1. Introduction

Rapid advancements in chip manufacturing and AI computational power, central to the Fourth Industrial Revolution, have significantly increased energy demands.Hopf et al.(2022)demonstrated that semiconductor manufacturing is highly energy-intensive, primarily due to the rigorous processes involved, such as high-purity material preparation and the operation of ultra-clean environments. These requirements significantly contribute to the carbon footprint of the technology sector. Similarly, Elgamal et al. (2023)emphasized that AI workloads, particularly those involving the training of large-scale neural networks, are not only computationally demanding but also require extensive cooling infrastructure to maintain system performance, further exacerbating energy consumption.

China’s heavy reliance on fossil fuels, which currently account for over 80% of its energy mix, presents significant challenges in addressing the energy demands of these industries while achieving sustainability goals(SU et al., 2021). This dependency also raises critical concerns regarding energy security, as imported fossil fuels remain a crucial component of the country’s energy supply. To tackle these challenges and align with the global technological revolution, China has adopted an ambitious dual-carbon strategy. This strategy emphasizes a transition from coal-dominated energy systems to renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power. In addition, it promotes carbon trading mechanisms and incentivizes investments in energy-efficient technologies (B. Lin, 2022). These initiatives are essential not only for reducing carbon emissions but also for enhancing China’s competitiveness in the evolving global green technology landscape.

The carbon footprint, carbon sequestration potential, and low-carbon technologies in tea production have become focal points of recent research. L. Liang et al. (2021)identified that the primary greenhouse gas emissions in Chinese tea production are concentrated in processing, fertilizer application, and soil emissions. Life cycle assessments have estimated that the total carbon emissions of the tea industry in 2017 reached 28.75 million tons of CO₂ equivalent, with processing contributing 41%, fertilizer production 31.6%, and soil emissions 26.7%. Furthermore, He et al.(2023) found that the carbon intensity of green tea and organic tea production is notably high, particularly during steaming and drying stages, where aging equipment and energy inefficiency are significant factors. Despite its challenges, organic tea demonstrates a significant reduction in carbon emissions compared to conventional tea. Xu et al. (2019)emphasized that optimized management and technological upgrades could reduce emissions by 49%-65%, although cultivation, processing, and packaging remain the primary emission hotspots throughout the lifecycle.Notably, Tea plantations contribute to carbon emissions while also acting as significant carbon sinks. M. Zhang et al.(2017) estimated that the total carbon storage in China’s tea plantations reached 127.85 Tg in 2010, with soil accounting for 73% and plant biomass 27%. Between 1950 and 2010, the total carbon sequestration increased by 30.6 Tg from plants and 39.0 Tg from soil, showcasing the substantial carbon sequestration potential of tea plantations.

Notably, despite being a non-regulated emissions sector, the tea industry has actively engaged in low-carbon initiatives. This raises a critical research question: why has a sector without mandatory emissions reduction targets voluntarily aligned with carbon neutrality goals, and what mechanisms drive this transformation? To address this, this study systematically examines the drivers and mechanisms behind the tea industry’s voluntary participation in carbon neutrality. By combining CNKI data analysis with other factors, we have constructed a comprehensive stakeholder map of the tea industry,This mapping not only uncovers critical trends in carbon emissions and carbon sequestration research but also provides theoretical foundations and practical guidance for the green transformation of the tea industry.

The contributions of this study are threefold:

1. It reveals the motivations and drivers behind the proactive participation of a non-regulated emissions sector in carbon neutrality.

2. It introduces an integrative framework linking policy, market, and technology to better understand the dynamics of low-carbon agricultural transitions.

3. It offers practical recommendations for enhancing the green competitiveness of the tea industry, while providing replicable frameworks for sustainable development in other agricultural sectors.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 outlines the methodology, detailing the data sources, selection criteria, and analytical framework.

Section 3 presents the findings, focusing on the interplay between policy, market, and technological drivers.

Section 4 discusses the broader implications for low-carbon agricultural transitions. Finally,

Section 5 concludes with the study’s theoretical and practical contributions and provides actionable recommendations for policymakers and stakeholders.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Sources

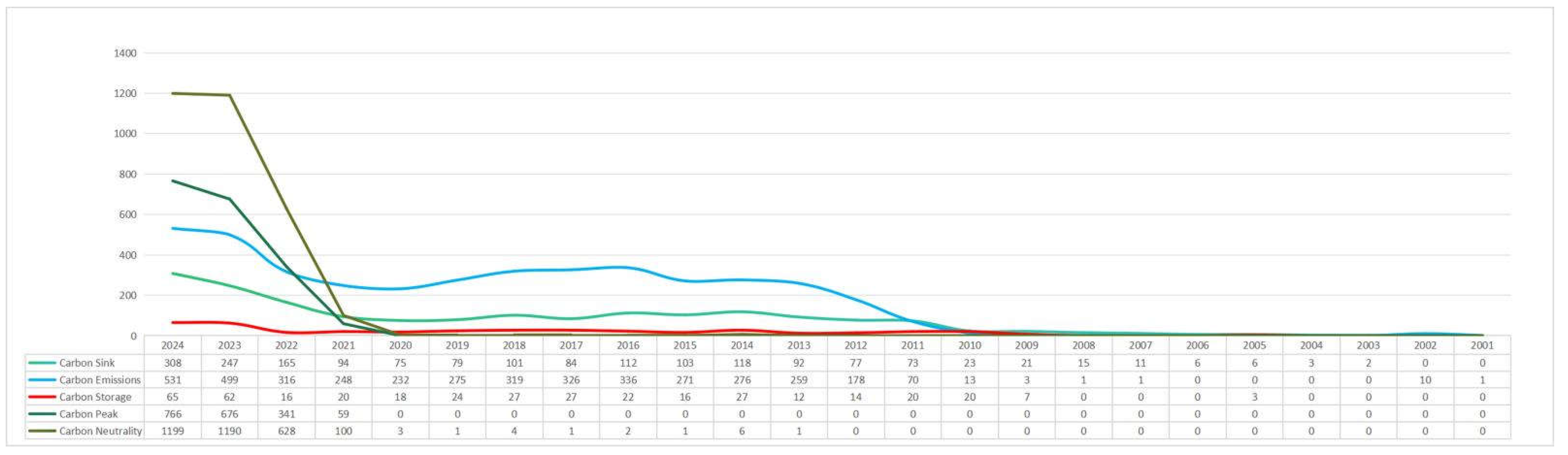

The data for this study were sourced from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database, with a focus on research papers funded by grants. Special attention was given to 11,358 papers published between 2001 and 2024, identified using the keywords "carbon sink," "carbon neutrality," "Carbon Storage ," "carbon peaking," and "carbon emissions." These papers were supported by funding sources, including national-level grants, provincial grants, and university funds. A time series analysis was employed to statistically analyze the number of papers published each year and to identify trends over time. Line charts were created to visually represent the changing trends in the number of publications related to each keyword during the study period (see

Figure 1). Based on these research trends, we then narrowed our focus to the tea industry, exploring its role and potential in advancing the carbon neutrality agenda.

2.2. Classification of Industrial Chain Segments and Stakeholder Identification

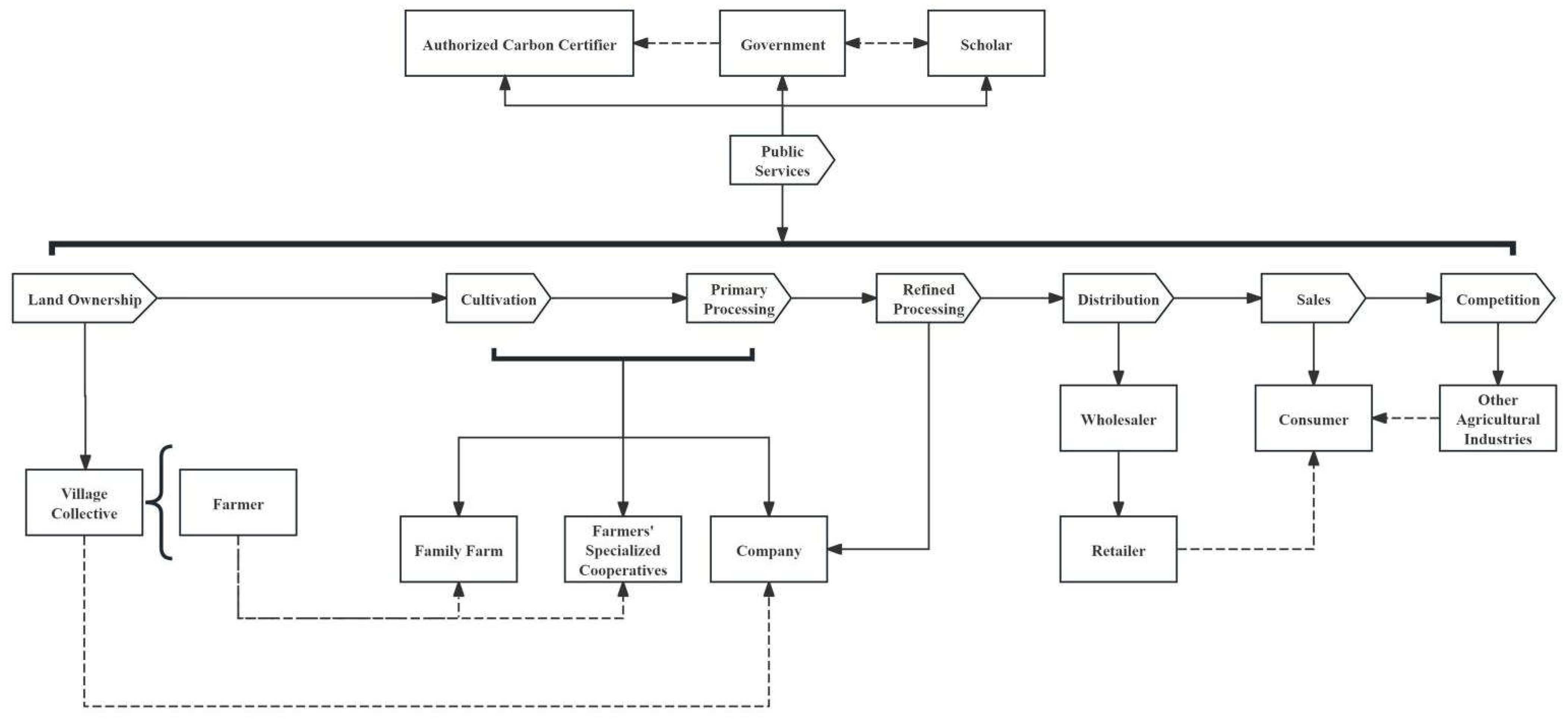

This study utilizes a layered mapping approach to create a stakeholder map, providing a detailed analysis of the various stakeholders involved in China’s tea value chain. The roles and contributions of these stakeholders in carbon emissions and carbon sequestration were identified. The tea value chain was categorized into three sectors—primary, secondary, and tertiary—resulting in key stages such as land use, cultivation, primary processing, refined processing, distribution, consumers, services, and competition (represented as diamonds in

Figure 2). Based on this value chain classification, we further categorized participants, including farmers, collectives, family farms, farmer cooperatives, enterprises, wholesalers, retailers, consumers, government bodies, scholars, and third-party carbon verification agencies (represented as squares in

Figure 2).

2.3. Analysis of the Relationship Between Segments and Stakeholders

2.3.1. Ownership of Rural Land in China

Rural land ownership and distribution in China have undergone several significant reforms, with the most notable being the "Three Rights Separation" policy. This policy, which separates ownership rights, contract rights, and management rights, aims to clarify land property rights, promote the rational use of resources, and advance modern agricultural development. Under this system, the land contract rights are split into contract rights and management rights. The collective retains ownership of rural land, while households hold contract rights, and business entities obtain management rights. Key documents include the"Opinions on Improving the Separation of Rural Land Ownership, Contractual Rights, and Management Rights." (Xinhua News Agency, 2016).

2.3.2. Agricultural Business Entities

Family farm represent a new type of agricultural business entity, characterized by household labor and moderate-scale operations. These farms, as carriers of new professional farmers, embody the agency of farmers while maximizing their enthusiasm and creativity, effectively safeguarding and advancing their interests. Therefore, like traditional smallholder farmers, family farms serve as key units of agricultural operations and contribute to promoting sustainable agricultural development. Farmer cooperatives, on the other hand, are voluntary organizations formed by farmers. These cooperatives can include members from family farms or other farmers, jointly managing agricultural, rural economic, and related activities. Agricultural business entities typically consist of farmers who have acquired land contract rights. Additionally, agribusinesses often seek to obtain land management rights from collectives to further their development. In

Figure 2, solid lines indicate subordinate relationships, while dashed lines represent strong interest-based relationships.

2.4. Classification of Key Elements for Carbon Neutrality

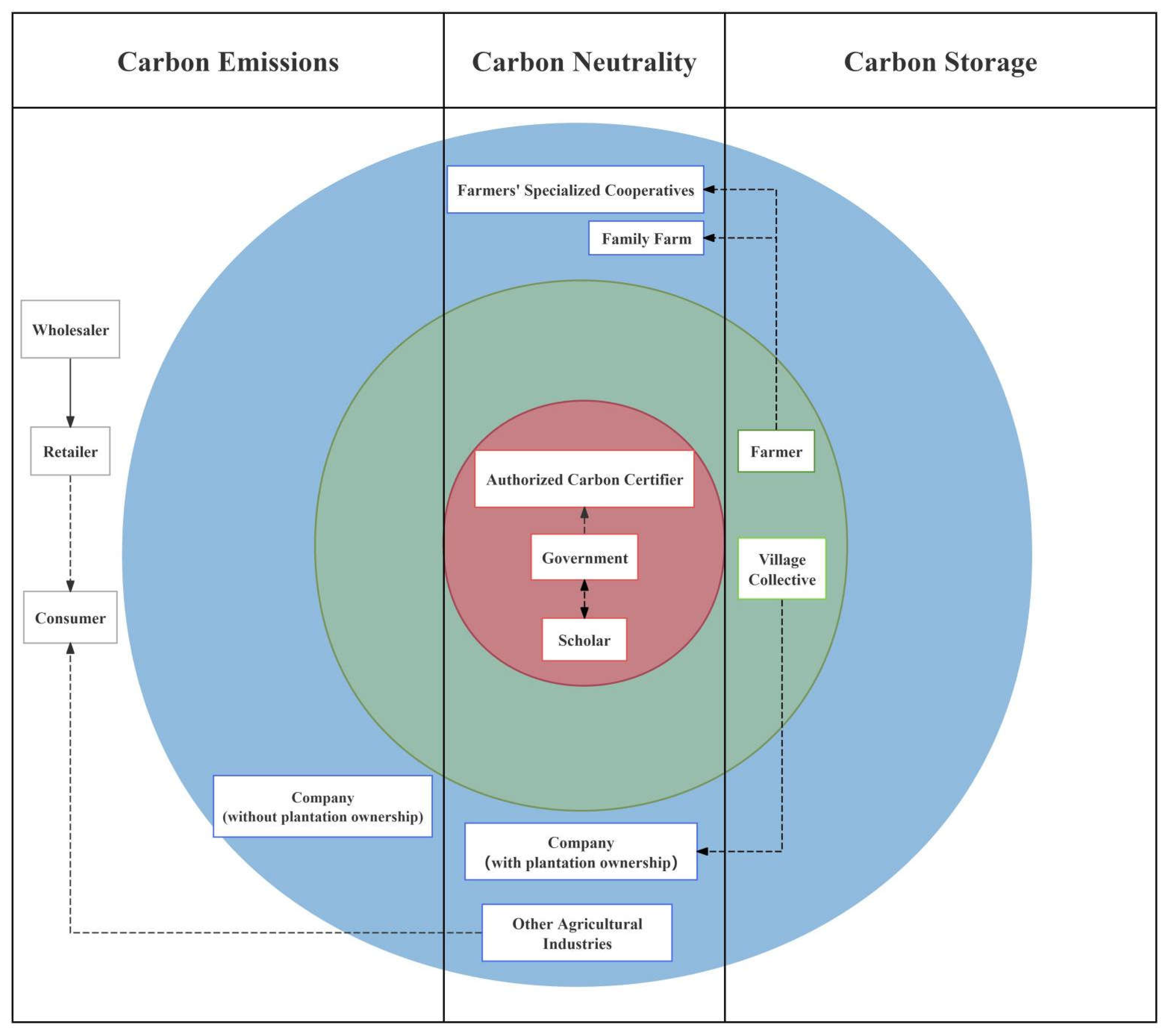

The classification of key elements for carbon neutrality across different stages of the value chain is shown in

Table 1. Carbon neutrality refers to the goal of balancing carbon-related activities, where carbon emissions are offset by carbon sequestration through public services, achieving a net-zero emissions state.

2.5. Stakeholder Mapping

An association matrix was established between industry chain segments and stakeholders to clarify the roles and impacts of various stakeholders across different segments(see

Figure 3).

3. Results

3.1. The Dominant Role of Government and Scholars in the Low-Carbon Transition of the Tea Industry

Across all stages of the tea value chain, key stakeholders such as the government and scholars play a leading role in driving the industry’s low-carbon transition, each according to their respective functions. Through policy guidance, technological innovation, and scientific research, these stakeholders actively promote low-carbon development. Scholars provide crucial support for the government in shaping low-carbon policies, while the government, through funding and policy initiatives, generates a siphoning effect that accelerates the tea industry’s transition. This finding is consistent with the stakeholder analysis presented in the methods section, further validating the collaborative role of policy and academic research in facilitating the low-carbon transition.

3.2. The Advantages of Full-Value-Chain Enterprises in the Low-Carbon Transition

Full-value-chain enterprises have a significant advantage in the low-carbon transition due to the consistency of their equipment and technology. This enables them to efficiently coordinate technological and equipment upgrades across both upstream and downstream segments when implementing low-carbon policies, resulting in more effective carbon reduction. This finding further validates the benefits of integrated value chain operations in achieving low-carbon transition goals.

3.3. Market Impact of Aggressive Low-Carbon Policies on Carbon-Emitting Enterprises

The study reveals that as the mid-term carbon peaking targets approach and low-carbon agricultural policies are progressively implemented, carbon-emitting enterprises without tea plantation management rights are facing severe market pressure under the current socialist market economy. In this policy environment, these companies struggle to balance economic stability and sustainable development, leading to a clear imbalance that threatens their financial health and market competitiveness. This conclusion faithfully reflects the impact of policies and the market economy system on enterprise development, highlighting the practical challenges posed by policy implementation.

3.4. The Self-Balancing Role of the Tea Industry in Carbon Neutrality

The study indicates that the tea industry, as a bilateral carbon neutrality sector, both generates carbon emissions and possesses carbon sequestration capabilities, enabling it to achieve internal carbon neutrality through mutual offsetting. Consequently, after achieving carbon balance within the industry, the tea sector finds it challenging to take on significant external carbon offset responsibilities. However, post-transition to a low-carbon model, the tea industry can still partially compensate for the shortfalls in carbon offset tasks from sectors like forestry and grasslands through its carbon sink potential. Thus, the tea industry holds a unique position within the broader carbon neutrality strategy, playing a supportive role in helping other sectors meet their carbon neutrality targets.

4. Discussion

4.1. Energy Security Strategy Under the "Dual Carbon" Goals

In the context of the accelerating Fourth Industrial Revolution, the rapid advancement of digitalization and intelligent technologies presents new opportunities for nations while imposing greater demands on energy security (CHEN et al., 2024).China must seize this historic opportunity to ensure an unrestricted energy supply, which is not only a strategic choice for enhancing national competitiveness but also a pressing need to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and mitigate external risks(Abbasi et al., 2022). The introduction of China’s "Dual Carbon" goals serves as a key measure to address global climate change(Y. Wang et al., 2021), while simultaneously securing national energy security and laying the foundation for a new clean energy system(F. Zhao et al., 2022).

Currently, China’s energy structure remains dominated by high-carbon fossil fuels, with a relatively low share of clean energy and high external energy dependence, presenting significant risks. The "Dual Carbon" targets will accelerate the development of renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, hydropower, and biomass, gradually reducing dependence on imported fossil fuels and strengthening energy security resilience(Ren & Sovacool, 2015).

By advancing an energy consumption revolution, enhancing energy efficiency, and increasing the share of renewable energy, China aims to provide a stable and sustainable energy foundation for the development of artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Achieving this goal will not only help China gain a competitive edge in the global race for AI technology but will also provide robust energy security for the realization of the "Dual Carbon" goals.

4.2. Advantages of the Tea Industry in Carbon Neutrality

4.2.1. Consistency in Carbon Reduction Across the Full Lifecycle

To achieve synergistic development and maximize industry value, tea industry enterprises have adopted a vertically integrated business model, extending the value chain and forming a shared interest community across upstream and downstream sectors(W. Zhang et al., 2024). In the upstream segment, companies maintain control over raw material quality through direct ownership or cooperative farming. In the midstream, they drive the production process through capital investment and technological innovation. Downstream, they leverage brand marketing and channel advantages to control the sales terminals. Additionally, many enterprises have expanded into related areas such as tea culture tourism and tea house dining, further maximizing industry value. By integrating resources across the value chain and reshaping its value proposition, these businesses create synergistic effects and scale advantages(Cao & Zhang, 2011), enhancing cross-sectoral empowerment and cluster competitiveness. This reflects a strategic intention by industry leaders to construct an integrated value chain.

From a theoretical perspective, the full value chain development led by industry leaders aligns with transaction cost theory. By internalizing uncertainties and opportunistic costs in external transactions, companies can reduce transaction costs and improve overall operational performance. Vertical integration and value chain expansion offer clear advantages over outsourcing and market transactions in terms of resource acquisition, proprietary asset protection, and market power. When the combined returns from each value chain segment exceed the internalization costs, the potential benefits of vertical integration and value chain expansion motivate companies to pursue these strategies(Bresnahan & Levin, 2013).

Full value chain integration helps tea companies implement unified energy-saving and emission-reduction standards, creating synergy across upstream and downstream operations(Bai & Yu, 2024). From tea plantation development, raw material procurement, production, and processing, to storage, logistics, and sales, the entire system can be optimized according to a consistent environmental philosophy and low-carbon technology path. This approach avoids management imbalances and inconsistent policy enforcement that can arise from fragmented operations.

Furthermore, the coordination of technical upgrades and process improvements across the value chain is more efficient, increasing overall energy savings and emission reduction. For full value chain enterprises, the opportunity cost of introducing advanced technologies in key areas, such as mechanized harvesting, clean production, green packaging, and logistics optimization, is lower(Yu et al., 2021). In contrast, fragmented operations often face higher transformation costs.

Additionally, integrated enterprises can use information systems and data management platforms to dynamically monitor resource consumption and energy emissions across the value chain, identifying weak links for continuous improvement. This comprehensive approach enables them to contribute to carbon footprint reduction at every stage of the value chain, achieving the maximum possible energy savings and emission reduction benefits.

4.2.2. The Advantage of Monoculture in Tea Plantations

In China, monoculture is the main planting pattern of tea plantations(X. Lei et al., 2022). Due to the uniformity in crop species and the relatively simple vegetation structure, the biological characteristics and growth patterns within the plots are consistent. This reduces the workload and sampling intensity required during remote sensing interpretation and ground surveys(Fassnacht et al., 2016). In constructing biomass models, only a single species needs to be considered, which eliminates the complexity introduced by intra- and interspecies variability typically seen in diverse ecosystems. Consequently, this simplifies the model, and the biomass component equations can be streamlined, minimizing the use of conversion coefficients for biomass fractions.

From an algorithmic optimization perspective, the relatively uniform canopy height and crown width of tea plantations facilitate data processing using optical and radar remote sensing imagery. In contrast, biomass estimation for natural forests often requires higher resolution imagery and more complex stratified fitting algorithms. Additionally, in remote sensing classification, the single-crop system reduces the likelihood of classification errors due to mixed species(F.-C. Lin et al., 2024). This makes tea plantations highly advantageous in terms of simplifying the development of carbon biomass estimation models, parameter calibration, and data acquisition, ultimately improving both the efficiency and accuracy of carbon stock measurements.

Tea is not only an economically important crop in China, but it also plays a critical ecological role. As a perennial plant with vast cultivation areas across the country, tea plants have considerable carbon storage potential(D. Wang et al., 2023). Throughout their lifecycle, tea trees continuously absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide via photosynthesis, sequestering it in their biomass and soil, contributing significantly to carbon sequestration. This long-term carbon storage capacity is increasingly recognized in the strategic framework for achieving China’s "dual carbon" (carbon peak and carbon neutrality) goals. The tea industry’s carbon sink capacity enhances agricultural carbon sequestration potential and helps improve the broader ecological environment. Furthermore, tea plantations contribute to soil conservation and reduce soil carbon emissions, thereby serving multiple roles in agricultural carbon sequestration, addressing climate change, and promoting sustainable agricultural development.

In summary, compared to complex, multi-species natural forests, monoculture tea plantations offer significant advantages in constructing carbon biomass estimation models and data collection processes due to their simplified structure. However, in practice, it is essential to incorporate multiple data sources and choose appropriate algorithm models based on specific conditions to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results.

4.2.3. Comprehensive Disciplinary System

The disciplinary framework of Tea Science integrates foundational fields such as agricultural science, food science, and chemical analysis, while also incorporating the social sciences and humanities, including history, economics, and culture. This interdisciplinary, comprehensive research network provides robust support for technological innovation and problem-solving in the low-carbon development of the tea industry(Lai & Shi, 2020).

In the context of low-carbon transformation, the Tea Science framework plays a pivotal role in advancing research in sustainable agriculture, energy-efficient processing technologies, and eco-friendly packaging. For instance, enhancing the carbon sequestration capacity of tea plantations(S. Li et al., 2011), optimizing energy use and emissions reduction during production, and conducting full life-cycle assessments of the carbon footprint are all efforts guided by this disciplinary system(C. Zhang et al., 2023). This academic foundation not only equips companies with the technological solutions needed for a low-carbon transition but also supports the industry’s long-term sustainable development in the pursuit of carbon neutrality.

Moreover, the inclusion of tea culture and consumer behavior studies within the disciplinary framework offers valuable insights into market trends and consumer demand for low-carbon products. This understanding provides strong market support for companies to promote green products and implement low-carbon practices. With the continuous impetus provided by this academic system, the tea industry can sustain innovation in its low-carbon transformation, gaining a strategic advantage in the competitive landscape. Compared to other agricultural sectors, this advantage is particularly pronounced.

4.3. Multiple Benefits of the Tea Industry’s Participation in Carbon Neutrality

4.3.1. Promoting Industrial Upgrading and Technological Innovation

The integration of carbon neutrality into the tea industry represents a profound application of sustainable development principles within traditional agriculture. Its core objective lies in realizing ecological value through comprehensive emissions reduction strategies and carbon management measures, thereby driving the industry’s transformation toward a new level of productivity(Hou et al., 2024). This shift is not only motivated by the pressing need for environmental protection but also driven by the internal forces of economic transformation and upgrading. The establishment of carbon neutrality goals adds strategic significance to emission reduction efforts, offering tea enterprises a new development pathway to enhance efficiency through comprehensive carbon management. This simultaneously fosters innovation in production processes and the adoption of low-carbon technologies, promoting efficient resource utilization, cost reduction, and achieving a win-win situation for both the economy and the environment.

In this process, technological innovation emerges as a key driver. The adoption of smart agricultural technologies not only amplifies emission reduction effects but also improves product quality and production efficiency, positioning tea enterprises to build green brands in the global market and tap into broader development opportunities(Javaid et al., 2022). Of particular importance is the fact that this transformation directly contributes to environmental protection and restoration in ecologically sensitive areas(Guo et al., 2021). Through mechanisms such as carbon sequestration projects, the ecological service value can be quantified and realized, providing economic incentives for ecological preservation and fostering synergistic growth in both ecological and economic benefits(Langpap & Kim, 2010).

As a key pillar of agricultural economies, the tea industry’s active participation in carbon neutrality is a vital pathway to achieving sustainable development and advancing toward the goal of new productivity. By engaging in carbon neutrality initiatives, tea enterprises can comprehensively assess their carbon footprint, establish long-term emission reduction strategies, and stay attuned to policy developments, gaining valuable experience in carbon management. This enables them to better navigate future environmental policy changes and market demands. At the same time, such participation compels tea enterprises to adopt efficient, low-carbon production methods and technologies, driving industry-wide upgrades and innovation. Moreover, it promotes coordinated emissions reductions across the entire supply chain, building a sustainable green industry system(Zou et al., 2023).

However, it is important to recognize that achieving carbon neutrality is a systemic and long-term endeavor. It requires tea enterprises to possess comprehensive knowledge of carbon emissions management and strategic planning capabilities. Thus, companies should strengthen their carbon management capacity, develop long-term carbon neutrality roadmaps, and collaborate with professional organizations to ensure that the transition to carbon neutrality is pursued scientifically and effectively, thereby securing sustainable development.

4.3.2. Risk Management and Future Adaptability

As global efforts to reduce emissions intensify, carbon emission regulations are becoming increasingly stringent(X. Zhao et al., 2020), with a growing risk that non-regulated industries may soon be incorporated into carbon control frameworks(Xia et al., 2024). By actively participating in carbon neutrality initiatives, tea enterprises can better understand and anticipate future policy shifts, mitigating potential compliance costs and risks, and achieving sustainable development. Proactive involvement in the low-carbon transition allows companies to become familiar with carbon emissions trading rules and procedures, understand emissions accounting methods and standards, and stay informed of the evolving carbon emissions policy landscape. This enables tea enterprises to develop carbon neutrality strategies in advance, implement emission reduction measures systematically, and avoid compliance risks stemming from policy changes.

Through carbon trading, tea companies can accumulate valuable experience in carbon management, including accounting for their own emissions, establishing emission reduction plans, optimizing production processes, and ultimately lowering carbon emission costs(Hua et al., 2022). Additionally, by engaging with other stakeholders involved in carbon neutrality, tea enterprises can share experiences and learn advanced carbon management methods, continuously enhancing their carbon management capabilities.

Furthermore, carbon neutrality initiatives provide tea enterprises with a platform to engage in dialogue with government bodies and industry associations. By participating in carbon neutrality activities, companies gain insights into government policies on carbon emissions management and exchange knowledge with industry peers regarding emission reduction strategies(Bui & de Villiers, 2017). This active participation helps tea enterprises stay updated on policy trends and access potential policy support, ensuring they are well-positioned to navigate future regulatory landscapes.

4.3.3. Expanding Financing Channels

The tea industry’s involvement in carbon neutrality has essentially established a bridge between environmental protection and financial innovation, creating new avenues for tea enterprises to secure funding(F. Liang, 2024). By reducing carbon emissions, tea companies not only have the opportunity to trade carbon credits for direct economic returns but can also leverage their green credentials to attract a wider range of green financial products and investments, such as green bonds and credit facilities, to fund sustainable projects. This process significantly enhances the companies’ financing capabilities and market competitiveness, elevates brand value, and meets the growing demand for green consumer products.

Additionally, government policies and international carbon trading partnerships provide further financial and technical support, accelerating the industry’s green transformation and global expansion(Tanveer et al., 2024). In the long run, the integration of the tea industry with carbon neutrality not only addresses financing challenges but also guides the sector toward a high-efficiency, low-carbon, and sustainable development path. It serves as a model for green transformation in other agricultural sectors, collectively advancing global sustainable development.

4.4. Enhancing Brand Image and Market Competitiveness

The carbon labels obtained through carbon neutrality efforts not only strengthen the brand image of tea enterprises but also serve as essential credentials for gaining access to premium markets and global supply chains(Wolfe et al., 2012). As international markets raise their environmental standards, green credentials are increasingly becoming key differentiators for tea companies, enabling them to stand out from competitors and boost their market competitiveness. Tea companies with green labels are more attractive to partners with stringent environmental requirements in their supply chains. Thus, green certification signifies more than just brand enhancement—it is an integral part of a company’s long-term sustainability strategy. It lays a solid foundation for continued competitiveness in the evolving low-carbon economy, ensuring that the enterprise is well-positioned for future growth.

4.5. Disadvantages of Tea Industry Participation in Carbon Neutrality

4.5.1. Radical Local Policies Forcing Enterprises into a Low-Carbon Transition

Radical local government policies are largely influenced by the national push for carbon neutrality and the pressures of local performance evaluations(Davidson et al., 2021). On the one hand, the central government has set a clear timeline to achieve the "3060" carbon neutrality targets, prompting local governments to respond swiftly in an effort to deliver quick and significant results. To excel in environmental performance assessments, some local governments have adopted more aggressive measures, mandating industries to accelerate green technology upgrades. On the other hand, the economic structure, development levels, and resource conditions vary across regions, leading certain areas to implement more forceful low-carbon strategies to facilitate rapid transformation(Y. Lei et al., 2024).

However, such radical policies pose significant challenges to the tea industry, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The rapid implementation of green transformation policies forces enterprises to undertake large-scale technological upgrades and shift production models within a short timeframe, placing considerable financial and technical burdens on businesses. SMEs, with their limited resources, struggle to bear the high costs of this transition, which weakens the industry’s overall synergy, negatively impacting production efficiency and product quality(X. Chen et al., 2024). Furthermore, market mechanisms have not fully adapted to the low-carbon transition, and consumers’ awareness and acceptance of low-carbon products remain limited, creating a mismatch between supply and demand(Q. Li et al., 2017). This hinders businesses from recovering their costs through the market, thereby threatening the sustainability of their operations.

Moreover, the immaturity of carbon neutrality mechanisms, including fluctuating carbon prices, exacerbates market risks for tea enterprises. Policymaking often lacks foresight and scientific rigor, and policy instability increases uncertainty for businesses(Ji et al., 2021). For those that have already made substantial investments in low-carbon technology, frequent policy adjustments may result in significant financial losses. There are also barriers to technology transfer and knowledge dissemination, as many tea farmers and small business owners lack the technical expertise needed for effective low-carbon technology adoption(Kennedy & Basu, 2013). In addition, the low-carbon transition can have negative repercussions on local employment, income distribution, and social stability, potentially exacerbating social tensions and causing unforeseen ecological problems.

To ensure the sustainability of the tea industry’s low-carbon transition, local aggressive policies must comprehensively account for industrial restructuring, market adaptation, policy stability and scientific rigor, the effectiveness of technology transfer, and the broader socio-environmental impacts. Systematic research and scientific planning are essential to guarantee a successful and sustainable low-carbon transformation for the tea industry.

4.5.2. Imbalanced Industrial Structure

Under the impetus of carbon neutrality policies, companies often allocate significant resources to upgrading environmental technologies and renewing equipment in an effort to achieve rapid reductions in carbon emissions. However, this concentration of resources often leads to a lag in the development of other critical areas within the industry, exacerbating the problem of imbalanced resource allocation. In their pursuit of emission reductions, companies may overlook investments in product innovation, market expansion, and brand building, which in turn affects their ability to remain competitive in an ever-evolving market environment(H. Li et al., 2024). This imbalance is especially pronounced among small and medium-sized tea enterprises, which, due to limited financial and technical resources, struggle to find a reasonable balance between carbon reduction efforts and overall business development(Eleftheriadis & Anagnostopoulou, 2024; Martins et al., 2022). As a result, the industry’s collaborative efficiency weakens, and both production efficiency and product quality are negatively impacted.

At the industrial chain level, prioritizing carbon reduction strategies can lead to decreased focus on collaboration and technical integration across upstream and downstream sectors(Eleftheriadis & Anagnostopoulou, 2024). With resources and attention concentrated on short-term emission reduction targets, companies may neglect collaborative support for upstream and downstream enterprises in areas such as technology development and innovative applications. This limits the tea industry’s overall connectivity and capacity for innovation, weakening its competitiveness. In the long run, excessive emphasis on short-term emission reduction goals may distort the industrial structure, diminishing the sector’s ability to respond to external challenges such as market fluctuations and shifting consumer demands(Quintás et al., 2018), thus affecting its long-term sustainability.

Moreover, the low-carbon transition may have complex, long-term impacts on the ecological environment and social stability(Y. Zhao et al., 2022). As a labor-intensive industry, the tea sector’s overemphasis on technological modifications and equipment upgrades could alter employment structures, potentially affecting local social stability(Luo et al., 2023). In addition, environmental protection measures that have not been thoroughly scientifically assessed could have adverse effects on the local ecology. For instance, the environmental benefits of certain technological upgrades may not be immediately apparent, and could even introduce new environmental challenges(Söderholm, 2020).

Therefore, to avoid the imbalanced resource allocation caused by carbon neutrality policies, enterprises should find a scientifically sound balance between carbon reduction goals and the overall sustainable development of the industry. By strengthening support for technological innovation, market development, and upstream and downstream collaboration, the tea industry can achieve carbon reduction while maintaining its long-term competitiveness and ecological sustainability.

4.5.3. Intensified Resource Competition Within Agricultural Sectors in Early Policy Stages

As the tea industry actively engages in carbon trading and carbon neutrality mechanisms, other agricultural sectors are also seeking to benefit from carbon sequestration and trading mechanisms to gain additional revenue and market recognition(X. Chen et al., 2021). Although the original intent of these policies is to promote green development across various agricultural sectors, in practice, competition for limited resources between different agricultural industries has intensified. This competition is particularly pronounced in the early stages of policy implementation, where core resources such as land, water, and labor become key points of contention(D. Zhao et al., 2019).

Tea plantation operators prioritize land use and management strategies that can enhance carbon sequestration benefits, such as optimizing vegetation cover and establishing ecological function zones. While this carbon sequestration-focused strategy significantly improves carbon reduction outcomes, it can also lead to imbalanced resource allocation. Prime farmland, water resources, and agricultural labor increasingly concentrate in tea industry’s carbon neutrality projects, leaving other agricultural sectors facing greater challenges in securing resources, which in turn negatively impacts their productivity and economic viability.

More critically, the competition spurred by carbon neutrality policies has redefined the priority areas for agricultural development(Wei et al., 2022). Driven by the goal of maximizing carbon sequestration benefits, the tea industry rapidly adjusts its strategy, diverting resources toward carbon reduction objectives. However, this singular focus, while potentially accelerating short-term carbon neutrality targets, also heightens the risk of structural imbalance within the industry, ignoring the need for agricultural diversity and sustainable development. As resource allocation dynamics shift, the position of traditional agricultural sectors in policy support weakens, further intensifying the scarcity of resources and adding pressure on agricultural producers’ management and survival, especially in resource-limited regions. This poses a greater threat to the overall ecological balance and social stability of agriculture(M. Chen et al., 2022).

Therefore, while advancing carbon neutrality, the tea industry must remain sensitive to the fairness of early-stage resource distribution, avoiding excessive concentration of limited policies and funding in one sector, which would exacerbate resource competition within the agricultural industry. A balanced approach between carbon reduction goals and the needs of traditional agriculture is crucial for ensuring broader, sustainable development within the agricultural sector during the low-carbon transition.

5. Conclusion

China’s push for a carbon neutrality strategy is fundamentally driven by the need to address the energy transformation prompted by the Fourth Industrial Revolution and to ensure energy security. Against this backdrop, the tea industry, with its ecological and supply chain characteristics, can effectively support the nation’s energy transition and carbon neutrality goals. Its unique industrial model not only offers advantages in carbon reduction but also enhances competitiveness and fosters technological innovation, thereby promoting the green transformation of the industry.

However, the tea industry faces numerous challenges in its proactive participation in the carbon neutrality process, particularly uncertainties arising from local government policies, structural imbalances in resource allocation, and intensified competition within the agricultural sector. These issues call for close collaboration between policymakers and industry stakeholders to drive more coordinated and sustainable development strategies.

In the future, only through scientifically sound policy design that promotes balanced development and rational resource allocation within the industry can the tea industry achieve long-term upgrades and sustained growth while contributing to the nation’s carbon neutrality and green development goals.

References

- Hopf, A.; Ismail, A.; Ehm, H.; Schneider, D.; Reinhart, G. Energy-Efficient Semiconductor Manufacturing: Establishing an Ecological Operating Curve. 2022 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC) 2022, 3453–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgamal, M.; Carmean, D.; Ansari, E.; Zed, O.; Peri, R.; Manne, S.; Gupta, U.; Wei, G.-Y.; Brooks, D.; Hills, G.; Wu, C.-J. Carbon-Efficient Design Optimization for Computing Systems. Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Sustainable Computer Systems 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SU; J; LIANG; Y; DING; L; ZHANG; G; LIU; H Research on China’s Energy Development Strategy under Carbon Neutrality. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Chinese Version) 2021, 36, 1001–1009. [CrossRef]

- Lin, B. China’s High-Quality Economic Growth in the Process of Carbon Neutrality. China Finance and Economic Review 2022, 11, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Ridoutt, B.G.; Wang, L.; Xie, B.; Li, M.; Li, Z. China’s Tea Industry: Net Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Mitigation Potential. Agriculture 2021, 11, Article 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, Y.; Zong, S.; Li, K.; Han, X.; Zhao, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Carbon Footprint of Green Tea Produced by Smallholder Farmers in Shaanxi Province of China. Agronomy 2023, 13, Article 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Hu, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Knudsen, M.T. Carbon footprint and primary energy demand of organic tea in China using a life cycle assessment approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 233, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Fan, D.; Zhu, Q.; Pan, Z.; Fan, K.; Wang, X. Temporal Evolution of Carbon Storage in Chinese Tea Plantations from 1950 to 2010. Pedosphere 2017, 27, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua News Agency. Opinions on Improving the Separation of Rural Land Ownership, Contractual Rights, and Management Rights. Gazette of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, /: https, 2016.

- CHEN; X; CAO; L; CHEN; J; ZHANG; J; CAO; W; WANG; Y Development demand, power energy consumption and green and low-carbon transition for computing power in China. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Chinese Version) 2024, 39, 528–539 https://bulletinofcasresearchcommonsorg/journal/vol39/iss3/10/.

- Abbasi, K.R.; Shahbaz, M.; Zhang, J.; Irfan, M.; Alvarado, R. Analyze the environmental sustainability factors of China: The role of fossil fuel energy and renewable energy. Renewable Energy 2022, 187, 390–402 https://wwwsciencedirectcom/science/article/pii/S0960148122000763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, C.; Chen, X.; Jia, L.; Guo, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H. Carbon peak and carbon neutrality in China: Goals, implementation path and prospects. China Geology 2021, 4, 720–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Bai, F.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z. A Review on Renewable Energy Transition under China’s Carbon Neutrality Target. Sustainability 2022, 14, Article 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Sovacool, B.K. Prioritizing low-carbon energy sources to enhance China’s energy security. Energy Conversion and Management 2015, 92, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, M.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Fan, S. Low-Carbon Ecological Tea: The Key to Transforming the Tea Industry towards Sustainability. Agriculture 2024, 14, 722. https://www.mdpi.com/2077–0472/14/5/722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, Q. Supply chain collaboration: Impact on collaborative advantage and firm performance. Journal of Operations Management 2011, 29, 163–180 https://wwwsciencedirectcom/science/article/pii/S0272696310001075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnahan, T.; Levin, J. 21. Vertical Integration Market Structure. In The Handbook of Organizational Economics; Gibbons, R., Roberts, J., Eds.; Princeton University Press: 2013; pp. 853–890. [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yu, X. The Impact of Global Value Chain Embedment on Energy Conservation and Emissions Reduction:Theory and Empirical Evidence. China Finance and Economic Review 2024, 13, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, J.Z.; Cao, Y.; Kazancoglu, Y. Intelligent transformation of the manufacturing industry for Industry 4.0: Seizing financial benefits from supply chain relationship capital through enterprise green management. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2021, 172, 120999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Wang, T.; Yang, B.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zou, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, X.; Fang, W.; Lei, X.; Wang, T.; Yang, B.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zou, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, X.; Fang, W. Progress and perspective on intercropping patterns in tea plantations. Beverage Plant Research 2022, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, F.E.; Latifi, H.; Stereńczak, K.; Modzelewska, A.; Lefsky, M.; Waser, L.T.; Straub, C.; Ghosh, A. Review of studies on tree species classification from remotely sensed data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 186, 64–87 https://wwwsciencedirectcom/science/article/pii/S0034425716303169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.-C.; Shiu, Y.-S.; Wang, P.-J.; Wang, U.-H.; Lai, J.-S.; Chuang, Y.-C. A model for forest type identification and forest regeneration monitoring based on deep learning and hyperspectral imagery. Ecological Informatics 2024, 80, 102507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wu, B.S.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Hou, J.; Cao, R.; Yang, W. Soil organic carbon stock in China’s tea plantations and their great potential of carbon sequestration. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 421, 138485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Shi, Q. Chapter 7—Green low-carbon technology innovations. In Innovation Strategies in Environmental Science; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier: 2020; pp. 209–253. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, X.; Xue, H.; Gu, B.; Cheng, H.; Zeng, J.; Peng, C.; Ge, Y.; Chang, J. Quantifying carbon storage for tea plantations in China. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 2011, 141, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ye, X.; Wu, X.; Yang, X. Carbon footprint of black tea products under different technological routes and its influencing factors. Frontiers in Earth Science 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y. Can digital economy truly improve agricultural ecological transformation? New insights from China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Enhancing smart farming through the applications of Agriculture 4.0 technologies. International Journal of Intelligent Networks 2022, 3, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yu, Q.; Pei, Y.; Wang, G.; Yue, D. Optimization of landscape spatial structure aiming at achieving carbon neutrality in desert and mining areas. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 322, 129156 https://wwwsciencedirectcom/science/article/pii/S0959652621033424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langpap, C.; Kim, T. Literature review: An economic analysis of incentives for carbon sequestration on nonindustrial private forests (NIPFs). Alig, RJ, Tech. Coord. Economic Modeling of Effects of Climate Change on the Forest Sector and Mitigation Options: A Compendium of Briefing Papers. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNWGTR-833. Portland, OR: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, /: https, 2376. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, C.; Wu, S.; Yang, Z.; Pan, S.; Wang, G.; Jiang, X.; Guan, M.; Yu, C.; Yu, Z.; Shen, Y. Progress, challenge and significance of building a carbon industry system in the context of carbon neutrality strategy. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2023, 50, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, C.; Sun, C.; Yang, M. Does stringent environmental regulation lead to a carbon haven effect? Evidence from carbon-intensive industries in China. Energy Economics 2020, 86, 104631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Guo, H.; Xu, S.; Pan, C. Environmental regulations and agricultural carbon emissions efficiency: Evidence from rural China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Zhu, D.; Jia, Y. Research on the Policy Effect and Mechanism of Carbon Emission Trading on the Total Factor Productivity of Agricultural Enterprises. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, Article 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, B.; de Villiers, C. Carbon emissions management control systems: Field study evidence. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 166, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F. The Impact of Financial Innovation on Environmental Protection:Literature Review and Case Study. Finance & Economics 2024, 1, Article 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, U.; Ishaq, S.; Hoang, T.G. Enhancing Carbon Trading Mechanisms through Innovative Collaboration: Case Studies from Developing Nations. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 144122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.; Baddeley, S.; Cheng, P. Trade policy implications of carbon labels on food. Estey Centre Journal of International Law and Trade Policy 2012, 13, 59–93https://papersssrncom/sol3/paperscfm. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, M.; Karplus, V.J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X. Policies and Institutions to Support Carbon Neutrality in China by 2060. Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yin, Z.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gong, J.; Cai, B.; Cai, C.; Chai, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, R.; Chen, S.; Chen, W.; Cheng, J.; Chi, X.; Dai, H.; Feng, X.; Geng, G.; Hu, J.; Hu, S.; … He, K. The 2022 report of synergetic roadmap on carbon neutrality and clean air for China: Accelerating transition in key sectors. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2024, 19, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Gao, Y. Can urban low-carbon transitions promote enterprise digital transformation? Finance Research Letters. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Long, R.; Chen, H. Empirical study of the willingness of consumers to purchase low-carbon products by considering carbon labels: A case study. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 161, 1237–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.-J.; Hu, Y.-J.; Tang, B.-J.; Qu, S. Price drivers in the carbon emissions trading scheme: Evidence from Chinese emissions trading scheme pilots. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 278, 123469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.; Basu, B. Overcoming barriers to low carbon technology transfer and deployment: An exploration of the impact of projects in developing and emerging economies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 26, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Su, Y.; Ding, C.J.; Tian, G.G.; Wu, Z. Unveiling the green innovation paradox: Exploring the impact of carbon emission reduction on corporate green technology innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 207, 123562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, I.; Anagnostopoulou, E. Developing a Tool for Calculating the Carbon Footprint in SMEs. Sustainability 2024, 16, Article 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Branco, M.C.; Melo, P.N.; Machado, C. Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, Article 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintás, M.A.; Martínez-Senra, A.I.; Sartal, A. The Role of SMEs’ Green Business Models in the Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy: Differences in Their Design and Degree of Adoption Stemming from Business Size. Sustainability 2018, 10, Article 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, M.; Wang, C. Adapting Tea Production to Climate Change under Rapid Economic Development in China from 1987 to 2017. Agronomy 2022, 12, Article 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderholm, P. The green economy transition: The challenges of technological change for sustainability. Sustainable Earth 2020, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ma, C.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, M.; Cai, Y.; Su, D.; Muneer, M.A.; Guo, M.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Hou, Y.; Cong, W.; Guo, J.; Ma, W.; Zhang, W.; Cui, Z.; Wu, L.; … Zhang, F. Identifying the main crops and key factors determining the carbon footprint of crop production in China 2021, 2001–2018. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hubacek, K.; Feng, K.; Sun, L.; Liu, J. Explaining virtual water trade: A spatial-temporal analysis of the comparative advantage of land, labor and water in China. Water Research 2019, 153, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-M.; Chen, K.; Kang, J.-N.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.-Y.; Zhang, X. Policy and Management of Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality: A Literature Review. Engineering 2022, 14, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, S.; Forsell, N. Toward carbon neutrality before 2060: Trajectory and technical mitigation potential of non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions from Chinese agriculture. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 368, 133186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).