Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

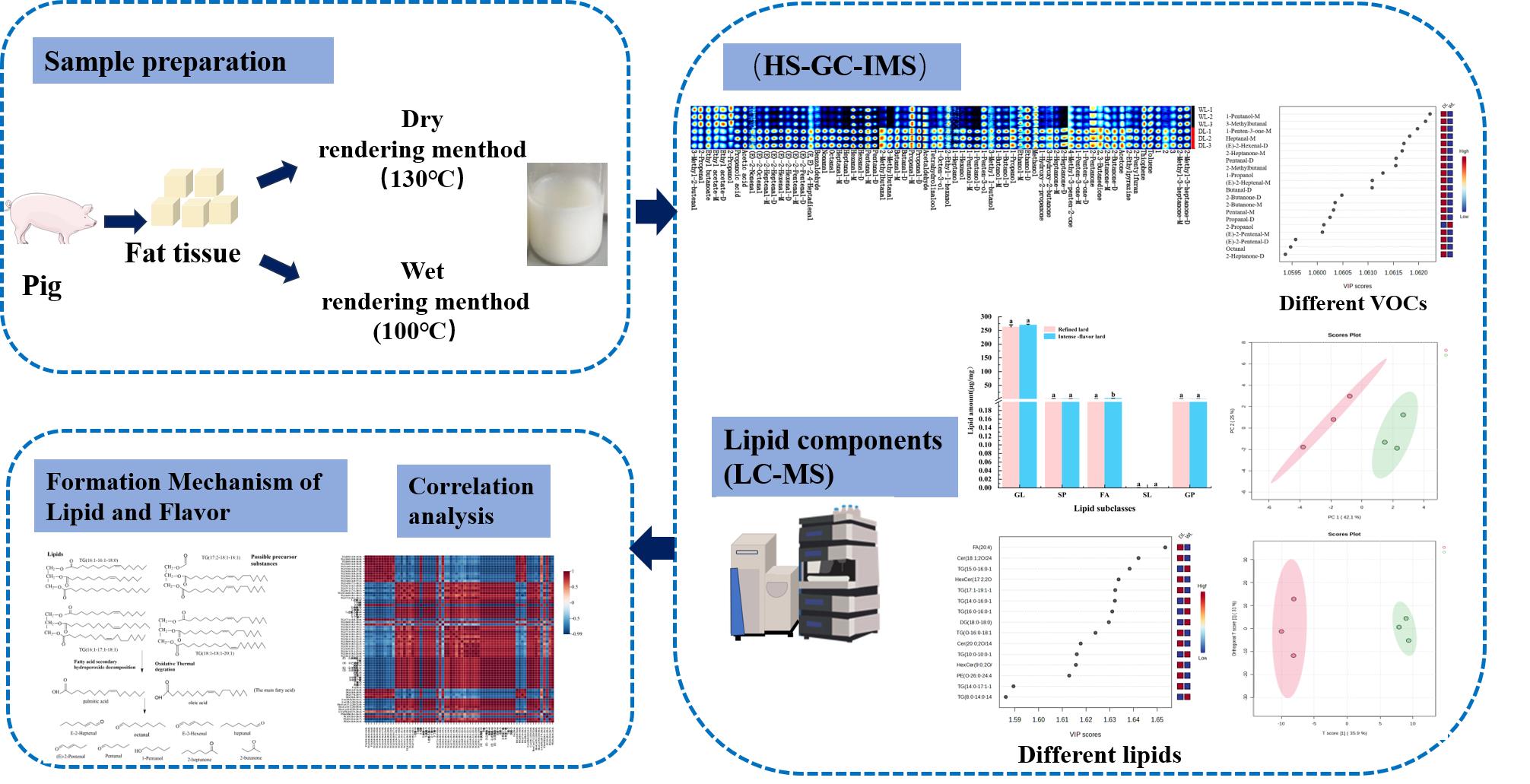

Abstract

Keywords:

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

2.2. Preparation of lards

2.3. Determination of peroxide value (PV), acid value (AV)) and Water Content

2.4. HS-GC-IMS analysis of lard

2.5. Sensory evaluation method of lard

2.6. Electronic nose evaluation method for lard

2.7. Determination of lipid composition for lard

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Critical quality parameters of lard: Acid value, peroxide value and water content

3.2. HS-GC-IMS analysis of lard

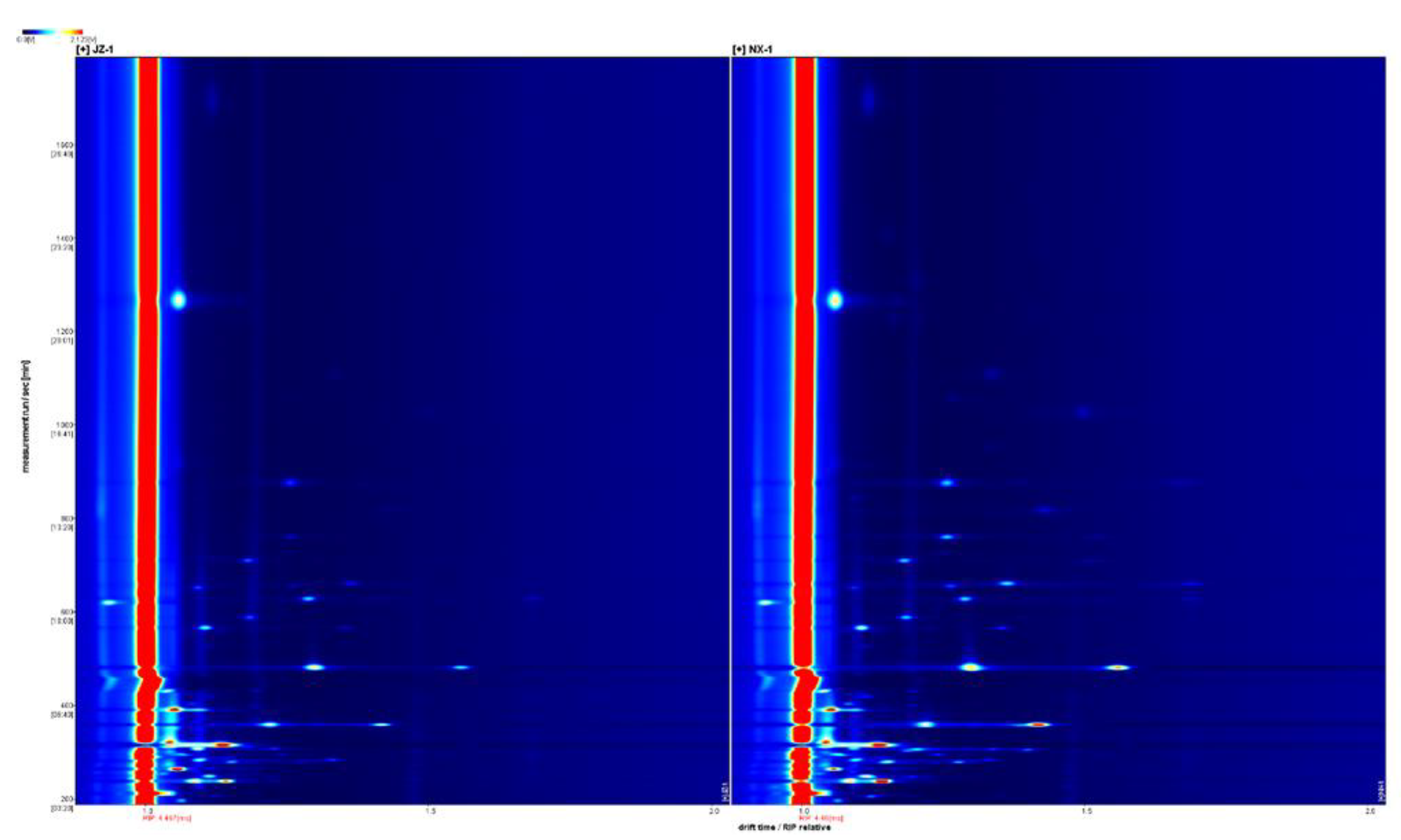

3.2.1. HS-GC-IMS spectrum analysis

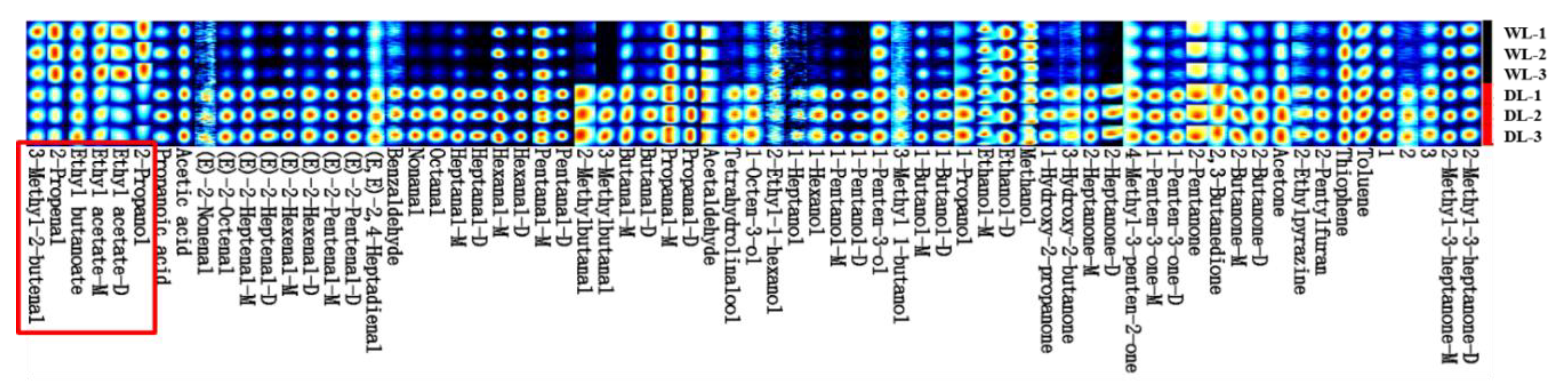

3.2.2. HS-GC-IMS fingerprint spectrum

3.2.3. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of HS-GC-IMS

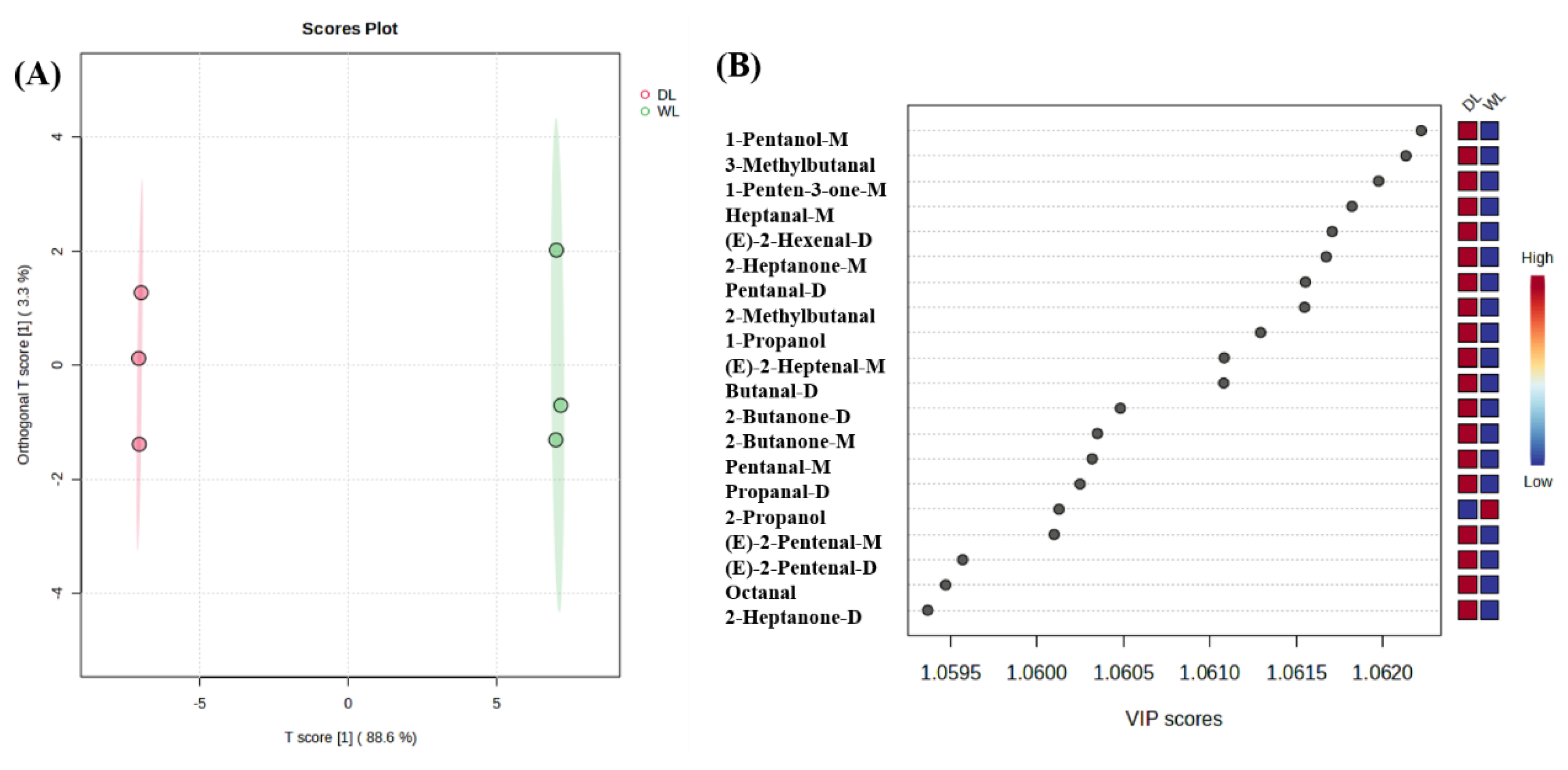

3.2.4. PCA and OPLS-DA analysis of HS-GC-IMS

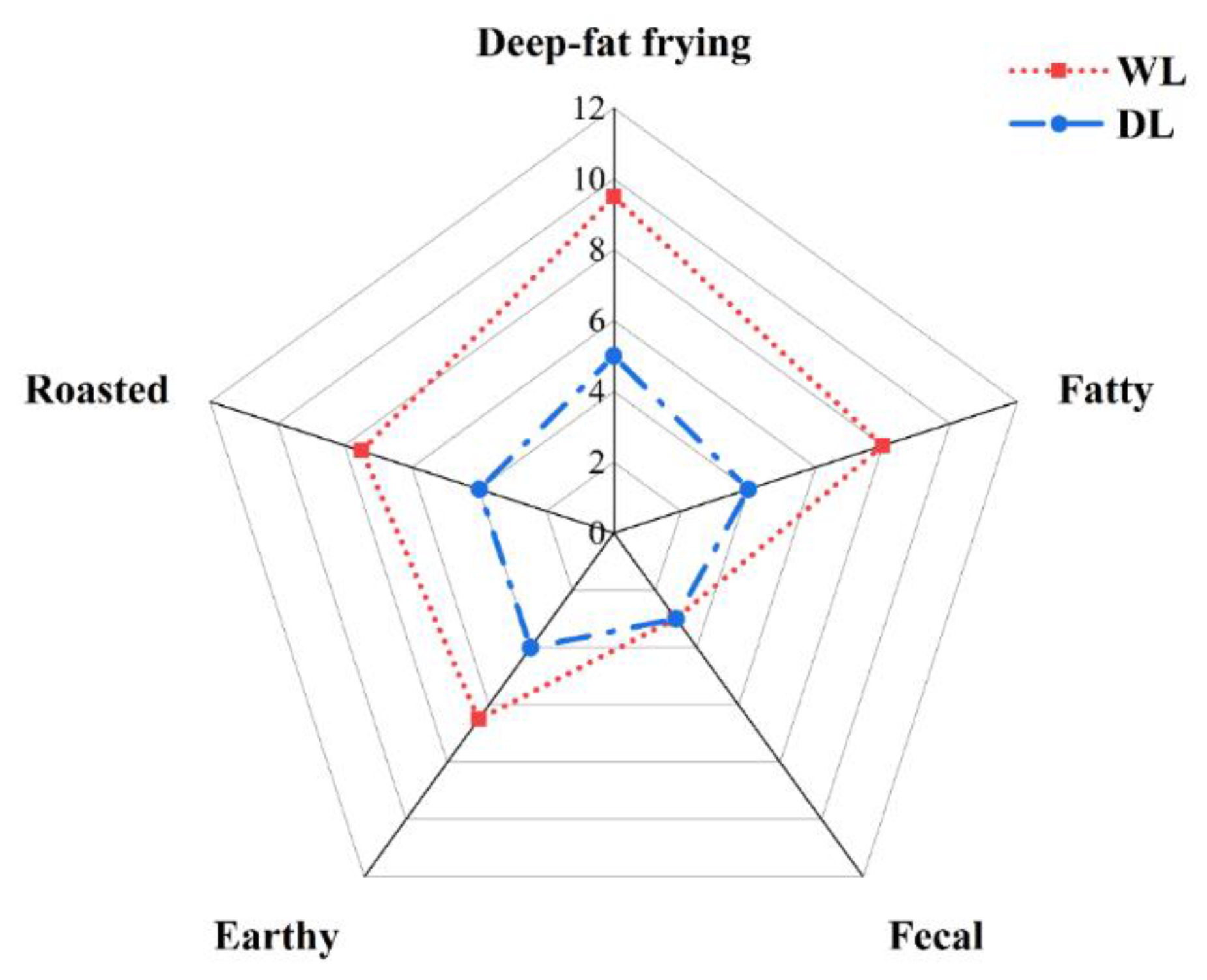

3.3. Sensory analysis of lard

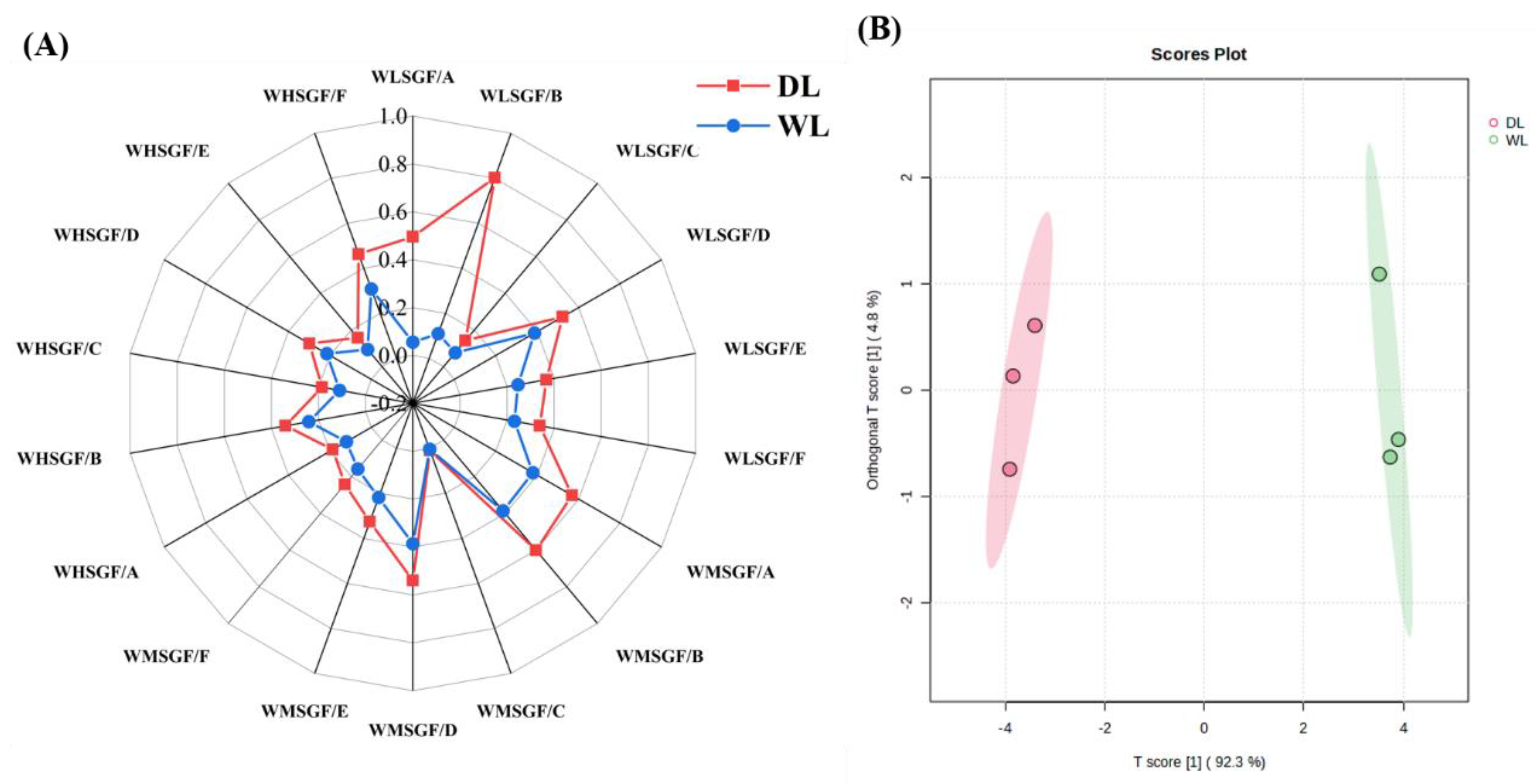

3.4. Analysis of Electronic Nose Results

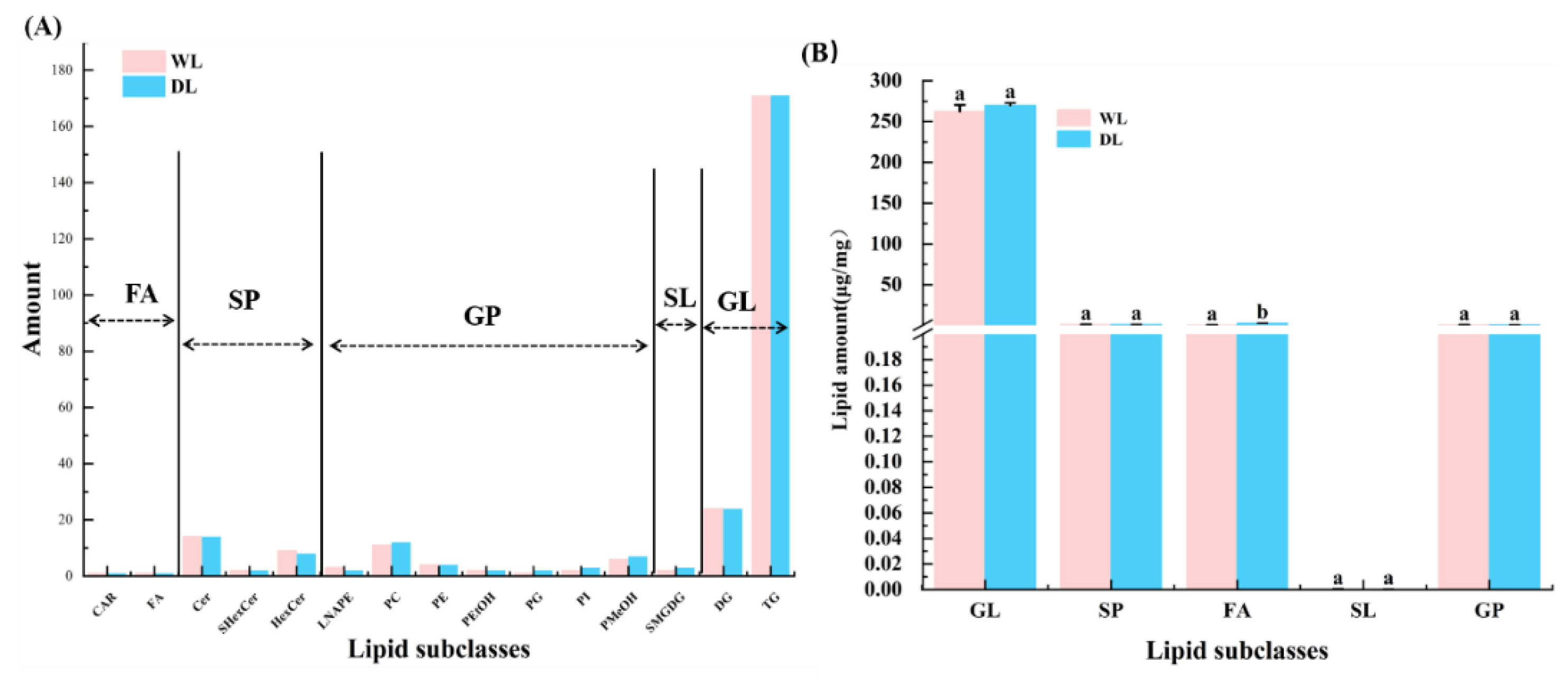

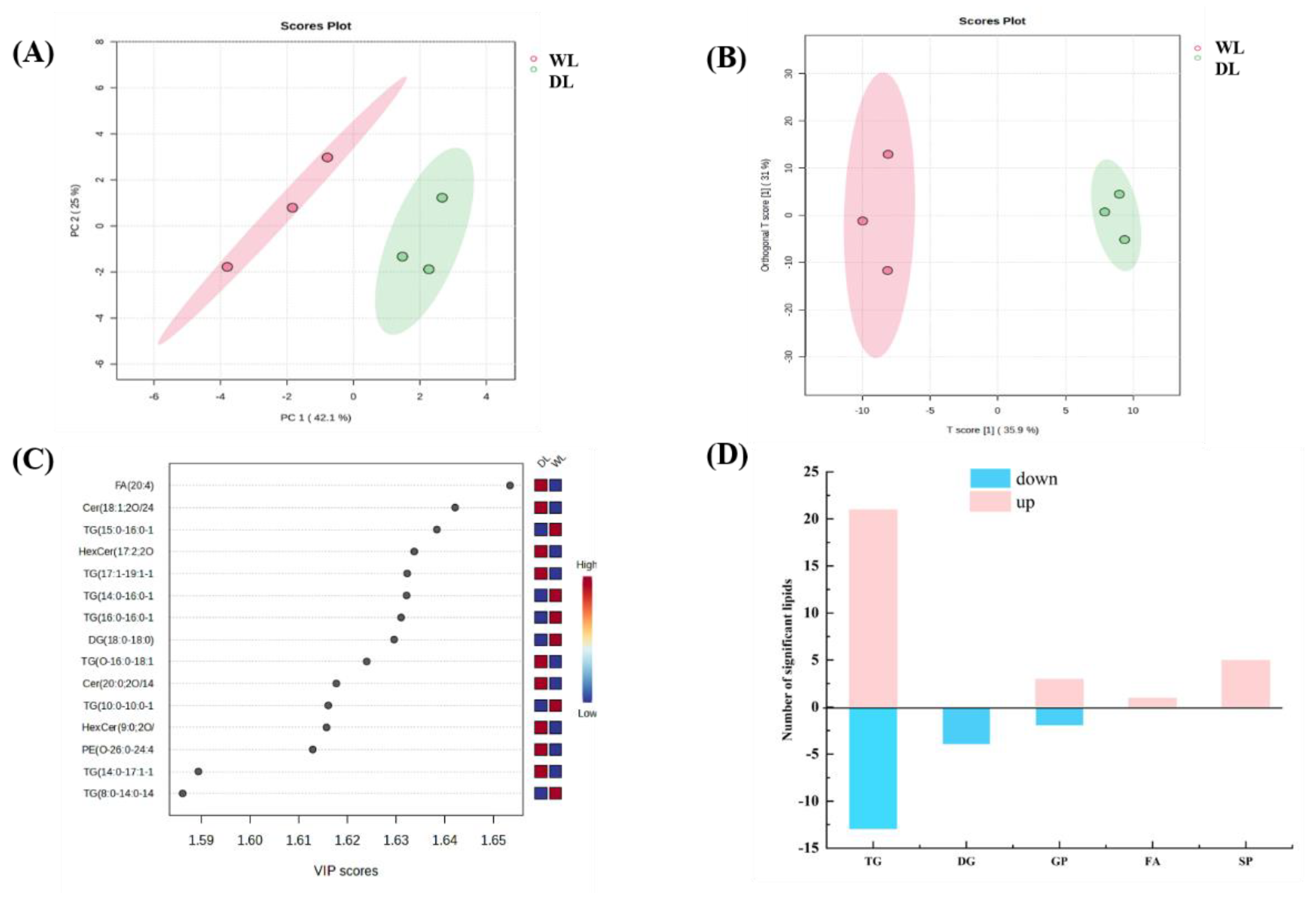

3.5. Lipid Composition Analysis

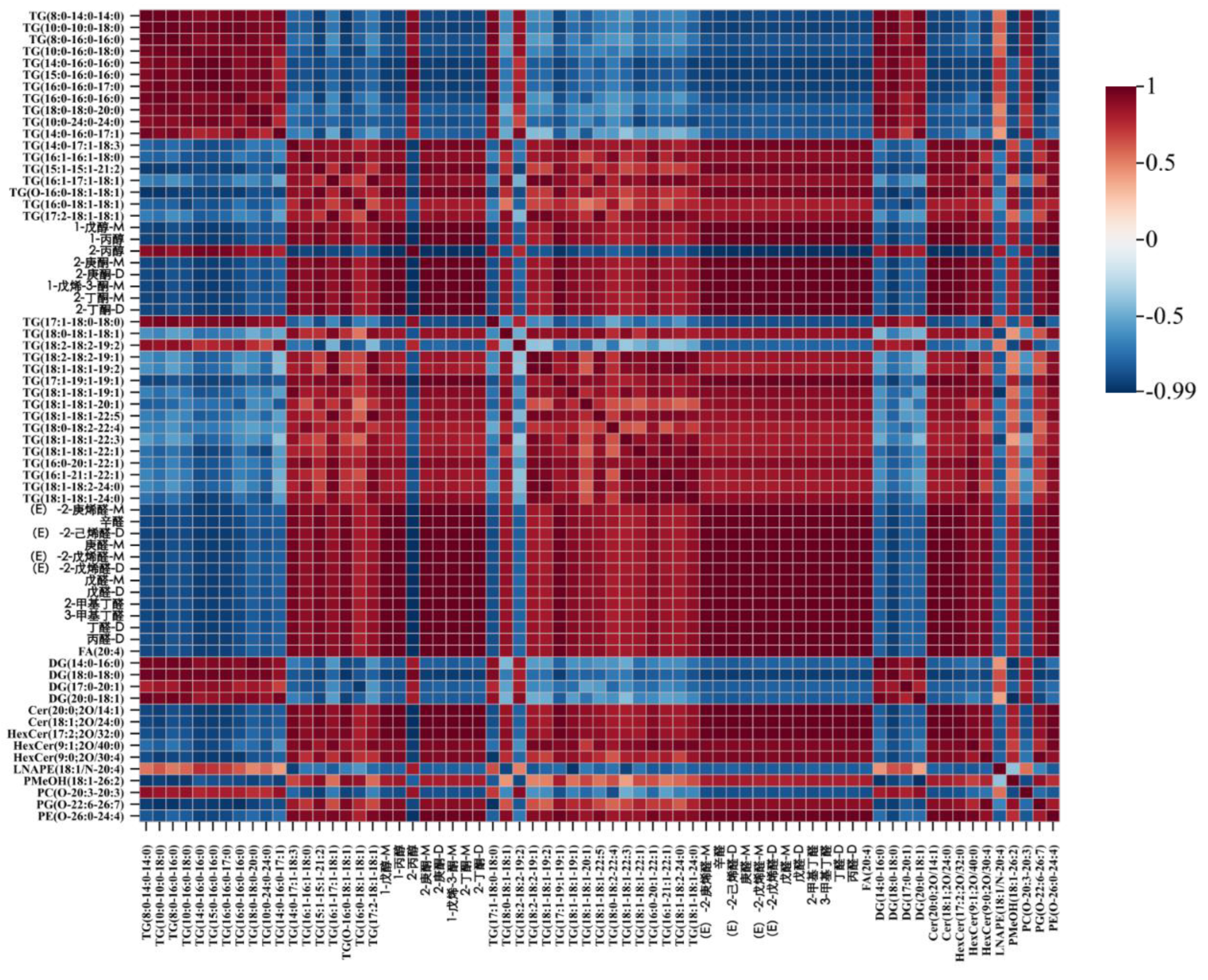

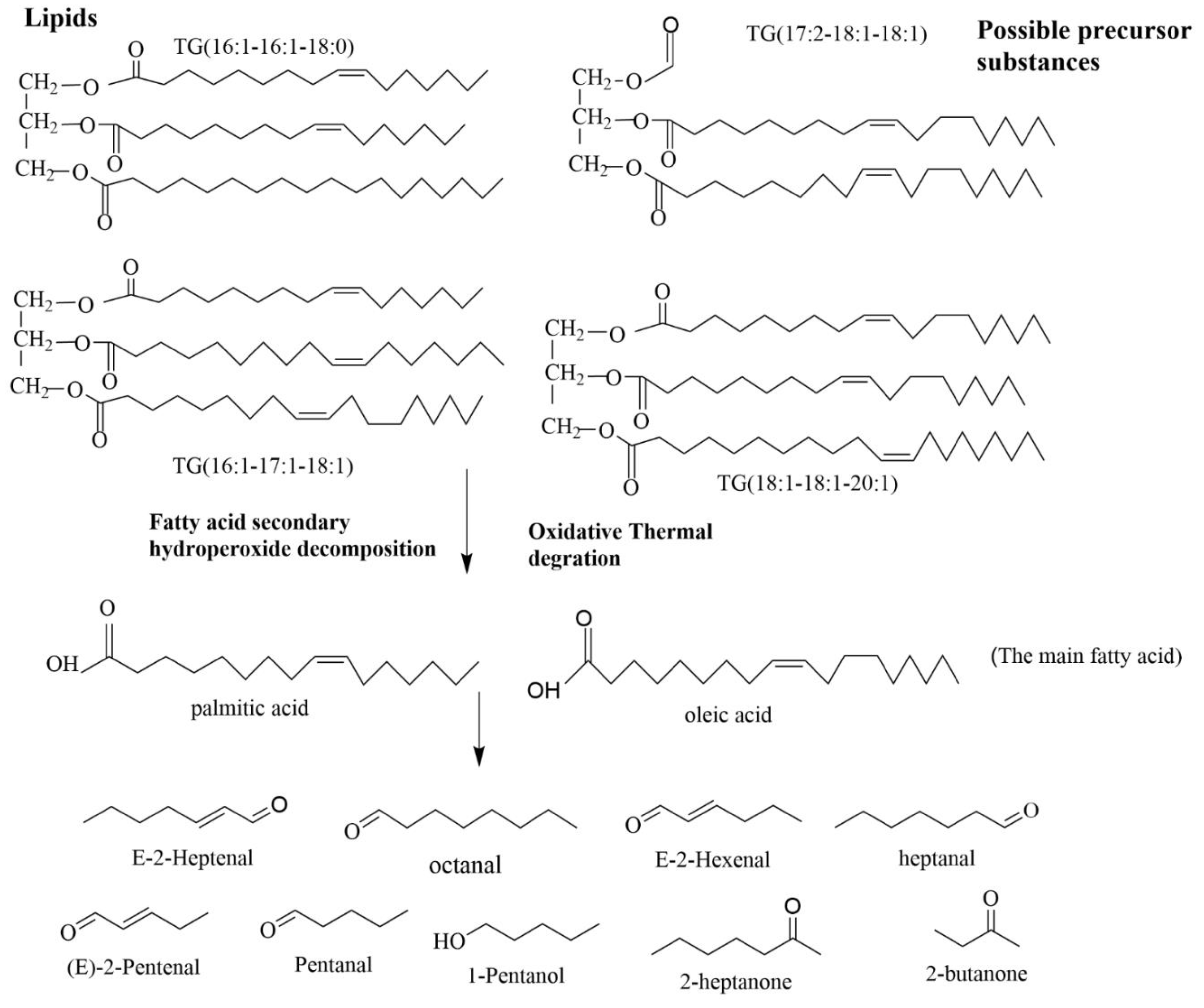

3.6. Correlation analysis of VOCs and lipids

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L. Beef tallow/lard blends in O/W emulsions: Characterization of fat crystals, partial coalescence, rheology, and aeration performance [J]. Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, L. Z.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Xu, X. Physical characterization of lard partial acylglycerols and their effects on melting and crystallization properties of blends with rapeseed oil [J]. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 5020–5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marikkar, J. M. N.; Yanty, N. A. M. Effect of Chemical and Enzymatic Modifications on the Identity Characteristics of Lard: A Review [J]. Int. J. Food Prop. 2013, 17, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, N. I. M.; Gani, S. S. A.; Sahri, M. M.; Zaidan, U. H.; Halmi, M. I. E. Comparative study on physical properties of cookies and dough made with palm-based shortening and lard [J]. Journal of Critical Reviews 2020, 1374–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Yanty, N. A. M.; Marikkar, J. M. M.; Miskandar, M. S. Comparing the thermo-physical characteristics of lard and selected plant fats [J]. Grasas Y. Aceites. 2012, 63, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ault, W. C. Technology of edible animal fats [J]. Prog. Chem. Fats Other Lipds. 1958, (5), 263-284. [CrossRef].

- Cravotto, G.; Boffa, L.; Mantegna, S.; Perego, P.; Avogadro, M.; Cintas, P. Improved extraction of vegetable oils under high-intensity ultrasound and/or microwaves [J]. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008, 15, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. L.; Jiang, J.; Li, J. W.; Qiu, M. B.; Lin, C. Z.; Shi, X. H.; Cao, P. R.; Liu, Y. F. High quality lard with low cholesterol content produced by aqueous enzymatic extraction and β-cyclodextrin treatment [J]. Eur J Lipid Sci Tech. 2015, 118, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Liu, J. GC-O-MS technique and its applications in food flavor analysis [J]. Food Res. Int. 2018, 114, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Du, W.; Jin, L.; Ren, P.; Ren, f.; Xie, J. Comparative analysis of aroma compounds in Chinese traditional dry-rendered fat by HS/GC-IMS, SPME/GC-MS, and SPME/GC-O [J]. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 107, 104378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Bai, L.; Feng, X.; Chen, Y. P.; Zhang, D.; Yao, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y. Characterization of Jinhua ham aroma profiles in specific to aging time by gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) [J]. Meat Sci. 2020, 168, 108178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, W.; Li, X.; Ouyang, L.; Zhu, S.; Hu, S.; Zhou, J. Characterization of key aroma compounds in Rice flavor baijiu from different rice raw materials by gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry and gas chromatography-olfactometry-quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry [J]. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Gagaoua, M.; Barba, F. J.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J. M. A Comprehensive Review on Lipid Oxidation in Meat and Meat Products [J]. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland). 2019, 8, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottram, D. S. Flavour formation in meat and meat a review [J]. Food Chem. 1998, 62, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Lei, S.; Wu, P.; Fan, G.; Xu, X.; Pan, S. Effects of lard on the formation of volatiles from the Maillard reaction of cysteine with xylose [J]. J Sci Food Agric. 2011, 91, 2241–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonietta Paleari, M.; Maria Moretti, V.; Bersani, C.; Beretta, G.; Mentasti, T. Characterisation of a lard cured with spices and aromatic herbs [J]. Meat Sci. 2004, 67, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ye, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, D. Pork phospholipids influence the generation of lipid-derived lard odorants in dry rendering process [J]. LWT. 2021, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, K.; Zhu, J.; Koga, M. Analysis of cooking oil fumes by ultraviolet spectrometry and gas chromatography−mass spectrometry [J]. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4790–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhao, M.; Bindler, F.; Marchioni, E. Comparison of the volatiles formed by oxidation of phosphatidylcholine to triglyceride in model systems [J]. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8295–8301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kong, Q.; Sun, Z.; Liu, J. Freshness analysis based on lipidomics for farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) stored at different times [J]. Food Chem. 2022, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xia, Q.; Qian, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Liu, J.; Lin, L. Effects of Three Extraction Methods on Avocado Oil Lipid Compounds Analyzed via UPLC-TOF-MS/MS with OPLS-DA [J]. Foods. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B. F.; Wei, F.; Xu, S. L.; Xie, Y.; Lv, X.; Chen, H.; Huang, F. H. Mass spectrometry-based lipidomics as a powerful platform in foodomics research [J]. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 107, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ren, Y.; Shi, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhao, L.; Dong, M.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C. Comprehensive foodomics analysis reveals key lipids affect aroma generation in beef [J]. Food Chem. 2024, 461, 140954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Ma, Q.; Xing, J.; Li, P.; Gao, P.; Hamid, N.; Wang, Z.; Wang, P.; Gong, H. Exploring the formation and retention of aroma compounds in ready-to-eat roasted pork from four thermal methods: A lipidomics and heat transfer analysis [J]. Food Chem. 2024, 431, 137100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, K.; Chen, X.; Yang, B.; Kan, J. Thermostability and kinetics analysis of oil color, carotenoids and capsaicinoids in hotpot oil models (butter, rapeseed oil, and their blends) [J]. LWT. 2021, 152, 112216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhou, D.-Y.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Yin, F.-W.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Li, D.-Y.; Shahidi, F. Hydrolysis and oxidation of lipids in mussel Mytilus edulis during cold storage [J]. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariutti, L. R. B.; Bragagnolo, N. Influence of salt on lipid oxidation in meat and seafood products: A review [J]. Food Res. Int. 2017, 94, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.-t.; Ma, X.-t.; Li, S.-j.; Wang, X.-d.; Liu, H.-m.; Shi, R. Comparison of key aroma-active compounds between roasted and cold-pressed sesame oils [J]. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Wang, Q.; Xia, T.; Wang, L.; Song, H.; Yang, L. Effect of smelting temperatures on the odor compounds of beef tallow through instrumental and sensory techniques [J]. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Ren, G.; Faiza, M.; Li, D.; Cui, J.; Zhang, K.; Yao, X.; Zhao, M. Comparison of conventional and green extraction methods on oil yield, physicochemical properties, and lipid compositions of pomegranate seed oil [J]. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 114, 104747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Sun, B. Recent progress in food flavor analysis using gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry (GC–IMS) [J]. Food Chem. 2020, 315, 126158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zhao, M.; Zhen, D.; Tan, J.; Wang, T.; Xie, J. Key aroma compounds in Chinese fried food of youtiao. [J]. Flavour Frag J. 2020, 35, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yuan, B.; Yu, P.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, J. Flavor characteristics of peanut butter pretreated by radio frequency heating, explosion puffing, microwave, and oven heating [J]. Food Chem. 2022, 394, 133487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinert, L.; Andersen, L. T.; Bredie, W. L. P.; Bjergegaard, C.; Aaslyng, M. D. Chemical and sensory characterisation of pan-fried pork flavour: Interactions between raw meat quality, ageing and frying temperature [J]. Meat Sci. 2007, 75, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Tang, Q.; Fan, L.; Xu, X.; Song, Z.; Hayat, K.; Feng, T.; Wang, Y. Identification of pork flavour precursors from enzyme-treated lard using Maillard model system assessed by GC-MS and partial least squares regression [J]. Meat Sci. 2017, 124, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Ma, S.; Wu, H.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M. Flavor profile analysis of grilled lamb seasoned with classic salt, chili pepper, and cumin (Cuminum cyminum) through HS-SPME-GC-MS, HS-GC-IMS, E-nose techniques, and sensory evaluation on Sonit sheep [J]. Food Chem. 2024, 454, 139514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Tian, Z.; Zheng, X.; Tang, X.; Li, W.; Huang, X. Characterization of flavour components and identification of lipid flavour precursors in different cuts of pork by phospholipidomics [J]. Food Chem. 2024, 458, 139422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Kong, X. F.; Hu, C. J.; Zhou, B.; Wang, C. T.; Shen, Q. W. Fatty acid content, flavor compounds, and sensory quality of pork loin as affected by dietary supplementation with L-arginine and glutamic acid [J]. J Food Sci. 2019, 84, 3445–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S. S.; Zhan, P.; Tian, H.; Wang, P.; Ma, X.; Li, K. Effects of thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) addition on the volatile compounds of mutton broth during boiling [J]. Food Sci Hum Well. 2022, 11, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.-R.; Wei, C.-K.; Wang, M.-S.; Ju, N.; Fan, M. Characterization of the key flavor compounds in cream cheese by GC-MS, GC-IMS, sensory analysis and multivariable statistics [J]. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 8, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Onandi, N.; Rivas-Cañedo, A.; Ávila, M.; Garde, S.; Nuñez, M.; Picon, A. Influence of physicochemical characteristics and high pressure processing on the volatile fraction of Iberian dry-cured ham [J]. Meat Sci. 2017, 131, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’quinn, T. G.; Legako, J. F.; Woerner, D. R.; Kerth, C. R.; Nair, M. N.; Brooks, J. C.; Lancaster, J. M.; Miller, R. K. A current review of U.S. beef flavor II: Managing beef flavor [J]. Meat Sci. 2024, 209, 109403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Dong, J.; He, X.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Yi, Y.; Wang, S. Impact of Heating Temperature and Fatty Acid Type on the Formation of Lipid Oxidation Products During Thermal Processing [J]. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 913297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, H.; Turner, C.; Spooner, A.; Chambers, M. Methodological variation in headspace analysis of liquid samples using electronic nose [J]. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2009, 139, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, M. Y.; Mai, Y. H.; Guo, H.; Wadood, S. A.; Raza, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Y.; Li, H. B.; Gan, R. Y. The chemical, sensory, and volatile characteristics of instant sweet tea (Lithocarpus litseifolius [Hance] Chun) using electronic nose and GC-MS-based metabolomics analysis [J]. LWT. 2022, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Zeng, Q.; He, X.; Xu, K.; He, J. Optimizing conditions of electronic nose for rapid detection of flavor substances in Ningxiang Pork [J]. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti, S.; Grassi, S.; Ubaldi, P. G.; Pianezzola, A.; Benedetti, S. E-nose based control charts for fish freshness evaluation [J]. Food Res. Int. 2025, 209, 116313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, C.; Leppert, J.; Santiuste, A. C.; Pfeiffer, A.; Boeker, P.; Wust, M. Comparative Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis (cAEDA) of Fat from Tainted Boars, Castrated Male Pigs, and Female Pigs [J]. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 2403–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, K.; Yang, H.; Yue, K.; Liu, R.; Bi, Y.; Ma, C. Characterization of lard from different adipose tissues: Physicochemical properties, thermodynamics characteristics and crystallization behaviors [J]. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; Zhu, M.; Qian, X.; Shi, L.; Huang, H.; Xiong, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. Effect of fatty acids on the flavor formation of fish sauce [J]. LWT. 2020, 134, 110259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | WL | DL |

|---|---|---|

| PV (g/100g) | 0.066±0.001 | 0.083±0.003* |

| AV (mg KOH/g) | 0.675±0.010 | 0.895±0.033* |

| Water content (%) | 0.12±0.0009 | 0.11 ±0.04 |

| WL | DL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Compound | Formula | MW | RI | Rt (s) | Concentration (μg/100g Lard) | |

| 1 | (E)-2-Nonenal | C9H16O | 140.2 | 1577 | 1479.388 | 13.38±1.89 | 17.81±1.28* |

| 2 | Benzaldehyde | C7H6O | 106.1 | 1551.1 | 1398.721 | 11.06±0.44 | 16.11±0.28*** |

| 3 | (E,E)-2,4-Heptadienal | C7H10O | 110.2 | 1520.2 | 1308.643 | 11.07±0.46 | 13.04±0.27** |

| 4 | (E)-2-Octenal | C8H14O | 126.2 | 1442.8 | 1106.975 | 8.94±0.49 | 20.31±0.31*** |

| 5 | Nonanal | C9H18O | 142.2 | 1407.6 | 1025.979 | 9.77±0.71 | 25.4±0.58*** |

| 6 | (E)-2-Heptenal-M | C7H12O | 112.2 | 1334.6 | 876.241 | 34.64±0.75 | 63.05±0.47*** |

| 7 | (E)-2-Heptenal-D | C7H12O | 112.2 | 1334.3 | 875.567 | 3.83±0.43 | 9.06±0.44*** |

| 8 | Octanal | C8H16O | 128.2 | 1302.5 | 817.541 | 4.43±0.35 | 17.39±0.33*** |

| 9 | (E)-2-Hexenal-M | C6H10O | 98.1 | 1234 | 710.356 | 27.87±0.69 | 40.71±0.45*** |

| 10 | (E)-2-Hexenal-D | C6H10O | 98.1 | 1234 | 710.356 | 2.02±0.05 | 4.68±0.06*** |

| 11 | Heptanal-M | C7H14O | 114.2 | 1198.8 | 661.26 | 17.6±0.41 | 52.88±0.41*** |

| 12 | Heptanal-D | C7H14O | 114.2 | 1199.2 | 661.8 | 1.84±0.25 | 11.96±0.09*** |

| 13 | 3-Methyl-2-butenal | C5H8O | 84.1 | 1192.8 | 653.168 | 13.38±0.89* | 11.66±0.51 |

| 14 | (E)-2-Pentenal-M | C5H8O | 84.1 | 1150.6 | 565.767 | 50.21±0.62 | 65.14±0.34*** |

| 15 | (E)-2-Pentenal-D | C5H8O | 84.1 | 1151.4 | 567.386 | 7.9±0.28 | 14.75±0.15*** |

| 16 | Hexanal-M | C6H12O | 100.2 | 1103.5 | 481.604 | 122.05±7.19 | 189.77±2.18*** |

| 17 | Hexanal-D | C6H12O | 100.2 | 1103.9 | 482.143 | 41.26±8.98 | 122.53±8.9*** |

| 18 | Pentanal-M | C5H10O | 86.1 | 1003.6 | 359.674 | 76.66±0.72 | 100.04±1.06*** |

| 19 | Pentanal-D | C5H10O | 86.1 | 1003.4 | 359.515 | 55.24±1.36 | 141.32±2.23*** |

| 20 | 2-Methylbutanal | C5H10O | 86.1 | 932 | 306.038 | 5.59±0.1 | 18.21±0.65*** |

| 21 | 3-Methylbutanal | C5H10O | 86.1 | 931.4 | 305.624 | 0.69±0.04 | 16.84±0.66*** |

| 22 | Butanal-M | C4H8O | 72.1 | 890.6 | 279.539 | 22.41±0.71 | 39.11±1.3*** |

| 23 | Butanal-D | C4H8O | 72.1 | 890.9 | 279.746 | 7.74±0.22 | 20.79±0.66*** |

| 24 | 2-Propenal | C3H4O | 56.1 | 864.4 | 264.013 | 89.84±0.48*** | 61.07±1.54 |

| 25 | Propanal-M | C3H6O | 58.1 | 818.3 | 238.756 | 87.07±1.02 | 96.3±0.76*** |

| 26 | Propanal-D | C3H6O | 58.1 | 818.7 | 238.963 | 96.24±2.26 | 165.59±2.68*** |

| 27 | Acetaldehyde | C2H4O | 44.1 | 764 | 212.05 | 102.6±2.26 | 117.75±3.65** |

| Aldehydes | Subtotal | 925.33±9.09 | 1473.25±11.8 | ||||

| 28 | Propanoic acid | C3H6O2 | 74.1 | 1637.6 | 1686.433 | 47.27±6.19 | 64.19±12.14 |

| 29 | Acetic acid | C2H4O2 | 60.1 | 1505.8 | 1268.309 | 265.5±18.64 | 297.41±19.08 |

| Acids | Subtotal | 312.77±22.07 | 361.59±11.96 | ||||

| 30 | 1-Octen-3-ol | C8H16O | 128.2 | 1490.3 | 1226.631 | 4.36±0.69 | 8.58±0.56** |

| 31 | 2-Ethyl-1-hexanol | C8H18O | 130.2 | 1544.8 | 1379.898 | 11.72±1.07 | 12.74±0.74 |

| 32 | 1-Heptanol | C7H16O | 116.2 | 1490.3 | 1226.631 | 8.35±0.69 | 11.77±0.16** |

| 33 | Tetrahydrolinalool | C10H22O | 158.3 | 1422.3 | 1059.045 | 3.04±0.7 | 7.18±0.31*** |

| 34 | 1-Hexanol | C6H14O | 102.2 | 1373.7 | 953.416 | 1.89±0.15 | 4.49±0.71** |

| 35 | 1-Pentanol-M | C5H12O | 88.1 | 1268.1 | 761.54 | 12.03±0.1 | 45.22±0.64*** |

| 36 | 1-Pentanol-D | C5H12O | 88.1 | 1267.8 | 761.07 | 1.54±0.15 | 5.65±0.14*** |

| 37 | 1-Penten-3-ol | C5H10O | 86.1 | 1177.4 | 620.258 | 35.47±0.86 | 40.35±0.34*** |

| 38 | 1-Butanol-M | C4H10O | 74.1 | 1162.3 | 588.966 | 26.82±0.62 | 37.64±0.51*** |

| 39 | 1-Butanol-D | C4H10O | 74.1 | 1162.5 | 589.506 | 1.39±0.12 | 2.46±0.28** |

| 40 | 1-Propanol | C3H8O | 60.1 | 1057.4 | 420.099 | 7.1±0.15 | 12.09±0.08*** |

| 41 | Ethanol-M | C2H6O | 46.1 | 947.4 | 316.489 | 181.66±0.48 | 185.24±1.61* |

| 42 | Ethanol-D | C2H6O | 46.1 | 946.7 | 315.983 | 228.47±3.59 | 232.53±0.76 |

| 43 | 2-Propanol | C3H8O | 60.1 | 934.5 | 307.694 | 36.14±1.04*** | 19.8±0.43 |

| 44 | 3-Methyl 1-butanol | C5H12O | 88.1 | 1222.7 | 694.258 | 1.54±0.37 | 1.66±0.04 |

| 45 | Methanol | CH4O | 32 | 908.4 | 290.658 | 84.37±3.97 | 84.17±6.82 |

| Alcohols | Subtotal | 645.86±3.73 | 711.57±7.95 | ||||

| 46 | 2-Ethylpyrazine | C6H8N2 | 108.1 | 1354.1 | 913.921 | 2.71±0.12 | 3.22±0.02** |

| 47 | 2-Pentylfuran | C9H14O | 138.2 | 1245.8 | 727.62 | 2.5±0.21 | 5.06±0.16*** |

| Heterocyclic compounds | Subtotal | 5.21±0.23 | 8.28±0.16 | ||||

| 48 | 1-Hydroxy-2-propanone | C3H6O2 | 74.1 | 1317.9 | 845.205 | 4.51±0.6 | 7.74±0.44** |

| 49 | 2-Heptanone-M | C7H14O | 114.2 | 1195.2 | 656.405 | 6.67±0.21 | 20.98±0.17*** |

| 50 | 2-Heptanone-D | C7H14O | 114.2 | 1195.2 | 656.405 | 0.82±0.06 | 2.76±0.14*** |

| 51 | 4-Methyl-3-penten-2-one | C6H10O | 98.1 | 1129.5 | 526.383 | 7.61±0.04 | 8.74±0.19*** |

| 52 | 1-Penten-3-one-M | C5H8O | 84.1 | 1044.7 | 404.993 | 9.67±0.09 | 13.83±0.07*** |

| 53 | 1-Penten-3-one-D | C5H8O | 84.1 | 1044.2 | 404.454 | 0.97±0.03 | 1.67±0.1*** |

| 54 | 2-Pentanone | C5H10O | 86.1 | 999.5 | 355.466 | 5.45±0.05 | 6.82±0.16*** |

| 55 | 2-Butanone-M | C4H8O | 72.1 | 915.3 | 295.066 | 24.27±0.27 | 31.45±0.22*** |

| 56 | 2-Butanone-D | C4H8O | 72.1 | 915.6 | 295.273 | 3.91±0.1 | 8.11±0.2*** |

| 57 | Acetone | C3H6O | 58.1 | 837 | 248.693 | 29.66±0.89 | 42.92±0.88*** |

| 58 | 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 1301.9 | 816.467 | 2.47±0.38 | 3.6±0.26* |

| 59 | 2,3-Butanedione | C4H6O2 | 86.1 | 994.1 | 350.47 | 1.38±0.05 | 1.95±0.19** |

| Ketones | Subtotal | 97.37±0.67 | 150.56±1.41 | ||||

| 60 | Ethyl butanoate | C6H12O2 | 116.2 | 1040.5 | 400.138 | 5.87±0.18* | 5.27±0.22 |

| 61 | Ethyl acetate-M | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 897.6 | 283.887 | 29.55±1.55** | 24.41±0.66 |

| 62 | Ethyl acetate-D | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 897.6 | 283.887 | 10.16±0.86** | 7.45±0.26 |

| Esters | Subtotal | 45.58±2.55 | 37.12±0.73 | ||||

| 63 | Thiophene | C4H4S | 84.1 | 1033 | 391.505 | 137.69±1.47 | 136.68±0.44 |

| 64 | Toluene | C7H8 | 92.1 | 1066.7 | 431.491 | 24.36±0.25 | 27.96±0.43*** |

| 65 | 1 | * | 0 | 1067.1 | 431.969 | 5.73±0.1 | 6.7±0.06*** |

| 66 | 2 | * | 0 | 1206.6 | 671.868 | 0.82±0.11 | 1.45±0.08** |

| 67 | 3 | * | 0 | 1170.4 | 605.673 | 1.95±0.07 | 2.89±0.08*** |

| Others | Subtotal | 170.55±1.56 | 175.69±0.92 | ||||

| Total | 2202.67±26.6 | 2918.06±22.35 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).