Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

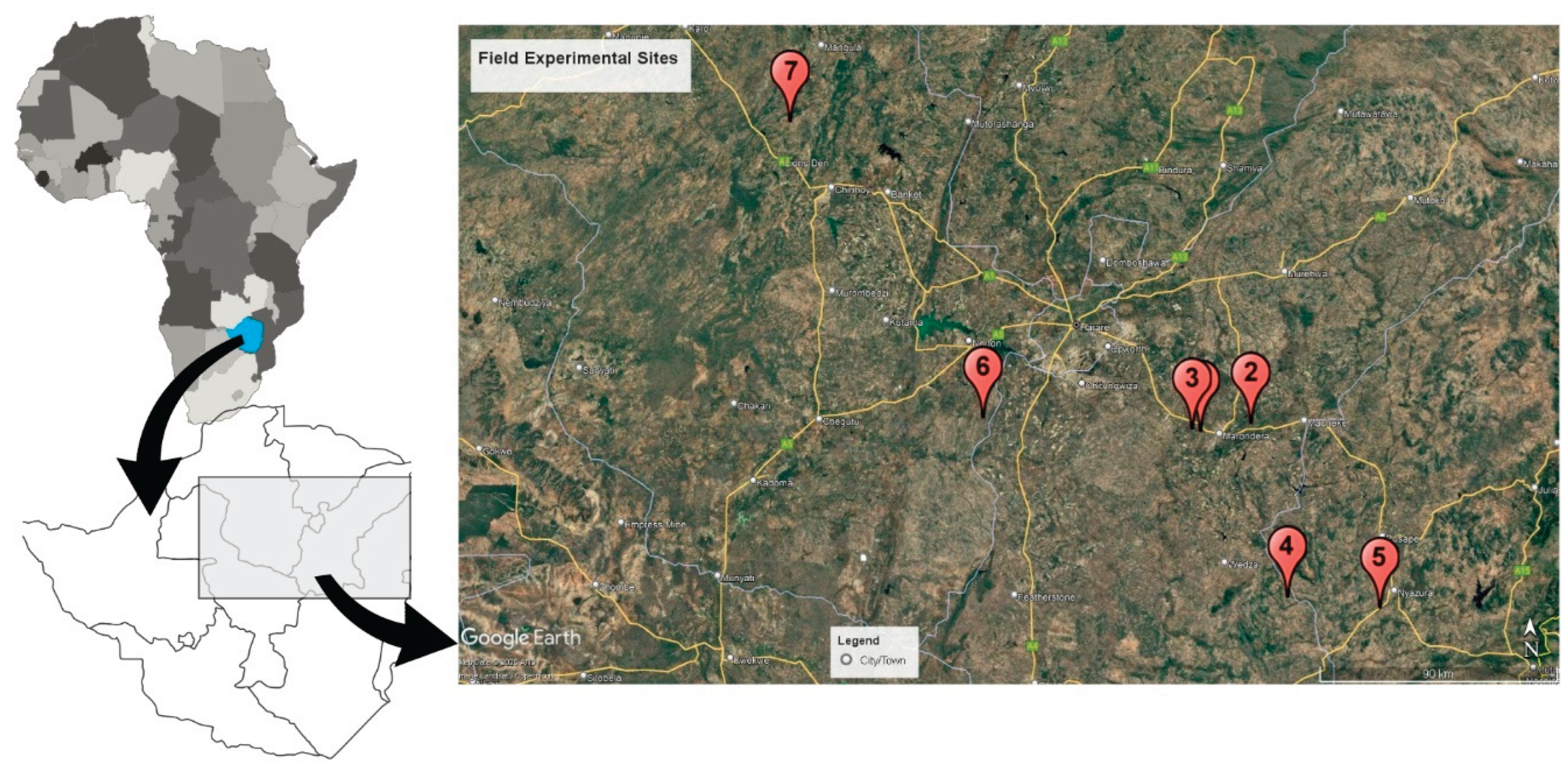

2.1. Experimental Sites and Rhizobia Strain Details

2.2. Trial Establishment and Setup

2.3. Soil Sampling and Soil Chemical Analysis

2.4. Plant Material Sampling and Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

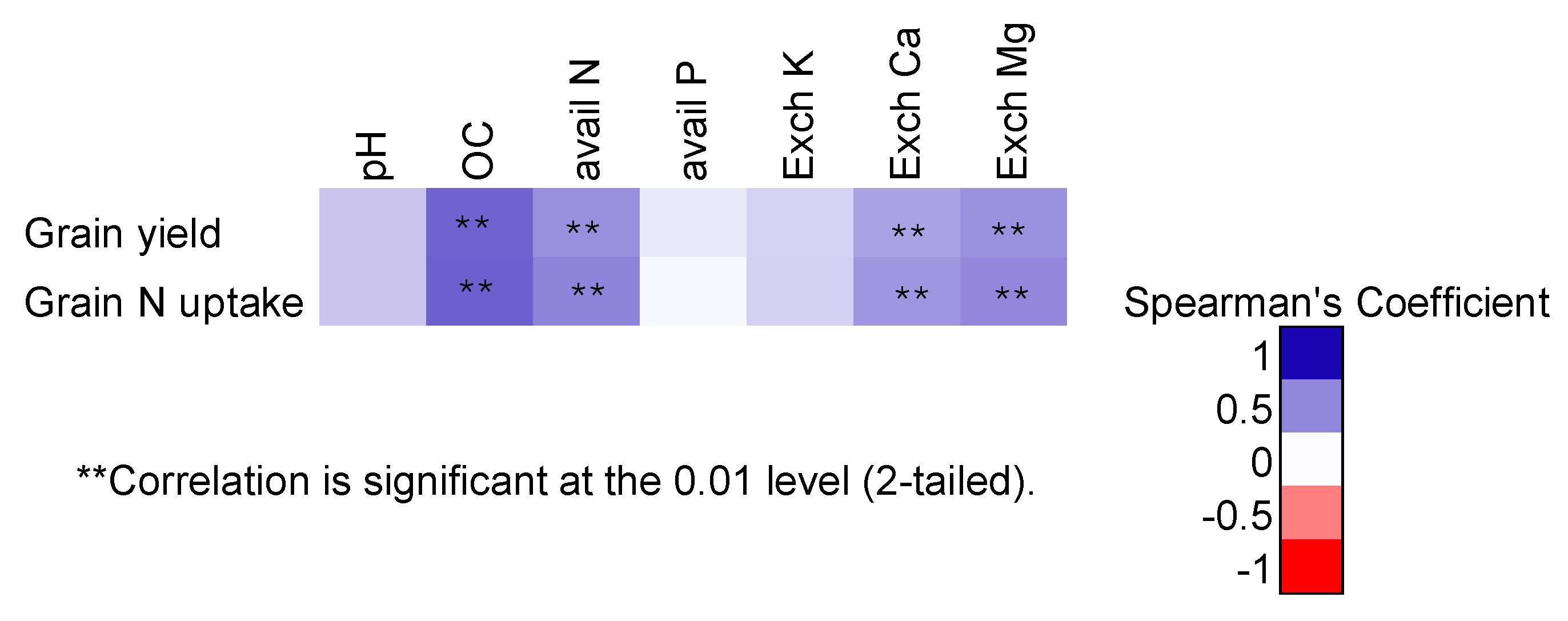

3.1. Study Site Soil Characteristics

3.2. Nodulation Counts and Nodule Mass Soybean During Flowering at the Researcher Managed Sites

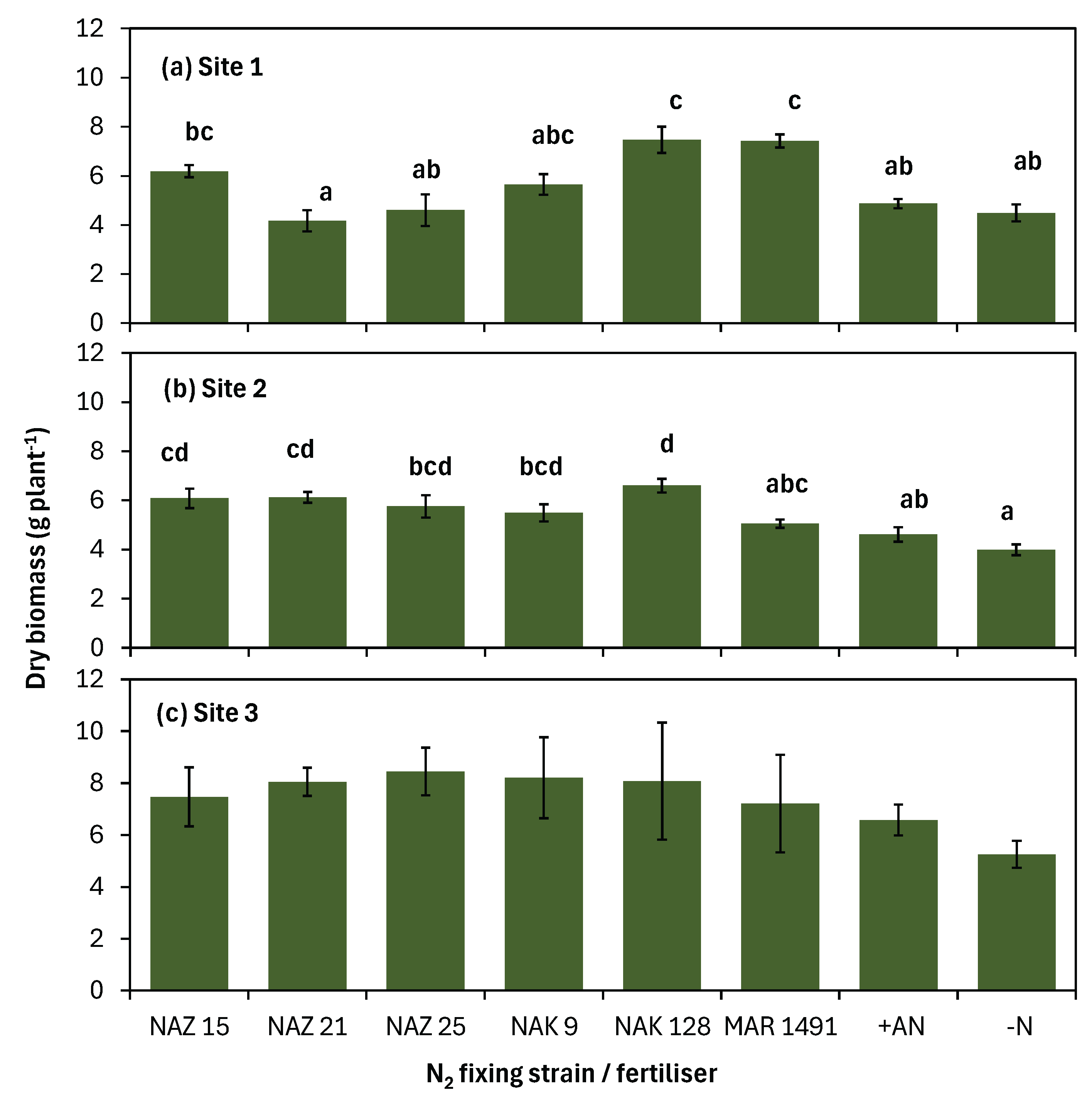

3.3. Biomass Production of Soybean During Flowering at the Researcher Managed Sites

3.4. Soybean Grain Yields at All Sites

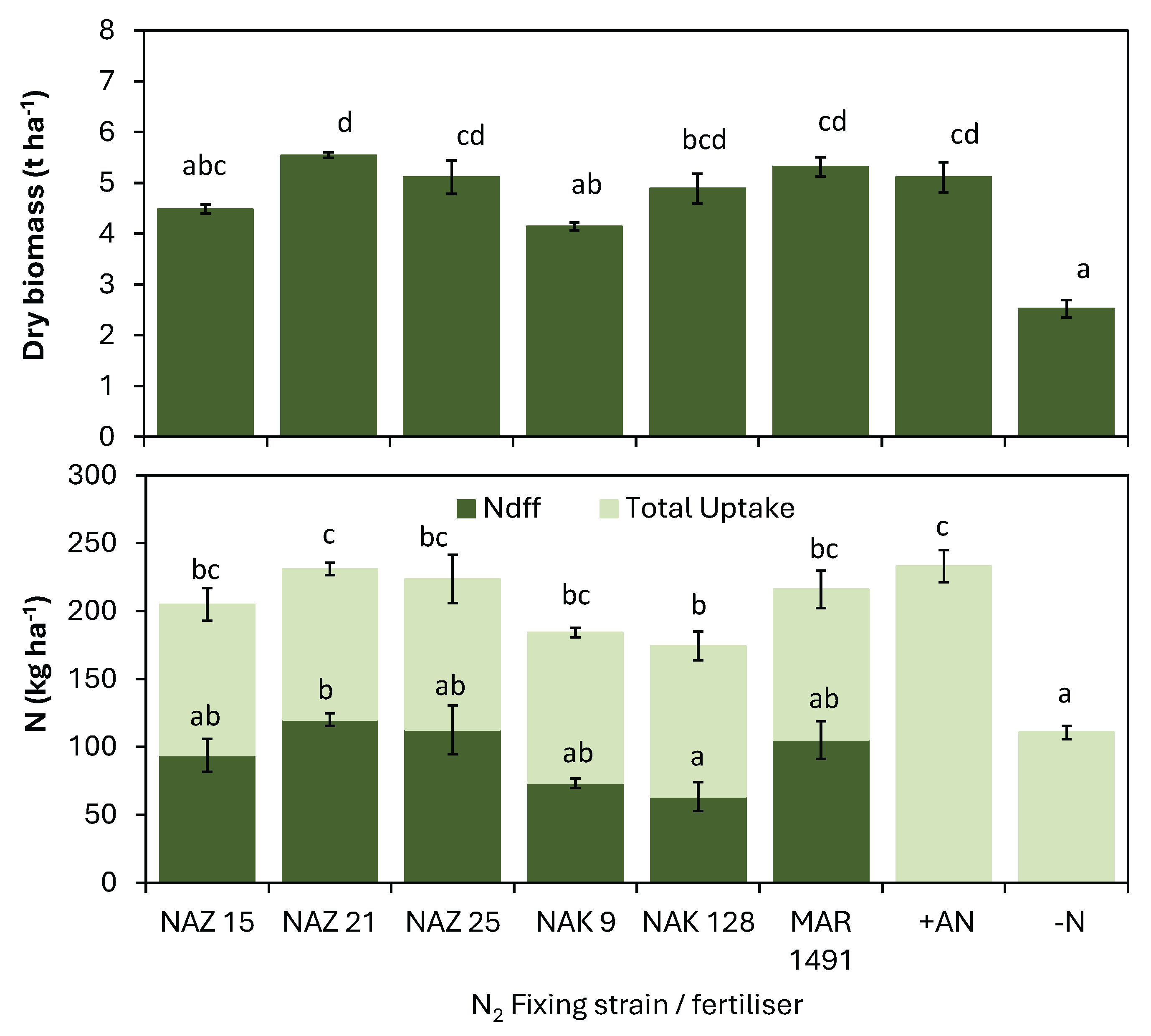

3.5. Nitrogen Uptake and Estimated Nitrogen Derived from Fixation at Site 3

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SPRL | Soil Productivity Research Laboratory |

| CSRI | Chemistry and Soil Research Institute |

| HRI | Horticultural Research Institute |

| KPC | Kushinga Phikelela Agricultural College |

| SNF | Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation |

| OC | Organic Carbon |

References

- Giller, K.E. The successful intensification of smallholder farming in Zimbabwe. LEISA Magazine 2008, 24.2, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. Crops and livestock products. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: 2025.

- Basera, J. Hapson. Soyabean: A strategic crop. In Field Crops, Seed Co Zimbabwe: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2025.

- Zambon, L.M.; Umburanas, R.C.; Schwerz, F.; Sousa, J.B.; Barbosa, E.S.T.; Inoue, L.P.; Dourado-Neto, D.; Reichardt, K. Nitrogen balance and gap of a high yield tropical soybean crop under irrigation. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1233772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desta, M.; Akuma, A.; Minay, M.; Yusuf, Z.; Baye, K. Effects of Indigenous and Commercial Rhizobia on Growth and Nodulation of Soybean (Glycine max L) under Greenhouse Condition. The Open Biotechnology Journal 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kaur, M.; Goyal, R.; Gill, B.S. Physical characteristics and nutritional composition of some new soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) genotypes. J Food Sci Technol 2014, 51, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzeyimana, F.; Onwonga, R.N.; Ayuke, F.O.; Chemining'wa, G.N.; Nabahungu, N.L.; Bigirimana, J.; Noella Josiane, U.K. Determination of abundance and symbiotic effectiveness of native rhizobia nodulating soybean and other legumes in Rwanda. Plant Environ Interact 2024, 5, e10138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanova, I.; Syromiatnykov, Y.; Yakovlieva, A.; Voinash, S.; Orekhovskaya, A.; Vanzha, V.; Akhtyamova, L.; Vashchilin, V.; Arabov, F.; Mehdiyeva, A.; et al. Efficiency of symbiosis between Bradyrhizobium bacteria and soybean plants under various biopreparations. BIO Web of Conferences 2025, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungriaa, M.; Vargas, M.A.T. Environmental factors affecting N2 fixation in grain legumes in the tropics, with an emphasis on Brazil. Field Crops Research 2000, 65, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumbure, A.; Dube, S.; Tauro, T.P. Insights of Microbial Inoculants in Complementing Organic Soil Fertility Management in African Smallholder Farming Systems. In Towards Sustainable Food Production in Africa, 2023. 59–83. [CrossRef]

- Jarecki, W.; Borza, I.M.; Rosan, C.A.; Vicas, S.I.; Domuța, C.G. Soybean Response to Seed Inoculation with Bradyrhizobium japonicum and/or Nitrogen Fertilization. Agriculture 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanonge-Mafaune, G.; Chiduwa, M.S.; Chikwari, E.; Pisa, C. Evaluating the effect of increased rates of rhizobial inoculation on grain legume productivity. Symbiosis 2018, 75, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekanai, V.; Chikowo, R.; Vanlauwe, B. Response of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) to nitrogen, phosphorus and rhizobia inoculation across variable soils in Zimbabwe. Agric Ecosyst Environ 2018, 266, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibeba, A.M.; Kyei-Boahen, S.; Guimaraes, M.F.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungria, M. Feasibility of transference of inoculation-related technologies: A case study of evaluation of soybean rhizobial strains under the agro-climatic conditions of Brazil and Mozambique. Agric Ecosyst Environ 2018, 261, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengeni, R.; Mpepereki, S.; Giller, K.E. Manure and soil properties affect survival and persistence of soyabean nodulating rhizobia in smallholder soils of Zimbabwe. Applied Soil Ecology 2006, 32, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiduwa, M. Improving the legume-rhizobium symbiosis in Zimbabwean agriculture: A study of rhizobia diversity & symbiotic potential focussed on soybean root nodule bacteria. In School of Agricultural Sciences; Murdoch University: Murdoch, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Szczerba, A.; Plazek, A.; Kopec, P.; Wojcik-Jagla, M.; Dubert, F. Effect of different Bradyrhizobium japonicum inoculants on physiological and agronomic traits of soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) associated with different expression of nodulation genes. BMC Plant Biol 2024, 24, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhlovu, K.; Bopape, F.L.; Diale, M.O.; Mpai, T.; Morey, L.; Mtsweni, N.P.; Gerrano, A.S.; Vuuren, A.v.; Babalola, O.O.; Hassen, A.I. Characterization of Nodulation-Compatible Strains of Native Soil Rhizobia from the Rhizosphere of Soya Bean (Glycine max L.) Fields in South Africa. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, R.A.; Yuan, K.; Anh, K.T.; Reckling, M.; Halwani, M.; Egamberdieva, D.; Ohkama-Ohtsu, N.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D. Enhanced Soybean Productivity by Inoculation With Indigenous Bradyrhizobium Strains in Agroecological Conditions of Northeast Germany. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 707080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiyiwa, K.; Mpepereki, S.; Giller, K.E. Physiological diversity of rhizobia nodulating promiscuous soyabean in Zimbabwean soils. Symbiosis 2005, 40, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Fertilizer use by crop in Zimbabwe; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Ingram, J. Tropical Soil Biology and Fertility: A Handbook of Methods. Soil Science 1994, 157, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Analytica Chimica Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okalebo, R.J.; Gathua, K.W.; Woomer, P.L. Laboratory methods of soil and plant analysis: A working manual, 2nd ed.; TSBF-CIAT and SACRED Africa, Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tumbure, A.; Wuta, M.; Mapanda, F. Preliminary evaluation of the effectiveness ofRhizobium leguminosarumbv.viceaestrains in nodulating hairy vetch (Vicia villosa) in the sandy soils of Zimbabwe. South African Journal of Plant and Soil 2013, 30, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shi, F.; Du, J.; Li, L.; Bai, T.; Xing, X. Soil factors that contribute to the abundance and structure of the diazotrophic community and soybean growth, yield, and quality under biochar amendment. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Bisseling, T. Soybean breeders can count on nodules. Trends Plant Sci 2025, 30, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Alla, M.H.; Al-Amri, S.M.; El-Enany, A.-W.E. Enhancing Rhizobium–Legume Symbiosis and Reducing Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Are Potential Options for Mitigating Climate Change. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrod, M. Counting the nodules that count, relationships between seed nitrogen and root nodules. Natural Sciences Education 2022, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikwanha, H. High production costs render soyabean uncompetitive. In The Herald; Zimpapers: Harare, Zimbabwe; p. 2024.

- Omondi, J.O.; Chiduwa, M.S.; Kyei-Boahen, S.; Masikati, P.; Nyagumbo, I. Yield gap decomposition: quantifying factors limiting soybean yield in Southern Africa. npj Sustainable Agriculture 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzeke-Kangara, M.G.; Ligowe, I.S.; Tibu, A.; Gondwe, T.N.; Greathead, H.M.R.; Galdos, M.V. Soil organic carbon and related properties under conservation agriculture and contrasting conventional fields in Northern Malawi. Frontiers in Soil Science 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyawasha, R.W.; Falconnier, G.N.; Todoroff, P.; Wadoux, A.M.J.C.; Chikowo, R.; Coquereau, A.; Leroux, L.; Jahel, C.; Corbeels, M.; Cardinael, R. Drivers of soil organic carbon stocks at village scale in a sub-humid region of Zimbabwe. Catena 2025, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanepoel, P.A.; Botha, P.R.; Truter, W.F.; Surridge-Talbot, A.K. The effect of soil carbon on symbiotic nitrogen fixation and symbioticRhizobiumpopulations in soil withTrifolium repensas host plant. African Journal of Range & Forage Science 2011, 28, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezomba, H.; Mtambanengwe, F.; Tittonell, P.; Mapfumo, P. Practical assessment of soil degradation on smallholder farmers' fields in Zimbabwe: Integrating local knowledge and scientific diagnostic indicators. Catena 2017, 156, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipomho, J.; Rugare, J.T.; Mabasa, S.; Zingore, S.; Mashingaidze, A.B.; Chikowo, R. Short-term impacts of soil nutrient management on maize (Zea mays L.) productivity and weed dynamics along a toposequence in Eastern Zimbabwe. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutuma, S.P.; Okello, J.J.; Karanja, N.K.; Woomer, P.L. Smallholder farmers’ use and profitability of legume inoculants in Western Kenya. African Crop Science Journal 2014, 22, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- GRDC. Soybean nutrition and fertiliser. In GRDC Grownotes, Grains Research and Development Corporation: Australia, 2016.

- Kebonye, N.M.; John, K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Zhou, Y.; Agyeman, P.C.; Seletlo, Z.; Heung, B.; Scholten, T. Major overlap in plant and soil organic carbon hotspots across Africa. Sci Total Environ 2024, 951, 175476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Details /Names | pH 1 | Soil OC % | Mineral N (ppm) | Avail P (ppm) | Exchangeable bases (me %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | Ca | Mg | ||||||

| 1 | SPRL | 4.5 | 0.35 | 22 | 5 | 0.09 | 0.64 | 0.38 |

| 2 | Kushinga P.C. | 5.3 | 1.08 | 11 | 37 | 0.42 | 2.4 | 1.51 |

| 3 | Horticulture Research Institute | 4.9 | 1.28 | 23 | 19.6 | 1.02 | 3.63 | 0.20 |

| 4 | Wedza | 5.0 | 0.23 | 5 | 4 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.35 |

| 5 | Rusape/Makoni | 5.1 | 1.35 | 44 | 2 | 0.25 | 9.41 | 4.1 |

| 6 | Mhondoro | 4.7 | 1.06 | 29 | 2 | 0.56 | 5.35 | 2.83 |

| 7 | Chinhoyi | 5.6 | 1.20 | 28 | 9 | 0.74 | 6.43 | 4.3 |

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N fixing strain / fertilizer | Nodules plant-1 | Fresh nodule mass plant-1 (g) | Nodules plant-1 | Fresh nodule mass plant-1 (g) | Nodules plant-1 | Fresh nodule mass plant-1 (g) |

| NAZ 15 | 36d ±1 | 0.98c ±0.07 | 25d ±1 | 0.38bc ±0.09 | 25b ±2 | 0.79cd ±0.11 |

| NAZ 21 | 24bcd ±2 | 0.57ab ±0.06 | 13cd ±1 | 0.38bc ±0.05 | 10a ±2 | 0.42abc ±0.05 |

| NAZ 25 | 7ab ±1 | 0.59ab ±0.03 | 11abc ±1 | 0.40bc ±0.04 | 17ab ±4 | 0.82cd ±0.16 |

| NAK 9 | 17abc ±2 | 0.60ab ±0.05 | 11abc ±1 | 0.22b ±0.02 | 10a ±2 | 0.43abc ±0.04 |

| NAK 128 | 27cd ±4 | 0.84bc ±0.07 | 12bcd ±1 | 0.43c ±0.04 | 22ab ±2 | 1.00d ±0.10 |

| MAR 1491 | 24bcd ±1 | 0.88bc ±0.04 | 16cd ±1 | 0.23bc ±0.04 | 21ab ±2 | 0.73bcd ±0.10 |

| +AN | 1a ±0 | 0.00a ±0 | 0.4ab ±0 | 0.04a ±0.02 | 12a ±4 | 0.37a ±0.05 |

| -N | 2a ±1 | 0.15a ±0.06 | 0.1a ±0 | 0.01a ±0.01 | 10a ±2 | 0.40ab ±0.08 |

| Significance | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** | *** |

| N fixing strain / fertilizer | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 5 | Site 4 | Site 6 | Site 7 | Site 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain yield (t ha-1) | |||||||

| NAZ 15 | 1.84b ±0.14 | 1.47b ±0.08 | 2.15ab ±0.16 | 0.81b ±0.09 | 1.06 ±0.04 | 1.12a ±0.12 | 3.31b ±0.21 |

| NAZ 21 | 1.31ab ±0.17 | 2.10c ±0.07 | 2.56b ±0.22 | 0.86b ±0.13 | 1.13 ±0.14 | 1.63ab ±0.11 | 3.28b ±0.10 |

| NAZ 25 | 1.70b ±0.12 | 1.63b ±0.06 | 2.41b ±0.30 | 1.08b ±0.16 | 1.28 ±0.21 | 1.73ab ±0.24 | 3.27b ±0.25 |

| NAK 9 | 1.08a ±0.12 | 1.45ab ±0.09 | 2.88b ±0.17 | 0.70b ±0.08 | 1.30 ±0.23 | 1.60ab ±0.19 | 2.43a ±0.13 |

| NAK 128 | 1.69b ±0.16 | 1.59b ±0.12 | 2.34b ±0.18 | 0.77b ±0.06 | 0.75 ±0.08 | 0.83a ±0.16 | 2.90ab ±0.07 |

| MAR 1491 | 1.63ab ±0.14 | 1.70bc ±0.13 | 1.99ab ±0.28 | 0.63ab ±0.10 | 1.59 ±0.30 | 2.35b ±0.36 | 3.26b ±0.17 |

| +AN | 1.83b ±0.08 | 1.75bc ±0.08 | 2.29b ±0.25 | 0.30ab ±0.03 | 1.07 ±0.16 | 1.61ab ±0.15 | 3.47b ±0.18 |

| -N | 1.39ab ±0.06 | 1.02a ±0.08 | 1.23a ±0.19 | 0.16a ±0.06 | 0.77 ±0.15 | 1.49ab ±0.20 | 1.61a ±0.07 |

| Significance | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | * | * |

| Grain N Uptake (kg N / ha-1) | |||||||

| NAZ 15 | 107.7b ±7.6 | 86.4b ±4.2 | 145.2ab ±13.6 | 52.4c ±5.4 | 62.1 ±7.6 | 70.9ab ±11.6 | 106.20b ±7.95 |

| NAZ 21 | 77.1ab ±9.8 | 103.0b ±8.6 | 156.2b ±14.3 | 58.7c ±10.3 | 60.9 ±6.3 | 93.0ab ±5.9 | 106.87b ±6.60 |

| NAZ 25 | 99.1ab ±7.2 | 95.5b ±7.2 | 148.3ab ±16.4 | 64.4c ±7.3 | 73.6 ±12.8 | 103.8ab ±14.5 | 104.58b ±9.72 |

| NAK 9 | 61.6a ±6.4 | 68.2ab ±9.0 | 182.4b ±12.6 | 42.7bc ±5.1 | 71.6 ±17.3 | 100.3ab ±13.8 | 77.33b ±3.72 |

| NAK 128 | 99.4ab ±9.3 | 92.9b ±12.9 | 141.4ab ±15.4 | 41.8bc ±4.8 | 37.6 ±4.8 | 52.9a ±11.5 | 66.35ab ±10.33 |

| MAR 1491 | 95.0ab ±8.0 | 94.4b ±6.3 | 121.0ab ±21.9 | 41.3bc ±7.8 | 96.1 ±21.2 | 126.5b ±20.9 | 97.25b ±8.30 |

| +AN | 113.8b ±2.7 | 86.8b ±6.5 | 150.1b ±15.4 | 17.3ab ±1.9 | 51.2 ±5.7 | 100.2ab ±13.8 | 106.91b ±7.58 |

| -N | 67.8a ±12.9 | 43.4a ±3.4 | 76.9a ±11.5 | 10.0a ±3.6 | 42.7 ±10.7 | 91.4ab ±15.4 | 50.80a ±1.45 |

| Significance | * | *** | *** | *** | ns | * | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).