Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. NOx Scrubbing Experiments

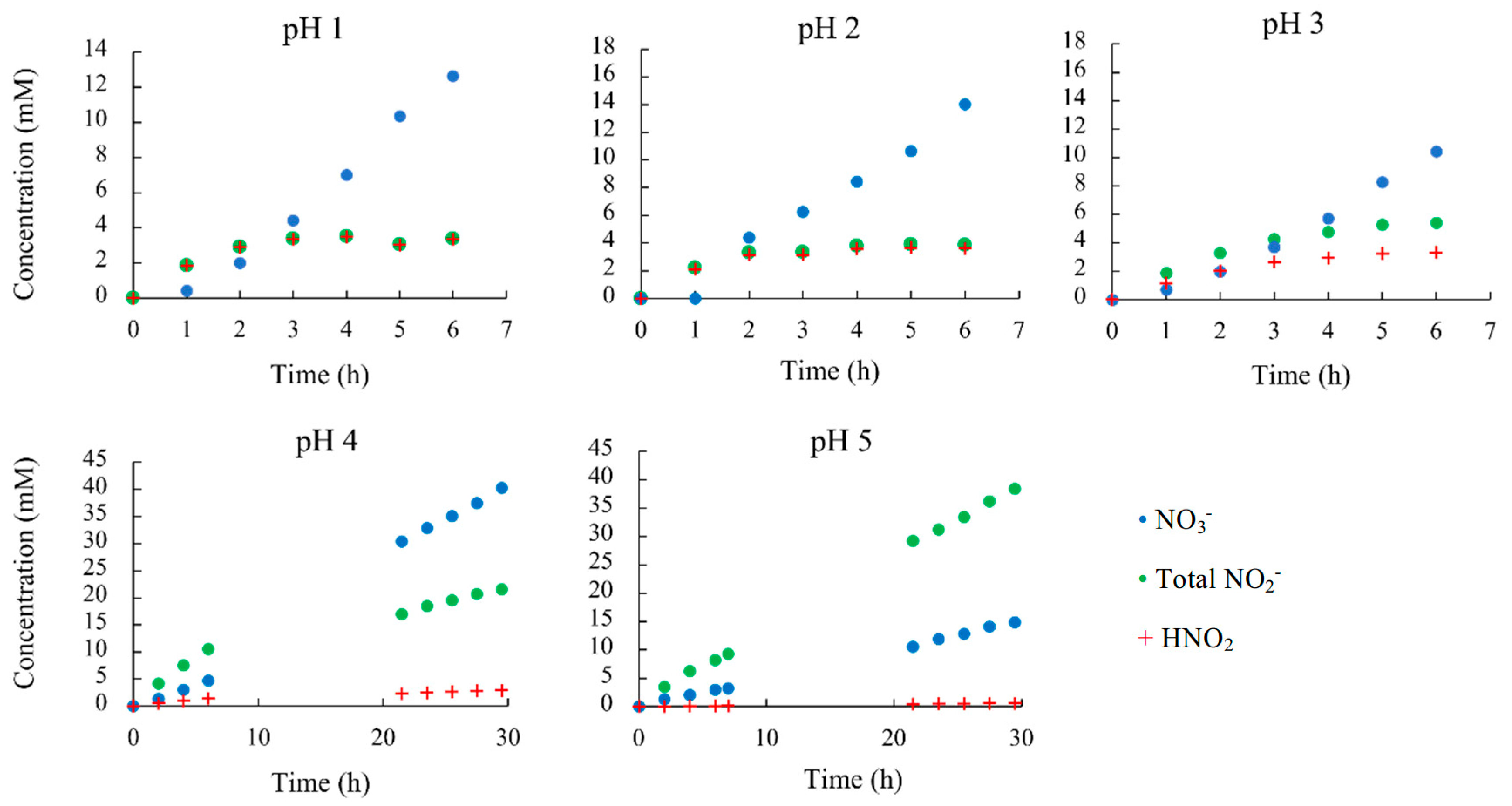

2.2. Scrubber Liquid Analysis

2.3. Gas Phase Analysis

3. Discussion

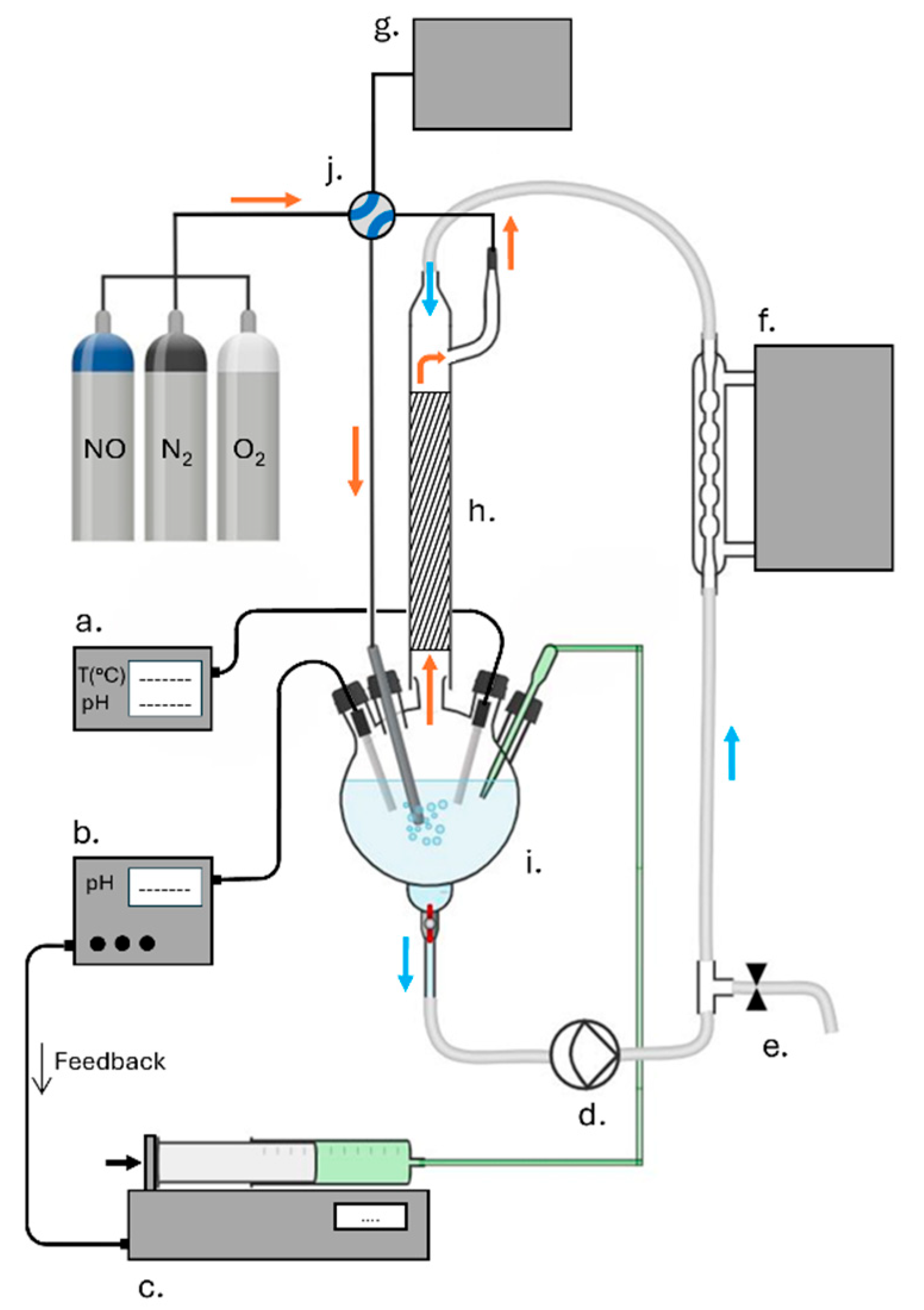

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OR | Oxidation Ratio |

| EBV | Empty Bed Volume |

| RE | Removal Efficiency |

References

- Hannah Ritchie How Many People Does Synthetic Fertilizer Feed? Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/how-many-people-does-synthetic-fertilizer-feed (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- DG Agriculture and Rural Development, U.A. and outlook Fertilisers in the EU Prices, Trade and Use; 2019; Vol. 15;

- Kyriakou, V.; Garagounis, I.; Vourros, A.; Vasileiou, E.; Stoukides, M. An Electrochemical Haber-Bosch Process. Joule 2020, 4, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, F.; Clarke, A.; Davies, P.; Surkovic, E. Ammonia: Zero-Carbon Fertiliser, Fuel and Energy Store; Royal Society: London, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, P.; Ramirez, A.; Pezzella, G.; Winter, B.; Sarathy, S.M.; Gascon, J.; Bardow, A. Blue and Green Ammonia Production: A Techno-Economic and Life Cycle Assessment Perspective. iScience 2023, 26, 107389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JOSHI, J.B.; MAHAJANI, V.V.; JUVEKAR, V.A. INVITED REVIEW ABSORPTION OF NOX GASES. Chem Eng Commun 1985, 33, 1–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, C.A.; Andreassen, K.A.; Cavka, J.H.; Waller, D.; Lorentsen, O.-A.; Øien, H.; Zander, H.-J.; Poulston, S.; García, S.; Modeshia, D. Process Intensification in Nitric Acid Plants by Catalytic Oxidation of Nitric Oxide. Ind Eng Chem Res 2018, 57, 10180–10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A. ul R.; Enger, B.C.; Auvray, X.; Lødeng, R.; Menon, M.; Waller, D.; Rønning, M. Catalytic Oxidation of NO to NO2 for Nitric Acid Production over a Pt/Al2O3 Catalyst. Appl Catal A Gen 2018, 564, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemann, M.; Scheibler, E.; Wiegand, K.W. Nitric Acid, Nitrous Acid, and Nitrogen Oxides. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley, 2000; Vol. 24, pp. 177–223.

- Rouwenhorst, K.H.R.; Jardali, F.; Bogaerts, A.; Lefferts, L. From the Birkeland–Eyde Process towards Energy-Efficient Plasma-Based NO X Synthesis: A Techno-Economic Analysis. Energy Environ Sci 2021, 14, 2520–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardali, F.; Van Alphen, S.; Creel, J.; Ahmadi Eshtehardi, H.; Axelsson, M.; Ingels, R.; Snyders, R.; Bogaerts, A. NOx Production in a Rotating Gliding Arc Plasma: Potential Avenue for Sustainable Nitrogen Fixation. Green Chemistry 2021, 23, 1748–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Vanderschuren, J. Nitrogen Oxides Scrubbing with Alkaline Solutions. Chem Eng Technol 2000, 23, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zwolińska, E.; Chmielewski, A.G. Abatement Technologies for High Concentrations of NO x and SO 2 Removal from Exhaust Gases: A Review. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 2016, 46, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Peng, D.; Chiang, P.-C.; Chu, C. Performance Evaluation of NOx Absorption by Different Denitration Absorbents in Wet Flue Gas Denitration. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2023, 145, 104840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, B. Purification Technologies for NOx Removal from Flue Gas: A Review. Separations 2022, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalska, K.; Miller, J.S.; Ledakowicz, S. Intensification of NOx Absorption Process by Means of Ozone Injection into Exhaust Gas Stream. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification 2012, 61, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Vanderschuren, J. The Absorption-Oxidation of NOx with Hydrogen Peroxide for the Treatment of Tail Gases. Chem Eng Sci 1996, 51, 2649–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, E.B.; Overcamp, T.J. Hydrogen Peroxide Scrubber for the Control of Nitrogen Oxides. Environ Eng Sci 2002, 19, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, M.; Shen, B.; Adwek, G.; Xiong, L.; Liu, L.; Yuan, P.; Gao, H.; Liang, C.; Guo, Q. Review on the NO Removal from Flue Gas by Oxidation Methods. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2021, 101, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talviste, R.; Jõgi, I.; Raud, S.; Noori, H.; Raud, J. Nitrite and Nitrate Production by NO and NO2 Dissolution in Water Utilizing Plasma Jet Resembling Gas Flow Pattern. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing 2022, 42, 1101–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, H.; Raud, J.; Talviste, R.; Jõgi, I. Water Dissolution of Nitrogen Oxides Produced by Ozone Oxidation of Nitric Oxide. Ozone Sci Eng 2021, 43, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, J.A.; Joshi, J.B. Unified Model for NOX Absorption in Aqueous Alkaline and Dilute Acidic Solutions. AIChE Journal 2003, 49, 2728–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghriss, O.; Ben Amor, H.; Jeday, M.-R.; Thomas, D. Nitrogen Oxides Absorption into Aqueous Nitric Acid Solutions Containing Hydrogen Peroxide Tested Using a Cables-Bundle Contactor. Atmos Pollut Res 2019, 10, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, Y.; LIU, Y.; ZHANG, L.; SU, Q.; JIN, G. Absorption of NOx into Nitric Acid Solution in Rotating Packed Bed. Chin J Chem Eng 2010, 18, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüpen, B.; Kenig, E.Y. Rigorous Modelling OfNOx Absorption in Tray and Packed Columns. Chem Eng Sci 2005, 60, 6462–6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.E.; White, W.H. Kinetics of Reactive Dissolution of Nitrogen Oxides into Aqueous Solution. Advances in Environmental Science and Technology 1983, 12, 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Suchak, N.J.; Jethani, K.R.; Joshi, J.B. Modeling and Simulation of NO X Absorption in Pilot-scale Packed Columns. AIChE Journal 1991, 37, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingale, N.D.; Chatterjee, I.B.; Joshi, J.B. Role of Nitrous Acid Decomposition in Absorber and Bleacher in Nitric Acid Plant. Chemical Engineering Journal 2009, 155, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayson, M.S.; Mackie, J.C.; Kennedy, E.M.; Dlugogorski, B.Z. Accurate Rate Constants for Decomposition of Aqueous Nitrous Acid. Inorg Chem 2012, 51, 2178–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.; Schmid, H. Kinetik Der Salpetrigen Säure. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 1928, 132U, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Vanderschuren, J. Modeling of NO x Absorption into Nitric Acid Solutions Containing Hydrogen Peroxide. Ind Eng Chem Res 1997, 36, 3315–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, R. Compilation of Henry’s Law Constants (Version 5.0.0) for Water as Solvent. Atmos Chem Phys 2023, 23, 10901–12440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOKI, M.; TANAKA, H.; KOMIYAMA, H.; INOUE, H. Simultaneous Absorption of NO and NO2 into Alkaline Solutions. JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERING OF JAPAN 1982, 15, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Rout, P.R.; Bae, J. The Applicability of Anaerobically Treated Domestic Wastewater as a Nutrient Medium in Hydroponic Lettuce Cultivation: Nitrogen Toxicity and Health Risk Assessment. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 780, 146482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.R.; Ran, W.; Cao, Z.H. Mechanisms of Nitrite Accumulation Occurring in Soil Nitrification. Chemosphere 2003, 50, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukahara, H.; Ishida, T.; Mayumi, M. Gas-Phase Oxidation of Nitric Oxide: Chemical Kinetics and Rate Constant. Nitric Oxide 1999, 3, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsonev, I.; O’Modhrain, C.; Bogaerts, A.; Gorbanev, Y. Nitrogen Fixation by an Arc Plasma at Elevated Pressure to Increase the Energy Efficiency and Production Rate of NO x. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2023, 11, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, N.; Adolph; Speight, J.G. Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry, 16th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Wyoming, 2005; ISBN 0071432205. [Google Scholar]

| pH | Time (h) | Total NO2- (mM) | NO2- (mM) | HNO2 (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 3.37 | 0.0211 | 3.35 |

| 2 | 6 | 3.86 | 0.229 | 3.63 |

| 3 | 6 | 5.41 | 2.09 | 3.32 |

| 4 | 30 | 21.6 | 18.6 | 2.95 |

| 5 | 30 | 38.4 | 37.8 | 0.599 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).