1. Introduction

1.1. The Healing Gaze: Art Fruition, Stress Relief, and the Brain

Contemplation and engagement with visual art has been increasingly recognized for its beneficial effects on psychological well-being. The typical psychological responses to aesthetic experience, defined as the emotional response to the intrinsic, non-utilitarian qualities of an artwork, are increased mindfulness, and positive mood [

1,

2]. In fact, research indicates that both the creation and appreciation of art can serve as preventive interventions, reducing psychological distress, enhancing self-awareness, promoting behavioral change, and modulating physiological responses such as heart rate, blood pressure, and cortisol levels [

3,

4,

5,

6]. All these indices describe a psychophysiological state characterized by reduced stress and a higher sense of relaxation. However, art fruition can also elicit feelings of privilege, inspiration, and emotional insight, even in vulnerable individuals such as the elderly or those with chronic mental illness [

7,

8]. For example, in a study of 300 hospital patients and care home residents, object handling sessions have been shown to foster social interaction, increase vitality, stimulate tactile engagement, and promote a sense of identity and self-worth [

9,

10].

As detailed in the review by Mastandrea and colleagues [

2], and taking inspiration from the results obtained in the music fruition field, the experience of pleasure in visual art reception could emerge from a dynamic interplay of processes, including: (1) the affective resonance with the emotional valence expressed by the artwork; (2) the cognitive appraisal of negative emotional content in a safe and sublimating space; (3) the consequent regulation of emotional responses; and (4) the engagement in aesthetic appreciation and active judgment. To explain these effects, both emotional and cognitive mechanisms have been considered among which memory, identity reinforcement, and meaning-making [

11,

12].

Neuroscientific investigations have shed light on the neural underpinnings of aesthetic experience. Visual art appreciation is associated with brain activations in areas devoted to higher level emotional processing, decision-making, and the reward system, such as the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), the anterior cingulate cortex (aCC), and the striatum [

2,

13,

14,

15], reinforcing the idea that both cognitive and affective processes are engaged during aesthetic appreciation [

16].

1.2. Healing Spaces: Psychological and Neural Effects of Museum Collections

In recent years, museums have been designated as new spaces of choice for promoting visitor well-being, particularly in the context of mental health [

9,

17,

18,

19]. Museum-based programs offering activities such as guided tours, object handling, mindfulness, and creative workshops have been developed for a range of populations, including older adults, individuals with dementia, and psychiatric patients [

8,

20,

21], but also the general public [

4]. Qualitative and quantitative studies consistently report that participation in museum activities can improve subjective well-being, reduce anxiety, and enhance mood [

4,

8,

9,

22]. Increased optimism, hope, and enjoyment have been reported as contributing factors, along with the reduction of social isolation, the opportunity to learn new concepts and skills, with subsequent enhanced self-esteem and sense of identity [

7].

A notable example is the Museums on Prescription initiative, where museum-based social prescribing was associated with significant pre-post improvements in emotional states such as absorption, enlightenment, and cheerfulness [

8]. Importantly, participants also valued opportunities to engage with curators and artifacts, suggesting that co-creative, interactive approaches maximize therapeutic potential. These findings support the reconceptualization of museums as inclusive, community-based environments capable of facilitating health-related outcomes beyond clinical settings [

20,

23].

Although still a growing field, early evidence from neuroaesthetics and museum studies suggests that the museum setting itself may amplify the neural effects of aesthetic experience. The architectural and curatorial features of museums, characterized by spatial focus, reduced cognitive noise, and multisensory richness, are hypothesized to support attentional engagement, emotional regulation, and reflective thought [

2,

4,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Neuroimaging research conducted in ecologically valid environments indicates that museum visits can modulate neural activity associated with stress and emotional processing. For instance, viewing figurative art in situ can lead to decreased physiological arousal [

5] and improved mood, particularly when context enhances understanding of the artwork [

28].

While imaging methods can provide meaningful insights into aesthetic preference in experimental contexts, electrophysiological data seem more promising in ecologically valid settings, such as a museum visit, when conducted with portable devices.

1.3. Electrophysiological Markers of Anxiety

Anxiety and stress are known to correlate with attentional control and executive functions. In the context of cognitive performance anxiety (CPA), top-down attentional control, mediated by the prefrontal cortex (PFC), fails to override the stress-induced processing of threat-related information. This disruption occurs because attentional control is governed by a dual-process system: bottom-up (posterior/subcortical) and top-down (anterior/prefrontal) networks. Anxiety disturbs the balance between these systems, enhancing stimulus-driven attention and consequently increasing the detection and processing of threat-related stimuli [

29].

Several studies investigating EEG slow/fast rhythm dynamic suggest that the spontaneous change in the ratio between theta (4-7 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) might indicate significant shifts in emotional/cognitive spheres. In particular, theta/beta ratio (TBr) seems to reflect cortical-subcortical interactions, specifically those involved in emotional states, dispositional affective traits, and emotion regulation [

30]. Elevated TBr has been observed in the inattentive subtype of attention deficit disorder (ADD) and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), reinforcing its association with stable affective traits (e.g., anxiety and behavioral inhibition), incentive motivation, risky decision-making, and impaired inhibitory control (i.e., attentional bias to threat) [

31]. Similarly, low frontal TBR has been shown to predict resilience under stress-induced impairments in attentional control. For example, performance on an emotional go/no-go task revealed an inverse correlation between frontal TBR and fearful modulation of response inhibition, as well as with self-assessed indices of attentional control and anxiety. Higher slow/fast EEG ratios have also been linked to reduced adaptive anxiogenic responses, characterized by more inhibited reactions to fearful, rather than happy, facial expressions [

32]. TBr is therefore considered an electrophysiological marker of executive cognitive control, which moderates the effects of CPA-like effects on attentional control. Higher TBR scores then indicate greater slow-wave power (i.e., subcortical control) relative to fast-wave power (i.e., cortical control).

In line with prior research utilizing portable EEG systems, we corroborate the finding that anxiety states elevate theta oscillations in the PFC and that the eyes-closed condition, rather than the eyes-open condition, more reliably predicts anxiety levels following the task [

33]. Thus, the TBr has been established as a reliable marker of attentional control over emotional stimuli, positioning it as a promising tool for investigating cognitive-affective regulation, particularly in contexts involving stress and anxiety.

Previous research already tested the feasibility and usability of EEG data in museum contexts [

34] and highlighted promising results related to visitors’ engagement [

35]. However, the identification of neural signatures related to the effectiveness of interventions aimed at stress reduction needs further investigation.

1.4. The Present Study

Despite the growing body of evidence supporting the beneficial impact of museum experiences on psychological and neurocognitive well-being, the literature still lacks approaches for tailoring such interventions to individual needs by identifying those most likely to benefit. This limitation reflects a broader gap in our understanding of the neural markers that predict responsiveness to art-based experiences. The aim of this study was to address this gap. It was not only meant to explore the beneficial effects of museum visits on stress reduction, but also to identify the neural correlates underlying individual differences in the impact of museum visits. This could potentially support the findings on clinical population, but hopefully to extend our knowledge on the general public, supporting the broader application of art-based interventions on psychological well-being [

18,

36].

The present study is part of a larger protocol, called ASBA Project (Anxiety, Stress, Brain-friendly Museum Approach) [

17] which integrates electrophysiological and psychometric assessments to evaluate the effectiveness of targeted museum experiences in reducing perceived stress. Launched in October 2022, the project was proposed in both fine art and natural history museum settings in Milan and Turin and was targeted at both general visitors and museum staff [

4].

In this study participants were involved in an interactive museum visit. Before and after the intervention, both self-reported measures (perceived stress) and electrophysiological responses were recorded using a brain computer interface (BCI) device. By combining subjective and psychophysiological measures, we aim to provide further insight into how cultural participation within museum contexts contributes to resilience, mood regulation, and overall mental health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty-five healthy adults (M

age=32.29, SD =7.8) aged 18-54 participated in the experiment (see

Table 1) either at the Modern Art Gallery (MAG) or the Natural History Museum (NHM; Milan, Italy). Eighteen of them visited the MAG and 17 visited the NHM. The sample was composed of 26 women (74%) and 9 men (26%). More than 54% of them reported visiting museums more than 6 times a year; 21.5% and 19% have an attendance of 3-5 and 1-2 times a week, respectively. Just 5.1% never visit a museum throughout the year.

The recruitment process entailed posting the call for applications on the websites of the participating universities, as well as on local government and museum websites. To include people of various ages, social, economic, and cultural backgrounds, the project received the most publicity possible. Through the websites, participants could access the project page, schedule the visit date, and read the informed consent. The consent explained all the procedures in detail, along with the objectives and the risks of the study. It also included a detailed section explaining the participant’s right to withdraw from the study at any stage, along with the privacy policy. Then, upon agreeing to the terms, participants completed the initial demographic questionnaire. This questionnaire was used to gather personal data and determine inclusion and exclusion criteria. Participants then filled out the psychological traits questionnaires and were assigned to a given study session (see the Procedure section).

Inclusion criteria:

- -

Being 18 years old or older.

- -

Accepting the conditions for participation and having signed the informed written consent.

Exclusion criteria:

- -

Insufficient language skills in understanding verbal assignments and interacting with presenters and peers;

- -

Current diagnosis of a disease of psychiatric or neurological nature;

- -

Uncorrected visual or hearing impairment;

- -

Another medical condition that can negatively affect the activities to be performed.

The study was conducted with the understanding and written consent of the participants, who had been informed of the research procedures and purposes according to the Declaration of Helsinki and with the approval from the local Ethical Committee (University of Milano-Bicocca; protocol code: 733).

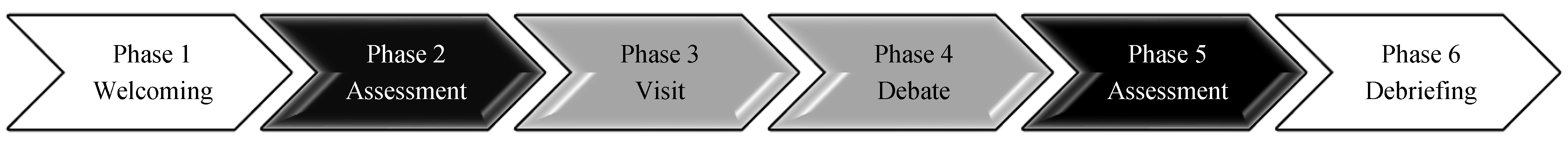

2.2. Procedure (see Fig. 1)

2.2.1. Procedure Phase 1: Welcoming Procedures

On the day of the session, participants were welcomed in a designated area of the museum and a check-in was carried out to verify the correct completion of the questionnaire and the sign of the informed consent. As soon as all the participants in the session arrived, they were led to a boardroom in the museum used for the presentation of the study. Here, the most important information about the study was reiterated, and professionals and researchers involved were introduced, together with a brief presentation of the Brain-computer interface technique.

2.2.2. Procedure Phase 2: Pre-Visit Assessment.

Then, pre-treatment questionnaires were administered, which were designed to measure state anxiety levels (SAI) and mood (VAS scales) (see below). EEG measure was recorded for two minutes in a quiet condition. Participants could choose any seat in the large hall, to encourage comfort and self-confidence.

2.2.3. Procedure Phase 3: The Visit

Small groups (7 to 10 participants) were then formed and accompanied by a museum expert in an interactive visit of some museum’ rooms. Space and time allocated to each group were standardized so that all had a similar experience. Each group had 90 minutes to conclude the visit.

2.2.4. Procedure Phase 4: Debate

Following the visit, a discussion on the experience was led by the conductor after moving the chairs in a circle to facilitate sharing. In this space, each participant could share their feelings and opinions on what they had experienced, including which artifact (or part of it) they had focused on. In the case of the art museum, the aim was to place the work in its historical and aesthetic context and to link this information to what participants reported about their experience. In the case of the science museum, the characteristics of the various animals and plant species that were present in the dioramas were illustrated, together with geographical coordinates to allow participants to better understand their experience and to acquire knowledge. This phase lasted 30 minutes.

2.2.5. Procedure Phase 5: Post-Treatment Assessment

At the end of the discussion, participants were accompanied back to the boardroom and EEG measure (through BCI) was then recorded for two minutes in a quiet condition. Participants were then asked to fill in the post-treatment questionnaires, which were identical to those of the pre-experience phase, except for an additional space at the end of the document for them to make a general comment on the experience and to give it a title as if it were a movie

2.2.6. Procedure Phase 6: Debriefing

At the end of the post-experience evaluation, participants could ask further questions to the professionals and researchers, as well as receive further information on future developments of the study, or where to find information for further investigation.

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of the experimental procedure.

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of the experimental procedure.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Recruitment Questionnaire

For each new slot available, one month before the beginning of the sessions, the calendar for registration was made available to the public. The day before the session, the registration closed to allow researchers to check for eligibility and completeness of the data. The response rate was highest especially in the first available slots, decreasing throughout the following slots. However, each session never hosted less than 10 participants.

Demographic information and relationship with the museum. The questionnaire included sociodemographic information such as gender (female, male, other, prefer not to say) and age, along with information related to participants' habits with respect to museum visits (annual attendance at any type of museum with 4 choice ranges: never; 1-2 times; 3-5 times; > 6 times) and their preferences (interest in art and science museums on a Likert scale from 1: not at all, to 10: very much).

The State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; [

37]), is the most widely used tool in the scientific literature for the psychometric measurement of anxiety. The theory of state and trait anxiety, which distinguishes between current anxiety and readiness for anxious reaction as a personality trait, now appears to be supported by both clinical evidence and numerous experimental studies. The brevity of the questionnaire and the simple formulation of the items makes it very easy to administer and ensures good validity of the scores obtained. The STAI questionnaire consists of two separate scales to measure two distinct anxiety constructs: State Anxiety Inventory (SAI) and Trait Anxiety Inventory (TAI). Both scales consist of 20 statements where participants are asked to describe how they generally feel, on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). In the recruitment questionnaire, just the TAI was administered. The SAI, instead, was applied during the pre/post-assessment phases (see ahead).

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; [

38]) is the most widely used psychological instrument for measuring the perception of stress. It is a measure of the degree to which situations in a person's life are rated as stressful. The items were constructed to intercept the degree to which people find their lives unpredictable, uncontrollable, or overloaded. The scale also contains a series of direct questions about current levels of perceived stress. Both the items and the alternatives are easy to understand. In addition, the questions are general and thus free of content specific to any subpopulation. The PSS questions concern feelings and thoughts related to the last month. For each item, people are asked to indicate how often they felt a certain way, from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Scores higher than 27 are considered high, while people with a score lower than 14 are considered with no stress.

2.3.2. Pre and Post-Experience Assessment Questionnaires

SAI. To assess the changes in State Anxiety, the SAI scale was administered both before and after the museum visit (pre and post-experience assessment) following a pre/post-protocol similar to Binnie [

22], who reported positive results after a museum visit. The scale can detect short-term changes in anxiety levels thanks to its good psychometrics parameters, as shown in many previous studies (e.g. [

39,

40,

41]). As mentioned above, the scale includes 20 statements where participants are asked to describe how they feel in the present moment, on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

MOOD-VAS. Six visual-analogue scales (VAS) [

42] were presented to assess participants' moods and states of mind before and after museum visits. The first question was about general mood, i.e., "How do you rate your mood right now?" with a choice among 10 steps from 1 (negative) to 10 (positive). The next 5 questions required assessing the intensity of certain states of mind experienced at the present moment, from 1 (absent state) to 10 (very present state), and specifically: stress; mental clarity; contentment; calmness; restlessness.

Brain-computer interface (BCI). BCI is used to measure real-time brain activity and potentially translate it into commands that can be used to control devices [

43]. In medicine, BCIs have demonstrated their potential in helping people with various conditions. For example, BCIs have been used to help people with paralysis regain some level of control over their movements by translating their brain activity into control signals for prosthetic limbs [

44,

45]. BCIs have also been used to help people with epilepsy detect and prevent seizures [

46,

47]. Like traditional EEG, BCI systems are powerful and comfortable tools to record biosignals from the scalp. However, BCI are generally wireless and more wearable than traditional EEG. Furthermore, we used a device based on dry electrodes to reduce related negative effects on participants’ experience in a real-world setting like a museum. Considering the research aims, it was important that participants could have a meaningful and enriching experience. Thus, we used a commercial BCI device, MUSE headband, that is easily wearable and provides 4 electrodes (2 frontal and 2 temporal-posterior). Furthermore, only resting pre- and post-experience EEG activity was recorded, so not to interfere with the visit experience. Each device was then connected to a smartphone via Bluetooth and participants’ brain activity was then recorded in a comfortable seat inside a room of the museum without interacting with other participants. The EEG sessions lasted 2 minutes each (pre- and post-experience): 1-minute eyes open and 1-minute eyes closed. Participants were asked to stay relaxed maintaining a comfortable position, limiting movement and distractions. The cue to close the eyes was given one minute after the beginning of the recording session using a soft dingle.

3. Results

The analyses have been conducted by using SPSS Statistics version 28.0.1.1 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

First, descriptive statistics have been performed to give a picture of the participants’ profiles. Most of them reported visiting museums regularly and to be into the subjects of art or science. Regarding psychological traits,

Table 1 reports participants’ trait anxiety levels, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) scores and a self-evaluation of their own stress.

Table 1.

Mean values of Trait Anxiety scores (TAI), Perceived Stress scores (PSS), and stress assessment in the last month, for the two samples.

Table 1.

Mean values of Trait Anxiety scores (TAI), Perceived Stress scores (PSS), and stress assessment in the last month, for the two samples.

| Museum |

|

N |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

SD |

| MAG |

Trait Anxiety |

17 |

25 |

61 |

44,57 |

9.37 |

| |

Perceived Stress |

17 |

7 |

37 |

19,14 |

6.53 |

| |

Stress_last month |

17 |

3 |

10 |

7,14 |

1.91 |

| NHM |

Trait Anxiety |

16 |

31 |

62 |

49,44 |

8.89 |

| |

Perceived Stress |

16 |

10 |

32 |

20,78 |

5.84 |

| |

Stress_last month |

16 |

2 |

9 |

8,00 |

1.71 |

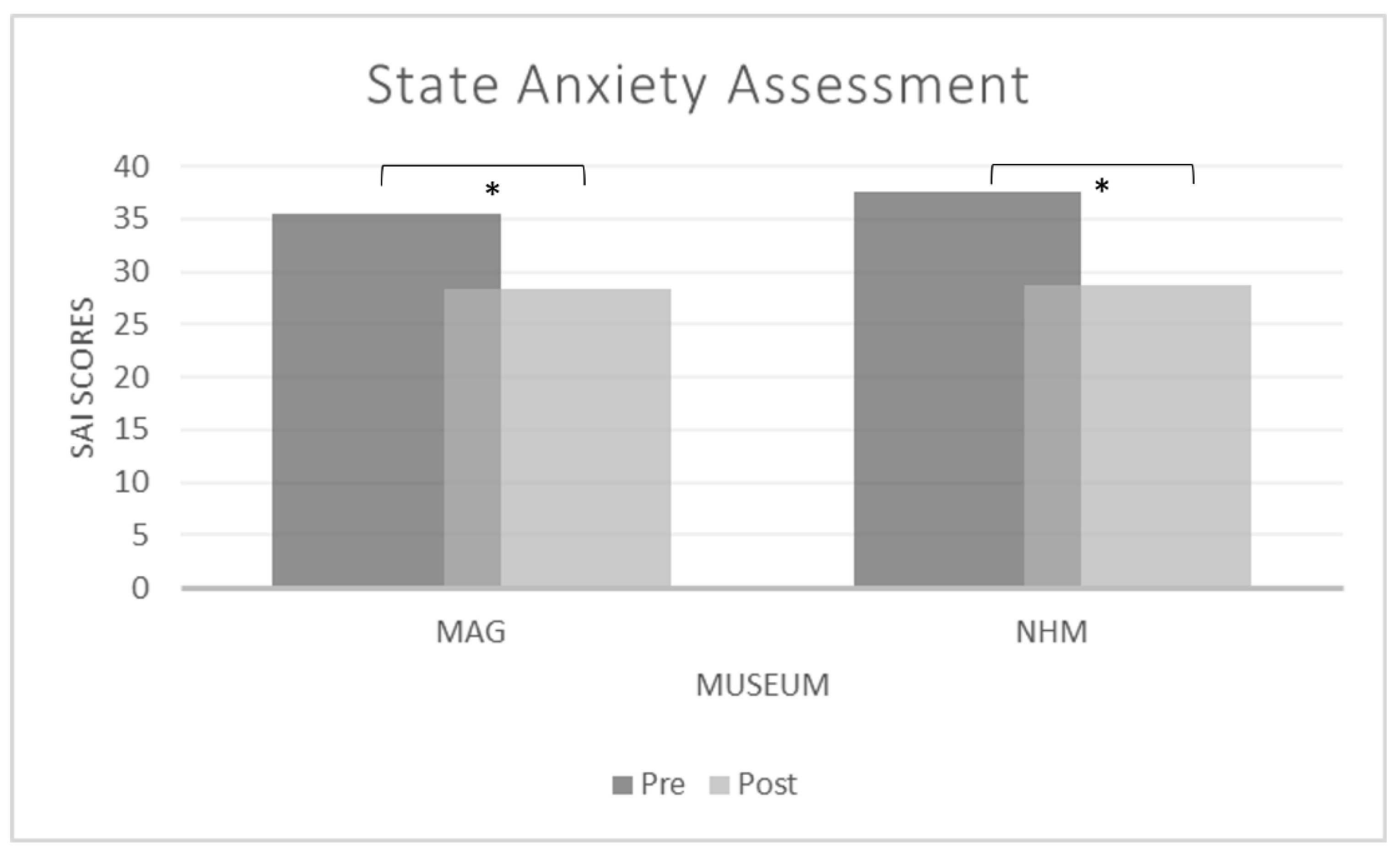

3.2. Changes in Anxiety Levels After the Visit

To assess whether visiting museums had caused changes in state anxiety or mood levels, paired-sample t-tests were conducted for the measures of interest including SAI and VAS. Since the purpose of the study was not to compare the two museums with each other, we did not perform a mixed model.

The t-tests revealed significant results for all the dependent variables: SAI, mood, stress, mental clarity, contentment, calmness, restlessness (see

Table 2).

In detail, anxiety levels, stress, and restlessness proved to be significantly decreased after the activities in the museum, while mood, mental clarity, contentment, and calmness were increased (see

Table 3).

The visit was able to significantly reduce state anxiety in both museum settings (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Histograms of the SAI scores as recorded before (dark grey) and after (light grey) the visit to the Arts (left) and Science (right) Museums.

Figure 2.

Histograms of the SAI scores as recorded before (dark grey) and after (light grey) the visit to the Arts (left) and Science (right) Museums.

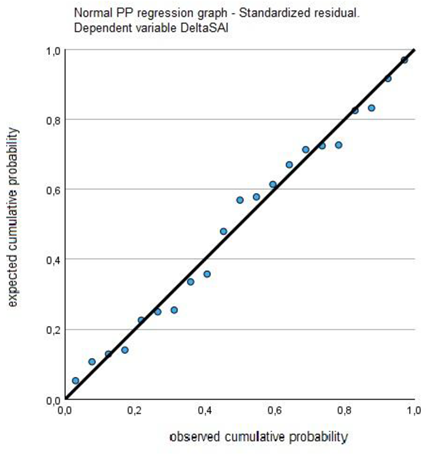

3.3. BCI and Psychological Measures Pre-Post Changes

A correlation analysis was performed to explore if different psychological variables and the EEG measures showed significant relationships. Both state and trait measures were input to analyze possible mediating effects. For EEG measures, the power of each EEG range was considered (delta, theta, alpha, beta and gamma) in pre- and post- assessment, as well as the Theta/Beta ratio (TBR) that was chosen based on the literature as main state-anxiety index (see par. 1.3). The Pearson r statistics revealed that the pre-visit SAI correlated only with PSS scale, while the post-visit SAI correlated only with the trait anxiety score. Then, delta scores were also computed to obtain SAI and TBr change after the intervention (ΔSAI=SAIpost-SAIpre; ΔTBr=TBrpost-TBrpre). The post-pre anxiety difference (ΔSAI), and thus the change in SAI after the visit, was correlated only with the post-pre TBr difference (ΔTBr). No other EEG value correlated with state anxiety.

Starting from the above data, a linear regression analysis was run using SAI change (ΔSAI) as dependent variable and trait anxiety (TAI), trait perceived stress (PSS) and TBR change (ΔTBr) as predictors.

As table 4 shows, the best predictor of the state anxiety changes (ΔSAI) is the change in TBR (ΔTBr), that is the difference between the average power of the Theta/Beta ratio pre- and post-experience (R

2 = .441).

Table 4.

Linear regression model with ΔSAI as dependent variable.

Table 4.

Linear regression model with ΔSAI as dependent variable.

| |

B |

SE |

Beta |

|

p |

| (Costant) |

-16.482 |

7.081 |

|

-2.328 |

.033 |

| ΔTBr |

-.807 |

.242 |

-.519 |

-3.333 |

.004 |

| PSS |

-.405 |

.185 |

-.354 |

-2.187 |

.043 |

| TAI |

.450 |

.161 |

.440 |

2.802 |

.012 |

However, trait anxiety and the level of perceived stress are, as predicted, also associated with the change in state anxiety. In particular, the higher the state anxiety, the greater the change that can be expected in terms of state anxiety. At the opposite, the baseline level of perceived stress (PSS score, which refers to the previous month) seems to have an inverse relationship: the lower the stress, the higher the change.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was twofold: the first goal (I) was to explore the beneficial effects of museum visits on stress reduction; the second goal (II) was to identify the neural correlates underlying individual differences in the impact of museum visits.

Starting from the first aim, the analyses conducted on state anxiety before and after the visit demonstrated that all the dependent variables improved, with increased calmness and better mood, and a decrease in perceived stress, anxiety, and restlessness. Thus, we can conclude that this study supports previous evidence conducted in museum settings that report a greater well-being effect in relation to various experiences [

4,

8,

9,

22].

A particularly compelling outcome has been found in relation to the second aim and lies in the predictive value of the theta/beta ratio (TBr) on visitors’ well-being. Despite the exploratory nature of this analysis, the results indicate that resting-state EEG measurements can forecast the magnitude of anxiety change after the intervention. TBR was selected for its capability to indicate significant shifts in emotional/cognitive spheres through cortical-subcortical interactions [

30]. In fact, a modulation of TBr has been found in several mental processes where these two aspects strongly interact, including motivation, decision-making, and inhibitory control [

31]. This finding, therefore, puts the results in line with previous literature that had already discussed the importance of cognition and emotion in processes related to aesthetic experience [

11,

12,

16]. However, it complements it by suggesting a new marker that can easily be used in future studies for tracking well-being. Besides TBr, perceived stress and trait anxiety proved to predict the outcome of the intervention. This last result is very valuable as it suggests that there is much room for developing future interventions that can take into account individual differences and potential benefits, including discriminating between different intervention types.

An apparently incongruent result is the disassociation between trait anxiety and perceived stress in predicting state anxiety change. In fact, greater changes in state anxiety were predicted by lower perceived stress and higher trait anxiety. Although the two constructions are surely related, there are some differences that could explain these different directions. Trait anxiety, while representing a stable predisposition, may enhance the individual's sensitivity to situational changes. For example, Schwerdtfeger et al. [

48] reported that a brief “best possible selves” intervention before a stress task elicited adaptive physiological responses in high trait-anxious individuals. Thus, individuals with higher trait anxiety may experience greater relief when exposed to restorative, positive experiences. In contrast, perceived stress often reflects lifestyle and a more chronic, generalized overload and lack of control, which may counteract responsiveness to short-term interventions. In a study by Pizzagalli and colleagues [

49], stress scores, as measured precisely with the PSS, predicted reduced hedonic capacity even after controlling for general distress and anxiety symptoms. These results are in line with subclinical data showing an association between stress and anhedonia, as well as stress and depression. Future studies should better explore the differential effects of museum interventions on anxiety and depression symptoms.

5. Conclusions

This study is part of a larger research activity, the ASBA project [

17], which aims to validate museums as privileged places for self-care and to collect and share data and methodologies that can be used in a variety of contexts. So, on the one hand, it aims to put the museum at the center of community life, thus creating a socio-cognitive space to live enriching experiences. On the other hand, it wants to harness the inherent power of art and culture on the human mind as well as on relative health.

The results of the study show how museums activities can actually be effective in promoting well-being. Not only was the intervention effective in reducing state anxiety, but it was also compatible with normal museum activities and highly appreciated by participants and instructors. This reinforces the idea that neuroscience and brain technology are not destined to remain within research laboratories but will increasingly become part of everyday life [

50,

51], performing a variety of functions. Future research may also include artificial intelligence-based learning models that maximize the BCI device's ability to detect even small variations in a single person or group. It is therefore necessary to carry out more and more real-world studies to validate these neuroscientific applications, both in terms of effectiveness (e.g., measurement of state anxiety) and in terms of usability and robustness (e.g., bluetooth signal stability and signal-to-noise ratio).

Furthermore, it was possible to identify early in the intervention a neural marker that could potentially signal the amount of benefit that one can obtain, paving the way to a huge variety of future tailored interventions. Finally, the present study has shown how not only art museums can be considered ideal places to promote individual well-being, as other studies did [

2,

52], but also that science museums can pursue the same purpose as suggested by a limited number of previous studies (e.g., French et al., [

53]).

This study is not without limitations. First, it was not possible to use EEG measurement on all participants, who now reach over 400. Due to organizational and resource issues, but also personal availability (many participants were elderly and not particularly ready for brain technology; many others were distrustful), only a small sub-sample of 35 participants successfully participated in EEG recording. Hence the exploratory nature of the present study. However, given the promising results, the study will be continued with the hope of obtaining a much larger sample in a relatively short time. Moreover, the group-based nature of the activities and the reliance on self-report measures may constrain the generalizability of our findings. Nevertheless, we provided initial evidence that the protocol can be successfully adapted and implemented across different museum contexts. This flexibility suggests that museums in the future could integrate such interventions into their regular programming, offering accessible tools to enhance visitors' well-being and foster deeper engagement.

To conclude, we therefore believe that this study is of particular importance in bringing applied neuroscience closer to contexts such as museums, where it could play a key role in improving well-being. Also, its importance also lies in contributing to knowledge about the emotional and cognitive processes underlying aesthetic experience in general.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and C.L.; Methodology, C.L., M.E.V.; Software, R.F., C.L.; Formal Analysis, C.L., M.C.; Investigation, C.L., M.E.V.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.E.V., C.L.; Writing – Review & Editing, C.L., M.E.V., A.B., R.F., M.C.; Supervision, C.L.; Project Administration, C.L., M.E.V.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Philosophy “Piero Martinetti” of the University of Milan under the Project “Departments of Excellence 2023-2027” awarded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR).

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all the research participants for their enthusiastic and insightful contribution, and to the instructors for their valuable and professional involvement in the implementation of the intervention. In particular, we thank Galleria d’Arte Moderna and Museo di Storia Naturale (Milan. Italy), for their contribution to the study.

Conflicts of Interest

No authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Harrison, N.R.; Clark, D.P.A. The Observing Facet of Trait Mindfulness Predicts Frequency of Aesthetic Experiences Evoked by the Arts. Mindfulness (N. Y). 2016, 7, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastandrea, S.; Fagioli, S.; Biasi, V. Art and Psychological Well-Being: Linking the Brain to the Aesthetic Emotion. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckey, J. The Therapeutic Effectiveness of Creative Activities on Mental Well-being: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchiari, C.; Vanutelli, M.E.; Ferrara, V.; Folgieri, R.; Banzi, A. Promoting Well-Being in the Museum: The ASBA Project Research Protocol. Int. J. Heal. Wellness, Soc. 2024, 14, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastandrea, S.; Maricchiolo, F.; Carrus, G.; Giovannelli, I.; Giuliani, V.; Berardi, D. Visits to Figurative Art Museums May Lower Blood Pressure and Stress. Arts Health 2019, 11, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, H.L.; Nobel, J. The Connection between Art, Healing, and Public Health: A Review of Current Literature. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, H.J.; Noble, G. Museums, Health and Well-Being; Routledge: New York, 2016; ISBN 1317092716. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, L.J.; Lockyer, B.; Camic, P.M.; Chatterjee, H.J. Effects of a Museum-Based Social Prescription Intervention on Quantitative Measures of Psychological Wellbeing in Older Adults. Perspect. Public Health 2018, 138, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ander, E.E.; Thomson, L.J.M.; Blair, K.; Noble, G.; Menon, U.; Lanceley, A.; Chatterjee, H.J. Using Museum Objects to Improve Wellbeing in Mental Health Service Users and Neurological Rehabilitation Clients. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 76, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camic, P.M.; Chatterjee, H.J. Museums and Art Galleries as Partners for Public Health Interventions. Perspect. Public Health 2013, 133, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.-J.; Chu, H.; Chang, H.-J.; Chung, M.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Chiou, H.-Y.; Chou, K.-R. The Effects of Reminiscence Therapy on Psychological Well-Being, Depression, and Loneliness among the Institutionalized Aged. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eekelaar, C.; Camic, P.M.; Springham, N. Art Galleries, Episodic Memory and Verbal Fluency in Dementia: An Exploratory Study. Psychol. Aesthetics, Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolwerk, A.; Mack-Andrick, J.; Lang, F.R.; Dörfler, A.; Maihöfner, C. How Art Changes Your Brain: Differential Effects of Visual Art Production and Cognitive Art Evaluation on Functional Brain Connectivity. PLoS One 2014, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, H.; Zeki, S. Neural Correlates of Beauty. J. Neurophysiol. 2004, 91, 1699–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, S.; Hagtvedt, H.; Patrick, V.M.; Anderson, A.; Stilla, R.; Deshpande, G.; Hu, X.; Sato, J.R.; Reddy, S.; Sathian, K. Art for Reward’s Sake: Visual Art Recruits the Ventral Striatum. Neuroimage 2011, 55, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, M.; Munar, E.; Angel Capo, M.; Rossello, J.; Cela-Conde, C.J. Towards a Framework for the Study of the Neural Correlates of Aesthetic Preference. Spat. Vis. 2008, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Banzi, A. The Brain-Friendly Museum: Using Psychology and Neuroscience to Improve the Visitor Experience; Taylor & Francis: New York, 2022; ISBN 1000684164. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, H.J.; Camic, P.M. The Health and Well-Being Potential of Museums and Art Galleries. Arts Heal. 2015, 7, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, L.J.; Chatterjee, H.J. Measuring the Impact of Museum Activities on Well-Being: Developing the Museum Well-Being Measures Toolkit. Museum Manag. Curatorsh. 2015, 30, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Casanova, J.M.; Guzman-Parra, J.; Duran-Jimenez, F.J.; Garcia-Gallardo, M.; Cuesta-Lozano, D.; Mayoral-Cleries, F. Effectiveness of Museum-Based Participatory Arts in Mental Health Recovery. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 1416–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, C.; Camic, P.M.; Lockyer, B.; Thomson, L.J.M.; Chatterjee, H.J. Museum-Based Programs for Socially Isolated Older Adults: Understanding What Works. Health Place 2017, 48, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnie, J. Does Viewing Art in the Museum Reduce Anxiety and Improve Wellbeing? Museums Soc. Issues 2010, 5, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Mairesse, F. The Definition of the Museum through Its Social Role. Curator Museum J. 2018, 61, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Bardwell, L. V; Slakter, D.B. The Museum as a Restorative Environment. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konlaan, B.B.; Bygren, L.O.; Johansson, S.-E. Visiting the Cinema, Concerts, Museums or Art Exhibitions as Determinant of Survival: A Swedish Fourteen-Year Cohort Follow-Up. Scand. J. Public Health 2000, 28, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackoi, K.; Patsou, M.; Chatterjee, H.J. Museums for Health and Wellbeing: A Preliminary Report, National Alliance for Museums, Health and Wellbeing.; museumsandwellbeingalliance.wordpress.com: Retrieved from, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney, K.; Kavanagh, J. Museum Participation: New Directions for Audience Collaboration; Museums etc.: Edinburgh, 2016; ISBN 1910144789. [Google Scholar]

- Gerger, G.; Leder, H. Titles Change the Esthetic Appreciations of Paintings. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, P.; Verkuil, B.; Arias-Garcia, E.; Pantazi, I.; van Schie, C. EEG Theta/Beta Ratio as a Potential Biomarker for Attentional Control and Resilience against Deleterious Effects of Stress on Attention. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 14, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidis, A.; van der Does, W.; Schakel, L.; Putman, P. Frontal EEG Theta/Beta Ratio as an Electrophysiological Marker for Attentional Control and Its Test-Retest Reliability. Biol. Psychol. 2016, 121, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillas-Romero, A.; Tortella-Feliu, M.; Bornas, X.; Putman, P. Spontaneous EEG Theta/Beta Ratio and Delta–Beta Coupling in Relation to Attentional Network Functioning and Self-Reported Attentional Control. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 15, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, P.; van Peer, J.; Maimari, I.; van der Werff, S. EEG Theta/Beta Ratio in Relation to Fear-Modulated Response-Inhibition, Attentional Control, and Affective Traits. Biol. Psychol. 2010, 83, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultanov, M.; İsmailova, K. EEG Rhythms in Prefrontal Cortex as Predictors of Anxiety among Youth Soccer Players. Transl. Sport. Med. 2019, 2, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Garza, J.G.; Brantley, J.A.; Nakagome, S.; Kontson, K.; Megjhani, M.; Robleto, D.; Contreras-Vidal, J.L. Deployment of Mobile EEG Technology in an Art Museum Setting: Evaluation of Signal Quality and Usability. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, Y.; Hassib, M.; Marquez, M.G.; Funk, M.; Schmidt, A. Implicit Engagement Detection for Interactive Museums Using Brain-Computer Interfaces. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services Adjunct; 2015; pp. 838–845.

- Cuypers, K.; Krokstad, S.; Holmen, T.L.; Knudtsen, M.S.; Bygren, L.O.; Holmen, J. Patterns of Receptive and Creative Cultural Activities and Their Association with Perceived Health, Anxiety, Depression and Satisfaction with Life among Adults: The HUNT Study, Norway. J Epidemiol Community Heal. 2012, 66, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberg, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. STAI Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologist Press: Palo Alto, CA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Diego, M.; Delgado, J.; Medina, L. Yoga and Social Support Reduce Prenatal Depression, Anxiety and Cortisol. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2013, 17, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, G.J.; Neill, J.T. The Effect of “Green Exercise” on State Anxiety and the Role of Exercise Duration, Intensity, and Greenness: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasari, P.; Wahab, M.N.A.; Herawan, T.; Othman, A.; Sinnadurai, S.K. Re-Test of State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) among Engineering Students in Malaysia: Reliability and Validity Tests. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 3843–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanutelli, M.E.; Grigis, C.; Lucchiari, C. Breathing Right… or Left! The Effects of Unilateral Nostril Breathing on Psychological and Cognitive Wellbeing: A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.J.; Wolpaw, J.R. Brain-Computer Interfaces for Communication and Control. Commun. ACM 2011, 54, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flesher, S.; Downey, J.; Collinger, J.; Foldes, S.; Weiss, J.; Tyler-Kabara, E.; Bensmaia, S.; Schwartz, A.; Boninger, M.; Gaunt, R. Intracortical Microstimulation as a Feedback Source for Brain-Computer Interface Users. Brain-Computer Interface Res. A State-of-the-Art Summ. 6 2017, 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Bockbrader, M. Upper Limb Sensorimotor Restoration through Brain–Computer Interface Technology in Tetraparesis. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 11, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.H.; Pritchard-Berman, M.; Sosa, N.; Ceja, A.; Kesler, S.R. Task-Based Neurofeedback Training: A Novel Approach toward Training Executive Functions. Neuroimage 2016, 134, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimenko, V.; Lüttjohann, A.; van Heukelum, S.; Kelderhuis, J.; Makarov, V.; Hramov, A.; Koronovskii, A.; van Luijtelaar, G. Brain-Computer Interface for the Epileptic Seizures Prediction and Prevention. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Winter Conference on Brain-Computer Interface (BCI); IEEE, 2020; pp. 1–5.

- Schwerdtfeger, A.R.; Rominger, C.; Weber, B.; Aluani, I. A Brief Positive Psychological Intervention Prior to a Potentially Stressful Task Facilitates More Challenge-like Cardiovascular Reactivity in High Trait Anxious Individuals. Psychophysiology 2021, 58, e13709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzagalli, D.A.; Bogdan, R.; Ratner, K.G.; Jahn, A.L. Increased Perceived Stress Is Associated with Blunted Hedonic Capacity: Potential Implications for Depression Research. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 2742–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanutelli, M.E.; Lucchiari, C. “Hyperfeedback” as a Tool to Assess and Induce Interpersonal Synchrony: The Role of Applied Social Neurosciences for Research, Training, and Clinical Practice. J. Heal. Med. Sci. 2022, 5, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanutelli, M.E.; Salvadore, M.; Lucchiari, C. BCI Applications to Creativity: Review and Future Directions, from Little-c to C2. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šveb Dragija, M.; Jelinčić, D.A. Can Museums Help Visitors Thrive? Review of Studies on Psychological Wellbeing in Museums. Behav. Sci. (Basel). 2022, 12, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.; Lunt, N.; Pearson, M. The MindLab Project. Local Museums Supporting Community Wellbeing before and after Uk Lockdown. Museum Soc. 2020, 18, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).