1. Introduction

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), created in 1992, is an international treaty focused on reducing harmful anthropogenic impacts on climate. The Conference of the Parties (COP) is the UNFCCC’s executive frame that discusses solutions to climate issues. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol was formed as a legal agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (EC, 2025a). During the first commitment period from 2008 to 2012, participating countries aimed for a 5% reduction from 1990 levels, with the EU committing to an 8% cut of gas emissions (EC, 2025b). The EU successfully reduced emissions by 11. 7% during this period (EC, 2025c).

The Kyoto Protocol introduced three mechanisms: Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), Joint Implementation (JI), and Emissions Trading (ET) to help countries limit greenhouse gas emissions, creating a carbon market (UN, 2025).

The CDM allows countries to undertake emission-reduction projects in developing nations and earn certified emission reduction (CER) credits. (UN, 2025a). Joint Implementation enables countries to gain emission reduction units (ERUs) from projects in other country of Kyoto Protocol ’s Annex B, with each ERU and CER equal to one tonne of CO2 and counts to its Kyoto target (UN, 2025b). The targets agreed by the parties in Annex B of the Kyoto Protocol from 2008 to 2012 represent allowed emissions, known as assigned amounts. These emissions are divided into assigned amount units (AAUs). Countries with extra units sell them to those that exceed their targets, creating the emissions trading system focused on carbon dioxide(UN, 2025c).

In 2012, at the UN Climate Change Conference in Doha, the second commitment period was established, where volunteer guarantees by more than 80 countries, including the U.S.A, China, India, South Africa and Brazil agreed to limit emissions by 2020 (EC, 2025c). The second commitment period from 2013 to 2020 aimed for a 20% reduction by EU countries compared to 1990 levels (EC, 2025d).

At COP21 in Paris in 2015, all UNFCCC parties adopted the Paris Agreement to limit global temperature rise to 2°C, with efforts to keep it to 1. 5°C, by the end of the century (EC, 2025a).

In 2008, the EU aimed to reduce their emissions by 20% by 2020 compared to 1990 and obtained a 30% reduction. In 2014, a target was set of 40% emissions reduction by 2030. In 2023, the aim increased to 55% emissions to be reduced by 2030 and the goal of zero emissions by 2050. The European Commission launched the Green Deal Strategy to achieve climate neutrality within the scope of Paris Agreement. The European Climate Law supports this strategy, requiring a change in the economic model across all sectors. (EC, 2025a; European Council, 2025c).

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement has created new options for voluntary carbon markets, allowing countries to count carbon offsets toward their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). This highlights the value of voluntary markets and officially recognizes this compensation system, suggesting future standardization at national and international levels. New market actions are emerging due to the demand for quality credit trading and the connection between private carbon markets and governments (Dawes, et al., 2023).

Several European Commission strategies aim to improve or protect natural carbon sinks and ecosystems for carbon removal. These strategies include the biodiversity strategy, the farm to fork strategy, the forest strategy, and the nature restoration law. Regulation (EU) 2018/841 on land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) has been the principal piece of EU legislation for carbon removals (European Parliament, 2024).

The Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming (CRCF) Regulation was published on 6 of December of 2024 with the aim:

“… to develop a voluntary Union certification framework for permanent carbon removals, carbon farming and carbon storage in products (the ‘Union certification framework’), with a view to facilitating and encouraging the uptake of high-quality carbon removals and soil emission reductions, in full respect of the Union’s biodiversity and the zero-pollution objectives, as a complement to sustained emission reductions across all sectors” (Regulation 2024/3012).

On 5 of January of 2024, in Portugal it was published the Decree Law 4/2024 which establishes the voluntary carbon market and the rules for its operation (Decree Law 4/2024).

The contribution of this paper is to explore the voluntary carbon market in Portugal and EU with the potential of sustainable agriculture practices to lessen environmental impacts. This study reviews global compliance and voluntary carbon credit markets, focusing on Portugal’s voluntary carbon market and the EU Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming (CRCF) Regulation, and agriculture soil carbon markets.

2. Compliance and Voluntary Carbon Credit Market Mechanisms: A Global View

The Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and the Marrakech Accords in 2001 launched the outset of using market strategies to combat climate change (Michaelowa et al., 2019b). At Kyoto Protocol it was proposed three mechanisms: Emission Trading, Joint Implementation (JI), and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The CDM became a key standard for emission reduction projects between developed and developing countries. As the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol ended in 2020, the CDM is transitioning to the Sustainable Development Mechanism (SDM ) (UNDP, 2024).

Emission allowances, permit the emission of one tonne of CO2 equivalent, arise from cap-and-trade mechanisms, like the European Emission Trading System (EU ETS), where a limit of GHG emissions allowed is settled (cap) and conceding companies to buy and sell to meet emission reduction targets (Lovell,2010; EC, 2025e). As the cap decreases, the supply of allowances in the market also reduces (EC, 2025)e. The demand of carbon credit increased with EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and its connections to the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). However, the trade for CERs has reduced and led to flat carbon prices since 2013 (Michaelowa, et al.,2019b). The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) is crucial for reducing net emissions by at least 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels. Emissions from electricity, heat, industrial, aviation, and maritime transport are covered by EU ETS. In 2027, starts ETS2 scheme for buildings and road transport emissions. The 2023 revision of the EU ETS Directive seeks to reduce emissions by 62% from 2005 levels and reach climate neutrality by 2050 (EC, 2025e).

The Paris Agreement in 2015, required countries to set their own Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for climate mitigation ((Michaelowa, et al., 2019a; Ahonen, et al., 2022). The Article 6 of the Paris Agreement supports governments in implementing their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) through voluntary international cooperation. It allows for an emissions trading system for Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMO) or carbon credits. This promotes collaboration among countries and encourages private sector involvement in reducing emissions, while also recognizing the importance of voluntary carbon markets in achieving additional emission reductions (UNDP, 2024; Dawes, et al., 2023; Michaelowa, et al., 2019b). Article 6.4 settles a global, centrally managed baseline and credit mechanism which is like the CDM for international governance and JI for avoiding double counting (Ahonen, et al.,2022). The private sector plays a vital role in financing and for technology transfer, those being necessary, as well as innovation to meet NDC targets (UNDP,2024).

The voluntary and compliance markets originate carbon offsets. Both types of markets struggle for an equilibrium between bureaucracy, transparency and fastness in production and consumption management of carbon offsets (Lovell, 2010). Private, self-governed baseline-and-credit mechanisms have emerged for voluntary mitigation actions outside Kyoto Protocol targets (Ahonen, et al., 2022). The voluntary market lets companies and individuals offset their greenhouse gas emissions. Individuals, NGOs and businesses, can produce and use these voluntary offsets as they intend (Lovell, 2010). Voluntary carbon markets allow companies to set their own emissions targets without legal cap. These targets often align with business promotion strategies and Corporate Social Responsibility investments (UNDP, 2024).

An increment of net-zero targets by different stake holders affects national laws and corporate plans and blears voluntary and compliance lines of operation (Ahonen, et al., 2022). In California, the Climate Action Reserve (CAR) created crediting project methodologies that the California Compliance Carbon Offset Program adopted with changes (Broekhoff, et al., 2019).

The request for quality credits, and the interconnection between private carbon markets and governments driven to new market initiatives, as new trade infrastructure and project certification. Many initiatives are developing a hybrid model where the government actively regulates voluntary carbon credit trading (Ruiting,et al., 2025). Adjusting essential criteria and accounting in different baseline and credit mechanisms from both voluntary and compliance actors leads to global carbon mitigation ambition. Public and private stakeholders’ efforts led to the segmentation of the carbon market causing disintegration and complexity, and reduced trust in carbon market integrity, after the decline of climate policy in 2009 (Ahonen et al., 2022).

Governments can help standardize and improve credit quality as companies face challenges due to various standards and brokers in voluntary carbon markets. Governments can also direct funding to specific projects based on critical goals and restrict eligibility to certain technologies or locations, as the EU’s certification framework that brace innovative carbon removal technologies and projects related to industrial technologies and sustainable farming. Government has a crucial role on aiming to improve transparency, standardization, and investor confidence on long term voluntary markets for carbon neutrality and emissions mitigation. Governments perform special regulatory authority that can enhance credit supply and trade infrastructure in these markets (Dawes, et al., 2023).

The following table indicates several governments’ trade schemes:

Table 1.

Governments’ carbon trade schemes.

Table 1.

Governments’ carbon trade schemes.

| Governments carbon market denomination |

Government Carbon market initiative |

| London Stock Exchange (LSE) |

In February 2022, LSE introduced a market designation for carbon credits to enhance transparency and move trading from an over-the-counter model to a structured marketplace. While it aims to boost investor confidence, it does not assess the quality of carbon projects. Companies need to report, but the verification is based on existing standards like Verra and the Gold Standard. Dawes, et al., (2023). |

| Energy Transition Accelerator (ETA) |

Launched at COP27, this collaboration involves the U. S. State Department, Bezos Earth Fund, and Rockefeller Foundation to support climate finance in developing countries. Companies seeking net-zero goals will invest in carbon credits from projects in these regions (Dawes, et al., (2023). |

| Australia’s Emissions Reduction Fund |

Australia’s Emissions Reduction Fund encourages the reduction of greenhouse gases through Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs). Dawes, et al., (2023). the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) allows the Clean Energy Regulator to buy offsets from land-use (the Carbon Farming Initiative, CFI) and industrial sectors. Established in 2014, it uses a competitive reverse auction system, accepting bids below a set benchmark price. Project developers can obtain Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) through this process. The ERF replaced a previous carbon pricing mechanism from the Clean Energy Act 2011, which was repealed in July 2014. (Michaelowa, 2019b). The Australian Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) was created under the Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Act 2011 and launched in 2015. It is a voluntary program designed to encourage organizations and individuals to adopt new practices and technologies to reduce emissions, aiming for the lowest cost of abatement through reverse auctions. The Clean Energy Regulator (CER) oversees the ERF. The program explores various carbon mitigation methods across sectors like agriculture, energy, and waste. Current focus areas include soil carbon and carbon capture. All projects must be conducted in Australia (McDonald, et al. 2021). |

| Japan GX League |

Japan initiated the GX League to help achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, focusing on voluntary emissions reductions through a trading scheme (Dawes, et al., 2023). |

| The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme |

The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme has operated since 2008, covering all sectors including forestry and agriculture, and is managed by the NZ Ministry for the Environment (McDonald, et al.,2021) |

| The Carbon Fund for a Sustainable Economy (FES-CO2) |

The Carbon Fund for a Sustainable Economy (FES-CO2) was established in 2011 to buy carbon credits, including Verified Emissions Reductions (VERs) from projects in Spain. The fund mainly operates nationally but can also buy credits from international markets. It focuses on sectors outside the EU-ETS and prioritizes energy efficiency and renewable energy projects. FES-CO2 purchases VERs at a fixed price during the first four years of the project (Michaelowa, et al.,2019b). |

| Korea Emissions Trading System |

The Korea Emissions Trading System was launched in 2015 as the first national mandatory emissions trading system in East Asia. By 2022, it covered 79% of South Korea’s greenhouse gas emissions. The K-ETS aims to help South Korea achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, as stated in the 2021 “Carbon Neutral Framework Act.” It includes major emitters from sectors as power, industrial, buildings, waste, transport, domestic aviation and maritime sectors (ICAP, 2025). |

| The French Label Bas Carbone (LBC) |

The French Label Bas Carbone (LBC) is a framework established by the French Government in November 2018 for voluntary carbon reduction and removal projects. It primarily focuses on forestry and agriculture but is expanding to other sectors. Managed by the Ministry for Ecologic and Solidary Transition, it allows French entities to voluntarily compensate for their emissions. The standard applies to all sectors not covered by the EU ETS and is only available in France.(McDonald, et al., 2021). |

| British Columbia Registry |

British Columbia has set up a domestic offset scheme through the BC Carbon Registry, which allows for the creation, transfer, and retirement of offset units. These units can be sold to government entities needing to be carbon neutral or to participants in the voluntary market. In California, an emissions trading scheme limits greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from major sources, allowing compliance through California Air Resources Board (ARB) offset credits. Projects eligible for these credits include livestock, mine methane capture, and forest initiatives, which can be certified under ARB, INCLUDING approved standards like ACR, CAR, and Verra ( Michaelowa et al., 2019b). |

3. Voluntary Carbon Markets

In the late 1980s, companies began reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions using carbon credits, leading to the creation of the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM). Early participants included Applied Energy Services (AES), which funded tree planting projects with NGOs like CARE in Guatemala. In the mid of 1990s,the Environmental Resources Trust, later known as the American Carbon Registry (ACR), became the first private registry for voluntary offsets in the U.S. The VCM grew significantly in the 2000s, introducing key private carbon standards like the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), Gold Standard (GS), ACR, and the Climate Action Reserve (CAR). Other standards like the Global Carbon Council, Plan Vivo, and Climate Forward also exist (UNDP,2024). Since then, more than hundred companies and NGOs trades carbon credits to individual consumers and companies not regulated by state emissions-reduction laws (Lovell, 2010). The demand for carbon offsets needs stricter standards and verification, focusing on biodiversity conservation and social equity to support sustainability goals (Ruiting, et al., (2025);Michaelowa, et al., 2019b).

Various carbon offset registries have developed without mandatory regulations for voluntary carbon credits (VCCs), each with its own standards for project eligibility and emission reduction verification. These registries have specific terms of operation for user access and play a key role in tracking offsets. The standards ensure that VCCs and their related projects are of acceptable quality and reflect real emission reductions (ISDA, 2022).

Table 2.

Outstanding Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) standards.

Table 2.

Outstanding Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) standards.

| Outstanding VCM standards |

Description |

| The Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) |

The Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) is a voluntary mechanism for carbon mitigation established in 2005 by IETA, World Economic Forum, World Business Council and other organizations to ensure quality in voluntary carbon markets. Operated by non-profit corporation, Verra, it is the largest global mechanism for voluntary carbon offsetting, also relevant for ICAO CORSIA and carbon tax regulations in Colombia and South Africa. The carbon mitigation and carbon removal methodologies regard Energy, Industrial processing, Construction, Transport, Waste, Mining, Agriculture, Forestry, Grasslands, Wetlands, Livestock and Manure. It also permits CDM or Climate Action Reserve methodologies. (McDonald, et al., 2021). |

Gold Standard

|

Gold Standard was founded in 2003 by WWF and other international NGOs to certify and facilitate voluntary offsetting of carbon emissions. It operates worldwide and is the second-largest independent offset mechanism for emissions reductions and removals. Most Gold Standard credits are used voluntarily, but some are accepted in regulatory systems like the carbon tax in Colombia and South Africa.

Gold Standard focuses on carbon removal solutions, including nature-based solutions like afforestation and agriculture soil carbon (McDonald, et al., 2021). |

| The California Compliance Offset Scheme (CCOP) |

The California Compliance Offset Scheme (CCOP) started in 2013 matching the California Cap-and-Trade program, which aims to cut emissions by 40% by 2030 and 80% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. Projects must meet Compliance Offset Protocols and follow one of six sectoral methodologies: U. S. Forest, Urban Forest, Livestock, Ozone Depleting Substances, Mine Methane Capture, and Rice Cultivation and occur in California, Canada and the USA. The CCOP only covers the USA, Mexico, and Canada ( McDonald, et al., 2021). |

| Plan Vivo |

Plan Vivo is a crediting program for Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use (AFOLU) that aims to support sustainable development and enhance ecosystem services and improve rural way of life. Plan VIVO projects deals with rural smallholders and emphasizes native species use, and biodiversity enhancement through various payment schemes. The program began in 1994 as a pilot project in Chiapas, Mexico. (Broekhoff, et al., 2019). |

| CORSIA |

The ‘Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation’ (CORSIA) was established in 2016 to limit CO2 emissions from international flights. It is the first global scheme for air transport’s CO2 emissions. The EU Emissions Trading System also addresses these emissions but is currently limited to the European Economic Area.(McDonald, et al., 2021). |

4. Portugal’s Voluntary Carbon Credit Market and CRCF—EU Carbon Removals & Carbon Farming Regulation

In Portugal during the 1990s, there were an increase in GHG emissions which reached its peak emissions in 2005. Since then, the country has shown a decarbonization trajectory with a significant emissions reduction. Emissions were about 44% higher in 2005 than in 1990. In 2017, GHG emissions, excluding land use, Land use change and forestry (LULUCF), shown an increase of about 19.5% compared to 1990. With the LULUCF sector included, represented an increase of 29.2% compared to 1990, due to the 2017 rural fires (RNC2050, 2019) .The Law No 98 /2021 of 31 of December of 2021, defines the basis of climate policy and states that Portugal is committed to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 (Law No 98/2021). In 2022, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, excluding land use, land use change and forestry, down 4.4% from 1990 and 34.5% from 2005. Including land use, land use change and forestry, emissions slightly increased by 0.3% from 2021, which is 23.6% lower than in 1990 and 43.7% lower than in 2005. The sectors of energy, agriculture, industrial processes, and waste accounted for 67.2%, 12.3%, 10.4%, and 10.0% of total emissions in 2022 (APA,2025). After 2005, cleaner energy and energy efficiency measures reduced emissions. Following the 2008 financial crisis, Portugal’s economy augment, raising energy consumption and emissions. However, from 2014 to 2017, the emissions growth halted due to more renewable energy and smaller use of coal for electricity. In 2022, considering reductions in certain livestock and fertilizer use, agriculture emissions decreased by 5.4% since 1990 and accounted for 12% of national emissions. Nevertheless, emissions raised from 2011 to 2022 by 7%, because of increased livestock. From 2021 to 2022, emissions fell by 4.2%, due to decreased inorganic fertilizer use and lower herd sizes (APA, 2024)

The Fit for 55 package, is an assortment of laws that aims to strengthen the EU ETS and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels (European Council , 2025c). The reduction targets were set at 62% for EU Emissions Trading sectors and 40% for non-ETS sectors. Portugal aims to cut its non-ETS emissions by 28.7% from 2021 to 2030. Some sectors have reduced emissions since 2005, but transportation, agriculture, and waste are still behind 2030 goals (APA, 2024).

The Roadmap to Carbon Neutrality 2050 (RNC2050,2019) outlines strategies, measures and vision for to be achieved from 2021 to 2030 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions for the aim of carbon neutrality by 2050. It was approved by the Council of Ministers resolution No107/2019 of 1 July, and it was submitted to the UNFCCC in 2019 on 20 September 2019 (PNEC 2030, 2024). The National Energy and Climate Plan 2030 (NECP2030), approved by Council of Ministers Resolution 53/2020, it details aspiring goals for 2030 which are in line with RNC2050 objectives. RNC2050 aimed to identify key sectors that can reduce carbon emissions, such as transport, agriculture, forestry, other land uses and waste (RNC2050,2019). NECP 2030 settled lines of action, one of them was to establish a voluntary carbon market, for the promotion of domestic projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and enhance carbon sequestration, providing environmental and socio-economic co-benefits, as biodiversity protection and natural capital. This includes certifying projects based on European and international regulations to generate carbon credits and creating a framework for emissions offsetting and financial contributions for climate action (PNEC 2030, 2024).

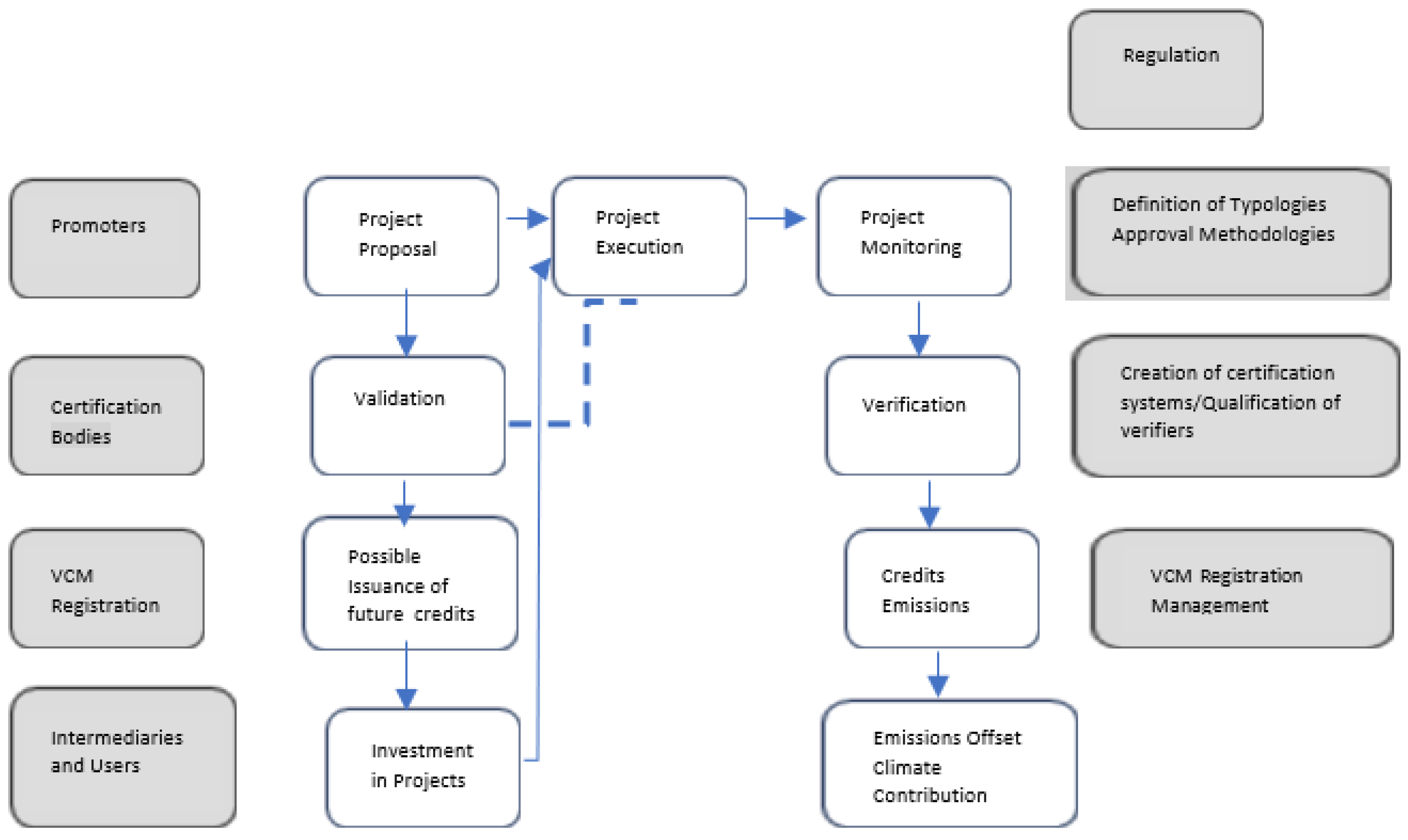

On 5th of January of 2024 was published the Decree-Law 4/2024 which establishes the voluntary carbon market and sets the rules for its operation. The voluntary carbon market aims to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Portugal and meet national and international climate commitments, following the Carbon Neutrality Roadmap 2050 (RNC2050,2019) and the Climate Framework Law (Law No 98/2021). It facilitates projects that either decrease emissions or enhance carbon sequestration, encouraging involvement from individuals and organizations. The voluntary carbon market seeks to engage society in climate transition and environmental conservation through emission compensation actions. It also aims to generate environmental and socioeconomic co-benefits, such as biodiversity protection, improved water and soil quality, and support for a circular economy. The agents of the voluntary carbon market include project promoters, individuals or organizations that buy or use carbon credits, and certification bodies. (DL4/2024). The Portuguese Voluntary Carbon Market will support projects reducing greenhouse gas emissions and sequestering carbon. Eligible projects need to meet criteria and monitoring standards with the support of and independent entity, focusing on forest sequestration projects for conservation and fire resilience (Correia, 2025). The Technical Monitoring Committee oversees developing carbon methodologies. Proposals of methodologies can come from public or private entities but need the Committee’s opinion and approval from APA, I. P., and other relevant bodies (MVC, 2025). National, European or international methodologies, that already exist and adjusted to the national context can be considered for the carbon project, being approved by APA, I. P (DL4/2024).

A digital platform “Voluntary Carbon Market—Towards Climate Neutrality” was created to involve and empower market participants, providing guidance documents and allocation interest in market participation (MVC, 2025).

Figure 1.

Portuguese Voluntary carbon market (VCM) configuration, Source: adapted from (APA, 2023).

Figure 1.

Portuguese Voluntary carbon market (VCM) configuration, Source: adapted from (APA, 2023).

The Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming (CRCF) Regulation, establishes a voluntary framework for certifying carbon removals, carbon farming, and carbon storage in products crosswise Europe. It requires a third-party verification, the publication of certification information in an EU registry and intends to centralize certification processes for cost effectiveness. The European Commission Expert Group on Carbon Removals will create EU certification methodologies and standard procedures for third-party verification ( EC, 2025 f).

The certification framework is voluntary, allowing public and private certification schemes to seek recognition from the European Commission, although it is not required that to operate in the European Union. Reducing emissions from agricultural soils and increasing carbon removal in biogenic carbon pools should be part of carbon farming activities. However, projects like deforestation or renewable energy that don’t improve soil carbon must not be comprised in the Union certification framework. All certified carbon removals and soil emission reductions must support the European Union’s climate goals and nationally determined contributions (NDC) (CRCF, 2024).

5. Agriculture Soil Carbon Market

Non-energy agricultural emissions make up over 12% of global emissions (World Bank. 2025).The Kyoto Protocol broadly excluded emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) and did not consider soil sequestration. It also limited activities acceptable under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), leaving out soil related emissions. In contrast, by the time the Paris Agreement was adopted, 95% of Parties included agriculture in their climate action plans (Von Unger, et al., 2018). Carbon crediting policies are used for non- energy agricultural emissions instead of an ETS or carbon tax (World Bank. 2025). Sustainable farming and soil protection help to decrease greenhouse gases emissions and capture carbon in soil (European Commission, 2019; Lal, 2016).

The increasing of production of food, feed, fibre and bioenergy prejudice natural resources and ecosystems services (IPCC, 2023; IPBES ,2019). The “4 per 1000 Initiative “ Soils for Food Security and Climate” was undertaken at the UNFCCC COP 21 in 2015. This initiative encourages natural carbon sequestration in agricultural and forest soils, aiming for healthier, carbon soils and seeks to demonstrate that agriculture and forest soils can help address climate neutrality and food security. Carbon soils reduce erosion, retain rainwater, enhance fertility, and stabilize crop yields (CGIAR, 2025). Combining climate-smart agriculture practices like precision agriculture (smart irrigation, data decision making or nutrient management) and regenerative agriculture (cover crops, crop rotation and no-tillage) can enhance yields, restore soil health, increase soil carbon sequestration and reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Kabato, et al., 2025). Carbon farming involves practices for farmers and foresters to increment carbon sequestration and storage in soils and thus diminish greenhouse gas emissions. These practices include restoring peatlands and wetlands, agroforestry and mixed farming (trees with crops or livestock), soil protection measures, reforestation, and improving the efficient use of fertilizer. It also provides financial rewards for implementing these practices (EC, 2025 f). The adoption of carbon farming practices, plus a credit carbon certification, promotes the achievement of carbon neutrality and an additional income for farmers (Kyriakarakos et al., 2024).

In Portuguese soils, total nitrogen content predicts soil organic carbon, according to a study using machine learning and econometrics. An equilibrium between carbon-nitrogen is essential for soil fertility and sequestration of carbon. As Portuguese soils usually have low organic carbon levels due to their characteristics, climate, and agroforestry practices (Martinho, et al.,2025).

Reinforcing farming practices for soil organic carbon aids governments and agriculture businesses in reaching net-zero targets. So that, farmers can gain financially from carbon trading (Beka et al., 2022; EC, 2025 f), though measuring SOC can be expensive (Beka et al., 2022). Turning regulatory frameworks into practice can be complex and depends on how policymakers and practitioners focus on farmers’ concerns about attaining contracts of carbon projects. The Farmers’ interest in the agricultural soil carbon market is affected by unclear standards for carbon baselines., thus policymakers need to align farmers’ expectations with market demands (Phelan et al., 2024).

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The use of natural resources to answer human needs has damaged agricultural soils and increased greenhouse gas emissions, leading to climate change. The Paris Agreement aims to reduce temperatures by 1.5ºC by the end of the century, while the EU Green Deal Strategy seeks carbon neutrality by 2050. The European Commission settled the Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming (CRCF) regulation to promote effective carbon removal and reduce soil emissions. Carbon farming practices, which include restoring forests and managing wetlands and peatlands, can help to remove and store carbon and can qualify for certification under EU CRCF regulation. This certification allows farmers to receive additional income. (EC, 2022)

In Portugal, Decree Law nº 4/2024 establishes a voluntary carbon market that prioritizes forestry projects. The law aims to finance projects that safeguard landscapes and forest through the generation of carbon certificates. This initiative addresses the need for funding in priority areas and aims to mitigate climate change while protecting the natural environment (Fernandes, 2024). It is mentioned on Decree Law 4/2024 that “natural-based” solutions for carbon sequestration are not restricted to forests, and there is an important contribution that should also be promoted in other areas, including coastal and marine ecosystems”. In fact, Decree Law 4/2024 does not mention agricultural soil carbon sequestration or carbon farming, However, The National Energy and Climate Plan 2030 (NECP2030) has the action line “6.5 , Increase the natural carbon sink capacity of agriculture and forestry” with “ The aim is to ensure an increase in the carbon sink capacity of agriculture and forestry”, and action line “ 6.5.3. Conserve, restore and improve agricultural and forest soils and prevent erosion” (PNEC 2030, 2024). The Portuguese voluntary carbon market may use national, European and international methodologies if they are adjusted to the national context and approved by APA, I.P (Decree Law 4 / 2024). Portuguese carbon credits may be accepted by CRCF European certification as the CRCF certification allows the recognition of public and private certifications.

The Portuguese voluntary carbon market contributes to the reduction of GHG emissions in Portugal. In agroforestry sector, reforestation projects, using for example, native species in low production areas, creates a biodiverse and fire-resistant landscape. Introducing carbon farming projects at Portuguese VCM, can enhance organic carbon in agricultural soils. These cited features will provide environmental and economic benefits, such as the quality improvement of air, water and soil, with the increase of soil organic matter, biodiversity protection, new ways of profitability for farmers and foresters and thus the valorisation of Portuguese rural territory.

Research is ongoing to explore cost-effective carbon quantification techniques, including machine learning (Martinho, et al.,2025) and to enhance the accuracy of soil carbon methodologies in carbon farming. The LILAS4SOILS project employs a Living Labs approach to support carbon farming in the Mediterranean, proposing innovative methods for soil monitoring and reporting and Verifying (MRV) methodology which intends to add policy consideration for methodologies standards of CRCF Regulation (EIT, 2025).

Portuguese policymakers should include agriculture soil carbon sequestration and carbon farming in the voluntary carbon market to align with European CRCF regulations.

More research, training, and media communication must be done on carbon credit markets, carbon farming and carbon neutrality.

Acknowledgments

This work was developed under the Science4Policy 2023 (S4P-23): annual science for policy project call, an initiative by PlanAPP—Competence Centre for Planning, Policy and Foresight in Public Administration in partnership with the Foundation for Science and Technology, financed by Portugal ́s Recovery and Resilience Plan.

References

- Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente (APA). 2023- Mercado Voluntário de Carbono. Available online: https://apambiente.pt/sites/default/files/_A_APA/Comunicacao/Destaques/2202/MercadoVoluntarioCarbono/Mercado_Voluntario_Carbono_10.03.2023.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente (APA). 2025. Available online: https://rea.apambiente.pt/content/emiss%C3%B5es-de-gases-com-efeito-de-estufa (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente (APA). 2024- Memorando sobre emissões GEE -Inventário Nacional de Emissões 2024 (Emissões de GEE de 1990 a 2022) Memorando sobre emissões de gases com efeito de estufa (GEE) 2024. Available online: https://apambiente.pt/sites/default/files/_Clima/Inventarios/20240408/20240327%20memo_emiss%C3%B5es_2024.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Ahonen, H. M., Kessler, J., Michaelowa, A., Espelage, A.,; Hoch, S. Governance of fragmented compliance and voluntary carbon markets under the Paris Agreement. Politics and governance 2022, 10(1), 4759. [Google Scholar]

- Beka, S., Burgess, P. J., Corstanje, R.,; Stoate, C. Spatial modelling approach and accounting method affects soil carbon estimates and derived farm-scale carbon payments. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 827, 154164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekhoff, D., Gillenwater, M., Colbert-Sangree, T.,; Cage, P. Securing climate benefit: a guide to using carbon offsets; Stockholm Environment Institute & Greenhouse Gas Management Institute, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Removal and Carbon Farming Regulation (CRCF). 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L_202403012 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- CGIAR-Alliance Bioversity International—CIAT-The international “4 per 1000” Initiative (4per11000) ;Soils for Food Security and Climate. 2025. Available online: https://4p1000.org/discover/?lang=en (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Correia S., Vieira G. Forestis—Associação Florestal de Portugal-Desmistificação dos Mercados de Carbono. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, A., McGeady, C.,; Majkut, J. Voluntary carbon markets: A review of global initiatives and evolving models; Center for Strategic and International Studies: Washington, DC, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Decree- Law No 4/2024. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/4-2024-836117866 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- EIT food. LILAS4SOILS Launches New Protocol for Monitoring Soil Carbon Stocks in Mediterranean Farms. 2025. Available online: https://www.eitfood.eu/news/lilas4soils-launches-new-protocol-for-monitoring-soil-carbon-stocks-in-mediterranean-farms (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- EU Commission (EC). CAP Specific Objectives explained (Brief No 4)- AGRICULTURE AND CLIMATE MITIGATION. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). Delivering the European Green Deal First EU Certification of Carbon Removals. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/attachment/874097/Factsheet%20-%20Certification%20of%20carbon%20removals_en.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- European Commission (EC). Global Climate Action. 2025. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/international-action-climate-change/global-climate-action_en (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- European Commission (EC). Climate Action- Kyoto 1st Commitment Period (2008–12). 2025. Available online: HTTPS://CLIMATE.EC.EUROPA.EU/EU-ACTION/INTERNATIONAL-ACTION-CLIMATE-CHANGE/KYOTO-1ST-COMMITMENT-PERIOD-2008-12_EN (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- European Commission (EC). Climate Action: Commission Proposes Ratification of Second Phase of Kyoto Protocol. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_13_1035 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- European Commission (EC). CLIMATE ACTION- KYOTO 2ND COMMITMENT PERIOD (2013–20). 2025. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/international-action-climate-change/kyoto-protocol_en#kyoto-2nd-commitment-period-2013-2020 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- European Commission (EC). Climate Action- About the EU ETS. 2025. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/about-eu-ets_en (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- European Commission (EC). Climate Action- Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming. 2025. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/carbon-removals-and-carbon-farming_en (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- European Council. Paris Agreement on Climate Change. 2025. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/pt/policies/paris-agreement-climate/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- European Council. Climate Change: What the EU is doing. 2025. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/pt/policies/climate-change/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- European Council. Fit for 55. 2025. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/fit-for-55/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- European Parliament. BRIEFING EU Legislation in Progress A Union certification framework for carbon removals European Parliament. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, B. The future Portuguese Voluntary carbon market- the viability of it’s operation. Dissertation within the scope of the Master’s Degree in Legal and Forensic Sciences, University of Coimbra, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ICAP. International Carbon Action Partnership. 2025. Available online: https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/ets/korea-emissions-trading-system-k-ets (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISDA. The Legal Nature of Voluntary Carbon Credits: France, Japan and Singapore. 2022. Available online: https://www.isda.org/a/PlcgE/Legal-Nature-of-Voluntary-Carbon-Credits-France-Japan-and-Singapore.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Kabato, W., Getnet, G. T., Sinore, T., Nemeth, A.,; Molnár, Z. Towards climate-smart agriculture: Strategies for sustainable agricultural production, food security, and greenhouse gas reduction. Agronomy 2025, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakarakos, G., Petropoulos, T., Marinoudi, V., Berruto, R.,; Bochtis, D. Carbon Farming: Bridging Technology Development with Policy Goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil health and carbon management. Food and energy security 2016, 5, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law No 98/2021- Climate Framework Law.

- Lovell, H.C. Governing the carbon offset market. In Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: climate change; 2010; Volume 1, pp. 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Martinho, V. J. P. D., Ramos, T. C. B., Castanheira, N. L., Cunha, C., Ferreira, A. J. D., da Silva Pereira, J. L.,; Carreira, M. D. C. S. Analysing the different interrelationships of soil organic carbon using machine learning approaches: The specific case of Portuguese land. Revista de Ciências Agrárias 2025, 48. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, H., Bey, N., Duin, L., Frelih-Larsen, A., Maya-Drysdale, L., Stewart, R., ...; Zakkour, P. Certification of Carbon Removals. Part 2: A review of carbon removal certification mechanisms and methodologies. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado Voluntário de Carbono (MVC)- Rumo à neutralidade climática. 2025. Available online: https://mvcarbono.pt/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Michaelowa, A., Shishlov, I.,; Brescia, D. Evolution of international carbon markets: lessons for the Paris Agreement. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2019, 10, e613. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelowa, A., Shishlov, I., Hoch, S., Bofill, P.,; Espelage, A. Overview and comparison of existing carbon crediting schemes. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Plano Nacional Energia e Clima 2021-2030 (PNEC 2030) Update/Review,- Portugal. 2024.

- UN. Mechanisms under the Kyoto Protocol. 2025. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process/the-kyoto-protocol/mechanisms (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- UN. Climate Change-The Clean Development Mechanism. 2025. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-kyoto-protocol/mechanisms-under-the-kyoto-protocol/the-clean-development-mechanism.

- UN. Climate Change- Joint implementation. 2025. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process/the-kyoto-protocol/mechanisms/joint-implementation.

- UN. Climate Change-Emissions Trading. 2025. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process/the-kyoto-protocol/mechanisms/emissions-trading.

- Phelan, L., Chapman, P. J.,; Ziv, G. The emerging global agricultural soil carbon market: the case for reconciling farmers’ expectations with the demands of the market. Environmental Development 2024, 49, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2024/3012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2024 establishing a Union certification framework for permanent carbon removals, carbon farming and carbon storage in products.

- RNC2050, 2019-Roteiro para a Neutralidade Carbónica 2050-Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.º 107/2019.

- Ruiting, W., Ahmad, M. S., Jamaludin, J. B., Abd Rahim, N., Wong, S. Y., Rehman, J. U., ...; Assad, M. E. H. A comprehensive bibliometric review of voluntary carbon markets: trends and future directions. Environmental Research Communications 2025, 7, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. United Nations Development Programme,2024—Voluntary Carbon Market Landscape, Opportunities and Challenges for Private Sector Engagement in Nepal.

- Von Unger, M.,; Emmer, I. Carbon market incentives to conserve, restore and enhance soil carbon. Silvestrum and The Nature Conservancy: Arlington, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing. World Bank: Washington, DC, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).