1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Problem Statement

The manufacturing sector remains one of the largest contributors to global environmental degradation, consuming vast quantities of raw materials and generating significant greenhouse gas emissions [

1,

2]. The prevailing linear production model—characterized by the „take–make–dispose” paradigm—has proven unsustainable in the face of escalating ecological crises and increasing resource scarcity [

3]. In this linear logic, products are designed for obsolescence, materials are discarded rather than reused, and value is extracted without regard for systemic consequences.

To address these concerns, the circular economy (CE) has emerged as a regenerative alternative. CE principles such as reduce, reuse, recycle, and regenerate offer a vision for sustainable industrial systems that extend product life cycles and revalorize waste as a resource [

4,

5,

6]. However, despite the growing popularity of circular discourse among firms and policymakers, its practical implementation within operational processes remains limited and fragmented. Many organizations engage with circularity symbolically—through CSR reporting or pilot projects—without embedding it into core production routines [

7,

8].

Without a systematic operational transformation, the promise of circularity risks becoming superficial. Operational sustainability cannot be achieved by design or supply chain adjustments alone; it requires reconfiguring how manufacturing activities are structured, resourced, and governed [

9]. This paper responds to that critical need.

1.2. Research Gap and Motivation

While circular economy frameworks are well-documented in the literature, their integration into operations management (OM) remains underdeveloped [

10,

11]. Existing research often emphasizes product eco-design, supply chain reconfiguration, or macroeconomic policy, yet fails to articulate how circular principles can be translated into actionable routines within the production floor [

12,

13]. A limited number of studies have addressed this gap by proposing typologies or maturity models, but few provide a systems-oriented, operations-specific conceptual model tailored to the realities of manufacturing firms [

14].

This conceptual void is especially pressing given the current technological transition. Industry 4.0, digital twins, and real-time analytics offer new possibilities for circular implementation, yet these enablers are not consistently integrated with operations strategy [

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, cultural and organizational barriers—such as resistance to change, lack of internal alignment, and siloed sustainability initiatives—further complicate circular adoption at the operational level [

18].

To move beyond fragmented initiatives, the field requires a comprehensive model that incorporates circular operations pillars, enabling technologies and conditions, and mediating organizational capabilities. This paper aims to construct such a model, grounded in socio-technical systems theory and aligned with sustainable development goals.

1.3. Research Aim and Contribution

This paper seeks to develop a conceptual model that enables the integration of circular principles into the operational core of manufacturing systems. Specifically, it proposes an interlinked framework that combines four operational pillars—circular input management, looping processes, product life extension, and reverse logistics—with key enablers (e.g., digital technologies, organizational culture) and a mediating mechanism: operational flexibility.

The core contributions of this paper are as follows:

- ▪

Theoretical Advancement: It bridges circular economy theory with operations management by offering a holistic and systems-based conceptualization of circular operations.

- ▪

Managerial Guidance: It provides a structured model for decision-makers to guide operational transformation toward sustainability and resource efficiency.

- ▪

Policy and Sustainability Alignment: The framework supports the realization of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), thereby aligning with global sustainability mandates.

Unlike prior works that isolate environmental efforts in design or logistics functions, this model adopts a cross-functional lens, addressing interdependencies across operational layers. By grounding the model in socio-technical systems theory, it emphasizes the co-evolution of processes, technologies, and people—ensuring that the transition toward circularity is not merely technical, but organizationally embedded and culturally supported [

19,

20,

21].

1.4. Structure of the Paper

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical foundations of the model, focusing on circular economy principles, operational sustainability strategies, and socio-technical systems theory.

Section 3 outlines the conceptual development of the model, detailing the key components, enablers, and mediating mechanisms.

Section 4 presents the proposed conceptual framework, supported by visual diagrams and a systemic analysis.

Section 5 discusses the theoretical and managerial implications of the model.

Section 6 offers directions for future research, and

Section 7 concludes with a summary of contributions and reflections on circular operations in manufacturing.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Circular Economy Foundations in Manufacturing

The concept of the circular economy (CE) has evolved into a cornerstone of contemporary sustainability discourse, particularly in resource-intensive industries such as manufacturing. At its core, CE challenges the conventional linear economic model by emphasizing a restorative and regenerative approach to production and consumption [

22]. Rather than pursuing efficiency through volume and velocity of material throughput, CE advocates for systemic resource stewardship, aiming to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation [

23,

24].

CE is built upon four core principles that guide the transformation of industrial systems:

- ▪

Reduce: minimizing the input of raw materials and energy through more efficient design and production strategies.

- ▪

Reuse: extending the usable life of components and products through reuse in original or alternative functions.

- ▪

Recycle: reprocessing materials to be reintroduced into production systems without significant loss of quality.

- ▪

Regenerate: enabling natural systems and materials to restore themselves, especially in bio-based cycles [

25,

26].

In manufacturing, these principles are operationalized through two dominant system constructs:

Closed-loop manufacturing involves designing processes in which waste materials are reabsorbed into the production cycle as new inputs, effectively eliminating the traditional concept of waste [

27,

28]. This model necessitates technical innovation in sorting, disassembly, and remanufacturing, as well as product designs that facilitate modularity and material recovery. Industries such as electronics, automotive, and textiles have begun exploring this model, though its mainstream implementation remains limited.

- 2)

Industrial Symbiosis

A broader extension of the closed-loop idea is found in industrial symbiosis, where the waste or by-products of one process or firm become valuable inputs for another. This inter-organizational cooperation redefines supply chains as networks of mutual material exchange, rather than linear delivery systems [

29,

30,

31]. Eco-industrial parks in Denmark, Japan, and China provide compelling examples of how industrial symbiosis can reduce resource dependence and generate collective environmental gains [

32,

33].

Importantly, circularity is not merely about end-of-life strategies, but increasingly about designing systemic operational transformations. CE requires a paradigm shift in how manufacturing systems are conceptualized—from linear throughput models focused on efficiency, toward regenerative systems that prioritize durability, adaptability, and material circularity across the entire product life cycle [

34,

35,

36].

This shift involves integrating CE into the DNA of operations strategy, requiring changes in how processes are configured, how success is measured, and how organizational capabilities are developed. It also demands coordination across functions such as procurement, product development, and logistics—making circularity not just a technical strategy, but a cross-functional operational philosophy [

37,

38,

39].

As CE moves from a conceptual aspiration to a strategic imperative, it becomes essential to frame circularity as a core logic for redesigning manufacturing operations, rather than as a peripheral sustainability initiative. The next sections elaborate how this logic intersects with operational efficiency and socio-technical complexity in modern manufacturing environments.

2.2. Operations Management for Sustainability

Operations management (OM) has long been the engine room of industrial progress, traditionally concerned with optimizing productivity, cost, and quality. Yet in an era of climate breakdown, resource scarcity, and shifting stakeholder expectations, this discipline faces a renewed imperative: to enable sustainability not only at the strategic level but within the heartbeat of daily operations [

40].

Over the past two decades, three sustainability-oriented paradigms have emerged within OM: lean, green, and circular. While all three strive to minimize waste and improve resource utilization, they do so with distinct philosophies and tools—and more importantly, with different endpoints in mind.

Lean operations, rooted in the Japanese manufacturing tradition, emphasize the elimination of all forms of waste (muda) that do not add value from the customer’s perspective. This includes time, inventory, overproduction, and unnecessary motion. Lean is process-driven, data-informed, and intensely focused on flow and efficiency [

41,

42,

43]. However, lean tends to focus inward—on the boundaries of the firm—often overlooking environmental or social externalities.

Green operations expand the scope of concern. They integrate environmental performance metrics into decision-making, aiming to reduce carbon emissions, energy consumption, and water usage. Unlike lean, green thinking incorporates regulatory compliance, eco-labeling, and life-cycle assessments into operations strategy [

44]. Yet, many green initiatives are implemented as isolated programs—environmental add-ons rather than systemic redesigns.

The circular operations approach represents a deeper shift. Rather than treating sustainability as an efficiency problem or a compliance issue, circularity reimagines the operational system itself. Products are designed to last longer, be repaired, remanufactured, or returned—and operations are configured to close the loop on material flows. This calls for a fundamental change in processes, technologies, and organizational mindsets [

45,

46].

Importantly, these paradigms are not exclusive. In fact, the intersection of lean, green, and circular offers fertile ground for innovation. For example, lean’s discipline in reducing overproduction can complement green goals of lowering emissions, while circular systems benefit from lean’s focus on precision and waste avoidance. However, conflicts also arise: lean’s drive for minimal inventory may clash with the storage needs of reverse logistics in circular models, and green procurement may overlook reuse potential if lifecycle thinking is absent [

47].

To provide clarity on how these paradigms compare—and where they may complement or contradict each other—

Table 1 summarizes their defining features across key operational dimensions.

2.3. Socio-Technical System Theory

The transition toward circular operations in manufacturing cannot be achieved through technological innovation alone. Nor can it succeed through isolated managerial initiatives. At its core, circularity is a systemic transformation—and to understand such transformation, we must adopt a lens that views organizations not merely as technical machines, but as dynamic configurations of human, social, and technical subsystems. This is precisely the premise of the socio-technical system (STS) theory.

Originating in the 1950s from work by the Tavistock Institute, STS theory posits that organizations are open systems, embedded in and responsive to their environment, composed of two interdependent sub-systems: the technical (tools, processes, infrastructure) and the social (people, norms, culture) [

48,

49]. Sustainable and effective performance emerges only when these sub-systems are jointly optimized, not treated in isolation.

In the context of manufacturing, this perspective is particularly vital. Circular operations require not only the adoption of new technologies—such as AI-enabled waste tracking or IoT-based remanufacturing—but also new routines, mindsets, and institutional structures that support collaboration, adaptability, and long-term orientation [

50,

51]. Without alignment between the technological design of operations and the human systems that enact them, circularity risks becoming a technical ideal unsupported by organizational reality.

STS theory challenges the notion that sustainability can be „engineered” purely through technical systems. It emphasizes the interdependence of actors, artifacts, and structures. For instance, a closed-loop material system may fail if employees are not trained to separate components correctly; similarly, an AI-powered optimization tool may underperform without a culture of data-informed decision-making [

52]. Circular operations, therefore, must be designed with awareness of how social behavior and institutional logic shape system performance.

Moreover, STS provides the conceptual foundation to understand how organizations adapt over time. In rapidly evolving sustainability contexts—where regulations, technologies, and stakeholder expectations are in constant flux—organizations must function as adaptive systems, capable of sensing, learning, and restructuring [

53]. This view aligns closely with the aims of Sustainability journal, which emphasizes system analysis, resilience, and transdisciplinary approaches to sustainable development.

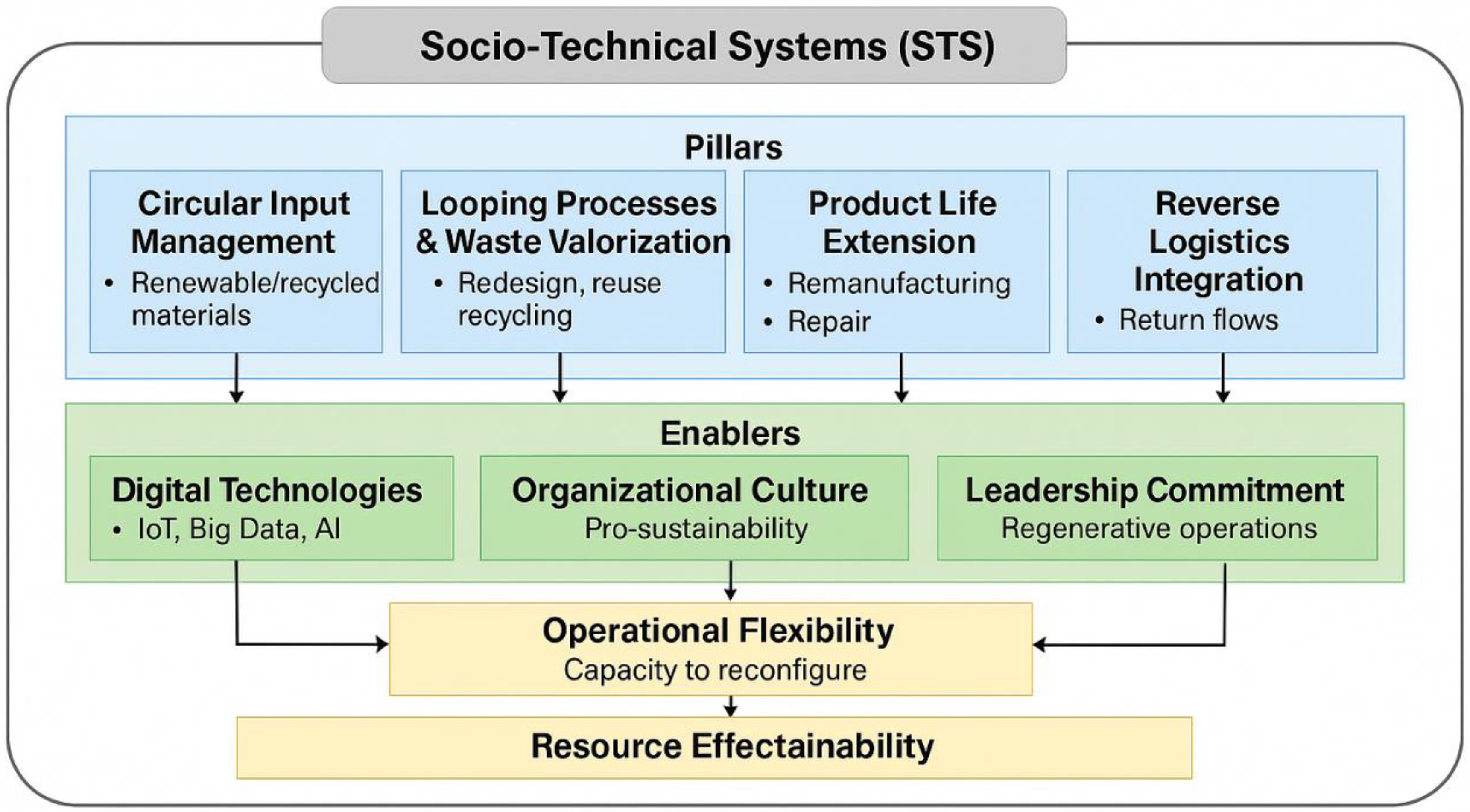

In this paper, the proposed conceptual model (see

Section 4) is grounded in STS theory. It treats circular operations not as a checklist of tools, but as a socio-technical reconfiguration—requiring integrated redesign of processes, technologies, and organizational capacities. The mediating role of operational flexibility reflects this integration: flexibility is not simply a production feature, but an emergent property of a system where human and technical components are aligned for adaptive, circular performance [

54].

By using STS as its theoretical anchor, this framework contributes not only to the operationalization of circular economy principles but also to the broader discourse on sustainable organizational transformation—resonating with both the technical and social dimensions of sustainability science.

3. Conceptual Framework Construction

3.1. Core Components of Circular Operations

In designing circular operations, it is essential to move beyond abstract principles and identify core components that can be translated into tangible operational strategies. Drawing from circular economy literature and socio-technical systems theory, this paper outlines four fundamental pillars of circular operations that—when integrated into the design and execution of manufacturing systems—can drive sustainable and regenerative performance.

These pillars represent not just discrete initiatives, but interlocking capabilities that enable organizations to reduce dependency on virgin resources, minimize waste, and close material loops. Each pillar addresses a specific phase of the product-material cycle and is rooted in a systemic understanding of how value can be retained, recovered, and recirculated across the operation.

- 1)

Circular Input Management

At the foundation of circular operations lies input substitution—shifting away from finite and non-renewable materials toward renewable, recycled, or biodegradable inputs. This involves redesigning procurement strategies, engaging with new supplier ecosystems, and often reengineering product components to accommodate alternative materials [

55]. Circular input management also requires assessment of material circularity, traceability mechanisms, and life-cycle compatibility.

Beyond the material dimension, this pillar supports strategic objectives such as supply chain resilience, cost reduction from secondary material use, and alignment with environmental regulations or eco-certification schemes [

56].

- 2)

Looping Process & Waste Valorization

This pillar focuses on redesigning production processes to recapture by-products, scraps, and emissions and reintegrate them as valuable inputs—either within the same process or across different operations [

57]. It includes strategies such as industrial symbiosis, internal material recovery loops, energy recovery, and process innovation for by-product transformation.

Rather than treating waste management as an end-of-pipe solution, circular looping reframes production waste as a secondary resource stream, enhancing both environmental and operational efficiency. Technologies like real-time waste tracking, AI-enabled material segregation, and modular processing lines support this pillar’s implementation.

- 3)

Product Life Extension

Extending the functional lifespan of products is central to reducing resource depletion and material throughput. Product Life Extension (PLE) encompasses strategies such as repair, refurbishing, remanufacturing, and upgradability [

58,

59,

60,

61]. From a design perspective, this requires modularity, standardization, and disassembly-friendly interfaces. From an operational standpoint, it calls for service-oriented capabilities, reverse engineering processes, and warranty redesign.

PLE shifts the role of operations from pure production to value regeneration, often supported by digital twins, condition monitoring, and predictive maintenance technologies. The business logic moves toward performance-based or product-service systems (PSS), reinforcing both customer retention and resource stewardship [

58,

62].

- 4)

Reverse Logistics Integration

Circularity cannot succeed without efficient mechanisms to return, sort, and reintegrate products or materials after use. Reverse logistics is not merely a supply chain issue—it is an operational challenge involving storage, disassembly, testing, and secondary use routing [

63]. For reverse flows to be effective, firms must develop infrastructures for product take-back, customer participation models, and digital tracking of post-use assets.

Integrating reverse logistics into operations provides strategic advantages: access to secondary materials, visibility into product usage patterns, and a pathway to engage with circular business models such as leasing or buy-back programs.

To synthesize the roles and contributions of each pillar,

Table 2 provides a comparative overview—including definitions, core objectives, and strategic value within a circular operations context.

If these pillars are viewed in isolation, circular operations risk fragmentation. The next section, therefore, explores the enabling conditions and mediating mechanisms that bind these pillars into a cohesive, adaptive system.

3.2. Enablers of Circular Operations

Circular operations cannot be realized through technical process design alone. They depend heavily on the enabling infrastructure—both technological and organizational—that supports the activation, coordination, and evolution of circular practices. While the operational pillars described earlier provide the what of circularity, the enablers represent the how—the necessary conditions that empower and sustain circular transformation across functions and time.

Three categories of enablers stand out as particularly critical for manufacturing firms striving to embed circularity at the operational level: digital technologies, organizational culture, and leadership commitment.

- 1)

Digital Technologies: IoT, Big Data, and AI

The integration of digital technologies is one of the most transformative enablers of circular operations. Tools such as Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, Big Data analytics, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) provide real-time visibility into material flows, product conditions, and waste generation points—enabling firms to design responsive and adaptive systems [

64,

65].

IoT devices can track usage patterns, detect anomalies in production, and signal maintenance needs, thereby supporting product life extension and predictive servicing. Meanwhile, AI algorithms can optimize reverse logistics routes, identify remanufacturing opportunities, and dynamically allocate secondary materials to minimize waste and costs [

66]. Big Data further enhances decision-making by revealing inefficiencies and simulating closed-loop scenarios that would be impossible to manage manually.

In essence, digitalization converts the circular economy from a static design ideal into a data-driven operational reality.

- 2)

Organizational Culture for Circularity

While technologies may offer the tools for change, culture determines whether change takes root. A circular operations model requires more than compliance; it demands a shift in how employees think about waste, value, responsibility, and success. Cultures that reward short-term throughput and cost-cutting can stifle circular ambitions, no matter how advanced the tools deployed [

67,

68,

69].

By contrast, an organizational culture that internalizes sustainability principles—prioritizing long-term impact, collaborative problem-solving, and systems thinking—can foster the cross-functional integration required for circular success. Such cultures are characterized by openness to experimentation, psychological safety for innovation, and shared ownership over environmental performance.

Importantly, cultural transformation often precedes performance gains. It is the invisible architecture that aligns behavior with vision, embedding circular thinking into daily routines and operational decisions [

70].

- 3)

Leadership Commitment to Regenerative Operations

Lastly, leadership plays a catalytic role in setting direction, allocating resources, and legitimizing new models of operational performance. Circular transformation is inherently disruptive—it challenges KPIs, redefines stakeholder priorities, and often requires a leap of faith before benefits materialize. Without clear and consistent leadership commitment, circular initiatives risk being relegated to symbolic gestures or isolated pilot projects [

71].

Regenerative operations—those designed not only to sustain but to restore and renew—demand strategic foresight and moral courage from leaders. These leaders must go beyond supporting sustainability rhetorically; they must translate values into budgets, policies, and expectations. They must also create incentives that align performance evaluation with circular outcomes: not just units produced, but value retained and impact avoided [

72,

73].

Leadership, in this view, is not just hierarchical—it can also emerge through distributed champions who advocate for circularity across departments, linking top-down vision with bottom-up action.

Together, these enablers form the supportive ecosystem within which circular operations can be imagined, tested, scaled, and sustained. Without them, even the most well-designed operational models will struggle to survive inertia, fragmentation, or organizational resistance. The next section introduces a mediating capability—operational flexibility—that links these enablers to actual performance in dynamic industrial contexts.

4. Proposed Conceptual Model

4.1. Overview of the Conceptual Framework

Circular operations represent a transformative shift in how manufacturing systems are designed, executed, and evaluated. Yet, the complexity of this transformation—spanning technologies, people, processes, and mindsets—necessitates a conceptual framework that offers clarity, structure, and strategic direction. The proposed model in this paper is grounded in circular economy principles, informed by socio-technical systems theory, and oriented toward achieving operational sustainability and resource efficiency in manufacturing contexts.

At its foundation, the model draws from the logic of the circular economy: that value should be retained and regenerated through continual cycles of use, recovery, and reintegration [

74]. But unlike traditional CE frameworks that focus on product design or end-of-life logistics, this model locates circularity at the heart of operations, treating production not as a linear function but as a dynamic, adaptive, and circular system.

The second layer of the model integrates socio-technical thinking, recognizing that operational change is not just about machines or flows—it is about people, culture, information, and interaction. The model acknowledges that enabling circular operations requires technological infrastructure, organizational commitment, and cultural alignment to drive systemic behavior change [

75].

Finally, the framework introduces operational flexibility as a mediating capability: a dynamic competence that allows firms to absorb complexity, reconfigure resources, and respond to shifting material and market conditions [

76,

77]. Flexibility ensures that circular practices can adapt to scale, seasonality, and technological evolution, making the model not only sustainable but also resilient.

To visually capture the interplay between the pillars, enablers, mediator, and outcomes,

Figure 1 presents the proposed conceptual model for embedding circular operations in manufacturing.

This model integrates four operational pillars, three enabling factors, and a mediating variable (operational flexibility), all framed within a socio-technical systems (STS) perspective to support resource efficiency and operational sustainability.

4.2. Component Analysis of the Model

The conceptual model illustrated in

Figure 1 is designed not merely as a structural representation, but as a strategic mapfor embedding circularity into the core of manufacturing operations. To operationalize the model, it is essential to unpack its constituent elements—each of which plays a distinct yet interdependent role in enabling regenerative, efficient, and adaptive production systems.

These components are categorized into three functional layers: foundational pillars of circular operations, a mediating capability (operational flexibility), and a set of key enablers (technological, cultural, and leadership-based). Together, they converge toward a unified outcome: resource efficiency and operational sustainability. The following sections provide a concise yet integrative explanation of each component, drawing from the theoretical foundations established in earlier chapters.

Circular Input Management

This foundational pillar focuses on substituting finite, virgin materials with renewable, recycled, or biodegradable alternatives. As aligned with the “reduce” principle of circular economy theory, this component emphasizes sustainability at the point of material entry into the operational system [

78,

79]. Its implementation requires rethinking procurement standards and forming partnerships with circular suppliers, often necessitating redesign in product architecture to ensure compatibility.

In socio-technical terms, this transformation is not merely technical—it involves training procurement teams, revising quality standards, and redesigning supplier evaluation mechanisms [

80].

Looping Process & Waste Valorization

This component seeks to redesign internal processes so that production residues, offcuts, and energy losses are reintegrated as productive inputs, either within the same system or in synergy with other operations. Inspired by industrial symbiosis and internal circularity concepts, it reflects the “reuse” and “recycle” aspects of CE [

81,

82].

Technological innovations such as smart waste mapping and energy recovery systems support this loop, but their success depends on a process culture that encourages experimentation, modularity, and feedback [

83,

84,

85].

Product Life Extension

Extending the useful life of products through repair, remanufacturing, modular upgrades, or refurbishment is essential to circular performance. This component challenges traditional production KPIs based on volume and speed, and shifts focus toward durability, serviceability, and lifecycle performance [

86].

It integrates lean precision with green responsibility by slowing material throughput while maintaining value creation. Culturally, it demands customer-centric thinking and cross-departmental collaboration, particularly between design, engineering, and service operations [

87,

88].

Reverse Logistics Integration

Efficient and traceable reverse logistics is what connects consumption back to production. This component enables products or materials to be retrieved, sorted, and reprocessed for further use, thereby closing the operational loop [

89,

90,

91].

Its success depends on digital infrastructure, transparent policies, and user engagement, but also on a mindset shift—from linear delivery to circular flow thinking. When fully embedded, reverse logistics becomes a value-generating function rather than a cost center [

92,

93].

Operational Flexibility (Mediator)

Serving as the connective tissue of the model, operational flexibility enables the firm to respond dynamically to changes in material input, customer usage patterns, and feedback from reverse flows. It is the capacity to adapt without sacrificing efficiency, and it is what transforms circular initiatives from fixed routines into scalable systems [

94].

From a socio-technical perspective, flexibility is an emergent capability—requiring both reconfigurable technologies and an agile workforce culture [

95]. It is this capability that allows enablers to influence outcomes meaningfully and makes circularity operationally viable.

Enabling Factors: Digitalization, Culture, and Leadership

These enablers form the contextual foundation that empowers all pillars and sustains system adaptability:

- ▪

Digitalization equips the system with real-time data, predictive analytics, and smart coordination mechanisms [

96].

- ▪

Organizational culture fosters the shared norms and trust necessary for system-wide collaboration.

- ▪

Leadership commitment aligns circular goals with corporate strategy, ensures policy coherence, and signals legitimacy to stakeholders [

97].

Enablers are not passive background elements—they are active design levers that determine the speed, depth, and durability of circular integration.

Outcome: Resource Efficiency & Operational Sustainability

The ultimate objective of the model is to achieve resource efficiency (maximizing value per unit input) and operational sustainability (systems that endure, adapt, and regenerate). This dual outcome encapsulates both performance and resilience, and it reflects the essence of circularity as not just an ecological ideal, but a strategic operational advantage [

98,

99].

4.3. Feedback Mechanism and Systemic Interdependence

The effectiveness of circular operations lies not in the execution of individual components, but in how these components interact, adapt, and evolve over time. This requires a shift in perspective—from viewing operations as linear pipelines to understanding them as feedback-driven systems that continuously learn, adjust, and regenerate. Within this view, feedback mechanisms become essential not only for control, but for transformation.

In circular operations, two components play a critical role in sustaining re-looping cycles: reverse logistics and product life extension. These elements provide the physical and informational flows that allow used products, materials, or components to re-enter the system—not as waste, but as inputs of renewed value. Their effectiveness depends not only on infrastructure and design, but on the existence of a closed-loop intelligence that ensures learning and adaptation from every cycle [

100].

For instance, data gathered from returned products—such as frequency of component failure, wear patterns, or user behavior—can inform upstream design modifications, process adjustments, and material choices. Similarly, insights from repair or refurbishment processes can feed back into supplier evaluation, predictive maintenance protocols, or customer education programs. This feedback-driven flow ensures that operations are not static, but continuously shaped by real-world performance and circular outcomes [

101].

Moreover, feedback enhances resilience. When disruptions occur—such as material shortages, shifts in demand, or regulatory changes—systems with embedded feedback loops can reconfigure more rapidly. Operational flexibility (

Section 4.2) is the internal capability that allows this adaptation to occur, but feedback is the trigger and compass for reconfiguration. Without it, flexibility lacks direction.

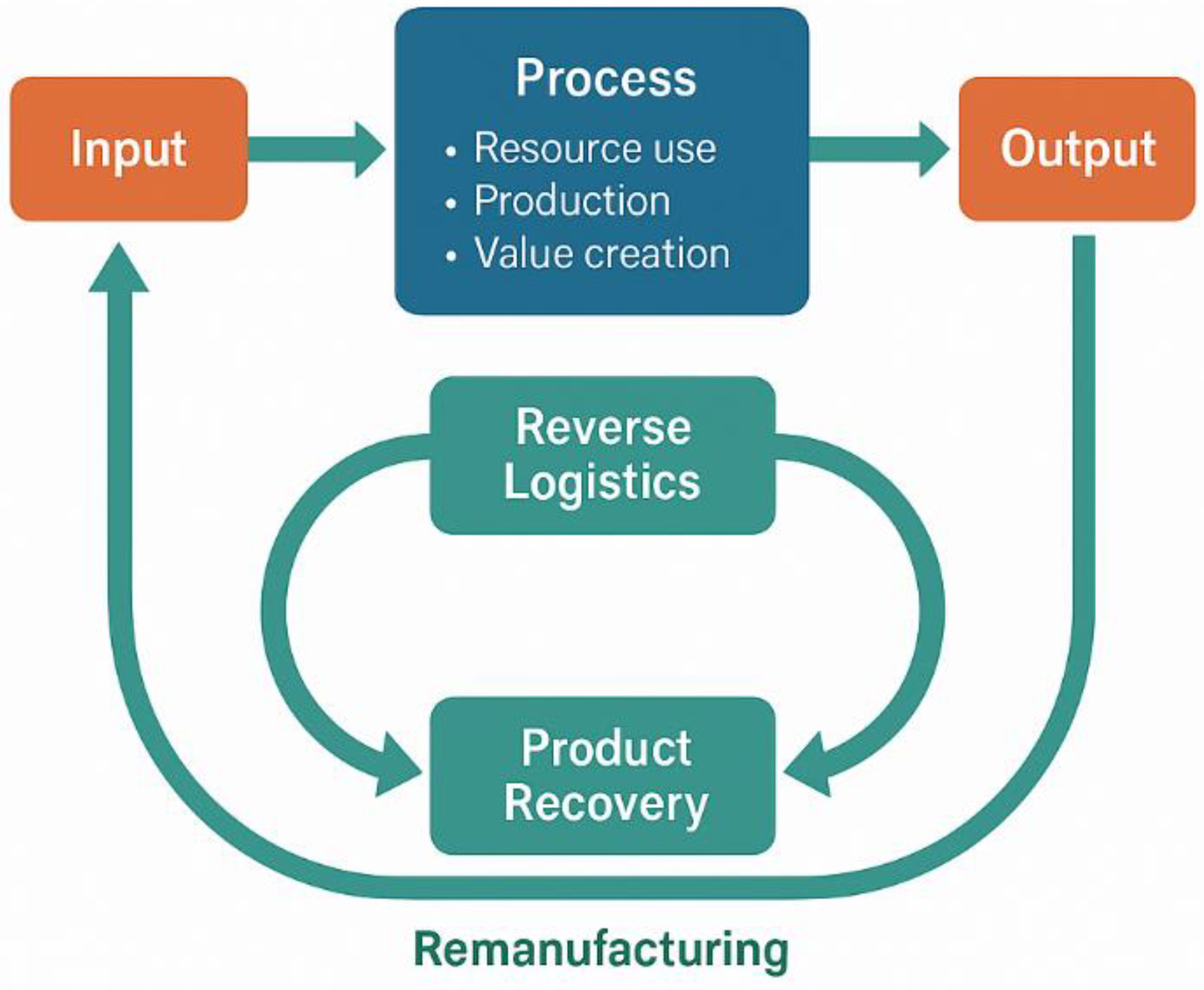

To visualize how this works,

Figure 2 illustrates the circular feedback loop mechanism embedded within the proposed model. It highlights how inputs and outputs are connected through operational and informational flows, and how learning occurs across life cycle stages to improve both performance and sustainability.

This visual illustrates the continuous flow of materials and information across the core circular operation pillars. Reverse logistics and product life extension form the basis of re-looping, while data feedback enables system-wide adaptation, optimization, and resilience. The diagram emphasizes that sustainable operations are not fixed structures but dynamic systems informed by feedback, enabled by flexibility, and driven by learning.

In essence, feedback transforms the system from reactive to regenerative. It ensures that circularity is not only designed but self-reinforced—turning each operational cycle into a source of insight, innovation, and improvement.

4.4. Model Validation Considerations and Theoretical Assumptions

While the proposed conceptual model presents a coherent framework for embedding circular operations into manufacturing, it is not without boundary conditions and theoretical assumptions. A clear articulation of these foundations is essential—not only to acknowledge the model’s scope, but also to provide guidance for future empirical testing and practical adaptation.

Theoretical Assumptions

At its core, the model assumes that manufacturing organizations possess a minimum threshold of structural and strategic readiness. Specifically, three enabling preconditions are implied:

- 1)

Digital Infrastructure

The model presumes the existence of digitally enabled operations, including sensor networks (e.g., IoT), real-time analytics (e.g., Big Data), and decision-support systems (e.g., AI tools). These technologies are essential to ensure visibility, traceability, and control over complex circular flows [

102,

103]. Organizations lacking such infrastructure may find the execution of real-time reverse logistics, looping processes, or product recovery unfeasible.

- 2)

Leadership Commitment

A foundational assumption is that leadership is aligned with long-term, regenerative strategies, and is willing to embed circular KPIs into operational performance measurement. Without such commitment—financially and culturally—the model’s pillars risk being fragmented or deprioritized amid competing operational pressures [

104].

- 3)

Maturity in Lean and Green Operations

The model is most applicable in organizational contexts where lean and green practices are already embedded. This includes experience with waste minimization, energy efficiency, and value stream mapping. These foundational practices offer a base upon which more complex circular processes—such as remanufacturing or product-service systems—can be layered effectively [

105].

These assumptions position the model as a next-step evolution in organizations already oriented toward efficiency and sustainability, rather than as a basic starting point for firms with minimal systems or fragmented operations.

Scenarios for Theoretical and Empirical Validation

To advance the model from conceptual to empirical relevance, several research scenarios may be pursued:

- ▪

Exploratory case studies can investigate how the model manifests in real manufacturing settings. For instance, longitudinal case research in firms implementing circular initiatives could assess which pillars are activated first, how enablers are aligned, and what trade-offs emerge during transitions.

- ▪

Structural equation modeling (SEM) or partial least squares (PLS) could be employed to test the mediating effect of operational flexibility between enablers (e.g., digital tech, culture) and outcomes (e.g., resource efficiency, circular performance). This would help verify the core logic of the model across multiple organizational contexts.

- ▪

Cross-industry comparative studies could assess how contextual variables—such as regulatory environments, supply chain complexity, or capital intensity—moderate the strength of relationships in the model.

- ▪

Simulation-based modeling, particularly system dynamics, could also be used to test feedback loop scenarios, especially regarding product recovery rates, reverse flow timing, and flexibility thresholds under uncertainty [

106].

In each of these validation paths, it is essential to preserve the systemic and interdependent nature of the model. Partial validations (e.g., testing one pillar in isolation) may yield limited insights unless interpreted within the broader circular system context.

Ultimately, this conceptual model is not intended as a static blueprint, but as a dynamic framework to guide empirical inquiry and operational redesign in the journey toward circular manufacturing.

5. Implications and Discussions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The conceptual model proposed in this paper contributes meaningfully to the evolving theoretical landscape at the intersection of circular economy (CE), operations management (OM), and socio-technical systems (STS). It offers an integrative lens through which sustainability can be operationalized, not merely as an environmental commitment, but as a strategically embedded capability within manufacturing organizations.

First, within the circular economy discourse, this model extends the literature beyond macro-level policy frameworks and product-level design principles by focusing on the meso-level of operations. Prior CE models have largely emphasized material flows or end-of-life strategies, often underplaying the structural and dynamic complexity of internal operations [

107,

108]. By introducing core pillars—such as circular input management, looping processes, product life extension, and reverse logistics—this model frames circularity as a systemic transformation embedded in the core of day-to-day production activities.

Second, in the field of operations management, this model bridges a crucial gap between lean/green paradigms and circular operational logic. While lean focuses on waste elimination and green on environmental compliance, both have traditionally lacked the regenerative and restorative dimensions of circularity [

109,

110]. The model thus positions circular operations as a post-lean/post-green evolution, enabling scholars to reconceptualize value creation not just as efficiency, but as value retention and recirculation across production cycles. It invites redefinition of familiar OM constructs—such as productivity, utilization, and throughput—through a sustainability-centered lens.

Third, the integration of socio-technical systems theory grounds the model in a robust theoretical foundation that appreciates the interdependence between technological enablers, human capabilities, and organizational routines. This theoretical anchoring moves the discussion beyond technological determinism or behavioral idealism. The STS perspective acknowledges that the success of circular operations depends not only on having the right infrastructure, but on achieving alignment between the technical architecture and the social system that drives it [

111,

112].

This model, therefore, helps fill a conceptual void in the literature: the absence of a cohesive, operational-level framework that bridges strategic sustainability goals with executable practices, mediated by organizational capabilities. It invites scholars to engage with circularity not merely as a normative or aspirational concept, but as a construct with internal mechanisms, causal pathways, and contingencies—all of which are necessary for theory development and testing.

Finally, the model stimulates cross-disciplinary dialogue between industrial ecology, organizational theory, and digital operations. By positioning operational flexibility as a mediating mechanism, the model opens space for research that blends system dynamics, capability theory, and adaptive operations—fields that have historically evolved in silos. This alignment supports the journal Sustainability’s aim to foster integrated knowledge capable of addressing the multidimensional complexity of sustainable development.

5.2. Managerial and Policy Implications

The transition from linear to circular operations is not merely a technical upgrade—it is a strategic reorientation of how manufacturing firms create, deliver, and retain value. The proposed model has several implications for managers, especially those operating in resource-intensive industries such as automotive, electronics, and fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), where material costs, environmental pressures, and lifecycle accountability are high.

At a practical level, this model offers a stepwise roadmap for embedding circularity across operational layers. Managers can use the four operational pillars—Circular Input Management, Looping & Waste Valorization, Product Life Extension, and Reverse Logistics—as a structured guide for redesigning their current production logic. Rather than viewing circularity as a peripheral CSR program, it encourages integration into the core KPIs, supply chain design, and process engineering of the firm.

Industries such as automotive and electronics are already experiencing reverse flow pressure—through regulations like Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and customer demand for after-sales service. For these sectors, the model helps prioritize internal capabilities needed to support take-back systems, component reuse, and remanufacturing operations at scale. In FMCG, the model can inform packaging redesign, supplier selection, and data-driven recovery strategies—all while enhancing brand equity and regulatory compliance.

From a policy perspective, the model provides a blueprint for designing readiness assessment tools, incentives, and sectoral transition strategies. Policymakers can reference the model’s structure to:

- ▪

Define criteria for circularity-linked tax benefits or subsidies,

- ▪

Set capability benchmarks in eco-industrial parks, or

- ▪

Support SMEs in building digital and cultural foundations for circular implementation.

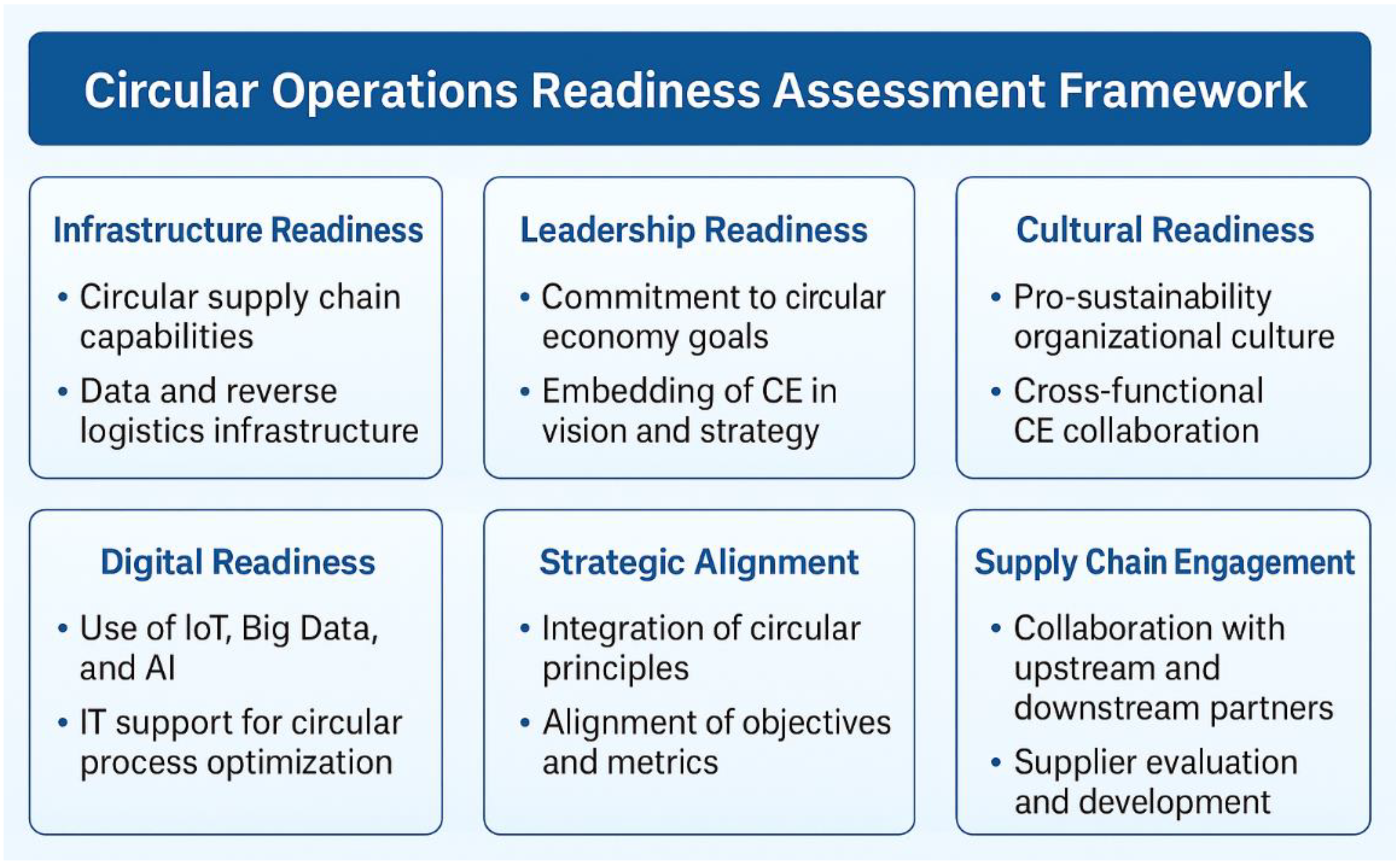

To support firms in assessing their own transition capacity,

Figure 3 presents a Circular Operations Readiness Assessment Framework. It outlines six key readiness domains—spanning infrastructure, leadership, culture, digitalization, strategic alignment, and supply chain integration—each of which must be evaluated prior to initiating or scaling circular transformation.

This framework assists organizations in evaluating their preparedness to adopt and scale circular operational models. Each readiness domain includes guiding indicators and assessment checkpoints, providing a diagnostic view of where an organization stands and what it must prioritize to enable systemic circularity.

By using this framework, managers and policymakers can move beyond aspirational declarations of sustainability and toward measurable, staged, and systemic circular transitions.

6. Future Research Agenda

The conceptual model presented in this paper offers a comprehensive framework for embedding circular operations into manufacturing systems. However, to strengthen its academic contribution and practical applicability, further research is needed to test, refine, and contextualize its components. This section outlines five strategic directions for future inquiry, organized into structured sub-sections, to guide scholars and practitioners in advancing circular operations theory and practice.

6.1. Empirical Validation of the Framework

The first and most essential step is the empirical validation of the model’s theoretical structure and interrelationships. While the framework is grounded in circular economy, operations management, and socio-technical systems theory, it must be tested across real-world contexts to assess its explanatory power and practical relevance.

Future research can apply structural equation modeling (SEM) or partial least squares (PLS) to examine the mediating effect of operational flexibility between enabling factors (digitalization, culture, leadership) and outcomes (resource efficiency and operational sustainability). Complementing this, mixed-method designs—combining quantitative surveys with field observations or interviews—are critical to capture both systemic interactions and human behavioral dynamics.

Moreover, longitudinal case studies in circular frontrunner firms can offer insights into the sequencing, trade-offs, and adaptation mechanisms that unfold during implementation. These approaches will help uncover emergent properties and feedback patterns, which are often invisible in cross-sectional research.

6.2. Development of Readiness and Maturity Indicators

The model highlights six key readiness domains (as presented in

Figure 3), but these need to be operationalized into measurable indicators and validated scales. Future research should focus on developing:

- ▪

A maturity model that captures progressive integration levels of circular operations.

- ▪

Diagnostic instruments that help organizations benchmark capabilities and identify critical gaps.

- ▪

Sector-specific adaptations for different industries (e.g., electronics, automotive, FMCG).

Such tools will support not only academic inquiry, but also practical decision-making in firms and policy design. To ensure utility, research should apply Delphi panels, pilot validation, and psychometric testing, ensuring a balance between scalability and contextual sensitivity.

Importantly, scholars should investigate organizational readiness configurations—examining how different combinations of strong or weak enablers influence transition outcomes. For instance, does high digital maturity compensate for low cultural readiness? Understanding these interaction patterns can lead to more nuanced guidance.

6.3. Comparative Industry and Country-Level Studies

As circular practices are context-dependent, cross-industry and cross-national studies are needed to explore how the model performs under varying institutional, technological, and cultural conditions. Different sectors vary in their circular potential, regulatory environments, and stakeholder pressures.

For example, electronics and automotive sectors face strong take-back mandates and technical recovery complexity, while FMCG industries emphasize packaging circularity and speed of logistics. Future studies should explore:

- ▪

Sectoral divergence in pillar implementation.

- ▪

Regulatory drivers and barriers.

- ▪

Cross-functional coordination mechanisms under supply chain uncertainty.

At the national level, research should investigate how institutional logics, governance quality, and societal norms affect readiness and adoption. There is also a compelling case to explore institutional frictions—e.g., when global supply chains operate across countries with asymmetric circular maturity, resulting in implementation gaps and coordination breakdowns.

6.4. System Dynamics and Simulation Modeling

Given the non-linear and adaptive nature of circular operations, future research should utilize system dynamics modeling to simulate how circular processes evolve over time. Simulations can help:

- ▪

Explore threshold conditions under which feedback loops reinforce or stall.

- ▪

Evaluate the long-term impact of policy interventions or market disruptions.

- ▪

Model the effects of partial adoption (e.g., circular input but no reverse logistics).

This approach will enable researchers and firms to test scenarios, compare policy options, and understand how circular performance is influenced by delays, bottlenecks, or learning rates—an essential element often missed in static models.

6.5. Theoretical Expansion and Interdisciplinary Integration

Finally, future research should build on this model to foster theoretical expansion. Beyond CE, OM, and STS, scholars could link the framework to:

- ▪

Capability theory – exploring how dynamic capabilities like flexibility emerge, evolve, and drive performance.

- ▪

Institutional theory – studying how legitimacy, norms, and external pressures shape circular implementation.

- ▪

Behavioral operations – investigating how decision-making, risk perception, and organizational inertia affect transitions.

This model also opens space for cross-disciplinary integration, bridging engineering, sustainability science, organizational behavior, and digital transformation research. Such integration aligns with Sustainability journal’s mission to support transdisciplinary science for transformative impact.

By advancing these five research pathways, scholars can move beyond „what circular operations should look like” toward understanding how, when, and under what conditions they create value and resilience. The future of circularity lies not just in designing frameworks, but in activating and adapting them through evidence, experimentation, and collaboration.

7. Conclusion

This paper has proposed a comprehensive conceptual model for embedding circular operations within manufacturing systems—integrating foundational pillars, enabling conditions, and mediating capabilities into a cohesive operational framework. Grounded in circular economy principles, enriched by operations management perspectives, and structured through the lens of socio-technical systems theory, the model offers both theoretical and practical insights for advancing sustainability in industrial contexts.

At the heart of the model are four interconnected operational pillars: Circular Input Management, Looping Process & Waste Valorization, Product Life Extension, and Reverse Logistics Integration. These are supported by key enablers—digitalization, organizational culture, and leadership commitment—and mediated by operational flexibility, which serves as the dynamic capability allowing firms to adapt, reconfigure, and thrive in uncertain environments. The framework culminates in two strategic outcomes: resource efficiency and operational sustainability.

The model addresses a critical gap in the literature: the absence of an integrative, systems-oriented framework that connects circularity with internal operations strategy. Rather than treating sustainability as an external add-on or compliance burden, this model positions circularity as a core operational logic—requiring cultural alignment, digital infrastructure, and leadership vision.

Relevance to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is explicit. The model contributes directly to SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) by promoting advanced, resilient, and sustainable manufacturing systems, and to SDG 12(Responsible Consumption and Production) by operationalizing closed-loop resource flows. More broadly, it aligns with the principles of regenerative economics, in which value is not extracted and discarded, but circulated and renewed.

For policymakers and industry leaders, this model offers a strategic lens for guiding circular transitions—whether through incentive design, capability benchmarking, or roadmap development. For scholars, it serves as a fertile foundation for future empirical testing, tool creation, and theoretical expansion.

As global sustainability challenges intensify, the need for actionable, integrated, and system-aware operational models becomes ever more urgent. This framework is a step in that direction—toward an industrial future that is not only efficient, but regenerative, adaptive, and enduring.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.S. and S.P.; methodology, S.P.; software, A.D.; validation, A.S., S.P. and A.D.; formal analysis, S.P.; investigation, A.S.; resources, A.D.; data curation, A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, S.P.; visualization, S.P.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.D.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was self-funded by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE |

Circular Economy |

| OM |

Operations Management |

| STS |

Socio-Technical Systems |

| PLE |

Product Life Extension |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| KPI |

Key Performance Indicator |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modeling |

| PLS |

Partial Least Squares |

| FMCG |

Fast-Moving Consumer Goods |

| EPR |

Extended Producer Responsibility |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| PSS |

Product-Service System |

References

- T. M. Prenzel et al., “Bringing Light into the Dark—Overview of Environmental Impacts of Carbon Fiber Production and Potential Levers for Reduction,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 16, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Deng et al., “Optimization strategies for the carbon footprint of aluminum-plastic materials under low-carbon targets,” J Clean Prod, vol. 498, 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. F. Islam, B. N. F. Islam, B. Gogoi, R. Saikia, H. Sarma, B. Yousaf, and M. Narayan, “Encouraging circular economy and sustainable environmental practices by addressing waste management and biomass energy production,” Regional Sustainability, vol. 5, no. 4, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Abdul Hamed et al., “Advancing pyrolysis of sewage sludge: Bibliometrics analysis, life cycle assessment, and circular economy insights,” Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, vol. 63, 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Reda and Y. T. Park, “Sustainable synthesis of functional nanomaterials: renewable resources, energy-efficient methods, environmental impact and circular economy approaches,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 516, 2025. [CrossRef]

- W.-H. Chen et al., “Applications, life cycle assessment, and circular economy of bamboo torrefaction for sustainability: A state-of-the-art review,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 431, 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Morseletto, “Restorative and regenerative: Exploring the concepts in the circular economy,” J Ind Ecol, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 763–773, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Olczak, D. M. W. Olczak, D. M. Patten, and H. Shin, “Circular economy to the rescue? The U.S. corporate disclosure response to the plastic crisis,” Accounting Forum, vol. 47, no. 4, pp. 646–666, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Mumali and J. Kałkowska, Principles for intelligent decision support systems in industrial manufacturing processes. 2024.

- D. Skalli, A. D. Skalli, A. Charkaoui, and A. Cherrafi, “Assessing interactions between Lean Six-Sigma, Circular Economy and industry 4.0: toward an integrated perspective,” in IFAC Papersonline, 2022, pp. 3112–3117. [CrossRef]

- V. De Simone, V. V. De Simone, V. Di Pasquale, S. Miranda, and M. E. Nenni, “Sustainable Production Planning and Control in Manufacturing Contexts: A Bibliometric Review,” Sustainability Switzerland, vol. 15, no. 18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Adams, J. D. Adams, J. Donovan, and C. Topple, “Achieving sustainability in food manufacturing operations and their supply chains: Key insights from a systematic literature review,” Sustain Prod Consum, vol. 28, pp. 1491–1499, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Alshammari, U. D. S. S. Alshammari, U. D. Ani, S. Sarfraz, K. Salonitis, and O. Okorie, Digital Capability as an Enabler of Circular Economy in Saudi Arabia’s Manufacturing Sector, vol. 558 LNCE. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Uvarova, D. Atstaja, T. Volkova, J. Grasis, and I. Ozolina-Ozola, “The typology of 60R circular economy principles and strategic orientation of their application in business,” J Clean Prod, vol. 409, 2023. [CrossRef]

- U. Awan, I. U. Awan, I. Gölgeci, D. Makhmadshoev, and N. Mishra, “Industry 4.0 and circular economy in an era of global value chains: What have we learned and what is still to be explored?,” J Clean Prod, vol. 371, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kazancoglu, Y. D. Y. Kazancoglu, Y. D. Ozkan-Ozen, M. Sagnak, I. Kazancoglu, and M. Dora, “Framework for a sustainable supply chain to overcome risks in transition to a circular economy through Industry 4.0,” Production Planning and Control, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 902–917, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Behl, R. Singh, V. Pereira, and B. Laker, “Analysis of Industry 4.0 and circular economy enablers: A step towards resilient sustainable operations management,” Technol Forecast Soc Change, vol. 189, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, T. Otero-Romero, and E. J. Alvarez-Palau, “Navigating the transition to industry 5.0: advancing sustainability, resilience, and human-centricity in Spanish supply chain management,” Discover Sustainability, vol. 6, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Kanger, “The spatial dynamics of deep transitions,” Environ Innov Soc Transit, vol. 44, pp. 145–162, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Zhang, Multi-stakeholder ecosystems for sustainability transitions. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. K. R. Robinson, Constructive technology assessment: supporting the reflexive co-evolution of technology and society. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Mukherjee et al., “Socio-economic sustainability with circular economy — An alternative approach,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 904, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C.-K. Yang, H.-W. C.-K. Yang, H.-W. Ma, K.-H. Liu, and M.-H. Yuan, “Measuring circular economy transition potential for industrial wastes,” Sustain Prod Consum, vol. 40, pp. 376–388, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Rambau, P. T. L. D. Rambau, P. T. Mativenga, and A. L. Marnewick, “Enhancing frameworks for utilising Sankey diagrams in modelling the water-energy nexus and circularity,” J Clean Prod, vol. 456, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Le, V. R. L. Le, V. R. Reddy, J. Jin, and D. B. Rahut, “Circular economy and sustainable agriculture ecosystems a case of hybrid paper mulberry in the Yellow River Basin, China,” Discover Sustainability, vol. 6, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Ismail and G. M. E. Zokm, “Algae as keystone for blue economy: sustainability and challenges,” Discover Sustainability, vol. 6, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Mo, Q. L. Mo, Q. Zhang, X. Zhang, and A. B. Aris, “Zero-Waste Plant Dyeing: A Feasibility Study on Utilizing Agricultural Waste for Sustainable Textile Production in the Lingnan Region,” in E3s Web of Conferences, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Ventura, M. V. Ventura, M. Bortolini, C. Mora, M. La Monica, and L. Cutaia, “Blockchain and industrial symbiosis: a preliminary two-step framework to green circular supply chains,” International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 17–30, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Isafiade, N. J. Isafiade, N. Cowen, A. Vogel, L. Čuček, and Z. Kravanja, “Synthesis of utility supply chain network and industrial symbioses for heat integration,” J Clean Prod, vol. 380, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Bouazizi, M. H. Bouazizi, M. Benali, J.-M. Frayret, and R. Larbi, “Joint Design and Pricing Problem for Symbiotic Bioethanol Supply Chain Network: Model and Resolution Approach,” Cleaner Energy Systems, vol. 9, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Fussone, S. R. Fussone, S. Cannella, R. Dominguez, and C. Sammatrice, “Enhancing circular economy through industrial symbiosis: An agent-based simulation analysis of supply chain dynamics,” Sustainable Operations and Computers, vol. 6, pp. 130–139, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, C. Brehm, and A. Layton, “Evaluating benefits of ecologically-inspired nested architectures for industrial symbiosis,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 167, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Jung, X. S. Jung, X. Bi, S. An, J. Park, and H.-S. Park, “Assessment of a critical mineral recycling network: A case study on nickel recovery from production waste in Korean eco-industrial parks,” J Ind Ecol, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann Trevisan, C. Sassanelli, F. Acerbi, S. Terzi, and I. Dukovska-Popovska, “Skills for the twin transition in manufacturing: A systematic literature review,” J Clean Prod, vol. 474, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Schipfer et al., “The circular bioeconomy: a driver for system integration,” Energy Sustain Soc, vol. 14, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, T. Otero-Romero, and E. J. Alvarez-Palau, “Navigating the transition to industry 5.0: advancing sustainability, resilience, and human-centricity in Spanish supply chain management,” Discover Sustainability, vol. 6, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Amir, S. S. Amir, S. Sweet, N. Salehi, M. Roci, and A. Rashid, Toward a Circular Economy: A Guiding Framework for Circular Supply Chain Implementation, vol. 23. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chirumalla, F. Balestrucci, A. Sannö, and P. Oghazi, “The transition from a linear to a circular economy through a multi-level readiness framework: An explorative study in the heavy-duty vehicle manufacturing industry,” Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, vol. 9, no. 4, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Ababio, W. K. Ababio, W. Lu, K. Agyekum, and F. A. Ghansah, “Enhancing circular construction through procurement: A conceptual stakeholder-centric collaborative framework for sustainable outcomes,” Environ Impact Assess Rev, vol. 112, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S. Bresciani, P. De Bernardi, and G. Subhani, “Nexus of ambidexterity and frugal innovation for enhanced ESG performance of entrepreneurial firms. The role of organizational capabilities,” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, vol. 21, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Guo and, S. Mantravadi, “The role of digital twins in lean supply chain management: review and research directions,” Int J Prod Res, vol. 63, no. 5, pp. 1851–1872, 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Converso, G. G. Converso, G. Guizzi, E. Salatiello, and S. Vespoli, “Lean Service Waste Classification and Methodological Application in a Case Study,” Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, vol. 9, no. 4, 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Ahmad et al., “Production Process Improvement Towards Lean Process Effectiveness using FlexSim Simulation Software,” Journal of Advanced Research Design, vol. 132, no. 1, pp. 52–65, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Uzun Ayvaz and, B. Onat, “Integrating rooftop photovoltaics into urban rail infrastructure: A life cycle assessment with environmental impacts and localization insights,” Energy for Sustainable Development, vol. 87, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Yoo, and M. Alavi, Use Advanced Information Technology to Transform Organizations. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz Gezgin and M., A. Arıcıoğlu, “Industry 4.0 and Management 4.0: Examining the Impact of Environmental, Cultural, and Technological Changes,” Sustainability Switzerland, vol. 17, no. 8, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Sasso, G. M. D. R. A. Sasso, G. M. D. Ganga, and M. G. Filho, “Synergizing lean management and circular economy: Pathways to sustainable manufacturing,” Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 543–562, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee and, B. Bloomfield, Disorganizing through texts: The case of A.K. rice’s account of socio-technical systems theory. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Thewes, Bringing Socio-Technical Design Back to Its Roots: Improving Digitization in the Manufacturing Industry, vol. 1224 CCIS. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ingemarsdotter, E. Jamsin, G. Kortuem, and R. Balkenende, “Circular strategies enabled by the internet of things-a framework and analysis of current practice,” Sustainability Switzerland, vol. 11, no. 20, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ghoreishi, L. Treves, R. Teplov, and M. Pynnönen, The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Circular Value Creation for Sustainable Development Goals, vol. 152. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Klasen, D. J. Klasen, D. Gommers, J. C. Diehl, N. Hunfeld, and S. Rijcks, “Circular material flow of medication in the intensive care unit,” Crit Care, vol. 29, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Farsari, “Exploring the nexus between sustainable tourism governance, resilience and complexity research,” Tourism Recreation Research, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 352–367, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gavalas, “Identifying key elements for evaluating organizations’ complex adaptive leadership readiness (CAL-R framework): paving the way for a measurement tool development,” Journal of Management Development, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 87–102, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Chen, S. Mirzaliev, and W. Hao, “The economics of circular supply chains: Transformative implications for businesses and stakeholders,” J Clean Prod, vol. 513, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, A. Spieske, and H. Birkel, “The future of the circular economy and its effect on supply chain dependencies: Empirical evidence from a Delphi study,” Transp Res E Logist Transp Rev, vol. 157, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Bhaskar, “Optimizing Manufacturing Sector through Business Process Reengineering and Lean Integration: A B2Lean Methodology Approach,” Operations Research Forum, vol. 6, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Reynolds, N. M. Reynolds, N. Salter, Muranko, R. Nolan, and F. Charnley, “Product life extension behaviours for electrical appliances in UK households: Can consumer education help extend product life amid the cost-of-living crisis?,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 205, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Armstrong Soule and J. M. Ortega Egea, “Product lifespan extension of technology products: Exploring perceptions, value-beliefs, motives and attitudes in American and Spanish consumers,” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 81, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gróf and, T. Netland, “Overcoming the productivity challenge in product life-extending operations: a multiple-case study of European facilities,” Int J Prod Res, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Krych, D. B. Müller, and J. B. Pettersen, “The ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’ of product lifetimes in dynamic stock modeling,” J Ind Ecol, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 6–18, 2025. [CrossRef]

- V. Arioli, R. V. Arioli, R. Sala, F. Pirola, and G. Pezzotta, Simulation Applied in Product-Service System (PSS): System Dynamics Potentials of Supporting Sustainable PSS Development. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Atitebi, K. S. Atitebi, K. Dumre, and E. C. Jones, “Supporting a Lithium Circular Economy via Reverse Logistics: Improving the Preprocessing Stage of the Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling Supply Chain,” Energies (Basel), vol. 18, no. 3, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. H. Haghighat, B. M. Z. H. Haghighat, B. M. Fard, A. Islam, and H. Karimipour, “An explainable big transfer learning approach for IoT-based safety management in smart factories,” Internet of Things the Netherlands, vol. 31, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Rathi et al., “Realizing the potential of Internet of Things (IoT) in Industrial applications,” Discover Internet of Things, vol. 5, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Pellicer, F. Alarcón, and D. 239. 2025. [CrossRef]

- V. Piyathanavong, S. V. Piyathanavong, S. Olapiriyakul, V.-N. Huynh, J. A. Garza-Reyes, V. Kumar, and J. Karnjana, “Implementing Industry 4.0 and circular economy through the developmental culture perspective—Driving a competitive advantage in the manufacturing industry,” Bus Strategy Environ, vol. 33, no. 8, pp. 9059–9074, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ali, A. Y. Ali, A. Uddin, and A. Petrillo, “The impact of government support and organizational culture on sustainable performance: Unveiling the mediating role of circular economy and eco-innovation,” Sustainable Futures, vol. 8, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Singh et al., “Integrating Industry 4.0, Circular Economy, and Green HRM: A Framework for Sustainable Transformation,” Sustainability Switzerland, vol. 17, no. 7, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ijjasz-Vasquez, P. Karp, and M. Weber-Fahr, Communities of Practice at the World Bank: Breaking Knowledge Silos to Catalyze Culture Change and Organizational Transformation. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Khan, A. S. Khan, A. Haleem, and M. I. Khan, “Enablers to Implement Circular Initiatives in the Supply Chain: A Grey DEMATEL Method,” Global Business Review, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 68–84, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Cai, S. W. Cai, S. Gallani, and J.-E. Shin, “Incentive Effects of Subjective Allocations of Rewards and Penalties,” Manage Sci, vol. 69, no. 5, pp. 3121–3139, 2023. [CrossRef]

- An, Q. Zhang, and X. Tao, “Pay-for-performance incentives in benchmarking with quasi S-shaped technology,” Omega United Kingdom, vol. 118, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Sönnichsen, A. S. Sönnichsen, A. de Jong, J. Clement, R. Maull, and C. Voss, “The Circular Economy: A Transformative Service Perspective,” J Serv Res, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 228–245, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Verma, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Integration of methods for sustainability assessment of potentially circular processes – An innovative matrix framework for businesses and policymakers,” J Clean Prod, vol. 507, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Huang, K. Li, and A. Shrestha, “Organizational structure and dynamic capabilities on business model innovation in project-driven enterprises: evidence from the construction industry,” Engineering Construction and Architectural Management, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 578–600, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Heikinheimo, P. Hautamäki, S. Julkunen, and J. Koponen, “Dynamic capabilities and multi-sided platforms: Fostering organizational agility, flexibility, and resilience in B2B service ecosystems,” Industrial Marketing Management, vol. 125, pp. 179–194, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Schützenhofer, I. S. Schützenhofer, I. Kovacic, S. Mack, and H. Rechberger, “Improvement of Environmental Sustainability and Circular Economy through Construction Waste Management for Material Reuse,” Sustainability Switzerland, vol. 14, no. 17, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, Y. R. Glazer, D. M. Sassaman, M. E. Webber, and C. C. Seepersad, “Circularity: Understanding the Environmental Tradeoffs of Additive Manufacturing with Waste Plastics,” Recycling, vol. 9, no. 5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Housawi, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Evaluation of key performance indicators (Kpis) for sustainable postgraduate medical training: An opportunity for implementing an innovative approach to advance the quality of training programs at the saudi commission for health specialties (scfhs),” Sustainability Switzerland, vol. 12, no. 19, pp. 1–37, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Aguilar Esteva, A. C. Aguilar Esteva, A. Kasliwal, M. S. Kinzler, G. A. Keoleian, and H. C. Kim, “Circular economy framework for automobiles: Closing energy and material loops,” J Ind Ecol, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 877–889, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. Garcia de Soto, and H. Feng, “Revamping construction supply chain processes with circular economy strategies: A systematic literature review,” J Clean Prod, vol. 335, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Amankona, K. D. Amankona, K. Yi, L. Tweneboa Kodua, L. A. Odai, and E. A. Tackie, “Responsible Digital Innovation and Innovation Performance in Ghana’s High-Tech Industry: The Mediating Roles of Digital Organizational Culture and Strategy, and the Moderating Role of Digital Literacy,” Sage Open, vol. 15, no. 2, 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Amaral and C. De Muylder, “The relation between innovative behavior and culture of innovation in organizational performance: model and empirical study,” Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 766–781, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Malisić, S. B. Malisić, S. Tinaj, J. Popović, L. Lukovac, and B. Vlačić, “Internal dynamics and innovation: A cross-disciplinary review and future research agenda,” Technol Soc, vol. 81, 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Gelaw, D. K. T. Gelaw, D. K. Azene, and E. Berhan, “Assessment of critical success factors, barriers and initiatives of total productive maintenance (TPM) in selected Ethiopian manufacturing industries,” J Qual Maint Eng, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 51–80, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Klinkhammer, People and Organization in the CRM Competence Model: New Approaches to Organizational Development on the Way to a Customer-Centric Company, vol. Part F79. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. Hussain and A. Khan, Driving retail growth: The interplay of customer-centric technology, customer accountability and organisational culture. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lakhouit, “Revolutionizing urban solid waste management with AI and IoT: A review of smart solutions for waste collection, sorting, and recycling,” Results in Engineering, vol. 25, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Khulbe, AI’s role in the implementation of circular economy practices: Optimising product life cycles, promoting recycling and facilitating the reuse of materials. 2025.

- E. Faghih, Z. E. Faghih, Z. Saki, and M. Moore, “A Systematic Literature Review—AI-Enabled Textile Waste Sorting,” Sustainability Switzerland, vol. 17, no. 10, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Ravichandran, S. M. Ravichandran, S. Govindaswamy, J. Kandasamy, K. E. K. Vimal, V. Kumar, and O. Kulkarni, “Environment and economic analysis of reverse supply chain scenarios for remanufacturing using discrete-event simulation approach,” Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 10183–10224, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Zils, M. M. Zils, M. Howard, and P. Hopkinson, “Circular economy implementation in operations & supply chain management: Building a pathway to business transformation,” Production Planning and Control, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 501–520, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Hamida, H. M. B. Hamida, H. Remøy, V. Gruis, and T. Jylhä, “Circular building adaptability in adaptive reuse: multiple case studies in the Netherlands,” Journal of Engineering Design and Technology, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 161–183, 2025. [CrossRef]

- É. Marcon, N. F. É. Marcon, N. F. Ayala, A. G. Frank, M. Soliman, and T. Sturgeon, “A system view of how balancing sociotechnical factors in Industry 4.0 implementation: Evidence from interviews and ethnographic research,” Comput Ind Eng, vol. 203, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Alqoud, J. Milisavljevic-Syed, and D. Schaefer, “Industry 4.0: Challenges and Opportunities of Digitalisation Manufacturing Systems,” in Advances in Transdisciplinary Engineering, 2022, pp. 25–30. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Pham, “Green innovation and purchasing strategy: Mediators between top management commitment and competitive advantage,” International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 348–360, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mehri, F. Sabouhi, and S. F. Ghaderi, “Designing a sustainable and resilient biofuel supply chain considering the water-energy-land nexus: Towards a circular economy,” Energy, vol. 329, 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. N. Alfina, D. K. N. Alfina, D. Wibisono, M. H. Basri, N. B. Mulyono, and R. M. C. Ratnayake, “Enhancing resilience and sustainable healthcare supply chains: integrating circular economy and dynamic barrier management,” Discover Sustainability, vol. 6, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang et al., “Intent-Driven Closed-Loop Control and Management Framework for 6G Open RAN,” IEEE Internet Things J, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 6314–6327, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Leiva Vilaplana, G. J. A. Leiva Vilaplana, G. Yang, E. Ackom, R. Monaco, and Y. Xue, “Dynamic Cost–Benefit Analysis of Digitalization in the Energy Industry,” Engineering, vol. 45, pp. 174–187, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Barton, R. M. Barton, R. Budjac, P. Tanuska, G. Gaspar, and P. Schreiber, “Identification Overview of Industry 4.0 Essential Attributes and Resource-Limited Embedded Artificial-Intelligence-of-Things Devices for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises,” Applied Sciences Switzerland, vol. 12, no. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu and J. Sun, “Research on Digital Twin Information System Based on Big Data Smart City Information Model,” in 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Aided Education Iciscae 2023, 2023, pp. 900–904. [CrossRef]