1. Introduction

Vacuum energy is a central concept in quantum field theory and cosmology, yet it leads to one of the most perplexing inconsistencies in physics: the cosmological constant problem. While quantum theory predicts an enormous vacuum energy density, observations point to a vastly smaller value—over 120 orders of magnitude less. This discrepancy has prompted the development of various alternative models to redefine, suppress, or re-interpret vacuum energy.

One promising approach is the QEV model, which reframes vacuum energy as a bounded spectral integral. Rather than applying arbitrary cutoffs, the QEV model introduces physically motivated limits based on known phase transitions in the vacuum:

1.

The upper bound is defined by quantum chromodynamics (QCD) confinement at high energies [

7], where quarks and gluons become confined within hadrons, and

2.

The lower bound emerges from thermal suppression below

, where quantum vacuum fluctuations become effectively frozen [

4].

Together, they define a natural spectral window for vacuum fluctuations.

The model employs a double exponential damping function to integrate energy density contributions, aligning with statistical thermodynamics and yielding a convergent result without fine-tuning. Beyond its spectral formulation, the QEV model provides explanatory power for large-scale cosmic phenomena. It reproduces galactic rotation curves without invoking dark matter and matches the observed late-time cosmic acceleration without requiring an arbitrary cosmological constant. Furthermore, the model interprets the QCD phase boundary as an informational horizon, beyond which the vacuum becomes electromagnetically opaque—analogous to a black hole horizon. This unifies energetic, entropic, and epistemic limits within a single consistent vacuum structure.

The following report outlines the theoretical basis of the QEV model, compares it to alternative approaches, and discusses its implications for both fundamental physics and observational cosmology.

2. Spectral Framework of the QEV Model

The QEV model constructs vacuum energy as a bounded spectral integral over fluctuating modes, weighted by a double exponential damping function. This approach avoids arbitrary cutoffs and derives convergence from physical principles rooted in phase transitions of the vacuum.

2.1. Spectral Integral Formulation

The vacuum energy density is expressed as a spectral integral:

where

is a damping function and

denotes the spectral energy density per mode. The bounds of integration are physically motivated:

1. The

upper bound corresponds to the

QCD confinement scale, beyond which quarks and gluons become confined within hadrons [

7].

2. The

lower bound reflects

thermal suppression below approximately 30 K, where quantum vacuum fluctuations effectively freeze [

4].

The damping kernel takes the form:

which ensures rapid suppression outside the physical spectral window. This structure is thermodynamically consistent with the Boltzmann distribution

, and guarantees convergence without the need for artificial fine-tuning.

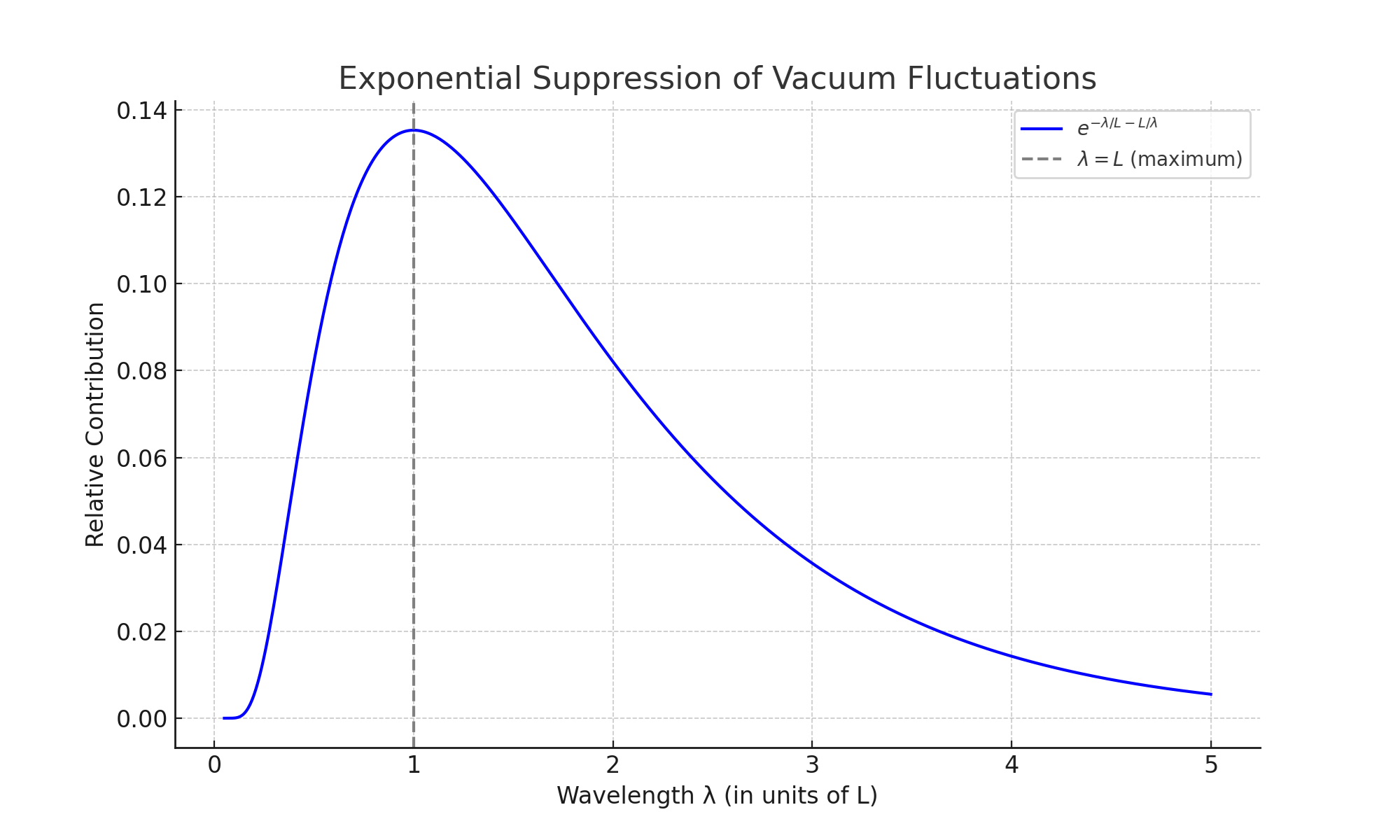

An explicit example of this approach is illustrated in

Figure 1, discussed in the next section.

3. Spectral Formulation of Vacuum Energy

In the following, we adopt a specific form of as a single spectral function, inspired by thermodynamic considerations and statistical physics. This formulation merges the damping function and the spectral density into one expression.

To model vacuum energy, we use a spectral density function: [

1,

4]

This form ensures convergence without the need for artificial cutoffs.

The resulting integrand of the spectral vacuum energy density exhibits a clear maximum between the two physically motivated cutoffs, forming a natural energy window for vacuum fluctuations. See

Figure 1

Figure 1.

Exponential suppression function showing peak at and rapid decay on both sides.

Figure 1.

Exponential suppression function showing peak at and rapid decay on both sides.

4. Numerical Result and Interpretation

Choosing:

J·m4

This value is consistent with cosmological observations (e.g., Planck 2018 data) [

5], providing a strong consistency check.

Interpretation of A

The factor

A encodes the effective number of quantum fields contributing within the spectral window. This is analogous to the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, which encapsulates the number of degrees of freedom contributing to blackbody radiation. [

4], it reflects the cumulative effect of all active modes:

5. Comparison with Other Approaches

Many conventional approaches to the vacuum energy problem introduce an upper cutoff at the Planck scale, which leads to an energy density exceeding observational values by up to 120 orders of magnitude. Attempts to resolve this discrepancy often invoke speculative physics, such as dynamical fields (e.g., quintessence), vacuum energy sequestering, or anthropic reasoning.

Other directions include holographic models that constrain vacuum energy via boundary conditions or entropy-area relationships. While these are conceptually interesting, they often lack empirical grounding or require assumptions beyond the Standard Model.

In contrast, the spectral approach presented here is based solely on established transitions in the known physical vacuum: quantum chromo-dynamic confinement at short wavelengths, and thermal suppression of long-wavelength modes. These bounds emerge naturally from existing theory and observation, avoiding arbitrary cutoffs or the need for new physics. The resulting vacuum energy density aligns closely with current cosmological measurements, without fine-tuning.

6. Conclusion

This QEV model yields a finite and observationally consistent vacuum energy density without the need for fine-tuning or speculative new physics. It relies solely on established physical transitions and thermodynamic principles. The spectral formulation provides a clear, testable alternative to conventional approaches and may serve as a foundation for further theoretical development.

7. Speculative Implications and Future Outlook

The following remarks present a speculative hypothesis. While the QEV model is grounded in established physics, it invites several speculative considerations:

Entropy and cosmic expansion: From

follows

, suggesting an entropic link to cosmic acceleration [

4].

Frozen degrees of freedom: The suppression of long wavelengths at low T could correspond to a freezing out of vacuum modes.

Vacuum and black holes: The QCD confinement scale may signal the onset of vacuum structure.

This resonates with holographic models in which quark-gluon plasma behavior is described by the formation of black holes in higher-dimensional spacetimes [

7].

Inside black holes, such confinement may help explain the absence of light propagation (speculative).

7.1. Positioning within Fundamental Physics

The QEV model (Quantum Energy Vacuum) presented here offers a physically grounded and testable approach to vacuum energy, deviating from conventional models that rely on fine-tuning or hypothetical entities. Unlike many standard approaches that impose a cutoff at the Planck scale or that invoke string theory and higher-dimensional spacetimes, this model strictly uses physically justified boundaries: the QCD confinement scale as the short-wavelength limit, and thermal suppression below approximately 30 K as the long-wavelength limit.

This spectral limitation leads to a natural, convergent vacuum energy density that is consistent with observations. Moreover, the model accounts for both the accelerated cosmic expansion and galactic rotation curves without invoking dark matter or a cosmological constant. In this sense, the QEV model aligns with a growing class of theories in which gravity, space, and time are viewed as emergent phenomena rooted in thermodynamic and information-theoretic principles.

Within this spectrum of approaches, various theoretical pathways exist. Energetic-thermodynamic models, such as those by Callen and Padmanabhan, emphasize entropic forces and thermodynamic balance, while the holographic approach (Bekenstein, Susskind) focuses on information storage at spatial boundaries. The QEV model positions itself between these paradigms, emphasizing spectral suppression of fluctuations within a physically defined window.

In the context of unification, it is notable that the model does not rely on hypothetical extra dimensions (as in string theory) or speculative particle fields. The recent emergent gravity framework proposed by Verlinde provides a related direction, viewing gravity as an emergent effect of information flows or thermodynamic gradients.

In this context, the QEV model presents a concrete and conceptually consistent alternative in the search for a unification of quantum field theory and gravity—without fine-tuning and without requiring extensions to the Standard Model or the introduction of extra dimensions.

Future Outlook: Further research may focus on applications of the QEV model to inflation, cosmic structure formation, or black hole thermodynamics. This could contribute to a deeper integration of vacuum physics and gravity, forming a potential step toward a coherent theory of reality.

Appendix

Appendix A: Smooth Suppression versus Sharp Cutoffs

In traditional quantum field theory, divergences are avoided by introducing sharp cutoffs [

1]. In contrast, the specific formulation presented in

Section 3 employs a smooth suppression function:

This function provides a dual exponential suppression and serves as an illustrative realization of the general framework introduced earlier.

This ensures convergence of the spectral integral without introducing abrupt or artificial limits.

Appendix B: Phase Transitions as Spectral Limits

Two physical phase transitions define the boundaries of the vacuum fluctuation spectrum:

QCD confinement: At energies above

(or

), free quarks do not exist as stable vacuum modes [

3].

Thermal suppression: Below

, long-wavelength modes become thermally inactive [

2]. This sets

.

These bounds naturally define the physically meaningful vacuum spectrum.

Appendix C: Dimensional Scaling of the Suppression Function

1. Purpose

This appendix offers an alternative perspective on spectral suppression by expressing the wavelength in physical units (millimeters) instead of dimensionless quantities. This allows for a more intuitive connection between the spectrum and experimentally relevant scales.

2. Suppression Function

We start from the following spectral suppression:

where

L is the characteristic scale of the vacuum spectrum.

3. Normalization and Energy Density

To maintain a fixed total vacuum energy, we normalize the spectral function:

where the normalization constant

is chosen such that:

with

, the observed vacuum energy density in adjusted units.

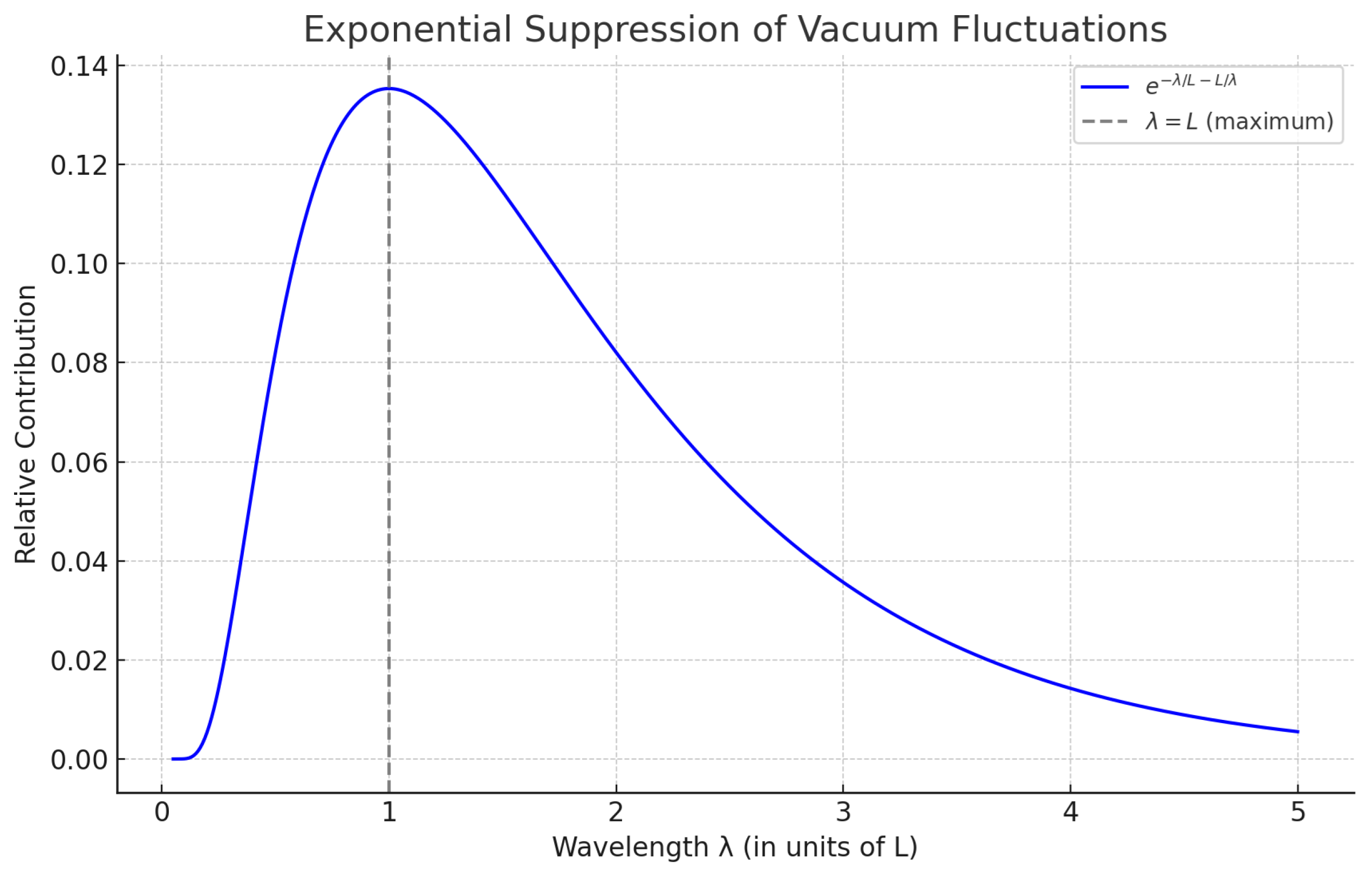

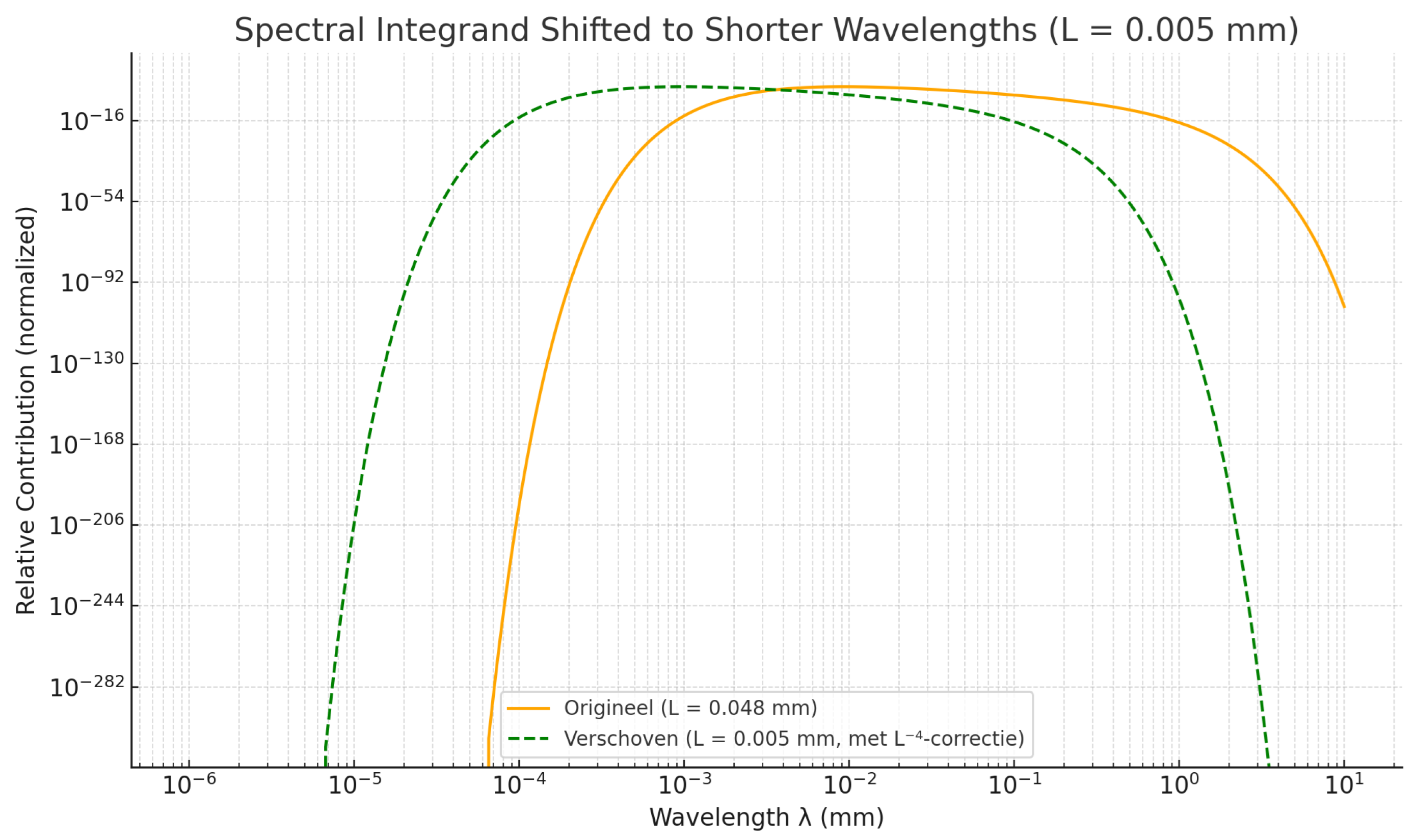

4. Example: L=0.048mm

For (characteristic of the thermal boundary), the function peaks at . The integration bounds are set from to , corresponding to the expected physical window.

Figure 2.

Spectral suppression function with , scaled to match the observed vacuum energy density. X-axis in mm, Y-axis in mm-4.

Figure 2.

Spectral suppression function with , scaled to match the observed vacuum energy density. X-axis in mm, Y-axis in mm-4.

This figure complements the earlier dimensionless representation by anchoring the spectrum to physically interpretable units while preserving the total integrated energy.

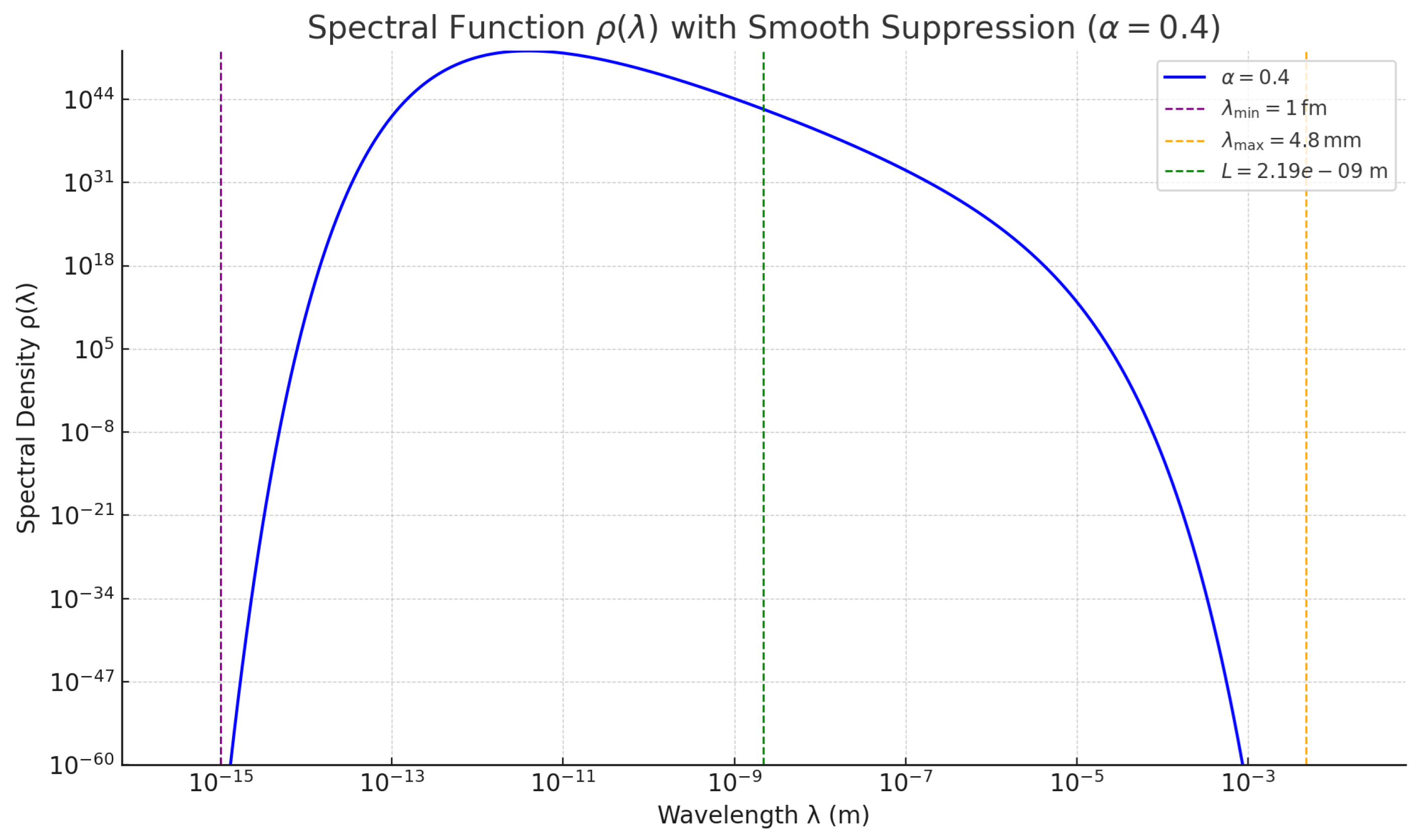

Appendix D: Modified Spectral Suppression with α=0.4

1. Purpose

This appendix investigates an alternative form of spectral suppression with a softer exponential damping, modeled as:

where the parameter

is chosen instead of the standard value

from the main model. This adjustment leads to a broader spectral distribution and a lower peak, without altering the physical framework.

2. Physical Motivation

Choosing softens the suppression of both short and long wavelengths. As a result, more wavelengths within the physical window contribute significantly to the vacuum energy density. The model remains symmetric around the characteristic scale and requires no fine-tuning.

3. Numerical Result

For

, the unnormalized vacuum energy density becomes:

To match the observed value, the scaling factor

A is adjusted to:

While alternative choices such as yield comparable numerical results, the main model adopts for physical consistency. This choice corresponds to a linear suppression exponent in the Boltzmann factor, which reflects a thermodynamically natural damping related to entropy and temperature.

4. Summary Table Parameters

Table 1.

Physical parameters of the modified model with

Table 1.

Physical parameters of the modified model with

| Quantity |

Symbol |

Value |

Meaning |

| Lower wavelength limit |

|

m |

QCD confinement |

| Upper wavelength limit |

|

m |

Thermal boundary at 30 K |

| Characteristic scale |

L |

m |

Geometric mean |

| Suppression exponent |

|

|

Softened damping on both sides |

| Normalization factor |

A |

J·m4

|

Effective degrees of freedom in the spectrum |

| Resulting density |

|

J/m3

|

Matches observations |

5. Visualization

The following graph shows the spectral function for . The suppression transitions more gradually, with a broader contribution from the spectrum. The physically relevant limits ( and ) are marked with vertical lines.

Figure 3.

Spectral suppression function with , scaled to match the observed vacuum energy density. X-axis in mm, Y-axis in mm-4.

Figure 3.

Spectral suppression function with , scaled to match the observed vacuum energy density. X-axis in mm, Y-axis in mm-4.

Appendix E: Entropy and Thermal Suppression

Although the total entropy of the universe increases over time, the thermal population of vacuum modes decreases with cooling. Thus:

The term reflects the suppression of long-wavelength modes at low temperature.

Appendix F: Entropic Interpretation of Suppression

From statistical mechanics:

This exponential suppression aligns with the physical interpretation of the spectral integral’s damping factor [

4]. The integrand’s maximum at

represents the region of maximum entropic contribution.

Unified implications

The QEV model presented here provides a consistent spectral explanation for the observed vacuum energy density while simultaneously reproducing galactic rotation curves and the late-time acceleration of the universe. This unification of dark matter and dark energy effects through vacuum structure distinguishes the model from other recent approaches.

For instance, Freidel et al. [

8] propose an alternative explanation for the smallness of vacuum energy based on an entropic balance between microscopic vacuum state degeneracy and macroscopic gravitational entropy. Their model arrives at a comparable vacuum energy density without fine-tuning, grounded in quantum gravitational considerations. However, it does not extend to the galactic or cosmological dynamics discussed here. In contrast, the present model links spectral vacuum limits directly to both quantum field transitions and observable gravitational phenomena, offering a phenomenologically grounded alternative. This interpretation resonates with the modular spacetime perspective introduced by Freidel, Leigh, and Minic, in which the vacuum is viewed as an informational structure bounded by natural IR and UV scales.

On the Scope of the Vacuum Energy Problem

The scope and depth of the vacuum energy problem is illustrated not only by its presence in high-level theoretical physics, such as in the seminal work by Birrell and Davies on quantum fields in curved spacetime [

1], but also in educational and conceptual explorations that highlight the conceptual richness of the vacuum energy problem.

Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations

-

QEV

Quantum Energy Vacuum model – The proposed model in this paper using bounded spectral integration to explain vacuum energy.

-

QCD

Quantum Chromodynamics – The theory describing the strong nuclear force between quarks and gluons.

-

QGP

Quark-Gluon Plasma – A high-energy state of matter in which quarks and gluons are deconfined.

-

CDM

Lambda Cold Dark Matter – The standard cosmological model with a cosmological constant () and cold dark matter.

-

IR/UV

Infrared/Ultraviolet – Infrared and Ultraviolet: refer to the long- and short-wavelength regimes, respectively

Vacuum Energy Density – The energy density attributed to quantum fluctuations in the vacuum.

-

L

Characteristic Scale – The central wavelength used in the spectral suppression function.

Suppression Exponent – Controls the steepness of the spectral damping function.

Effective Degrees of Freedom – The weighted number of field modes contributing within the spectral window.

Report: Comparison of Alternative Models for Vacuum Energy

This report provides a comparative analysis of several theoretical models proposed as alternatives to the standard treatment of vacuum energy in cosmology. The cosmological constant problem namely, the discrepancy of up to 120 orders of magnitude too large between quantum field theory predictions and the observed vacuum energy density, remains one of the most significant unsolved issues in fundamental physics.

Among the models examined is the spectral suppression model developed by this QEV model, which introduces a novel approach based on physically grounded limits and thermodynamic considerations. Unlike models that invoke exotic fields or speculative mechanisms, framework of this model defines vacuum energy through a spectrally weighted integration bounded by two physically motivated cutoffs:

an upper limit determined by QCD confinement, and

a lower limit set by thermal suppression below approximately 30 K.

The spectral function employs a double exponential damping term that ensures convergence without the need for fine-tuning or artificial cutoffs.

See

Table 2 for a comparative overview.

Conclusion

The comparison reveals that the model in this paper distinguishes itself through its combination of:

natural, physically motivated boundaries (hadronic confinement and thermodynamic saturation),

an elegant and convergent spectral formulation,

and an explicit avoidance of fine-tuning.

Crucially, the model produces a numerical result for the vacuum energy density that is consistent, in order of magnitude, with observational data from the cosmic expansion. This renders it a promising and testable candidate, not only as an explanation for the cosmological constant, but also as a more general description of the vacuum’s energy structure, potentially bridging the gap between quantum field theory and cosmology.

Comparison Table: Alternative Models for Vacuum Energy

Table 2.

Comparison of alternative theoretical approaches to the vacuum energy problem.

Table 2.

Comparison of alternative theoretical approaches to the vacuum energy problem.

| Model |

Mechanism / Principle |

Fine-tuning Required? |

Physically Motivated Cutoffs |

Predictive Power |

Vacuum Energy Estimate |

| ACDM (Standard Model) |

Constant vacuum energy (cosmological constant A) |

Yes (120 orders too large) |

No |

High (fits expansion) |

Vastly too large (QFT value) |

| Quintessence |

Dynamic scalar field with evolving energy density |

Yes (potential function) |

No |

Medium to high |

Tuned to fit observations |

| Holographic Dark Energy |

Entropy bound from holographic principle |

Partial |

Yes (IR/UV scale relation) |

Medium |

Adjustable to observed

|

| Zero-point Energy Cutoff |

Simple upper frequency cutoff in vacuum modes |

Yes (arbitrary cutoff) |

No (cutoff is artificial) |

Low |

Can match , but unjustified |

| Modified Gravity (e.g., ) |

Gravity equations altered to absorb vacuum terms |

Indirect tuning |

No |

Medium to high |

Implicit; model-dependent |

| QEV model |

Bounded spectral integration with thermodynamic suppression |

No |

Yes (QCD + thermal ∼30 K) |

High (testable + derived ) |

Within observed range |

References

- N. D. Birrell and P. C. W. Davies, Quantum Fields in Curved Space, Cambridge University Press (1982).

- J. I. Kapusta and C. Gale, Finite-Temperature Field Theory: Principles and Applications, Cambridge University Press (2006).

- K. Yagi, T. Hatsuda and Y. Miake, Quark-Gluon Plasma: From Big Bang to Little Bang, Cambridge University Press (2005).

- H. B. Callen, Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics, Wiley (1985).

- Planck Collaboration, Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters, A&A 641, A6 (2020).

- F. R. Klinkhamer and M. Risse, Vacuum energy density from a spectral cutoff, arXiv:2102.11202 [gr-qc] (2021).

- W. van der Schee, Gravitational collisions and the quark-gluon plasma, PhD thesis, Utrecht University (2014), arXiv:1407.1849.

- L. Freidel, J. Kowalski-Glikman, R. G. Leigh, and D. Minic, Vacuum Energy Density and Gravitational Entropy, Phys. Rev. D 107, 126016 (2023), arXiv:2212.00901.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).