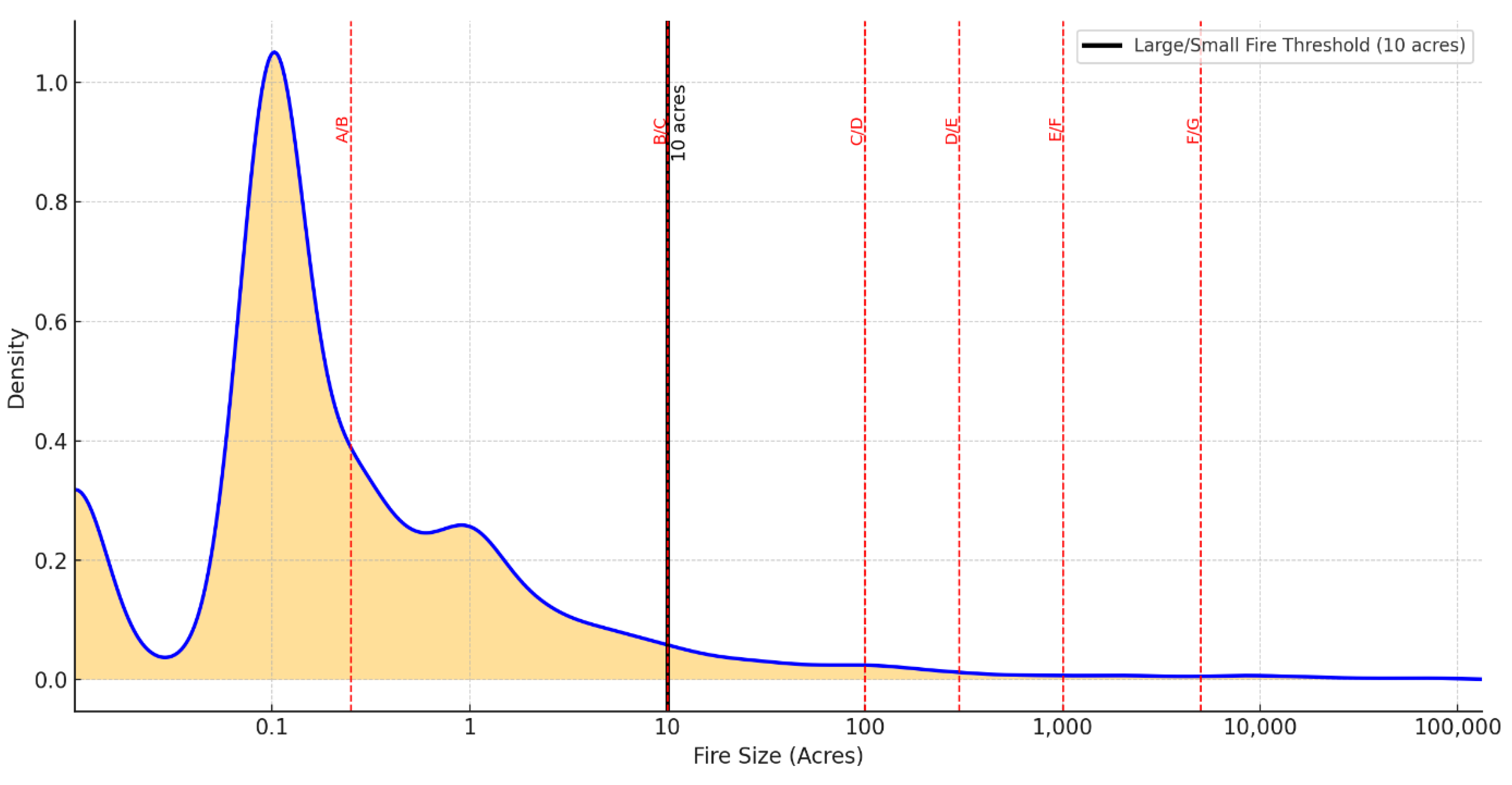

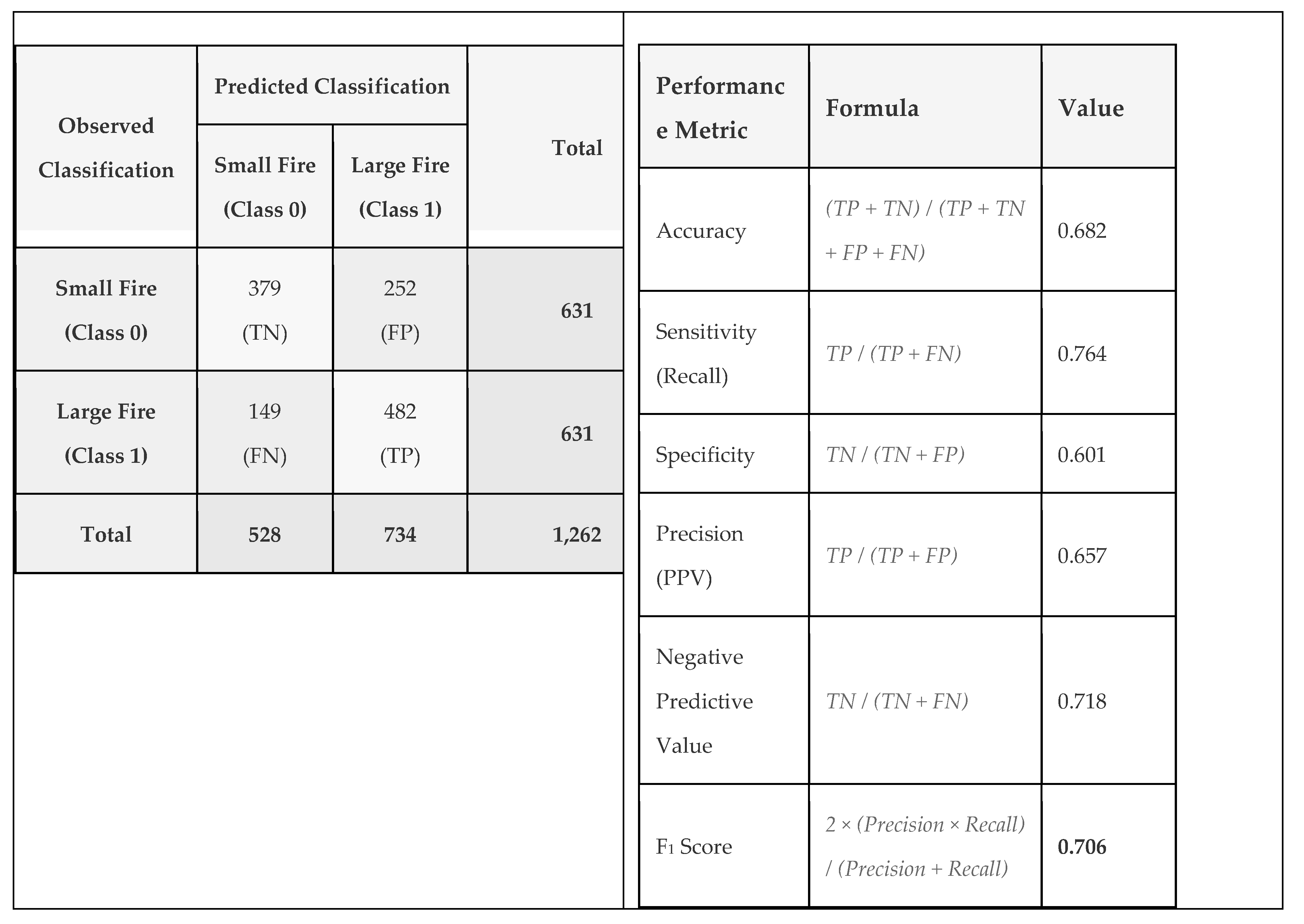

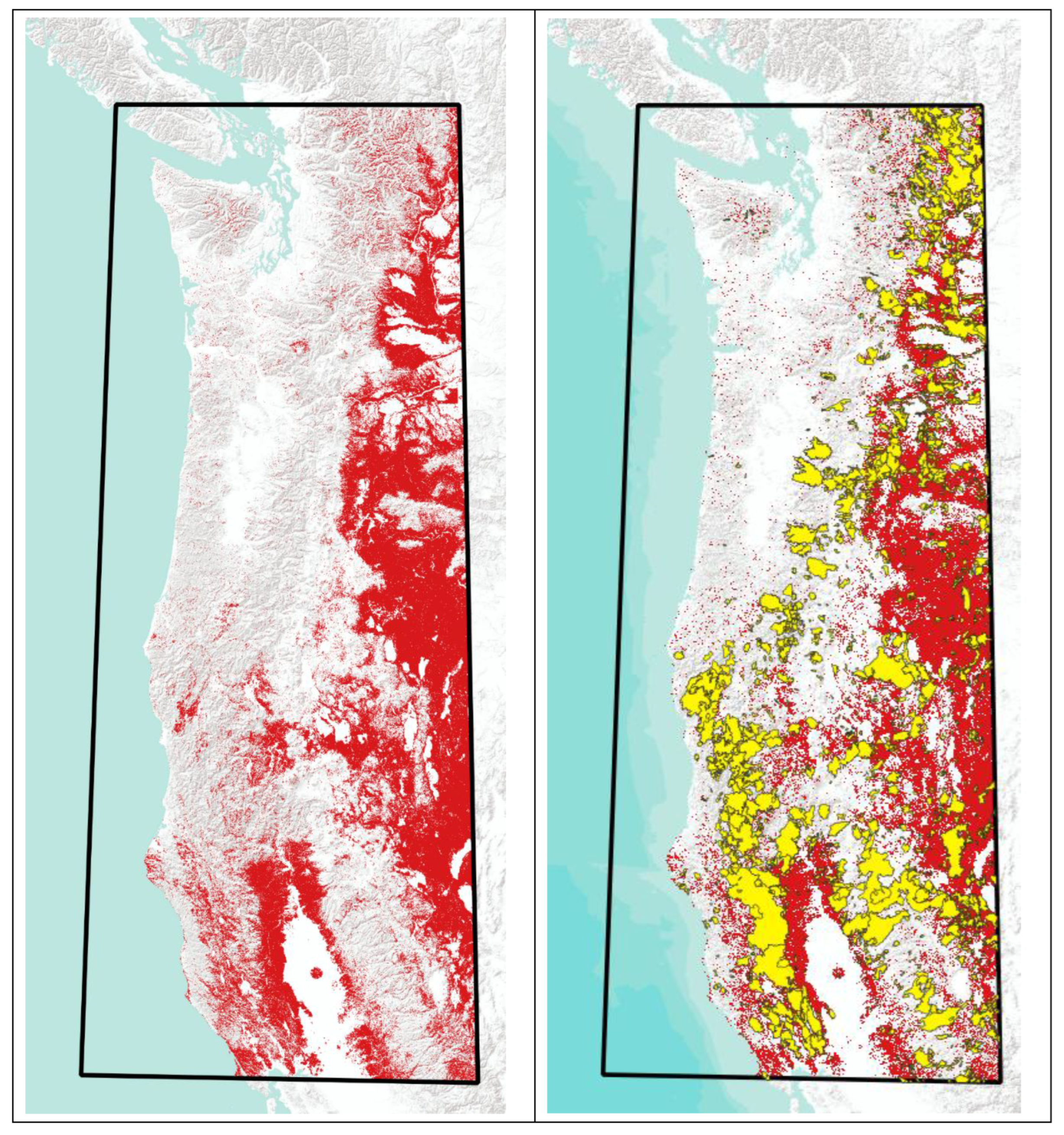

Figure 3.

Wildfires from 2015 -2020 symbolized by size with classes A & B shown as small yellow points, while large fires (C, D, E, F, &G) are large yellow circles with red outlines.

As noted earlier, the primary novelty of this work lies in the application of information-theoretic modeling to wildfire size prediction using historical data, not in discovering previously unknown fire causes. Reconstructability Analysis offers several advantages for this domain: (1) it naturally accommodates categorical data without transformation, (2) it produces highly interpretable models with explicit variable relationships, and (3) it quantifies information content and uncertainty (Shannon entropy) reduction in a statistically rigorous framework. These methodological strengths complement existing process-based and empirical wildfire models while offering a transparent alternative to ‘black box’ machine learning approaches.

2.1. GIS Data Preparation and Multi-Scale Spatial Processing

The geospatial analysis framework developed for this study required coordination of multi-temporal raster datasets with point-based ignition records across varied spatial and temporal scales. We designed and implemented a multi-scale spatial neighborhood analysis centered on wildfire ignition points from the 2015 to 2020 fire seasons, extracted from the Fire Program Analysis Fire Occurrence Database (FPA FOD). These points were used as the center of the raster extraction kernel that processed the data from the entire yearly stack of NLCD data (1985 to 2020), using a temporal kernel that samples every five years. All geospatial processing utilized the Albers Equal Area Conic projection (EPSG:5070) with North American Datum 1983 (NAD83) to ensure consistent coordinates across the western United States study region.

The cornerstone of our GIS methodology was the development of a hierarchical concentric ring buffer algorithm (

Figure 4) that extracts land cover information at three distinct spatial scales around each ignition point. By “rings” at different spatial scales we mean nested squares of GIS raster data. This approach builds on our previous work applying information-theoretic neighborhood analysis to NLCD data (Percy and Zwick, 2024) but extends it to a multi-ring design centered on ignition points:

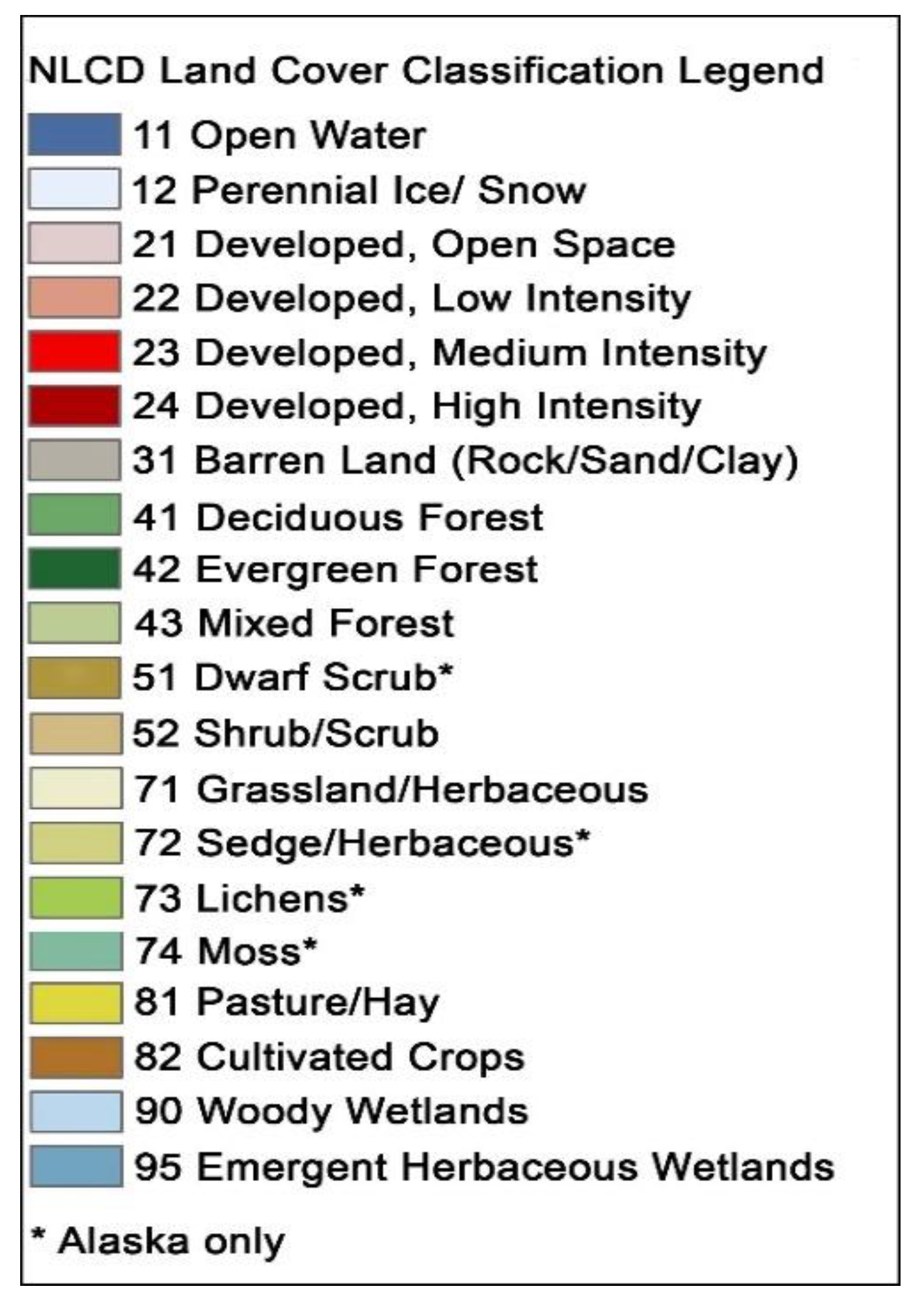

Figure 4.

- NLCD data overlaid with raster extraction “rings”. Colors correspond to standard NLCD legend of

Figure 2. Large red dot represents the fire currently being processed. Cells are 30m, so the inner ring is 30 – 60m, middle ring is 90 – 120m, and outer is 150 – 180m.

Figure 4.

- NLCD data overlaid with raster extraction “rings”. Colors correspond to standard NLCD legend of

Figure 2. Large red dot represents the fire currently being processed. Cells are 30m, so the inner ring is 30 – 60m, middle ring is 90 – 120m, and outer is 150 – 180m.

Inner Ring: 3×3 and 5×5 pixel neighborhoods (30 – 60m), capturing immediate fuel conditions at the ignition site (Finney et al., 2005)

Middle Ring: 7×7 and 9×9 pixel neighborhoods (90 – 120m), representing the zone where initial fire establishment typically occurs (Balch et al., 2013)

Outer Ring: 11×11 and 13×13 pixel neighborhoods (150 – 180m), encompassing potential ember spotting distances and broader landscape context (Dillon et al., 2011; Westerling, 2016)

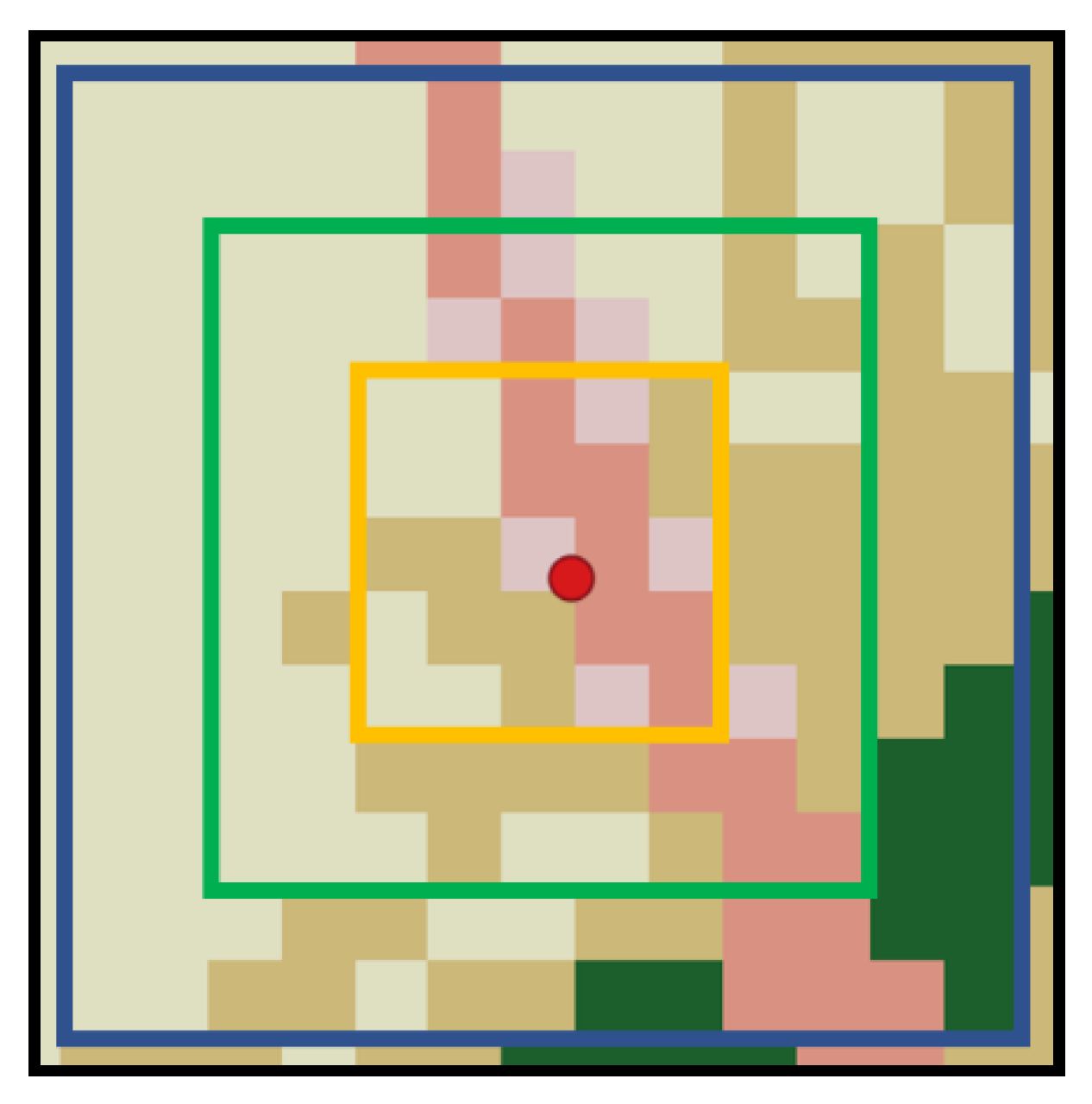

Within each ring, we identified both dominant and subdominant land cover classes based on raster cell frequency from seven NLCD land cover rasters at seven different times (T, T - 5, T - 10, T - 15, T - 20, T - 25, & T - 30), enabling us to capture both contemporary vegetation conditions and long-term landscape legacy effects (Bradley

et al., 2018).

Figure 5 illustrates the raster stack. The implementation for extracting a record of data for each fire is to encode the most common NLCD class for each ring in the current layer T (layer 0), and then do the same in five-year increments going back 30 years. Computing the most common (dominant) NLCD class will never result in a tie, since all of the rings have uneven numbers of cells (25 for the inner ring, 81 for the middle, and 169 for the outer). The second-most common class is called the sub-dominant, and in the case where the entire ring is occupied by all the same NLCD class we populate the sub-dominant field with the same dominant value to avoid holes in the database.

Figure 5.

Sample stack of National Landcover data from 1985 to 2015. Time 0 is the year of the fire being extracted; numbers associated with other times (years) are lags. For example, a fire from 2017 gets 3 ring data from years 2017 (T), 2012 (T-5), 2007 (T-10), 2002 (T-15), 1997 (T-20), 1992 (T-25), & 1987 (T-30).

Figure 5.

Sample stack of National Landcover data from 1985 to 2015. Time 0 is the year of the fire being extracted; numbers associated with other times (years) are lags. For example, a fire from 2017 gets 3 ring data from years 2017 (T), 2012 (T-5), 2007 (T-10), 2002 (T-15), 1997 (T-20), 1992 (T-25), & 1987 (T-30).

Multi-temporal Raster Processing and Standardization As seen in

Figure 5, yearly NLCD land cover rasters (1985 through 2020) were acquired from the USGS MRLC site. After organizing into a local database, they were clipped to the study area and reprojected to the CRS used for the project (Albers Equal Area). At this point they were ready to be extracted. Extraction with our custom kernel produces a set of independent variables (IVs) that are in this form:

[Center_X, Center_X, Fire_ID, In_0_Dom, In_0_Sub, Mid_0_Dom, Mid_0_Sub, Out_0_dom, Out_0_sub, In_1_dom, In_1,_sub, Mid_1_dom, Mid_1_sub, Out_1_dom, Out_1_sub, etc,…Out_6_sub]

A total of 42 extracted NLCD codes for each fire were then joined to other data such as elevation and fires size based on the shared Fire_ID.

Table 1 shows a complete listing of the variables extracted using the multi-ring extractor.

Table 1.

Extracted variables (IVs for our model) from the multi-ring extraction algorithm. Each fire from 2015 to 2020 had its location plotted on a continuous stack of NLCD data from 1985 to 2020, which was then sampled every five years for a total of 7 layers of data per fire. Within each layer, the inner, middle, and outer rings were sampled as shown in

Figure 4, resulting in 42 NLCD codes per fire ignition.

Table 1.

Extracted variables (IVs for our model) from the multi-ring extraction algorithm. Each fire from 2015 to 2020 had its location plotted on a continuous stack of NLCD data from 1985 to 2020, which was then sampled every five years for a total of 7 layers of data per fire. Within each layer, the inner, middle, and outer rings were sampled as shown in

Figure 4, resulting in 42 NLCD codes per fire ignition.

| Time layer |

Inner Ring Dominant & SubDominant |

Middle Ring Dominant & SubDominant |

Outer Ring Dominant & SubDominant |

| T- 0 (time of ignition) |

In_0_Dom, In_0_Sub |

Mid_0_Dom, Mid_0_Sub |

Out_0_Dom, Out_0_Sub |

| T – 1 (5 year lag) |

In_1_Dom, In_1_Sub |

Mid_1_Dom, Mid_1_Sub |

Out_1_Dom, Out_1_Sub |

| T – 2 (10 year lag |

In_2_Dom, In_2_Sub |

Mid_2_Dom, Mid_2_Sub |

Out_2_Dom, Out_2_Sub |

| T – 3 (15 year lag) |

In_3_Dom, In_3_Sub |

Mid_3_Dom, Mid_3_Sub |

Out_3_Dom, Out_3_Sub |

| T – 4 (20 year lag) |

In_4_Dom, In_4_Sub |

Mid_4_Dom, Mid_4_Sub |

Out_4_Dom, Out_4_Sub |

| T – 5 (25 year lag) |

In_5_Dom, In_5_Sub |

Mid_5_Dom, Mid_5_Sub |

Out_5_Dom, Out_5_Sub |

| T – 6 (30 year lag) |

In_6_Dom, In_6_Sub |

Mid_6_Dom, Mid_6_Sub |

Out_6_Dom, Out_6_Sub |

Elevation, Ignition Cause, and Season Variables

In addition to the 42 ring extracted independent variables shown in

Table 1 (two IVs for each cell in columns 2-4), elevation, ignition cause, and season were also used as IVs, Elevation values for fire ignition points were obtained from the FOD FPA. Elevation bins were subsequently defined based on these values to support categorical modeling within the Occam framework. The bins were chosen to maximize the maximize the information gain relative to predicting our target variable, and are [0-1500, 1500-2000, 2000-2500, 2500-3500, > 3500 meters]. Season was derived from the date of fire ignition, binned into Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall. Unsurprisingly, the majority of large fires occur in the Summer. Ignition Cause was also added as an IV to the database from the FOD FPA, based on the NWCG general cause classifications.

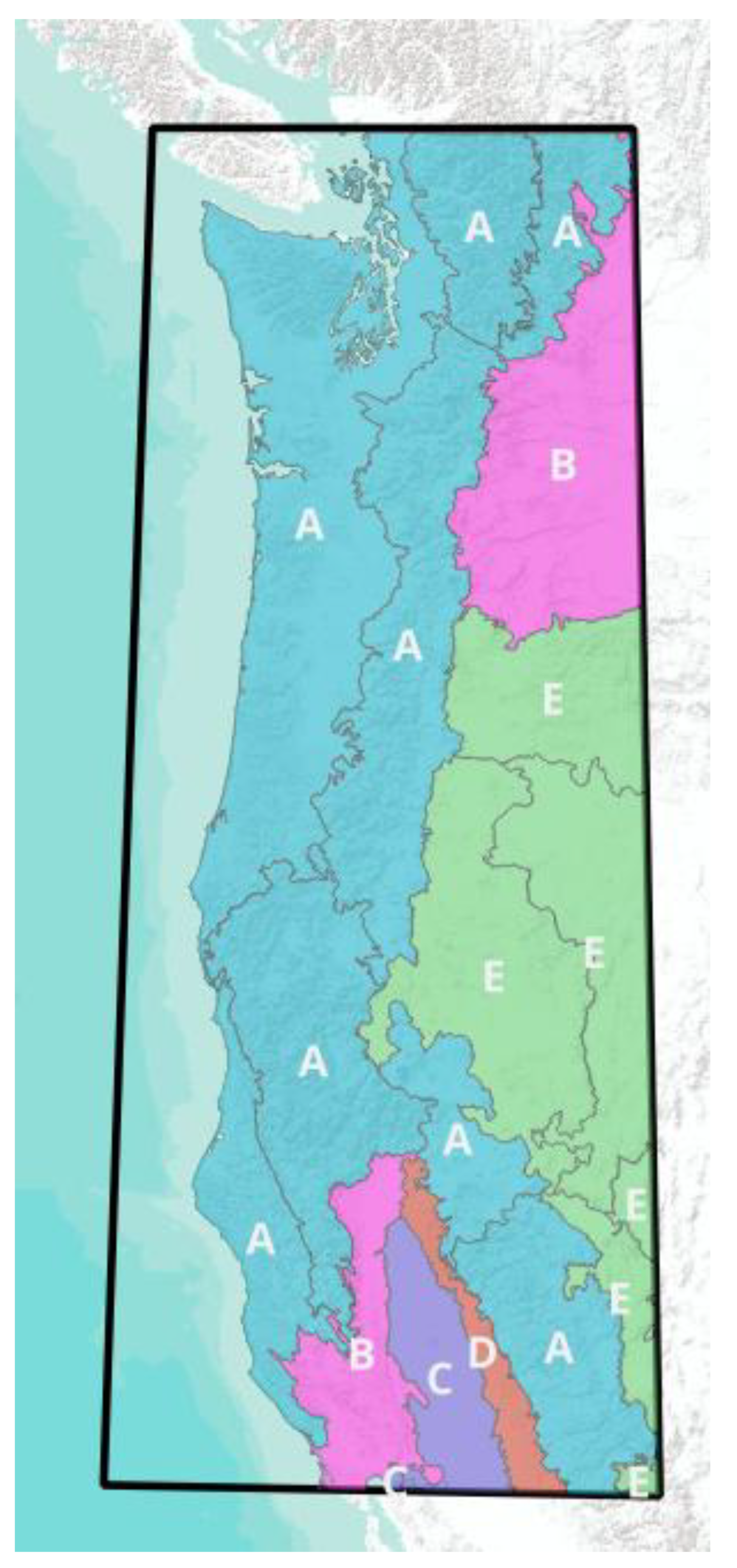

2.3. Pyrome Grouping

The study area consists of 19 different ecoregions that are known as pyromes in the fire science literature. This high cardinality (number of classes) is difficult to work with in information theoretic modelling, and needs to be grouped meaningfully. We employed a clustering technique on the pyromes by using the signatures from the 21-variable string of dominant NLCD codes. First, we binned the 15 NLCD classes down to 7 vegetation types, plus one class for all of the other developed, water, and barren codes, resulting in an 8-class model. Then, each of the 19 pyromes had a representative signature generated by calculating the mode (most frequent value) of each of the 21 binned NLCD values. These 19 signatures were then evaluated using a Hamming distance space (a sequence comparison algorithm), and clustered based on similarities. The silhouette plots showed that a five-cluster result was optimal, so the

pyromes were clustered into 5 groups as shown in

Figure 7. Other groupings were attempted based on available ecosystem characteristics, such as precipitation, and predominant vegetation. Good reduction of uncertainty results were obtained from several other of these pyrome groupings, suggesting that the “signal” from the data with regard to predicting large fires is robust. The final choice to use this particular signature grouping mechanism, based on clustering, was due to the overall goodness of the reduction of uncertainty, %dH. As mentioned in section 2.2, we sampled the small fires to create a set that matches the number of large fires to balance the data for each pyrome group, so that each pyrome has an equal number of small and large fires.

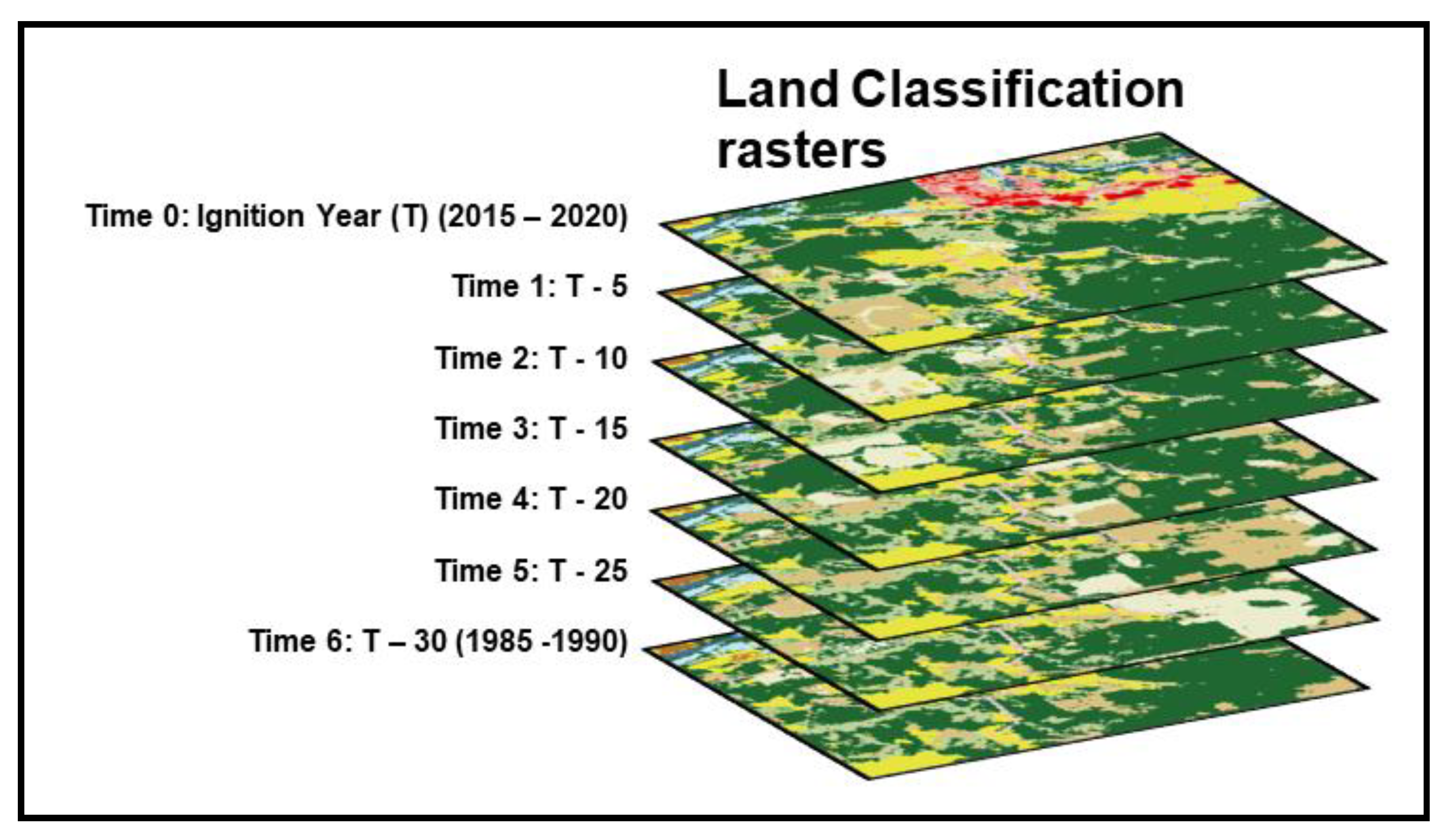

Figure 6.

– Kernel Density illustration of fire size distribution. The bold line at 10 on the logarithmic X axis is the cutoff for small vs large fires in this study.

Figure 6.

– Kernel Density illustration of fire size distribution. The bold line at 10 on the logarithmic X axis is the cutoff for small vs large fires in this study.

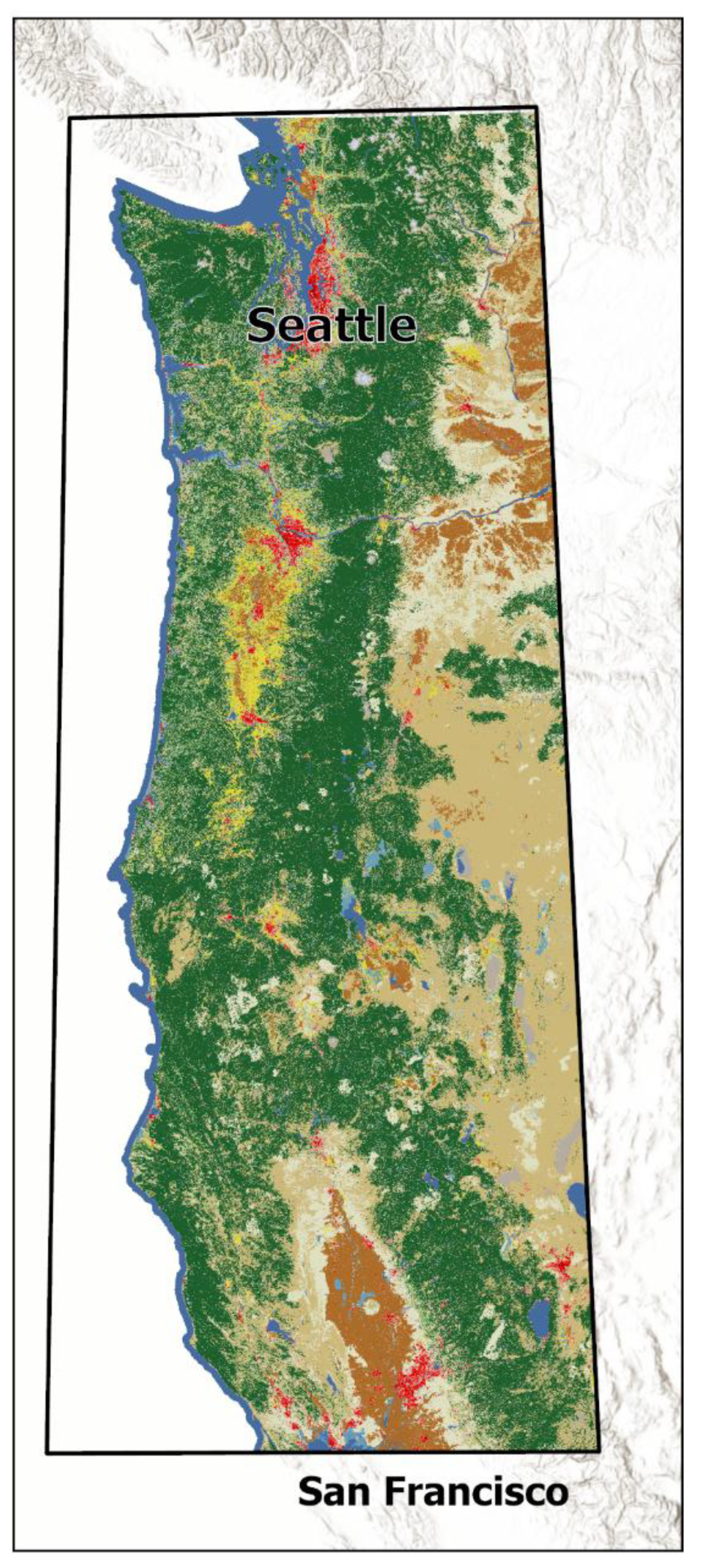

Figure 7.

Pyrome Groups: pyrome outlines are shown in gray, five signature groups are designated by color and labeled by letter. Pyrome signatures are generated by calculating the most common set of attribute values for each pyrome, and then clustering is based on these signatures.

Figure 7.

Pyrome Groups: pyrome outlines are shown in gray, five signature groups are designated by color and labeled by letter. Pyrome signatures are generated by calculating the most common set of attribute values for each pyrome, and then clustering is based on these signatures.

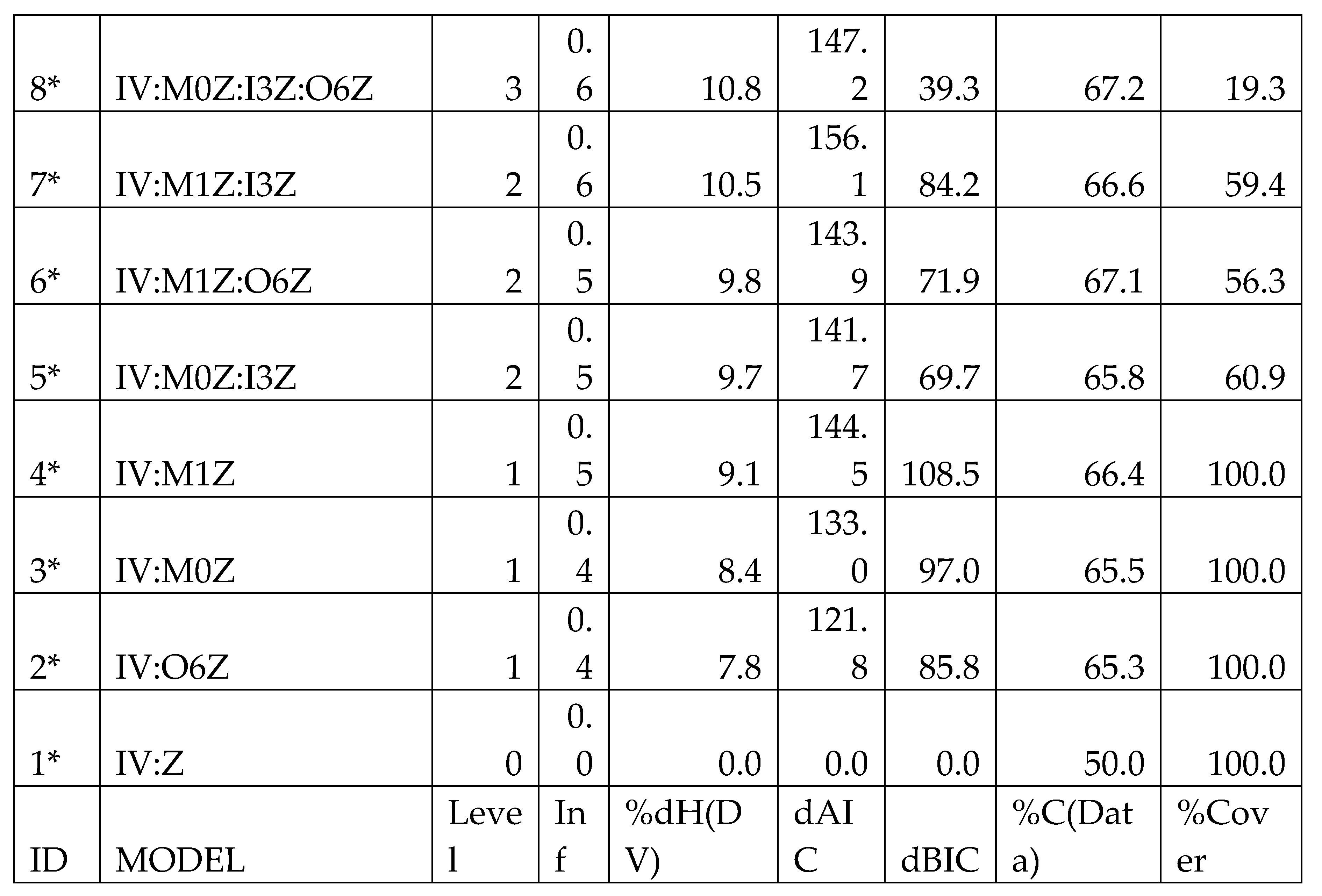

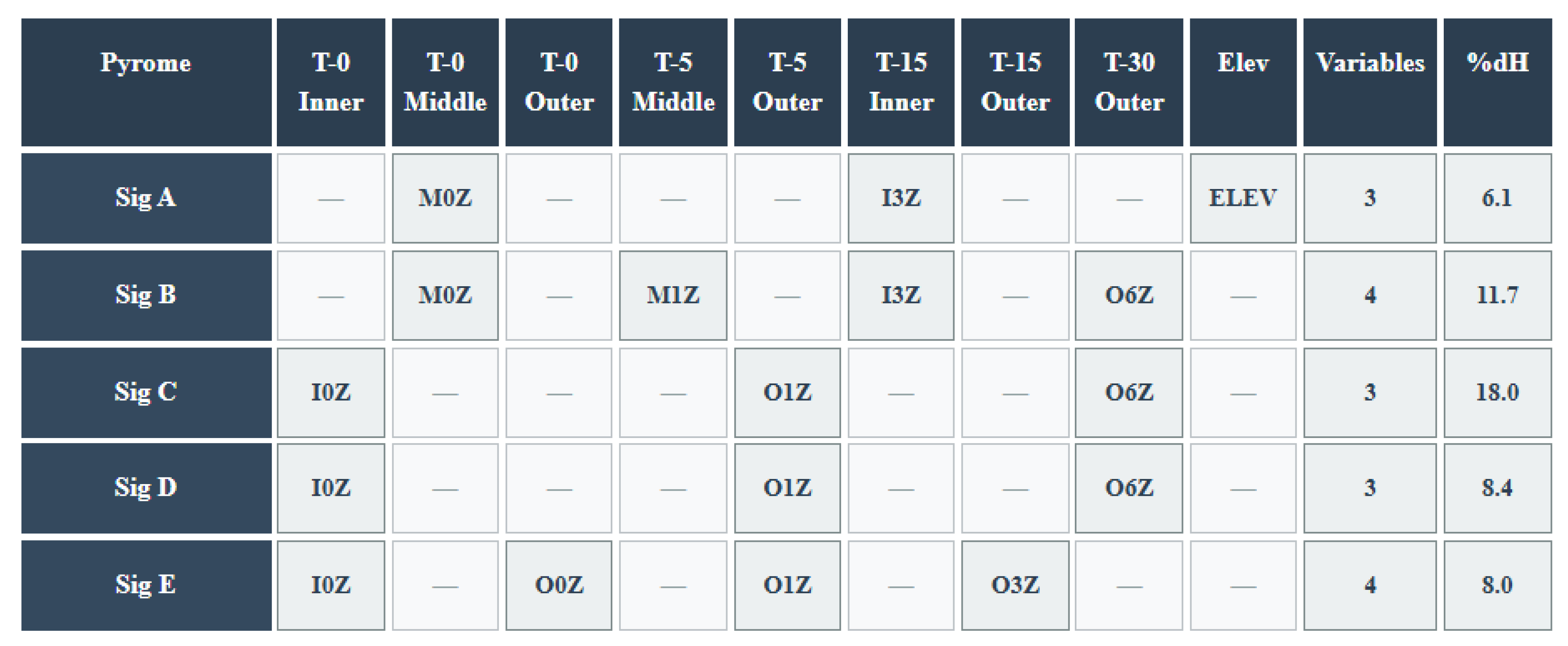

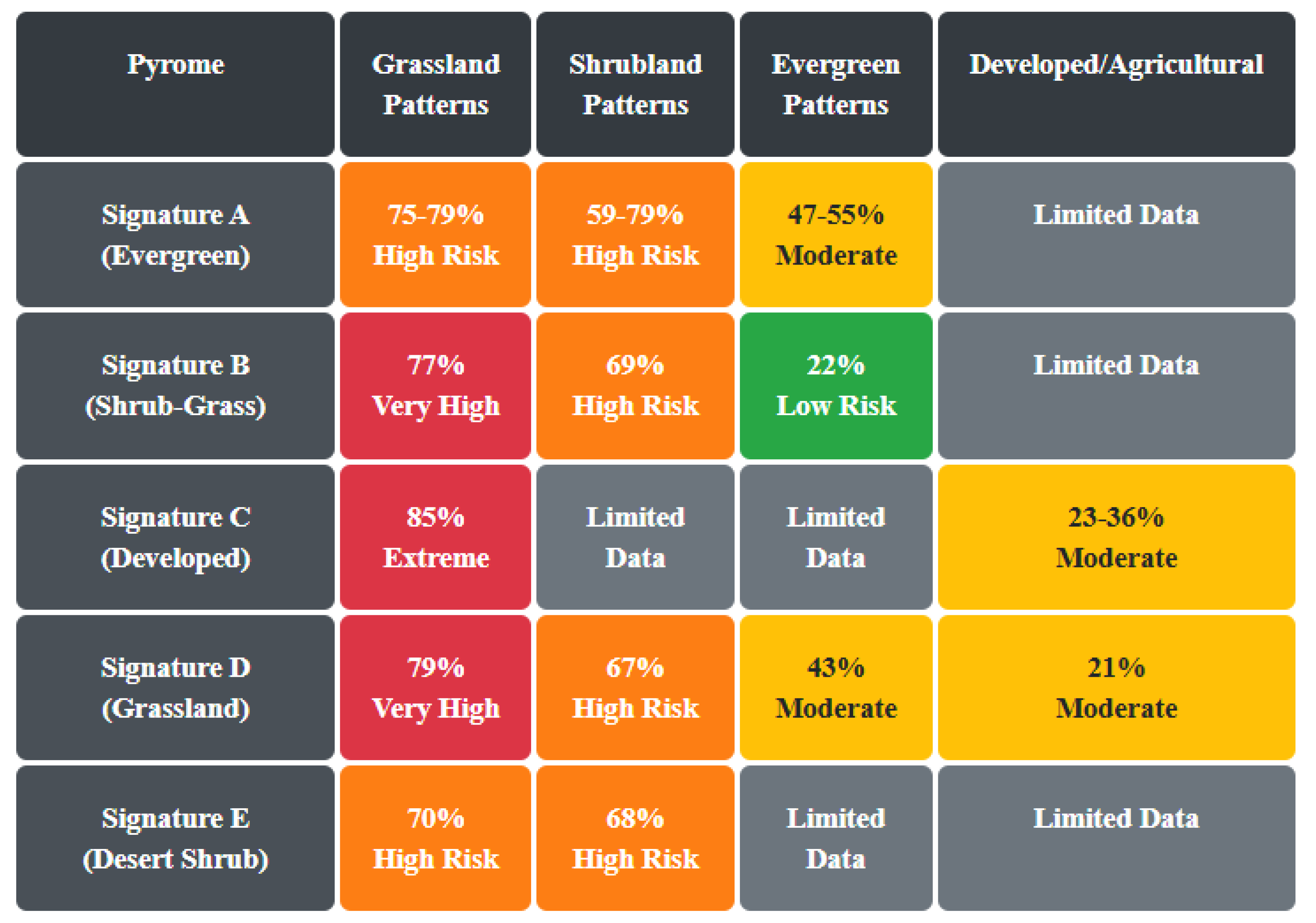

Table 3.

Pyrome characteristics of the final grouping of 19 initial pyromes. Grouping is based on the characteristic signature for each pyrome, which is based on the most common IV attributes for the variables shown in

Table 1.

Table 3.

Pyrome characteristics of the final grouping of 19 initial pyromes. Grouping is based on the characteristic signature for each pyrome, which is based on the most common IV attributes for the variables shown in

Table 1.

2.4. Reconstructability Analysis Framework and Implementation

2.4.1. Fundamentals of Reconstructability Analysis

Reconstructability Analysis (RA) is introduced in this study to the wider GIS community as a technique for modeling categorical data that quantifies relationships between variables using information theory. While traditional statistical approaches often impose assumptions of linearity or normal distributions—assumptions frequently violated in environmental data—RA directly works with categorical variables (and/or continuous variables that have been discretized) to reveal structural patterns of dependency.

In the Variable-Based Reconstructability Analysis (VB-RA) approach employed in this study, models are represented as sets of relations between variables, where each relation captures a specific pattern of constraint in the data. These relationships are systematically organized in a lattice of structures, with the independence model at the bottom and the full data at the top. The Occam software (Zwick, 2004), developed at Portland State University, implements sophisticated algorithms to navigate this lattice efficiently, even for problems where this lattice is extremely large.

For those familiar with Bayesian Networks, RA shares the fundamental goal of using graph structures to model probabilistic relationships between categorical variables, but differs in several key aspects that make it particularly suitable for exploratory analysis (Zwick, 2004). While Bayesian Networks employ directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to represent causal relationships and support probabilistic inference, RA uses undirected hypergraphs that can contain loops, allowing it to capture higher-order interactions among multiple variables simultaneously without requiring prior assumptions about causal direction (Zwick, 2004). This structural flexibility enables RA to discover unexpected high-ordinality and nonlinear interactions through systematic exploratory modeling, whereas Bayesian Networks typically require prior knowledge of causal structure and focus on confirmatory inference tasks. The hypergraph representation in RA can model some independence structures that are impossible in Bayesian Networks due to the acyclicity constraint, making RA particularly valuable for revealing complex interdependencies in systems where causal relationships are unknown or multidirectional (Harris and Zwick, 2021).

RA is rooted in Shannon’s Information Theory (Shannon, 1948) and Ashby’s Constraint Analysis (Ashby, 1956), with contributions from Klir, Krippendorff, and others who added graphical modeling approaches (Klir, 1985; Krippendorff, 1986). The methodology calculates the amount of information “transmitted” between discrete variables, resulting in a quantification of their relationships. For our wildfire research, we employ a directed system approach, where models are assessed by how much their independent variables (IVs) reduce the Shannon entropy (uncertainty) of a dependent variable (DV)—in our case, fire size classification (small or large).

The mathematical foundation is straightforward: Let p(DV) be the observed probability distribution of fire size; let p

model(DV|IV) be the calculated model conditional probability distribution of fire size given the set of predicting IVs. Then:

and

These two values represent the Shannon entropy (uncertainty) of fire size in the data (first equation) and the Shannon entropy of fire size in the RA model of the data (second equation). The latter entropy represents a reduction in the former entropy, with the difference between the original and reduced entropy serving as our information theoretic measure of predictive efficacy. Dividing this entropy reduction by H(DV) gives the fractional entropy reduction, expressed as a percentage, which is reported in Occam. This measure is specific to RA and other probabilistic machine learning methods. It is supplemented in Occam with generic metrics of predictive efficacy such as %Correct which are applicable to all machine learning methods.

2.4.2. Loop Versus Loopless Models in RA

Let Z be the DV, and A, B, C … be the IVs. A critical distinction in RA is between loopless models and models with loops. In our directed system with multiple independent variables (IVs) predicting a single dependent variable (fire size class), a loopless model contains only a single predicting component for the DV. For example, a loopless model like IV:ABCZ has only one predicting component (ABCZ), indicating that variables A, B, and C jointly predict Z. The “IV” component in this model is shorthand for ABC…. Every directed systems model includes a component that is a relation of all the independent variables (not only the predicting IVs). This is to assure that the directed systems models are hierarchically nested, which is desirable for statistical comparisons.

In contrast, a model with loops like IV:AZ:BZ:CZ has multiple predicting components (AZ, BZ, CZ) separated by colons, suggesting that variables A, B, and C quasi-independently contribute to Z prediction. (These IVs predict Z more independently than they do in IV:ABCZ, but the maximum entropy nature of RA methodology generates a kind of interaction effect among these IVs; see the discussion of different types of epistasis in (Zwick, 2011).) This model contains loops because every variable occurs in more than one relation. Loopless models offer computational advantages: they can be calculated algebraically without iterative procedures, and they represent a smaller model search space. Models with loops employ Iterative Proportional Fitting (IPF) which is substantially more computationally intensive, and thus better to run on a smaller subset of variables.

In our initial data exploration, we used loopless searches for feature selection, systematically evaluating all 45 original variables (dominant and subdominant vegetation classes across three rings and seven time periods, plus elevation, season, & ignition cause) to identify the most predictive features. This preliminary screening eliminated subdominant vegetation variables, which showed consistently low information content, allowing us to focus on dominant vegetation patterns in our subsequent analysis with models containing loops. This reduced the number of NLCD variables from 42 to 21, and also eliminated ignition cause.

2.4.3. Model Structure and Representation

In Reconstructability Analysis, models are hypergraphs whose components are relations between variables. These models form a structured lattice with the independence model (bottom), IV:DV, having the DV not related to any of the IVs, and the saturated model (top) having all variables related. This lattice provides a formalized model search space for identifying models that optimally balance parsimony with explanatory power.

For our analysis of multiple variables predicting fire size (Z), model notation follows the format:

This model has five predictive components (relations), each involving one predicting IV, whose name is a string of letters that begins with a capital letter, and Z, the predicted DV. This notation indicates that the inner ring vegetation from T0 (I0), middle ring vegetation from T-15 (M3), outer ring vegetation from T- 30 (O6), month group (Monthgrp), and elevation (Elev) each independently predict fire size (Z). The first component (IV) represents all independent variables in their joint distribution, while each subsequent component following the colon represents a specific predictive relationship.

The search process navigates the lattice of structures from the independence model (IV:Z) through some number of increasingly complex levels, evaluating many models and retaining at each level some number of models specified in the configuration of the model run. This approach identifies the best models for a particular data set, and suggests models on which to run the Fit process which allows one to examine a particular model in full detail.

2.4.4. Search Strategy and Implementation

To identify optimal models within this vast lattice, we employ a bottom-up beam search strategy using the Occam3 software developed at Portland State University. This approach begins with the independence model (no predictive relationships) and systematically adds components that maximize information gain while maintaining statistical significance.

Our search configuration included:

Search direction: Bottom-up

Search width: 3 (number of models retained at each level)

Search levels: 7 (maximum number of complexity levels explored)

Search criteria to retain models at all levels: dBIC (delta Bayesian Information Criterion)

Alpha threshold: 0.05 (statistical significance threshold)

This approach efficiently searches an extremely large space of possible directed models for the 23 IVs and one DV in our dataset without exhaustively enumerating all possible structures.

2.4.5. Model Evaluation Metrics

Models were evaluated using multiple information-theoretic criteria including:

Information content, Inf: Proportion of system constraint captured, scaled from 0 (independence model) to 1 (data)

Percent reduction in uncertainty, %dH(DV): Direct measure of how much the model reduces uncertainty about fire size, often the most useful metric. Because uncertainty has a logarithm in its mathematical expression even seemingly small values such as 8% can represent a large effect size such as a shift from 2:1 odds to 1:2 odds (Zwick, 2004).

dBIC (ΔBIC): Bayesian Information Criterion difference (from a reference model), a conservative metric balancing accuracy and complexity

dAIC (ΔAIC): Akaike Information Criterion difference (from a reference model), offering a less conservative alternative complexity-adjusted measure

Classification accuracy: Percentage of correctly classified instances (small vs. large fires) (This is a general machine learning metric, not an information theoretic metric.)

While dBIC & dAIC measures were closely tracked, our primary criterion for model selection is a balance of %dH and %Cover, as these metrics tend to move in opposite directions. An increase in reduction of uncertainty is typically accompanied by reduction in the %Cover. The incremental alpha criterion picks the most complex model that is statically significant relative to the independence model reference and for which there’s a path from the reference to the model where every increment of complexity is also significant. All of the pyrome signature models that were evaluated using Fit for this study have a significant Incremental Alpha.

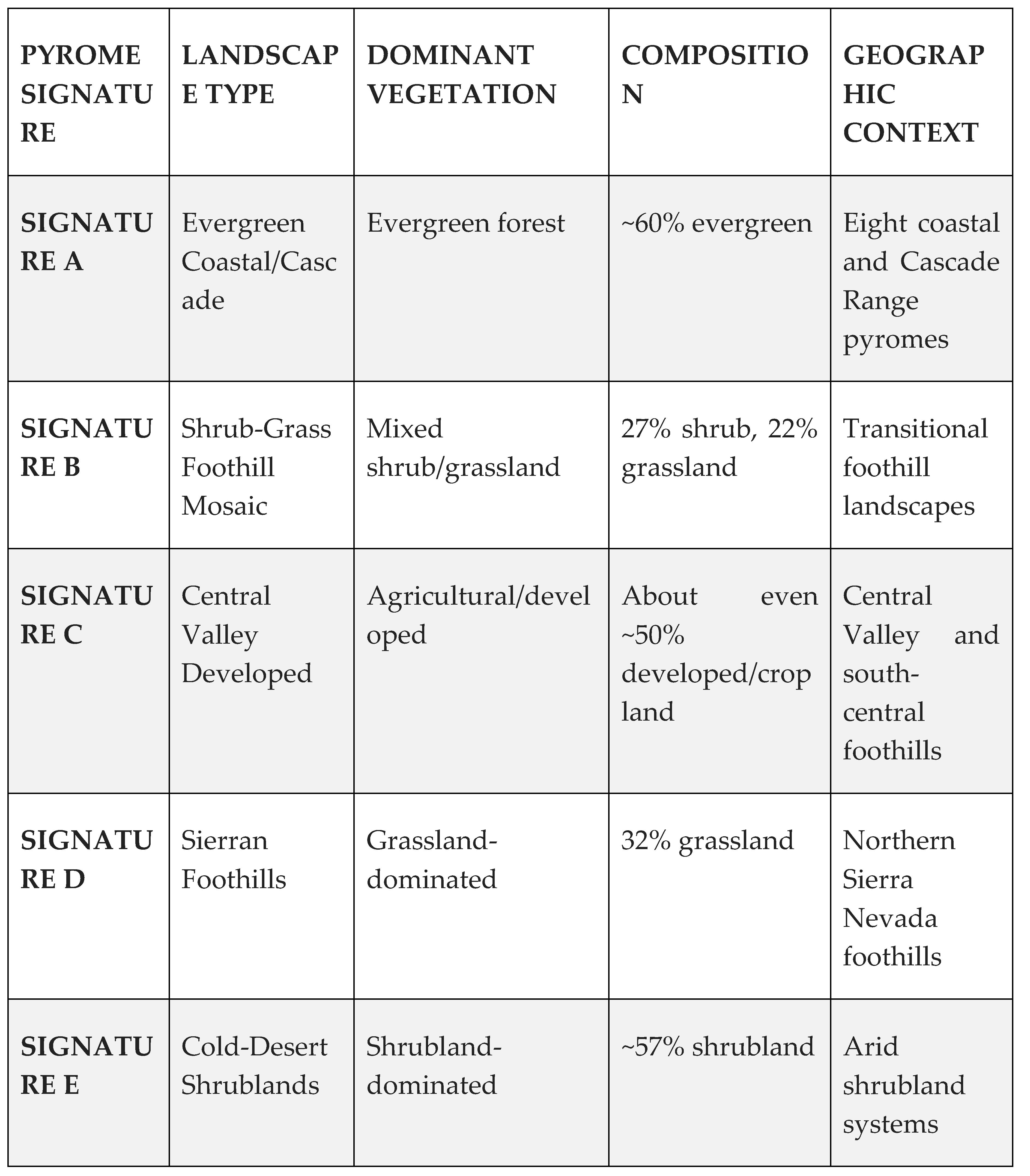

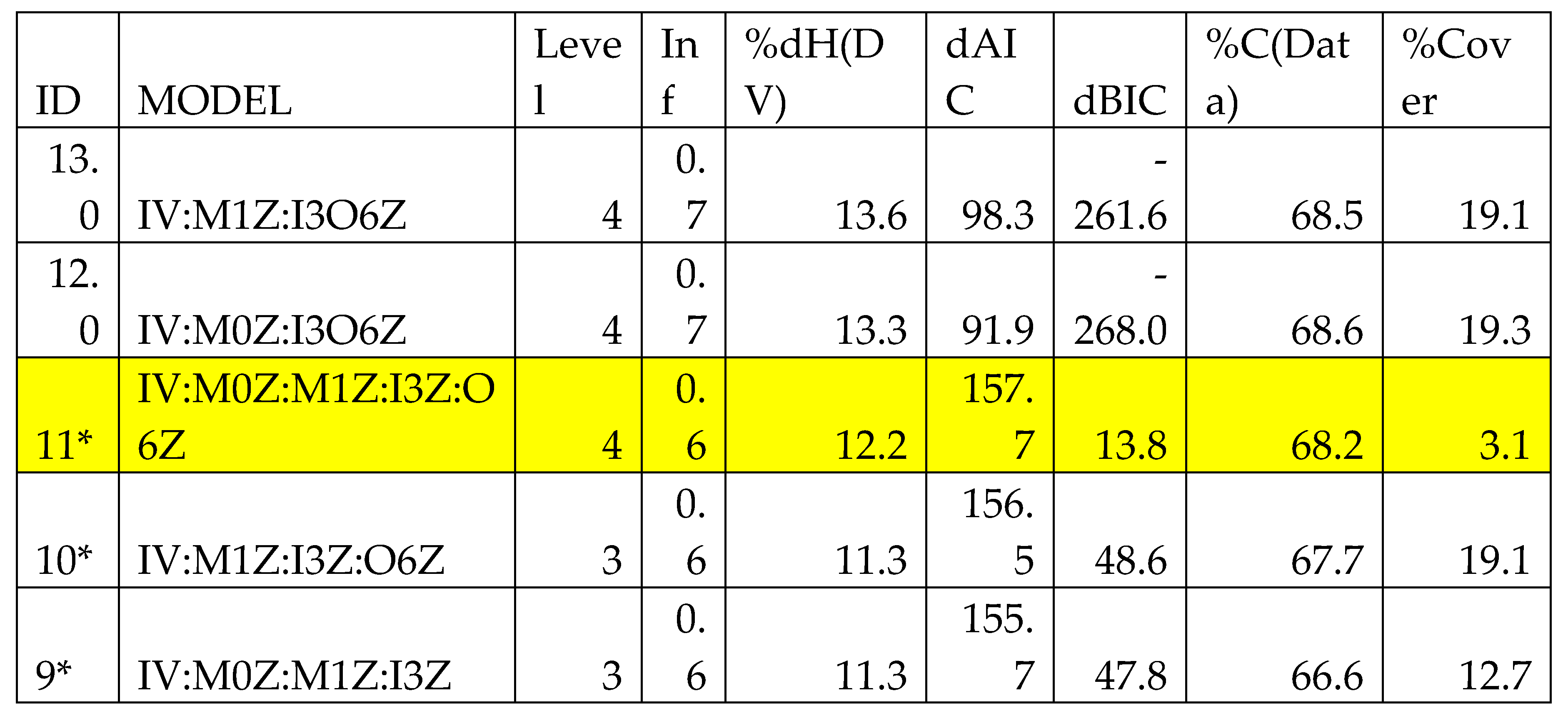

Table 2.

– Search output for pyrome signature B. A * in the ID column indicates a statistically significant model. Model structure is discussed in section 2.4.3. For this run, at each level only 3 models are retained, one extra relation is added per level. Metrics are discussed in section 2.4.5, and are in the next 4 columns. These are followed by %Correct, and finally %cover, the percent of the multivariate states of the predicting IVs that are actually present in the data.

Table 2.

– Search output for pyrome signature B. A * in the ID column indicates a statistically significant model. Model structure is discussed in section 2.4.3. For this run, at each level only 3 models are retained, one extra relation is added per level. Metrics are discussed in section 2.4.5, and are in the next 4 columns. These are followed by %Correct, and finally %cover, the percent of the multivariate states of the predicting IVs that are actually present in the data.

The output from a Search “run” is shown in

Table 2, this is the actual output for signature group B (Mixed shrub–grass foothill mosaic). The highlighted row in the table indicates the model that was chosen for Fit processing. The %Cover, while low, is acceptable given the ecological constraints of the pyrome group. Not all NLCD classes will be present, for example evergreen forest would be rare or absent in a desert ecoregion.

2.4.6. Fit Analysis and Interpretation

After identifying candidate models through Occam’s Search function, we conducted detailed Fit analysis to examine exactly how vegetation patterns influence fire outcomes. The Occam Fit function calculated:

Tables of conditional probabilities (given in %) of the two DV states given every combination of the states of the predictive IVs, classification rules for fire size prediction, and p-values for the statistical significance of the prediction rules (the probability of a Type 1 error in rejecting the hypothesis that the model conditional probabilities are the same as the DV margins of (50%, 50%).

Performance metrics including sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score

Tables of conditional DV probabilities, prediction rules, and p-values for each component relation

This detailed output enabled not just identification of which variables predict fire size, but specific understanding of the configurations most associated with large fire occurrence.

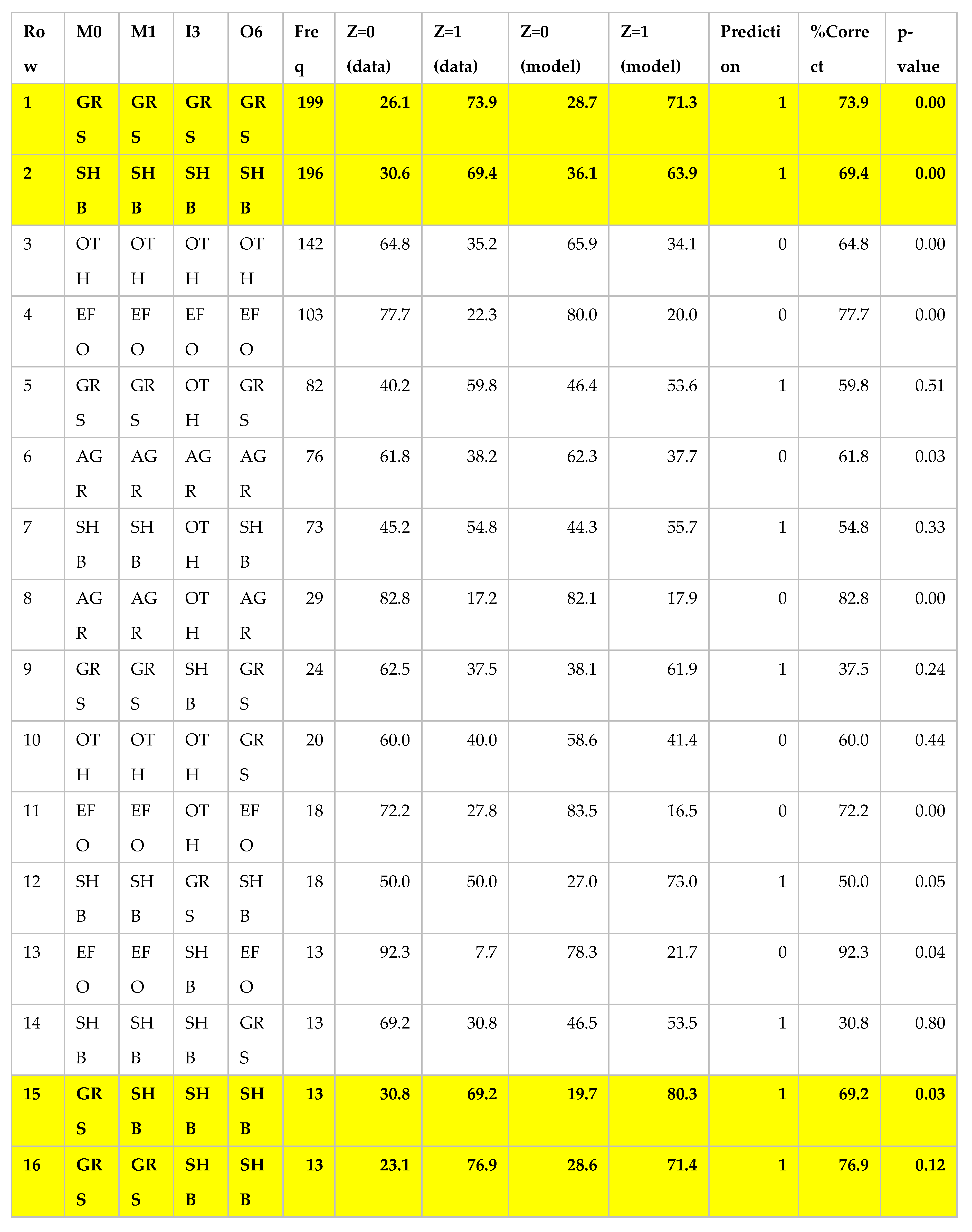

Table 3.

Example Fit output for model IV:M0Z:M1Z:I3Z:O6Z chosen as the best model by AIC and highlighted in Table 2. First four columns are the IVs in this model: Middle ring of layers 0 (T) and 1 (T-5), Inner ring of layer 4 (T-20), and Outer ring of layer 6 (T-30). Table is sorted on frequency. The next four columns are the conditional probability distribution, p(Z|IV) of the data for this each IV state, and the model’s predicted conditional distribution, pmodel(Z|IV). The prediction column states the Z value predicted by this model for this particular IV state. %Correct is the accuracy of the model prediction for this IV state, p-value is reported last. GRS is Grassland, SHB is Shrub/Scrub, EFO is Evergreen Forest, AGR is Cultivated Crops, & OTH is our bin for the “non-vegetated” classes). Yellow bold draws attention to the rows with high probability of large fire predicted by this model for this configuration of NLCD values.

Table 3.

Example Fit output for model IV:M0Z:M1Z:I3Z:O6Z chosen as the best model by AIC and highlighted in Table 2. First four columns are the IVs in this model: Middle ring of layers 0 (T) and 1 (T-5), Inner ring of layer 4 (T-20), and Outer ring of layer 6 (T-30). Table is sorted on frequency. The next four columns are the conditional probability distribution, p(Z|IV) of the data for this each IV state, and the model’s predicted conditional distribution, pmodel(Z|IV). The prediction column states the Z value predicted by this model for this particular IV state. %Correct is the accuracy of the model prediction for this IV state, p-value is reported last. GRS is Grassland, SHB is Shrub/Scrub, EFO is Evergreen Forest, AGR is Cultivated Crops, & OTH is our bin for the “non-vegetated” classes). Yellow bold draws attention to the rows with high probability of large fire predicted by this model for this configuration of NLCD values.

The Fit output is quite voluminous when the model is complex. Table 3 shows a medium complexity example with four IVs each having 8 possible states. This is the model chosen from Table 3 as the best representative for signature group B, and in its entirety shows every possible combination in this data set (126 rows for these data). Here we show just the top section of the table, sorted in reverse order by frequency of occurrence of this specific combination of IV states in this data set. The data columns (Z=0 & Z=1) are showing the distribution of 1’s and 0’s in this data set, for this each combination of IV values. Note that when the model is correct, the % correct is the probability of the predicted state (either Z=0 or Z-=1) in the data itself. The model is correct for all IV states (rows) except for rows 9 and 14. In this table the p-values vary widely, but in the rows that are most important (high frequency, and correct prediction) they are significant. (In the two rows where the prediction is incorrect, the p-values are very far from significant.) In this table we see combinations of all GRS (Grassland) are the highest frequency combination, and also nearly the most fire-prone (71.3%), only exceeded by rows 15 & 17 which are mixtures of shrubs & grasses. Row 2 is all Shrub/Scrub and has a high probability of large fires according to the data and our model. This model includes layer 6 (06), which is from 30 years prior, as a significant predictor of the DV. If we wanted to drill down and see the direct effect of IV O6 on the model, there are sub-tables that show the direct contribution of each element of the model.

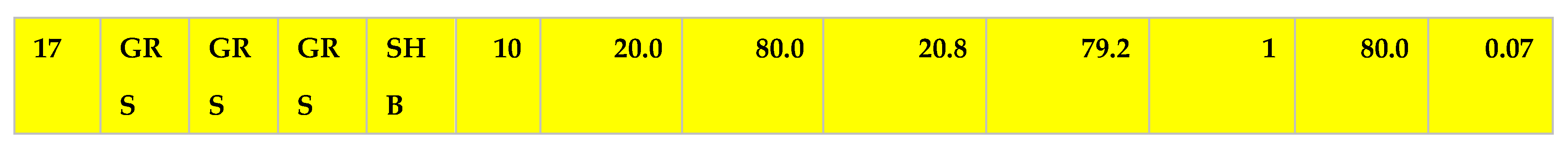

Table 4.

A & B – A (left) Confusion matrix for pyrome Signature B model IV:M0Z:M1Z:I3Z:O6Z. TN is True Negative, FN is False Negative, FP is False Positive, & TP is True Positive. The marginals are the total row and column counts. B (right) performance metrics for this model.

Table 4.

A & B – A (left) Confusion matrix for pyrome Signature B model IV:M0Z:M1Z:I3Z:O6Z. TN is True Negative, FN is False Negative, FP is False Positive, & TP is True Positive. The marginals are the total row and column counts. B (right) performance metrics for this model.

In addition to the detailed output excerpted in

Table 3, the Fit process produces a Confusion Matrix, as seen in

Table 4A,B. Here we see a decent F1 score, and only 149 falsely categorized large fires (FN), however we are over-predicting large fires as shown with the 252 events in the FP category.

2.4.7. Validation Approach

We implemented a rigorous validation strategy to ensure model reliability. This included a holdout approach with 20% of wildfire data reserved for testing. The %Correct on the test and train data corresponded well enough to confirm that the models were robust, so final Fit models were run on the entire pyrome data set without holding out any test data.

Additionally, we performed five-fold cross-validation using different random seeds (11, 22, 33, 42, 55) for sampling the small fires, which greatly outnumber large fires in the natural distribution (

Figure 6). Results remained consistent across all sampling seeds, confirming the robustness of our findings, with the final analysis using seed 55.