Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the main views of Indonesian stakeholders on multipurpose shipyards?

- What benefits do stakeholders see from the combination of shipbuilding, repair, and recycling?

- What challenges can stakeholders expect in the management of multipurpose shipyards?

- How can stakeholder traits and creative dynamics influence the possible acceptance of this model?

2. Literature Review

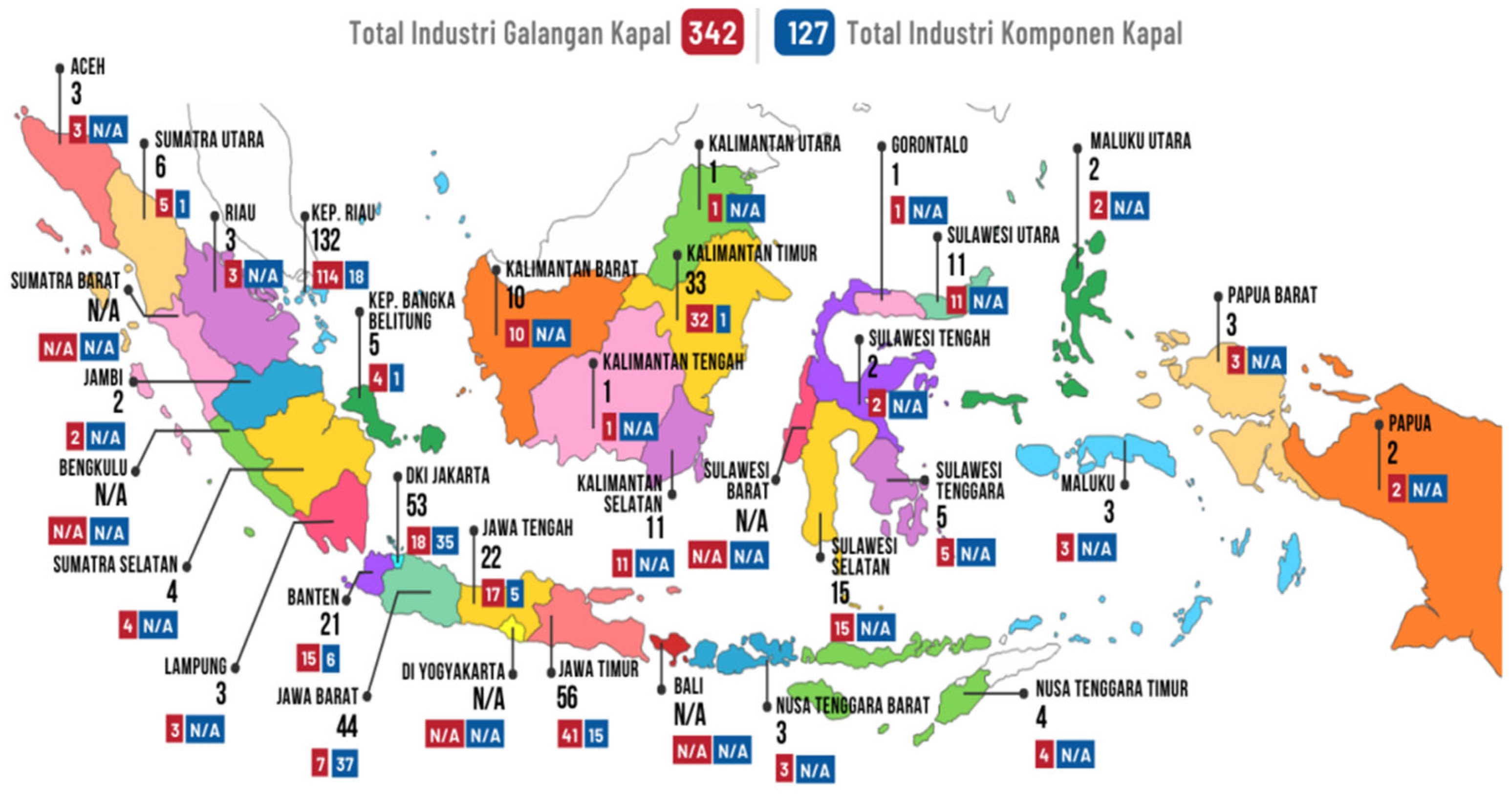

2.1. Indonesia Shipbuilding Overview

2.1.1. Economic Significance

2.1.2. Infrastructure Challenges

2.1.3. Regulatory Environment

| Regulatory level | Key regulation(s) | Features / Requirements | Relevance to Multipurpose Shipyards | Status in Indonesia | Implementation Gaps / Challenges |

| International (IMO) | Hong Kong International Convention (HKC) | Requires Inventory of Hazardous Materials (IHM), Ship Recycling Plan, certified facilities [16,17] | Gold standard for safe recycling; aligns with national rules | Not yet ratified; enters into force globally June 2025 [6] | Indonesia not party; domestic law lags HKC; pilot projects only [18] |

| MARPOL 73/78 [19] | Limits oil and pollutant discharges from ships | Applies to environmental compliance in yard operations | Ratified by Indonesia [20] | Enforcement and monitoring capacity varies across regions | |

| Regional | ASEAN Marine Environmental Law/Cooperation | Marine pollution prevention, transboundary standards, cooperative action | Encourages harmonised approaches and regional benchmarks | Indonesia participates, but implementation is uneven[21] | National legal harmonisation slow; variable local uptake |

| Basel Convention [22] | Controls the cross-border movement of hazardous waste, applies to shipbreaking | Mandates the safe export/import of hazardous waste from ships | Ratified and in force [23] | Some weak points in national enforcement and tracking | |

| National (Indonesia) | PM 29/2014 [24] | Prevents marine pollution, regulates ship recycling & hazardous material handling | Main legal framework for shipyard pollution control | In force; updated by the Ministry of Transportation No. 24/2022 | Enforcement is inconsistent, especially outside Java/Batam |

| Law No. 17/2008 (Shipping), Gov. Reg 21/2010, GR 101/2014 [25] | Environmental impact assessment (AMDAL), hazardous waste management, operational licensing | Determines site approval, waste protocols, and permits | Enacted; national coverage | Limited regional enforcement and monitoring capacity [15] | |

| Local / Provincial | Regional zoning & environmental licensing | Site-specific permits, zoning for shipyard activity, local AMDAL requirements [26] | Determines legal operation and environmental approval | Varies by region (often strict in Java, weaker in eastern provinces) [1] | Legal patchwork creates uncertainty, slows investment |

2.2. Shipyard Operational Model

2.2.1. Regulatory Environment

2.2.2. Multipurpose Shipyard Concept

2.2.3. Hybrid and Integrated Approaches

2.3. Stakeholder Perspectives in Maritime Industries

2.3.1. Environmental and Safety Considerations

2.3.2. Economic and Operational Factors

2.3.3. Regulatory Compliance and Governance

2.3.4. Regional Implementation Variations

2.4. Theoretical Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participant Selection and Sampling Strategy

3.3. Data Collection

- Based on the wording, phrasing, and emphasis of the stakeholders, researchers independently examined and analysed the raw textual material to extract relevant codes.

- These codes were then grouped into generic categories showing linked trends and stakeholder concerns. This approach is described by axial modelling.

- Theme Consolidation Following several rounds of discussion and synthesis, the codes were organised into five main themes closely related to the research topic and the stories of the stakeholders.

- Market demand themes concern the feasibility, the client's interest, and the possibility of monetary loss.

- Workforce development themes stress the readiness of skills, human resources, and occupational health and safety (OHS).

- Regulatory compliance themes in the context of environmental and recycling laws include government support, enforcement, and clarification.

- Environmental themes include opinions on sustainable practices, environmentally acceptable recycling methods, and pollution control.

- Operational efficiency theme ideas are on layout design, work division, infrastructure preparation, and time-saving strategies.

4. Result

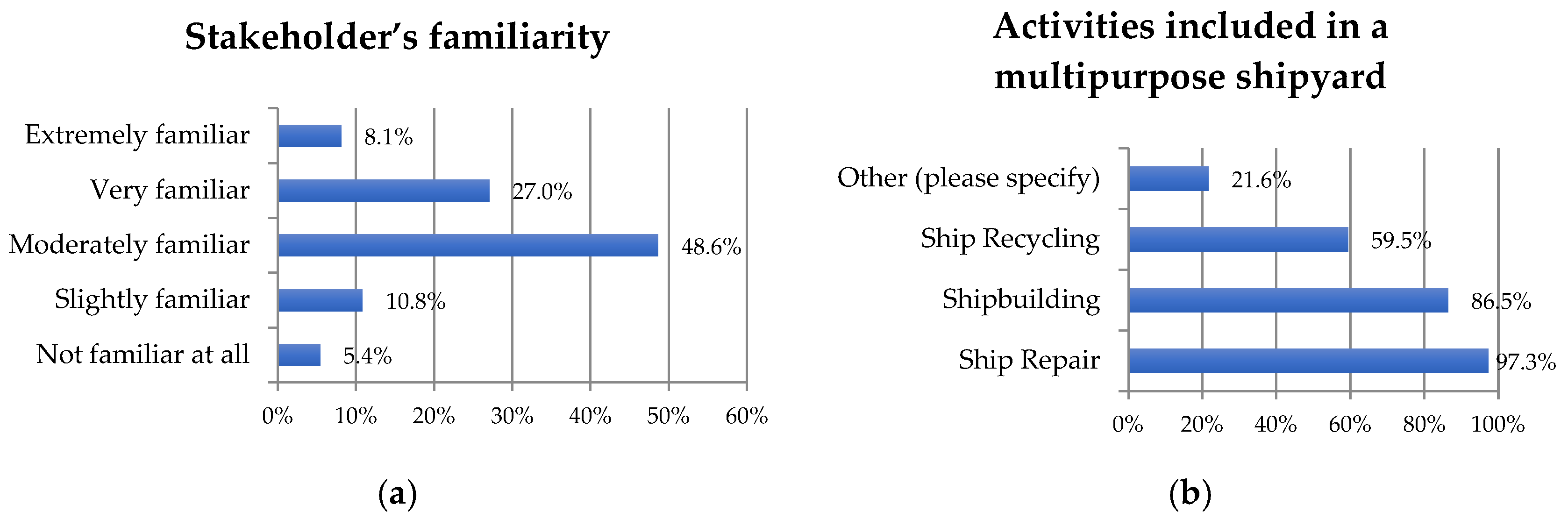

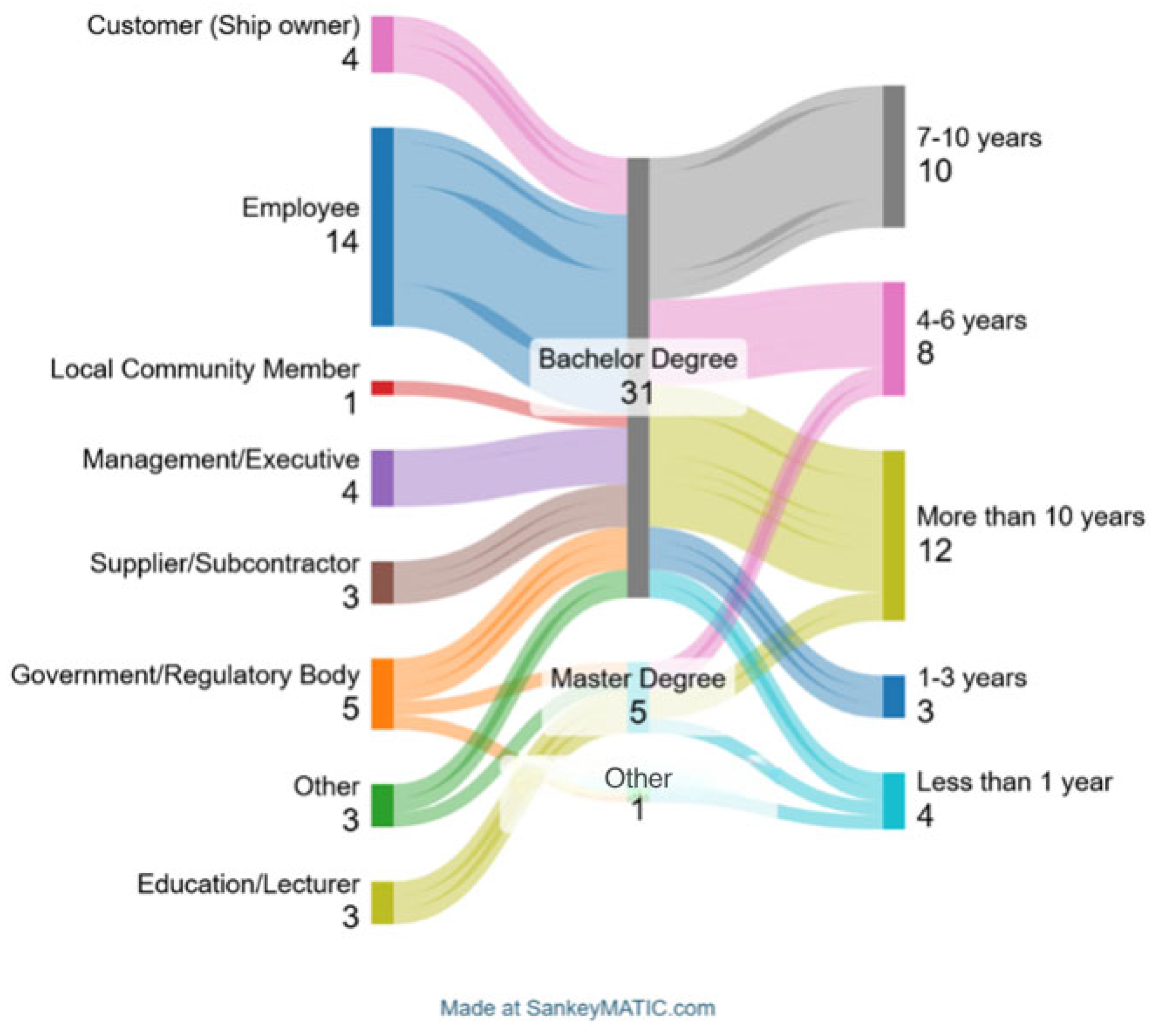

4.1. Stakeholder Profile

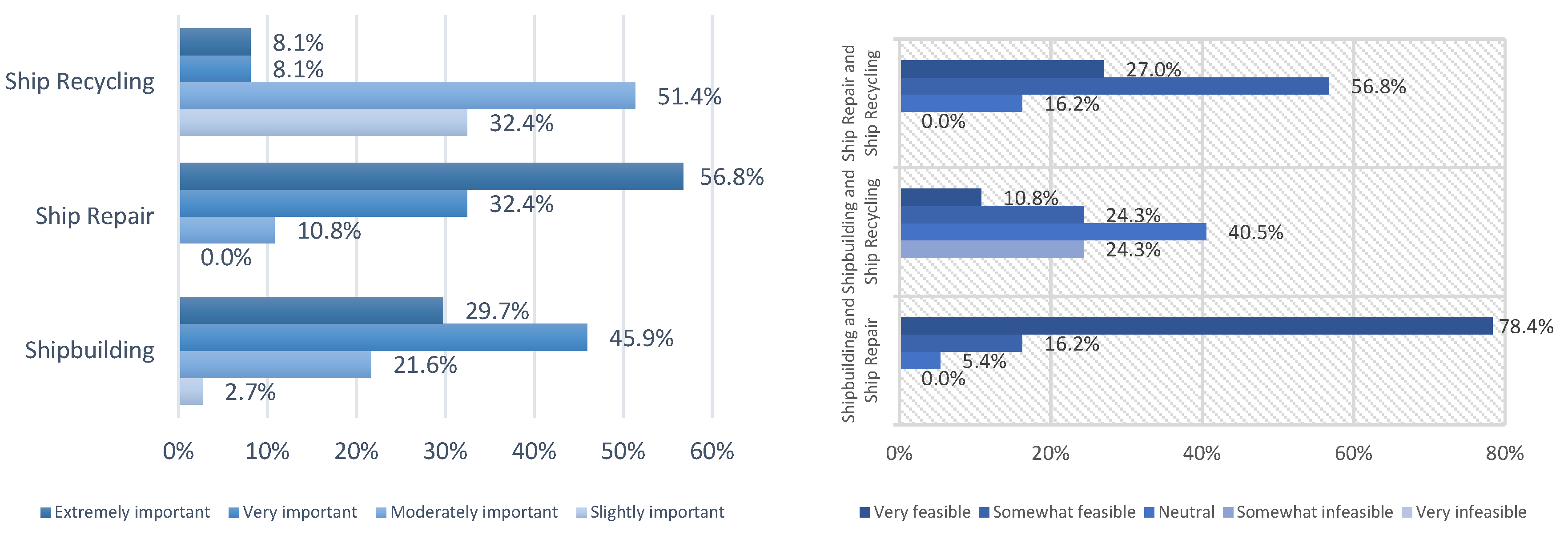

4.2. Stakeholder Perception of the Multipurpose Shipyard Concept

“A multipurpose shipyard could become a model for sustainable maritime development, provided it is supported by strong regulations.”

“It would be efficient in working time and increased financial income if we can ensure adequate space and smart layout.”

“We still need evidence and operational proof before we can scale the model nationwide.”

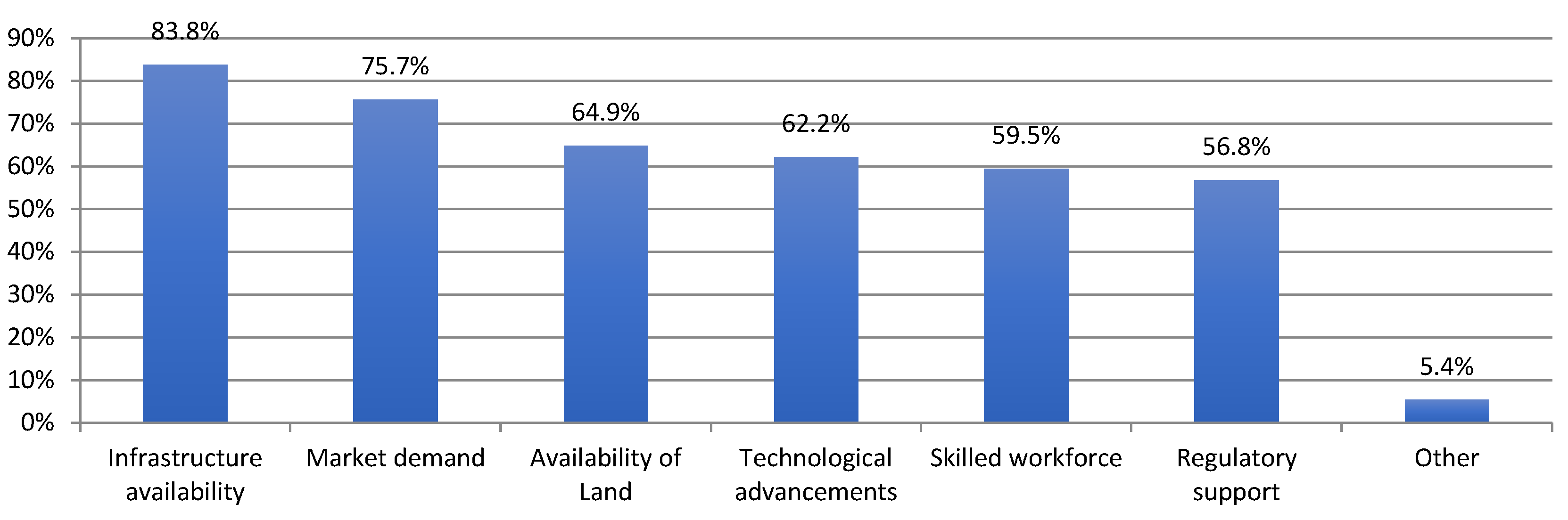

4.3. Feasibility of Integration

"Combining these two functions will improve financial turnover and efficiency due to shared dock and machinery use."

"It is risky to conduct ship recycling near construction; clear environmental boundaries and protocols must be ensured."

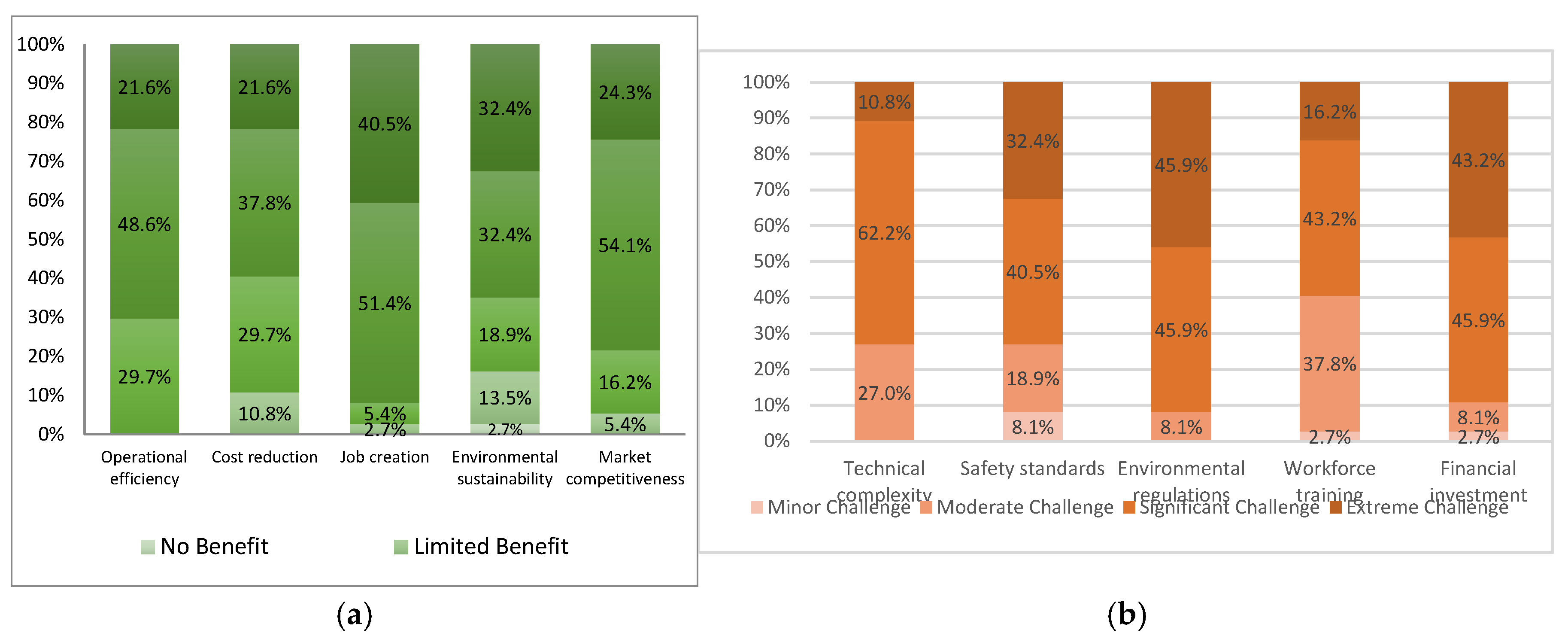

4.4. Stakeholder Perceptions of Benefits and Challenges

"Green recycling requires a whole new mindset, equipment, and enforcement. Without that, we risk undermining our environmental goals."

"The biggest challenge is enforcement, without proper oversight, recycling becomes a liability rather than an opportunity."

"The financial risks are too high unless we receive support from both the government and the market."

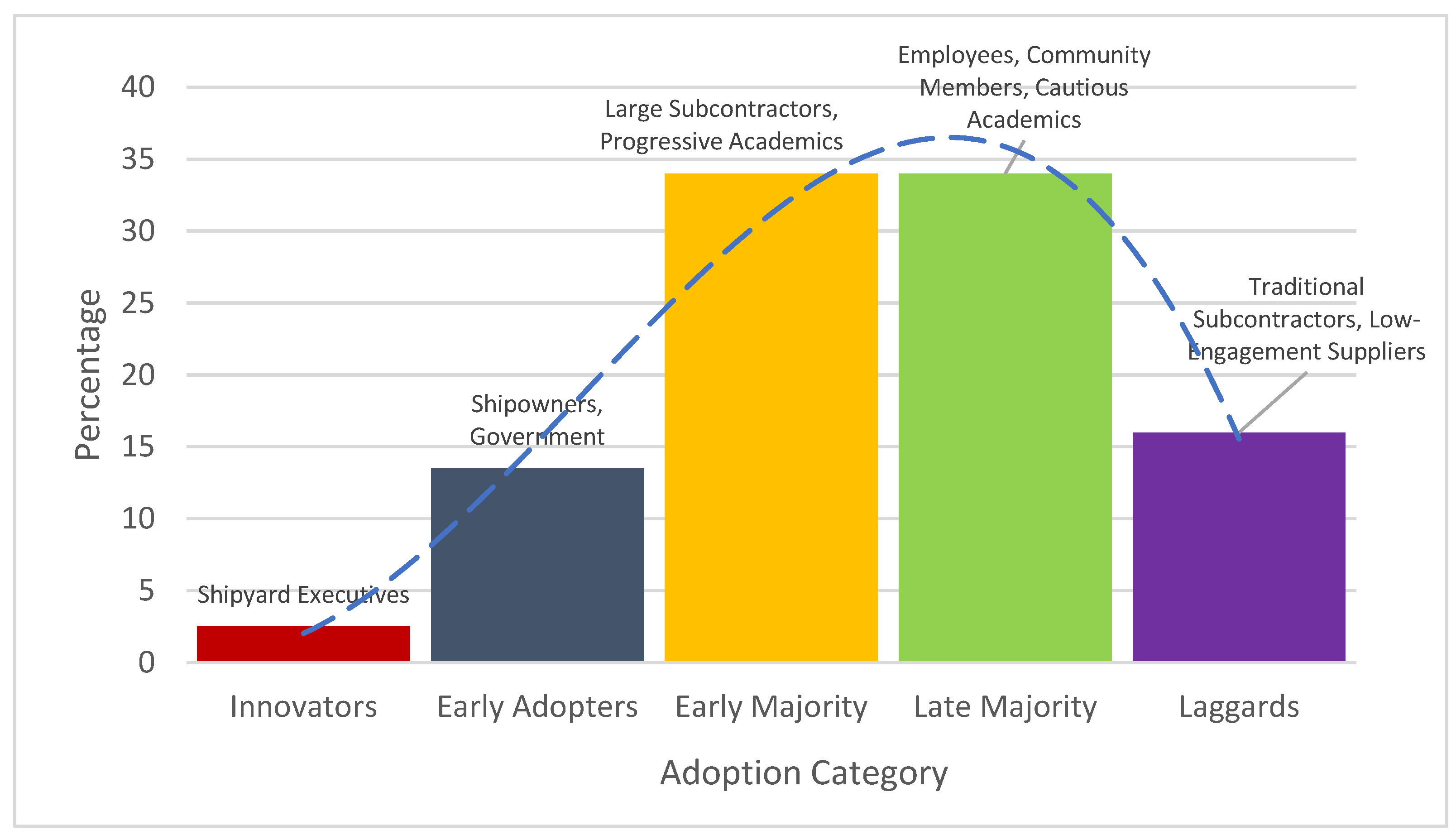

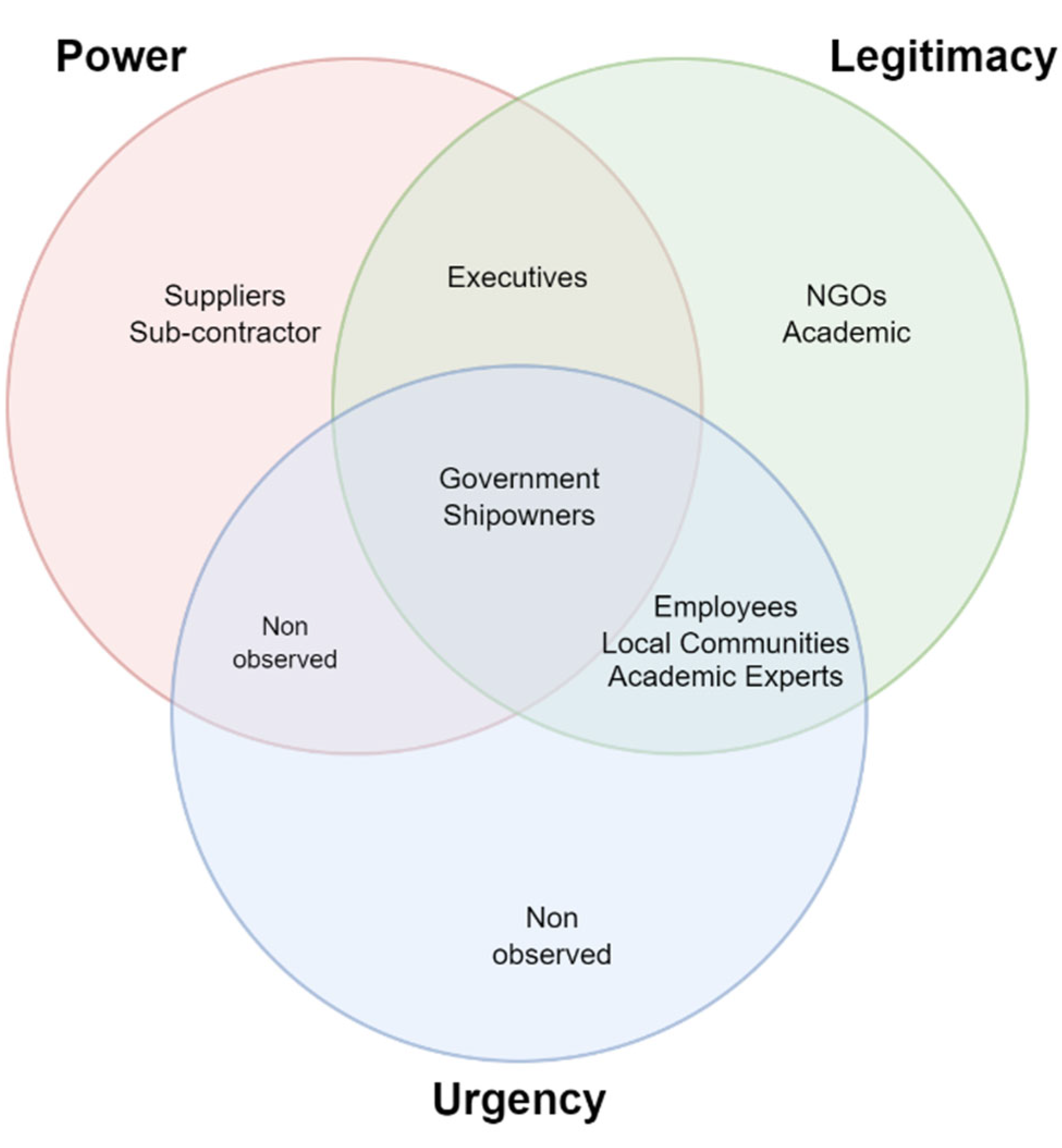

4.5. Stakeholder Classification and Salience Analysis

"Strong collaboration between government and regulators is essential to ensure smooth integration of all activities."

"Maintaining competitiveness depends on enforcing ship recycling rules and guaranteeing quality, safety, and innovation."

"This is acceptable as long as the shipyard has adequate space and management separation for each function."

"We need a clear concept and training to safely integrate new operations. Human resource improvement is essential at all levels."

"We need strong justification and evidence to promote integration. There are technical and training gaps that must be addressed."

“Integrating operations needs targeted training across all levels, staff, subcontractors, and management.”

“Shipyards must prepare a structured plan for handling pollution and material flow, it's not just a matter of engineering but of regulation.”

4.6. Innovation Adoption and Diffusion Among Stakeholders

"Understanding market dynamics and operational composition is essential; each activity must match demand, feasibility, and risk. We've already begun adjusting our shipyard operations to reflect this integration." – Shipbuilding Executive.

"This transformation must align with long-term demand, risk management, and the strategic purpose of each operation within the yard." Shipowners

“Shipyards must prepare a structured plan for handling pollution and material flow, and it's not just a matter of engineering but of regulation." Government official.

"Integration is challenging but possible if done with proper planning and skill development." Shipyard Employee.

5. Discussion

5.1. Integrating Shipyard Services: Stakeholder Perspectives in Context

5.2. Stakeholder Dynamics: Salience and Innovation Diffusion

- Relative Advantage: Stakeholders believe the integrated approach offers better efficiency, cost savings, and broader service coverage. Should the idea be implemented, this enormous perceived benefit suggests that possible adopters, shipyard companies, and investors would see a noticeable improvement over the current status. Our research revealed a consistent consensus that operational performance will improve, which is significant since innovations with economic or performance benefits are more likely to be adopted. Global observations indicate that integrated maritime services are driven by an urgency to optimise operations and remain competitive.

- Compatibility: Stakeholders argue that multipurpose shipyards may not meet the requirements of the Indonesian industry. The concept suits the archipelagic setting by offering dispersed, full-service hubs that align with Indonesia's geography and support its national objectives of maritime self-sufficiency and logistics. Integration calls for changing the operation of shipyards (tighter environmental regulations, altered workflow management), which could not suit current approaches. Some participants stated that recycling is not ideal due to the shipyard culture and structure, which necessitate significant modifications. Therefore, while a multipurpose yard's objectives align with Indonesia's maritime vision, their execution requires new organisational strategies. Pilot studies demonstrating that local yards can adapt and maintain current work patterns, e.g., on-time ship deliveries while recycling, could help foster compatibility.

- Complexity: As indicated, stakeholders find the innovation complicated. Often emphasised were technical and management complexity. High perceived complexity produces uncertainty and failure dread, which hinders diffusion. Many responders suggested progressive adoption to simplify innovation by breaking it down into manageable pieces. According to Rogers et al. (2014), simplifying the innovation or providing thorough education can help. Breaking the concept into phased components (e.g., start with repair + limited recycling) lowers the initial complexity barrier. Complexity issues highlight the need for knowledge-sharing: exploring international best-practice locations, exchanging knowledge, and possibly engaging consultants who have constructed integrated yards elsewhere would simplify the process for Indonesian stakeholders.

- Trialability and Observability: These traits are significant given our cautious optimism in our outcomes. Many stakeholders stressed the necessity for evidence, pilot initiatives, and proof of concept. Trialability (small-scale testing) and observability (seeing real results) are desired. As a pioneering green recycling effort, Batam and Cilegon shipyards give demonstrable results to others. Our respondents' interest in that example (some were aware of it through industry networks) suggests that a successful trial can create community confidence, a key step to diffuse from early adopters to the early majority. We propose that government and industry work on one or two regional multipurpose shipyard demonstration projects. These pilots could persuade sceptical or risk-averse stakeholders by carefully monitoring and publicising their performance (e.g., cost savings, job creation, compliance track record). The innovation in Indonesia is likely to follow Rogers' model: initial champions (possibly a few forward-thinking yard operators with government support) will implement and validate the concept, and then more followers will adopt it as benefits become apparent and uncertainty decreases.

5.3. Implications for Policy and Sustainable Implementation

- Policy and Regulatory Framework: The regulatory framework requires an upgrade. Indonesia should ratify and implement the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships to expedite the development of ship recycling regulations. Explicit rules would alleviate stakeholder apprehensions regarding environmental degradation and create equitable conditions for shipyard operators. Optimising permission procedures and providing centralised regulatory approval for integrated operations will diminish bureaucratic obstacles that hinder yard expansion, as specific stakeholders have cited regulatory uncertainty as a potential risk for delays or non-compliance. Policymakers should establish a maritime industrial working group of industry stakeholders to revise regulations and train enforcement authorities to supervise complex shipyard operations.

- Infrastructure and Investment Support: Given high capital costs and infrastructure needs, government investment facilitation will drive success. Financial incentives could include tax discounts on capital equipment for ship recycling facilities, as well as low-interest loans and grants for yards updating their infrastructure to support multipurpose shipyard activities. Public-private collaborations can help create green recycling zones near shipyards. A shipyard cluster or estate where infrastructure can be pooled (e.g., a centralised hazardous waste treatment plant serving several shipyards) is one realistic idea from the feedback. Cluster models and shared investment reduce costs and comply with regulations.

- Environmental and Safety Measures: Implement robust environmental and occupational safety regulations to ensure sustainability. This requires ship recycling yards to possess ISO 30000 certifications and to have appropriate waste management systems in place for oil, asbestos, scrap steel, and other materials. Certification, waste management, and transparent oversight are crucial to establishing trust and positioning Indonesia as a leader in sustainable ship recycling. Multipurpose shipyards enable resource recovery, material reuse, and operational innovation, advancing the circular economy and cost efficiency.

- Stakeholder Engagement and Integration: Participation in local forums and multi-stakeholder partnerships will build credibility, address concerns, and support implementation.

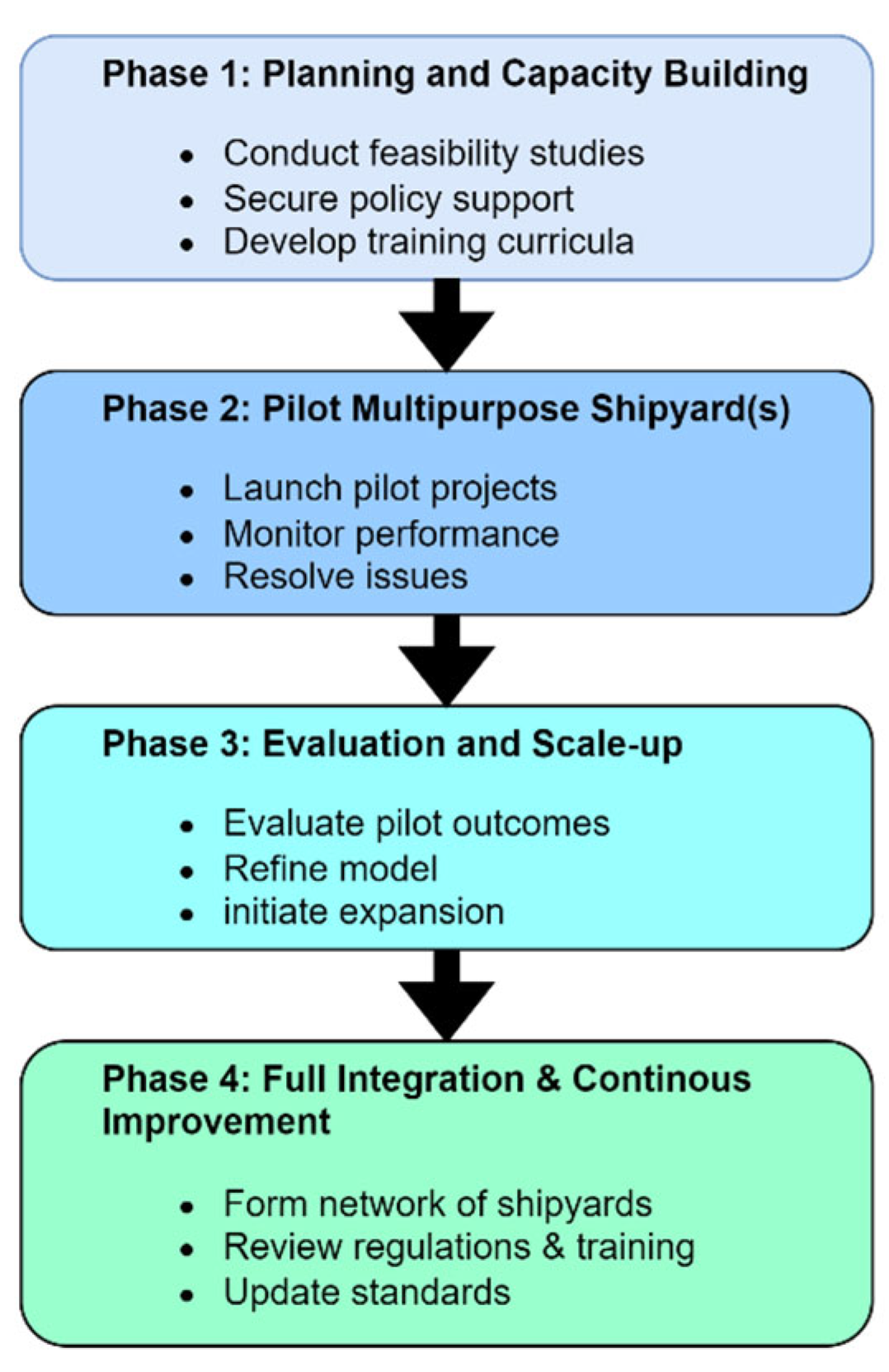

- Phased Implementation Roadmap: Data and theory support a phased implementation roadmap. We offer a staged implementation roadmap (see Figure 9) to guide the transition:

- Phase 1: Planning and Capacity Building. Assess feasibility, revise policy, develop skills, and select pilot sites.

- Phase 2: Pilot Multipurpose Shipyard(s). Launch demonstration shipyards and monitor operational results.

- Phase 3: Evaluation and Scale-Up. Expand based on pilot feedback and regional need.

- Phase 4: Full Integration and Continuous Improvement. Build a network, institutionalise best practices, and update standards as knowledge advances.

6. Conclusion and Further Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Baso, M. Musrina, and A. Anggriani, “Strategy for Improving the Competitiveness of Shipyards in the Eastern Part of Indonesia,” Kapal: Jurnal Ilmu Pengetahuan dan Teknologi Kelautan, vol. 17, pp. 74–85, Jun. 2020. https://doi.org/10.14710/kapal.v17i2.29448. [CrossRef]

- T. Rizwan et al., “Literature review on shipyard productivity in Indonesia,” Depik, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Agung and A. Farinah, “The Urgency Of Green Ship Recycling Methods And Its Regulations In Indonesia From The International Law Perspective,” ULREV, vol. 6, no. 2, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Fitriadi and A. F. M. Ayob, “Optimizing Traditional Shipyard Industry: Enhancing Manufacturing Cycle Efficiency for Enhanced Production Process Performance,” IJIETOM, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 15–24, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Ocampo and N. N. Pereira, “Can ship recycling be a sustainable activity practiced in Brazil?,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 224, pp. 981–993, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. O. IMO, “The Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships.” Accessed: May 14, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.imo.org/en/about/Conventions/pages/the-hong-kong-international-convention-for-the-safe-and-environmentally-sound-recycling-of-ships.aspx.

- E. M. Rogers, A. Singhal, and M. M. Quinlan, “Diffusion of innovations,” in An integrated approach to communication theory and research, Routledge, 2014, pp. 432–448.

- R. K. Mitchell, B. R. Agle, and D. J. Wood, “Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts,” The Academy of Management Review, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 853–886, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Statista.com, “Topic: Maritime industry in Indonesia,” Statista. Accessed: Nov. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/topics/12042/maritime-industry-in-indonesia/.

- trade.gov, “Indonesia - Market Overview.” Accessed: Nov. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/indonesia-market-overview.

- business-indonesia.org, “Maritime | Business-Indonesia.” Accessed: Nov. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://business-indonesia.org/maritime.

- Komara, K. T. P. Iroth, S. Sungkono, J. S. Saragih, S. U. Sahubawa, and M. Dwiwanti, “The Potential of Indonesia’s Ship Engine Market to Attract Foreign Investors for Domestic Manufacturing,” Equity, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 66–82, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Vakili, A. Schönborn, and A. I. Ölçer, “The road to zero emission shipbuilding Industry: A systematic and transdisciplinary approach to modern multi-energy shipyards,” Energy Conversion and Management: X, vol. 18, p. 100365, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Mohamad Idris, W. N. Wan Zakaria, N. H. N. Mahmood, and P. Mohd Samin, “Job Performance of Shipyard Workforce in the Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Industry: Do Competencies Matter in Malaysian Shipyards?,” IJARBSS, vol. 13, no. 3, p. Pages 1006-1016, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Ishak and M. Meica, “Implementation of Cabotage Principle in Indonesia Territory and Its Implication for Shipping: A Study from Law Perspective,” in Proceeding of Marine Safety and Maritime Installation (MSMI 2018), Clausius Scientific Press, 2018. [CrossRef]

- IMO, Ed., Hong Kong Convention: Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships, 2009 ; with the guidelines for its implementation, 2013 edition. in IMO publication. London: International Maritime Organization, 2009.

- IMO, “Guidelines for the development of the Inventory of the Hazardous Materials.” 2023. Accessed: May 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Documents/MEPC.379(80).pdf.

- M. A. Oktaviany, “Challenges for the ratification of the Hong Kong Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships, 2009 in Indonesia,” WMU, 2019. Accessed: Jun. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://commons.wmu.se/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2168&context=all_dissertations.

- IMO, “International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL).” Accessed: Jun. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.imo.org/en/about/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Prevention-of-Pollution-from-Ships-(MARPOL).aspx.

- IMO, “Indonesia ratifies several IMO instruments,” Indonesia ratifies several IMO instruments. Accessed: Jun. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/33-indonesiaratifies.aspx.

- Sudirman, M. Maulana, and A. Yola, “Legal Cooperation in the ASEAN Maritime Environment in the Free Trade Era: Its Implication for Indonesia,” HasanuddinLawReview, vol. 8, no. 9, 2022.

- U. N. E. UNEP, “Basel Convention on Hazardous Wastes.” 1989. [Online]. Available: http://www.basel.int.

- Basel, “Basel Convention Regional Centre for South-East Asia in Indonesia (BCRC Indonesia).” Accessed: Jun. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.basel.int/?tabid=4845.

- Ministry of Transportation of Indonesia, PERATURAN MENTERI PERHUBUNGAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR: PM 29 TAHUN 2014 TENTANG PENCEGAHAN PENCEMARAN LINGKUNGAN MARITIM, Rules and Regulation, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://hubla.dephub.go.id/storage/portal/documents/post/6659/pm_29_tahun_2014.pdf.

- President of Republic Indonesia, Undang-Undang No. 17 Tahun 2008 tentang Pelayaran (Law 17/2008 on Shipping). 2008. Accessed: Jun. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Download/28451/UU%20Nomor%2017%20Tahun%202008.pdf.

- S. Fariya, K. Suastika, and M. S. Arif, “Design of Sustainable Ship Recycling Yard in Madura,Indonesia,” presented at the The Conference of Theory and Application on Marine Technology, Surabaya, Indonesia, Dec. 2016. Accessed: Mar. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://repository.its.ac.id/69417/.

- Zainol, C. L. Siow, A. F. Ahmad, M. R. Zoolfakar, and N. Ismail, “Hybrid shipyard concept for improving green ship recycling competitiveness,” IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 1143, no. 1, p. 012021, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Chabane, “Design of a Small Shipyard Facility Layout Optimised for Production and Repair,” 2004.

- Zainol, S. C. Loon, Ahmad Faizal Ahmad Fuad, Nuraihan Ismail, and Khairunnisa Rosli, “Integrating Ship Recycling Facility into Existing Shipyard: A Study of Malaysian Shipyard,” ARASET, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 217–227, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sunaryo and B. A. Tjitrosoemarto, “Integrated ship recycling industrial estate design concept for Indonesia,” IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 972, no. 1, p. 012042, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Azhar, N. Harahab, F. Putra, and A. Kurniawan, “Environmental sustainability criteria in the multi-oriented shipbuilding industry in Indonesia,” Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs, pp. 1–21, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Barua et al., “Environmental hazards associated with open-beach breaking of end-of-life ships: a review,” Environ Sci Pollut Res, vol. 25, no. 31, pp. 30880–30893, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- I. Alcaide, E. Rodríguez-Díaz, and F. Piniella, “European policies on ship recycling: A stakeholder survey,” Marine Policy, vol. 81, pp. 262–272, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Budiyanto, H. Kusnoputranto, R. S. Widjaja, and F. Lestari, “Environmental Insurance Model in the Shipyard Industry,” Asian Journal of Applied Sciences, vol. 04, no. 03, 2016.

- M. Tantan and H. Camgöz-Akdağ, “SUSTAINABILITY CONCEPT IN TURKISH SHIPYARDS,” presented at the SDP 2020, Nov. 2020, pp. 269–281. [CrossRef]

- H. Schøyen, U. Burki, and S. Kurian, “Ship-owners’ stance to environmental and safety conditions in ship recycling. A case study among Norwegian shipping managers,” Case Studies on Transport Policy, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 499–508, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Halim Mad Lazim and Jamaluddin Abdullah, “Malaysia Shipbuilding Industry: A Review on Sustainability and Technology Success Factors,” ARASET, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 154–164, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Zaabi and R. Pech, “Strategic corporate governance stakeholder complexities in strategic decision implementation (sdi): The shipbuilding industry in Abu Dhabi,” jda, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 235–246, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Sunaryo and F. Y. Santoso, “CONVERSION DESIGN OF AN IDLE FERRY PORT INTO GREEN SHIP RECYCLING YARD,” SSRN Journal, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Egorova, M. Torchiano, M. Morisio, C. Wohlin, A. Aurum, and R. B. Svensson, “Stakeholders’ Perception of Success: An Empirical Investigation,” in 2009 35th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications, Aug. 2009, pp. 210–216. [CrossRef]

- M. Eskafi et al., “Stakeholder salience and prioritization for port master planning, a case study of the multi-purpose Port of Isafjordur in Iceland,” European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, vol. 19, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Bunn, F. Azmi, and M. Puentes, “Stakeholder perceptions and implications for technology marketing in multi-sector innovations: the case of intelligent transport systems,” International Journal of Technology Marketing, vol. 4, no. 2–3, pp. 129–148, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Sooprayen, G. Van De Kaa, and J. F. J. Pruyn, “Factors for innovation adoption by ports: a systematic literature review,” J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 953–962, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Castro, P. M. Klajnberg, A. B. Barcaui, M. Castro, P. M. Klajnberg, and A. B. Barcaui, “The Impact of Stakeholder Salience in the Relationship between Stakeholder-Oriented Governance Practices and Project Success,” in Corporate Governance - Evolving Practices and Emerging Challenges, IntechOpen, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Braun and V. Clarke, “Using thematic analysis in psychology,” Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77–101, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Hariyanto, N. I. Gutami, Z. Qonita, N. Shabrina, D. A. Wibowo, and A. Muhtadi, “The Development of Ship Recycling Facility Cluster in Indonesia,” IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 1166, no. 1, p. 012007, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Pratama and A. Fadillah, “Study on development of shipyard type for supporting pioneer ship in Indonesia,” IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 339, no. 1, p. 012045, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- PaxOcean, “Decommissioning & Green Recycling,” DECOMMISSIONING & GREEN RECYCLING. Accessed: May 14, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://paxocean.com/services/decommissioning/.

| Stakeholder |

Relative Advantage |

Compatibility | Complexity | Trialability | Observability |

Total DOI Index |

| Shipyard Executives | 4.80 | 4.50 | 2.90 | 3.60 | 3.80 | 19.80 |

| Government | 4.60 | 4.40 | 3.00 | 3.40 | 3.60 | 19.00 |

| Shipowners | 4.50 | 4.20 | 3.10 | 3.30 | 3.50 | 18.40 |

| Employees | 3.90 | 3.60 | 3.70 | 2.90 | 3.10 | 15.80 |

| Academics | 4.10 | 3.90 | 3.90 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 16.10 |

| Suppliers | 3.80 | 3.70 | 3.60 | 2.70 | 2.80 | 15.40 |

| Community | 3.70 | 3.40 | 4.10 | 2.50 | 2.60 | 14.10 |

| Stakeholder |

Market Demand |

Workforce Dev. |

Regulatory | Environmental |

Operational Efficiency |

| Academics | 3.6 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 4.2 |

| Community | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 3.4 |

| Employees | 3.5 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 4 |

| Government | 4 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.8 |

| Shipowners | 4.3 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 4.2 |

| Shipyard Managers | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 4.3 |

| Suppliers | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4 | 3.5 | 3.9 |

| Stakeholder Group |

Salience Attributes |

Adoption Category |

Top Concern Area |

| Government | Definitive | Early Adopter | Regulatory compliance |

| Shipyard Managers | Dominant | Innovator | Operational efficiency |

| Shipowners | Definitive | Early Adopter | Market demand |

| Employees | Dependent | Late Majority | Workforce development |

| Suppliers | Dependent | Laggard | Process disruption |

| Academics | Discretionary | Late Majority | Sustainability |

| Community | Dependent | Late Majority | Environmental impact |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).