1. Introduction

The advent of the recombinant nucleic acid technology and its application across various fields of biotechnology have been key to improving human and animal health, agriculture, and the environment. Among all the expression platforms used to produce recombinant proteins, the baculovirus/insect expression system, also known as Baculovirus Expression Vector System (BEVS) stands out for its versatility and flexibility. It allows the efficient production of high-quality proteins at lower costs than mammalian cell systems, for diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive purposes [

1]. An increasing number of products derived from BEVS have received regulatory approval for use in both human and veterinary medicine [

2,

4].

The system is based on the Autographa californica Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus (AcMNPV),a prototypical species (

Alphabaculovirus aucalifornicae) belonging to the

Baculoviridae family. It infects 32 species of Lepidoptera and can infect commercially available insect cell lines derived from

Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf21 and the subclone Sf9) and

Trichoplusia ni (Tn-5) [

5]. The AcMNPV genome consists of a circular double-stranded DNA molecule of 134 kbp encoding around 155 predicted protein genes and is fully sequenced [

6]

– [

8]. The functions of several of its genes are still poorly understood, but they are generally believed to play a role in the virus’s ability to propagate [

9,

10]. In nature, baculoviruses mainly infect the larvae of their hosts when they feed on plants contaminated with the virus 11. During their biphasic viral cycle, some baculoviruses (including AcMNPV) produce two distinct phenotypes: occlusion-derived viruses (ODVs) and budded viruses (BVs). ODVs are involved in horizontal transmission between insects through protein structures known as occlusion bodies (OBs),where the virus is embedded. In contrast, BVs are responsible for spreading the infection from cell to cell 12. For biotechnological applications, it is important to note that BVs are the virions required for infecting cell cultures

in vitro. BVs can also be used to infect larvae via intrahemocoelic injections, making OBs unnecessary for BEVS.

The use of Lepidopteran larvae as “biofactories” has been explored as an alternative to cell cultivation. This host yields higher yields than insect cells at significantly low cost, due to the larvae’s minimal commercial value and low maintenance and breeding requirements [

13,

14]. Nowadays, several products for veterinary use manufactured using insect larvae are already available on the market. Despite the significant advantages of using larvae, insect cell cultivation remains the primarily accepted expression system to produce recombinant proteins for therapeutic purposes in human health [

15]. For all these reasons, the development and optimization of the platform should focus on protein production both in cultures and Lepidoptera larvae.

Considerable progress has been made in understanding baculovirus biology in recent decades. It has been demonstrated that 45% of the AcMNPV genome may be nonessential for BV production [

16,

17]. Specifically, genes coding for

per os infectivity factors (PIFs) and others associated with ODV envelope formation, as well as genes involved in OB formation, are only required for oral infection of insects, not for cell culture infection or the intrahemocoelic injection of Lepidoptera larvae [

12,

18]. Deletion of nonessential genes has been shown to improve the expression of recombinant proteins [

19]. There is significant potential to optimize this platform by obtaining minimized genomes, as these genes could hinder the production of recombinant proteins or compete for cellular resources [

20,

21].

Since the system’s development, AcMNPV has been genetically modified using various strategies to obtain more stable genomes and higher expression yields [

9]. In this sense, the deletion of genes coding for viral chitinase and cathepsin—both responsible for larval liquefaction—along with the deletion of nonessential genes associated with ODVs such as

p26,

p10,and

p74,has improved the quality and increased the expression levels of heterologous proteins produced in insect cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses [

20,

22]. Despite being a widely used method, the traditional techniques for genome manipulation based on homologous recombination are time-consuming and require several rounds of selection, which are imprecise and challenging, especially when large regions need to be removed [

23]. In particular, the λ Red recombination system is currently widely used to optimize the AcMNPV genome by eliminating nonessential genes for BV systemic infection or genes with unknown functions [

10,

17,

19,

24]

– [

27].

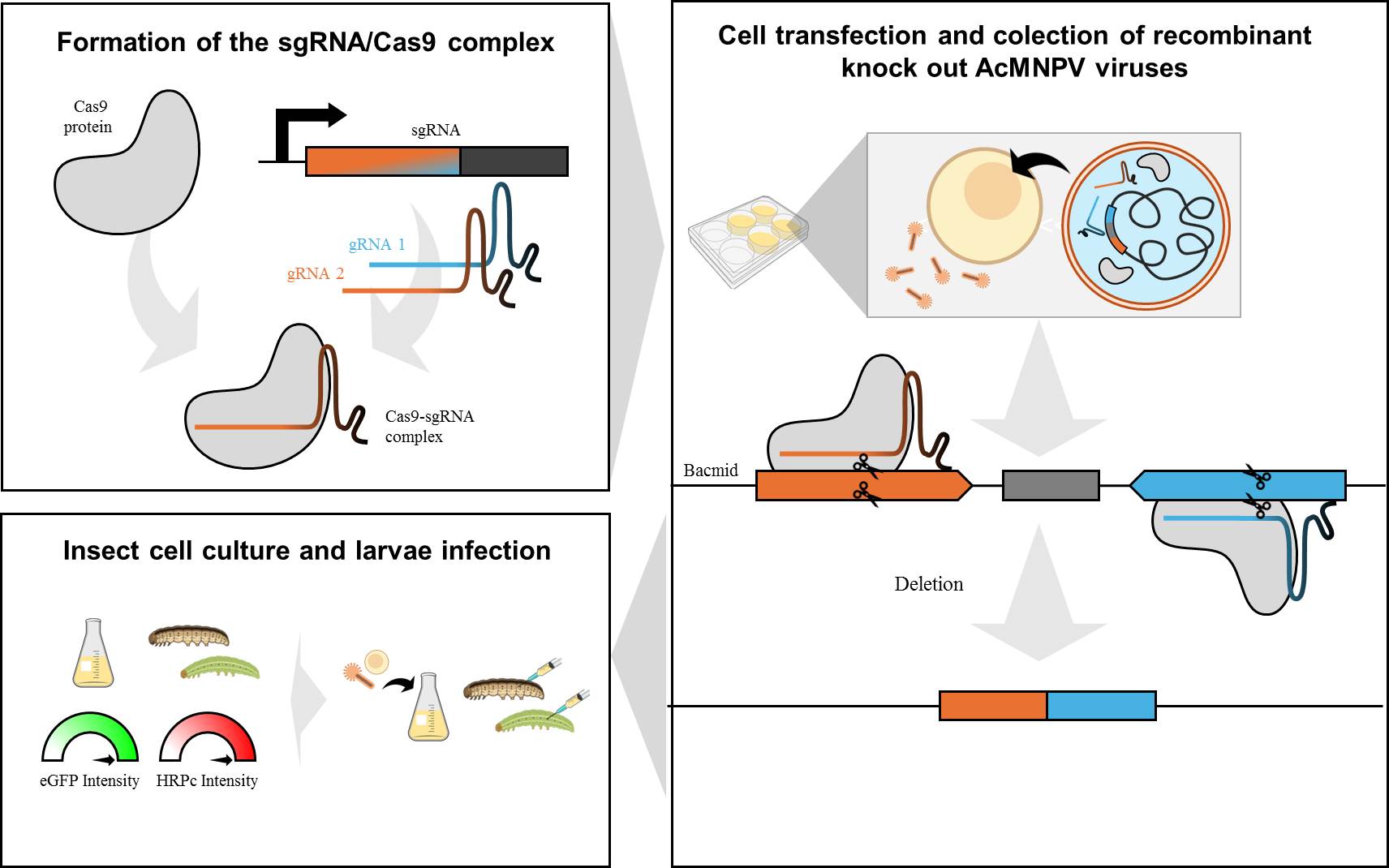

With the introduction of the CRISPR/Cas9 genome edition system in 2013,new opportunities have emerged in the field of biotechnology. This technology allows for easy and rapid editing of large viral genomes (mutations, insertions, deletions, and DNA additions) [

23]. The primary system consists of the Cas9 endonuclease from

Streptococcus pyogenes,which is capable of catalyzing the hydrolysis of double-stranded DNA, as well as a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs the Cas9 enzyme to a specific sequence for cleavage. The resulting damage to the double-stranded DNA molecule (DSB, for DNA double-strand break) is recognized and repaired by the cellular machinery [

7]. Recently, this technology has been applied for the first time to edit genes within the AcMNPV genome [

28,

29]. Unlike λ red recombinant systems, this strategy allows direct modification of the viral genome without requiring passage through bacteria. Additionally, it eliminates the use of antibiotics for mutant selection [

30]. Varying levels of success have been achieved depending on the gene, through the transfection of the Cas9-sgRNA complex in the presence of a single sgRNA. The resulting mutations consist of small insertions or deletions, leading to frameshift mutations and premature stop codons. These genetic disruptions are detectable only through sequencing and lead to pseudogenization [

7]. Improving this methodology using two customized sgRNAs could simultaneously knock out multiple tandem genes, including regulatory regions and promoters. This would prevent transcriptional complex formation and result in substantial energy savings for the cells. In addition, this strategy would allow the mutant virus to be detected with just a polymerase chain reaction assay (PCR). In this framework, we developed and validated a highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9 editing process to simultaneously remove baculovirus tandem nonessential genes for BV production, thereby improving the baculovirus genome and enhancing the expression of recombinant proteins in both insect cells and larvae.

4. Discussion

Synthetic biology in baculovirus research enables the design and optimization of viral genomes to enhance protein expression, improve infectivity, and eliminate unwanted functions for technological applications. Through precise genome editing, synthetic baculoviruses can serve as customized vectors for various biotechnological uses, including vaccine development, gene therapy, and recombinant protein production [

40]. A top-down synthetic biology approach offers the advantage of starting with a functional genome, allowing researchers to systematically remove nonessential elements while preserving key viral functions. This strategy ensures that any modifications that negatively affect viability can be reversed, optimizing the baculovirus for enhanced performance [

21].

Several attempts have been made to achieve the desired minimal baculovirus genome using these strategies and evaluating their impact on expression in insect cells [

9,

10,

41,

42]. Comparative genomics studies have identified at least 38 core genes in Baculoviridae family as essential for maintaining the baculovirus life cycle in nature [

8,

43,

44]. However, some of these genes are nonessential for BV production and are only required for ODV and OB generation [

16] as per os infectivity factors (PIF) or polyhedrin/granulin. Additionally, proteins that manipulate or affect the host, such as egt (

Ac126) and cathepsin (

Ac127),are not necessary for BV production [

45,

46]. These findings provide the basis for developing minimized genomes by deleting nonessential genes for BV generation and propagation, enabling the incorporation of more heterologous genes of interest and enhanced protein expression levels [

16]. Furthermore, transcriptomic data reveal that some of these nonessential genes exhibit high transcriptional activity [

35]. Therefore, these sequences can be targeted for removal in the context of baculovirus genome optimization to enhance recombinant protein production in the BEVS.

Advances in synthetic biology tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 have accelerated the development of baculovirus-based platforms with enhanced safety, efficiency, and versatility. The CRISPR/Cas9 system was first used successfully to edit the baculovirus genome using a single sgRNA, resulting in the generation of indels [

28]. Although this methodology was effective for generating knockouts, sequencing was the only reliable method for detecting mutations. Despite gene disruption, the transcriptional machinery continues to be recruited to the promoters, leading to unnecessary energy expenditure [

16]. Additionally, the presence of residual nucleotide sequences can still give rise to subgenomic regulatory elements [

47]

– [

49].

In this study, we evaluated the possibility of simultaneously editing the AcMNPV genome using Cas9 with two tandem sgRNAs, aiming to remove large DNA fragments that encode nonessential proteins for recombinant protein production in the BEVS. This strategy not only provides a rapid method for mutant detection by end-point PCR but also enables the removal of multiple tandem targets, while including promoters and regulatory regions. This facilitates the development of a minimal and optimized genome for recombinant protein production. To further enhance genome editing, we continued employing RNP delivery as previously described [

28]. This method offers distinct advantages over plasmid-based methods, including rapid nuclear access of Cas9,reduced off-target effects due to its short half-life, lower cellular toxicity, and the elimination of risks associated with prolonged expression or genomic integration. Furthermore, targeting the first generation of BVs increases the likelihood of recovering mutant variants by minimizing the dilution effect during subsequent amplification steps [

28,

50,

51]. This strategy also provides the opportunity to directly optimize the virus carrying the expression cassette or to generate an optimized, non-transposed viral genome that can be used to transform the E. coli DH10Bac

TM strain for the construction of new recombinant viral vectors.

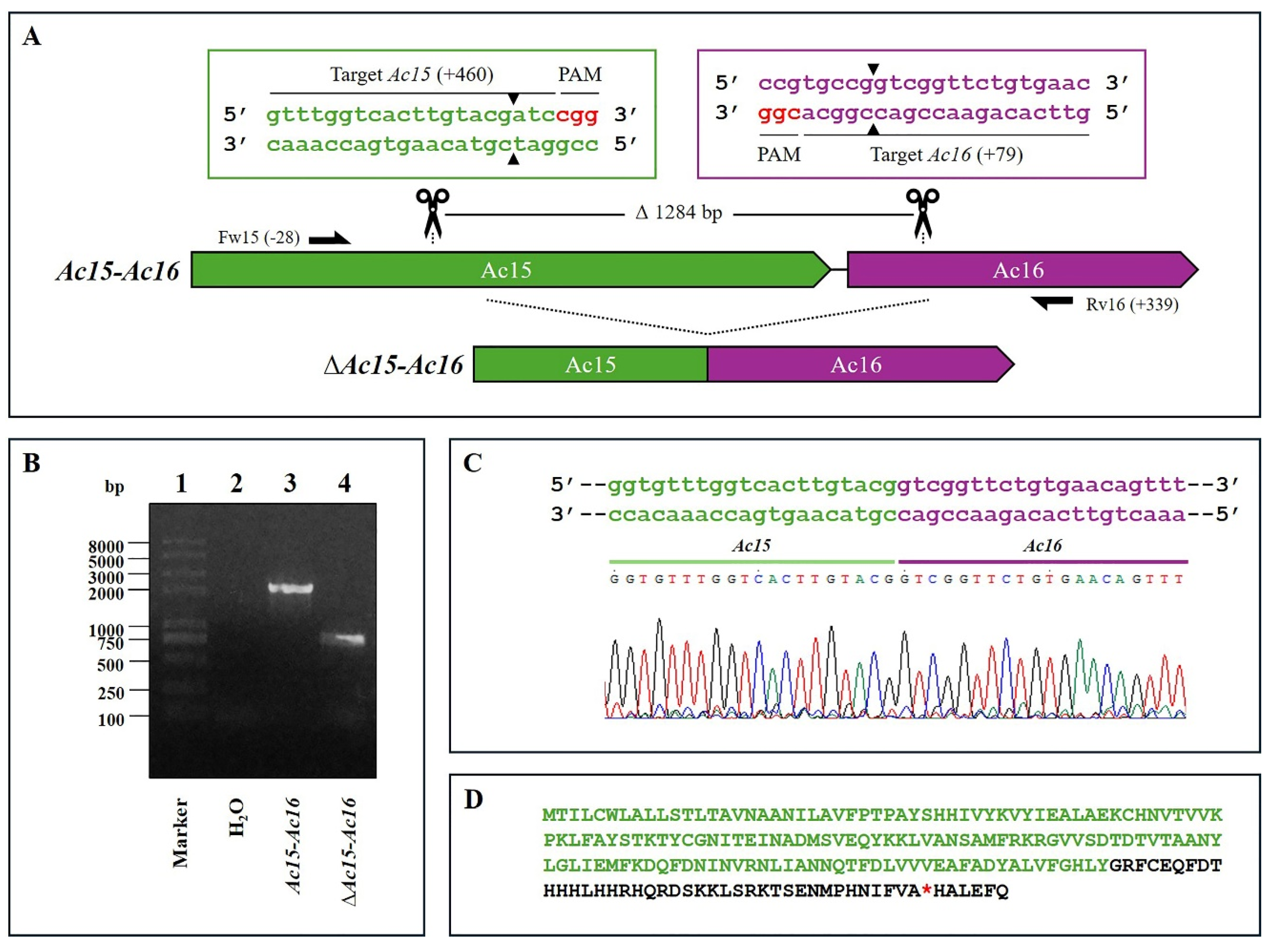

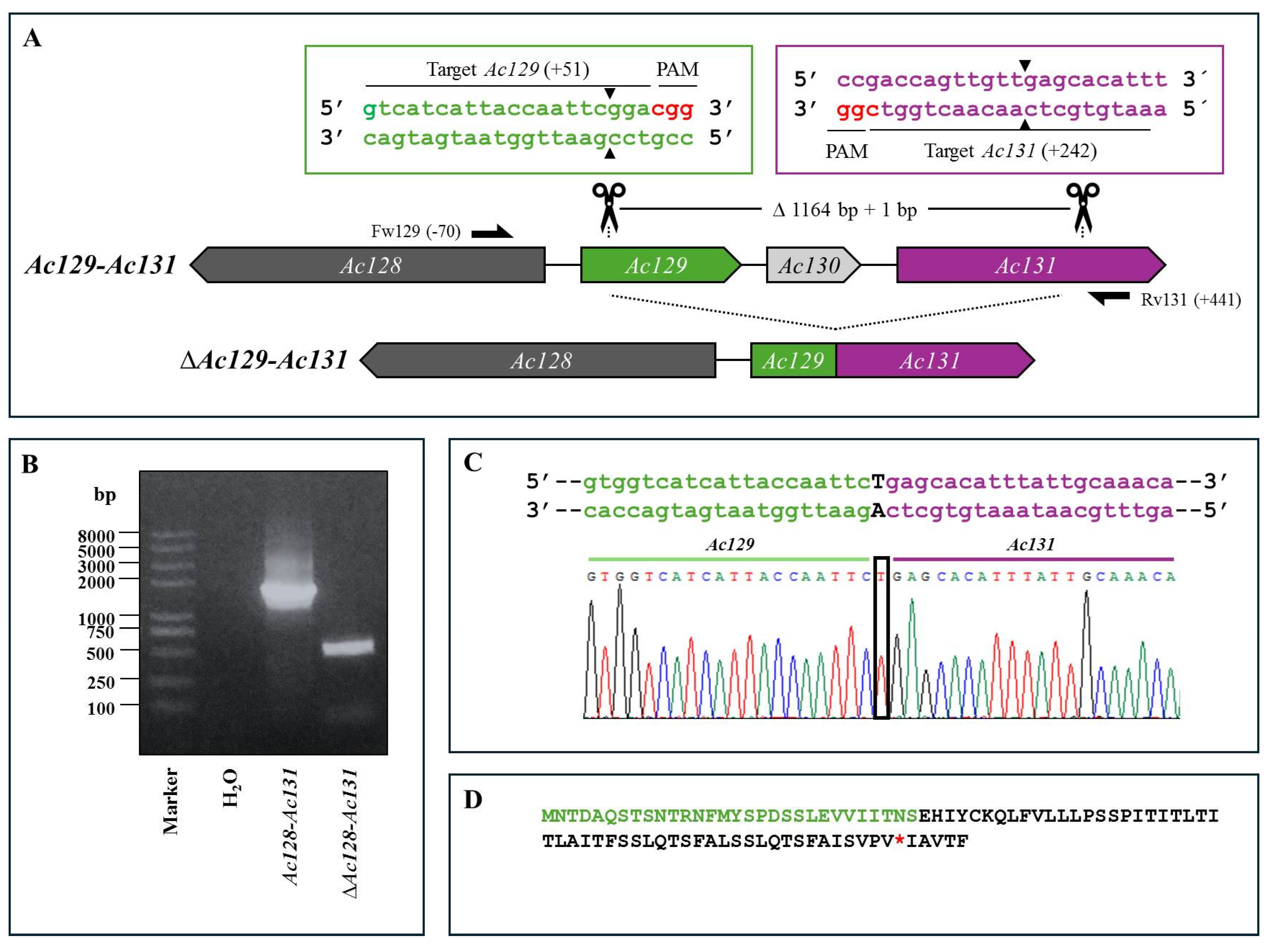

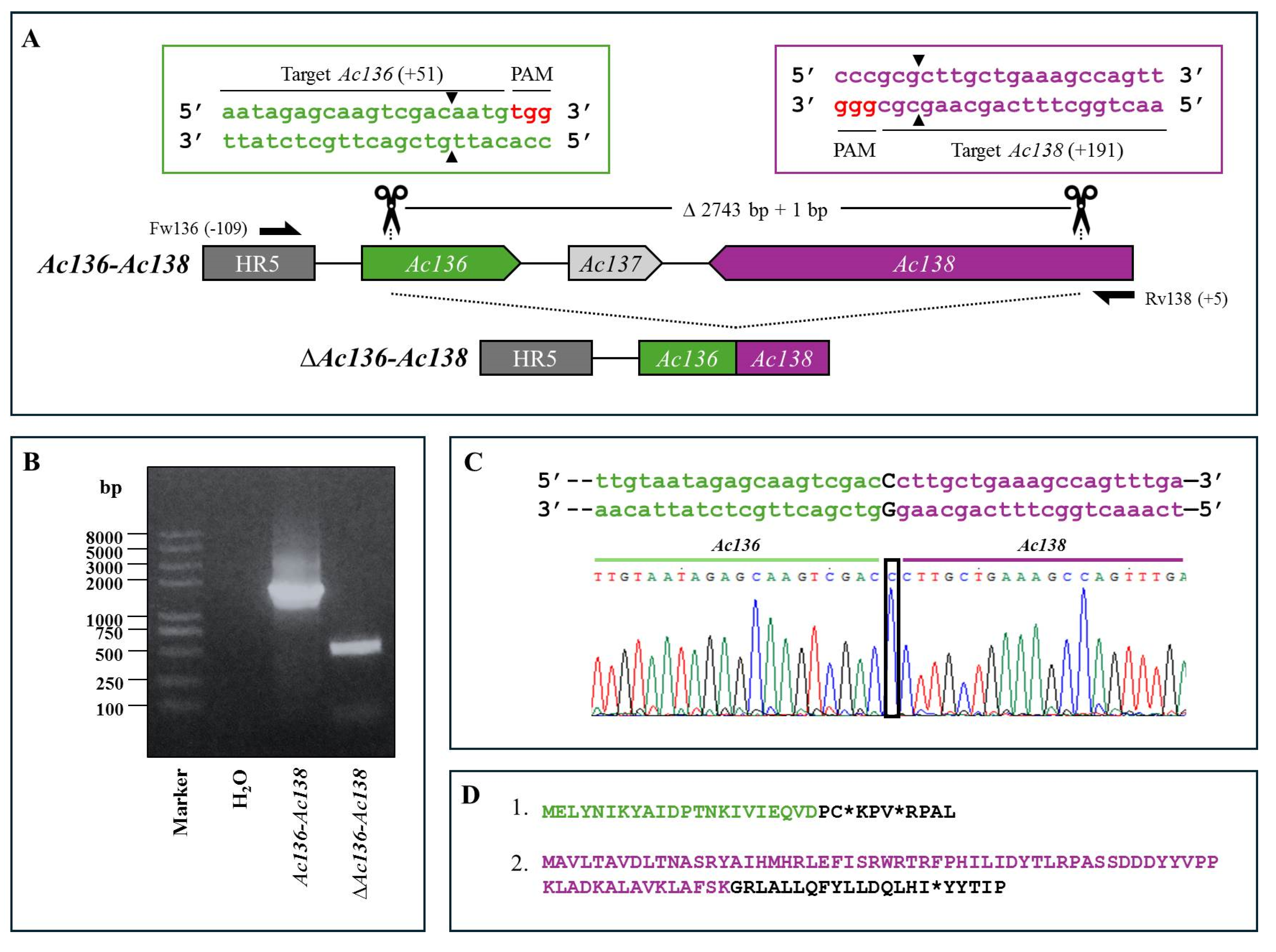

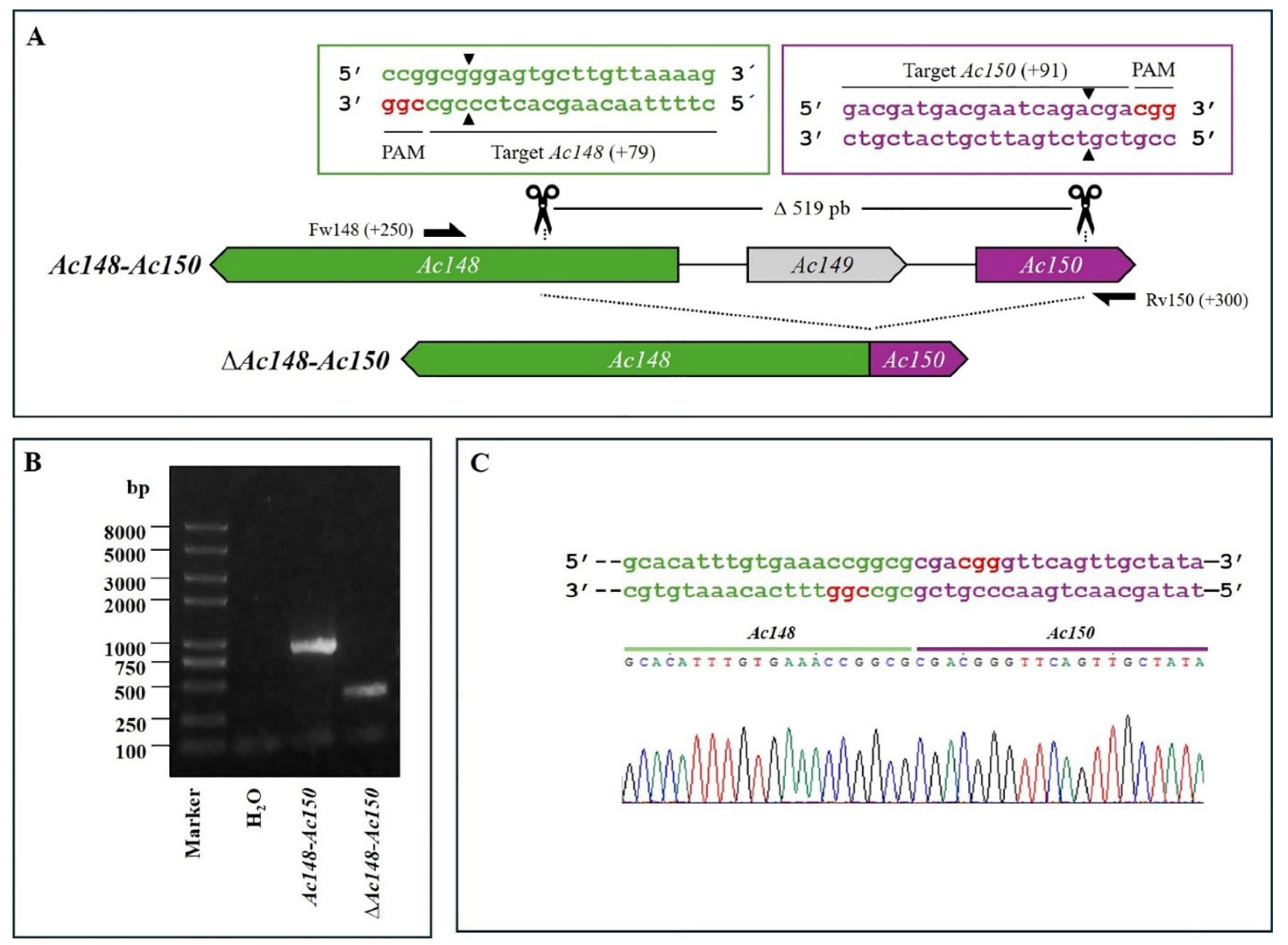

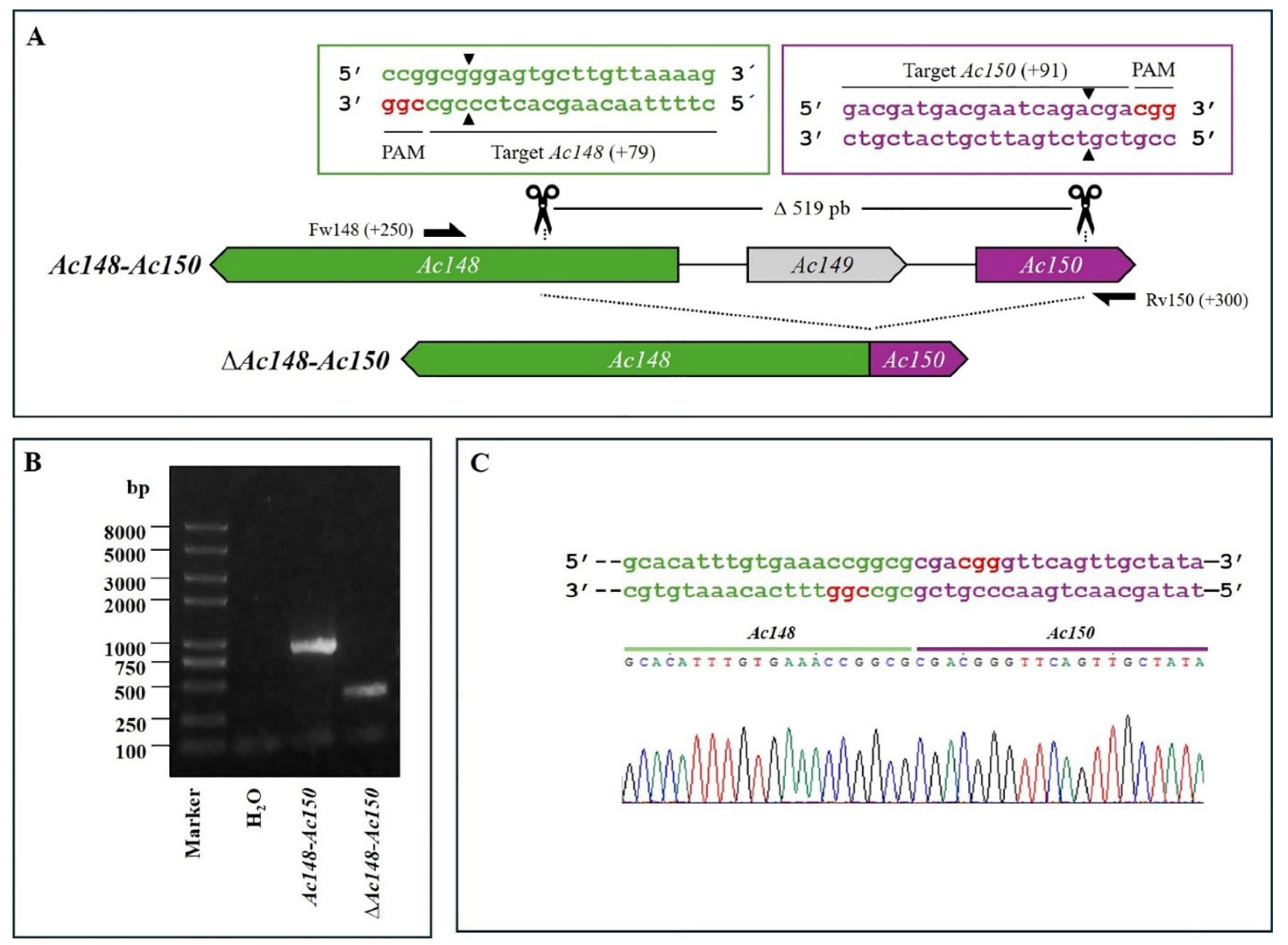

A total of eleven protein genes were edited, resulting in four AcMNPV knockout viruses

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]-Ac [16],

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [129]-Ac [131],

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [136]-Ac [138] and

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150]. All edited fragments exhibited the expected deletion upstream of the PAM site (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). A single nucleotide insertion was observed at the junction point between the two fragments in the editing target

Ac129–

Ac131,as well as in

Ac136–

Ac138. In some cases, deletion of the gene fragments resulted in pseudogenes formed by the fusion of the 5′ end of one coding sequence with the 3′ end of the adjacent gene, leading to frameshift mutations at the fusion point and the presence of premature stop codons in the predicted proteins when one of the promoter regions was retained. In other cases, a complete theoretical loss of translation occurred due to the removal of the promoter.

The mutant viruses were used to validate the editing methodology and, consequently, to evaluate their impact on foreign gene expression. For this purpose, Sf9 insect cells and

R. nu and

S. frugiperda larvae were infected with the recombinant viruses (edited or nonedited) carrying eGFP under the late viral p10 promoter and HRPc driven by the chimeric late viral

polh-pSeL promoter [

52]. Given that expression in larvae represents a cost-effective alternative for recombinant protein production, cultured cells are still the preferred host for therapeutically relevant proteins [

5]. In addition, gene deletions with distinct functions can differentially affect recombinant protein expression depending on the expression host [

10,

17]. This highlights the importance of evaluating their effects on protein expression in both insect cell lines and larvae.

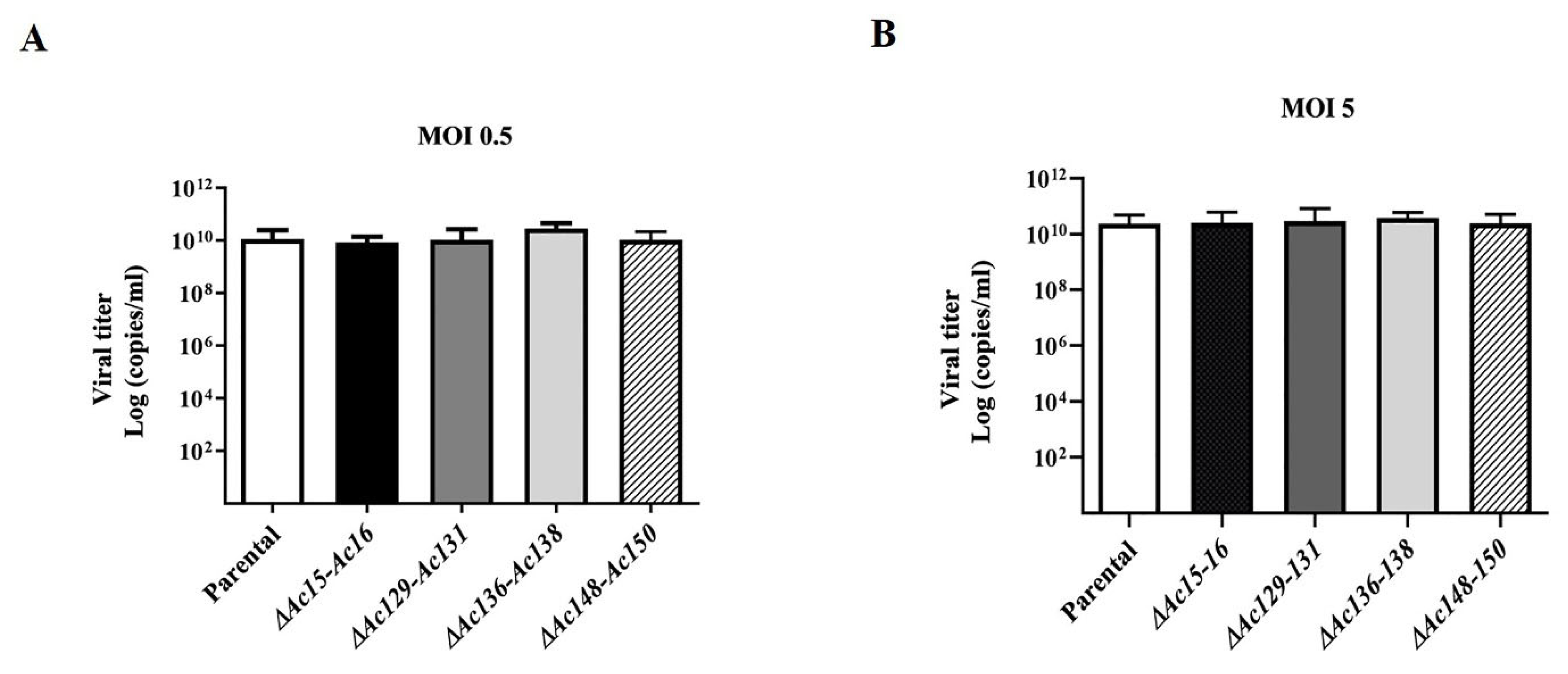

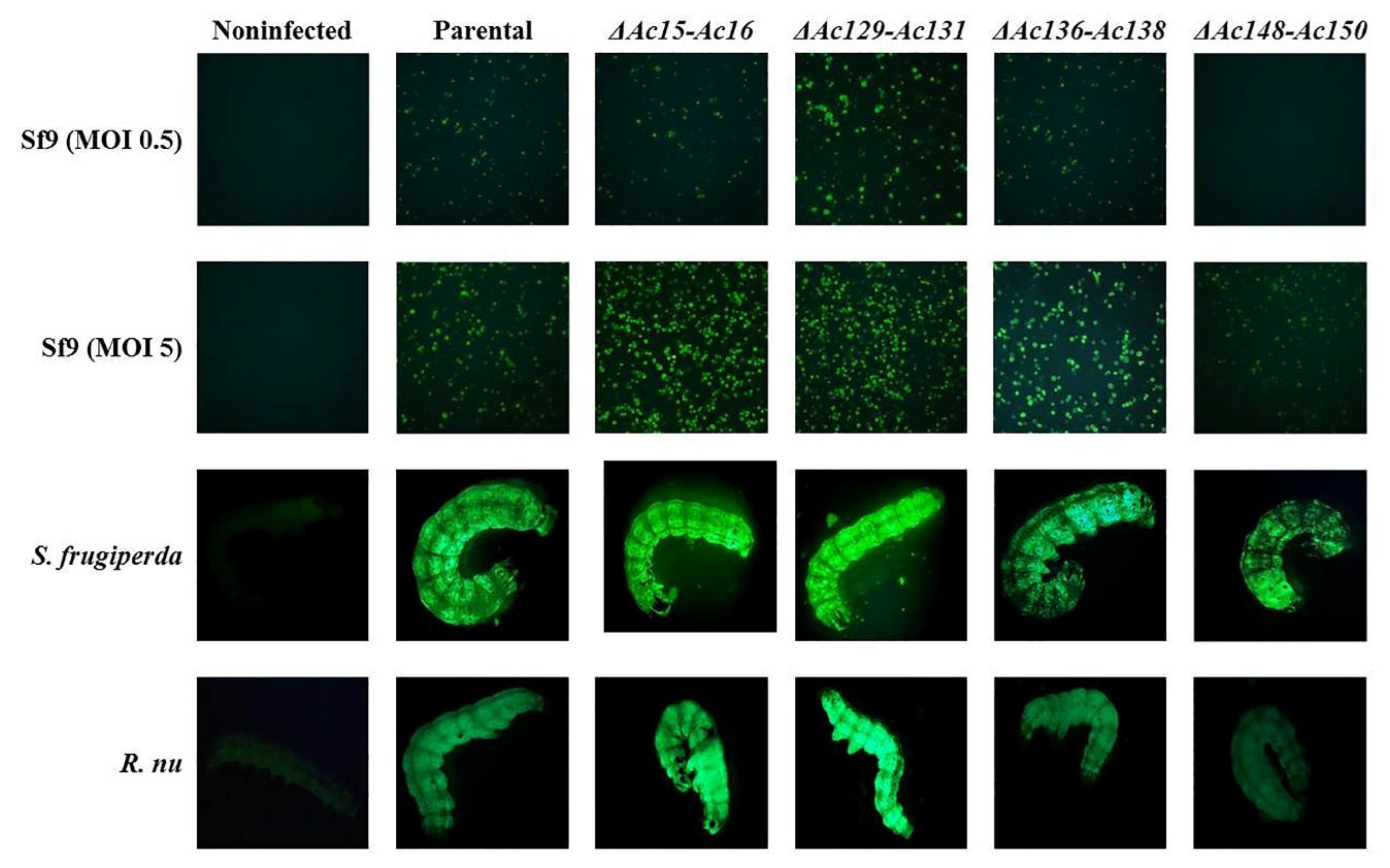

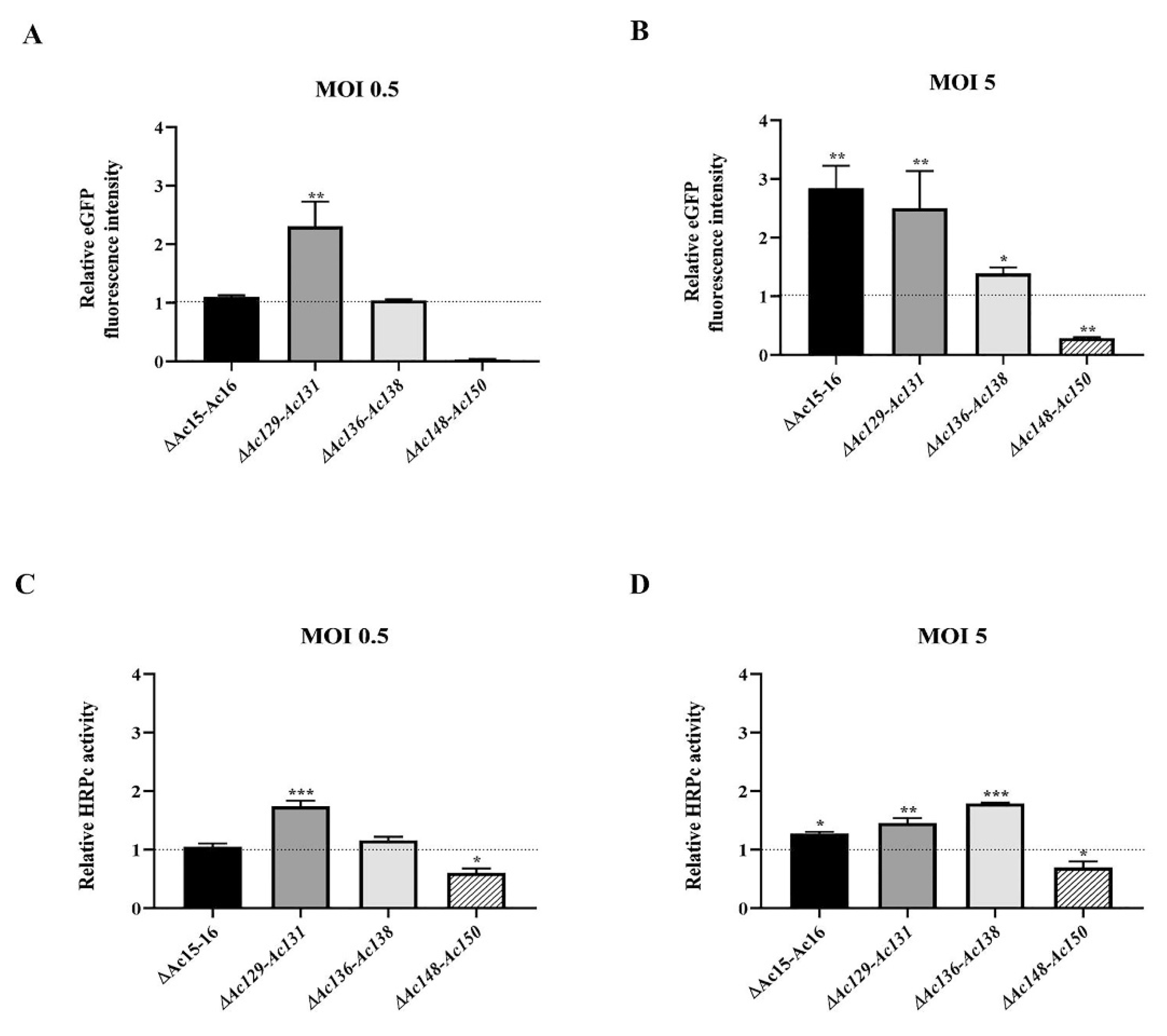

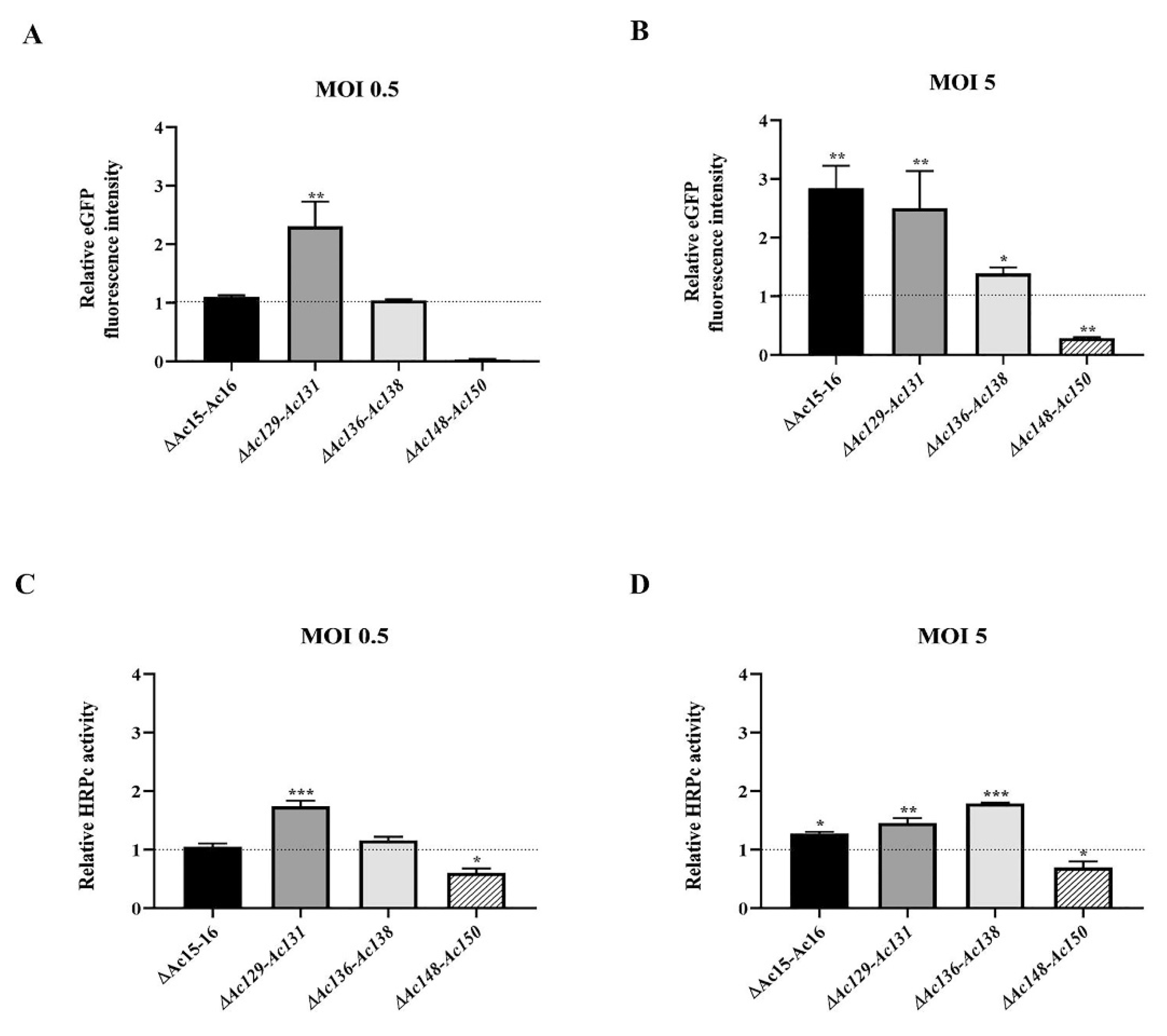

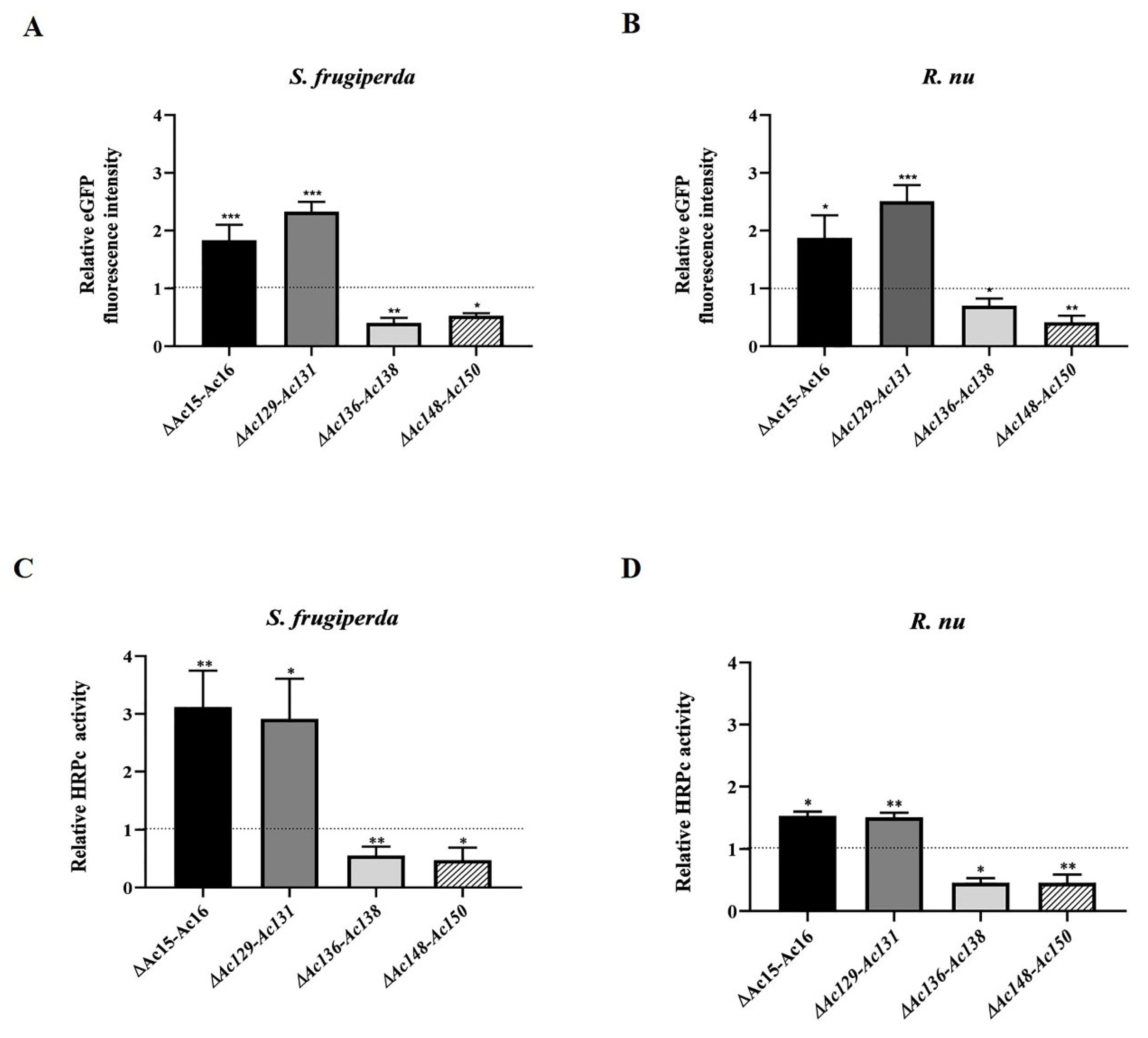

After expression, no significant difference in the final BV titer achieved by parental and mutant viruses was found, suggesting that the difference in expression is not influenced by virus replication and budding (

Figure 5). This is important because removing genome fragments may also eliminate sequences with unknown functions, such as miR genes or origin of replication, which could impact the viral cycle [

47,

48,

53]. In cell culture, moderate changes in expression were observed at MOI 0.5,whereas pronounced changes became evident at a higher MOI in most of the mutants evaluated. In larvae, the effects of these same mutant viruses closely mirrored those observed in cell culture at a higher MOI, except for

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆ [136]-Ac [138],which caused increased expression in cells but decreased expression in larvae (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). Notably, the effects of the mutations were independent of the nature of the expressed protein, whether intracellular (eGFP) or secreted (HRPc). The four gene deletions evaluated were found to have distinct effects on recombinant protein expression. Since the regulatory mechanisms by which these nonessential genes influence transgene expression driven by late viral promoters remain poorly understood, further functional studies will are required to elucidate their role in modulating recombinant expression in the AcMNPV syst

em [

26].

The first gene fragment selected for removal from the parental

Ac-eGFP/HRPc virus and used to validate the editing methodology using two gRNAs was the

Ac15 and

Ac16 ORFs.

Ac15,which encodes Ecdysteroid UDP-glucosyltransferase (egt),is involved in arresting the molting process and allows replication in infected larvae. Previous reports indicated that spontaneous deletions of

Ac15 during cell culture passage suggest that this gene is not essential for viral replication or survival [

12]. This ORF is located adjacent to

Ac16 (ODV-E26),a gene that encodes a structural protein associated with the envelopes of both BV and ODV [

54]. Although

Ac16 is involved in BV envelope formation, its deletion does not appear to affect their viability, likely because its function is compensated by the expression of other viral genes [

27]. Studies have demonstrated that the inactivation of

Ac15 and Ac16 produces infective BV. In this work, infections with the

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]-Ac [16] mutant viruses (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) led to enhanced protein expression under conditions evaluated in Sf9 cells infected at MOI 5 and larvae as the host, except in insect cells infected at MOI 0.5,where expression levels were comparable to the infection with the parental virus. This suggests that deleting this group of genes does not substantially affect expression at a low MOI. Previously,

Ac16 was individually edited by Cas9 using a single sgRNA. This editing resulted in a mutation that introduced a premature stop codon. While knockout of the

Ac16 gene did not appear to affect GFP expression in Sf21 cells, infection of

Spodoptera exigua larvae with the edited virus resulted in a 5-fold increase in protein production [

12,

28]. The strategy of simultaneously deleting more than one gene has already been reported [

10]. The deletion of

Ac15 and

Ac16 ORFs from the AcMNPV genome using the λ Red recombination benefited GFP expression in both Sf9 and High Five cells [

10]. Although the results obtained in the present study were similar to those previously reported in insect cells, it was possible to demonstrate how this modification affects larvae expression as well. In this study, the most pronounced increases in recombinant protein expression were observed when eGFP was expressed in cells infected at MOI of 5 and HRPc was expressed in

S. frugiperda larvae, with increases of 180% and 211%,respectively (

Table 3).

The second fragment selected in this study (

Ac129–

Ac131) encoded three proteins that are not essential for BV production:

Ac129 encodes a viral capsid protein (p24) found in ODV [

55];

Ac130 (gp16) is associated with nucleocapsid formation and its transport through the nuclear membrane, as well as with the movement of BV across the nuclear envelope and into the cytoplasm [

56]; and

Ac131 (Calyx; polyhedron envelope, PE; pp34) is associated with OB stability [

12]. Disruption of these three genes results in viable BV production at levels similar to those of the parental virus. In addition, deletion of

Ac130 has been linked to a delayed lethal effect in larvae [

56],which could be advantageous for recombinant protein production, as increased larval survival would allow for an extended production period of the target protein. In this study (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8); significant increases in eGFP yield were observed in cells infected at MOI 5,with a 150% enhancement, as well as in

R. nu and

S. frugiperda larvae, where yields rose by 133% and 150%,respectively (

Table 3).

In the case of HRPc,expression increased moderately in both Sf9 cells and

R. nu larvae. However, substantial enhancement was observed in

S. frugiperda larvae, with expression levels reaching up to 190% compared to the parental virus. These results are consistent with those reported, showing that deletion of this fragment significantly increased expression levels in Sf9 and High Five insect cells [

10].

Infections with the

Ac-eGFP/HRPcC∆Ac [136]-Ac [138] mutant were the only cases in which protein expression exhibited the opposite behavior in insect cells and larvae (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). In cells, this mutant moderately increased the expression of both studied proteins under most conditions evaluated, except for eGFP expression at MOI 0.5,which was comparable to the parental infection with

Ac-eGFP/HRPc. In contrast, the expression of recombinant proteins was significantly reduced in both larval hosts. This mutated virus includes the deletion of the

Ac136,

Ac137,and

Ac138 genes. The

Ac136 gene encodes the p26 protein, whose function remains uncharacterized. It is a secondary gene that does not influence transmission, infectivity, or production of both BV and OB. For this reason, its inactivation results in a viable virus capable of infecting insect cell culture and larvae, indicating that it is a nonessential gene for systemic infection mediated by BVs [

57]. Then,

Ac137 encodes the highly expressed p10 protein, which, together with PEP, is associated with the polyhedron and plays a role in its stability. It has been observed that removal of the p10 protein does not compromise BV infectivity or replication, confirming it is a nonessential gene [

58]. However, deleting it dramatically reduces virus occlusion efficiency [

59]. Since p10 is highly expressed, its removal reduces competition with strong promoters that regulate recombinant protein expression [

12]. Moreover,10 proteins have been identified as essential only for oral infection and are defined as PIFs [

60]. One of these proteins is codified by the

Ac138 gene, which encodes p74 (PIF-0). This protein is fundamental for midgut cell larva oral infection through ODV, but it is dispensable for virus propagation in cell culture or systemic infection in larvae [

29,

61]. The simultaneous expression of the three proteins ensures correct virion occlusion within the polyhedra. The commercial vector FlashBacUltra (OET) was designed with deletions of these three nonessential genes for BV production [

12]. In our study, the deletion of the

Ac136–

Ac138 fragment resulted in enhanced expression exclusively in Sf9 cells infected at MOI 5,whereas a significant reduction in expression was observed in both insect larval hosts. The partial deletion of the

Ac136–

Ac138 fragment has been reported to positively impact the expression of recombinant proteins in the system [

62]. However, it has been demonstrated that the viruses are affected when the complete coding sequence of

Ac136 and

Ac138 is deleted [

19]. In contrast, the complete deletion of

Ac137 showed no significant differences compared to the control virus [

9]. In

Ac136,the deletion might be affecting a regulatory element such as HR5,while in

Ac138,it could be impacting the expression of the neighboring essential gene,

Ac139,which encodes ME53. In the present study, special attention was given to neighboring genes and genetic elements. Despite this, expression was increased in cells; however, the negative impact on larvae persisted. Further studies on

Ac136 and

Ac137 are needed to determine why its deletion may be impacting expression in larvae.

Finally, the

Ac148-

Ac150 fragment was removed from the parental virus. The

Ac148 (encoding PIF-5/ODV-E56) and

Ac150 genes encode proteins associated with the envelopes of both ODV and BV. However, their absence dramatically reduces ODV oral infectivity in larvae, while maintaining comparable infectivity to the wild type when BVs are used to infect insect cells in culture or larvae via intrahemocoelic injection [

63]. PIF-5 is specifically involved in oral infectivity. The third gene deleted in this fragment group was

Ac149. Although little is known about this gene in AcMNPV, studies in related baculoviruses, such as in the nucleopolyhedrovirus of Bombyx mori (

BmNPV),suggest that it may not be essential [

12]. In our study, infections with the

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150] mutant led to significantly decreased expression in all studied cases (

Figure 6,

Figure 7). Individual gene deletions had no effect on protein expression [

9]. However, it was demonstrated that simultaneously removing all three genes negatively impacts protein expression in insect cells, although these mutant viruses exhibit a replicative behavior similar to the nonedited parental virus [

10]. In the present study, this negative effect was also observed in insect larvae. This finding reinforces the importance of considering synergistic gene functions and regulatory context in genome minimization efforts.

Figure 1.

CRISPR Dual-sgRNA Knockout of Ac15–Ac16 in Bac-eGFP/HRPc. A) Schematic representation of the Ac15–Ac16 genomic locus before and after CRISPR editing. The Ac15 and Ac16 are represented in green and purple, respectively. After deletion of the Ac15–Ac16 fragment, the resulting pseudogene consists of the 5′ portion of Ac15 (green) and the 3′ portion of Ac16 (purple). Gene-specific primers used for PCR are indicated by black arrows. DNA excision is marked with scissors and a triangle (▲). The hybridization positions of primers and sgRNA targets are shown in parentheses, using the ATG start codon of each ORF as the reference point. PAM sequences (red nucleotides) are highlighted. B) Identification of edited clones by PCR using specific primers (Fw-Ac15 and Rv-Ac16). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPc” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the unedited parental virus (2033 bp). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPcΔAc [15]–Ac [16]” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the edited virus (749 bp). Marker: Trans 2K Plus (TransGen Biotech, Beijin, China). C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the edited virus. Only the flanking regions of the knockout are shown. D) Amino acid sequence of the truncated aberrant protein originating from the fusion of Ac15 and Ac16. The conserved N-terminal region from Ac15 is shown in green, followed by a frameshift-derived sequence that leads to a premature stop codon (*). Not at scale.

Figure 1.

CRISPR Dual-sgRNA Knockout of Ac15–Ac16 in Bac-eGFP/HRPc. A) Schematic representation of the Ac15–Ac16 genomic locus before and after CRISPR editing. The Ac15 and Ac16 are represented in green and purple, respectively. After deletion of the Ac15–Ac16 fragment, the resulting pseudogene consists of the 5′ portion of Ac15 (green) and the 3′ portion of Ac16 (purple). Gene-specific primers used for PCR are indicated by black arrows. DNA excision is marked with scissors and a triangle (▲). The hybridization positions of primers and sgRNA targets are shown in parentheses, using the ATG start codon of each ORF as the reference point. PAM sequences (red nucleotides) are highlighted. B) Identification of edited clones by PCR using specific primers (Fw-Ac15 and Rv-Ac16). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPc” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the unedited parental virus (2033 bp). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPcΔAc [15]–Ac [16]” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the edited virus (749 bp). Marker: Trans 2K Plus (TransGen Biotech, Beijin, China). C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the edited virus. Only the flanking regions of the knockout are shown. D) Amino acid sequence of the truncated aberrant protein originating from the fusion of Ac15 and Ac16. The conserved N-terminal region from Ac15 is shown in green, followed by a frameshift-derived sequence that leads to a premature stop codon (*). Not at scale.

Figure 2.

CRISPR Dual-sgRNA Knockout of Ac129–Ac131 in Bac-eGFP/HRPc. A) Schematic representation of Ac129–Ac131 genomic locus before and after CRISPR editing. The non-edited Ac128 is shown as a dark grey arrow, while Ac129,Ac130,and Ac131 are represented in green, light gray, and purple, respectively. After deletion of the Ac129–Ac131 fragment, the resulting pseudogene consists of the 5′ portion of Ac129 (green) and the 3′ portion of Ac131 (purple). Ac130 (light grey) is completely removed. Gene-specific primers used for PCR are indicated by black arrows. DNA excision is marked with scissors and a triangle (▲). The hybridization positions of primers and sgRNA targets are shown in parentheses (+/-),using the ATG start codon of each ORF as the reference point. PAM sequences (red nucleotides) are highlighted. B) Identification of edited clones by PCR using specific primers (Fw-Ac129 and Rv-Ac131). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPc” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the unedited parental virus (1733 bp). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPcΔAc [129]–Ac [131]” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the edited virus (569 bp). Marker: Trans 2K Plus (TransGen Biotech). C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the edited virus. Only the flanking regions of the knockout are shown. A single nucleotide insertion (T) at the fusion is indicated with a square. D) Amino acid sequence of the truncated aberrant protein originating from the junction of Ac129 and Ac131. The conserved N-terminal region from Ac129 is shown in green, followed by a frameshift-derived sequence that leads to a premature stop codon (*). Not at scale.

Figure 2.

CRISPR Dual-sgRNA Knockout of Ac129–Ac131 in Bac-eGFP/HRPc. A) Schematic representation of Ac129–Ac131 genomic locus before and after CRISPR editing. The non-edited Ac128 is shown as a dark grey arrow, while Ac129,Ac130,and Ac131 are represented in green, light gray, and purple, respectively. After deletion of the Ac129–Ac131 fragment, the resulting pseudogene consists of the 5′ portion of Ac129 (green) and the 3′ portion of Ac131 (purple). Ac130 (light grey) is completely removed. Gene-specific primers used for PCR are indicated by black arrows. DNA excision is marked with scissors and a triangle (▲). The hybridization positions of primers and sgRNA targets are shown in parentheses (+/-),using the ATG start codon of each ORF as the reference point. PAM sequences (red nucleotides) are highlighted. B) Identification of edited clones by PCR using specific primers (Fw-Ac129 and Rv-Ac131). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPc” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the unedited parental virus (1733 bp). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPcΔAc [129]–Ac [131]” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the edited virus (569 bp). Marker: Trans 2K Plus (TransGen Biotech). C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the edited virus. Only the flanking regions of the knockout are shown. A single nucleotide insertion (T) at the fusion is indicated with a square. D) Amino acid sequence of the truncated aberrant protein originating from the junction of Ac129 and Ac131. The conserved N-terminal region from Ac129 is shown in green, followed by a frameshift-derived sequence that leads to a premature stop codon (*). Not at scale.

Figure 3.

CRISPR Dual-sgRNA Knockout of Ac136–Ac138 in Bac-eGFP/HRPc. A) Schematic representation of the Ac136–Ac138 genomic locus before and after CRISPR editing. The non-edited HR5 is shown as a dark grey arrow, while Ac136,Ac137 and Ac138 are represented in green, ligth gray, and purple, respectively. After deletion of the Ac136–Ac138 fragment, the resulting pseudogene consists of the 5′ portion of Ac136 (green) and the 3′ portion of Ac138 (purple). Ac137 (light grey) is completely removed. Gene-specific primers used for PCR are indicated by black arrows. DNA excision is marked with scissors and a triangle (▲). The hybridization positions of primers and sgRNA targets are shown in parentheses, using the ATG start codon of each ORF as the reference point. PAM sequences (red nucleotides) are highlighted. B) Identification of edited clones by PCR using specific primers (Fw-Ac136 and Rv-Ac138). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPc” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the unedited parental virus (3234 bp). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPcΔAc [129]–Ac [131]” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the edited virus (379 bp). Marker: Trans 2K Plus (TransGen Biotech). C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the edited virus. Only the flanking regions of the knockout are shown. A single nucleotide insertion (c) at the junction is indicated with a square. D) Amino acid sequence of the truncated aberrant protein originating from the fusion of Ac136 and Ac138. 1. The conserved N-terminal region from Ac129 is shown in green, followed by a frameshift-derived sequence that leads to a premature stop codon (*). 2. The conserved N-terminal region from Ac138 is shown in green, followed by a frameshift-derived sequence that leads to a premature stop codon (*). Not at scale.

Figure 3.

CRISPR Dual-sgRNA Knockout of Ac136–Ac138 in Bac-eGFP/HRPc. A) Schematic representation of the Ac136–Ac138 genomic locus before and after CRISPR editing. The non-edited HR5 is shown as a dark grey arrow, while Ac136,Ac137 and Ac138 are represented in green, ligth gray, and purple, respectively. After deletion of the Ac136–Ac138 fragment, the resulting pseudogene consists of the 5′ portion of Ac136 (green) and the 3′ portion of Ac138 (purple). Ac137 (light grey) is completely removed. Gene-specific primers used for PCR are indicated by black arrows. DNA excision is marked with scissors and a triangle (▲). The hybridization positions of primers and sgRNA targets are shown in parentheses, using the ATG start codon of each ORF as the reference point. PAM sequences (red nucleotides) are highlighted. B) Identification of edited clones by PCR using specific primers (Fw-Ac136 and Rv-Ac138). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPc” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the unedited parental virus (3234 bp). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPcΔAc [129]–Ac [131]” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the edited virus (379 bp). Marker: Trans 2K Plus (TransGen Biotech). C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the edited virus. Only the flanking regions of the knockout are shown. A single nucleotide insertion (c) at the junction is indicated with a square. D) Amino acid sequence of the truncated aberrant protein originating from the fusion of Ac136 and Ac138. 1. The conserved N-terminal region from Ac129 is shown in green, followed by a frameshift-derived sequence that leads to a premature stop codon (*). 2. The conserved N-terminal region from Ac138 is shown in green, followed by a frameshift-derived sequence that leads to a premature stop codon (*). Not at scale.

Figure 4.

CRISPR Dual-sgRNA Knockout of Ac148-Ac150 in Bac-eGFP/HRPc. A) Schematic representation of Ac148–Ac150 genomic locus before and after CRISPR editing. The edited Ac148,Ac149 and Ac150 are represented in green, light gray and purple, respectively. After deletion of the Ac148-Ac150 fragment, the resulting pseudogene is composed of the 5′ portion of Ac148 (green) and the 3′ portion of Ac150 (purple). Ac149 (light grey) is completely removed. Gene-specific primers used for PCR are indicated by black arrows. DNA excision is marked with scissors and a triangle (▲). The hybridization positions of primers and sgRNA targets are shown in parentheses, using the ATG start codon of each ORF as the reference point. PAM sequences (red nucleotides) are highlighted. B) Identification of edited clones by PCR using specific primers (Fw-Ac148 and Rv-Ac150). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPc” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the unedited parental virus (885 bp). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPcΔAc [129]–Ac [131]” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the edited mutant virus (365 bp). Marker: Trans 2K Plus (TransGen Biotech). C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the edited virus. Only the flanking regions of the knockout are shown. Not at scale.

Figure 4.

CRISPR Dual-sgRNA Knockout of Ac148-Ac150 in Bac-eGFP/HRPc. A) Schematic representation of Ac148–Ac150 genomic locus before and after CRISPR editing. The edited Ac148,Ac149 and Ac150 are represented in green, light gray and purple, respectively. After deletion of the Ac148-Ac150 fragment, the resulting pseudogene is composed of the 5′ portion of Ac148 (green) and the 3′ portion of Ac150 (purple). Ac149 (light grey) is completely removed. Gene-specific primers used for PCR are indicated by black arrows. DNA excision is marked with scissors and a triangle (▲). The hybridization positions of primers and sgRNA targets are shown in parentheses, using the ATG start codon of each ORF as the reference point. PAM sequences (red nucleotides) are highlighted. B) Identification of edited clones by PCR using specific primers (Fw-Ac148 and Rv-Ac150). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPc” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the unedited parental virus (885 bp). The lane labeled “Ac-eGFP/HRPcΔAc [129]–Ac [131]” corresponds to the PCR product amplified from the edited mutant virus (365 bp). Marker: Trans 2K Plus (TransGen Biotech). C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the edited virus. Only the flanking regions of the knockout are shown. Not at scale.

Figure 5.

Effect of genome editing on AcMNPV replication. Supernatants were collected from Sf9 cell cultures, derived from cells infected with mutants of AcMNPV (Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]-Ac [16],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [129]-Ac [131],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [136]-Ac [138],and Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150],mentioned as ∆Ac15-Ac16,∆Ac129-Ac131,∆Ac136-Ac138 and ∆Ac148-Ac150 in histograms, respectively) at MOI 0.5 (A) and 5 (B) 72 h post-infection. Final BV titers (represented as genome copies x mL) were estimated using qPCR. The nonedited virus (Ac-eGFP/HRPc,“Parental” in histograms) was included as the reference. The average values of three replicates are indicated, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. No statistically significant differences were observed.

Figure 5.

Effect of genome editing on AcMNPV replication. Supernatants were collected from Sf9 cell cultures, derived from cells infected with mutants of AcMNPV (Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]-Ac [16],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [129]-Ac [131],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [136]-Ac [138],and Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150],mentioned as ∆Ac15-Ac16,∆Ac129-Ac131,∆Ac136-Ac138 and ∆Ac148-Ac150 in histograms, respectively) at MOI 0.5 (A) and 5 (B) 72 h post-infection. Final BV titers (represented as genome copies x mL) were estimated using qPCR. The nonedited virus (Ac-eGFP/HRPc,“Parental” in histograms) was included as the reference. The average values of three replicates are indicated, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. No statistically significant differences were observed.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence microscopy of Sf9 cells and larvae, expressing eGFP after infection with parental (Ac-eGFP/HRPc) or edited recombinant AcMNPV (Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]-Ac [16],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [129]-Ac [131],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [136]-Ac [138],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150],mentioned as ∆Ac15-Ac16,∆Ac129-Ac131,∆Ac136-Ac138 and ∆Ac148-Ac150,respectively). First and second row of photographs: representative photographs (40X) of Sf9 cells infected at MOI 0.5 (First row) and MOI 5 (Second row) at 3 dpi. An image from non-infected cells is included. Third and fourth row of photographs: representative photographs (8X) of S. frugiperda (third row) and R. nu larvae (fourth row) at 4 dpi. An image from non-infected larvae is included.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence microscopy of Sf9 cells and larvae, expressing eGFP after infection with parental (Ac-eGFP/HRPc) or edited recombinant AcMNPV (Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]-Ac [16],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [129]-Ac [131],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [136]-Ac [138],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150],mentioned as ∆Ac15-Ac16,∆Ac129-Ac131,∆Ac136-Ac138 and ∆Ac148-Ac150,respectively). First and second row of photographs: representative photographs (40X) of Sf9 cells infected at MOI 0.5 (First row) and MOI 5 (Second row) at 3 dpi. An image from non-infected cells is included. Third and fourth row of photographs: representative photographs (8X) of S. frugiperda (third row) and R. nu larvae (fourth row) at 4 dpi. An image from non-infected larvae is included.

Figure 7.

Effect of genome editing on eGFP and HRPC expression in Sf9 cells. A-B: Analysis of eGFP expression level in Sf9 cells infected at MOI 0.5 (A) and 5 (B) with the different edited AcMNPV (Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]-Ac [16],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [129]-Ac [131],Ac-eGFP/HRPcC∆Ac [136]-Ac [138],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150],mentioned as ∆Ac15-Ac16,∆Ac129-Ac131,∆Ac136-Ac138 and ∆Ac148-Ac150,respectively). The eGFP production was measured as relative fluorescence intensity 72 h after infection. The results are expressed as the relative eGFP fluorescence intensity, with a value of 1 corresponding to the parental virus (nonedited,Ac-eGFP/HRPc). C-D: Analysis of HRPc expression level in SF9 cells infected at MOI 0.5 (C) and 5 (D) with the different edited AcMNPV. The HRPc production was measured as relative activity (U/mL) at 96 h after infection. The results are expressed as the relative HRPc activity, with a value of 1 corresponding to the parental virus (nonedited,Ac-eGFP/HRPc). The values are the means of at least three independent assays. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Columns with an asterisk were significantly different. *: p<0.05; **p<0.01,***p<0.001.

Figure 7.

Effect of genome editing on eGFP and HRPC expression in Sf9 cells. A-B: Analysis of eGFP expression level in Sf9 cells infected at MOI 0.5 (A) and 5 (B) with the different edited AcMNPV (Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]-Ac [16],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [129]-Ac [131],Ac-eGFP/HRPcC∆Ac [136]-Ac [138],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150],mentioned as ∆Ac15-Ac16,∆Ac129-Ac131,∆Ac136-Ac138 and ∆Ac148-Ac150,respectively). The eGFP production was measured as relative fluorescence intensity 72 h after infection. The results are expressed as the relative eGFP fluorescence intensity, with a value of 1 corresponding to the parental virus (nonedited,Ac-eGFP/HRPc). C-D: Analysis of HRPc expression level in SF9 cells infected at MOI 0.5 (C) and 5 (D) with the different edited AcMNPV. The HRPc production was measured as relative activity (U/mL) at 96 h after infection. The results are expressed as the relative HRPc activity, with a value of 1 corresponding to the parental virus (nonedited,Ac-eGFP/HRPc). The values are the means of at least three independent assays. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Columns with an asterisk were significantly different. *: p<0.05; **p<0.01,***p<0.001.

Figure 8.

Effect of genome editing on eGFP and HRPc expression in larvae. A-B: Analysis of eGFP expression level in S. frugiperda (A) and R. nu larvae (B) infected with the different edited AcMNPVs (Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]Ac [16],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [129]Ac- [131],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [136]-Ac [138], Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150],mentioned as ∆Ac15-Ac16,∆Ac129-Ac131,∆Ac136-Ac138 and ∆Ac148-Ac150,respectively). The eGFP expression was measured as relative fluorescence intensity 72 h after infection. The results are expressed as the relative eGFP fluorescence intensity, with a value of 1 obtained from with the parental virus (nonedited,Ac-eGFP/HRPC). C-D: Analysis of HRPc expression level in S. frugiperda (C) and R. nu (D) larvae infected with the different edited AcMNPVs. The HRPc production was measured as activity (U/mL) 96 h after infection. The results are expressed as the relative HRPc activity, with a value of 1 obtained with the parental virus (nonedited). The values are the means of at least ten independent assays. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Columns with an asterisk were significantly different. *: p<0.05; **p<0.01; *** p< 000.1.

Figure 8.

Effect of genome editing on eGFP and HRPc expression in larvae. A-B: Analysis of eGFP expression level in S. frugiperda (A) and R. nu larvae (B) infected with the different edited AcMNPVs (Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [15]Ac [16],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [129]Ac- [131],Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [136]-Ac [138], Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac [148]-Ac [150],mentioned as ∆Ac15-Ac16,∆Ac129-Ac131,∆Ac136-Ac138 and ∆Ac148-Ac150,respectively). The eGFP expression was measured as relative fluorescence intensity 72 h after infection. The results are expressed as the relative eGFP fluorescence intensity, with a value of 1 obtained from with the parental virus (nonedited,Ac-eGFP/HRPC). C-D: Analysis of HRPc expression level in S. frugiperda (C) and R. nu (D) larvae infected with the different edited AcMNPVs. The HRPc production was measured as activity (U/mL) 96 h after infection. The results are expressed as the relative HRPc activity, with a value of 1 obtained with the parental virus (nonedited). The values are the means of at least ten independent assays. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Columns with an asterisk were significantly different. *: p<0.05; **p<0.01; *** p< 000.1.

Table 1.

Summary of PCR primers employed in the study.

Table 1.

Summary of PCR primers employed in the study.

| Name |

Sequence (5-3´) |

| Fw-HRPcEcoR1 |

CGGAATTCATGCTACTAGTAAATCAGTCAC |

| Rv-HRPcEcoR1 |

CGGAATTCTCATCGCCGACGTCGTCTC |

| Fw-Ac15

|

CCAGTACAGTTATTCGGTTTGAAG |

| Rv-Ac15

|

GCTCTTTACAAGATGGATTCCTCC |

| Fw-Ac16 |

CGTTTCCAGCGATCAACTAC |

| Rv-Ac16

|

TCTGTGCGTTGTCTTCTTCTGT |

| Fw-Ac129

|

GTCTTCATTTGCGCGTTGCA |

| Fw-Ac131

|

GATTCAGGAGAGTCTCAACG |

| Rv-Ac131

|

GAATATTTGTCGACGCCCTC |

| Fw-Ac136

|

GCACATGGCTCATAACTAAAC |

| Rev-Ac136

|

CCGGCATCCTCAAATGCATA |

| Fw-Ac138

|

AGTATGCTGGAAGGCGCTTT |

| Rv-Ac138

|

CGGTTTTAACAGCCGTCGAT |

| Fw-Ac148

|

GGTCTGAAATGCCCTGAAATAC |

| Rv-Ac150

|

AGTTTTGGTTAGCGGTACATCC |

| Fw-ie1 |

ACCATCGCCCAGTTCTGCTTATC |

| Rv-ie1 |

GCTTCCGTTTAGTTCCAGTTGCC |

Table 2.

Summary of sgRNA characteristics.

Table 2.

Summary of sgRNA characteristics.

| Target ORF |

sgRNA sequence 5´-3´ |

Localization |

Strand |

GC (%) |

Efficiency |

|

Ac-15 (egt) |

GTTTGGTCACTTGTACGATC |

444 |

+ |

45 |

0.52 |

|

Ac-16 (ODV-26) |

GTTCACAGAACCGACCGGCA |

71 |

- |

60 |

0.61 |

|

Ac-129 (p24) |

GTCATCATTACCAATTCGGA |

73 |

+ |

40 |

0.64 |

|

Ac-131 (pp34) |

AAATGTGCTCAACAACTGGT |

239 |

- |

40 |

0.66 |

|

Ac-136 (p26) |

AATAGAGCAAGTCGACAATG |

51 |

+ |

50 |

0.72 |

|

Ac-138 (p74) |

AACTGGCTTTCAGCAAGCGC |

191 |

- |

55 |

0.62 |

|

Ac148(ODV-E56) |

CTTTTAACAAGCACTCCCGC |

79 |

- |

50 |

0.62 |

| Ac-150 |

GACGATGACGAATCAGACGA |

91 |

+ |

50 |

0.68 |

Table 3.

Summary of the effects of genome editing on eGFP and HRPc expression

Table 3.

Summary of the effects of genome editing on eGFP and HRPc expression

| Edited virus |

Host |

Impact on eGFP level xpression (%) relative to parental virus |

Impact on HRPc level expression (%) relative to parental virus |

|

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac[15]-Ac[16]

|

Sf9 at MOI 0.5 |

NS |

NS |

| Sf9 at MOI 5 |

↑180 |

↑27 |

| S. frugiperda |

↑84 |

↑211 |

| R. nu |

↑87 |

↑54 |

|

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac[129]-Ac[131]

|

Sf9 at MOI 0.5 |

↑130 |

↑74 |

| Sf9 at MOI 5 |

↑150 |

↑46 |

| S. frugiperda |

↑133 |

↑190 |

| R. nu |

↑150 |

↑51 |

|

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac[136]-Ac[138]

|

Sf9 at MOI 0.5 |

NS |

NS |

| Sf9 at MOI 5 |

↑39 |

↑79 |

| S. frugiperda |

↓60 |

↓45 |

| R. nu |

↓30 |

↓54 |

|

Ac-eGFP/HRPc∆Ac[148]-Ac[150]

|

Sf9 at MOI 0.5 |

ND |

↓40 |

| Sf9 at MOI 5 |

↓28 |

↓30 |

| S. frugiperda |

↓48 |

↓53 |

| R. nu |

↓58 |

↓54 |