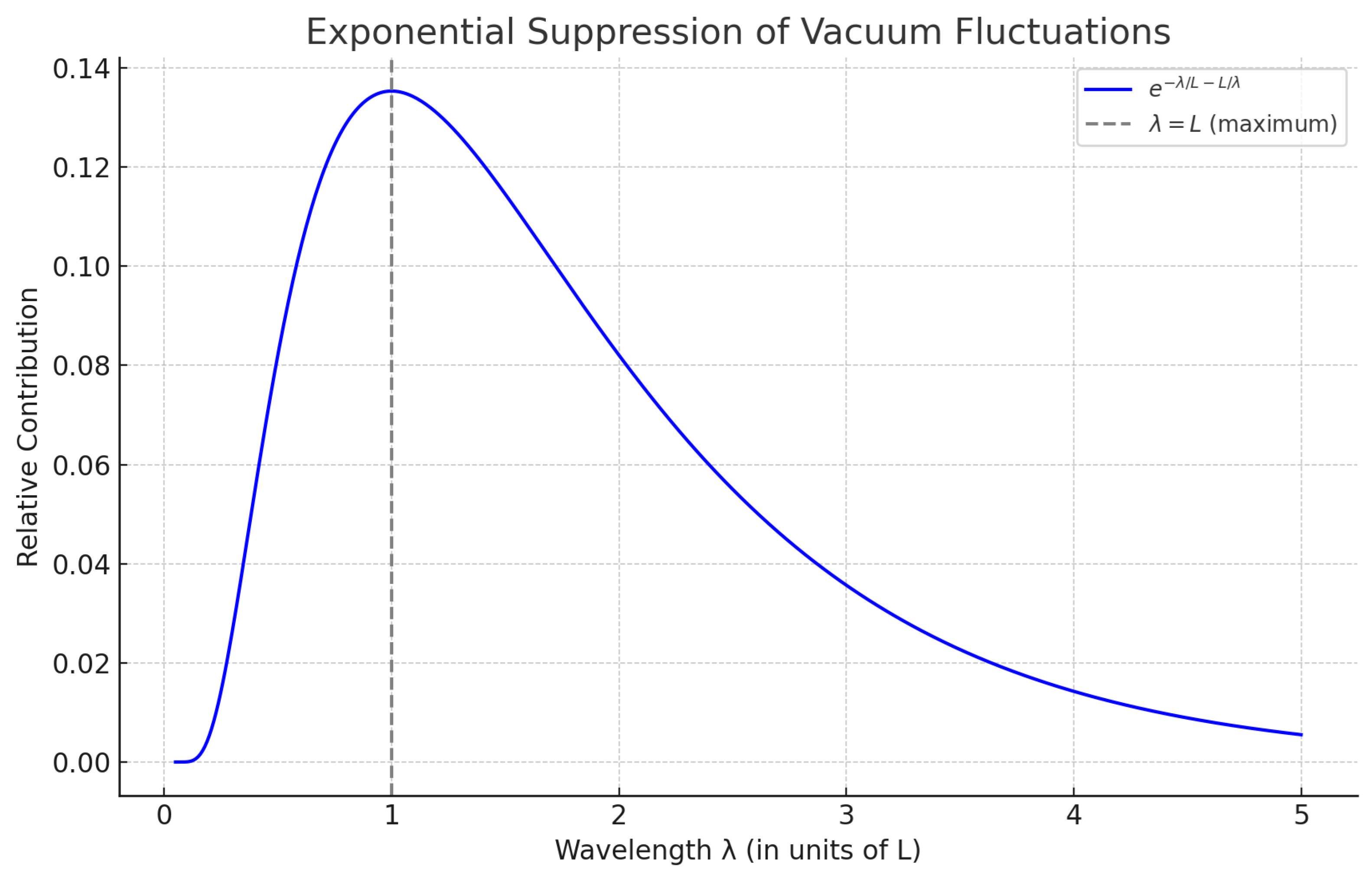

Figure A3.

Exponential suppression of vacuum fluctuations , with a maximum at . This explains why the geometric-mean scale dominates the bounded spectral integral.

Figure A3.

Exponential suppression of vacuum fluctuations , with a maximum at . This explains why the geometric-mean scale dominates the bounded spectral integral.

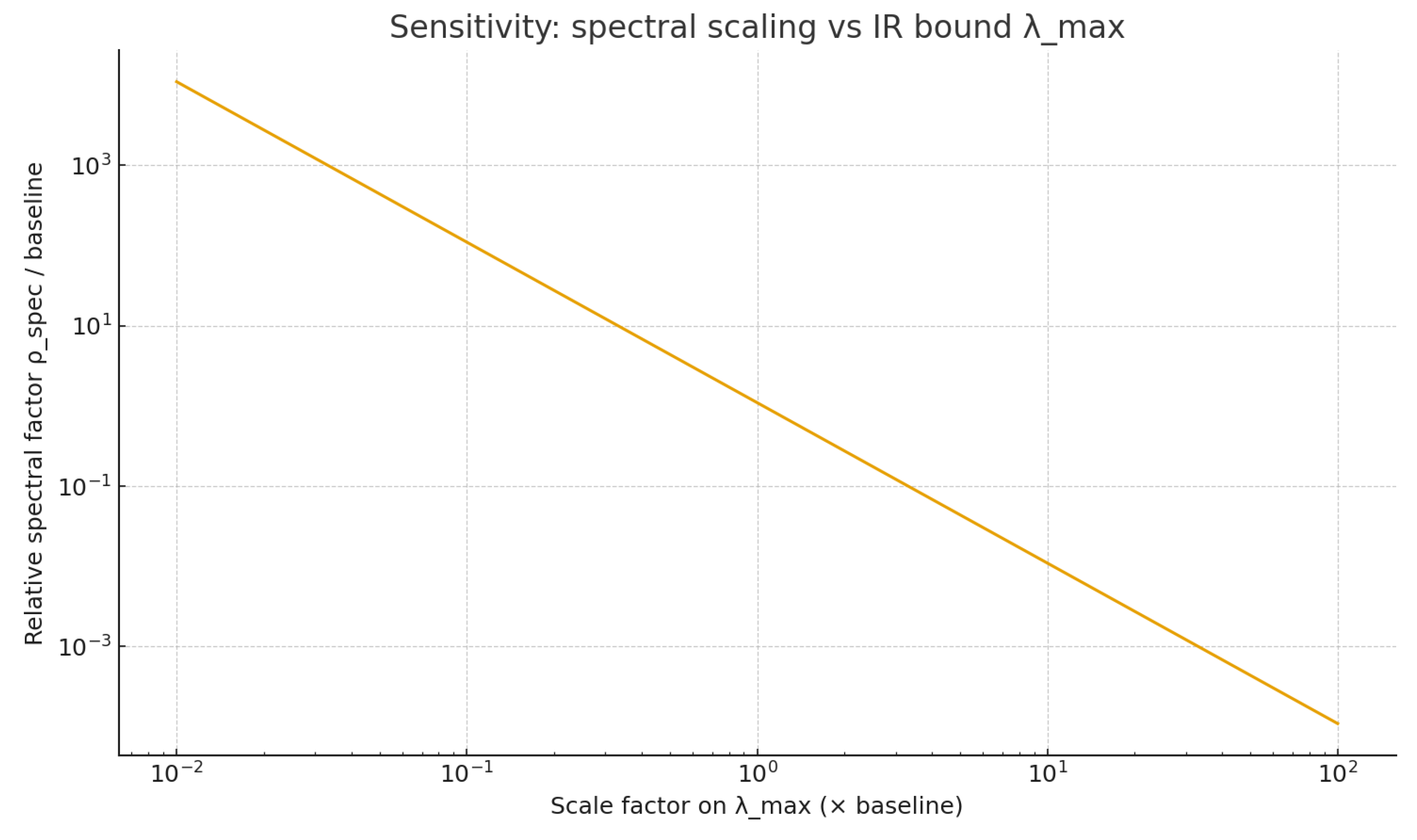

Relative spectral scaling versus the scaling factor.

Figure A4.

Relative spectral scaling versus the scaling factor. Trend: .

Figure A4.

Relative spectral scaling versus the scaling factor. Trend: .

For completeness, we note that for the symmetric kernel used here, the sensitivity with respect to the lower spectral bound behaves identically, yielding . Hence, within the interval , the resulting scaling remains effectively invariant, demonstrating the robustness of the spectral symmetry .

Figure A5.

Spectral function

computed from

with

and

. Vertical markers:

fm,

,

. Compare with

Figure A1 (where

).

Figure A5.

Spectral function

computed from

with

and

. Vertical markers:

fm,

,

. Compare with

Figure A1 (where

).

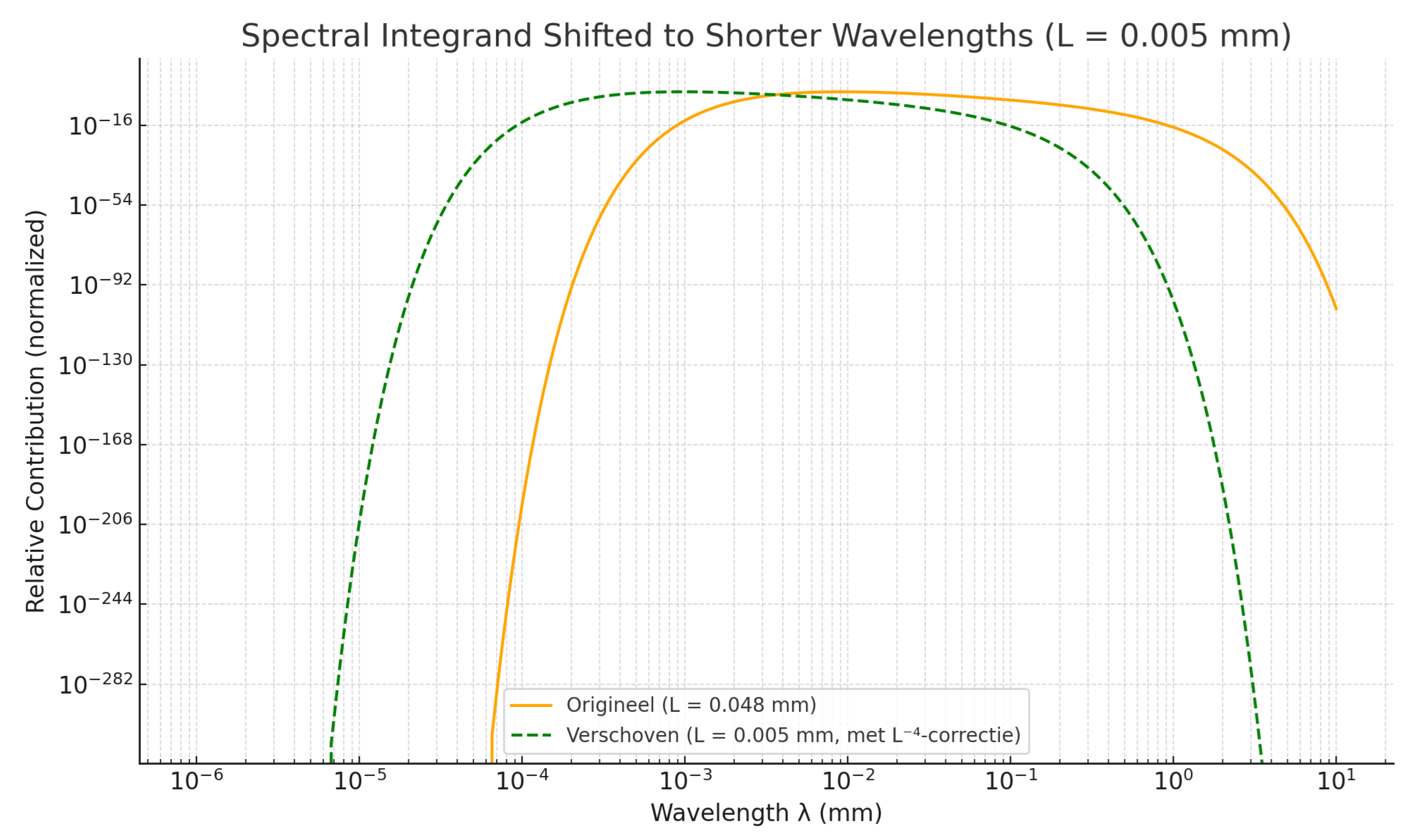

Figure A6.

Evolutionary shift of the effective spectral integrand towards shorter wavelengths as the IR scale tightens (cooling/expansion). The overall scaling follows the normalization.

Figure A6.

Evolutionary shift of the effective spectral integrand towards shorter wavelengths as the IR scale tightens (cooling/expansion). The overall scaling follows the normalization.

Appendix C.3. Dynamic Damping from QCD Scale to Today

The dynamic QEV model couples the bounded spectrum to a damping budget,

with

. Taking

and

fixes the required integrated damping

A representative, physically motivated split is

Here

, while

collects thermal/entropic suppression (depends on

) and

a Gaussian-like peak around

.

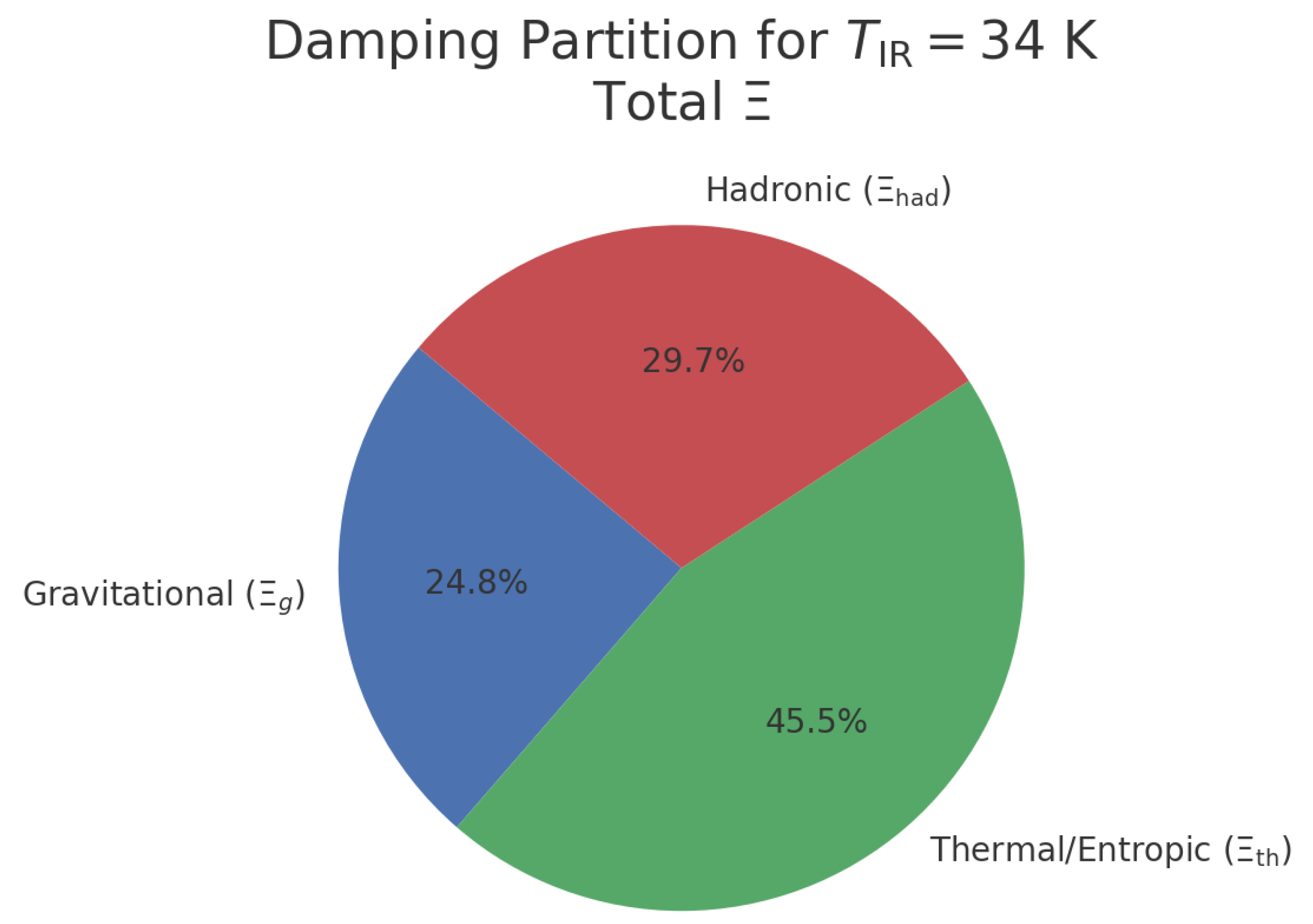

The damping partition is summarized in

Table 3 and visualized in

Figure A7; the IR-driven spectral shift is shown in

Figure A6, while the peak-at-

L mechanism is illustrated in

Figure A4.

Table A2.

Illustrative damping split to match .

Table A2.

Illustrative damping split to match .

| Component |

(e-folds) |

| Gravitational (Hubble) |

25 |

| Thermal/Entropic |

46 |

| Hadronic |

30 |

| Total |

101 |

Figure A7.

Damping budget (pie): , , (total ).

Figure A7.

Damping budget (pie): , , (total ).

Appendix C.4. Numerical Plug-in and Result

Combine the spectral factor and damping at

:

With

and

C = 4.3918318548 one finds

Figure A6 explicitly shows how tightening the IR bound shifts the effective integrand to shorter wavelengths; the overall normalization follows the

scaling of Eq. (

A5)

Appendix C.5. Numerical Plug-in and Result (with Fiducial Scales)

Combine the spectral factor and the dynamic damping at

:

For the fiducial values

and

we have

so that Eq. (

A10) can be used in the purely numeric form

Calibrating to

gives

which reproduces

and, inserted back into Eq. (

A6), returns

by construction.

Sensitivity of ρ vac to the Damping Budget Ξ

Fix

by calibrating Eq. (

A10) at

so that

today. Then for any other

(keeping

fixed) the prediction is

Table A3.

Sensitivity of the predicted vacuum energy density to the total damping budget , holding the normalization fixed to its calibration.

Table A3.

Sensitivity of the predicted vacuum energy density to the total damping budget , holding the normalization fixed to its calibration.

|

|

[J m−3] |

| 80 |

1.318816e+09 |

7.865024e-01 |

| 90 |

1.784823e+05 |

1.063758e-04 |

| 95 |

1.317006e+03 |

7.847355e-07 |

| 100 |

9.948374e+00 |

5.924162e-09 |

| 101 |

1.000000e+00 |

5.960000e-10 |

| 102 |

1.004987e-01 |

5.929722e-11 |

| 105 |

6.737947e-03 |

4.011837e-12 |

| 110 |

6.737947e-05 |

4.011837e-14 |

Appendix C.6. Conclusion (Concise Summary)

We model the vacuum as a dynamic, spectrally bounded medium: a UV bound from QCD confinement () and a thermal/entropic IR bound at defining a peak scale L = .

-

With the double–exponential kernel, the late–time spectral contribution is:

with

With the dimensionally-correct form the calibrated normalization reads (e.g. .

Time–dependent damping encodes gravitational (Hubble), thermal/entropic, and hadronic effects. The required integrated damping to reach today is e–folds, e.g. a representative split , , .

The calibrated result matches the observed vacuum density: (Planck 2018), with late–time .

Sensitivities are mild and controlled: at fixed , ; order–unity changes in kernel shape shift by order–unity; .

Appendix D. Critical Temperature of the Quantum Vacuum

The superconductivity analogy in this appendix is a heuristic for how a bounded spectral response can emerge; it is not a claim of a literal critical temperature of the vacuum sector. Our late-time predictions do not rely on this analogy; all observables follow from the time-local window at and the effective spectral kernel.

Appendix D.1. Physical Interpretation

As a

heuristic analogy, one may view the spectral bounding as playing a role similar to a critical-scale phenomenon in superconductors, without implying a literal critical temperature of the vacuum. At this temperature the characteristic energy

corresponds to the condensation scale of macroscopic quantum coherence observed in many high-

superconductors. In these materials, thermal agitation above

destroys long-range phase coherence, while below

the collective wavefunction locks in phase. A similar argument can be applied to the vacuum itself: when the background temperature of the Universe drops below

, the thermal population of long-wavelength vacuum modes becomes exponentially suppressed, and the vacuum enters a coherent, spectrally frozen state.

Appendix D.2. Connection to the QEV Framework

Within the Quantum Entropic Vacuum (QEV) picture, the infrared cutoff defines the scale at which thermal entropy ceases to dominate the vacuum dynamics. Above the entropic term acts as a positive, expanding driver, while below this temperature the hadronic–gravitational component gradually takes over as a damping factor. The balance point corresponds to a critical temperature of the quantum vacuum, analogous to the phase transition in superconductivity.

Appendix D.3. Physical Consequences

Below

the thermal contribution to the spectral energy density,

becomes negligible compared to the residual hadronic component. The effective vacuum energy thus stabilizes to a constant value

, where

is frozen at its 34 K value. See

Figure A8. This marks the transition from a dynamic, entropically dominated vacuum to a static, coherent phase— a cosmological analogue of a superconducting condensate.

Across we find a stable late-time energy density, with , implying only smooth, percent-level shifts in the kinematic diagnostics used here.

Appendix D.4. Visual Representation of the Infrared Sensitivity

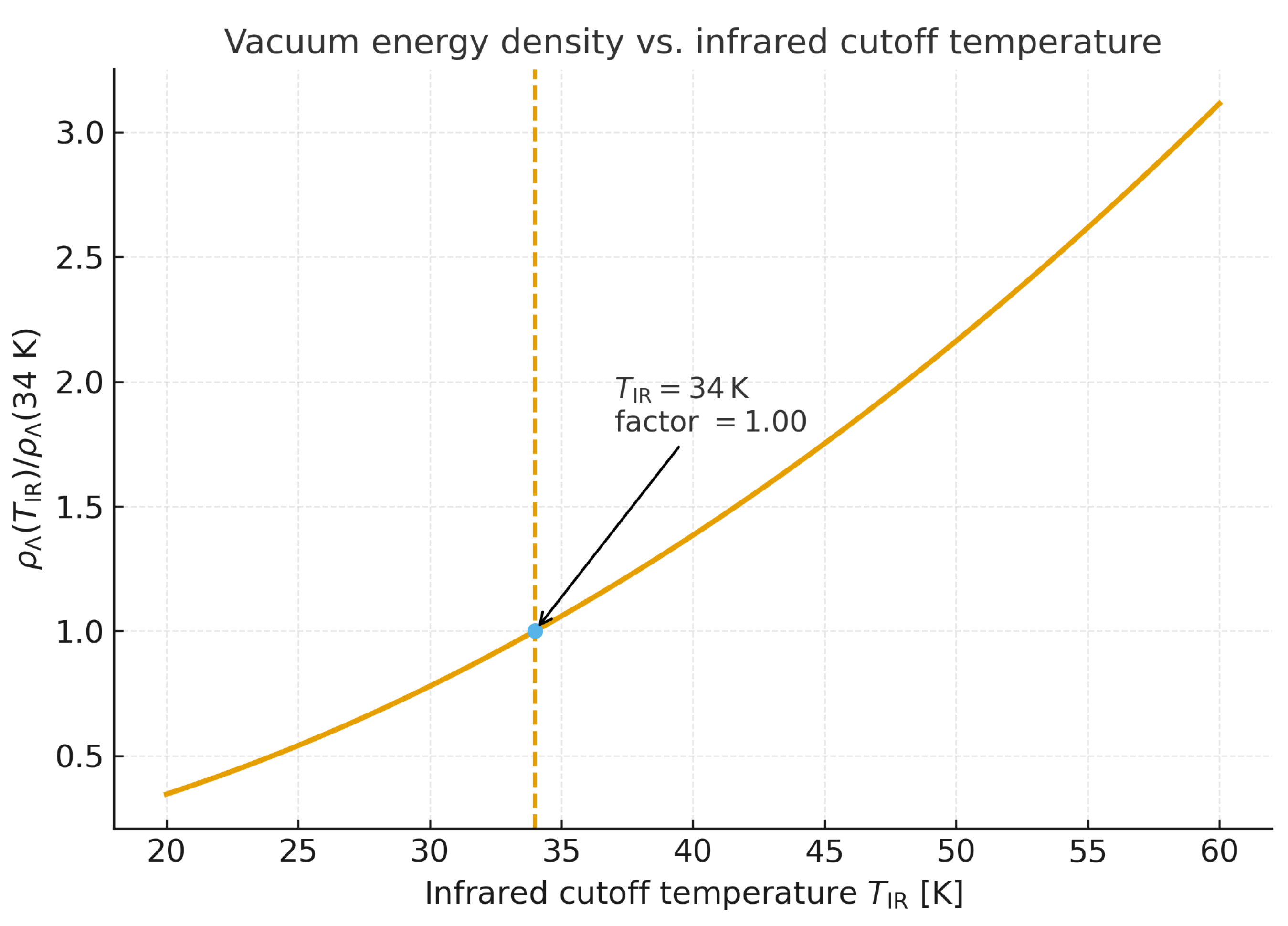

Figure A8.

Dependence of the normalized vacuum energy density on the infrared cutoff temperature in the range 20–. The dashed vertical line marks the adopted value , at which the ratio equals unity. Because , the variation remains modest: doubling increases only by a factor of . This illustrates the robustness of the chosen cutoff and the relative insensitivity of the vacuum energy to small shifts in the critical temperature.

Figure A8.

Dependence of the normalized vacuum energy density on the infrared cutoff temperature in the range 20–. The dashed vertical line marks the adopted value , at which the ratio equals unity. Because , the variation remains modest: doubling increases only by a factor of . This illustrates the robustness of the chosen cutoff and the relative insensitivity of the vacuum energy to small shifts in the critical temperature.

Appendix D.5. Broader Implications

The coincidence between the energy scale

and the condensation energy of many superconductors suggests that the same quantum statistics governing macroscopic coherence in condensed matter may also regulate the infrared structure of the vacuum. See

Figure A8. In this view, the cosmological constant emerges as the residual ground-state energy of a globally coherent vacuum field, whose critical temperature corresponds to

. This provides an appealing physical interpretation of why vacuum fluctuations “freeze out” at this scale and why the observed vacuum energy remains finite and stable.

Appendix E. Effective Fluid Formulation of the QEV Vacuum

The Quantum Entropic Vacuum (QEV) energy density can be cast as an effective cosmological fluid in the Friedmann–Robertson–Walker (FRW) background, allowing explicit verification of energy–momentum conservation and of the asymptotic equation-of-state .

Appendix E.1. Energy–Momentum Conservation

In a homogeneous and isotropic Universe the conservation law

reduces to the continuity equation

where

is the Hubble rate. The QEV energy density follows from the spectral-bounded ansatz

with

fixed by confinement physics and

tracing the evolving infrared limit.

Differentiating Equation (

A12) yields

Substitution into Equation (

A11) gives the effective pressure

Hence the instantaneous equation-of-state parameter is

When becomes constant—as expected after the thermal/entropic freeze-out—one obtains and , recovering the cosmological-constant limit.

Appendix E.2. Example Scaling of L(a)

If the infrared cutoff evolves with temperature as

while

remains fixed, then

and

corresponding to a transient radiation-like phase that is exponentially damped once the entropic factor

saturates. In the late-time regime of interest,

stabilises and

within deviations

.

Appendix E.3. Sound Speed and Stability

Perturbing Equation (

A11) at constant entropy gives the adiabatic sound speed

For monotonic

with slowly varying slope, the correction term is small and

. This implies a non-propagating (quasi-vacuum) mode with no ghost or gradient instability in the FRW background.

-

The adiabatic derivative of the effective-fluid relations yields . We emphasize that the QEV component is a quasi-vacuum sector with non-propagating rest-frame fluctuations; in practice we adopt a non-adiabatic (rest-frame) closure so that no rapid gradient instabilities arise in large-scale-structure regimes. Linear-growth observables are evaluated in the background limit with the baseline (propagation-only) choice, which is sufficient for the percent-level deviations reported here.

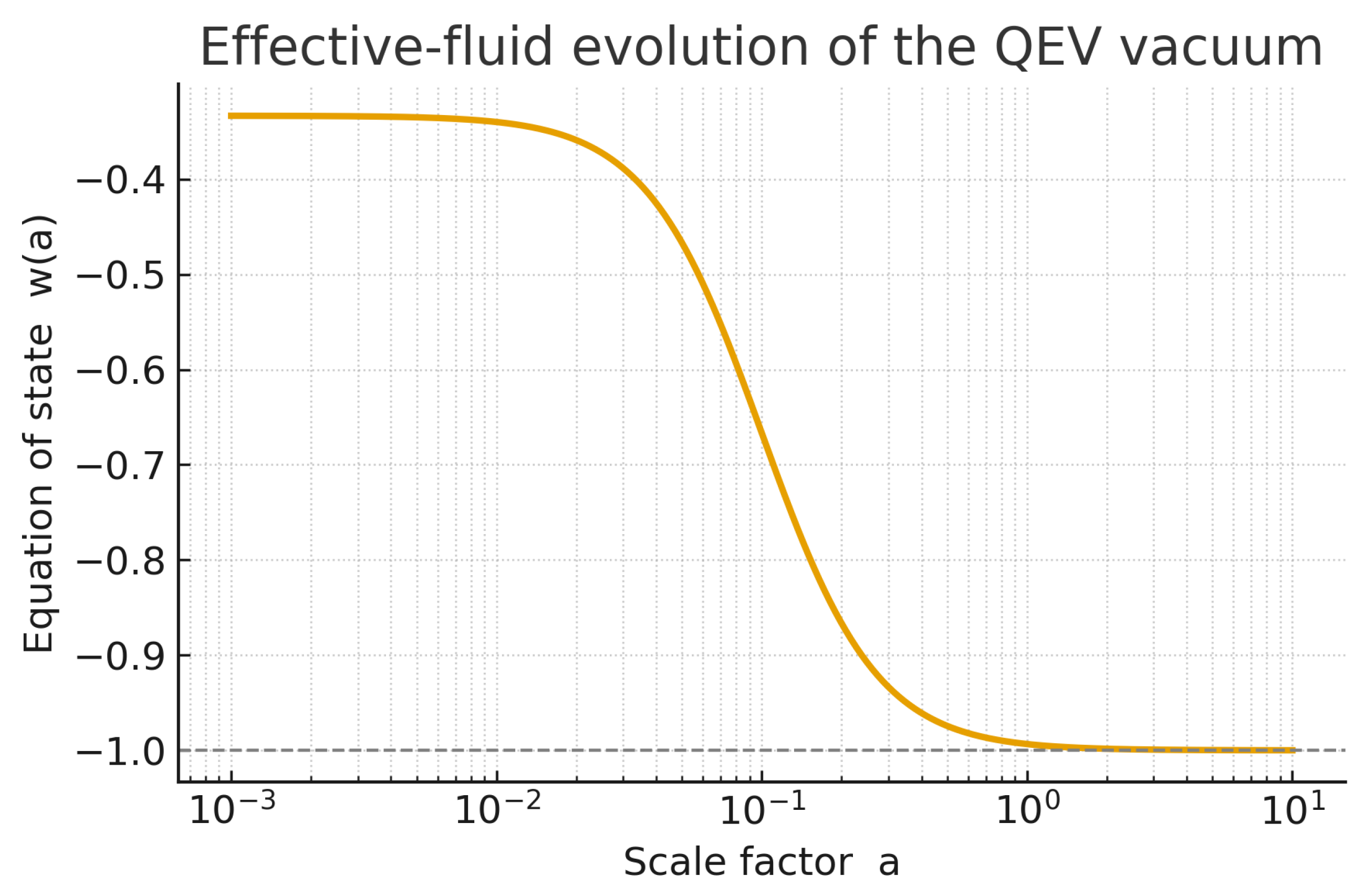

Figure A9.

Effective-fluid evolution of the QEV vacuum. The equation of state follows . The illustrative curve uses a smooth early-to-late transition with , yielding a radiation-like phase ( for ) that relaxes toward a cosmological-constant limit () once saturates (). At late times the deviation is small, for the example shown.

Figure A9.

Effective-fluid evolution of the QEV vacuum. The equation of state follows . The illustrative curve uses a smooth early-to-late transition with , yielding a radiation-like phase ( for ) that relaxes toward a cosmological-constant limit () once saturates (). At late times the deviation is small, for the example shown.

Appendix E.4. Summary

The effective-fluid form Eqs. (

A13)–(

A14) guarantees

by construction. The model evolves smoothly from a damped, radiation-like early stage (

to

) toward a late-time cosmological-constant state (

), maintaining stability and internal energy conservation. This demonstrates that the QEV vacuum is formally covariant and self-consistent at the effective-fluid level.

Appendix F. Thermal Route: Baseline Choice and Variants

To avoid double counting of thermal/entropic physics, we define the

baseline QEV model by encoding all thermal effects exclusively in the

infrared propagation cutoff and setting explicit thermal source damping to zero:

with

the cosmological radiation temperature including the usual entropy–dilution factor,

.

1

Notation:

. The QEV energy density remains

Equations of state and conservation follow from the effective-fluid relations [Eqs. (

A13)–(

A14)]:

At late times

freezes (or varies only logarithmically), so

and

L approach constants and

.

All thermal dependence is carried by propagation (the spectral window). No additional exponential suppression is applied to the

source side:

This makes the mapping from temperature to observables one-to-one and prevents thermal physics from being counted twice (both in

and in an extra damping factor).

Use . Across known transitions (QCD, annihilation), update piecewise-constantly.

Keep fixed (QCD floor). Then and .

Late-time fits (SNe+BAO+CC): treat as parameters, with the freeze-out scale where saturates.

For comparison studies one may switch off thermal propagation evolution and encode thermal effects purely as source damping:

with a

single calibrated history

(e.g. smooth step across known thermal epochs). In this variant, do not allow

T-dependence in

. Then

and

by construction; thermal impact enters only via the normalization

.

Choose

either Equation (

A15) (propagation-only)

or Equation (

A18) (source-only) for any given analysis; never both. Formally:

These priors reflect percent-level kinematic robustness and keep the baseline identifiable.

Clearly state the chosen route in captions/tables: “Baseline (propagation-only)” or “Variant (source-only)”. Quote at and the mm-band target observable (e.g. cavity phase or Casimir window) using the same choice.

Appendix G. Response to Scope Critique (Early-Universe Comparison)

Our model is a late-time effective description: we evaluate the spectral, gravitationally relevant contribution at the present epoch . We make no claim about the absolute zero-point energy of the early Universe or about inflation. Historical processes are summarised by a convergent damping factor that we do not attempt to reconstruct at high temperatures. All equations and predictions are restricted to low redshift (), where direct falsification is possible through background and growth measurements, and through tabletop tests in the millimetre band.

References

- Abell, P.A. et al.LSST Science Book, Version 2.0. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0912.0201. [Google Scholar]

- Ade, P. et al. The Simons Observatory: Science goals and forecasts. JCAP 2019, 02, 056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, P. et al., The Simons Observatory: Science Goals and Forecasts for the Large Aperture Telescope. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.00636. [Google Scholar]

- Birrell, N.D.; Davies, P.C.W. Quantum Fields in Curved Space; Cambridge University Press: 1982.

- Euclid Collaboration (A. Blanchard et al.), Euclid preparation: VII. Forecast validation for Euclid cosmological probes. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.09273.

- Callen, H.B. Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics; Wiley: 1985.

- Colladay, D.; Kostelecký, V.A. Lorentz-violating extension of the standard model Phys. Rev. D 1998, 58, 116002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euclid Collaboration (J.-C. Cuillandre et al.), Euclid: Early Release Observations (ERO): Perseus Cluster. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.13501.

- Dhital, M.; Mohideen, U. , A Brief Review of Some Recent Precision Casimir Force Measurements. Physics 2024, 6, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaka, B.; Sedmik, R.I.P. et al. Casimir Effect in MEMS: Materials, Geometries, and Metrologies—A Review. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidel, L.; Hopfmueller, F.; Livine, E.R. Gravitational Energy, Local Holography and Entanglement in Gravity, Class. Quantum Grav. 2023, 40, 085005. [Google Scholar]

- Freidel, L.; Kowalski-Glikman, J.; Leigh, R.G.; Minic, D. Vacuum Energy Density and Gravitational Entropy. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 107, 126016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamminga, A.J.H. Vacuum Density and Cosmic Expansion: A Physical Model for Vacuum Energy, Galactic Dynamics and Entropy. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamminga, A.J.H. Photonic Vacuum Windows: A Casimir-Safe Operational Baseline. 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta, J.I.; Gale, C. , Finite-Temperature Field Theory: Principles and Applications; Cambridge University Press: 2006.

- Klinkhamer, F.R.; Risse, M. Vacuum energy density from a spectral cutoff. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.11202. [Google Scholar]

- Klinkhamer, F.R.; Schreck, M. Improved bound on isotropic Lorentz violation in the photon sector. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 116011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. Everything you always wanted to know about the cosmological constant problem (but were afraid to ask). C. R. Physique 2012, 13, 566–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussenzveig, H.M. , Causality and Dispersion Relations; Academic Press: 1972.

- Olver, F.W.J.; Lozier, D.W.; Boisvert, R.F.; Clark, C.W. (eds.) NIST Digital Library of Mathematical Functions, Chap. 10: Bessel and Modified Bessel Functions (2025). https://dlmf.nist.gov/10.

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The cosmological constant problem. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989, 61, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, K.; Hatsuda, T.; Miake, Y. Quark-Gluon Plasma: From Big Bang to Little Bang; Cambridge University Press: 2005.

- Schee, W.v. Gravitational collisions and the quark-gluon plasma. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University (2014). arXiv:1407.1849.

- DESI Collaboration (A. G. Adame et al.) DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from the First Two Years. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.03002.

- DESI Collaboration (A. G. Adame et al.) DESI 2024 V: Full-Shape Galaxy Clustering from the First Year of DESI. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2411.12021.

| 1 |

We use for entropy degrees of freedom and for energy degrees of freedom. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).