Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Setup: Soil Preparation and Sowing

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Climatological Data

2.4. Evaluation of the Weed Community

2.5. Harvest

2.6. Evaluated Parameters

2.7. Data Treatment

3. Results and Discussion

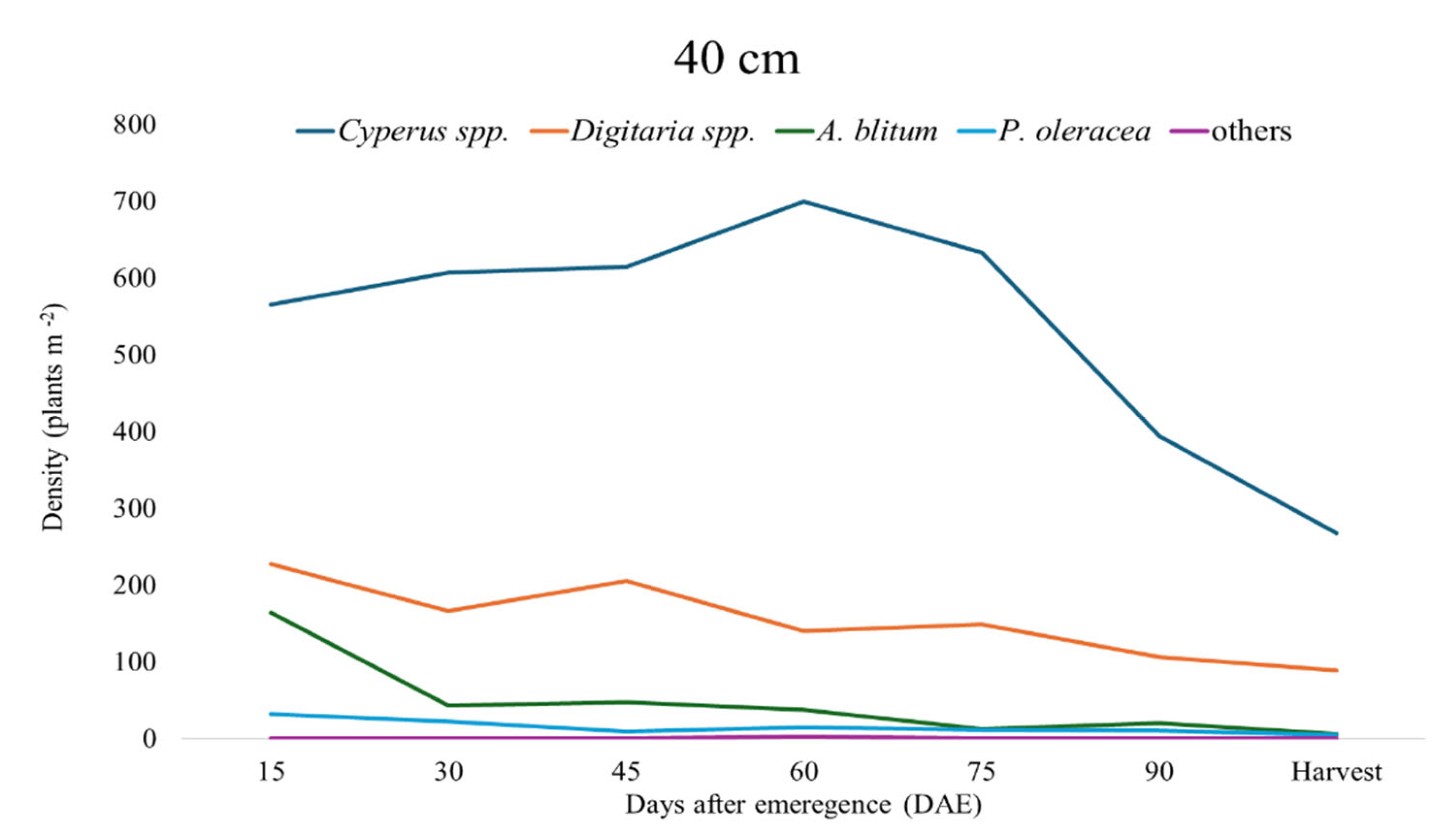

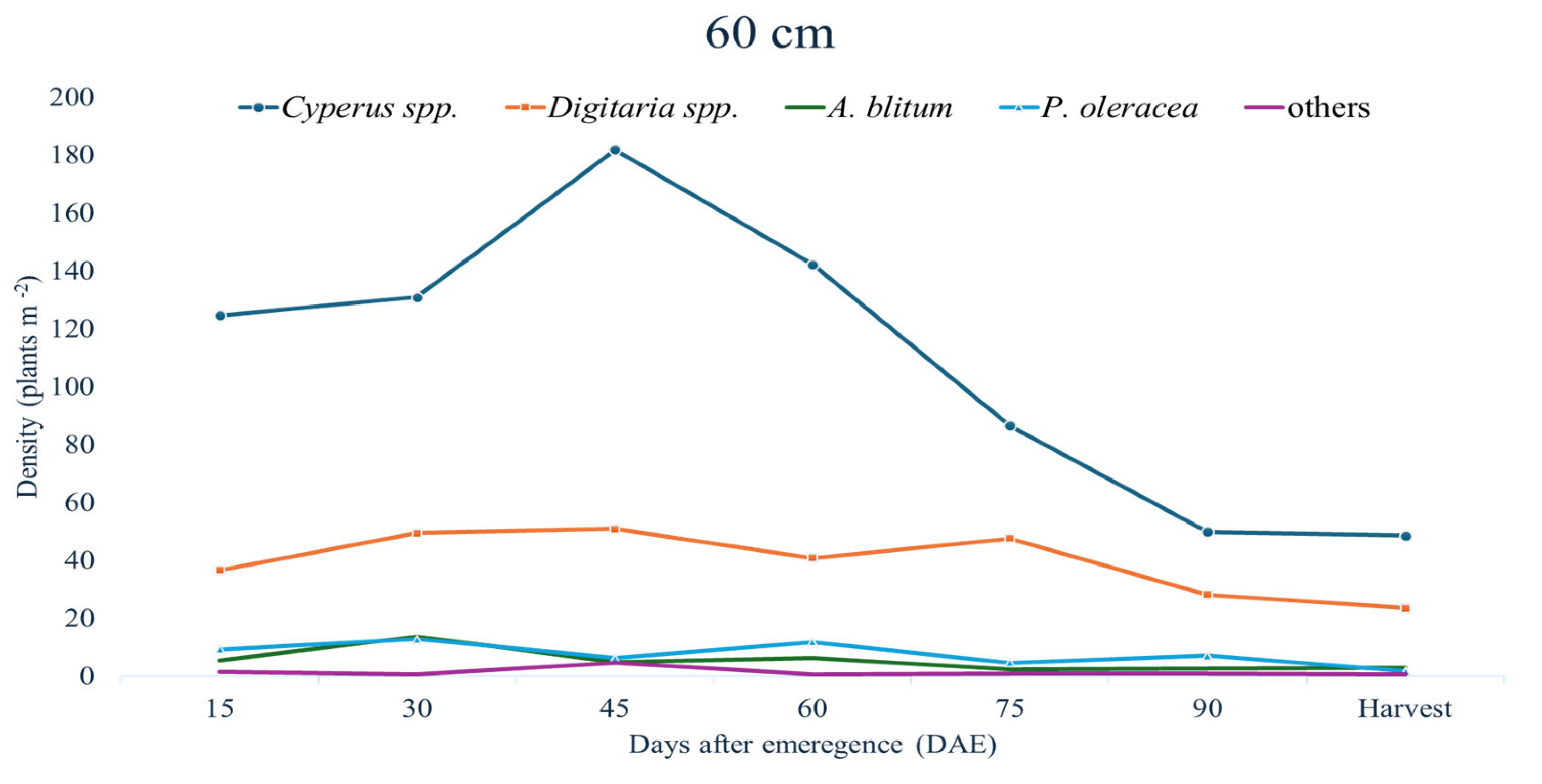

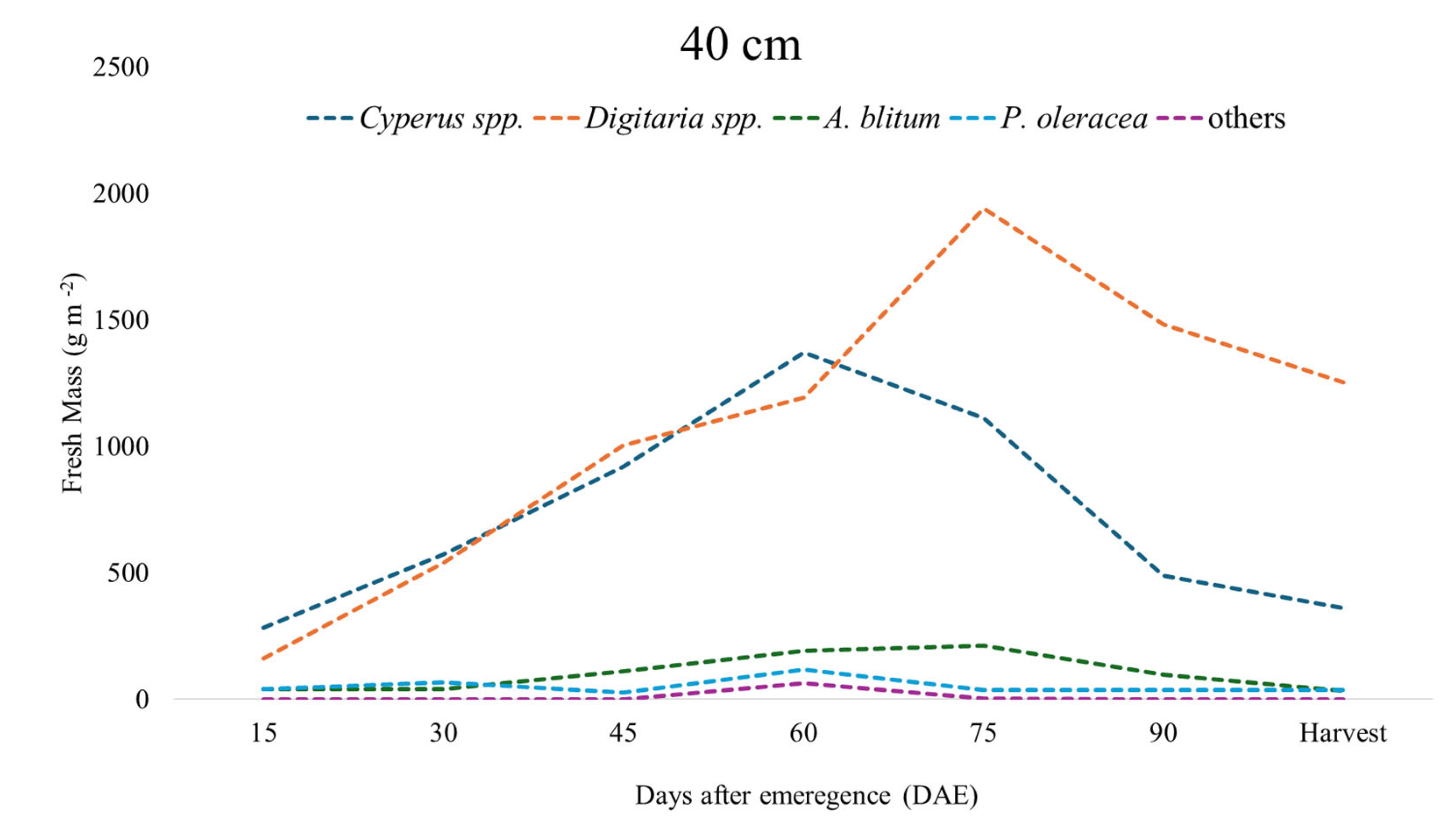

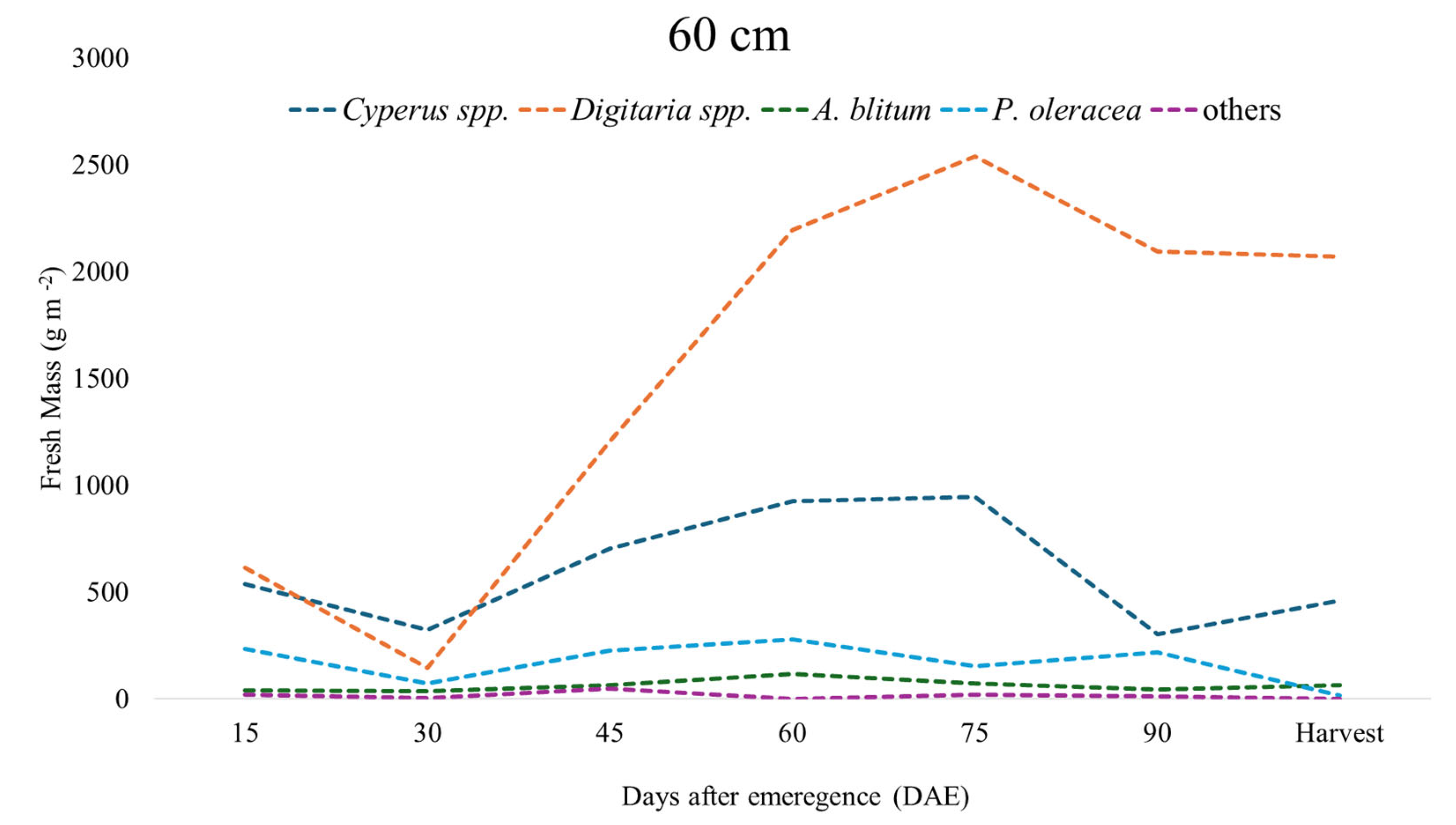

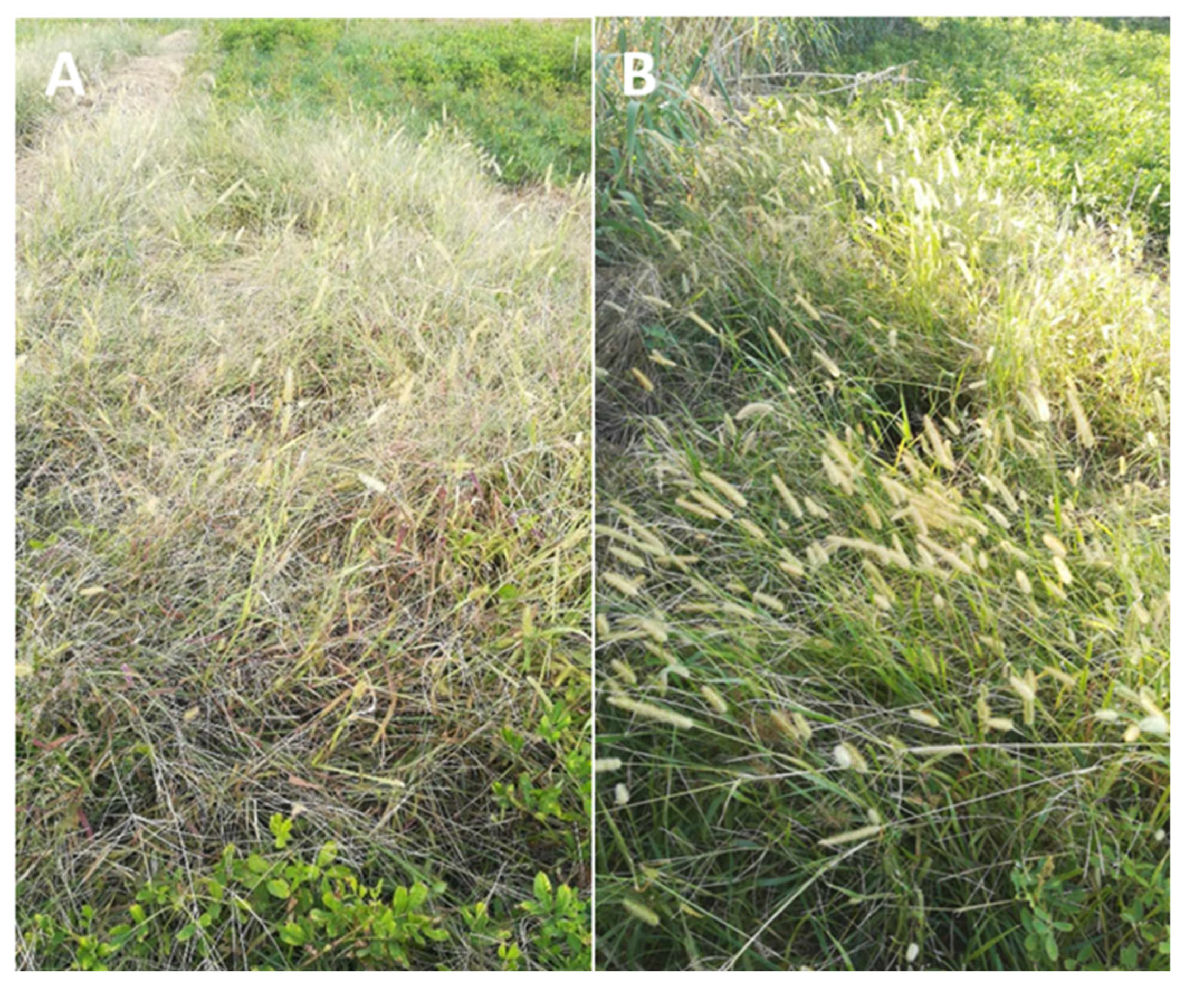

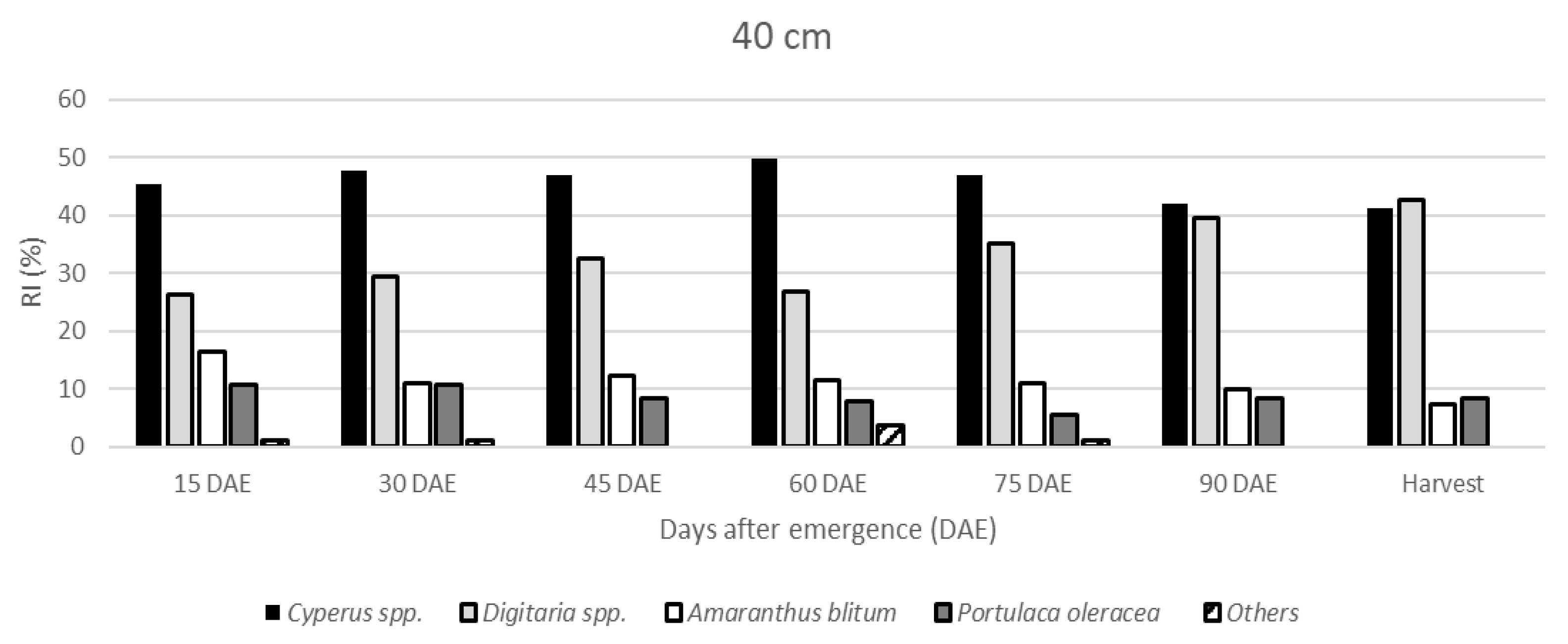

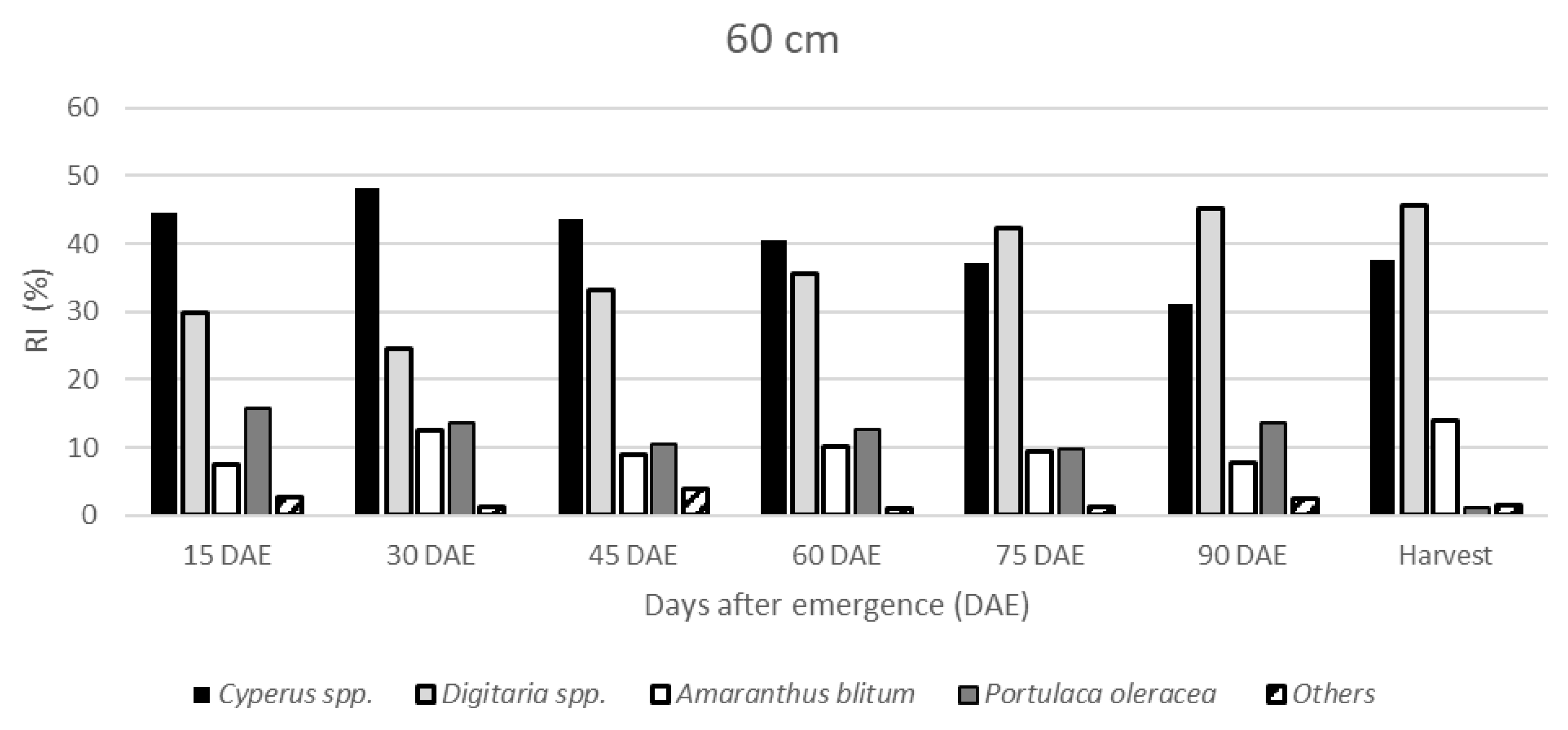

3.1. Weed Community

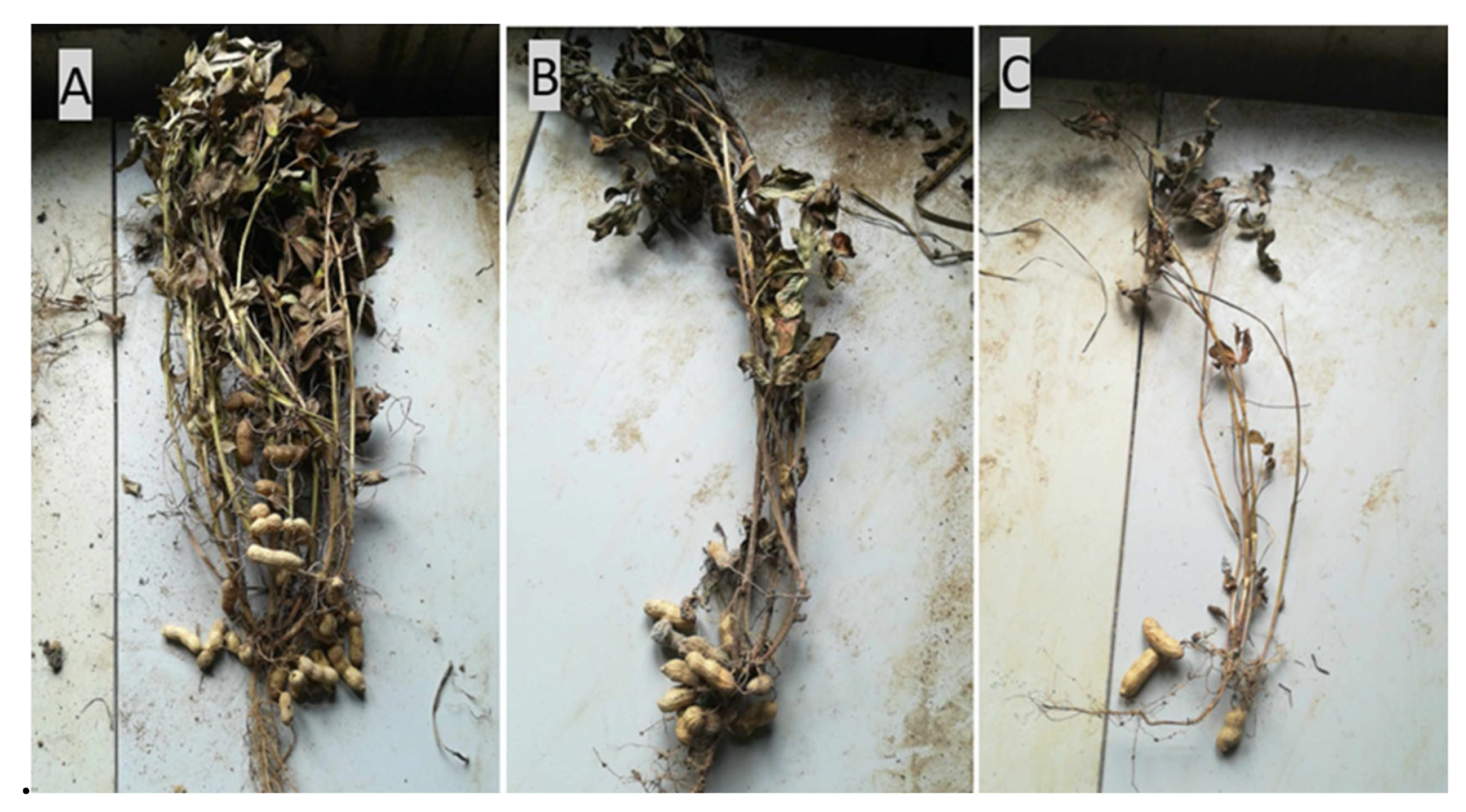

3.2. Crop Production

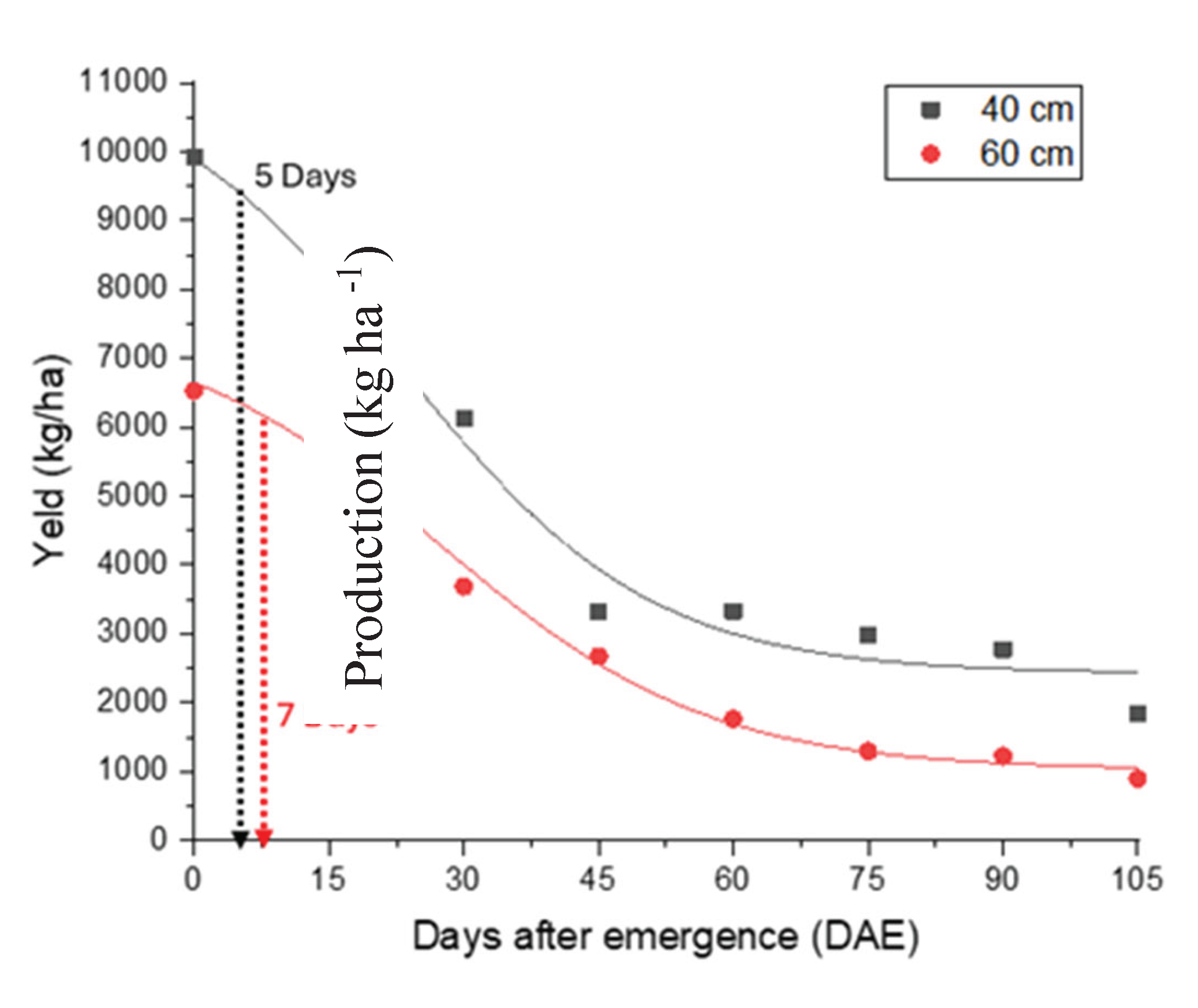

3.3. Period Prior to Interference (PPI)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinto, R. 2015. Amendoim português consumido em snacks na Holanda vai finalmente entrar no mercado nacional. Expressão 50. Available at: https://expresso.pt/iniciativaseprodutos/premio-producao-nacional-2015/2015-06-11-Amendoim-portugues-consumido-em-snacks-na-Holanda-vai-finalmente-entrar-no-mercado-nacional-2 (accessed 5 Dec. 2024).

- Duarte, A. M. M. Amendoim—A «Noz Subterrânea». Cultivo em Aljezur. Al-Rihana 2008, 4, 23–41, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260986176_AMENDOIM_-_A_NOZ_SUBTERRANEA_CULTIVO_EM_ALJEZUR. [Google Scholar]

- Haro, R. J.; Carrega, W. C.; Otegui, M. E. Row spacing and growth habit in peanut crops: Effects on seed yield determination across environments. Field Crops Research 2022, 275, 108363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, G.D.; Alves, P.L.C.A.; Beltrão, N.E.M.; Vale, L.S. Períodos de interferência das plantas daninhas em algodoeiro de fibra naturalmente colorida ‘BRS Verde’. Industrial Crops and Products 2011, 34, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, I.A.A.; Freitas, F.C.L.; Negreiros, M.Z.; Freire, G.M.; Aroucha, E.M.; Grangeiro, L.C.; Lopes, W.A.R.; Dombroski, J.L.D. Interferência das plantas daninhas sobre a produtividade e qualidade de cenoura. Planta Daninha 2010, 28(2), 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitelli, R.A.; Ferraz, E.C.; de Marinis, G. Efeitos do período de matocompetição sobre a produtividade do amendoim (Arachis hypogaea L.). Planta Daninha 1981, 4(2), 110–119. [CrossRef]

- Yamauti, M.S.; Alves, P.L.C.A.; Nepomuceno, M.; Martins, J.V.F. Adubação e o período anterior à interferência das plantas daninhas na cultura do amendoim. Planta Daninha 2010, 28(spe), 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, G.D.; Alves, P.L.C.A.; Beltrão, N.E.M.; Vale, L.S. Períodos de interferência das plantas daninhas em algodoeiro de fibra colorida ‘BRS Safira’. Revista Ciência Agronômica 2010, 41, 456–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, F.; Gravena, R.; Alves, P.L.; Salgado, T.; Mattos, E. The Effect of Cultivar on Critical Periods of Weed Control in Peanuts. Peanut Sci. 2006, 33, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreira, M.C.; Alves, P.L.C.A. Comparação entre métodos para determinar o período anterior à interferência de plantas daninhas em feijoeiros com distintos tipos de hábitos de crescimento. Planta Daninha 2014, 32, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielle, R.F.; Zanoni, H.M.L.; Parreira, M.C.; Alves, P.L.C.A.; Portugal, J. Periods of Weed Interference on Bean Crop with Cultivar Plants of Different Architecture Types. Res. J. Life Sci. Bioinform. Pharm. Chem. Sci. 2019, 5, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, H.; Rajabipour, A.; Mohtasebi, S.S. Moisture-Dependent Some Engineering Properties of Soybean Grains. Agric. Eng. Int. 2009, 1110(11). https://cigrjournal.org/index.php/Ejounral/article/view/1110.

- Oliveira, I. Técnicas de regadio. Técnicas de Regadio 2011, 2(1). https://tecnicasderegadio.info/.

- Brito, R. São Miguel, a Ilha Verde: Estudo Geográfico (1950–2000). Ponta Delgada: Fábrica de Tabaco Micaelense, SA; COINGRA—Companhia Gráfica dos Açores, Lda; EDA—Empresa de Electricidade dos Açores, SA; Universidade dos Açores. 2004. https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.535086.

- Fernandes, João Filipe. (2004). Caracterização Climática das ilhas de São Miguel e Santa Maria com base no Modelo CIELO. [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Dombois, D.; Ellenberg, H. Aims and Methods of Vegetation Ecology; John Wiley and Sons: New York, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kuva, M.A.; Pitelli, R.A.; Christoffoleti, P.J.; Alves, P.L.C.A. Períodos de interferência das plantas daninhas na cultura da cana-de-açúcar: I-Tiririca. Planta Daninha 2000, 18, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H.P. Weeds: Peanuts. In Field Crops—Pest Management Guide 2011; Hagood, E.S., Herbert, D.A., Eds.; Virginia Tech: Virginia, USA, 2010; pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauti, M.S.; Alves, P.L.C.A.; Nepomuceno, M.; Martins, J.V.F. Adubação e o período anterior à interferência das plantas daninhas na cultura do amendoim. Planta Daninha 2010, 28, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.G.S.M.; Rodrigues, F.M.; Oliveira, E.M.; Vieira, V.B.; Arévalo, A.M.; Viroli, S.L.M. Amendoim (Arachis sp.) como fonte na matriz energética brasileira. J. Bioenergy Food Sci. 2016, 3(3), 178–190. [CrossRef]

- Paquete, I.P. A cultura do amendoim, Arachis hypogaea L., na região do Ribatejo: Estudo preliminar. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Portugal, 2012. https://repositorio.ulisboa.pt/bitstream/10400.5/5266/1/tese%20-%20Vers%C3%A3o%20Definitiva.pdf? [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, A.P.; Sousa, L.F.; Santos, M.J.; Almeida, R.C.; Lima, S.V. Eficácia de controle do herbicida Falcon (Piroxasulfona + Flumioxazina) em aplicações em pré-emergente das espécies Cyperus rotundus e Cyperus esculentus. Rev. Foco 2023, 11(16), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira Júnior, M.A.D. Crescimento das culturas de feijão, milho e mandioca em competição com as plantas daninhas picão-preto e capim marmelada em função de densidade de plantas. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal dos Vales do Jequitinhonha e Mucuri, 2015. https://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/UFVJM-2_a0a6916094dcba222dc7345b8579f5ec.

- Fontana, L.C.; Rigon, J.P.G.; Schaedler, C.E.; Zílio, M. Levantamento de espécies de Digitaria (“milhã”) em áreas de cultivo agrícola no Rio Grande do Sul (Brasil). Rev. Bras. Biociênc. 2016, 14(1). https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/rbrasbioci/article/view/114699.

- Souza Junior, N.L.D.; et al. Período anterior da interferência das plantas daninhas no amendoim em resposta a densidade de plantas e espaçamentos. Agron. Trop. 2010, 60(4), 341–353. http://www.publicaciones.inia.gob.ve/index.php/agronomiatropical/article/view/312.

- Yamauti, M.S.; Alves, P.L.C.A.; Bianco, S. Effects of mineral nutrition on inter- and intraspecific interference of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and hairy beggarticks (Bidens pilosa L.). Interciencia 2012, 37(1), 65–69. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/339/33922709011.pdf?

- Dias, T.C.S.; Alves, P.L.C.A.; Pavani, M.C.M.; Nepomuceno, M. Efeito do espaçamento entre fileiras de amendoim rasteiro na interferência de plantas daninhas na cultura. Planta Daninha 2009, 27, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devechio, F.D.F.S.; Pedroso, R.M.; Silva, B.C.; Santos, D.J.D.; Ramos, F.C.; Belchior, F.S.; Costa, H.A.D. Manejo fitotécnico de culturas leguminosas e oleaginosas: Cultura amendoim. Manejo Fitotécnico de Culturas Leguminosas e Oleaginosas: Cultura Amendoim 2021. http://ibict.unifeob.edu.br:8080/jspui/bitstream/prefix/4515/1/Relatorio1_Modulo5_Grupo2_EAD_2021.

| Temperature (ºC) | HR | Rainfall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Max | Min | Media | (%) | (mm) |

| Jun | 24,5 | 16,1 | 20 | 88,2 | 15 |

| July | 25,8 | 15,3 | 20,4 | 80,5 | 16,5 |

| August | 37,7 | 20,4 | 27,3 | 81,1 | 48,5 |

| September | 40 | 17 | 24,6 | 79,5 | 43,2 |

| October | 24,5 | 17.5 | 21,2 | 84,4 | 42,8 |

| Family | Scientific name | Groups |

|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | Amaranthus blitum L. | Eudicots |

| Asteraceae | Sonchus oleraceus L. | Eudicots |

| Cyperaceae | Cyperus spp. | Monocots |

| Plantaginaceae | Plantago lanceolata L. | Eudicots |

| Poaceae | Digitaria spp. | Monocots |

| Polygonaceae | Polygonum lapathifolium L. | Eudicots |

| Rumex azoricus Rechinger | ||

| Portulacaceae | Portulaca oleracea L. | Eudicots |

| 40 cm DAE |

Nº pods | Weight Pods (g) |

Nº total seeds |

Nº marketable pods |

Weight marketable pods (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 17,25 a | 28,32 a | 41,75 a | 13,50 a | 25,20 a |

| 15 | 14,00 ab | 22,87 ab | 33,00 ab | 11,25 ab | 20,47 ab |

| 30 | 11,20 c | 17,50 bc | 24,00 bc | 8,50 bc | 15,47 bc |

| 45 | 6,50 cd | 9,52 cd | 13,75 cd | 5,00 cd | 8,90 cd |

| 60 | 6,25 cd | 9,52 cd | 13,50 cd | 4,50 cd | 8,37 cd |

| 75 | 5,50 d | 8,52 d | 12,75 cd | 4,00 d | 7,52 d |

| 90 | 5,25 d | 7,92 d | 11,25 cd | 4,00 d | 7,00 d |

| Harvest | 3,00 d | 5,27 d | 6,75 d | 2,25 d | 4,77 d |

| F trat | 19,24** | 23,62** | 19,46** | 20,96** | 22,98** |

| CV (%) | 26,29 | 24,86 | 28,23 | 26,40 | 25,09 |

| 60 cm DAE |

Nº pods | Weight Pods (g) |

Nº total seeds |

Nº marketable pods |

Weight marketable pods (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 21,00 a | 27,97 a | 47,00 a | 13,00 a | 21,40 a |

| 15 | 17,50 a | 25,17 a | 40,00 a | 11,75 a | 19,87 a |

| 30 | 12,25 b | 15,80 b | 28,00 bc | 7,50 b | 12,17 b |

| 45 | 8,00 bc | 11,47 bc | 18,50 c | 6,00 bc | 9,87 bc |

| 60 | 5,75 cd | 7,55 cd | 12,25 d | 3,50 bc | 6,25 bc |

| 75 | 4,50 cd | 5,55 cd | 9,75 d | 3,25 c | 4,97 bc |

| 90 | 4,25 cd | 5,25 cd | 9,00 d | 2,75 c | 4,72 bc |

| Harvest | 2,75 d | 3,83 d | 7,00 d | 2,50 c | 3,65 c |

| F trat | 52,86** | 33,89** | 35,85** | 21,99** | 18,54** |

| CV (%) | 19,52 | 25,03 | 23,80 | 28,14 | 31,16 |

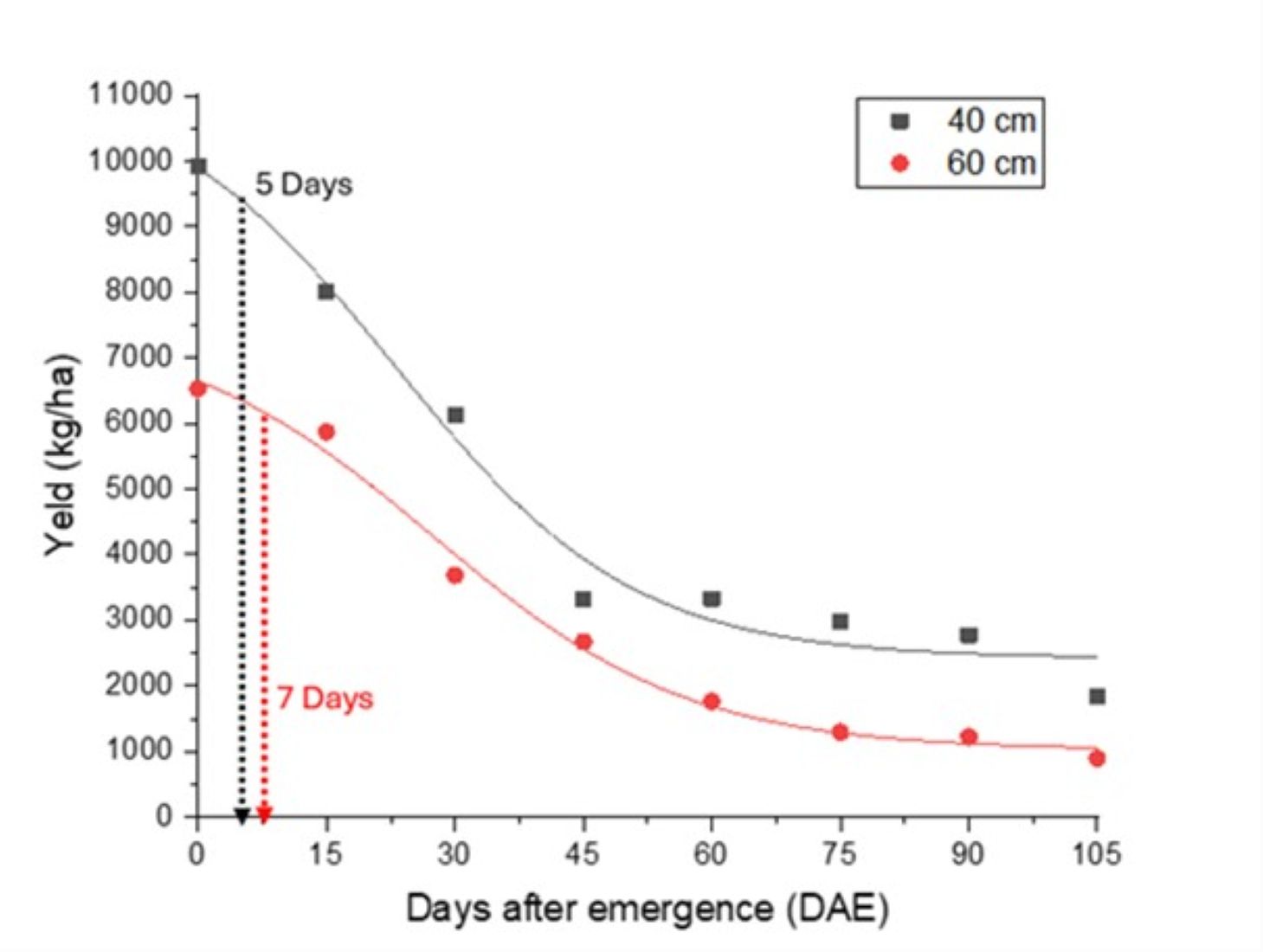

| Parameters | 40 cm | 60 cm |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | 9,91 | 6,53 |

| A2 | 1,84 | 0,89 |

| dx | 13,87 | 14,87 |

| R2 | 0,96 | 0,98 |

| Decrease in production (%) | 81 | 86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).