1. Introduction

"Vulnerability of ecosystems and people to climate change differs substantially among and within regions, driven by patterns of intersecting socioeconomic development, unsustainable ocean and land use, inequity, marginalisation, historical and ongoing patterns of inequity such as colonialism, and governance"

(IPCC, 2022).

This quote marks the first mention by a scientific body such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of colonialism as both a historical and ongoing driver of injustice, highlighting how colonial legacies continue to influence current environmental, social, and economic vulnerabilities. These legacies are especially pronounced in the global South, where the exploitation of land, resources, and people under colonial rule has left profound structural inequalities that persist today.

These historical injustices are not merely relics of the past; they are perpetuated and even exacerbated by contemporary climate governance mechanisms. Within the global framework of climate negotiations, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has emerged as a central arena where states negotiate the terms of climate action, with input from corporations and civil society. According to Dehm (2016), the UNFCCC's primary objective, to stabilise greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that prevents dangerous anthropocentric interference with the climate system, also reflects the tension between ecological limits and the imperatives of economic growth.

The UNFCCC's focus on sustainable development aligns with neoliberal principles that drive the global carbon market and endangers Indigenous livelihoods, raising alarm on "carbon colonialism." This term describes how carbon trading and offset schemes replicate colonial exploitation by commodifying natural resources and shifting the burden of mitigation to the Global South (Bumpus and Liverman, 2010). Mechanisms like those under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement allow industrialised countries and corporations to continue polluting by buying carbon credits from projects in less developed regions, often without regard for Indigenous Peoples' (IPs) rights or their traditional land management practices.

Therefore, carbon market mechanisms, such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), have been criticised for perpetuating extractivist practices over sustainable, locally-led alternatives, often resulting in increased emissions and adverse effects on Indigenous lands and livelihoods (Indigenous Climate Action, 2019; Boyd et al. 2009). In this mechanism, IPs, who often act as stewards of vast biodiverse territories, are disproportionately impacted by these market-based mechanisms, which have been documented to cause dispossession, cultural erasure, and environmental degradation (Cadman and Hales, 2022). In this context, this research will examine the development of carbon market mechanisms under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, focusing on the power dynamics between IPs and dominant actors such as states and corporations in carbon market negotiations. The research questions are: (1) How have Indigenous Peoples contested the mechanisms under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which they argue perpetuate carbon colonialism, during the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) negotiations (COP25 and COP26)? (2) What insights do these contestations offer into the power dynamics and socio-environmental conflicts inherent in global climate governance?

To address them, this paper will be organised into several key sections. Following the introduction, the literature review will explore power dynamics in global climate governance, carbon market structures, and carbon colonialism and Indigenous Peoples. While the methodology will detail the research approach, the conceptual framework will employ Political Ecology to analyse power dynamics (instrumental, structural, and discursive) affecting Indigenous participation. The analysis will examine historical developments and specific COP negotiations (COP25 and COP26) in relation to Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. It will end with discussion and conclusion sections.

2. The Carbonisation of Governance, Markets and Neo-Colonialism

2.1. Neoliberal, Market-Driven Climate Governance

Global climate change governance has, from its inception, been firmly embedded in a neoliberal paradigm. Emissions trading was already being brought into the negotiations of the UNFCCC treaty text as early as 1991 through the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and its new GHG trading department (Bachram, 2004). The 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, where the UNFCCC was opened for signature, was also marked by a strong neoliberal sentiment evidenced by its endorsement of an “open economic system” and continuous economic growth (Bachram, 2004). The chair of the Rio Summit, then-UN Secretary-General Maurice Strong, is known to have had strong personal ties with the corporate sector (CJA and IEN, 2017).

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol introduced market-based instruments to carbon mitigation efforts. The U.S. had successfully pushed for the inclusion of "flexible mechanisms" as a non-negotiable condition for accepting binding targets (Stowell, 2005; Schroeder, 2001). Other parties eventually conceded to these demands for flexibility in return for continued support from the world’s largest emitter (CJA and IEN, 2017). This instrumental power was used to navigate the negotiations towards market-based solutions, emphasising economic over regulatory approaches (CJA and IEN, 2017).

Following the Kyoto Protocol, significant developments in carbon markets ensued. In June 1999, the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) was set up by UNCTAD (Bachram, 2004) with a coalition of international companies and business associations. IETA was the first multi-sectoral business group to focus on trading GHG reductions (IETA, n.d.) and this illustrates how powerful business interests can shape market mechanisms. The association significantly shaped the carbon market to prioritise financial profits and speculative opportunities, often undermining environmental integrity in the process (Lohmann, 2012). It wielded instrumental power by using its influence to shape market rules and practices for the benefit of its members.

The 2015 Paris Agreement requires all Parties to submit Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), reflecting voluntary, country-specific climate goals and measures (UNFCCC, 2015) and shifting the focus from historical emissions to a more universal responsibility for climate action and a more inclusive approach (Mills-Novoa and Liverman, 2019). It lacks strict enforcement but uses a transparency framework to encourage accountability and ambition over time. Article 6 is a critical element, as it provides the foundation for voluntary international cooperation in achieving climate goals. Article 6 includes frameworks for cooperative approaches and sustainable development mechanisms. While often referred to as the "market article," Article 6 allows countries to transfer mitigation outcomes to meet their NDCs elsewhere. Instead of mentioning “markets” (Cadman and Hales, 2022), the article introduces the concept of “Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes” (ITMOs), giving countries flexibility to set up carbon markets if they choose.

Since COP24 in Katowice, where most of the Paris Agreement rulebook was adopted but decisions on Article 6 were postponed due to persistent disagreements, negotiations on carbon market mechanisms have been a central yet contentious agenda item. COP25 in Madrid failed to deliver consensus, particularly on issues such as double counting, transition of Kyoto-era credits, and the integration of human rights protections (Evans and Gabbatiss, 2019; Newell and Taylor, 2022; CIEL, 2020). COP26 in Glasgow marked a turning point with the adoption of the Article 6 rulebook, establishing frameworks for market-based cooperation (6.2 and 6.4) and non-market approaches (6.8), though civil society criticized the weak language on human rights and environmental safeguards (Masood and Tollefson, 2021; Minas, 2022; Cadman and Hales, 2022). COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh focused on operationalizing these mechanisms, launching a capacity-building work programme, but made little progress on unresolved technical issues (UNFCCC, 2022; Asadnabizadeh, 2024). At COP28 in Dubai, negotiations stalled amid closed-door "informal informal" meetings and growing concerns over transparency and undue pressure from financial institutions, ultimately failing to reach consensus on implementation details for Articles 6.2 and 6.4—though the Article 6.8 work programme was adopted (Gilbertson and Goldtooth, 2023). Finally, COP29 in Baku in late 2024 delivered the long-awaited conclusion of the Article 6 negotiations, adopting comprehensive guidance on accounting, registries, and methodological standards, including an international registry linked to both centralized and national systems (Arora, 2025; Caneill and Cassen, 2025).

2.2. Carbon Markets

The commodification of carbon involves converting carbon emissions into tradable units, effectively treating pollution as a marketable commodity (Descheneau, 2012) and highlighting privatisation, individuation, and valuation as key aspects of commodification (Castree, 2003). Privatisation assigns exclusive rights to resources, individuation involves isolating commodities from their contexts for sale, and valuation focuses on exchange value, often neglecting social and ecological worth. Additionally, to be profitable, commodities are often modified to meet the demands of capital— namely the logic of capital accumulation, which prioritizes short-term profitability, return on investment, and the expansion of market value over social or ecological concerns. Pollution trading advocates believe it is cost-effective, fosters innovation, and consistently reduces pollution through market incentives, unlike technology-based regulations, which they view as economically inefficient and overly rigid (Drury et al., 1999). Polanyi (1944), on the other hand, warns that relying solely on market mechanisms can lead to social and ecological destruction, as nature managed purely by market values may undermine societal and environmental well-being. Thus, the creation of carbon commodities reflects a complex interplay between global carbon markets and local socio-environmental conditions, highlighting the challenges of global environmental governance (Bumpus, 2011).

Carbon markets are designed to standardise the creation, trading, and regulation of carbon credits through mechanisms such as emissions reduction crediting, baseline establishment, emission caps, and trading systems (Cadman and Hales, 2022). Carbon credits, represented as certificates or permits, are generated by projects that either reduce or avoid GHG emissions, measured in tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) (Bumpus, 2011). This market-based approach aims to incentivize sustainable practices and make climate mitigation cost-effective by integrating carbon trading into capitalist frameworks, thereby creating new economic opportunities and minimising state intervention, in alignment with neoliberal economic principles (Ciplet et al., 2015; Lohmann, 2012).

However, critics like Pearse and Böhm (2014) argue that carbon markets are fundamentally flawed and irreformable. They highlight failures in the system, unjust practices, loopholes for polluters, and difficulties in verifying offsets. Additionally, they point out the unrealistic equivalence between carbon sequestration and fossil fuel emissions, and how the reliance on pricing can undermine more effective decarbonization strategies, such as reducing deforestation and restoring soil health. The international carbon market’s utilitarian approach thus focuses on an imagined collective good rather than addressing systemic sustainability challenges (Dehm, 2016).

The Kyoto Protocol marked the introduction of market-based mechanisms to reduce GHGs. It established a cap-and-trade system where countries received emissions credits based on their 1990 levels, which could be traded, banked, or used to offset excess emissions (Bachram, 2004). These credits, measured in tCO2e, transformed emissions into tradable commodities. It also introduced two project-based mechanisms: CDM and Joint Implementation (JI). The CDM was designed to assist developing countries in achieving sustainable development outcomes while enabling industrialised countries to meet their reduction targets through investing in the developed country. JI allowed industrialised countries to earn emission reduction units by undertaking projects in other industrialised countries (Yamin and Depledge, 2004). However, these mechanisms have been critiqued for perpetuating inequities by allowing developed countries to cheaply offload their emission reduction responsibilities onto poorer countries (Hickel 2020; Dehm, 2016).

The Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015, expands on the Kyoto mechanisms by introducing new international trading mechanisms under Article 6 through cooperative approaches (Article 6.2), a new market mechanism (Article 6.4), and non-market approaches (Article 6.8) (UNFCC, 2015). Article 6.2 allows for voluntary cooperation between countries to transfer carbon credits, enhancing global emissions trading, while Article 6.4 establishes a new mechanism to contribute to greenhouse gas mitigation, replacing the CDM with a focus on environmental integrity and sustainable development. Article 6.8 emphasizes non-market approaches, including technology development, transfer, and capacity-building, to support broader climate goals. While Article 6 aims to create a more integrated and flexible carbon market, it has been subject to debate. Critics argue that it still perpetuates the reliance on offsets that may not deliver real or additional emission reductions (Dehm, 2016). Furthermore, the use of carbon markets to achieve global climate targets is challenged by difficulties in verifying the effectiveness of offset projects and concerns about exacerbating global inequalities (Pearse and Böhm, 2014).

2.3. Carbon Colonialism and Indigenous Peoples

Although formal, direct colonial control has ended, some countries continue to wield power over other countries or peoples through guised means. This phenomenon, known as "neo-colonialism" involves maintaining dominance through economic and legal frameworks, thereby sustaining political control indirectly. Local elites often align with the international capitalist agenda, either voluntarily or by incentive or coercion (Nkrumah, 1966; Perkins, 2023).

Carbon colonialism refers to developed countries, which have historically contributed the most to ecological degradation generally, and climate change through intensive resource extraction and consumption specifically, now imposing restrictive climate policies on developing countries (Bumpus and Liverman, 2010). This dynamic stifles developing countries in their developmental trajectory through resource exploitation and production for global markets (Dehm, 2016), thus exacerbating both environmental and economic inequalities and enabling richer countries to sustain their highly ecologically destructive practices while outsourcing the environmental costs to poorer countries (Bumpus and Liverman, 2008; Böhm and Dabhi, 2009).

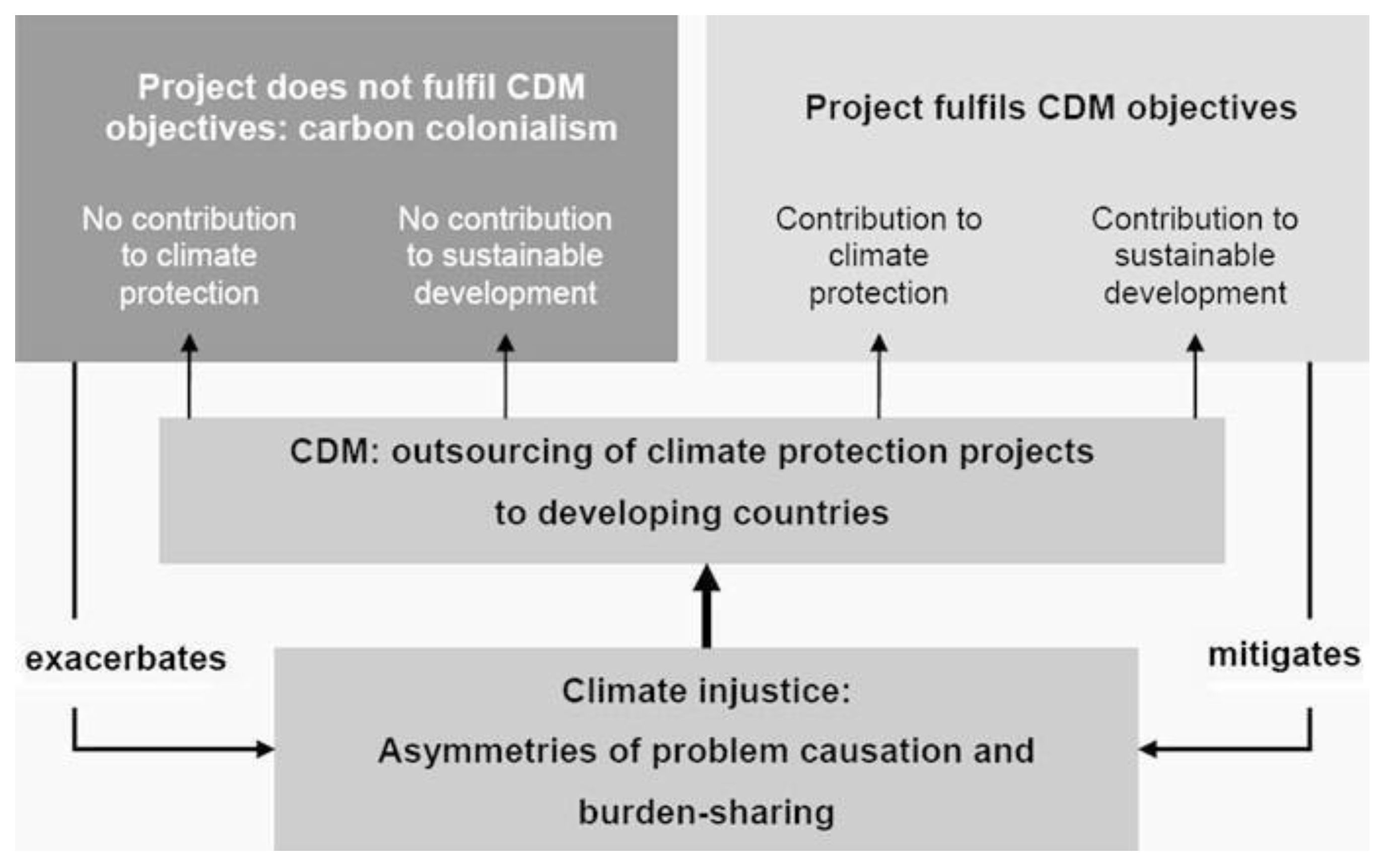

The Kyoto mechanisms have enabled neo-colonial practices (

Figure 1) by giving carbon credits to “managed” carbon sinks like state-run or corporate monoculture plantations, while forests managed by Indigenous communities have found it difficult to receive CDM accreditation given technical and bureaucratic barriers, a structural bias toward large-scale projects, and lack of secure land tenure, among others (Jung 2005; Bachram 2004). This system disregards traditional land stewards and opens the door for land grabs by powerful interests. Furthermore, the way credits are allocated—based on historical emissions—has benefited major polluters.

Carbon markets often amount to "greenwashing," masking the ongoing exploitation of resources for private profit while deepening social and environmental inequities (Bakker, 2015). Carbon offset projects, promoted as climate solutions, have often violated human rights when local communities and ecosystems were disregarded, and led to issues like food insecurity, resource depletion, and land grabs (Adelman, 2017). They not only perpetuate existing injustices but also introduce new forms of exploitation under the guise of environmental responsibility (Obergassel et al., 2017).

Indigenous Peoples are particularly vulnerable to carbon colonialism given their very different worldviews and values. While there is not an authoritative definition of who is Indigenous, self-determination as Indigenous and defining their own identity or membership based on their customs and traditions is a key criterion (United Nations, 2007). The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples emphasises that Indigenous communities have a strong connection to their territories and natural resources, maintain distinct social, economic, and political systems, and preserve unique languages, cultures, and beliefs (UN, n.d.). Although they make up only around 5% of the global population, IPs steward 20-25% of the world's land, which harbours 80% of global biodiversity and encompasses 40% of all protected and ecologically intact areas (Masaquiza Jerez, 2021). This land represents over 300 gigatons of carbon sinks (Indigenous Climate Action, n.d.). Since the early 2000s, Indigenous groups have actively sought recognition and a formal role in UNFCCC negotiations. Their advocacy was crucial in highlighting the shortcomings of mechanisms like CDM or REDD+, which they argued could lead to new forms of colonialism by expropriating their lands and undermining their traditional rights, and allowing industrialised countries to offset their emissions at the expense of Indigenous lands and livelihoods in the Global South (Dehm, 2016).

In 2001, the UNFCCC officially recognized IPs as one of nine major groups, and this recognition provided a structured way for Indigenous representatives to engage in the UNFCCC process (Lakhani, 2021; Carmona et al., 2023). In 2008, IPs established the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change (IIPFCC), or Indigenous Peoples' Caucus, to coordinate their positions, statements, and advocacy efforts during UNFCCC meetings and beyond. Their advocacy led to the creation of The Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP) at COP21 in Paris (Decision 1/CP.21, paragraph 135), aimed at enhancing the engagement of IPs and local communities in climate negotiations and ensuring their unique knowledge and perspectives are included in decision-making processes (Decision 2/CP.23) (Carmona et al., 2023). Organisations such as the Indigenous Environmental Network, Climate Justice Alliance, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs and Forest Peoples Programme play critical roles in these processes by articulating and amplifying the perspectives and arguments of IPs (see

Appendix A).

3. Methodology

This research examines the power dynamics and socio-economic conflicts within global climate governance, particularly through an analysis of the UNFCCC negotiations at COP25 and COP26. The UNFCCC and its COP meetings are the central forums where global climate policies are negotiated and shaped by diverse stakeholders and where a crucial space is provided for engagement and direct interaction among stakeholders. COP25 and COP26 were chosen due to their role in shaping the global carbon market framework, especially in relation to the development and finalisation of the rulebook, including Article 6, of the Paris Agreement. These COPs are selected as case studies for the distinct opportunities they present to observe stakeholder interactions during the finalisation of Article 6, rather than to serve as representative examples of all climate negotiations.

Building on this focus, the research adopts a qualitative case study approach to analyse the interactions and power dynamics present during the COP25 and COP26 negotiations. This approach is particularly effective as it can “benefit from exploring, unpacking, and describing social meanings and perceptions of a phenomenon, or a program” (Skovdal and Cornish, 2015, p. 5). It is well-suited to understanding the complex socio-economic dynamics at play during the COP25 and COP26 negotiations, where multiple actors with differing levels of power and influence interact to shape global climate policy.

The study relies on secondary data analysis, which involves an extensive review of relevant documentation, including official UNFCCC negotiation texts, decision drafts, reports, publications from Indigenous organisations and NGOs, newspaper articles and academic literature. As highlighted by Yin (2009), a systematic search for and analysis of such documentation is crucial for providing a comprehensive understanding of the case study. Although a formal systematic review protocol was not strictly followed, efforts were made to conduct a comprehensive and organized search process. Key documents and academic sources were identified through targeted keyword searches across multiple databases, and materials were systematically categorized according to emerging themes related to global climate governance, carbon markets, Indigenous participation, and power dynamics. Relevant UNFCCC documents were downloaded and organized into folders corresponding to thematic chapters of the study, facilitating detailed coding and analysis. This approach enabled a thorough exploration and synthesis of the secondary data to generate new insights on the complex interactions at play in climate negotiations. The selected material is assessed following best practices for evaluating secondary data to bring forth new interpretations, insights, and conclusions about the power dynamics and conflicts within these negotiations (David and Sutton, 2004).

To analyse the collected data, the study employs a Political Ecology framework, which allows for a critical exploration of the intersection between environmental issues and power structures, including political, economic, and social dimensions. This framework is particularly suited to unpacking how global climate governance mechanisms, such as carbon markets, may reinforce existing inequalities and how these dynamics are contested by marginalised groups like IPs. By employing this analytical lens, the research explores the roles of instrumental, structural, and discursive power in shaping climate policy outcomes and stakeholder interactions at COP25 and COP26.

The study employs a triangulation strategy to enhance the reliability of its findings. By cross- referencing information from different sources, as recommended by Carter et al. (2014), this approach provides a more detailed understanding of the complexities in UNFCCC negotiations and ensures that the conclusions are well-supported and credible.

4. Political Ecology Framework

A political ecology approach that engages with the literatures of the commodification and neoliberalization of nature, and that seriously considers political economy, the materiality of resources, and power relations, is crucial for developing a comprehensive understanding of global climate governance (Osborne, 2015). By examining how environmental issues intersect with political, economic, and social power (Wisner, 2015), Political Ecology enables a critical assessment of how global climate governance reinforces existing inequalities and exposes broader power dynamics. This framework provides a powerful lens through which to analyse the environmental, social, and political dimensions of climate governance, especially in the context of Indigenous contestations at COP negotiations. It highlights how power relations shape environmental policies, such as those under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, often to the disadvantage of marginalised communities, including IPs (Bryant and Bailey, 1997).

Power, as defined by Weber (1978, p. 53), is “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance, regardless of the basis on which this probability rests.” This understanding of power as a relational force is central to Political Ecology, where power dynamics are analysed not just in terms of direct control but also through more subtle, systemic, and discursive means. To examine the complex power relations at play in COP negotiations, particularly concerning Indigenous contestations of Article 6 mechanisms, this analysis will focus on the multidimensional concept of power outlined by Never (2013). Never’s framework categorises power into three distinct but interrelated forms: instrumental, structural, and discursive power.

Instrumental Power refers to the capacity of an actor to directly influence or coerce others to achieve specific outcomes. In climate negotiations, this power is often used by influential entities that can set agendas, make decisions, and enforce policies. The Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition (CPLC) serves as a notable example of instrumental power in action. Launched at the Paris Climate Conference (COP21) in 2015, the CPLC is a voluntary initiative aimed at advancing carbon pricing globally (CPLC, n.d.). The Coalition brings together a broad array of stakeholders, including national and sub-national governments, major corporations like Shell and HSBC, and NGOs and academic institutions. The World Bank Group administers the CPLC Secretariat, underscoring the initiative’s global institutional backing. The CPLC exerts instrumental power by mobilising influential leaders and organisations to advocate for and implement carbon pricing mechanisms. By uniting high-profile participants, such as the U.S. and UK governments and major firms like Nestlé and BP, the CPLC helps to shape global climate policy (CPLC, n.d.). This coordination emphasises carbon pricing as a key strategy for mitigating climate change, aligning with broader goals of economic efficiency and market-based solutions. According to Wettestad et al. (2021), the CPLC’s role in the international carbon market web highlights how such initiatives can dominate policy discussions and implementation processes. By leveraging its connections and resources, the CPLC helps maintain carbon pricing at the forefront of climate policy debates. Thus, the CPLC’s use of instrumental power illustrates how dominant actors can shape climate policy.

Structural power involves shaping the context, rules, and institutions in ways that align with an actor’s interests, often indirectly influencing others by determining the framework within which decisions are made. In the context of COP negotiations, structural power is instrumentalized by those who design and control the institutional processes—primarily the UNFCCC Secretariat, the COP Presidencies, and Parties themselves—who collectively shape agendas, procedures, and access. IPs, despite their increasing recognition through mechanisms like the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP), often find themselves at a disadvantage due to the state-centric nature of the negotiations and the procedural norms that privilege state actors (Belfer et al., 2019; Schroeder et al. 2025). Falzon (2023) further illustrates this dynamic by revealing how financial constraints on developing countries and Indigenous groups impact their participation. Despite efforts by the UNFCCC to promote inclusivity, they face budget limitations that restrict the size and influence of their delegations. This financial disparity reinforces existing power imbalances, making it difficult for Indigenous participants to exert meaningful influence. Additionally, the non-state observer status of Indigenous groups means their involvement relies heavily on the goodwill of state actors, who control which issues are discussed and which voices are heard.

Discursive power, as described by Never (2013), pertains to the ability to shape the identity, perceptions, and preferences of other actors through the control of discourse. In the context of climate governance, discursive power is exercised through the framing of climate issues, the narratives that are legitimised, and the language used in negotiations. For IPs, the ability to assert their perspectives and worldviews within the COP negotiations is a critical form of resistance against dominant discourses that often marginalised or misrepresent their interests (Belfer et al., 2019). Wallbott (2014) highlights how IPs, acting as norm entrepreneurs, have strategically leveraged their knowledge resources and normative power to influence the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) negotiations by integrating Indigenous Peoples' Rights language into the Cancun Agreements. This strategy of "importing power" into the UNFCCC demonstrates the effective use of discursive power, where Indigenous actors reframed REDD+ from a technocratic issue to one centred on normative concerns and do-no-harm considerations (McDermott et al. 2012). However, these discursive interventions are often constrained by the broader structural inequalities embedded within the COP process.

In examining the power dynamics at COP25 and COP26, the concept of carbon colonialism provides a critical lens for understanding how instrumental, structural, and discursive power operate to marginalise IPs and states in the Global South. Industrialised countries wield instrumental power to promote carbon market mechanisms that prioritise economic efficiency over social justice, often at the expense of Indigenous rights. Structural power is evident in the design and control of COP processes, which systematically sidelines non-state actors like IPs. Discursively, Indigenous groups have sought to reshape dominant narratives, challenging market-based solutions as a continuation of colonial exploitation that overlook their rights and well-being. By framing these power dynamics through carbon colonialism, this analysis highlights the perpetuation of historical inequalities in climate policies and underscores the need for equitable and rights-based approaches in international climate negotiations.

Table 1.

Three-Dimensional Power in COP Negotiations.

Table 1.

Three-Dimensional Power in COP Negotiations.

| Three-Dimensional Power in COP Negotiations |

| |

Instrumental |

Structural |

Discursive |

| |

Instrumental power refers to the direct use of influence, whether through lobbying, agenda-setting, negotiation tactics, or financial leverage, to produce concrete outcomes in climate negotiations. This power is most visible when actors shape decisions, steer agenda items, or secure specific language in treaties.

|

Structural power operates through the design and control of rules, contexts, and systems, often indirectly. It reflects an actor’s embedded position in material, technological, or institutional systems, allowing them to shape the conditions under which others operate, even without direct intervention.

|

Discursive power is the ability to shape norms, language, and perceptions—to influence how issues are framed, which narratives are legitimized, and whose voices are amplified. It often involves non-material influence, such as appealing to ethics, justice, or tradition.

|

| Actors |

States (especially those politically and/or financially strong), negotiators, donor countries, and the private sector. |

UNFCCC bodies, COP Presidencies, powerful and/or resource-rich countries, techno-scientific experts, global green finance institutions. |

Morally positioned states (e.g., LDCs, SIDS), Indigenous Peoples, NGOs, norm entrepreneurs, justice-oriented activists, social and mainstream media influencers. |

| Tools |

Agenda setting;

negotiation leverage; financial pressure or incentives; direct lobbying |

Institutional design;

rule-setting;

technological dominance;

market control;

possession of resources;

funding systems |

Norm promotion (e.g., justice);

strategic framing;

public narratives;

moral discourse |

| Effects |

- Shapes negotiation outcomes

- Promotes actor’s specific interests

- Drives adoption of policies |

- Defines the ‘rules of the game’

- Creates long-term systemic advantages

- Limits others' influence |

- Shifts how issues are understood

- Gains legitimacy and moral authority

- Introduces new norms |

5. Analysis

5.1. Indigenous Participation and Contestation of Carbon Markets Before COP25

While the UNFCCC's recognition of IPs as a constituency in 2001 and the establishment of the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change in 2008 led to the creation of the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP) at COP21 (Shawoo and Thornton 2019), significant structural challenges remain. The platform is made up of an equal share of party and Indigenous representation, thus constituting joint leadership and a new form of deliberation in the UNFCCC process (Haverkamp, 2025). Despite this innovation, the state-centric and top-down nature of the climate regime continues to sideline IPs through state actors wielding structural power and thus controlling the institutional framework of the ongoing negotiations. Although non-state actors can obtain 'observer status,' their role in the negotiation process remains limited (Schroeder, 2010). For instance, Indigenous leaders at UNFCCC events, accredited as non-state observers, have limited decision-making influence and are treated like NGOs and other ‘major groups’, with no formal mandate in the negotiations themselves, unless they are part of a country delegation (Laing, 2023).

This marginalisation was particularly evident in the context of REDD+, a topic of grave concern to Indigenous Peoples given their livelihoods depend on forests and forest resources, which they in turn protect (Suiseeya, 2017). This was now being threatened by proposed policy to protect and conserve forests from above. The Clean Development Mechanism was a recent example of where Indigenous Peoples were evicted from their ancestral lands in the name of climate policy (Boyd et al. 2009). Both can be seen as examples of green colonialism or carbon colonialism, where the rights of local and Indigenous peoples are constrained in order to conserve lands that are already in the hands of guardians of the land (Frandy, 2018). Structural power was thus evident in the exclusion of Indigenous voices from critical policy discussions. At COP13 in Bali (2007), Indigenous representatives protested their exclusion by wearing gags with ‘UNFCCC’ written on them, highlighting their lack of voice in critical discussions (Dombrowski, 2010). The frustration continued at COP14 in Poznan (2008), where the rallying cry “No rights, no REDD!” underscored their ongoing struggle for recognition and inclusion in REDD+ policies (Wallbott, 2014). These acts of protest were efforts to gain instrumental power by directly challenging their exclusion and demanding a role in decision-making processes.

To address their marginalisation and counteract the lack of both instrumental and structural power, IPs reframed their involvement in REDD+ negotiations as a normative issue, leveraging advocacy and knowledge sharing to assert their rights. This shift represents a strategic use of discursive power to reshape the terms of the debate. NGOs like Indigenous Peoples' Rights International and the Forest Peoples Programme were instrumental in defending Indigenous rights, such as free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), and ensuring their inclusion in decision-making processes (Dombrowski, 2010). Bolivia’s Indigenous president, Evo Morales, also played a crucial role by bringing Indigenous issues to the forefront at the 2010 World’s Peoples Conference on Climate Change in Cochabamba, rallying over 35,000 delegates to advocate for the rights of Mother Earth and the legal recognition of Indigenous land claims (Wallbott, 2014). This activism helped shift the focus of REDD+ discussions towards Indigenous rights, a successful example of wielding discursive power to alter the dominant narratives and policies, despite ongoing challenges. Although the REDD+ design process has yet to fully address Indigenous marginalisation, the increased visibility and influence of Indigenous advocacy have led to a growing acknowledgment of their role in climate policy, as reflected in subsequent UNFCCC drafts and submissions (Schroeder, 2010; Marion Suiseeya and Zanotti 2019).

Despite the efforts of IPs, their marginalisation in the UNFCCC process persisted, underlining the entrenched structural power dynamics. For instance, Comberti et al. (2016) highlight that at COP21 in Paris, the fragmented layout and restricted access areas further limited Indigenous participation. The "Green Zone," which actively showcased Indigenous representation through the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change, was both physically and strategically isolated from the main negotiation spaces, thereby excluding Indigenous voices from critical decision-making processes. This spatial and procedural separation exemplifies how structural power is used to limit the influence of non-state actors, reinforcing the exclusion of IPs from decision-making processes that shape global climate policy.

5.2. COP25 in Madrid in 2019

COP25 in late 2019, initially set to take place in Brazil, faced a series of venue changes due to shifting political landscapes. In late 2018, newly elected President Jair Bolsonaro withdrew Brazil’s offer, citing a government transition and financial constraints (Watts, 2018). The summit was subsequently relocated to Chile. However, escalating civil unrest in Chile necessitated another last-minute relocation, just one month before the conference, this time to Madrid, Spain (Lobos Alva, 2019). Despite the move, the Chilean government continued to preside over the summit. These frequent changes created significant logistical challenges, particularly for delegates from the Global South, Indigenous communities, and civil society groups, who faced increased costs and visa and travel complexities (Grosse and Mark, 2020). This instability highlighted the broader issues of inclusivity and access that have long affected international climate negotiations.

The main agenda of COP25 was to finalise the remaining elements of the Paris Agreement “rulebook,” particularly Article 6. Debates centered around issues such as double counting, the inclusion of Kyoto-era carbon credits, and whether a “share of proceeds” from carbon trading should support adaptation in vulnerable countries (Evans and Gabbatiss, 2019; Obergassel et al., 2020). The persistent disagreements led to a deadlock, highlighting the broader North-South divide in climate negotiations, where developed countries often prioritised market efficiency and flexibility, while developing countries, as well as several NGOs and Indigenous organisations, stressed equity, fairness, and climate justice. Whilst IPs certainly asserted their presence and demands in international climate negotiations at COP25, their efforts were often constrained by various forms of power dynamics, which played out through a combination of instrumental, structural, and discursive power.

5.2.1. Instrumental Power: Controlling Participation and Agendas

Instrumental power was evident in how the structure of COP25 meetings enabled governments and corporations to dominate the agenda while marginalising Indigenous voices. Indigenous participation in official climate decision-making spaces was limited, often to tokenistic roles. For example, according to Carmona (2023), although Indigenous representatives were invited to the Presidential Advisory Committee and later the Climate Action Advisory Committee, they felt their worldviews were dismissed and their proposals sidelined (Carmona, 2023). One participant described the experience as "David against Goliath," highlighting the unequal power dynamics that favoured corporate and state interests over Indigenous perspectives (Carmona, 2023). This reflects the instrumental power exerted by influential actors within these spaces to direct the conversation and outcomes in their favour. The tokenistic inclusion of Indigenous representatives and the lack of genuine engagement with their proposals can be seen as a form of symbolic inclusion that does not address the underlying power imbalances. This is consistent with the dynamics of carbon colonialism in that there is evidently a superior and an inferior worldview at play with carbon being the conduit for ongoing political, economic, and epistemological suppression.

At COP25, the final text for Article 6 notably excluded critical human rights safeguards, despite significant advocacy from civil society and several supportive Parties. Initial drafts included provisions for respecting human rights, protecting IPs, and establishing independent grievance mechanisms. However, these were progressively removed, leading to a final agreement that only addressed "negative social and environmental impacts" without specific human rights protections or robust safeguards (Evans and Gabbatiss, 2019; Obergassel et al., 2020; Newell and Taylor, 2022). Although some countries like Switzerland and Tuvalu, and various NGOs pushed for these protections, other Parties raised concerns about including human rights, questioned why other rights, such as the right to development, were not addressed, and emphasised that human rights issues fall under national jurisdiction (CIEL, 2019; IISD, 2019a). The final rules, developed by the Chilean Presidency, failed to incorporate essential elements such as comprehensive social and environmental safeguards and meaningful consultations with local communities. Consequently, the lack of these protections led to calls from civil society and Indigenous organisations for an extension of the negotiations to avoid repeating past mistakes and potentially harming vulnerable communities (CIEL, 2020). The final outcome reflected the instrumental power of influential states to shape norms and exclude safeguards they deemed inconvenient.

Furthermore, Indigenous critiques of market-based solutions, such as carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, reflect their resistance to the instrumental power of state and corporate actors. The ICA delegation challenged the Canadian negotiators by insisting on non-market solutions and demanding adherence to the UNDRIP, which mandates FPIC (Indigenous Climate Action, 2023). This opposition to carbon markets was supported by voices like Tom Goldtooth, Executive Director of the Indigenous Environmental Network, who criticised net-zero targets as "false solutions" that enable continued pollution and distract from genuine emissions reductions (IEN, n.d.). However, these demands were largely ignored in the official negotiations, demonstrating how instrumental power was used to maintain dominant economic approaches at the expense of alternative approaches. The focus on carbon market mechanisms at COP25, despite criticisms about their ineffectiveness and potential for double counting, underscores how wealthy nations (or major polluters) exert instrumental power to maintain their emissions-heavy practices. This dynamic fits the description of carbon colonialism, as it perpetuates the historical inequalities by shifting the burden of emissions reductions to poorer countries.

5.2.2. Structural Power: Exclusion by Design

The UNFCCC is structurally organized around a state-centric framework, wherein only nationally recognized governments possess formal decision-making power. This architecture inherently sidelines Indigenous Peoples, whose interests are rarely, if ever, represented by the states negotiating on their behalf. As Schroeder (2010) notes, the regime’s top-down design is more responsive to the vulnerability of entire states than to specific groups or nations within them. In practice, this means that Indigenous Peoples are subject to decisions taken in multilateral arenas that exclude their worldviews, rights, and governance systems (Carmona et al., 2023). The original 1992 UNFCCC text does not even mention Indigenous Peoples, reflecting a structural neglect that continues today through the ‘party-driven’ nature of the process—where inclusion is contingent on the discretion of state actors who often fail to recognize Indigenous sovereignty (Carmona et al., 2023; Gustafsson & Schilling-Vacaflor, 2022; Shea & Thornton, 2019). Moreover, national-level implementation of climate policies frequently treats Indigenous rights as bureaucratic hurdles rather than substantive commitments, offering top-down solutions that restrict meaningful participation (Carmona, 2023). As a result, global climate governance not only sidelines Indigenous Peoples procedurally but actively undermines their self-determination, reinforcing a globalist paradigm of market-based control that is fundamentally at odds with Indigenous values and visions.

Structural power also played a significant role in limiting the ability of Indigenous groups to influence the COP25 proceedings. Indigenous leaders reported feeling instrumentalized; their inclusion allowed the COP Presidency to project an image of inclusivity without genuinely engaging with their concerns. Carmona (2023) states that during the LCIPP pre-sessional meeting, Chilean Indigenous leaders presented a "Reflection and Proposal Document" to the COP president, who left the room shortly afterward without reading it. Furthermore, the rest of the meeting continued in English, which further marginalised non-English-speaking Indigenous representatives.

Indigenous representatives noted that civil society and IPs were often excluded from the actual negotiations. This exclusion meant that protest became one of the few available avenues for expressing dissent. Yet, even protests were tightly regulated; participants had to submit detailed protest plans for approval by the UNFCCC Secretariat, and any deviation could result in their exclusion from the event (Grosse and Mark, 2020). This regulation of dissent demonstrates how structural power is used to control the scope of acceptable discourse and limit the impact of alternative voices.

Furthermore, the geographical relocation of COP25 from Chile to Spain further compounded the exclusion of IPs and the Global South from participation in greater numbers. This move from a previously colonised country to a coloniser country was seen as a symbolic and practical shift that limited access and underscored power imbalances. Big Wind, a member of the all-Indigenous SustainUS delegation, expressed frustration that instead of connecting with IPs on Indigenous land, they found themselves in a European context with minimal Indigenous presence (Grosse and Mark, 2020). The irony of this relocation did not go unnoticed, as Indigenous leaders observed how their rights and voices were "muted daily under fascism and racism" in a forum dominated by corporate interests rather than Indigenous concerns (Indigenous Climate Action, 2023). This shift illustrates how structural power operates by setting the terms and locations that indirectly exclude marginalised voices.

5.2.3. Discursive Power: Reframing Climate Justice

In response to these constraints, IPs at COP25 sought to exercise their discursive power by reframing the narrative around climate justice. This discursive strategy was aimed at countering dominant narratives that prioritise market-based solutions and instead advocating for systemic changes that acknowledge Indigenous rights and stewardship, which can be framed as resistance against carbon colonialism. The dominant discourse promoted by powerful governments and corporations (e.g., the emphasis on “carbon market” and “net zero”) ignores or undermines Indigenous knowledge and rights, reflecting a form of discursive control that maintains existing power imbalances.

The Indigenous Climate Action (ICA) delegation, for instance, introduced the concept of "Land Back" as a way to emphasise the importance of Indigenous sovereignty and control over territories for meaningful climate action. The phrase "Land Back" became a central banner during the Climate Strike on December 6, inspiring other banners like "Oceans Back" and "Forests Back" (Indigenous Climate Action, 2023). As Dorries and Daigle (2024) argue, “Land Back” expresses a political vision rooted in the restoration of Indigenous land relations disrupted by colonial dispossession, racialized hierarchies, and extractive capitalism. It calls not only for the return of territory but for the resurgence of Indigenous governance, ecological care, and place-based freedom across borders. In this way, discursive strategies were used to expose the ideological underpinnings of the prevailing climate regime and push for climate action anchored in justice rather than market logic.

Despite being excluded from official negotiations, Indigenous delegates asserted their political agency through visible acts of resistance. On December 10, Indigenous leaders from Minga Indígena confronted the COP Presidency with a charter demanding more meaningful involvement of Indigenous communities in climate negotiations (Grosse and Mark, 2020). Although their numbers were reduced due to the relocation of COP25, their presence became a powerful tactic to make IPs visible and to inspire Indigenous youth activists, such as Big Wind (Grosse and Mark, 2020). This highlights a strategic use of both instrumental and discursive power to claim space within a highly controlled environment.

However, discursive power also faced limits. The structural constraints of the UNFCCC—state-centrism, language dominance, and restricted protest—meant that even powerful counter-narratives struggled to influence formal outcomes. This reinforces the argument that without addressing the deeper architecture of exclusion, discursive resistance alone cannot transform the system.

5.3. COP26 in Glasgow in 2021

COP26, held in Glasgow in November 2021, resulted in the "Glasgow Climate Pact," a 11-page document calling for a 45% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 compared to 2010 levels and noting that, under current national pledges, emissions would instead increase by nearly 14% by 2030 (Masood and Tollefson, 2021). The final text was softened to include a commitment to“phase down” rather than “phase out” coal, highlighting the need for lower-income countries to maintain subsidies for fossil fuels for now (Masood and Tollefson, 2021).

A significant outcome of COP26 was the resolution of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement (Minas, 2022). Article 6.2 enables countries to voluntarily cooperate in reducing emissions through the transfer of carbon credits. New rules were established to create an accounting system that prevents double-counting of emissions reductions when one country or company invests in emission reductions in another country (Masood and Tollefson, 2021). Article 6.4 introduces a new market mechanism that allows for the creation of a global carbon market, where states can purchase units to meet their NDCs. COP26 established the rules governing this mechanism, with further decisions left to a supervisory body composed of 12 independent experts. This body is responsible for developing methodologies, accrediting verification entities, and managing the Article 6.4 Registry to ensure transparency and accountability (UNFCCC, n.d.-b; Minas, 2022). Article 6.8 focuses on non-market approaches to climate cooperation, such as technology transfer and capacity-building. Decisions adopted at COP26 included the establishment of a work program to support non-market approaches, helping countries develop clean energy sources and foster cooperation in various areas (UNFCCC, n.d.-a).

5.3.1. Instrumental Power: Controlling Rules

While COP25 showcased entrenched barriers limiting Indigenous influence, COP26 revealed both the persistence of exclusionary power dynamics and emerging opportunities for Indigenous actors to assert more tangible influence within the climate governance arena. Tom Goldtooth, an Indigenous activist, lamented the lack of access to critical negotiating areas, forcing them “to try to grab people in the hallways” (Boyle, 2021). As Edson Krenak of Cultural Survival lamented, “IPs, as guardians of the land, did not sit at the table where negotiations and decisions were made” (Cultural Survival, 2022). Despite their critical insights and the scale of their delegations, their influence was confined to side events, with limited ability to shape final outcomes.

Indigenous lobbying efforts resulted in some recognition of Indigenous rights in the final provisions of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. While the language included references to human rights and Indigenous rights, it was criticised for being vague and insufficiently robust. The Indigenous delegation expressed disappointment that “we wanted to see an independent grievance mechanism… [and] the consultation provision in 6.4 is inadequate. It needs to include applicable international standards and ensure compliance with the rights of IPs to FPIC” (Cultural Survival, 2022). Jennifer Tauli Corpuz of Nia Tero noted that while the new rules provide more protections than previous frameworks, they are still relatively weak, emphasising the need for vigilant monitoring of their implementation (Masood and Tollefson, 2021).

Despite constraints, Indigenous leaders achieved some strategic gains that demonstrated their capacity to exercise instrumental power and convert it into structural transformation. One notable example was the introduction of the Shandia mechanism by Tuntiak Katan, General Coordinator of the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC) and Vice Coordinator of the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin, during a panel at COP26. Describing it as a “new dawn,” Katan explained that this initiative would enable “greater financing on the ground, direct access to international financial funds by Indigenous organisations and peoples to defend our rights, territorial rights, economic rights, cultural rights, collective rights” (Laing, 2023). This initiative, launched by the GATC in 2022 and governed by its Leadership Council, represents a concrete exercise of instrumental power—using strategic action within COP spaces to achieve a specific institutional outcome. At the same time, Shandia also exemplifies structural power, as it reconfigures the financial architecture of climate governance. By supporting the establishment of territorial funding mechanisms, facilitating the flow of funds, and strengthening institutional capacities of Indigenous communities to manage resources effectively, thus enabling Indigenous communities to bypass traditional intermediaries and directly manage climate finance, Shandia challenges top-down funding approaches and reinforces Indigenous autonomy, governance, and self-determination over their territories (GATC, 2023). In this way, the instrumental power mobilized by Indigenous actors at COP26 resulted in a tangible structural shift, marking a rare but significant success in altering the deeper systems that typically marginalise Indigenous participation in climate policy.

5.3.2. Structural Power: Exclusion by Design

IPs were highly visible at COP26, participating in multiple event spaces and making powerful interventions. For the first time, an Indigenous Peoples’ Pavilion was included in the Blue Zone, the main event area for accredited attendees, providing a platform for Indigenous voices (Laing, 2023). At the Opening Ceremony of the World Leaders Summit, Amazonian youth activist Txai Suruí delivered a moving speech highlighting the environmental crises facing her community (Laing, 2023). These moments of visibility also demonstrate a form of discursive power with Indigenous leaders seeking to challenge prevailing narratives and inserting their perspectives into the global climate dialogue.

At COP26, the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP) marked a significant moment in the consolidation of Indigenous structural power within the UNFCCC framework. The Facilitative Working Group (FWG), composed equally of self-selected Indigenous representatives and state delegates, successfully co-constructed and secured the adoption of the second three-year work plan (2022–2024), a decision that acknowledged both the progress and future direction of Indigenous inclusion in climate governance (Cultural Survival, 2022; Carmona et al., 2023). Most notably, COP26 hosted the first-ever Knowledge Holders Gathering within the Blue Zone—an unprecedented event that created a protected space exclusively for Indigenous Peoples, with States explicitly asked not to attend. This gathering included both internal roundtables on topics such as food systems, biodiversity, and intergenerational knowledge, and a participatory dialogue with Parties (Cultural Survival, 2022; Carmona et al., 2023). As Graeme Reed (Anishinabee), co-chair of the IIPFCC, highlighted, this initiative demonstrated a growing capacity of Indigenous Peoples to institutionalise their own epistemologies within a system historically dominated by state-centric and technocratic approaches (Cultural Survival, 2022). Additionally, Indigenous leaders secured a seat in the Climate Technology Centre and Network Advisory Body, a modest but symbolically important step in embedding Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into global climate technology discourses (Carmona et al., 2023). These developments exemplify how Indigenous actors, through sustained advocacy and platform-building, are reshaping the governance architecture from within—an expression of structural power that reflects both decolonial resistance and strategic institutional engagement.

The overall experience of Indigenous representatives at COP26 suggests that significant challenges remain. Although the UK government promoted COP26 as the most inclusive summit ever, structural barriers such as visa issues and restrictive travel rules prevented about two-thirds of civil society organisations, particularly those from the Global South, from attending (The Lakhani, 2021). These barriers reflect broader structural power dynamics within the UNFCCC process that determine who has the ability to be present and participate.

5.3.3. Discursive Power: Reframing Climate Narratives

The general view of IPs at COP26 was one of profound disillusionment with the existing power structures. For instance, Chief Ninawa Inu Huni Kuin, president of the Huni Kuin People’s Federation of the Brazilian Amazon, stated, “Our vision is very different from those who make the decisions at COP. We have ancestral connections to the environment and Mother Earth. These are spiritual spaces that we would never negotiate or offset for money” (Lakhani, 2021). This rhetoric underscores IPs' critique of carbon market mechanisms, which are often presented as nature-based solutions. Galina Angarova of Cultural Survival criticised these mechanisms for lacking specific provisions to ensure FPIC, and for potentially commodifying nature in ways that are inconsistent with Indigenous values (Cultural Survival, 2022). In voicing these critiques, Indigenous leaders are not merely rejecting specific market mechanisms—they are wielding discursive power to advance a fundamentally different ontological framework, one that resists the reduction of nature to tradable units and reclaims climate action as a matter of relational responsibility, reciprocity, and spiritual continuity. In this sense, their interventions constitute acts of epistemic resistance, challenging the extractive logic at the heart of global climate governance.

Indigenous activists also employed discursive power through direct action and protests to disrupt the narratives around carbon markets and offsetting schemes. During a panel on carbon offsets at COP26, Greta Thunberg and Greenpeace members interrupted the proceedings, denouncing the practice as “greenwashing” (Boyle, 2021). At the same protest, about 20 Indigenous members of the Indigenous Environmental Network protested outside an event promoting the expansion of voluntary carbon markets by Shell, BP, and other fossil fuel companies. They held copies of a full-page advert published in major newspapers that read: “Carbon offsetting is tearing us apart” (Greenpeace, 2021). These acts of protest were aimed at challenging the credibility of market-based solutions and bringing attention to the systemic injustices they perpetuate.

Also, these protests gained significant international media attention, helping to elevate Indigenous critiques of carbon markets. For example, The Independent ran the headline “Cop26: Carbon offsetting ‘a new form of colonialism,’ says Indigenous leader’” (Boyle, 2021), while The Guardian published “‘A continuation of colonialism’: indigenous activists say their voices are missing at Cop26” (Lakhani, 2021). Such coverage broadened public awareness and amplified Indigenous demands for climate justice beyond formal negotiations.

Table 2.

Types of Power and Their Examples from COP25 and COP26.

Table 2.

Types of Power and Their Examples from COP25 and COP26.

| Power Type |

COP25 (Madrid, 2019) |

COP26 (Glasgow, 2021) |

|

Instrumental Power(Direct influence on rules, outcomes, decisions)

|

- IPs excluded from Article 6 negotiations, despite their large presence.

- Denied access to negotiation rooms; forced to lobby in hallways.

- Demanded binding human rights, FPIC, and a grievance mechanism under Art. 6.4.

- Final text excluded binding rights language; only vague references.

- Resistance from some Parties who viewed rights as “outside the scope.”

- Minimal influence over final outcomes. |

- Achieved reference to human and Indigenous rights in Article 6 rules — but still non-binding, vague.

- No grievance mechanism, inadequate consultation provisions, and lack of FPIC compliance standards.

- Jennifer Tauli Corpuz: new rules offer more protection than before, but still insufficient.

- Shandia Mechanism introduced by GATC: enables direct funding access by IPs, bypassing intermediaries — a major success, turning instrumental power into structural shift. |

|

Structural Power(Access to institutions, participation rules, systemic inclusion/exclusion)

|

- LCIPP FWG formally operationalised: co-governance model with 7 IP reps and 7 state delegates.

- Adopted the first 3-year work plan (2020–2022).

- UNFCCC remained state-dominated; IPs had no formal decision-making power in broader negotiations.

- COP25 relocation from Chile to Spain severely restricted IP and Global South participation. - Move seen as a colonial reversal, limiting Indigenous presence.

- Delegates like Big Wind described how the shift muted Indigenous voices in a corporate, Eurocentric space. |

- LCIPP’s second 3-year work plan (2022–2024) co-produced and adopted.

- Held first Knowledge Holders Gathering in Blue Zone: a protected, IP-only space (states explicitly excluded).

- Topics included biodiversity, intergenerational knowledge, and food systems.

- An Indigenous representative secured a seat in the CTCN Advisory Board — symbolic structural inclusion.

- Despite “most inclusive COP” claims, 2/3 of Global South CSOs excluded due to visa/travel barriers.

- These exclusions highlight persistent gatekeeping in participation mechanisms. |

|

Discursive Power(Ability to shape narratives, meaning, values, worldviews)

|

- IPs framed carbon markets as “carbon colonialism”, rooted in extractive logic.

- Rejected market mechanisms inconsistent with relational ontologies, ancestral duty, and spiritual connection to nature.

- Discourse often dismissed or sidelined within state-centric, technocratic spaces.

- Viewed as political or ideological rather than legitimate alternatives. |

- IP voices reframed markets as colonial impositions: “We do not offset or sell the sacred” (Ninawa Inu Huni Kuin).

- Galina Angarova: carbon markets commodify nature, lack FPIC.

- IPs staged direct action protests, including against Shell and BP offset events: “Carbon offsetting is tearing us apart.”

- Joined by Greta Thunberg and Greenpeace to denounce greenwashing.

- Gained strong media amplification (e.g. The Guardian, The Independent) — spreading counter-narratives globally.

- Employed epistemic resistance, challenging dominant paradigms with Indigenous cosmologies. |

6. Discussion

COP25 and COP26 saw the finalisation of the rulebook for Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. It illustrated the clash of worldviews and uneven power dynamics between states and multinational corporations supporting carbon markets under neoliberal principles, on the one hand, and IPs seeing it as a form of carbon colonialism, on the other.

6.1. Power Dynamics in Carbon Market Creation in COPs

In terms of structural power, which involves shaping the context, rules, and institutions in ways that align with an actor’s interests, there was an asymmetric power relation due to the state-centric nature of the UNFCCC. In the decision-making process, IPs, who hold observer status unless included in a national delegation, had minimal impact and faced marginalisation (See

Appendix B).

While powerful international neoliberal organisations tried to shape carbon market mechanisms under Article 6 with powerful coalitions (e.g., Partnership for Market Implementation and CPLC), IPs experienced difficulties even attending COPs. Furthermore, even though the visibility of IPs increased at COP26 (Laing, 2023), the persistent issues of participation and inclusion have not changed significantly across the conferences. This marginalisation and exclusion from decision-making processes results in a form of carbon colonialism where powerful actors dominate carbon governance structures and impose policies in the name of climate change that deny the rights and destroy the livelihoods and ways of life of IPs (Bachram 2004; Bumpus and Liverman, 2010).

Due to their exclusion from the structural sphere of the UNFCCC, IPs have limited instrumental power—the capacity to directly influence or coerce others to achieve specific outcomes. Their lack of influence on the decision-making process, coupled with their comparatively minimal economic and political power relative to influential political, financial and corporate actors such as the USA, the World Bank, and Shell, has further deepened asymmetric power relations. For instance, while the USA can shape global climate governance and wield its instrumental power by withdrawing from the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement (Pickering et al., 2018), IPs are "forced to try to grab people in the hallways" (Boyle, 2021) just to engage in discussions with other actors. At COP meetings, IPs have resorted to methods like protesting to amplify their instrumental power; however, the effectiveness of such actions is questionable when confronted with powerful states and corporations.

6.2. Impact of Indigenous Peoples in This Process

Through the UNFCCC process, the main approach of IPs was their discursive power, which is the ability to shape the identity, perceptions, and preferences of other actors through the control of discourse. In this discourse, the main argument was carbon colonialism. IPs oppose the commodification of carbon due to their spiritual and ancestral connections to the environment, viewing Mother Earth as a sacred entity that should not be negotiated or offset for monetary gain (Lakhani, 2021). Therefore, the creation of a carbon market under Article 6 was an attempt to institutionalise a new type of colonialism.

Although IPs opposed the creation of market mechanisms, asymmetric structural and instrumental power relations led to the inevitable finalisation of Article 6. Consequently, the discourse shifted towards the protection of Indigenous rights within the carbon market. In this context, IPs prioritised the concepts of indigenous rights and FPIC in COP25 and COP26. As a partial success, they utilised discursive power to advocate for the inclusion of human rights considerations in Article 6. While their demands, such as an independent grievance mechanism and improved consultation provisions, were only partially addressed (Cultural Survival, 2022), this advocacy represents a notable exercise of discursive power.

On the other hand, pro-carbon market actors—primarily Global North governments, corporations, and affiliated organizations—exercised discursive power by promoting the concept of “nature-based solutions.” While the term lacks a universally agreed definition, it generally refers to the use of natural ecosystems, such as forests and wetlands, to address climate and environmental challenges (Foster, 2024). Within the Article 6 framework, especially under Article 6.2, nature-based solutions have been presented as a means of achieving emissions reductions through ecosystem protection, restoration, and management (EDF, 2023). However, IPs and their allies have criticised this discourse for obscuring the market-based logic behind these initiatives. By framing carbon offset projects in terms that sound ecological and cooperative, proponents of nature-based solutions effectively rebrand mechanisms of the carbon market, which Indigenous leaders argue perpetuate colonial dynamics under a different name (Cultural Survival, 2022). Thus, nature-based solutions function not just as technical proposals, but as discursive tools that legitimize carbon commodification while downplaying its socio-political consequences.

7. Conclusions

This research has explored the intersection of climate governance, carbon markets, and IPs' rights within the framework of the UNFCCC. The development and implementation of carbon market mechanisms under the UNFCCC, particularly those associated with Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, illustrate a profound tension between economic efficiency and justice. While these mechanisms were designed to incentivize emissions reductions and facilitate global cooperation with neoliberal values, they have often perpetuated existing inequalities and exploitations of Indigenous lands, giving rise to the concept of "carbon colonialism." This concept is crucial for understanding the power dynamics observed at COP25 and COP26, where IPs and Global South countries have faced significant barriers.

At COP25, the relocation of the conference from Chile to Spain made a significant difference in the ability of IPs to participate, highlighting the structural obstacles they faced. Despite increased visibility at COP26, Indigenous representatives encountered limitations in access and influence, reflecting broader systemic inequities. Furthermore, the UNFCCC’s state-centric structure, which prioritises the interests and participation of states, further compounded these difficulties by structurally sidelining non-state actors such as IPs. These challenges highlight how the structure of COPs can inadvertently reinforce historical injustices rather than address them.

Instrumentally, the negotiations have often prioritised market efficiency over equitable outcomes, highlighting the persistent legacy of carbon colonialism. Powerful actors benefiting from the neoliberal status quo have worked to protect their interests within the UNFCCC process. For example, IETA expressed deep regret over the politicisation of the Article 6.4 mechanism at COP28, arguing that delays and micromanagement have obstructed the establishment of a reliable crediting system and hindered progress toward effective international carbon markets and net zero emissions (IETA, 2023). This focus on economic efficiency often disenfranchises Indigenous voices and interests, as decisions made under these frameworks frequently fail to fully account for the social and environmental impacts on affected communities.

Discursively, as their primary means of influence, Indigenous activists have critiqued market-based solutions like carbon offsets as forms of ‘greenwashing,’ arguing that these approaches overlook deeper systemic issues such as the legacy of colonial land dispossession, extractive economic systems, and ongoing exclusion from climate decision-making spaces—the root causes of climate and environmental injustice (Martin et al. 2020). For IPs, the real problem is that climate policy often treats land and ecosystems as commodities to be managed, sold, or offset, rather than as sacred ancestral territories with spiritual, cultural, and sovereign significance. As a result, market-driven mechanisms risk reinforcing the same structures that have historically undermined Indigenous rights. IPs have utilised methods such as protests and emotive speeches during the COPs to influence public perception and decision-making, and to defend their fundamental rights. While they achieved partial success in incorporating human rights into Article 6, they remain dissatisfied with the outcomes, which they believe could still exacerbate carbon colonialism. Meanwhile, nature-based solutions, which are estimated to contribute 37% of the required climate change mitigation by 2030 (IPBES, 2019), are promoted by carbon market supporters as a promising remedy. However, this optimistic framing contrasts sharply with the grim reality that deforestation is continuing, soil health is depleting, ecosystems are degrading and biodiversity is being lost rapidly. This disparity underscores the urgent need for more effective and equitable action to protect ecosystems and human livelihoods, as the current reliance on market mechanisms and nature-based solutions fails to address the fundamental inequities and risks worsening social and environmental impacts.

In light of these findings, it is clear that while carbon markets and related mechanisms are integral to current climate approaches due to the domination of neoliberal policies in global dynamics, they must transform to safeguard the needs and rights of IPs. To counteract carbon colonialism, policy recommendations should prioritise the integration of human rights safeguards in carbon market mechanisms at the very least, ensuring that Indigenous rights and FPIC are fully respected. Additionally, promoting Indigenous-led conservation efforts and embracing alternative, non-market-based approaches to ecological restoration and rebalancing can help shift the focus from commodifying carbon to empowering communities and preserving ecosystems in a just and equitable manner.

Author Contributions

Z.D. designed the research, collected and analyzed the literature, and planned and wrote the manuscript; H.S. supervised the research and contributed to planning, revising, and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by …..

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. What IEN Says About Carbon Offsets

The table contrasts common justifications for carbon offsets with critical counterpoints, highlighting that carbon offsets often fail to deliver genuine emissions reductions, can disadvantage Indigenous communities, and suffer from flawed accounting and market mechanisms (Source: IEN, 2023).

| What They Say |

What We Say |

| Carbon offsets reduce pollution. |

- -

Carbon trading and offsets delay and diminish greenhouse gas emissions phase out, allowing dirty industry to continue business as usual. - -

Direct emissions reductions through phasing out fossil fuels is the principal and most important way to stop climate change. |

| Carbon offsets create incentives for Indigenous Peoples. |

- -

Payments are not promised to communities in carbon offset projects, but often depend on various verifications in order to receive payment if it is received at all. - -

If payments do arrive, misuse and division have been reported. Funds may further undermine land tenure, conservation, and local benefits by driving up prices. - -

Years of data demonstrates that FPIC and the rights of Indigenous Peoples have not been upheld in carbon offset projects. - -

While Indigenous Peoples are solicited to sign contracts under the reasoning that it is a 'rights' issue for Indigenous Peoples because of the carbon in the forests, we have observed conflict and divisions over the deeper question of how to reconcile the ownership of carbon within the cosmovision (spirituality) beliefs of - -

Indigenous Peoples’ communities in participating in the commodification and privatization of carbon. - -

Carbon offsets reinforce the privatization of nature. |

| We must track greenhouse gas emissions. |

- -

Current carbon accounting frameworks all fail to address essential quality criteria such as additionality, baseline setting, transparency and permanence. - -

The lack of data integrity and availability, coupled with large margins of errors, uncertainties, and biases in carbon offset outcomes, undermines the credibility and effectiveness of any tracking methods. - -

Carbon accounting efforts in the service of setting up a carbon market poses a conflict of interest because if emissions are overestimated then companies can claim higher reductions. |

| The market will take care of reducing emissions over time. |

- -

Carbon markets rearrange emissions on a spreadsheet rather than materially reducing emissions. - -

Far too often, forest offsets brokers and managers have targeted Indigenous Peoples, driven up land prices, and forced Indigenous communities from their territories. |

Appendix B. Summary of Key Limitations and Achievements of the LCIPP

The table below provides a synthesized overview of the main institutional, structural, and practical limitations faced by the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP), as well as its most significant achievements at the international, national, and local levels. It highlights unique challenges, concrete impacts, and illustrative examples based on evidence presented in Carmona et al. (2023).

| Aspect |

Limitations |

Achievements / Impacts |

| Institutional & Structural |