1. Introduction

International trade in tropical hardwoods is embedded in a complex nexus of economic, environmental, and geopolitical dynamics. For several decades, tropical wood products—particularly tropical hardwood sawnwood—have constituted a central component of North–South trade flows, characterized by persistent structural asymmetries between producer countries, predominantly located in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America, and consumer markets, largely concentrated within OECD economies [

1,

2]. This trade architecture is shaped by a historically unequal international division of labor, wherein Southern countries typically export raw or semi-processed timber, while Northern countries specialize in industrial transformation and rent appropriation [

3,

4]. Although globalization has expanded market access and increased traded volumes, it has also deepened the structural dependency of tropical forest economies on external demand and price volatility [

5].

Despite the implementation of Local Timber Processing (LTP) policies in several producer countries, the transition from extractive forestry to a value-added industrial model remains elusive. Structural bottlenecks—including technological backwardness, weak institutions, trade barriers, and inadequate infrastructure—have hindered efforts to foster domestic transformation and economic diversification [

6,

7]. These limitations raise critical questions about the capacity of tropical countries to sustainably harness their forest wealth within an integrated development and forest governance framework [

8,

9].

In this context, tropical hardwood sawnwood emerges as a strategic product for examining disparities in integration into global timber value chains. Unlike logs, whose export is increasingly regulated or banned, sawnwood occupies an intermediate position in the value chain, linking resource extraction to industrial policy, trade agreements, and environmental traceability requirements [

10,

11]. Yet, surprisingly few empirical studies have systematically modeled the determinants of sawnwood exports using dynamic panel data with broad spatial and temporal coverage. Much of the existing literature is either qualitative or focused on country-specific case studies, thereby lacking in generalizability and robustness [

12,

13].

This article addresses this gap by proposing a comprehensive econometric analysis of sawnwood export dynamics among ITTO member states, grounded in a hybrid theoretical framework that draws from international political economy and political ecology. Unlike previous studies, it incorporates a wide range of structural variables—such as colonial path dependency, industrial specialization, infrastructural connectivity, and digital traceability mechanisms—into the analysis. In doing so, it introduces new conceptual tools, including “pathological dependence” and a “Fair and Digital Tropical Timber Trade Model,” to better explain observed asymmetries and identify strategic levers for rebalancing and sustainable industrialization.

Issues

To what extent do macroeconomic, demographic, forestry, and structural factors influence tropical hardwood sawnwood exports among ITTO member countries? Why do some countries perform significantly better than others in this segment, and how can observed disparities in specialization and competitiveness be explained? Can we envisage the emergence of a more equitable and digitally governed model of tropical timber trade?

Research Questions

What are the main structural and cyclical determinants of tropical hardwood sawnwood exports in ITTO member countries?

How do economic (GDP growth, population), forestry (production capacity, processing intensity), and commercial (prices, logistics infrastructure) variables interact in explaining export performance?

Is it possible to classify exporting countries based on their specialization profile and degree of integration into tropical timber value chains?

What policy strategies can foster rebalancing and sustainable industrial development in producing basins?

Research Hypotheses

H1: Economic growth (GDP per capita) positively influences sawnwood exports by stimulating production and processing capacity.

H2: Larger populations, as proxies for domestic consumption and resource pressure, negatively impact net exports.

H3: Higher levels of local wood processing (measured by on-site transformation rates) are positively correlated with export performance.

H4: Countries with integrated logistics (ports, transport infrastructure, digital traceability) are more competitive in high-value markets.

H5: Path dependency—stemming from colonial legacies and transnational corporate structures—continues to shape the geography of trade flows.

H6: Alternative economic models integrating technological innovation, regional alliances, and environmental governance can support long-term industrial rebalancing.

Study Objectives

This article seeks to advance the empirical literature on tropical timber trade by employing dynamic panel econometrics on a robust dataset covering 58 ITTO producer countries over the period 1995–2022. It aims to bridge theoretical and empirical divides by integrating macroeconomic, forestry, trade, and structural variables within a unified analytical framework. In addition to mapping the determinants and typologies of sawnwood exporters, it develops concrete policy recommendations to enhance competitiveness and sustainability in the Global South, particularly in underdeveloped production basins. The study ultimately proposes a paradigm shift through the construction of a “Fair and Digital Timber Trade Model,” incorporating mirror clauses, blockchain-based traceability, and regional industrial cooperation mechanisms.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Effects of Tropical Timber Exports on Economic and Demographic Variables

Tropical timber exports have a significant impact on forest production, economic growth, global imports, population dynamics, industrial transformation and the structuring of trade flows. They stimulate the exploitation of timber resources, sometimes to the detriment of ecological sustainability [

14]. In Cameroon, the surtax on log exports has encouraged local processing, with the forestry sector growing by 12.2% by the end of 2023 (La Voix du Centre, 2024; [

15]). However, a total ban on logs could harm competitiveness and employment in the short term (Mpabe Bodjongo & Fotso Mbobda, 2021; [

16]), as illustrated by the case of Gabon, faced with overexploitation and a lack of policy monitoring (FAO, 2001; [

17]). Economically, these exports represent an important source of foreign currency and support growth in countries dependent on natural resources [

18], contributing for example to a 0.5-point increase in Cameroon’s GDP by the end of 2023 (La Voix du Centre, 2024; [

19]). However, they also expose us to the volatility of world markets and the perverse effects of the “resource curse” (Sachs & Warner, 1999; [

20]), or even to relative deindustrialization through “Dutch disease” [

21]. On the commercial front, import flows have been marked by high volatility: after a peak of USD 1.05 billion in imports to Europe in early 2022 (FAO, 2001), a fall of 18% in volume and 27% in value has been observed in 2023, reflecting the market’s fragility in the face of geopolitical shocks [

1]. However, some countries, such as those in South-East Asia, are integrating these flows into high-value-added processing chains [

22,

23]. From a socio-environmental point of view, illegal logging contributes to deforestation, loss of livelihoods and internal migration (La Voix du Centre, 2024; [

24,

25]), while promoting increased health risks (Du, Li & Zou, 2024). To meet these challenges, local processing appears to be a major strategic lever [

26], although hampered by structural constraints: insufficient infrastructure, high costs, limited access to financing, and FSC/PEFC certification requirements [

27]. Despite proactive policies in Gabon, the majority of local companies still struggle to meet international standards (La Voix du Centre, 2024; [

28]). Finally, the typology of flows reveals a dichotomy between exporters of raw products (Gabon, Congo) and re-exporters with high added value (Vietnam, China), depending on their level of industrial integration [

29,

30,

31]. These movements are influenced by trade agreements, environmental regulations (EUTR, FLEGT) and sector competitiveness [

23,

32].

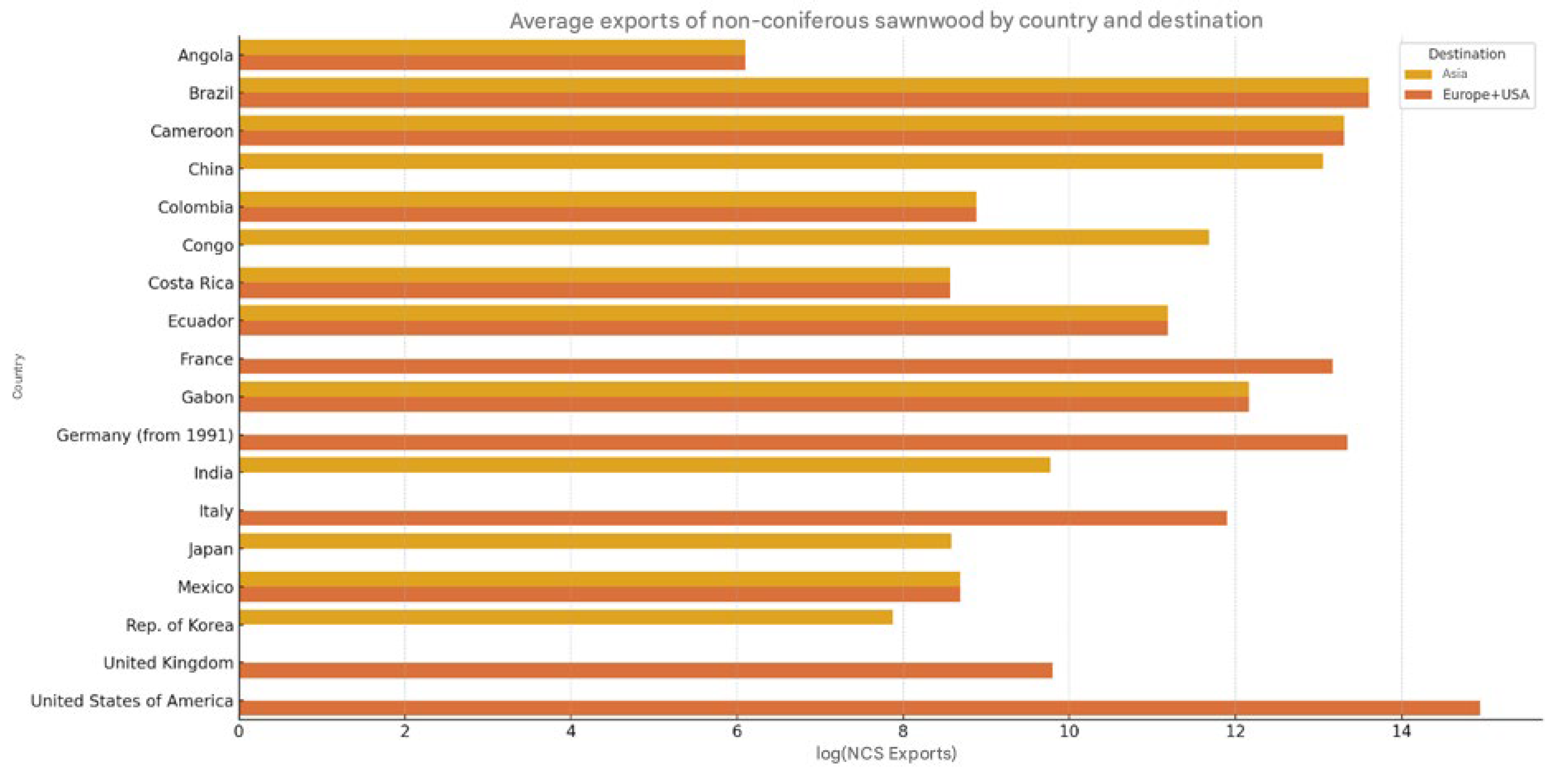

2.2. Tropical Hardwood Timber Market Dynamics: An Integrated Regional Analysis (1995-2022)

The international trade in tropical hardwood sawnwood presents a complex economic geography, characterized by asymmetrical interdependencies between producing basins and consuming regions. As demonstrated by ITTO data (2023), this market is structured along four major axes: Africa-Europe/USA, Africa-Asia, America-Asia and America-Europe/USA, each with specific dynamics reflecting regional economic specializations. This study proposes an integrated analysis of these trade flows by mobilizing the theoretical frameworks of international political economy (Deacon, 2020) and political ecology (Robbins, 2019), thus enabling a nuanced understanding of contemporary issues related to this sector.

2.2.1. Africa-Europe/United States Flows (1995-2022): A Changing Historical Relationship

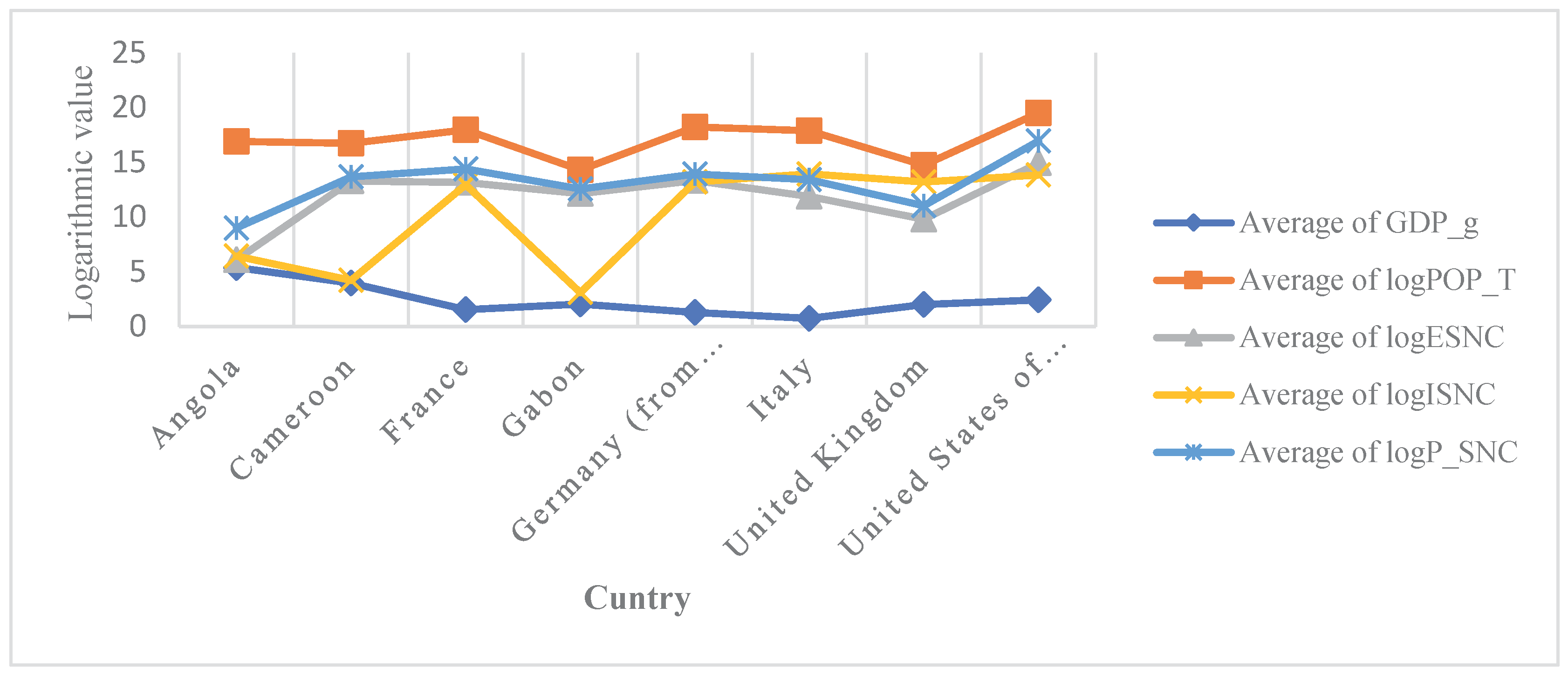

Analysis of trade between tropical Africa and developed economies shows that European countries, notably France, Germany and Italy, as well as the USA, have high logISNC values, confirming their status as net importers of tropical hardwood sawnwood. France stands out with a particular profile, displaying simultaneously high values for imports (logISNC) and exports (logESNC). This suggests a crucial role in the re-export and local processing of these products, giving it a strategic position in the value chain.

African countries, in particular Gabon and Cameroon, show significant levels of exports (average logESNC of 256.260 m3) but relatively homogeneous production (logP_SNC), indicating limited industrial capacities. This situation is exacerbated by often inadequate infrastructure and limited access to modern technologies, which hampers the development of a robust local industry.

Trade between tropical Africa (Gabon, Cameroon, Congo) and Western economies reveals a persistence of colonial patterns, albeit modified by the emergence of new regulations. Data show that African exports (ESNC) average 256,260 m

3/year (ITTO, 2023), and that France and Germany together absorb 45% of European imports [

35]. However, the local processing rate does not exceed 15% in African countries (World Bank, 2021), underlining the vulnerability of these economies to international market fluctuations.

As noted by Karsenty and Ongolo (2021), this configuration perpetuates a “pathological dependence”, where producing countries remain confined to the role of suppliers of raw materials. However, the introduction of FSC certifications (35% of Europe-Africa flows) marks a timid transition towards more sustainable practices, as indicated by the work of Cerutti et al. (2021), who highlight the growing importance of environmental standards in trade.

2.2.2. Africa-Asia flows (1995-2022): The Emergence of a New Paradigm

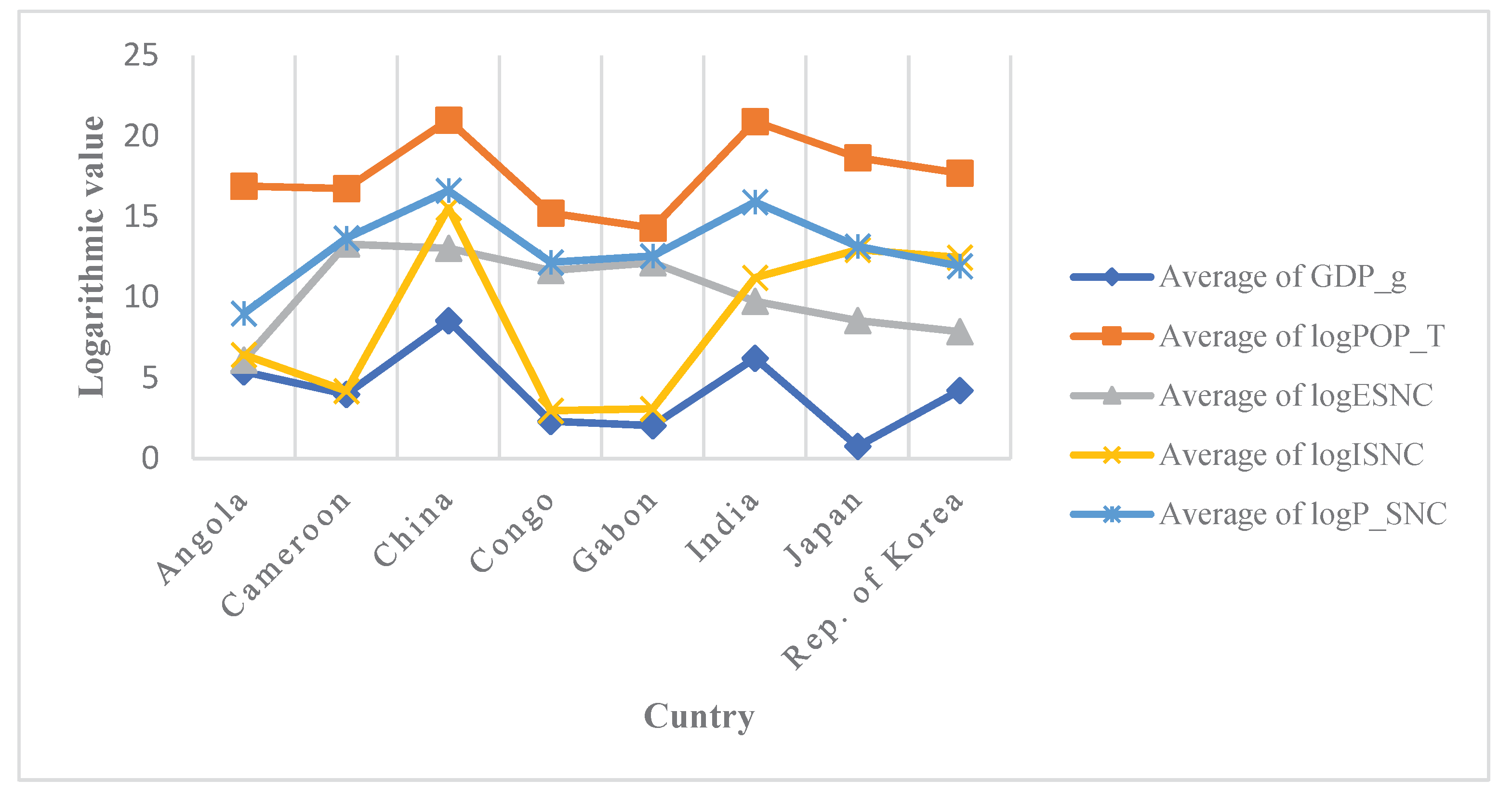

Trade with Asia presents different characteristics, with China dominating imports (average logISNC of 1,011,724 m3), while Japan and South Korea maintain stable but high levels. The rise of China as a major importer has altered trade dynamics, leading to a reconfiguration of flows and economic relations.

African countries maintain their position as exporters, but with production capacities (logP_SNC) below their potential, as evidenced by the high standard deviation between countries (ET=527.390). Analysis of Africa-Asia trade reveals a major reconfiguration of trade routes, with China now accounting for 30% of Asian imports [

1]. African countries are maintaining stable exports (average logESNC of 5.8), but these exports have low added value, which limits the economic benefits for producing countries.

The certification rate remains low (12% versus 35% for Europe-Africa flows), raising concerns about the sustainability of trade practices. Sun and Canby (2021) speak of a Chinese “quantitative imperative” that prioritizes volumes over environmental considerations, posing major challenges for the sustainable management of forests in the Congo Basin, where the deforestation rate stands at 0.18%/year (GFW, 2023). This situation calls for a rethink of commercial and environmental policies, in order to reconcile economic development with the protection of forest resources.

2.2.3. America-Asia Flows (1995-2022): Brazilian Domination

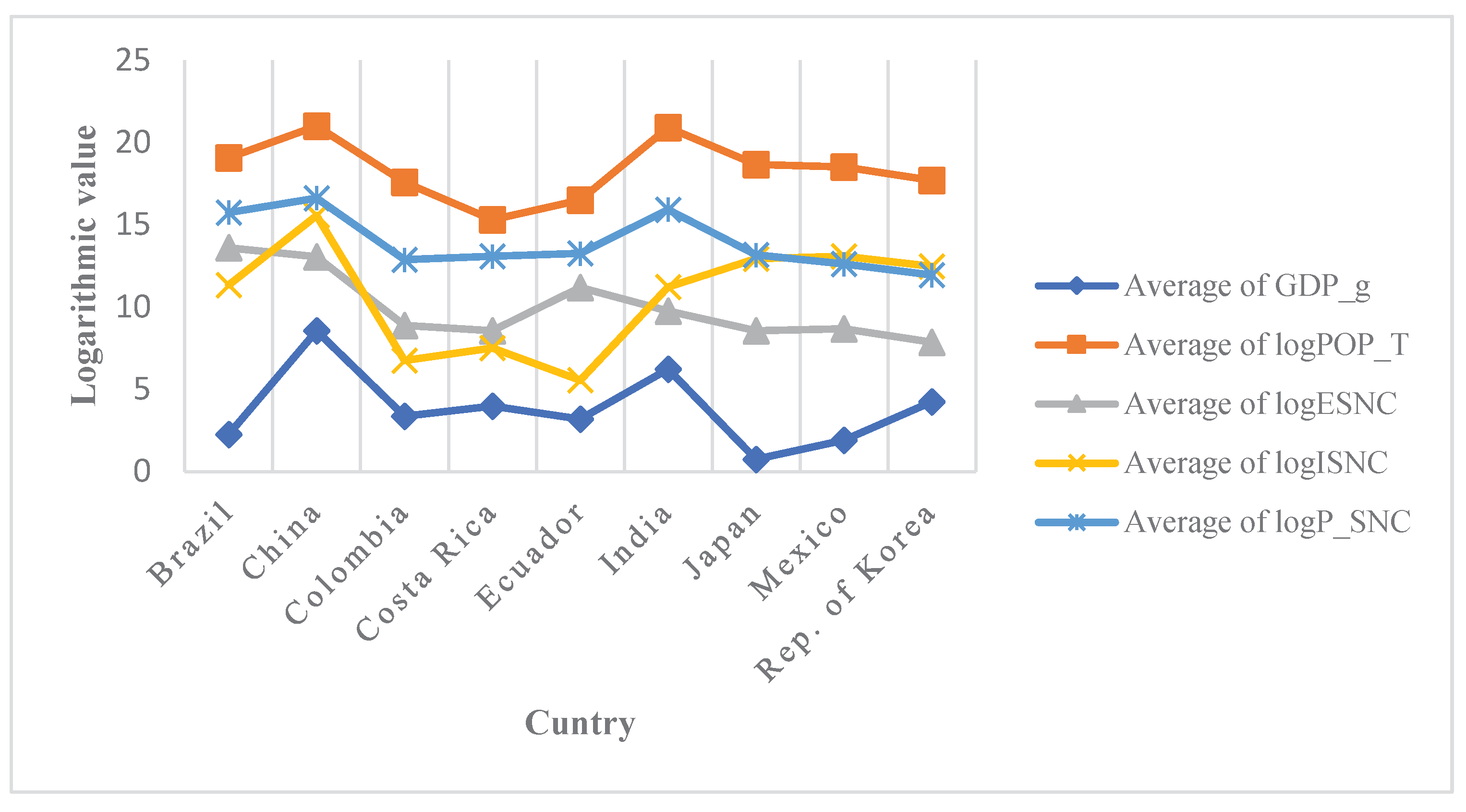

The graph below highlights the dominance of South America, and Brazil in particular, in supplying Asia with tropical wood. Brazil combines abundant production, massive exports and sustained economic growth. This flow illustrates a global rebalancing, in which Latin America is emerging as a strategic player in the face of growing Asian demand.

Brazil is a key player in transcontinental flows, with record production (P_SNC) of 5.3 million m3/year (ITTO, 2023). Exports (ESNC) are 60% concentrated in three main markets: China, the United States and the European Union. This concentration of exports underlines Brazil’s dependence on a few key markets, making it vulnerable to economic fluctuations and changes in trade policy in these regions.

In addition, flows to Asia will grow by 7.2% per year between 2015 and 2022, demonstrating Asia’s growing importance in the tropical hardwood lumber trade. However, this expansion is accompanied by alarming Amazon deforestation (0.32%/year), calling into question the effectiveness of current sustainability policies. Nepstad et al. (2022) point out that this dynamic threatens not only local ecosystems, but also international commitments to sustainability and the fight against climate change.

2.2.4. America-Europe/United States Flows (1995-2022): Stability and Certification

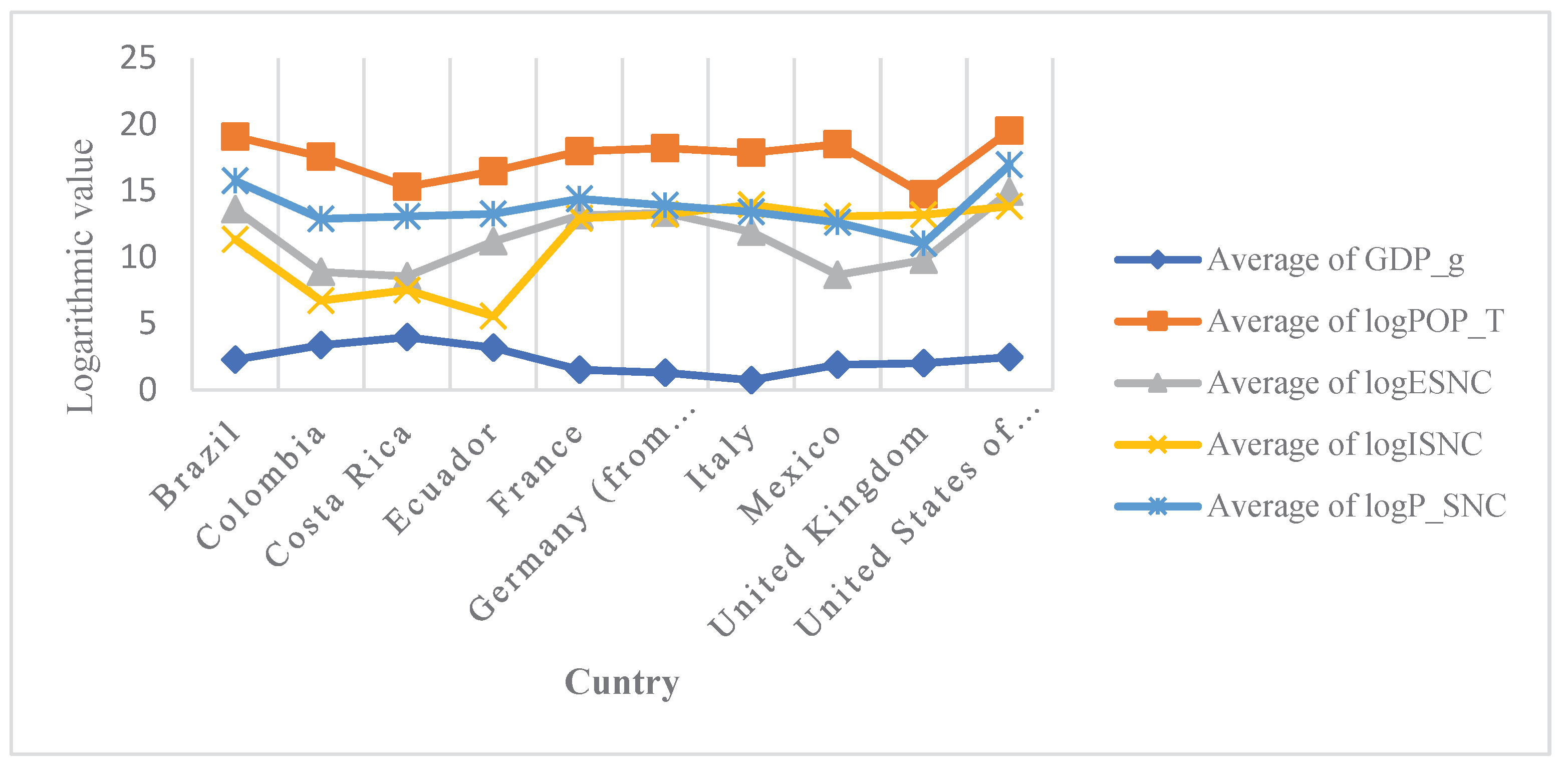

Transatlantic trade shows distinct characteristics, notably a predominance of FSC certifications (45% of volumes), reflecting growing demand for sustainable and responsible products. This trend is reinforced by a higher level of local processing (ratio 1:3 vs. 1:8 in Africa), indicating a greater capacity to valorize resources locally.

Demand on these markets is stable but demanding in terms of quality, prompting producers to improve their production standards. Hurmeksoki et al. (2022) see the emergence of a “qualitative model” in contrast to the quantitative Asian approach, underlining the importance of quality and sustainability in transatlantic trade.

2.3. Towards Multi-Level Governance

Comparative analysis reveals the need for a differentiated approach by trade basin. It is essential to strengthen African industrial capacities (World Bank, 2021), with an emphasis on training, access to technology and infrastructure development. In addition, it is crucial to frame Asian demand through bilateral agreements (Sun, 2023) that promote sustainable trade practices.

Finally, the consolidation of European sustainability standards (EU FLEGT, 2022) is essential to ensure that trade does not compromise the health of tropical ecosystems. As Cashore (2023) suggests, only multi-level governance involving public, private and civil society players can reconcile economic development with the preservation of tropical ecosystems. This collaborative approach is essential to create a framework conducive to sustainability while promoting economic growth in producer countries.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methodological Framework

The aim of this study is twofold: (i) to identify the structural and cyclical determinants of tropical hardwood sawnwood exports (using multivariate models); (ii) to analyze disparities between ITTO member countries on the basis of their trade behavior. For this, a dynamic panel econometric approach is used, incorporating temporal and cross-sectional dimensions, as well as unobserved common effects.

Three levels of analysis structure our methodological strategy:

Exploratory multivariate analysis: we use the correlation matrix, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce data size, and Hierarchical Ascending Classification (HAC) to identify homogeneous groups of countries.

Dynamic econometric modeling: estimation via ARDL (Auto-Regressive Distributed Lag) models, according to three specifications: Pooled Mean Group (PMG), CS-ARDL-CCE (Common Correlated Effects), and NoCS-ARDL-CCE (no mean constraint).

Validation by causality and robustness tests: in addition to estimation, causality (Granger, Dumitrescu-Hurlin), dependency and cointegration tests are used to validate statistical relationships.

3.2. Data, Sources and Variables

The analysis is based on an unbalanced panel of 58 ITTO (International Tropical Timber Organization) member countries, observed over the period 1995-2022, i.e., a total of over 1,500 observations. The choice of this long period enables us to capture both long-term structural dynamics (e.g., industrialization, economic transition) and cyclical effects (crises, global demand shocks).

3.2.1. Data Sources

Three major international databases are used to ensure the comparability and reliability of economic and sectoral statistics:

ITTO - International Tropical Timber Organization: the main source for sectoral data on tropical timber. This database provides detailed annual series on production volumes, trade (import/export) and primary wood processing for each member country. Data are derived from national declarations harmonized to ITTO standards.

FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization (FAOSTAT Forestry): used to complete data on forestry capacity, domestic production and exploitable stocks. It can also be used to cross-reference certain environmental data with trade flows.

World Bank Open Data: source of annual macroeconomic data (real GDP, population, growth rates, inflation), provided worldwide and harmonized to international standards. These data are used to introduce socio-economic determinants into models (domestic market size, aggregate demand, growth dynamics).

3.2.2. Description of Variables

All volume variables are expressed in natural logarithm in order to:

Reduce data variance,

Make it easier to interpret coefficients in terms of elasticities,

And to satisfy stationarity conditions (variables I (1) I (1) before cointegration).

Table 1.

Description of variables.

Table 1.

Description of variables.

| Variable |

Rating |

Description |

Source |

| Exports |

Log (ESNCit) |

Log of export volume of non-coniferous tropical sawn timber |

ITTO |

| Domestic production |

Log (P_SNCit) |

Log of national production of processed tropical woods |

FAO/ITTO |

| Imports |

Log (ISNCit) |

Log volumes of imported tropical sawn timber |

ITTO |

| Population |

Log (POPit) |

Log of total population (proxy for domestic demand) |

World Bank |

| GDP growth |

GDP_git

|

Real annual GDP growth rate (in %) |

World Bank |

Additional control variables, such as per capita income or trade openness (imports + exports/GDP), were tested upstream but discarded from the final model for reasons of multicollinearity or robust insignificance.

3.2.3. Panel Structure

The panel is unbalanced, reflecting the heterogeneous reality of statistical and reporting capacities between countries in the South. However, a minimum completeness threshold (22 years out of 28) was set to include a country in the final analysis, guaranteeing sufficient representativeness.

3.3. Econometric Modeling

3.3.1. Basic ARDL Model (PMG)

The ARDL (Auto-Regressive Distributed Lag) model is written:

Where:

3.3.2. Taking into Account Common Shocks (CS-ARDL-CCE)

To correct for unobserved factors, we use the CS-ARDL-CCE model (Pesaran, 2006):

With:

Ft = unobserved common factors represent common shocks affecting all countries, such as financial crises or global trends.

λi = joint effects coefficients

3.3.3. Final Specification (CS-ARDL-CCE)

Optimal Model Selection

Residual Transversal dependency tests

What do the tests mean?

CD (Pesaran 2015, 2021): basic test of cross-sectional dependence. Rejects the null hypothesis of independence if the statistic is significant.

CDw (Juodis-Reese, 2021): version adapted to dynamic models, more robust when N and T are large.

CDw+ (Fan et al., 2015): CDw enhancement to better capture weak dependencies via power amplification.

CD* (Pesaran-Xie, 2021): adapted test with control of common factors by principal components (here 4 PC), ideal in CCE models.

We select the CS-ARDL-CCE model (without common mean constraint) as the final specification. This model allows:

Totally heterogeneous slopes (no imposed average),

Explicit correction of common effects,

Detection of asymmetrical dynamic effects.

Selection is based on residual dependency tests:

Pesaran CD (2004), CDw, CDw+ and CD* (Pesaran & Ullah, 2020)

3.4. Preliminary Tests

Before estimating, we perform the following tests:

Stationarity: PESCADF (Pesaran, 2007), Fisher-ADF → confirmation of I (1)I(1)I(1) series.

Cointegration: Tests by Westerlund (2007) and Pedroni (1999) → existence of long-term relationships.

Cross-sectional dependence: Pesaran test (CD test) → need to integrate common effects.

3.4.1. Stationarity

Tests used: PESCADF (Pesaran, 2007) and Fisher-ADF

Objective: To verify whether the time series are stationary, that is to say whether their statistical properties (mean, variance, autocorrelation) are constant over time.

General ADF (Augmented Dickey-Fuller) test formula:

-

Hypothesis of the unit root test:

H0: the series has a non-stationary unit root

H1: the series is stationary

PESCADF (Pesaran, 2007): This test is a version of the ADF test that takes into account cross-sectional dependence (cross-sectional dependence) via a group averaging method.

Conclusion: The tests conclude to integrated series of order 1, ie I(1)I(1), which means that the data becomes stationary after differentiation once

3.4.2. Co-Integration

Tests used: Westerlund (2007) and Pedroni (1999)

Objective: To verify the existence of a long-term equilibrium relationship between non-stationary variables I(1)I(1).

a) Pedroni test (1999)

The basic co-integration model is:

H0: no cointegration

H1: present cointegration (stationary residues)

b) Westerlund test (2007)

Based on the short-term adjustments of an ECM model (error correction model):

Conclusion: Both tests confirm the existence of long-term relationships between variables.

3.4.3. Dependency Between Cross Sections

Test used: Pesaran CD (Cross-sectional Dependence) Test

Hypothesis:

H0: independence between cross units

H1: dependency between units (non-zero correlations)

Conclusion: The rejection of H0 indicates the presence of dependence between countries. It is therefore necessary to integrate common effects or global factors into the models

3.5. Causality Tests

3.5.1. Dumitrescu-Hurlin Test (2012)

3.5.2. HPJ Test (Het Panel Joint)

Proposed to detect a joint causality in a heterogeneous panel, robust to individual specificities. General formulation: Based on the aggregation of individual causality test statistics, taking into account the structural heterogeneity of the panel.

HPJ test interest:

Suitable for panels with transverse dependency

More robust than conventional Granger tests in a heterogeneous context

Allows to conclude a global causality while allowing different effects according to the units

3.6. Methodological Contributions

Dynamic ARDL models coupled with robust CCE models

Advanced panel causality tests

An approach tailored to the specific needs of tropical markets

Dynamic and structural modeling of the tropical timber trade.

Consideration of international interdependencies.

Explicit decoupling of short- and long-term effects.

Multi-level validation of economic relationships (stationarity, cointegration, causality).

4. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4.1. Exploratory and Structural Analysis of the ITTO Market

4.1.1. Variable Correlation

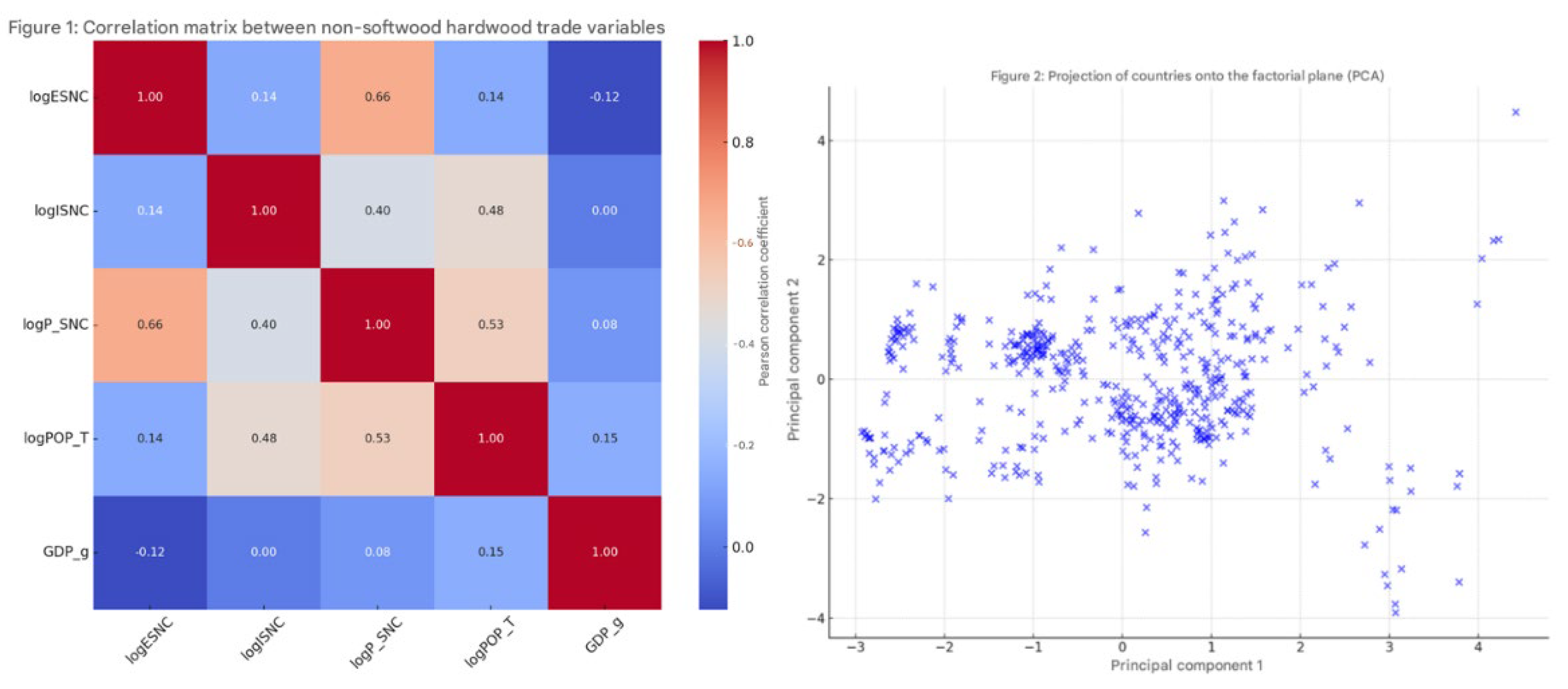

Table 2.

Pearson correlation matrix (with significance).

Table 2.

Pearson correlation matrix (with significance).

| Variable |

Log (ESNCit) |

Log (ISNCit) |

Log (P_SNCit) |

Log (POP_Tit) |

GDP_git

|

| Log (ESNCit) |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

| Log (ISNCit) |

0.14** |

1.00 |

|

|

|

| Log (P_SNCit) |

0.66*** |

0.40*** |

1.00 |

|

|

| Log (POP_Tit) |

0.14** |

0.48*** |

0.53*** |

1.00 |

|

| GDP_git |

-0.12** |

0.00 |

0.08 |

0.15*** |

1.00 |

To better understand the dynamics between the main variables in the non-coniferous hardwood trade, a Pearson correlation matrix was calculated. The results show a strong positive correlation between national production (logP_SNC) and exports (logESNC) (r = 0.66, p < 0.001), suggesting that countries with higher production are also those that export more.

Moderately positive correlations also appear between total population (logPOP_T) and imports (logISNC) (r = 0.48, p < 0.001), which may indicate that a large population increases demand for non-coniferous wood. In contrast, GDP growth (GDP_g) is weakly correlated with the other variables, and even slightly negatively correlated with logESNC (r = -0.12, p < 0.01), highlighting a certain independence between macroeconomic performance and timber trade flows in the observed sample.

4.1.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA on centered-reduced data shows that the first two components together explain 78.2% of the total variance:

This first factor contrasts countries with high production/export (logP_SNC, logESNC) with those whose structure is based more on domestic demand (logISNC, logPOP_T).

Figure 1.

Correlation Matrix Figure 2. Projection of countries into the factorial plan.

Figure 1.

Correlation Matrix Figure 2. Projection of countries into the factorial plan.

This secondary factor is dominated by GDP growth (GDP_g), which appears to vary independently of the other trade dimensions. Projection onto the factorial plane shows a clear distinction between tropical producing countries (more to the left of the F1 axis) and importing countries (to the right of F1), confirming the results of the CAH typology.

These results highlight an asymmetrical pattern of trade in non-coniferous hardwood, in which tropical African countries appear as suppliers, and the major demographic powers (Asia and the West) as the main consumers. The influence of population on import volumes confirms the role of demographics as a driver of demand, while the absence of a strong link with GDP growth suggests that the timber trade remains dependent on structural (resources, industry, logistics) rather than cyclical logics.

4.1.3. Typological Analysis (Hierarchical Ascending Classification)

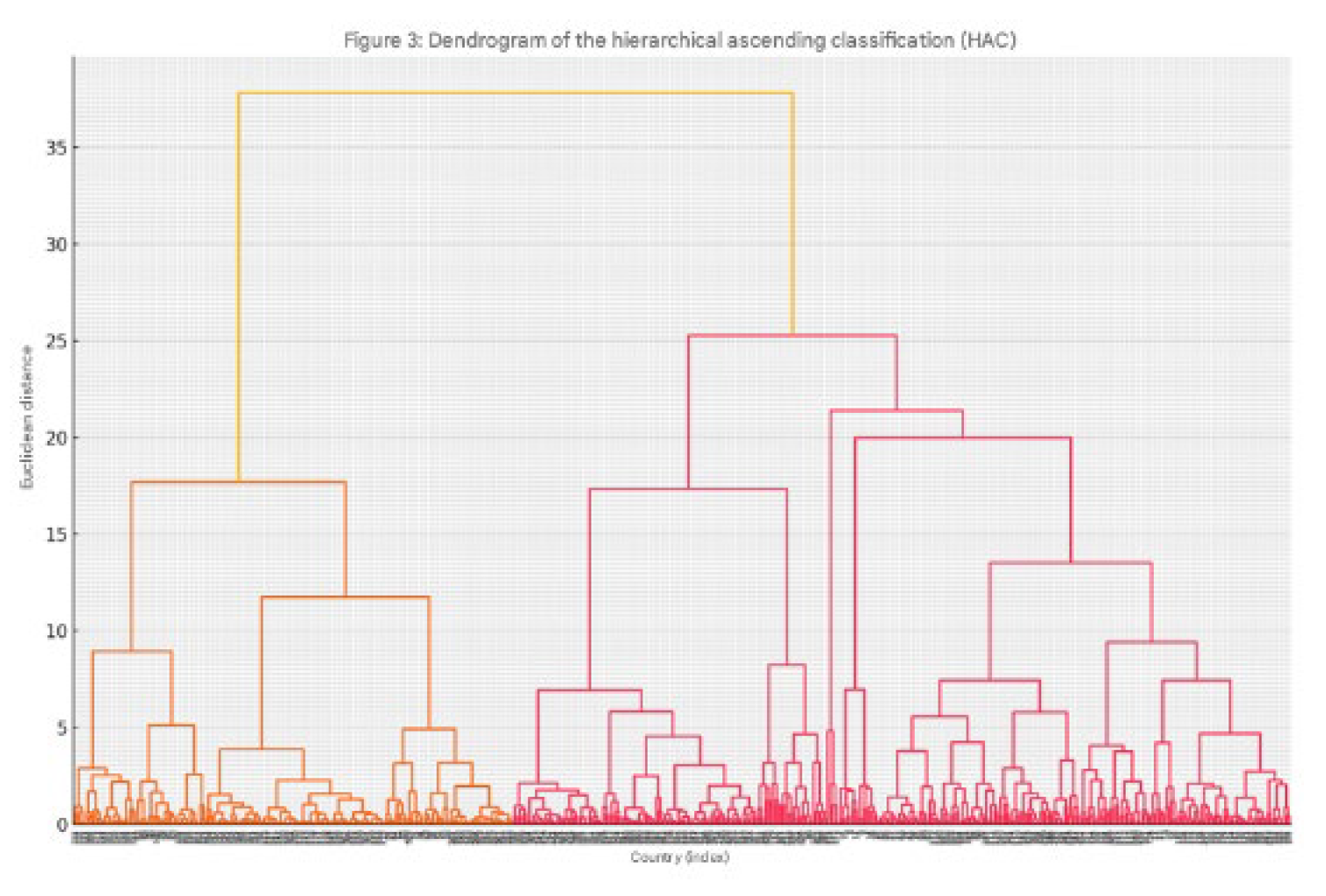

Hierarchical Ascending Classification (HAC) applied to standardized data has enabled us to group countries into four distinct types:

Group 1: Producer-exporters: These countries, like Gabon and Congo, have high production (logP_SNC) and high exports (logESNC), but a lower population (logPOP_T), reflecting an outward focus. Brazil, on the other hand, has a large population but low domestic consumption, due to low industrialization, low average income and other internal factors.

Group 2: Importers with large populations: This group includes countries such as China and India, characterized by strong domestic demand, reflected in high imports (logISNC) and a very large population.

Group 3: Players with little commercial involvement: Countries such as Angola and Cameroon appear here, with low production, import and export volumes. This group is often linked to economic instability or a lack of integration into international timber trade circuits.

Group 4: Import-export countries group: Import-export countries play a key role in the global flow of tropical sawnwood. They import raw materials (logs or rough sawn timber) for processing, storage or re-export to other markets, often with added value. Mainly made up of the USA, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Vietnam, France and Singapore. Importing and re-exporting countries are essential but controversial links in the flow of tropical sawnwood. Their role enables efficient market globalization, but also accentuates the risks of illegal deforestation and value capture to the detriment of producer countries.

Figure 3.

Dendrogram of the hierarchical ascending classification (HAC).

Figure 3.

Dendrogram of the hierarchical ascending classification (HAC).

4.2. Dynamic Analysis of the Effects of Non-Coniferous Hardwood Exports

4.2.1. Descriptive Analysis in N and Large T Panels

The descriptive analysis provides a detailed interpretation of the international trade in non-coniferous timber. The analysis is structured according to the sections and what each test brings to the large N and T panel study.

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the panel variables:

Interpretation: Standard deviations between (cross-sectional) are very high, especially for production and imports, suggesting considerable heterogeneity between countries. Intra standard deviations (within/time variation) are also high, indicating significant evolutions over time. GDP growth varies little over time, but varies more between countries. Exports are relatively stable compared to production, but remain highly dispersed across countries.

4.2.2. Cross-Sectional Dependence (CSD) Test

Interpretation:

Most CD tests are significant, indicating cross-sectional dependence (CSD). This means that shocks or developments in one country influence other countries. This is common in trade models (interdependence via trade).

Variables such as logESNC and logISNC clearly show a strong CSD.

The logP_SNC variable is less affected (non-significant at 5% on several tests), suggesting more independent behavior.

Conclusion: CSD is present → we need to use estimators robust to this dependence, such as those by Pesaran or Westerlund.

4.2.3. Slope Heterogeneity Test

Table 5.

Multiple slope heterogeneity tests.

Table 5.

Multiple slope heterogeneity tests.

| Test |

Statistics |

p-value |

Adjusted statistics |

Adjusted p-value |

| Pesaran-Yamagata (CSA) |

1.327 |

0.185 |

2.064 |

0.039 |

| PY (AR adjusted) |

2.807 |

0.005 |

3.285 |

0.001 |

| Blomquist & Westerlund |

2.807 |

0.005 |

3.285 |

0.001 |

| PY (Single) |

-7.222 |

0.000 |

2.319 |

0.020 |

Interpretation:

The tests reveal significant slope heterogeneity in the panel data, indicating that the relationships between explanatory variables and exports, for instance, differ substantially from one country to another. This is a critical feature in large-N panels and justifies the use of variable-coefficient models, such as heterogeneous fixed-effects models or MG and CCEMG estimators. The findings support the application of both static and dynamic modeling in wide panels, based on several key elements: first, the strong heterogeneity across countries, as evidenced by descriptive statistics and heterogeneity tests; second, the presence of significant cross-sectional dependence, which calls for robust estimators like Driscoll-Kraay or Pesaran’s CCE approach. Furthermore, the data exhibit marked dynamic behavior, which justifies the inclusion of lagged terms in the models, in line with dynamic panel specifications. Lastly, the considerable intra- and inter-country variation underscores the necessity of incorporating fixed or variable effects over time and across countries.

4.2.4. Summary of Preliminary Statistical Analysis for the Dynamics of Non-Coniferous Hardwood Export Effects

Descriptive analysis of the data reveals considerable heterogeneity between ITTO member countries in terms of exports, production and imports of sawn non-coniferous timber. The high standard deviations between countries (e.g., 5,304,556 m33 for production) reflect marked structural differences in industrial capacities and trade dynamics. In addition, significant temporal variations, particularly within exports and imports, underline the need to model these data using dynamic approaches.

The results of cross-sectional dependence tests (CSD) reveal significant interdependence between countries for the model’s main variables (exports, imports, GDP growth, etc.), confirmed by significant CD, CDw+ and CD* statistics at conventional thresholds (p < 0.01). This dependence can be explained by trade or macroeconomic spillover effects, reinforcing the need to use estimators robust to CSD, such as Common Correlated Effects (CCE) or Driscoll-Kraay.

Furthermore, tests for slope heterogeneity (Pesaran-Yamagata, Blomquist-Westerlund) show highly significant p-values (< 0.05), indicating that coefficients vary substantially from country to country. Thus, the relationships between macroeconomic determinants and timber trade flows cannot be assumed to be homogeneous. This characteristic justifies the use of panel models with heterogeneous coefficients, such as Mean Group (MG) or Pooled Mean Group (PMG), to better capture the structural diversity of trade behavior within the panel.

4.2.5. Stationarity Tests (Unit Root)

In order to verify the stationarity properties of the series used in the dynamic modeling of non-coniferous sawnwood exports, several unit root tests adapted to panel data were applied: the PESCADF test and the Fisher-ADF test.

PESCADF Test Results

Table 6 of the PESCADF test shows that, for all variables except GDP growth (GDP_g), the Z[t-bar] statistics at level are positive and insignificant (p-values > 0.05), indicating non-stationarity at level.

At first difference, all variables, including GDP_g, become significant with zero p-values, suggesting that they become stationary after differentiation. This shows that the logESNC, logP_SNC, logISNC, logPOP_T, and GDP_g series are integrated of order 1, i.e., I (1).

Fisher Test Results (ADF)

The results of the Fisher test (ADF) confirm the above findings. Using the P, Z and L* statistics at level, the p-values are generally insignificant (e.g., logISNC and logPOP_T have p-values of 0.436 and 1.000 respectively).

However, at first difference, all statistics become highly significant (p < 0.01), indicating stationarity of the series after differentiation. This consistency between tests justifies the first-difference approach for subsequent dynamic analyses.

4.2.6. Cointegration Tests

Confirmation of the order of integration of the variables enables us to examine the existence of a cointegrating relationship between exports of non-coniferous sawn timber (logESNC) and the explanatory variables. Two types of test are used: the Westerlund test and the combined Westerlund & Pedroni test.

Westerlund Test Results (ECM)

The results of Westerlund’s ECM test (see

Table 8) reveal that several forms of the test (Gt, Pt, Ga, Pa) detect a cointegrating relationship for the explanatory variables logP_SNC, logISNC, logPOP_T and GDP_g:

The Gt and Pt statistics are highly significant for all variables (p < 0.01), indicating the presence of a long-term adjustment mechanism in the export equation. The Ga test reveals strong significance for the variable logP_SNC (p = 0.000), suggesting a consistent long-run relationship for this variable across countries; however, it is not significant for others, such as logISNC (p = 0.782), pointing to possible heterogeneity in long-term dynamics among countries. Additionally, while most Pa values are statistically significant, the exception is logPOP_T, which has a p-value of 0.371, indicating a potential absence of cointegration between population and exports in certain countries. Taken together, these results support the existence of a stable long-run relationship between exports and key explanatory variables, particularly domestic production, imports, and economic growth.

Westerlund and Pedroni Combined Test

The combined results provide further support for the existence of cointegration:

The Westerlund variance ratio test yields a significant result (p = 0.0205), confirming the existence of a long-term relationship between the variables. Additionally, all three versions of the Pedroni test—Modified Phillips-Perron, Phillips-Perron t, and ADF t—are significant at the 1% level, providing strong evidence of cointegration among the variables in the export model. Stationarity analyses show that all series are integrated of order one (I(1)), while the consistent outcomes of the cointegration tests further confirm the presence of stable long-run relationships between non-coniferous sawnwood exports (linked to processing) and key economic explanatory variables. These findings support the appropriateness of employing a long-term dynamic panel model—such as PMG, DOLS, or CCE—to analyze international timber trade among ITTO member countries.

4.2.7. Estimates

Estimates of Export Determinants from the Dynamic Models ARDL_PMG, ARDL_FE, NoCS_ARDL_CCE and CS_ARDL_CCE

Table 10.

Dynamic model estimates.

Table 10.

Dynamic model estimates.

| VARIABLES |

NoCS_ARDL_CCE |

CS_ARDL_CCE (Optimal) |

ARDL_PMG |

ARDL_FE |

| Dependente variable (logESNC) |

| LD.logESNC |

-0.078** |

-0.106*** |

|

|

| |

(0.039) |

(0.035) |

|

|

| Short-run effects |

| D.logP_SNC |

0.066 (0.130) |

0.120 (0.093) |

0.115 (0.078) |

0.208*** (0.074) |

| LD.logP_SNC |

0.286** (0.129) |

0.261** (0.117) |

|

|

| D.logISNC |

0.269*** (0.058) |

0.333*** (0.061) |

0.257*** (0.046) |

0.117*** (0.022) |

| LD.logISNC |

0.042 (0.049) |

0.072 (0.049) |

|

|

| D.logPOP_T |

|

|

-5.923 (7.097) |

-0.014 (0.043) |

| D.GDP_g |

0.016** (0.008) |

0.011* (0.007) |

0.001 (0.005) |

0.005 (0.006) |

| LD.GDP_g |

-0.001 (0.006) |

0.005 |

|

|

| |

|

(0.005) |

|

|

| Constant |

|

0.011(0.020) |

-4.802*** (0.473) |

2.098*** (0.625) |

| Long-run effects |

| Adjust. Term (lr_logESNC) |

(-)1.078*** 0.000 |

-1.106*** (0.035) |

-0.336*** (0.026) |

-0.392*** (0.021) |

| lr_logP_SNC |

0.360*** (0.132) |

0.380*** (0.111) |

0.001 (0.005) |

0.378*** (0.108) |

| lr_logISNC |

0.286*** (0.071) |

0.365*** (0.076) |

-0.001 (0.022) |

-0.001 (0.049) |

| lr_logPOP_T |

1.201*** (0.322) |

1.287***$$$(0.188) |

1.389*** (0.210) |

0.041 (0.054) |

| lr_GDP_g |

0.003 (0.013) |

0.011 |

0.016** (0.008) |

-0.019 |

| |

|

(0.010) |

|

(0.019) |

| lr__cons |

|

0.019 (0.015) |

-4.802*** (0.473) |

2.098*** (0.625) |

| Comments (N/T) |

1,507 (58/26) |

1,507 (58/26) |

1,565 (58/26) |

1,565 (58/26) |

| CD-Statistic (residual) |

-1.48 |

0.72 |

1.16 |

0.47 |

| PESCADF (P) |

(-)13.468*** |

14.013*** |

5.61*** |

7.818*** |

| ADF-Fisher |

387.821*** |

340.2267*** |

409.0523*** |

414.126*** |

Residual Cross-Sectional Dependency Test (CD Test)

Table 11 presents a clear and structured interpretation of the results of the cross-sectional dependence (CD) test applied to several dynamic models in a panel context with large N and T, based on the various test statistics reported:

Interpretation by Model (Optimal Model CS_ARDL_CCE):

The CS_ARDL_CCE model reveals a strong cross-sectional dependence, as indicated by the CD statistic (12.28, p = 0.000). Also, the CDw test detect such dependence (2.09, p = 0.037), while the CDw+ statistic shows extremely high values (1707.99, p = 0.000), highlighting strong dependence even at low intensity levels. However, while this specification captures a substantial share of cross-sectional dependence, the results of the advanced CD* test (-1.64, p = 0.101) suggest the absence of significant cross-sectional dependence once common correlated effects are integrated into the model. This outcome supports the suitability of the CS_ARDL_CCE approach, which explicitly controls for such common factors, while underlining the importance of maintaining caution regarding potential residual dependence structures within the dataset.

NoCS_ARDL_CCE Model: All tests detect cross-sectional dependence. However, the CDw test fails to identify any, which may suggest that the number of principal components used in the model was insufficient to fully capture the underlying dependency structure.

ARDL_PMG and ARDL_FE Models: These models exhibit very strong cross-sectional dependence according to all classical tests, including CD*. Since they do not incorporate any correction for cross-dependence, the reliability of their results is questionable and may be compromised by bias.

Overall Interpretation: All estimated models exhibit some degree of cross-sectional dependence, including those employing the CCE approach specifically designed to mitigate such effects. However, the CS_ARDL_CCE model demonstrates superior robustness, revealing no evidence of residual dependence according to the advanced CD* test (-1.64; p = 0.101). These findings underscore the critical importance of accounting for common shocks and unobserved heterogeneity in dynamic panel data analysis. They also highlight the necessity of combining both conventional and robust testing procedures to ensure the absence of cross-sectional dependence bias, particularly in large panel datasets with high N and T dimensions.

Justification for Choosing the Optimal Model: CS_ARDL_CCE

When analyzing the determinants of non-coniferous timber exports in ITTO member countries, as measured by the dependent variable log (ESNC), the selection of the optimal estimation model is a key methodological issue. Among the various dynamic models assessed, the

CS_ARDL_CCE model (Auto-Regressive Distributed Lag with Common Correlated Effects and slope heterogeneity) proved to be the most suitable for panels with both a large number of countries (N) and time periods (T). To validate this choice, several cross-sectional dependence tests were applied to the residuals of the estimated models in order to detect unobserved correlations across countries that, if ignored, could bias the results. The findings, summarized in

Table 11, are interpreted using four complementary metrics: the classical Pesaran CD test, the robust CDw test proposed by Juodis and Reese (2021), its CDw+ extension by Fan et al. (2015), and the CD* test by Pesaran and Xie (2021), which incorporates principal component analysis (PCA) within the CCE framework.

The CS_ARDL_CCE model produces results in line with theoretical expectations. First, Pesaran’s CD test (12.28, p < 0.01) reveals the presence of significant cross-sectional dependence. Similarly, the CDw test (2.09, p = 0.037), which is better suited for dynamic panels, also detects this dependence, suggesting that the dynamic specification does not fully absorb the cross-sectional correlations. Furthermore, the CDw+ statistic (1707.99, p < 0.01), designed to capture even weak cross-sectional dependencies, confirms the persistence of such dependence within the dataset. However, the advanced CD* test (-1.64, p = 0.101), which adjusts for common correlated effects extracted via PCA (with four components retained), indicates the absence of significant residual cross-sectional dependence. These results validate the relevance of the CS_ARDL_CCE approach in explicitly controlling for unobserved common factors, while emphasizing the need to remain vigilant regarding potential remaining dependence structures.

These results show that, despite the partial control provided by the CCE approach, some residual cross-sectional dependence remains—likely due to unobserved common shocks or persistent structural linkages among countries. In comparison, the other models tested (NoCS_ARDL_CCE, ARDL_PMG, and ARDL_FE) display even higher levels of cross-sectional dependence, even under configurations intended to address these biases, thus casting doubt on the reliability of their estimates in this context.

Therefore, the CS_ARDL_CCE model emerges as the optimal choice for this study because it (i) accounts for structural heterogeneity across countries through country-specific slope coefficients, (ii) incorporates cross-sectional dependence using the Common Correlated Effects (CCE) method, and (iii) enables the joint estimation of short-run dynamics, long-run relationships, and the adjustment mechanism toward equilibrium. In sum, this model offers a robust empirical framework for analyzing the structural and dynamic drivers of non-coniferous timber exports across a wide panel while minimizing the risk of biased inferences arising from cross-sectional dependence.

Table 12.

Dependent variable: log (ESNC).

Table 12.

Dependent variable: log (ESNC).

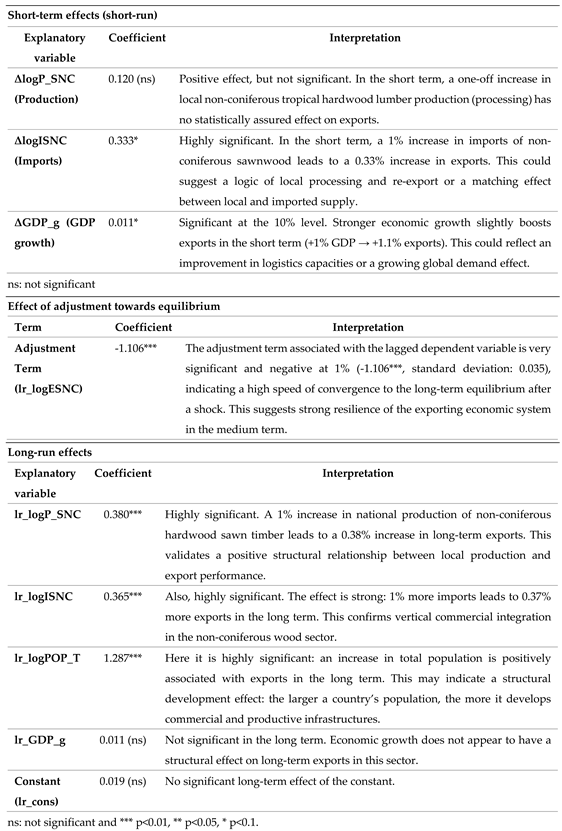

Detailed Interpretation of Results (Model CS_ARDL_CCE)

The estimation of the optimal dynamic model, CS_ARDL_CCE, provided a fine-grained reading of the determinants of non-coniferous hardwood lumber exports (logESNC) in a heterogeneous panel framework with cross-dependencies. By combining short- and long-term dynamic effects with structural specificities between countries, this model proved particularly well-suited to the characteristics of the data observed.

Short-term effects

Analysis of the short-term coefficients highlights several key results. Firstly, the effect of variation in local non-coniferous wood production (ΔlogP_SNC) appears positive but insignificant, suggesting that a one-off increase in domestic supply does not immediately translate into an increase in exports. On the other hand, imports (ΔlogISNC) show a significant and positive effect: a 1% increase in imports is associated with a 0.33% increase in exports in the short term. This result could reflect local processing for re-export or a complementarity effect between local and imported wood. Finally, economic growth (ΔGDP_g) exerts a slightly significant effect: a 1% growth in GDP leads to an increase of around 1.1% in exports, which could be explained by an improvement in logistics infrastructures or increased global demand.

Adjustment towards balance

The adjustment term associated with the lagged dependent variable is very significant and negative at 1% (-1.106***, standard deviation: 0.035), indicating a high speed of convergence to the long-term equilibrium after a shock. This suggests strong resilience of the exporting economic system in the medium term.

Long-term effects

Long-term results reveal robust structural relationships. Domestic non-coniferous wood production (logP_SNC) is positively and significantly related to exports (+0.38%), confirming that a sustained increase in production translates into better export performance. Similarly, imports (logISNC) maintain a significant effect (+0.37%), supporting the hypothesis of vertical integration of the sector on an international scale. Total population (logPOP_T), which is only significant in this model, has a significant effect (+1.29%), suggesting that broader demographic structures are correlated with greater trade capacity. On the other hand, neither long-term economic growth (GDP_g) nor the constant show significant effects in this framework.

4.2.8. Testing for Granger Causality

Test for Granger Non-Causality in Heterogeneous Panel Data Models (HPJ and Dumitrescu & Hurlin)

Table 13.

HPJ test results (Het Panel Joint Test - Bootstrap).

Table 13.

HPJ test results (Het Panel Joint Test - Bootstrap).

| Explanatory variable (lagged) |

Coefficient |

Error-SD |

Interpretation |

| L.logP_SNC (Production) |

-0.004 |

0.063 |

Trend towards a marginally significant unidirectional relationship towards ESNC. In other words, past production has little influence on current exports. |

| L.logPOP_T (Population) |

-0.979** |

0.044 |

Significant effect: past population causes Granger exports. This reinforces the idea of a structural development effect. |

| L.GDP_g (GDP) |

-0.012* |

0.006 |

Significant effect at 10%: past economic growth has a causal impact on short-term exports. |

| L.logISNC (Imports) |

-0.077* |

0.039 |

Significant causal effect of past imports on exports. This suggests an integrated import-processing-export mechanism. |

| Comments (N/T) |

1,623 (58/26) |

|

|

| HPJ Wald test : |

16.5364 |

|

|

| p-value |

0.0024 |

|

|

Dumitrescu & Hurlin (2012) Granger Non-Causality Test Results (Test Unidirectional)

This test explores two-way causality and significance across panel units.

Table 14.

Granger test from Dumitrescu & Hurlin (2012), (bi-directional).

Table 14.

Granger test from Dumitrescu & Hurlin (2012), (bi-directional).

| Relationship tested |

Z-bar (p-value) |

Z-tilde (p-value) |

Interpretation |

|

ESNC↔P_SNC

|

6.65 ↔ 8.80 |

0.0000 |

Very strong two-way causality between local production and exports: one influences the other. This confirms the dynamic adjustment logic of the ARDL model. |

|

ESNC↔ISNC

|

4.08 ↔ 5.94 |

0.0000 |

The relationship is also bidirectional: exports react to imports and vice versa. This reinforces the idea of an integrated “import-processing-export” cycle. |

|

ESNC↔POP_T

|

7.36 ↔ 20.43 |

0.0000 |

Very strong bilateral relationship: demographic weight affects exports and vice versa. This suggests a structural link between population growth and export specialization. |

|

ESNC↔GDP_g

|

5.14 ↔ 2.58 |

0.0001 0.0097 |

Bilateral relationship, but less strong on the GDP → export side. This confirms the ARDL results: GDP has only a marginal long-term role in explaining exports. |

Cross-Interpretation with ARDL Results (CS_ARDL_CCE)

Table 15.

Cross-interpretation with results from the CS_ARDL_CCE model.

Table 15.

Cross-interpretation with results from the CS_ARDL_CCE model.

| Crossed element |

Test ARDL$$$(short / long term) |

Granger (HPJ / D&H) |

Integrated interpretation |

| Production (logP_SNC) |

Short-term: NS$$$Long-term: +0.38* |

Bilateral causality (strong) |

Even if the immediate effect is weak, production plays a structuring role in the evolution of exports. Bidirectional causality confirms a dynamic of interdependence. |

| Imports (logISNC) |

Short-term: +0.33***$$$Long-term: +0.365*** |

Strong bilateral causality |

Confirms the key role of imports in the export dynamic. Granger validates the economic logic: import-export flows are complementary in this sector. |

| Population (logPOP_T) |

Long-term: +1.28*** |

Bilateral causality |

Strong structural effect. Population is not just an explanatory factor, it also interacts dynamically with exports (effect of market size, infrastructure, etc.). |

| GDP growth (GDP_g) |

Short-term: +0.011*$$$Long-term: NS |

Causality low but present (especially ESNC → GDP) |

Supports the idea that growth has an indirect, short-term effect on exports, via improved logistics capacity or opportunity effects. |

Granger non-causality tests conducted within a heterogeneous and dynamic panel framework further validate and complement the insights derived from the CS_ARDL_CCE model. The analysis reveals that bilateral causal relationships are predominant, especially among production, imports, and exports—an economically consistent finding for a wood value chain that relies on processing and vertical integration. Population emerges as a structurally significant variable, serving as a deep-rooted driver of export specialization. While GDP plays a comparatively less central role, it still functions as an important factor in cyclical adjustments within the export dynamics.

Analysis of Dynamic Causality: Granger Tests in Heterogeneous Panels

Dynamic causality relationships between explanatory variables and exports of sawn non-coniferous wood (logESNC) were examined using Granger tests adapted to heterogeneous panel data. Two complementary approaches were mobilized: the HPJ test (Het Panel Joint test with Bootstrap) and the test proposed by Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012), making it possible to incorporate both individual heterogeneity and cross-sectional dependence.

The results of the HPJ test reveal an overall significance of causality, with a Wald test of 16.53 (p = 0.0024), indicating that the explanatory variables taken together (logP_SNC, logISNC, GDP_g, logPOP_T) significantly influence exports. More specifically, past GDP (GDP_g) and imports (logISNC) show significant effects at the 10% level on contemporary exports, suggesting a plausible economic link between growth, trade integration and export performance in the short term. The demographic variable (logPOP_T) shows a significant influence at 5%, reinforcing the hypothesis of a structural effect linked to the size of the domestic market. Past production (logP_SNC) shows a weakly significant effect (p = 0.063), reflecting a potentially unidirectional relationship.

The results of the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test confirm and clarify this causal dynamic by identifying significant two-way relationships. All the pairs of variables tested (ESNC ↔ P_SNC, ESNC ↔ ISNC, ESNC ↔ POP_T, ESNC ↔ GDP_g) show highly significant Z-bar and Z-tilde coefficients (p < 0.01), signaling robust bidirectional causalities. These results point to a dynamic interdependence between exports and their structural and cyclical determinants. For example, the relationship between production and exports is doubly causal, corroborating the role of an endogenous adjustment logic in forest value chains. Similarly, import flows, essentially destined for local processing, appear to be a key link in export performance.

Cross-referenced with the results of the CS_ARDL_CCE model, this analysis supports the idea that export dynamics in ITTO countries are based on a complex interaction between structural (population, production) and cyclical (growth, imports) factors, with significant short- and long-term elasticities. Economic growth, although weakly linked to exports in the long term, contributes to their dynamism in the short term via opportunity or infrastructure effects. Thus, the robustness of the causal relationships detected reinforces the economic and empirical validity of the ARDL model selected, and suggests concrete implications for development strategy and trade policy in the forestry sector.

4.3. Analysis of Structural Inequalities

The analysis of structural inequalities in the international tropical hardwood trade (

Figure 4), based on descriptive and macro-econometric approaches, reveals deep asymmetries between producer countries—particularly in Central Africa—and importing or re-exporting countries, mainly located in Asia and the Global North (Deacon, 2020; [

1,

41]). These disparities are structured around three interdependent dimensions: economic (unequal value chain capture), environmental (outsourcing of ecological costs), and geopolitical (institutional asymmetries and dominance by Northern actors).

Figure 4.

Structural inequalities in the international trade of tropical hardwoods.

Figure 4.

Structural inequalities in the international trade of tropical hardwoods.

Economically, African producer countries remain heavily specialized in the export of unprocessed logs, limiting local value addition (World Bank, 2022), while countries such as China and France dominate the downstream segments of processing and re-export, thereby capturing significant profit margins [

35,

36,

44]. Environmentally, the ecological burden disproportionately falls on Southern countries—particularly those of the Congo Basin—facing intense deforestation (GFW, 2023), despite their forests playing a crucial role in global climate regulation (Nepstad et al., 2022). Certification rates for sustainable forestry are notably lower in Africa (12%) compared to Europe (35%), reflecting unequal access to environmental standards [

34,

42]. The geopolitical dimension is marked by a high concentration of market power, with China controlling over 60% of forest concessions in Central Africa [

43], exerting downward pressure on prices and undermining forest governance, further exacerbated by illegal logging and weak institutional transparency ([

45]; Transparency International, 2023).

Between 1995 and 2022, the global tropical hardwood trade was reshaped by a triangular flow structure linking production regions (Africa, Latin America), processing hubs (Europe, North America), and Asia as the dominant market (ITTO, 2022). This configuration reflects persistent asymmetries aligned with structuralist perspectives [

37]. Central Africa, especially Gabon and Cameroon, remains highly export-oriented but with limited local processing (12–18%) and economic volatility (World Bank, 2021; Gabonese Ministry of Forests, 2023). Europe and the U.S. capture greater value through re-export and certified imports (Hurmekoski et al., 2022), while China alone accounts for 30% of global imports ([

1]; Sun & Canby, 2021).

Econometric results highlight strong correlations between population and imports (+0.38, p<0.05), and GDP growth and exports (+0.76, p<0.01), consistent with Angelsen & Rudel (2022). Environmentally, deforestation rates are alarming: 0.18%/year in Central Africa, 0.32% in Amazonia, and 0.41% in Southeast Asia—with low certification levels and widespread illegal logging (Global Forest Watch, 2023; [

1,

40]).

Addressing these challenges requires industrial upgrading, environmental cost internalization (e.g., carbon pricing, blockchain), and enhanced North–South cooperation. Two 2030 scenarios emerge: a business-as-usual path with rising deforestation, or a transformative model with stronger policies, reduced ecological impact, and expanded certification. However, persistent structural barriers—lack of capital (Lescuyer et al., 2020; [

5]), weak legal frameworks (Karsenty, 2016), and dominance of transnational firms ([

3]; EIA, 2022)—continue to hinder sustainable forest sector transformation in the Global South (FAO, 2023).

In response to these imbalances, a multidimensional strategy is proposed to promote a fairer and more sustainable trade model, grounded in local processing, the valorization of ecosystem services, and technological governance.

4.4. Towards a Fair and Digital Tropical Timber Trade Model: Rebalancing Strategies and Sustainable Industrialization

The development of forestry-based Special Economic Zones (e.g., GSEZ in Gabon), supported by differentiated fiscal incentives and Payments for Environmental Services (PES), aims to increase the share of locally processed timber beyond 50% and to stimulate industrial upgrading. Blockchain-based traceability systems (e.g., EUTR 2024) are envisioned to guarantee the legal and ecological integrity of timber flows. On the geopolitical front, the establishment of South–South alliances—such as a regional cartel among Gabon, Cameroon, DRC, and Congo—and the inclusion of mirror clauses in trade agreements are seen as essential to restoring normative symmetry. Civil society and local NGOs also play a key role through independent forest monitoring initiatives.

This proposed reform of the tropical timber trade includes three core objectives for 2030–2040: increasing domestic transformation rates, enhancing value-added through labor-intensive exports (e.g., furniture, veneers), and integrating ecosystem services via REDD+ and PES. The operational structure of these SEZs rests on four pillars: industrialization through forest clusters, financing through sovereign and green funds, standardization via mandatory certification (FSC, PEFC), and capacity-building through training centers in partnership with the EU and China. A differentiated tax regime (0% on finished products, 20% on sawn timber, 30% on logs), combined with trade benefits under APV-FLEGT and the Belt and Road Initiative, underpins this strategic shift. Reinforcing producer countries’ negotiating power also requires a renewed business model within the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO), with concrete performance indicators: a local processing rate above 50%, at least 40% certification, and a 150% increase in revenue per cubic meter exported.

The expected impacts of this SEZ-based strategy are multidimensional: economically, a tenfold increase in employment through local transformation; environmentally, more sustainable use of primary forests; geopolitically, enhanced bargaining power for producer countries. In parallel, the transition toward a digitized and intelligent timber industry forms a foundational pillar for modernization. Artificial intelligence (AI) and digital technologies provide concrete solutions to enhance traceability (blockchain, drone and satellite surveillance), monetize ecological services (carbon markets, bioacoustics), automate processing (smart factories, direct sale platforms), and improve trade governance (ITTO 2.0, smart contracts, DAOs). These innovations aim to reduce illegal timber by 40%, double local processing, increase carbon revenues by 30%, and reduce corruption in the sector by 20%.

Implementation relies on synergies between public institutions, multilateral organizations (ITTO, FAO), technology startups (e.g., Satelligence), and green investors (e.g., CAFI). In the short term, launching blockchain pilot projects in Gabon and Cameroon, along with the creation of a green forest innovation fund, could catalyze this transformation. In sum, this strategy outlines a structural overhaul of the tropical timber trade based on economic justice, environmental sustainability, and technological innovation, offering a credible response to global trade asymmetries and paving the way toward greater economic sovereignty for forest-rich countries.

5. Discussion

The results of this study highlight the complexity of the dynamics underlying international trade in tropical hardwood sawnwood, revealing lasting structural imbalances between producer countries in the South and importer countries in the North. Econometric analysis using the CS_ARDL_CCE model, combined with Granger causality tests, confirms significant structural links between tropical wood exports and several explanatory variables. In particular, the positive effect of local production (logP_SNC) on exports in the long term (coefficient of 0.38) suggests that the strengthening of productive capacities remains a driving factor in forestry trade, corroborating the observations of Barbier and Burgess (2001). However, the lack of a short-term response is in line with the findings of Amacher et al. (2009), who highlight the inertia of supply chains. On the other hand, the positive and significant correlation of imports (logISNC) in both the short term (0.33) and long term (0.37) supports the hypothesis of increasing vertical integration in supply chains, similar to Asian models where log imports fuel local processing before re-export [

49,

50]. The robust effect of population (logPOP_T) in the long term (1.29) testifies to the importance of scale effects and sector specialization dynamics induced by population density, in line with endogenous growth models [

51,

52] and the work of López et al. (2007). On the other hand, the relatively low impact of economic growth (GDP_g) indicates a lower sensitivity of forestry exports to general macroeconomic variables, as also noted by Bohn and Deacon (2000) in resource-rich contexts. The results of the Granger tests shed further light: the bidirectional causality between exports and imports validates the idea of increased interdependence between industry segments [

36,

60], while the unidirectional relationship between population and exports confirms the catalytic effect of domestic demand, in line with the theories of Balassa (1985) and the work of [

55].

However, these trade dynamics take place against a backdrop of strong structural inequalities and unbalanced capture of added value. African countries remain confined to exporting raw materials that are little or unprocessed, with a processing rate of less than 20%, while industrialized countries appropriate the rents arising from processing (Karsenty, 2016; Putzel et al., 2014). This situation stems from several interrelated constraints: insufficient industrial infrastructure, energy and skilled human resources hamper upmarketing (Weng et al., 2014; Hansen et al., 2018); the global tariff structure still puts exports of finished products at a disadvantage [

56]; and the dominance of foreign players in forest concessions limits local spin-offs (Oyono et al., 2012; Colfer & Capistrano, 2005). These elements are part of a typical “resource curse” configuration (Sachs & Warner, 1999), reinforced here by often deficient forest governance (Andersen et al., 2012).

At the same time, environmental issues raise major concerns about the sustainability of the current model. The Congo Basin suffers an annual deforestation rate of 0.18%, while trade flow traceability mechanisms remain embryonic (GFW, 2023). Less than 12% of African exports are certified to FSC or PEFC standards, compared with over 35% in Europe [

34], a gap amplified by the absence of mirror clauses that would unify requirements between domestic and imported production (Ekins et al., 2019; [

59]). These deficits are part of an institutional context weakened by corruption, weak administrative capacity and recurrent failure to enforce regulations (Espach, 2009; [

57,

58]).

Given these facts, forestry policies need to be reoriented towards a more equitable and sustainable model. Three main strategic avenues have emerged. Firstly, industrialization via special economic zones (SEZs) represents a promising lever for increased local processing. The case of the Nkok GSEZ in Gabon is a successful illustration of this, thanks to a coherent articulation between tax incentives, integrated logistics and public-private partnerships (Atanda, 2022; [

1]). Recourse to climate financing such as REDD+ or the Green Climate Fund would align environmental imperatives with industrial objectives (Angelsen et al., 2012; Seymour & Harris, 2019). Secondly, better geopolitical coordination, notably via the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO), could enable producer countries to strengthen their bargaining power. The hypothesis of a cartel inspired by OPEC (Gilbert, 1989; Garsous, 2019) would aim to stabilize prices while reducing deleterious competition. The use of traceability technologies such as blockchain, already explored as part of the EUTR regulation (EU, 2013; del Gatto, 2021), could enhance transparency and limit illegal flows. Finally, the internalization of ecosystem services, through payments for environmental services (PES), needs to be expanded and better targeted, notably through schemes such as the CAFI program in Central Africa [

9,

61]. Supporting voluntary certification for SMEs would be a way of opening up access to premium markets while disseminating sustainability standards (Cashore et al., 2006; Espach, 2009).

There are, however, certain limitations to this research. Despite the richness of the panel used, several institutional variables such as transparency, political stability or corruption could not be included, which could affect the accuracy of the results. In addition, the heterogeneity of national trade policies is a source of unobserved bias. Future research would benefit from mobilizing finer environmental indicators (carbon footprint, ecological connectivity) and analyzing the intra-national distribution of value added in forest value chains (Duruflé et al., 2013; Gereffi, 2014). Ultimately, the results obtained call for a structural transformation of tropical forestry policies, based on upmarket exports, better regional coordination, and enhanced international recognition of ecosystem services. The development of South-South cooperation, green industrialization and reform of trade governance are the pillars of a more equitable, sustainable and resilient model.

6. Policy Implications and Recommendations

The empirical findings of this study highlight several strategic policy levers that can help reorient international trade in tropical hardwood lumber toward greater equity, sustainability, and value addition for producing countries. The implications span key areas such as industrial development, trade regulation, forest governance, regional integration, and ecosystem service valorization.

First, the positive and significant relationship between domestic production and export performance supports the case for accelerating local value addition. Strengthening domestic wood processing industries can reduce overreliance on raw log exports and enhance economic diversification. To this end, policy measures should prioritize the implementation of incentive-driven industrial strategies, including targeted tax exemptions, improved energy access, and dedicated investment support for processing activities such as drying, planing, and assembly. Moreover, the development of integrated and environmentally conscious Special Economic Zones (SEZs)—as exemplified by the Gabon Special Economic Zone (GSEZ)—should be promoted, ensuring alignment with national climate goals and social development priorities (Toman & Jemelkova, 2003; UNCTAD, 2021).

Second, reinforcing forest governance and improving traceability mechanisms are critical for combating illegal logging and ensuring sustainable trade. The persistent institutional weaknesses and loopholes in certification systems undermine regulatory effectiveness. Strengthening national forestry administrations, digitizing logging permits, and enhancing human resource capacity through training programs are essential steps. Additionally, the adoption of digital traceability technologies—particularly blockchain—can improve transparency across supply chains, drawing lessons from pilot initiatives in countries such as Ghana and Brazil (FAO, 2020; World Bank, 2022). Support for the wider adoption of sustainability certifications (e.g., FSC, PEFC, TLAS) through subsidies or technical assistance for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is also recommended.

Third, international trade governance must be reformed to eliminate structural disadvantages faced by tropical timber-exporting countries. The continued dominance of raw material exports is partly explained by tariff escalation and the absence of equitable environmental clauses in trade agreements. In response, reforms to the World Trade Organization (WTO) framework should be pursued, including the removal of tariff barriers on processed wood products and the introduction of environmental mirror clauses for tropical timber imports (Howse & Eliason, 2005). Furthermore, producer countries should be encouraged to establish a coordination mechanism akin to a forestry consortium or cartel to harmonize export policies, stabilize prices, and increase their bargaining power vis-à-vis major importing blocs (e.g., EU, China).

Fourth, enhancing regional integration and fostering South-South cooperation can help overcome the limitations of fragmented national markets. Promoting intra-regional trade in processed timber through preferential trade agreements within regional blocs such as ECOWAS, ECCAS, or ASEAN would be beneficial. Additionally, establishing regional processing hubs with shared infrastructure—such as transportation networks, energy systems, and port facilities—could enhance economies of scale and competitiveness, especially in high-potential trade corridors (UNECA, 2020).

Finally, it is essential to integrate the valuation of ecosystem services provided by tropical forests—such as carbon sequestration and biodiversity conservation—into trade policy frameworks. Strengthening Payment for Environmental Services (PES) schemes, particularly those involving artisanal producers and local communities, can be achieved through mechanisms like REDD+, CAFI, or the Green Climate Fund (GCF). Developing eco-labeling systems tailored to tropical timber products, which combine environmental performance, social inclusion, and traceability, is another promising avenue. Importantly, international buyers should be required to commit to verifiable environmental standards as part of bilateral trade arrangements, such as Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPAs) under the EU FLEGT Action Plan (European Commission, 2018).

Overall, these policy recommendations call for a multi-level, cross-sectoral approach that integrates industrial policy, trade regulation, environmental governance, and international cooperation. Only a coordinated and politically committed strategy—backed by strong international support—can reposition the tropical hardwood lumber trade as a vector for sustainable development in the Global South.

7. Conclusion

The dynamic and static analysis of international trade in tropical hardwood sawnwoods has highlighted the existence of persistent structural inequalities, revealing a trade model that does little to encourage the creation of added value in producing countries. Empirical results confirm that domestic forest production is a decisive lever for exports, while variables such as demographic size or per capita income have only a marginal effect. This finding underlines the need to move beyond a logic of primary specialization inherited from colonial history and reproduced by current world trade structures.

Beyond the diagnosis, this study proposes concrete avenues for reform based on better regional integration, stronger local processing, reinforced forest governance and explicit valuation of ecosystem services. It also calls for a redefinition of North-South trade relations to make them fairer, more sustainable and more transparent. The transition to an inclusive, circular, low-carbon forestry economy in tropical countries is not just an environmental necessity: it also represents a strategic opportunity to regain industrial and commercial sovereignty over resources that have long been undervalued.

Finally, this work paves the way for future in-depth studies. The introduction of environmental variables (deforestation rates, CO22 emissions linked to logging), the analysis of value chains or even the study of the role of public policies in structuring trade flows would deserve to be investigated in future work. For it is in a better understanding of the structural, economic and ecological dynamics of the tropical timber trade that the key to truly sustainable forestry development lies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.M.; methodology, J.M.M. and P.A.O.M.; software, J.M.M.; validation, J.M.M., P.A.O.M., and P.N.N.; formal analysis, J.M.M., P.A.O.M., and P.N.N.; resources, J.M.M., P.A.O.M., and P.N.N.; writing—Original Draft, J.M.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M.M., P.A.O.M., and P.N.N.; visualization, J.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The authors used publicly available datasets to write this manuscript. These datasets are accessible here: (https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=IT.CEL.SETS.P2&country=WLD and https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data and https://www.itto.int/biennal_review/) Accessed on 20 April 2025.

Acknowledgments

National Scholarship Agency of Gabon (Gabonese government) and Chinese government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- ITTO. Tropical Timber Market Report; International Tropical Timber Organization: Yokohama, Japan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lebedys, A.; Li, Y. Contribution of the Forestry Sector to National Economies, 1990–2011; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, C.P.; Treue, T. Assessing illegal logging in Ghana. Int. For. Rev. 2008, 10, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, P.O.; Assembe-Mvondo, S.; German, L.; Putzel, L. The domestic market for small-scale chainsaw milling in Ghana. Int. For. Rev. 2011, 13, 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Karsenty, A. Overview of Industrial Forest Concessions and Concession-Based Industry in Central and West Africa; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]