1. Introduction

In 1964, Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig, who

were independently working on a theory of the strong interaction [1,2], proposed the existence of three subatomic

particles. Within this framework they proposed that the strongly interacting

particles, hadrons, could have been explained if they had not been elementary

but made up of smaller elementary particles that were called quarks at the

suggestion of Gell-Mann.

Already in 1961 Gell-Mann had proposed a symmetry

scheme that he called “Eightfold Way” [3], the

scheme was based on the mathematical symmetry known as SU(3) and managed to

classify hadrons into two fundamental groups: mesons and baryons, an idea that

George Zweig had also had in 1964 proposing that both mesons and baryons were

constructed from fundamental particles with fractionary charge. Both went so

far as to demonstrate that some properties of baryons could only be explained

by treating them as triplets of other constituent particles, quarks.

We know that all elementary particles form in

pairs, but we also know that the quarks up (u) and down (d) which

together with the electron and the neutrino belong to the so-called first

generation of elementary particles of the Standard Model, have never been

observed to form in free pairs at threshold energies equal to their mass at

rest. Therefore, the determination of their mass depends on high-energy

observations in collisions between protons in which the number of particles

involved is high and the type of products is usually varied, thus making the

determination of their resting mass complex, as by the principle of confinement

they are free only when confined inside a hadron. In fact, it is possible to

obtain a quark plasma from high-energy hadron collisions but it is not possible

to obtain a spontaneous creation of new quark pairs at a characteristic threshold

energy as in the case of the electron-positron pair and it has been proposed to

occur for a neutrino-antineutrino pair starting from a photon [4].

For what written above, it is usual to assume that

in the first moments after the Big Bang, the universe was extremely hot and

dense and when the universe cooled, the conditions became optimal to give rise

to the building blocks of matter, quarks, electrons and neutrinos. A few

millionths of a second later, the quarks aggregated to produce protons and

neutrons, but this scenario does not explain in any way how and why quarks with

those characteristics were formed.

To estimate the energy of the rest mass of the

first generation of the and quarks, it is mandatory to use the mass of the

proton as the energy reference, so that the rest masses of the

proton-antiproton pair can be used to test a standard procedure for assembling

any hadron.

This chapter will deal with the estimation of the

energy of the “gluon” as a quantum mediator and the mass energy of the and quarks. In fact, it is necessary to consider that

quarks for their fractional origin are closely interconnected with each other,

so it is difficult to directly estimate the pure mass energy of each quark.

This paper presents a theoretical method that uses

the direct electromagnetic interaction between quarks understood as fractional

charges confined within a particle, to estimate the strength of their mutual

hadronic interaction and the physical characteristics of the formed particle.

2. The Electromagnetic Coupling Constant in Bridge Theory

The Bridge Theory (BT) is a self-consistent electromagnetic-relativistic

theory but it is also an emerging way of thinking that tends to resort to

Maxwellian electromagnetism to look for the reason for the laws of nature, thus

simplifying the variety and complexity of the different theoretical approaches

to a single unifying theory.

BT is rooted in the demonstration [5], [6] of a

conjecture [7] on the role of the transverse

component of the Poynting vector in localizing energy and momentum as a quantum

formally and quantitatively in accordance with quantum theory. The quantum is

formed during an interaction between two charged particles whose energy and

momentum are completely transformed into the energy and momentum of an “exchange

photon”. This is a phenomenology completely described in all its complexity in

the reference [8], according to which a pair

of interacting particles, regardless of their electric charge value , produce a Dipole Electromagnetic Source (DEMS)

that localizes in its source zone an energy and a momentum in agreement with that of an exchange photon,

whose wavelength is equal to the minimum interaction distance

achieved by the particles during their approach. The value of action associated

with such a direct free electromagnetic interaction is in general , which value for a pair of particles with electron

charge units without constraints is , with , corresponding to the reciprocal value of the

coupling electromagnetic constant for free interactions .

The coupling constant in BT is not a true constant,

because its theoretical value depends on the electromagnetic structure function

of the DEMS formed by the interaction of two interacting particle of charges

and

, where

and

are dimensionless charges, therefore, the

structure function is defined as:

the

function in the integral at first term at R.s. of the Equation (1) is given by

with

dipole

ratio between the dipole moment per unit of charge and the wavelength of the

DEMS and

polar angle of emission. Using Equation (1) in the case

,

the coupling constant in the case of a pair of two unitary charge is given by

which

value varies, even if slightly, according to the external forces acting on the

DEMS proving that the coupling constant is not a fundamental constant. In

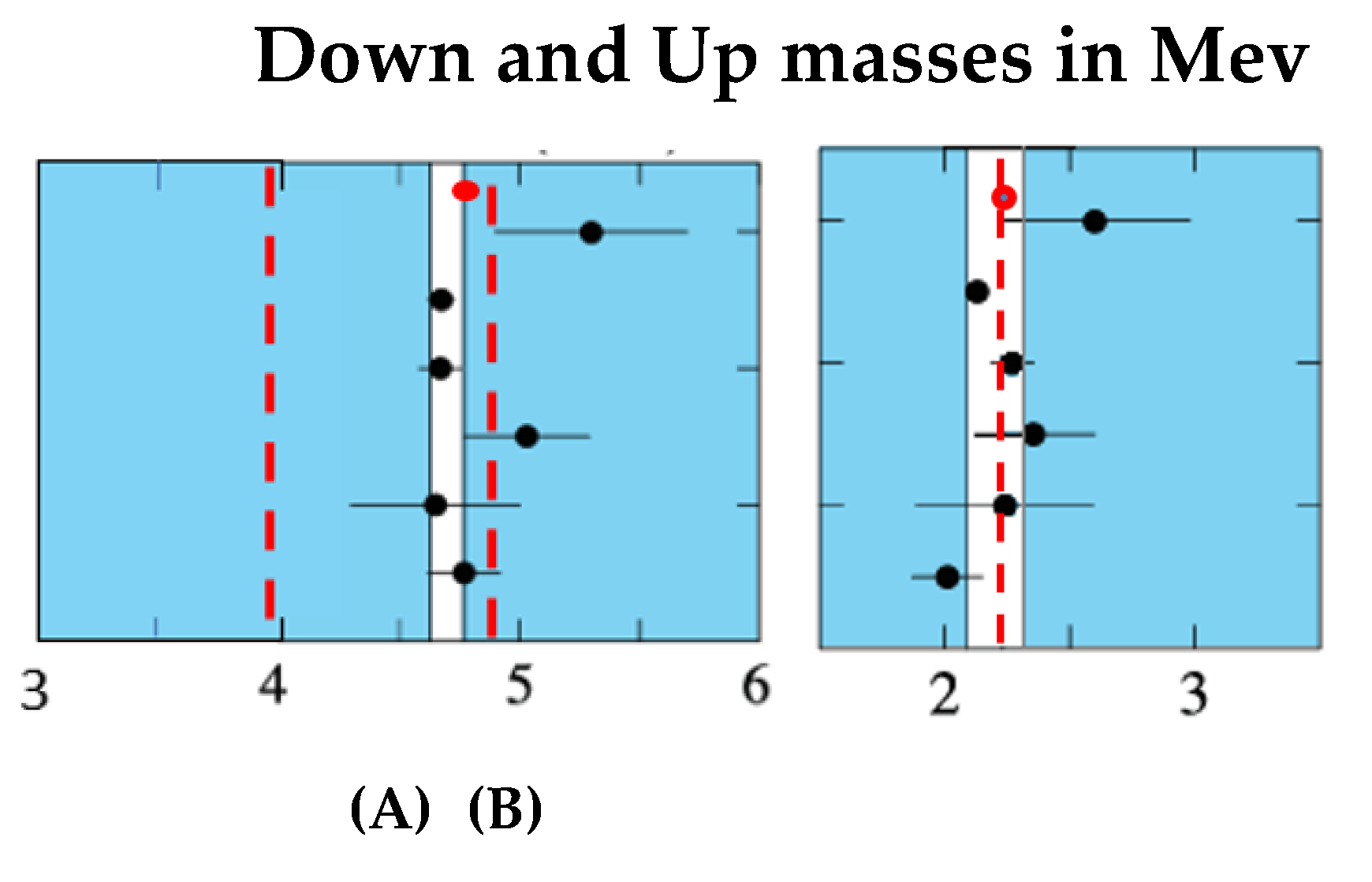

Figure 1

the plot of the coupling constant in Equation (3) as a function of the dipole

ratio.

The

theoretical value of the Sommerfeld’s constant was first calculated in Ref.

[6]

for free interactions between particles, subsequently, the value was revised on

the basis of the experimental value and corrected according to the apparent

angular dimensions of the interacting charges

[8]

, more recently calculated in the

context of the formation model of hydrogen atoms

[9]

and for hydrogenoid atoms with different atomic number values

[10]

:

the best theoretical values obtained in the simulation of the formation of

hydrogen atoms during the orbital capture are

Recently

[11]

,

it has been shown that the electromagnetic interaction of the DEMS applied to a

pair of quarks, if occurring in a particular range of value of the ratio

with

(where

is

defined as the value of the dipole ratio in which the quantum of action

achieves the minimum value) is able to emulate the strong interaction

characterising the variability of the coupling constant

as

a function of the energy scale

in

the particle-particle collision. The coupling value (4) is slightly different

from those that will be used in free interactions between particles or in

interactions between quarks

[11]

because there are different

constraints acting on the interacting system compared to the atomic case. For

an in-depth analysis of the quantum-relativistic characteristics of BT, compare

the references

[8,12,13]

.

3. Strong Exchange Quantum and Standard Coupling Constant

As

shown in Ref.

[8]

, when the pair of free particles

interacts in vacuum forming a DEMS, the energy and momentum localized inside

the source zone of the DEMS behaves as an exchange photon

.

i.e., is a quantum of energy and momentum transferred by a particle to another.

The action involved in free condition is equivalent to the Planck constant but

is slightly greater. The value of the coupling

constant is obtained by Equation (3) using the value mean square ratio

calculated

numerically by using a stochastic process that describes the evolution in

spacetime of the electromagnetic field during the formation of the DEMS.

Considering

the interaction of an incident particle A on a target particle B, the DEMS

collects all the energy of the two particles in their centre of mass in the

form of a quantum of electromagnetic energy. The energy of the DEMS is then

distributed to the particles that emerge in the production phase in the form

with

cumulative

amount of the rest mass energy of the emitted product particles

residual

electromagnetic energy exchanged at the minimal distance of interaction

in

condition of minimum of action inside the DEMS among the emitted particles:

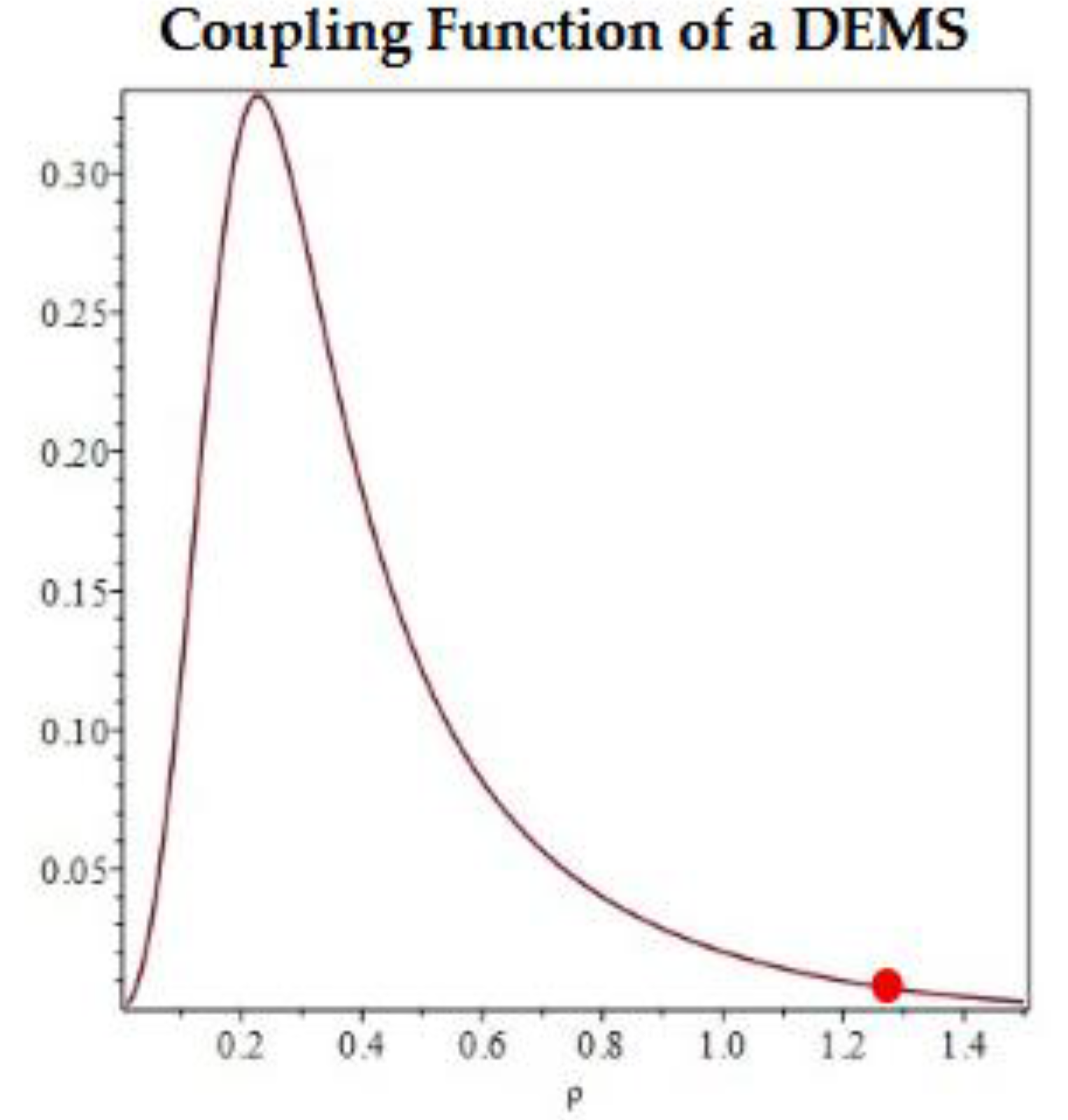

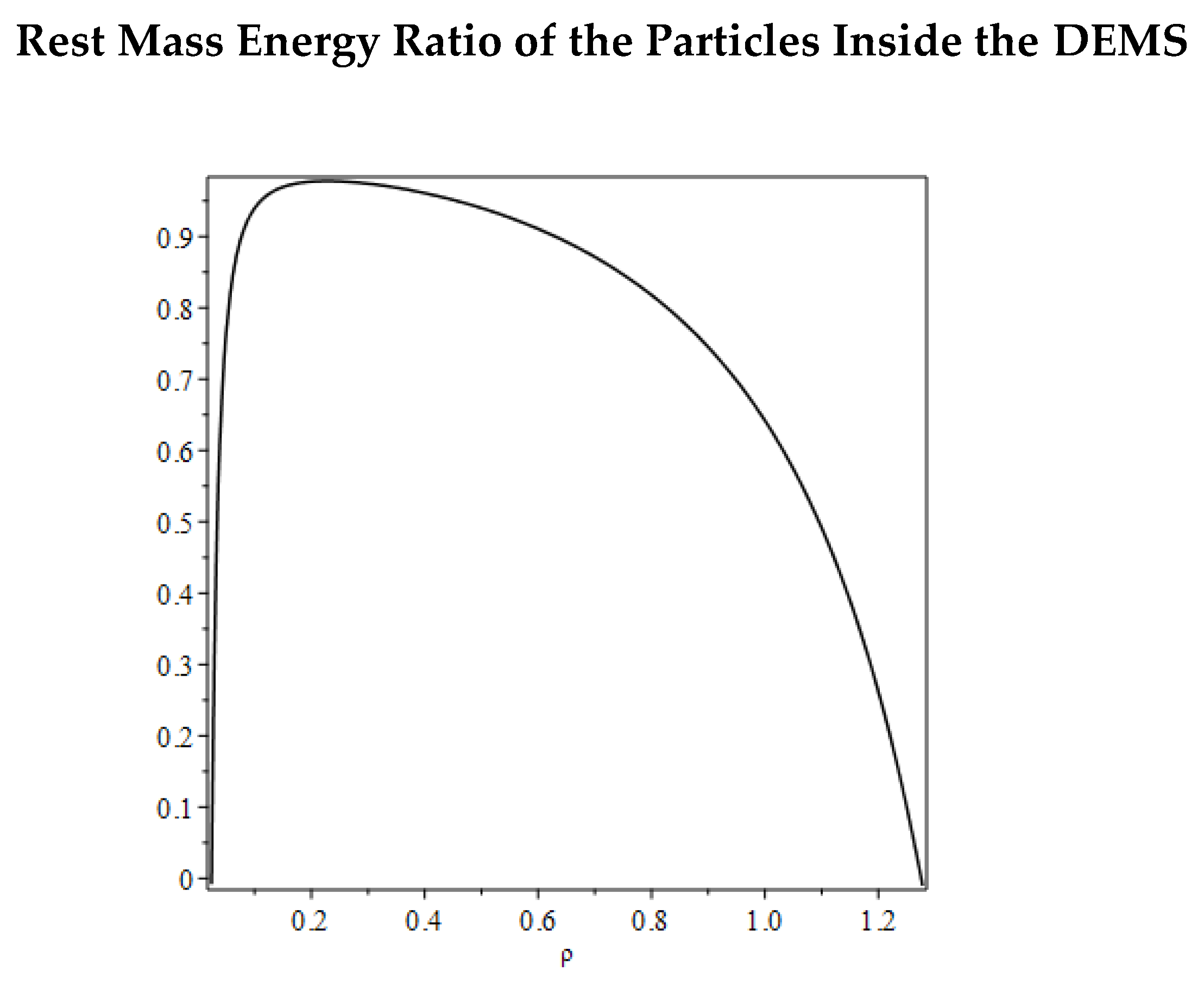

Figure 2 shows the behaviour of the structure function

of the DEMS as a function of the ratio

. The emission of the products

occurs only by releasing energy available to form mass at rest and this can only occur at the minimum value of the DEMS action, when the dipole ratio is

, corresponding to a minimum action

. In this case the structure constant is

.

If one considers the interaction at low energy of a pair of protons

, when the two particles collide the pairs of quarks form tree sub-DEMS

each is an active cell localizing inside a part of energy, before this event, Quarks respond to an internal dynamic described by the model that naturally induces their confinement. In fact, in conditions of minimum action, the configuration of the proton/antiproton system is stable but the quarks maintain a certain degree of internal freedom while remaining bound inside the hadron. This property can be seen in

Figure 2, where for a wide range of values of the dipole ratio

the structure constant of the particle, so the internal action of the proton, changes little. Strong variations in the action value would require large collision energies.

Using for symmetry the equipartition principle, each cell takes an equal portion of the total energy available, therefore, the total energy and of consequence the structure constant of the DEMS is divided in three parts, obtaining the average structure constant of a cell formed by a pair of quarks [

11]

For coherence with the definition of the fine structure constant, is possible to define the value of the coupling constant relative to the strong interaction between two quarks in the form

By analogy with the photon case, using Equation (6) and Equation (7), it is possible to verify that a pair of unit-charged particles would exchange at a minimum direct distance of interaction

inside the sub-DEMS an amount of electromagnetic energy equal to

The energy (9) is less than that of an exchanged photon by the two particles placed at the same distance

Using the ratio of the energies in Equations (9) and (10) is possible to write

It should be noted that the coupling value of the strong interaction

is as known 137 times greater than the electromagnetic coupling value, with an exchange of energy and momentum 137 times lower than the electromagnetic one, therefore one can define the energy of a cell as a Strong Exchange Quantum (SEQ)

Considering the energy of the DEMS in the centre of mass , the energy of the SEQ that has energy of the order of 2/137 of the mass energy of the impinging particle can be considered the energy of a “gluon”.

4. Rest Masses Energy Ratio of a - DEMS

Considering that the energy exchanged between two quarks is due to the SEQ (12), using Equation (5) the total energy of the DEMS corresponds to that of three SEQ plus the rest mass energy

of the three pairs of quarks of the pair of protons. Since the total energy of the pair of protons is

, using the previous definition of quark energy and Equation (5) one writes

Equation (13) is able to estimate the ratio between the total rest mass energy

associated with the three pairs of quarks and the rest mass energy

of the interacting particles

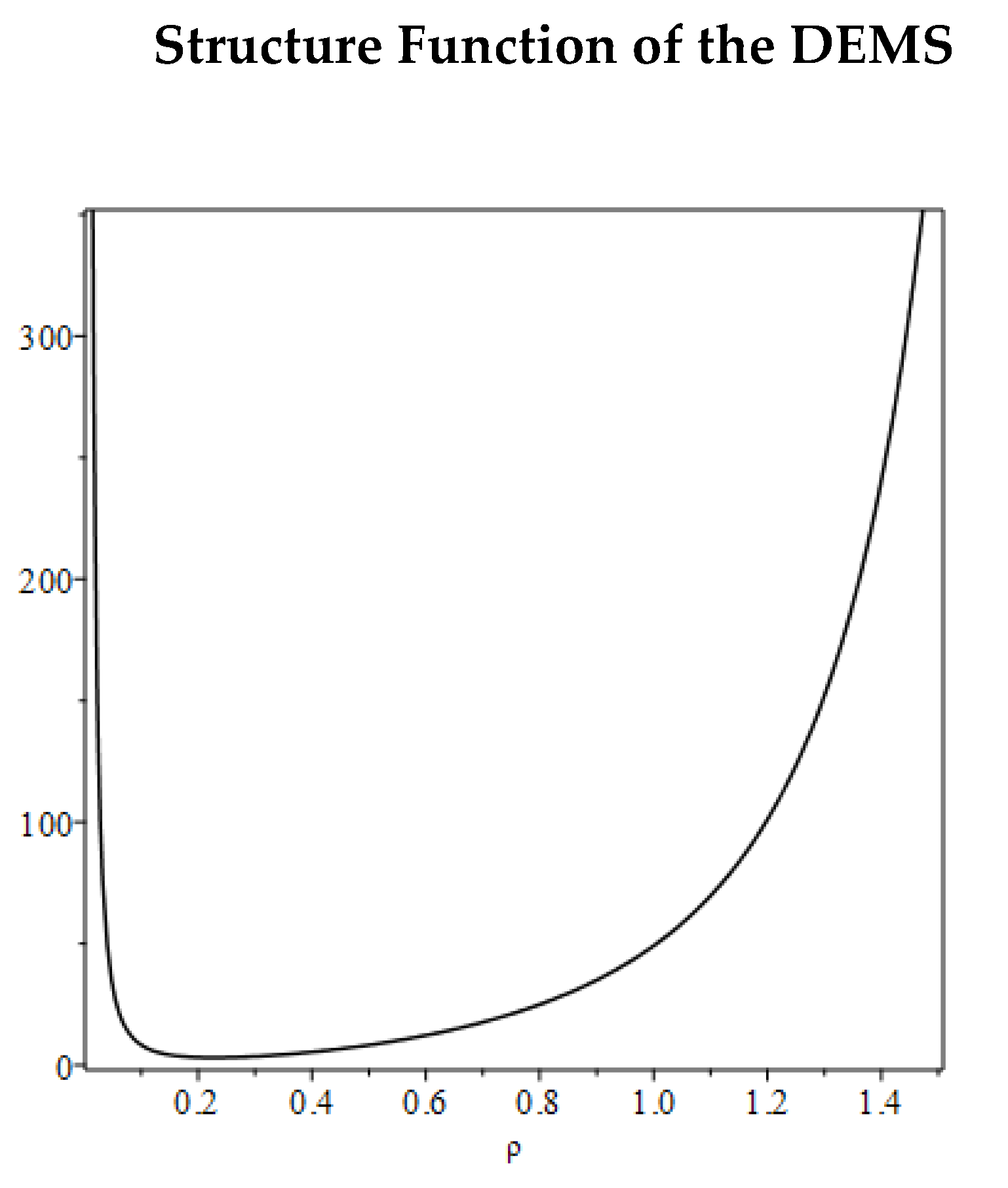

Considering the strong coupling value not as a unitary constant in Equation (8) but as a function of the ratio

as in Equation (3), Equation (14) yields

with

. In

Figure 3 the Equation (15) describes the rest masses energy ratio behaviour as a function of the dipole ratio of the pair. The function (15) achieves its maximum value in

in condition of minimal action. It is important to highlight that the Equation (15) is totally independent from the rest mass energy of the particle from which the elementary particles derive and can be also defined for multiple pairs of particles. In the general form Equation (15) is

from which the energy of the original particle results to be equal to

5. Quarks u and d: Estimation of Masses and Strength from Low Energy interaction

From the energy point of view, the minimum available energy to build a pair of protons is the exact value of the rest mass energy of a pair proton-antiproton equal to

with

[

14], equivalent to

. When proton-antiproton interact forming a DEMS, dividing the total rest mass energy

by

, equal to the number of fundamental cells

formed inside the original DEMS, the average minimum distance of direct interaction of each pair of quarks

within a single cell is given by

After the interaction, during the mixing process of the three pairs of quarks, each quark starts to interact with each of the other three anti-quarks that form the symmetric unit anticharge. This interaction produces a total of sub-DEMS of which 5 sub-DEMS pure pairs and 4 mixed pairs but all for symmetry one supposes acquire an identical amount of energy equal to .

To obtain the total energy of one of the nine sub-cells, one divides its energy by the maximum value of rest mass energy ratio of the DEMS estimated with the Equation (16) (Cf. Equation (17)) by obtaining

from which the wavelength of direct interaction associated to each of the

combinations

of quarks corresponding each to a sub-cell of the original DEMS is

5.1. Estimation of the mass energy of the quark d

To estimate the mass energy associated to the quark

, it needs to consider that after its creation the quark interacts simultaneously with all the other antiquarks of the antiproton

, symmetrically occurs for the antiquark

. The three secondary cells down-antiquark of the type

, symmetrically antidown-quark

, must conserve the value of action

associated with the primitive sub-DEMS, i.e. with the cell

, so by symmetry considering the interactions of the quark

, the original value of action is divided equally among all the three secondary cells marked by the star superscript, in such a way that

so, to calculate the energy of the sub-cell it is necessary to consider 1/3 of the value of action of the primitive cell

divided by the average wavelength (20) of the direct interaction giving

Considering a pair quark-antiquark, to obtain the estimation of the average rest mass energy of a hypothetical isolated quark

, it is necessary to divide by 2-particles the energy (21) of the quarks pair and by the relative multiplicity, 1-pair, active inside the bubble with which the energy is divided. Identically by symmetry, for the average rest mass energy of the quark

. Therefore, the total rest mass energy of the quark

or

is

which corresponds to

. This value is the minimum value of mass energy that the

quark or identically the

quark can have.

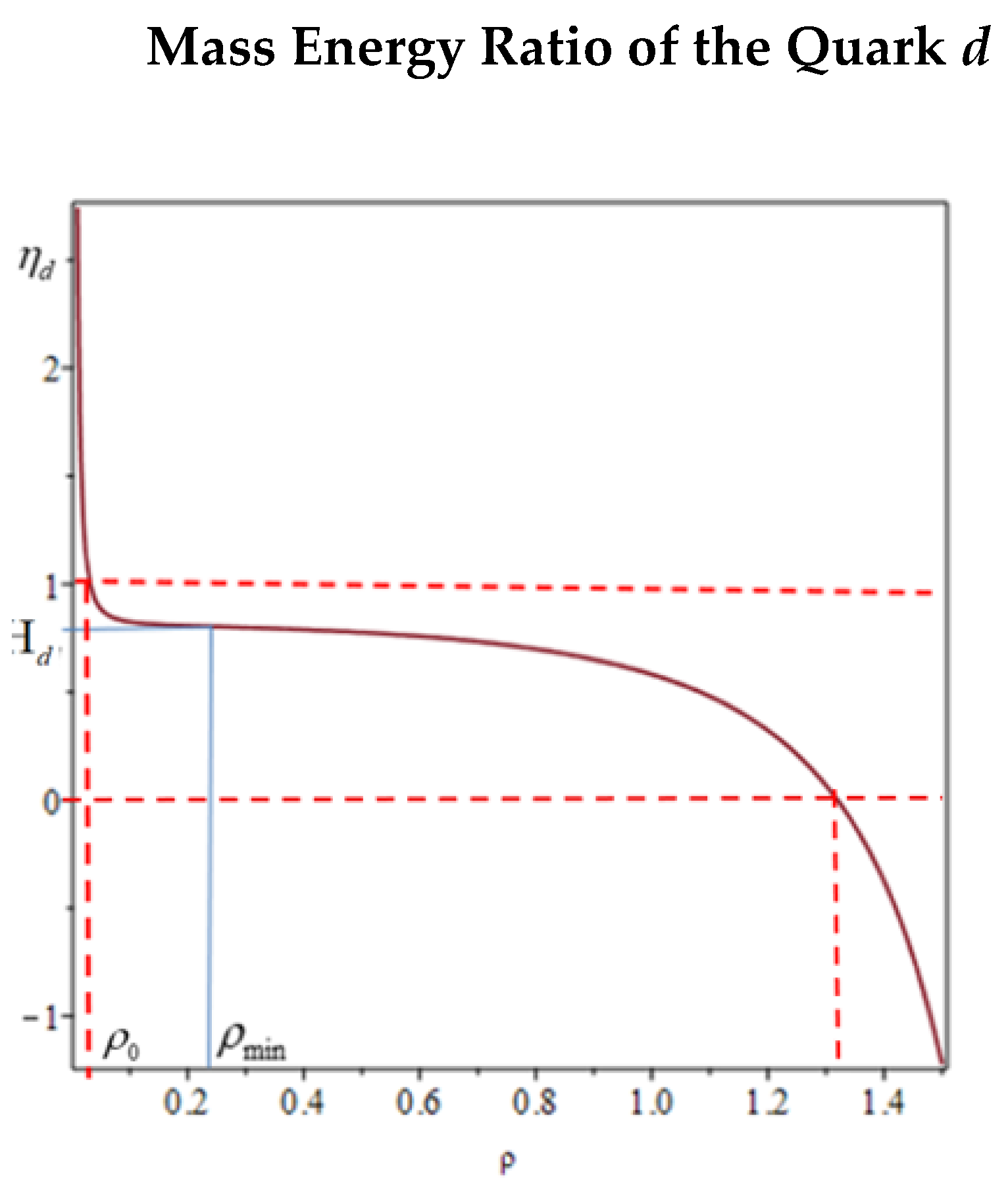

To estimate the upper bound of the mass energy for the interacting

quark, we must account for the energy in (22) plus the additional contribution from its interaction with all surrounding antiquarks, it is necessary to estimate the fraction of energy used to build its total mass. Using the Equation (15) applied to the interaction of the quark

with all the other antiquarks, whose functional behaviour of the ratio is shown in

Figure 3, one obtains

whose value under conditions of minimum action is

.

In conclusion, the total mass energy of the quark

in interaction inside the proton, calculated using Equations (22) and (19) gives

equal to

which is the maximum value of mass energy attainable by that the

quark. As a consequence, the measured energy

of the quark is always confined within the range determined by the associate dipole ratio

(See

Figure 4) one can write

As a consequence of this variability, the mass energy of the quark cannot have an exact value of energy but a statistical distribution of values delimited at left by the resting energy

and at right by the maximal energy of interaction in condition of minimum action

. Since the function of the mass energy ratio (23) for the quark

plotted in

Figure 4, is associated by means of the Equation (24) with the mass energy of the quark in the general form

, considering the interval

shown in the ordinate on the graph in

Figure 4, corresponding to the interval of the dipole ratio

in the first line of Equation (25), the estimated mass energy of the quark averaged on the fraction energy function

is

, in accordance with the experimental estimation

(Cf. Ref. [

14]).

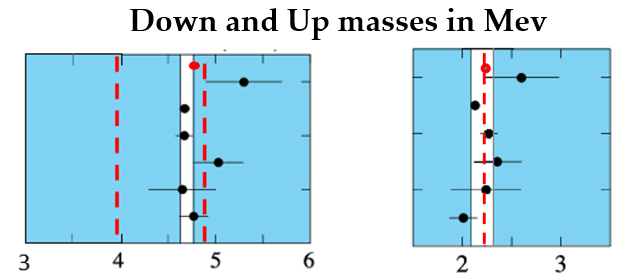

It is also relevant to compare this theoretical value with the quark mass determined via lattice simulations, in which the allowed regions for the quark mass obtained by different authors are compared with the estimation presented in Ref. [

14]. Using a similar graphic scheme of that used in Ref. [

14], in

Figure 6 the range of values (25) that the quark

can acquires as predicted in BT, has been superimpose on the range of energy of mass

[

14] estimated by lattice simulation.

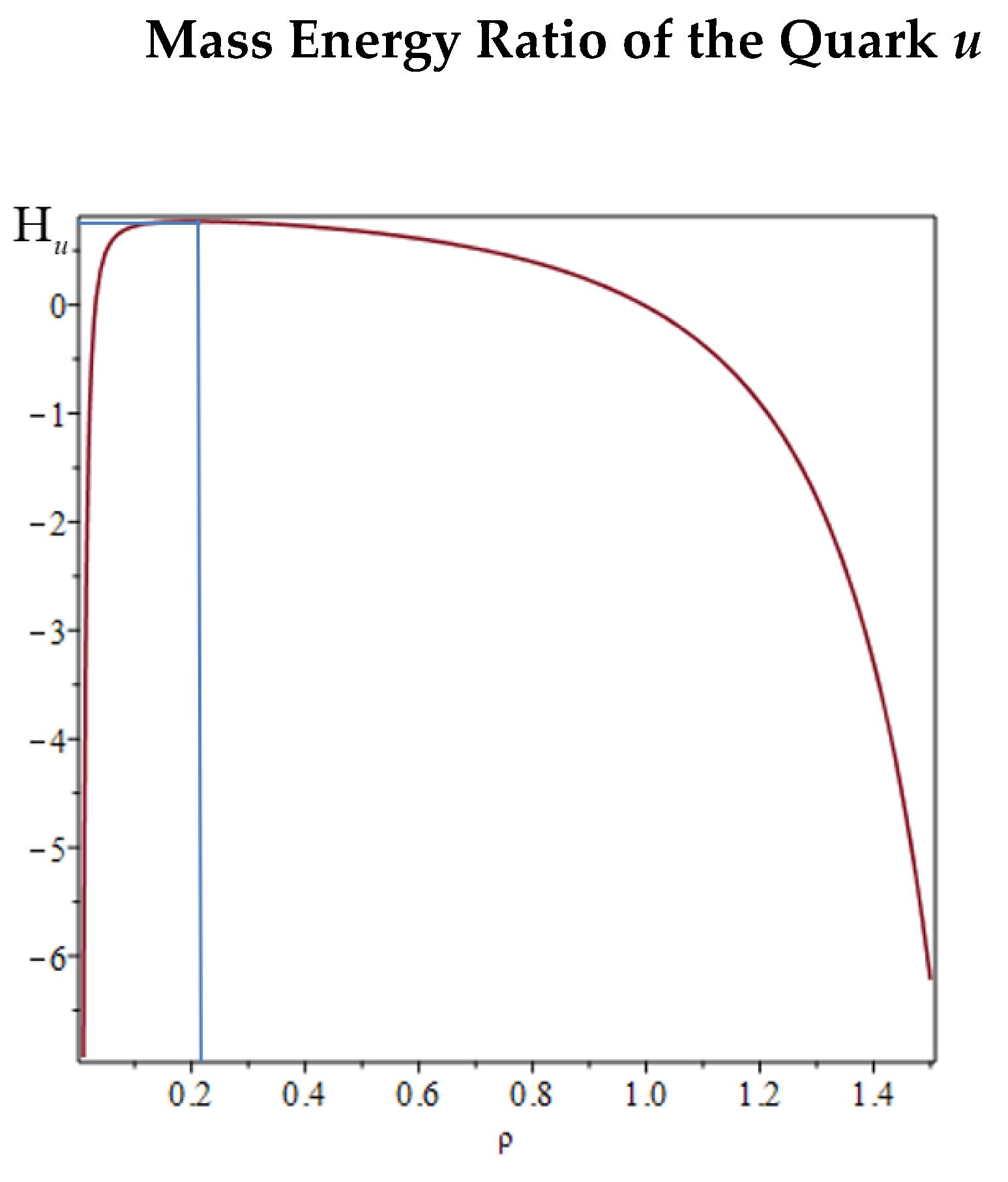

5.2. Estimation of the mass energy of the quark u

To estimate the interaction energy associated with the quark

it is necessary to proceed using the same method used for the quark

in the previous paragraph 5.1, that is, it needs to consider that the two quarks

interact simultaneously with all components of the unit anticharge cluster formed by all three antiquarks

, symmetrically occurs for the anti-quark

. The

sub-cells

must conserve the value of action associated with the primitive cells

so by symmetry its value is divided equally among all the sub-cells marked by the star superscript in such a way that

so, it is necessary to consider

of the value of action of the primitive cell

divided by the average wavelength (38) of the direct interaction quark-antiquark giving as in the previous case

To obtain the estimation of the rest mass energy of a hypothetical isolated quark

, the Equation (26) must be divided by 2-particles of the pair and by 2-identical pairs

simultaneously present in the interaction, therefore,

equal to

. This value lies outside the physical region defined by the model, as it falls beyond the range described by the function

shown in

Figure 5, describing the ratio between the rest mass energy of the quark

and its effective total mass. Therefore, to determinate a physical value of the quark, as made in the previous paragraph, using Equation (16), the Equation (28) in condition of minimum action gives a maximum of

. In conclusion, the mass energy of the quark

u in interaction, calculated using Equations (27) and (19) is

, which corresponds to the value of mass energy that the quark

can have. Therefore, considering that the measured energy of the quark takes value in a single point of the dipole ratio

Unlike the down quark, the up-quark’s configuration allows only a single dominant interaction geometry, resulting in a fixed mass value. Little variations around the value (29) may be allowed in agreement with energy and momentum conservation. The mass energy of the quark in Equation (30) agrees with its experimental estimation

(Cf. Ref. [

14]) and also the comparison with the theoretical values estimated in QCD with lattice simulations give a good agreement within the interval

(Cf. Ref. [

14]).

Figure 6 shows the allowable mass energy ranges of the up and down quarks and their measurements as presented in Ref. [

14].

Figure 6.

(A) Mass energy of the quark

d. The limits in red define the range in which in BT the mass of the quark

d can take values. The interval in white delimits the allowed zone in lattice simulation. In the figure it is evident as the values of the mass energy are close to the average value of

corresponding to the red dot at the top of the chart. (B) Mass energy of the quark

in BT. The red dotted line corresponds to the mass energy of the quark

obtained in condition of minimum of action. It is evident as all the estimated values of the mass energy using lattice simulations in QCD are close to the energy of minimum action. The interval in white delimits the allowed zone estimated with lattice simulation presented in Ref. [

14]. The red dot at the top corresponds to the estimated value of 2.23 MeV of the quark mass

.

Figure 6.

(A) Mass energy of the quark

d. The limits in red define the range in which in BT the mass of the quark

d can take values. The interval in white delimits the allowed zone in lattice simulation. In the figure it is evident as the values of the mass energy are close to the average value of

corresponding to the red dot at the top of the chart. (B) Mass energy of the quark

in BT. The red dotted line corresponds to the mass energy of the quark

obtained in condition of minimum of action. It is evident as all the estimated values of the mass energy using lattice simulations in QCD are close to the energy of minimum action. The interval in white delimits the allowed zone estimated with lattice simulation presented in Ref. [

14]. The red dot at the top corresponds to the estimated value of 2.23 MeV of the quark mass

.

6. Quark Assembly Method for the Construction of Hadron Particles

When quarks form by fractioning, they cannot remain free because the tendency is to reconstruct a unit-charged particle, so they assemble particles with multiple quarks as long as the charge is integer with values (-1, 0, 1). Although particles composed of two to more than three quarks may exist, in this article we will focus on assembling baryons in a cool spacetime leading to a type (B) universe in Equation (35), within which the hydrogen atoms are predominant.

To assemble quarks in number it is necessary to develop a method to manage the multi-body interaction so that quarks can be assembled into more or less complex particles. The method must therefore be simple enough to be handled with at most one free variable and must be able to provide at least one piece of information that can be compared with the corresponding experimental data, so as to be able to determine the correctness of the method and the result obtained.

Currently, at the quantum level the three-body problem is still considered unsolved, so for reasons of methodological consistency we will remain within the BT framework, dealing for the moment only with the assembly method, any particularities of the assembled particle will be treated if necessary.

To establish a general method for assembling baryons it is necessary to consider that quarks must be assembled starting from their rest mass energy and only then consider their mutual interaction by estimating the final energy of the rest mass of the forming particle, within which the exchange of gluons between component quarks takes place.

The following is a concise description of the general assembly method:

-

1-

Structure Function Calculation

From Equation (19), the structure function of the particle formed by

quarks of total rest mass

is given by the sum of the DEMS structure functions formed by all the pairs of quarks considered interacting with each other

-

2-

Mass Energy Ratio Definition

The ratio between the rest mass energy of the component quarks

and the final mass energy of the particle in assembly

given by

it is important because allows to parametrise the mass energy ratio of all the components quarks with respect to the final energy of the total mass energy of the particle.

-

3-

Mass Energy

Using the ratio

at previous point 2 Equation (33), one defines the final rest mass energy function of the considered particle in the form

with binding energy

due to the “gluon” exchange for each pair of quarks. When the energy is negative the particle is stable, when

for

the particle is instable.

-

4-

Semiempirical Adjustment of the Rest Mass

The value of the mass energy of the particle is obtained by varying the parameter with values belonging to the left range of the parameter value that cancels the energy ratio of the rest mass, until the final rest energy of the particle reaches the experimental value of the mass energy for the value of the parameter: .

The value of the parameter defined by the value of the mass of the particle, is proportional to the average distances of mutual interaction of the quarks being proportional to the average length of the dipole moment per unit charge of the DEMS produced.

-

5-

Average Dipole Moment Length.

Since

, the solution of the peculiar value of the parameter

is used to calculate the average dipole momentum per unit of charge as

that define the pseudo-radius of the particle

which is the mean radius of the dipole, that is, the average distance between the interacting quarks measured from the centre of mass of each quark. This pseudo-radius corresponds to the effective charge radius inferred from scattering experiments (charge radius or transition radius), the theoretical value thus obtained, in order for the model to be physically acceptable must be in agreement with the experimentally estimated value.

-

6-

Conservation of the Total Rest Mass During the Quarks Change position

When the value the average dipole moment R of the dipoles changes due to the internal reciprocal movement of the quarks, the total rest mass energy of the assembled hadron for energy conservation cannot change, but the subdivision of energy between the effective rest mass energy of the component quarks and the further amount of rest mass energy of the hadron due to the gluons exchanged between the quarks changes as in Equation (5), increasing or decreasing with the interaction distance with the effect of keeping constant the total energy of the hadron that maintain the same mass energy at rest. The star at right up of the symbols indicates a change from the initial value.

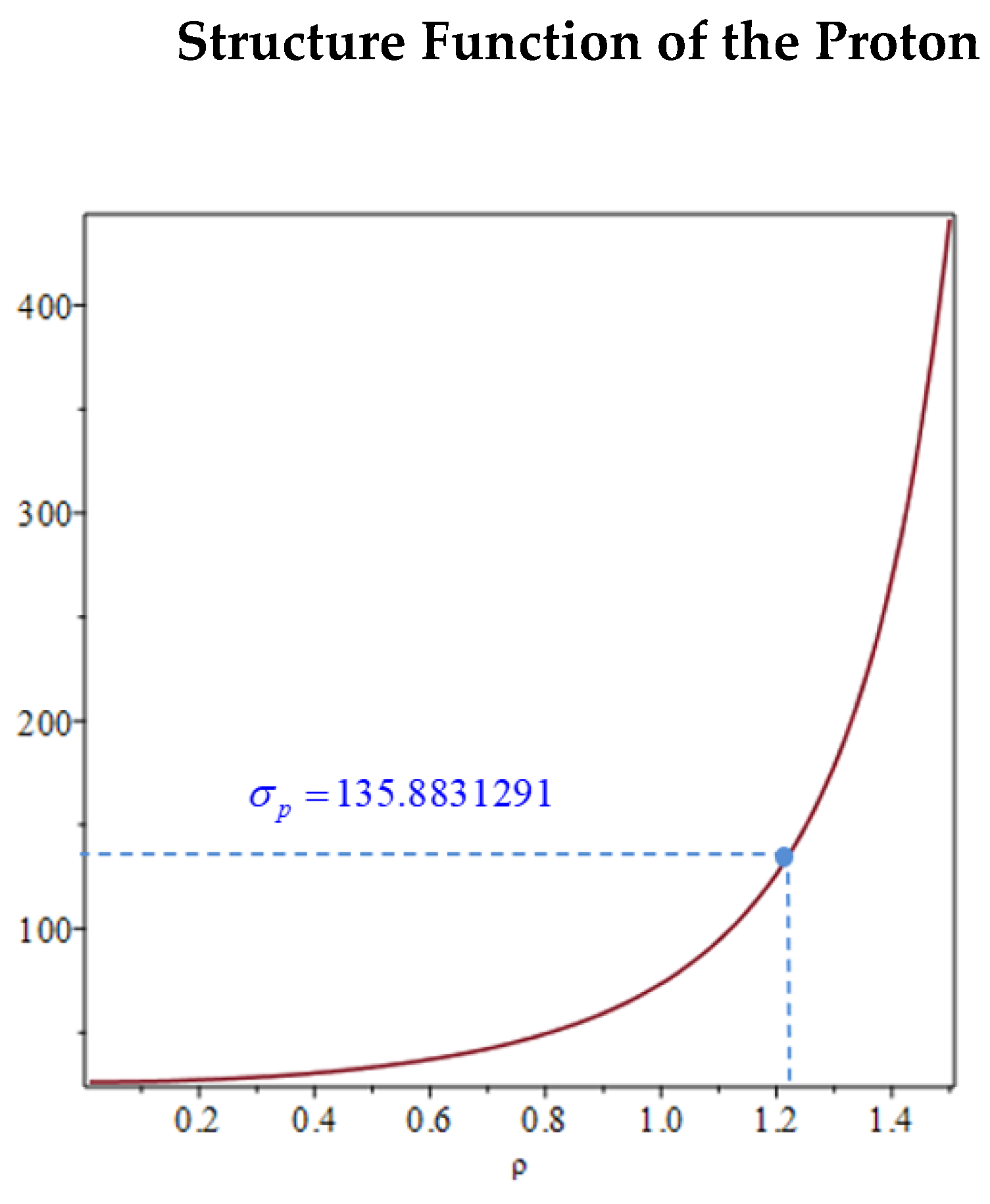

7. Application of Assembly Method to a Proton

For assembly of a proton, it is necessary to proceed as described in the previous chapter 8. Considering that quarks have beyond the pure rest mass energy also the energy exchanged through the gluons with the other two quarks of the proton. Its structure function must be calculated with an appropriate empirical value of the interaction ratio in such a way that the average interaction distance between the three quarks establishes a correct energy in order to have the expected proton mass.

Since it is not possible at this stage to define an independent way to estimate the value of the average distance of mutual interaction between the three quarks that form the proton, one will consider the experimental mass of the proton as a reference datum in order to obtain as the main result and consequent possible feedback of the model, the estimate of the average dipole moment per unit of charge and consequently the charge radius. In fact, considering that for particles not with cylindrical symmetry as in the case of the proton which is formed by three quarks, the mean dipole moment can be considered an estimate of the diameter of the proton, the resulting radius is of the order of the charge radius of the proton whose value has recently been updated with a new experimental measurement .

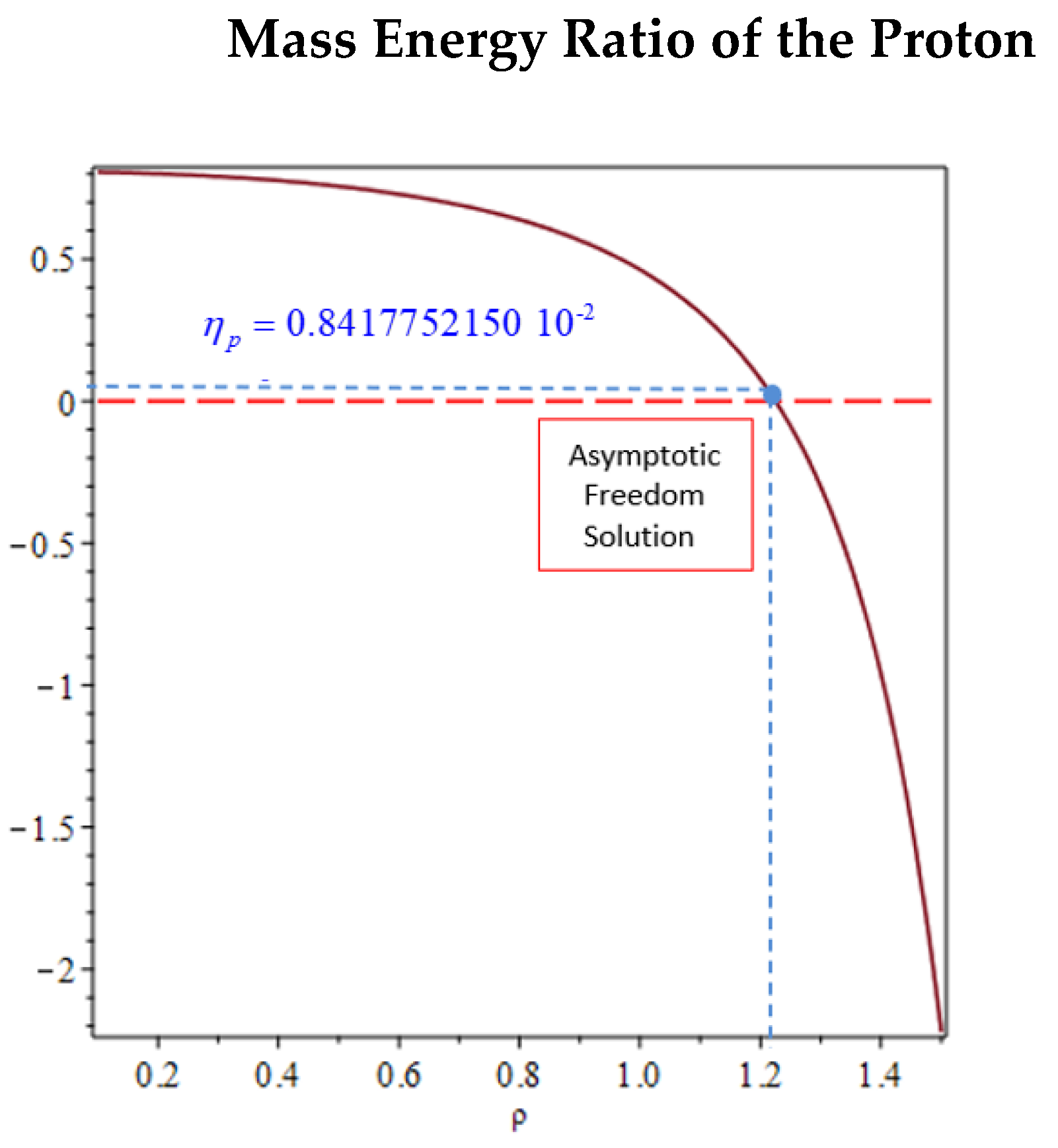

Considering that the three quarks

have a structure function based on their reciprocal interaction

which behaviour is shown in

Figure 7 as a function of the interaction distance ratio

that parameterize the mean dipole moment of the three sub-cells formed in the interaction between the three quarks, the rest masse energy ratio function obtained by using Equation (38) is

that for quarks that form a proton must have a rest mass energy ratio very close to zero, so that the rest mass energy of the proton it is essentially produced by the exchange of gluons. During the relative motion, the quarks remain confined within the structure of the proton, free to move with respect to each other by shifting the blue dot in

Figure 8 representing the energy fraction of the rest mass of the quarks relative to the rest mass of the proton on the left, i.e., reducing their average distance, increases the rest mass energy of the interacting quarks, without the total energy of the proton change. In this sense the model emulates the confinement of quarks. In fact, the goal within the numerical precision of eight digits is achieved for the value of the ratio in the blue point in

Figure 8:

this value is slightly less than the ratio corresponding to the zero value of the rest masses energy ratio

of the quarks.

Using the estimated rest mass energy of the quarks

and the mass energy ratio (39) of the proton estimated in the blue point

shown in

Figure 7, using Equation (34) the rest mass energy of the proton results to be

The proton displays an asymptotic freedom behaviour near a vanishing ratio. Under external collisions, this ratio decreases:

, the mass energy ratio grows, i.e. quarks become more massive by reducing the mutual exchange of gluons, becoming less bound but more difficult to eject from the proton structure. In the case shown the proton is formed and the mass energy ratio

between the rest mass energy of the component quarks and the final rest mass energy of the proton is the 0.8418%. The 99.1582% of the remaining energy of the proton is given by the exchange of energy between quarks, i.e., is given by the gluons exchanged. The red dashed line corresponds to zero of the energy fractions of the quark’s masses. corresponding to a proton with mass

in agreement with the measured rest mass value

MeV/c

2 (See. Ref. [

14]). In this case the average dipole moment per unit of charge can be calculated as

so the average charge radius results determined using the theoretical value of the Planck constant for free interaction as

with a value slightly lower than the most recent values obtained experimentally

fm (Cf. Ref. [

15]) and

fm (Cf. Ref. [

16]). Equation (41) provides in any case a confirmation of the consistency and correctness of the model used. In fact, it must be taken into account that the estimated value theoretically could be lower than those obtained experimentally because the quarks inside the proton interact freely with each other without external interactions, therefore they do not acquire external energy by excitation increasing the average diameter of the proton.

8. Application of Assembly Method to a Neutron

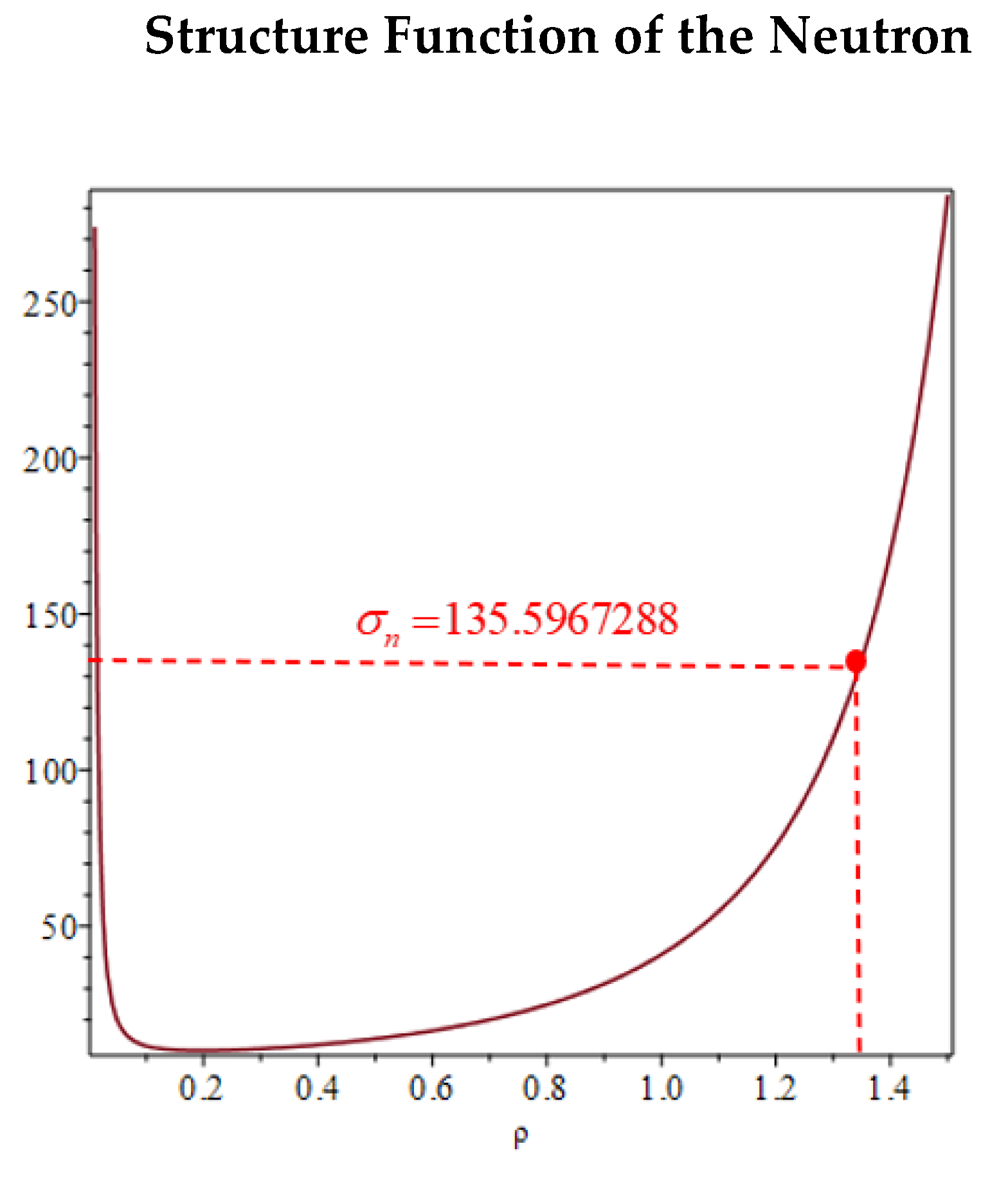

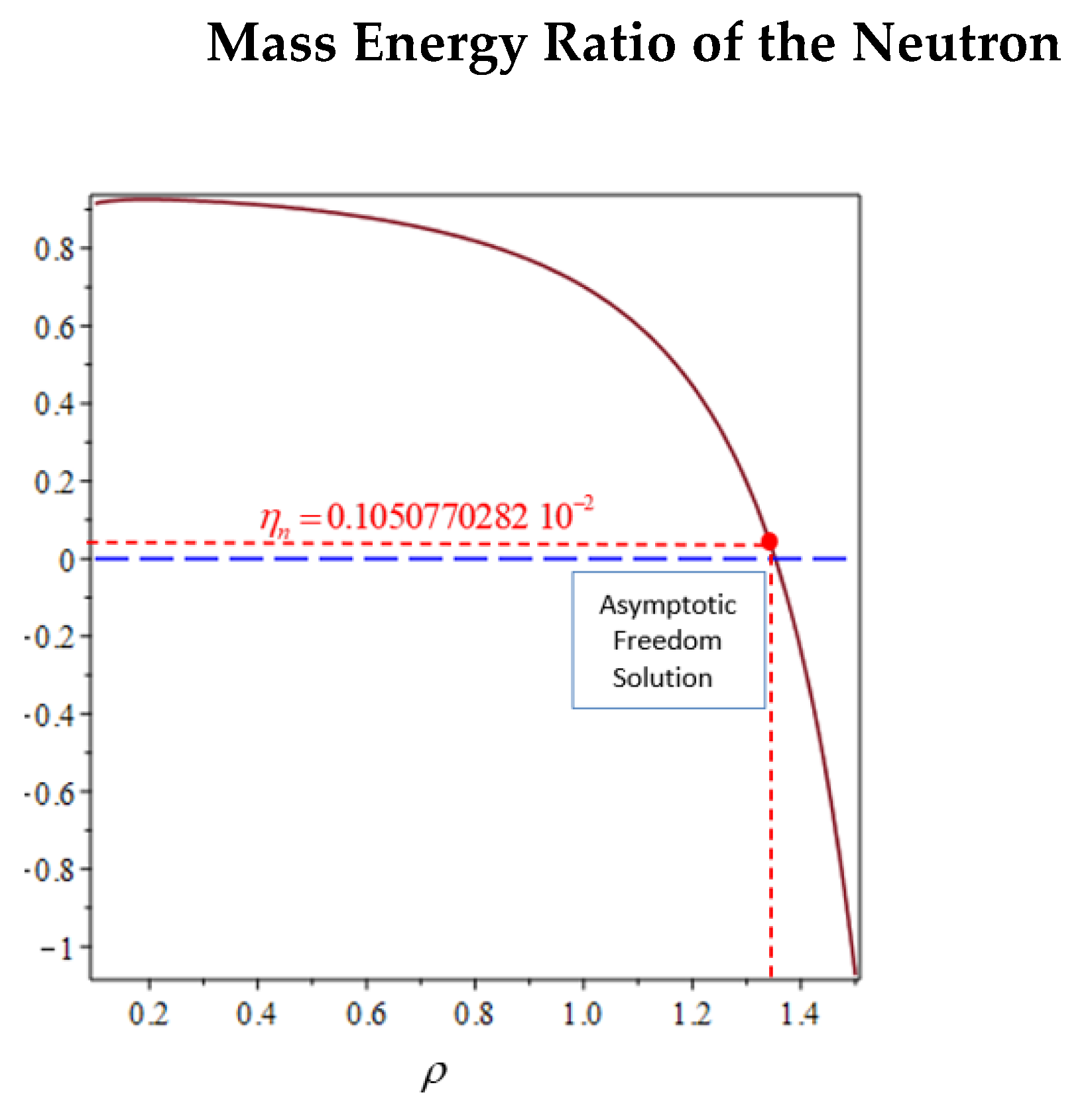

To build a neutron, one uses the same procedure used for the proton. Considering that the three quarks

have a structure function based on their reciprocal interaction

which behaviour is shown in

Figure 9 as a function of the ratio

that parameterize the mean dipole moment of the three sub-cells formed in the interaction between the three quarks, the rest mass energy ratio plotted in

Figure 10 as a function obtained by using Equation (42) is

which for the quarks that form a neutron must have a low-mass energy ratio, so that the three quarks remain bound and confined within the neutron structure but free to move relative to each other. Also in this case, as for the proton, the value obtained of the ratio

is slightly less than the ratio corresponding to the zero value of the mass energy ratio

.

Using the rest mass energy of the quarks

and the mass energy ratio (43) of the neutron shown in the red point

in

Figure 9, using Equation (34) the rest mass energy of the neutron results to be

corresponding to a neutron mass

in agreement with the measured rest mass value

MeV/c

2 (See. Ref. [

14]). In this case the estimated value of the radius of the neutron is equal to

The radius calculated within the present model refers to the average dipole moment per unit charge of the DEMS generated by quark interactions. It represents an intrinsic structural property derived from the internal electromagnetic dynamics of the hadron. This quantity cannot be directly compared with the neutron charge radius obtained from scattering experiments, which reflects an external probe response and leads to a negative mean square radius value. In the standard formalism, such a result yields no real linear size, whereas the present model provides a physically meaningful and real-valued estimate.

9. Discussion and Conclusions

In this work, a theoretical model based on the electromagnetic Bridge Theory (BT) has been developed to explain the mass-energy structure of the up and down quarks and their mutual interactions within hadronic systems. Unlike the standard approach based on the QCD framework, where the strong interaction is considered, a fundamental force mediated by massless gluons, the BT proposes an electromagnetic origin of the strong interaction, emerging from the dynamics of fractional charges and their associated Dipole Electromagnetic Sources (DEMS).

By introducing the concept of the Strong Exchange Quantum (SEQ), the model establishes a direct link between the energy exchanged in quark interactions and an electromagnetic mechanism governed by a variable coupling constant. This reinterpretation allows the derivation of the rest mass energies of the quarks u and d, obtaining values in excellent agreement with both experimental data and lattice QCD simulations, without the need for arbitrary mass assignments or renormalization prescriptions.

Furthermore, the model describes in detail the assembly mechanism of baryons as a function of the electromagnetic structure of the interacting quarks. Using an effective structure function and a parametrization of the dipole ratio , it is possible to reconstruct the mass, binding energy, and charge radius of hadrons such as the proton and neutron. The results obtained are highly consistent with experimental measurements, including the charge radii of nucleons and their mass-energy compositions.

A key feature emerging from the analysis is the confinement mechanism as a natural consequence of energy conservation within the DEMS. The variability of the dipole ratio ρ produces a redistribution of the rest mass and interaction energy between quarks, allowing them to remain bound within a composite particle while varying their relative positions. Gluon exchange emerges as a secondary electromagnetic effect, leading naturally to an effective condition of asymptotic freedom.

From a foundational perspective, the results suggest that the apparent complexity of strong interactions may be the macroscopic manifestation of a deeper electromagnetic process acting at quantum scales. The BT framework offers a coherent and predictive tool capable of bridging classical electromagnetism and quantum behaviour, proposing a radical but testable alternative to conventional gauge theories.

In conclusion, the Bridge Theory not only provides a quantitative estimation of quark masses and hadronic structures but also outlines a unifying scenario in which all fundamental interactions may be derived from electromagnetic principles. The theoretical consistency, numerical accuracy, and conceptual simplicity of the model highlight its potential as a new paradigm in the understanding of fundamental physics.

Future work will aim to extend the model to include higher-generation quarks and explore implications for meson structures and decay processes.

References

- Gell-Mann, M. The symmetry group of vector and axial vector currents. Physics Physique Fizika 1964, 1, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweig, G. , An SU(3) Model for Strong Interaction Symmetry and Its Breaking Version 2. CERN-TH-412, NP-14146, PRINT-64-170 1964, 22-101. [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M. The Eightfold Way: A Theory of strong interaction symmetry. CTSL-20, TID-12608 1961. [CrossRef]

- Lobanov, A.E. Neutrino–antineutrino pair production by a photon in a dense matter. Physics Letters B 2006, 637, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Auci. “A conjecture on the physical meaning of the transversal component of the Poynting vector. II. Bounds of a source zone and formal equivalence between the local energy and the photon.” Physics. Letters A 1990, 148, 399. [CrossRef]

- M. Auci. “A conjecture on the physical meaning of the transversal component of the Poynting vector. III. Conjecture, proof and physical nature of the fine structure constant”. Physics Letters A 1990, 150, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Auci. “A conjecture on the physical meaning of the transversal component of the pointing vector”. Physics Letters A 1989, 135, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auci, M.; Dematteis, G. An approach to unifying classical and quantum Electrodynamics. Int. Journal of Modern Phys. B 1999, 13, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Auci. “Estimation of an absolute theoretical value of the Sommerfeld’s fine structure constant in the electron–proton capture process”. Eur. Phys. J. D 2021, 75, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Auci. “On a Non-Standard Atomic Model Developed in the Context of Bridge Electromagnetic Theory”. J. of Phys. - Chem. & Biophysics 2024, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Auci. “ Estimation of the Coupling Constants for the Strong Interaction in the Framework of the Electromagnetic Bridge Theory” Preprint.org. [CrossRef]

- Auci, M. Superluminality and Entanglement in an Electromagnetic Quantum-Relativistic Theory. Journal of Modern Physics 2018, 9, 2206–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Auci. “Relativistic Doppler Effect and Wave-Particle Duality”. SSRG International Journal of Applied Physics 2020, 7, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Navas et Al. (Particle Data Group Collaboration). “Review of Particle Physics”. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 030001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, A.; et al. “The Rydberg constant and proton size from atomic hydrogen”. Science Vol. 358, Issue 6359. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W. , Gasparian, A., Gao, H. et al. A small proton charge radius from an electron–proton scattering experiment. Nature 2019, 575, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).