Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

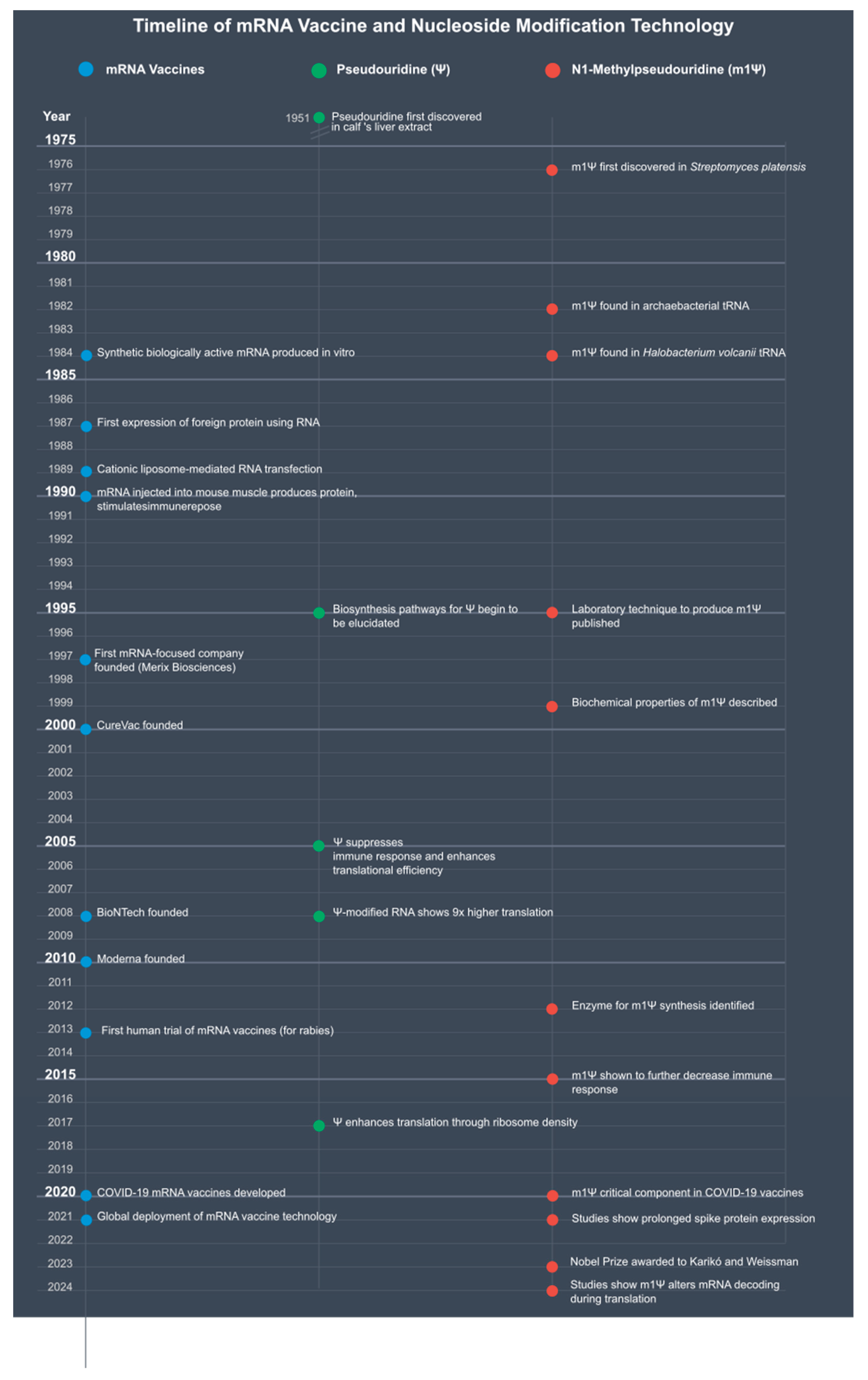

Introduction

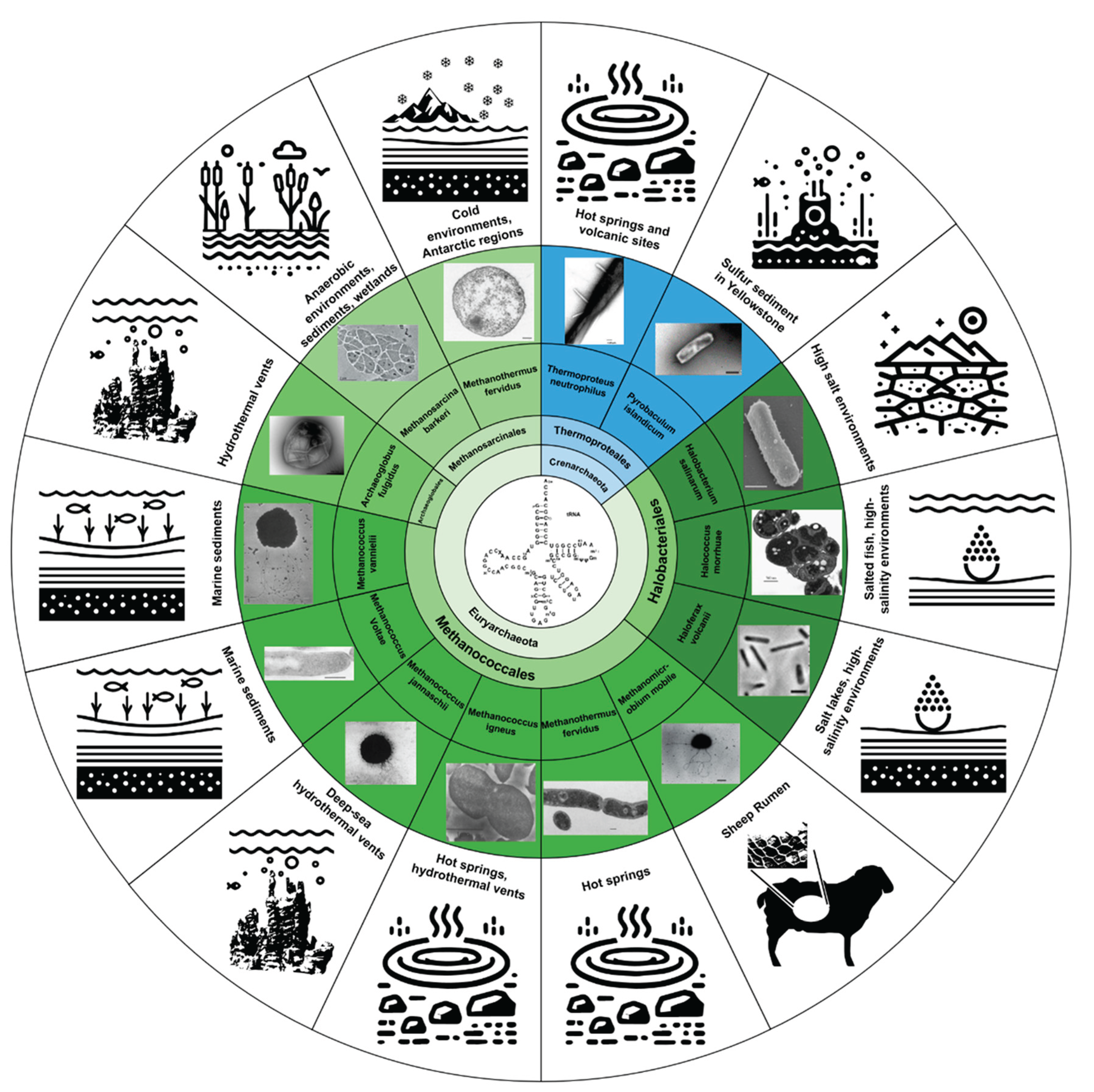

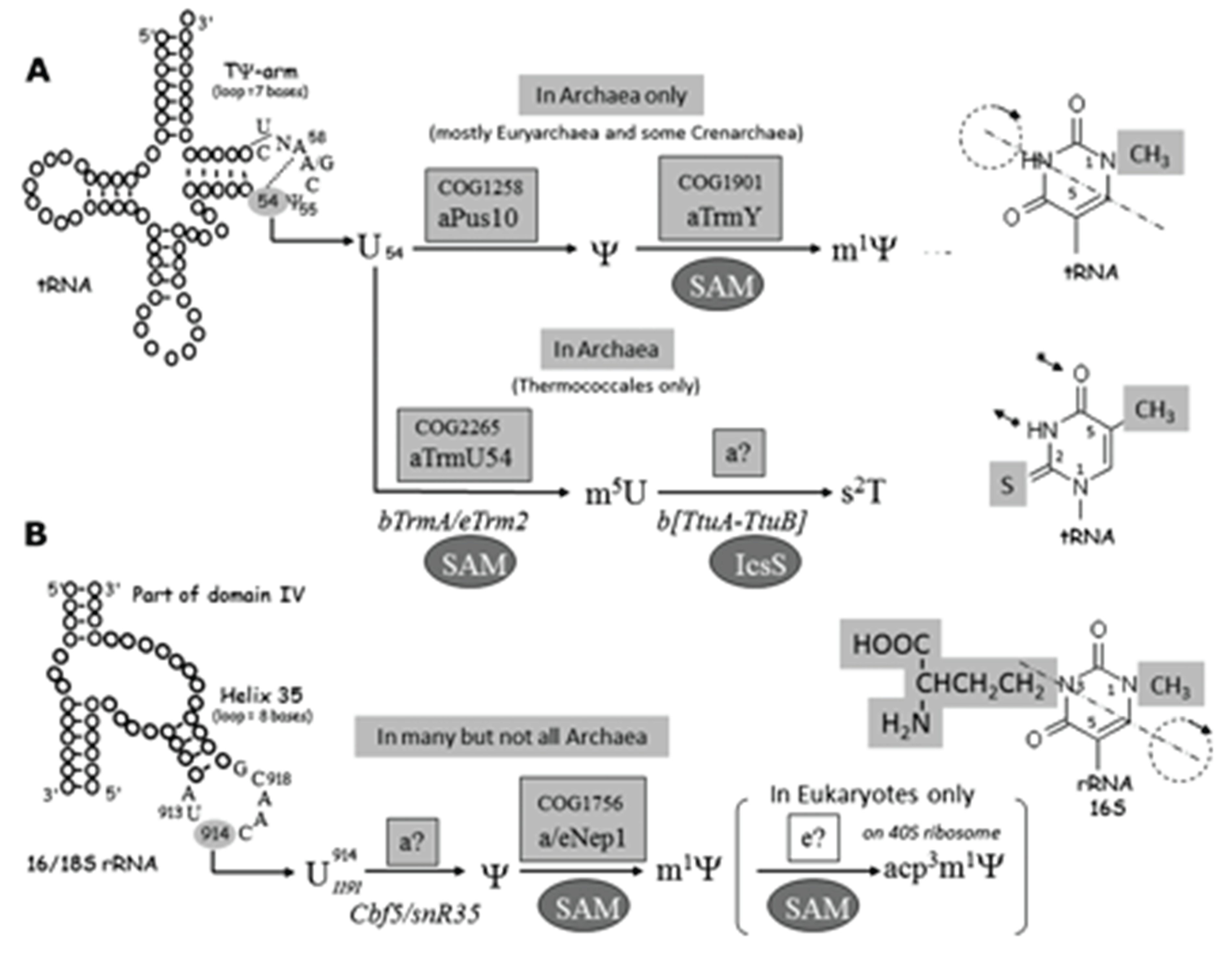

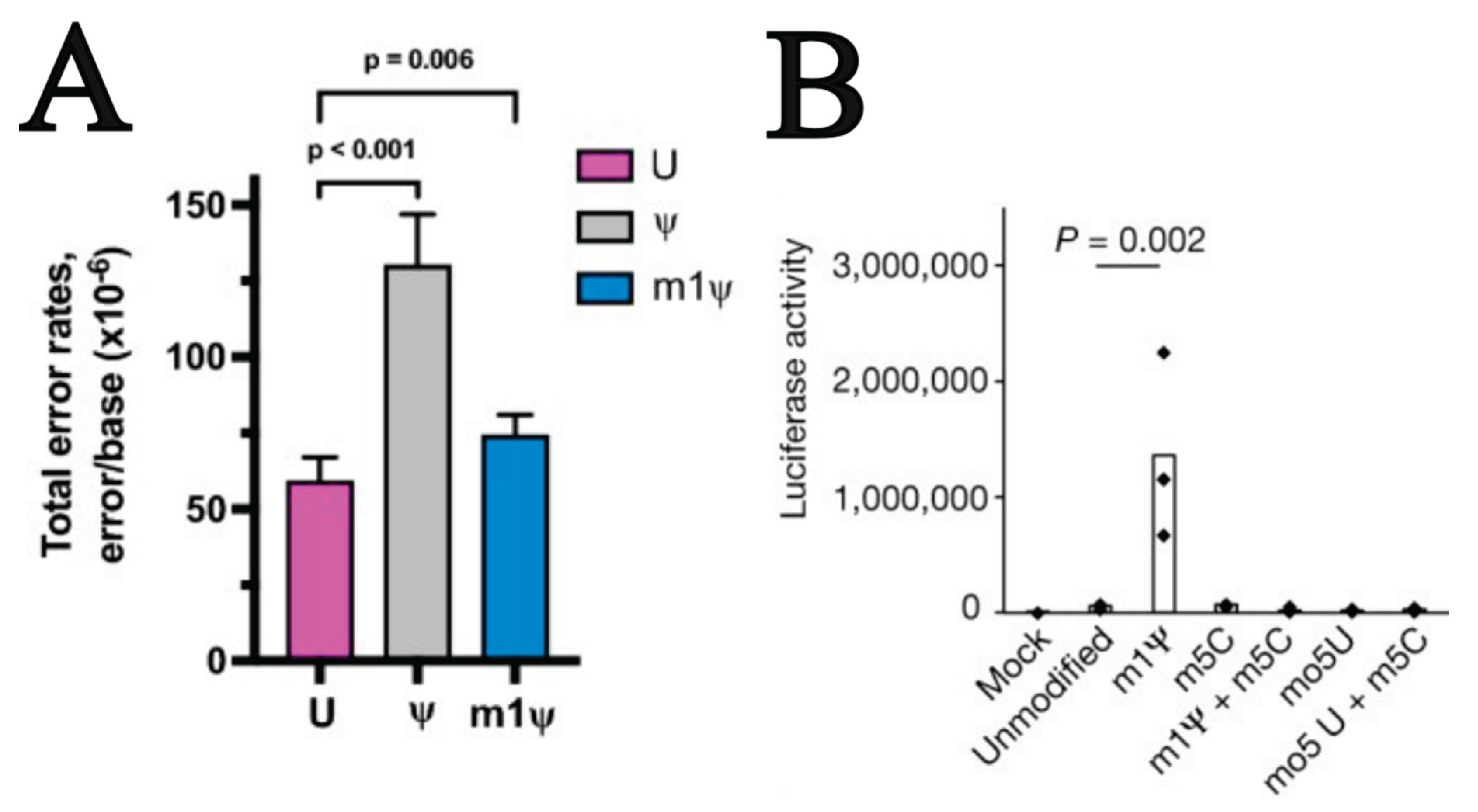

The Biology of Ψ and m1Ψ

Important Differences from Uridine

Resolution: Moving Forward with mRNA

References

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, complete genome [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 May 3]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_045512.2.

- Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Porter FW, Weissman D. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 261–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary N, Weissman D, Whitehead KA. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 817–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng F, Wang Y, Bai Y, Liang Z, Mao Q, Liu D, et al. Research Advances on the Stability of mRNA Vaccines. Viruses 2023, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgin E. The tangled history of mRNA vaccines. Nature. 2021 Sep 14;597(7876):318–24.

- Karikó K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D. Suppression of RNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptors: The Impact of Nucleoside Modification and the Evolutionary Origin of RNA. Immunity 2005, 23, 165–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardi N, Tuyishime S, Muramatsu H, Kariko K, Mui BL, Tam YK, et al. Expression kinetics of nucleoside-modified mRNA delivered in lipid nanoparticles to mice by various routes. J Control Release Off J Control Release Soc. 2015 Nov 10;217:345–51.

- Monroe J, Eyler DE, Mitchell L, Deb I, Bojanowski A, Srinivas P, et al. N1-Methylpseudouridine and pseudouridine modifications modulate mRNA decoding during translation. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 8119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim KQ, Burgute BD, Tzeng SC, Jing C, Jungers C, Zhang J, et al. N1-methylpseudouridine found within COVID-19 mRNA vaccines produces faithful protein products. Cell Rep [Internet]. 2022 Aug 30 [cited 2022 Oct 5];40(9). Available from: https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/abstract/S2211-1247(22)01120-2.

- Melton DA, Krieg PA, Rebagliati MR, Maniatis T, Zinn K, Green MR. Efficient in vitro synthesis of biologically active RNA and RNA hybridization probes from plasmids containing a bacteriophage SP6 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984, 12, 7035–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone RW, Felgner PL, Verma IM. Cationic liposome-mediated RNA transfection. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989 Aug;86(16):6077–81.

- Felgner PL, Wolff JA, Rhodes GH, Malone RW, Carson DA. Induction of a protective immune response in a mammal by injecting a DNA sequence. Biotechnol Adv. 1997;15(3–4):663.

- Alberer M, Gnad-Vogt U, Hong HS, Mehr KT, Backert L, Finak G, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a mRNA rabies vaccine in healthy adults: an open-label, non-randomised, prospective, first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017 Sep 23;390(10101):1511–20.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 31;383(27):2603–15.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 4;384(5):403–16.

- Cohn WE, Volkin E. Nucleoside-5′-Phosphates from Ribonucleic Acid. Nature. 1951 Mar;167(4247):483–4.

- Cortese R, Kammen HO, Spengler SJ, Ames BN. Biosynthesis of Pseudouridine in Transfer Ribonucleic Acid. J Biol Chem. 1974 Feb 25;249(4):1103–8.

- Karikó K, Muramatsu H, Welsh FA, Ludwig J, Kato H, Akira S, et al. Incorporation of Pseudouridine Into mRNA Yields Superior Nonimmunogenic Vector With Increased Translational Capacity and Biological Stability. Mol Ther. 2008 Nov 1;16(11):1833–40.

- Argoudelis AD, Mizsak SA. 1-methylpseudouridine, a metabolite of Streptomyces platensis. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1976 Aug;29(8):818–23.

- Earl RA, Townsend LB. A chemical synthesis of the nucleoside 1-methylpseudouridine. J Heterocycl Chem. 1977;14(4):699–700.

- Pang H, Ihara M, Kuchino Y, Nishimura S, Gupta R, Woese CR, et al. Structure of a modified nucleoside in archaebacterial tRNA which replaces ribosylthymine. 1-Methylpseudouridine. J Biol Chem. 1982 Apr 10;257(7):3589–92.

- Gupta R. Halobacterium volcanii tRNAs. Identification of 41 tRNAs covering all amino acids, and the sequences of 33 class I tRNAs. J Biol Chem. 1984 Aug 10;259(15):9461–71.

- Wurm JP, Griese M, Bahr U, Held M, Heckel A, Karas M, et al. Identification of the enzyme responsible for N1-methylation of pseudouridine 54 in archaeal tRNAs. RNA. 2012 Mar;18(3):412–20.

- Andries O, Mc Cafferty S, De Smedt SC, Weiss R, Sanders NN, Kitada T. N1-methylpseudouridine-incorporated mRNA outperforms pseudouridine-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and mice. J Controlled Release. 2015 Nov 10;217:337–44.

- Nance KD, Meier JL. Modifications in an Emergency: The Role of N1-Methylpseudouridine in COVID-19 Vaccines. ACS Cent Sci. 2021 May 26;7(5):748–56.

- Bansal A. From rejection to the Nobel Prize: Karikó and Weissman’s pioneering work on mRNA vaccines, and the need for diversity and inclusion in translational immunology. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2023 Nov 8 [cited 2025 May 5];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.orghttps://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1306025/full.

- Mulroney TE, Pöyry T, Yam-Puc JC, Rust M, Harvey RF, Kalmar L, et al. N1-methylpseudouridylation of mRNA causes +1 ribosomal frameshifting. Nature. 2024 Jan;625(7993):189–94.

- Thess A, Grund S, Mui BL, Hope MJ, Baumhof P, Fotin-Mleczek M, et al. Sequence-engineered mRNA Without Chemical Nucleoside Modifications Enables an Effective Protein Therapy in Large Animals. Mol Ther J Am Soc Gene Ther. 2015 Sep;23(9):1456–64.

- Buschmann MD, Carrasco MJ, Alishetty S, Paige M, Alameh MG, Weissman D. Nanomaterial Delivery Systems for mRNA Vaccines. Vaccines. 2021 Jan;9(1):65.

- Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Kirschning C, Akira S, et al. Species-Specific Recognition of Single-Stranded RNA via Toll-like Receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004 Mar 5;303(5663):1526–9.

- Kremsner PG, Guerrero RAA, Arana E, Aroca Martinez GJ, Bonten MJ, Chandler R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the CVnCoV SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine candidate: results from herald, a phase 2b/3, randomised, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial in ten countries in Europe and Latin America.

- CureVac Comes Around [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 27]. Available from: https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/curevac-comes-around.

- Liu A, Wang X. The Pivotal Role of Chemical Modifications in mRNA Therapeutics. Front Cell Dev Biol [Internet]. 2022 Jul 13 [cited 2024 Oct 5];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cell-and-developmental-biology/articles/10.3389/fcell.2022.901510/full.

- Diebold SS, Massacrier C, Akira S, Paturel C, Morel Y, Reis e Sousa C. Nucleic acid agonists for Toll-like receptor 7 are defined by the presence of uridine ribonucleotides. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(12):3256–67.

- Rubio-Casillas A, Cowley D, Raszek M, Uversky VN, Redwan EM. Review: N1-methyl-pseudouridine (m1Ψ): Friend or foe of cancer? Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 May 1;267:131427.

- Svitkin YV, Cheng YM, Chakraborty T, Presnyak V, John M, Sonenberg N. N1-methyl-pseudouridine in mRNA enhances translation through eIF2α-dependent and independent mechanisms by increasing ribosome density. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 Jun 2;45(10):6023–36.

- Uchida S, Kataoka K, Itaka K. Screening of mRNA Chemical Modification to Maximize Protein Expression with Reduced Immunogenicity. Pharmaceutics. 2015 Sep;7(3):137–51.

- Krammer F, Palese P. Profile of Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman: 2023 Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2024 Feb 27;121(9):e2400423121.

- Watson OJ, Barnsley G, Toor J, Hogan AB, Winskill P, Ghani AC. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Sep 1;22(9):1293–302.

- Allen, FW. The Biochemistry of the Nucleic Acids, Purines, and Pyrimidines. Annu Rev Biochem. 1941 Jul 1;10(Volume 10, 1941):221–44.

- Ontiveros RJ, Stoute J, Liu KF. The chemical diversity of RNA modifications. Biochem J. 2019 Apr 26;476(8):1227–45.

- Frye M, Harada BT, Behm M, He C. RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science. 2018 Sep 28;361(6409):1346–9.

- Gilbert, WV. Recent developments, opportunities, and challenges in the study of mRNA pseudouridylation. RNA. 2024 May;30(5):530–6.

- Borchardt EK, Martinez NM, Gilbert WV. Regulation and Function of RNA Pseudouridylation in Human Cells. Annu Rev Genet. 2020 Nov 23;54:309–36.

- Franzmann PD, Springer N, Ludwig W, Conway De Macario E, Rohde M. A Methanogenic Archaeon from Ace Lake, Antarctica: Methanococcoides burtonii sp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992 Dec 1;15(4):573–81.

- Fu L, Zhou T, Wang J, You L, Lu Y, Yu L, et al. NanoFe3O4 as Solid Electron Shuttles to Accelerate Acetotrophic Methanogenesis by Methanosarcina barkeri. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2019 Mar 5 [cited 2024 Oct 12];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00388/full.

- Toso DB, Javed MM, Czornyj E, Gunsalus RP, Zhou ZH. Discovery and Characterization of Iron Sulfide and Polyphosphate Bodies Coexisting in Archaeoglobus fulgidus Cells. Archaea. 2016;2016(1):4706532.

- Ossmer R, Mund T, Hartzell PL, Konheiser U, Kohring GW, Klein A, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of component C of the methylreductase system in Methanococcus voltae and Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986 Aug;83(16):5789–92.

- Mukhopadhyay B, Johnson EF, Wolfe RS. A novel pH2 control on the expression of flagella in the hyperthermophilic strictly hydrogenotrophic methanarchaeaon Methanococcus jannaschii. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000 Oct 10;97(21):11522–7.

- Mochimaru H, Tamaki H, Katayama T, Imachi H, Sakata S, Kamagata Y. Methanomicrobium antiquum sp. nov., a hydrogenotrophic methanogen isolated from deep sedimentary aquifers in a natural gas field. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66(11):4873–7.

- Legat A, Gruber C, Zangger K, Wanner G, Stan-Lotter H. Identification of polyhydroxyalkanoates in Halococcus and other haloarchaeal species. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010 Jul 1;87(3):1119–27.

- de Silva RT, Abdul-Halim MF, Pittrich DA, Brown HJ, Pohlschroder M, Duggin IG. Improved growth and morphological plasticity of Haloferax volcanii. Microbiology. 2021;167(2):001012.

- Stan-Lotter H, Fendrihan S. Halophilic Archaea: Life with Desiccation, Radiation and Oligotrophy over Geological Times. Life. 2015 Sep;5(3):1487–96.

- Kashefi K, Moskowitz BM, Lovley DR. Characterization of extracellular minerals produced during dissimilatory Fe(III) and U(VI) reduction at 100 °C by Pyrobaculum islandicum. Geobiology. 2008;6(2):147–54.

- Thermoproteus neutrophilus - microbewiki [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 6]. Available from: https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Thermoproteus_neutrophilus.

- Burggraf S, Fricke H, Neuner A, Kristjansson J, Rouvier P, Mandelco L, et al. Methanococcus igneus sp. nov., a Novel Hyperthermophilic Methanogen from a Shallow Submarine Hydrothermal System. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990 Aug 1;13(3):263–9.

- Stetter KO, Thomm M, Winter J, Wildgruber G, Huber H, Zillig W, et al. Methanothermus fervidus, sp. nov., a novel extremely thermophilic methanogen isolated from an Icelandic hot spring. Zentralblatt Für Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg Abt Orig C Allg Angew Ökol Mikrobiol. 1981 Aug 1;2(2):166–78.

- Jones JB, Bowers B, Stadtman TC. Methanococcus vannielii: ultrastructure and sensitivity to detergents and antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1977 Jun;130(3):1357–63.

- Chatterjee K, Blaby IK, Thiaville PC, Majumder M, Grosjean H, Yuan YA, et al. The archaeal COG1901/DUF358 SPOUT-methyltransferase members, together with pseudouridine synthase Pus10, catalyze the formation of 1-methylpseudouridine at position 54 of tRNA. RNA. 2012 Mar;18(3):421–33.

- Dutta N, Deb I, Sarzynska J, Lahiri A. Structural and Thermodynamic Consequences of Base Pairs Containing Pseudouridine and N1-methylpseudouridine in RNA Duplexes. ChemistrySelect. 2025;10(4):e202400006.

- Chen TH, Potapov V, Dai N, Ong JL, Roy B. N1-methyl-pseudouridine is incorporated with higher fidelity than pseudouridine in synthetic RNAs. Sci Rep. 2022 Jul 29;12(1):13017.

- Song, Y. Tweaks in vaccine. Nat Chem Biol. 2024 Feb;20(2):131–131.

- Dong Y, Anderson DG. Opportunities and Challenges in mRNA Therapeutics. Acc Chem Res. 2022 Jan 4;55(1):1–1.

- Rohner E, Yang R, Foo KS, Goedel A, Chien KR. Unlocking the promise of mRNA therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 2022 Nov;40(11):1586–600.

- Ball, P. The lightning-fast quest for COVID vaccines — and what it means for other diseases. Nature. 2020 Dec 18;589(7840):16–8.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).