Dataset: The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive and are accessible through SRA series accession number PRJNA1269504; titled “PC12 NGF Withdrawal and Stimulation Time Series” (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1269504)

Dataset License: CC01.0

1. Summary (Required)

NGF plays a fundamental role in the development of the majority of PNS neurons and subsets of CNS neurons in mammals (e.g., [

1]). During a developmental window 50% of PNS neurons switch to becoming non NGF-dependent [

2]. In the adult nervous system, NGF primarily sustains innervation in the periphery from populations of sensory [

3] and sympathetic neurons [

4,

5], but also maintains connections of sparse populations in the CNS neurons including cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain [

6].

Upon nervous system injury, increased NGF synthesis in injured tissues promotes neuronal plasticity, including sprouting [

7,

8,

9] and sensitization [

10], and is required for wound healing and reinnervation (reviewed: [

11]). Dysregulated NGF signaling has been associated with a variety of diseases including sudden cardiac death following myocardial infarction [

12], autonomic dysreflexia following spinal cord injury [

13], autoimmune conditions [

14] and neuropathies [

15]. As such, strategies to modulate NGF signaling have therapeutic potential. However anti-NGF treatments such as used for diabetic neuropathy [

16] or osteoarthritis pain [

17] were withdrawn due to tissue degeneration and/or lack of efficacy, and trials using NGF-delivery strategies for treatment for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) were discontinued due to pain and/or lack of efficacy (e.g., [

18]). Therefore, detailed mechanistic understanding of NGF signaling and cellular responses downstream of ligand-receptor interactions may lead to the discovery of therapies with increased efficacy and reduced off-target effects.

Publicly available gene expression profiling data from in vitro models treated with NGF have served as a valuable resource for characterizing transcriptional responses, including RNA-Seq at various concentrations (1ng/ml, 50ng/ml and 100ng/ml, Otsuka Y, Nakajima K, Dataset, publicly available 2012, GSE37564 - although not peer reviewed), with continuous NGF treatments [

19] or short transient NGF treatments [

20,

21]. To our knowledge there is only one available expression profile dataset from cells subject to NGF deprivation, for up to 6 hours in DRG neuron cultures from embryonic day 13.5 [

22]. Therefore, none of these expression profile datasets provide information on the pulsatile effects of NGF on gene expression, and there are no available datasets characterizing the gene expression profile in cells that have NGF withdrawal followed by replenishment.

This RNA sequencing dataset was generated to investigate temporal changes in gene transcription following NGF withdrawal and replenishment using PC12 cells. Sequencing data presented is of high quality, reproduces gene expression changes of known marker genes and elucidates thousands of additional transcriptional changes. These data will be utilized for target selection and hypothesis generation to study transcriptional responses including gene expression changes, alternative polyadenylation (e.g., using CSI-UTR [

23]) and alternate splicing with diverse in vivo models of human disease ranging from pain to AD.

2. Data Description

2.1. Background and Experimental Design

PC12 cells are a robust model of NGF response. Upon NGF stimulation, PC12 cells undergo differentiation and develop a neuron-like phenotype, both morphologically and physiologically (e.g., [

8,

24]). While previous studies have published gene expression profiles from PC12 cells with NGF stimulation, there is no available data on the effects of NGF depletion on gene expression, at any time point in PC12 cells. Studies have shown that withdrawal of NGF from these cells leads to changes in transcriptional pathways that result in neurite retreat and apoptosis, while replenishing NGF can rescue these effects [

20,

25]. Characterization of the transcriptional changes taking place during this process could lead to a better understanding of trophic signaling in neurons and mechanisms of NGF-mediated axon growth and cell survival.

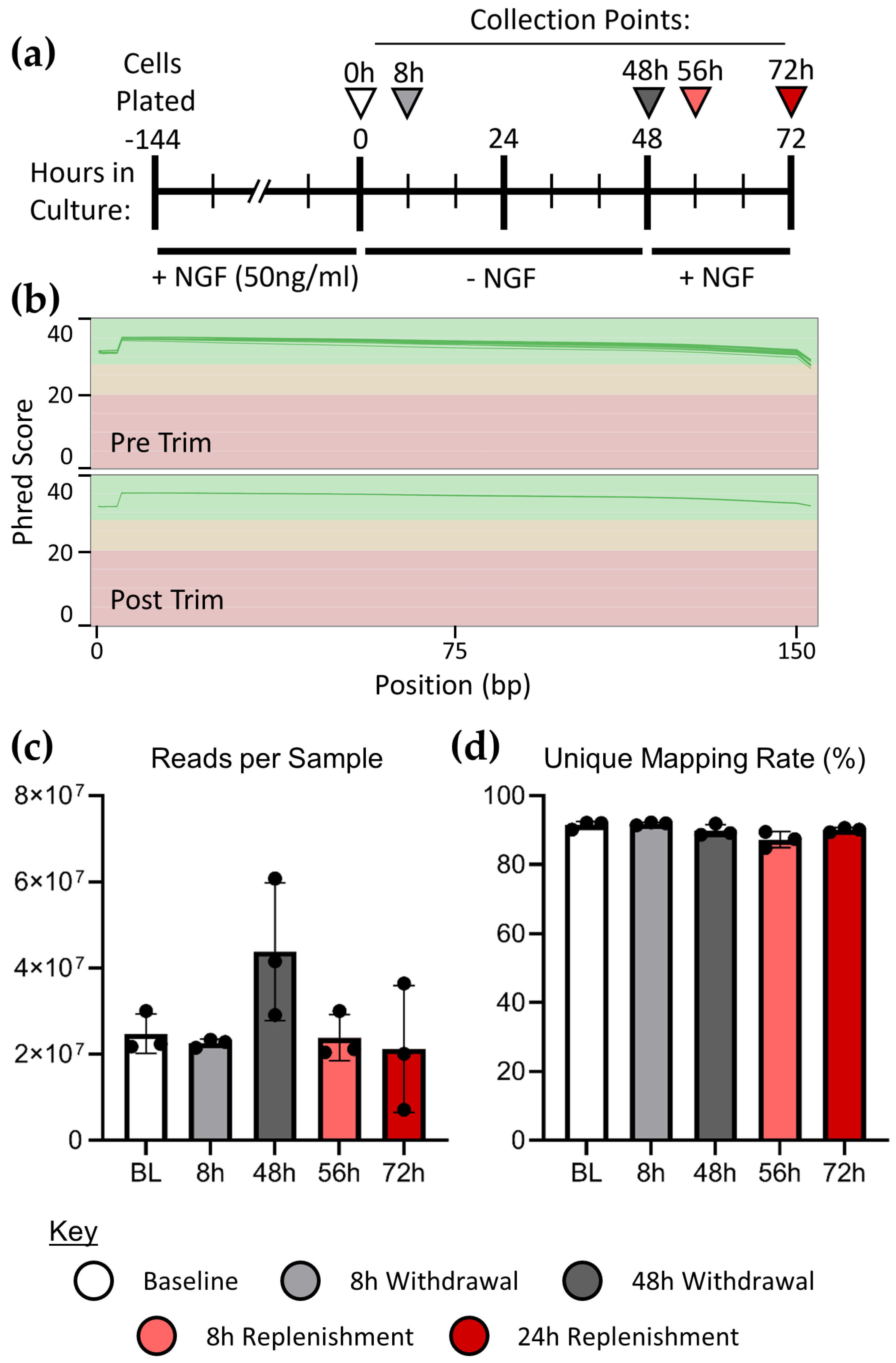

We employed a timecourse of NGF withdrawal and exposure in PC12 cells, and isolated RNA from culture at multiple timepoints (see

Figure 1a). Cells were plated on collagen and cultured with NGF for 3 days to allow them to differentiate, at which point NGF was depleted from culture for 48 hours, and subsequently replenished for 24 hours. Baseline RNA samples were harvested from the cells after 3 days of differentiation. Further RNA samples were taken after 8 and 48 hours of NGF withdrawal, and 8 and 24 hours of NGF replenishment, allowing for the temporal examination of resulting transcriptional changes.

2.2. RNA Sequencing Quality Validation

FASTQ files were subjected to quality control using the FastQC software. Per-base Phred scores indicate high confidence reads, which were improved by a second trimming of residual Illumina adapters from the reads using Trimmomatic (

Figure 1b). Surviving read count and unique mapping rate were verified using the STAR aligner (

Figure 1c, d).

2.3. Technical Validation

2.3.1. Differential Expression Analysis

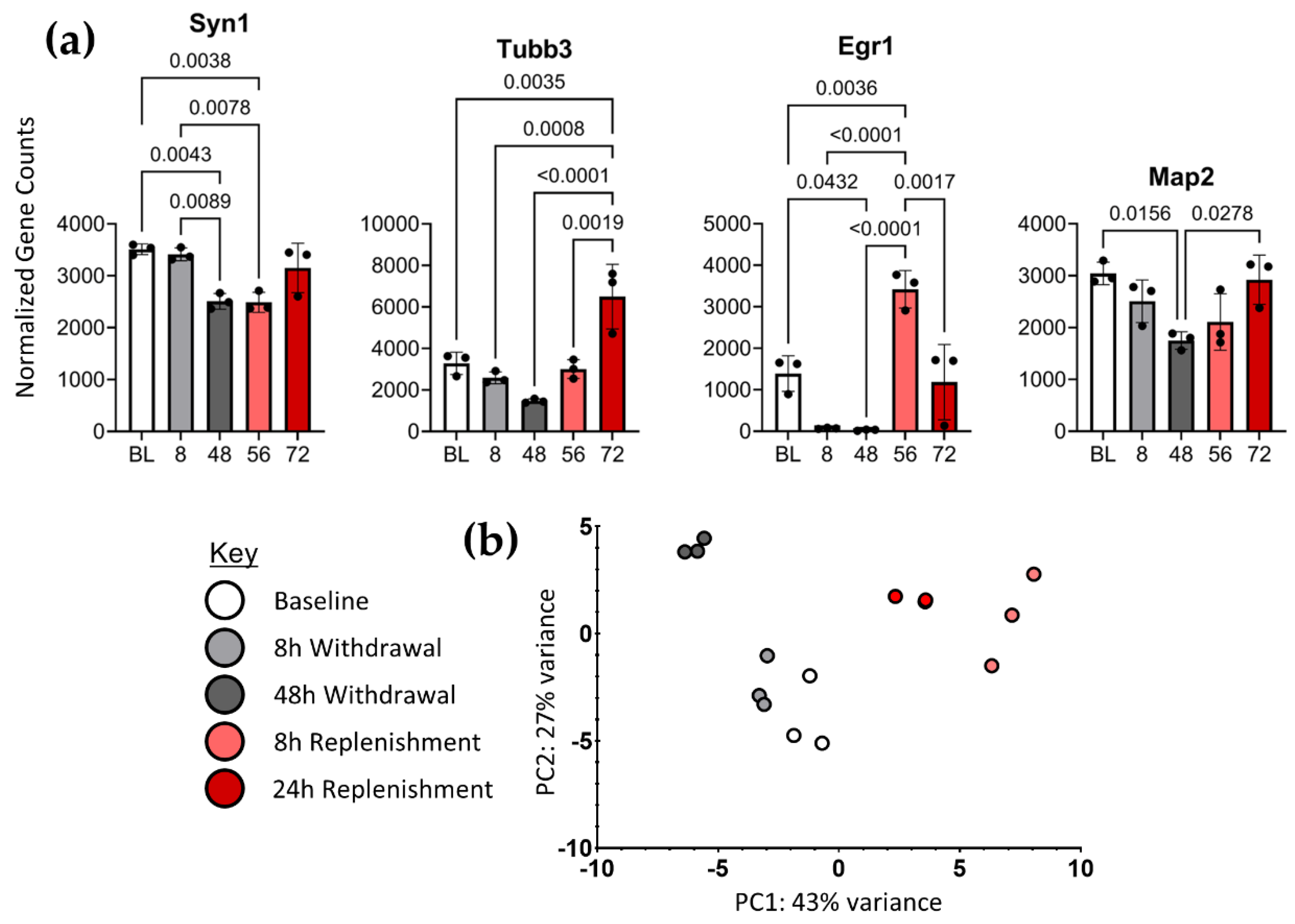

Gene counts from the STAR aligner were imported into RStudio for differential analysis with DESeq2. Normalized gene counts were used to produce gene expression plots for select genes to validate NGF response in these cells. Syn1 (), Tubb3 (), Egr1 () and Map2 () have all been identified as marker genes dependent on NGF signaling in PC12 cells.

2.3.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Following differential gene expression analysis, PCA was performed to reduce the dimensionality of the data and visualize variation between samples. The clustering of samples indicate consistency between treatment groups and a robust effect of NGF on gene expression (

Figure 2b).

2.4. Characterization of Expression Profiles

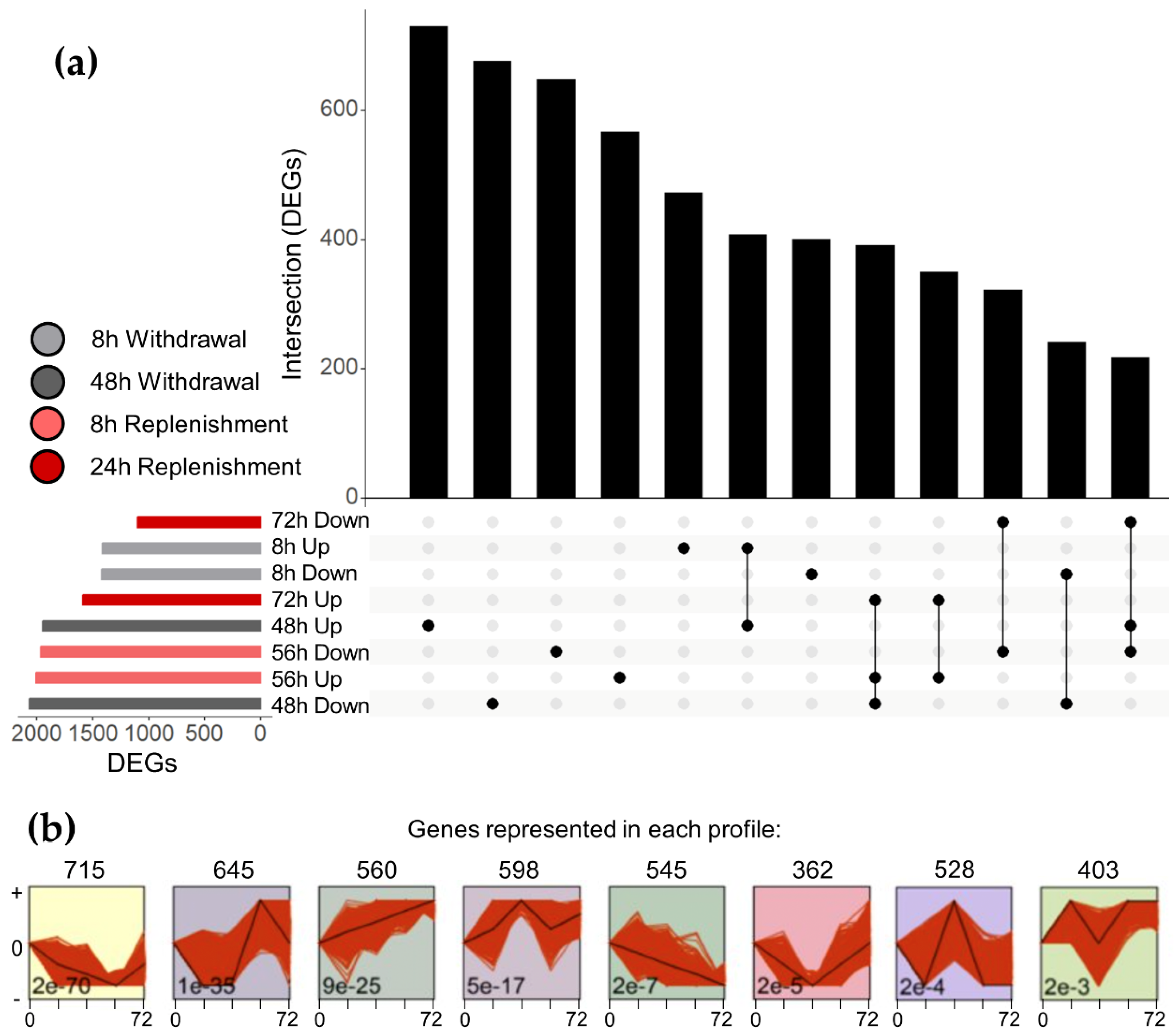

Genes with statistically significant differential expression at any timepoint were compared using an Upset [

26] graph (

Figure 3a). First, significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) at each timepoint were split into 2 groups, genes that were upregulated and genes that were downregulated. This graph indicates the total number of DEGs in each of these groups, as well as the number of DEGs that are shared between groups, visualizing the potential use of this dataset for identification of NGF targets.

Normalized read counts for all genes were exported to the Short Time-series Expression Miner (STEM) for analysis of expression profiles over the timecourse. Statistically overrepresented expression profiles are indicated in

Figure 3b, with the number of genes exhibiting each expression profile shown above. These expression profiles are generally associated with the timecourse of NGF stimulation, and represent the utility of this data in isolating genes that are correlated, positively or negatively, with NGF signaling in PC12 cells.

3. Methods (Required)

3.1. PC12 Cell Line Culture and NGF Treatment

PC12 cells were purchased from ATCC (Cat# CRL-1721) and maintained per manufacturer protocol in growth media containing RPMI01640 media (ATCC Cat# 30-2001) supplemented 10% Heat inactivated horse serum (ATCC Cat# 30-2004) and 5% fetal bovine serum and supplemented with 1% penicillin/ streptomycin (Lonza BioWhittaker Cat# 17-602E) and Gentamycin (VWR Cat# 0304-10G).

Cells were plated in 12-well plates (Corning, Collagen I coated plates #354400) in differentiation media containing RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 1% Heat inactivated horse serum (Gibco Cat# 26050-070) and supplemented with 50mg/ml NGF (Sigma, Cat # N-6009). Fresh differentiation media with or without NGF was replenished every 2 days, for total of 6 days before the start of the NGF withdrawal experiment. For the 8 and 48 hours withdrawal experiment cells were washed two times and supplemented with NGF free media for 8 and 48 hours respectively before the collected for RNA sequencing. Two experimental groups were replenished with NGF supplemented differentiation media for 8 and 24 hours following the 48 hours withdrawal before the sample were collected for RNA sequencing (

Figure 1a).

RNA was isolated from collected samples using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Spin Columns (Cat# 74104) and stored at -80°C until shipment. Three biological replicates were generated for each timepoint.

3.2. Sequencing, Mapping and Differential Gene Expression Analysis

Sequencing was performed at the University of Delaware DNA Sequencing & Genotyping Center. Supplied RNA was sequenced via polyA selection using Illumina HiSeq 2000, PE 2x150. Adapters were trimmed from reads at the vendor prior to our receival. Read quality was analyzed using FastQC v0.11.9 and MultiQC v1.9 (

Figure 1b), and we decided to perform a second trimming. TruSeq3-PE adapters were trimmed from sequence reads using Trimmomatic v0.38. Reads were mapped to the mRatBN7.2 reference genome using the STAR aligner v2.7.11, and raw reads determined using the GeneCounts output. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2 package v1.46.0 on R v4.4.0. Principal component analysis was also performed using DESeq2, after regularized log normalization of the raw count data. The R code used to analyze the gene count data is publicly available at:

3.3. STEM Clustering Analysis

Normalized gene counts for all genes were exported from DESeq2 and loaded into the Short Time-series Expression Miner (STEM) v1.3.13. Reads were normalized to the baseline expression and a total of 20 expression model profiles were generated. Only significantly enriched expression profiles were selected for representation (

Figure 3b).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N., E.G.D and B.J.H.; methodology, P.N., E.G.D and B.J.H.; software, P.N.; validation, P.N., E.G.D and B.J.H.; formal analysis, P.N., E.G.D and B.J.H.; investigation, P.N., E.G.D and B.J.H.; resources, P.N. and B.J.H.; data curation, P.N. and B.J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N., E.G.D and B.J.H.; writing—review and editing, P.N., E.G.D and B.J.H.; visualization, P.N., E.G.D and B.J.H.; supervision, P.N., and B.J.H.; project administration, B.J.H; funding acquisition, B.J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by: 1 - IDeA grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of National Institute of Health, grant number P20GM103423. 2 – National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of National Institute of Health, grant number R01NS121533. 3 - COBRE grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of National Institute of Health, grant number P20GM103643.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NGF |

Nerve Growth Factor |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| DEG |

Differentially Expressed Genes |

| DRG |

Dorsal Root Ganglia |

References

- Yuen, E. C., Howe, C. L., Li, Y., Holtzman, D. M. & Mobley, W. C. Nerve growth factor and the neurotrophic factor hypothesis. Brain Dev. 18, 362–368 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Molliver, D. C. et al. IB4-binding DRG neurons switch from NGF to GDNF dependence in early postnatal life. Neuron 19, 849–861 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Lewin, G. R. & Mendell, L. M. Nerve growth factor and nociception. Trends in Neurosciences vol. 16 353–359 https://edoc.mdc-berlin.de/5581/ (1993).

- Bjerre, B., Bjo¨rklund, A., Mobley, W. & Rosengren, E. Short- and long-term effects of nerve growth factor on the sympathetic nervous system in the adult mouse. Brain Res. 94, 263–277 (1975).

- Korsching, S. & Thoenen, H. Nerve growth factor in sympathetic ganglia and corresponding target organs of the rat: correlation with density of sympathetic innervation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 80, 3513–3516 (1983). [CrossRef]

- Cuello, A. C., Bruno, A. & Bell, K. F. S. NGF-Cholinergic Dependency in Brain Aging, MCI and Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 4, 351–358 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B. J. et al. Transcriptional changes in sensory ganglia associated with primary afferent axon collateral sprouting in spared dermatome model. Genomics Data 6, 249–252 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B. J. et al. The Adaptor Protein CD2AP Is a Coordinator of Neurotrophin Signaling-Mediated Axon Arbor Plasticity. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 36, 4259–4275 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J., Coughlin, M., Macintyre, L., Holmes, M. & Visheau, B. Evidence that endogenous beta nerve growth factor is responsible for the collateral sprouting, but not the regeneration, of nociceptive axons in adult rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84, 6596–6600 (1987). [CrossRef]

- Shu, X. & Mendell, L. M. Acute sensitization by NGF of the response of small-diameter sensory neurons to capsaicin. J. Neurophysiol. 86, 2931–2938 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Laverdet, B. et al. Skin innervation: important roles during normal and pathological cutaneous repair. (2015) . [CrossRef]

- Cardiac Innervation and Sudden Cardiac Death | Circulation Research. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304679. [CrossRef]

- Krenz, N. R., Meakin, S. O., Krassioukov, A. V. & Weaver, L. C. Neutralizing Intraspinal Nerve Growth Factor Blocks Autonomic Dysreflexia Caused By Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurosci. 19, 7405–7414 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S. D. Nerve growth factor: a neuroimmune crosstalk mediator for all seasons. Immunology 151, 1–15 (2017).

- Anand, P. Neurotrophic factors and their receptors in human sensory neuropathies. in Progress in Brain Research vol. 146 477–492 (Elsevier, 2004).

- Apfel, S. C. Nerve growth factor for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy: What went wrong, what went right, and what does the future hold? in International Review of Neurobiology vol. 50 393–413 (Academic Press, 2002).

- Miller, R. E., Block, J. A. & Malfait, A.-M. Nerve growth factor blockade for the management of osteoarthritis pain: what can we learn from clinical trials and preclinical models? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 29, 110 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Castle, M. J. et al. Postmortem Analysis in a Clinical Trial of AAV2-NGF Gene Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease Identifies a Need for Improved Vector Delivery. Hum. Gene Ther. 31, 415–422 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Karliner, J., Liu, Y. & Merry, D. E. Mutant androgen receptor induces neurite loss and senescence independently of ARE binding in a neuronal model of SBMA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2321408121 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Chung, J., Kubota, H., Ozaki, Y., Uda, S. & Kuroda, S. Timing-Dependent Actions of NGF Required for Cell Differentiation. PLOS ONE 5, e9011 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Offermann, B. et al. Boolean Modeling Reveals the Necessity of Transcriptional Regulation for Bistability in PC12 Cell Differentiation. Front. Genet. 7, (2016). [CrossRef]

- Maor-Nof, M. et al. Axonal Degeneration Is Regulated by a Transcriptional Program that Coordinates Expression of Pro- and Anti-degenerative Factors. Neuron 92, 991–1006 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B. J. et al. Detection of Differentially Expressed Cleavage Site Intervals Within 3’ Untranslated Regions Using CSI-UTR Reveals Regulated Interaction Motifs. Front. Genet. 10, 182 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kalman, D., Wong, B., Horvai, A. E., Cline, M. J. & O’Lague, P. H. Nerve growth factor acts through cAMP-dependent protein kinase to increase the number of sodium channels in PC12 cells. Neuron 4, 355–366 (1990). [CrossRef]

- Maggirwar, S. B., Ramirez, S., Tong, N., Gelbard, H. A. & Dewhurst, S. Functional Interplay Between Nuclear Factor-κB and c-Jun Integrated by Coactivator p300 Determines the Survival of Nerve Growth Factor-Dependent PC12 Cells. J. Neurochem. 74, 527–539 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Conway, J. R., Lex, A. & Gehlenborg, N. UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics 33, 2938–2940 (2017). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).