Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenotypic Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile

2.2. Genome Features and Taxonomy

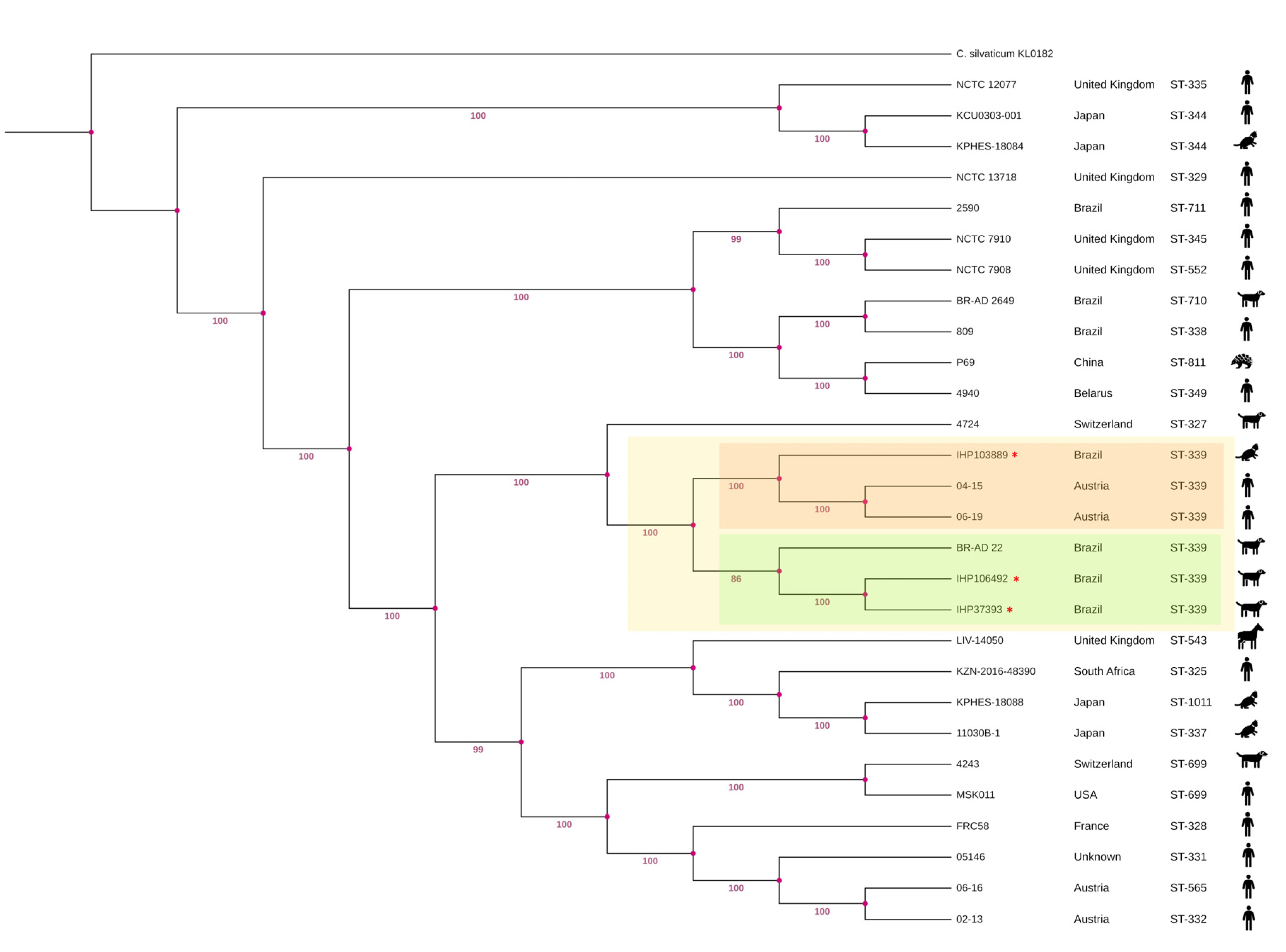

2.3. Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis

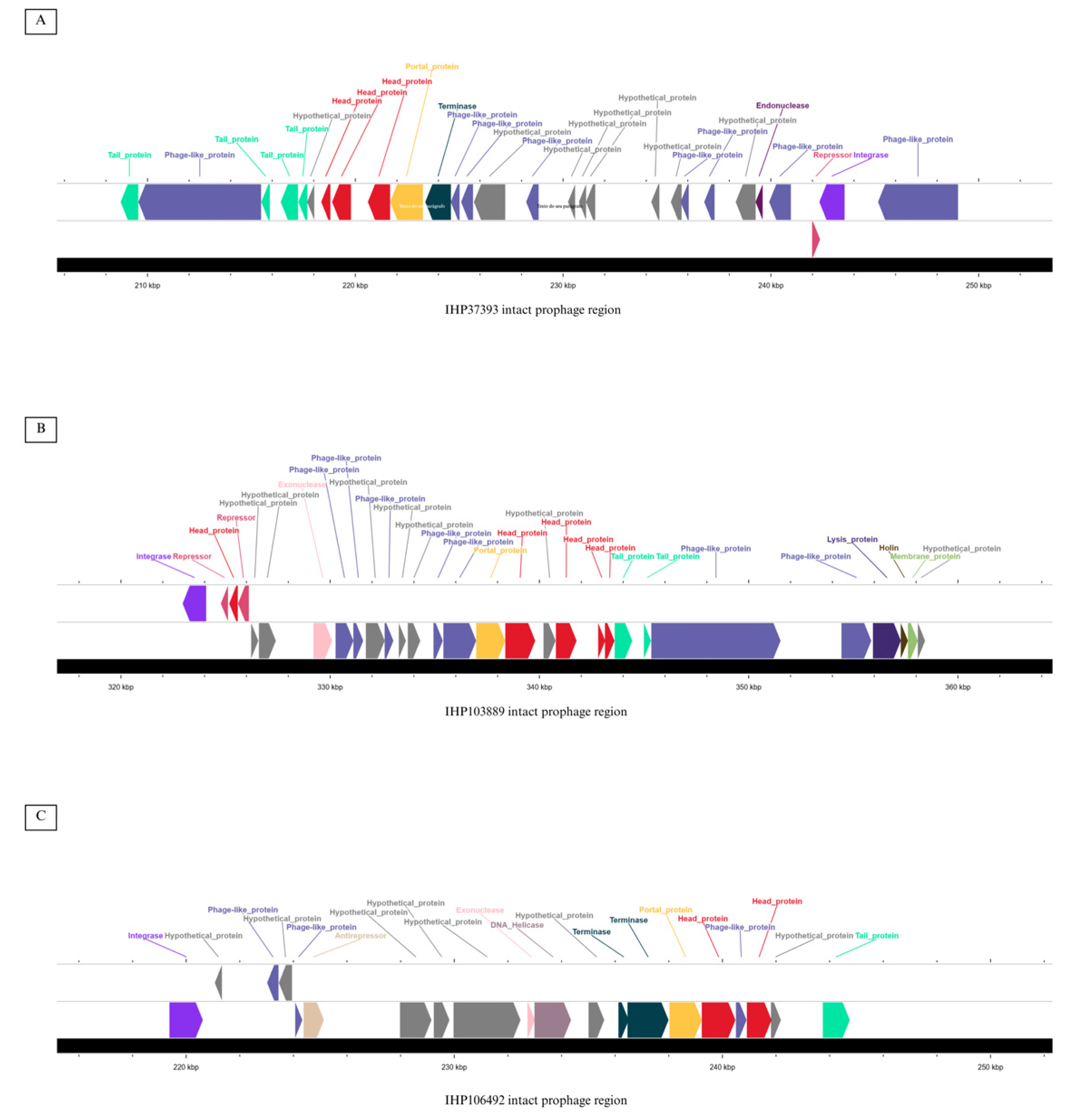

2.4. Prediction of Mobile Genetic Elements and CRISPR-Cas Systems

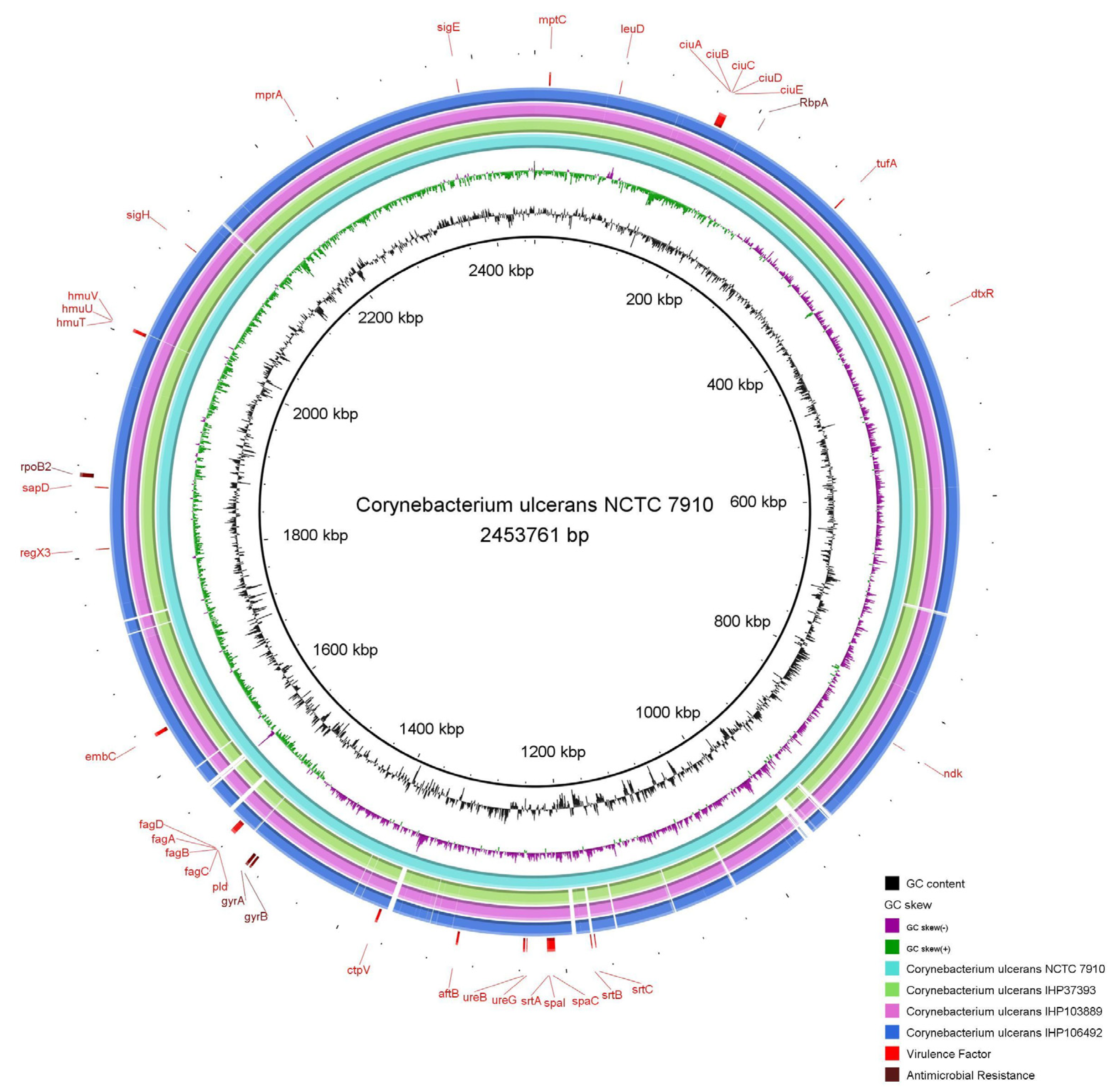

2.5. Identification of Genes Encoding Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Factors

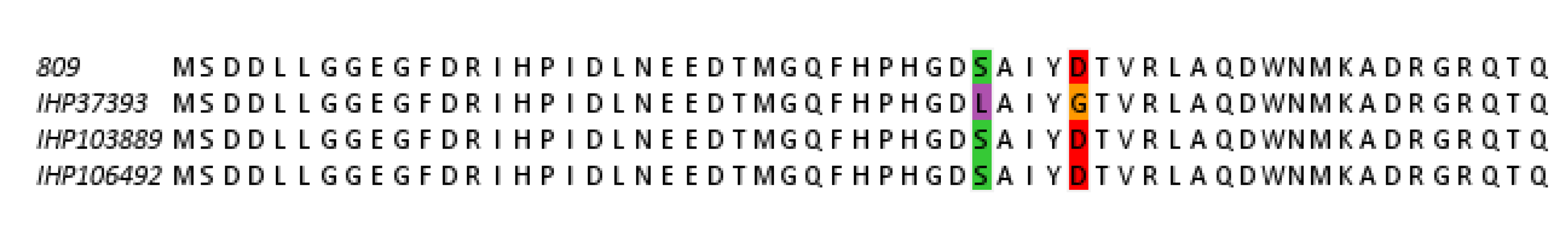

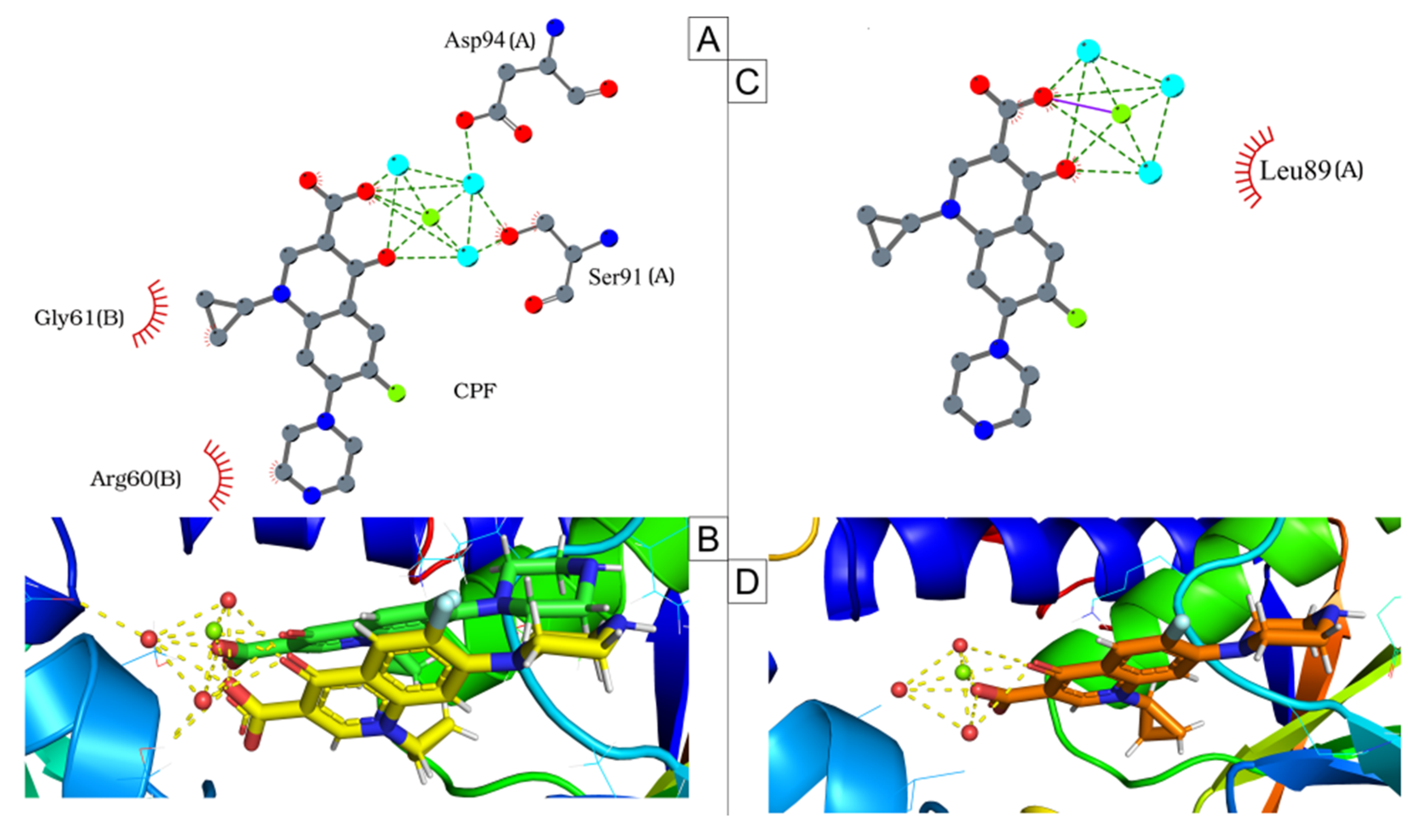

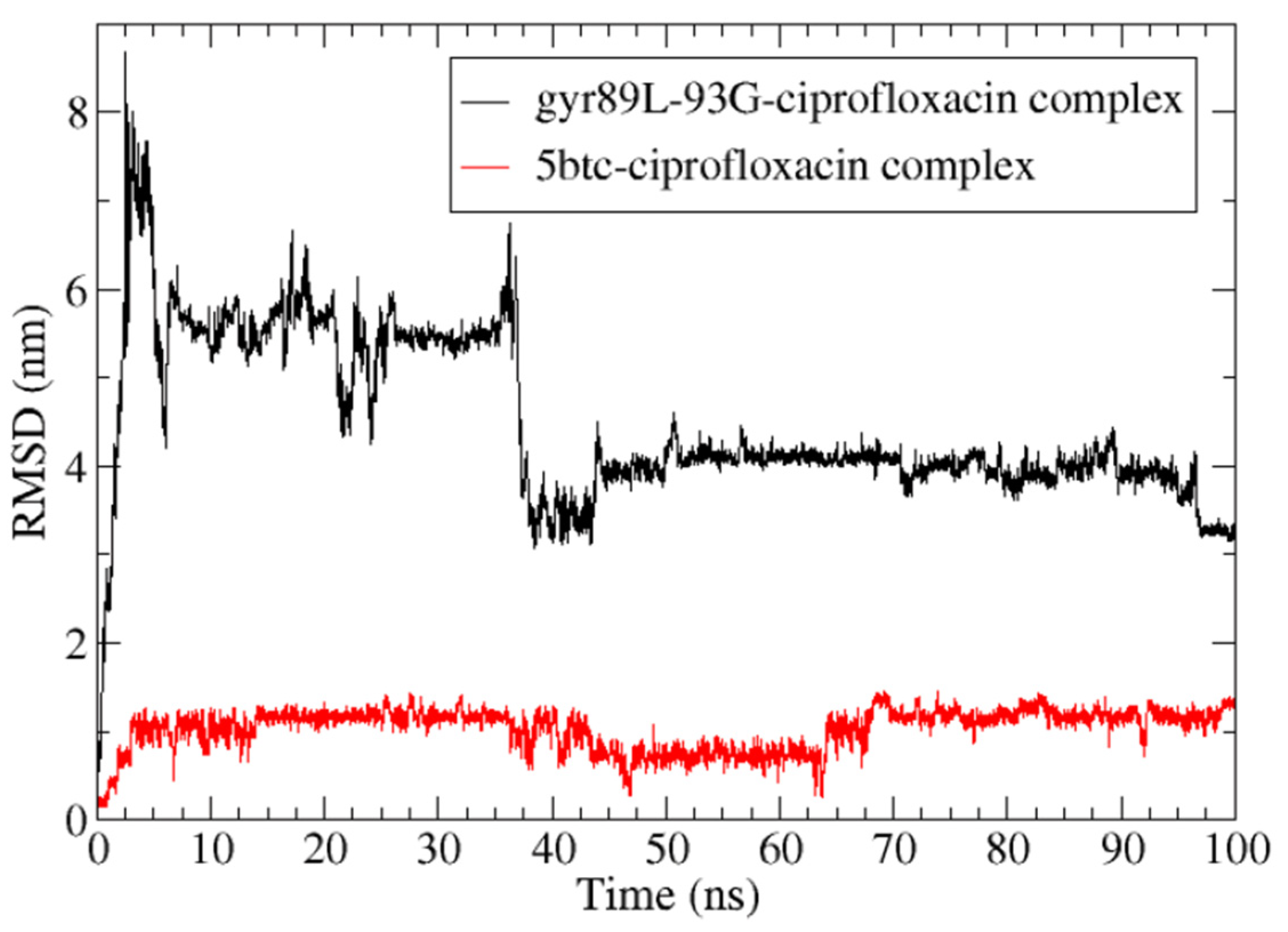

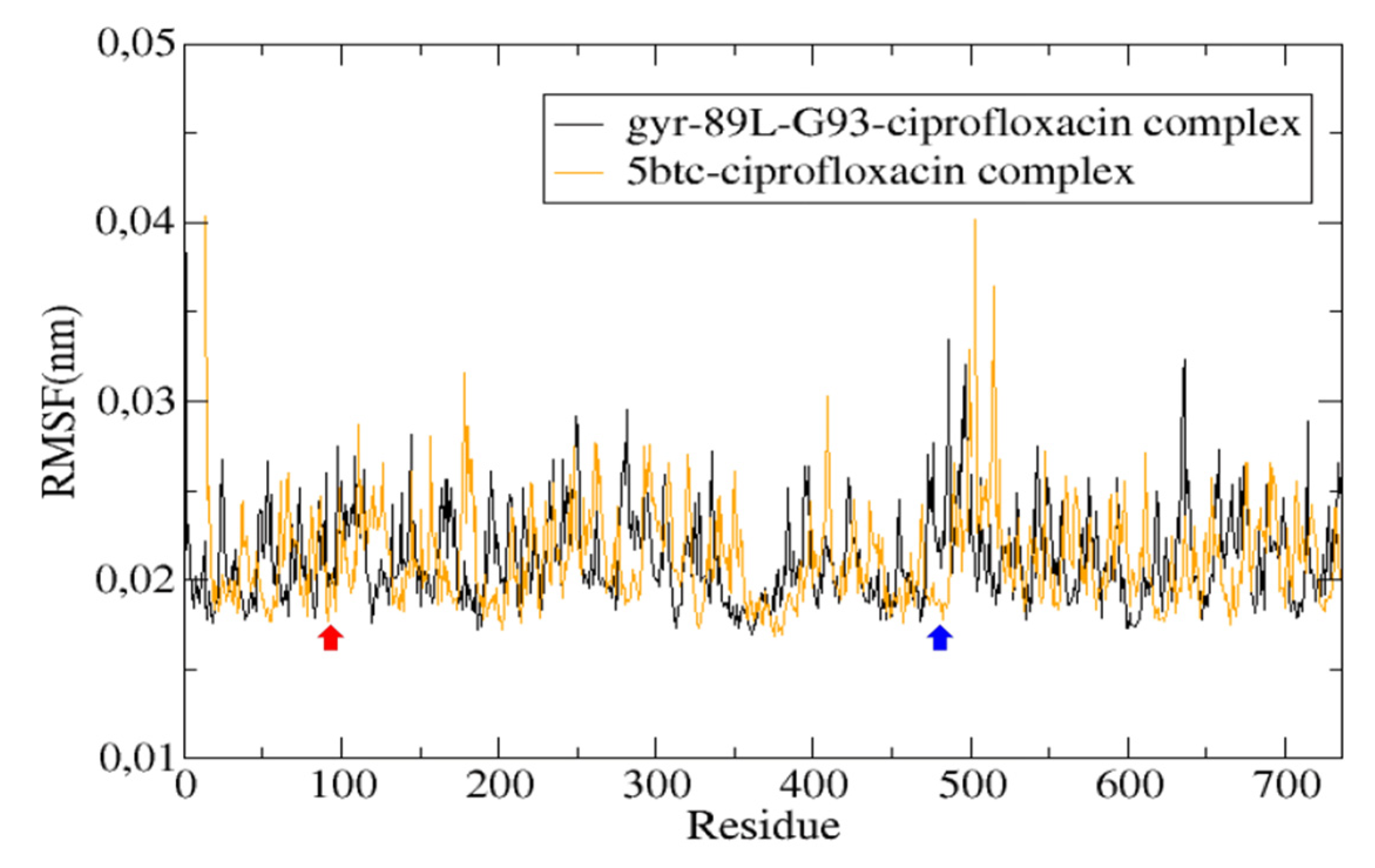

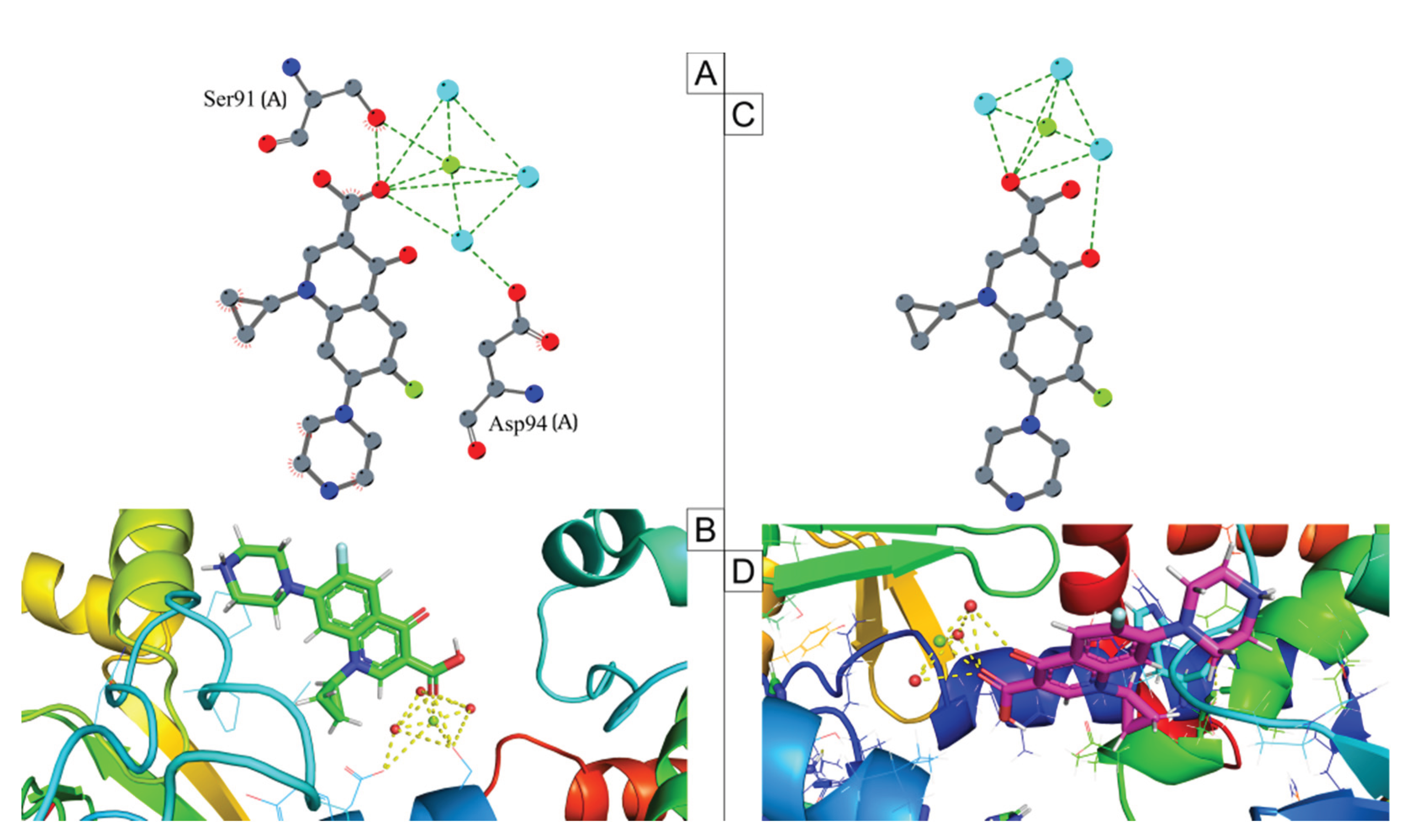

2.6. Mutation Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Origin of Bacterial Strains

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing In Vitro

4.3. Genome Sequencing, Assembling and Annotation

4.4. Genomic Taxonomy

4.5. Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis

4.6. Prediction of Mobile Genetic Elements and CRISPR-Cas Systems

4.7. Identification of Genes Encoding Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Factors

4.8. Mutation Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parte, A.C.; Sardà Carbasse, J.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Reimer, L.C.; Göker, M. List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) Moves to the DSMZ. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020, 70, 5607–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.C.; Efstratiou, A.; Mokrousov, I.; Mutreja, A.; Das, B.; Ramamurthy, T. Diphtheria. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiman-Marangos, S.N.; Gill, S.K.; Mansfield, M.J.; Orrell, K.E.; Doxey, A.C.; Melnyk, R.A. Structures of Distant Diphtheria Toxin Homologs Reveal Functional Determinants of an Evolutionarily Conserved Toxin Scaffold. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista Araújo, M.R.; Bernardes Sousa, M.Â.; Seabra, L.F.; Caldeira, L.A.; Faria, C.D.; Bokermann, S.; Sant’Anna, L.O.; dos Santos, L.S.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L. Cutaneous Infection by Non-Diphtheria-Toxin Producing and Penicillin-Resistant Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Strain in a Patient with Diabetes Mellitus. Access Microbiol 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.R.B.; Ramos, J.N.; de Oliveira Sant’Anna, L.; Bokermann, S.; Santos, M.B.N.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L.; Azevedo, V.; Prates, F.D.; Rodrigues, D.L.N.; Aburjaile, F.F.; et al. Phenotypic and Molecular Characterization and Complete Genome Sequence of a Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Strain Isolated from Cutaneous Infection in an Immunized Individual. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2023, 54, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.N.; Araújo, M.R.B.; Sant’Anna, L.O.; Bokermann, S.; Camargo, C.H.; Prates, F.D.; Sacchi, C.T.; Vieira, V.V.; Campos, K.R.; Santos, M.B.N.; et al. Molecular Characterization and Whole-Genome Sequencing of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Causing Skin Lesion. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 2024, 43, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, C.; Truche, P.; Sousa Salgado, L.; Meireles, T.; Santana, V.; Buda, A.; Bentes, A.; Botelho, F.; Mooney, D. The Impact of COVID-19 on Routine Pediatric Vaccination Delivery in Brazil. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2292–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangel, A.; Berger, A.; Rau, J.; Eisenberg, T.; Kämpfer, P.; Margos, G.; Contzen, M.; Busse, H.-J.; Konrad, R.; Peters, M.; et al. Corynebacterium Silvaticum Sp. Nov., a Unique Group of NTTB Corynebacteria in Wild Boar and Roe Deer. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020, 70, 3614–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, M.V.C.; Galdino, J.H.; Profeta, R.; Oliveira, M.; Tavares, L.; de Castro Soares, S.; Carneiro, P.; Wattam, A.R.; Azevedo, V. Analysis of Corynebacterium Silvaticum Genomes from Portugal Reveals a Single Cluster and a Clade Suggested to Produce Diphtheria Toxin. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazas, M.; Badell, E.; Carmi-Leroy, A.; Criscuolo, A.; Brisse, S. Taxonomic Status of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Biovar Belfanti and Proposal of Corynebacterium Belfantii Sp. Nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2018, 68, 3826–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.J.; Cassiday, P.K.; Bernard, K.A.; Bolt, F.; Steigerwalt, A.G.; Bixler, D.; Pawloski, L.C.; Whitney, A.M.; Iwaki, M.; Baldwin, A.; et al. Novel Diphtheriae in Domestic Cats. Emerg Infect Dis 2010, 16, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crestani, C.; Arcari, G.; Landier, A.; Passet, V.; Garnier, D.; Brémont, S.; Armatys, N.; Carmi-Leroy, A.; Toubiana, J.; Badell, E.; et al. Corynebacterium Ramonii Sp. Nov., a Novel Toxigenic Member of the Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Species Complex. Res Microbiol 2023, 174, 104113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.N.; Araújo, M.R.B.; Baio, P.V.P.; Sant’Anna, L.O.; Veras, J.F.C.; Vieira, É.M.D.; Sousa, M.Â.B.; Camargo, C.H.; Sacchi, C.T.; Campos, K.R.; et al. Molecular Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of the First Corynebacterium Rouxii Strains Isolated in Brazil: A Recent Member of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Complex. BMC Genom Data 2023, 24, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prates, F.D.; Araújo, M.R.B.; Sousa, E.G.; Ramos, J.N.; Viana, M.V.C.; Soares, S. de C.; dos Santos, L.S.; Azevedo, V.A. de C. First Pangenome of Corynebacterium Rouxii, a Potentially Toxigenic Species of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Complex. Bacteria 2024, 3, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.R.B.; Prates, F.D.; Viana, M.V.C.; Santos, L.S.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L.; Camargo, C.H.; Sacchi, C.T.; Campos, K.R.; Vieira, V.V.; Santos, M.B.N.; et al. Genomic Analysis of Two Penicillin- and Rifampin-Resistant Corynebacterium Rouxii Strains Isolated from Cutaneous Infections in Dogs. Res Vet Sci 2024, 179, 105396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsukawa, C.; Komiya, T.; Yamagishi, H.; Ishii, A.; Nishino, S.; Nagahama, S.; Iwaki, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Takahashi, M. Prevalence of Corynebacterium Ulcerans in Dogs in Osaka, Japan. J Med Microbiol 2012, 61, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefer, A.; Herrera-León, S.; Domínguez, L.; Gavín, M.O.; Romero, B.; Piedra, X.B.A.; Calzada, C.S.; Uría González, M.J.; Herrera-León, L. Zoonotic Transmission of Diphtheria from Domestic Animal Reservoir, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contzen, M.; Sting, R.; Blazey, B.; Rau, J. Corynebacterium Ulcerans from Diseased Wild Boars. Zoonoses Public Health 2011, 58, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sting, R.; Pölzelbauer, C.; Eisenberg, T.; Bonke, R.; Blazey, B.; Peters, M.; Riße, K.; Sing, A.; Berger, A.; Dangel, A.; et al. Corynebacterium Ulcerans Infections in Eurasian Beavers (Castor Fiber). Pathogens 2023, 12, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zoysa, A.; Hawkey, P.M.; Engler, K.; George, R.; Mann, G.; Reilly, W.; Taylor, D.; Efstratiou, A. Characterization of Toxigenic Corynebacterium Ulcerans Strains Isolated from Humans and Domestic Cats in the United Kingdom. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 4377–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuursted, K.; Søes, L.M.; Crewe, B.T.; Stegger, M.; Andersen, P.S.; Christensen, J.J. Non-Toxigenic Tox Gene-Bearing Corynebacterium Ulcerans in a Traumatic Ulcer from a Human Case and His Asymptomatic Dog. Microbes Infect 2015, 17, 717–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneen, R.; Giao, P.N.; Solomon, T.; Van, T.T.M.; Hoa, N.T.T.; Long, T.B.; Wain, J.; Day, N.P.J.; Hien, T.T.; Parry, C.M.; et al. Penicillin vs. Erythromycin in the Treatment of Diphtheria. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1998, 27, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crestani, C.; Passet, V.; Rethoret-Pasty, M.; Zidane, N.; Brémont, S.; Badell, E.; Criscuolo, A.; Brisse, S. Microevolution and Genomic Epidemiology of the Diphtheria-Causing Zoonotic Pathogen Corynebacterium Ulcerans. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos-Guaraldi, A.; Sampaio, J.; Santos, C.; Pimenta, F.; Pereira, G.; Pacheco, L.; Miyoshi, A.; Azevedo, V.; Moreira, L.; Gutierrez, F.; et al. First Detection of Corynebacterium Ulcerans Producing a Diphtheria-like Toxin in a Case of Human with Pulmonary Infection in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Area, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2008, 103, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R. Shifting the Genomic Gold Standard for the Prokaryotic Species Definition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 19126–19131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goris, J.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Klappenbach, J.A.; Coenye, T.; Vandamme, P.; Tiedje, J.M. DNA–DNA Hybridization Values and Their Relationship to Whole-Genome Sequence Similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007, 57, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.V.; Ramos, J.N.; dos Santos, L.S.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L. Corynebacterium: Molecular Typing and Pathogenesis of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae and Zoonotic Diphtheria Toxin-Producing Corynebacterium Species. In Molecular Typing in Bacterial Infections, Volume I; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, J.; Huhulescu, S.; Stoeger, A.; Allerberger, F.; Ruppitsch, W. Draft Genome Sequences of Six Corynebacterium Ulcerans Strains Isolated from Humans and Animals in Austria, 2013 to 2019. Microbiol Resour Announc 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, E.; Al-Dilaimi, A.; Papavasiliou, P.; Schneider, J.; Viehoever, P.; Burkovski, A.; Soares, S.C.; Almeida, S.S.; Dorella, F.A.; Miyoshi, A.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Two Complete Corynebacterium Ulcerans Genomes and Detection of Candidate Virulence Factors. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Scarampella, F.; Iurescia, M.; Donati, V.; Stravino, F.; Lorenzetti, S.; Menichini, E.; Franco, A.; Caprioli, A.; Battisti, A. Non-Toxigenic Corynebacterium Ulcerans Sequence Types 325 and 339 Isolated from Two Dogs with Ulcerative Lesions in Italy. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 2018, 30, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, R.; Kolodkina, V.; Sutcliffe, I.C.; Simpson-Louredo, L.; Hirata, R.; Titov, L.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L.; Burkovski, A.; Sangal, V. Genomic Analyses Reveal Two Distinct Lineages of Corynebacterium Ulcerans Strains. New Microbes New Infect 2018, 25, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B.J.; Huang, I.-T.; Hanage, W.P. Horizontal Gene Transfer and Adaptive Evolution in Bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Millan, A. Evolution of Plasmid-Mediated Antibiotic Resistance in the Clinical Context. Trends Microbiol 2018, 26, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, B.A.; Mir, R.A.; Qadri, H.; Dhiman, R.; Almilaibary, A.; Alkhanani, M.; Mir, M.A. Integrons in the Development of Antimicrobial Resistance: Critical Review and Perspectives. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauch, A.; Bischoff, N.; Brune, I.; Kalinowski, J. Insights into the Genetic Organization of the Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Erythromycin Resistance Plasmid PNG2 Deduced from Its Complete Nucleotide Sequence. Plasmid 2003, 49, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennart, M.; Panunzi, L.G.; Rodrigues, C.; Gaday, Q.; Baines, S.L.; Barros-Pinkelnig, M.; Carmi-Leroy, A.; Dazas, M.; Wehenkel, A.M.; Didelot, X.; et al. Population Genomics and Antimicrobial Resistance in Corynebacterium Diphtheriae. Genome Med 2020, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcari, G.; Hennart, M.; Badell, E.; Brisse, S. Multidrug-Resistant Toxigenic Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Sublineage 453 with Two Novel Resistance Genomic Islands. Microb Genom 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan, W.Y.; Parab, L.; Bertels, F.; Gallie, J. A More Significant Role for Insertion Sequences in Large-Scale Rearrangements in Bacterial Genomes. mBio 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandecraen, J.; Chandler, M.; Aertsen, A.; Van Houdt, R. The Impact of Insertion Sequences on Bacterial Genome Plasticity and Adaptability. Crit Rev Microbiol 2017, 43, 709–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udaondo, Z.; Abram, K.Z.; Kothari, A.; Jun, S.-R. Insertion Sequences and Other Mobile Elements Associated with Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Enterococcus Isolates from an Inpatient with Prolonged Bacteraemia. Microb Genom 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahillon, J.; Chandler, M. Insertion Sequences. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 1998, 62, 725–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyton-Carcaman, B.; Abanto, M. Beyond to the Stable: Role of the Insertion Sequences as Epidemiological Descriptors in Corynebacterium Striatum. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyton, B.; Ramos, J.N.; Baio, P.V.P.; Veras, J.F.C.; Souza, C.; Burkovski, A.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L.; Vieira, V.V.; Abanto Marin, M. Treat Me Well or Will Resist: Uptake of Mobile Genetic Elements Determine the Resistome of Corynebacterium Striatum. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 7499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekizuka, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Komiya, T.; Kenri, T.; Takeuchi, F.; Shibayama, K.; Takahashi, M.; Kuroda, M.; Iwaki, M. Corynebacterium Ulcerans 0102 Carries the Gene Encoding Diphtheria Toxin on a Prophage Different from the C. Diphtheriae NCTC 13129 Prophage. BMC Microbiol 2012, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, D.R.; Di Blasi, D.; Bruns, J.A.; Empson, B.; Light, I.; Ghannam, M.; Castillo, S.; Quijada, B.; Zorawik, M.; Garcia-Vedrenne, A.E.; et al. Characterization of Genomic Diversity In Bacteriophages Infecting Rhodococcus 2022.

- Pope, W.H.; Mavrich, T.N.; Garlena, R.A.; Guerrero-Bustamante, C.A.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Montgomery, M.T.; Russell, D.A.; Warner, M.H.; Hatfull, G.F. Bacteriophages of Gordonia Spp. Display a Spectrum of Diversity and Genetic Relationships. mBio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhnbashi, O.S.; Meier, T.; Mitrofanov, A.; Backofen, R.; Voß, B. CRISPR-Cas Bioinformatics. Methods 2020, 172, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karginov, F. V.; Hannon, G.J. The CRISPR System: Small RNA-Guided Defense in Bacteria and Archaea. Mol Cell 2010, 37, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.-W.; Asmah Hani, A.W.; Nurul Aina Murni, C.A.; Pusparani, R.R.; Chong, C.K.; Verasahib, K.; Yusoff, W.N.W.; Noordin, N.M.; Tee, K.K.; Yin, W.-F.; et al. Comparative Genomic and Phylogenetic Analysis of a Toxigenic Clinical Isolate of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Strain B-D-16-78 from Malaysia. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2017, 54, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, D.; Amlinger, L.; Rath, A.; Lundgren, M. The CRISPR-Cas Immune System: Biology, Mechanisms and Applications. Biochimie 2015, 117, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.; Long, J.; Teng, Y.; Yang, H.; Xi, Y.; Duan, G.; Chen, S. Diversity of the Type I-U CRISPR-Cas System in Bifidobacterium. Arch Microbiol 2021, 203, 3235–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Zhou, X.; Pei, Z.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, B.; Chen, W. Characterization of CRISPR-Cas Systems in Bifidobacterium Breve. Microb Genom 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahraman Ilıkkan, Ö. Analysis of Probiotic Bacteria Genomes: Comparison of CRISPR/Cas Systems and Spacer Acquisition Diversity. Indian J Microbiol 2022, 62, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadway, M.M.; Rogers, E.A.; Chang, C.; Huang, I.-H.; Dwivedi, P.; Yildirim, S.; Schmitt, M.P.; Das, A.; Ton-That, H. Pilus Gene Pool Variation and the Virulence of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Clinical Isolates during Infection of a Nematode. J Bacteriol 2013, 195, 3774–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandlik, A.; Swierczynski, A.; Das, A.; Ton-That, H. Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Employs Specific Minor Pilins to Target Human Pharyngeal Epithelial Cells. Mol Microbiol 2007, 64, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billington, S.J.; Esmay, P.A.; Songer, J.G.; Jost, B.H. Identification and Role in Virulence of Putative Iron Acquisition Genes from Corynebacterium Pseudotuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2002, 208, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkle, C.A.; Schmitt, M.P. Analysis of a DtxR-Regulated Iron Transport and Siderophore Biosynthesis Gene Cluster in Corynebacterium Diphtheriae. J Bacteriol 2005, 187, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyman, L.R.; Peng, E.D.; Schmitt, M.P. Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Iron-Regulated Surface Protein HbpA Is Involved in the Utilization of the Hemoglobin-Haptoglobin Complex as an Iron Source. J Bacteriol 2018, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazek, E.S.; Hammack, C.A.; Schmitt, M.P. Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Genes Required for Acquisition of Iron from Haemin and Haemoglobin Are Homologous to ABC Haemin Transporters. Mol Microbiol 2000, 36, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkovski, A. Proteomics of Toxigenic Corynebacteria. Proteomes 2023, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yellaboina, S.; Ranjan, S.; Chakhaiyar, P.; Hasnain, S.E.; Ranjan, A. Prediction of DtxR Regulon: Identification of Binding Sites and Operons Controlled by Diphtheria Toxin Repressor in Corynebacterium Diphtheriae. BMC Microbiol 2004, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, P.J.; Cuevas, W.A.; Songer, J.G. Toxic Phospholipases D of Corynebacterium Pseudotuberculosis, C. Ulcerans and Arcanobacterium Haemolyticum: Cloning and Sequence Homology. Gene 1995, 156, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, P.J.; Bradley, G.A.; Songer, J.G. Targeted Mutagenesis of the Phospholipase D Gene Results in Decreased Virulence of Corynebacterium Pseudotuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 1994, 12, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKean, S.C.; Davies, J.K.; Moore, R.J. Expression of Phospholipase D, the Major Virulence Factor of Corynebacterium Pseudotuberculosis, Is Regulated by Multiple Environmental Factors and Plays a Role in Macrophage Death. Microbiology (N Y) 2007, 153, 2203–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, T.; Kutzer, P.; Peters, M.; Sing, A.; Contzen, M.; Rau, J. Nontoxigenic Tox -Bearing Corynebacterium Ulcerans Infection among Game Animals, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 2014, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, L.O.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L.; Andrade, A.F.B. Novel Lipoarabinomannan-like Lipoglycan (CdiLAM) Contributes to the Adherence of Corynebacterium Diphtheriae to Epithelial Cells. Arch Microbiol 2008, 190, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankute, M.; Alderwick, L.J.; Moorey, A.R.; Joe, M.; Gurcha, S.S.; Eggeling, L.; Lowary, T.L.; Dell, A.; Pang, P.-C.; Yang, T.; et al. The Singular Corynebacterium Glutamicum Emb Arabinofuranosyltransferase Polymerises the α(1 → 5) Arabinan Backbone in the Early Stages of Cell Wall Arabinan Biosynthesis. The Cell Surface 2018, 2, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-U.; Song, J.-Y.; Kwon, Y.-C.; Chung, M.-J.; Jun, J.-S.; Park, J.-W.; Park, S.-G.; Hwang, H.-R.; Choi, S.-H.; Baik, S.-C.; et al. Effect of the Urease Accessory Genes on Activation of the Helicobacter Pylori Urease Apoprotein. Mol Cells 2005, 20, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson-Louredo, L.; Ramos, J.N.; Peixoto, R.S.; Santos, L.S.; Antunes, C.A.; Ladeira, E.M.; Santos, C.S.; Vieira, V.V.; Bôas, M.H.S.V.; Hirata, R.; et al. Corynebacterium Ulcerans Isolates from Humans and Dogs: Fibrinogen, Fibronectin and Collagen-Binding, Antimicrobial and PFGE Profiles. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014, 105, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.R.B.; Prates, F.D.; Ramos, J.N.; Sousa, E.G.; Bokermann, S.; Sacchi, C.T.; de Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L.; Campos, K.R.; Sousa, M.Â.B.; Vieira, V.V.; et al. Infection by a Multidrug-Resistant Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Strain: Prediction of Virulence Factors, CRISPR-Cas System Analysis, and Structural Implications of Mutations Conferring Rifampin Resistance. Funct Integr Genomics 2024, 24, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, K.J.; Kerns, R.J.; Osheroff, N. Mechanism of Quinolone Action and Resistance. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drlica, K.; Malik, M.; Kerns, R.J.; Zhao, X. Quinolone-Mediated Bacterial Death. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008, 52, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blower, T.R.; Williamson, B.H.; Kerns, R.J.; Berger, J.M. Crystal Structure and Stability of Gyrase–Fluoroquinolone Cleaved Complexes from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 1706–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlkonig, A.; Chan, P.F.; Fosberry, A.P.; Homes, P.; Huang, J.; Kranz, M.; Leydon, V.R.; Miles, T.J.; Pearson, N.D.; Perera, R.L.; et al. Structural Basis of Quinolone Inhibition of Type IIA Topoisomerases and Target-Mediated Resistance. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010, 17, 1152–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, J.N.; Valadão, T.B.; Baio, P.V.P.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A.L.; Vieira, V.V. Novel Mutations in the QRDR Region GyrA Gene in Multidrug-Resistance Corynebacterium Spp. Isolates from Intravenous Sites. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruri, F.; Sterling, T.R.; Kaiga, A.W.; Blackman, A.; van der Heijden, Y.F.; Mayer, C.; Cambau, E.; Aubry, A. A Systematic Review of Gyrase Mutations Associated with Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and a Proposed Gyrase Numbering System. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2012, 67, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.M.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Vázquez, F.; Giralt, E.; Vila, J. Relationship between Mutations in the GyrA Gene and Quinolone Resistance in Clinical Isolates of Corynebacterium Striatum and Corynebacterium Amycolatum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005, 49, 1714–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Thanki, N.; Goodfellow, J.M. Hydration of Amino Acid Side Chains: Dependence on Secondary Structure. “Protein Engineering, Design and Selection” 1992, 5, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, M.; Maeda, Y.; Kitano, H. Effect of Hydrophobicity of Amino Acids on the Structure of Water. J Phys Chem B 1997, 101, 7022–7026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving Bacterial Genome Assemblies from Short and Long Sequencing Reads. PLoS Comput Biol 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chklovski, A.; Parks, D.H.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM2: A Rapid, Scalable and Accurate Tool for Assessing Microbial Genome Quality Using Machine Learning. Nat Methods 2023, 20, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orakov, A.; Fullam, A.; Coelho, L.P.; Khedkar, S.; Szklarczyk, D.; Mende, D.R.; Schmidt, T.S.B.; Bork, P. GUNC: Detection of Chimerism and Contamination in Prokaryotic Genomes. Genome Biol 2021, 22, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS Is an Automated High-Throughput Platform for State-of-the-Art Genome-Based Taxonomy. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumeil, P.-A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk: A Toolkit to Classify Genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1925–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, L.; Glover, R.H.; Humphris, S.; Elphinstone, J.G.; Toth, I.K. Genomics and Taxonomy in Diagnostics for Food Security: Soft-Rotting Enterobacterial Plant Pathogens. Analytical Methods 2016, 8, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Carbasse, J.S.; Peinado-Olarte, R.L.; Göker, M. TYGS and LPSN: A Database Tandem for Fast and Reliable Genome-Based Classification and Nomenclature of Prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D801–D807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautreau, G.; Bazin, A.; Gachet, M.; Planel, R.; Burlot, L.; Dubois, M.; Perrin, A.; Médigue, C.; Calteau, A.; Cruveiller, S.; et al. PPanGGOLiN: Depicting Microbial Diversity via a Partitioned Pangenome Graph. PLoS Comput Biol 2020, 16, e1007732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol Biol Evol 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Taylor, B.; Delaney, A.J.; Soares, J.; Seemann, T.; Keane, J.A.; Harris, S.R. SNP-Sites: Rapid Efficient Extraction of SNPs from Multi-FASTA Alignments. Microb Genom 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (ITOL) v6: Recent Updates to the Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation Tool. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; García-Fernández, A.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Hasman, H. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids Using PlasmidFinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Néron, B.; Littner, E.; Haudiquet, M.; Perrin, A.; Cury, J.; Rocha, E. IntegronFinder 2.0: Identification and Analysis of Integrons across Bacteria, with a Focus on Antibiotic Resistance in Klebsiella. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Tang, H. ISEScan: Automated Identification of Insertion Sequence Elements in Prokaryotic Genomes. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3340–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishart, D.S.; Han, S.; Saha, S.; Oler, E.; Peters, H.; Grant, J.R.; Stothard, P.; Gautam, V. PHASTEST: Faster than PHASTER, Better than PHAST. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, W443–W450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.R.; Enns, E.; Marinier, E.; Mandal, A.; Herman, E.K.; Chen, C.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Stothard, P. Proksee: In-Depth Characterization and Visualization of Bacterial Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, W484–W492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvin, D.; Bernheim, A.; Toffano-Nioche, C.; Touchon, M.; Michalik, J.; Néron, B.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Vergnaud, G.; Gautheret, D.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRCasFinder, an Update of CRISRFinder, Includes a Portable Version, Enhanced Performance and Integrates Search for Cas Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W246–W251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K.S.; Koonin, E. V. Annotation and Classification of CRISPR-Cas Systems. In; 2015; pp. 47–75.

- Biswas, A.; Gagnon, J.N.; Brouns, S.J.J.; Fineran, P.C.; Brown, C.M. CRISPRTarget. RNA Biol 2013, 10, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangal, V.; Fineran, P.C.; Hoskisson, P.A. Novel Configurations of Type I and II CRISPR–Cas Systems in Corynebacterium Diphtheriae. Microbiology (N Y) 2013, 159, 2118–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. VFDB 2022: A General Classification Scheme for Bacterial Virulence Factors. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D912–D917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.L.N.; Ariute, J.C.; Rodrigues da Costa, F.M.; Benko-Iseppon, A.M.; Barh, D.; Azevedo, V.; Aburjaile, F. PanViTa: Pan Virulence and ResisTance Analysis. Frontiers in Bioinformatics 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. J Mol Biol 2016, 428, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alikhan, N.-F.; Petty, N.K.; Ben Zakour, N.L.; Beatson, S.A. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): Simple Prokaryote Genome Comparisons. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—a Multiple Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A Web-based Graphical User Interface for CHARMM. J Comput Chem 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.J.; Headd, J.J.; Moriarty, N.W.; Prisant, M.G.; Videau, L.L.; Deis, L.N.; Verma, V.; Keedy, D.A.; Hintze, B.J.; Chen, V.B.; et al. MolProbity: More and Better Reference Data for Improved All-atom Structure Validation. Protein Science 2018, 27, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, I.A.; Pereira da Silva, M.M.; Galheigo, M.; Krempser, E.; de Magalhães, C.S.; Correa Barbosa, H.J.; Dardenne, L.E. DockThor-VS: A Free Platform for Receptor-Ligand Virtual Screening. J Mol Biol 2024, 436, 168548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D. CHARMM36m: An Improved Force Field for Folded and Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Nat Methods 2017, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; Hatcher, E.; Acharya, C.; Kundu, S.; Zhong, S.; Shim, J.; Darian, E.; Guvench, O.; Lopes, P.; Vorobyov, I.; et al. CHARMM General Force Field: A Force Field for Drug-like Molecules Compatible with the CHARMM All-atom Additive Biological Force Fields. J Comput Chem 2010, 31, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemkul, J. From Proteins to Perturbed Hamiltonians: A Suite of Tutorials for the GROMACS-2018 Molecular Simulation Package [Article v1.0]. Living J Comput Mol Sci 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Swindells, M.B. LigPlot+: Multiple Ligand–Protein Interaction Diagrams for Drug Discovery. J Chem Inf Model 2011, 51, 2778–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Strain | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IHP37393 | IHP103889 | IHP106492 | |

| Accession number | JBGNWQ000000000 | JBGNWN000000000 | JBGNWM000000000 |

| Platform | Illumina® NextSeq 550 | Illumina® NextSeq 550 | Illumina® NextSeq 550 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.99 |

| Contamination (%) | 0,74 | 0,29 | 0,60 |

| Coverage | 251x | 293x | 261x |

| Chimerism | No | No | No |

| Total length (bp) | 2,489,063 | 2,496,757 | 2,521,744 |

| GC (%) | 53.3 | 53.3 | 53.3 |

| Contigs | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| N50 | 815040 | 808602 | 828787 |

| L50 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| CDS | 2242 | 2252 | 2293 |

| rRNAs | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| tRNAs | 51 | 51 | 51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).