Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Sustainability Crisis and Manufacturing Realignment

1.2. From Efficiency to Resistance-Sustainability Nexus

1.3. Conceptual Gaps: Fragmented Integration in OM Theories

1.4. Global Sustainability Crisis and Manufacturing Realignment

- ▪

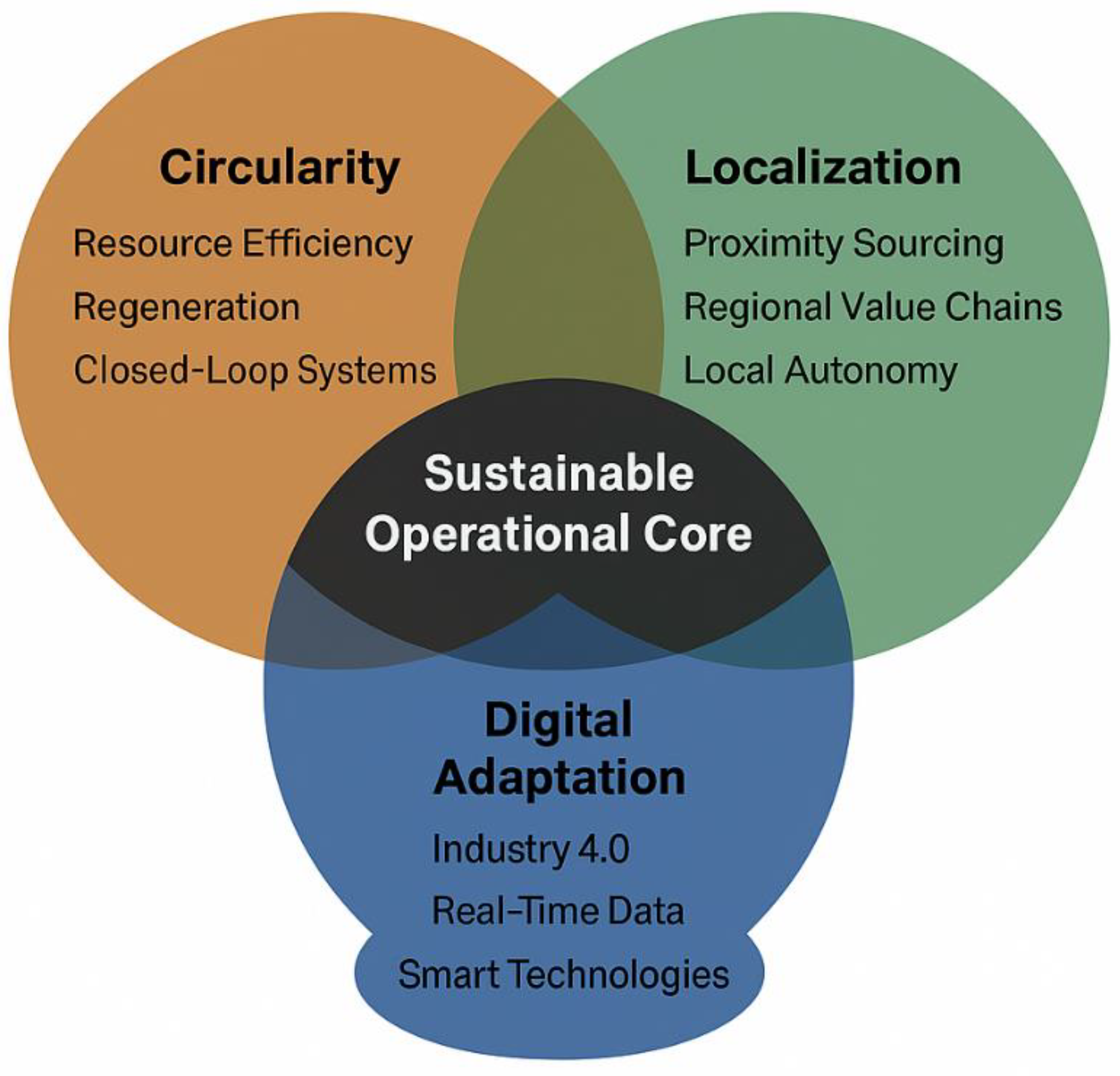

- Circularity – embedding regenerative and closed-loop principles into production and logistics.

- ▪

- Localization – promoting regionalized, proximity-based sourcing and production to enhance adaptability and reduce emissions.

- ▪

- Digital Resilience – utilizing real-time data, predictive analytics, and smart systems to enhance sustainability performance under uncertainty.

- ▪

- It advances a multi-level conceptual framework linking operational design, technological enablers, and sustainability outcomes.

- ▪

- It integrates fragmented theories into a cohesive strategic-operational architecture grounded in systems thinking and sustainability science.

- ▪

- It proposes research propositions for empirical testing, thereby supporting future theory building and cross-disciplinary scholarship.

- ▪

- It aligns directly with the Aims and Scope of Sustainability (MDPI) by addressing technical, environmental, and organizational dimensions of sustainable development through a systems-based operational lens.

1.5. Paper Structure

- ▪

- Section 2 reviews and synthesizes relevant theoretical foundations across sustainability transitions, circular operations, localization strategies, digital enablers, and systems thinking.

- ▪

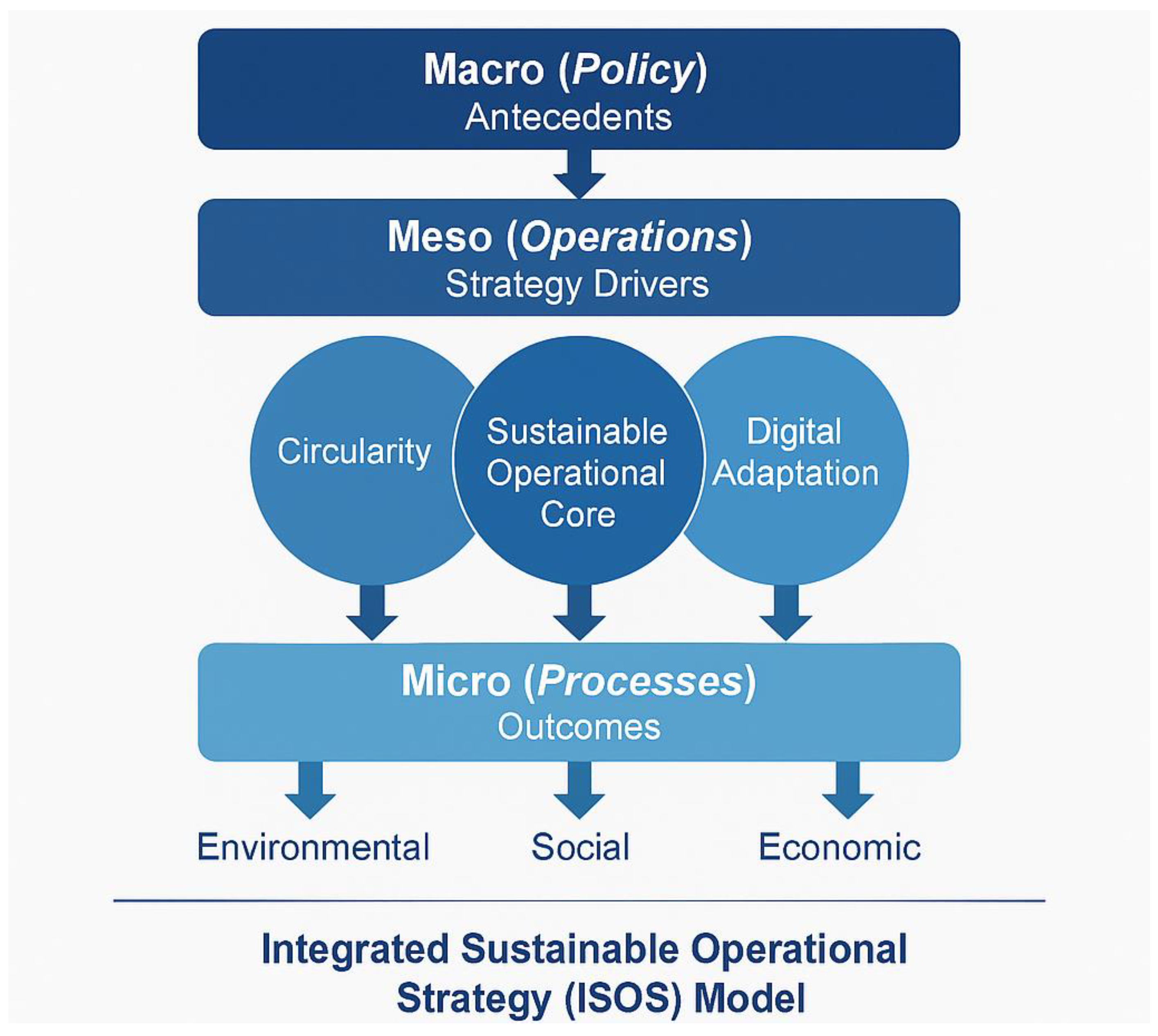

- Section 3 develops the Integrated Sustainable Operational Strategy (ISOS) framework, detailing its conceptual logic, dimensions, and boundaries.

- ▪

- Section 4 elaborates strategic operational domains and discusses their interdependency, drawing implications for design, management, and organizational performance.

- ▪

- Section 5 presents a theoretical discussion, highlighting contributions to operations management, sustainability science, and strategic transformation.

- ▪

- Section 6 offers a research agenda with propositions for empirical validation and cross-sectoral exploration.

- ▪

- Section 7 concludes the paper with final reflections on the future of sustainable operations in the Anthropocene economy.

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Sustainability Transition in Operation Management

2.2. Circular Economy: Systemic Capability and Regenerative Logic

2.3. Localized Operations and Regional Resilience Framework

2.4. Digital Transformation as an Enabler of Sustainability Adaption

2.5. System Thinking and Triple Bottom Line Convergence

- ▪

- Circularity supports Planet through closed-loop material flows and regenerative design.

- ▪

- Localization supports People by enhancing social embeddedness, labor inclusion, and regional equity.

- ▪

- Digital transformation supports Profit by enhancing efficiency, agility, and risk-informed decision-making.

3. Conceptual Framework and Design Logic

3.1. Research Design as Conceptual Contribution

- ▪

- Theory Consolidation: We identify and extract core constructs from the extant literature across sustainability transitions, circular economy, digital operations, and localized resilience. These constructs are not treated as fixed variables but as evolving, context-dependent logics that reflect contemporary shifts in operations.

- ▪

- Thematic Integration: We map conceptual linkages and interdependencies across these domains, highlighting how each contributes unique yet complementary dimensions to sustainable operations. This step moves beyond isolated best practices to uncover systemic patterns and overlaps that enable higher-order synthesis.

- ▪

- Framework Articulation: We develop the Integrated Sustainable Operational Strategy (ISOS) model as a conceptual architecture that captures the dynamic convergence of three strategic domains: Circularity, Localization, and Digital Adaptation.

3.2. Logic of Framework Construction: Antecendents, Drivers, Outcomes

- ▪

- ▪

- Global supply chain fragility, exposed during recent crises (e.g., COVID-19), has revealed the brittleness of long-distance efficiency-driven systems [82].

- ▪

- ▪

- ▪

- ▪

- ▪

- Environmental: Reduction of waste, emissions, and resource extraction through closed-loop systems and real-time energy optimization.

- ▪

- Social: Empowerment of local actors, workforce upskilling, and regional equity through localized operations and adaptive technologies.

- ▪

- Economic: Enhanced value creation, cost resilience, and innovation through regenerative processes and smart operations.

- ▪

- Generalizable across sectors and geographies;

- ▪

- Specific enough to guide operational redesign initiatives; and

- ▪

- Flexible to incorporate emerging technologies and contextual shifts.

3.3. Key Constructs Definitions and Boundaries

3.4. Proposed Multi-Level Model: Macro (Policy) – Meso (Operations) – Micro (Processes)

4. Integrated Operational Strategies for Circular and Adaptive Sustainability

4.1. Operationalizing Circularity: Closed-Loop Design and Reverse Logistics

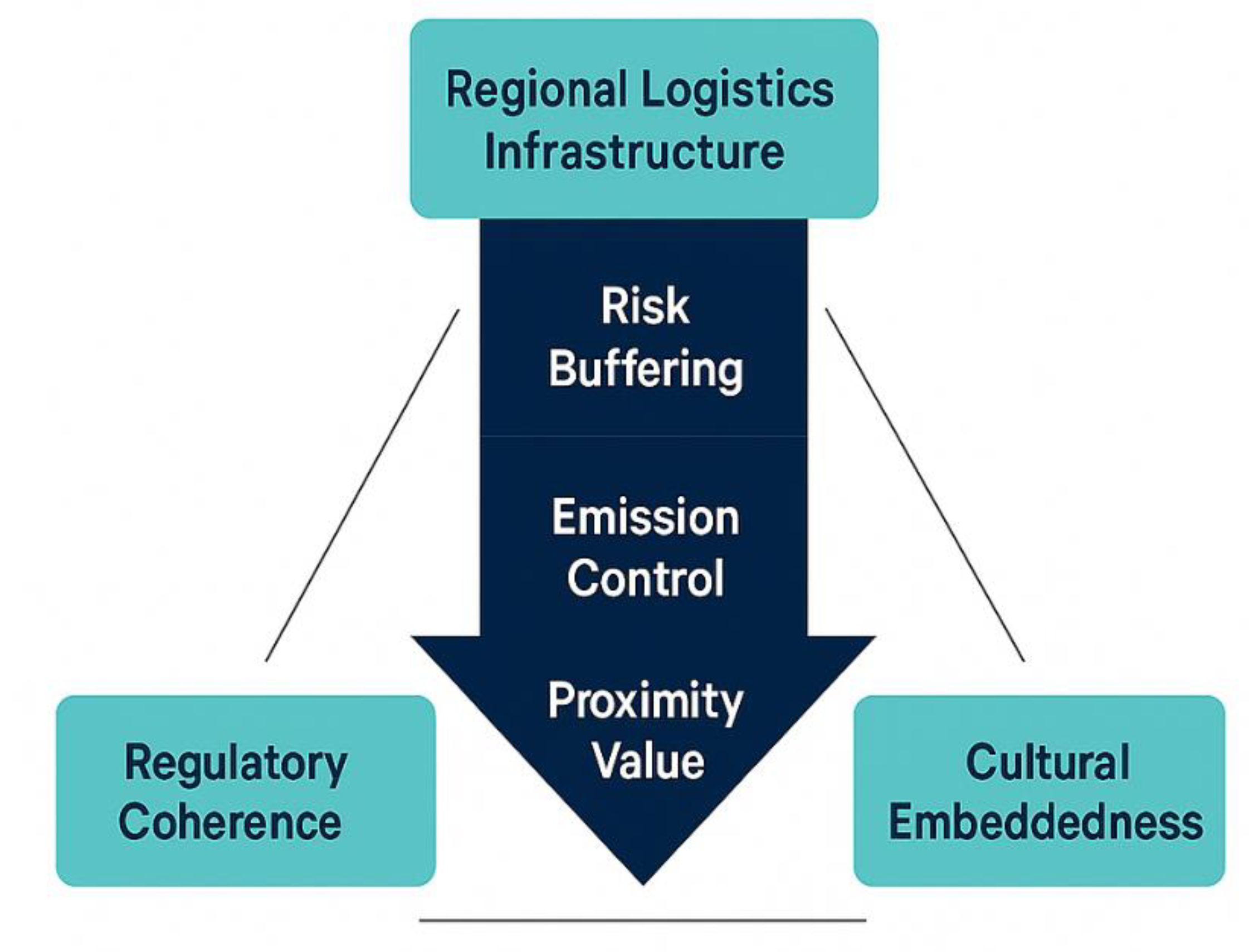

4.2. Localization Strategies: Risk Buffer, Emission Control, and Proximity Value

- ▪

- Risk Buffering: Regional sourcing and nearshoring mitigate supply disruption risks triggered by pandemics, political embargoes, or extreme climate events. By decentralizing production, firms reduce dependence on long-haul logistics and fragile cross-border flows [122].

- ▪

- Emission Control: Reducing transportation distances directly supports Scope 3 emission reduction targets. Local operations also enhance traceability and facilitate alignment with local environmental regulations [123].

- ▪

- Proximity Value: Embedding operations closer to the market enables real-time demand responsiveness, cultural customization, and community engagement, which are increasingly critical for brand differentiation in sustainability-conscious markets.

4.3. Digital Resilience: Real-Time Decisioning and Predictive Monitoring

4.4. Workforce and Process Flexibility for Adaptive Sustainability

- ▪

- Operational continuity during crises (e.g., reassigning production staff to support logistics during supply shocks).

- ▪

- ▪

- Social sustainability, as investment in reskilling, autonomy, and well-being enhances employee retention and organizational citizenship behavior aligned with sustainability goals.

- ▪

- Switch between different product types or production volumes with minimal downtime.

- ▪

- Adapt to alternative materials or energy sources in case of shortages or regulatory constraints.

- ▪

- ▪

- Circular strategies benefit from workers skilled in reuse, disassembly, and remanufacturing, as well as processes that support batch reconfiguration for secondary materials.

- ▪

- Localization is more resilient when local teams are cross-functional and when small-scale production systems are designed for modularity and reallocation.

- ▪

- Digital systems enable flexibility by providing real-time intelligence, but require human adaptability to act on insights with ethical and environmental sensitivity.

4.5. Synthesis: Interdependency and Trade-Off Management

- ▪

- Circularity and Digital Adaptation: The success of circular operations (e.g., reverse logistics, remanufacturing) often hinges on digital traceability (e.g., IoT-enabled product passports), which allows firms to track materials and anticipate reuse opportunities. AI-driven demand forecasting also reduces overproduction, reinforcing circular outcomes [140,141].

- ▪

- Localization and Circularity: Regional sourcing supports circular goals by reducing transportation emissionsand simplifying reverse material flows. Moreover, local knowledge enables context-sensitive circular practices such as community-based recycling and industrial symbiosis [142].

- ▪

- Digital Adaptation and Localization: Digital systems enable real-time local monitoring, allowing agile responses to regional disruptions (e.g., weather events, labor shortages). Cloud platforms and distributed ledgers enhance coordination across decentralized hubs, sustaining performance while maintaining regional autonomy [143,144].

- ▪

- Efficiency vs. Redundancy: Localization may require distributed facilities, which adds cost and may conflict with lean principles. However, this trade-off is strategically justified under conditions of systemic risk (e.g., supply chain disruptions), where redundancy acts as a buffer [145].

- ▪

- ▪

- Standardization vs. Customization: Circularity benefits from modular design and standardization, while localization demands contextual customization. Strategic design must therefore support configurable systems—standardized at the core but customizable at the edge [148].

- ▪

- Cross-functional governance mechanisms to coordinate sustainability decisions across departments and geographies.

- ▪

- Strategic metrics and dashboards that reveal trade-off consequences in real-time.

- ▪

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

5.1. Redefining Operational Excellence in the Anthropocene

- ▪

- Translate global sustainability standards (e.g., SDGs, COP commitments) into locally actionable operational practices.

- ▪

- Customize circular and digital strategies according to regional infrastructure, regulatory regimes, and cultural dynamics.

- ▪

- Harmonize decision-making across geographies without sacrificing contextual sensitivity.

- ▪

- Circular logistics through traceability and predictive analytics.

- ▪

- Resilience through digital twins and real-time monitoring.

- ▪

- Governance innovation, such as smart contracts for sustainable procurement.

- ▪

- Circularity generates economic efficiency while reducing environmental load.

- ▪

- Localization strengthens community resilience and shortens value loops.

- ▪

- Digital adaptation enhances transparency, trust, and accountability across stakeholders.

- ▪

- Build redundancy where fragility is high (e.g., local sourcing buffers against geopolitical shocks).

- ▪

- Enable modularity and configurability in processes and products (e.g., circular design).

- ▪

- Prioritize learning and realignment, supported by real-time data and feedback loops.

5.2. Theoretical Implications for Sustainability Science and Operations Management

- 1.

- Cross-Scalar Integration: From Global Norms to Local Capabilities

- ▪

- Macro-level imperatives (e.g., SDG 9 on infrastructure, SDG 12 on responsible production, and SDG 13 on climate action),

- ▪

- Meso-level organizational strategies (e.g., circular redesign, localization, digital transformation),

- ▪

- Micro-level process capabilities (e.g., predictive monitoring, flexible workflows).

- 2.

- Bridging Technological and Organizational Paradigms

- ▪

- Technological capabilities (e.g., IoT for real-time traceability),

- ▪

- Organizational routines (e.g., cross-functional decision-making),

- ▪

- Cultural and ethical dimensions (e.g., transparency, trust-building).

- 3.

- Reconceptualizing Operational Value: From Efficiency to Regeneration

- ▪

- Circularity as a value amplifier,

- ▪

- Localization as a resilience multiplier,

- ▪

- Digitalization as a transparency and coordination enabler.

- ▪

- Develop multi-level constructs that cut across traditional functional boundaries (e.g., supply chain, product design, HR).

- ▪

- Formulate dynamic capabilities-based theories that incorporate environmental uncertainty, not just market turbulence.

- ▪

- Advance systems-based operational theories grounded in complexity science and interdependence.

- ▪

- Translating abstract sustainability goals into actionable design logics.

- ▪

- Offering a framework for operational experimentation within sustainability transitions.

- ▪

- Encouraging the study of institutional and technical co-evolution—how infrastructure, governance, and operations co-shape one another.

5.3. Managerial and Policy Implications: Strategic Integration over Silos

- ▪

- Global policy agendas with local operational realities,

- ▪

- Technological architectures with organizational routines, and

- ▪

- Short-term efficiency gains with long-term regenerative value creation.

- 1.

- For Managers: Operationalizing Integration at the Strategic Core

- ▪

- Cross-functional Governance: By linking operations, supply chain, IT, HR, and sustainability teams under one decision-making logic, the model encourages collective ownership and strategic agility [163].

- ▪

- Investment Prioritization: The model helps identify high-leverage investment areas where circular practices, digital enablers, and localized resilience reinforce one another—for instance, investing in blockchain for reverse logistics or using predictive analytics to localize inventory buffers.

- ▪

- Integrated Metrics: Moving beyond siloed KPIs (e.g., cost reduction vs. carbon footprint), ISOS promotes triple bottom line metrics that allow trade-off balancing and strategic coherence [164].

- 2.

- For Policymakers: Enabling Systemic Transitions Beyond Compliance

- ▪

- Design Interconnected Incentives: Rather than supporting isolated initiatives (e.g., tax breaks for digitalization or subsidies for recycling), policies should foster integrated innovation ecosystems that link sustainability goals to digital and regional development strategies.

- ▪

- Develop Regional Platforms: Public–private partnerships that enable data sharing, reverse logistics infrastructure, and localized renewable energy systems can act as system-level enablers of the ISOS model [165].

- ▪

- Support Capability Building: Policymakers should invest in workforce reskilling, circular economy education, and local supplier development to build adaptive capacity within regions—thereby reinforcing the meso- and micro-layers of the ISOS framework.

- 3.

- Shared Imperative: Breaking the Trade-off Mentality

- ▪

- Achieve cost efficiency through circular design,

- ▪

- Reduce risk and emissions via localized supply strategies,

- ▪

- Increase agility and transparency through digital enablers.

5.4. Limitations of Current Framework and Boundary Conditions

- (1)

- Theoretical Scope and Abstraction Level

- (2)

- Sectoral and Institutional Variability

- (3)

- Interdependency Management and Trade-off Complexity

- (4)

- Sustainability Value Interpretation

- (5)

- Need for Empirical Grounding and Evolution

6. Future Research Agenda

6.1. Hypotheses for Empirical Validation

6.2. Methodological Paths: Case-Based Modelling, Simulation, System Dynamics

- (1)

- Case-Based Modelling for Contextualization

- ▪

- Rationale: Sustainable strategies are embedded in institutional and cultural contexts. A one-size-fits-all model may misrepresent critical contingencies.

- ▪

- Approach: In-depth comparative case studies across sectors (e.g., manufacturing, agri-food, energy) using methods such as fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) can uncover multiple equifinal pathways to sustainability.

- ▪

- Expected Output: Typologies of implementation strategies across organizational archetypes and regions.

- (2)

- Simulation-Based Design for Scenario Testing

- ▪

- Rationale: Traditional linear models cannot adequately capture feedback loops, delays, and nonlinearity inherent in sustainability transitions.

- ▪

- Approach: Employ agent-based modeling (ABM) or discrete event simulation (DES) to test the ISOS framework under multiple hypothetical scenarios, such as climate regulations or demand surges.

- ▪

- Expected Output: Identification of leverage points, thresholds, and system bottlenecks under varying operational configurations.

- (3)

- System Dynamics for Macro-Meso Integration

- ▪

- Rationale: The ISOS model posits sustainability as a systemic property that evolves over time, not a static KPI.

- ▪

- Approach: System dynamics modeling enables simulation of time-delayed policy effects, resource loops, and behavioral responses across levels.

- ▪

- Expected Output: Dynamic maps of policy-operational alignment and potential unintended consequences from siloed interventions.

6.3. Multi-Stakeholder and Cross-Sector Testing

- ▪

- Justification: Sectors such as food processing, automotive manufacturing, and renewable energy differ in their carbon intensity, supply chain complexity, and public scrutiny. These contextual features shape both strategic intent and implementation feasibility.

- ▪

- Approach: Sector-stratified comparative studies using structured surveys or stakeholder interviews can assess how the ISOS dimensions (circularity, localization, digitalization, flexibility) manifest in practice.

- ▪

- Goal: Identify sector-specific leverage points and common failure modes to improve generalizability of the framework.

- ▪

- Justification: The systemic nature of sustainability requires collaboration beyond firm-centric initiatives. Misalignment between operational goals and stakeholder expectations often leads to implementation gaps or resistance.

- ▪

- Approach: Conduct multi-stakeholder workshops, participatory modeling, or co-design action research to assess how various actors perceive, support, or block components of the ISOS model.

- ▪

- Goal: Surface friction points and synergy zones among stakeholders to inform more inclusive and adaptive implementation strategies.

- ▪

- Justification: Localization is not simply spatial; it is relational and institutional. Local capabilities and legitimacy shape whether sustainability strategies can be embedded effectively.

- ▪

- Approach: Use regional case clusters (e.g., industrial parks, eco-zones) to compare performance trajectories of ISOS adopters under differing local contexts.

- ▪

- Goal: Develop a geo-contextualized implementation map that links local enablers with strategic outcomes.

7. Conclusion

7.1. Summary of Contributions

7.2. Strategic Relevance and Future Orientation

7.3. Final Reflection: Operational Innovation for Sustainability Transitions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| OM | Operations Management |

| CE | Circular Economy |

| TBL | Triple Bottom Line |

| ISOS | Integrated Sustainable Operational Strategy |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises |

| SCM | Supply Chain Management |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

References

- Iea, “Tracking Clean Energy Progress 2023,” https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-progress-2023?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- United Nations, “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- Wang, D.; Li, J.; Meng, W.; Liao, Z.; Yang, S.; Hong, X.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, G. A near-zero carbon emission methanol production through CO2 hydrogenation integrated with renewable hydrogen: Process analysis, modification and evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siamionava, K.; Mitra, S.; Westerman, G. Aligning With Metrics: Differential Impact of IT and Organizational Metrics on Cognitive Coordination in Top Management Teams. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2024, 33, 1875–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Lu, J. Short-term resilience assessment of the global liner shipping network: A case study of COVID-19. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. A dynamic model of the supply chain resilience cycle: concept mapping using the Cynefin framework. Oper. Manag. Res. 2024, 17, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abba, K.; Ring, A.; Lloyd, P.; de Cuevas, R.A.; Hassan, S.; Goodall, M.; Clarke, P.; Hanna, K.; Ahmed, S.; Allen, G.; et al. Community groups, organisations, and employers respond to the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic: A story of resilience and continued vulnerability. BMC Public Heal. 2025, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeler, D.G.; Eyre, H.A.; Berk, M.; Allen, C.R.; Hynes, W.; Linkov, I. Adaptation, Transformation and Resilience in Healthcare Comment on "Government Actions and Their Relation to Resilience in Healthcare During the COVID-19 Pandemic in New South Wales, Australia and Ontario, Canada". Int. J. Heal. Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 1949–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynes, W.; Kirman, A.; Latini, C.; Luzzati, D. A SYSTEMIC APPROACH TO ECONOMIC RESILIENCE. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Yang and Y.-S. Hwang, “The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility and an Emphasis on the Sustainability of the Environment on Small and Medium-Sized Businesses’ Ecological Sustainability: The Role of Green Capabilities as a Mediator,” Journal of Ecohumanism, vol. 3, no. 7, pp. 1555– 1568, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Faeni, D.P.; Oktaviani, R.F.; Riyadh, H.A.; Faeni, R.P.; Beshr, B.A.H. Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Reducing Carbon Emissions for Sustainable Practices. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2025, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giovanni, P.; Folgiero, P. Strategies for the Circular EconomyCircular districts and networks. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R.; Singh, B.; Agrawal, A.K.; Chatterjee, S.; Gupta, S.; Mangla, S.K. A TOE-DCV approach to green supply chain adoption for sustainable operations in the semiconductor industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, D.; Zerbian, T.; Cuevas, S.; Moragues-Faus, A.M. Blurred powers, multiple agencies, and discontinuous temporalities. A multi-level perspective on bottom-up innovation in agri-food policies. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2025, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Qamruzzaman; Sharmin, S. S.; Karim, S. Bridging Environmental Sustainability and Organizational Performance: The Role of Green Supply Chain Management in the Manufacturing Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukharta, O.F.; Sauvée, L.; Pena-Fabri, F.; Chico-Santamarta, L.; Navas-Gracia, L.M. Disentangling metropolis-city relationships in the governance of sustainability transitions: An in-depth exploration of the case of Rouen, France. Cities 2025, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, T. Policy coherence of low-emission transport transition in the Global South: The case of Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2025, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, E. Developing Dynamic and Sustainable Supply Chains to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, United States, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, R.; Lister, N.; Dale, A.; Careri, S. Wildlife crossing database platform: A transdisciplinary approach to developing a tool for landscape connectivity planning and public engagement. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Sharma, Y.; Chauhan, A.; Parewa, B.; Rai, P.; Naik, N. Investigation of green supply chain management practices and sustainability in Indian manufacturing enterprises using a structural equation modelling approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerland, R.; Solbu, G.; Hansen, K.; Nilsen, H.R. Transforming local governance: using system leverage points to conceptualize sustainability transformations. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Xin, B.; Xu, M.; Wu, S. Optimal carbon–neutral strategies in the healthcare system: A three-stage Stackelberg game model. Transp. Res. Part E: Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Xin, B.; Xu, M.; Wu, S. Optimal operational and carbon neutrality strategies for private hospitals: A multi-objective approach considering patient flow. Transp. Res. Part E: Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Chen, X. S. Chen, X. Liang, Y. Liu, X. Li, X. Jin, and Z. Du, “Customized large-scale model for human-AI collaborative operation and maintenance management of building energy systems,” Appl Energy, vol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoli, J.S.; Kodama, T.K.; Nagano, M.S.; Burnquist, H.L. Advancing Circular Economy: G20 Nations’ Path Towards 12th Sustainable Development Goal. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D.; Tu, Y. Supply chain viability in the post-COVID era. Omega 2025, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiara, A.R.; Tjahjono, B.; Beltran, M.; Rayns, F.; Longhurst, P. Leveraging Resource Management and Duality Theories to Strengthen Circular Economy Practices in the Waste-to-Energy Industry. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2025, 34, 4642–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruczek, M.; Jąderko-Skubis, K.; Markowska, M.; Zgórska, A.; Białowąs, M. Circularity potential identification for new bio-materials using material flow analysis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2025, 982, 179649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Pala, M.O.; Sezer, M.D.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A. Drivers of implementing Big Data Analytics in food supply chains for transition to a circular economy and sustainable operations management. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2021, 38, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Kautish, P.; Rashid; Joshi, Y. ; Iftikhar, Y. Digitalization in the circular economy: Synergistic impact of big data analytics, green internet of things, and ambidextrous green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolai, B.; Laschi, C.; Margheri, L. Environmental Intelligence and Ecorobotics: Toward Environmental Sustainability. Annu. Rev. Control. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 8, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravasio, P. Corporate Governance and Corporate Responsibility: The Importance of Values, Leadership, and Accountability, in Driving the Textile Industry Towards a Sustainable Future. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, S.; Backes, J.G.; Traverso, M.; Sonnemann, G.; Cucurachi, S.; Guinée, J.B.; Schaubroeck, T.; Finkbeiner, M.; Leroy-Parmentier, N.; Ugaya, C.; et al. Principles for the application of life cycle sustainability assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1900–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeilerbauer, L.; Fischer, J.; Fazeni-Fraisl, K.; Mager, M.; Lindorfer, J.; Paulik, C. Life cycle assessment of mechanical recycling of low-density polyethylene into film products – towards the need for life cycle thinking in product design. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Z.S.; Davletshin, M.; Rogers, D.S.; Chen, H.; Korde, R.Y.; Greve, C. Unveiling the Structure of Reverse Supply Networks: An Empirical Exploration. J. Bus. Logist. 2025, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Tan, B.Q. Multi-echelon reverse logistics network design in the context of circular economy: a Hong Kong case study. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, L.; Saraceni, A. Ranking model to measure energy efficiency for warehouse operations sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahenkan, A.; Boon, E.; Nordjo, E.; Akalibey, S. Advancing the transition to circular economy in Ghana: Prospects and challenges. Environ. Dev. 2025, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, D.; Reike, D.; Bening, C.R. Analyzing policy mixes for the circular economy transition: The case of recycled plastics in electronics. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2025, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, S.A.; Warsi, S.S. Exploring the Synergy between Sustainability and Resilience in Supply Chains under Stochastic Demand Conditions and Network Disruptions. Results Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantadej, K.; Kotcharin, S. Navigating liquidity in turbulent waters: The impact of global supply chain pressures on maritime working capital management strategies. Res. Transp. Econ. 2025, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Qian, J.; Chen, J.; Yu, Q.; You, L.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Xiao, P.; Jiang, J. Potential decarbonization for balancing local and non-local perishable food supply in megacities. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlström, M.; Colpier, U.; Josefsson, A.; Lantz, M.; Lindgren, M. Requested policy to Support Market Transition – Experiences from a Swedish Electrified Logistics System Demonstrator, vol. Part F383. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yavari, M.; Mihankhah, S.; Jozani, S.M. Assessing cap-and-trade regulation's impact on dual-channel green supply chains under disruption. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhen, Z.; Shi, H.; Zhao, M. Network invulnerability modeling of daily necessity supply based on cascading failure considering emergencies and dynamic demands. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissimi, M.C.; Bin Hameed, H.; Creazza, A. Circular economy: The future nexus for sustainable and resilient supply chains? Sustain. Futur. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Liu et al., “Research on the circular economy model of co-disposal of county-level domestic waste and rural solid waste | 县域生活垃圾协同处置农村固废循环经济模式研究,” Journal of Environmental Engineering Technology, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Moayedfar, S.; Mohebbi, H.; Pour, N.M.; Sharifi, A.; Zeng, Z. Developing a localized resilience assessment framework for historical districts: A case study of Yazd, Iran. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0317088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, I.; Amin, H.; Ozturk, O.; Zaman, A.; Sever, S.D.; Tok, E. Digital, localised and human-centred design makerspaces: nurturing skills, values and global citizenship for sustainability. Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orošnjak, M.; Brkljač, N.; Ristić, K. Fostering cleaner production through the adoption of sustainable maintenance: An umbrella review with a questionnaire-based survey analysis. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Torres, G.J.; López-Naranjo, A.L.; Larrea-Cuadrado, P.L.; Mazón-Fierro, G. Transformation of the Dairy Supply Chain Through Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenal, H.; Reddy, C.K.K.; Atthar, S.; Lippert, K. Revolutionizing sustainable supply chain management in healthcare via AIoMT. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.A.; Patra, F.; Ghosh, T.; Mahnot, N.K.; Dutta, H.; Duary, R.K. Advancing Food Systems with Industry 5.0: A Systematic Review of Smart Technologies, Sustainability, and Resource Optimization. Sustain. Futur. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmazi, K.; Elmazi, D.; Lerga, J. Digital Twin-driven federated learning and reinforcement learning-based offloading for energy-efficient distributed intelligence in IoT networks. Internet Things 2025, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, S.; Jethava, G. Elevating manufacturing excellence with multilevel optimization in smart factory cloud computing using hybrid model. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Alshaikh, V. R. Alshaikh, V. Ahmed, and Z. Bahroun, “BLOCKCHAIN TECHNOLOGY FOR TRACEABILITY OF HAZARDOUS MATERIAL IN SEAPORTS,” in Proceedings of International Conference on Computers and Industrial Engineering CIE, 2023, pp. 1366–1375.

- Abdessadak, A.; Ghennioui, H.; Thirion-Moreau, N.; Elbhiri, B.; Abraim, M.; Merzouk, S. Digital twin technology and artificial intelligence in energy transition: A comprehensive systematic review of applications. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 5196–5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabuncu, Ö.; Bilgehan, B. Human-Centric IoT-Driven Digital Twins in Predictive Maintenance for Optimizing Industry 5.0. J. Metaverse 2025, 5, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharaki, A.; Vafeiadis, T.; Kolokas, N.; Vaxevani, A.; Xu, Y.; Peschl, M.; Ioannidis, D.; Tzovaras, D. RECLAIM: Toward a New Era of Refurbishment and Remanufacturing of Industrial Equipment. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Kohtamäki, M. Artificial intelligence enabling circular business model innovation in digital servitization: Conceptualizing dynamic capabilities, AI capacities, business models and effects. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlutova, I.; Spilbergs, A.; Romanova, I.; Kuzmina, J.; Fomins, A.; Verdenhofs, A.; Natrins, A. The role of green digital investments in promoting sustainable development goals and green energy consumption. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaitouni, S.I.; Romani, Z.; Jamil, A.; Ahachad, M. Zero Carbon Urban Buildings (ZCUBs) in the era of climate change, digital transformation and energy transition: a scoping review from 2000 to 2024. Build. Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Lam, S.S.W.; Chan, S.L.; Xu, Y.; Ge, Y.; Gui, G.K.T.; Tan, H.K. Strategizing towards the future hospital: a systems thinking approach. Heal. Res. Policy Syst. 2025, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAvoy, S.; Toth-Peter, A.; Jagdish, N.; Nguyen, B.H.; Arnott, A.; Nissen, L. Timely access to specialist outpatient care: can applying systems thinking unblock our waiting lists? BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, R.; Munz, J.; Braun, J.; Frank, M. Site-specific N-application in small-scale arable farming in Germany—Evaluation of trade-offs and synergies of ecological and economic parameters based on a case study. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, N.; Saraswat, E.; Kabia, A.; Sharma, R. “The Role of IoT in Circular Business Models: Opportunities and Challenges for Sustainable Innovation,” in Proceedings of International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics Ic3i 2024, 2024, pp. 584–589. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, D. “Smart Cities Waste Minimization, Remanufacturing, Reuse, and Recycling Solutions Using IoT and ML,” in Proceedings International Conference on Computing Power and Communication Technologies Ic2pct 2024, 2024, pp. 1546–1552. [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, K.S.; Balakrishnan, G.; Kumar, S.S.; Raja, L.; Vijayalakshmi, A. Embracing circular economy principles for sustainable green supply chain management in manufacturing industries. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fasolino, N.G.; Pellegrini, E.; Raggi, M.; Viaggi, D. Dynamics in action: Exploring economic impacts of drought through a systemic approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 380, 125111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Collste et al., “Polycrisis patterns: applying system archetypes to crisis interactions,”. Global Sustainability 2025, 8. [CrossRef]

- Botwright, S.; Teerawattananon, Y.; Yongphiphatwong, N.; Phannajit, J.; Chavarina, K.K.; Sutawong, J.; Nguyen, L.K.N. Understanding healthcare demand and supply through causal loop diagrams and system archetypes: policy implications for kidney replacement therapy in Thailand. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.T.M. Aesthetic Leadership in Nursing: A Theoretical Proposal for Rehumanizing Care Delivery. Nurs. Inq. 2025, 32, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, M.; Wijermans, N.; González-Mon, B.; Lindkvist, E.; Orach, K.; Prawitz, H.; Martin, R.; Martínez-Peña, R.; Pellowe, K.E.; Sanga, U. Navigating the space between empirics and theory – Empirically stylized modelling for theorising social-ecological phenomena. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Lewis, A.; Coles, R. Emancipatory entrepreneurship in postcolonial economies: The clash of institutional systems in the Kejetia marketplace. J. Bus. Ventur. 2025, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headen, I. Structural Racism, Geographies of Opportunity, and Maternal Health Inequities: A Dynamic Conceptual Framework. J. Racial Ethn. Heal. Disparities 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, M.; Krishnan, S. Investigating resistance to IT projects: a conceptual model from a meta-synthesis approach. Inf. Technol. People, 2024; ahead-of-p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, A.; Chen, P.-Y.; Oh, W.; Xu, S.X.; Sarker, S. On Crafting Effective Theoretical Contributions for Empirical Papers in Economics of Information Systems: Some Editorial Reflections. Inf. Syst. Res. 2024, 35, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Hamidavi Nasab, H. Y. Hamidavi Nasab, H. Zandhessami, M. Amiri, A. Keyghobadi, and K. Fathi Hafshejani, “Identifying Effective Factors of Organizational Resilience: A Meta-Synthesis Study,” International Journal of Research in Industrial Engineering, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 177–196. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werrel, M.; Klar, M.; Aurich, J.C. Circularity assessment of product-service systems using system dynamics modeling. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, D.; M, S.; Martin, H.; Raman, R. Aligning net zero carbon-built environments with sustainable development goals: Topic modelling approach to integrating technologies and policies. Build. Environ. 2025, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Li, M. M. Rahman, N. Haneklaus, S. Li, and Y. Zhou, “Green transition initiatives to reduce environmental degradation: Adaptation, mitigation and synergistic effects,”. Environ Impact Assess Rev, 2025; 115. [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Wang, X. Brittleness Evolution Model of the Supply Chain Network Based on Adaptive Agent Graph Theory under the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideri, L. The relationship between corporate environmental, social, governance issues and corporate sustainability in the financial sector: A managerial perspective. Bus. Strat. Dev. 2023, 6, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavio, M.F.R.; Setiawan, D.; Aryani, Y.A.; Arifin, T. The relationship between corporate governance and sustainability performance: the moderating role of public attention. Asian Rev. Account. 2025; ahead-of-p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmakinde, O.E.; Sher, W.; Egbelakin, T. Circular economy pillars: a semi-systematic review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 899–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Kobir, H.; Faludi, J.; Zhao, F. Driving additive manufacturing towards circular economy: State-of-the-art and future research directions. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 124, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissimi, M.C.; Bin Hameed, H.; Creazza, A. Circular economy: The future nexus for sustainable and resilient supply chains? Sustain. Futur. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.; Barata, J. Digital twin-enabled regional food supply chain: A review and research agenda. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrakoetxea, N.G.; Uquijo, B.S.; López, I.P.; Barruetabeña, J.G.; Bringas, P.G. Enhancing Real-Time Processing in Industry 4.0 Through the Paradigm of Edge Computing. Mathematics 2024, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jeong, J. Domain-Specific Manufacturing Analytics Framework: An Integrated Architecture with Retrieval-Augmented Generation and Ollama-Based Models for Manufacturing Execution Systems Environments. Processes 2025, 13, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, A. Theories of Society in Historical Context(s): Enlisting Intellectual and Conceptual History. Society 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Jia, J. K. Jia, J. Zhao, and H. Fu, “Dealing with Challenges of Uncertainty: Theoretical Definition of Agile Governance on Algorithms | 应对不确定性挑战:算法敏捷治理的理论界定,” Documentation Information and Knowledge, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 35–44. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccari, V.; Mancini, F.; Rogier, G. State of the art of the literature on definitions of self-criticism: a meta-review. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1239696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purushothaman, R.; Alamelu, R.; Selvabaskar, S.; Sudha, M. Theories, techniques and strategies of sustainable circular economy: a systematic literature review. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorthuis, J.; Gijbels, C. A Fair Accord: Cradle to Cradle as a Design Theory Measured against John Rawls’ Theory of Justice and Immanuel Kant’s Categorical Imperative. Sustainability 2010, 2, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regional Resilience: Theoretical Basics of the Question. Econ. Policy 2018, 13, 164–187. [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, J.-P.; Murphy, E.; Scott, M. Developing a holistic ‘vulnerability-resilience’ model for local and regional development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2330–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Medeiros, “Strategic-Based Regional Development: Towards a theory of everything for regional development?,” European Journal of Spatial Development, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 2022; 26. [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Nieto, A. Reconsidering development in left-behind places and a critical discussion of place-based strategies. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B, Hum. Geogr. 2025; 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, K.; Gruezmacher, M.; Beunen, R. Shock and Conflict in Social-Ecological Systems: Implications for Environmental Governance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.; Pinho, P. In search of coastal landscape governance: a review of its conceptualisation, operationalisation and research needs. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 2093–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, S.; Alarcon, C. Questioning the Concepts of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and Industry 4.0 When Describing Modernization as a Sequential Framework. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Hughes, M.; Hughes, P.; Hodgkinson, I. Digital twin, digital thread, and digital mindset in enabling digital transformation: A socio-technical systems perspective. Technovation 2025, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.C.; Challenger, R.; Jayewardene, D.N.; Clegg, C.W. Advancing socio-technical systems thinking: A call for bravery. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, S.; Ashton, M. Antecedents and outcomes of artificial intelligence adoption and application in the workplace: the socio-technical system theory perspective. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 36, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuermer, M.; Abu-Tayeh, G.; Myrach, T. Digital sustainability: basic conditions for sustainable digital artifacts and their ecosystems. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 12, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Khan, A. Digital sustainability: Dimension exploration and scale development. Acta Psychol. 2025, 256, 105028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M.; Hashem, G. Absorptive capacity and green innovation adoption in SMEs: The mediating effects of sustainable organisational capabilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffernicht, M.F.G.; López-Astorga, M.; Rojas-Barahona, C.A.; Castillo, R.D. Employing a Mental Model Framework to Explore Systems Thinking. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qudrat-Ullah, H. Navigating Complexity; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- F. W. Geels, Advanced introduction to sustainability transitions. 2024.

- Geels, F.W.; Locatelli, G. Broadening project studies to address sustainability transitions: Conceptual suggestions and crossovers with socio-technical transitions research. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2024, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbi, L.; Twinomurinzi, H. SMME readiness framework for smart manufacturing adoption using critical realism: Knowledge and construction phase. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H. Entrepreneurship strategy, natural resources management and sustainable performance: A study of an emerging market. Resour. Policy 2023, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colloff, M.J.; Butler, J.R.; Burke, N.; Morley, J.; van Kerkhoff, L.; Hilly, Z.; Makini-Purcell, R.B.; Namo, J.; Barua, R.; Michie, K.; et al. Cyclones and skinny dolphins: adaptation pathways for Pacific communities under rapid global change. Clim. Dev. 2024, 16, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, G.; Mooney, M.; Porat-Dahlerbruch, J.; Cahir, K.; Ellen, M.; Spinewine, A.; Taylor, N.; Laritz, R.; Bourbeau-Allard, È.; Grimshaw, J.M. Advancing the selection of implementation science theories, models, and frameworks: a scoping review and the development of the SELECT-IT meta-framework. Implement. Sci. 2025, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashad, A.; Rogers, H.; Srivastava, M. Pay-per-use business models as a driver for additive manufacturing adoption: supply chain implications. Supply Chain Forum: Int. J. 2025; 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekara, L.; Robb, D.J. Optimisation of retailer take-back of low and medium-value products for a circular economy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasaklis, T.K.; Casino, F.; Patsakis, C. A traceability and auditing framework for electronic equipment reverse logistics based on blockchain: the case of mobile phones. 2020 11th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications (IISA). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, GreeceDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–7.

- Rodríguez, I.C.; Pérez, A.E.; Boudaoud, H. A multi-objective model for sustainable reverse logistics design for end-of-life tires under a regulatory framework: A Chilean case study. 2023 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, SpainDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Kosek, W.; Woźniak, W.; Chamier-Gliszczynski, N.; Staniuk, W. Offshore Wind Farm Supply Chains and Regional Development: The Role of Ports in Economic and Logistical Growth in the Central Baltic Region. Energies 2025, 18, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Kilic, K.; Kozliakov, G.; Marin, D. Global value chains in a world of uncertainty and automation. J. Int. Econ. 2025, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-H.; Liang, H.; Matos, P. Leviathan Inc. and Corporate Environmental Engagement. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 7719–7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, A.; Onyemere, I. Sustainable supply chain practices as catalyst for energy poverty alleviation in developing countries: a necessary condition analysis. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senarak, C. Toward sustainability and digital resilience: A circular economy cybersecurity framework for seaports. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, H.J.; Al Asbahi, R.; Alzariqi, A.W.; Al Qada, D.R.; Bujuk, A.; Nawfal, M.A.; Tareen, M. Industrial IoT-based submetering solution for real-time energy monitoring. Discov. Internet Things 2025, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, H.; Sharma, G.; Nishad, D.K.; Khalid, S. Advanced queueing and scheduling techniques in cloud computing using AI-based model order reduction. Discov. Comput. 2025, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Lu, Q.; Ghamat, S.; Cai, H.H. Blockchain adoption and coordination strategies for green supply chains considering consumer privacy concern. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 323, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyan, S. An optimization-based analytics model for sustainable and blockchain-enabled supply chains in uncertain environments. Supply Chain Anal. 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromwell, J.; Turkson, C.; Dora, M.; Yamoah, F.A. Digital technologies for traceability and transparency in the global fish supply chains: A systematic review and future directions. Mar. Policy 2025, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhu, J.; Luo, J.; Yi, C.; Zhu, B. Breaking Triopoly to Achieve Sustainable Smart Digital Infrastructure Based on Open-Source Diffusion Using Government–Platform–User Evolutionary Game. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, S.B.; Abhyankar, G.J.; Kirkire, M.S.; Agrawal, R. Modeling barriers to adoption of digitization in supply chains using FTOPSIS and its impact on sustainability TBL. Benchmarking: Int. J. 2023; 332–368ahead-of-p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, A.; et al. , “Swedish manufacturing practices towards a sustainability transition in industry 4. 0: A resilience perspective, 2021., ” in Proceedings of the ASME 2021 16th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference Msec 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Hans, R. From Code to Sustainability: The Impact of Computer Science in Advancing Sustainable Development; 2025; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Marzi and M. Balzano, “Artificial intelligence and the reconfiguration of NPD Teams: Adaptability and skill differentiation in sustainable product innovation,” Technovation, vol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tolmeijer, S.; Christen, M.; Kandul, S.; Kneer, M.; Bernstein, A. “Capable but Amoral? Comparing AI and Human Expert Collaboration in Ethical Decision Making,” in Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Proceedings, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liao, Z.; Hong, X.; Liu, S. Process reconfiguration for the production of 1, 4-butanediol integrating coal with off-grid renewable electricity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wu, B.; Liao, Z.; Hong, X.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, D. Reconfiguration of acid gas removal process matching the integration of coal chemical industry with green hydrogen. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ouyang, K.; Jing, P. Dynamic interplay of energy uncertainty, supply chain disruption, and digital transformation on China's renewable energy stocks. Energy Econ. 2024, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wang, H.; Thwin, M. A machine learning technique for optimizing load demand prediction within air conditioning systems utilizing GRU/IASO model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Peng, Y.; Su, L. Logistics demand prediction using fuzzy support vector regression machine based on Adam optimization. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenck, C.; Pfendtner-Heise, J.; von Wehrden, H. Unveiling local knowledge: a case study on inner development and sustainable transformation in rural areas. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y. Blockchain-based information sharing and supply and demand matching cloud platform for automotive manufacturing supply chain. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2024, 125, 687–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrouk, K.M.; Rasappan, P.; Bhutani, P.; Mittal, S.; Nisha, A.S.A.; Konduru, R.M. Development of Heuristic Strategy With Hybrid Encryption for Energy Efficient and Secure Data Storage Scheme in Blockchain-Based Mobile Edge Computing. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2025, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, K. Arms Spending and War Casualties: Understanding the Strategic Trade-Offs in Warfare. Def. Peace Econ. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, U.; Sargeant, H. When Should Algorithms Resign? A Proposal for AI Governance. Computer 2024, 57, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scantamburlo, T.; Baumann, J.; Heitz, C. On prediction-modelers and decision-makers: why fairness requires more than a fair prediction model. AI Soc. 2024, 40, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Bijl-Brouwer, M.; Price, R.A. An adaptive and strategic human-centred design approach to shaping pandemic design education that promotes wellbeing. Strat. Des. Res. J. 2021, 14, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Li, Z. Multi-scenario analysis of green water resource efficiency under carbon emission constraints in the Chengdu-Chongqing urban agglomeration, China: A system dynamics approach. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, M. Production, investment and financial plan for a "natural gas+" integrated energy enterprise: An assessment using system dynamics and multi-objective optimization model. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 1859–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massagony, A.; Pandit, R.; White, B. Political economy of energy policy in Indonesia towards net zero emissions by 2060. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamasiga, P.; Onyeaka, H.; Bakwena, M.; Ouassou, E.H. Beyond compliance: evaluating the role of environmental, social and governance disclosures in enhancing firm value and performance. SN Bus. Econ. 2024, 4, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caringal-Go, J.F.; Villaluz, V.C.; Teng-Calleja, M.; Años-Ordoña, A.K.; Ocampo, J. Beyond CSR – Building a Culture of Sustainability in Philippine Organizations. Int. Perspect. Psychol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janböcke, S.; Zajitschek, S. Anticipation Next: System-Sensitive Technology Development and Integration in Work Contexts. Information 2021, 12, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wautelet, Y.; Rouget, X. Circulise, a model-driven framework to build and align socio-technical systems for the twin transition: Fanyatu’s case of sustainability in reforestation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M.; Juliao, J. “Impacts of Industry 4.0 on Operations Management: Challenges for Operations Strategy,” in ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 2021, pp. 57–61. [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy, R.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Ali, S.M.; Priyanka, R. Improving organizational performance: leveraging the synergy between Industry 4.0 and Lean Six Sigma to build resilient manufacturing operations. OPSEARCH 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumsisse, I.; Benhadou, M.; Haddout, A. Study of the impact of Industry 5.0 technologies on operational excellence: Insights into agility, innovation, and sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2025, 8, 1322–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japa, R.S.L.; Tostado-Véliz, M.; Ogáyar, B.; Jurado, F. A tri-level model for optimal management of active distribution networks enabling two-layer local markets. Appl. Energy 2024, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Osberg, G. Transformative climate policy mainstreaming – engaging the political and the personal. Glob. Sustain. 2022, 5, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.M.; Hassler, M. Re-Thinking Knowledge in Community-Supported Agriculture to Achieve Transformational Change towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barış, B.; Marselis, S.; Ros, G.; van Doorn, A.; Erisman, J. Towards sustainable agriculture: A blueprint for European KPI-based farm-level assessment. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghami, S.A. The Role of Integrated Governance Principles in the Fight Against Corruption: A Configurational Analysis. Public Adm. Dev. 2025, 45, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, Z.; Xue, B.; Zhao, D.; Sun, X.; Wang, W. Formalizing an integrated metric system measuring performance of urban sustainability: Evidence from China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Cui, T. Facilitating inter-municipal collaboration through mandated collaborative platform: evidence from regional environmental protection in China. Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 26, 1684–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferràs-Hernández, X.; Nylund, P.A.; Brem, A. The Emergence of Dominant Designs in Artificial Intelligence. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2023, 65, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambi, P.D.R.; Batatana, M.L.D.; Appiah, M.; Tetteh, D. Governance, institutions, and climate change resilience in Sub-Saharan Africa: assessing the threshold effects. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1352344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittri, H.; Godawatte, G.A.G.R.; Esangbedo, O.P.; Antwi-Afari, P.; Bao, Z. Exploring Barriers to the Adoption of Digital Technologies for Circular Economy Practices in the Construction Industry in Developing Countries: A Case of Ghana. Buildings 2025, 15, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, Z. Y. Sun, Z. San, C. Xu, and H. Davey, “The Nexus of Managerial Myopia and Transparency in ESG Information: Evidence From the Textual Analysis of ESG Disclosures,” Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag, May 2025. [CrossRef]

| Industry Sector | Circular Strategy Focus | Strategic Function |

| Automotive | Remanufacturing & Parts Recovery | Reduces raw material demand; supports modular product innovation |

| Consumer Electronics | Design for Disassembly & E-Waste Take-Back | Minimizes toxic landfill impact; enables secondary market channels |

| Apparel & Fashion | Recycled Materials & Product-as-a-Service | Builds brand legitimacy; enables recurring revenue models |

| Food & Beverage | Bio-packaging & Organic Waste Loops | Reduces landfill fees; appeals to green-conscious consumers |

| Pharmaceuticals | Reverse Distribution & Expiry Management | Improves inventory efficiency; aligns with health safety compliance |

| Proposition | Underlying Logic | Suggested Empirical Design |

| P1. The integration of circularity practices positively affects sustainable operational performance, mediated by reverse logistics capabilities. | Closed-loop design requires enabling logistics structures to realize sustainability outcomes. | Structural Equation Modeling (SEM); mediation analysis. |

| P2. The effectiveness of localization strategies in enhancing resilience is moderated by the level of institutional coordination at the regional level. | Policy coherence and regional governance influence localization’s impact. | Multi-group regression analysis; hierarchical linear modeling. |

| P3. The relationship between digital adaptation and sustainability performance is mediated by real-time data utilization. | The impact of IoT and AI on operations depends on effective data decisioning. | Mediation test using PROCESS macro or PLS-SEM. |

| P4. Workforce flexibility strengthens the relationship between circularity and operational adaptability. | Human agility enhances the responsiveness of circular systems to disruption. | Moderation analysis; interaction terms in regression. |

| P5. Simultaneous pursuit of circularity, localization, and digitalization leads to superior sustainability outcomes, moderated by organizational integration capacity. | Synergistic strategies require internal capability to manage trade-offs. | Moderated mediation or configurational analysis (e.g., fsQCA). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).