Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Definition of Digital Sovereignty and Examples of Publications Revealing Its Current Aspects

Technological Sovereignty in Publications Indexed in Abstract Databases

Materials and Methods

Materials

Methods

Results and Discussion

Keyword Extraction Using YAKE!

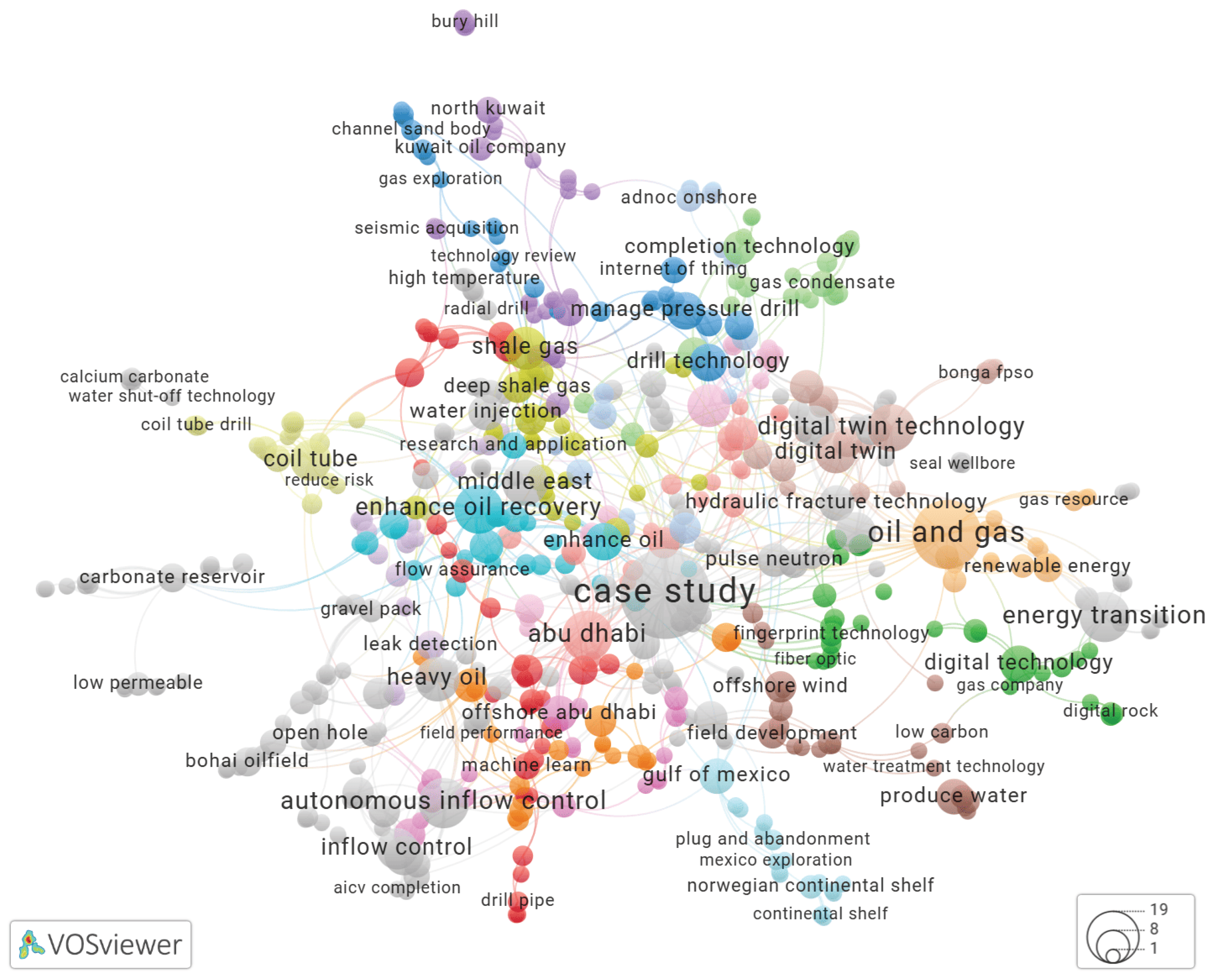

Using VOSviewer to Build a Keyword Co-Occurrence Network

| keyword | N | keyword | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| oil and gas | 223 | natural gas | 38 |

| result show | 94 | carbonate reservoir | 37 |

| coil tube | 61 | seismic datum | 37 |

| real time | 59 | completion design | 35 |

| hydraulic fracture | 58 | energy transition | 35 |

| drill operation | 51 | low permeable | 35 |

| open hole | 49 | mature field | 35 |

| high pressure | 45 | production rate | 35 |

| high temperature | 45 | water cut | 35 |

| operational efficiency | 44 | drill technology | 34 |

| flow rate | 43 | water injection | 34 |

| middle east | 43 | field test | 33 |

| enhance oil recovery | 42 | reduce cost | 33 |

| horizontal section | 40 | innovative technology | 32 |

| machine learn | 40 | carbon capture | 31 |

Discussion

Reasons Why Countries Must Address Technological Sovereignty Issues

- 5.1 Technology, equipment and services for drilling and geological exploration

- 5.2 Technology and machinery for the production of liquefied natural gas equipment

- 5.3 Production of oil and gas transportation equipment

- 9.1.1 Marine tankers for transportation of crude oil, petroleum products, chemical products, liquefied gas

- 9.1.2 River vessels for transportation of liquefied gas

- 12.5 Manufacturing of electronics for oil and gas engineering

- 13.5 Manufacturing of equipment for hydrogen power engineering

- 13.4 Manufacturing of electrical energy storage and accumulation systems

- 13.7 Construction of power plants for generation on renewable energy sources, including solar, wind and geothermal energy sources

- 13.8 Construction of power plants for generation on hydrogen fuel

Conclusions

Funding

| 1 |

https://github.com/anyascii/anyascii — The utility converts Unicode characters to their optimal ASCII representation |

| 2 |

https://winmerge.org/ — an Open-Source differencing and merging tool for Windows |

| 3 | |

| 4 |

References

- Dovbiy, I.; Egorova, A.; Danilov, I. , “Technological sovereignty in the Era of energy transition and implementation of ESG principles in regional industrial agenda,” E3S Web of Conf., vol. 389, p. 01077, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Edler, J.; Blind, K.; Kroll, H.; Schubert, T. , “Technology sovereignty as an emerging frame for innovation policy. Defining rationales, ends and means,” Research Policy, vol. 52, no. 6, p. 104765, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- March, C.; Schieferdecker, I. , “Technological Sovereignty as Ability, Not Autarky,” International Studies Review, vol. 25, no. 2, p. viad012, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Physics, F.S.U.E.R.F.N.C.-A.-R.R.I.O.E.; Faykov, D.Y.; Baydarov, D.Y.; Corporation, D.O.S.F.N.B.R.S.A.E. , “Towards Technological Sovereignty: Theoretical Approaches, Practice, Suggestions,” Econ. Rev. Rus., no. 1 (75), pp. 67–82, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Afonin, A.N.; Kiseleva, N.N. , “Technological Sovereignty as a Basis of National Security,” ESLFAR, no. 17, pp. 93–97, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.; Boeing, P. , “Global Influence of Inventions and Technology Sovereignty,” SSRN Journal, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Edler, J.; Blind, K.; Kroll, H.; Schubert, T. , “Technology sovereignty as an emerging frame for innovation policy - Defining rationales, ends and means”. [CrossRef]

- Shtern, M.; Herman, L.; Fischhendler, I.; Rosen, G. , “Infrastructure sovereignty: battling over energy dominance in Jerusalem,” Territory, Politics, Governance, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 183–203, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Belli, L.; Gaspar, W.B.; Jaswant, S.S. , “Data sovereignty and data transfers as fundamental elements of digital transformation: Lessons from the BRICS countries,” Computer Law & Security Review, vol. 54, p. 106017, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Holfelder, W.; Mayer, A.; Baumgart, T. , “Sovereign Cloud Technologies for Scalable Data Spaces,” in Designing Data Spaces, B. Otto, M. Ten Hompel, and S. Wrobel, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 419–436. [CrossRef]

- Kachelin, A.S. , “International cooperation as a factor of scientific and technological development in the oil and gas industry of the Russian Federation,” Vestnik of Samara University. Economics and Management, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 34–52, 23. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Durodolu, O.O.; Ibenne, S.K. , “Knowledge sovereignty: clearing the mental cobweb through library engagement,” LHTN, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 13–14, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.S.S. , “Veritas et Vox: The Dichotomy of Freedom of Expression and Media Sovereignty in India,” Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev., vol. 5, no. 9, pp. 835–838, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tambini, D. , “The ‘Netflix effect’ revisited: OTT video, media globalization and digital sovereignty in 4 countries,” Telecommunications Policy, vol. 49, no. 5, p. 102935, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chigarev, B. , “Technological Sovereignty as a Current Energy Security Challenge. Preliminary Analysis,” , 2025. 19 May. [CrossRef]

- Uusitalo, M.A.; et al. , “Hexa-X The European 6G flagship project,” in 2021 Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit), Porto, Portugal: IEEE, Jun. 2021, pp. 580–585. [CrossRef]

- Ezratty, O. , “Mitigating the quantum hype,” 2022, arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Menconi, M.E. ; S. dell’Anna; Scarlato, A., Ed.; Grohmann, D., “Energy sovereignty in Italian inner areas: Off-grid renewable solutions for isolated systems and rural buildings,” Renewable Energy, vol. 93, pp. 14–26, Aug. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdaneev, O. , “Technological sovereignty of the Russian Federation fuel and energy complex,” PMI, vol. Online first, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fuel, T.D.C.F.; Federation, E.C.U.T.M.O.E.O.T.R. ; Moscow; Russia, T.D.A.O.T.M.O.F.A.O.; Moscow; Zhdaneev, O.V.; Frolov, K.N.; Fuel, T.D.C.F.; Federation, E.C.U.T.M.O.E.O.T.R.; Moscow, “Scientific and technological priorities of the fuel and energy complex of the Russian Federation until 2050,” OIJ, no. 10, pp. 6–13, 2023. [CrossRef]

- RF, S.U.O.M. ; Moscow; Afanasyev, V.Y.; Suslov, D.A.; RF, S.U.O.M.; Moscow; Chuev, S.V.; RF, S.U.O.M.; Moscow, “Soviet experience in the development of economic and industrial potential under sanctions,” OIJ, no. 12, pp. 156–160, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.; Mangaravite, V.; Pasquali, A.; Jorge, A.; Nunes, C.; Jatowt, A. , “YAKE! Keyword extraction from single documents using multiple local features,” Information Sciences, vol. 509, pp. 257–289, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. , “Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping,” Scientometrics, vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 523–538, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; et al. , “An Intelligent Intermittent Pumping Production Technology Based on Fusion of Photovoltaic Unit and Storage Battery,” in International Petroleum Technology Conference, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia: IPTC, Feb. 2024, p. D031S112R009. [CrossRef]

- Taher, A.; Fouda, M. , “Unlocking Reservoir Potential with Logging-While-Drilling Technologies in Mature Fields,” in SPE Conference at Oman Petroleum & Energy Show, Muscat, Oman: SPE, Apr. 2024, p. D021S014R003. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabea, S.; et al. , “Achieving Higher Productivity from Mishrif Reservoir with Multistage Completion Technology: Challenges, Solutions and Performance,” in Middle East Oil, Gas and Geosciences Show, Manama, Bahrain: SPE, Mar. 2023, p. D021S079R006. [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Chen, H.; Ni, M. , “Quantitative Study of CO2 Huff-N-Puff Enhanced Oil Recovery in Shale Formation Using Online NMR and Core Simulation Technology,” in SPE Conference at Oman Petroleum & Energy Show, Muscat, Oman: SPE, 25, p. D011S008R007. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zou, L. , “Fracturing Technology of Real Time Control Guarantees Highly Efficient Exploitation of Shale in Weiyuan Gas-Field, SW China,” in SPE Russian Petroleum Technology Conference, Virtual: SPE, Oct. 2020, p. D033S010R006. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; et al. , “Numerical Model Evaluation for Advanced Nano-Chemical Water Shut-Off Technology Overcoming Crossflow in Carbonate Reservoir,” in SPE Water Lifecycle Management Conference and Exhibition, Abu Dhabi, UAE: SPE, Mar. 2024, p. D021S007R002. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; et al. , “Efficient Through-Casing Surveillance of Steam Chamber and Reservoir Oil Using a New Pulsed Neutron Technology and an Advanced Interpretation Algorithm,” in Middle East Oil, Gas and Geosciences Show, Manama, Bahrain: SPE, Mar. 2023, p. D021S082R004. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.; Batarseh, S.; Alharith, A.; Alerigi, D.P.S.R.; Alrashed, A.A. , “Aligning Upstream Operations with Sustainable Technology: High Power Lasers,” in GOTECH, Dubai, UAE: SPE, 24, p. D031S048R001. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Clautiaux, F.; Ljubić, I. , “Last fifty years of integer linear programming: A focus on recent practical advances,” European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 324, no. 3, pp. 707–731, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tatiankin, V.M. , “Numerical Method of Solving One Problem of Integral Non-Linear Programming,” Научнoе Обoзрение (Nauchnoe Obozrenie), no. 11–1, pp. 29–32, 2014, Accessed: Jun. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp? 2302. [Google Scholar]

- “The cost of compute power: A $7 trillion race | McKinsey.” Accessed: Jun. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mckinsey.

- Hauser, H. , “Technology, Sovereignty and Realpolitik,” in Consensus or Conflict?, H. Wang and A. Michie, Eds., Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2021, pp. 233–242. [CrossRef]

- “Secure Control Systems: A Quantitative Risk Management Approach,” IEEE Control Syst., vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 24–45, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, S.M. , “Modeling and simulating critical infrastructures and their interdependencies,” in 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2004. Proceedings of the, Jan. 2004, p. 8 pp.-. [CrossRef]

- Irion, K. , “Government Cloud Computing and National Data Sovereignty,” Policy & Internet, vol. 4, no. 3–4, pp. 40–71, Dec. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.D. , “‘Data localization’: The internet in the balance,” Telecommunications Policy, vol. 44, no. 8, p. 102003, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chernikov, A.V. , “Implementation of the policy of technological sovereignty in China,” International Trade and Trade Policy, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 5–15, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ogunsuji, Y.M.; Amosu, O.R.; Choubey, D.; Abikoye, B.E.; Kumar, P.; Umeorah, S.C. , “Sourcing renewable energy components: building resilient supply chains, reducing dependence on foreign suppliers, and enhancing energy security,” World J. Adv. Res. Rev., vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 251–262, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bednarski, L.; Roscoe, S.; Blome, C.; Schleper, M.C. , “Geopolitical disruptions in global supply chains: a state-of-the-art literature review,” Production Planning & Control, pp. 1–27, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Graham, I.; Jakobs, K.; Lyytinen, K. , “China and Global ICT standardisation and innovation,” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 715–724, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Mattli, W.; Büthe, T. , “Setting International Standards: Technological Rationality or Primacy of Power?,” World Pol., vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 1–42, Oct. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Economics, C.; Sciences, M.I.R.A.O.; Dementiev, V.E. , “Technological Sovereignty and Economic Interests,” JIS, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 006–018, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Efremenko, D.V. , “Formation of Digital Society and Geopolitical Competition,” Kontury glob. transform.: polit. èkon. pravo, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 25–43, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.; et al. , “The Second Cold War: US-China Competition for Centrality in Infrastructure, Digital, Production, and Finance Networks,” Geopolitics, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1083–1120, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- AlDaajeh, S.; Saleous, H.; Alrabaee, S.; Barka, E.; Breitinger, F.; Choo, K.-K.R. , “The role of national cybersecurity strategies on the improvement of cybersecurity education,” Computers & Security, vol. 119, p. 102754, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.L.; Rao, A. , “Non-Technical skills needed by cyber security graduates,” in 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Porto, Portugal: IEEE, Apr. 2020, pp. 354–358. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.; et al. , “Identifying and Mitigating the Security Risks of Generative AI,” FNT in Privacy and Security, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–52, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Flechais, I. , “Digital deception: generative artificial intelligence in social engineering and phishing,” Artif Intell Rev, vol. 57, no. 12, p. 324, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Baur, A. , “European ambitions captured by American clouds: digital sovereignty through Gaia-X?,” Information, Communication & Society, pp. 1–18, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).