Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

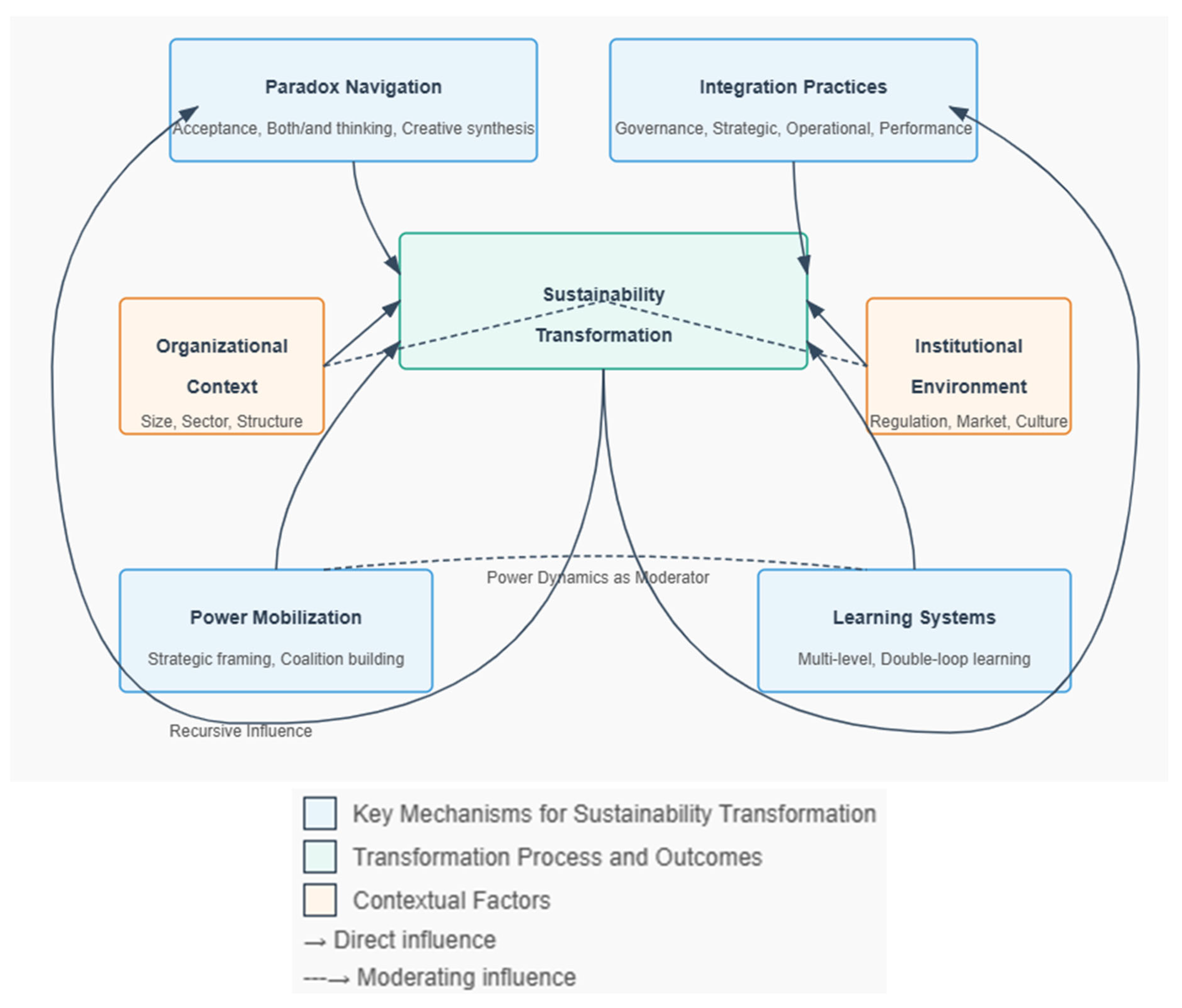

- What organizational capabilities enable effective navigation of sustainability paradoxes and tensions?

- How do organizations successfully integrate sustainability throughout their systems rather than compartmentalizing it?

- How do power dynamics and contextual factors influence the effectiveness of sustainability transformation approaches?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainability Paradoxes and Tensions

2.2. Integration Mechanisms for Sustainability

2.3. Power Dynamics in Sustainability Transformations

2.4. Organizational Learning for Sustainability

2.5. Contextual Factors in Sustainability Transformation

2.6. Institutional Logics and Competing Demands

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Philosophy and Approach

3.2. Research Design

- Quantitative survey (n=234) of sustainability professionals across multiple sectors

- Semi-structured interviews (n=42) with organizational change agents and leaders

- Comparative case studies (n=6) of organizations demonstrating different transformation patterns

3.3. Sampling and Participants

3.4. Data Collection

- Interviews with diverse organizational members (6-8 per organization)

- Internal documentation on sustainability initiatives

- Public sustainability reports and communications (5 years of historical data)

- Observational data from site visits and meetings (10-15 hours per organization)

- Archival data on organizational history and context

- Environmental performance metrics: Percentage reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (past three years), waste diversion rates, energy efficiency improvements, and water usage reduction

- Innovation indicators: Number of sustainability innovations launched, percentage of products/services redesigned with sustainability criteria, and R&D investment in sustainability solutions

- Governance indicators: Presence of board-level sustainability committee, proportion of executive compensation tied to sustainability metrics, and quality of sustainability disclosure

- External validation: Third-party sustainability ratings (e.g., CDP scores, DJSI inclusion), industry sustainability awards, and NGO recognition

3.5. Data Analysis

- Initial coding using a preliminary coding scheme derived from the theoretical framework

- Coding refinement through comparison and discussion among three researchers

- Theme development organizing codes into potential themes and subthemes

- Theme review in relation to coded extracts and the entire dataset

- Theme definition with clear naming and identification of representative quotes

- Cross-case analysis to identify patterns, similarities, and differences

4. Results

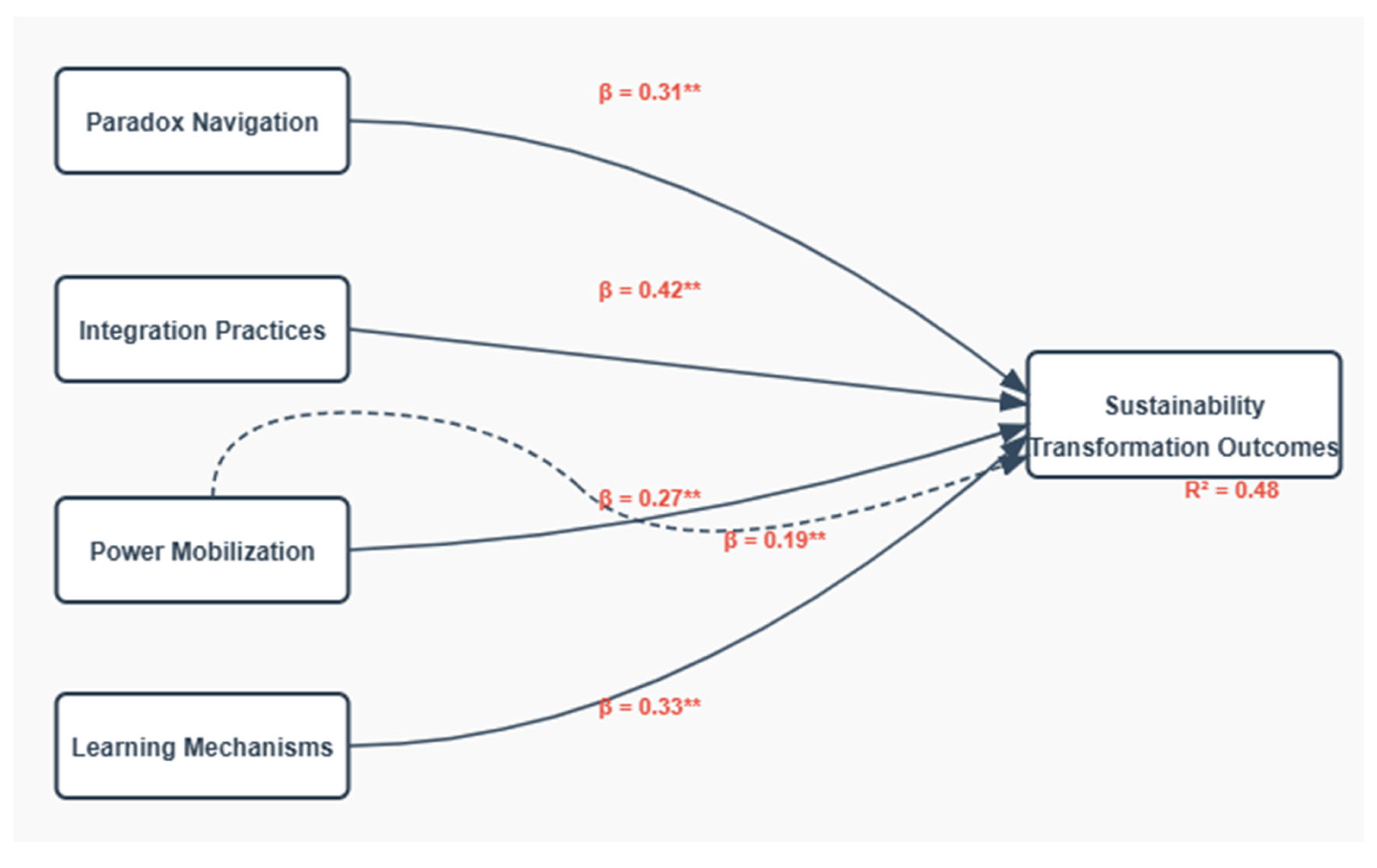

4.1. Quantitative Results: Relationships Between Key Constructs

- Sectoral differences: The relationship between paradox navigation and transformation outcomes was stronger in manufacturing (β = 0.38, p < 0.01) than services (β = 0.24, p < 0.05), suggesting that manufacturing organizations face more complex sustainability tensions requiring sophisticated navigation capabilities. Conversely, power mobilization had stronger effects in service organizations (β = 0.35, p < 0.01) than in manufacturing (β = 0.22, p < 0.05), reflecting the more relationship-based nature of service contexts.

- Size differences: Paradox navigation capabilities had stronger effects in larger organizations (β = 0.37, p < 0.01) than smaller ones (β = 0.24, p < 0.05), suggesting that managing competing demands becomes more critical as organizational complexity increases. In contrast, integration practices showed more consistent effects across organizational sizes, indicating their fundamental importance regardless of scale.

- Geographic differences: The effect of power mobilization on transformation outcomes was stronger in Asian organizations (β = 0.35, p < 0.01) than in North American (β = 0.22, p < 0.05) or European organizations (β = 0.25, p < 0.05), indicating important cultural variations in how power influences transformation processes. Learning mechanisms showed the most consistent effects across geographic contexts (β ranging from 0.30 to 0.36), suggesting the universal importance of learning capabilities.

- Performance level differences: The relationship between paradox navigation and transformation outcomes was stronger for organizations at earlier stages of sustainability transformation (β = 0.39, p < 0.01) than for sustainability leaders (β = 0.26, p < 0.05). Conversely, integration practices had stronger effects for advanced organizations (β = 0.45, p < 0.01) than beginners (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), suggesting that different capabilities may be critical at different stages of transformation.

4.2. Qualitative Findings: Mechanisms and Contextual Dynamics

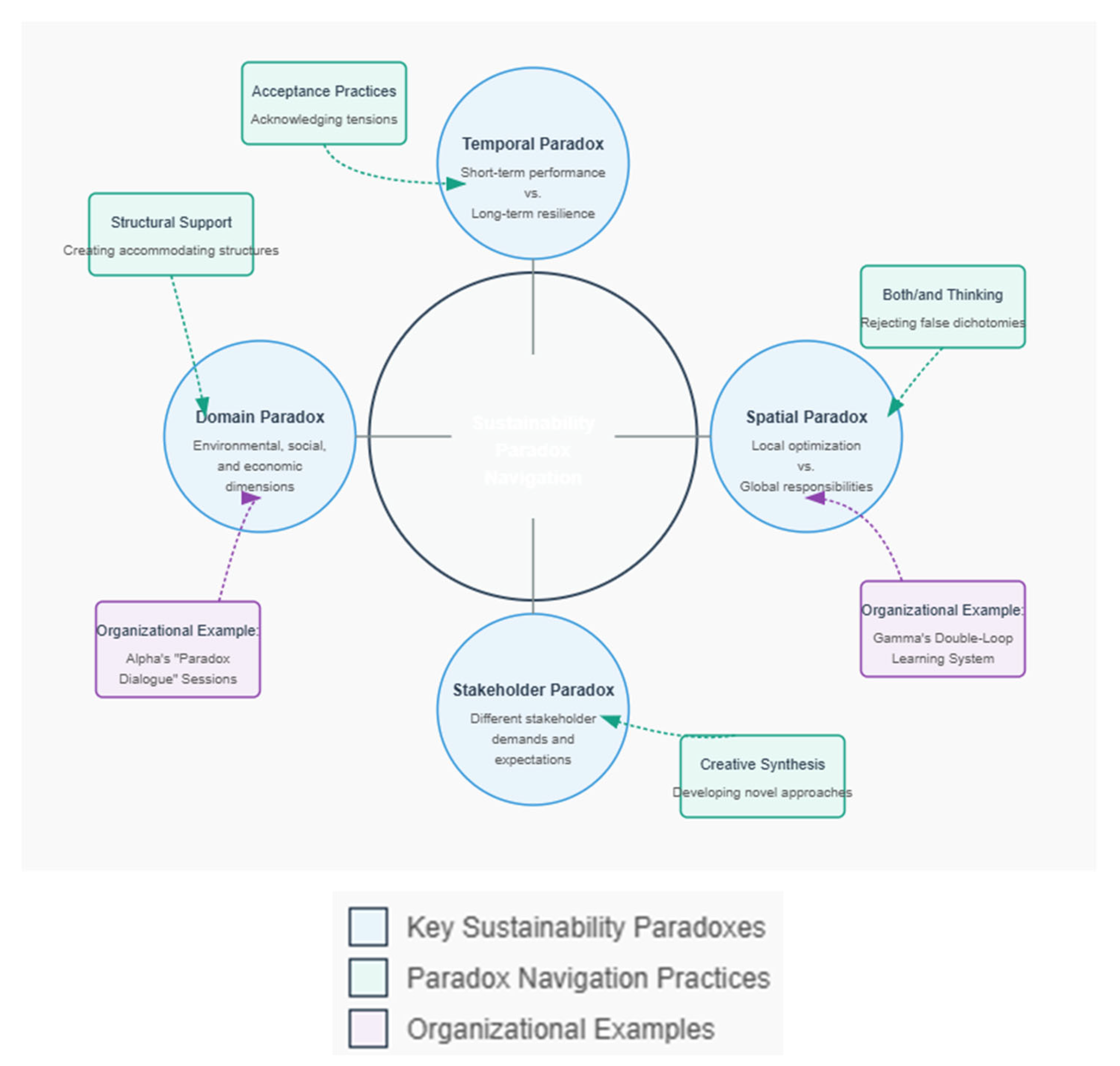

4.2.1. Paradox Navigation in Practice

- Acceptance practices: Acknowledging tensions without attempting to resolve them

- Both/and thinking: Rejecting false dichotomies between competing objectives

- Creative synthesis: Developing novel approaches that address multiple objectives simultaneously

- Structural support: Creating organizational structures that accommodate complexity

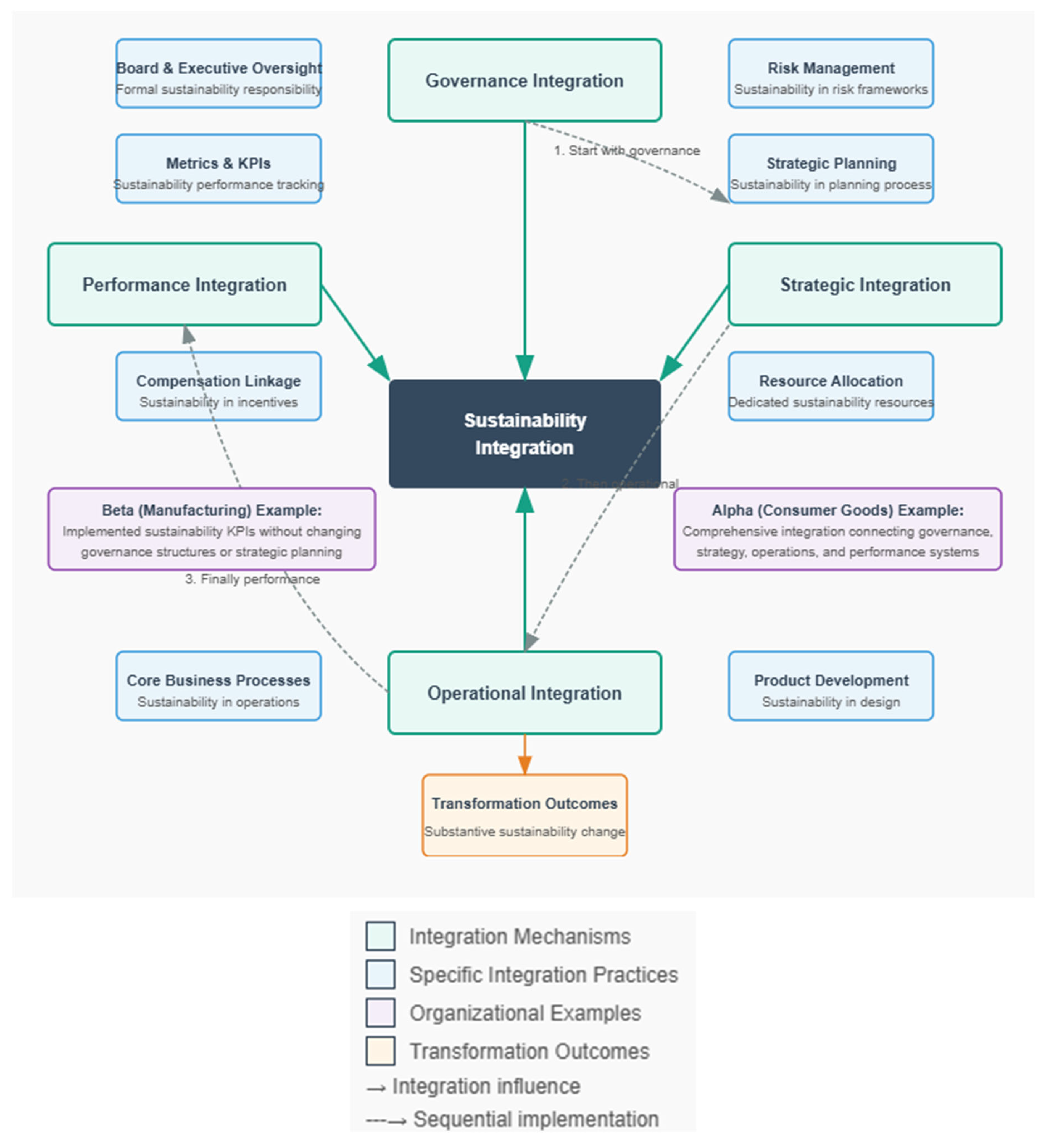

4.2.2. Integration Mechanisms and Their Effectiveness

- Governance integration: Sustainability oversight at board and executive levels

- Strategic integration: Sustainability embedded in strategic planning and goal-setting

- Operational integration: Sustainability incorporated into core business processes

- Performance integration: Sustainability metrics linked to compensation and advancement

4.2.3. Power Dynamics in Transformation Processes

- Strategic framing: Articulating sustainability in terms that resonated with powerful stakeholders’ priorities

- Coalition building: Creating networks of support across organizational boundaries

- Resource mobilization: Securing financial, human, and symbolic resources

- Timing exploitation: Identifying and leveraging windows of opportunity

4.2.4. Learning Systems for Sustainability

- Psychological safety: Creating environments where people felt safe discussing failures

- Feedback mechanisms: Developing robust approaches to monitoring and assessment

- Reflection practices: Institutionalizing regular reflection on experience

- Knowledge management: Creating systems to capture and share learning

4.3. Contextual Contingencies of Transformation

- Large incumbents benefit most from learning systems but struggle with integration practices

- Entrepreneurial organizations excel at integration but face challenges with power mobilization

- B2C sectors show high effectiveness with power mobilization strategies, leveraging consumer pressure

- Global organizations require strong learning systems and power mobilization to manage complexity

- Paradox navigation is most effective in public sector contexts where multiple stakeholder demands are common

4.4. Temporal Dynamics of Transformation

5. Discussion

5.1. Paradox Navigation as a Core Sustainability Capability

5.2. Integration Mechanisms for Embedding Sustainability

5.3. Power Dynamics and Sustainability Transformation

5.4. Contextual Contingencies and Tailored Sustainability Approaches

5.5. Institutional Logics and Competing Demands

5.6. Practical Implications for Sustainable Organizations

- Establish regular ‘paradox dialogue sessions’ where cross-functional teams identify and discuss sustainability tensions without pressure for immediate resolution, as successfully implemented at Alpha Corporation.

- Train managers in specific both/and thinking techniques, such as the ‘polarity mapping’ exercise used by Gamma Corporation, which visually charts the benefits and drawbacks of focusing exclusively on either pole of a paradox.

- Create dedicated innovation forums focused on creative synthesis of competing demands, structured around the ‘integrative solution workshops’ pioneered by Delta Corporation, where cross-functional teams use design thinking approaches to develop solutions that address multiple objectives simultaneously.

- Implement structural supports for paradox navigation through ‘tension owner’ roles, as established at Epsilon Corporation, where specific individuals are responsible for ensuring that key sustainability tensions receive ongoing attention rather than being resolved prematurely.

- Develop a comprehensive integration approach that connects governance, strategy, operations, and performance systems. Begin with strategic integration to create the foundation for operational changes, which then require performance metrics for accountability.

- Address power dynamics explicitly by mapping the power landscape, building coalitions across organizational boundaries, and framing sustainability initiatives in terms that resonate with key decision-makers’ priorities.

- Invest in multi-level learning systems that connect individual, group, and organizational learning. Create psychological safety for discussing failures, implement regular reflection processes, and develop knowledge management systems that capture and share sustainability insights.

- Tailor approaches to organizational context rather than applying universal best practices. Consider how sector, size, history, and institutional position shape the most appropriate transformation strategies.

- Recognize the temporal dynamics of transformation, with different capabilities becoming more critical at different stages. Develop paradox navigation capabilities early to create the foundation for integration, while building learning systems that enable continuous adaptation as transformation progresses.

- Balance incremental improvement with transformative change by embedding sustainability within existing systems while continuously questioning whether those systems themselves need transformation to become inherently more sustainable.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Contributions

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

6.3. Concluding Remarks

Informed Consent Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Instrument

- Which sector best describes your organization?

- Manufacturing

- Services

- Public Sector

- Non-profit

- Other (please specify): _______

- What is the size of your organization?

- Less than 250 employees

- 250-1,000 employees

- 1,000-10,000 employees

- More than 10,000 employees

- In which region is your organization headquartered?

- North America

- Europe

- Asia

- Latin America

- Africa

- Oceania

- Which best describes your role in the organization?

- C-Suite/Executive

- Sustainability Director/Manager

- Functional Manager

- Sustainability Team Member

- Other (please specify): _______

- How long have you been involved with sustainability initiatives?

- Less than 1 year

- 1-3 years

- 4-7 years

- 8+ years

- Sustainability-related regulations in our industry are stringent.

- Regulatory compliance related to sustainability is strictly enforced.

- Regulatory requirements for sustainability reporting are comprehensive.

- Regulatory frameworks provide clear guidance for sustainability practices.

- Regulations incentivize proactive sustainability action rather than just compliance.

- Our customers actively demand sustainable products/services.

- Competitors in our industry are advancing sustainability initiatives.

- Sustainability performance influences our market position.

- Investors/funders evaluate our organization on sustainability criteria.

- Our supply chain partners expect sustainability commitments from us.

- The societies in which we operate value environmental protection.

- Social expectations regarding corporate responsibility are high.

- Sustainability is viewed as a legitimate business concern in our context.

- There is public pressure for organizations like ours to address sustainability challenges.

- Industry associations promote sustainability as a standard practice.

- Technical solutions for our sustainability challenges are readily available.

- Our industry has established sustainability metrics and standards.

- Knowledge resources about sustainability practices are accessible.

- Collaborative platforms for sustainability exist in our industry.

- Technology enables sustainability innovation in our sector.

- Sustainability issues are framed in terms of business opportunities.

- Sustainability initiatives are connected to core organizational values.

- Sustainability challenges are positioned as innovation opportunities.

- Sustainability is framed differently for different stakeholder groups.

- Long-term sustainability vision is connected to short-term actions.

- Sustainability champions form alliances across departments.

- Supporters of sustainability initiatives are strategically identified and engaged.

- Partnerships with external stakeholders advance internal sustainability goals.

- Cross-functional teams collaborate on sustainability challenges.

- Senior leadership support for sustainability initiatives is actively cultivated.

- Sustainability champions secure dedicated resources for initiatives.

- External funding sources for sustainability projects are identified and accessed.

- Existing organizational resources are repurposed for sustainability work.

- Human resources with sustainability expertise are strategically deployed.

- Success stories are leveraged to gain additional resource commitments.

- Sustainability champions navigate power dynamics to advance initiatives.

- Resistance to sustainability initiatives is anticipated and addressed.

- Informal influence networks are activated to support sustainability efforts.

- Windows of opportunity for advancing sustainability are strategically exploited.

- Potential opponents to sustainability initiatives are converted or neutralized.

- Our organization acknowledges tensions between competing sustainability objectives.

- We recognize that sustainability involves inherent contradictions.

- Competing stakeholder demands regarding sustainability are openly discussed.

- Trade-offs between short-term and long-term considerations are explicitly addressed.

- We accept that not all sustainability tensions can be permanently resolved.

- Our organization seeks solutions that address multiple objectives simultaneously.

- We reject the notion that economic and environmental goals are inherently opposed.

- Our approach integrates social and environmental considerations rather than separating them.

- We view sustainability tensions as potential sources of innovation.

- Our decision processes accommodate complexity rather than forcing oversimplification.

- We develop novel approaches that address seemingly contradictory requirements.

- Our organization creates innovative solutions to sustainability paradoxes.

- We reconfigure resources to overcome apparent trade-offs.

- Our sustainability strategies transcend conventional either/or thinking.

- We transform tensions into opportunities for differentiation.

- Our organizational structure accommodates competing sustainability demands.

- We have formal mechanisms for addressing sustainability tensions.

- Resources are allocated to explore solutions to sustainability paradoxes.

- Decision processes allow for consideration of multiple sustainability criteria.

- Leadership encourages constructive engagement with sustainability tensions.

- Employees receive training on sustainability-related knowledge and skills.

- Sustainability considerations are included in professional development plans.

- External sustainability expertise is brought in to enhance internal capabilities.

- Employees are encouraged to experiment with sustainability innovations.

- Individual sustainability learning objectives are established and tracked.

- Teams reflect on sustainability challenges and experiences.

- Cross-functional groups share sustainability knowledge and insights.

- Sustainability communities of practice operate within the organization.

- Team-level sustainability goals promote collective learning.

- Groups engage in structured reflection on sustainability initiatives.

- Sustainability experiences are systematically documented and shared.

- Formal processes exist to review and learn from sustainability initiatives.

- Sustainability metrics are used to guide organizational learning.

- Knowledge management systems capture sustainability insights.

- Learning from sustainability initiatives influences strategic decisions.

- Our organization participates in sustainability learning networks.

- We share sustainability knowledge with external stakeholders.

- Cross-organizational collaborations enhance our sustainability learning.

- Industry partnerships advance collective sustainability knowledge.

- We learn from sustainability leaders outside our organization.

- Our board has formal responsibility for sustainability oversight.

- Sustainability considerations are integrated into risk management processes.

- Executive compensation is linked to sustainability performance.

- Sustainability governance includes diverse stakeholder perspectives.

- Formal accountability mechanisms exist for sustainability performance.

- Sustainability is a core element of our organizational strategy.

- Strategic planning processes incorporate sustainability considerations.

- Sustainability goals are aligned with overall business objectives.

- Long-term sustainability vision guides strategic decisions.

- Resource allocation reflects strategic sustainability priorities.

- Sustainability criteria are embedded in operational decision-making.

- Core business processes incorporate sustainability considerations.

- Product/service development integrates sustainability requirements.

- Procurement decisions include sustainability criteria.

- Everyday operations reflect sustainability commitments.

- Sustainability metrics are integrated with other performance indicators.

- Performance reviews include sustainability-related objectives.

- Sustainability performance influences career advancement.

- Reward systems recognize sustainability contributions.

- Sustainability targets are cascaded throughout the organization.

- Our organization has significantly reduced its environmental footprint.

- Resource efficiency has improved substantially.

- Our products/services have reduced environmental impacts.

- We have innovated to address environmental challenges.

- Our environmental performance exceeds regulatory requirements.

- Our organization contributes positively to community well-being.

- We have improved social conditions in our value chain.

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion have advanced within our organization.

- Our products/services create social benefits.

- We actively address human rights considerations.

- Sustainability initiatives contribute to financial performance.

- Our sustainability positioning enhances market opportunities.

- Sustainability-related innovation creates economic value.

- We have reduced costs through sustainability improvements.

- Our business model is evolving to be inherently more sustainable.

- Sustainability has fundamentally changed how we define success.

- Our organizational purpose has evolved to incorporate sustainability.

- Sustainability considerations have transformed decision-making processes.

- Our organizational culture increasingly embodies sustainability values.

- Sustainability has become integral to our organizational identity.

- What strategies have been most effective in advancing sustainability in your organizational context?

- How does your organization navigate tensions between different sustainability objectives?

- What learning approaches have been most valuable for building sustainability capabilities?

- What advice would you give to others seeking to advance sustainability transformation in similar organizations?

- Could you briefly describe your role in the organization and how it relates to sustainability initiatives?

- How long have you been involved with sustainability work, both in this organization and in your career overall?

- How would you characterize your organization’s overall approach to sustainability?

- What sustainability initiatives or transformations has your organization undertaken in recent years?

- How would you describe the institutional environment in which your organization operates regarding sustainability?

- a. Probe: Regulatory pressures

- b. Probe: Market expectations

- c. Probe: Stakeholder demands

- d. Probe: Industry norms

- Which external factors have most significantly influenced your organization’s sustainability approach?

- 3.

- Could you describe specific instances where external conditions have either enabled or constrained your sustainability efforts?

- 4.

- How has your organization sought to influence the broader institutional environment regarding sustainability?

- 5.

- What collaborative arrangements with external stakeholders have been important for your sustainability work?

- Who have been the key champions or change agents for sustainability in your organization?a. Probe: Their positions and sources of influence

- 2.

- What strategies have sustainability champions used to advance initiatives within the organization?

- 3.

- Could you describe a specific sustainability initiative and how change agents navigated organizational dynamics to implement it?

- 4.

- How do sustainability champions in your organization navigate power dynamics?

- 5.

- What have been the most effective leadership approaches for advancing sustainability in your context?

- What significant tensions or competing demands has your organization encountered in sustainability work?

- 2.

- Could you describe a specific situation where your organization faced seemingly contradictory sustainability objectives? How was this handled?

- 3.

- How does your organization approach the relationship between financial performance and sustainability objectives?

- 4.

- What organizational structures or processes help your organization navigate sustainability tensions?

- 5.

- How has your organization’s approach to sustainability paradoxes evolved over time?

- How does your organization develop sustainability capabilities?

- 2.

- Could you describe how your organization learns from sustainability initiatives, both successful and unsuccessful ones?

- 3.

- What mechanisms exist for sharing sustainability knowledge across the organization?

- 4.

- How does your organization engage with external sources of sustainability knowledge?

- How is sustainability integrated into your organization’s governance structures?

- 2.

- How does sustainability connect to your organization’s strategy and core business?

- 4.

- How does your organization’s performance management system address sustainability?

- 5.

- What have been the most effective approaches for embedding sustainability throughout your organization rather than isolating it?

- How would you characterize the progress your organization has made in sustainability transformation?

- 2.

- What do you see as the most significant changes in how your organization approaches sustainability?

- 3.

- What have been the most challenging aspects of sustainability transformation in your organization?

- 4.

- If you were to advise another organization in your sector on sustainability transformation, what key lessons would you share?

- Is there anything else about sustainability transformation in your organization that you think is important for us to understand?

- Do you have any questions about this research or how your insights will be used?

References

- Aguinis, H. , & Glavas, A. (2013). Embedded versus peripheral corporate social responsibility: Psychological foundations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 6(4), 314-332. [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. , & Schön, D. A. (1996). Organizational learning II: Theory, method, and practice. Addison-Wesley.

- Avelino, F. (2021). Theories of power and social change. Power contestations and their implications for research on social change and innovation. Journal of Political Power, 14(3), 425-448. [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F. , & Rotmans, J. (2009). Power in transition: An interdisciplinary framework to study power in relation to structural change. European Journal of Social Theory, 12(4), 543-569. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. B. (2003). Who sustains whose development? Sustainable development and the reinvention of nature. Organization Studies, 24(1), 143-180. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. B. (2011). Embedding sustainability across the organization: A critical perspective. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(4), 719-731. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. B. , & Arjaliès, D. L. (2022). Celebrating the end of enlightenment: Organization theory in the age of the Anthropocene and Gaia (and why neither is the solution to our ecological crisis). Organization Theory, 3(1), 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J. , & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419-1440. [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J. , & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing—Insights from the study of social enterprises. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 397-441. [CrossRef]

- Benn, S. , Dunphy, D., & Griffiths, A. (2014). Organizational change for corporate sustainability. Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R. (1978). A realist theory of science. Harvester Press.

- Boiral, O. (2007). Corporate greening through ISO 14001: A rational myth? Organization Science, 18(1), 127-146. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [CrossRef]

- Bromley, P. , & Powell, W. W. (2012). From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. Academy of Management Annals, 6(1), 483-530. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A. , Costa, R., Levialdi, N., & Menichini, T. (2018). Integrating sustainability into strategic decision-making: A fuzzy AHP method for the selection of relevant sustainability issues. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 139, 155-168. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Creswell, J. W. , & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Crilly, D. , Hansen, M., & Zollo, M. (2016). The grammar of decoupling: A cognitive-linguistic perspective on firms’ sustainability claims and stakeholders’ interpretation. Academy of Management Journal, 59(2), 705-729. [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, F. , & Grosvold, J. (2017). Environmental managers and institutional work: Reconciling tensions of competing institutional logics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(2), 263-291. [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, F. , Branicki, L., & Brammer, S. (2017). Managing carbon aspirations: The influence of corporate climate change targets on environmental performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(1), 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M. A. , & Toffel, M. W. (2008). Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strategic Management Journal, 29(10), 1027-1055. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science, 60(11), 2835-2857. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. , & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25-32. [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I. , Schäpke, N., Caniglia, G., Patterson, J., Hultman, J., van Mierlo, B., Säwe, F., Wiek, A., Wittmayer, J., Aldunce, P., Al Waer, H., Battacharya, N., Bradbury, H., Carmen, E., Colvin, J., Cvitanovic, C., D’Souza, M., Gopel, M., Goldstein, B.,... Wyborn, C. (2018). Ten essentials for action-oriented and second order energy transitions, transformations and climate change research. Energy Research & Social Science, 40, 54-70. [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M. D. , Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6pt2), 2134-2156. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P., & Spicer, A. (2014). Power in management and organization science. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 237-298. [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P., Amelio, S., Papagiannis, F., & Michaelides, Z. (2021). Sustainability reporting practices and their social impact to NGO funding in Italy. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 79, 102085. [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M. , Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M., & Hultink, E. J. (2017). The Circular Economy–A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 757-768. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317-371. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T. , & Figge, F. (2011). Beyond the bounded instrumentality in current corporate sustainability research: Toward an inclusive notion of profitability. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(3), 325-345. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T. , Figge, F., Pinkse, J., & Preuss, L. (2018). A paradox perspective on corporate sustainability: Descriptive, instrumental, and normative aspects. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(2), 235-248. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A. J. (2018). The next phase of business sustainability. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 16(2), 34-39.

- Hoffman, A. J. , & Jennings, P. D. (2015). Institutional theory and the natural environment: Research in (and on) the Anthropocene. Organization & Environment, 28(1), 8-31. [CrossRef]

- Howard-Grenville, J. , Golden-Biddle, K., Irwin, J., & Mao, J. (2007). Under cover: Institutional pressures and identity work in an environmental consulting firm. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1515-1540. [CrossRef]

- Jay, J. (2013). Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 137-159. [CrossRef]

- Levy, D. , & Scully, M. (2007). The institutional entrepreneur as modern prince: The strategic face of power in contested fields. Organization Studies, 28(7), 971-991. [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, M. , & Wang, M. S. (2020). Into the clearing: Back to the future of constitutive institutional analysis. Organization Theory, 1(1), 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. , Carpenter, A., & Huisingh, D. (2015). A review of ‘theories of the firm’ and their contributions to corporate sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 106, 430-442. [CrossRef]

- Mahfooz, S. G. , Qureshi, A. M. A., & Lodhi, M. S. (2022). Organizational politics and organizational sustainability: Unlocking the black box of the relationship. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(1), 268-288. [CrossRef]

- Milne, M. J. , & Gray, R. (2013). W(h)ither ecology? The triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(1), 13-29. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M. , MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903. [CrossRef]

- Preiser, R. , Biggs, R., De Vos, A., & Folke, C. (2017). Social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems: Organizing principles for advancing research methods and approaches. Ecology and Society, 22(4), 32. [CrossRef]

- Schad, J. , Lewis, M. W., Raisch, S., & Smith, W. K. (2016). Paradox research in management science: Looking back to move forward. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 5-64. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A. , & Harvey, B. (2000). Environmental knowledge and the adoption of ready made environmental management solutions. Eco-Management and Auditing, 7(2), 74-81. [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S. , & Wagner, M. (2011). Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Business Strategy and the Environment, 20(4), 222-237. [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, D. , & Schramade, W. (2019). Principles of sustainable finance. Oxford University Press.

- Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities. Sage Publications.

- Sharma, G. , & Jaiswal, A. K. (2018). Unsustainability of sustainability: Cognitive frames and tensions in bottom of the pyramid projects. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(2), 291-307. [CrossRef]

- Siebenhüner, B., & Arnold, M. (2007). Organizational learning to manage sustainable development. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16(5), 339-353. [CrossRef]

- Slager, R. , Gond, J. P., & Crilly, D. (2020). Reactivity to sustainability metrics: A configurational study of motivation and capacity. Business Ethics Quarterly, 30(4), 455-485. [CrossRef]

- Slawinski, N. , Pinkse, J., Busch, T., & Banerjee, S. B. (2021). The role of paradox theory in decision making and management research. Organization & Environment, 34(1), 7-30. [CrossRef]

- Smith, W. K. , & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381-403. [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W. , & Cocklin, C. (2008). Conceptualizing a “sustainability business model”. Organization & Environment, 21(2), 103-127. [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C. , & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Sage.

- Thornton, P. H. , Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly.

- Van der Byl, C. A. , & Slawinski, N. (2015). Embracing tensions in corporate sustainability: A review of research from win-wins and trade-offs to paradoxes and beyond. Organization & Environment, 28(1), 54-79. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. , Whiteman, G., & Kennedy, S. (2021). Cross-scale systemic resilience: Implications for organization studies. Business & Society, 60(5), 1022-1049. [CrossRef]

- Wright, C. , & Nyberg, D. (2017). An inconvenient truth: How organizations translate climate change into business as usual. Academy of Management Journal, 60(5), 1633-1661. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sector | Manufacturing | 32% |

| Services | 28% | |

| Public Sector | 22% | |

| Non-profit | 18% | |

| Organization Size | <250 employees | 24% |

| 250-1000 employees | 31% | |

| 1000-10,000 employees | 27% | |

| >10,000 employees | 18% | |

| Geographic Region | North America | 38% |

| Europe | 29% | |

| Asia | 22% | |

| Other | 11% | |

| Respondent Role | C-Suite/Executive | 16% |

| Sustainability Director/Manager | 42% | |

| Functional Manager | 31% | |

| Other | 11% | |

| Sustainability Performance* | Leading | 22% |

| Advancing | 41% | |

| Beginning | 29% | |

| Lagging | 8% |

| Organization | Sector | Size | Transformation Approach | Institutional Context | Geographic Scope | Performance Trajectory* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Consumer Goods | Large | Strategic Integration | Mixed | Global | Accelerating |

| Beta | Manufacturing | Medium | Process Innovation | Challenging | Regional | Plateaued |

| Gamma | Financial Services | Large | Governance Reform | Supportive | Global | Accelerating |

| Delta | Healthcare | Large | Stakeholder Engagement | Mixed | National | Steadily improving |

| Epsilon | Social Enterprise | Small | Purpose-Driven | Mixed | Regional | Accelerating |

| Zeta | Public-Private Partnership | Medium | Collaborative | Supportive | National | Variable |

| Construct | Sample Items |

|---|---|

| Paradox Navigation Capabilities | “Our organization acknowledges tensions between competing sustainability objectives” |

| “We seek solutions that address multiple objectives simultaneously” | |

| “Our organization creates innovative solutions to sustainability paradoxes” | |

| “We have formal mechanisms for addressing sustainability tensions” | |

| Integration Practices | “Our board has formal responsibility for sustainability oversight” |

| “Sustainability is a core element of our organizational strategy” | |

| “Core business processes incorporate sustainability considerations” | |

| “Sustainability metrics are integrated with other performance indicators” | |

| Power Mobilization | “Sustainability champions form alliances across departments” |

| “Sustainability initiatives are framed in terms of core organizational values” | |

| “Resistance to sustainability initiatives is anticipated and addressed” | |

| “Windows of opportunity for advancing sustainability are strategically exploited” | |

| Learning Mechanisms | “Teams reflect on sustainability challenges and experiences” |

| “Formal processes exist to review and learn from sustainability initiatives” | |

| “Our organization participates in sustainability learning networks” | |

| “Sustainability metrics are used to guide organizational learning” | |

| Transformation Outcomes | “Sustainability has fundamentally changed how we define success” |

| “Our organization has significantly reduced its environmental footprint” | |

| “Our business model is evolving to be inherently more sustainable” | |

| “Sustainability considerations have transformed decision-making processes” |

| Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | Discriminant Validity* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paradox Navigation | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.68 | Yes |

| Integration Practices | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.72 | Yes |

| Power Mobilization | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.65 | Yes |

| Learning Mechanisms | 0.9 | 0.92 | 0.7 | Yes |

| Transformation Outcomes | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.74 | Yes |

| Theme | Subthemes | Example Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Paradox Navigation | Acceptance practices | Tension recognition, Comfort with ambiguity |

| Both/and thinking | Integrative solutions, Rejection of false dichotomies | |

| Creative synthesis | Novel approaches, Transcending trade-offs | |

| Structural support | Dialogue processes, Decision frameworks | |

| Integration Mechanisms | Governance integration | Board oversight, Risk integration |

| Strategic integration | Planning processes, Goal alignment | |

| Operational integration | Process embedding, Product development | |

| Performance integration | Metrics integration, Incentive systems | |

| Power Dynamics | Strategic framing | Business case, Value alignment |

| Coalition building | Cross-functional alliances, Executive sponsorship | |

| Resource mobilization | Budget allocation, Expertise deployment | |

| Timing exploitation | Crisis leverage, Opportunity windows | |

| Learning Systems | Psychological safety | Failure tolerance, Open dialogue |

| Reflection practices | Review processes, Learning debriefs | |

| Knowledge management | Documentation systems, Knowledge sharing | |

| Network learning | External partnerships, Collaborative platforms | |

| Contextual Factors | Regulatory environment | Compliance pressures, Policy incentives |

| Market dynamics | Customer demands, Competitive pressures | |

| Organizational characteristics | Size effects, Structural influences | |

| Cultural context | Societal expectations, Cultural norms | |

| Transformation Outcomes | Environmental outcomes | Footprint reduction, Resource efficiency |

| Social outcomes | Community impact, Labor conditions | |

| Economic outcomes | Cost savings, Market opportunities | |

| Transformative change | Purpose evolution, Decision process change | |

| Implementation Challenges | Resistance patterns | Passive resistance, Active opposition |

| Resource constraints | Budget limitations, Expertise gaps | |

| Competing priorities | Short-term pressures, Crisis diversion | |

| Measurement difficulties | Attribution challenges, Data limitations |

| Path | Coefficient | 95% CI | p-value | Effect Size (f²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paradox Navigation → Transformation Outcomes | 0.31 | [0.23, 0.39] | <0.01 | 0.15 |

| Integration Practices → Transformation Outcomes | 0.42 | [0.34, 0.50] | <0.01 | 0.25 |

| Power Mobilization → Transformation Outcomes | 0.27 | [0.19, 0.35] | <0.01 | 0.12 |

| Learning Mechanisms → Transformation Outcomes | 0.33 | [0.25, 0.41] | <0.01 | 0.16 |

| Power Mobilization × Integration Practices → Transformation Outcomes | 0.19 | [0.11, 0.27] | <0.01 | 0.08 |

| Quantitative Relationship | Qualitative Explanation | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Integration practices as strongest predictor (β = 0.42) | Integration embeds sustainability in core processes rather than treating it as peripheral | “The turning point was integrating sustainability criteria into our capital allocation process. Now it’s a core criterion in every investment decision, alongside financial returns and strategic fit.” (Participant 11, Energy) |

| Paradox navigation relationship with outcomes (β = 0.31) | Structured approaches to paradox navigation enable creative solutions to competing demands | “We used to try to resolve tensions between short-term financial performance and long-term sustainability investments by creating separate budgets. Now we explicitly discuss these tensions in our planning meetings and look for integrated solutions that advance both objectives.” (Participant 3, Manufacturing) |

| Power mobilization moderating integration (β = 0.19) | Integration effectiveness depends on power distribution and sustainability advocates’ influence | “Understanding the power landscape is essential. I’ve learned to map who has decision-making authority, who influences those decision-makers, and who might resist change. This mapping helps me develop targeted strategies for different stakeholders.” (Participant 7, Manufacturing) |

| Stronger paradox navigation effects in manufacturing (β = 0.38 vs. 0.24) | Manufacturing faces more complex material trade-offs than service organizations | “In manufacturing, our sustainability transformation involved complex trade-offs between material choices, energy sources, production processes, and supply chain arrangements—all with different sustainability implications that couldn’t be optimized simultaneously.” (Beta, Manager) |

| Stronger integration effects in advanced organizations (β = 0.45 vs. 0.33) | Integration creates compound benefits as it matures and spreads throughout systems | “As integration deepened over time, we experienced accelerating benefits. Early wins were modest, but as sustainability became embedded in multiple systems, the combined effect transformed how we operate.” (Alpha, Executive) |

| Organizational Context | Dominant Transformation Approach | Critical Success Factors | Key Challenges | Illustrative Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Incumbents | Systematic integration | Executive sponsorship, Formal governance, Resource commitment | Cultural inertia, Competing priorities, System complexity | Alpha’s comprehensive integration connecting governance, strategy, operations, and performance systems |

| Entrepreneurial | Purpose-driven culture | Mission alignment, Founder commitment, Stakeholder relationships | Resource constraints, Scaling impact, Maintaining values | Epsilon’s challenge maintaining integrated approach while scaling operations |

| Public Sector | Policy-driven change | Political mandate, Stakeholder engagement, Regulatory alignment | Political cycles, Resource constraints, Bureaucratic processes | Zeta’s collaborative approach connecting public policy with private implementation |

| B2C Sectors | Brand-driven initiatives | Consumer pressure, Reputational concerns, Market differentiation | Authenticity perceptions, Value chain complexity, Measurement challenges | Alpha’s focus on consumer-facing sustainability initiatives that built brand equity |

| B2B Sectors | Client and regulation-driven | Client requirements, Industry standards, Efficiency gains | Limited market pressure, Technical complexity, Investment horizons | Beta’s emphasis on compliance and efficiency in the absence of consumer pressure |

| Global Organizations | Centralized strategy with local adaptation | Strong governance, Contextual flexibility, Knowledge transfer | Contextual variation, Competing priorities, Implementation consistency | Gamma’s challenge balancing global standards with local adaptation across diverse markets |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).