Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

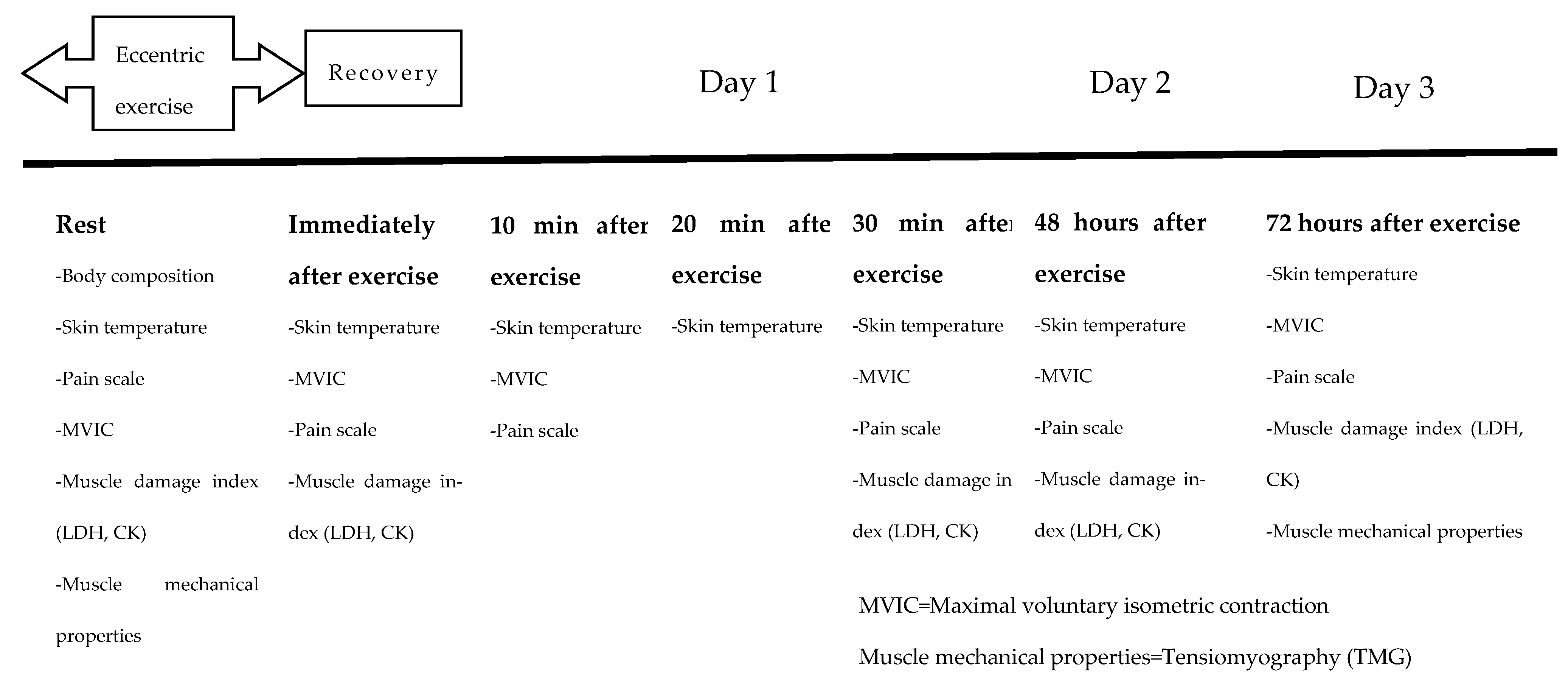

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Skin Temperature

2.4. MVIC

2.5. Pain Score

2.6. Muscle Damage Indices

2.7. Muscle Mechanical Properties

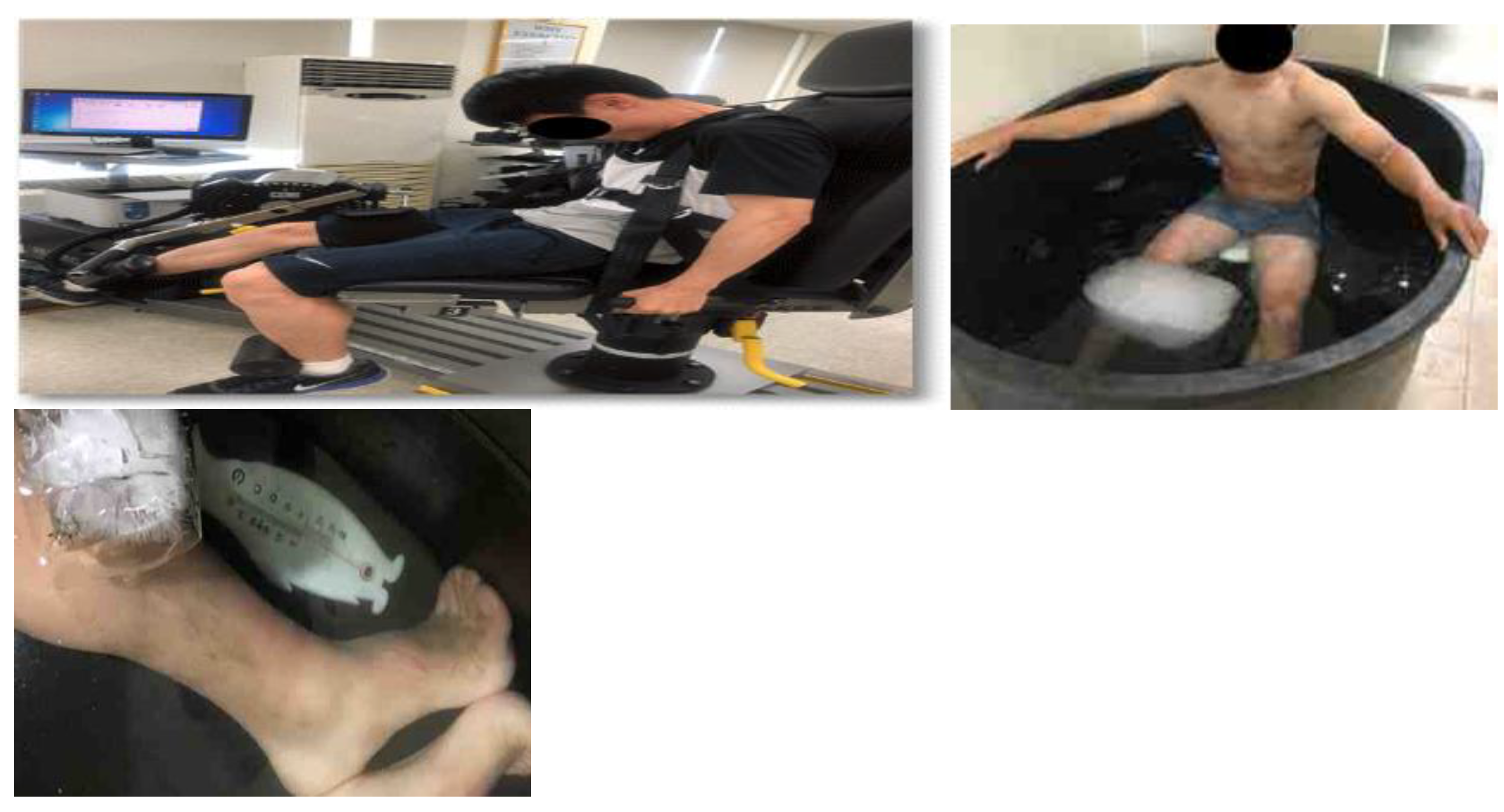

2.8. Eccentric Exercise Protocol

2.9. Whole-Body and Lower-Body CWI, and Active Recovery Treatment Protocols

2.10. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Body Composition

3.2. Changes Average Skin Temperature

3.3. Changes in MVIC

3.4. Changes in Pain Scale

3.5. Muscle Damage Indices

3.6. Changes in Muscle Mechanical Properties

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Quality and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CWI | Cold Water Immersion |

| MVIC | Maximum Voluntary Isometric Contraction |

| CK | Creatine Kinase |

| LDH | Lactate DeHydrogenase |

| TMG | Tensiomyography |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| Dm | Muscle's maximum travel Distance |

| HRmax | MAXimum Heart Rate |

| TC | Contraction Time |

| TR | Relaxation time |

References

- Tuxtaevich, A.T. Physiological Mechanisms and patterns of recovery process in sports. Frontline Medical Sciences and Pharmaceutical Journal 2023, 3, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masodsai, K.; Chaunchaiyakul, R. Dynamic Cardiopulmonary and Metabolic Functions during Jogging with and without Breast Supports. Journal of Exercise Physiology Online 2022, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D.; Edge, J.; Thomas, C.; Mercier, J. Effects of high-intensity training on muscle lactate transporters and post-exercise recovery of muscle lactate and hydrogen ions in women. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2008, 295, R1991–R1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; D'Silva, A.; Bhuva, A.; Lloyd, G.; Manisty, C.; Moon, J.C.; Hughes, A.D. Improved exercise-related skeletal muscle oxygen consumption following uptake of endurance training measured using near-infrared spectroscopy. Frontiers in Physiology 2017, 8, 299464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Meng, L.; Zhu, H.; Wan, L.; Chen, F. Effect of Normobaric Oxygen Inhalation Intervention on Microcirculatory Blood Flow and Fatigue Elimination of College Students After Exercise. Frontiers in Genetics 2022, 13, 901862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, J.M.; Roberts, L.A.; Figueiredo, V.C.; Egner, I.; Krog, S.; Aas, S.N.; Raastad, T. The effects of cold water immersion and active recovery on inflammation and cell stress responses in human skeletal muscle after resistance exercise. The Journal of physiology 2017, 595, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandvoort, C.S.; De Zwart, J.R.; Van Keeken, B.L.; Viroux, P.J.; Tiemessen, I.J. A customised cold-water immersion protocol favours one-size-fits-all protocols in improving acute performance recovery. European Journal of Sport Science 2018, 18, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, F.N.; Vanderlei, L.C.M.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Bertollo, M.; Godoy, M.F.; Hoshi, R.A. Effects of cold water immersion and active recovery on post-exercise heart rate variability. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2012, 33, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemann, E. Muscle Exercise. In Whole-Body Cryostimulation: Clinical Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcgorm, H.; Roberts, L.; Coombes, J.; Peake, J. Cold water immersion: Practices, trends and avenues of effect. Aspetar Sports Medicine Journal 2015, 4, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.E.; Wells, G.D. Cold-water immersion and other forms of cryotherapy: Physiological changes potentially affecting recovery from high-intensity exercise. Extreme physiology & medicine 2013, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, R.; Tizar, E.; Tizar, G.R. The Effect of Cold-Water Immersion Application on Biochemical Parameters in Athletes. International Archives of Medical Research 2024, 16, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubkowska, A.; Szygula, Z.; Klimek, A.J.; Torii, M. Do sessions of cryostimulation have influence on white blood cell count, level of IL6 and total oxidative and antioxidative status in healthy men? European Journal of Applied Physiology 2010, 109, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rech, N.; Bressel, E.; Louder, T. Predictive ability of body fat percentage and thigh anthropometrics on tissue cooling during cold-water immersion. Journal of Athletic Training 2021, 56, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimpchen, J.; Wagner, M.; Ferrauti, A.; Kellmann, M.; Pfeiffer, M.; Meyer, T. Can cold water immersion enhance recovery in elite Olympic weightlifters? An individualized perspective. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2017, 31, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Christophe, H. Conditioning recovery strategy to improve exercise performance (Korean edition): Seoul, South korea, 2017; pp. 105–122.

- Sarkar, S.; Debnath, M.; Das, M.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Dey, S.K.; Datta, G. Effect of high intensity interval training on antioxidant status, inflammatory response and muscle damage indices in endurance team male players. Sports Medicine 2021, 56, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska, M.; Mila-Kierzenkowska, C.; Boraczyński, T.; Boraczyński, M.; Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Sutkowy, P.; Woźniak, A. The influence of ambient temperature changes on the indicators of inflammation and oxidative damage in blood after submaximal exercise. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassit, R.A.; Pinheiro, C.H.D.J.; Vitzel, K.F.; Sproesser, A.J.; Silveira, L.R.; Curi, R. Effect of short-term creatine supplementation on markers of skeletal muscle damage after strenuous contractile activity. European journal of applied physiology 2010, 108, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, P.; Lippi, G.; Maffulli, N. Biochemical markers of muscular damage. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine 2010, 48, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Manso, J.M.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, D.; Rodríguez-Matoso, D.; de Saa, Y.; Sarmiento, S.; Quiroga, M. Assessment of muscle fatigue after an ultra-endurance triathlon using tensiomyography (TMG). Journal of sports sciences 2011, 29, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pišot, R.; Narici, M.V.; Šimunič, B.; De Boer, M.; Seynnes, O.; Jurdana, M.; Mekjavić, I.B. Whole muscle contractile parameters and thickness loss during 35-day bed rest. European journal of applied physiology 2008, 104, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, E.; Lago-Penas, C.; Lago-Ballesteros, J. Tensiomyography of selected lower-limb muscles in professional soccer players. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2012, 22, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenčič, V.; Knez, N. Measuring of skeletal muscles' dynamic properties. Artificial organs 1997, 21, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiffer, J.J.; Abbiss, C.R.; Nosaka, K.; Peake, J.M.; Laursen, P.B. Effect of cold water immersion after exercise in the heat on muscle function, body temperatures, and vessel diameter. Journal of science and medicine in sport 2009, 12, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, H.; Wijayanto, T.; Tochihara, Y. Neuromuscular function during knee extension exercise after cold water immersion. Journal of physiological anthropology 2017, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, S.C.; Shao, J.; Wang, H.; Lokhnygina, Y. Sample size calculations in clinical research. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan, N.L. A new weighting system for mean surface temperature of the human body. Journal of applied physiology 1964, 19, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkowitz, D.M. Improvement in isometric strength of the quadriceps femoris muscle after training with electrical stimulation. Physical therapy 1985, 65, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascensão, A.; Leite, M.; Rebelo, A.N.; Magalhäes, S.; Magalhäes, J. Effects of cold water immersion on the recovery of physical performance and muscle damage following a one-off soccer match. Journal of sports sciences 2011, 29, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Diaz, P.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Ramon, S.; Marin, M.; Steinbacher, G.; Rius, M.; Cugat, R. Comparison of tensiomyographic neuromuscular characteristics between muscles of the dominant and non-dominant lower extremity in male soccer players. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2016, 24, 2259–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Melick, N.; Meddeler, B.M.; Hoogeboom, T.J.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.; van Cingel, R.E. . How to determine leg dominance: The agreement between self-reported and observed performance in healthy adults. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Križaj, D.; Šimunič, B.; Žagar, T. Short-term repeatability of parameters extracted from radial displacement of muscle belly. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2008, 18, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenčič, V.; Knez, N. Measuring of skeletal muscles' dynamic properties. Artificial organs 1997, 21, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Manso, J.M.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, D.; Rodríguez-Matoso, D.; de Saa, Y.; Sarmiento, S.; Quiroga, M. Assessment of muscle fatigue after an ultra-endurance triathlon using tensiomyography (TMG). Journal of sports sciences 2011, 29, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, C.; Eston, R.G.; Edwards, R.H.T. Characteristics of isometric and dynamic strength loss following eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 2001, 11, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiffer, J.J.; Abbiss, C.R.; Watson, G.; Nosaka, K.; Laursen, P.B. Effect of cold-water immersion duration on body temperature and muscle function. Journal of sports sciences 2009, 27, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, H.C.; Peiffer, J.J.; Lopes-Silva, J.P.; Mesquita, R.N.; Amano, T.; Kondo, N.; Abbiss, C.R. Effect of ice slushy ingestion and cold water immersion on thermoregulatory behavior. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.M.; Sharpe, K.; Gore, C.; Miller, J.; Slater, G.J.; Versey, N.; Halson, S.L. Core temperature responses to cold-water immersion recovery: A pooled-data analysis. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2018, 13, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.S.; Kim, K.J.; Chun, B.O.; Lee, K.H.; Noh, J.H. The effect of cooling tubing intervention on recovery in elite wrestler competition simulation. Exercise Science 2019, 28, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, C.H.; Allan, R.; Drust, B.; Close, G.L.; Jeong, T.S.; Bartlett, J.D.; Gregson, W. Passive and post-exercise cold-water immersion augments PGC-1α and VEGF expression in human skeletal muscle. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2016, 116, 2315–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenauer, E.; Costello, J.T.; Deliens, T.; Clarys, P.; Stoop, R.; Clijsen, R. Partial-body cryotherapy and cold-water immersion after muscle damage in females. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 2020, 30, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.S.; Ting, K.H.; Hon, M.; Fung, N.Y.; Choi, M.M.; Cheng, J.C.; Yeung, E.W. Effects of cold water immersion on muscle oxygenation during repeated bouts of fatiguing exercise: A randomized controlled study. Medicine 2016, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J. Effects of post-exercise cold-water immersion on resistance training-induced gains in muscular strength: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Sport Science 2023, 23, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleakley, C.M.; Davison, G.W. What is the biochemical and physiological rationale for using cold-water immersion in sports recovery? A systematic review. British journal of sports medicine 2010, 44, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broatch, J.R.; Petersen, A.; Bishop, D.J. Postexercise cold water immersion benefits are not greater than the placebo effect. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2014, 46, 2139–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.A.; Nosaka, K.; Coombes, J.S.; Peake, J.M. . Cold water immersion enhances recovery of submaximal muscle function after resistance exercise. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2014, 307, R998–R1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, T.; Crisp, A.; Lopes, C.; Crepaldi, M.; Calixto, R.; Pereira, A.; Verlengia, R. Effect of eccentric velocity on muscle damage markers after bench press exercise in resistance-trained men. Gazzetta Medica Italiana 2015, 174, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hammouda, O.; Chtourou, H.; Chahed, H.; Ferchichi, S.; Kallel, C.; Miled, A.; Souissi, N. Diurnal variations of plasma homocysteine, total antioxidant status, and biological markers of muscle injury during repeated sprint: Effect on performance and muscle fatigue—A pilot study. Chronobiology international 2011, 28, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, B.; McNaughton, L.; Davoren, B. Circadian rhythms have no effect on cycling performance. International journal of sports medicine 1997, 18, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.M.; Erith, S.J.; Griffin, P.J.; Dowson, A.; Brewer, D.S.; Gant, N.; Williams, C. Influence of cold-water immersion on indices of muscle damage following prolonged intermittent shuttle running. Journal of Sports Sciences 2007, 25, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenauer, E.; Costello, J.T.; Deliens, T.; Clarys, P.; Stoop, R.; Clijsen, R. Partial-body cryotherapy and cold-water immersion after muscle damage in females. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 2020, 30, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.; Siqueira, A.F.; Ferreira-Junior, J.B.; do Carmo, J.; Durigan, J.L.Q.; Blazevich, A.; Rodrigues, P.; Wassmansdorf, R.; Salgueirosa, F.M.; Hernandez, S.G.; Nascimento, V.B.; Daros, L.B.; Osiecki, R. Time-course of changes in indirect markers of muscle damage responses following a 130-km cycling race. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano 2016, 18, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.; Rocha, P.; Torres, R. Cold-Water Immersion Has No Effect on Muscle Stiffness after Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 2020, 30, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiffer, J.J.; Abbiss, C.R.; Nosaka, K.; Peake, J.M.; Laursen, P.B. Effect of cold water immersion after exercise in the heat on muscle function, body temperatures, and vessel diameter. Journal of science and medicine in sport 2009, 12, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, H.; Wijayanto, T.; Tochihara, Y. Neuromuscular function during knee extension exercise after cold water immersion. Journal of physiological anthropology 2017, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urso, M.L. Anti-inflammatory interventions and skeletal muscle injury: Benefit or detriment? Journal of applied physiology 2013, 115, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, E.; Lago-Penas, C.; Lago-Ballesteros, J. Tensiomyography of selected lower-limb muscles in professional soccer players. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2012, 22, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakić, M.; Ilić, V.; Toskić, L.; Duric, S.; Šimenko, J.; Marković, M.; Cuk, I. Acute effects of short-term massage procedures on neuromechanical contractile properties of rectus femoris muscle. Medicina 2024, 60, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Gimeno, E.; Sebio-Garcia, R.; Solé, J.; Lleida, A.; Moras, G. Short-term effects of two different recovery strategies on muscle contractile properties in healthy active men: A randomised cross-over study. Journal of Sports Sciences 2022, 40, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mur Gimeno, E.; Campa, F.; Badicu, G.; Castizo-Olier, J.; Palomera-Fanegas, E.; Sebio-Garcia, R. Changes in muscle contractile properties after cold-or warm-water immersion using tensiomyography: A cross-over randomised trial. Sensors 2020, 20, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophe, H. Conditioning recovery strategy to improve exercise performance (Korean edition): Seoul, South korea, 2017; pp. 105–122.

- Petersen, A.C.; Fyfe, J.J. Post-exercise cold water immersion effects on physiological adaptations to resistance training and the underlying mechanisms in skeletal muscle: A narrative review. Frontiers in sports and active living 2021, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ureña, B.; Rojas-Valverde, D.; Gutiérrez-Vargas, R. Effectiveness of two cold water immersion protocols on neuromuscular function recovery: A tensiomyography study. Frontiers in physiology 2018, 9, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edholm, P.; Ørtenblad, N.; Holmberg, H.C.; Sperlich, B. Optimizing recovery strategies for winter athletes: Insights for Milano-Cortina 2026 Olympic Games. Sport Sciences for Health 2024, 20, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Lee, I.; Yi, Y. The thermal effects of water immersion on health outcomes: An integrative review. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Average skin temperature=0. 3×(Chest+Upper arm)+0.2×(Thigh+Calf) |

| Variables | Treatment | Rest | IAE | 10min after exercise |

30min after exercise |

48hours after exercise |

72hours after exercise |

Sig | η ² |

| Average skin temperature (°C) |

Whole-body CWI (n=9) | 33.20 ±0.66 c,d |

32.72±0.70 c,d | 28.63±1.00#,+,e,f | 31.61±0.49+ | 33.23±0.49 | 33.10±0.82 | Treatment .761 | .022 |

| Lower-body CWI (n=9) | 32.55 ±0.50 c |

32.32±1.02 c | 30.84±1.39 d,e,f | 32.33±0.93 | 32.57±0.94 | 33.04±0.69 | Time .001* | .742 | |

| Control;Active recovery (n=9) | 32.40 ±0.78 c |

31.81±0.62 | 31.14±0.91d,e,f | 32.35±0.79 | 32.35±0.79 | 32.76±0.65 | Treatment .001*×Time | .488 | |

| Chest temperature (°C) |

Whole-body CWI (n=9) | 33.58 ±1.03 c |

32.29 ±0.99 c |

26.41±2.26#,+,d,e,f | 31.61±1.38#,+ | 33.72±0.83 | 33.44±1.72 | Treatment .111 | .167 |

| Lower-body CWI (n=9) | 33.17 ±1.16 |

31.61 ±1.18 |

31.90±1.40 | 33.23±1.58 | 32.84±1.27 | 33.19±1.36 | Time .001* | .595 | |

| Control;Active recovery (n=9) | 32.68 ±1.26 c |

31.40 ±0.97 |

30.41±1.02d,e,f | 32.77±1.71 | 33.44±1.58 | 33.11±1.74 | Treatment .001* ×Time |

.441 | |

| Thigh temperature (°C) |

Whole-body CWI (n=9) | 32.64 ±0.82 c |

32.97 ±1.51 c,d |

26.90±1.92+,d,e,f | 31.12±1.20 f | 32.94±0.73 | 32.86±0.50 | Treatment .423 | .069 |

| Lower-body CWI (n=9) | 32.33 ±1.22 c |

33.30±1.51 c | 29.17±2.47d,e,f | 31.79±1.03 | 32.22±1.18 | 32.77±0.81 | Time .001* | .691 | |

| Control;Active recovery (n=9) | 31.93 ±0.97 |

32.56±1.16 | 31.27±2.68 | 32.30±1.16 | 32.37±0.87 | 32.77±0.71 | Treatment ×Time.001* | .422 | |

| Upper-body temperature (°C) |

Whole-body CWI (n=9) | 33.67 ±0.50 |

33.43±0.80 | 33.22±1.07 | 32.92±0.96 | 33.58±0.75 | 33.18±0.91 | Treatment .036 | .242 |

| Lower-body CWI (n=9) | 32.42 ±0.61 |

32.87±1.28 | 32.87±1.79 | 33.18±1.08 | 32.78±0.85 | 32.89±0.84 | Time .399 | .041 | |

| Control;Active recovery (n=9) | 32.86 ±1.10 |

32.44±0.55 | 31.83±0.80 | 32.66±0.67 | 32.88±0.84 | 32.79±0.69 | Treatment ×Time .128 | .121 | |

| Lower-body temperature (°C) |

Whole-body CWI (n=9) | 32.55 ±1.12 c,d |

32.23 ±0.95 c,d |

26.63±1.41+,e,f | 30.41±0.67#,e,f | 32.18±0.80 | 32.79±0.58 | Treatment .206 | .140 |

| Lower-body CWI (n=9) | 32.01 ±0.66 c |

31.39±0.46 c | 28.00±2.30#,d,e | 30.18±0.58#,e,f | 32.13±1.47 | 32.79±0.66 | Time .001* | .755 | |

| Control;Active recovery (n=9) | 31.79 ±0.75 |

30.83±1.08 e,f | 31.11±0.88 | 31.39±0.94 | 32.15±0.52 | 32.26±0.80 | Treatment ×Time.001* | .529 |

| Variables | Treatment | Rest | IAE | 30min after exercise |

48hours after Exercise |

72hours after exercise |

Sig | η ² |

|

MVIC (%BW) |

Whole-body (n=9) | 353.56 ±52.99 |

306.22 ±57.14 |

327.11 ±57.71 |

346.44 ±37.55 |

357.89 ±44.90 |

Treatment .131 | .156 |

| Lower-body (n=9) | 342.89 ±30.25 |

274.78 ±39.77 |

319.56 ±48.39 |

330.33 ±27.35 |

344.67 ±46.24 |

Time .001* | .466 | |

| Control;Active recovery(n=9) | 323.56 ±48.27 |

265.89 ±51.57 |

277.89 ±65.67 |

283.00 ±66.67 |

316.89 ±78.69 |

Treatment×Time .452 | .075 |

| Variables | Treatment | Rest | IAE | 30min after exercise |

48hours after exercise |

72hours after exercise |

Sig | η2 |

| Pain scale (score) |

Whole-body CWI (n=9) | 0.67±1.12b,c | 7.11±2.14c,d,e | 2.89±1.36† | 1.11±1.53† | 1.22±1.20 | Treatment .001* | .486 |

| Lower-body CWI (n=9) | 0.78±1.30b,c | 6.33±1.50c,d,e | 2.56±1.01†,e | 1.00±1.23† | 0.44±0.53 | Time .001* | .826 | |

| Control;Active recovery (n=9) | 0.89±0.78b,c,d | 8.00±1.11c,d,e | 4.44±1.42e | 3.78±1.64e | 1.22±1.09 | Treatment*time .049* | .156 |

| Variables | Treatment | Rest | IAE | 30min after exercise |

48hours after exercise |

72hours after exercise |

Sig | η ² |

| CK (IU/L) |

Whole-body(n=9) | 207.56 ±77.40 |

230.00 ±78.34 |

240.89 ±77.28 |

311.33 ±160.75 |

235.44 ±88.94 |

Treatment .714 | .028 |

| Lower-body (n=9) |

209.22 ±89.34 |

251.33 ±106.12 |

241.56 ±106.14 |

360.44 ±168.68 |

308.11 ±183.98 |

Time .001* | .400 | |

| Control;Active recovery(n=9) | 175.00 ±74.05 |

189.44 ±41.36 |

196.56 ±52.85 |

391.11 ±184.16 |

261.11 ±109.28 |

Treatment*time .316 |

.092 | |

| LDH (U/L) |

Whole-body (n=9) |

249.63 ±40.67 |

275.25 ±52.01d,e |

232.50 ±38.70 |

204.88 ±46.55† |

198.13 ±47.35 |

Treatment .759 | .023 |

| Lower-body (n=9) |

224.88 ±41.52 |

241.25 ±48.44 |

234.00 ±47.85 e |

219.00 ±61.96† |

199.63 ±33.76 |

Time 001* | .378 | |

| Control;Active recovery(n=9) | 225.25 ±37.09 |

268.13 ±61.46 |

254.13 ±30.69 |

268.00 ±40.08 |

214.13 ±44.91 |

Treatment*time.027* | .171 |

| Variables | Treatment | Rest | 30min after exercise |

48hours after exercise |

72hours after exercise |

Sig. | η ² |

| Dm(mm) | Whole-body(n=9) | 7.3±1.8ᵇ | 4.5±2.2ᶜ | 7.6±2.4 | 7.5±1.8 | Treatment .839 | .014 |

| Lower-body(n=9) | 7.3±1.4ᵇ | 4.2±2.2ᶜ | 7.3±2.4 | 6.4±2.8 | Time .001* | .485 | |

| Control;Active recovery(n=9) | 7.1±2.5ᵇ | 6.1±2.2ᶜ | 7.3±2.3 | 6.6±1.6 | Treatment*time.047* | .165 | |

| Tc(ms) | Whole-body(n=9) | 29.9±6.0 | 32.1±9.0 | 29.0±5.4 | 29.7±4.3 | Treatment .373 | .079 |

| Lower-body(n=9) | 27.9±3.6 | 28.6±6.2 | 27.6±3.8 | 25.6±5.1 | Time .044* | .125 | |

| Control;Active recovery(n=9) | 28.8±3.3 | 31.6±5.3 | 27.0±5.2 | 28.2±3.8 | Treatment*time .749 | .037 | |

| Tr(ms) | Whole-body(n=9) | 34.7±40.7 | 47.5±48.6 | 33.1±40.8 | 52.9±72.2 | Treatment .236 | .113 |

| Lower-body(n=9) | 13.7±4.1 | 22.3±12.7 | 26.8±27.1 | 19.1±21.2 | Time .194 | .066 | |

| Control;Active recovery(n=9) | 23.3±29.8 | 57.3±45.4 | 26.8±27.2 | 28.2±35.0 | Treatment*time .498 | .067 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).