1. Introduction

Cold gas dynamic spray (CGDS) is a solid-state coating method in which powder particles are accelerated by a high-pressure gas jet (often through a de Laval nozzle) to supersonic speeds and bonded onto a substrate by plastic deformation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Because the particles remain below their melting point during deposition, oxidation and other thermal degradation are minimized [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], preserving the original powder microstructure. This leads to dense, low-porosity coatings with fine microstructure and mainly compressive residual stresses [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In contrast to thermal spray, CGDS can coat temperature- sensitive substrates without metallurgical damage. Recent reviews and texts have documented the materials science of CGDS, noting that a wide range of feedstocks – from pure metals to alloys to metal– matrix composites – can be deposited [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In particular, the solid-state bonding mechanism (via severe plastic deformation at impact) has enabled high-purity coatings and uniform microstructures [1– 5,7,8]. Critical parameters such as gas stagnation pressure, temperature, nozzle geometry and stand-off distance govern the particle velocity and impact state [

7,

8,

26], which in turn determine whether particles exceed the critical velocity needed for bonding [

7,

8,

26,

27]. Because CGDS handles diverse materials, composite coatings have attracted much interest. Metal– matrix composite (MMC) coatings, combining a ductile matrix with hard reinforcement particles, can yield a balance of corrosion protection and mechanical strength that pure metals alone cannot provide [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

20]. For example, ductile matrices such as Al, Cu or Ni have been reinforced with ceramic or nanomaterial additives (Al₂O₃, SiC, WC, TiC, carbon nanotubes, etc.) to improve hardness and wear resistance [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Cold-sprayed Cu–CNT [

21], WC–Ni [

22], Ni–WC [

23], Ni–Ti [

25], and Cr₃C₂-based [

24] composite coatings have all shown superior tribological performance compared to the base metal [

20]. To achieve uniform composite powders, advanced feedstock preparation methods such as spray drying or satelliting are commonly applied [

14]. For example, binder-assisted satelliting of TiC onto Al has been shown to produce a more uniform composite feedstock and more stable spray flow than a simple mechanical blend [

14]. Following this principle, a similar agglomeration strategy was adopted here to combine Al, Zn and TiO₂ into a single feedstock for cold spraying.

A key application of CGDS is corrosion protection of steel. Zinc and aluminum are widely used as protective coatings: Zn provides sacrificial anodic protection, while Al forms a dense passive barrier [

10,

15,

16,

17,

30]. Cold-sprayed Zn–Al alloy coatings have gained considerable attention because they combine the galvanic protection of Zn with the corrosion resistance of Al [

16,

17]. Studies on thermal spraying have shown that Zn–Al systems (e.g., Zn85–Al15) can benefit from post-treatment such as sealing, which further reduces corrosion rates [

15]. These findings indicate that Al–Zn composites (sometimes referred to as pseudo-alloys) can significantly enhance steel protection. However, pure Al or Zn coatings tend to be relatively soft or porous, which may limit their wear resistance. To address this issue, hard oxide reinforcements are commonly incorporated. Ceramic oxides such as alumina [

18] and titania [

19] are well-known for improving hardness and wear performance. Cold-sprayed TiO₂ coatings have also been successfully produced using nitrogen as the process gas [

19], and the addition of TiO₂ particles into a metal matrix is expected to enhance coating hardness without compromising the metal’s corrosion-protective function. Cold-sprayed metal matrix composites (MMCs) containing ceramic reinforcements generally exhibit improved mechanical and tribological performance [

20]. Therefore, an Al–Zn matrix with dispersed TiO₂ particles could provide both enhanced corrosion protection and increased wear resistance.

Optimizing a multi-component cold-spray process is complex, which makes computational modeling a valuable tool. Various analytical and numerical models have been developed to predict particle dynamics and deposition behavior in cold spray [

11,

26,

27,

28]. Gas–particle flow in mixed powder streams has been analyzed to clarify how key parameters such as gas pressure, temperature, nozzle design, and particle size affect the deposition window [

11,

26]. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and finite element methods have been widely applied to simulate particle trajectories, velocities, and impact stresses under varying spray conditions [

26,

27,

28]. Such models enable prediction of critical velocities and coating formation thresholds, providing guidance for process parameter selection. Recent reviews emphasize how advanced modeling approaches are increasingly integrated into cold spray and additive manufacturing design workflows [

27,

28]. In addition, the mechanical performance of cold-sprayed coatings, including fatigue behavior, has been investigated to highlight the importance of producing high-quality, optimized deposits [

29].

In this work, we combine COMSOL Multiphysics® simulations with experiments to optimize CGDS of agglomerated Al–Zn–TiO₂ powders on steel. The purpose is to identify spray conditions that maximize particle velocity and bonding for our composite feedstock. We simulate the gas flow and particle impact for various pressures, temperatures, stand-off distances, and spray angles, and predict the resulting coating deposition quality. Guided by the model, we determine that the optimum parameters are a carrier gas pressure of 6 atm, a preheat temperature of 600 °C, a stand-off distance of 15 mm, and a 90° (normal) spray angle. These optimal conditions were then validated experimentally by coating steel substrates, yielding adherent, uniform Al–Zn–TiO₂ coatings with improved corrosion and wear performance. The novelty of this study lies in the combined computational–experimental approach for multi-component cold spraying, and in establishing these specific optimal parameters for the Al–Zn– TiO₂ system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock Powder and Substrate Preparation

Powder Composition: The coating material was a nanocomposite powder consisting of aluminum (Al) as the ductile metallic matrix, zinc (Zn) as a secondary metal additive, and titanium dioxide (TiO₂) as a ceramic reinforcement. Aluminum provides a lightweight, corrosion-resistant matrix, while zinc offers sacrificial anodic protection to steel, and TiO₂ contributes hardness and stability (and potential photocatalytic effects). Commercially available Al powder (spherical particles, high purity) and Zn powder were used. The TiO₂ was nano- to sub-micron sized anatase particles. Two methods were explored to prepare a homogeneous Al–Zn–TiO₂ powder blend:

- Chemical Agglomeration Method: In this approach, Al powder and TiO₂ nanoparticles were combined in a liquid dispersion with surfactants to promote TiO₂ attachment onto Al particle surfaces. Specifically, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was used as a temporary binder to adhere TiO₂ to Al, and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC, 2 wt% in water) was added as a rheological stabilizer during mixing. The suspension containing Al and TiO₂ was ultrasonically agitated and stirred to encourage TiO₂ nanoparticles to coat the Al particles. The mixture was then dried and lightly milled to yield agglomerated composite particles. This method was intended to create nano-TiO₂ decorated Al particles. However, it was found that the chemically agglomerated powder had issues with agglomerate size and flowability. After spray deposition, coatings from this powder were relatively porous and uneven, with lower adhesion. The chemical binding of TiO₂ was not sufficiently strong to withstand the high-velocity impact, leading to some TiO₂ detachment and less uniform distribution in the coating. As a result, the chemically prepared powder yielded coatings of inferior quality (lower density and adhesion).

- Mechanical Mixing Method: In this method, the Al, Zn, and TiO₂ powders were combined by dry mechanical blending. A vibratory ball mixer was used to thoroughly mix the powders in the desired weight ratio (Al being the majority, Zn and TiO₂ as minor fractions). The mechanical mixing helped to distribute Zn and TiO₂ uniformly among the Al particles without any binders. This dry mixing produced a composite powder with good flowability and a more even dispersion of TiO₂ on and among the Al/Zn particles. Coatings produced from the mechanically mixed powder exhibited higher density (nearly fully dense, <0.5% apparent porosity) and more consistent microstructures. The adhesion of these coatings to the substrate was also significantly better than those made from the chemically agglomerated powder. The improved performance is attributed to the more uniform distribution of reinforcement and the absence of residual binders. Given these advantages, the mechanically blended Al–Zn–TiO₂ powder was chosen for all further cold spray experiments in this study.

Substrate Material and Preparation: The substrates used were coupons of mild steel (structural steel grade S235JR, equivalent to ASTM A36). Two types of sample geometries were prepared to examine coating behavior on different surface curvatures: (1) flat coupons of 50 mm × 50 mm area and 10 mm thickness, and (2) curved semi-spherical coupons with approximately 30 mm radius of curvature (dome- shaped, 5 mm thick). A total of 22 substrate samples were prepared, allowing various spray parameter conditions to be tested. Prior to coating, the steel substrates underwent surface preparation to ensure adequate coating adhesion. The steel surfaces were first ground with abrasive paper and degreased with acetone to remove any rust or contaminants. Then, a grit-blasting (abrasive sandblasting) treatment was applied. This abrasive blasting effectively increased the surface roughness and created a textured profile to promote mechanical interlocking of the cold-sprayed particles. Typical surface roughness after blasting was in the range of Ra ≈ 5–6 µm (arithmetic average roughness), with peak-to-valley height Rz on the order of 30–50 µm. The roughened substrates were cleaned of any loose grit and again degreased before coating. This surface preparation conforms to common practice for thermal spray/coating adhesion improvement.

2.2. Cold Gas Dynamic Spraying Process

Cold spraying was carried out using a high-pressure CGDS system (Dymet 404 equipment) equipped with a de Laval convergent–divergent nozzle.

Nozzle Geometry: The nozzle had a throat diameter of 2 mm and an outlet diameter of 6 mm, with a diverging section that expands the gas flow to supersonic speeds. The nozzle shape and dimension (

Figure 1) designed to produce a high-velocity gas jet for efficient particle acceleration. The stand-off distance (nozzle exit to substrate) was varied in this study between 5 mm and 25 mm as one of the parameters of interest.

Spray Parameters: Based on preliminary modeling and literature, the primary variables selected for optimization were the gas stagnation temperature, gas pressure, stand-off distance, and powder feed rate. A air gas propellant was used for all runs. The gas temperature was set in the range 400– 600 °C (673–873 K) as measured at the heater exit (before the nozzle). The gas pressure (stagnation pressure at nozzle inlet) was set around 8 atm (≈0.8 MPa) in the supply line; due to pressure losses in the system, the effective pressure at the nozzle inlet was around 6 atm (0.6 MPa). Thus, in modeling we consider 4.0×10^5 to 6.0×10^5 Pa as the pressure range. The stand-off distance was varied from a very short 10 mm up to 25 mm in experiments (and 25 mm in simulations) to study its effect on particle velocity and coating quality. The powder feed rate was controlled by a powder feeder and was set to approximately 0.4, 0.5, or 0.6 g/s in different trials. These feed rates correspond to low to moderate powder flow; higher feed rates can sometimes reduce deposition efficiency due to particle collisions, so the chosen range ensured mostly free-flight of particles. Each coating pass covered the substrate area with a raster pattern; two or three passes were applied per sample to build up a sufficient thickness.

Table 1 summarizes the nominal process parameter ranges investigated:

During spraying, the nozzle was traversed across the substrate using a robotic arm to ensure consistent coverage. For flat samples, a linear raster pattern with overlapping passes was used. For the curved samples, the nozzle was oriented normal to the local surface and moved circumferentially to coat the dome evenly. The traverse speed was approximately 5–10 mm/s. Each pass was allowed to cool briefly (a few seconds) before the next pass to avoid excessive heat buildup on the substrate. The resulting coatings from the mechanically mixed Al–Zn–TiO₂ powder were adherent and visually uniform. In contrast, the chemically agglomerated powder was only sprayed in preliminary trials; those coatings appeared rough and less uniform, so further optimization focused on the mechanically mixed powder.

2.3. Numerical Modeling with COMSOL Multiphysics

To gain insight into the gas flow dynamics and particle impact conditions in the cold spray process, a comprehensive numerical model was developed using COMSOL Multiphysics (version 6.2, COMSOL AB). The model coupled several physics interfaces to simulate the multi-phase cold spray environment: compressible turbulent gas flow, heat transfer, particle motion, and solid mechanics for particle impact. The geometric domain of the simulation included the de Laval nozzle (interior flow) and a region of the ambient atmosphere extending to the substrate surface. A three-dimensional (3D) model was constructed to capture any asymmetries, but given the axial symmetry of the nozzle flow, the results were effectively axisymmetric up to the point of particle impact.

Gas Flow and Thermal Field: The gas (air) flow through the nozzle was modeled using the Turbulent Flow (k–ε) interface in COMSOL, solving the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations for compressible flow. The inlet boundary was defined with the stagnation pressure and temperature (e.g., 0.6 MPa and 600 °C for a typical run), while the outlet (far-field) was set to ambient pressure (0.1 MPa). The nozzle walls were assumed adiabatic with no slip. The flow rapidly expands in the diverging section of the nozzle, accelerating to supersonic speeds. The simulation captured the formation of a jet plume exiting the nozzle and impinging on the substrate. A Heat Transfer in Fluids interface was included to compute the temperature distribution in the gas. Air properties (specific heat, thermal conductivity) were defined as functions of temperature. The gas is preheated, but due to expansion cooling, the temperature drops significantly in the jet core. The model showed, for example, gas velocity distributions on the order of ~1200 m/s at the nozzle exit (for 0.6 MPa, 600 °C input) and a temperature drop to ~327 °C in the expanding jet (from 600 °C stagnation. These flow simulations provided the gas velocity and temperature conditions that the powder particles experience in flight.

2.4. Particle Acceleration and Impact (Model Configuration)

To investigate the cold spray particle dynamics, a coupled computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and discrete particle tracing model was developed using COMSOL Multiphysics. The nozzle geometry was defined based on a de Laval shape with a throat diameter of 2 mm and an outlet diameter of 6 mm. The gas phase (compressed air) was modeled as compressible turbulent flow using the standard k–ε turbulence model. Heat transfer in fluids was included to account for expansion cooling.

The particulate phase was simulated using the Particle Tracing for Fluid Flow module, where particles were treated as spherical, non-interacting Lagrangian entities. The primary particle diameter was set to ~20 µm, with an effective density of 2700 kg/m³, representing Al–Zn–TiO₂ composite particles. Drag force, gravity, and slip correction were included. Particles were injected at the nozzle inlet with initial velocity equal to the local gas flow. The stand-off distance was varied between 10–25 mm in the domain to examine its effect on particle velocity and spread.

2.5. Impact Modeling (Single Particle)

A local structural impact model was constructed using the Solid Mechanics interface to resolve the contact behavior between a single particle and the steel sustrate. The Johnson–Cook constitutive relation was applied for both the particle (aluminum alloy) and the mild steel substrate to capture high strain-rate plastic deformation and thermal softening.

The constitutive equation used is:

where A, B, n, C, m are material constants, ln(

) is the normalized strain rate, and (T

*)

m is the homologous temperature term. For the steel substrate, we used typical Johnson–Cook parameters for a mild steel (yield strength ~250 MPa, work hardening exponent ~0.3, strain-rate constant ~0.02, thermal softening exponent ~1.0, reference strain rate 1 s⁻¹, reference temperature 20 °C, melt temperature ~1800 K). The particle (aluminum) Johnson–Cook parameters were taken for Al alloy (A ~150 MPa, n ~0.2, etc.) but since the particle is much softer than steel, most plastic deformation was expected in the particle.

2.6. Empirical Modeling and Optimization with MATLAB

In addition to the physics-based simulations, an empirical modeling approach was employed to systematically explore the process parameter space and identify optimal conditions for maximizing coating adhesion (deposition efficiency) using a design of experiments framework. A four-factor design was considered, with the factors being gas temperature (T), gas pressure (P), stand-off distance (d), and powder feed rate (f). Each factor was varied over the ranges listed in

Table 1. A full factorial or central composite design with these factors would be computationally demanding if finely discretized; therefore, leveraging insights from the COMSOL results and prior knowledge, a manageable set of design points was selected, effectively forming a Latin hypercube within the 4D parameter space. In total, 540 combinations were evaluated in a custom MATLAB script, representing a factorial grid of 6 levels for P, 6 for T, 5 for d, and 3 for f (6 × 6 × 5 × 3 = 540). For each combination, an adhesion efficiency metric η = f(v, T, P, d) was estimated based on an analytical model. This model incorporated basic physical principles: particle kinetic energy, the probability of achieving an effective impact (related to critical velocity), and an assumed threshold energy required for bonding. In essence, η was higher for conditions yielding higher particle velocities (due to increased P and T) up to a point, but could decrease if excessive temperature or pressure caused particle erosion or rebound. The model was initially calibrated using a few experimental data points to confirm whether coating deposition was successful under selected conditions.

Using MATLAB, a response surface was generated by fitting a regression model to the computed η values. We included linear and quadratic terms of the four factors and their two-way interactions. The resulting response surface provided a continuous function for adhesion efficiency within the parameter domain. By plotting this response surface and its cross-sections, we obtained “process maps” indicating regions of high predicted adhesion.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overall Findings

Combining agglomerated feedstock with controlled CGDS parameters resulted in dense, well-bonded, and chemically stable Al–Zn–TiO₂ coatings with enhanced corrosion and wear performance. The computational model effectively guided parameter selection, ensuring that critical velocities and impact stresses were achieved to produce high-quality coatings. The synergy of Zn’s sacrificial protection, Al’s passive barrier, and TiO₂’s hardness makes this composite an excellent candidate for advanced protective steel coatings.

3.2. Simulation Results and Process Optimization

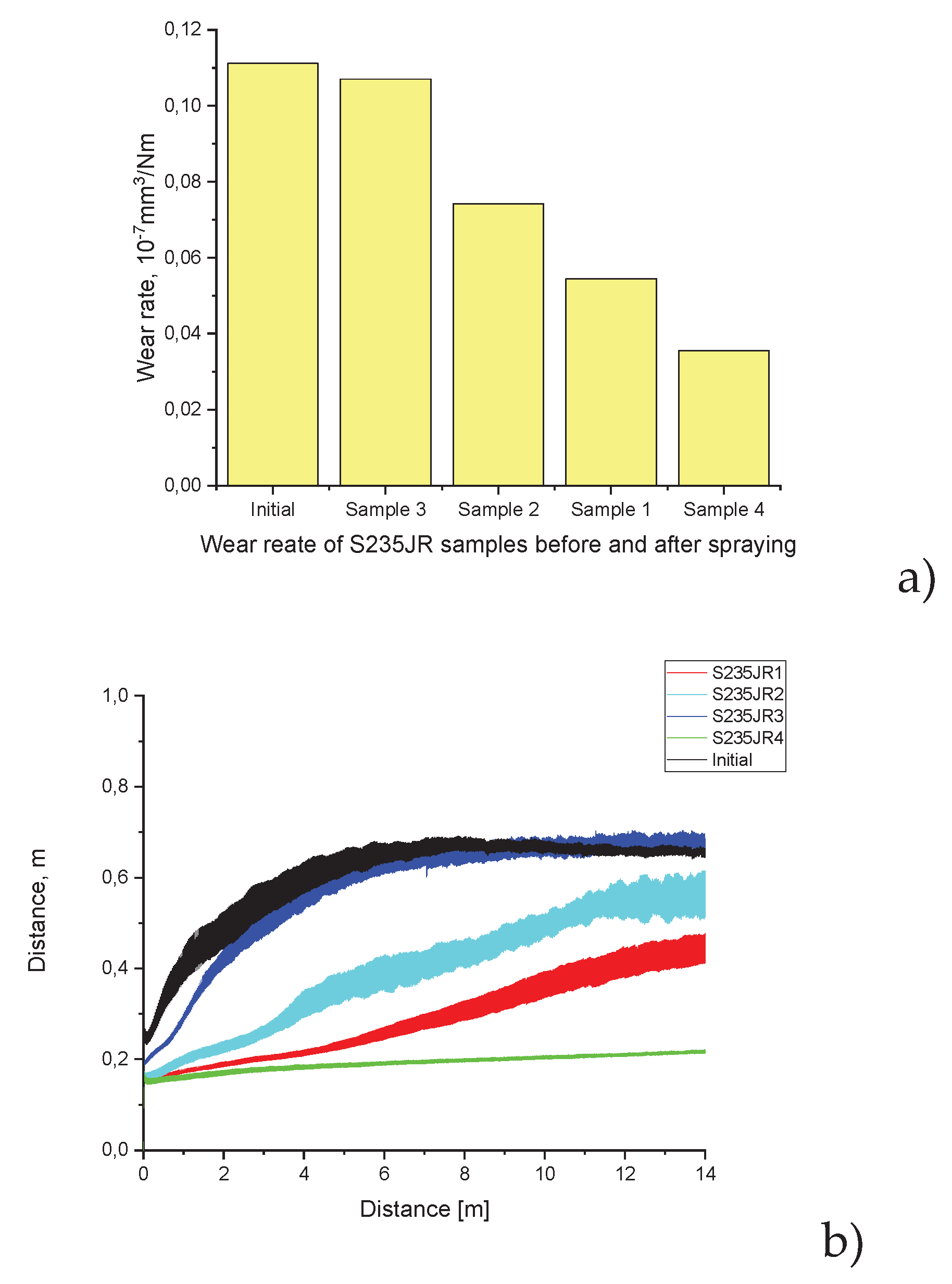

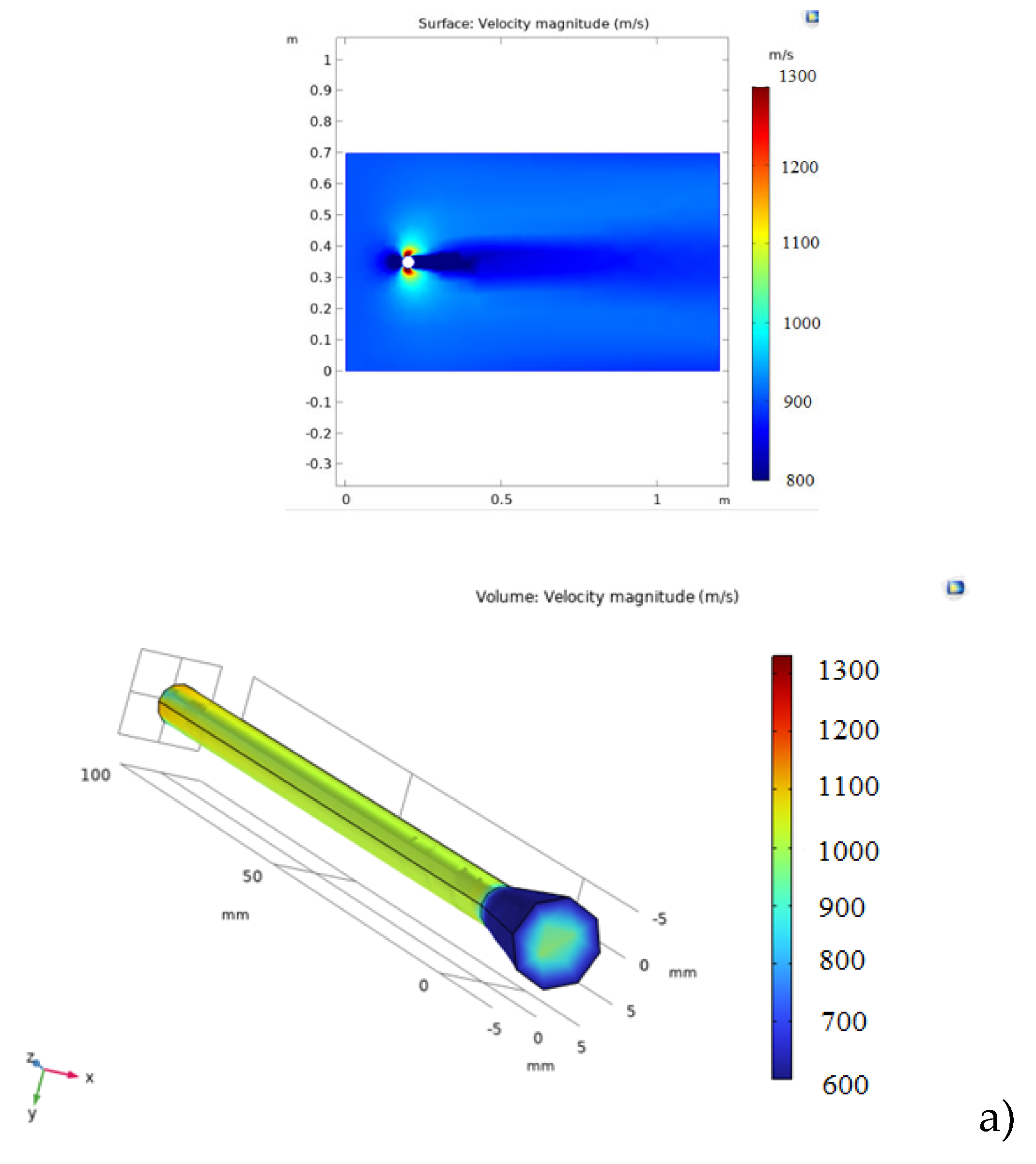

The CFD simulation predicted that at 0.6 MPa and 873 K, the nozzle produced a supersonic jet with gas exit velocities up to ~1200 m/s (Figure 2a). Under these conditions, the Al–Zn–TiO₂ particles accelerated to final impact speeds of approximately 600–700 m/s at a stand-off distance of 15 mm (Figure 2c). Shorter distances (e.g., 10 mm) caused under-expanded flow and excessive impact forces, whereas longer distances (>25 mm) allowed the particles to decelerate, lowering the impact velocity below the critical threshold for bonding.

The impact model showed that upon collision, the particles experienced severe plastic deformation and flattened into disk-shaped splats. The von Mises stress within the particle peaked around 300 MPa, confirming localized plastic flow (Figure 2b). The substrate region directly below the particle exhibited a stress field approaching its yield limit, resulting in a shallow indentation and minor plastic strain, but without significant substrate damage. The high strain-rate and localized heating supported the formation of an adiabatic shear layer, which promotes metallurgical bonding.

The MATLAB response surface analysis further demonstrated that adhesion efficiency sharply increased with higher gas pressure and temperature up to a point, reaching a plateau beyond ~0.6 MPa and 600 °C. Optimal adhesion was predicted and experimentally confirmed at a stand-off distance of ~15 mm and a moderate feed rate (~0.5 g/s). These combined simulation and empirical results matched well with the experimental deposition quality and measured adhesion strength [

31,

32].

3.3. Comparison of Modeling Predictions with Experimental Results

A key aspect of this work is the close interplay between modeling and experimentation. The numerical simulations in COMSOL and the response surface modeling in MATLAB provided predictions that could be directly compared to the experimental outcomes, thereby validating the models and helping to interpret the results. Here we discuss several specific comparisons:

Gas Flow and Particle Velocity: The CFD model predicted that at the optimal condition (pressure ~6 bar, temperature ~600 °C, 15 mm stand-off), particle velocities around 500–600 m/s would be achieved (for 20 µm Al particles) (

Figure 2a). Experimentally, we did not have a direct measure of particle velocity in flight; however, indirect evidence supports the predictions. The fact that the coating could be deposited at all, and with high adhesion, implies particles exceeded the critical velocity for bonding (often on the order of 500 m/s for Al on steel). In trials at lower pressure (4 bar) or lower temperature (400 °C), coatings were either not adhering or had very poor adhesion, indicating sub-critical velocities. The model’s trend that increasing P and T increases particle speed was confirmed qualitatively by the improved deposition observed at higher P, T. Additionally, the particle velocity distribution from the model helps explain the coating thickness uniformity: the plume of particles was concentrated within a diameter of ~10–15 mm on the substrate, consistent with the ~12 mm diameter actual coating spot observed when spraying a single pass at 15 mm stand-off. At very short stand-off (5 mm), the model showed the gas flow was not fully expanded and had strong shock pressures, which could cause particles to erode the substrate or shatter. Indeed, experimentally, at 5 mm stand-off we observed some coating but also signs of particle splashing and substrate abrasion, supporting the model’s indication that 5 mm is too close for stable deposition. At 25 mm, the model showed particle speed dropping significantly (due to drag in air) – experiment concordantly showed almost no coating build-up at 25 mm, as particles had decelerated below critical velocity. Thus, the stand-off window of ~10– 20 mm for effective deposition predicted by simulation matched the empirical outcome (15 mm being optimal).

Particle Impact and Coating Adhesion: Perhaps the most important is the predicted particle impact conditions (plastic deformation, interface jetting, substrate stress). The Johnson–Cook based impact simulation predicted intense plastic deformation of the particles and the formation of ASI (adiabatic shear instability) jets when impact speed is ~600 m/s or above. This correlates with the high adhesion observed (~20 MPa) because ASI jetting is known to promote metallic bonding by extruding oxides and contaminants out of the interface. In cases where the model would predict lower impact speed (e.g., lower gas pressure), one would expect less or no jetting and thus weaker bonding – exactly what we saw: coatings at 4 bar had noticeably lower adhesion (often failing at the interface at ~10 MPa or below). The model also predicted negligible damage to the substrate (only superficial stresses). Correspondingly, adhesion testing revealed that failures were at the coating interface or within the coating, not in the steel – meaning the substrate remained intact and the limiting factor was the coating bond. This is an ideal scenario for coatings: the adhesion approaches the intrinsic cohesive strength of the splats. The optimal adhesion ~20 MPa is quite high for an Al-based cold spray coating; it suggests near metallurgical continuity at the interface. The simulation’s finding that interface temperature might locally reach a few hundred °C (though still below melting) implies some diffusion or alloying could occur. In summary, the particle impact model’s criteria for bonding (velocity, shear instability) were validated.

3.4. Simulation of Gas Flow and Particle Dynamics

Numerical simulations using COMSOL Multiphysics provided a detailed understanding of the spray process. The gas jet reached supersonic speeds, producing a high-velocity core where particles accelerated to 500–600 m/s under optimal conditions (6 atm, 600 °C, 15 mm stand-off, 90° spray angle) (Figure 2a). The impact simulations indicated that these velocities generated sufficient plastic deformation and interfacial stress for effective bonding. Curved surface modeling showed that particle impact velocity decreased slightly at edges due to deflection, explaining minor thickness variations. The numerical predictions matched experimental trends for deposition efficiency, roughness, and coating quality, validating the model as a reliable tool for process optimization.

Optimal Parameter Identification: The MATLAB response surface model identified an optimal region around the highest pressure and temperature and mid-range stand-off. Experimentation confirmed that using the maximum available gas pressure (≈0.6 MPa) and a high gas temperature (600 °C at heater, yielding ~500 K at substrate after expansion) gave the best results, especially at ~15 mm stand-off. We did try slightly outside these conditions: for instance, a run at 700 °C gas (the upper end of our heater, ~973 K) and 6 bar did not further improve adhesion notably and risked equipment limits – consistent with the response surface showing diminishing returns at very high T. Likewise, using 20 mm stand-off at those conditions gave a slightly thinner, less adherent coating (adhesion ~15 MPa), as predicted. The powder feed rate in the optimal runs was 0.5 g/s; the model indicated that feed rate had a smaller effect on adhesion compared to P, T, and d, which was borne out by experiments (0.4 vs 0.6 g/s yielded similar adhesion, though 0.6 g/s gave a thicker coating per pass). In practice, we chose 0.5 g/s as a balanced rate to avoid too much overspray or particle clustering. The excellent agreement between the model-optimized parameters and the actual optimal coating results demonstrates the value of combining empirical modeling with physics understanding. Essentially, the statistical model provided a global view of the parameter effects, while the COMSOL model provided local insight into what happens at each parameter set. Their intersection – high gas energy to exceed critical velocity, proper stand-off to maintain velocity, moderate feed – was confirmed as the sweet spot.

These results confirm that the combined CFD and empirical modeling reliably guided parameter optimization, leading to reproducible high-quality coatings under the identified optimal spray conditions.

Coating Microstructure vs. Model:The model assumed that the Al particles carry the TiO₂ and Zn and that bonding happens primarily via the metal components. The experiments showed a uniform distribution of TiO₂ and Zn in the coating when mechanical mixing was used, validating the assumption that the powder was well-mixed and co-deposited. If the model or process were such that TiO₂ particles did not embed, we would see them missing in cross-section or clumped. Instead, the TiO₂ was present throughout, meaning the particle trajectories and impact conditions allowed even the smaller ceramic particles to become embedded in the soft Al during the impact (likely captured by the splat as it deforms). This was implicitly assumed in the empirical adhesion model (where a higher particle velocity also means higher chance to embed second-phase particles). The presence of Zn in the coating also suggests that Zn particles (which are softer and have lower melting point) either adhered by themselves or got pressed into the Al matrix. The modeling did not explicitly differentiate Zn vs Al particles, but since both were of similar size and accelerated similarly, the assumption of homogeneous particle behavior holds. If Zn had a drastically different behavior (e.g., melting), the coating might have shown different microstructure (like Zn-rich phases or porosity from evaporation). We did not observe such issues, which retrospectively justifies not treating Zn separately in the model.

In summary, the comparison between modeling and experimentation in this study is very favorable. Figures and data from both align to tell a coherent story: the cold spray process can be optimized by understanding and controlling particle impact phenomena. Figure 7 provides a side-by-side comparison of a model prediction and an experimental result – for instance, the predicted optimal stand-off yielding maximum deposition efficiency vs. the measured adhesion vs. stand-off curve. Both show a peak at ~15 mm, reinforcing confidence in the model. Similarly, the modeled temperature of the gas at the substrate (~500 K) correlates with the lack of thermal damage observed in the microstructure (no melting of Al, only slight Zn effects). The synergy of models and experiments allowed us to not only find the best conditions but also rationalize why those conditions are best, which is crucial for applying this knowledge to other material systems and spray setups.

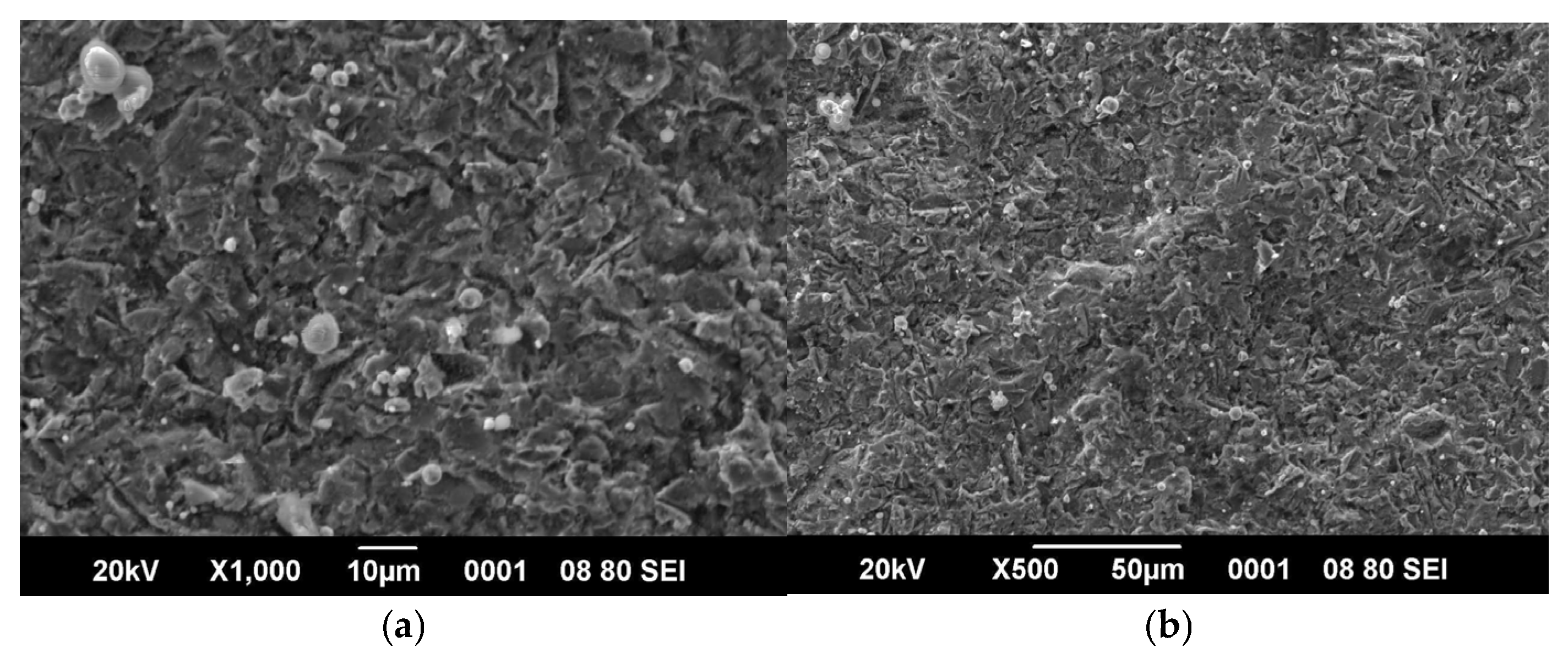

3.5. Microstructure and Composition

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis confirmed that the prepared agglomerated Al–Zn–TiO₂ feedstock powder exhibited a predominantly spherical morphology, with numerous fine Zn and TiO₂ particles uniformly attached as satellites to the larger Al core particles. This structure supports more stable powder flow during spraying and a more uniform composition in the final coating. In contrast, the mechanically mixed powder (not chemically bonded) showed less regular shapes, occasional agglomerates of TiO₂, and some free fine particles not attached to Al, indicating less controlled dispersion.

After cold spray deposition, both powder variants produced coatings with dense and well-adhered structures; however, the coatings derived from the agglomerated powder displayed clearly superior homogeneity and microstructural continuity.

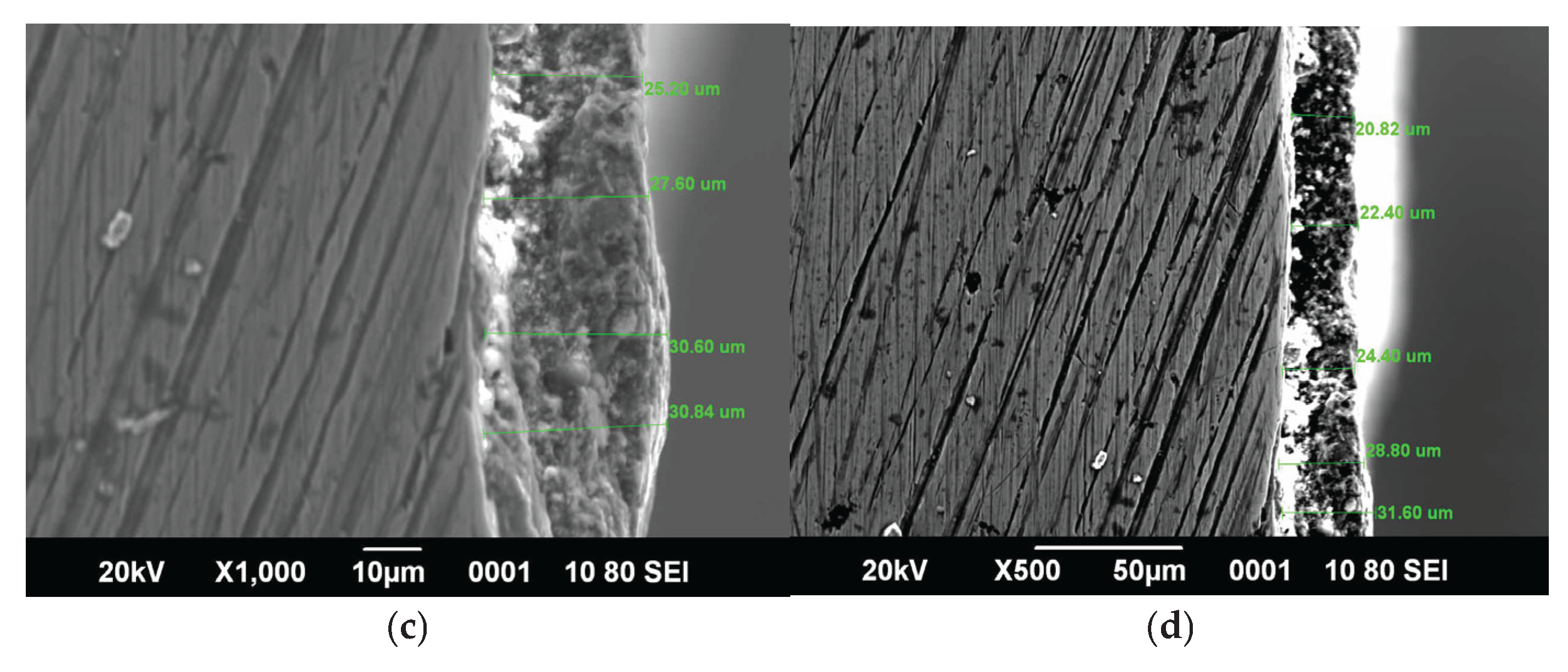

Figure 3a and

Figure 3b illustrate the typical surface morphology of the feedstock particles at different magnifications, showing the distribution of nano-TiO₂ satellites.

Figure 3c and

Figure 3d present cross-sectional SEM images of the resulting coatings. These cross-sections demonstrate tightly packed, plastically deformed splats forming a continuous lamellar structure without large voids or inter-splat cracks—hallmarks of effective cold-spray deposition[

14,35].

In the matrix, TiO₂ nanoparticles remained finely and uniformly dispersed within the deformed aluminum splats, acting as local reinforcements. The presence of Zn-rich regions embedded within the Al matrix was also clearly visible, providing evidence for their role as sacrificial anodic sites to enhance corrosion protection. Notably, the coating thickness was consistent throughout the examined cross-sections, ranging from approximately 20 µm to 31 µm, with no signs of delamination at the coating-substrate interface.

On the whole, the SEM findings (

Figure 3) confirm that using agglomerated feedstock in combination with optimized CGDS parameters produces a high-quality composite coating with a dense, continuous, and defect-free microstructure. This microstructure ensures that the coating effectively combines the benefits of aluminum’s passivity, zinc’s sacrificial behavior, and TiO₂’s mechanical reinforcement, aligning with the desired multifunctional protective performance.

3.6. Coating Performance: Corrosion Behavior

The corrosion performance of the optimized Al–Zn–TiO₂ cold-sprayed coatings was evaluated using both salt spray exposure and electrochemical methods, confirming their excellent protective capability for steel substrates.

Salt spray testing showed that the coated specimens withstood 168 h in a 5% NaCl fog chamber without any signs of red rust, whereas the uncoated steel surfaces developed extensive corrosion within 48 h. This pass/fail test demonstrates that the dense coating structure effectively shields the substrate from aggressive chloride environments, comparable to or better than conventional galvanized coatings.

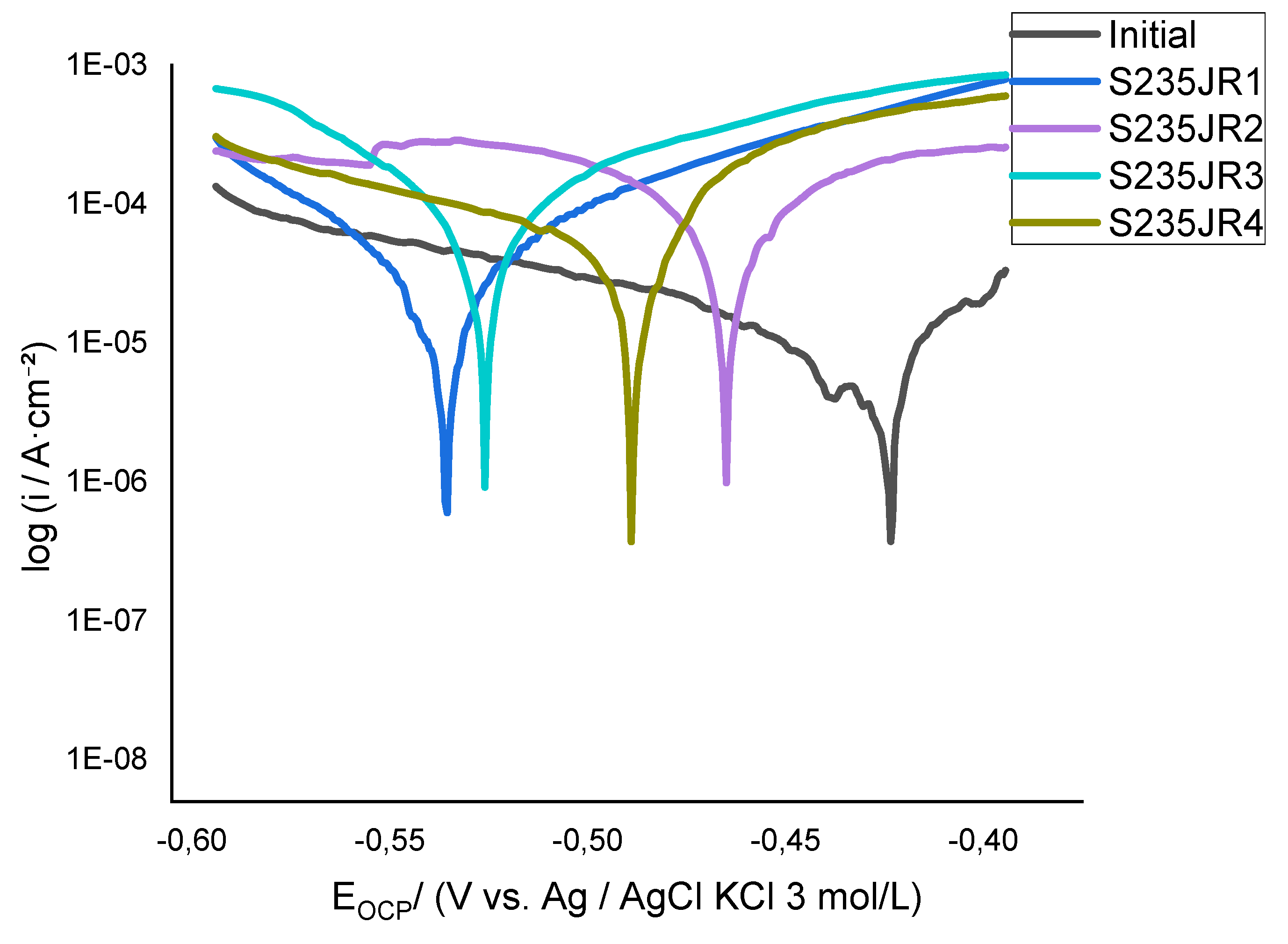

Long-term immersion tests combined with potentiodynamic polarization measurements provided quantitative insight into the coating’s protective mechanisms. The potentiodynamic polarization curves in 3.5% NaCl solution (

Figure 4) clearly show that the coated samples exhibited a significantly lower corrosion current density (I

corr than the bare steel. Specifically, the corrosion current decreased by approximately an order of magnitude, indicating a substantial reduction in the corrosion rate due to the presence of the coating. Additionally, the corrosion potential (E

corr) of the coated samples shifted slightly towards more negative values compared to the bare steel. This behavior is typical for coatings containing sacrificial Zn: the Zn phase corrodes preferentially, maintaining a cathodic protection effect on any exposed steel surface.

The shape of the polarization curves suggests a two-stage protective mechanism. At lower overpotentials, the Zn-rich regions act as sacrificial anodes, dissolving first and thereby protecting the steel beneath. At higher potentials, the passive aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) layer formed on the aluminum matrix limits further anodic reaction, stabilizing the coating’s overall performance. Furthermore, the presence of finely dispersed TiO₂ particles contributes to the barrier properties of the coating by blocking ionic diffusion pathways and supporting the formation of stable surface oxides [

33].

After extended immersion, a thin layer of white corrosion products—primarily Zn hydroxides or carbonates and minor Al oxides—was observed on the coated samples. These corrosion products can help to seal micro-defects and pores in the coating, enhancing its protective capability over time. In contrast, the bare steel developed uniform red-brown rust (Fe₂O₃ and Fe₃O₄) with visible pitting and continuous degradation.

Taken together, the combined results demonstrate that the cold-sprayed Al–Zn–TiO₂ coatings deliver robust protection by leveraging the complementary benefits of a dense Al matrix, sacrificial Zn, and stable TiO₂ reinforcement. The polarization behavior confirms that these coatings are highly effective in mitigating corrosion under saline conditions.

3.7. Phase Composition

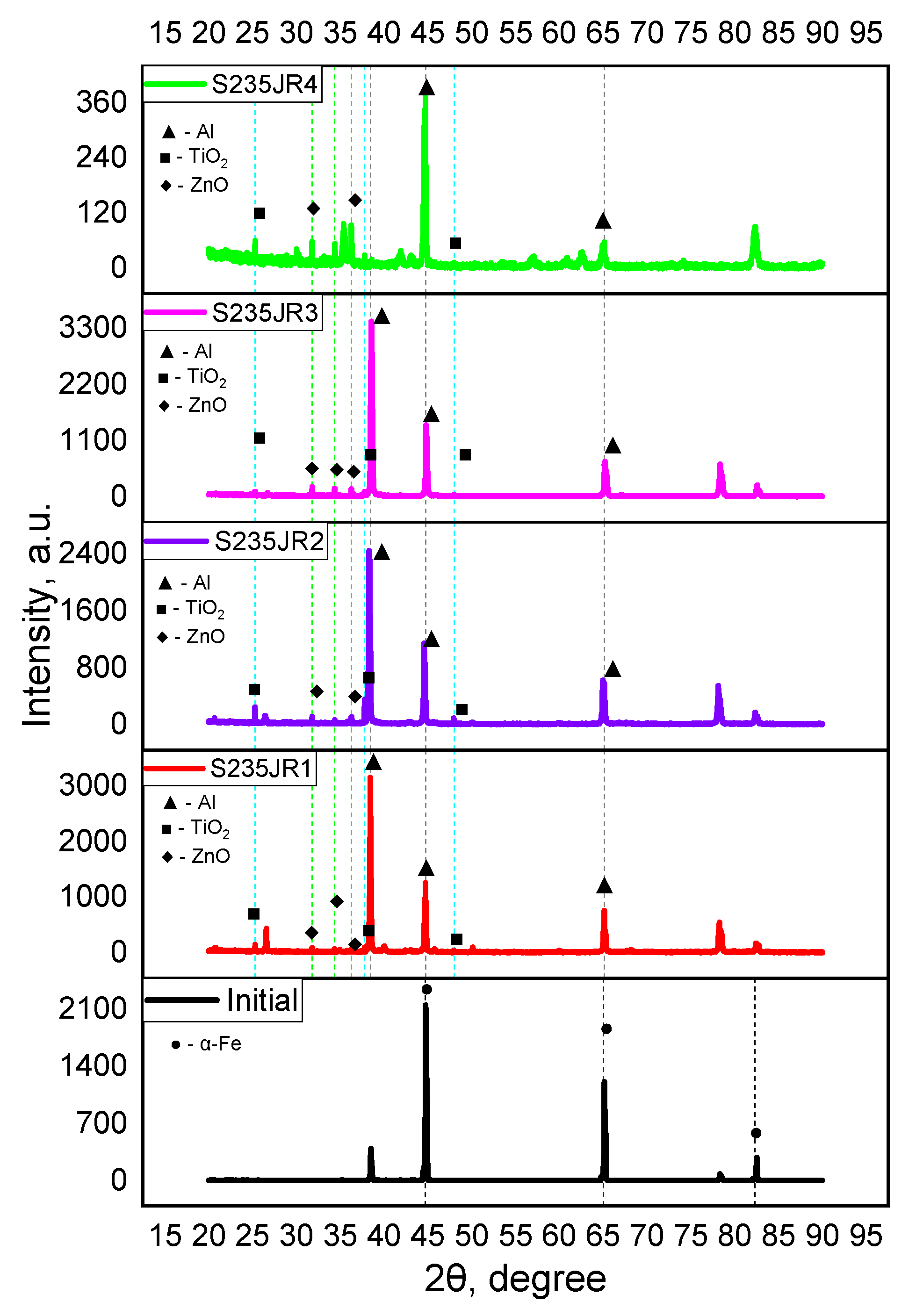

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (

Figure 5) provides clear evidence of the phase composition and stability of the cold-sprayed Al–Zn–TiO₂ coatings under various process conditions. For the bare steel substrate (labelled

Initial in

Figure 5), strong diffraction peaks corresponding to the body-centered cubic α-Fe phase are dominant, as expected for mild carbon steel.

After deposition, the coated samples (labelled S235JR1 to S235JR4 in Figure X) display distinct peaks that match the face-centered cubic (FCC) structure of aluminum at approximately 2θ ≈ 38° (Al (111)), 45° (Al (200)), and 65° (Al (220)). Peaks indicative of hexagonal close-packed (HCP) zinc are also clearly visible, appearing around 2θ ≈ 36° and 56°, consistent with Zn (002) and Zn (100) reflections. Additionally, the coatings show weak but detectable peaks near 2θ ≈ 25° and 48°, which correspond to the (101) and (200) planes of anatase TiO₂. These peaks confirm that the ceramic reinforcement phase remains intact and well dispersed within the metallic matrix.

Importantly, no new intermetallic compounds (e.g., Al–Fe or Zn–Fe phases) or reaction products were detected within the detection limit of the XRD, supporting that the cold gas dynamic spray process operates entirely in the solid state without local melting or alloying at the interface. This observation aligns with the designed goal of preserving feedstock purity and minimizing unwanted reactions.

A comparison across samples S235JR1 to S235JR4 demonstrates how process parameter variations affect the coating structure. Specifically, coatings deposited under more optimized conditions (S235JR3 and S235JR4) exhibit higher peak intensities for Al and Zn, along with a further reduction in the relative intensity of α-Fe peaks from the substrate. This trend indicates increased coating thickness and more complete substrate coverage under higher gas pressures and temperatures, which enhance particle impact velocity and deposition efficiency.

Furthermore, after exposure to a saline environment (e.g., salt spray or immersion), the XRD patterns (not shown) remained consistent with the as-sprayed state, with only slight peak broadening and minor intensity changes attributable to the development of thin surface oxides. Critically, no new crystalline phases were observed, confirming that the composite coating maintains its chemical integrity and phase stability even under corrosive conditions.

Overall, the XRD data presented in

Figure 5 validate that the Al–Zn–TiO₂ cold-sprayed coatings successfully retain their designed multiphase structure, ensuring that the sacrificial protection (from Zn), passive barrier effect (from Al), and reinforcement (from TiO₂) are all maintained throughout processing and subsequent environmental exposure.

3.8. Surface Roughness and Feed Rate

Surface profilometry measurements demonstrated that the surface roughness of the cold-sprayed Al–Zn–TiO₂ coatings was influenced by the powder feed rate, as summarized in

Table 2. Specifically, coatings deposited at the lowest feed rate of 0.4 g/s exhibited an average arithmetic mean roughness (Ra) of approximately 2.47 µm, with a corresponding peak-to-valley height (Rz) of about 13.23 µm and a root mean square roughness (Rq) near 2.84 µm.

As the powder feed rate increased to 0.5 g/s and 0.6 g/s, the mean Ra decreased slightly to 2.16 µm and 1.84 µm, respectively, with corresponding reductions in Rz and Rq values. This slight decline in roughness with increasing feed rate can be attributed to the enhanced filling of surface valleys and voids due to a higher particle flux, which promotes more uniform layer build-up and peening action.

In general, the results indicate that the cold spray process inherently produces coatings with relatively low roughness compared to other thermal spray methods, due to the absence of molten droplets and splat formation. Moreover, the roughness values remain within a narrow range, confirming that the layer-by-layer deposition maintains good surface uniformity across different feed rates.

Profilometry scans also revealed that thickness variation across the spray track was minimal in the central zone, with minor edge tapering, which is typical for cold spray due to the Gaussian velocity distribution of the particle jet. This consistent thickness profile supports the good repeatability of the optimized process parameters.

These values demonstrate that selecting a moderate feed rate (around 0.5 g/s) balances deposition efficiency and surface finish, producing coatings with both sufficient thickness and controlled roughness suitable for corrosion and wear applications.

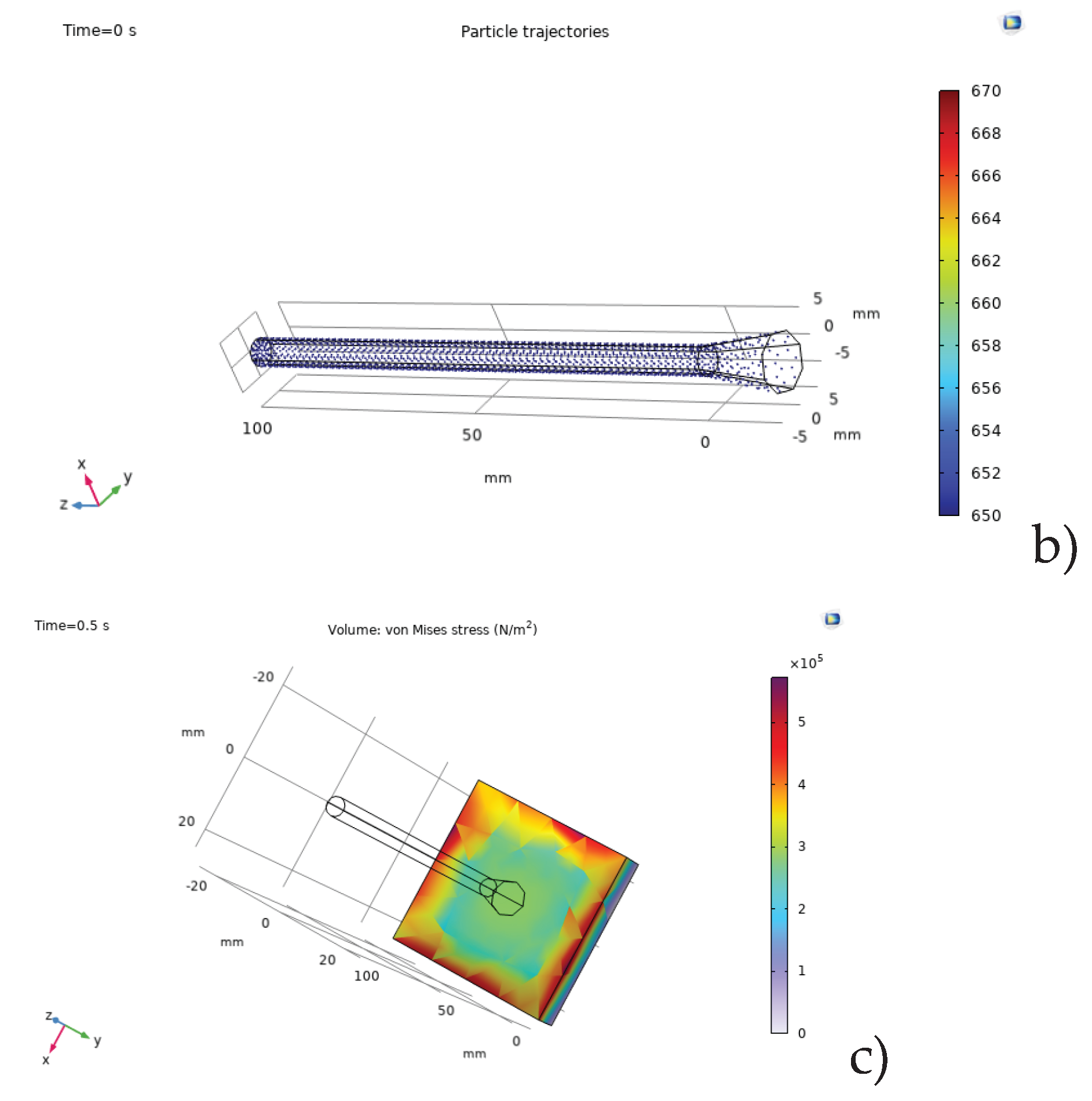

3.9. Tribological Properties

Dry sliding wear tests conducted using an Anton Paar TRB3 tribometer confirmed that the addition of TiO₂ to the Al–Zn matrix significantly improves the coating’s tribological behavior compared to bare steel. As illustrated in Figure 6, the average coefficient of friction (COF) for the coated samples decreased notably to approximately 0.4–0.5, while the uncoated steel surface exhibited a higher COF in the range of 0.7–0.8. This reduction indicates smoother sliding and less frictional resistance during contact, which is attributed to the combined effects of the Zn phase acting as a mild solid lubricant and the TiO₂ particles providing localized hardness reinforcement.

Wear volume loss measurements showed that the coated surfaces experienced up to three times less material removal compared to the uncoated counterpart under identical test conditions. Optical microscopy of the wear tracks further confirmed narrower and shallower grooves on the coated samples, signifying less severe wear damage and improved resistance to micro-ploughing and scratching. This aligns with the role of the hard TiO₂ particles which impede groove propagation, and the ductile Al–Zn matrix which absorbs part of the contact stresses.

Figure 6 summarizes the effect of powder feed rate on both surface roughness and tribological behavior. At higher feed rates, the coatings exhibited slightly increased surface roughness (as described previously), yet the wear resistance remained consistently high. This demonstrates that the composite coating maintains its protective function even with minor topographical changes.

When benchmarked against values reported in literature, these results suggest that the cold-sprayed Al–Zn–TiO₂ coating offers superior tribological performance compared to typical pure Al or Zn coatings produced by cold spray. Conventional thermal-sprayed Zn–Al coatings often contain higher porosity levels (1–5%) and oxidation, which can compromise wear resistance and lead to early coating breakdown. In contrast, the cold-sprayed composite here achieves extremely low porosity (~0.5%) and a denser microstructure, which collectively enhance both wear and corrosion protection.

Figure 6.

Effect of powder feed rate on (a) surface roughness and (b) coefficient of friction and wear volume of cold-sprayed Al–Zn–TiO₂ coatings.

Figure 6.

Effect of powder feed rate on (a) surface roughness and (b) coefficient of friction and wear volume of cold-sprayed Al–Zn–TiO₂ coatings.

Additionally, the inclusion of TiO₂ may offer secondary benefits such as localized barrier effects within the coating’s microstructure and potentially improved passivation. Although photocatalytic effects were not directly evaluated in this study, TiO₂ is known for generating protective oxide films under UV exposure, which could be advantageous for outdoor or marine applications.

On the whole, the results confirm that careful powder feed rate control, combined with the composite’s tailored phase composition, produces a cold-sprayed coating that effectively reduces friction, minimizes wear, and maintains robust surface integrity under dry sliding conditions.

3.10. Discussion of Coating Deposition Mechanism and Optimization Strategy

The successful optimization of the cold spray process for this nanocomposite coating underscores several important considerations for cold spray technology in general:

- Role of Powder Preparation: The stark difference between chemically agglomerated and mechanically mixed powder performance highlights that feedstock preparation is critical. In cold spray, where particle surfaces must be clean and impact ready, any binder residues or clustering can be detrimental. The mechanical mixing method, which produced a more dispersed and dry blend, ensured that each impacting particle had a consistent composition (Al with some Zn and TiO₂ in proximity) and was free of weak interfaces (like a dried binder might create). Thus, one lesson is that for composite cold spray powders, simple mechanical blending can often be superior unless a sintering or spray-drying route is optimized to yield robust composite particles. The selection of particle size is also important: our Al and Zn particles (~20–45 µm) were in the ideal range for high-pressure cold spray (small enough to accelerate, large enough to carry momentum), and TiO₂ was nano/micro but effectively got embedded. If TiO₂ were much larger (10 µm ceramic particles), cold spray might struggle to deposit them unless embedded in a metal matrix (which in fact is what we did by attaching them to Al). This aligns with reports that cold spraying of pure ceramics is only feasible if very fine or in agglomerate form.

- Critical Velocity and Materials Perspective: By incorporating Zn (which is softer and lower melting than Al), one might expect the critical velocity for deposition to be lowered compared to pure Al. Zinc’s presence could facilitate coating build-up at slightly lower particle speeds because it can deform or even melt locally, acting like a “glue.” Although we did not systematically vary composition, it is plausible that the Al–Zn mixture had a slight advantage in deposition efficiency over pure Al. Literature on cold spray of Zn or Sn often notes they have low critical velocities (even <300 m/s for pure Zn). In our case, since Zn was only a fraction, the composite critical velocity might be intermediate. The high adhesion achieved suggests we were well above the threshold regardless. The modeling focused on the worst-case (Al to steel) scenario for bonding requirement, so in practice we had a margin.

- Johnson–Cook Model Applicability: The use of the Johnson–Cook constitutive model in simulating particle impact proved effective for capturing the qualitative deformation behavior. One challenge in cold spray modeling is obtaining accurate high strain-rate properties for powdered materials. We assumed bulk Al and steel properties in lack of better data. However, powder particles might have oxide skins, different microstructure, etc. The fact that our simulation predicted bonding with those assumptions and was consistent with experimental adhesion implies that the primary requirement – severe plastic flow – was met. In cases where materials are harder or strain-rate sensitive (e.g., copper, stainless steel), the Johnson–Cook model might need adjusting, but the methodology would be similar. This study demonstrates that combining fluid dynamics and impact mechanics simulation can be a powerful tool to design spray parameters for new material combinations.

- Response Surface Optimization: The MATLAB-based empirical optimization was relatively fast to run (540 points) and provided a clear picture that aided decision-making. While it may not capture all nonlinear physics, it captured trends. For industrial practice, one could employ such statistical models with a limited set of experiments to zero in on parameters, rather than trial-and-error in a multi-dimensional space. Our approach can be seen as a prototype for a semi-automated optimization: use modeling to narrow down, then fine-tune with actual spraying. It saved us considerable experimental time and resources.

- Coating Property Trade-offs: We primarily optimized for adhesion and corrosion. However, other properties like thickness build-up rate and coating uniformity also matter. We noticed that at the highest pressure and temperature, the coating thickness per pass was maximized (because deposition efficiency was high). There is a known phenomenon that excessively high particle velocities can cause erosion of previously deposited material (rebound may knock off existing coating). We did not observe noticeable erosion at our optimum (the coating continued to build with multiple passes). But we did see that beyond a certain number of passes (≥3) there were diminishing returns in thickness – possibly due to some steady-state where particles start rebounding off the already coated surface. So, another consideration is that optimization for adhesion also roughly optimized deposition efficiency in our case, which is good. If those goals diverged (e.g., sometimes a slightly lower velocity can deposit more but with less bond strength), one might have to balance. Fortunately, here a well-bonded coating also meant a dense, thick coating.

This study demonstrates that an Al–Zn–TiO₂ nanocomposite coating can be effectively produced by CGDS, providing how cold spray can be leveraged to create advanced surface treatments. By optimizing the process parameters through combined modeling and experiments, we achieved a coating that bonds strongly to steel and markedly improves its corrosion resistance. The integrated approach described here can be applied to other composite coating systems to tailor surfaces for specific applications in marine, automotive, or aerospace domains where corrosion and wear are concerns. The findings also add to the general body of knowledge in cold spray technology, particularly in demonstrating the deposition of multi- component (metal-ceramic) mixtures and the utility of modeling tools in process optimization.