Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Fatty Acid Oxidation

2.1.1. Effects of Maternal Supplementation of Clofibrate on Fatty Acid Metabolism in the Intestinal Mucosa of Piglets During the Neonatal-Suckling Period

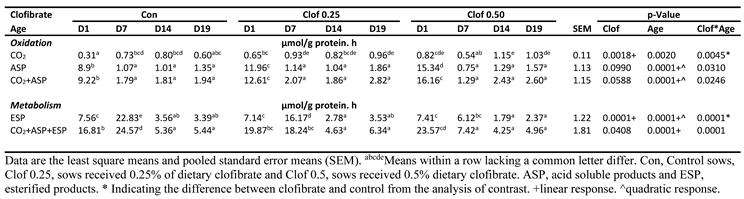

- Significant interactions between maternal supplementation of clofibrate and postnatal age were observed for the 14C accumulation in CO2 (p < 0.005), ASP (p < 0.05), and ESP (p < 0.0001) as well as the total oxidation (p < 0.05) and total metabolism (p < 0.0001) from oleic acid (Table 1).

- The 14CO2 accumulation was stimulated linearly with the dose of maternal clofibrate on d1 (p < 0.0005), but the stimulation was diminished after d7 depending on the dose. The accumulation rate measured on d1 was 1.1 and 1.6-fold greater in piglets from sows with 0.25 and 0.5% clofibrate than controls. The difference was not detectable on d7, while the accumulation was 60% higher on d19 from 0.25% and 44% and 72% higher on d 14 and 19 from 0.5% clofibrate treated sows than from the controls (p < 0.05).

- The 14C accumulation in ASP on d1 was 1.3 and 1.7-fold higher in pigs from sows with 0.25 and 0.5% clofibrate than from the controls (p < 0.05), but the maternal supplementation had no effects on the 14C accumulation in ASP in pigs after d1. The 14C accumulation in ASP was higher from d1 than all other ages (p < 0.0001), and no differences were observed between all other ages.

- The 14C accumulation in ESP in piglets from control sows increased from d1 to 7 but decreased greatly after d7 (p < 0.005). The accumulation was on average 61% and 81% lower from d 14 and 19 than d1 and d7. No difference was detected between d 14 and 19. Maternal clofibrate had no impact on the accumulation in ESP on d 1, 14 and 19, but decreased the accumulation in ESP on d 7 (p < 0.0001). The decrease was greater from maternal clofibrate level 0.5% than 0.25%.Third bullet.

- The 14C accumulation in total oxidation (CO2 + ASP) was 37% and 79% higher in piglets on d1 from sows with 0.25 % and 0.5 % clofibrate than from the controls (p < 0.05), but supplementation had no effects on the 14C accumulation after d1. The 14C accumulation in CO2 + ASP was higher from d1 than that measured from other ages (p < 0.0001), but no differences were observed between all other ages.

- The 14C accumulation in the total metabolism (CO2+ASP+ESP) in piglets from control sows increased from d1 to 7 (p < 0.005) but had no difference on d 14 and 19. The accumulation was 3.1 and 4.6-fold higher on average from d1 and 7 than d14 and 19 (p < 0.0001). Maternal supplementation of 0.5% clofibrate increased the total metabolism on day 1 (p < 0.005) but decreased the accumulation in ESP on d 7. The decrease was greater from maternal clofibrate level 0.5% than 0.25%.

2.1.1. Effects of Maternal Supplementation of Clofibrate on Fatty Acid Metabolism in the In-Testinal Mucosa of Piglets During the Neonatal-Suckling Period

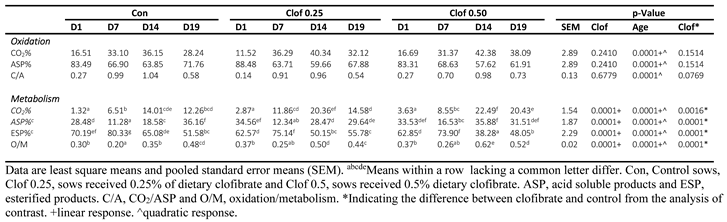

- The % CO2 in total FA oxidation increased, and % of ASP in Total FA oxidation decreased linearly with maternal clofibrate dose (p < 0.05) and postnatal age (p < 0.0001). No interactions (p > 0.1) were detected between maternal clofibrate and postnatal age (Table 2).

- The % of CO2, ASP and ESP in total FA metabolites had significant (p <0.005) interactions (Table 2) between the maternal clofibrate and age. The % of CO2 in total metabolites increased with age from d1 to d14 (p < 0.0001), but the increase was greater in pigs from sows fed 0.25% clofibrate on d7. The % CO2 in pigs on d14 and 19 from sows fed 0.5% clofibrate were higher than that from control sows (p < 0.05). The % of CO2 in pigs from sows fed 0.25% clofibrate was lower at d 19 compared to d14 (p< 0.005), but the % measured in pigs from sows fed 0 or 0.5% clofibrate showed no difference. The % of ASP in total metabolites measured in piglets from control sows was decreased from d1 to d7 and then increased from d7 to d19 (p < 0.0001). Maternal clofibrate increased the % of ASP, but the increase varied with age and clofibrate dose. The % was higher in piglets on d1 and 14 from sows fed 0.25% clofibrate than control sows, and on d7 and d14 from sows fed 0.5% clofibrate than the controls (p < 0.05). The % of ESP in total metabolites in pigs from control sows increased from d1 to d7 but decreased after d7 (p < 0.005). As opposed to the % of ASP, maternal supplementation of clofibrate decreased the % of ESP and the decrease varied with the age and dose of maternal clofibrate supplementation. The decrease in % of ESP from 0.5% of clofibrate was similar as 0.25% of clofibrate on d1 and d7 but was greater than 0.25% of clofibrate on d14 and 19 (p < 0.05).

- There was no interaction between maternal clofibrate and age on the ratio of CO2 and ASP (C/A). Maternal clofibrate also had no impact on the ratio, but the ratio increased with age. On average the ratio increased by 2.75-fold after d7 compared to d1 (p < 0.0001). The ratio of oxidized and metabolized products (O/M) in piglets from the control sows decreased by 34% from d1 to d7 but increased by 106% from d7 to d14 and by 37% from d14 to d19 (p < 0.001). Maternal clofibrate had no impact on the ratio at d1 and d7 but increased greatly after d7. The ratio in piglets from clofibrate-fed sows was on average 13% and 39% higher than control sows (p < 0.005).

2.1.3. Effects of Carnitine and Malonate on Fatty Acid Metabolism in the Intestinal Mucosa of Piglets During the Neonatal-Suckling Period

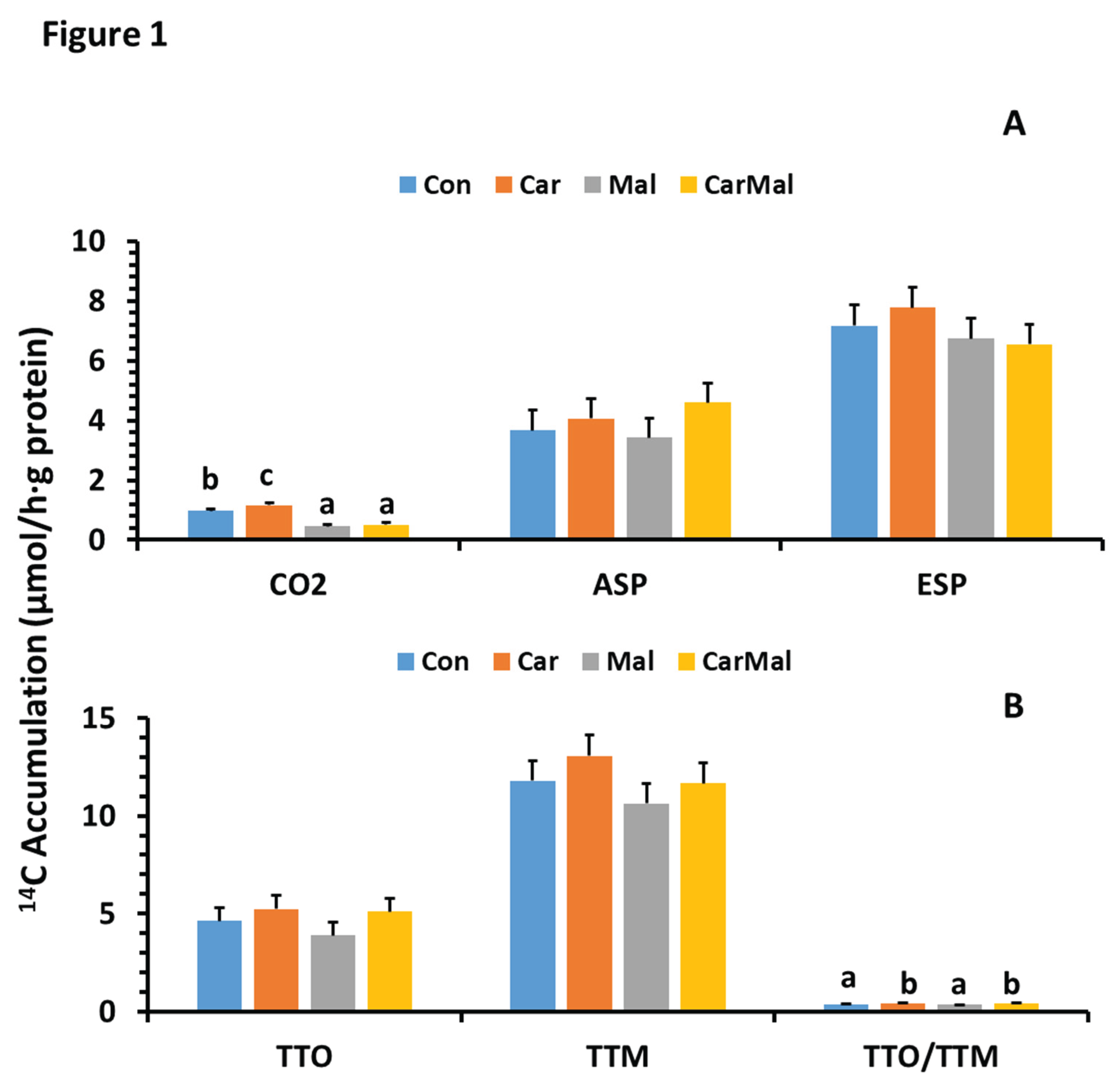

- No interaction (Figure 1A) was detected between maternal clofibrate (p = 0.9) and the tissue treatment with carnitine or malonate for CO2 production. However, the supplementation of carnitine increased 14C accumulation in CO2 by 18% compared to control (p < 0.05). Supplementation of malonate decreased 14C accumulation in CO2 by 61% compared to control (p < 0.0001). No improvement was observed after adding carnitine to the treatment with malonate. Supplementation of carnitine or/and malonate in the mucosa incubation had no impact on the accumulation in ASP (p > 0.1). No interaction was detected between maternal clofibrate (p > 0.1) and the tissue treatment with carnitine or malonate. The tissues from all pigs treated with carnitine and malonate had no impact on the ESP production (p > 0.1).

- Total oxidized products (CO2 + ASP) and the total metabolites (CO2+ASP+ESP) were not affected by supplementation of carnitine or/and malonate (p > 0.1). No interaction was detected between maternal clofibrate (age) and the tissue treatment with carnitine or malonate (Figure 1B). Addition of carnitine increased the ratio of O/M regardless of malonate treatment (p < 0.0001), but no interaction was detected between maternal clofibrate (age) and the tissue treatment with carnitine or malonate.

2.1.4. Effects of CARNITINE and malonate on Distribution (%) of CO2, ASP and ESP in Total Fatty Acid Oxidation and Metabolism in the Intestinal Mucosa of Piglets During the Neonatal-Suckling Period

- There was no interaction between maternal clofibrate treatments and the treatments with carnitine and/or malonate (p > 0.05). However, significant interactions were detected between adding carnitine or/and malonate and postnatal age for % of CO2 and ASP (p < 0.0 1) in total oxidation and the C/A (p < 0.0001) as well as the % of CO2 (p < 0.0001) and ASP (p < 0.01) in the total metabolism. The interaction for ESP % in the total metabolism and the O/M also tended to be significant (p = 0.052).

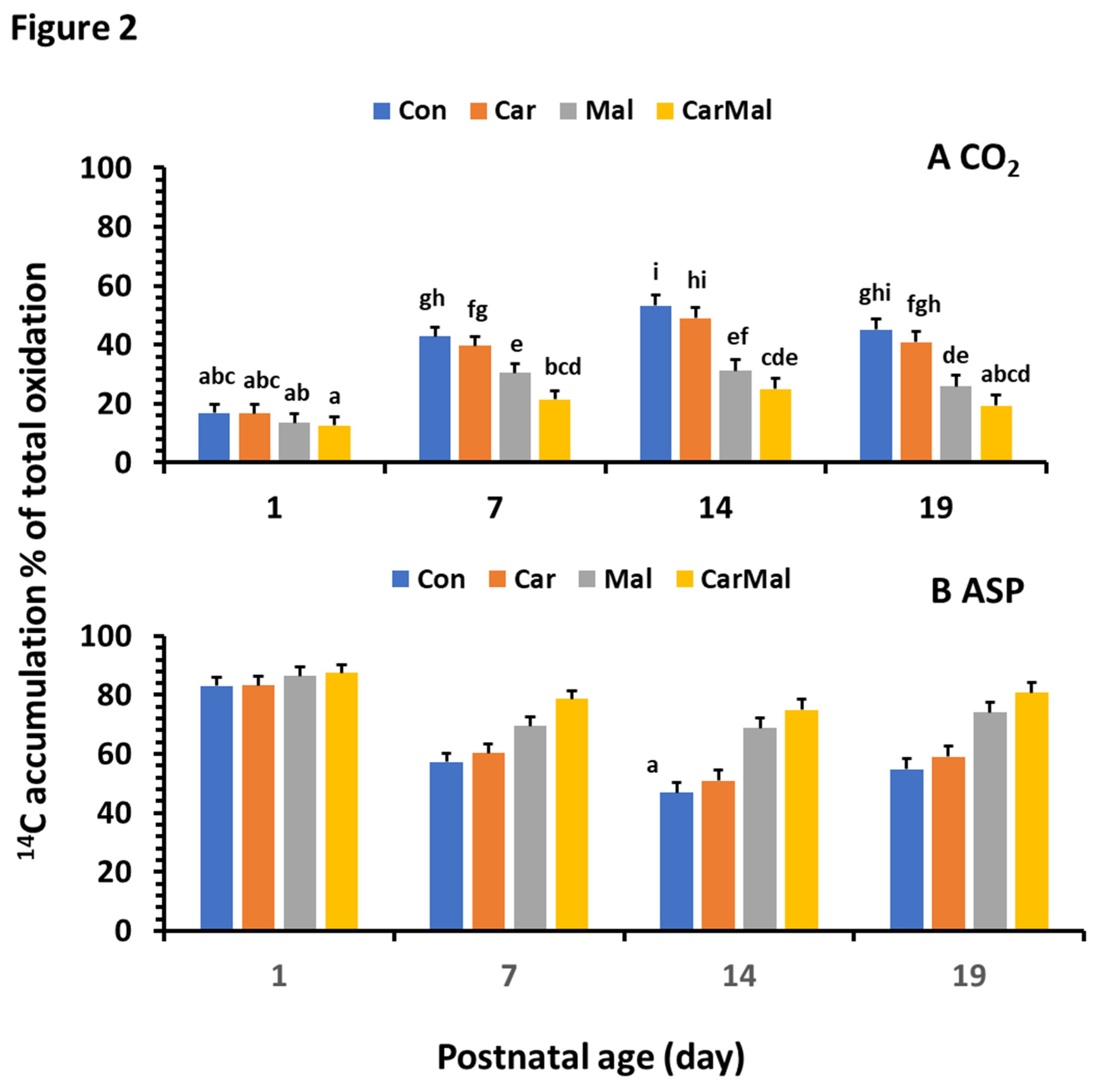

- Addition of carnitine in the incubation medium had no influence on the % of CO2 and ASP in the total oxidized products (p > 0.1), but addition of malonate reduced % of CO2 (Figure 2A) and increased % of ASP (Figure 2B) in all ages (p < 0.05). The decrease was greater from the addition of carnitine+malonate than malonate when compared to the control. The ratio of CO2/ASP in control group increased quadratically with age, but the increase was reduced by the addition of carnitine. Addition of malonate inhibited the ratio increase with age and kept the ratio with no difference from the d1.

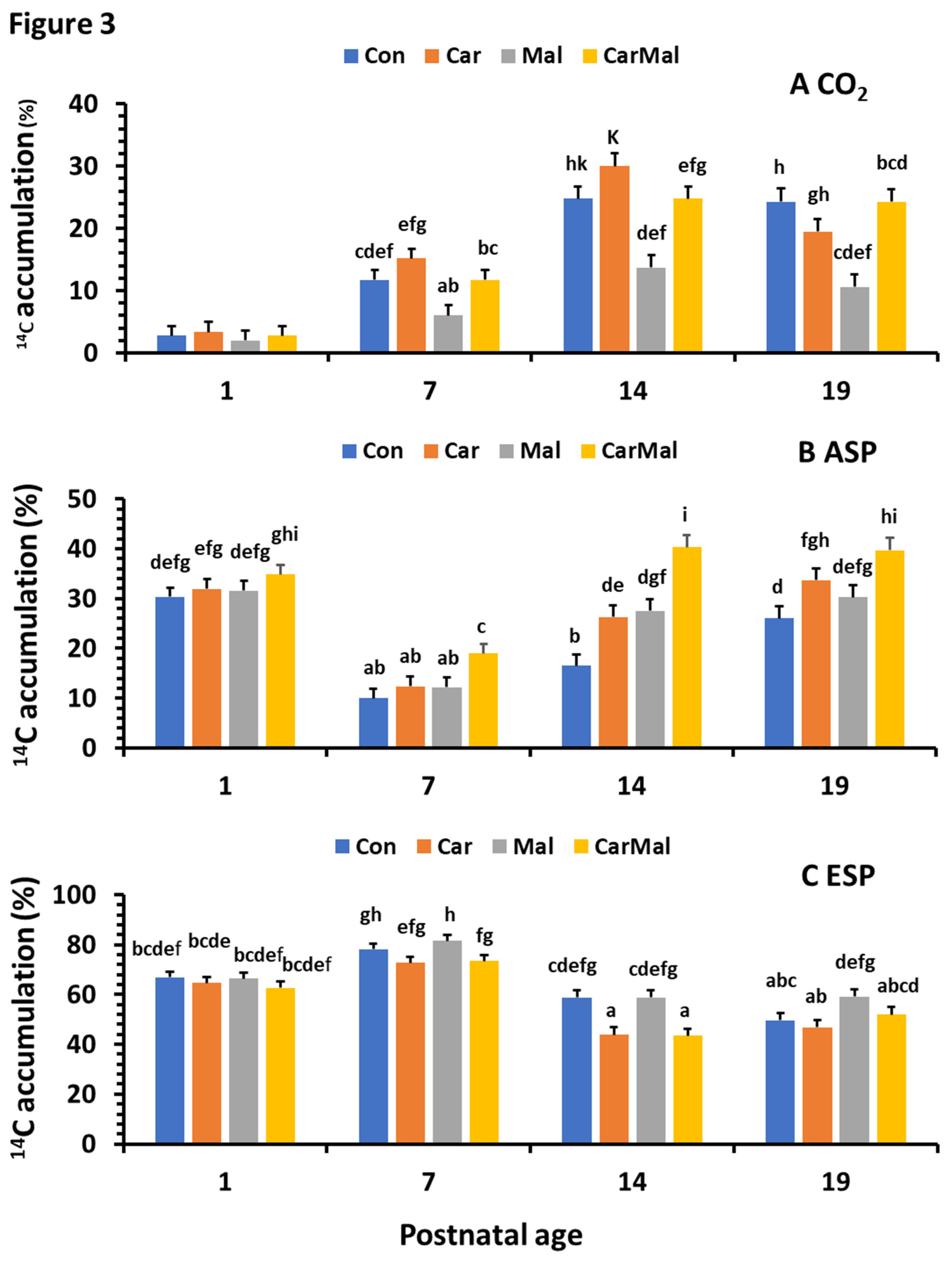

- A similar pattern of % of CO2 (Figure 3A) as in oxidation was observed from control group. However, the % of ASP (Figure 3B) significantly decreased after d1, and the decrease was greater from d7 than d14 and 19. Addition of carnitine or/and malonate increased % of ESP (Figure 3C) and the increase was greater from carnitine+malonate than carnitine or malonate only. No difference was observed between d14 and 19. The % of ESP increased on d7 and decreased after d7. The increase was reduced by the addition of carnitine and increased by the addition of malonate. No impacts were detected after d7. The ratio of oxidation and metabolism followed the same pattern as observed in % ASP.

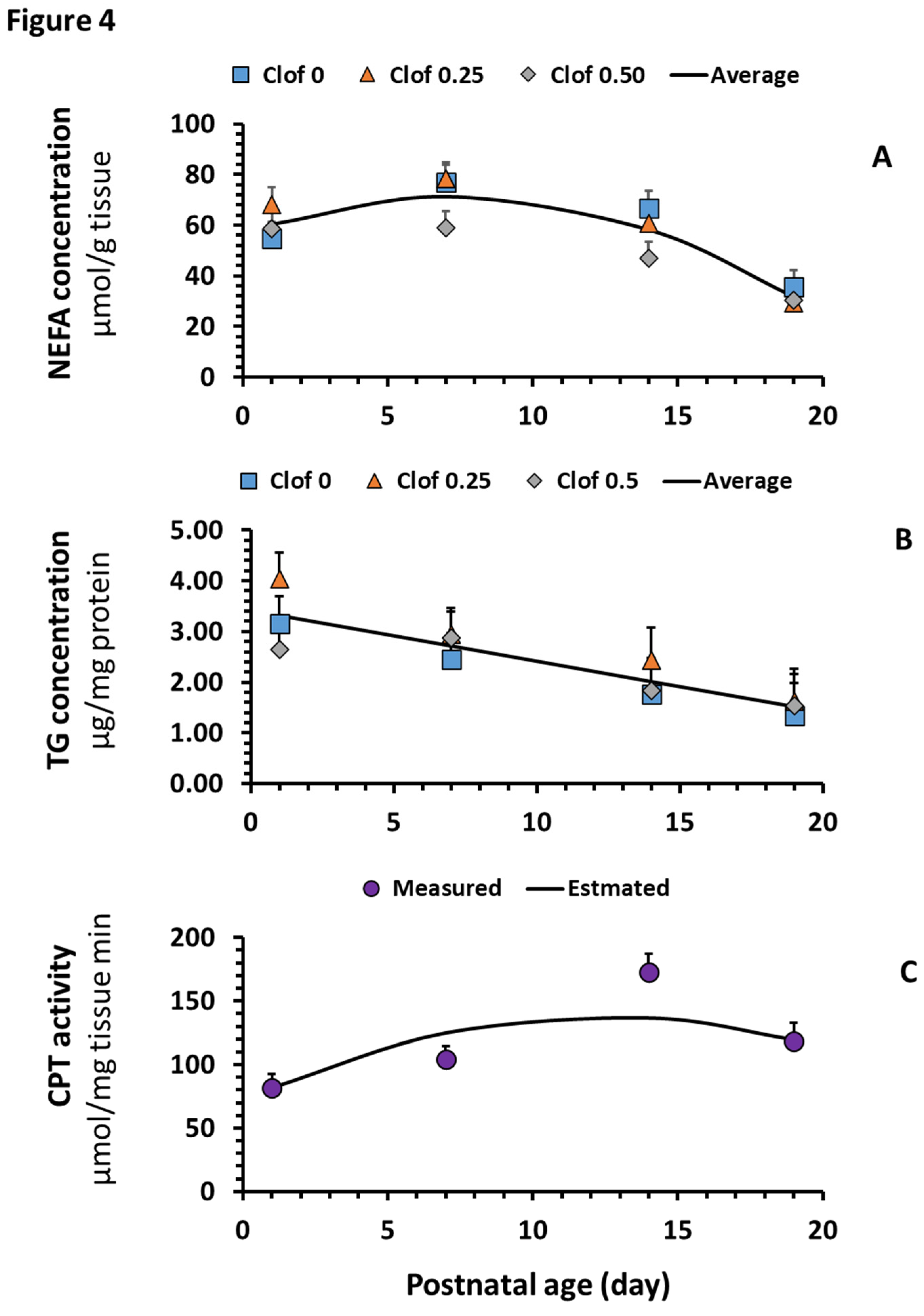

2.2. NEFA and TG Concentrations

2.3. CPT Enzyme Activity

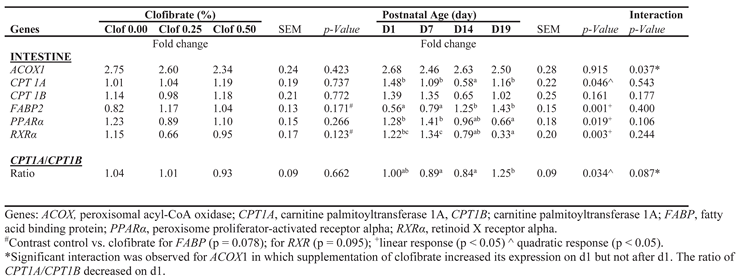

2.4. Gene Expression (qPCR)

3. Discussion

3.1. The Effect of Maternal Clofibrate on Intestinal Fatty Acid Metabolism in Suckling Piglets

3.2. The effect of Providing Carnitine and Inhibiting TCA Activity on Intestinal Fatty Acid Metabolism in Suckling Pigs

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Treatments

4.2. Fatty Acid Metabolism Measurements

4.3. Non-Esterified Fatty Acids (NEFA) and Triglycerides (TG) Assays

4.4. Enzymatic Assay

4.5. RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

4.6. Chemicals

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACOX1 | Acyl-CoA oxidase 1 |

| ASP | Acid soluble products |

| ESP | Esterification products |

| FA | Fatty acid |

| FABPs | FA-binding proteins |

| HMGCS | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase |

| NEFA | Non-Esterified Fatty Acids |

| RXRα | Retinoid X receptor alpha |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TG | Triglycerides |

References

- Herrera E, Amusquivar E. Lipid metabolism in the fetus and the newborn. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000, 16(3):202-10. [CrossRef]

- Girard J, Ferré P, Pégorier JP, Duée PH. Adaptations of glucose and fatty acid metabolism during perinatal period and suckling-weaning transition. Physiol Rev. 1992, 72(2):507-62. [CrossRef]

- Hahn P, Koldovskv O: Utilization of Nutrients During Postnatal Development. Oxford,Pergamon Press, 1966, p 17.

- Weström B, Arévalo Sureda E, Pierzynowska K, Pierzynowski SG, Pérez-Cano FJ. The Immature Gut Barrier and Its Importance in Establishing Immunity in Newborn Mammals. Front Immunol. 2020, 9;11:1153. [CrossRef]

- Kimura RE. Neonatal intestinal metabolism. Clin Perinatol. 1996, 23(2):245-63. [CrossRef]

- Girard J, Duée PH, Ferré P, Pégorier JP, Escriva F, Decaux J F. Fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis during development. Reprod. Nutr. Develop. 1985, 25(1 B), 303-319. [CrossRef]

- Small,G. M., T. J. Hocking, A. P. Strudee, K. Burdett, and M. J. Connock. 1981. Enhancement by dietary clofibrate of peroxisomal palmityl-CoA oxidase in kidney and small intestine of albino mice and liver of genetically lean and obese mice. Life Sci. 1981, 28:1875–82. [CrossRef]

- Kimura R, Takahashi N, Murota K, Yamada Y, Niiya S, Kanzaki N, Murakami Y, Moriyama T, Goto T, Kawada T. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARalpha) suppresses postprandial lipidemia through fatty acid oxidation in enterocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011, 24;410(1):1-6. [CrossRef]

- Kimura R, Takahashi N, Lin S, Goto T, Murota K, Nakata R, Inoue H, Kawada T. DHA attenuates postprandial hyperlipidemia via activating PPARalpha in intestinal epithelial cells. J Lipid Res. 2013, 54(12):3258-68. [CrossRef]

- Karimian Azari E, Leitner C, Jaggi T, Langhans W, Mansouri A. Possible role of intestinal fatty acid oxidation in the eating-inhibitory effect of the PPAR-alpha agonist Wy-14643 in high-fat diet fed rats. PLoS One. 2013, 17;8(9):e74869. [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki K, Suruga K, Yagi E, Takase S, Goda T. The expression of PPAR-associated genes is modulated through postnatal development of PPAR subtypes in the small intestine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001, 1531(1-2):68-76. [CrossRef]

- Ringseis R, Eder K. 2009. Influence of pharmacological PPARalpha activators on carnitine homeostasis in proliferating and non-proliferating species. Pharmacol. Res. 2009, 60:179–84. [CrossRef]

- Shim K, Jacobi S, Odle J, Lin X. Pharmacologic activation of peroxisome proliferator-activating receptor-α accelerates hepatic fatty acid oxidation in neonatal pigs. Oncotarget. 2018, 8;9(35):23900-23914. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Pike B, Wang F, Yang L, Meisner P, Huang Y, Odle J, Lin X. Effects of maternal feeding of clofibrate on hepatic fatty acid metabolism in suckling piglet. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2024, 5;15(1):163. [CrossRef]

- Pike B, Zhao J, Hicks JA, Wang F, Hagen R, Liu HC, Odle J, Lin X. Intestinal Carnitine Status and Fatty Acid Oxidation in Response to Clofibrate and Medium-Chain Triglyceride Supplementation in Newborn Pigs. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 23;24(7):6066. [CrossRef]

- Lin X, Jacobi S, Odle J. Transplacental induction of fatty acid oxidation in term fetal pigs by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha agonist clofibrate. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2015, 26;6(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Simpson AE, Brammar WJ, Pratten MK, Cockcroft N, Elcombe CR. Placental transfer of the hypolipidemic drug, clofibrate, induces CYP4A expression in 18.5-day fetal rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 1996, 24(5):547-54.

- Simpson AE, Brammar WJ, Pratten MK, Elcombe CR. Translactational induction of CYP4A expression in 10.5-day neonatal rats by the hypolipidemic drug clofibrate. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995, 22;50(12):2021-32. [CrossRef]

- Nicot C, Hegardt FG, Woldegiorgis G, Haro D, Marrero PF. Pig liver carnitine palmitoyltransferase I, with low Km for carnitine and high sensitivity to malonyl-CoA inhibition, is a natural chimera of rat liver and muscle enzymes. Biochemistry. 2001, 20;40(7):2260-6.

- Relat J, Nicot C, Gacias M, Woldegiorgis G, Marrero PF, Haro D. Pig muscle carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPTI beta), with low Km for carnitine and low sensitivity to malonyl-CoA inhibition, has kinetic characteristics similar to those of the rat liver (CPTI alpha) enzyme. Biochemistry. 2004 Oct 5;43(39):12686-91.

- Voltti H, Hassinen IE. Effect of clofibrate on the hepatic concentrations of citric acid cycle intermediates and malonyl-CoA in the rat. Life Sci. 1981, 5;28(1):47-51. [CrossRef]

- Békési A, Williamson DH. An explanation for ketogenesis by the intestine of the suckling rat: the presence of an active hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A pathway. Biol Neonate. 1990, 58(3):160-5. [CrossRef]

- Wallenius V, Elias E, Elebring E, Haisma B, Casselbrant A, Larraufie P, Spak E, Reimann F, le Roux CW, Docherty NG, Gribble FM, Fändriks L. Suppression of enteroendocrine cell glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 release by fat-induced small intestinal ketogenesis: a mechanism targeted by Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery but not by preoperative very-low-calorie diet. Gut. 2020, 69(8):1423-1431. [CrossRef]

- Adams SH, Alho CS, Asins G, Hegardt FG, Marrero PF. Gene expression of mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase in a poorly ketogenic mammal: effect of starvation during the neonatal period of the piglet. Biochem J. 1997, 15;324 ( Pt 1)(Pt 1):65-73. [CrossRef]

- Darcy-Vrillon B, Cherbuy C, Morel MT, Durand M, Duée PH. Short chain fatty acid and glucose metabolism in isolated pig colonocytes: modulation by NH4+. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996, 23;156(2):145-51. [CrossRef]

- Pégorier JP, Duée PH, Girard J, Peret J. Metabolic fate of non-esterified fatty acids in isolated hepatocytes from newborn and young pigs. Evidence for a limited capacity for oxidation and increased capacity for esterification. Biochem J. 1983, 15;212(1):93-7. [CrossRef]

- Manners MJ, Mccrea MR. Changes in the chemical composition of sow-reared piglets during the 1st month of life. Br J Nutr. 1963, 17:495-513. [CrossRef]

- Cherbuy C, Guesnet P, Morel MT, Kohl C, Thomas M, Duée PH, Prip-Buus C. Oleate metabolism in pig enterocytes is characterized by an increased oxidation rate in the presence of a high esterification rate within two days after birth. J Nutr. 2012, 142(2):221-6. [CrossRef]

- Trotter PJ, Storch J. Nutritional control of fatty acid esterification in differentiating Caco-2 intestinal cells is mediated by cellular diacylglycerol concentrations. J Nutr. 1993, 123(4):728-36. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Trujillo A, Luecke SM, Logan L, Bradshaw C, Stewart KR, Minor RC, Ramires Ferreira C, Casey TM. Changes in sow milk lipidome across lactation occur in fatty acyl residues of triacylglycerol and phosphatidylglycerol lipids, but not in plasma membrane phospholipids. Animal. 2021, 15(8):100280. [CrossRef]

- Huang WY, Kummerow FA. Cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in swine. Lipids. 1976, 11(1):34-41. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi AA, Burger WC, Elson CE, Benevenga NJ. Effects of cereals and culture filtrate of Trichoderma viride on lipid metabolism of swine. Lipids. 1982, 17(12):924-34. [CrossRef]

- Lin X, Adams SH, Odle J. Acetate represents a major product of heptanoate and octanoate beta-oxidation in hepatocytes isolated from neonatal piglets. Biochem J. 1996, 15;318 (Pt 1) (Pt 1):235-40. [CrossRef]

- 34. Xi L, Matsey G, Odle J.The effect of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside (AICAR) on fatty acid oxidation in hepatocytes isolated from neonatal piglets. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2012, 17;3(1):30. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).