Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Set-Up and Pesticide Exposure

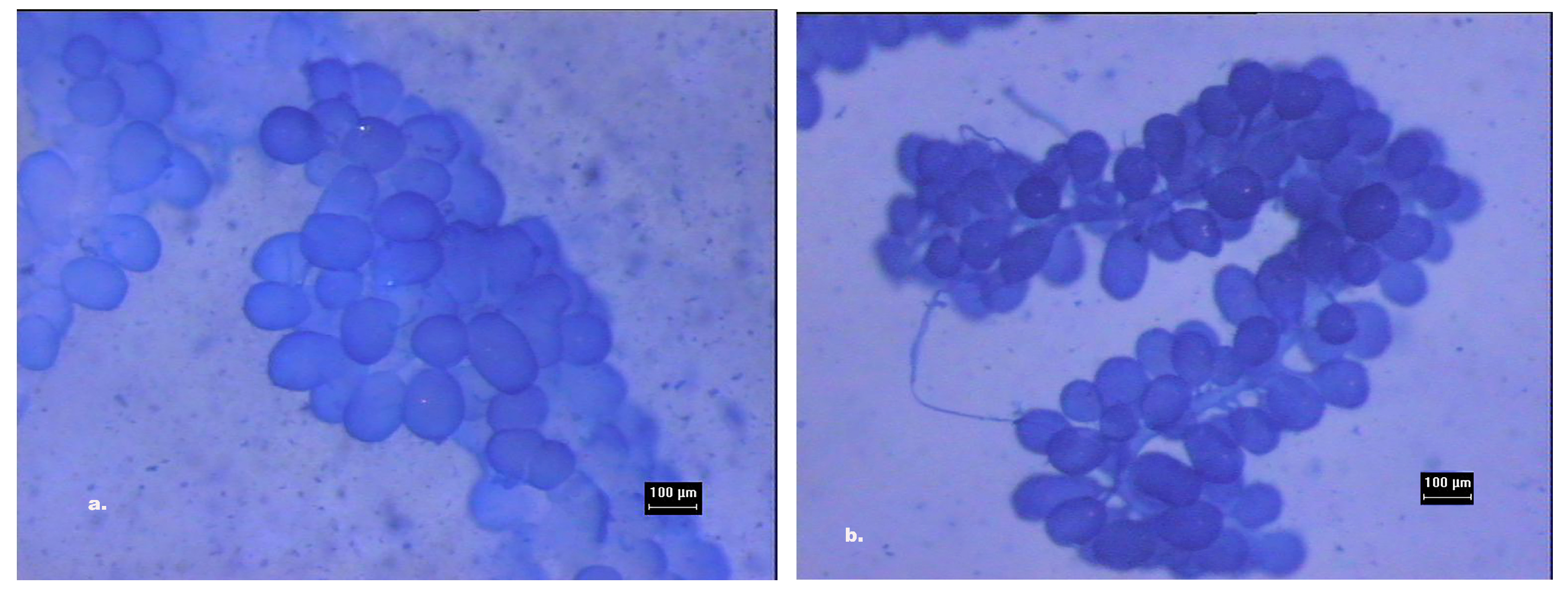

2.2. HPGs Dissection and Measurement

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

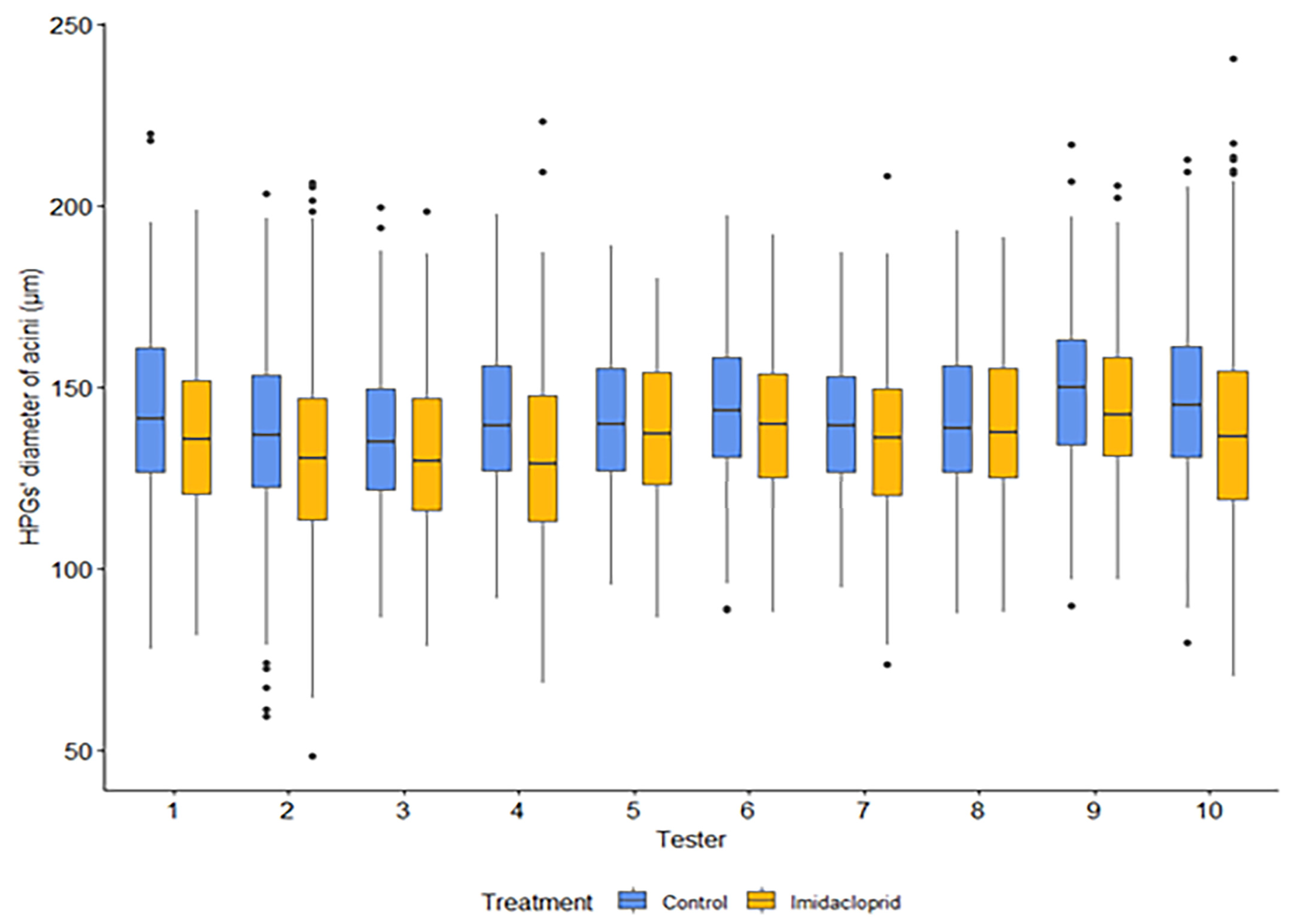

3.1. Reliability of Assessors

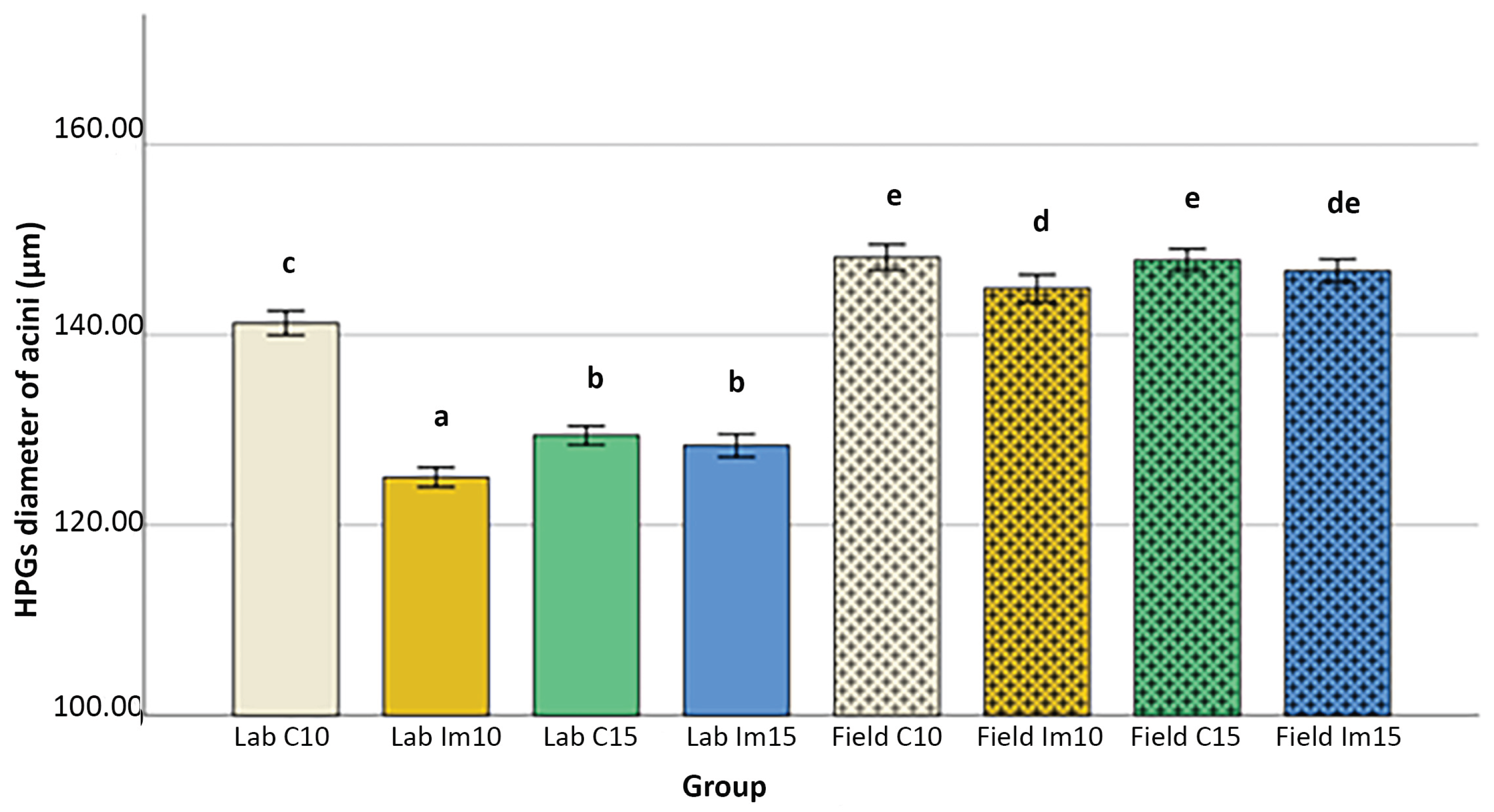

3.2. Effect of Treatment in Different Age Groups and Test Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPG | Hypopharyngeal Glands |

| GLM | General Linear Model |

References

- Aguilar, R.; Ashworth, L.; Galetto, L.; Aizen, M. A. Plant Reproductive Susceptibility to Habitat Fragmentation: Review and Synthesis through a Meta-analysis. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommarco, R.; Marini, L.; Vaissière, B. E. Insect Pollination Enhances Seed Yield, Quality, and Market Value in Oilseed Rape. Oecologia 2012, 169, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, S. G.; Biesmeijer, J. C.; Kremen, C.; Neumann, P.; Schweiger, O.; Kunin, W. E. Global Pollinator Declines: Trends, Impacts and Drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Carreck, N. L. Honey Bee Colony Losses. J. Apicult. Res. 2010, 49, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoux, J.-F.; Aupinel, P.; Gateff, S.; Requier, F.; Henry, M.; Bretagnolle, V. ECOBEE: A Tool for Long-Term Honey Bee Colony Monitoring at the Landscape Scale in West European Intensive Agroecosystems. J. Apicult. Res. 2014, 53, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, A.; Laurent, M.; EPILOBEE Consortium; Ribière-Chabert, M. ; Saussac, M.; Bougeard, S.; Budge, G. E.; Hendrikx, P.; Chauzat, M.-P. A Pan-European Epidemiological Study Reveals Honey Bee Colony Survival Depends on Beekeeper Education and Disease Control. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulson, D.; Nicholls, E.; Botías, C.; Rotheray, E. L. Bee Declines Driven by Combined Stress from Parasites, Pesticides, and Lack of Flowers. Science 2015, 347, 1255957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, J. A.; Daisley, B. A.; Pitek, A. P.; Thompson, G. J.; Reid, G. Understanding the Effects of Sublethal Pesticide Exposure on Honey Bees: A Role for Probiotics as Mediators of Environmental Stress. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Águila Conde, M.; Febbraio, F. Risk Assessment of Honey Bee Stressors Based on in Silico Analysis of Molecular Interactions. EFS2 2022, 20, (EU–FORA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, S.; Straub, L.; Neumann, P.; Williams, G. R. Negative but Antagonistic Effects of Neonicotinoid Insecticides and Ectoparasitic Mites Varroa Destructor on Apis Mellifera Honey Bee Food Glands. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacquière, T.; Smagghe, G.; Van Gestel, C. A. M.; Mommaerts, V. Neonicotinoids in Bees: A Review on Concentrations, Side-Effects and Risk Assessment. Ecotoxicology 2012, 21, 973–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon-Delso, N.; Amaral-Rogers, V.; Belzunces, L. P.; Bonmatin, J. M.; Chagnon, M.; Downs, C.; Furlan, L.; Gibbons, D. W.; Giorio, C.; Girolami, V.; Goulson, D.; Kreutzweiser, D. P.; Krupke, C. H.; Liess, M.; Long, E.; McField, M.; Mineau, P.; Mitchell, E. A. D.; Morrissey, C. A.; Noome, D. A.; Pisa, L.; Settele, J.; Stark, J. D.; Tapparo, A.; Van Dyck, H.; Van Praagh, J.; Van Der Sluijs, J. P.; Whitehorn, P. R.; Wiemers, M. Systemic Insecticides (Neonicotinoids and Fipronil): Trends, Uses, Mode of Action and Metabolites. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonmatin, J.-M.; Giorio, C.; Girolami, V.; Goulson, D.; Kreutzweiser, D. P.; Krupke, C.; Liess, M.; Long, E.; Marzaro, M.; Mitchell, E. A. D.; Noome, D. A.; Simon-Delso, N.; Tapparo, A. Environmental Fate and Exposure; Neonicotinoids and Fipronil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, J.; Frączek, R. J.; Siuda, M.; Bąk, B.; Hatjina, F.; Miszczak, A. The Influence of Sublethal Doses of Imidacloprid on Protein Content and Proteolytic Activity in Honey Bees ( Apis Mellifera L.). J. Apicult. Res. 2016, 55, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaluski, R.; Justulin, L. A.; Orsi, R. D. O. Field-Relevant Doses of the Systemic Insecticide Fipronil and Fungicide Pyraclostrobin Impair Mandibular and Hypopharyngeal Glands in Nurse Honeybees (Apis Mellifera). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Naggar, Y.; Baer, B. Consequences of a Short Time Exposure to a Sublethal Dose of Flupyradifurone (Sivanto) Pesticide Early in Life on Survival and Immunity in the Honeybee (Apis Mellifera). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleolog, J.; Wilde, J.; Gancarz, M.; Wiącek, D.; Nawrocka, A.; Strachecka, A. Imidacloprid Pesticide Causes Unexpectedly Severe Bioelement Deficiencies and Imbalance in Honey Bees Even at Sublethal Doses. Animals 2023, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, S.; Costa, C.; Vesco, U.; Quaglia, G.; Guido, G. A 3-Year Survey of Italian Honey Bee-Collected Pollen Reveals Widespread Contamination by Agricultural Pesticides. Sci. Total Envir. 2018, 615, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolami, V.; Marzaro, M.; Vivan, L.; Mazzon, L.; Greatti, M.; Giorio, C.; Marton, D.; Tapparo, A. Fatal Powdering of Bees in Flight with Particulates of Neonicotinoids Seed Coating and Humidity Implication. J. Appl. Entom. 2012, 136, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greatti, M.; Sabatini, A. G.; Barbattini, R.; Rossi, S.; Stravisi, A. Risk of Environmental Contamination by the Active Ingredient Imidacloprid Used for Corn Seed Dressing. Preliminary Results. Bull. Insectology 2003, 56, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Marzaro, M.; Vivan, L.; Targa, A.; Mazzon, L.; Mori, N.; Greatti, M.; Toffolo, E. P.; Bernardo, A. D.; Giorio, C.; Marton, D.; Girolami, V. Lethal Aerial Powdering of Honey Bees with Neonicotinoids from Fragments of Maize Seed Coat. Bull. Insectology 2001, 64, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Tapparo, A.; Marton, D.; Giorio, C.; Zanella, A.; Soldà, L.; Marzaro, M.; Vivan, L.; Girolami, V. Assessment of the Environmental Exposure of Honeybees to Particulate Matter Containing Neonicotinoid Insecticides Coming from Corn Coated Seeds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 2592–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, R.; Schöning, R.; Stork, A.; Schramel, O. Risk Posed to Honeybees ( Apis Mellifera L, Hymenoptera) by an Imidacloprid Seed Dressing of Sunflowers. Pest Management Science 2001, 57, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonmatin, J. M.; Marchand, P. A.; Charvet, R.; Moineau, I.; Bengsch, E. R.; Colin, M. E. Quantification of Imidacloprid Uptake in Maize Crops. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 5336–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauzat, M.-P.; Martel, A.-C.; Cougoule, N.; Porta, P.; Lachaize, J.; Zeggane, S.; Aubert, M.; Carpentier, P.; Faucon, J.-P. An Assessment of Honeybee Colony Matrices, Apis Mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) to Monitor Pesticide Presence in Continental France. Envir. Toxicol. Chem. 2011, 30, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolami, V.; Mazzon, L.; Squartini, A.; Mori, N.; Marzaro, M.; Di Bernardo, A.; Greatti, M.; Giorio, C.; Tapparo, A. Translocation of Neonicotinoid Insecticides From Coated Seeds to Seedling Guttation Drops: A Novel Way of Intoxication for Bees. J. Econ. Entomol. 2009, 102, 1808–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, S.; Sfeir, C.; Carnesecchi, E.; vanEngelsdorp, D.; Chauzat, M.-P. Lethal, Sublethal, and Combined Effects of Pesticides on Bees: A Meta-Analysis and New Risk Assessment Tools. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 156857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchner, W. H. 17. Mad-Bee-Disease? Subletale Effekte von Imidacloprid (Gaucho®) Auf Das Verhalten von Honigbienen. Apidologie, 0089. [Google Scholar]

- Tosi, S.; Burgio, G.; Nieh, J. C. A Common Neonicotinoid Pesticide, Thiamethoxam, Impairs Honey Bee Flight Ability. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, M. E.; Bonmatin, J. M.; Moineau, I.; Gaimon, C.; Brun, S.; Vermandere, J. P. A Method to Quantify and Analyze the Foraging Activity of Honey Bees: Relevance to the Sublethal Effects Induced by Systemic Insecticides. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2004, 47, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Romero, R.; Chaufaux, J.; Pham-Delègue, M.-H. Effects of Cry1Ab Protoxin, Deltamethrin and Imidacloprid on the Foraging Activity and the Learning Performancesof the Honeybee Apis Mellifera, a Comparative Approach. Apidologie 2005, 36, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Béguin, M.; Requier, F.; Rollin, O.; Odoux, J.-F.; Aupinel, P.; Aptel, J.; Tchamitchian, S.; Decourtye, A. A Common Pesticide Decreases Foraging Success and Survival in Honey Bees. Science 2012, 336, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatjina, F.; Papaefthimiou, C.; Charistos, L.; Dogaroglu, T.; Bouga, M.; Emmanouil, C.; Arnold, G. Sublethal Doses of Imidacloprid Decreased Size of Hypopharyngeal Glands and Respiratory Rhythm of Honeybees in Vivo. Apidologie 2013, 44, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, L.; Hatjina, F.; Ioannidis, P.; Hamamtzoglou, A.; Schoonvaere, K.; Francis, F.; Meeus, I.; Smagghe, G.; De Graaf, D. C. Stress Indicator Gene Expression Profiles, Colony Dynamics and Tissue Development of Honey Bees Exposed to Sub-Lethal Doses of Imidacloprid in Laboratory and Field Experiments. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. R.; Troxler, A.; Retschnig, G.; Roth, K.; Yañez, O.; Shutler, D.; Neumann, P.; Gauthier, L. Neonicotinoid Pesticides Severely Affect Honey Bee Queens. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, L.; Villamar-Bouza, L.; Bruckner, S.; Chantawannakul, P.; Gauthier, L.; Khongphinitbunjong, K.; Retschnig, G.; Troxler, A.; Vidondo, B.; Neumann, P.; Williams, G. R. Neonicotinoid Insecticides Can Serve as Inadvertent Insect Contraceptives. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2016, 283, 20160506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrock, C.; Tanadini, M.; Tanadini, L. G.; Fauser-Misslin, A.; Potts, S. G.; Neumann, P. Impact of Chronic Neonicotinoid Exposure on Honeybee Colony Performance and Queen Supersedure. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crailsheim, K.; Schneider, L. H. W.; Hrassnigg, N.; Bühlmann, G.; Brosch, U.; Gmeinbauer, R.; Schöffmann, B. Pollen Consumption and Utilization in Worker Honeybees (Apis Mellifera Carnica): Dependence on Individual Age and Function. J. Insect Physiol. 1992, 38, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milone, J. P.; Chakrabarti, P.; Sagili, R. R.; Tarpy, D. R. Colony-Level Pesticide Exposure Affects Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera L.) Royal Jelly Production and Nutritional Composition. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crailsheim, K.; Stolberg, E. Influence of Diet, Age and Colony Condition upon Intestinal Proteolytic Activity and Size of the Hypopharyngeal Glands in the Honeybee (Apis Mellifera L.). J. Insect Physiol. 1989, 35, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, D,; Kaatz, H. H. Patterns of larval food production by hypopharyngeal glands in adult worker honey bees. Apidologie 1990, 21, 457–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deseyn, J.; Billen, J. Age-Dependent Morphology and Ultrastructure of the Hypopharyngeal Gland of Apis Mellifera Workers (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Apidologie 2005, 36, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Chen, Y.; Huang, E.; Huang, M. H. The Effect of Diet on Protein Concentration, Hypopharyngeal Gland Development and Virus Load in Worker Honey Bees (Apis Mellifera L.). J. Insect Physiol. 2010, 56, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, G.; Salignon, M.; Le Conte, Y.; Belzunces, L. P.; Decourtye, A.; Kretzschmar, A.; Suchail, S.; Brunet, J.-L.; Alaux, C. Influence of Pollen Nutrition on Honey Bee Health: Do Pollen Quality and Diversity Matter? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, E. W. Jr.; Shimanuki, H.; Caron, D. Optimum protein levels required by honey bees (Hymenoptera, Apidae) to initiate and maintain brood rearing. Apidologie 1977, 8, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.-D. S.; Abd Alla, A. E.; El-Masarawy, M. S.; Salem, R. A.; Hassan, N. N.; Moustafa, M. A. M. Sulfoxaflor Influences the Biochemical and Histological Changes on Honeybees (Apis Mellifera L.). Ecotoxicology 2023, 32, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, M. T.; Rodríguez-Gasol, N.; Medrzycki, P.; Porrini, C.; Martini, A.; Burgio, G.; Maini, S.; Sgolastra, F. Combined Effect of Pollen Quality and Thiamethoxam on Hypopharyngeal Gland Development and Protein Content in Apis Mellifera. Apidologie 2016, 47, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Khan, K. A.; Ghramh, H. A.; Li, J. Phosphoproteomics Analysis of Hypopharyngeal Glands of the Newly Emerged Honey Bees (Apis Mellifera Ligustica). J. King Saud Univ. - Science 2022, 34, 102206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Guidance on the Risk Assessment of Plant Protection Products on Bees (Apis Mellifera, Bombus Spp. and Solitary Bees). EFS2 2013, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, B.; Carmargo Abdalla, F. Programmed germ cell differentiation during ovary stages of oogenesis in caged virgin and fecundated queens of Apis mellifera Linné, 1758. Braz. J Morphol. Sci. 2005, 22, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, J.W.; Somerrville, D. C. Introduction and early performance of queen bees. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, E. M.; Abdu_Allah, G.; Tawfik, A. Impacts of Sub-Lethal Concentrations of Two Macrocyclic Lactone Insecticides on Nurse Bees (Apis Mellifera L.) Hypopharyngeal Glands Development. PREPRINT (Version 1) , 2022. 17 October. [CrossRef]

- Hrassnigg, N.; Crailsheim, K. Adaptation of Hypopharyngeal Gland Development to the Brood Status of Honeybee (Apis Mellifera L.) Colonies. J. Insect Physiol. 1998, 44, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poquet, Y.; Vidau, C.; Alaux, C. Modulation of Pesticide Response in Honeybees. Apidologie 2016, 47, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škerl, M. I. S.; Gregorc, A. Characteristics of hypopharyngeal glands in honeybees (Apis mellifera carnica) from a nurse colony. Slov. Vet. Res. 2015, 52, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bryś, M. S.; Skowronek, P.; Strachecka, A. Pollen Diet—Properties and Impact on a Bee Colony. Insects 2021, 12, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño, E. L.; Yokota, S.; Stacy, W. H. O.; Arathi, H. S. Dietary Phytochemicals Alter Hypopharyngeal Gland Size in Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera L.) Workers. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Laboratory | Field | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessor | C-10 | I-10 | C-15 | I-15 | C-10 | I-10 | C-15 | I-15 |

| T1 | 138.94 | 123.66 | 130.33 | 124.15 | 148.46 | 147.34 | 151.02 | 146.82 |

| T2 | 138.46 | 121.53 | 125.80 | 126.31 | 142.42 | 135.38 | 144.15 | 142.76 |

| T3 | 135.27 | 120.07 | 125.99 | 125.41 | 142.28 | 139.38 | 142.28 | 140.31 |

| T4 | 143.38 | 119.14 | 123.79 | 122.32 | 145.73 | 141.26 | 148.65 | 143.42 |

| T5 | 140.67 | 124.02 | 128.94 | 128.28 | 146.96 | 145.12 | 145.59 | 150.76 |

| T6 | 143.23 | 129.66 | 129.97 | 131.57 | 151.20 | 149.06 | 153.36 | 149.80 |

| T7 | 138.88 | 124.34 | 130.17 | 129.95 | 145.52 | 143.97 | 147.40 | 146.89 |

| T8 | 140.32 | 126.11 | 132.14 | 133.00 | 148.94 | 146.51 | 141.88 | 150.17 |

| T9 | 146.96 | 134.87 | 137.37 | 132.87 | 158.16 | 156.11 | 157.06 | 158.21 |

| T10 | 145.76 | 127.36 | 131.49 | 129.29 | 154.72 | 149.47 | 150.76 | 144.83 |

| Mean Val. | 141.19 | 125.08 | 129.60 | 128.32 | 148.44 | 145.36 | 148.22 | 147.40 |

| St.Dev. | 3.61 | 4.71 | 3.85 | 3.69 | 5.10 | 5.83 | 4.93 | 5.12 |

| Reliability | 97.44% | 96.23% | 97.03% | 97.12% | 96.56% | 95.99% | 96.67% | 96.52% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).