Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. High-Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)

2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

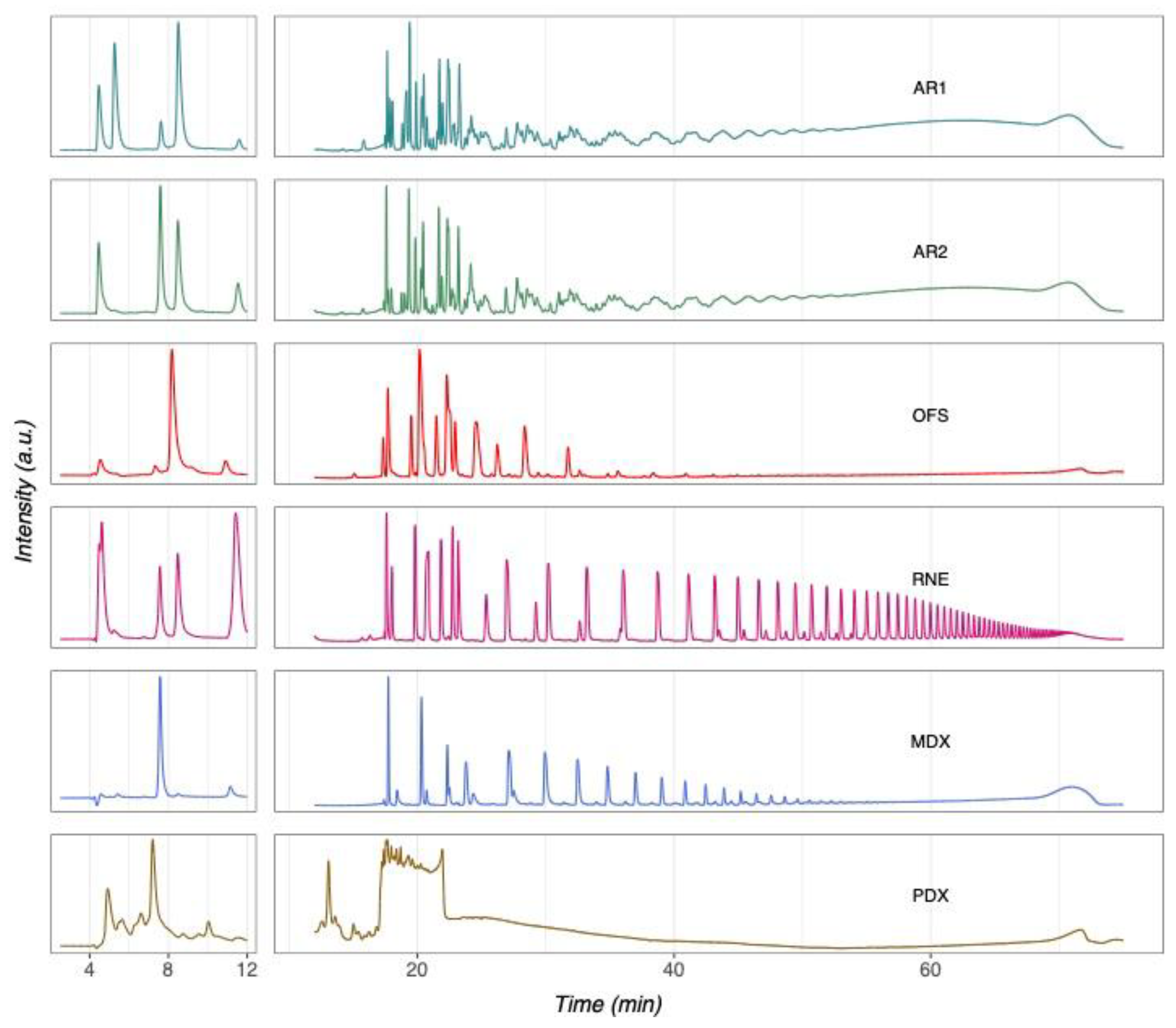

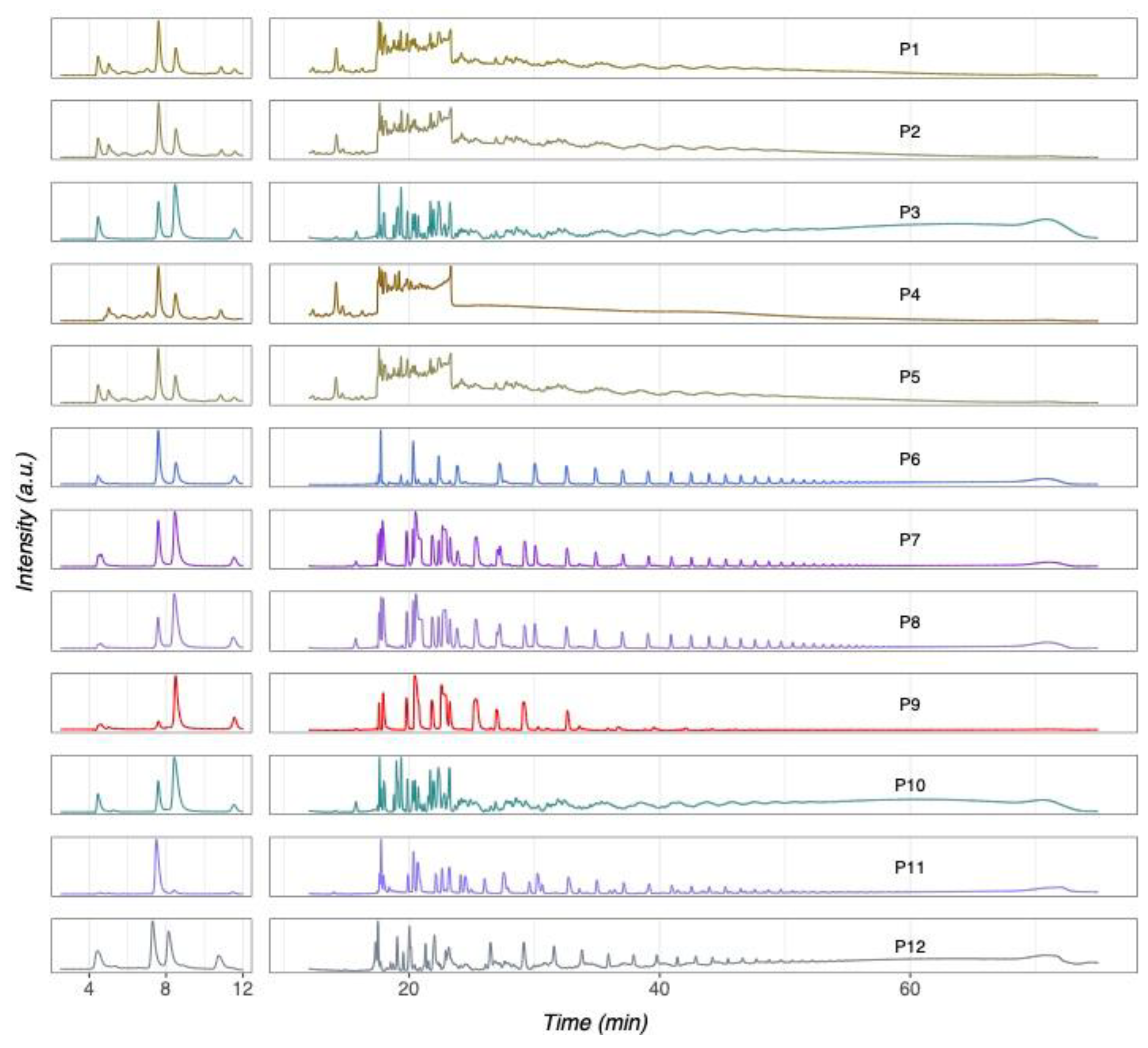

2.3. High-Performance Anion Exchange Chromatography Coupled to a Pulsed Amperometric Detector (HPAEC-PAD)

3. Results and Discussion

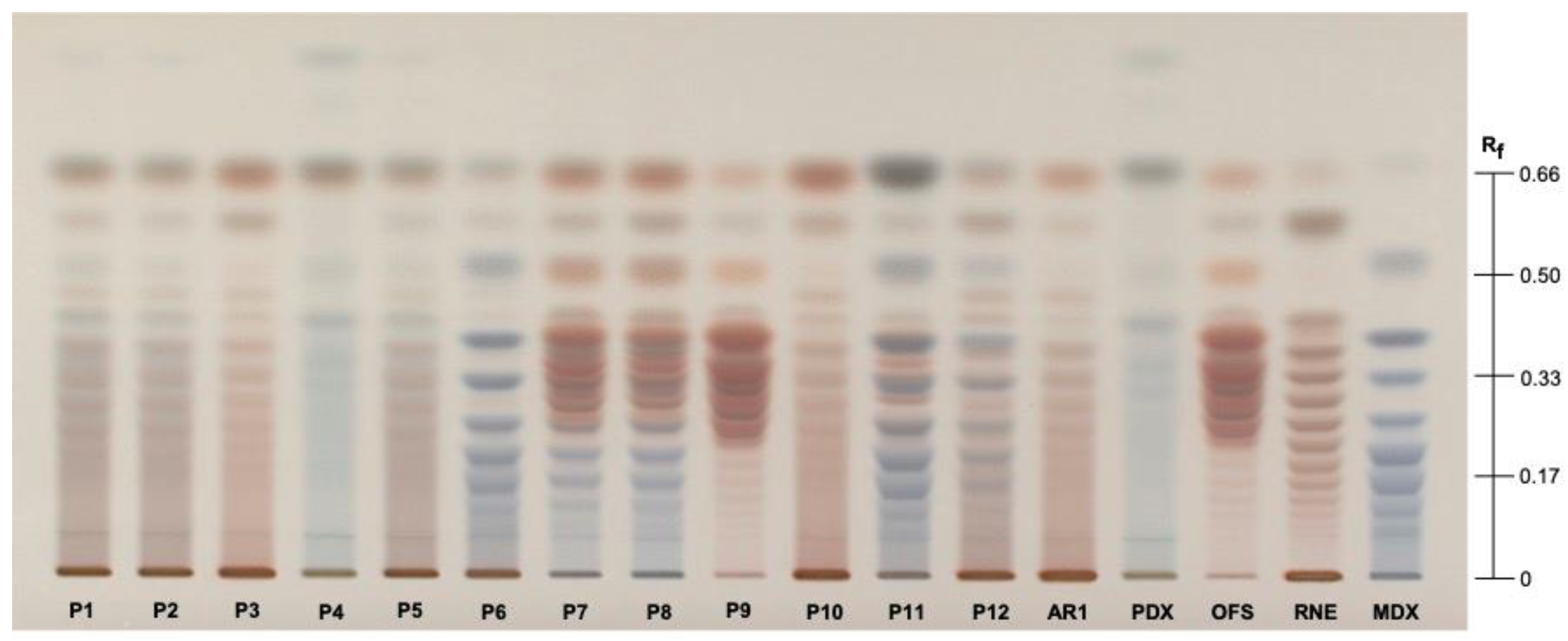

3.1. Authentication of Commercial Agavins by HPTLC

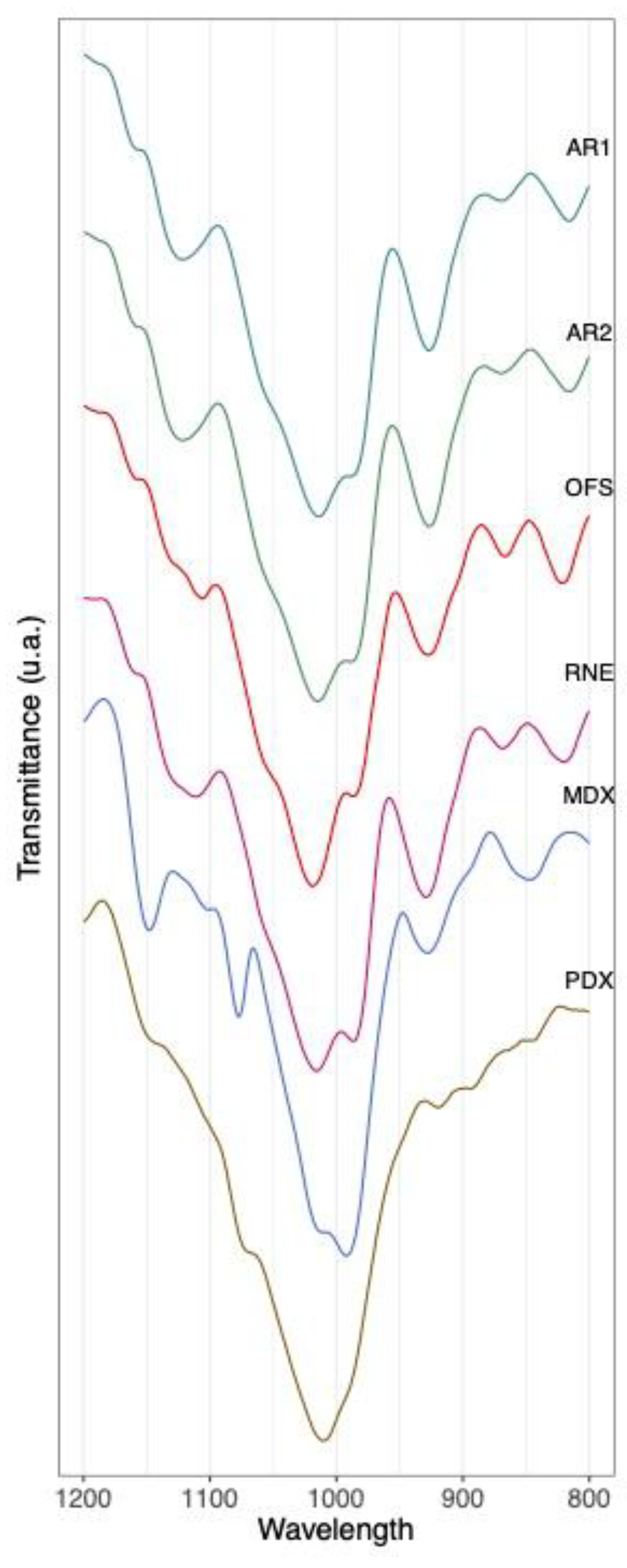

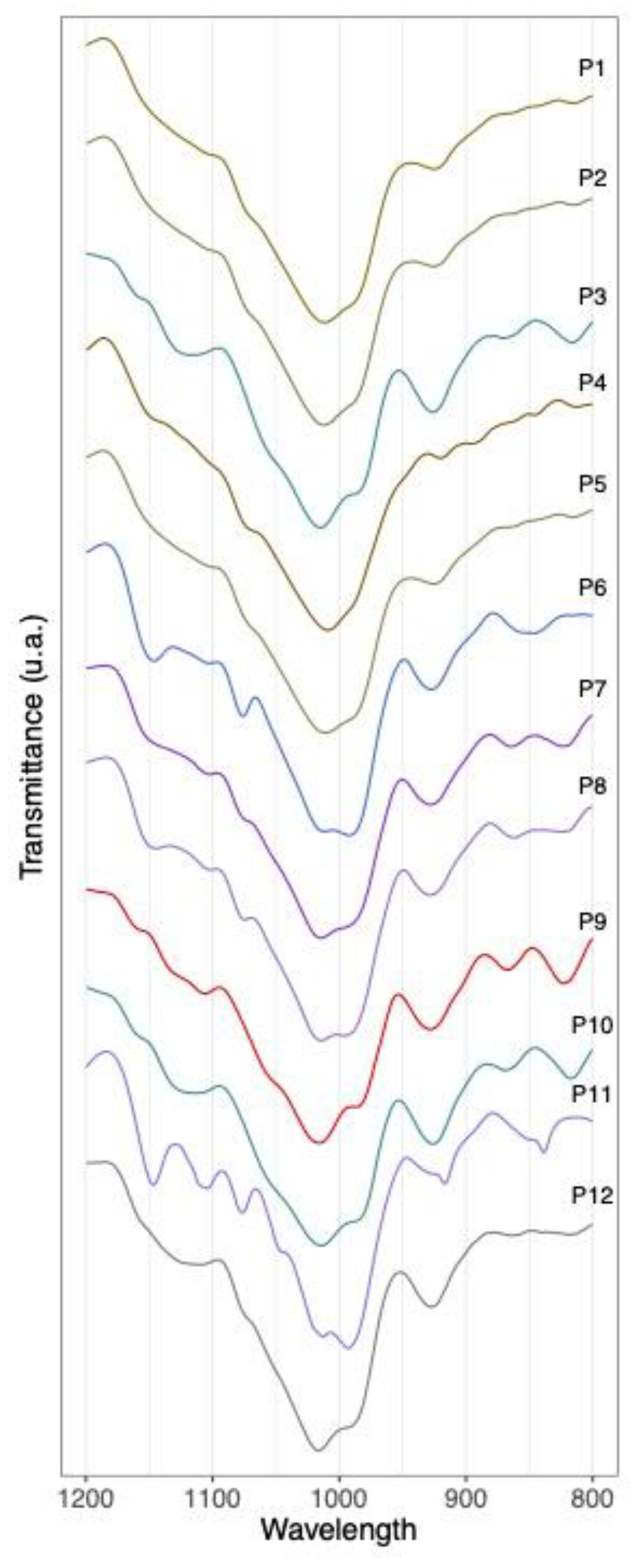

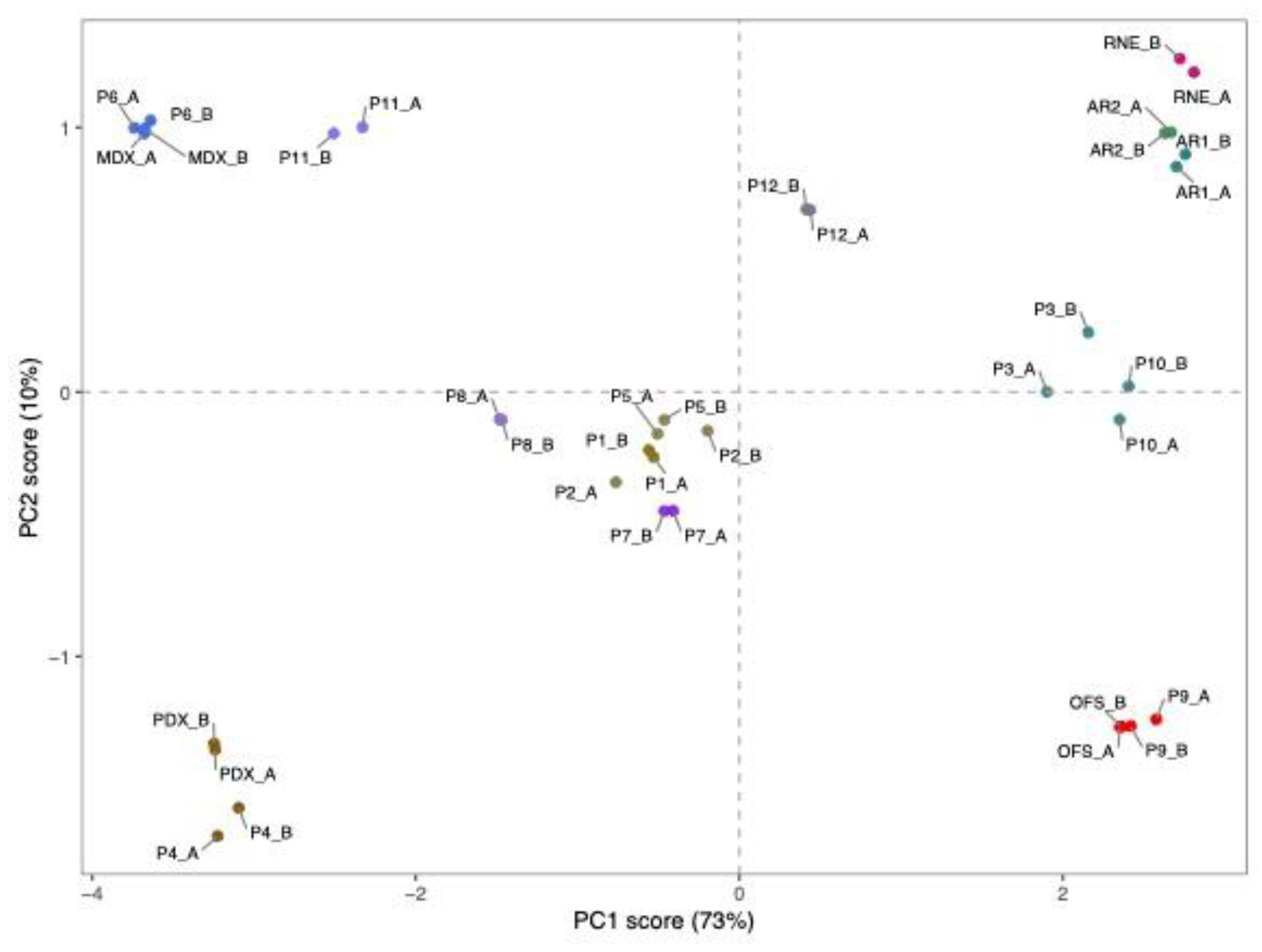

3.2. Authentication of Commercial Agavins Employing FTIR Coupled to PCA Analysis

3.2. Authentication of Commercial Agavins Employing FTIR Coupled to PCA Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Webb, G.P. An overview of dietary supplements and functional foods. In Dietary Supplements and Functional Foods; Webb, G.P., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huazano-García, A.; Silva-Adame, M.B.; López, M.G. Preclinical and clinical fructan studies. In The Book of Fructans; Van den Ende, W., Toksoy Öner, E., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Andrews, H.; Urías-Silvas, J.; Morales-Hernández, N. The role of agave fructans in health and food applications: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 585−598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancilla-Margalli, N.A.; López, M.G. Water-soluble carbohydrates and fructan structure patterns from Agave and Dasylirion species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7832−7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaria de economía. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/en/profile/product/inulin (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Momtaz, M.; Bubli, S.Y.; Khan, M.S. Mechanisms and health aspects of food adulteration: a comprehensive review. Foods 2023, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, D.; Dayananda, B.; Chapman, J. Food adulteration. In Chemometrics Data Treatment and Applications; Narciso Fernandes, F.A., Rodrigues, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2024; pp. 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinothkanna, A.; Iqbal Dar, O.; Liu, Z.; Jia, A.Q. Advanced detection tools in food fraud: a systematic review for holistic and rational detection method based on research and patents. Food Chem. 2024, 446, 138893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haji, A.; Desalegn, K.; Hassen, H. Selected food items adulteration, their impacts on public health, and detection methods: a review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 7534−7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, A. Global market entry regulations for nutraceuticals, functional foods, dietary/food/health supplements. In Developing New Functional Food and Nutraceutical Products; Bagchi, D., Nair, S., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre-Luc, L.; Hua, M.Z.; Hu, Y.; Elliott, C.; Lu, X. Editorial: food authentication. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 150, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deconinck, E.; Vanhamme, M.; Bothy, J.L.; Courselle, P. A strategy based on fingerprinting and chemometrics for the detection on regulated plants in plant food supplements from the belgian market: two case studies. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 166, 189−196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Saona, L.E.; Giusti, M.M.; Shotts, M. Advances in infrared spectroscopy for food authenticity testing. In Advances in Food Authenticity Testing. Downey, G., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Duxford, UK, 2016; pp. 71–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomé-Abarca, L.F.; Márquez-López, R.E.; Santiago-García, P.A.; López, M.G. HPTLC-based fingerprinting: an alternative approach for fructooligosaccharides metabolism profiling. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado-Mojica, E.; López, M.G. Fructan metabolism in A. tequilana Weber blue variety along its developmental cycle in the field. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11704−11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.G. Chemical and structural-functional features of fructans. In The Book of Fructans, 1st ed.; Van den Ende, W., Toksoy Öner, E., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Applications of infrared spectroscopy in polysaccharide structural analysis: progress, challenge and perspective. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannasutta, R.; Laopeng, S.; Yuensuk, S.; McLoskey, S.; Riddech, N.; Mongkolthanaruk, W. Biopolymer-levan characterization in Bacillus species isolated from traditionally fermented soybeans (Thua Nao). ACS Omega 2025, 10, 1677−1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q.; An, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Tuerhong, M.; Ohizumi, Y.; Jin, J.; Xu, J.; Guo, Y. A fructan from Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge showing neuroprotective and immunoregulatory effects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Yin, B.; Qiu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, Z.; Li, M. Structural characterization and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides extracted from Polygonati rhizoma pomace. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Shao, T.; Gao, L.; Yuan, P.; Ren, Z.; Tian, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Xu, X.; Zhou, X.; Han, J.; Wang, G. Structural elucidation and hypoglycemic effect of an inulin-type fructan extracted from Stevia rebaudiana roots. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 2518−2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, P.; Mao, G.; Zhao, T.; Feng, W.; Yang, L.; Wu, X. Structural elucidation and antioxidant activity a novel Se-polysaccharide from Se-enriched Grifola frondosa. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 161, 42−52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Le, G. Rapid microwave-assisted synthesis of polydextrose and identification of structure and function. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 113, 225−230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huazano-García, A.; López, M.G. Enzymatic hydrolysis of agavins to generate branched fructooligosaccharides (a-FOS). Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 184, 25−34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.R. Jr.; Hudson, P.; Adamson, J.T. Dextrin characterization by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography−pulsed amperometric detection and size-exclusion chromatography−multi-angle light scattering−refractive index detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 997, 79−85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radosta, S.; Boczek, P.; Grossklaus, R. Composition of polydextrose® before and after intestinal degradation in rats. Starch 1992, 44, 150−153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowell, J.D. Prebiotic potential of polydextrose. In Prebiotics and Probiotics Science and Technology; Charalampopoulos, D., Rastall, R.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, USA, 2009; pp. 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo, M.M.; Walker, J.C.; Novello, D.; Caselato, V.M.; Sgarbieri, V.C.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Andreollo, N.A.; Hiane, P.A.; Dos Santos, E.F. Polydextrose: physiological function, and effects on health. Nutrients 2016, 8, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.Q.; Wang, L.Y.; Yang, X.Y.; Xu, Y.J.; Fan, G.; Fan, Y.G.; Ren, J.N.; An, Q.; Li, X. Inulin: properties and health benefits. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 2948−2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huazano-García, A.; Shin, H.; López, M.G. Modulation of gut microbiota of overweight mice by agavins and their association with body weight loss. Nutrients 2017, 9, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huazano-García, A.; López, M.G. Agavins reverse the metabolic disorders in overweight mice through the increment of short chain fatty acids and hormones. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 3720−3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Adame, M.B.; Martínez-Alvarado, A.; Martínez-Silva, V.A.; Samaniego-Méndez, V.; López, M.G. Agavins impact on gastrointestinal tolerability-related symptoms during a five-week dose-escalation intervention in lean and obese mexican adults: exploratory randomized clinical trial. Foods 2022, 11, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).