1. Introduction

Global awareness of environmental issues grew rapidly in the 20th century. A 2024 United Nations (UN) survey on climate action—conducted among over 73,000 people in 77 countries, representing 87% of the world’s population—revealed a strong global consensus: 80% of adults called for more decisive government action to address climate change [

1]. Globally, only a small share of adults (7%) believe their country should not transition at all, while a large majority (79%) want wealthier nations to help poorer countries adapt [

1]. Public perceptions of environmental issues are also shifting in the Netherlands. Almost half (45%) of Dutch young adults (ages 18–24) viewed environmental pollution as a serious problem in 2019, although only 11% considered it a major issue [

2]. In recent years the Eurobarometer showed that 91% of 15–24-year-olds believe that tackling climate change can improve their health and well-being [

3]. Moreover, most young adults (60%) acknowledge the need for a more climate-conscious lifestyle [

4]. However, research highlights a significant gap between these pro-sustainability attitudes and actual behaviour [

5]—for example, more than 60% of 18–25-year-olds reported flying in the past year [

4] (CBS, 2024), few follow a plant-based diet [

4], and many continue to purchase new clothing [

6].

Perspectives on individual responsibility for sustainability vary across regions [

5]. For example, a survey of 1,000 American adults showed half of them believed that businesses should promote sustainable practices, and only a third saw sustainability as a personal responsibility [

7]. Environmental awareness and pro-environmental behaviours are also influenced by individual characteristics such as personality traits and perceptions, and cultural and regional contexts [

8,

9,

10]. The 2024 European Social Survey found that adolescents and young adults who felt personally responsible for addressing climate change reported greater happiness and life satisfaction. In contrast, frequent worry about climate change was associated with lower well-being [

11,

12].

Despite growing awareness, barriers to pro-environmental behaviour persist in everyday settings—at home, school, work, and in public spaces [

5]. These barriers span a range of factors, including informational gaps, psychological perceptions, social norms, and cultural influences [

13,

14]. In Europe, sustainable consumption behaviours are linked to higher levels of environmental knowledge and risk perception [

15]. Moreover, feeling empowered to act sustainably can help reduce environmental distress and foster collective engagement. The United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP)

Global Survey on Sustainable Lifestyles highlights that young adults around the world aspire to contribute to sustainability, but often look for clearer guidance on how to do so effectively [

16]. In general, youth are more likely to adopt sustainable behaviours when they observe others doing the same—demonstrating the influence of social proof [

17].

The present study aims to summarize the perceived barriers to sustainable behaviour and to explore the emotional and psychological needs related to environmental distress freely reported by Dutch young adults (ages 16–35) in two open textboxes. By analysing these written data from a 2023 survey on environmental distress, solastalgia [

18], and climate change-related emotions [

12], we seek to better understand the challenges young adults face when adopting sustainable practices. Additionally, this study investigates the types of support they require to cope with climate-related stress and to empower them to take more proactive environmental actions. In particular, a strong sense of personal responsibility is highlighted as a key factor in reducing anxiety and fostering engagement in sustainability efforts—benefiting both mental well-being and environmental sustainability.

This study addresses two main objectives: (1) to identify barriers and the sense of personal responsibility regarding sustainable behaviour among Dutch young adults, and (2) to examine their emotional and psychological needs concerning distress about the state of the natural environment.

2. Materials and Methods

We used a questionnaire to examine environmental perceptions [

18] (Venhof et al., 2025) and climate change-related emotions [

12] among 1,006 Dutch young adults aged 16–35 (Mean= 25.9, SD= 5.6) of which 51% identified as women. The sample was drawn using stratified sampling based on gender, age, education, and province, and distributed via Flycatcher Internet Research, a company that ensures representativeness through the “Golden Standard” calibration instrument [

19]. Participants provided informed consent and completed digital questionnaires with built-in measures to prevent missing or inconsistent data.

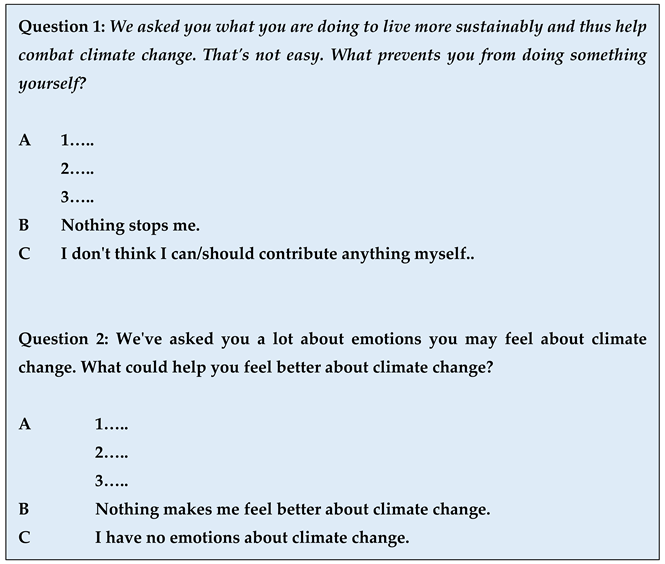

The survey included demographic questions, personality traits (BFI-10), [

20], self-perceived mental and physical health, environmental distress, and climate change-related emotions. Detailed methods are available in Venhof et al. [

18] and Reitsema et al. [

12]. At the end of the survey, two open-ended questions were included. This paper focuses on the results of these questions, which are presented in the text box below. Both open-ended questions invited participants to provide responses in a text box, and it was not possible to skip them. The full Dutch environmental distress questionnaire used in this study is available elsewhere [

21]. Our translation and testing followed accessibility guidelines [

22], and the study was conducted between February 27 and March 9, 2023. Ethical approval was granted by Maastricht University (FHML-REC/2022/130), and participants received a small financial incentive.

Data analysis involved descriptive statistics and correlation analysis using IBM SPSS, with an emphasis on effect sizes rather than p-values [

23,

24]. This study was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research and the Heymans Data Collection Fund, neither of which influenced the study design or outcomes. Further methodological details can be found in Venhof et al. [

18]. All data were transferred by the first author into an Excel file (MS Excel Professional Plus, 2021), and responses were categorized where possible. Irrelevant or off-topic answers were removed.

3. Results

Dutch young adults (n = 1,006) responded to two questions: one addressing their perceived barriers to sustainable living, and the other exploring their emotional needs connected to distress about the state of the natural environment. Many participants answered using an open text field (42%, 426/1006), although most (58%, 580/1006) selected from fixed answer categories (“B”/”C”). Among those who used the open text fields, many provided multiple responses: 26% (257/1006) gave two answers, and 12% (125/1006) provided three. Of the total 807 open answers, approximately 7% (60/1006) were judged irrelevant by the authors.

Regarding personal barriers, nearly half of the participants stated that they were already doing what they could (46%, 463/1006). One in six (13%, 129/1006) believed they were not responsible for contributing to pollution and a small number (3%, 29/1006) identified others—such as industry, government, or other countries—as responsible for sustainable action. Only a few (4%) argued that the individual impact was very limited.

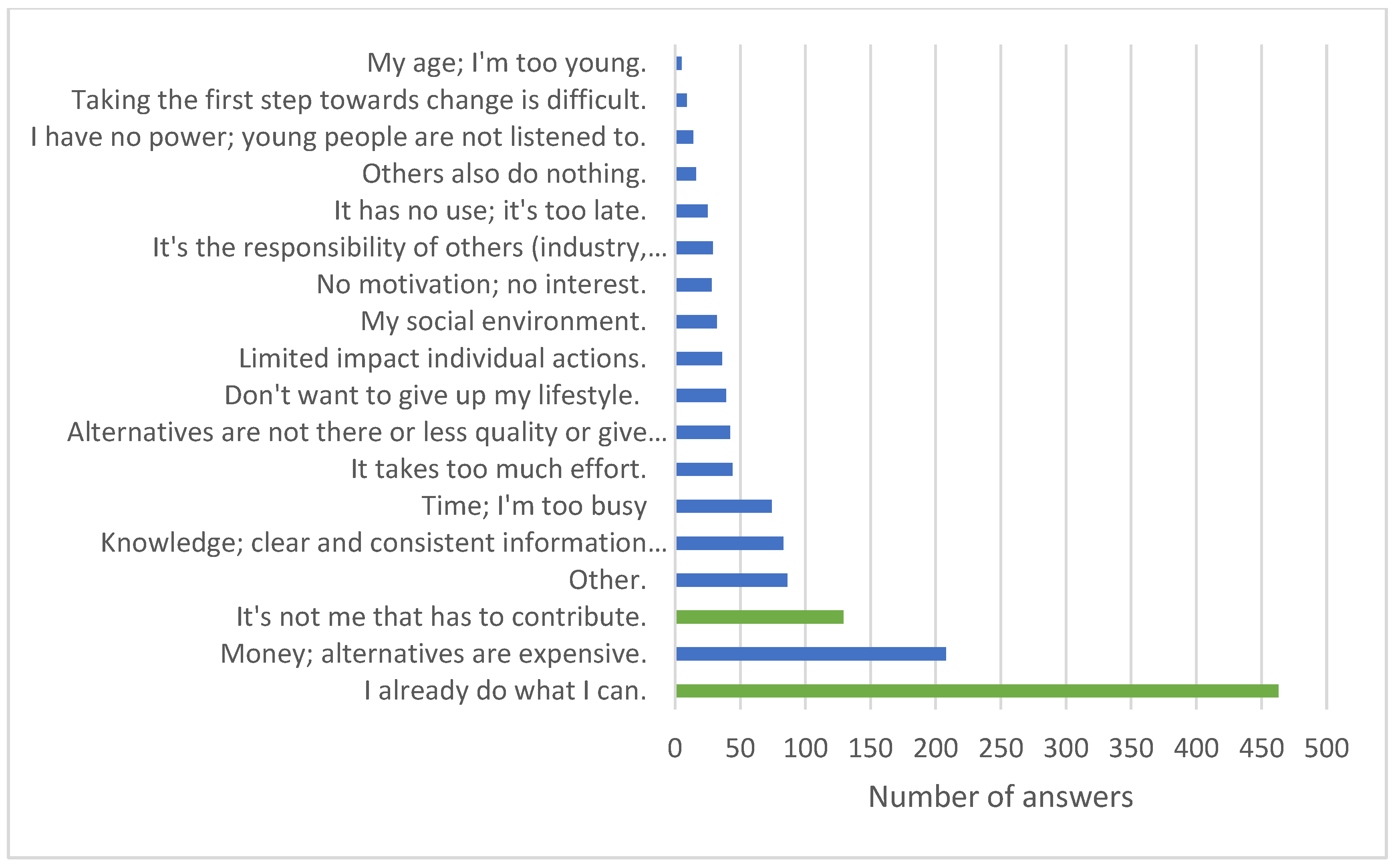

The most frequently mentioned barriers to sustainable living were lack of money (21%), knowledge (8%), and time (7%). Additionally, some young adults (3%) reported that sustainable behaviour was pointless. All opinions on sustainable behaviour are summarized in

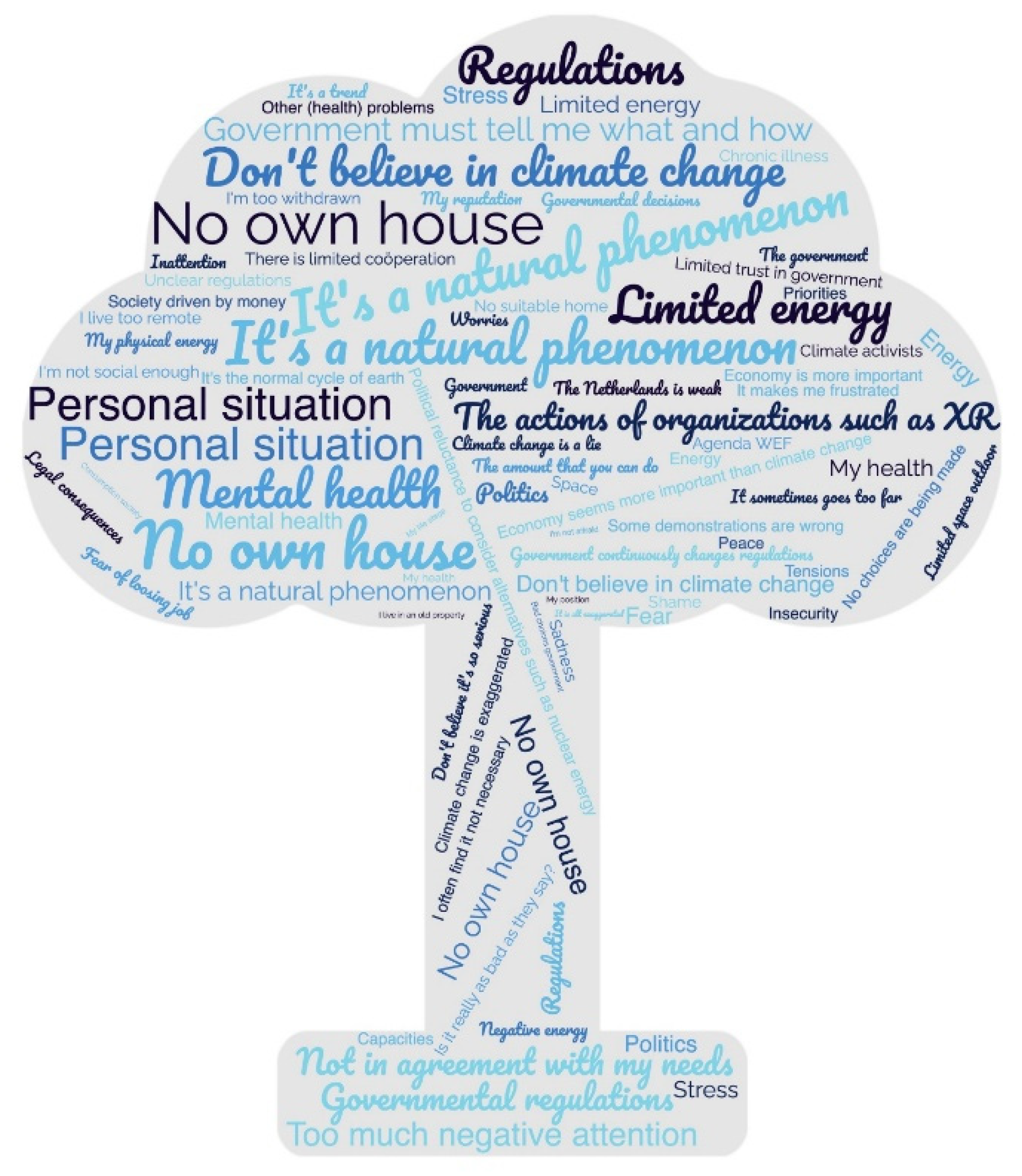

Figure 1 below. The category ‘other’ (9%, 86/1006) included a variety of responses, as detailed in

Figure 2. The most common answers in this category concerned mental wellbeing and energy levels (n = 21), governmental decisions and regulations or politics (n = 18), denial (n = 12), and housing issues (n = 8).

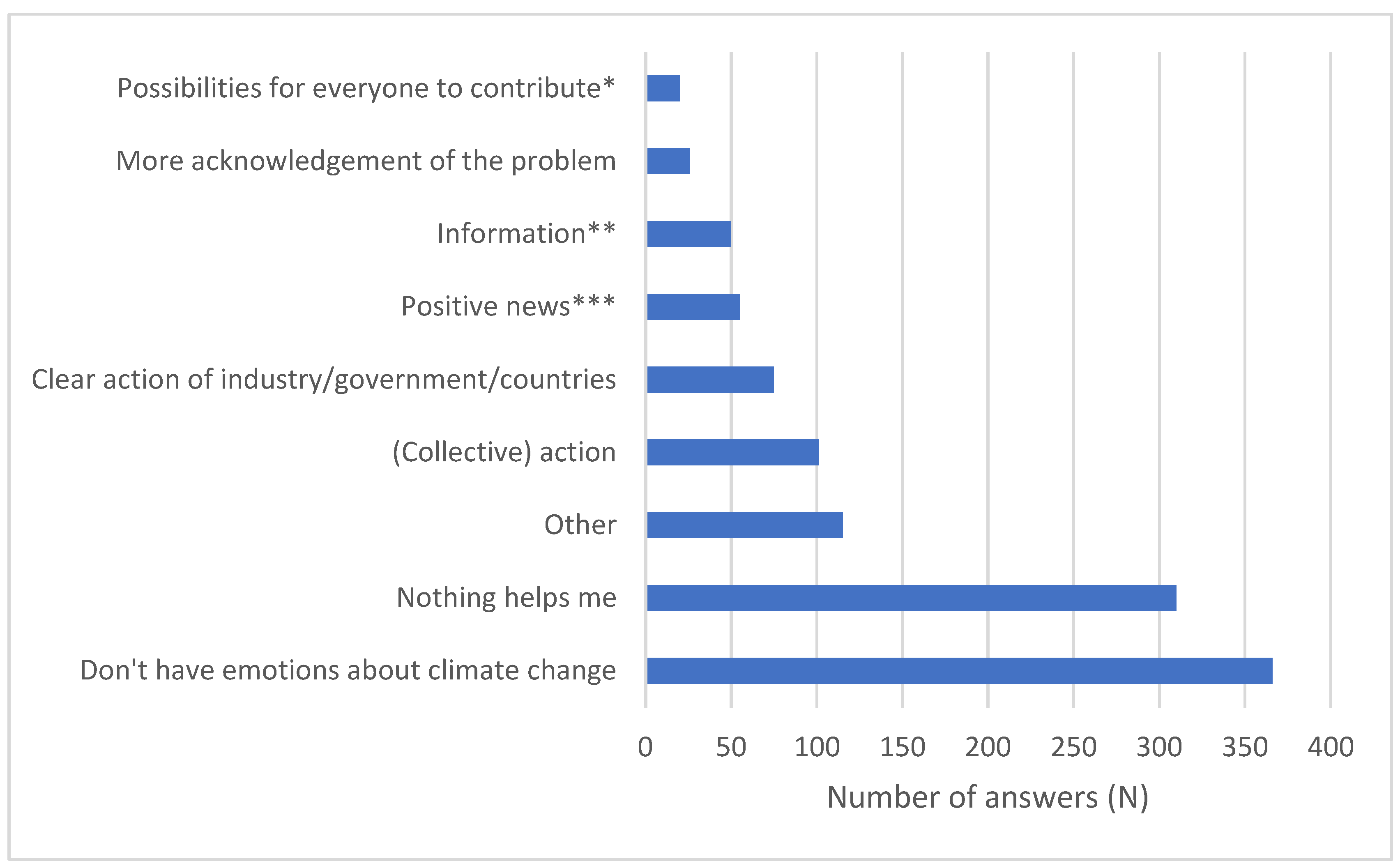

Our second question addressed the perceived needs of young adults aged 16–25 to cope better with climate change and related issues. Two-thirds of the participants selected fixed answers (673/1006, categories B/C) and in this study we focus on the one-third of adults who provided at least one open-ended response (33%, 333/1006). Among them, 9% (88/1006) gave two answers, and 4% (38/1006) provided the maximum of three open answers. Of the total 459 open answers, 13 were deemed irrelevant because they did not pertain to the question. The results are presented in

Figure 3.

One third of young adults (31%, 307/1006) said there was nothing that could make them feel better about climate change, suggesting despair, and a similar share had no feelings about climate change (36%, 366/1006), suggesting indifference. A subset of young adults desired more action at the personal and social/community level (10%) and more action from the industry, government, and/or other countries (8%, 75/1006), as they felt such organizations had to acknowledge the problem more (3%). Also positive news was felt to be needed, with celebration of actual improvements and progress (6%).

4. Discussion

We identified a range of barriers to sustainable behaviour in a representative sample of Dutch young adults aged 16 to 35 years. Nearly half (46%, 463/1006) reported that they were already doing what they could to help mitigate climate change. The most frequently mentioned obstacles to sustainable living were financial constraints (21%), lack of knowledge (8%), and limited time (7%). Notably, one third of young adults (31%, 307/1006) indicated that nothing could make them feel better about climate change and related issues (suggesting despair), while another third (36%) reported having no particular feelings about these problems (suggesting indifference). About 10% expressed a need for more action both at the personal and community levels, and 8% called for greater efforts from industry, government, or other countries. Furthermore, 6% highlighted the importance of positive news and the celebration of real progress.

It is widely acknowledged that empowering youth to reduce energy use requires a combination of education, incentives (financial and structural support), and enabling infrastructure. Our findings align with previous research demonstrating that financial costs remain a key barrier to sustainable consumption among motivated young adults [

25]. This suggests opportunities to encourage reduced consumption of items like clothing and air travel, and to promote experiences instead—thereby helping youth save money and improve well-being and security [

26,

27]. However, adolescence and early adulthood are life stages characterized by pro-consumption behaviours tied to identity formation through belongings, fashion, and gadgets [

28]. Hence, investments in information and education remains needed—such as clear communication about recycling rules, awareness of greenwashing in clothing, and guidance on sustainable diet choices (e.g., reducing meat and dairy consumption), which are among the most impactful behaviours. Infrastructure improvements—from recycling bins to accessible public transport and safe cycling networks—are equally important, as are policies that make sustainable choices the convenient ones [

29].

More research is needed on so-called “bottleneck” behaviours, where young people experience cognitive dissonance by recognizing the negative impact of flying or eating meat but feeling unable or unwilling to change these habits [

4,

6,

12]. Dutch studies indicate that social strategies like vegan tasting sessions, peer cooking demonstrations, and linking diet to personal health and fitness may help facilitate dietary shifts among youth [

30]. Similarly, social media influencers and trends can motivate sustainable behaviour, from diet to energy-saving and alternative travel options, potentially helping youth reduce costs (compared to fast-fashion promotion on social media). The fact that half of our participants already feel they do what they can raises concerns about “tokenism”—the phenomenon where people perform a few obvious actions (like turning off taps or lights) and then consider their responsibility fulfilled [

31]. This mindset can hinder further actions such as unplugging idle electronics, air-drying clothes, or buying sustainable clothing. The perception that “my effort is too small to matter” may discourage further action, suggesting that society should foster sustainable community norms, personal incentives (e.g., cost savings), and ease of use through technologies like smart thermostats, motion-sensor lighting, solar panels, and accessible second-hand clothing exchange. However, beyond technological solutions and behavioral interventions, it is essential to invest in inclusive processes that empower young people to meaningfully participate in climate decision-making and community-based initiatives, thereby enhancing their sense of efficacy and belonging [

32].

Strengths and Limitations

Although this study was exploratory and limited by only including two open-ended questions, a key strength lies in the fact that all 1006 participants from a representative sample responded. Most engaged thoughtfully and seriously, with many (33%) providing at least one open-ended response. This level of engagement enriches the findings and provides valuable insights into young adults’ perspectives.

A notable limitation is the inclusion of two fixed-answer options alongside the open-ended questions. Positioned at the end of a longer questionnaire, respondents may have chosen these fixed options for convenience rather than investing time in open-ended answers, potentially leading to rushed or less thoughtful responses. Additionally, the second question was negatively framed, assuming respondents experienced environmental distress and negative emotions, which may have biased answers. These factors highlight potential data biases and underscore the need for further research using more balanced question formats and response options.

Although the open-ended questions were not the main focus of our study, they offer valuable inspiration for future qualitative research on perceived barriers and needs in environmental care among young adults. The willingness of many participants to respond despite survey length suggests that environmental change is an important issue to them. Overall, the results show that while many Dutch young adults recognize the importance of sustainable behaviour, significant barriers such as financial constraints, limited knowledge, and time impede their actions.

5. Conclusions

Perceived limits to sustainable behaviour are not only practical (e.g., financial or time-related), but also emotional, underscoring the need for integrative, positively framed, strategies that address both logistical, social, and psychological barriers. By identifying these key barriers and needs, this study informs targeted strategies to promote sustainable behaviour and alleviate environmental distress among Dutch young adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V. (Valesca S.M. Venhof); methodology, V.V.; formal analysis, V.V.; investigation, V.V.; resources, V.V., B.J. (Bertus F. Jeronimus); writing—original draft preparation, V.V.; writing—review and editing, V.V. and B.J.; visualization, V.V.; supervision, B.J.; project administration, V.V.; funding acquisition, B.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

B.J. was supported by the Talent Programme of the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research (Gravitation 024.005.010) and the Heymans Data Collection Fund to pay for the Flycatcher research agency for their programming and distribution of the survey, and the small compensation that our participants received in the form of saved points.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Faculty of Health, Medicine, and Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee (FHML-REC) of Maastricht University (FHML-REC/2022/130, 20 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Talent Programme of the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research for the funding of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- UNDP. (2024). People’s Climate Vote 2024. United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved March 24, 2025. Available online: https://www.undp.org/press-releases/80-percent-people-globally-want-stronger-climate-action-governments-according-un-development-programme-survey.

-

CBS (2019). Environmental Concerns Among Youth. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2019/48/45-percent-of-young-people-see-pollution-as-a-problem.

- European Union. (2022). Special Eurobarometer: Europeans see climate change as top challenge for the EU. IEU Monitoring. Retrieved May 27, 2025. Available online: https://ieu-monitoring.com/editorial/special-eurobarometer-europeans-see-climate-change-as-top-challenge-for-the-eu/368119.

- CBS, Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. (2024). Jongeren vinden minder dan ouderen dat ze zelf klimaatbewust leven. Retrieved May 27, 2025. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2024/13/jongeren-vinden-minder-dan-ouderen-dat-ze-zelf-klimaatbewust-leven.

- Cantillo, J., Astorino, L. & Tsana, A. Determinants of pro-environmental attitude and behaviour among European Union (EU) residents: differences between older and younger generations. Qual Quant (2025). [CrossRef]

- Geeris, J., Roumen, J., Ivens, A., & Honkoop, H. P. (2023). Monitor Duurzaam Leven 2023: Hoe duurzaam leeft Nederland? Monitoring van 98 duurzame keuzes en openheid tot duurzaam gedrag Milieu Centraal. Retrieved May 27, 2025. Available online: https://www.milieucentraal.nl/media/l0zliq5j/milieu-centraal-2023-monitor-duurzaam-leven.pdf.

- Statista. (2022). Responsibility for sustainability in the U.S. 2022. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1373204/who-should-implement-sustainable-practices-usa/.

- Baiardi, D. (2023). What do you think about climate change?. Journal of Economic Surveys, 37(4), 1255-1313. [CrossRef]

- Boermans, D. D., Jagoda, A., Lemiski, D., Wegener, J., & Krzywonos, M. (2024). Environmental awareness and sustainable behavior of respondents in Germany, the Netherlands and Poland: A qualitative focus group study. Journal of Environmental Management, 370, 122515. [CrossRef]

- Brosch, T., & Steg, L. (2021). Leveraging emotion for sustainable action. One Earth, 4(12), 1693-1703. [CrossRef]

- Martin, G., Roswell, T., & Cosma, A. (2024). Exploring the relationships between worry about climate change, belief about personal responsibility, and mental wellbeing among adolescents and young adults. Wellbeing, Space and Society, 6, 100198. [CrossRef]

- Reitsema A., Venhof V., Becht A., Jeronimus B. (2025). Environmental Psychology. Under review.

- Dioba, A., Kroker, V., Dewitte, S., & Lange, F. (2024). Barriers to pro-environmental behavior change: A review of qualitative research. Sustainability, 16(20), 8776. [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W., Whitmarsh, L., Steg, L., Böhm, G., & Fisher, S. (2019). Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Global environmental change, 55, 25-35.

- Saari, U. A., Damberg, S., Frömbling, L., & Ringle, C. M. (2021). Sustainable consumption behavior of Europeans: The influence of environmental knowledge and risk perception on environmental concern and behavioral intention. Ecological Economics, 189, 107155. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2009). Global Survey on Sustainable Lifestyles. Available online: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/one-planet-network/global-survey-sustainable.

- Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management. (2023, February 28). Behavioural strategy for citizens and the circular economy. Government of the Netherlands. Retrieved May 27, 2025. Available online: https://www.government.nl/documents/reports/2023/02/28/behavioural-strategy-for-citizens-and-the-circular-econom.

- Venhof, V.S.M., Jeronimus, B.F. & Martens, P. Environmental Distress Among Dutch Young Adults: Worried Minds or Indifferent Hearts?. EcoHealth (2025). [CrossRef]

- CBS (2022). Dashboard bevolking. Actuele cijfers over de bevolking van Nederland, ook per gemeente. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-bevolking.

- Rammstedt, B. J., O.P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 203–212. [CrossRef]

- Venhof, V. (2024, September 3). Nederlandse Omgevings Distress Vragenlijst. In: Environmental distress in Dutch young adults. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S., C. F. Royse and A. S. Terkawi (2017). Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi journal of anaesthesia 11(Suppl 1): S80-S89. [CrossRef]

- Richard, F. D., Bond, C. F., & Stokes-Zoota, J. J. (2003). One hundred years of social psychology quantitatively described. Review of General Psychology, 7(4), 331–363. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1990). Things I have learned (so far). American Psychologist 45, 1304–1312.

- Kreuzer, C., Weber, S., Off, M., Hackenberg, T., & Birk, C. (2019). Shedding light on realized sustainable consumption behavior and perceived barriers of young adults for creating stimulating teaching–learning situations. Sustainability, 11(9), 2587. [CrossRef]

- Joyner Armstrong, C. M., Connell, K. Y. H., Lang, C., Ruppert-Stroescu, M., & LeHew, M. L. A. (2016). Educating for sustainable fashion: Using clothing acquisition abstinence to explore sustainable consumption and life beyond growth. Journal of Consumer Policy, 39(4), 417–439. [CrossRef]

- Seegebarth, B., Peyer, M., Balderjahn, I., & Wiedmann, K.-P. (2016). The sustainability roots of anticonsumption lifestyles and initial insights regarding their effects on consumers’ well-being. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 50(1), 68–99. [CrossRef]

- Ziesemer, F., Hüttel, A. & Balderjahn, I. (2021). Young People as Drivers or Inhibitors of the Sustainability Movement: The Case of Anti-Consumption. J Consum Policy 44, 427–453. [CrossRef]

- DS Smith. (2022, August 18). DS Smith surveys: Generational split found internationally with young consumers least confident about recycling. Retrieved May 27, 2025. Available online: https://www.dssmith.com/us/media/newsroom2/2022/9/ds-smith-surveys-generational-split-found-internationally-with-young-consumers-least-confident-about-recycling.

- Raghoebar, S., Mesch, A., Gulikers, J., Winkens, L. H., Wesselink, R., & Haveman-Nies, A. (2024). Experts’ perceptions on motivators and barriers of healthy and sustainable dietary behaviors among adolescents: The SWITCH project. Appetite, 194, 107196. [CrossRef]

- Dioba, A., Kroker, V., Dewitte, S., & Lange, F. (2024). Barriers to pro-environmental behavior change: A review of qualitative research. Sustainability, 16(20), 8776. [CrossRef]

- Ingaruca, M., Richard, N., Carman, R., Savarala, S., Jacovella, G., Baumgartner, L., … & Flynn, C. (2022). Aiming Higher: Elevating Meaningful Youth Engagement for Climate Action. United Nations Development Program: New York, NY, USA.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).