1. Introduction

Compression garments are clothing items designed to exert controlled mechanical pressure on body tissues, with pressure levels varying according to material characteristics and garment fit [

1]. Historically employed in medical settings to improve venous return, facilitate lymphatic circulation, and reduce edema [

2,

3,

4,

5], these garments have been extensively studied and clinically applied [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In recent years, the use of compression garments has progressively expanded into sports contexts, aiming to enhance performance, optimize post-exercise recovery [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] and reduce perceived exertion during intense physical activities [

22]. However, scientific evidence supporting their effectiveness remains controversial. Some meta-analyses and review studies have reported positive effects on recovery, including reductions in creatine kinase, delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), and blood lactate levels [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Conversely, other studies have found no significant differences in performance or physiological responses compared to traditional sportswear [

29,

30,

31]. Most research in this area has focused on the long-term effects (beyond 5 minutes) of compression garments, predominantly examining the lower limbs [

26,

32]. Consequently, findings cannot be unreservedly generalized to the upper limbs. Peripheral muscle oxygenation is among the most studied physiological variables related to compression, considered a key indicator of physical performance. During exercise, the balance between oxygen availability and muscular demand is crucial to delay fatigue onset [

33]. To date, only two randomized studies have investigated graduated compression garments for the upper limbs, involving continuous grip activities in climbing and competitive gaming, both showing increased SmO₂ during recovery [

34,

35]. Thanks to advancements in non-invasive technologies, such as near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), it is now possible to monitor muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂), expressed as a percentage, in real-time during various types of exercise [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Specifically, analyzing SmO₂ values during isometric contractions allows investigation of the relationship between metabolic demand and muscle oxygen availability [

41]. This study aimed to analyze the effects of compression garment use on muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂) recovery in the biceps brachii following brief maximal isometric contractions. In particular, physiological responses post-exercise were compared between two conditions (with and without compression garments). It was hypothesized that compression garments would promote faster and more efficient post-exercise muscle reoxygenation, thereby enhancing oxidative recovery compared to traditional clothing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 14 male adults, with a mean age of 24.4 years (± 2.68), mean height of 176.75 cm (± 6.96), body mass of 73 kg (± 7.34), and average biceps brachii circumference of 30.5 cm (± 2.6). Thirteen participants were right-arm dominant, and one participant was left-arm dominant. Participants were recruited based on specific inclusion criteria: regular participation in sports activities (at least three weekly sessions at moderate intensity, totaling at least 5 hours per week), and having a biceps brachii circumference between 25 and 35 cm. Subjects with a positive medical history or reported cardiovascular diseases, injuries, or physical conditions potentially influencing test performance, as well as those taking medications capable of altering performance or physiological responses, were excluded from the sample.

2.2. Procedures

Participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol consumption and intense training, and to maintain their usual dietary and consumption habits during the 24 hours prior to each experimental session. All subjects were informed about the study’s purpose and potential risks and provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Department of the Department of Human, Philosophical, and Educational Sciences at the University of Salerno (Protocol Number: 0186309). The entire experimental protocol was designed and supervised by the staff of the Laboratory for Innovative Teaching and Sports Performance Analysis at the Universi-ty of Salerno (Unisa). The tests were conducted in the gymnasium of the University Sports Center (CUS), under controlled environmental conditions (temperature: 22±2°C; relative humidity: 60%±2%) and between 9:00 AM and 2:00 PM. Each participant performed the different experimental conditions 48 hours apart, with environmental conditions and test times kept constant. The aim of the study was to analyze changes in muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂) in response to the use of compression garments during isometric exercises targeting the biceps brachii. A crossover experimental design was adopted with two conditions (Compression Garment, CG; Control, noCG), separated by a 48-hour wash-out period. The order of conditions was randomized using balanced blocks (1:1 ratio). Therefore, each participant participated in two experimental sessions. In the first condition (noCG), exercises were performed while wearing traditional sportswear without compression effects (

Figure 1a), whereas in the second condition (CG), the same protocol was carried out using a graduated compression garment provided by LB9 (

®LB9 BRAND S.R.L. Founded & Endorsed) (

Figure 1b). In the noCG condition, participants wore a placebo (“sham”) garment similar in fabric, color, and general appearance to the compression garment but without significant compression. Subjects were not informed about the actual difference between the two garments, thus limiting potential expectancy effects. The measurement of arm circumference was performed with the subject standing upright with the arm relaxed at the side, at the midpoint between the acromion and olecranon processes [

42].

Legend: (a) Performance of maximal isometric contraction of the biceps brachii in the no CG condition. (b) Performance of maximal isometric contraction of the biceps brachii in the CG condition.

Before each session, participants performed a standardized warm-up consisting of three sets of unilateral bicep curls with six repetitions at 50% of 1RM, separated by one minute of rest between sets, according to the protocol described by Zhao, Nishioka, and Okada [

43]. During each experimental condition, participants performed three maximal bilateral isometric bicep curl contractions, maintaining an elbow flexion angle of 90°, each lasting 10 seconds at 100% of maximum voluntary contraction [

44]. A passive recovery period of 180 seconds was provided between each trial [

45]. Muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂) was monitored in real-time during each trial using a near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) sensor positioned over the biceps brachii muscle.

2.3. Materials

To analyze the effects of compression garments on muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂), a compression garment (

®LB9 BRAND S.R.L. Founded & Endorsed) was used. The garment, made from 60% Nylon and 40% Spandex, size M, was designed to apply graduated compression along the upper limb. Specifically, the pressure recorded at the wrist was 24 mmHg, gradually decreasing along the forearm and subsequently increasing at the biceps brachii muscle, reaching 22.7 mmHg. These data were provided by the manufacturer of the compression garment. These values referred to an arm circumference of approximately 30 cm, corresponding to the average measurement within the analyzed sample, to ensure functional and homogeneous garment adaptation to arm morphology. This approach maintained consistent pressure levels among subjects and standardized the compressive effect on the target muscle. The detailed description of the compression garment and fabric characteristics, in accordance with recommendations by MacRae et al., facilitates replicability and comparison with previous studies, indirectly contributing to standardizing applied pressure during exercise. Non-invasive measurement of muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂) was performed using the MOXY

® device (Fortiori Design LLC, Hutchinson, MN, USA), based on continuous-wave near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). The sensor was applied to the biceps brachii muscle of the dominant side, consistent with scientific literature highlighting its sensitivity in reflecting oxygen consumption during muscular contractions [

46]. Positioning followed SENIAM guidelines [

47], as recommended by the sensor manufacturer, aligning the emitter and detectors parallel to muscle fibers. The sensor was secured using adhesive materials provided by the manufacturer. The device operates at four wavelengths (680, 720, 760, and 800 nm) to measure tissue light absorbance, calculating, through an adaptation of the Beer-Lambert law, the ratio of oxygenated hemoglobin and myoglobin to their total concentration [

38,

40]. This value is multiplied by 100 and expressed as a percentage, providing the SmO₂ value within a range of 0 to 100% [

48,

49]. The parameter enables real-time monitoring of skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism during exercise [

50,

51]. In addition to SmO₂, the device also measures total hemoglobin concentration (Thb), reflecting changes in local blood volume [

52]. The default sampling frequency is 0.5 Hz, allowing data acquisition at the four wavelengths for 80 consecutive cycles, producing an average output every 2 seconds [

38,

53]. The distances between the emitter and detectors are 12.5 mm and 25 mm, respectively, ensuring an estimated penetration depth of approximately 12.5 mm [

38,

54]. Adipose tissue thickness (ATT) at the biceps brachii was measured using skinfold calipers [

55]. Data were saved in the device’s internal memory and subsequently exported via the “Moxy Monitor Settings” application (version 1.5.5) for processing and analysis. default filter, automatically applied by the device manufacturer, was used to reduce signal noise.

2.4. Data Analysis

All SmO₂ values were normalized relative to baseline, defined as the stable value recorded during the rest period following the warm-up [

56]. Specifically, the mean of stable values recorded within a one-minute post-warm-up window was calculated. The recovery phase was defined as the 3-minute period following the peak desaturation. To analyze muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂) trends during the post-maximal isometric contraction recovery phase, five distinct metrics were applied. First, the Half-Recovery Time (HRT) was calculated, defined as the time required for SmO₂ to rise from the peak desaturation to 50% of the total amplitude between that point and baseline [

57,

58,

59]. Subsequently, the initial recovery slope was analyzed, calculated using ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression applied to the first 25 seconds of post-contraction resaturation [

60,

61]. The time constant (τ) was estimated by fitting a mono-exponential model to the resaturation curve. This parameter describes the overall recovery speed [

62] and reflects muscle oxidative capacity [

63]. Additionally, the overshoot amplitude was determined, defined as the difference between the maximum SmO₂ peak reached post-contraction and the baseline pre-exercise level [

59,

64] parameters were calculated separately for each participant, obtaining a single representative average value for each of the two experimental conditions. For each subject, the individual difference (Δ) between the means of the two conditions was calculated. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to verify that differences between experimental conditions met the assumption of normality, necessary for using parametric tests. For parameters meeting the normality assumption (p>0.05 on the Shapiro-Wilk test), the paired Student’s t-test was used, while the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed for parameters that did not meet this assumption, to compare the two conditions. The magnitude of effects observed with parametric tests was quantified using Cohen’s d index, interpreted as follows: 0.2 indicates a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 or greater a large effect. For the Wilcoxon test, the effect size index r (matched-pairs rank biserial correlation) was reported, with reference values of 0.1 for a small effect, 0.3 for a moderate effect, and 0.5 for a large effect. Finally, to ensure precise and robust evaluation of results, the mean difference (Δ) between the two conditions (No compression - Compression) was calculated. For variables exhibiting a normal distribution, the mean difference and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated using the parametric method based on the paired t-test. For variables not meeting the normality assumption, the median difference and 95% confidence interval were calculated using the exact Hodges-Lehmann method, consistent with the non-parametric Wilcoxon test. Additionally, the 95% confidence interval for the effect size indices (Cohen’s d or r) was calculated. Specifically, for calculating the confidence interval of index r, bootstrap resampling with 5000 iterations was employed, providing a precise and robust estimate of the non-parametric effect size, given the non-normal distribution of the analyzed variable. This analysis clearly highlighted the precision of observed effect estimates and thoroughly evaluated individual variability in response to compression. All statistical results were considered significant at p-values lower than 0.05. All analyses were performed using MATLAB-R2025a (Version 25.1, MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA)

3. Results

The measurement of the athlete’s skinfold thickness revealed a value below 12 mm, the accepted limit for using the NIRS device [

48], confirming the validity of obtained data and reliability of muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂) measurements.

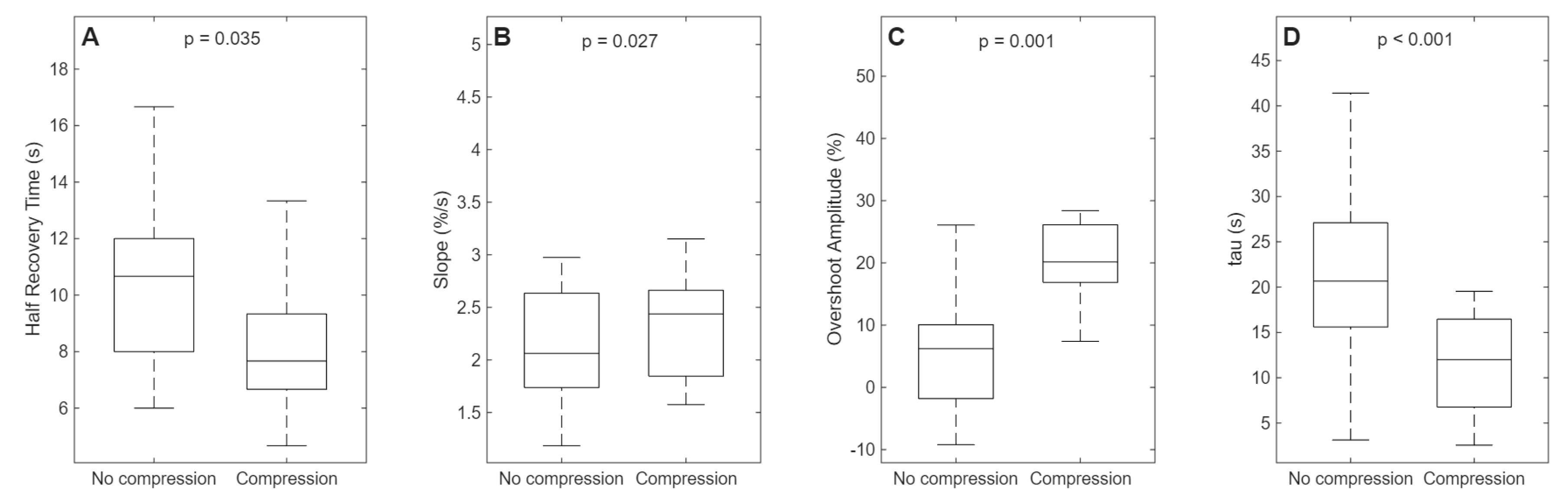

The comparison of Half-Recovery Time between the compression condition (8.52 ± 2.89 s) and the no compression control condition (10.21 ± 2.85 s) showed a mean difference of +1.69 ± 2.68 s (No compression – Compression), with a 95% confidence interval between +0.14 s and +3.24 s. This result robustly highlights an improved muscle recovery facilitated by compression garment use. The distribution of differences confirmed normality via the Shapiro–Wilk test (p = 0.182). Consequently, a paired t-test was applied, showing a statistically significant difference between conditions (p = 0.035) (

Figure 2A). The effect size, measured by Cohen’s d, was moderate (d = 0.63), with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.05 to 1.21, indicating individual variability in muscular response to compression.

The initial recovery slope of muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂) under the compression condition (2.43 ± 0.73 %/s) compared to the no compression condition (2.09 ± 0.57 %/s) demonstrated a mean difference of –0.34 ± 0.51 %/s (No compression – Compression), with a 95% confidence interval between –0.64 and –0.05 %/s, indicating a significant increase in the initial recovery speed favored by the compression garment. Again, the distribution confirmed normality (p = 0.207) and the paired t-test revealed a statistically significant difference (p = 0.027) (

Figure 2B). The effect size, measured by Cohen’s d, was moderate (d = 0.67), with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.09 to 1.24.

Overshoot Amplitude under the compression condition (21.40 ± 10.91%) compared to the no compression condition (7.92 ± 13.49%) showed a mean difference of –13.48 ± 12.50% (No compression – Compression), with a 95% confidence interval between –20.70% and –6.27%, robustly confirming the positive effect of the compression garment in increasing peak muscle oxygen saturation. This difference was normally distributed (p = 0.058). The paired t-test indicated a statistically significant difference between conditions (p = 0.0014) (

Figure 2C). The effect size, assessed via Cohen’s d, was large (d = 1.08), with a 95% confidence interval between 0.50 and 1.66.

The time constant τ under the compression condition (11.68 ± 5.41 s) compared to the no compression condition (21.04 ± 9.96 s) showed differences that did not meet the assumption of normality (p = 0.044). Consequently, the Hodges–Lehmann estimator (median of differences) was +6.90 s, with a 95% confidence interval between 4.22 and 11.65 s. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied, showing a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) (

Figure 2D). The effect size was expressed via rank-biserial correlation (r = 0.864); the related 95% CI was estimated through bootstrap resampling with 5000 iterations (0.780–0.881), ensuring a robust estimate of precision.

4. Discussion

The results obtained in this study show that the application of compression garments during maximal isometric exercises may have significant beneficial effects on several parameters related to muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂) recovery.

The significant reduction in Half-Recovery Time with compression garments (p=0.035, d=-0.63) suggests a faster muscle capability to restore baseline oxygenation levels. Physiologically, this can be attributed to improved efficiency of venous return and local blood flow, facilitating metabolite clearance and energy replenishment [

12,

65,

66].

The significant increase in Overshoot Amplitude (p = 0.0014, d = 1.08) observed with compression garments is particularly physiologically relevant, potentially reflecting enhanced peripheral vascular responses [

34,

66]. This phenomenon indicates a greater capacity of the vascular system to temporarily enhance oxygen availability, potentially improving local metabolic conditions post-exercise [

67]. This observation aligns with literature findings commonly reporting increased muscle saturation above resting levels after vigorous exercise. Compression use seems to amplify this effect. DiFrancisco-Donoghue et al. [

34], for example, documented that after 15 minutes of recovery with compression sleeves, forearm SmO₂ increased by about 9% above baseline values, an effect not observed without compression.

The higher initial recovery slope (initial slope, 0-25 s) of the SmO₂ recovery curve with compression (p=0.027, d=0.67) indicates increased initial speed in SmO₂ recovery, further supporting the notion that compression may facilitate immediate reperfusion of muscle tissue, offering potential advantages in muscle management and recovery post-intense activity. The close relationship between muscle reoxygenation and factors such as blood flow, metaboreflex response, and capillary dynamics may explain this finding. Specifically, enhanced blood flow and optimal oxidative enzyme activity in muscles are associated with improved post-exercise reoxygenation capability [

68,

69]. These results are consistent with findings from a previous study conducted on the lower limbs, which indicated a greater recovery slope of SmO₂ in the quadriceps using compression garments (t-test = 2.69, p = 0.021) compared to the control condition, suggesting enhanced O₂ delivery in the initial recovery seconds [

67].

The significantly lower time constant τ observed under compression garment conditions (p < 0.001, r = 0.864) further strengthens the interpretation related to faster metabolic recovery, suggesting that compression improves the speed at which muscles regain oxidative equilibrium post-exercise. This aligns with evidence indicating higher τ values correlate with reduced muscle oxidative capacity [

63].

Overall, these findings support the strategic use of compression garments in sports contexts, suggesting potential benefits for improving recovery between intense exercise sessions by facilitating more efficient muscle reoxygenation, potentially enhancing performance during physical activities [

23,

24]. The data from this study align with previous evidence documenting improved muscle reoxygenation following compression garment use during or after exercise [

34,

67]. However, other studies did not observe significantly different effects compared to conventional sportswear use [

70,

71,

72,

73]. Such discrepancies might be attributed to various factors, including sample characteristics, exercise modalities employed, and differing compression intensities [

1,

13,

74,

75].

The possible influence of the placebo effect in studies on compression garments should also be considered, as awareness of their potential benefits can shape participants’ expectations and consequently affect outcomes. Since compression garments exert noticeable pressure on the body, conducting blinded experiments with such clothing is challenging [

1,

17]. However, in the present study, a tight-fitting sports shirt was used as a control to reduce the placebo effect, potentially strengthening the reliability of the obtained results.

4.1. Limitations and Future Perspectives

A limitation of the present study is the small sample size (n=14), exclusively composed of male subjects, which restricts the generalizability of the conclusions to the broader population, particularly women, whose muscle tissue, body composition, and physiological responses to compression may differ significantly.

Future studies should therefore include larger and more diverse samples in terms of gender, age, and training levels to enhance the representativeness of findings. Additionally, investigating the effects of varying compression gradients and materials through dose-response analysis will be beneficial for better understanding the interaction between compression intensity and physiological adaptations.

5. Conclusion

The use of near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) enabled precise, non-invasive measurement of muscle oxygen saturation (SmO₂), providing insights into the immediate effects of compression garment usage following intense isometric exercises. The results obtained from this study significantly support the initial hypothesis, demonstrating that compression garments may enhance physiological parameters related to muscular oxidative recovery. Specifically, significant reductions in Half-Recovery Time, substantial increases in Overshoot Amplitude, greater initial recovery slope, and decreased time constant τ were observed, collectively suggesting more effective and rapid muscle reoxygenation. These physiological benefits could primarily stem from improved venous return efficiency and enhanced local metabolic response, thereby facilitating accelerated clearance of metabolites produced during intense muscular activity. In conclusion, the data suggest that compression garment usage may promote faster recovery and improved muscle reoxygenation efficiency following isometric contractions in the upper limbs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.B, F.C and E.S.; methodology, M.T.B, F.C and E.S.; software, M.T.B. and F.C. validation, R.V. and D.A.; formal analysis, M.T.B, and F.C.; investigation, M.T.B, F.C, E.S. and E.C.; resources, M.T.B, F.C, E.S. and E.C; data curation, M.T.B., F.C., D.A..; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.B, F.C., E.S., E.C., S.C., C.C.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, D.A.; supervision, R.V.; project administration, R.V.; funding acquisition, R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles set out by the Declaration of Helsinki. This study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the Department of Human, Philosophical, and Educational Sciences at the University of Salerno (Protocol Number: 0186309).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available at the following link: 10.6084/m9.figshare.29382446.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the participants for their voluntary participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- MacRae, B.; Cotter, J.; Laing, R. Compression Garments and Exercise. ports Med 2011, 815–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanaud, J. P.; Laroche, J. P.; Righini, M. The history and historical treatments of deep vein thrombosis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2013, 11, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Meara, S.; Cullum, N. A.; Nelson, E. A.; Dumvillle, J. C. Compression for venous leg ulcers (Cochrane review). Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2012, 11, 1465–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaseem, A.; Chou, R.; Humphrey, L. L.; Starkey, M.; Shekelle, P.; Physicians, C. G. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine 2011, 155, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, A. L.; Carati, C. J.; Piller, N. B. A systematic review of common conservative therapies for arm lymphoedema secondary to breast cancer treatment. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2007, 18, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partsch, H.; Winiger, J.; Lun, B. Compression stockings reduce occupational leg swelling. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery 2004, 30, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibegbuna, V.; Delis, K. T.; Nicolaides, A. N.; Aina, O. Effect of elastic compression stockings on venous hemodynamics during walking. Journal of vascular surgery 2003, 37, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurr, J. H.; Machin, S. J.; Bailey-King, S.; Mackie, I. J.; McDonald, S.; Smith, P. D. Frequency and prevention of symptomless deep-vein thrombosis in long-haul flights: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001, 357, 1485–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, H.; Matsubara, M.; Suzuki, K.; Morita, S.; Shinomiya, K. Prevention of pulmonary embolism by a foot sole pump. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery British Volume 2001, 83, 1130–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaragiri, S. V.; Lees, T. A. (2000). Elastic compression stockings for prevention of deep vein thrombosis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews(3). [CrossRef]

- Millour, G.; Lepers, R.; Coste, A.; Hausswirth, C. Effects of combining cold exposure and compression on muscle recovery: a randomized crossover study. Frontiers in Physiology 2025, 16, 1598075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broatch, J. R.; Bishop, D. J.; Halson, S. Lower Limb Sports Compression Garments Improve Muscle Blood Flow and Exercise Performance During Repeated-Sprint Cycling. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2018, 19, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wannop, J. W.; Worobets, J. T.; Madden, R.; Stefanyshyn, D. J. Influence of Compression and Stiffness Apparel on Vertical Jump Performance. Journal of strength and conditioning research 2016, 30, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stickford, A. S.; Chapman, R. F.; Johnston, J. D.; Stager, J. M. Lower-leg compression, running mechanics, and economy in trained distance runners. International journal of sports physiology and performance 2015, 10, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Bryers, J. J.; Clothier, P. J. The effect of leg compression garments on the mechanical characteristics and performance of single-leg hopping in healthy male volunteers. BMC sports science, medicine & rehabilitation 2015, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Y. Research Advancements in Humanoid Compression Garments in Sports. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2013, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driller, M. W.; Halson, S. L. The effects of wearing lower body compression garments during a cycling performance test. International journal of sports physiology and performance 2013, 8, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troynikov, O.; Wardiningsih, W.; Koptug, A.; Watson, C.; Oggiano, L. Influence of material properties and garment composition on pressure generated by sport compression garments. Procedia Engineering 2013, 60, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Creasy, R. H.; Edge, J. A. The effect of graduated compression stockings on running performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2011, 25, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascombe, B. J.; Hoare, T. K.; Sear, J. A.; Reaburn, P. R.; Scanlan, A. T. The effects of wearing undersized lower-body compression garments on endurance running performance. International journal of sports physiology and performance 2011, 6, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, B. K.; Kwon, Y. H.; Newton, R. U.; Shim, J.; Popper, E. M.; Rogers, R. A. ; . . . Kraemer, W. J. Evaluation of a lower-body compression garment. Journal of sports sciences 2003, 21, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, E.; Albano, D.; Benincasa, M. T.; Vastola, R. Influence of compression garments on perceived exertion during maximal isometric exercises. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise 2024, 19, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leabeater, A.; James, L.; Driller, M. Tight Margins: Compression Garment Use during Exercise and Recovery—A Systematic Review. Textiles 2022, 2, 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.; Kohn Cardoso, R.; Rombaldi, A. J. Post-exercise effectsof graduated compression garment use on skeletal muscle recovery and delayedonset muscle soreness: a systematic review. Motricidade 2018, 14, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F.; Gissane, C.; Howatson, G.; Van Someren, K.; Pedlar, C.; Hill, J. Compression Garments and Recovery from Exercise: A Meta-Analysis. Sports medicine 2017, 47, 2245–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqués-Jiménez, D.; Calleja-González, J.; Arratibel, I.; Delextrat, A.; Terrados, N. Are compression garments effective for the recovery of exercise-induced muscle damage? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Physiology & behavior 2016, 153, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Howatson, G.; Van Someren, K.; Leeder, J.; Pedlar, C. Compression garments and recovery from exercise-induced muscle damage: a meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine 2014, 48, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W. J.; Flanagan, S. D.; Comstock, B. A.; Fragala, M. S.; Earp, J. E.; Dunn-Lewis, C. H. ; . . . Maresh, C. M. Effects of a whole body compression garment on markers of recovery after a heavy resistance workout in men and women. Journal of strength and conditioning research 2010, 24, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, J.; Stade, M.; Morse, B.; Schick, E. Graded Compression Garments Worn During Resistance Exercise: Impact on Muscle Damage, Fatigue, and Oxygenation in Untrained Individuals. International Journal of Kinesiology and Sports Science 2022, 10, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, C. A.; Helal, L.; Da Silva, R. P.; Belli, K. C.; Umpierre, D.; Stein, R. Association of Lower Limb Compression Garments During High-Intensity Exercise with Performance and Physiological Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports medicine 2018, 48, 1859–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascombe, B.; Laursen, P.; Nosaka, K.; Polglaze, T. No effect of upper body compression garments in elite flat-water kayakers. European journal of sport science 2013, 13, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochmann, R. P. External compression increases forearm perfusion. Journal of applied physiology 2005, 99, 2337–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M. I. A brief review of the use of near infrared spectroscopy with particular interest in resistance exercise. Sports medicine 2007, 37, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiFrancisco-Donoghue, J.; Rothstein, A.; Jung, MK.; et al. Upper body compression wear improves muscle oxygenation following intense video game training: a randomized cross-over study among competitive gamers. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2023, 15, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limmer M, de Marées M and Roth R () Effects of Forearm Compression Sleeves on Muscle Hemodynamics and Muscular Strength and Endurance Parameters in Sports Climbing: A Randomized, Controlled Crossover Trial. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 888860. [CrossRef]

- Benincasa, M. T.; Serra, E.; Albano, D.; Vastola, R. Comparing muscle oxygen saturation patterns in swimmers of different competitive levels. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 2024, 24, 1920–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalamitros, A. A.; Semaltianou, E.; Toubekis, A. G.; Kabasakalis, A. Muscle oxygenation, heart rate, and blood lactate concentration during submaximal and maximal interval swimming. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2021, 3, 759925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, A.; Schmitz, R.; Erlacher, D. Near-infrared spectroscopy-derived muscle oxygen saturation on a 0% to 100% scale: reliability and validity of the Moxy Monitor. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, M.; Bieuzen, F.; Billaut, F. Muscle Oxygenation Rather Than VO2max as a Strong Predictor of Performance in Sprint Canoe–Kayak. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2018, 13, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, E. M.; O’Connor, W. J.; Van Loo, L.; Valckx, M.; Stannard, S. R. Validity and reliability of the Moxy oxygen monitor during incremental cycling exercise. European Journal of Sport Science. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Van Beekvelt MC, van Engelen BG, Wevers RA, Colier WN. In vivo quantitative near-infrared spectroscopy in skeletal muscle during incremental isometric handgrip exercise. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2002, 22, 210–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, K.; Eston, R. (Eds.). (2019). Kinanthropometry and exercise physiology. London, UK:: Routledge. (pp.107 -108).

- Zhao, H.; Nishioka, T.; Okada, J. Validity of using perceived exertion to assess muscle fatigue during resistance exercises. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthalib, M.; Millet, G. Y.; Quaresima, V.; Nosaka, K. Reliability of near-infrared spectroscopy for measuring biceps brachii oxygenation during sustained and repeated isometric contractions. Journal of biomedical optics 2010, 15, 017008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, L. R.; da Rocha, A. F.; de Carvalho, J. L.; Goncalves, C. A. Electromyographic evaluation of muscle recovery after isometric fatigue. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference 2010, 2010, 4922–4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinpõld, K.; Rannama, I. Oxygen Uptake and Bilaterally Measured Vastus Lateralis Muscle Oxygen Desaturation Kinetics in Well-Trained Endurance Cyclists. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H. J.; Freriks, B.; Merletti, R.; Stegeman, D.; Blok, J.; Rau, G.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Hagg, G. (2000). SENIAM Raccomandazioni Europee per l’elettromiografia di superficie. Torino: CLUT Edition.

- Barstow, T. Understanding near infrared spectroscopy and its application to skeletal muscle research. Journal of applied physiology. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design, F. (2015). Introduction to muscle oxygen monitor. Muscle Oxygen URL: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hub/188620/file-433442739-pdf/docs/moxy-ebook-intro-to-muscle-oxygen.pdf?t=1488816603832.

- Kirby, B. S.; Clark, D. A.; Bradley, E. M.; Wilkins, B. W. The balance of muscle oxygen supply and demand reveals critical metabolic rate and predicts time to exhaustion. Journal of applied physiology. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, B.; Quaresima, V. Near-infrared spectroscopy and skeletal muscle oxidative function in vivo in health and disease: a review from an exercise physiology perspective. Journal of biomedical optics. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Muthalib, M.; Quaresima, V. The use of near-infrared spectroscopy in understanding skeletal muscle physiology: recent developments. Philosophical transactions. Series A, Mathematical, physical, and engineering sciences 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterson, P.; Kirby, B.; Hasselmann, G.; Feldman, A. Muscle oxygen saturation rates coincide with lactate-based exercise thresholds. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, C. J.; Collison, J. ; C. E. Performance comparison of the MOXY and PortaMon near-infrared spectroscopy muscle oximeters at rest and during exercise. J Biomed Opt 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (2001). Kinanthropometry and exercise physiology laboratory manual (Vol. 1). London, UK: Routledge. Eston, R. G.; Reilly, T. (Eds.).

- Design, F. (2023). Using Moxy for Multimodal Fitness. Muscle Oxygen URL: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://188620.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/188620/documents/Multimodal%20Fitness.pdf?utm_campaign=muscle-oxygen-ebook&utm_medium=email&_hsenc=p2ANqtz--kMYYcgwH8tyAOJcbOcRH53cV383xswPzG4rOzGLgHLX-tMVJiO6Hn4yn_-Xfn2A6ejA8Tpx3A_f4AYVoy0EfN0TlP4wiH-LjXgbLBaJV598dSays&_hsmi=248580871&utm_content=248580871&utm_source=hs_automation.

- Arnold, J. I.; Yogev, A.; Nelson, H.; van Hooff, M.; Koehle, M. S. Muscle reoxygenation is slower after higher cycling intensity, and is faster and more reliable in locomotor than in accessory muscle sites. Frontiers in physiology 2024, 15, 1449384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rębiś, K.; Sadowska, D.; Starczewski, M.; Klusiewicz, A. Usefulness of Portable Device to Establish Differences in Muscle Oxygenation Between the Wingate Test and Graded Exercise Test: Effect of Gender on Anaerobic and Aerobic Capacity in Speed Skaters. Frontiers in physiology 2022, 13, 809864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, T. J.; White, A. E. M.; Nixon, D. G. D.; Gould, D. W.; Watson, E. L.; Smith, A. C. Characterising skeletal muscle haemoglobin saturation during exercise using near-infrared spectroscopy in chronic kidney disease. Clinical and experimental nephrology 2019, 23, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crenshaw, A. G.; Elcadi, G. H.; Hellstrom, F.; Mathiassen, S. E. Reliability of near-infrared spectroscopy for measuring forearm and shoulder oxygenation in healthy males and females. European journal of applied physiology 2012, 112, 2703–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, A.; Babraj, J. Impact of sprint interval training on post-fatigue mitochondrial rate in professional boxers. European journal of applied physiology 2025, 125, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankowski, R. T.; Niemeijer, V. M.; Jansen, J. P.; Spraakman, L.; Stam, H. J.; Praet, S. F. E. Oxygen delivery is not a limiting factor during post-exercise recovery in healthy young adults. Journal of exercise science and fitness 2017, 15, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RYAN, TERENCE EDWARD.; SOUTHERN, WILLIAM MICHAEL.; BRIZENDINE, JARED T.; MCCULLY, KEVIN K. Cambiamenti indotti dall’attività nel metabolismo del muscolo scheletrico misurati con spettroscopia ottica. Medicina e scienza nello sport e nell’esercizio 2013, 45, 2346–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavridis, K.; Petridou, A.; Chatzinikolaou, A.; Mougios, V. Oxygenation Kinetics of Three Quadriceps Muscles During Squatting Exercise in Trained Men. Sports (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 12, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, S. F.; Bishop, D. J.; Halson, S. L.; Broatch, J. R. Compression-induced improvements in post-exercise recovery are associated with enhanced blood flow, and are not due to the placebo effect. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 16762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Lao, T.T.; Kwok, Y.L.; Li, Y.; Ying, M.T.C. Effects of graduated compression stockings with different pressure profiles on lower-limb venous structures and haemodynamics. Adv Therapy. 2008, 25, 465–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Lo, S.; Wu, H.; Chiu, M. Effects of compression garment on muscular efficacy, proprioception, and recovery after exercise-induced muscle fatigue onset for people who exercise regularly. PLoS One. 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kime, R.; Karlsen, T.; Nioka, S.; Lech, G.; Madsen, Ø.; Sæterdal, R. . & Stray-Gundersen, J. Discrepancy between cardiorespiratory system and skeletal muscle in elite cyclists after hypoxic training. Dynamic Medicine 2003, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Puente-Maestu, L.; Tena, T.; Trascasa, C.; Pérez-Parra, J.; Godoy, R.; García, J. M.; Stringer, W. W. Training improves muscle oxidative capacity and oxygenation recovery kinetics in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. European journal of applied physiology 2003, 88, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rennerfelt, K.; Lindorsson, S.; Brisby, H.; Baranto, A.; Zhang, Q. Effects of Exercise Compression Stockings on Anterior Muscle Compartment Pressure and Oxygenation During Running: A Randomized Crossover Trial Conducted in Healthy Recreational Runners. Sports Med 2019, 49, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Book, J.; Prince, C. N.; Villar, R.; Hughson, R. L.; Peterson, S. D. Investigating the impact of passive external lower limb compression on central and peripheral hemodynamics during exercise. European journal of applied physiology 2016, 116, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménétrier, A.; Mourot, L.; Bouhaddi, M.; Regnard, J.; Tordi, N. Compression sleeves increase tissue oxygen saturation but not running performance. International journal of sports medicine 2011, 32, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperlich, B.; Haegele, M.; Achtzehn, S.; Linville, J.; Holmberg, H. C.; Mester, J. Different types of compression clothing do not increase sub-maximal and maximal endurance performance in well-trained athletes. Journal of sports sciences 2010, 28, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy-Williams, N.; Fell, J.; Halson, S.; Kitic, C.; Driller, M. Pressure gradient differences between medical grade and sports compression socks. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2021, 112, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Howatson, G.; van Someren, K.; Davidson, S.; Pedlar, C. The variation in pressures exerted by commercially available compression garments. Sports Engineering 2015, 18, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).