Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermented Milk

2.2. Animals and Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Growth Performance

2.5. Diarrhoea-Related Indicators

2.6. Apparent Digestibility of Nutrients

2.7. Serum Biochemical Indicators

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Supplemental Fermented Milk on Growth Performance and Diarrhea Indexes of Suckling and Weaning Piglets

3.2. Effect of Supplemental Fermented Milk on Nutrient Digestibility of Lactating-Weaning Piglets

3.3. Effect of Supplemental Fermented Milk on Serum Inflammatory Indexes in Suckling and Weaning Piglets

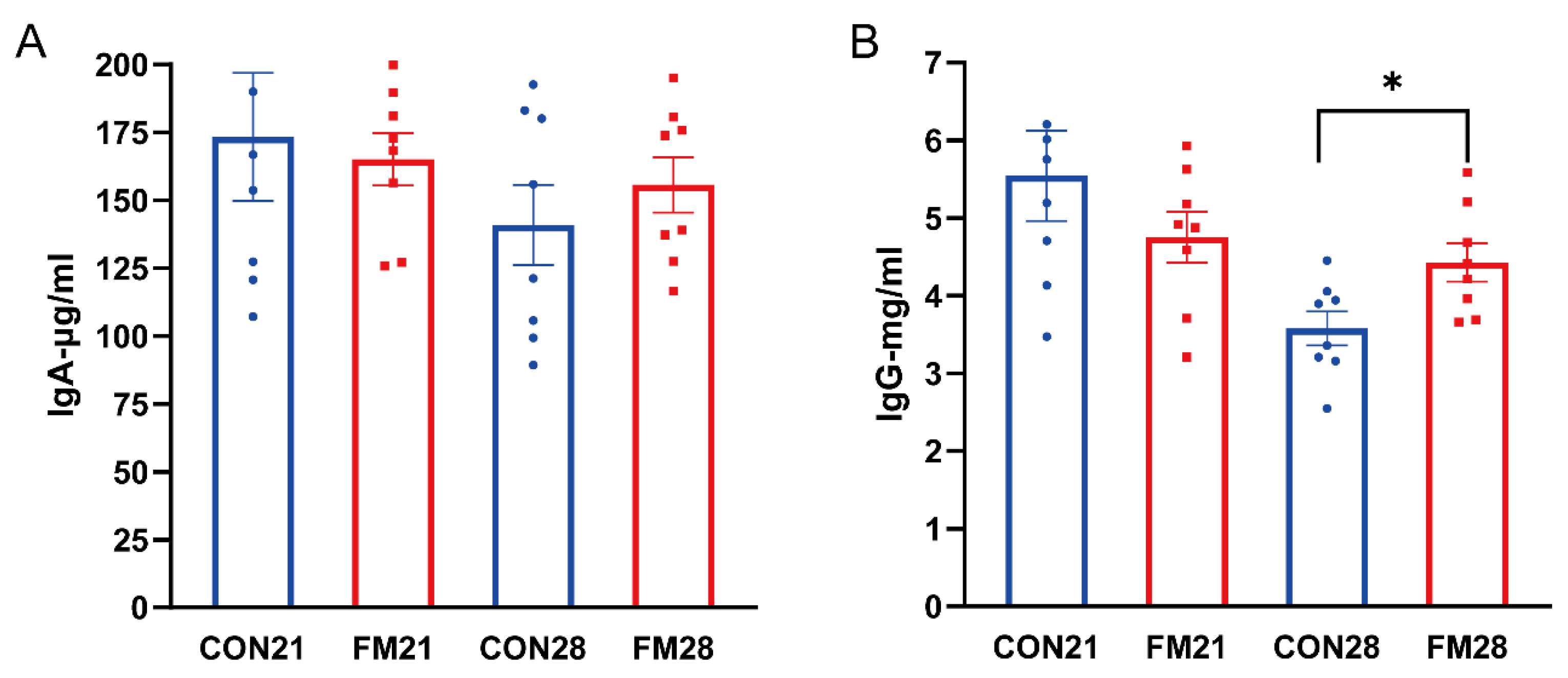

3.4. Effect of Supplemental Fermented Milk on Serum Immunoglobulin Content in Suckling and Weaning Piglets

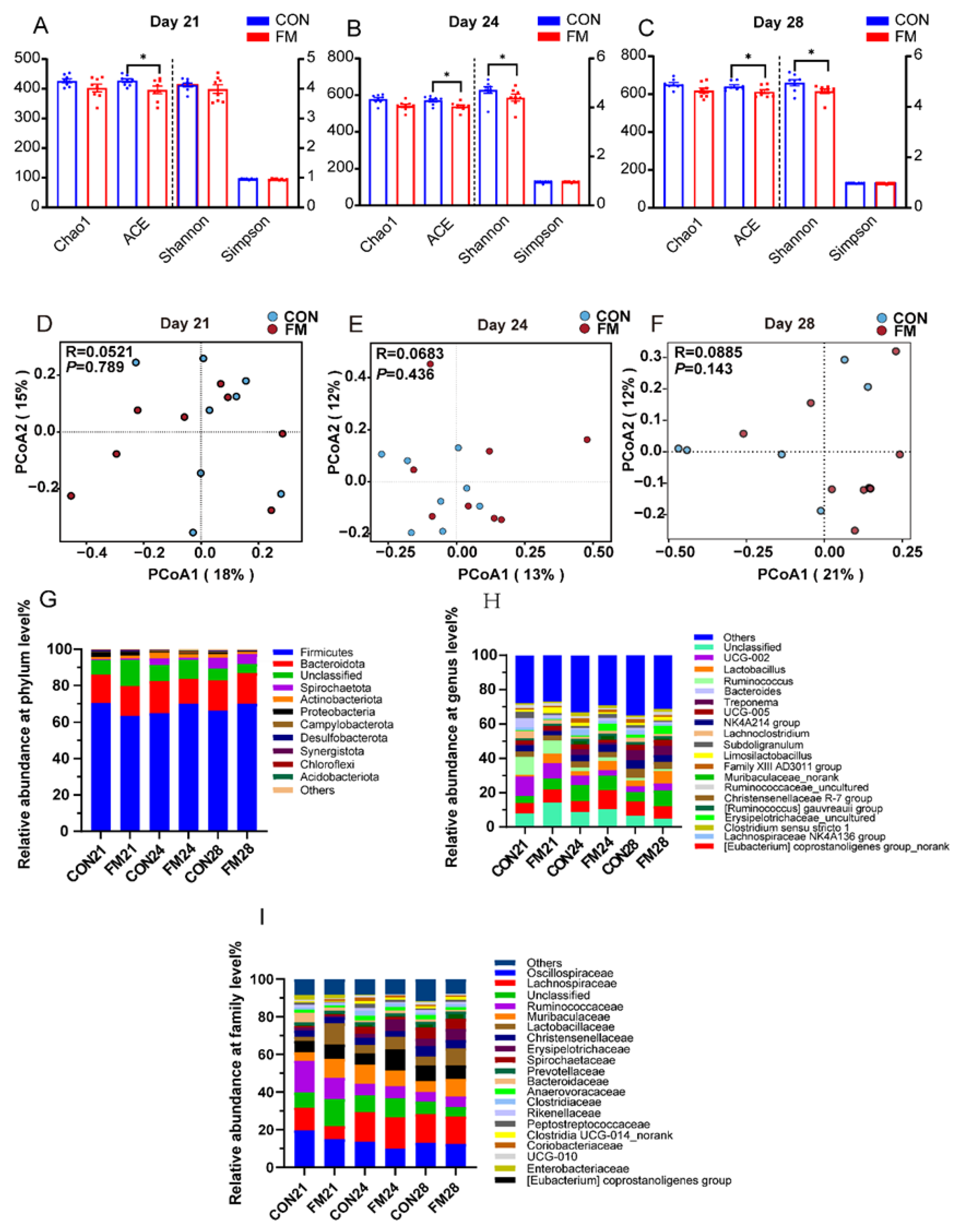

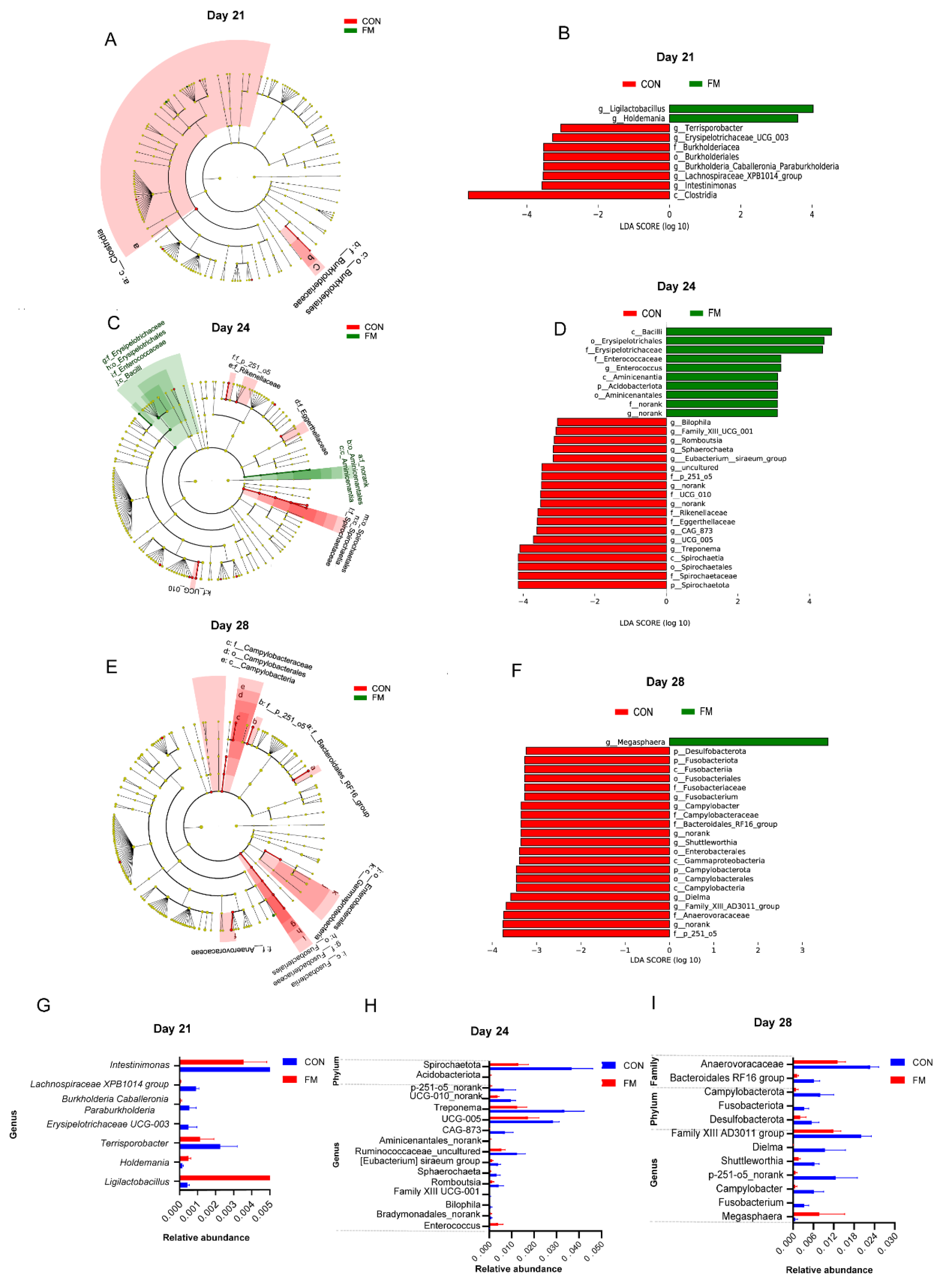

3.5. Effect of Supplemental Fermented Milk on the Structure of Fecal Microbiota in Suckling and Weaning Piglets

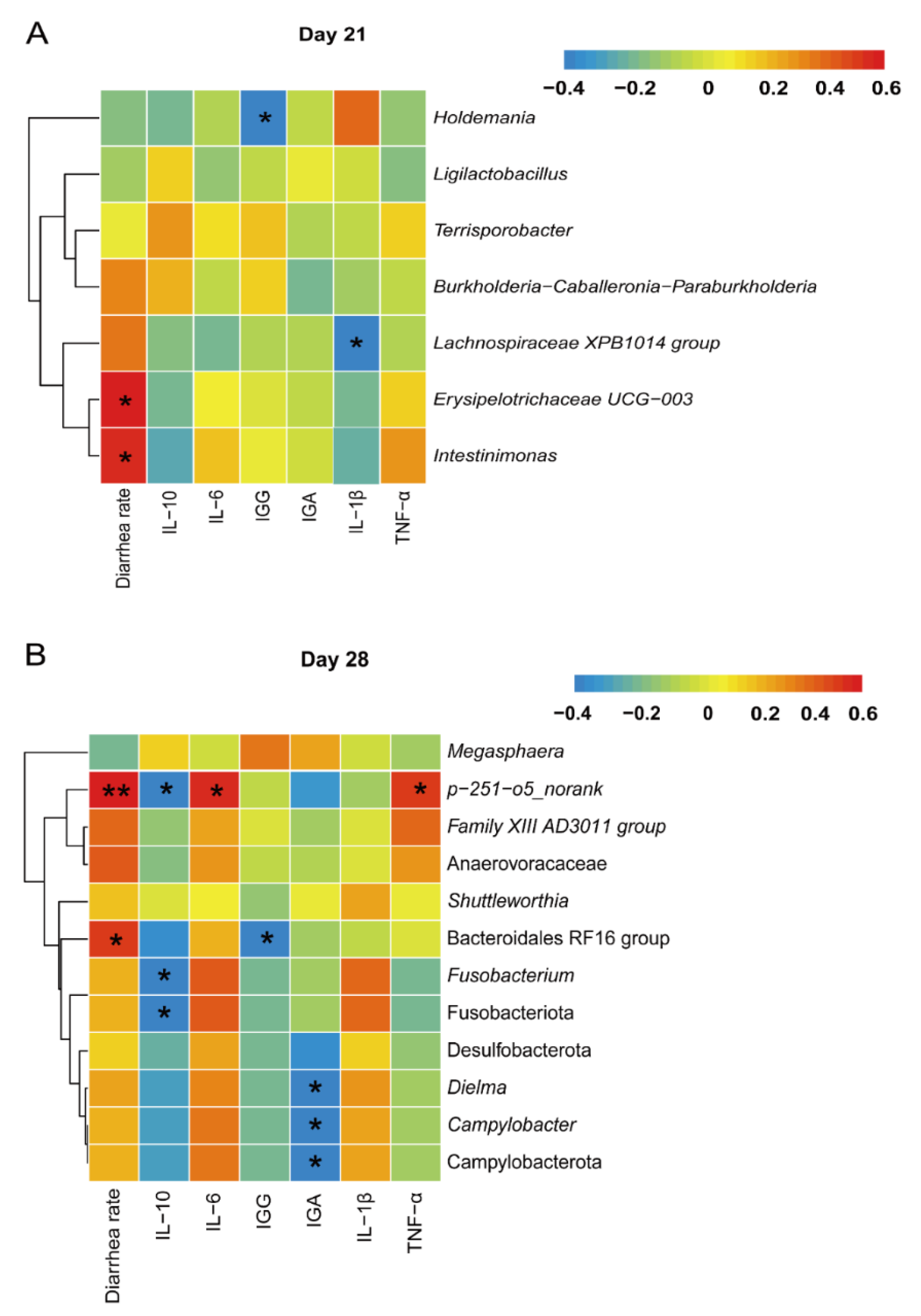

3.6. Correlation Analysis of Fecal Microbiota and Differential Phenotypic Indicators in Suckling and Weaning Piglets

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson, L. H., Hanford, K. J. & Jensen, A. H. Estrus and fertility in lactating sows and piglet performance as influenced by limited nursing. J Anim Sci 53, 1419-1423 (1981). https://doi.org/10.2527/jas1982.5361419x. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q. et al. Weaning Alters Intestinal Gene Expression Involved in Nutrient Metabolism by Shaping Gut Microbiota in Pigs. Front Microbiol 11, 694 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00694. [CrossRef]

- Gresse, R. et al. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Postweaning Piglets: Understanding the Keys to Health. Trends Microbiol 25, 851-873 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.004. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X. et al. Nutritional Intervention for the Intestinal Development and Health of Weaned Pigs. Front Vet Sci 6, 46 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00046. [CrossRef]

- Long, S. et al. Mixed organic acids as antibiotic substitutes improve performance, serum immunity, intestinal morphology and microbiota for weaned piglets. Animal Feed Science and Technology 235, 23-32 (2018).

- Houdijk, J. G. M., Bosch, M. W., Verstegen, M. W. A. & Berenpas, H. J. Effects of dietary oligosaccharides on the growth performance and faecal characteristics of young growing pigs. Animal Feed Science and Technology 71, 35-48 (1998).

- Tian, S., Wang, J., Yu, H., Wang, J. & Zhu, W. Changes in Ileal Microbial Composition and Microbial Metabolism by an Early-Life Galacto-Oligosaccharides Intervention in a Neonatal Porcine Model. Nutrients 11 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081753. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Tian, S., Yu, H., Wang, J. & Zhu, W. Response of Colonic Mucosa-Associated Microbiota Composition, Mucosal Immune Homeostasis, and Barrier Function to Early Life Galactooligosaccharides Intervention in Suckling Piglets. J Agric Food Chem 67, 578-588 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b05679. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, R., Mortazavian, A. M. & Cruz, A. G. Viability of probiotic microorganisms in cheese during production and storage: a review. Dairy Sci Technol 91, 283-308 (2011).

- Lin, A., Yan, X., Wang, H., Su, Y. & Zhu, W. Effects of lactic acid bacteria-fermented formula milk supplementation on ileal microbiota, transcriptomic profile, and mucosal immunity in weaned piglets. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 13, 113 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-022-00762-8. [CrossRef]

- Rateliffe, B., Cole, C. B., Fuller, R. & Newport, M. J. The effect of yoghurt and milk fermented with a porcine intestinal strain of Lactobacillus reuteri on the performance and gastrointestinal flora of pigs weaned at two days of age. Food Microbiology 3, 203-211 (1986).

- Marquardt, R. R. et al. Passive protective effect of egg-yolk antibodies against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88+ infection in neonatal and early-weaned piglets. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 23, 283-288 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01249.x. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z. L., Zhang, J., Wu, G. & Zhu, W. Y. Utilization of amino acids by bacteria from the pig small intestine. Amino Acids 39, 1201-1215 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-010-0556-9. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. et al. Dietary chlorogenic acid improves growth performance of weaned pigs through maintaining antioxidant capacity and intestinal digestion and absorption function. J Anim Sci 96, 1108-1118 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skx078. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. et al. Differential Effects of Lactobacillus casei Strain Shirota on Patients With Constipation Regarding Stool Consistency in China. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 25, 148-158 (2019). https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm17085. [CrossRef]

- Peters, A. et al. Metabolites of lactic acid bacteria present in fermented foods are highly potent agonists of human hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 3. PLoS Genet 15, e1008145 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008145. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. et al. Combined supplementation of Lactobacillus fermentum and Pediococcus acidilactici promoted growth performance, alleviated inflammation, and modulated intestinal microbiota in weaned pigs. BMC Vet Res 15, 239 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-1991-9. [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F., Pasolli, E. & Ercolini, D. The food-gut axis: lactic acid bacteria and their link to food, the gut microbiome and human health. FEMS Microbiol Rev 44, 454-489 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuaa015. [CrossRef]

- Griet, M. et al. Soluble factors from Lactobacillus reuteri CRL1098 have anti-inflammatory effects in acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. PLoS One 9, e110027 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110027. [CrossRef]

- Woo, I. K., Hyun, J. H., Jang, H. J., Lee, N. K. & Paik, H. D. Probiotic Pediococcus acidilactici Strains Exert Anti-inflammatory Effects by Regulating Intracellular Signaling Pathways in LPS-Induced RAW 264.7 Cells. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-024-10263-x. [CrossRef]

- Lin, A. et al. Effects of lactic acid bacteria-fermented formula milk supplementation on colonic microbiota and mucosal transcriptome profile of weaned piglets. Animal 17, 100959 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2023.100959. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. et al. Protective approaches and mechanisms of microencapsulation to the survival of probiotic bacteria during processing, storage and gastrointestinal digestion: A review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 59, 2863-2878 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2017.1377684. [CrossRef]

- Guarner, F. & Malagelada, J. R. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet 361, 512-519 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12489-0. [CrossRef]

- Lallès, J. P., Bosi, P., Smidt, H. & Stokes, C. R. Nutritional management of gut health in pigs around weaning. Proc Nutr Soc 66, 260-268 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0029665107005484. [CrossRef]

- Conway, S., Hart, A., Clark, A. & Harvey, I. Does eating yogurt prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhoea? A placebo-controlled randomised controlled trial in general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 57, 953-959 (2007). https://doi.org/10.3399/096016407782604811. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W., Rutz, S., Crellin, N. K., Valdez, P. A. & Hymowitz, S. G. Regulation and functions of the IL-10 family of cytokines in inflammation and disease. Annu Rev Immunol 29, 71-109 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101312. [CrossRef]

- Pourcyrous, M., Nolan, V. G., Goodwin, A., Davis, S. L. & Buddington, R. K. Fecal short-chain fatty acids of very-low-birth-weight preterm infants fed expressed breast milk or formula. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 59, 725-731 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1097/mpg.0000000000000515. [CrossRef]

- Sangild, P. T., Vonderohe, C., Melendez Hebib, V. & Burrin, D. G. Potential Benefits of Bovine Colostrum in Pediatric Nutrition and Health. Nutrients 13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082551. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. et al. Protective effects of Bacillus licheniformis on growth performance, gut barrier functions, immunity and serum metabolome in lipopolysaccharide-challenged weaned piglets. Front Immunol 14, 1140564 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1140564. [CrossRef]

- Mahony, J., McDonnell, B., Casey, E. & van Sinderen, D. Phage-Host Interactions of Cheese-Making Lactic Acid Bacteria. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 7, 267-285 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-food-041715-033322. [CrossRef]

- Jintao, W. Effects of Fermented Feed on Growth Performance,Plasma Biochemical Parameters and Digestibility of Dietary Components in Weaned Piglets. Journal of the Chinese Cereals and Oils Association (2009).

- Jinlong, Z. et al. Effects of fermented product of mulberry leaf on growth performance, serum biochemical indexes and intestinal morphology of broiler chickens. Feed Industry (2017).

- Yu, X. & Yingting, L. Research Progress of Oligosaccharides on Intestinal Flora in Animals. Feed Review (2011).

- Ramadan, Z. et al. Fecal microbiota of cats with naturally occurring chronic diarrhea assessed using 16S rRNA gene 454-pyrosequencing before and after dietary treatment. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 28, 59-65 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.12261. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. et al. Changes in the diversity and composition of gut microbiota of weaned piglets after oral administration of Lactobacillus or an antibiotic. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100, 10081-10093 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-016-7845-5. [CrossRef]

- Hai-Feng, W., Hai-Xia, C., Wen-Ming, Z. & Jian-Xin, L. Effects of Compound Acidifiers on Growth Performance and Intestinal Microbial Communities of Weaned Piglets. Chin J Anim Sci (2011).

- Mishra, D. K., Verma, A. K., Agarwal, N., Mondal, S. K. & Singh, P. Effect of Dietary Supplementation of Probiotics on Growth Performance, Nutrients Digestibility and Faecal Microbiology in Weaned Piglets. Animal Nutrition & Feed Technology 14, 283 (2014).

- Wang, G. et al. Lactobacillus reuteri improves the development and maturation of fecal microbiota in piglets through mother-to-infant microbe and metabolite vertical transmission. Microbiome 10, 211 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-022-01336-6. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. et al. Isolation and genomic characterization of five novel strains of Erysipelotrichaceae from commercial pigs. Bmc Microbiol 21, 125 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-021-02193-3. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S. et al. Late gestation diet supplementation of resin acid-enriched composition increases sow colostrum immunoglobulin G content, piglet colostrum intake and improve sow gut microbiota. Animal 13, 1599-1606 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1017/s1751731118003518. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y. et al. A Combination of Baicalin and Berberine Hydrochloride Ameliorates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis by Modulating Colon Gut Microbiota. J Med Food 25, 853-862 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2021.K.0173. [CrossRef]

- Allos, B. M. Campylobacter jejuni Infections: update on emerging issues and trends. Clin Infect Dis 32, 1201-1206 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1086/319760. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C., Song, R., Zhou, J., Jia, Y. & Lu, J. Fermented Bamboo Fiber Improves Productive Performance by Regulating Gut Microbiota and Inhibiting Chronic Inflammation of Sows and Piglets during Late Gestation and Lactation. Microbiol Spectr 11, e0408422 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.04084-22. [CrossRef]

| Items | CON | FM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW (kg) | Day 7 | 2.71 ± 0.14 | 2.99 ± 0.09 | 0.114 |

| Day 14 | 4.40 ± 0.17 | 4.58 ± 0.10 | 0.563 | |

| Day 21 | 6.25 ± 0.18 | 6.44 ± 0.16 | 0.450 | |

| Day 28 | 6.16 ± 0.23 | 6.65 ± 0.134 | 0.099 | |

| ADG (g) | Days 7-14 | 247.98 ± 11.94 | 226.61 ± 11.39 | 0.222 |

| Days 15-21 | 257.03 ± 10.68 | 264.97 ± 14.47 | 0.658 | |

| Days 22-28 | -10.95 ± 12.41 | 30.82 ± 11.27 | 0.027 | |

| ADFI (g) | Days 7-14 | 1.08 ± 0.07 | 2.43 ± 0.19 | < 0.001 |

| Days 15-21 | 3.18 ± 0.36 | 5.13 ± 0.37 | 0.002 | |

| Days 22-28 | 7.85 ± 0.79 | 10.52 ± 2.42 | 0.038 | |

| Items | CON | FM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea rate (%) | Days 7-14 | 1.09 ± 0.45 | 1.8 ± 1.8 | 0.092 |

| Days 15-21 | 3.63 ± 1.18 | 2.06 ± 1.01 | 0.331 | |

| Days 22-28 | 10.99 ± 2.32 | 4.76 ± 0.07 | 0.032 | |

| Diarrhea index | Days 7-14 | 0.036 ± 0.016 | 0.004 ± 0.004 | 0.079 |

| Days 15-21 | 0.109 ± 0.035 | 0.062 ± 0.030 | 0.329 | |

| Days 22-28 | 0.330 ± 0.069 | 0.141 ± 0.73 | 0.031 | |

| Items | CON | FM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days 18-21 | DM | 75.85 ± 1.00 | 73.91 ± 1.66 | 0.256 |

| CP | 71.07 ± 0.89 | 69.22 ± 1.58 | 0.078 | |

| EE | 66.01 ± 2.97 | 64.73 ± 1.45 | 0.065 | |

| CF | 33.08 ± 2.08 | 31.68 ± 3.15 | 0.366 | |

| Ash | 47.83 ± 2.56 | 42.78 ± 2.14 | 0.420 | |

| Days 25-28 | DM | 74.18 ± 1.26 | 74.05 ± 1.17 | 0.136 |

| CP | 67.18 ± 2.48 | 66.54 ± 3.17 | 0.589 | |

| EE | 66.56 ± 1.03 | 63.46 ± 2.78 | 0.062 | |

| CF | 31.95 ± 0.94 | 31.76 ± 1.26 | 0.469 | |

| Ash | 44.99 ± 2.41 | 41.45 ± 3.00 | 0.549 | |

| Items | CON | FM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 21 | IL-1β (pg/mL) | 8.14 ± 0.60 | 11.95 ± 1.19 | 0.024 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 77.28 ± 30.27 | 62.49 ± 7.49 | 0.643 | |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 16.88 ± 1.72 | 16.98 ± 1.13 | 0.963 | |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 11.08 ± 1.69 | 9.09 ± 0.57 | 0.284 | |

| Day 28 | IL-1β (pg/mL) | 10.64 ± 0.61 | 9.66 ± 0.83 | 0.355 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 77.09 ± 8.59 | 53.06 ± 5.82 | 0.036 | |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 6.11 ± 2.93 | 14.48 ± 1.18 | 0.019 | |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 9.87 ± 1.51 | 10.09 ± 0.65 | 0.894 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).