1. Introduction

The global sustainability crisis requires profound transformations in how organizations operate, with growing recognition that incremental approaches are insufficient to address mounting environmental and social challenges (Hoffman, 2018; Schoenmaker & Schramade, 2019). Despite increasing commitment to sustainability among organizations across sectors, a persistent gap remains between sustainability aspirations and substantive action (Bromley & Powell, 2012; Milne & Gray, 2013). This gap presents both a practical problem and a theoretical puzzle: why do organizations struggle to translate sustainability commitments into transformative change, and what capabilities and mechanisms enable some organizations to overcome these challenges?

This research addresses this puzzle by investigating how organizations bridge the sustainability rhetoric-action gap through developing specific capabilities and integration mechanisms that enable substantive transformations. We move beyond existing research that has identified this gap (Boiral, 2007; Crilly et al., 2016) to examine the specific organizational practices and contextual conditions that allow organizations to overcome it.

The study addresses three critical research questions:

What organizational capabilities enable effective navigation of sustainability paradoxes and tensions?

How do organizations successfully integrate sustainability throughout their systems rather than compartmentalizing it?

How do power dynamics and contextual factors influence the effectiveness of sustainability transformation approaches?

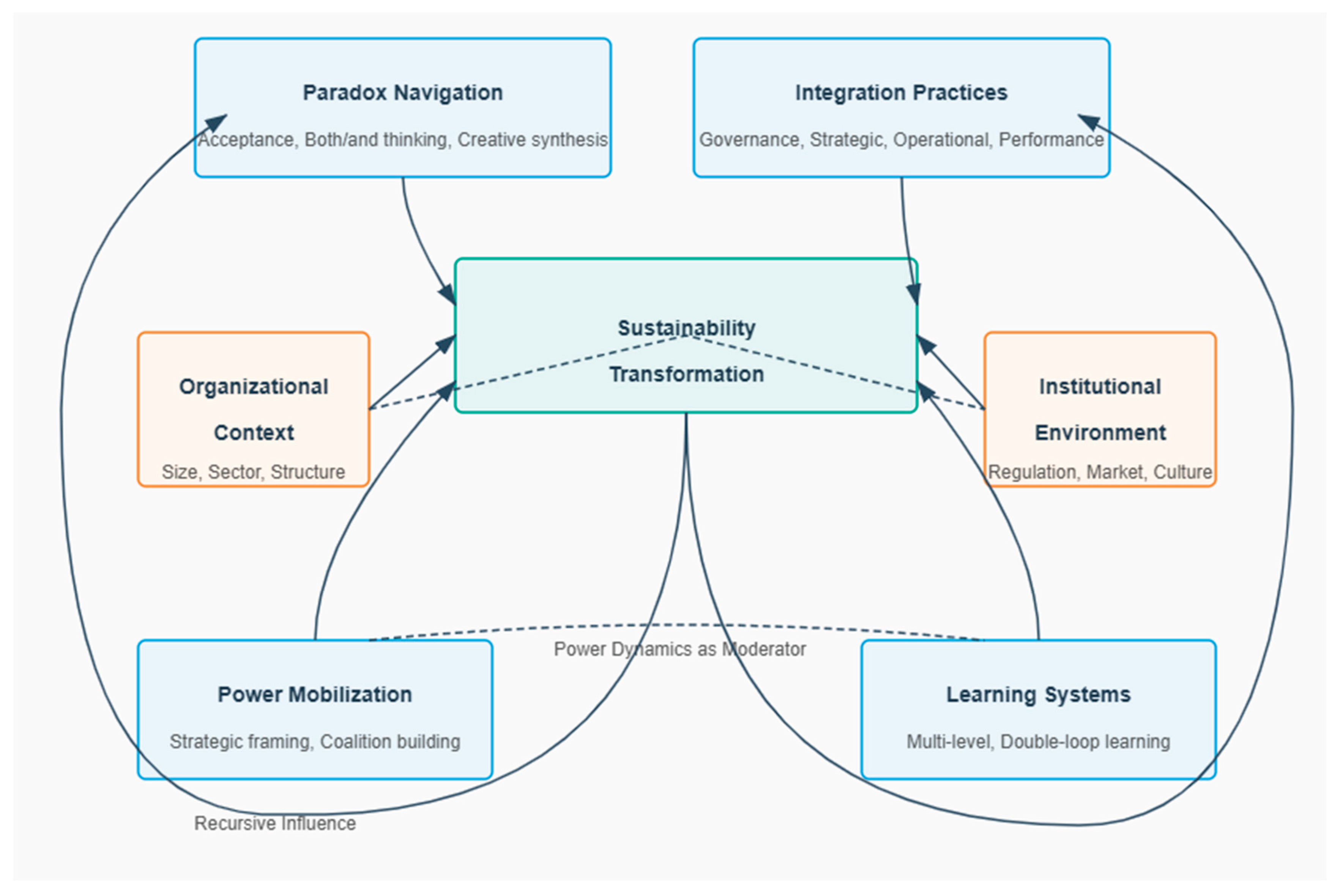

By examining these questions through a mixed-methods approach, this research contributes to sustainability science in three distinct ways. First, while paradox theory has emerged as an important lens for understanding sustainability challenges (Hahn et al., 2018; Van der Byl & Slawinski, 2015), empirical research examining how organizations develop and implement paradox navigation capabilities remains limited. This study provides empirical evidence of specific paradox navigation practices and their effectiveness across different organizational contexts.

Second, previous research has identified the importance of integrating sustainability into business models (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Slager et al., 2020), but has paid less attention to the specific integration mechanisms and their relative effectiveness across diverse organizational contexts. This research identifies four distinct integration mechanisms and demonstrates how they interact and evolve over time to create substantive transformation.

Third, while the importance of power in sustainability transformation has been acknowledged (Levy & Scully, 2007; Wright & Nyberg, 2017), existing research often treats power as a contextual variable rather than a central dynamic in transformation processes. This study directly examines how power relationships shape transformation processes and how change agents navigate and reshape power dynamics to advance sustainability.

The research aligns with the United Nations' 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2015), particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals), by identifying organizational practices that enable more sustainable production systems and effective sustainability governance. Through its empirically grounded examination of sustainability transformation processes across diverse organizational contexts, this research bridges micro-organizational and macro-institutional perspectives on sustainability challenges.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainability Paradoxes and Tensions

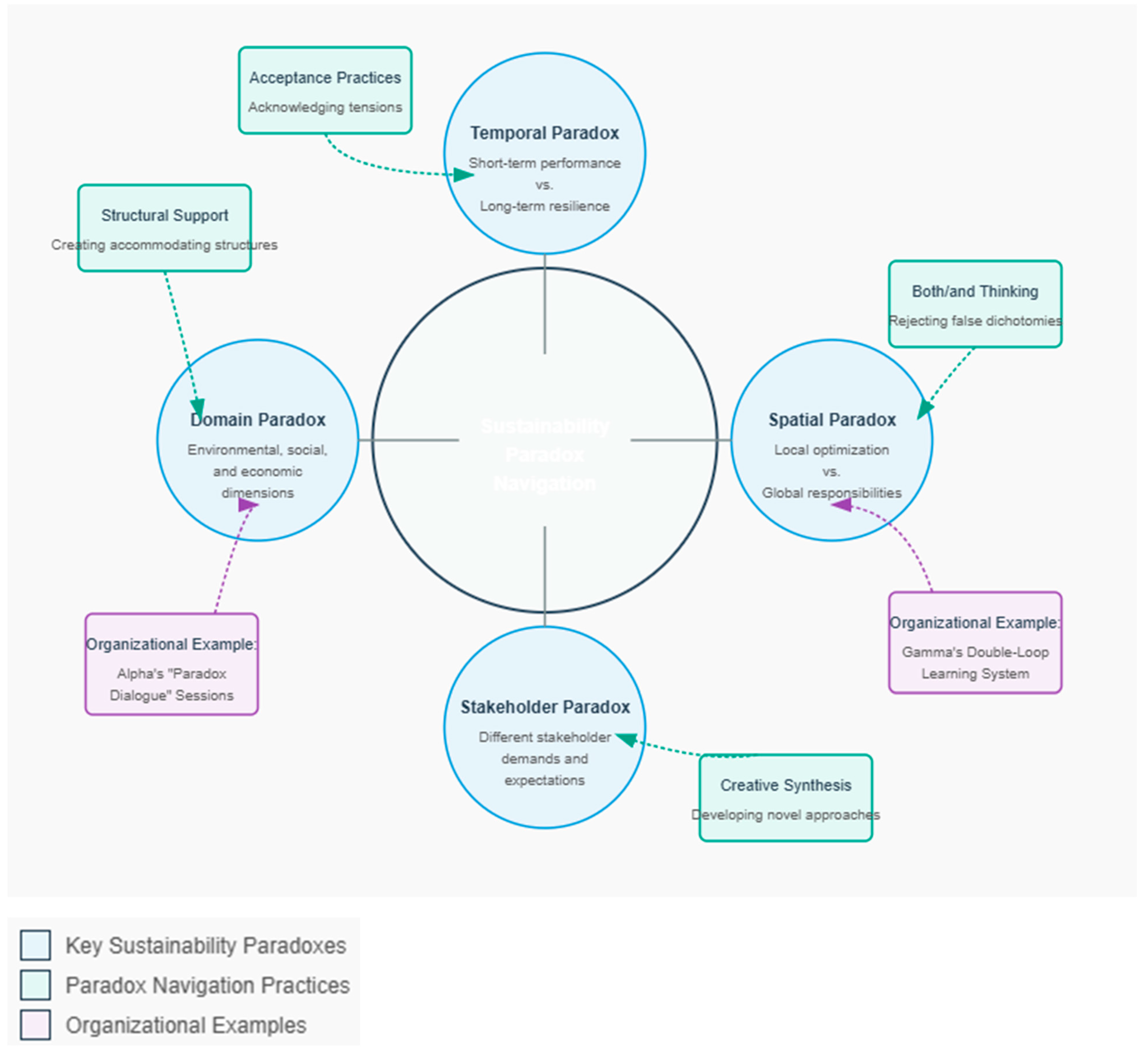

Sustainability inherently involves paradoxical tensions between competing objectives, timeframes, and stakeholder interests (Hahn et al., 2018; Sharma & Jaiswal, 2018). Rather than treating these tensions as problems to be resolved, paradox theory suggests they are enduring contradictions that must be continuously navigated (Smith & Lewis, 2011). Research by Hahn et al. (2018) identifies several recurring sustainability paradoxes:

Temporal paradoxes: Tensions between short-term performance and long-term resilience

Spatial paradoxes: Tensions between local optimization and global responsibilities

Stakeholder paradoxes: Tensions between different stakeholder demands and expectations

Domain paradoxes: Tensions between environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability

These paradoxes create significant challenges for organizations pursuing sustainability transformations, as they must find ways to accommodate competing demands without forcing false choices that ultimately undermine sustainability objectives (Jay, 2013). Organizations that develop capabilities for navigating these paradoxes may achieve more substantive sustainability transformations than those that seek to eliminate tensions through either/or approaches (Schad et al., 2016).

However, the paradox literature has limitations that this research addresses. First, while paradox theory offers conceptual frameworks for understanding tensions, it provides less guidance on the specific practices organizations use to navigate paradoxes in sustainability contexts. Second, paradox approaches have been criticized for potentially maintaining status quo power relations by accommodating rather than challenging unsustainable systems (Hahn & Figge, 2011). This research examines how paradox navigation interacts with power dynamics and broader system transformation.

2.2. Integration Mechanisms for Sustainability

While many organizations establish dedicated sustainability functions, research suggests that substantive transformation requires embedding sustainability throughout organizational systems rather than compartmentalizing it (Aguinis & Glavas, 2013; Gazzola et al., 2021). Integration mechanisms connect sustainability to core organizational processes, structures, and decisions, ensuring that sustainability considerations become integral to how the organization operates (Calabrese et al., 2018).

Eccles et al. (2014) demonstrated that organizations with higher levels of sustainability integration achieved superior environmental and social performance over time. Similarly, Calabrese et al. (2018) found that integration of sustainability into strategic decision-making enhanced both sustainability outcomes and organizational resilience. However, less is known about the specific integration mechanisms that are most effective across diverse organizational contexts and how these mechanisms develop and interact over time.

Integration approaches also vary in their transformative potential. Shallow integration may involve superficial incorporation of sustainability into existing structures without fundamentally changing organizational priorities or decision-making (Lozano et al., 2015). In contrast, deep integration involves reconceptualizing organizational purpose, governance, and operations around sustainability principles (Stubbs & Cocklin, 2008). This distinction is critical for understanding how integration mechanisms contribute to substantive transformation rather than symbolic adoption.

2.3. Power Dynamics in Sustainability Transformations

Power dynamics fundamentally shape sustainability transformations, determining which initiatives gain traction and whose interests are served (Levy & Scully, 2007; Wright & Nyberg, 2017). As Fleming and Spicer (2014) argue, power operates through multiple dimensions: episodic (direct influence), manipulative (agenda setting), domination (structural arrangements), and subjectification (identity formation). Each dimension affects how sustainability is conceptualized, prioritized, and implemented.

These power dimensions create both constraints and opportunities for sustainability transformation. Established power structures often privilege short-term economic interests over longer-term social and environmental considerations, creating resistance to substantive sustainability initiatives (Benn et al., 2014). At the same time, sustainability advocates can leverage various forms of power to challenge existing arrangements and create space for alternative approaches (Avelino & Rotmans, 2009).

Recent scholarship by Mahfooz et al. (2022) highlights how sustainability initiatives often face resistance when they challenge established power structures and interests. Successful change agents must therefore develop sophisticated political capabilities to navigate these power dynamics (Howard-Grenville et al., 2007). However, as Avelino (2021) observes, power in sustainability contexts is not merely constraining but also productive—enabling new coalitions, practices, and institutional arrangements.

This research extends existing power perspectives by examining the specific strategies sustainability advocates use to navigate and reshape power dynamics, and how these strategies interact with paradox navigation and integration mechanisms to enable transformation.

2.4. Organizational Learning for Sustainability

Sustainability challenges are characterized by complexity, uncertainty, and rapid evolution—requiring organizations to continuously adapt their understanding and approaches (Siebenhüner & Arnold, 2007). Effective learning for sustainability occurs at multiple levels: individual, group, organizational, and network (Preiser et al., 2017).

Building on Argyris and Schön's (1996) distinction between single and double-loop learning, Schaefer and Harvey (2000) argue that sustainability transformations require double-loop learning that questions fundamental assumptions and values. Yet many organizations remain trapped in single-loop learning that adjusts practices without challenging underlying logics. The conditions that enable double-loop learning for sustainability remain an important area for empirical investigation.

Learning for sustainability faces distinct challenges, including the complexity of sustainability issues, the need to integrate diverse knowledge types (scientific, local, indigenous), and the political nature of sustainability knowledge (whose knowledge counts and why) (Fazey et al., 2018). These challenges require organizations to develop specific learning capabilities that can accommodate multiple perspectives while enabling practical action.

This research examines how learning systems operate in sustainability transformation contexts, particularly how they interact with paradox navigation capabilities and integration mechanisms to enable or constrain substantive change.

2.5. Contextual Factors in Sustainability Transformation

Organizations operate within diverse contexts that significantly influence their sustainability approaches and outcomes. These contextual factors include regulatory environments, market dynamics, cultural contexts, and technological infrastructures (Scott, 2014). Research by Delmas and Toffel (2008) demonstrates that these institutional pressures significantly shape organizational sustainability responses, often more powerfully than internal factors alone.

These contextual factors create both constraints and opportunities for sustainability transformation. Regulatory requirements may establish minimum standards but rarely drive transformative change (Dahlmann et al., 2017). Market dynamics may incentivize sustainability innovation in some sectors while creating barriers in others (Schaltegger & Wagner, 2011). Cultural contexts shape societal expectations regarding sustainability and the legitimacy of different approaches (Hoffman & Jennings, 2015).

Recent scholarship has called for more nuanced understanding of how contextual factors influence sustainability transformations (Banerjee & Arjaliès, 2022; Slawinski et al., 2021). This research responds to these calls by examining how different organizational contexts (sector, size, ownership, geography) shape the effectiveness of sustainability approaches, challenging universal prescriptions and highlighting the importance of contextually-tailored strategies.

2.6. Institutional Logics and Competing Demands

Sustainability transformation often involves navigating competing institutional logics—the socially constructed patterns of practices, assumptions, values, and rules that provide meaning and shape behavior within organizational fields (Thornton et al., 2012). Organizations pursuing sustainability must navigate tensions between market logics (prioritizing efficiency and profit), community logics (emphasizing collective welfare), and ecological logics (valuing ecosystem health) (Dahlmann & Grosvold, 2017).

These competing logics create institutional complexity that organizations must navigate (Greenwood et al., 2011). Some organizations respond by compartmentalizing different logics, addressing each separately through specialized units or practices. Others develop hybrid approaches that integrate elements of multiple logics into new organizational forms and practices (Battilana & Dorado, 2010).

The institutional logics perspective complements paradox theory by situating organizational tensions within broader societal structures and meaning systems. While paradox theory emphasizes cognitive and organizational responses to tensions, institutional logics highlight how these tensions reflect deeper societal contradictions and power arrangements (Lounsbury & Wang, 2020).

This research examines how organizations navigate competing institutional logics in sustainability contexts, particularly how they develop capabilities to work across logics while implementing integration mechanisms that enable substantive transformation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Philosophy and Approach

This study adopts a critical realist perspective (Bhaskar, 1978), which recognizes that while organizational reality exists independently of our knowledge of it, understanding is always mediated by social constructions and power relationships. This perspective allows examination of both objective institutional conditions and subjective interpretations of these conditions by organizational actors, while maintaining awareness of the underlying power dynamics that shape these interpretations.

Critical realism is particularly appropriate for sustainability research because it accommodates both the biophysical realities of environmental challenges and the socially constructed nature of sustainability concepts and practices (Banerjee, 2011). It enables investigation of causal mechanisms while recognizing that these mechanisms operate within complex open systems where multiple factors interact.

The mixed-methods design reflects this philosophy by combining quantitative measurement of key relationships with qualitative exploration of the mechanisms and meanings that underlie these relationships. This approach enables both theory testing and theory building, recognizing that sustainability transformations involve both measurable outcomes and socially constructed processes.

3.2. Research Design

This study employed a sequential mixed-methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018) with three primary components:

Quantitative survey (n=234) of sustainability professionals across multiple sectors

Semi-structured interviews (n=42) with organizational change agents and leaders

Comparative case studies (n=6) of organizations demonstrating different transformation patterns

This design allowed for testing relationships between key variables quantitatively while developing deeper understanding of mechanisms and contexts through qualitative inquiry. The sequential approach enabled insights from each phase to inform subsequent data collection and analysis, enhancing integration between methods.

Following Teddlie and Tashakkori's (2009) taxonomy of mixed methods designs, our approach represents an explanatory sequential design where quantitative results informed qualitative inquiry, with an embedded component where qualitative data collection occurred within the case study phase to deepen understanding of organizational contexts.

3.3. Sampling and Participants

Survey participants were recruited through professional sustainability networks and stratified to ensure representation across sectors (manufacturing, services, public sector, non-profit), organizational sizes, and geographical regions. To mitigate selection bias toward sustainability leaders, we recruited participants from both sustainability-focused networks and general management associations.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of survey respondents.

Interview participants were selected using purposive sampling to capture diverse perspectives on sustainability transformation. Selection criteria included organizational role, transformation experience, and sector representation. To ensure representation of critical perspectives, we deliberately included participants from organizations at different stages of sustainability transformation, including those experiencing significant challenges. The interview sample included sustainability professionals (n=18), senior executives (n=12), middle managers (n=8), and external stakeholders (n=4).

Case study organizations were selected using theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007) to represent maximum variation across key dimensions: transformation approach (incremental vs. radical), institutional context (supportive vs. challenging), organizational type (incumbent vs. entrepreneurial), and sector (manufacturing, services, public, hybrid). This sampling approach allowed for cross-case comparison of how different organizational contexts influence sustainability transformation processes.

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the six case organizations.

3.4. Data Collection

Survey Instrument: The survey instrument included validated scales measuring key constructs, including paradox navigation capabilities, integration practices, power mobilization strategies, organizational learning mechanisms, and sustainability transformation outcomes. Each construct was measured using multiple items on 7-point Likert scales, adapted from existing measures where available and developed through a rigorous process of expert review and pilot testing where needed.

The instrument was pilot-tested with 15 sustainability professionals and refined based on their feedback. Cronbach's alpha for all scales exceeded 0.80, indicating good internal consistency.

Table 3 provides sample items for each key construct. The complete survey instrument is included in

Appendix A.

To address potential common method bias, we implemented procedural remedies following Podsakoff et al. (2003), including psychological separation of predictor and criterion variables, assurance of anonymity, and varied response formats. We also conducted Harman's single-factor test and common latent factor analysis to assess and control for common method variance.

Interviews: Semi-structured interviews lasting 60-90 minutes explored participants' experiences with sustainability transformation initiatives. The interview protocol addressed institutional enablers and barriers, strategies for navigating power dynamics, approaches to managing sustainability tensions, learning processes, and integration practices. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded for analysis.

To enhance trustworthiness, we employed member checking (sending interview summaries to participants for verification) and maintained reflexive memos documenting how researcher positionality might influence data collection and interpretation. The complete interview protocol is included in Appendix B.

Case Studies: For each case organization, multiple data sources were collected using a systematic protocol:

Interviews with diverse organizational members (6-8 per organization)

Internal documentation on sustainability initiatives

Public sustainability reports and communications (5 years of historical data)

Observational data from site visits and meetings (10-15 hours per organization)

Archival data on organizational history and context

This multi-source approach enabled triangulation of findings and reduced reliance on retrospective accounts. For each case, we developed a detailed chronology of sustainability initiatives, including both successful and unsuccessful efforts, to understand transformation processes over time.

3.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis: Survey data were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) to test relationships between constructs in the theoretical framework. Before hypothesis testing, measurement validation was conducted through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess convergent and discriminant validity of constructs.

Table 4 presents key measurement model statistics.

The structural model was specified based on the theoretical framework, with direct paths from all independent variables to transformation outcomes and interaction terms to test moderating relationships. Multigroup analysis compared path coefficients across sectors and organizational types to test for contextual differences.

Qualitative Analysis: Interview and case study data were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) with the following steps:

Initial coding using a preliminary coding scheme derived from the theoretical framework

Coding refinement through comparison and discussion among three researchers

Theme development organizing codes into potential themes and subthemes

Theme review in relation to coded extracts and the entire dataset

Theme definition with clear naming and identification of representative quotes

Cross-case analysis to identify patterns, similarities, and differences

The coding process combined deductive and inductive approaches, with initial codes derived from theory but allowing for emergent codes from the data.

Table 5 provides an overview of the final coding framework with example codes.

Integration: Quantitative and qualitative findings were integrated through a connecting approach (Fetters et al., 2013), with qualitative data explaining mechanisms underlying quantitative relationships and illuminating contextual contingencies. This integration enhanced the validity of findings through methodological triangulation while enabling a more nuanced understanding of complex causal mechanisms.

To systematize integration, we developed joint display matrices that explicitly linked quantitative relationships with qualitative explanations. We also conducted integrated analysis sessions where researchers collaboratively interpreted quantitative and qualitative results, identifying convergence, complementarity, and discordance between findings from different methods.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results: Relationships Between Key Constructs

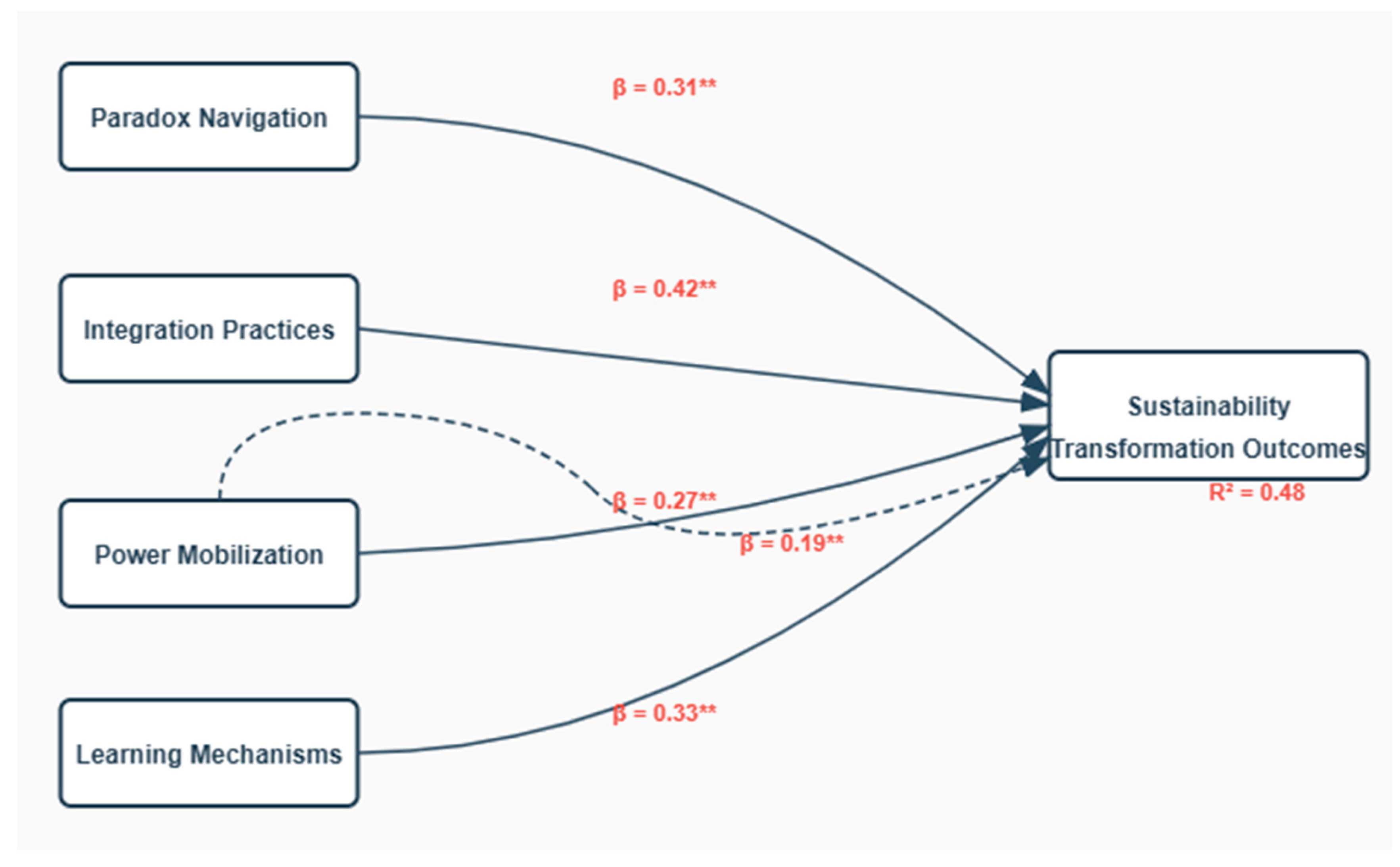

Structural equation modeling revealed significant relationships between key constructs in the theoretical framework (see

Table 6 and

Figure 1).

The model demonstrated good fit (CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.058, SRMR = 0.062) and explained 48% of variance in sustainability transformation outcomes. Notably, integration practices emerged as the strongest predictor of transformation outcomes (β = 0.42, p < 0.01, f² = 0.25), followed by learning mechanisms (β = 0.33, p < 0.01, f² = 0.16) and paradox navigation capabilities (β = 0.31, p < 0.01, f² = 0.15). The effect sizes indicate that integration practices have a medium to large practical significance, while most other predictors have medium effects.

A significant interaction effect was identified between power mobilization and integration practices (β = 0.19, p < 0.01, f² = 0.08). The effectiveness of integration practices was moderated by organizational power dynamics, with integration practices having stronger effects on transformation outcomes when power was more broadly distributed (less centralized) and when sustainability advocates had greater access to decision-making processes.

Figure 2 illustrates this interaction effect, showing how the relationship between integration practices and transformation outcomes varies at different levels of power mobilization.

Multigroup analysis revealed significant contextual differences in these relationships:

Sectoral differences: The relationship between paradox navigation and transformation outcomes was stronger in manufacturing (β = 0.38, p < 0.01) than services (β = 0.24, p < 0.05), suggesting that manufacturing organizations face more complex sustainability tensions requiring sophisticated navigation capabilities. Conversely, power mobilization had stronger effects in service organizations (β = 0.35, p < 0.01) than in manufacturing (β = 0.22, p < 0.05), reflecting the more relationship-based nature of service contexts.

Size differences: Paradox navigation capabilities had stronger effects in larger organizations (β = 0.37, p < 0.01) than smaller ones (β = 0.24, p < 0.05), suggesting that managing competing demands becomes more critical as organizational complexity increases. In contrast, integration practices showed more consistent effects across organizational sizes, indicating their fundamental importance regardless of scale.

Geographic differences: The effect of power mobilization on transformation outcomes was stronger in Asian organizations (β = 0.35, p < 0.01) than in North American (β = 0.22, p < 0.05) or European organizations (β = 0.25, p < 0.05), indicating important cultural variations in how power influences transformation processes. Learning mechanisms showed the most consistent effects across geographic contexts (β ranging from 0.30 to 0.36), suggesting the universal importance of learning capabilities.

Performance level differences: The relationship between paradox navigation and transformation outcomes was stronger for organizations at earlier stages of sustainability transformation (β = 0.39, p < 0.01) than for sustainability leaders (β = 0.26, p < 0.05). Conversely, integration practices had stronger effects for advanced organizations (β = 0.45, p < 0.01) than beginners (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), suggesting that different capabilities may be critical at different stages of transformation.

These contextual variations challenge universal prescriptions for sustainability transformation, highlighting instead the importance of tailoring approaches to specific organizational contexts and transformation stages.

4.2. Qualitative Findings: Mechanisms and Contextual Dynamics

Thematic analysis of interview and case study data revealed four key themes that illuminate the mechanisms underlying the quantitative results.

Table 7 presents a joint display integrating quantitative relationships with qualitative explanations.

4.2.1. Paradox Navigation in Practice

Organizations achieving substantive sustainability transformations developed structured approaches to paradox navigation rather than avoiding or eliminating tensions. Our findings revealed that paradox navigation involves both cognitive capabilities (recognizing and reframing tensions) and practical mechanisms (processes and structures that enable constructive engagement with tensions).

The most effective paradox navigation approaches included:

Acceptance practices: Acknowledging tensions without attempting to resolve them

Both/and thinking: Rejecting false dichotomies between competing objectives

Creative synthesis: Developing novel approaches that address multiple objectives simultaneously

Structural support: Creating organizational structures that accommodate complexity

Case study data revealed significant differences in paradox navigation capabilities across organizations. Alpha (Consumer Goods) institutionalized paradox navigation through formal processes:

"Alpha created dedicated 'paradox dialogue' sessions where cross-functional teams explicitly discussed tensions between competing sustainability objectives. These structured conversations transformed how the organization approached sustainability decisions, moving from either/or thinking to both/and innovation." (Case Study Analysis)

In contrast, Beta (Manufacturing) consistently framed sustainability decisions as either/or choices, leading to oscillation between priorities rather than integrated solutions:

"Beta's approach was characterized by pendulum swings between financial and sustainability priorities. When business conditions were favorable, sustainability initiatives advanced; when pressures increased, they were quickly sacrificed. This oscillation prevented the development of integrated approaches that could advance both objectives simultaneously." (Case Study Analysis)

The qualitative data also revealed that effective paradox navigation isn't merely cognitive but requires emotional capabilities:

"The hardest part isn't intellectual—it's emotional. People get uncomfortable with ambiguity and contradictions. We've had to develop emotional capacity to sit with that discomfort rather than rushing to eliminate tensions through premature either/or decisions." (Participant 37, Non-profit)

This emotional dimension helps explain why paradox navigation capabilities develop unevenly across organizations and why structural supports are necessary to sustain paradoxical thinking in the face of discomfort and uncertainty.

However, paradox navigation also showed limitations in addressing systemic sustainability challenges. While it enabled more creative approaches to organizational tensions, some participants noted that certain sustainability challenges require more radical system change rather than paradoxical accommodation:

"There are times when we need to recognize that some business models are fundamentally unsustainable and require transformation rather than optimization. Paradoxical thinking helps us navigate transitions, but shouldn't prevent us from acknowledging when deeper change is needed." (Participant 8, Sustainability Consultant)

This critique highlights the importance of complementing paradox navigation with critical reflection on system boundaries and transformation horizons.

4.2.2. Integration Mechanisms and Their Effectiveness

The qualitative data explained why integration practices emerged as the strongest predictor of transformation outcomes in the quantitative analysis. Organizations achieving substantial transformation embedded sustainability considerations into core business processes rather than treating sustainability as a specialized function.

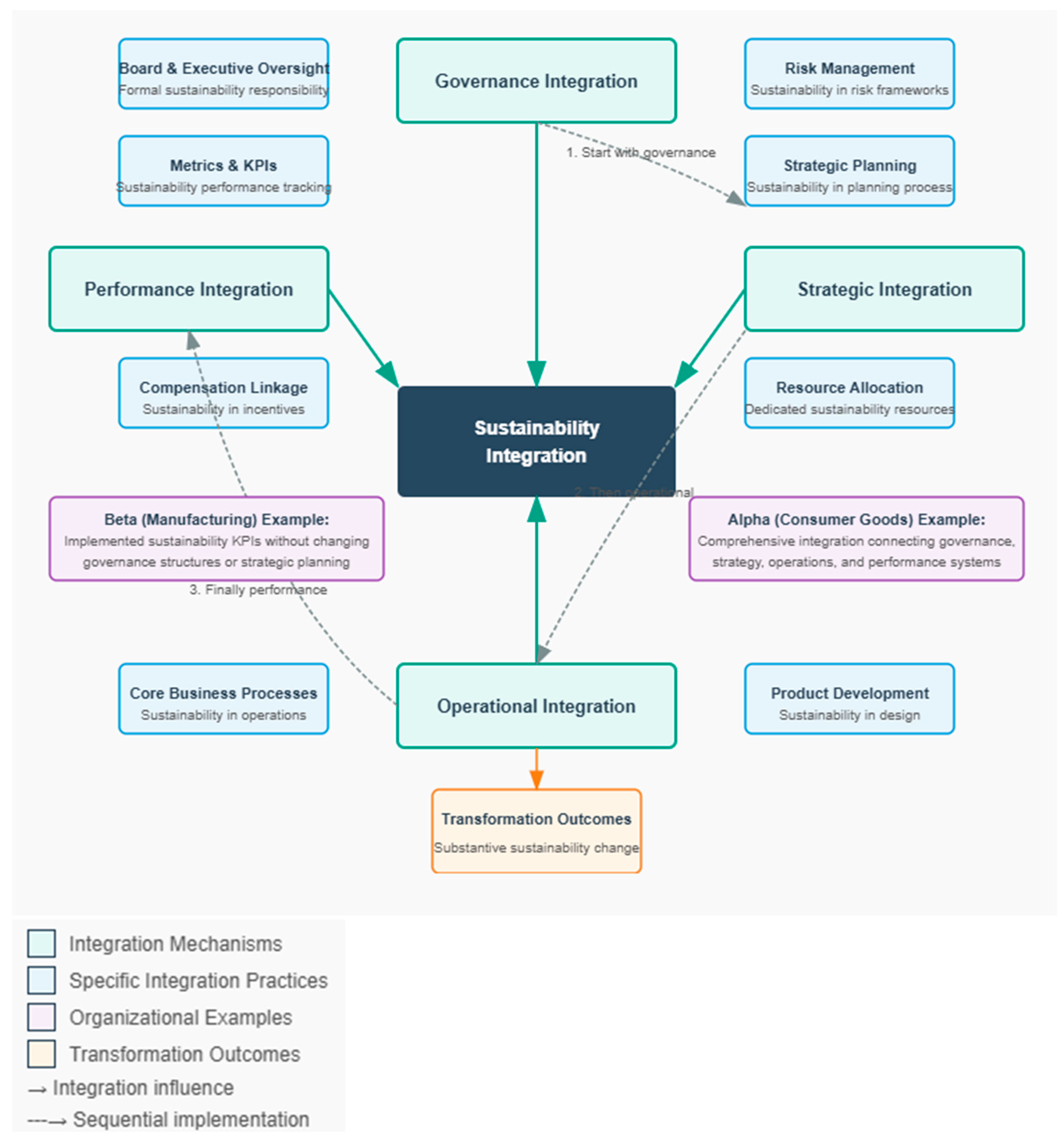

Figure 4.

Integration Mechanisms for Embedding Sustainability.

Figure 4.

Integration Mechanisms for Embedding Sustainability.

Effective integration mechanisms included:

Governance integration: Sustainability oversight at board and executive levels

Strategic integration: Sustainability embedded in strategic planning and goal-setting

Operational integration: Sustainability incorporated into core business processes

Performance integration: Sustainability metrics linked to compensation and advancement

Case study data revealed that these integration mechanisms were most effective when implemented as coordinated systems rather than isolated practices. This was particularly evident in the contrast between Alpha and Beta:

"Alpha implemented a comprehensive integration approach that connected governance, strategy, operations, and performance systems. Sustainability considerations flowed coherently from board-level discussions through strategic planning and into operational decisions. In contrast, Beta implemented sustainability KPIs without changing governance structures or strategic planning processes, resulting in disconnected initiatives that struggled to gain traction." (Case Study Analysis)

The temporal sequence of integration also emerged as important. Gamma (Financial Services) found that beginning with strategic integration created a foundation for subsequent operational changes:

"We started by integrating sustainability into our strategic planning process. This created the mandate for operational changes, which then required performance metrics to drive accountability. Trying to implement performance metrics without the strategic foundation didn't work." (Gamma, Executive)

This finding aligns with the quantitative result showing stronger effects of integration in more advanced organizations, suggesting that integration creates compound benefits as it matures and expands throughout organizational systems.

Our analysis also revealed different integration pathways across organizational types. While large incumbents typically pursued formal integration through established management systems, entrepreneurial organizations often built integrated approaches from inception:

"As a purpose-driven startup, we didn't need to integrate sustainability into our existing systems—we designed our systems around sustainability from the beginning. Our challenge wasn't integration but maintaining this integrated approach as we scaled." (Epsilon, Founder)

These different pathways highlight the importance of tailoring integration approaches to organizational context rather than applying universal best practices.

Integration also faced significant implementation challenges, particularly in organizations with complex legacy systems or significant internal resistance:

"The hardest part of integration wasn't the technical aspects but overcoming entrenched interests and established routines. We had to recognize that integration isn't just a structural challenge but a political and cultural one." (Delta, Sustainability Director)

This observation connects integration practices to power dynamics, explaining the significant interaction effect found in the quantitative analysis.

4.2.3. Power Dynamics in Transformation Processes

Change agents consistently identified power dynamics as critical to transformation outcomes. Our analysis revealed that power operates through multiple dimensions in sustainability contexts, including formal authority, resource control, expertise, and discursive influence. Successful change agents developed sophisticated capabilities for navigating these different power dimensions.

As one sustainability director explained:

"Understanding the power landscape is essential. I've learned to map who has decision-making authority, who influences those decision-makers, and who might resist change. This mapping helps me develop targeted strategies for different stakeholders." (Participant 7, Manufacturing)

Successful change agents employed various strategies to navigate power dynamics:

Strategic framing: Articulating sustainability in terms that resonated with powerful stakeholders' priorities

Coalition building: Creating networks of support across organizational boundaries

Resource mobilization: Securing financial, human, and symbolic resources

Timing exploitation: Identifying and leveraging windows of opportunity

These strategies were particularly important in organizations where sustainability values weren't deeply institutionalized:

"In our organization, sustainability isn't yet part of the core business model. I have to be strategic about when and how I introduce sustainability considerations. I've found that connecting them to cost savings, risk reduction, or customer expectations gets much more traction than environmental arguments alone." (Participant 23, Financial Services)

The qualitative data also revealed that power dynamics weren't static but evolved throughout transformation processes. As initiatives demonstrated value, sustainability advocates often gained additional influence:

"Five years ago, we were begging for a seat at the table. Now business units come to us proactively because they've seen how sustainability initiatives create value. Success has given us credibility and influence we didn't have before." (Participant 15, Manufacturing)

This temporal evolution helps explain the quantitative finding that power mobilization has different effects across organizational contexts. In some contexts, power mobilization is critical for initiating transformation; in others, it becomes more important for maintaining momentum and overcoming resistance.

Our analysis also revealed significant power asymmetries that constrained transformation, particularly regarding global supply chains and relationships with marginalized stakeholders:

"We've made progress internally, but our most significant sustainability impacts are in our supply chain where our influence is limited. Building power to affect these broader systems remains our biggest challenge." (Participant 29, Retail)

These persistent power asymmetries highlight limitations in current sustainability approaches and point to the need for more systemic transformation strategies that address fundamental power structures.

4.2.4. Learning Systems for Sustainability

Organizations with strong transformation outcomes implemented systematic approaches to learning that connected individual, group, and organizational levels. Our analysis revealed that effective learning for sustainability differs from conventional organizational learning in its integration of diverse knowledge types, explicit attention to power dynamics, and focus on system transformation.

"We've developed a multi-level learning system for sustainability. Individual employees participate in sustainability training and have personal development goals. Teams have regular reflection sessions to discuss what's working and what isn't. At the organizational level, we have quarterly reviews where we assess overall progress and adjust our approach." (Participant 31, Healthcare)

Effective learning systems included:

Psychological safety: Creating environments where people felt safe discussing failures

Feedback mechanisms: Developing robust approaches to monitoring and assessment

Reflection practices: Institutionalizing regular reflection on experience

Knowledge management: Creating systems to capture and share learning

Delta (Healthcare) demonstrated a particularly robust learning system:

"Delta implemented a formal 'sustainability learning cycle' with quarterly review and reflection processes. Each review examined outcomes against goals, identified barriers to progress, and generated insights for improvement. These insights were documented in a knowledge management system accessible to all employees and incorporated into future planning." (Case Study Analysis)

The case studies revealed that double-loop learning—questioning fundamental assumptions—was particularly important for transformative change. Gamma (Financial Services) demonstrated this approach:

"When our initial sustainability efforts produced limited results, we didn't just adjust our methods—we questioned our underlying assumptions about the relationship between sustainability and our business model. This deeper reflection led to fundamental changes in how we defined our purpose and strategy, enabling much more significant transformation." (Gamma, Executive)

This finding helps explain the strong quantitative relationship between learning mechanisms and transformation outcomes. Organizations that developed robust learning systems were able to continuously adapt their approaches based on experience, accelerating transformation over time.

However, our analysis also revealed significant barriers to effective learning, including time pressures, defensive routines, and power dynamics that constrained open dialogue:

"The biggest barrier to learning isn't lack of information but lack of time and space for reflection. When everyone is focused on delivering results, stepping back to question assumptions becomes a luxury few can afford." (Participant 4, Consulting)

These barriers were particularly evident in organizations facing significant market pressures or operating in turbulent environments, highlighting the tension between short-term performance demands and the reflective practices necessary for transformative learning.

4.3. Contextual Contingencies of Transformation

The qualitative data revealed significant contextual contingencies that explained variation in quantitative relationships across organizational types and sectors. These contingencies highlight how sustainability transformation approaches must be tailored to specific contexts rather than following universal prescriptions.

The qualitative data revealed how these contextual factors shaped transformation approaches. Ownership structure significantly influenced transformation pathways, with publicly traded companies facing distinct challenges:

"As a public company, quarterly earnings pressure creates a constant tension with longer-term sustainability investments. We've had to develop specific approaches to manage this tension, including dedicated innovation funds that protect longer-term initiatives from short-term pressures." (Alpha, Executive)

In contrast, Epsilon's social enterprise structure created different dynamics:

"Our legal structure as a benefit corporation fundamentally shapes our approach to sustainability. It's built into our governance, with directors legally required to consider social and environmental impacts alongside financial returns. This creates institutional support for sustainability that most conventional companies lack." (Epsilon, Director)

Sectoral dynamics created distinct transformation pathways. Manufacturing organizations typically emphasized operational efficiency and product innovation:

"In manufacturing, our sustainability transformation focused heavily on resource efficiency, circular material flows, and product redesign. These tangible aspects provided clear business cases that helped overcome resistance." (Beta, Manager)

Service organizations, by contrast, focused more on human capital and digital transformation:

"As a service business, our biggest sustainability impacts relate to our people and our digital infrastructure. Our transformation emphasized employee well-being, inclusive culture, and digital technologies that reduce environmental impact while enhancing service quality." (Gamma, Director)

Figure 5.

Contextual Contingencies of Sustainability Transformation.

Figure 5.

Contextual Contingencies of Sustainability Transformation.

Key Insights:

Large incumbents benefit most from learning systems but struggle with integration practices

Entrepreneurial organizations excel at integration but face challenges with power mobilization

B2C sectors show high effectiveness with power mobilization strategies, leveraging consumer pressure

Global organizations require strong learning systems and power mobilization to manage complexity

Paradox navigation is most effective in public sector contexts where multiple stakeholder demands are common

Geographic and cultural contexts also shaped transformation approaches:

"In our Asian operations, hierarchical cultural norms significantly influence how sustainability initiatives must be introduced and implemented. Leadership endorsement is essential, and initiatives must respect hierarchical structures while still enabling participation." (Participant 39, Manufacturing)

These contextual contingencies help explain the quantitative finding that different capabilities have varying effects across organizational contexts. They also highlight the importance of tailoring sustainability approaches to specific contexts rather than applying universal best practices.

4.4. Temporal Dynamics of Transformation

Our longitudinal case studies revealed important temporal dynamics in sustainability transformation processes that help explain the quantitative relationships between capabilities and outcomes. These dynamics included capability development pathways, transformation phases, and evolution of integration mechanisms over time.

Capability development followed different pathways across organizations. In some cases, paradox navigation capabilities developed first, creating foundation for subsequent integration:

"We had to develop comfort with sustainability tensions before we could effectively integrate sustainability into our systems. Attempts at integration without this foundation created resistance and superficial implementation." (Alpha, Manager)

In other cases, initial integration efforts catalyzed development of paradox navigation capabilities:

"As we began integrating sustainability metrics into performance reviews, tensions became visible that had previously been hidden. This forced us to develop better approaches to navigating these tensions." (Delta, HR Director)

These different pathways suggest that while the quantitative model identified relationships between capabilities and outcomes, these relationships may operate through different causal sequences depending on organizational context and history.

Transformation processes also displayed distinct phases, with different capabilities proving critical at different stages:

"In early phases, power mobilization was essential for getting sustainability on the agenda. In middle phases, paradox navigation became critical as we encountered complex implementation challenges. In later phases, integration mechanisms became most important for embedding sustainability into how we operate." (Gamma, Sustainability Director)

This phased progression helps explain the quantitative finding that paradox navigation had stronger effects for organizations at earlier transformation stages, while integration had stronger effects for more advanced organizations.

Integration mechanisms also evolved over time, typically beginning with isolated practices before developing into more coordinated systems:

"Our integration journey began with individual champions integrating sustainability into their specific domains. Over time, these isolated efforts connected into more systematic approaches, creating reinforcing cycles across governance, strategy, operations, and performance systems." (Alpha, Executive)

This evolution helps explain the stronger quantitative effects of integration in more advanced organizations, as integration benefits compound as practices become more coordinated and comprehensive.

5. Discussion

5.1. Paradox Navigation as a Core Sustainability Capability

This research contributes to sustainability science by empirically demonstrating the relationship between paradox navigation capabilities and transformation outcomes. Organizations that develop structured approaches to engaging with sustainability tensions achieve better outcomes than those seeking to eliminate these tensions or force false choices. This finding supports Smith and Lewis's (2011) dynamic equilibrium model of organizing but extends it by identifying specific practices that enable productive engagement with paradoxes in sustainability contexts.

The significant relationship between paradox navigation capabilities and transformation outcomes (β=0.31, p<0.01) provides empirical support for theoretical arguments about the importance of paradox approaches to sustainability (Hahn et al., 2018; Van der Byl & Slawinski, 2015). The qualitative findings extend this understanding by revealing specific mechanisms through which organizations develop and institutionalize paradox navigation capabilities, including acceptance practices, both/and thinking, creative synthesis, and structural support.

Our findings advance paradox theory in three important ways. First, we move beyond conceptual models of paradox types to identify specific practices organizations use to navigate these paradoxes in sustainability contexts. This practical focus provides a bridge between abstract paradox theory and concrete organizational challenges.

Second, we demonstrate that paradox navigation requires both cognitive capabilities (ways of thinking about tensions) and structural supports (processes and systems that enable engagement with tensions). This dual nature helps explain why paradox capabilities develop unevenly across organizations and points to potential development pathways.

Third, we identify important boundary conditions for paradox approaches, showing how their effectiveness varies across organizational contexts and transformation stages. The stronger relationship between paradox navigation and transformation outcomes in manufacturing organizations and in earlier transformation stages suggests that paradox capabilities may be particularly important in contexts with more visible tensions and less established sustainability approaches.

These contributions have important implications for sustainability science, suggesting that addressing complex sustainability challenges requires approaches that accommodate rather than eliminate tensions. By developing capabilities to work productively with sustainability paradoxes, organizations may achieve more substantive transformations that address multiple objectives simultaneously rather than privileging certain sustainability dimensions over others.

However, our findings also suggest potential limitations of paradox approaches for sustainability transformation. While paradox navigation enables more creative solutions to organizational tensions, it may not adequately address fundamental system contradictions that require more radical transformation. This critique aligns with concerns raised by Hahn and Figge (2011) that paradox approaches may inadvertently sustain unsustainable systems by accommodating rather than challenging their fundamental contradictions.

Future research should investigate this tension between paradoxical accommodation and system transformation, examining how organizations might combine paradox navigation with more radical approaches to address systemic sustainability challenges.

5.2. Integration Mechanisms for Embedding Sustainability

The findings identify integration practices as the strongest predictor of sustainability transformation outcomes (β=0.42, p<0.01), demonstrating the importance of embedding sustainability throughout organizational systems rather than treating it as a specialized function. This research advances understanding of sustainability integration by identifying four specific integration mechanisms—governance, strategic, operational, and performance integration—and demonstrating their collective importance for substantive transformation.

This contribution extends previous research on sustainability integration (Aguinis & Glavas, 2013; Eccles et al., 2014) in several important ways. First, we specify the mechanisms through which integration occurs and demonstrate their relative effectiveness across diverse organizational contexts. Our finding that integration practices have more consistent effects across organizational sizes than other capabilities suggests their fundamental importance regardless of scale.

Second, our qualitative findings reveal that these mechanisms are most effective when implemented as coordinated systems rather than isolated practices, with strategic integration typically preceding operational and performance integration. This sequential understanding advances previous research that has often treated integration as a static condition rather than a developmental process.

Third, our identification of different integration pathways across organizational types—formal systems integration in incumbents versus built-in integration in entrepreneurial organizations—highlights the importance of contextually-tailored integration approaches. This finding challenges universal prescriptions for sustainability integration and suggests that effective approaches must align with organizational history and structure.

The significant interaction between power mobilization and integration practices (β=0.19, p<0.01) demonstrates that structural interventions are insufficient without attention to power relationships. This finding extends previous research by highlighting the importance of addressing both structural and political dimensions of sustainability integration.

These contributions have important implications for sustainability science, suggesting that addressing the gap between sustainability rhetoric and substantive action requires comprehensive integration approaches that embed sustainability throughout organizational systems. By implementing coordinated integration mechanisms that evolve over time, organizations may overcome the compartmentalization that often limits sustainability impact.

However, our findings also reveal potential limitations of integration approaches. While integration can embed sustainability within existing organizational systems, it may struggle to transform those systems when they are fundamentally misaligned with sustainability principles. This limitation was particularly evident in organizations with business models that create inherent tensions with sustainability objectives.

Future research should investigate how integration approaches might be combined with more transformative strategies that question and reshape underlying business models and organizational purposes. Such research could help address the tension between embedding sustainability within existing systems and transforming those systems to be inherently more sustainable.

5.3. Power Dynamics and Sustainability Transformation

This research advances understanding of power in sustainability transformations by demonstrating how power operates as both a constraint and enabler of change. The findings reveal that power mobilization has a significant direct effect on transformation outcomes (β=0.27, p<0.01) and moderates the effectiveness of integration practices.

The qualitative findings extend theoretical understanding of power in sustainability contexts (Avelino, 2021; Levy & Scully, 2007) in three important ways. First, we identify specific strategies through which change agents navigate and reshape power relationships to advance sustainability initiatives. These strategies—strategic framing, coalition building, resource mobilization, and timing exploitation—provide practical approaches for working with power rather than simply analyzing it as a structural constraint.

Second, our findings reveal how power dynamics evolve throughout transformation processes, with sustainability advocates gaining influence as they demonstrate value and build coalitions. This temporal dimension adds nuance to existing theoretical perspectives (Fleming & Spicer, 2014) by highlighting the dynamic nature of power relationships in sustainability transformations.

Third, our identification of persistent power asymmetries that constrain transformation, particularly regarding global supply chains and marginalized stakeholders, highlights limitations in current sustainability approaches. This finding contributes to critical perspectives on sustainability by demonstrating how power structures may undermine transformative potential.

The varying effects of power mobilization across organizational contexts—stronger in service organizations (β = 0.35) than manufacturing (β = 0.22) and stronger in Asian organizations (β = 0.35) than North American (β = 0.22) or European (β = 0.25)—highlight how power operates differently across contexts. These differences suggest that power-conscious approaches to sustainability must be tailored to specific cultural and sectoral dynamics.

These contributions have important implications for sustainability science, suggesting that addressing power dynamics is essential for substantive sustainability transformation. By developing power-conscious approaches that navigate and reshape power relationships, change agents may overcome resistance and create conditions more conducive to sustainability innovations.

However, our findings also suggest limitations in current approaches to power in sustainability contexts. While organizational change agents can navigate power dynamics to advance sustainability within organizational boundaries, their ability to address broader systemic power arrangements remains limited. This constraint highlights the need for multi-level approaches that connect organizational change with broader system transformation.

Future research should investigate how organizational power dynamics interact with broader power structures in society, and how change agents might work across these levels to create more fundamental sustainability transformations. Such research could help address the tension between working within existing power structures and transforming those structures to enable more sustainable futures.

5.4. Contextual Contingencies and Tailored Sustainability Approaches

This research advances understanding of contextual contingencies in sustainability transformation by demonstrating significant differences in relationships across sectors, sizes, and geographic contexts. The typology of transformation patterns across organizational contexts (

Table 8) provides a foundation for more nuanced theoretical models that recognize contextual variation while identifying common principles.

This contribution responds to calls for more contextualized understanding of sustainability transformations (Banerjee & Arjaliès, 2022; Slawinski et al., 2021) in several important ways. First, our empirical demonstration of how organizational context shapes both the process and outcomes of transformation challenges universal prescriptions for sustainability transformation and suggests the need for contextually tailored approaches.

Second, our identification of different transformation pathways across organizational types—systematic integration in large incumbents, purpose-driven approaches in entrepreneurial organizations, policy-driven change in public sector, brand-driven initiatives in B2C sectors, and client-driven approaches in B2B sectors—highlights how context shapes not only the effectiveness of specific practices but the overall transformation approach.

Third, our finding that different capabilities have varying effects across organizational contexts—paradox navigation more important in manufacturing, power mobilization more important in services—provides empirical support for contingency perspectives on sustainability capabilities. This finding suggests that capability development should prioritize different areas depending on organizational context.

The quantitative finding that different capabilities have varying effects at different transformation stages—paradox navigation more important at earlier stages, integration more important at later stages—further highlights the dynamic nature of contextual contingencies. This temporal dimension suggests that sustainability approaches should evolve as organizations progress in their transformation journeys.

These contributions have important implications for sustainability science, suggesting that effective sustainability approaches are not universal but must be adapted to specific contextual conditions. By developing context-sensitive transformation strategies, organizations may achieve more substantive sustainability outcomes that address their particular sustainability challenges and opportunities.

However, our findings also suggest potential limitations of overly contextual approaches. While tailoring is important, certain principles—such as the importance of integration mechanisms and learning systems—showed relatively consistent effects across contexts. This consistency suggests the existence of common principles that transcend contextual variation.

Future research should further investigate the balance between contextual adaptation and universal principles in sustainability transformation, seeking to identify which aspects of transformation require tailoring and which remain consistent across contexts. Such research could help develop more nuanced frameworks that guide contextual adaptation while maintaining core transformation principles.

5.5. Institutional Logics and Competing Demands

Our findings contribute to institutional theory by demonstrating how organizations navigate competing institutional logics in sustainability contexts. The paradox navigation capabilities identified in our research represent practical approaches to managing institutional complexity, while integration mechanisms provide structural supports for working across logics.

Organizations achieving substantive sustainability transformations developed capabilities to work across market, community, and ecological logics rather than privileging one logic or compartmentalizing them. As one executive explained:

"We had to move beyond seeing business and sustainability as separate worlds with different rules. Success required integrating market thinking with ecological understanding and community perspectives into a coherent approach that draws from all three." (Alpha, Executive)

This integration of logics aligns with recent work on institutional hybridization (Battilana & Lee, 2014) but extends it by identifying specific practices organizations use to create hybrid approaches in sustainability contexts. Our findings suggest that successful hybridization requires both cognitive capabilities (paradox navigation) and structural supports (integration mechanisms).

The varying effects of paradox navigation across organizational contexts may reflect different levels of institutional complexity. Manufacturing organizations, which showed stronger effects for paradox navigation (β = 0.38, p < 0.01), typically face more complex material trade-offs and competing stakeholder demands than service organizations (β = 0.24, p < 0.05).

These contributions have important implications for institutional theory, suggesting that organizations can develop specific capabilities for managing institutional complexity rather than being passive recipients of institutional pressures. By developing paradox navigation capabilities and implementing integration mechanisms, organizations may create novel hybrid arrangements that advance sustainability while maintaining legitimacy across diverse institutional domains.

Future research should further investigate how institutional logics shape sustainability transformation processes, particularly how organizations might reshape rather than merely navigate institutional arrangements. Such research could help address the tension between working within existing institutional frameworks and transforming those frameworks to enable more sustainable futures.

5.6. Practical Implications for Sustainable Organizations

The findings have several practical implications for organizations seeking to advance sustainability transformations:

Develop paradox navigation capabilities: Organizations should create processes and structures that enable productive engagement with sustainability tensions rather than seeking to eliminate these tensions or force false choices. Specific approaches include establishing formal dialogue processes that explicitly surface and explore tensions, training leaders in both/and thinking, creating decision frameworks that accommodate multiple criteria, and designing organizational structures that allow for simultaneous attention to competing demands. These approaches should be tailored to organizational context, with manufacturing organizations particularly benefiting from structured paradox navigation processes.

Implement comprehensive integration mechanisms: Organizations should focus on embedding sustainability considerations into core business processes rather than creating isolated sustainability functions. This requires attention to four dimensions: governance integration (board and executive oversight), strategic integration (sustainability in planning and goal-setting), operational integration (sustainability in core processes), and performance integration (sustainability metrics linked to compensation). These dimensions should be implemented as a coordinated system rather than isolated initiatives, with strategic integration typically preceding operational and performance integration.

Address power dynamics: Sustainability leaders should map the power landscape to identify key decision-makers, influencers, and potential allies; develop tailored influence strategies for different stakeholders; build coalitions that enhance collective influence; frame sustainability initiatives in ways that align with powerful stakeholders' priorities; and create structural changes that institutionalize sustainability influence. These power-conscious approaches should be adapted to cultural context, with particular attention to hierarchical dynamics in Asian contexts and relationship networks in service organizations.

Develop multi-level learning systems: Organizations should invest in learning systems that connect individual, group, and organizational learning around sustainability challenges. Effective learning systems include psychological safety mechanisms, regular reflection processes, knowledge management systems, and governance structures that incorporate learning into strategic decisions. These systems should emphasize double-loop learning that questions fundamental assumptions rather than merely adjusting existing approaches.

Tailor approaches to context: Organizations should adapt transformation strategies based on their sector, size, history, and institutional position rather than adopting generic best practices. The typology of transformation patterns (

Table 8) provides guidance for contextually appropriate approaches. Organizations should also recognize that different capabilities may be critical at different transformation stages, with paradox navigation particularly important in early stages and integration mechanisms becoming more critical as transformation progresses.

Combine incremental and transformative approaches: Organizations should balance embedding sustainability within existing systems (through integration mechanisms) with more transformative approaches that question and reshape those systems. This dual approach requires both working within existing constraints and continuously expanding the boundaries of what's possible, recognizing that substantive transformation often combines incremental progress with periodic step-changes.

These practical implications offer concrete guidance for organizations seeking to bridge the gap between sustainability aspirations and substantive action, addressing a critical need identified in sustainability science (Bromley & Powell, 2012; Milne & Gray, 2013).

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Contributions

This research advances understanding of sustainability transformations in organizations by identifying the specific capabilities and integration mechanisms that enable substantive change. The findings demonstrate that successful sustainability transformations require organizations to develop paradox navigation capabilities while implementing comprehensive integration practices that embed sustainability throughout organizational systems. Power dynamics significantly influence these processes, with transformation more likely to succeed when power is broadly distributed and sustainability advocates have access to decision-making processes.

The research makes three primary contributions to sustainability science. First, it empirically demonstrates the importance of paradox navigation capabilities for addressing complex sustainability challenges, identifying specific practices that enable organizations to work productively with competing demands rather than forcing false choices. Second, it specifies four integration mechanisms—governance, strategic, operational, and performance integration—that collectively enable organizations to embed sustainability throughout their systems rather than compartmentalizing it. Third, it illuminates how contextual factors shape sustainability transformation approaches, challenging universal prescriptions and highlighting the importance of contextually-tailored strategies.

These contributions have important implications for advancing sustainable development, particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). By developing more effective organizational approaches to sustainability transformation, this research supports the transition to more sustainable production systems and governance arrangements essential for addressing global sustainability challenges.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This research has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, while our mixed-methods approach enhances validity through methodological triangulation, the cross-sectional nature of the survey data limits causal inference. Although our qualitative data provides temporal insights, future research using longitudinal designs could more definitively establish causal relationships between capabilities, mechanisms, and transformation outcomes.

Second, our sample may over-represent organizations already committed to sustainability, potentially limiting generalizability to organizations with minimal sustainability engagement. While we attempted to mitigate this bias through our sampling strategy, future research should specifically target organizations at earlier stages of sustainability awareness to understand capability development from inception.

Third, our research focused primarily on organizational-level dynamics, with limited attention to individual-level factors (cognitive frames, leadership styles, personal values) and broader system-level factors (industry dynamics, policy environments, cultural contexts). Future research should adopt multi-level approaches that connect individual, organizational, and system levels to develop more comprehensive models of sustainability transformation.

Fourth, our measures of transformation outcomes relied primarily on self-reported assessments, which may be subject to social desirability bias. While we triangulated these assessments with qualitative data and documentary evidence in the case studies, future research should incorporate more objective outcome measures to strengthen validity.

Future research should further investigate several promising areas identified in this study. First, research should examine how paradox navigation capabilities develop over time, identifying developmental pathways and potential interventions to accelerate capability development. Second, studies should explore how integration mechanisms interact with different organizational structures, particularly in emerging organizational forms such as platform organizations, distributed networks, and circular business models. Third, research should investigate how power dynamics evolve throughout transformation processes, particularly how sustainability advocates might reshape rather than merely navigate power structures.

Additionally, longitudinal studies examining sustainability transformations as they unfold would provide valuable insights into the temporal dimensions of these processes, including how different capabilities become more or less important at different transformation stages. Research examining more radical transformation approaches could also provide insights into alternative pathways toward regenerative rather than merely sustainable organizational models.

By addressing these limitations and pursuing these promising research directions, future studies can build on the foundation established in this research to develop more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of organizational sustainability transformation.

6.3. Concluding Remarks

This research demonstrates that bridging the gap between sustainability aspirations and substantive action requires organizations to develop specific capabilities while implementing comprehensive integration mechanisms that embed sustainability throughout organizational systems. By navigating paradoxical tensions, integrating sustainability into core processes, addressing power dynamics, and developing robust learning systems, organizations can achieve more substantive sustainability transformations.

However, the research also highlights the contextual nature of these transformation processes, challenging universal prescriptions and emphasizing the importance of tailoring approaches to specific organizational contexts. By recognizing these contextual contingencies while identifying common principles, this research provides both theoretical insights and practical guidance for advancing organizational sustainability transformation.

As organizations continue to grapple with mounting sustainability challenges, the capabilities and mechanisms identified in this research offer pathways for developing more effective responses. By moving beyond symbolic commitments to substantive transformation, organizations can contribute more meaningfully to addressing the complex sustainability challenges facing our world.

Survey Instrument: Sustainability Transformation in Organizations

Introduction and Consent

Thank you for participating in this research study on organizational sustainability transformation. This survey examines how organizations navigate the challenges of sustainability transitions, with particular focus on the interplay between institutional conditions and individual agency.

The survey will take approximately 20-25 minutes to complete. Your responses will remain confidential and will be reported only in aggregate form. Participation is voluntary, and you may exit the survey at any time.

By proceeding with this survey, you consent to participate in this research study.

- 2.

-

What is the size of your organization?

- 3.

-

In which region is your organization headquartered?

North America

Europe

Asia

Latin America

Africa

Oceania

- 4.

-

Which best describes your role in the organization?

C-Suite/Executive

Sustainability Director/Manager

Functional Manager

Sustainability Team Member

Other (please specify): _______

- 5.

-

How long have you been involved with sustainability initiatives?

Less than 1 year

1-3 years

4-7 years

8+ years

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements about the institutional environment in which your organization operates. (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree)

-

Regulatory Context

Sustainability-related regulations in our industry are stringent.

Regulatory compliance related to sustainability is strictly enforced.

Regulatory requirements for sustainability reporting are comprehensive.

Regulatory frameworks provide clear guidance for sustainability practices.

Regulations incentivize proactive sustainability action rather than just compliance.

-

Market Dynamics

Our customers actively demand sustainable products/services.

Competitors in our industry are advancing sustainability initiatives.

Sustainability performance influences our market position.

Investors/funders evaluate our organization on sustainability criteria.

Our supply chain partners expect sustainability commitments from us.

-

Cultural Context

The societies in which we operate value environmental protection.

Social expectations regarding corporate responsibility are high.

Sustainability is viewed as a legitimate business concern in our context.

There is public pressure for organizations like ours to address sustainability challenges.

Industry associations promote sustainability as a standard practice.

-

Technical Infrastructure

Technical solutions for our sustainability challenges are readily available.

Our industry has established sustainability metrics and standards.

Knowledge resources about sustainability practices are accessible.

Collaborative platforms for sustainability exist in our industry.

Technology enables sustainability innovation in our sector.

Please indicate how frequently the following activities occur within your organization. (1 = Never, 7 = Very Frequently)

-

Strategic Framing

Sustainability issues are framed in terms of business opportunities.

Sustainability initiatives are connected to core organizational values.

Sustainability challenges are positioned as innovation opportunities.

Sustainability is framed differently for different stakeholder groups.

Long-term sustainability vision is connected to short-term actions.

-

Coalition Building

Sustainability champions form alliances across departments.

Supporters of sustainability initiatives are strategically identified and engaged.

Partnerships with external stakeholders advance internal sustainability goals.

Cross-functional teams collaborate on sustainability challenges.

Senior leadership support for sustainability initiatives is actively cultivated.

-

Resource Mobilization

Sustainability champions secure dedicated resources for initiatives.

External funding sources for sustainability projects are identified and accessed.

Existing organizational resources are repurposed for sustainability work.

Human resources with sustainability expertise are strategically deployed.

Success stories are leveraged to gain additional resource commitments.

-

Political Strategies

Sustainability champions navigate power dynamics to advance initiatives.

Resistance to sustainability initiatives is anticipated and addressed.

Informal influence networks are activated to support sustainability efforts.

Windows of opportunity for advancing sustainability are strategically exploited.

Potential opponents to sustainability initiatives are converted or neutralized.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements about how your organization handles tensions in sustainability work. (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree)

-

Practices

Our organization acknowledges tensions between competing sustainability objectives.

We recognize that sustainability involves inherent contradictions.

Competing stakeholder demands regarding sustainability are openly discussed.

Trade-offs between short-term and long-term considerations are explicitly addressed.

We accept that not all sustainability tensions can be permanently resolved.

-

Both/And Thinking