Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Viruses, Cell Cultures, Plasmids

2.2. Preparation of DNA Template pVAX-Cas1CC-H5

2.3. In Vitro mRNA Synthesis

2.4. Lipid Nanoparticles Synthesis

2.5. Determination of Hydrodynamic Size and ζ-Potential of LNPs

2.6. The Quantification of mRNA-H5-LNP Encapsulation

2.7. Electron Microscopy of LNPs Formulations

2.8. Immunization of BALB/c Mice with mRNA-H5

2.9. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.10. In Vitro Microneutralization Assay

2.11. Assessment of T-Cell Response by Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS)

2.12. Virulence

2.13. Challenge Study

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

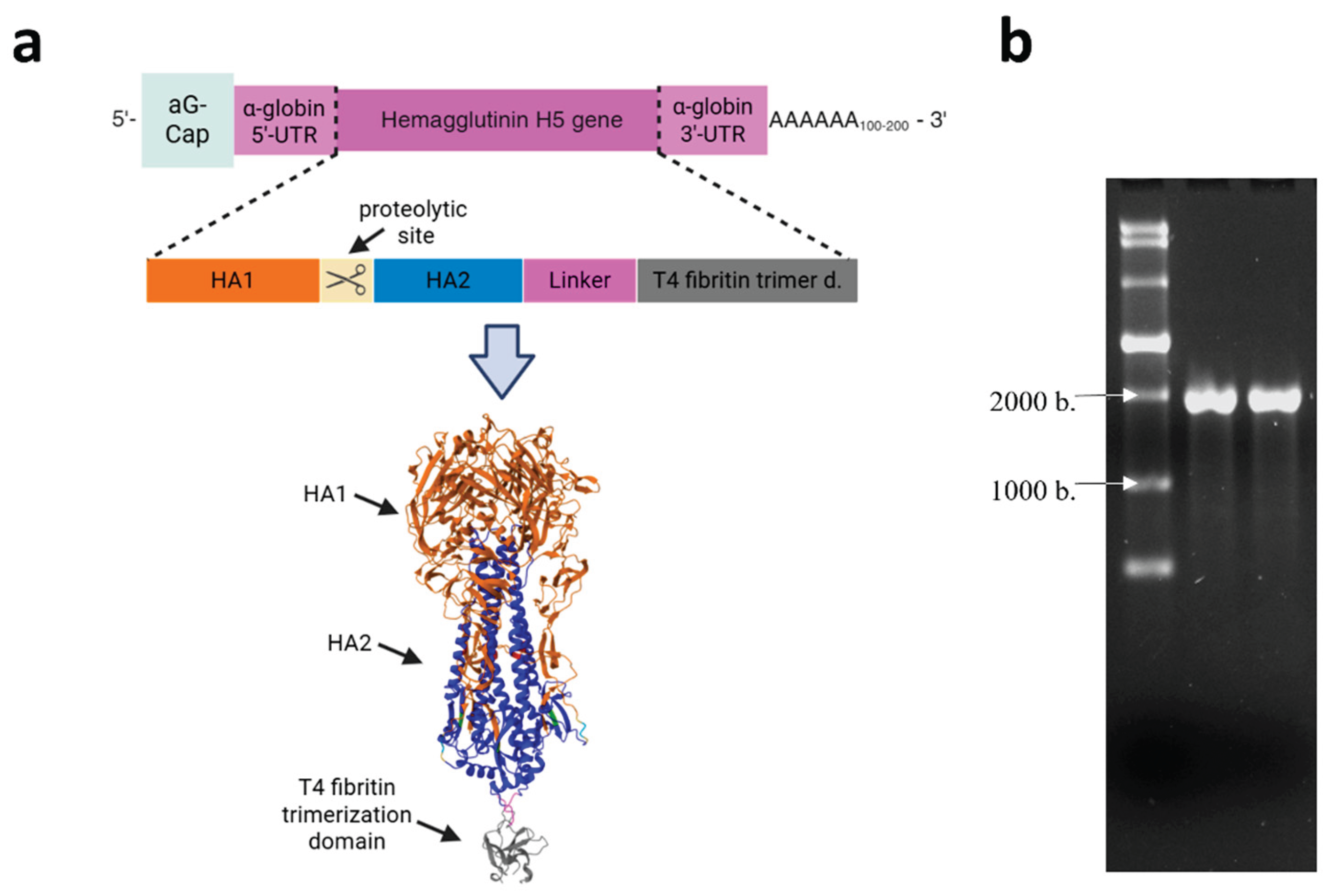

3.1. Preparation of DNA Template and mRNA Synthesis

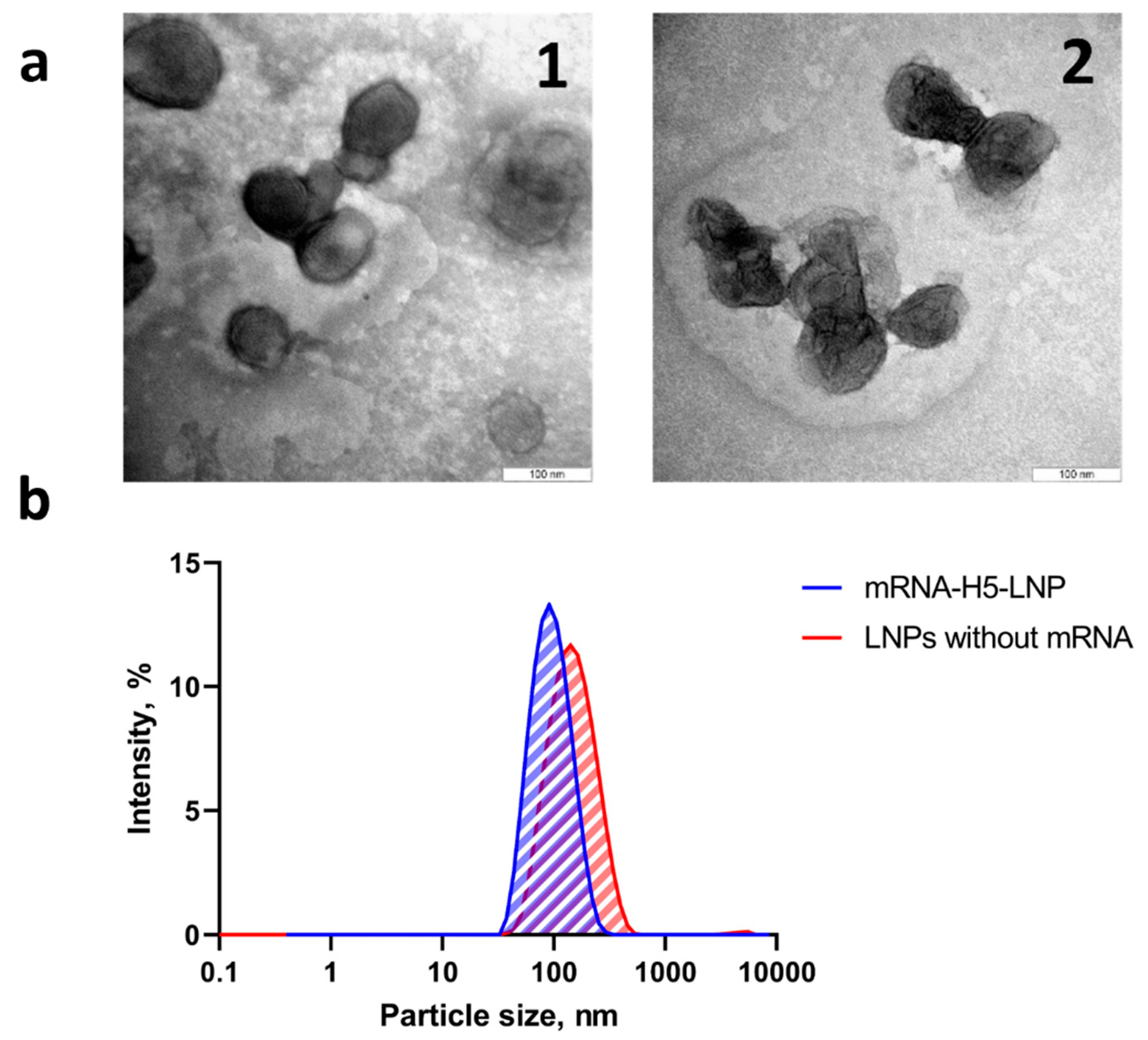

3.2. Lipid Nanoparticles Synthesis and Characterization

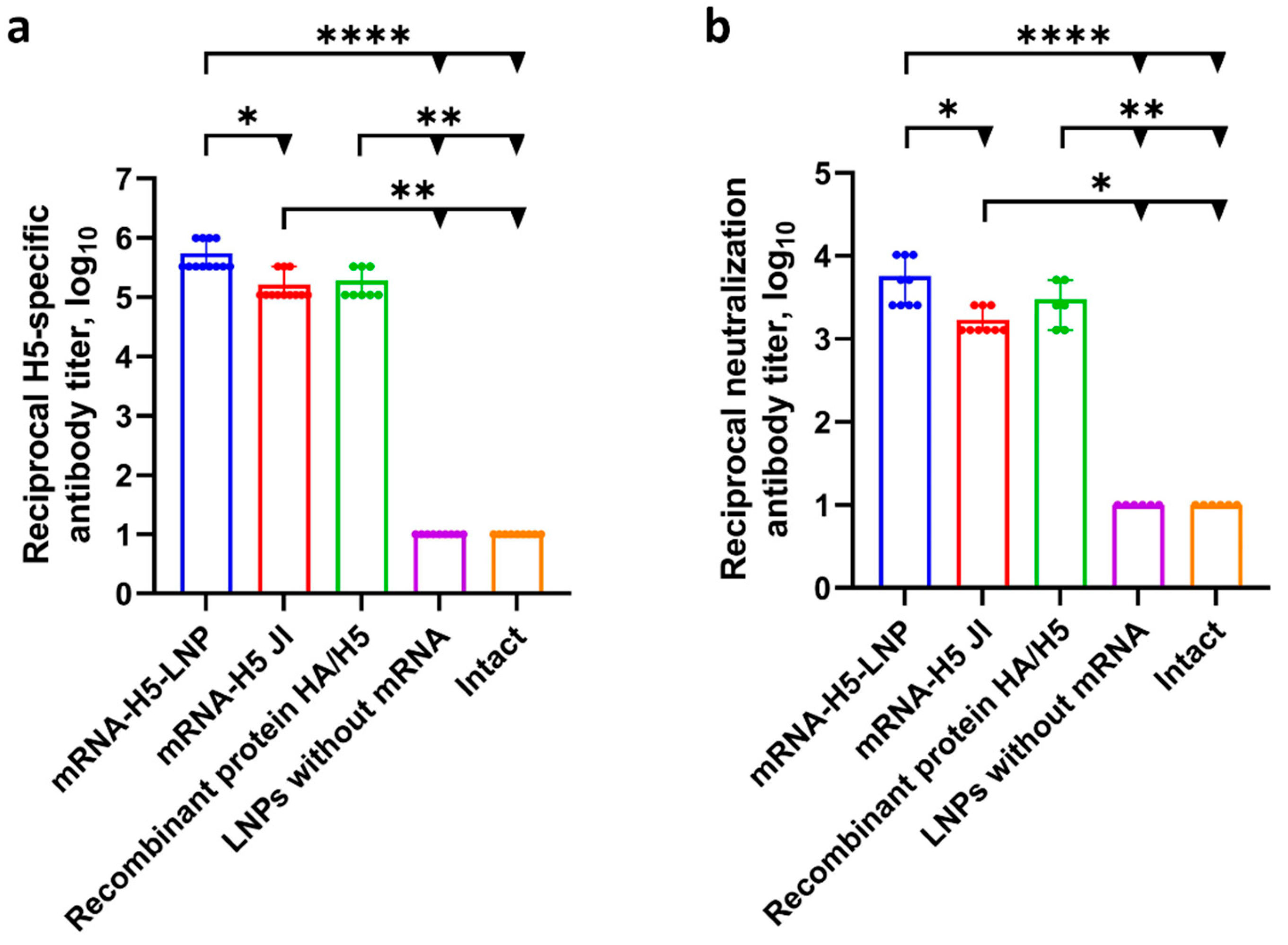

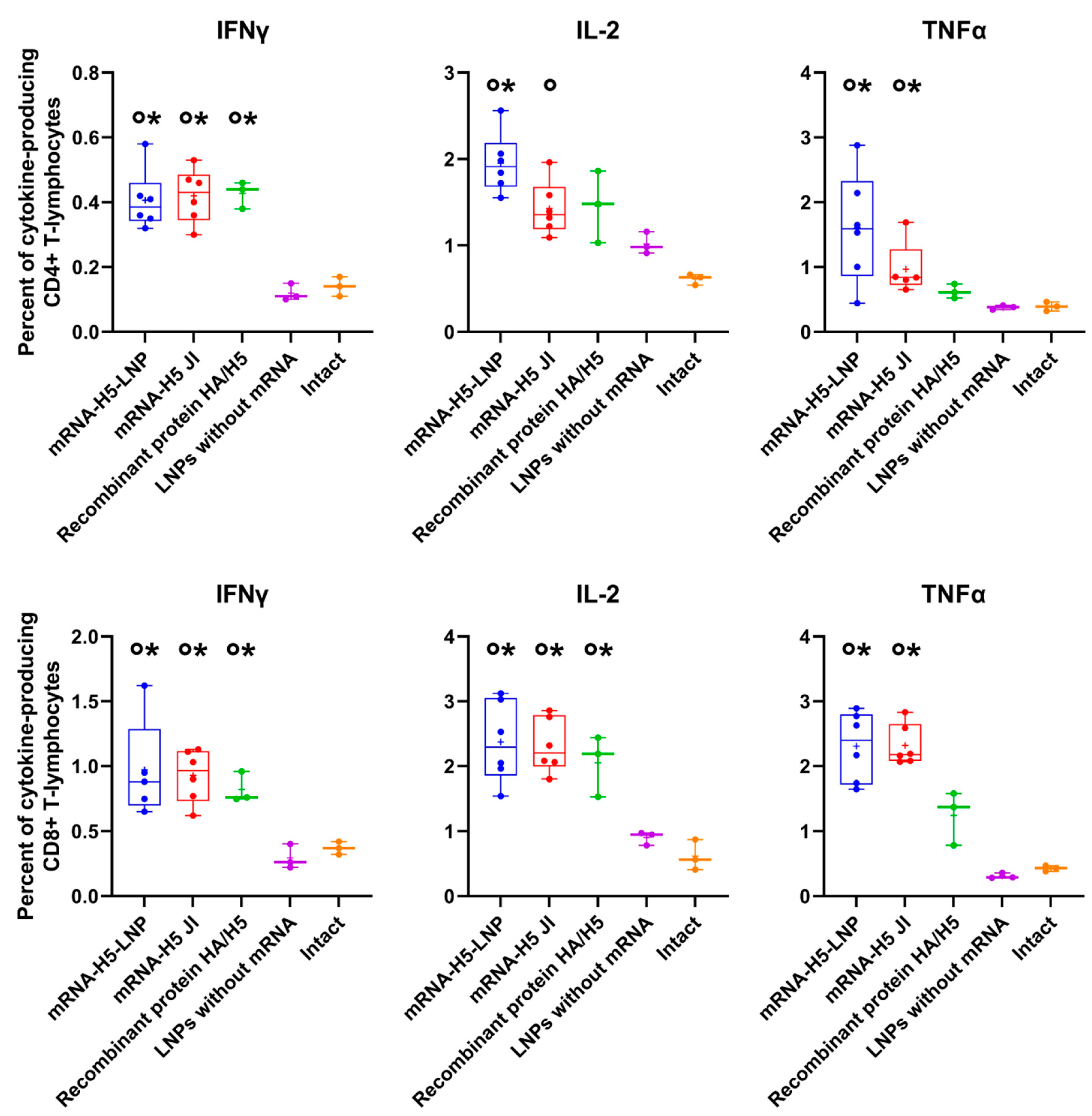

3.3. A Comparison of the Immunogenicity of mRNA-H5 Administered to BALB/c Mice Using LNPs and JI

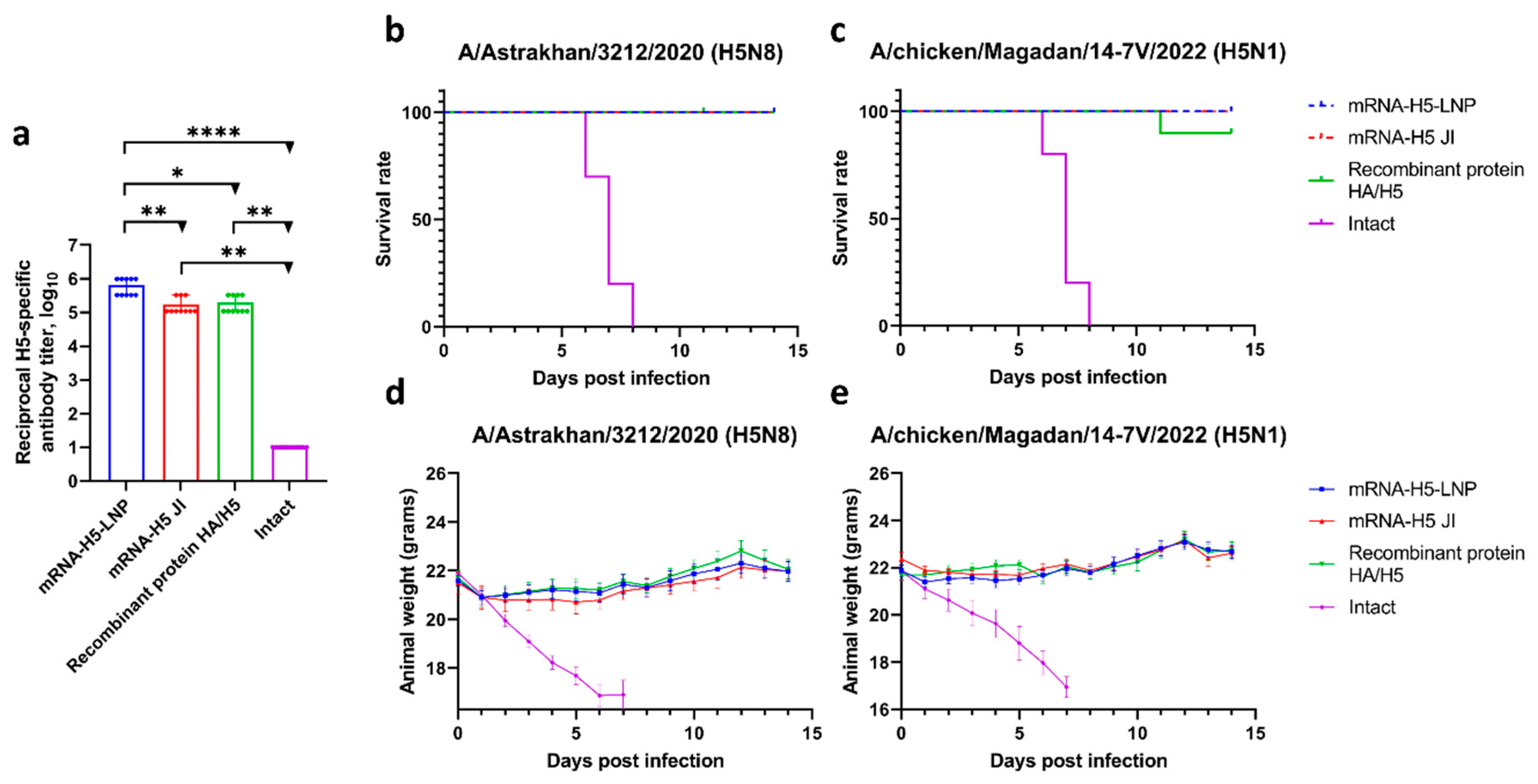

3.4. Study of the Ability of mRNA-H5 Delivered by LNPs and JI to Protect Mice from Lethal Challenge with Avian Influenza A/H5 Viruses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| LNPs | Lipid nanoparticles |

| JI | Needle-free jet injection |

| HPAI | Highly pathogenic avian influenza |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| HA | Hemagglutinin |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ICS | Intracellular cytokine staining |

| MLD50 | 50% lethal dose |

| PMA | Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate |

References

- Hannoun, C. The Evolving History of Influenza Viruses and Influenza Vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2013, 12, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, N.; Esaki, M.; Kojima, I.; Khalil, A.M.; Osuga, S.; Shahein, M.A.; Okuya, K.; Ozawa, M.; Alhatlani, B.Y. Phylogenetic Characterization of Novel Reassortant 2.3.4.4b H5N8 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses Isolated from Domestic Ducks in Egypt During the Winter Season 2021–2022. Viruses 2024, 16, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuBakar, U.; Amrani, L.; Kamarulzaman, F.A.; Karsani, S.A.; Hassandarvish, P.; Khairat, J.E. Avian Influenza Virus Tropism in Humans. Viruses 2023, 15, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, R.; Giles, M.L.; Crawford, N.W.; Buttery, J. Systematic Review of Avian Influenza Virus Infection and Outcomes during Pregnancy. Emerg Infect Dis 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avian Influenza Weekly Update # 1002: 20 June 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/publications/m/item/avian-influenza-weekly-update---1002--20-june-2025 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Kim, D.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Jeong, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.-K.; Youk, S.; Song, C.-S. Newcastle Disease Virus Expressing Clade 2.3.4.4b H5 Hemagglutinin Confers Protection against Lethal H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in BALB/c Mice. Front Vet Sci 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, C.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Yang, C.-R.; Yang, Y.-C.; Chen, P.-L.; Lin, Y.-T.; Wang, P.-R.; Lee, M.-S.; Liang, S.-M.; Hsiao, P.-W. Vaccine Optimization for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza: Assessment of Antibody Responses and Protection for Virus-like Particle Vaccines in Chickens. Vaccine X 2024, 20, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yang, K.; Li, R.; Zhang, L. MRNA Vaccine Era—Mechanisms, Drug Platform and Clinical Prospection. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Karikó, K.; Türeci, Ö. MRNA-Based Therapeutics — Developing a New Class of Drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014, 13, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabrodskaya, Y.A.; Gavrilova, N.V.; Elpaeva, E.A.; Lozhkov, A.A.; Vysochinskaya, V.V.; Dobrovolskaya, O.A.; Dovbysh, O.V.; Zimmerman, E.L.; Dav, P.N.; Brodskaia, A.V.; et al. MRNA Encoding Antibodies against Hemagglutinin and Nucleoprotein Prevents Influenza Virus Infection in Vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2024, 738, 150945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Fernández, S.; Lacroix, C.; Exposito, J.-Y.; Verrier, B. Tailoring MRNA Vaccine to Balance Innate/Adaptive Immune Response. Trends Mol Med 2020, 26, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Porter, F.W.; Weissman, D. MRNA Vaccines — a New Era in Vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorza, F.; Pardi, N. New Kids on the Block: RNA-Based Influenza Virus Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2018, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagigi, A.; Douradinha, B. Have MRNA Vaccines Sentenced DNA Vaccines to Death? Expert Rev Vaccines 2023, 22, 1154–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, D.W.C. New International Guidance on Quality, Safety and Efficacy of DNA Vaccines. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furey, C.; Scher, G.; Ye, N.; Kercher, L.; DeBeauchamp, J.; Crumpton, J.C.; Jeevan, T.; Patton, C.; Franks, J.; Rubrum, A.; et al. Development of a Nucleoside-Modified MRNA Vaccine against Clade 2.3.4.4b H5 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zeng, X.; Ren, W.; Liao, P.; Zhu, B. Protective Efficacy of a Universal Influenza MRNA Vaccine against the Challenge of H1 and H5 Influenza A Viruses in Mice. mLife 2023, 2, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tian, C.; Zhu, J.; Wang, S.; Ao, X.; He, Y.; Chen, H.; Liao, X.; Kong, D.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Avian Influenza MRNA Vaccine Encoding Hemagglutinin Provides Complete Protection against Divergent H5N1 Viruses in Specific-Pathogen-Free Chickens. J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vysochinskaya, V.; Shishlyannikov, S.; Zabrodskaya, Y.; Shmendel, E.; Klotchenko, S.; Dobrovolskaya, O.; Gavrilova, N.; Makarova, D.; Plotnikova, M.; Elpaeva, E.; et al. Influence of Lipid Composition of Cationic Liposomes 2X3-DOPE on MRNA Delivery into Eukaryotic Cells. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, T.; Hu, B.; Zhang, M.; Guo, S.; Xiao, H.; Liang, X.-J.; Huang, Y. The Challenge and Prospect of MRNA Therapeutics Landscape. Biotechnol Adv 2020, 40, 107534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, K.S.; Flynn, B.; Foulds, K.E.; Francica, J.R.; Boyoglu-Barnum, S.; Werner, A.P.; Flach, B.; O’Connell, S.; Bock, K.W.; Minai, M.; et al. Evaluation of the MRNA-1273 Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in Nonhuman Primates. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 1544–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 MRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Liang, Z.; Mao, Q.; Liu, D.; Wu, X.; Xu, M. Research Advances on the Stability of MRNA Vaccines. Viruses 2023, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Vervaeke, P.; Gao, Y.; Opsomer, L.; Sun, Q.; Snoeck, J.; Devriendt, B.; Zhong, Z.; Sanders, N.N. Immunogenicity and Biodistribution of Lipid Nanoparticle Formulated Self-Amplifying MRNA Vaccines against H5 Avian Influenza. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-H.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Han, M.-H.; Jung, H.-Y.; Choi, J.-Y.; Cho, J.-H.; Kim, C.-D.; Kim, Y.-L.; Park, S.-H. New-Onset Kidney Diseases after COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Series. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Song, L.; Zhu, B.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D.; Li, Y. Advances in COVID-19 MRNA Vaccine Development. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisakov, D.N.; Karpenko, L.I.; Kisakova, L.A.; Sharabrin, S.V.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Starostina, E.V.; Taranov, O.S.; Ivleva, E.K.; Pyankov, O.V.; Zaykovskaya, A.V.; et al. Jet Injection of Naked MRNA Encoding the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Induces a High Level of a Specific Immune Response in Mice. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Matsui-Masai, M.; Yasui, F.; Hayashi, A.; Tockary, T.A.; Akinaga, S.; Kohara, M.; Kataoka, K.; Uchida, S. Jet Injection Potentiates Naked MRNA SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Mice and Non-Human Primates by Adding Physical Stress to the Skin 2023.

- Wang, C.; Tang, X.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Han, B.; Sun, Y.; Guo, J.; Peng, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Intradermal Delivery of SARS-CoV-2 RBD3-Fc MRNA Vaccines via a Needle-Free Injection System Induces Robust Immune Responses in Rats. Front Immunol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, H.; Ogura, M.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Atobe, S.; Terai, K. Mechanism of Jet Injector-Induced Plasmid DNA Uptake: Contribution of Shear Stress and Endocytosis. Int J Pharm 2021, 609, 121200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoda, J.; Mizoguchi, I.; Inoue, S.; Watanabe, A.; Sekine, A.; Yamagishi, M.; Miyakawa, S.; Yamaguchi, N.; Horio, E.; Katahira, Y.; et al. A Promising Needle-Free Pyro-Drive Jet Injector for Augmentation of Immunity by Intradermal Injection as a Physical Adjuvant. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 9094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnekave, M.; Furmanov, K.; Hovav, A.-H. Intradermal Naked Plasmid DNA Immunization: Mechanisms of Action. Expert Rev Vaccines 2011, 10, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipe, D.; Howley, P. Fields Virology, 6th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 374–414. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, S.; Holmes, E.C.; Pybus, O.G. The Genomic Rate of Molecular Adaptation of the Human Influenza A Virus. Mol Biol Evol 2011, 28, 2443–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, B.L.; Weaver, E.A. Strategies Targeting Hemagglutinin as a Universal Influenza Vaccine. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, A.B.; Post, P.; Rudin, D. Unique Features of a Recombinant Haemagglutinin Influenza Vaccine That Influence Vaccine Performance. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinova, V.R.; Rudometov, A.P.; Rudometova, N.B.; Kisakov, D.N.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Kisakova, L.A.; Starostina, E.V.; Fando, A.A.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Tigeeva, E.V.; et al. DNA Vaccine Encoding a Modified Hemagglutinin Trimer of Avian Influenza A Virus H5N8 Protects Mice from Viral Challenge. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudometova, N.B.; Fando, A.A.; Kisakova, L.A.; Kisakov, D.N.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Litvinova, V.R.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Tigeeva, E.V.; Vahitov, D.I.; Sharabrin, S.V.; et al. Immunogenic and Protective Properties of Recombinant Hemagglutinin of Influenza A (H5N8) Virus. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinova, V.R.; Rudometova, N.B.; Kisakova, L.A.; Kisakov, D.N.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Tigeeva, E.V.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Ivanova, K.I.; Marchenko, V.Y.; Ilyicheva, T.N.; et al. Immunogenicity of Experimental DNA Vaccines Encoding Hemagglutinin and Hemagglutinin Stalk of Influenza A (H5N8) Virus. Сибирский научный медицинский журнал 2025, 45, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudometov, A.P.; Litvinova, V.R.; Gudymo, A.S.; Ivanova, K.I.; Rudometova, N.B.; Kisakov, D.N.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Kisakova, L.A.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Tigeeva, E.V.; et al. Dose-Dependent Effect of DNA Vaccine PVAX-H5 Encoding a Modified Hemagglutinin of Influenza A (H5N8) and Its Cross-Reactivity Against A (H5N1) Influenza Viruses of Clade 2.3.4.4b. Viruses 2025, 17, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyankova, O.G.; Susloparov, I.M.; Moiseeva, A.A.; Kolosova, N.P.; Onkhonova, G.S.; Danilenko, A.V.; Vakalova, E.V.; Shendo, G.L.; Nekeshina, N.N.; Noskova, L.N.; et al. Isolation of Clade 2.3.4.4b A(H5N8), a Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus, from a Worker during an Outbreak on a Poultry Farm, Russia, December 2020. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchenko, V.Y.; Svyatchenko, S.V.; Onkhonova, G.S.; Goncharova, N.I.; Ryzhikov, A.B.; Maksyutov, R.A.; Gavrilova, E.V. Review on the Epizootiological Situation on Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza around the World and in Russia in 2022. Problems of Particularly Dangerous Infections 2023, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgoyakova, M.B.; Karpenko, L.I.; Rudometov, A.P.; Volosnikova, E.A.; Merkuleva, I.A.; Starostina, E.V.; Zadorozhny, A.M.; Isaeva, A.A.; Nesmeyanova, V.S.; Shanshin, D.V.; et al. Self-Assembled Particles Combining SARS-CoV-2 RBD Protein and RBD DNA Vaccine Induce Synergistic Enhancement of the Humoral Response in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Manual for the Laboratory Diagnosis and Virological Surveillance of Influenza : WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Decree of the Chief State Sanitary Doctor of the Russian Federation of January 28, 2021 N 4 On Approval of Sanitary Rules and Norms SanPiN 3.3686-21 “Sanitary and Epidemiological Requirements for the Prevention of Infectious Diseases”. Available online: https://Www.Rospotrebnadzor.Ru/Files/News/SP_infections_compressed.Pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025). (In Russian).

- World Health Organization. Antigenic and Genetic Characteristics of Zoonotic Influenza A Viruses and Development of Candidate Vaccine Viruses for Pandemic Preparedness. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/influenza/whoinfluenza-recommendations/vcm-northern-hemisphere-recommendation-2022-2023/202203_zoonotic_vaccinevirusupdate.pdf.

- Mourdikoudis, S.; Pallares, R.M.; Thanh, N.T.K. Characterization Techniques for Nanoparticles: Comparison and Complementarity upon Studying Nanoparticle Properties. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 12871–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, S.; Kiso, M.; Yamada, S.; Someya, K.; Onodera, Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Matsunaga, S.; Uraki, R.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Yamayoshi, S.; et al. An MRNA Vaccine Candidate Encoding H5HA Clade 2.3.4.4b Protects Mice from Clade 2.3.2.1a Virus Infection. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawman, D.W.; Tipih, T.; Hodge, E.; Stone, E.T.; Warner, N.; McCarthy, N.; Granger, B.; Meade-White, K.; Leventhal, S.; Hatzakis, K.; et al. Clade 2.3.4.4b but Not Historical Clade 1 HA Replicating RNA Vaccine Protects against Bovine H5N1 Challenge in Mice. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K.; Muramatsu, H.; Ludwig, J.; Weissman, D. Generating the Optimal MRNA for Therapy: HPLC Purification Eliminates Immune Activation and Improves Translation of Nucleoside-Modified, Protein-Encoding MRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39, e142–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, T.; Luft, D.; Abraham, M.-K.; Reinhardt, S.; Salinas Medina, M.L.; Kurz, J.; Schaller, M.; Avci-Adali, M.; Schlensak, C.; Peter, K.; et al. Cationic Nanoliposomes Meet MRNA: Efficient Delivery of Modified MRNA Using Hemocompatible and Stable Vectors for Therapeutic Applications. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2017, 8, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatziantoniou, S.; Maltezou, H.C.; Tsakris, A.; Poland, G.A.; Anastassopoulou, C. Anaphylactic Reactions to MRNA COVID-19 Vaccines: A Call for Further Study. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2605–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pniewska, E.; Pawliczak, R. The Involvement of Phospholipases A2 in Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Mediators Inflamm 2013, 2013, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, A.; Wickner, P.G.; Saff, R.; Stone, C.A.; Robinson, L.B.; Long, A.A.; Wolfson, A.R.; Williams, P.; Khan, D.A.; Phillips, E.; et al. MRNA Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19 Disease and Reported Allergic Reactions: Current Evidence and Suggested Approach. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021, 9, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trougakos, I.P.; Terpos, E.; Alexopoulos, H.; Politou, M.; Paraskevis, D.; Scorilas, A.; Kastritis, E.; Andreakos, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Adverse Effects of COVID-19 MRNA Vaccines: The Spike Hypothesis. Trends Mol Med 2022, 28, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echaide, M.; Chocarro de Erauso, L.; Bocanegra, A.; Blanco, E.; Kochan, G.; Escors, D. MRNA Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2: Advantages and Caveats. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisakov, D.N.; Kisakova, L.A.; Sharabrin, S.V.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Tigeeva, E.V.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Starostina, E.V.; Zaikovskaya, A.V.; Rudometov, A.P.; Rudometova, N.B.; et al. Delivery of Experimental MRNA Vaccine Encoding the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 by Jet Injection. Bull Exp Biol Med 2024, 176, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooij, P.; Grødeland, G.; Koopman, G.; Andersen, T.K.; Mortier, D.; Nieuwenhuis, I.G.; Verschoor, E.J.; Fagrouch, Z.; Bogers, W.M.; Bogen, B. Needle-Free Delivery of DNA: Targeting of Hemagglutinin to MHC Class II Molecules Protects Rhesus Macaques against H1N1 Influenza. Vaccine 2019, 37, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, M.J.; Lyke, K.E.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Neuzil, K.; Raabe, V.; Bailey, R.; Swanson, K.A.; et al. Phase I/II Study of COVID-19 RNA Vaccine BNT162b1 in Adults. Nature 2020, 586, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Muik, A.; Derhovanessian, E.; Vogler, I.; Kranz, L.M.; Vormehr, M.; Baum, A.; Pascal, K.; Quandt, J.; Maurus, D.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine BNT162b1 Elicits Human Antibody and TH1 T Cell Responses. Nature 2020, 586, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombu, C.Y.; Kroubi, M.; Zibouche, R.; Matran, R.; Betbeder, D. Characterization of Endocytosis and Exocytosis of Cationic Nanoparticles in Airway Epithelium Cells. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 355102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatini, P. Disposition Kinetics of Phospholipid Liposomes. In Neurobiology of Essential Fatty Acids. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Bazan, N.G., Murphy, M.G., Toffano, G., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; Volume 318, pp. 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyes, J.; Palmer, L.; Bremner, K.; MacLachlan, I. Cationic Lipid Saturation Influences Intracellular Delivery of Encapsulated Nucleic Acids. Journal of Controlled Release 2005, 107, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Formulations | Average particle size, nm | Polydispersity index | ζ - potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA-H5-LNP | 93.5±0.8 | 0.149 ± 0.01 | -0.02±0.26 |

| LNPs without mRNA | 131.6±1.6 | 0.175 ± 0.01 | 1.15±0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).