Submitted:

28 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

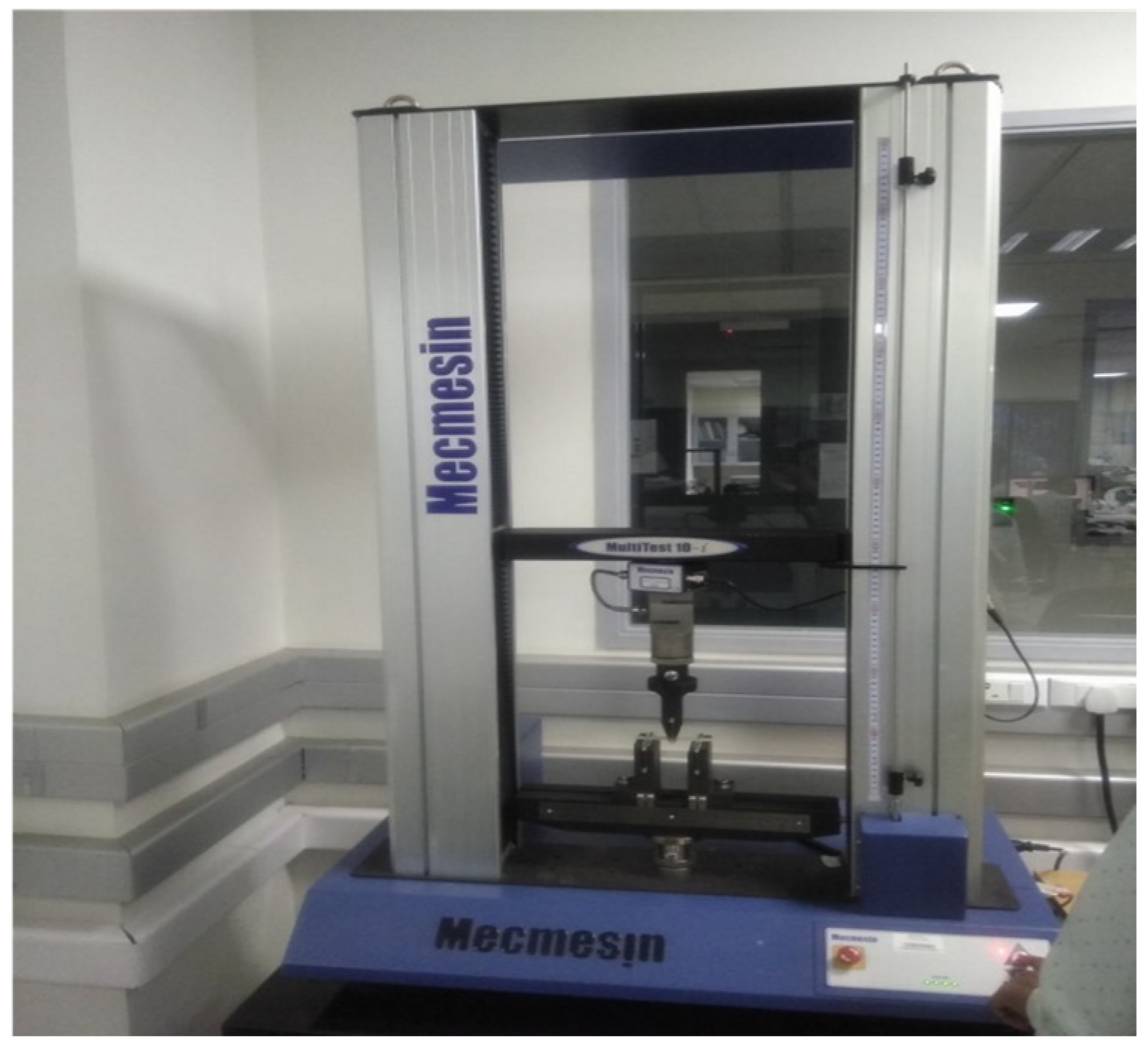

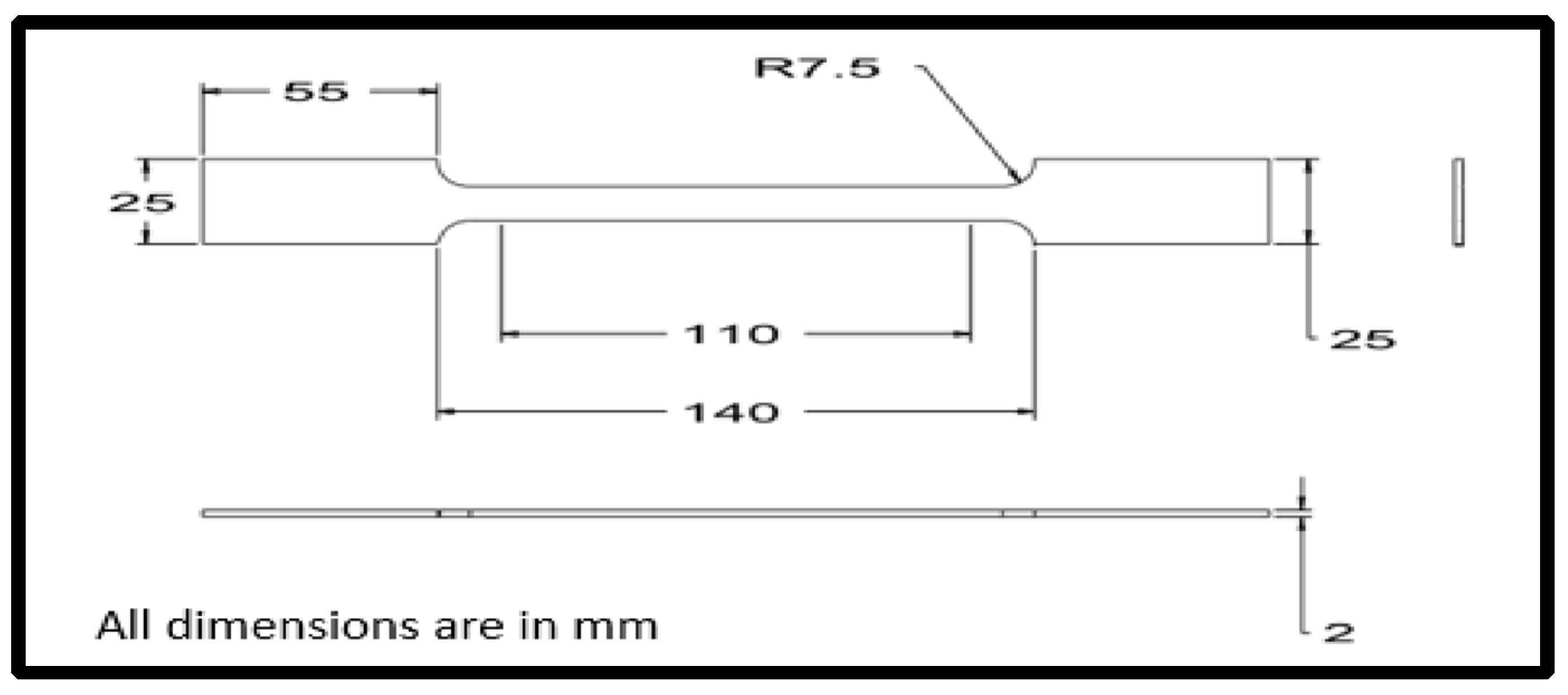

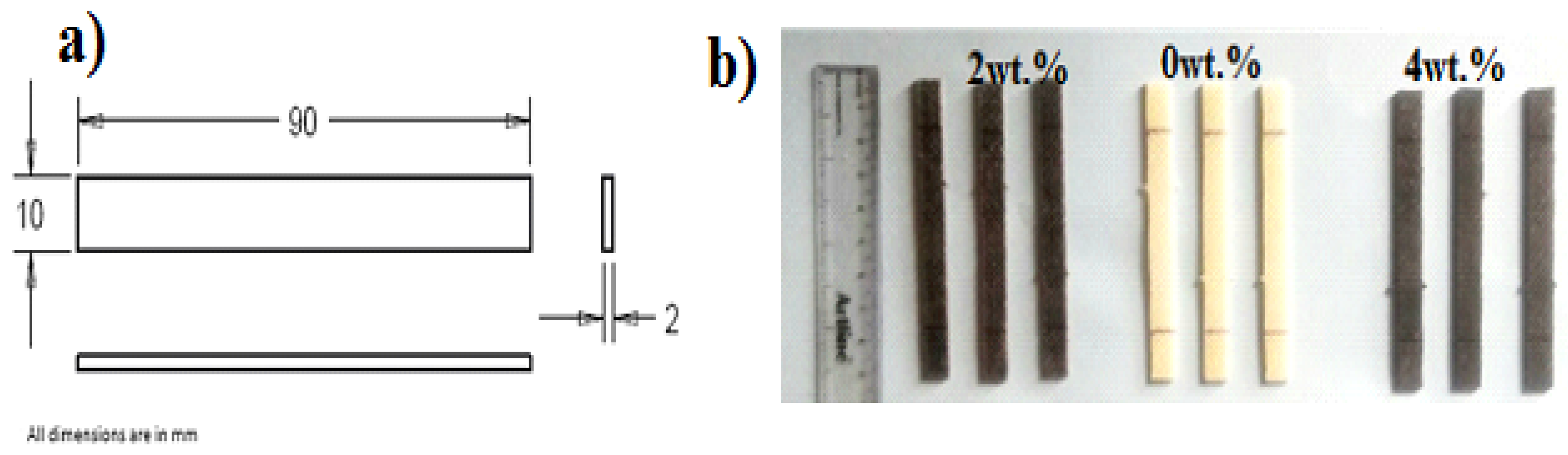

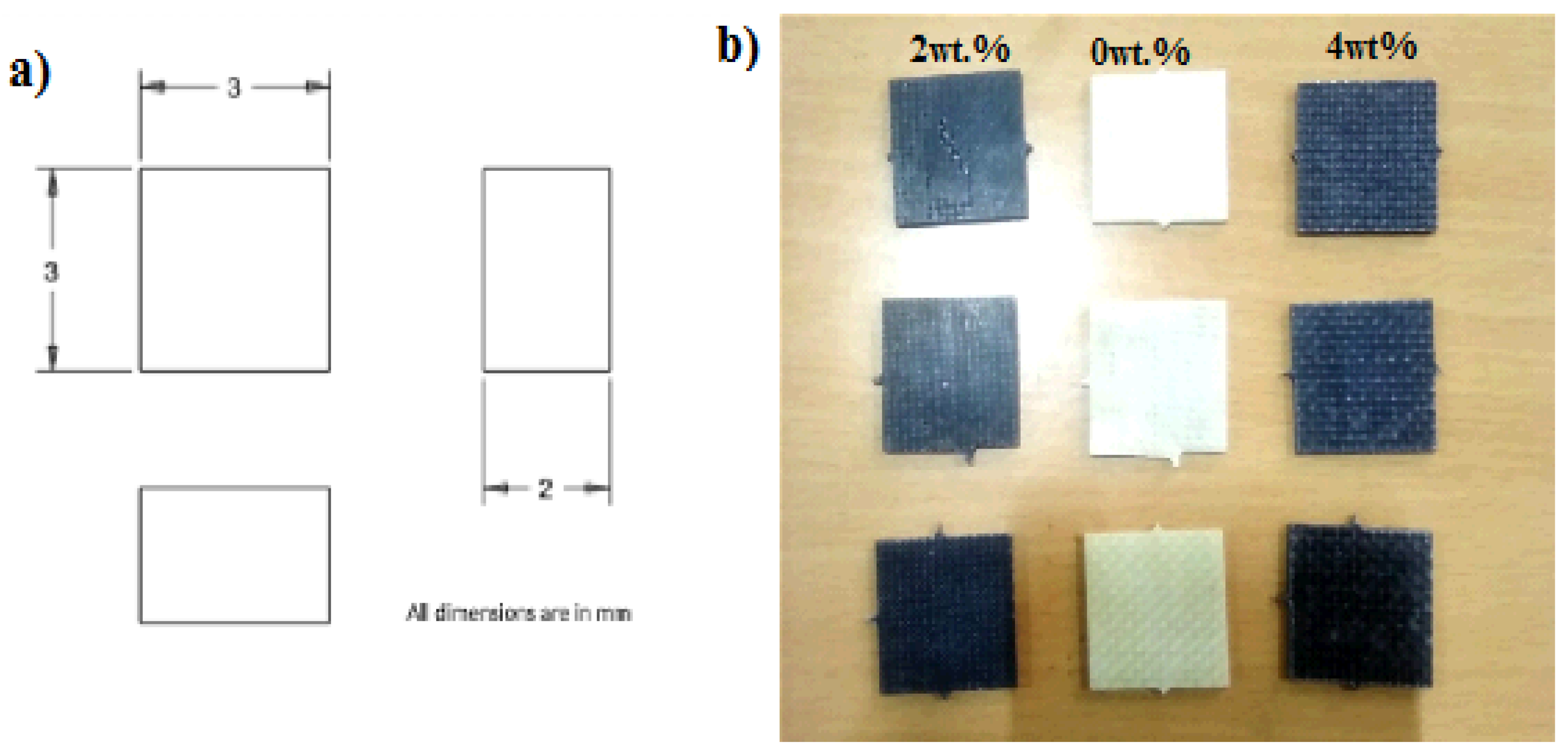

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Detail Work

3. Results and Discussion

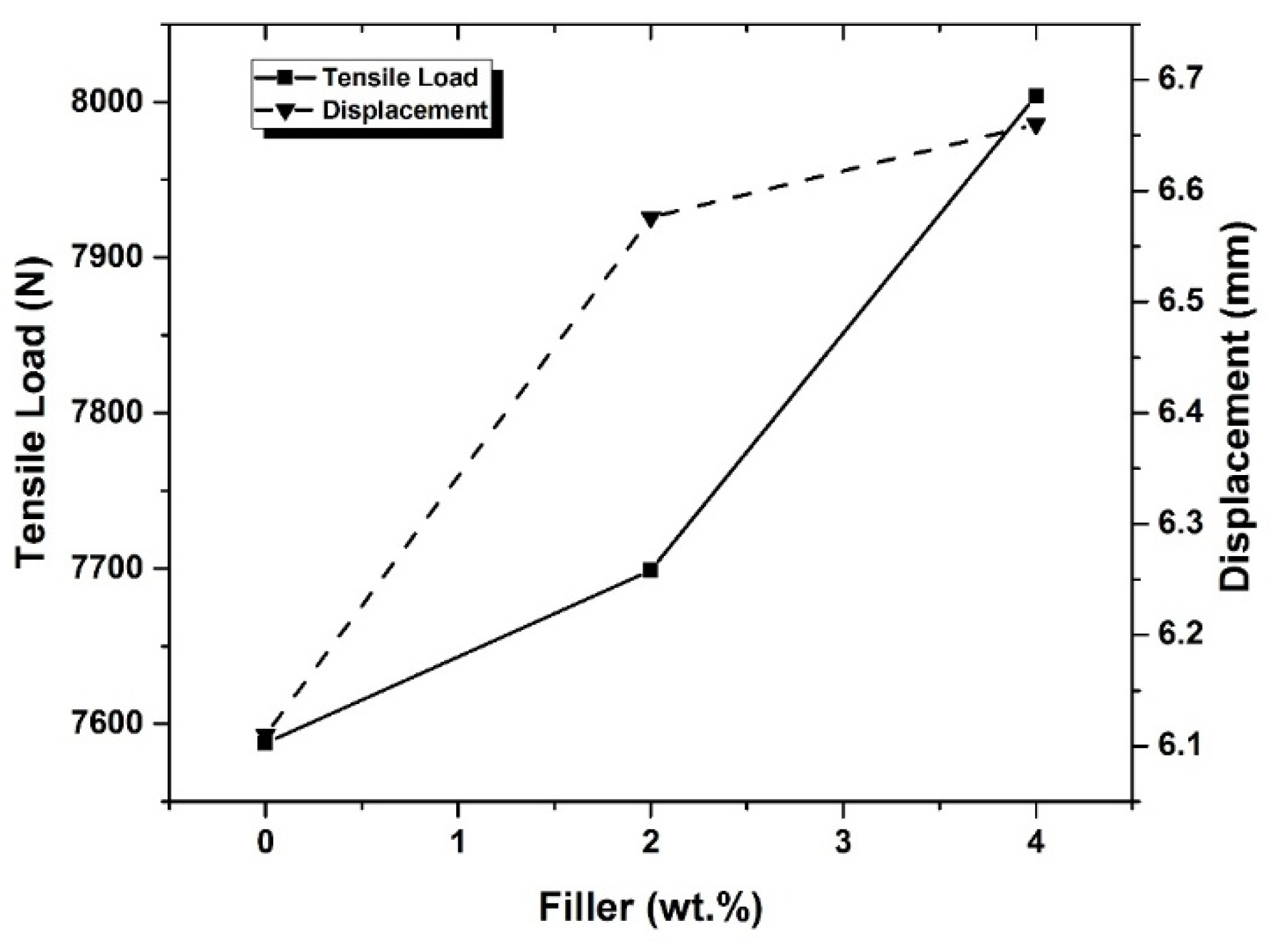

3.1. Results Discussion on Tensile Testing

- It was observed that the load-carrying capacity was increased with an increase in Graphene content in the composites. Initially, the tensile load obtained for the plain composite without graphene powder was 7587.66 N, and it increased to 8004 N for the composite with 4 wt.% % of Graphene content.

- The tensile strength of composites depends on interfacial bonding strength between matrix and reinforcement to a larger extent, and also on the inherent properties of composite ingredients [37]. It was observed that there is a 1.46% tensile load and 7.63% of elongation improvement for composites with 2% filler material, while the composite with 4% filler material showed 5.50% tensile load and 9% elongation improvement.

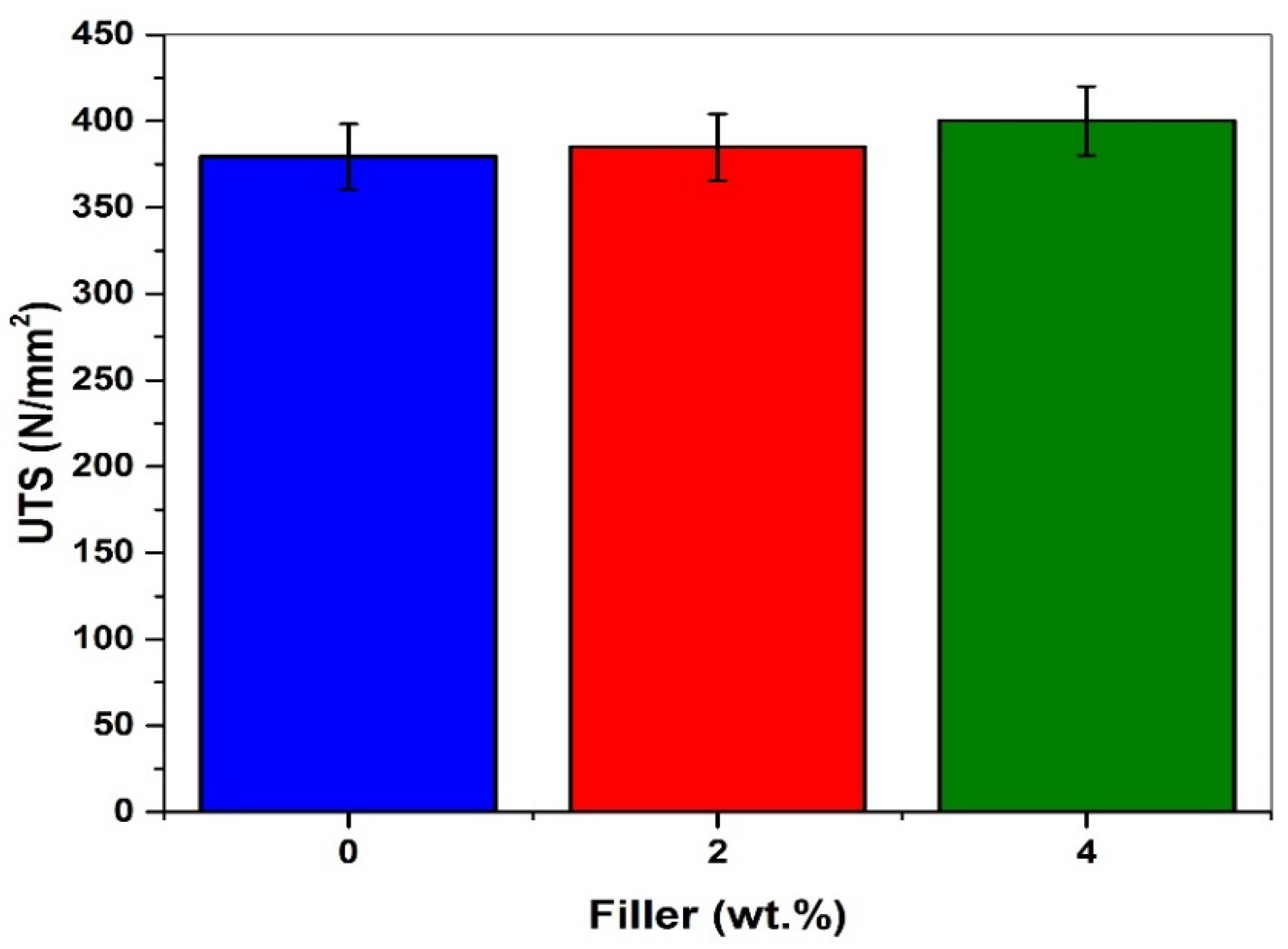

- The role of glass fibers in the composite limits the failure [38] and the increase in the filler material content exhibits the upward trend in tensile properties [31]. Figure 8 shows the marginal increase in the ultimate tensile strength as a result of increased interfacial bonding between the glass fiber and epoxy matrix due to the addition of Graphene as filler material.

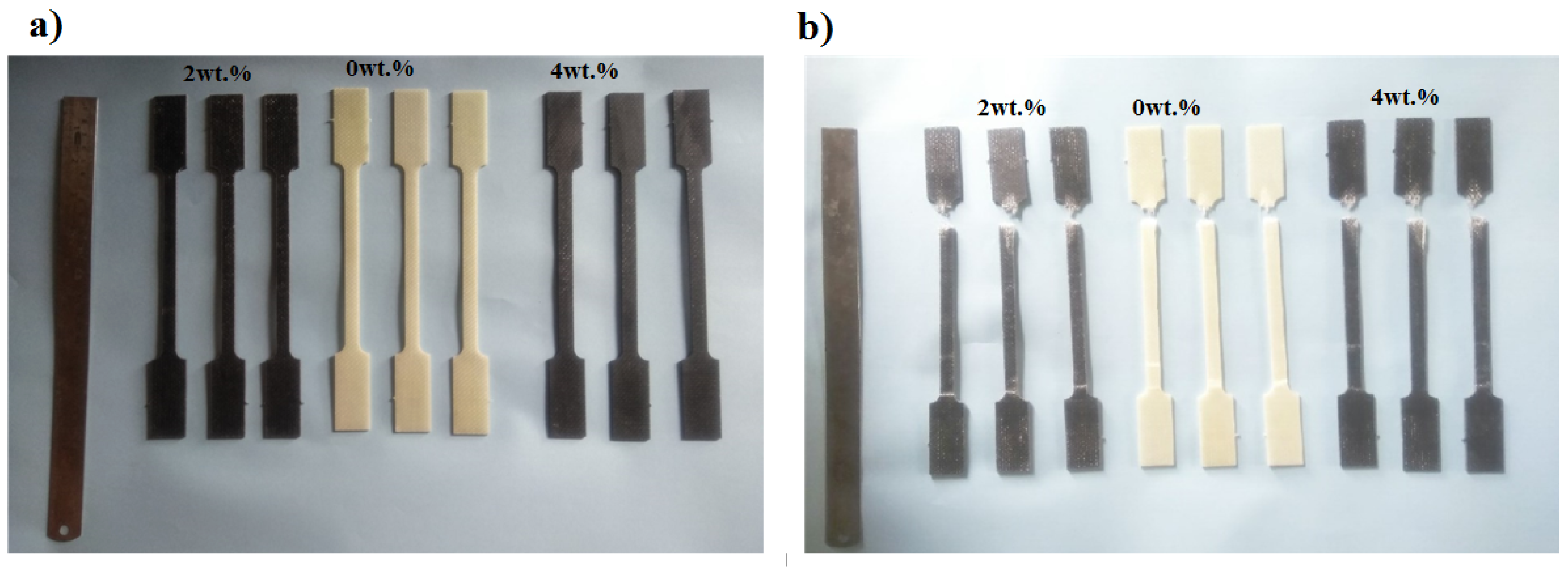

3.2. Results Discussion on Flexural Test

- ❖

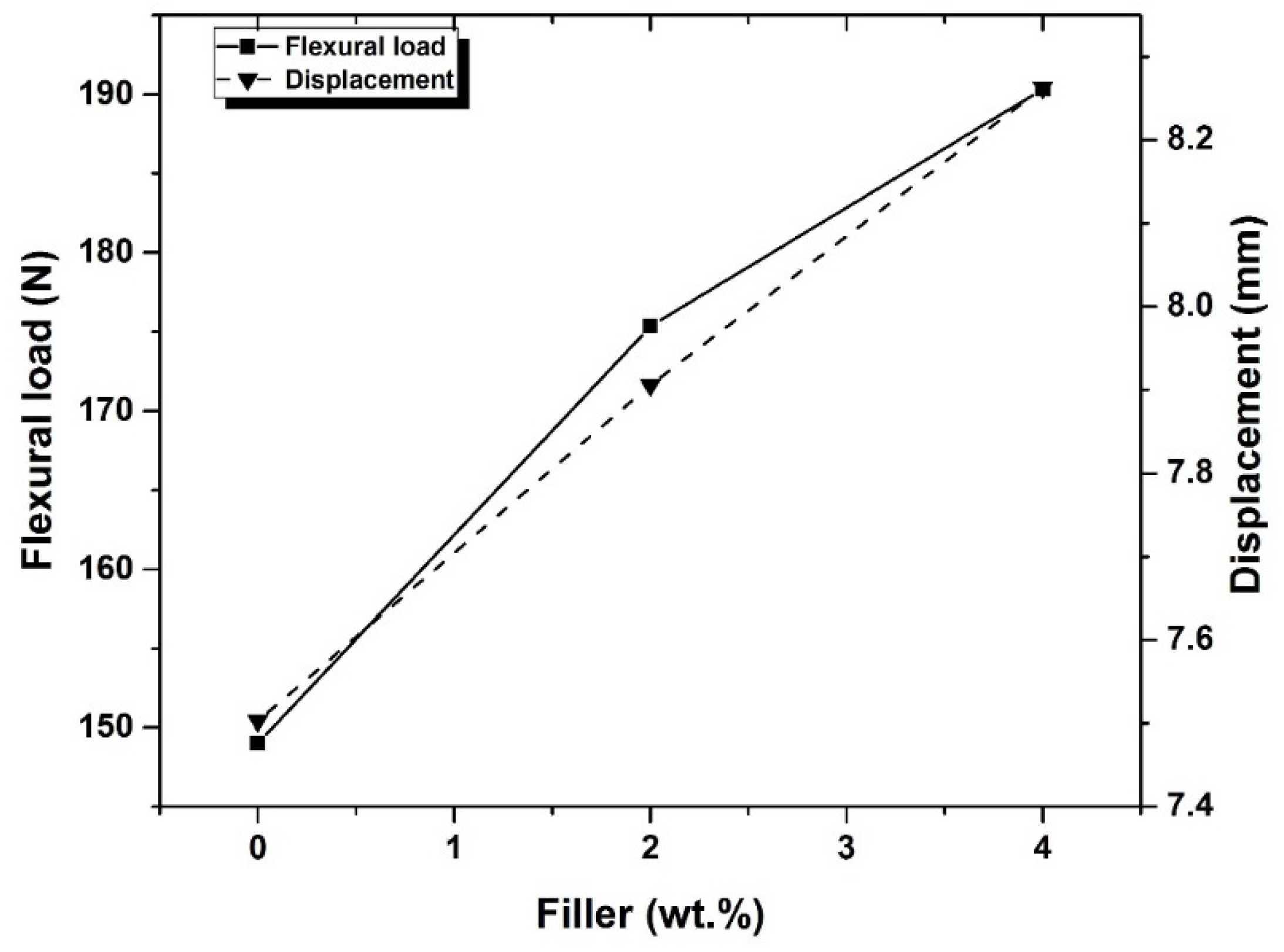

- The comparative plot of the flexural load versus displacement for each of the combinations of glass fiber reinforced composites is shown in Figure 10. It is observed from the graph that the flexural load-carrying capacity was increased with an increase in Graphene content in the composites.

- ❖

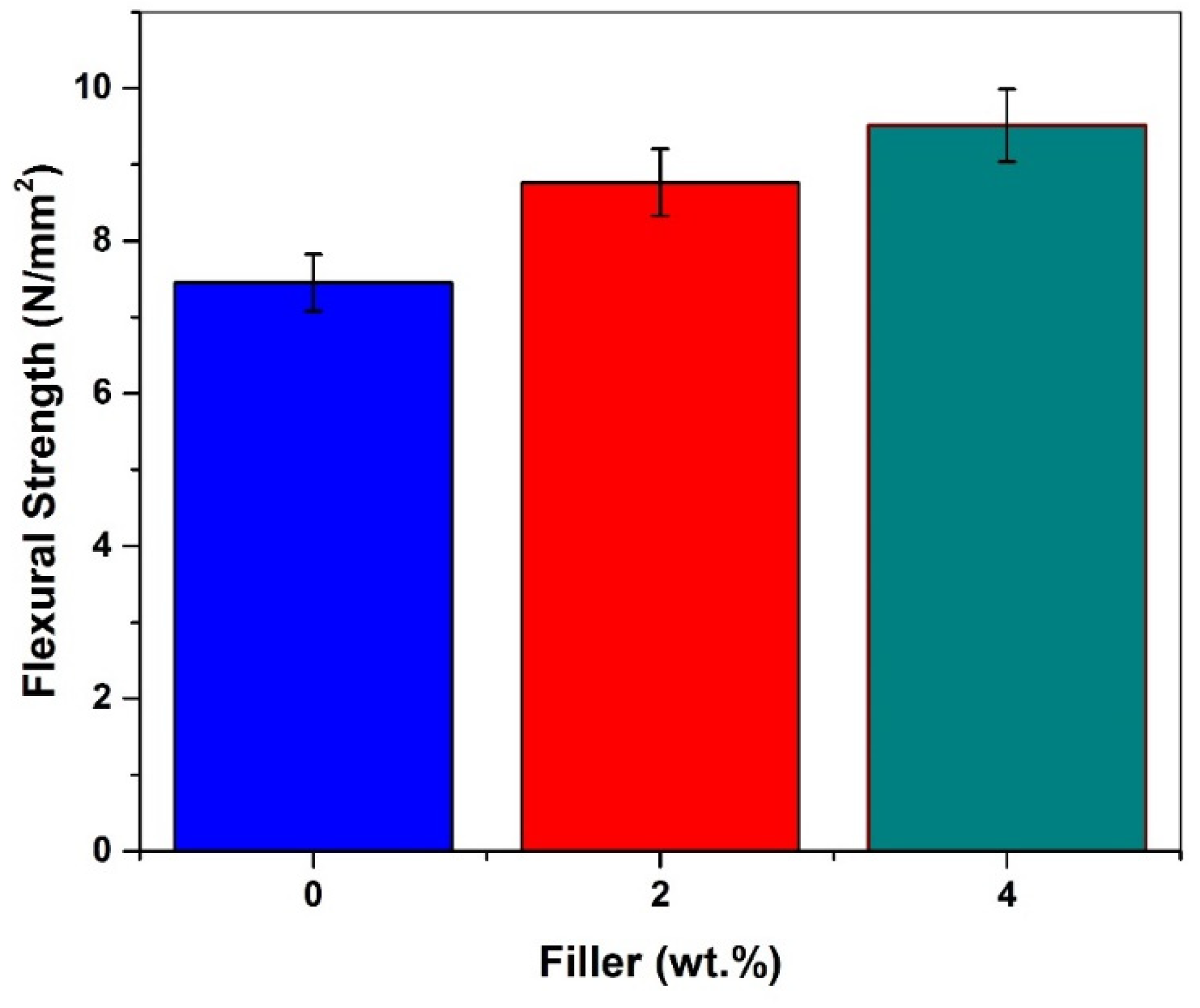

- The improvement of flexural load from 149N for plain GFRP to 190.33N for GFRP with 4% filler material is a result of good adhesion with the matrix formed with the addition of Graphene powder in the material [13]. It is seen that there is 17.68% of flexural load and 5.38% of elongation improvement for composites with 2% filler material, and the composite with 4% filler material showed 27.74% flexural load and 10.13% of elongation improvements obtained from the flexural three-point bending test.

- ❖

- Figure 10 indicates that the flexural strength of filler-added GFRP was more compared with the Normal GFRP. This is due to the uniform dispersion of filler material in the matrix enhances the flexural properties of the materials by increasing interfacial bonding strength [15].

| (Observation) | Filler Content (wt.% Graphene) | Plain Composite (0%) | 2% Filler | 4% Filler | Improvement (2% vs. 0%) | Improvement (4% vs. 0%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Load1 (N) | - | 7587.66 N | - | 8004 N | +1.46% | +5.50% |

| Tensile Elongation (%) | - | (0% graphene filler). | +7.63% | +9% | - | - |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength | - | - | Borderline increase | Borderline increase | Improved interfacial bonding | Improved interfacial bonding |

| Flexural Load 2 (N) |

- | 149 N | - | 190.33 N | +17.68% | +27.74% |

| Flexural Elongation (%) | - | Baseline | +5.38% | +10.13% | - | - |

| Flexural Strength | - | Lower | Higher | Highest | Enhanced dispersion |

Enhanced dispersion |

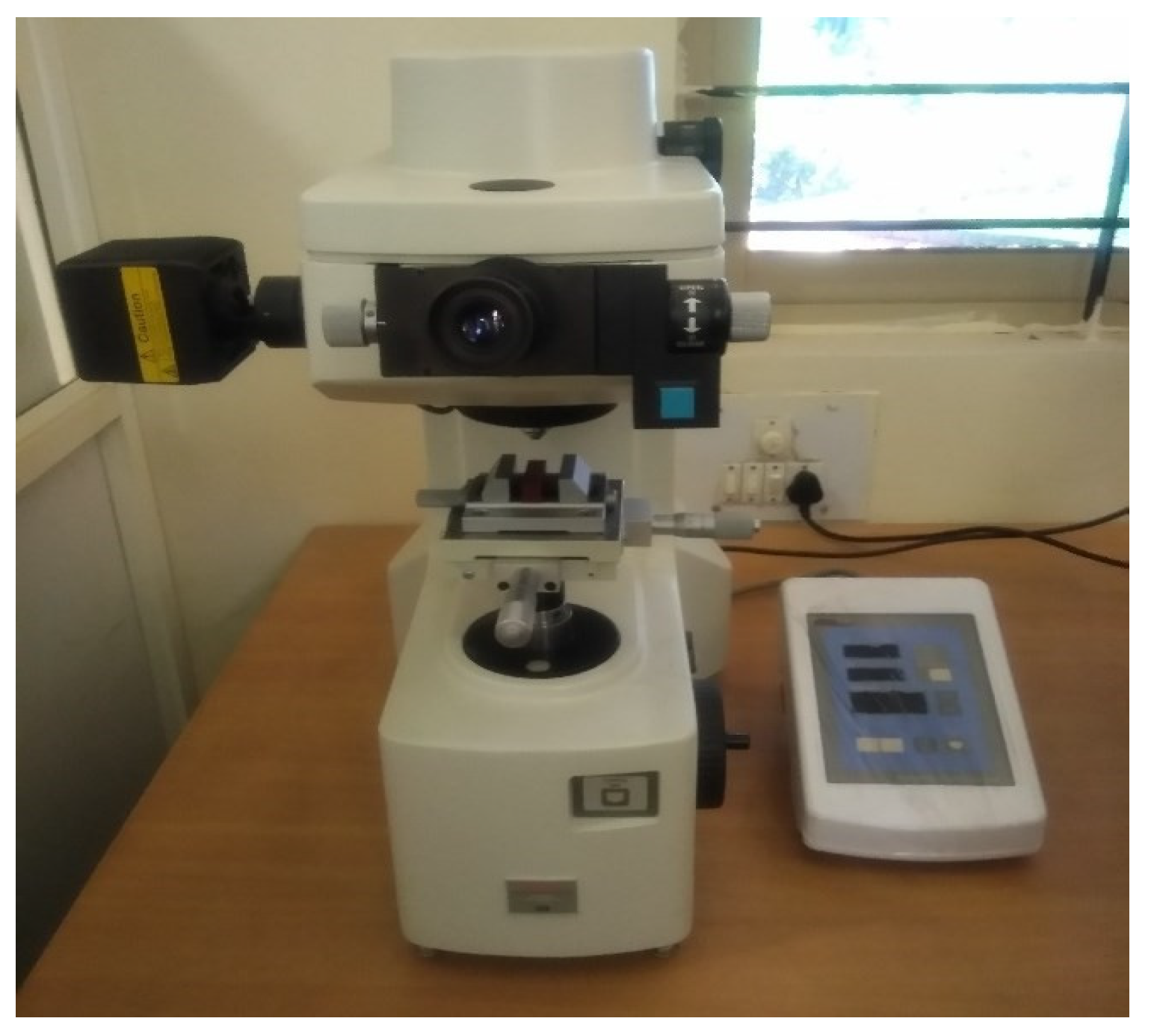

3.3. Results for Micro Hardness Test

- a)

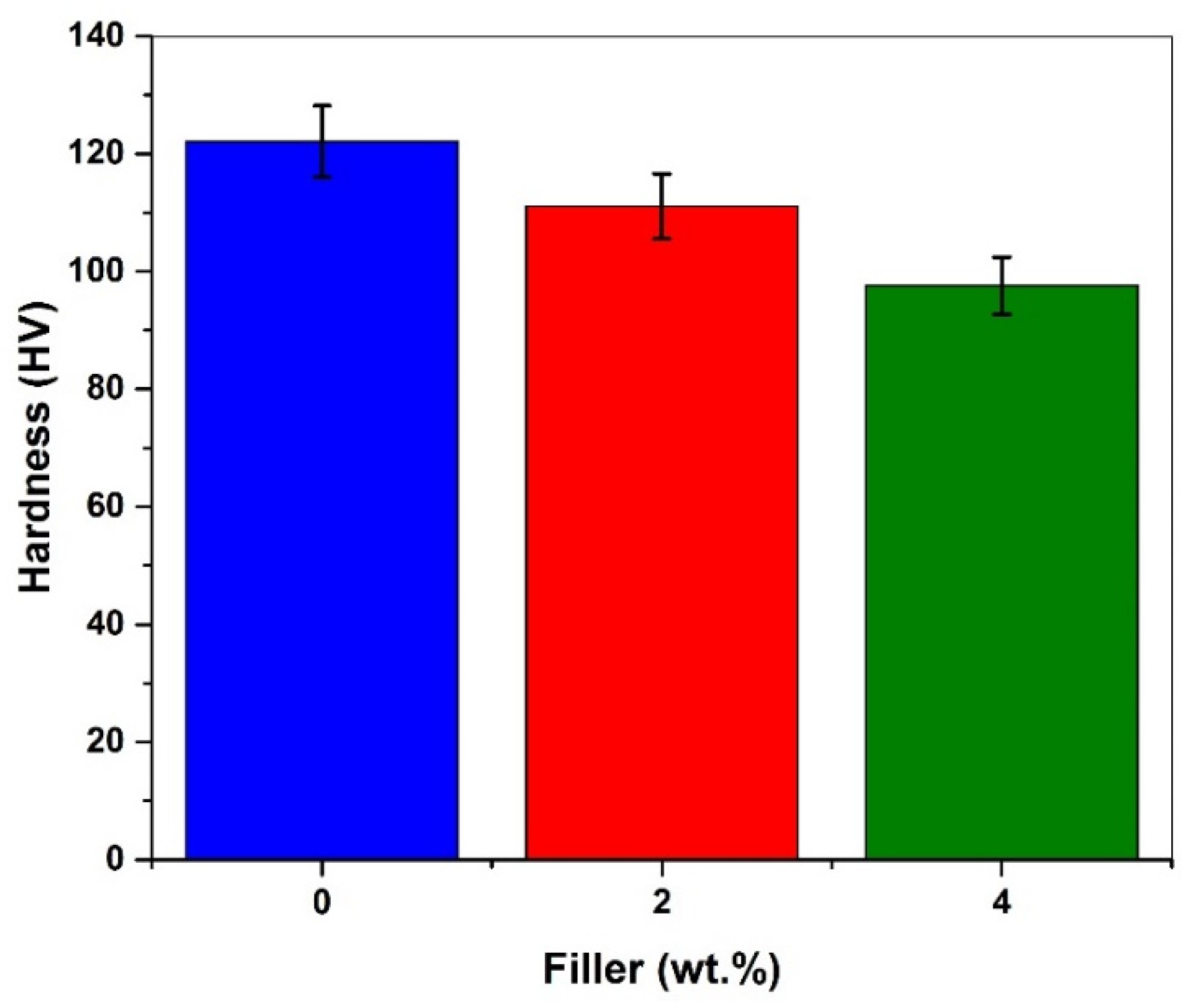

- GFRP composites with 2% filler material exhibit an 8.99% decrease in hardness values, whereas GFRP composites with 4% filler material show a 20% decrease in the values of hardness. It is revealed from the experimental results that the addition of Graphene powder resulted in a decrease in the brittleness of the composites.

3.4. SEM Characterization

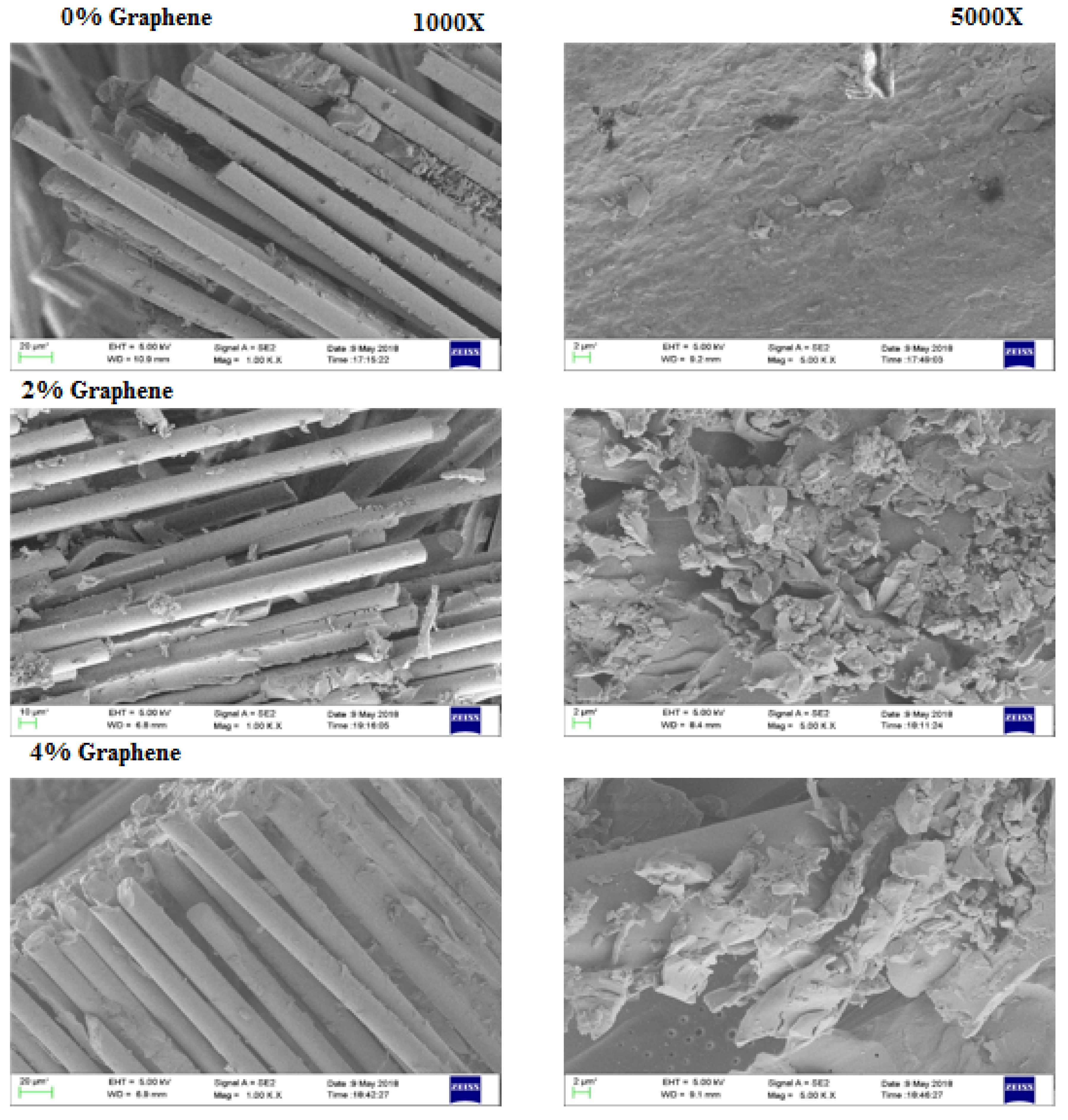

- GFRP composites show the fractured glass fibers on the smooth fractured surface, implying that the adhesion between the glass fiber layers and the resin is weak. The adhesion between the glass fiber and the matrix was observed to be stronger with the addition of Graphene powder, as the fibers are bonded together more firmly. The composite with 4% Graphene powder exhibits fiber pullouts in a single plane as a result of uniform pullout and more intact fiber adhesion.

- The filler material, Graphene, dispersed uniformly in the matrix, revealed at higher magnification, 5000X. This gives hints of minimum cluster and agglomeration of Graphene powder in the matrix, resulting in strong interfacial bonding between the matrix and reinforcement. GFRP with 4% filler material revealed minimum void formation in the matrix. The fractured surface of the tensile specimens of the composites without the filler materials revealed predominant delamination caused due to the interaction between the glass fiber and the matrix material.

- The delamination stress at the fractured surface accelerates fracture at the matrix and reinforcement interface, resulting in complete fracture at the surface. From the SEM micrograph, fiber pulls out were predominant in the composite without the filler material as a result of higher displacement, whereas the filler added composites show some hindrance to fiber pullouts, resulting in higher load bearing capacity of composites. Hence, the filler material reduces the interfacial interaction between the matrix and reinforcement.

| (Observation) | (0% Filler - Plain GFRP) | (With Filler - 2% & 4% Graphene) |

|---|---|---|

| Microhardness4 | Higher (Baseline) | 2% filler: 8.99% decrease 4% filler: 20% decrease |

| Brittleness | Harder | Reduced brittleness with filler addition |

| Fiber-Matrix Adhesion (SEM) | Weak adhesion, fiber pullouts, delamination | Stronger adhesion, uniform fiber bonding, fewer voids |

| Fiber Pullout Behavior | Main pullouts, smooth fracture surface | Hindered pullouts, intact fibers (4% filler) |

| Filler Dispersion (SEM at 5000X) | N/A (No filler) | Uniform dispersion, minimal agglomeration |

| Void Development | Noticeable voids & delamination | Summary voids (especially at 4% filler) |

4. Conclusions

- From the experimental values, it can be observed that the tensile strength and flexural strength of the composite were improved with the addition of Graphene powder.

- The tensile properties of the composites were influenced by the addition of filler material. The maximum tensile strength can be observed in the composite with 4% filler material, with a tensile load value of 8004 N, with an improvement of 5.48%.

- Flexural property mainly depends on the combination of compression and shear strength of the composites. The flexural property of the composites with filler material 4 wt.% exhibits improvement of 27.74%, witnessing a maximum flexural load value of 190.33 N compared with the composite without the filler material.

- The hardness occurs because of the difference in hardness between the epoxy matrix and glass fibers. The hardness value reached a maximum of 122.066 HV for the composite without filler material, with an improvement of 20% decrease in hardness for 4 wt.% of graphene powder as filler material, with a value of 97.6 HV.

- From SEM analysis, the GFRP composites exhibit the presence of minimum voids, fibers, and matrix bonding, and fiber pullout in the right direction. The addition of filler material resulted in better interfacial bonding, minimum agglomeration, and voids.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | Meaning |

|---|---|

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| ASTM | American Society of Testing and Materials |

| GERP | Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer or Plastic |

| FRP | Fiber Reinforced Polymer |

References

- William D. Callister, J. Materials Science and Engineering - An Introduction. 2007.

- Roy, S. Comparative analysis of thermo-physical and mechanical properties of PALF/CF/epoxy resin with and without nano TiO2 filler. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2023;148:106201. [CrossRef]

- Sharma H, Kumar A, Rana S, Sahoo NG, Jamil M, Kumar R, et al. Critical review on advancements on fiber-reinforced composites: Role of fiber/matrix modification on the performance of the fibrous composites. J Mater Res Technol 2023;26:2975 3002. [CrossRef]

- Ali Z, Yaqoob S, Yu J, D’Amore A. Critical review on the characterization, preparation, and enhanced mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of carbon nanotubes and their hybrid filler polymer composites for various applications. Compos Part C Open Access 2024;13:100434. [CrossRef]

- Rashid A Bin, Haque M, Islam SMM, Uddin Labib KMR. Nanotechnology-enhanced fiber-reinforced polymer composites: Recent advancements on processing techniques and applications. Heliyon 2024;10:e24692. [CrossRef]

- Balaji Ayyanar C, Kumar R, Helaili S, B G, RinusubaV, Nalini H E, et al. Experimental and numerical analysis of natural fillers loaded and E-glass reinforced epoxy sandwich composites. J Mater Res Technol 2024;32:1235 44. [CrossRef]

- Demir TN, Yuksel Yilmaz AN, Celik Bedeloglu A. Investigation of mechanical properties of aluminum–glass fiber-reinforced polyester composite joints bonded with structural epoxy adhesives reinforced with silicon dioxide and graphene oxide particles. Int J Adhes Adhes 2023;126:103481. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed KK, Muheddin DQ, Mohammed PA, Ezat GS, Murad AR, Ahmed BY, et al. A brief review on optical properties of polymer Composites: Insights into Light-Matter interaction from classical to quantum transport point of view. Results Phys 2024;56:107239. [CrossRef]

- Yi Hsu C, Mahmoud ZH, Abdullaev S, Abdulrazzaq Mohammed B, Altimari US, Laftah Shaghnab M, et al. Nanocomposites based on Resole/graphene/carbon fibers: A review study. Case Stud Chem Environ Eng 2023;8:100535. [CrossRef]

- Gull N, Khan SM, Munawar MA, Shafiq M, Anjum F, Butt MTZ, et al. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide (ZnO) filled glass fiber reinforced polyester composites. Mater Des 2015;67:313–7. [CrossRef]

- Shahnaz T, Hayder G, Shah MA, Ramli MZ, Ismail N, Hua CK, et al. Graphene-based nanoarchitecture as a potent cushioning/filler in polymer composites and their applications. J Mater Res Technol 2024;28:2671–98. [CrossRef]

- Harle, SM. Durability and long-term performance of fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) composites: A review. Structures 2024;60:105881. [CrossRef]

- Mishra BP, Mishra D, Panda P, Maharana A. An experimental investigation of the effects of reinforcement of graphene fillers on mechanical properties of bi-directional glass/epoxy composite. Mater Today Proc 2020;33:5429–41. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal Khan Z, Habib U, Binti Mohamad Z, Razak Bin Rahmat A, Amira Sahirah Binti Abdullah N. Mechanical and thermal properties of sepiolite strengthened thermoplastic polymer nanocomposites: A comprehensive review. Alexandria Eng J 2022;61:975–90. [CrossRef]

- Megahed M, Abd El-baky MA, Alsaeedy AM, Alshorbagy AE. An experimental investigation on the effect of incorporation of different nanofillers on the mechanical characterization of fiber metal laminate. Compos Part B Eng 2019;176:107277. [CrossRef]

- Zhou G, Wang W, Peng M. Functionalized aramid nanofibers prepared by polymerization induced self-assembly for simultaneously reinforcing and toughening of epoxy and carbon fiber/epoxy multiscale composite. Compos Sci Technol 2018;168:312–9. [CrossRef]

- Rajhi, AA. Mechanical Characterization of Hybrid Nano-Filled Glass/Epoxy Composites. Polymers (Basel) 2022;14:4852. [CrossRef]

- Ao X, Crouse R, González C, Wang DY. Impact of nanohybrid on the performance of non-reinforced biocomposites and glass-fiber reinforced biocomposites: Synthesis, mechanical properties, and fire behavior. Constr Build Mater 2024;436:136922. [CrossRef]

- Kavimani V, Gopal PM, Stalin B, Karthick A, Arivukkarasan S, Bharani M. Effect of Graphene Oxide-Boron Nitride-Based Dual Fillers on Mechanical Behavior of Epoxy/Glass Fiber Composites. J Nanomater 2021;2021:5047641. [CrossRef]

- Guru Mahesh G, Jayakrishna K. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Nano Filled Glass Fiber Reinforced Composites. Mater Today Proc 2019;22:3305–11. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Lai Y, Zhao S, Chen H, Li R, Wang Y. Optically transparent and high-strength glass-fabric reinforced composite. Compos Sci Technol 2024;245:110338. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasa Perumal KP, Selvarajan L, Manikandan KP, Velmurugan C. Mechanical, tribological, and surface morphological studies on the effects of hybrid ilmenite and silicon dioxide fillers on glass fibre reinforced epoxy composites. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2023;146:106095. [CrossRef]

- Duongthipthewa A, Zhou H, Wang Q, Zhou L. Non-additive polymer matrix coated rGO/MXene inks for embedding sensors in prepreg enhancing smart FRP composites. Compos Part B Eng 2024;270:111108. [CrossRef]

- Pathak AK, Borah M, Gupta A, Yokozeki T, Dhakate SR. Improved mechanical properties of carbon fiber/graphene oxide-epoxy hybrid composites. Compos Sci Technol 2016;135:28–38. [CrossRef]

- Han W, Zhou J, Shi Q. Research progress on enhancement mechanism and mechanical properties of FRP composites reinforced with graphene and carbon nanotubes. Alexandria Eng J 2023;64:541 79. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Hui Y, Zhang J, Wang Y, Zhang J, Wang X, et al. Single multifunctional MXene-coated glass fiber for interfacial strengthening, damage self-monitoring, and self-recovery in fiber-reinforced composites. Compos Part B Eng 2023;259:110713. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Liu W, Dai H, Zhang F. Synthesis of a self-assembly amphiphilic sizing agent by RAFT polymerization for improving the interfacial compatibility of short glass fiber-reinforced polypropylene composites. Compos Sci Technol 2022;218:109181. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Zhao D, Jin X, Wang C, Wang D, Ge H. Modifying glass fibers with graphene oxide: Towards high-performance polymer composites. Compos Sci Technol 2014;97:41–5. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Okail M, Alsaleh NA, Farouk WM, Elsheikh A, Abu-Oqail A, Abdelraouf YA, et al. Effect of dispersion of alumina nanoparticles and graphene nanoplatelets on microstructural and mechanical characteristics of hybrid carbon/glass fibers reinforced polymer composite. J Mater Res Technol 2021;14:2624–37. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini A, Raji A. Improved double impact and flexural performance of hybridized glass basalt fiber reinforced composite with graphene nanofiller for lighter aerostructures. Polym Test 2023;125:108107. [CrossRef]

- Shahnaz T, Hayder G, Shah MA, Ramli MZ, Ismail N, Hua CK, et al. Graphene-based nanoarchitecture as a potent cushioning/filler in polymer composites and their applications. J Mater Res Technol 2024;28:2671–98. [CrossRef]

- Ali Z, Yaqoob S, Yu J, Amore AD, Fakhar-e-alam M. Journal of King Saud University - Science A comparative review of processing methods for graphene-based hybrid filler polymer composites and enhanced mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties. J King Saud Univ - Sci 2024;36:103457. [CrossRef]

- Zafar M, Muhammad Imran S, Iqbal I, Azeem M, Chaudhary S, Ahmad S, et al. Graphene-based polymer nanocomposites for energy applications: Recent advancements and future prospects. Results Phys 2024;60:107655. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim A, Klopocinska A, Horvat K, Hamid ZA. Graphene-Based Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Mechanical Properties, and Characterizations 2021;13:2869 1-32.

- Jagadeesh H, Banakar P, Sampathkumaran P, Sailaja RRN, Katiyar JK. Influence of nanographene filler on sliding and abrasive wear behaviour of Bi-directional carbon fiber reinforced epoxy composites. Tribol Int 2024;192:109196. [CrossRef]

- Shunmugasundaram M, Praveen Kumar A, Ahmed Ali Baig M, Kasu Y. Investigation on the Effect of Nano Fillers on Tensile Property of Neem Fiber Composite Fabricated by Vacuum Infused Molding Technique. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2021;1057:012019. [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra S, Sannegowda RR, Rudrappa AK, Basavarajaiah SKK. Enhancement of tensile strength and fracture toughness characteristics of banana fibre reinforced epoxy composites with nano MgO fillers. Next Mater 2024;5:100258. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Hui Y, Zhang J, Wang Y, Zhang J, Wang X, et al. Single multifunctional MXene-coated glass fiber for interfacial strengthening, damage self-monitoring, and self-recovery in fiber-reinforced composites. Compos Part B Eng 2023;259:110713. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).