1. Introduction

Côte d’Ivoire is the world’s largest cocoa producer, contributing over 40% of global cocoa supplies and supporting a significant portion of the country's economy [

1] (Kalischek et al., 2023). Despite this global prominence, Côte d’Ivoire captures minimal economic value from its cocoa exports due to the dominance of industrialized nations in higher-value stages of the cocoa value chain, such as processing and manufacturing. Value addition typically occurs outside the producing regions, highlighting a structural imbalance that limits economic benefits for local stakeholders. The cocoa sector faces compounding challenges, including volatile global prices and vulnerability to climate change. Irregular rainfall, rising temperatures, and extreme weather events have increasingly disrupted production cycles, threatening long-term sustainability. Moreover, domestic processing capacities remain underutilized, limiting the potential for economic diversification and resilience. Cocoa contributes approximately 15% of Côte d’Ivoire’s GDP and 7% of Ghana’s GDP GDP [

2], making it a cornerstone of economic activity in both nations (Diomande et al., 2023), and cocoa exports make up about 70% of the country’s total export revenues, solidifying its position as a critical driver of foreign exchange earnings. However, despite its global dominance in cocoa production, Côte d’Ivoire captures only a fraction of the total value generated by the global cocoa [

3] industry (Abaidoo & Agyapong, 2023). The global cocoa value chain is structured in a way that positions cocoa-producing countries such as Côte d’Ivoire at the lower end, primarily as suppliers of raw materials. The bulk of value addition, including processing, manufacturing, and distribution of chocolate products, occurs in industrialized nations where significant profits are realized, leaving Côte d’Ivoire dependent on raw cocoa exports and vulnerable to global market fluctuations [

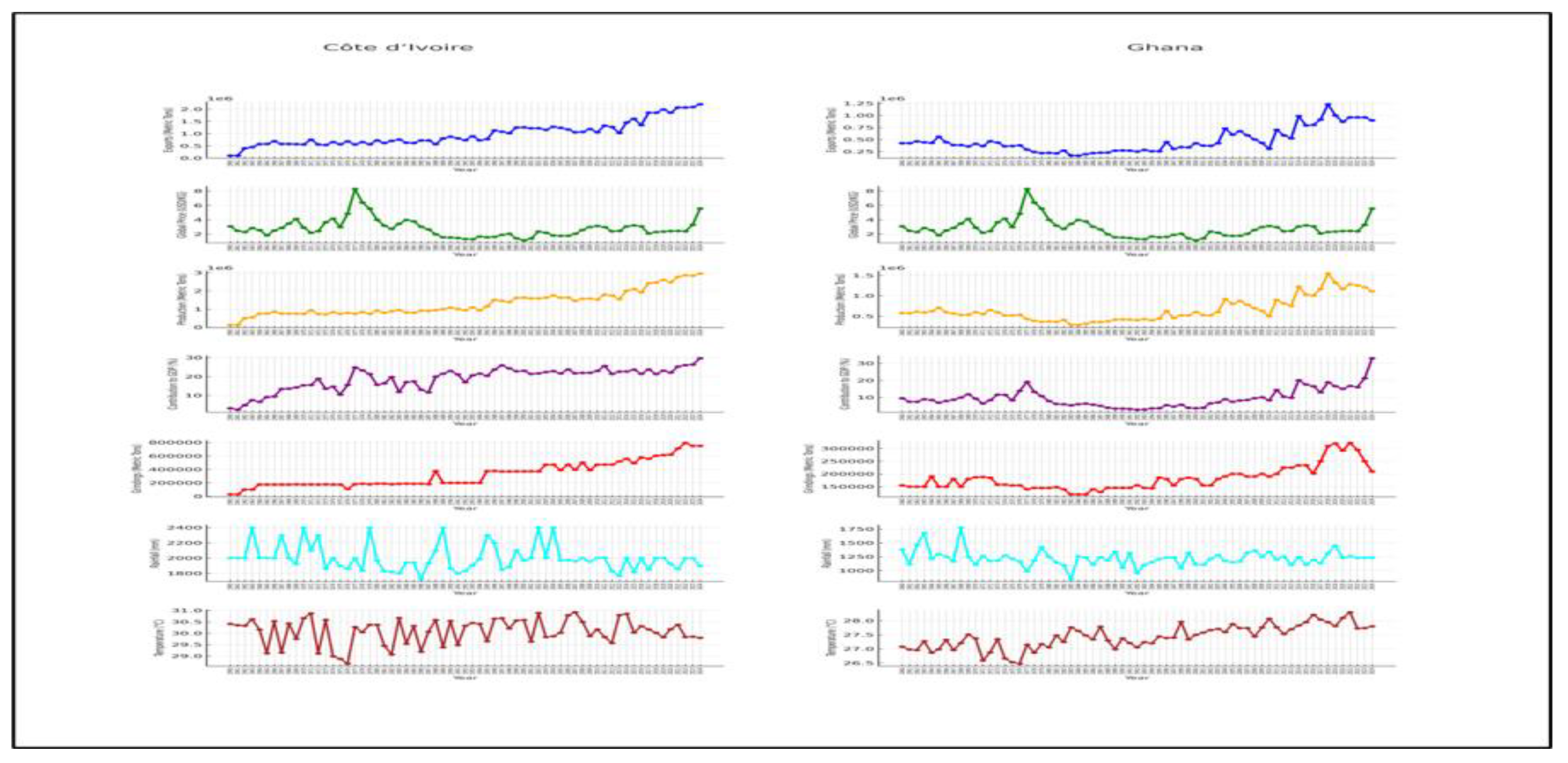

4] (Daya et al., 2023). Environmental challenges further compound these vulnerabilities. Cocoa farming contributes to deforestation and environmental degradation, particularly in forested regions cleared for agricultural use, leading to biodiversity loss and ecosystem disruption. The impacts of climate change, including irregular rainfall patterns, rising temperatures, and unpredictable weather, pose additional threats to productivity, as rainfall declined to 1,897.50 mm in 2024 and average temperatures [

5] increased to 29.8°C (World Bank, 2021). These climate-related stresses reduce yields and expose farmers to greater risks, necessitating the adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices. Socio-economic issues, including widespread poverty among cocoa farmers and the persistence of child labor, further undermine the sector’s sustainability. Despite international efforts through certification schemes and sustainability programs, progress in addressing these social issues has been slow, limiting the industry’s potential for inclusive economic development [

6] (Kadio, 2023). The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these vulnerabilities by disrupting global supply chains, causing cocoa prices to fluctuate to 5.56 USD/kg in 2024 while temporarily reducing demand for luxury products [

7] (IFPRI, 2024). The pandemic’s broader impact on Côte d’Ivoire’s secondary [

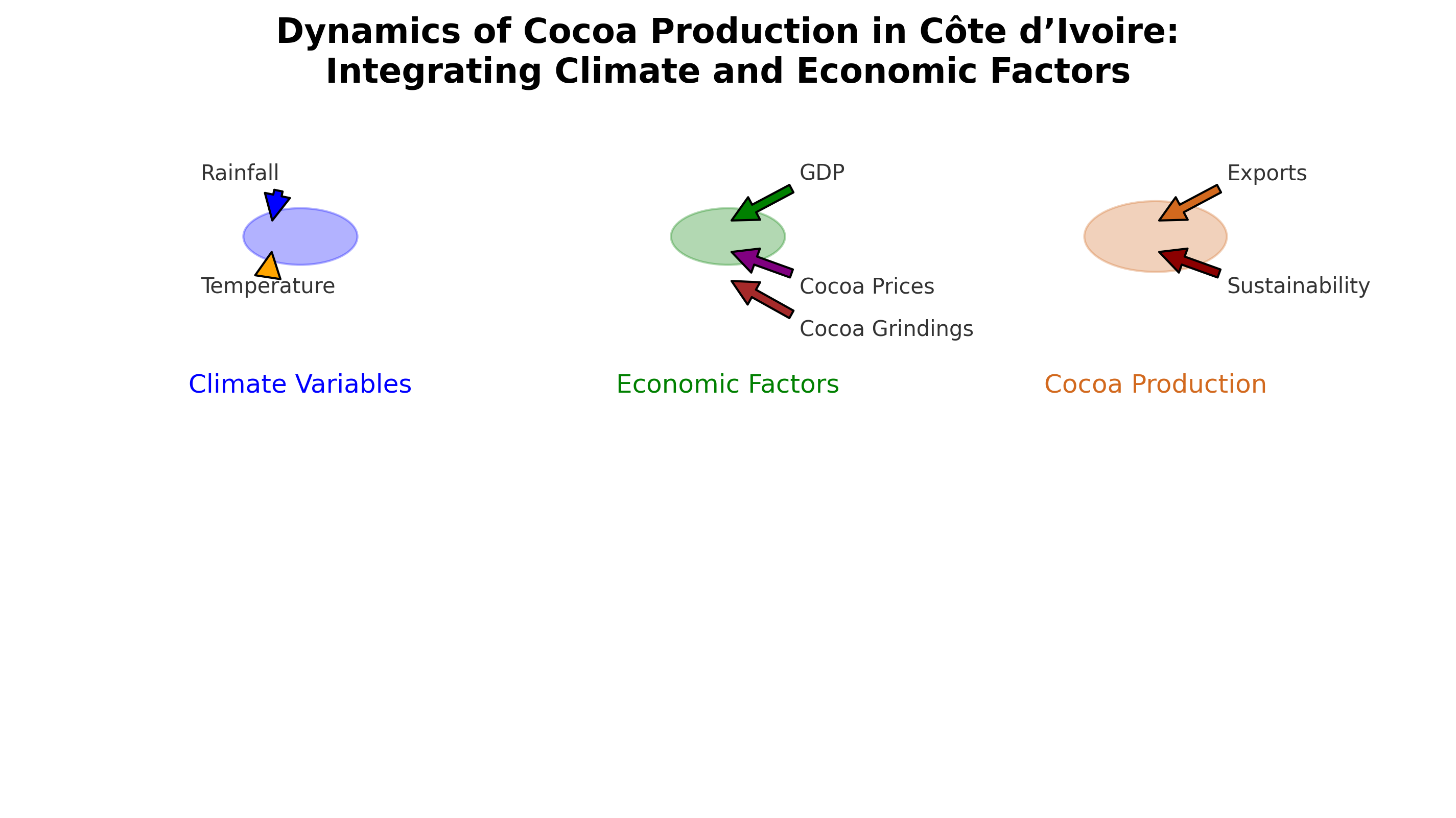

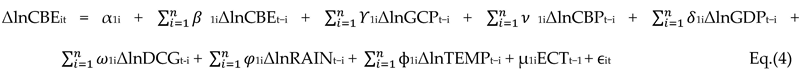

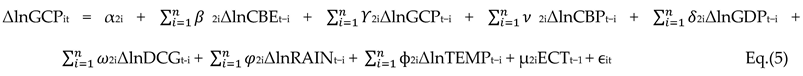

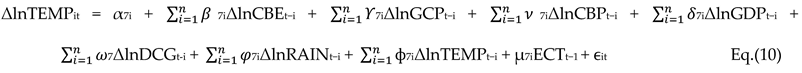

8] economic sectors, such as transportation and logistics, also reverberated through the cocoa value chain (Dago & Pei, 2024). These challenges underscore the critical need for strategies that enhance both the economic resilience of cocoa farmers and the country’s competitiveness in the global market. Existing studies have explored the global cocoa value chain and environmental challenges but often fail to integrate local processing capabilities, sustainability practices, and external trade policies to improve value capture and resilience in producing countries. This research fills a critical gap by uniquely integrating climatic variables with macroeconomic factors to model the cocoa industry's performance, thereby offering actionable insights for enhancing sustainability and value addition. This paper integrates climatic and economic variables using advanced econometric modeling, providing novel insights into Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa industry and a regional comparison with Ghana, including the Vector Error Correction Model (VECM), to explore the short- and long-term dynamics of key variables, such as global cocoa prices, domestic cocoa grindings, rainfall, and temperature, and export performance. The objectives of this study are to evaluate Côte d’Ivoire’s position in the global cocoa value chain, assess the impact of international cocoa prices on domestic production and exports, analyze the role of local cocoa processing in improving value capture, and investigate the effects of climate factors such as rainfall and temperature on production and exports. The research questions address key issues, such as Côte d’Ivoire’s position in the global cocoa value chain, the influence of global cocoa price fluctuations on domestic production and exports, the impact of domestic processing and GDP contributions on export performance, and the effects of climate factors on cocoa productivity. The study also explores hypotheses related to the relationships between global prices, domestic processing, climate factors, and cocoa production and exports. The significance of this study lies in its potential to provide actionable insights for policymakers, industry leaders, and international organizations to enhance the sustainability and competitiveness of Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa industry. The findings are expected to inform decisions on environmental policies, economic resilience strategies, and social equity measures. The study is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the literature and presents the theoretical framework for analyzing the cocoa industry.

Section 3 details the research methodology.

Section 4 presents the results and discussion, while

Section 5 concludes with a summary of findings and recommendations for strengthening the industry’s future performance.

2. Literature Review

The global cocoa industry has been widely studied, particularly in terms of its economic importance, environmental sustainability challenges, and the role of global value chains. Recent studies highlight the role of blockchain in cocoa value chains and climate-smart techniques addressing yield variability [

9,

10] (Gómez-Briones et Carla., 2019; Akpoti et al., 2023). However, it is important to note that the majority of value addition, including processing and manufacturing, occurs in industrialized nations, which consequently limits the economic returns for producing countries such as Côte d’Ivoire. This dynamic is not exclusive to cocoa but extends across various commodity value chains, where producer countries are relegated to the lower end of the global value [

11,

12,

13,

14] chain due to structural inefficiencies, restrictive trade policies, and limited technological capacities (Odijie, 2021; Prazeres et al., 2021; Staritz et al., 2022).

For example, Indonesia faces parallel issues where high tax burdens significantly impede the competitiveness [

15] of processed cocoa products in global markets (Murwendah & Desyani, 2023). This highlights how governmental and regulatory factors constrain value addition processes, thus affecting the global [

16] positioning of producer countries (Pietrobelli et al., 2021). Moreover, compounding these economic barriers are climate-related risks and inadequate infrastructure, which collectively hinder sustainable growth [

17], technological advancements, and domestic cocoa grindings in Côte d’Ivoire (Houphouet et al., 2023).

To address these challenges, recent advancements in circular economy practices present promising opportunities. For instance, innovative technologies developed by organizations such as Nextcoa focus on repurposing cocoa waste into valuable products, such as biopolymers and functional food ingredients, thereby contributing to a more circular economy [

18,

19,

20] (Pedraza-Avella et al., 2023; Girón-Hernández et al., 2024; Cydzik-Kwiatkowska, 2021). These innovations, while promising, face barriers in Côte d’Ivoire due to financial and infrastructural limitations, which prevent the widespread adoption of such practices [

21] (Dziuba et al., 2021). Furthermore, digitalization and traceability within global value chains emerge as significant enablers for the cocoa industry, as evidenced by blockchain technology's potential to improve transparency, ensure compliance with international sustainability standards, and enhance market access to premium sectors [

22,

23] (Zheng et al., 2023; Cao et al., 2023). Yet, the adoption of these digital innovations remains limited in Côte d’Ivoire, necessitating stronger governance frameworks to unlock their transformative potential and align with global standards.

Simultaneously, environmental sustainability remains a critical challenge, particularly in cocoa-producing regions of West Africa. Unsustainable farming practices have led to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and soil degradation, with these impacts exacerbated by climate change. Research underscores that deforestation linked to cocoa farming has disrupted local precipitation patterns, further reducing cocoa bean production [

24,

25] (Schneider et al., 2023; Renier et al., 2022). However, agroforestry, which integrates trees into cocoa farming systems, emerges as a viable solution to mitigate these environmental challenges [

26] (Moraiti et al., 2024). Agroforestry systems enhance biodiversity, improve soil fertility, and sequester carbon, thereby offering economic and ecological benefits [

27,

28] (Dahliana et al., 2024; Salamanca et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the adoption of agroforestry in Côte d’Ivoire remains limited due to insecure land tenure, inadequate technical support, and insufficient financial incentives, which contrasts sharply with Ghana’s success in scaling such practices through policy and institutional support. Thus, addressing these gaps requires an integrated approach that includes land reforms, capacity-building programs, and financial assistance to farmers, aiming for both environmental [

29,

30] sustainability and enhanced contributions to Gross Domestic Product degradation (Donkor et al., 2023; Olagunju et al., 2023).

In addition to environmental [

31] concerns, socio-economic challenges compound the difficulties faced by Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa farmers (Kadiravan et al., 2023). Despite the sector's economic significance, smallholder farmers continue to struggle with income instability due to fluctuating global cocoa prices, limited access to financial services, and weak bargaining power [

32,

33] (Boysen et al., 2023; Cui et al., 2023). Furthermore, Côte d’Ivoire’s reliance on cocoa bean exports exacerbates these vulnerabilities, as raw commodity exports yield limited economic value compared to processed cocoa products. Addressing these issues, initiatives such as the Income Accelerator Program have shown potential in closing income gaps and reducing child labor risks, although their scalability remains constrained by systemic governance challenges [

34] (Nestle, 2023).

Furthermore, child labor remains a persistent issue in the cocoa sector, driven by extreme poverty and limited access to education. While programs such as the Harkin-Engel Protocol aim to eliminate child labor, enforcement challenges and entrenched cultural norms continue to hinder their effectiveness [

35] (Busquet et al., 2021). Consequently, effective solutions must integrate robust labor laws, improved education access, and direct financial support for vulnerable households to break the cycle of poverty and child labor.

Beyond these socio-economic and environmental factors, climate change poses a significant and escalating threat to cocoa production. Rising temperatures, unpredictable rainfall, and extreme weather events not only disrupt farming systems but also exacerbate existing vulnerabilities such as low yields and inadequate infrastructure. Studies indicate that climate-induced disruptions to water supplies, a critical resource for agriculture, further jeopardize cocoa farming [

36,

37] (Bamba et al., 2023; Tran & Cook, 2023). In response, innovative strategies such as crop diversification, precision agriculture, and agroforestry have been adopted in various cocoa-producing countries, including Ghana, where these approaches have enhanced resilience and productivity [

38,

39] (Zhafran et al., 2022; Yiridomoh et al., 2022). Nonetheless, the implementation of such adaptive strategies in Côte d’Ivoire is constrained by resource limitations and a lack of technical expertise, highlighting the need for targeted investments and training programs to build adaptive capacity while safeguarding cocoa bean production.

Meanwhile, the cocoa industry has also been significantly affected by external shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic exacerbated existing vulnerabilities within cocoa supply chains, leading to production declines, delayed shipments, and income losses for farmers in West Africa [

40,

41] (Basith et al., 2023; Merino-Gaibor et al., 2023). Moreover, geopolitical tensions and climate-induced disasters continue to pose ongoing risks to the sector, emphasizing the need for resilience-building measures [

42] (Aniekan Ukpe, 2024). Digital technologies, such as blockchain, offer a pathway to strengthen supply chain resilience by enhancing transparency and traceability, as evidenced by their application in Ghana's cocoa sector [

43] (Lu et al., 2023). However, Côte d’Ivoire must prioritize reducing infrastructural barriers and incentivizing technology adoption to realize similar benefits.

Finally, governance and policy interventions play a crucial role in shaping the sustainability and competitiveness of Côte d’Ivoire's cocoa sector. Effective governance ensures compliance with environmental and labor standards while promoting equitable growth across the value chain. Trade policy reforms, including reduced tariff escalation and incentives for processed cocoa exports, are essential to enhance Côte d’Ivoire's positioning within the global cocoa market. Moreover, institutions such as the Conseil du Café-Cacao must spearhead efforts to integrate digital innovations and foster public-private partnerships to achieve systemic improvements.

This study builds on existing literature by examining how economic, environmental, and social factors collectively influence Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa industry. Through a comparative analysis with Ghana and the application of advanced econometric models, this research identifies actionable strategies to address systemic challenges, enhance sustainability, and bolster competitiveness. Leveraging insights from both countries, the study provides practical recommendations to position Côte d’Ivoire as a global leader in sustainable and value-added cocoa production.

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Theoretical frameworks are essential for understanding the dynamic interactions between economic and environmental variables influencing Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa industry within the global production chain. The analysis is grounded in the export-led growth hypothesis, which posits that increased exports drive economic development by generating foreign exchange, employment, and technological advancement. This hypothesis aligns with the central role of cocoa exports in both countries' economies. These frameworks highlight the interconnectedness between domestic production factors, external market forces, and climatic conditions, shaping the industry’s export performance. Cocoa exports [

44,

45]increased to 1.68 million metric tons by 2021, with projections reaching 2.2 million metric tons by 2024 (Statista, 2024; ICCO, 2024). Gross cocoa production [

46] also grew from 1.591 million metric tons in 2001 to a forecasted 2.95 million metric tons by 2024 (FAO, 2022). This study focuses on the factors influencing cocoa exports, including production, cocoa prices, GDP, domestic grindings, rainfall, and temperature, and their combined impact on the sector's performance. Unlike previous studies that broadly examine agricultural economics or climate change, this research delves into sector-specific dynamics and value chain mechanisms, providing insights into sustainability and competitiveness. Value chain improvements, such as certification schemes and sustainable farming practices, have been shown to enhance sector performance and resilience [

47] (Tennhardt et al., 2023). These factors are critical in addressing external shocks such as price volatility and in improving the long-term competitiveness of Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa industry. The study employs econometric models, including the Vector Error Correction Model (VECM), to capture short-term adjustments and long-term equilibrium relationships. Testing for stationarity and cointegration ensures robust, reliable predictions. Incorporating climatic variables provides a nuanced understanding of cocoa production’s vulnerabilities to erratic weather patterns, emphasizing the importance of climate-resilient agricultural practices such as agroforestry and drought-resistant crops [

48] (Zelingher & Makowski, 2023). By integrating economic, climatic, and value chain analyses, this framework explores the interplay between internal production capabilities and external market forces. These findings provide actionable insights to strengthen Côte d’Ivoire’s resilience and global competitiveness, ensuring sustainable growth. The study offers a solid foundation for designing targeted policies to address future challenges and reinforce the country’s position as a global cocoa leader.

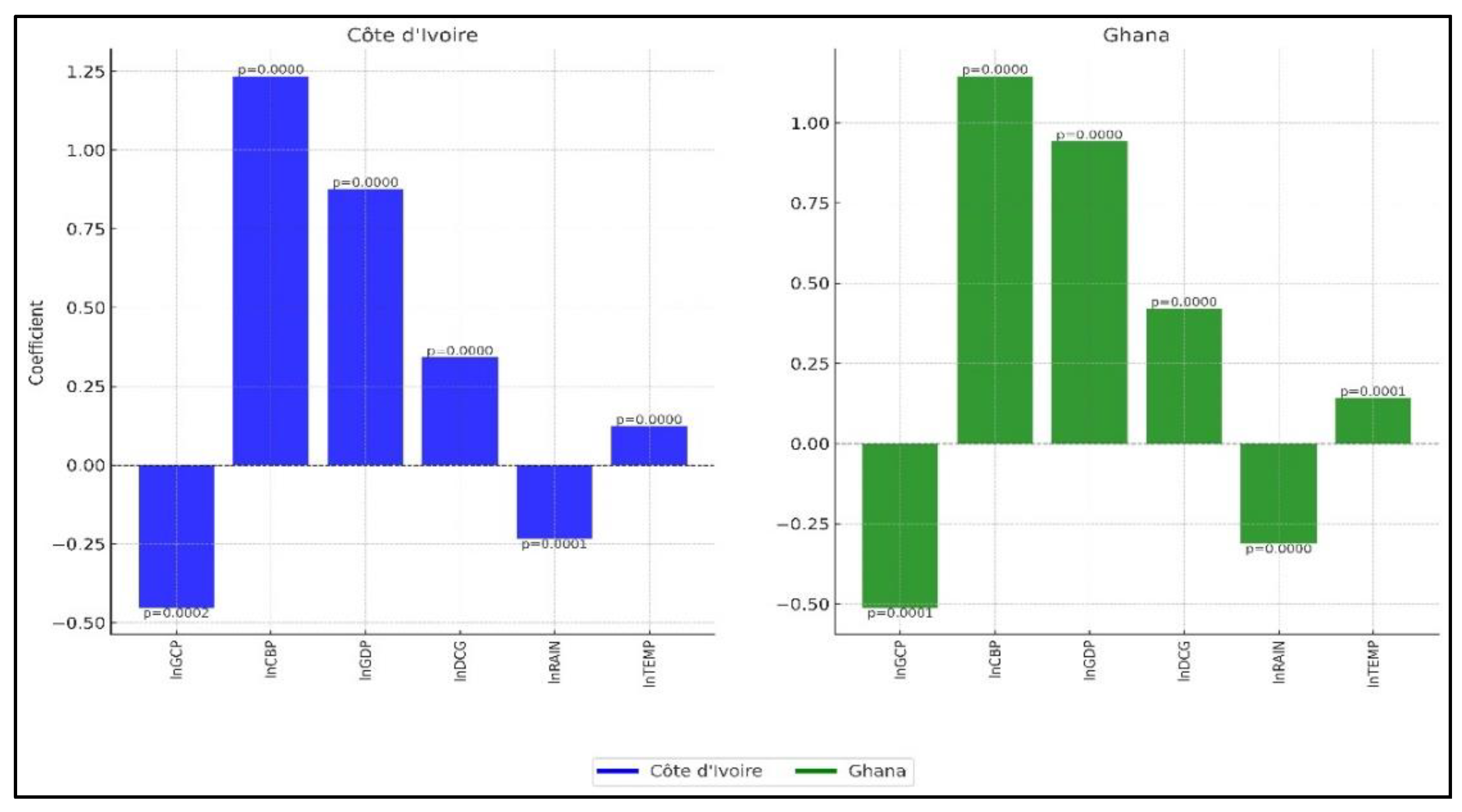

H1: Increases in global cocoa prices positively impact cocoa bean exports.

H2: Higher levels of domestic cocoa grindings reduce raw cocoa bean exports.

H3: An increase in cocoa production’s contribution to GDP is positively associated with cocoa bean exports.

H4: Rainfall and temperature positively influence the relationship between cocoa bean production and cocoa bean exports.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

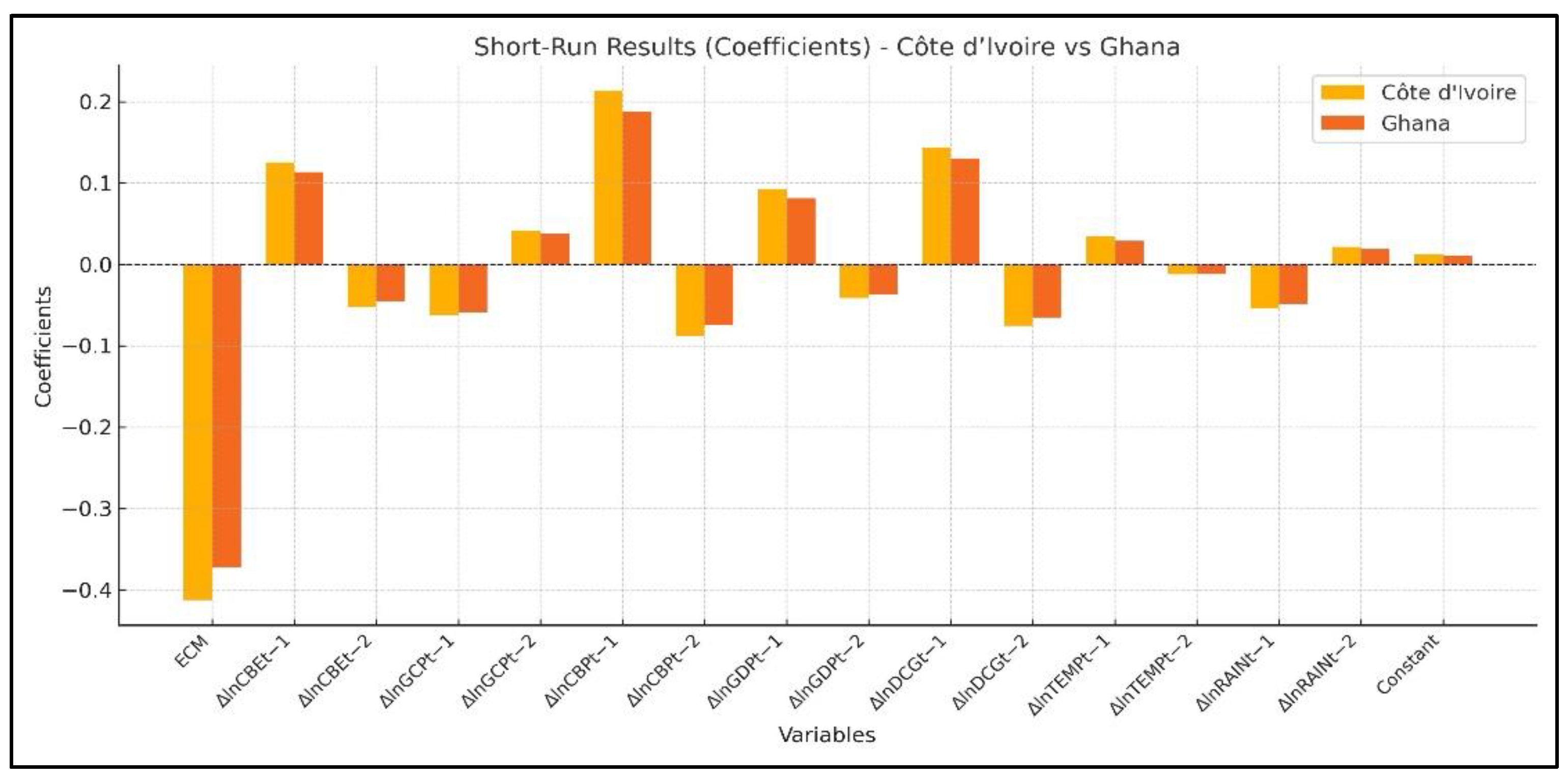

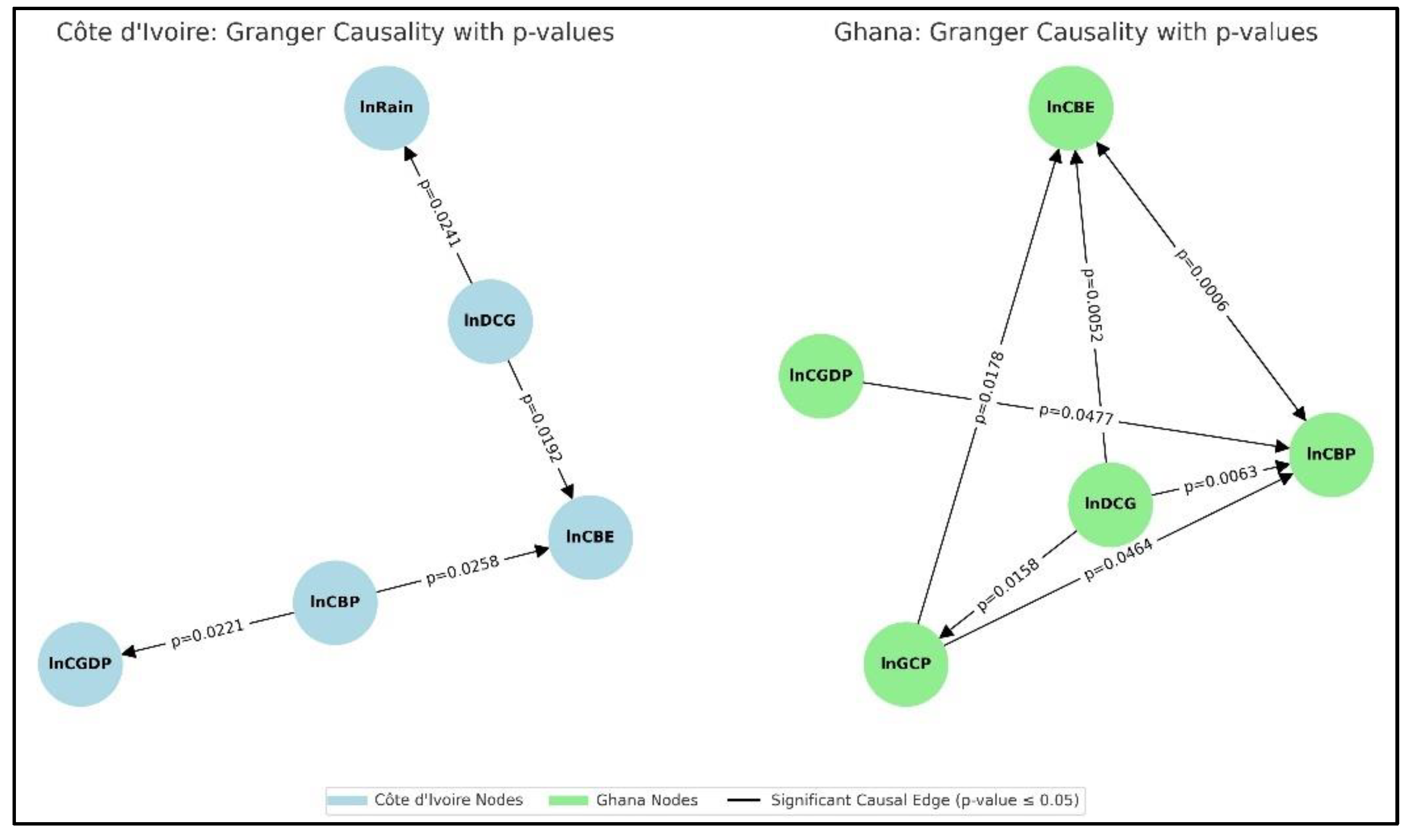

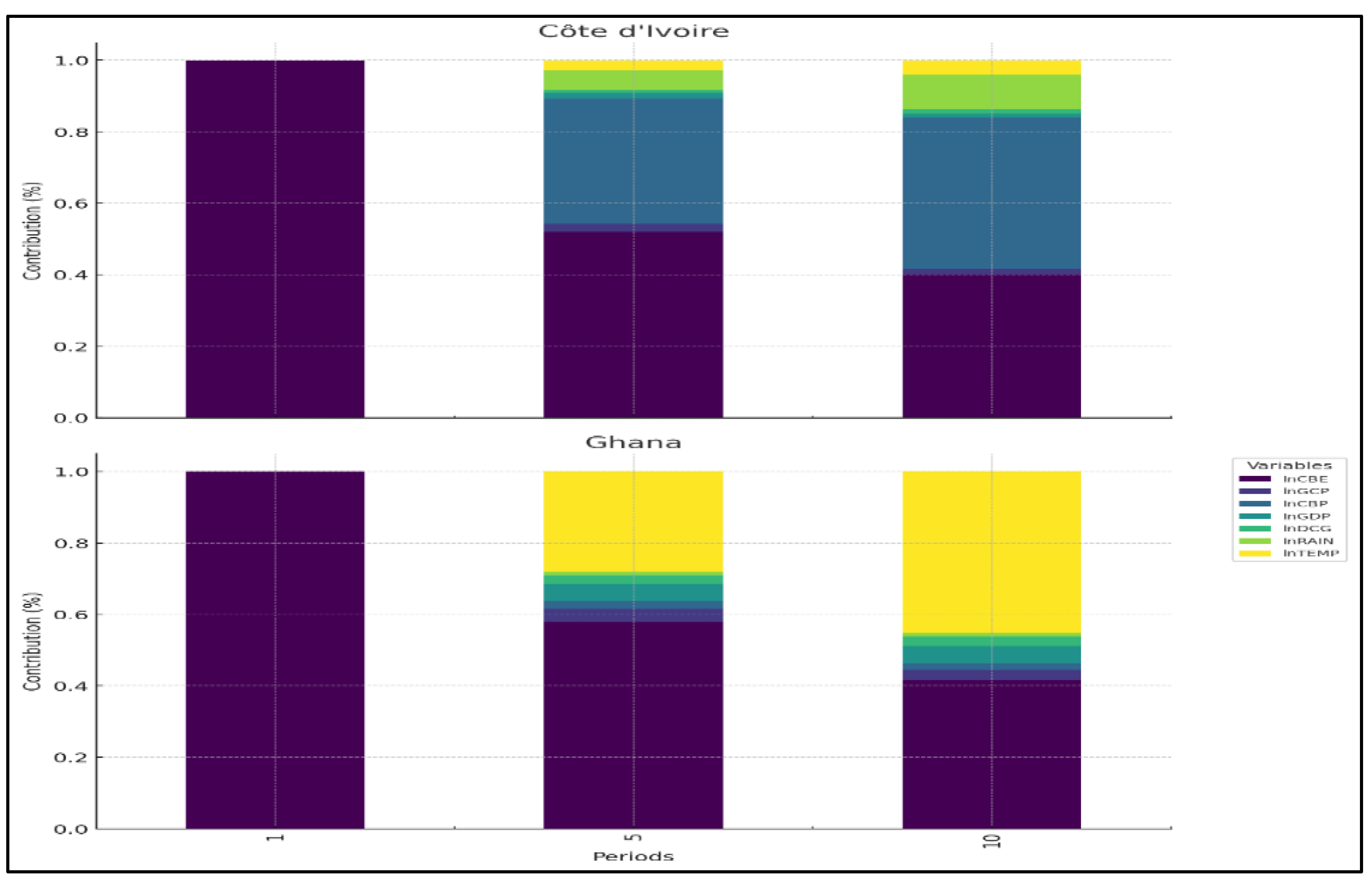

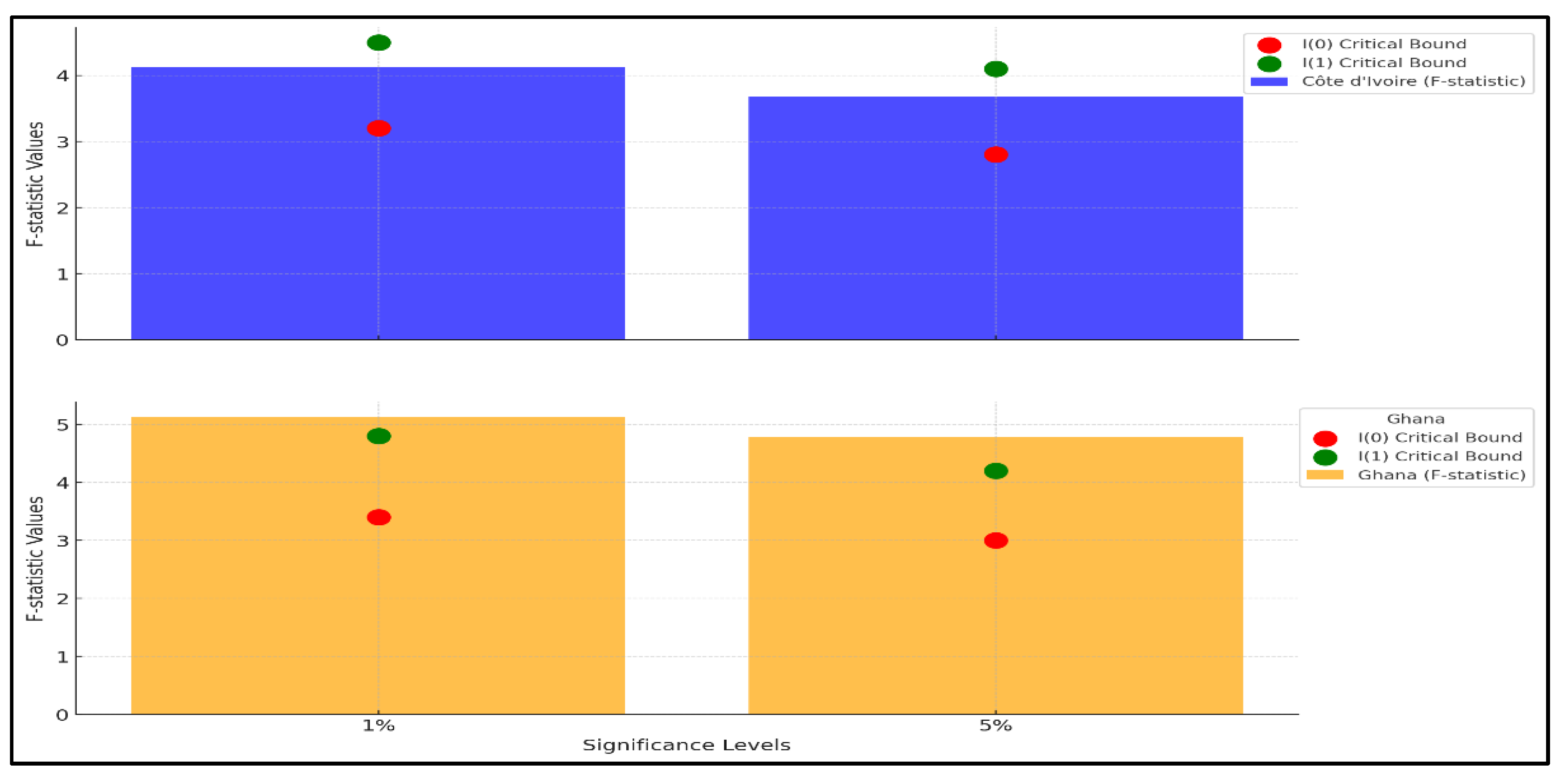

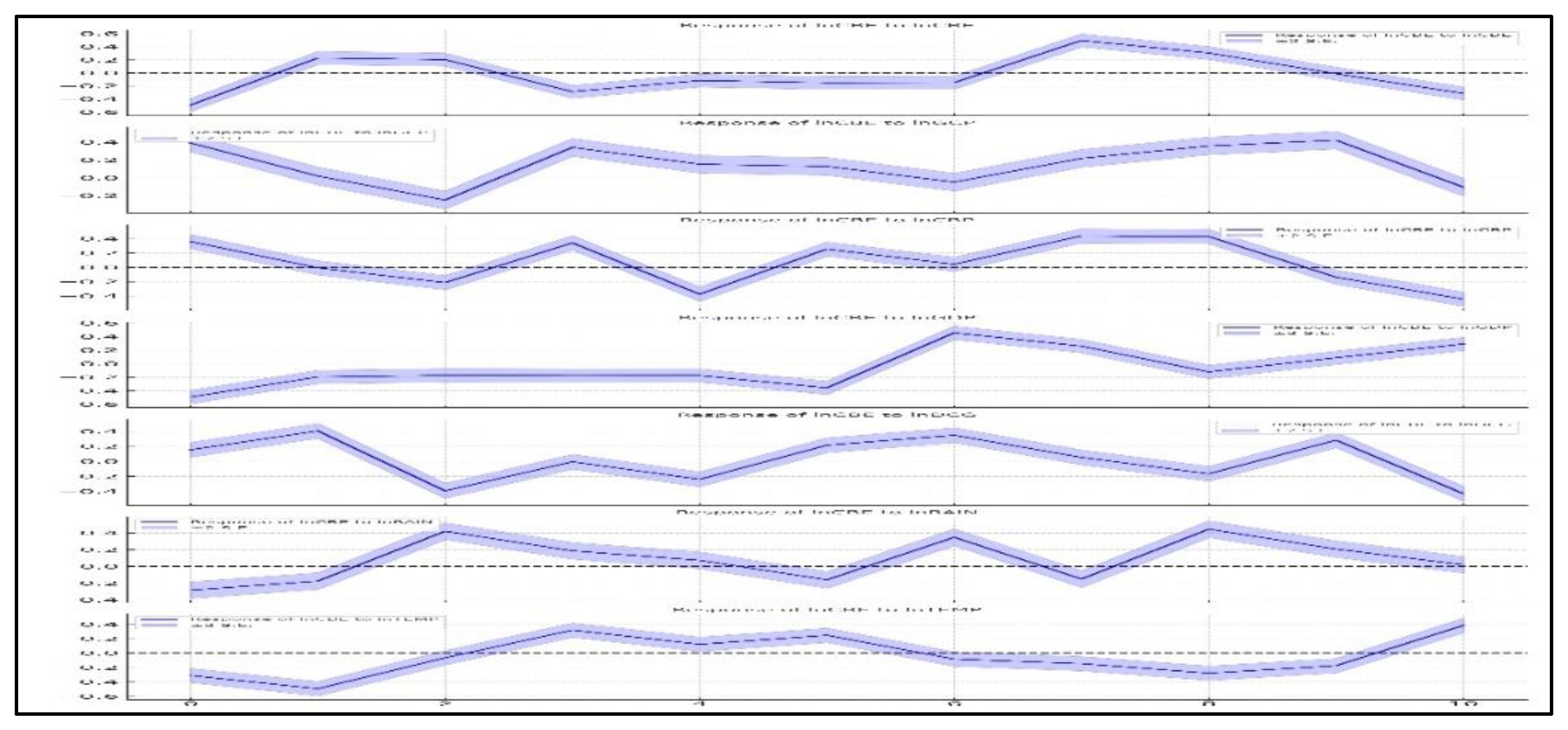

This study assessed the position of Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa industry in the global production chain, focusing on the key factors influencing its performance within a panel of countries including Ghana. To this end, the study employed a Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) to analyze the relationships between cocoa bean exports and influencing variables. Primarily, Côte d’Ivoire served as the base country for analysis, with annual data spanning from 1960 to 2024 to capture both historical and contemporary trends in cocoa production and export dynamics. The results revealed significant effects of gross cocoa production, cocoa bean prices, GDP, domestic cocoa grindings, rainfall, and temperature on cocoa exports, highlighting the interplay between economic and environmental factors. Relaxing the model to capture dynamic interactions among variables provided robust insights into short- and long-term adjustments within the system, ensuring the accuracy of findings through rigorous diagnostic testing.

The results yield several notable insights. First, gross cocoa production emerged as the most critical determinant of export performance, emphasizing the need for policies targeting productivity improvements through modern farming techniques, high-yield crop varieties, and farmer education. Second, cocoa prices exhibited a dual influence: while higher prices incentivize production, they expose the sector to global market volatility, necessitating stabilization measures such as price hedging mechanisms. Third, domestic cocoa grindings demonstrated their pivotal role in enabling Côte d’Ivoire to retain more value within the production chain, highlighting the importance of enhancing local processing capacities to boost value addition. Fourth, climatic variables underscored the vulnerability of cocoa production to rainfall variability and temperature fluctuations, necessitating the adoption of climate-adaptive practices such as irrigation systems, agroforestry, and drought-resistant crop varieties. Finally, GDP reflects the sector’s reliance on macroeconomic stability to drive infrastructure development and technological advancements.

These findings substantiate the need for an integrated approach to improve the resilience and sustainability of Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa sector. To that end, the study recommends enhancing local processing capabilities through domestic cocoa grindings, implementing price stabilization mechanisms, adopting climate-resilient agricultural practices, and investing in critical infrastructure such as transportation networks and storage facilities. This study offers a framework for integrating climatic and economic factors, with insights for regional resilience and sustainability. Additionally, developing rural financial systems to support farming communities remains crucial to sustain growth. In conclusion, the study highlights the importance of diversifying economic strategies to bolster the cocoa sector's performance against market and environmental vulnerabilities while ensuring its sustainability and global competitiveness.