Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Chapter 1: Introduction

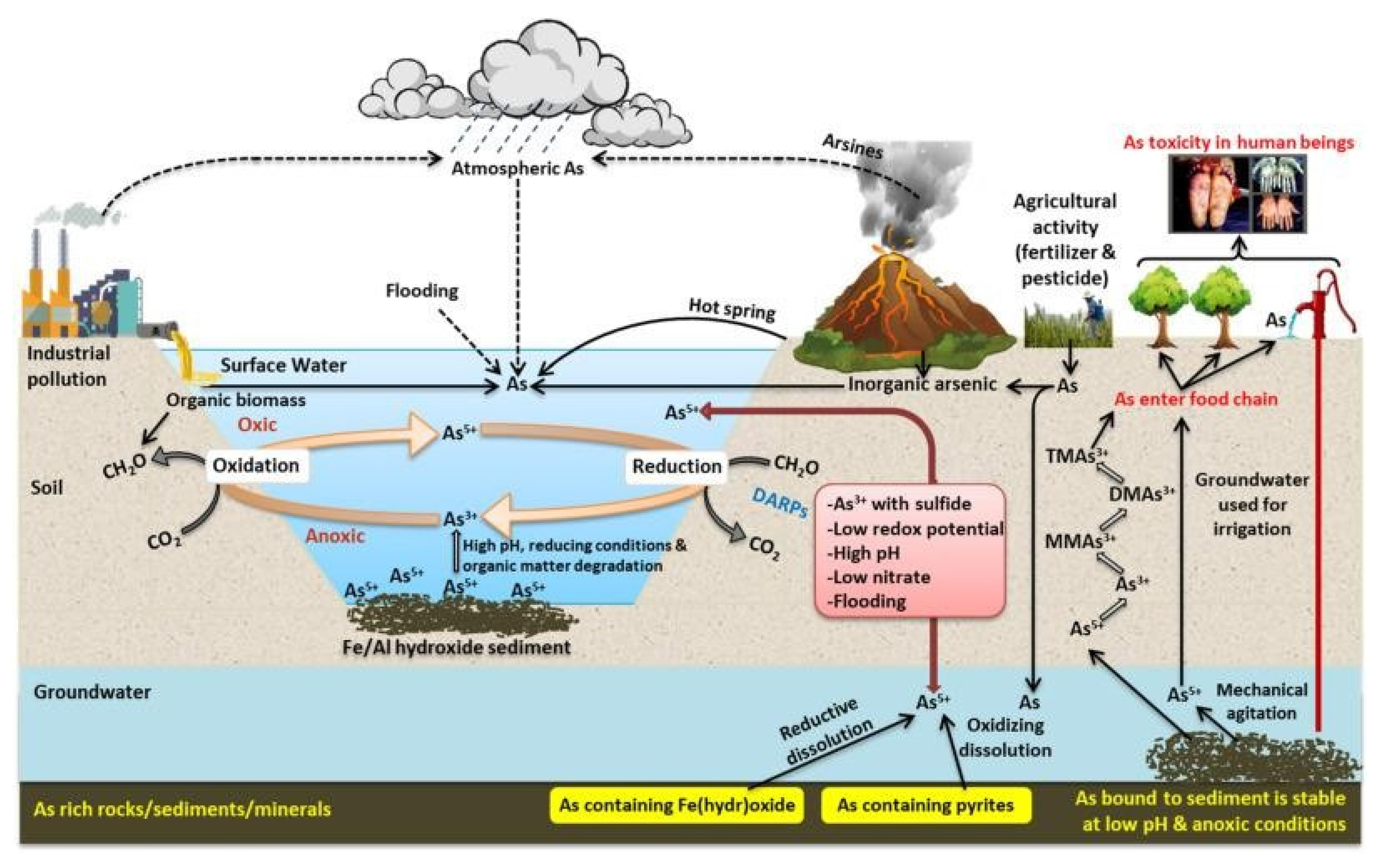

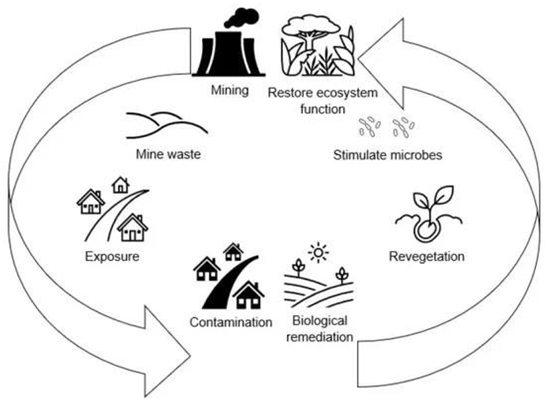

1.1. Background of the Research

1.2. Ex Situ Method

1.3. In-Situ

1.4. Phytoremediation and Its Importance

Chapter 2: Concepts and Mechanisms of Phytoremediation

2.1. Overview of Phytoremediation

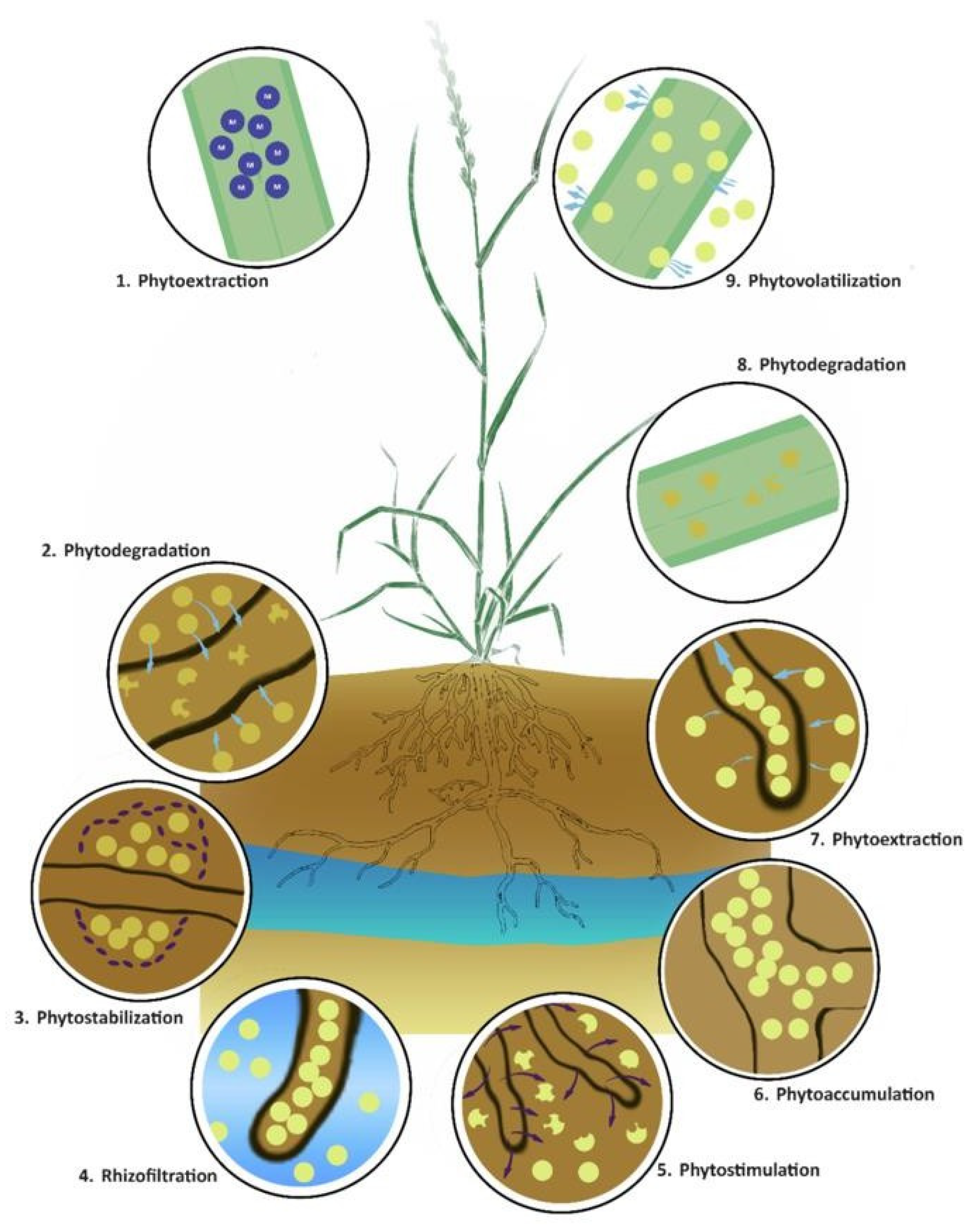

2.2. Restoration Mechanisms

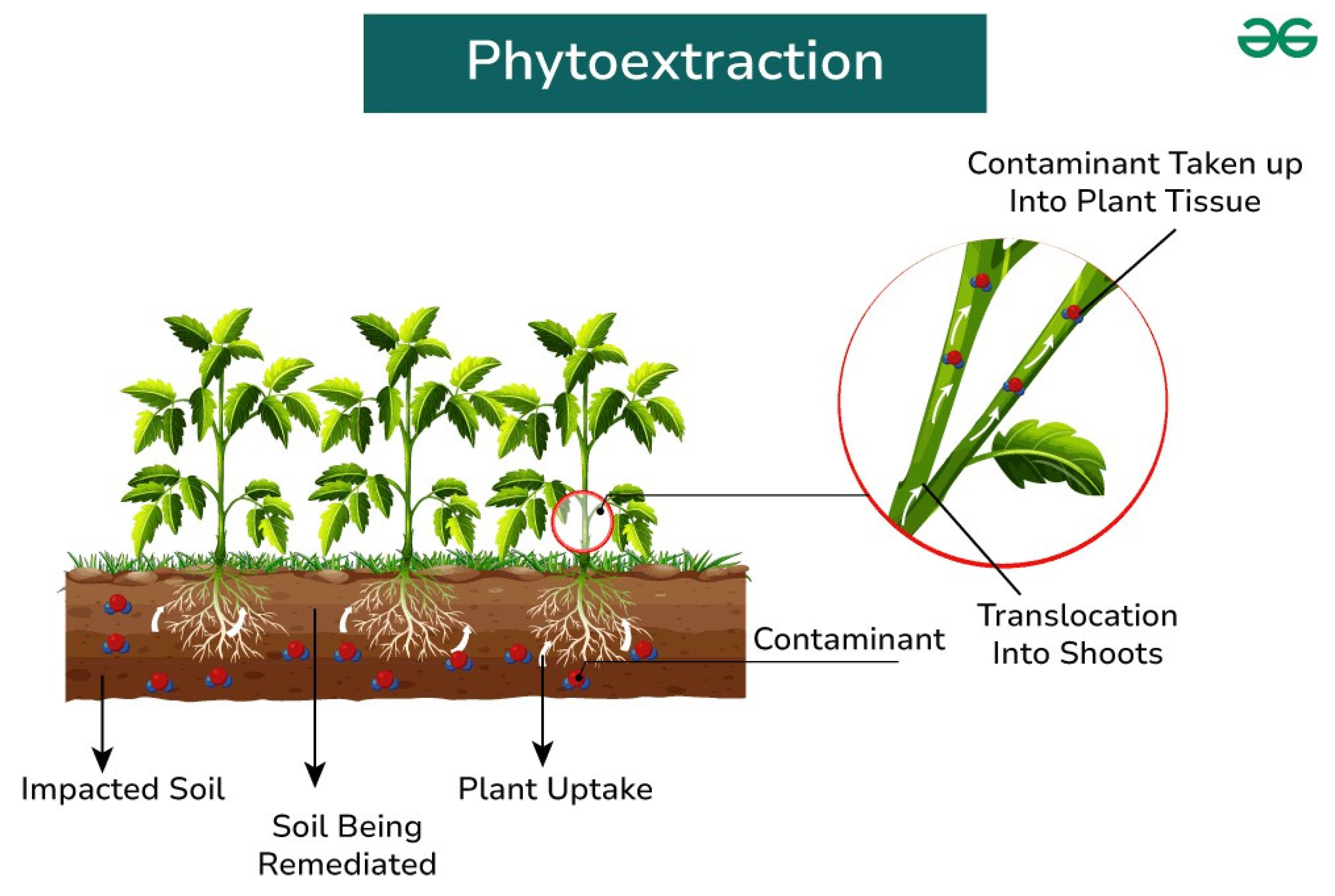

2.2.1. Phytoextraction

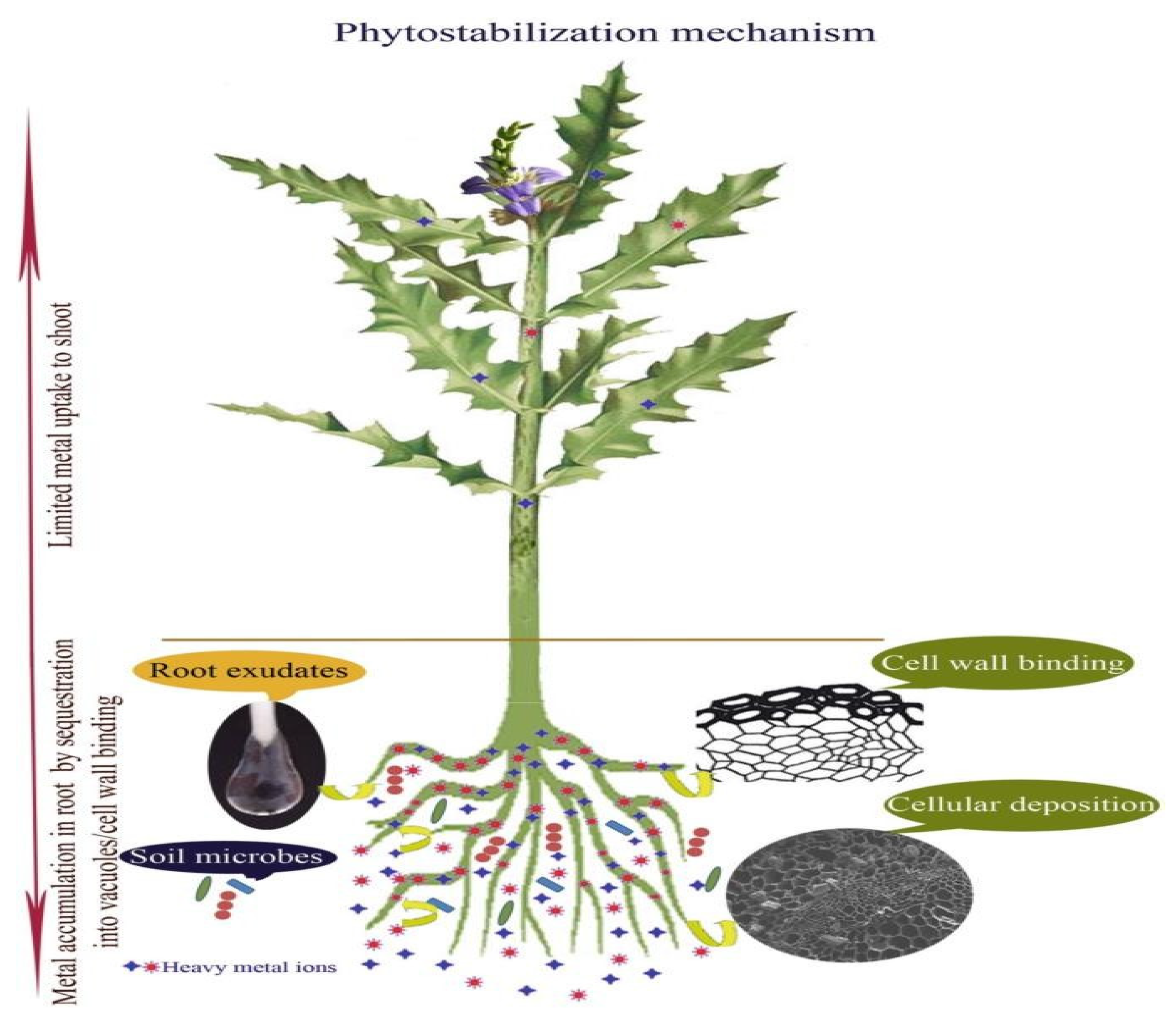

2.2.2. Phyto Stabilization

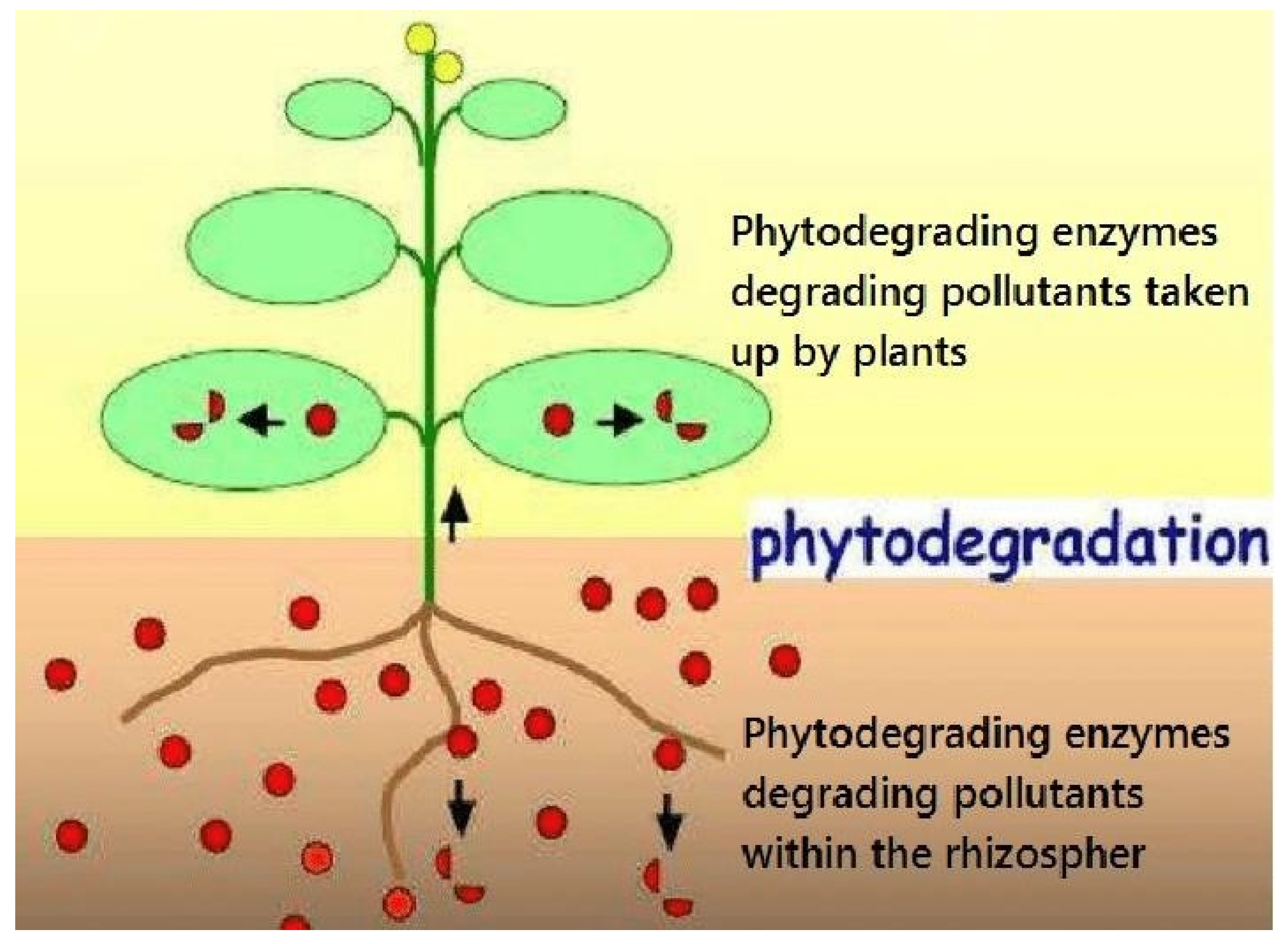

2.2.3. Phytodegradation

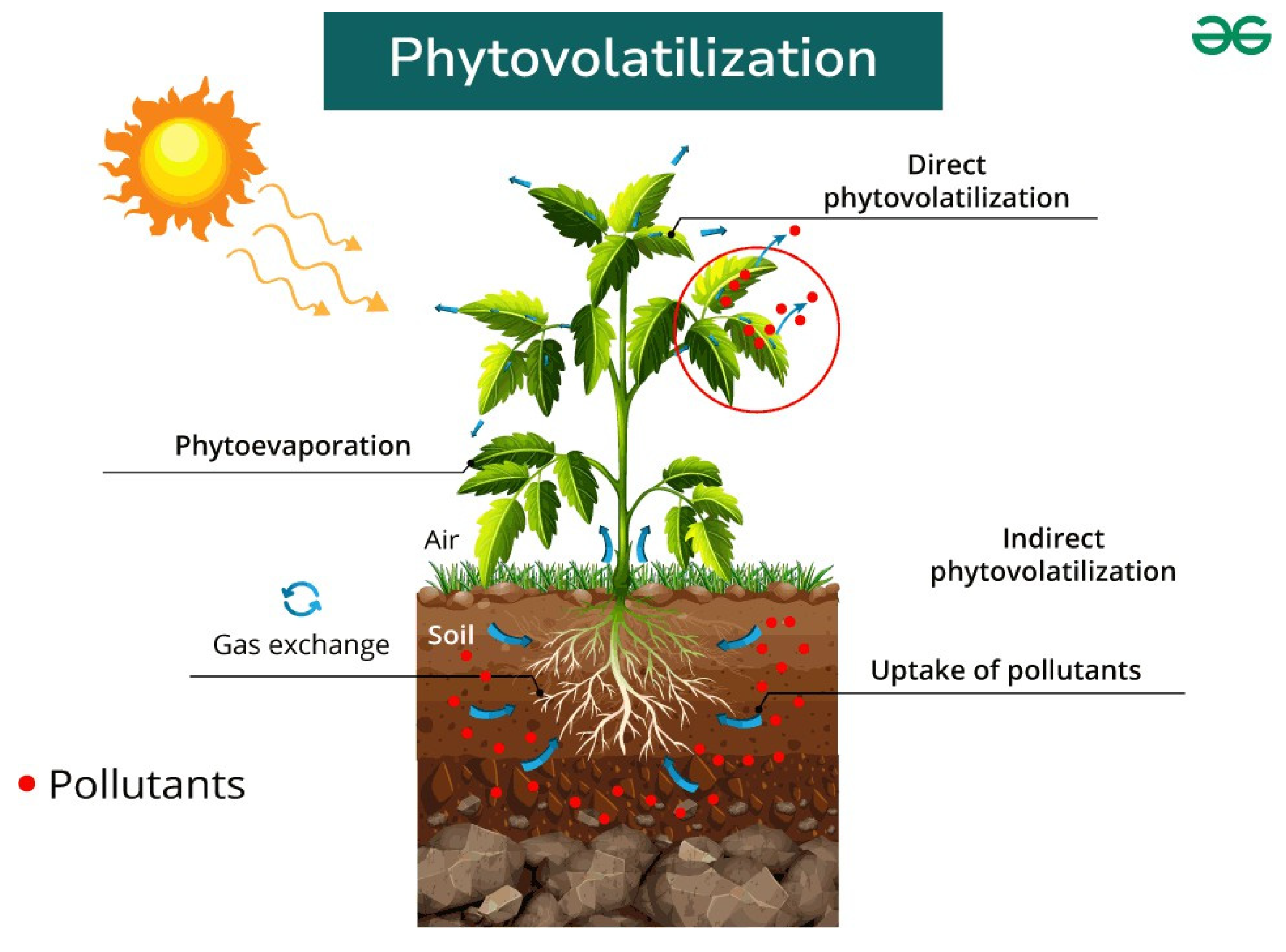

2.2.4. Phytovolatilization

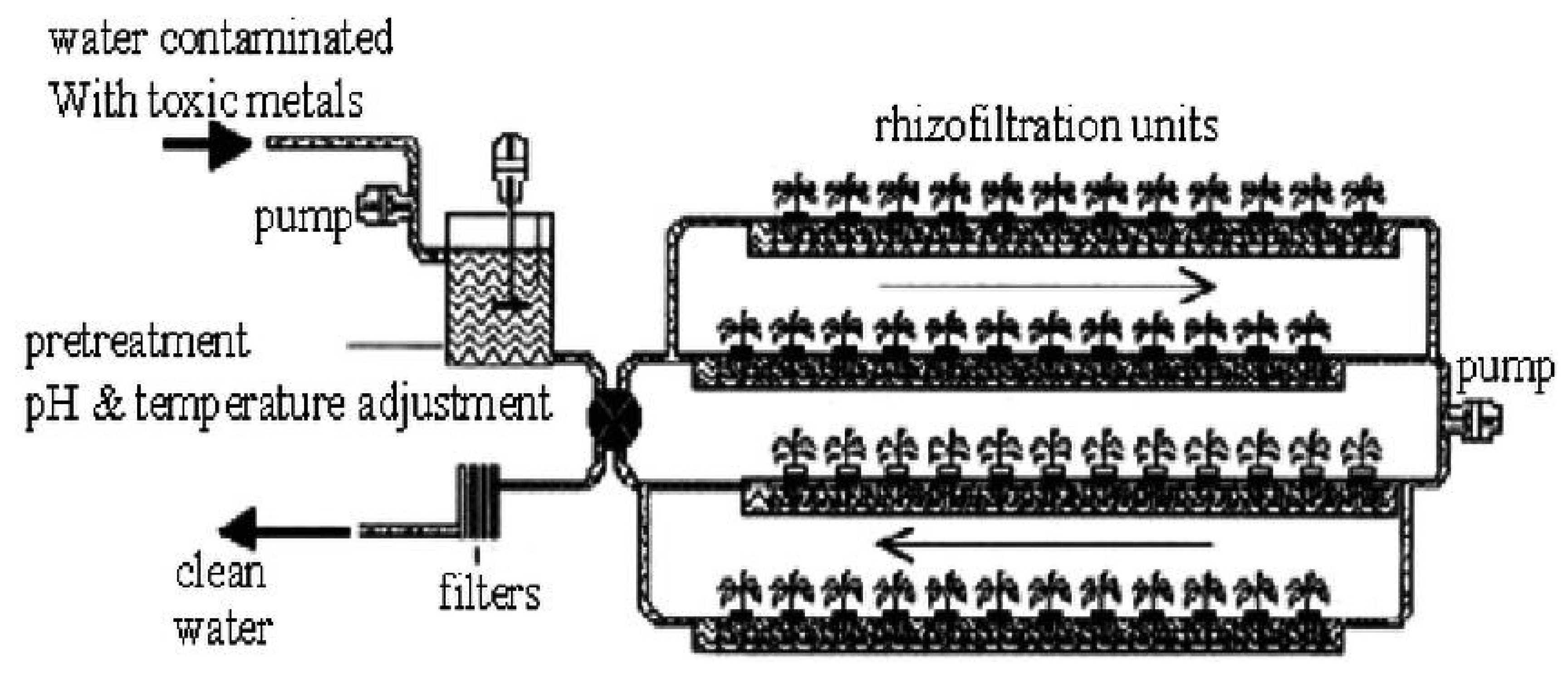

2.2.5. Rhizofiltration

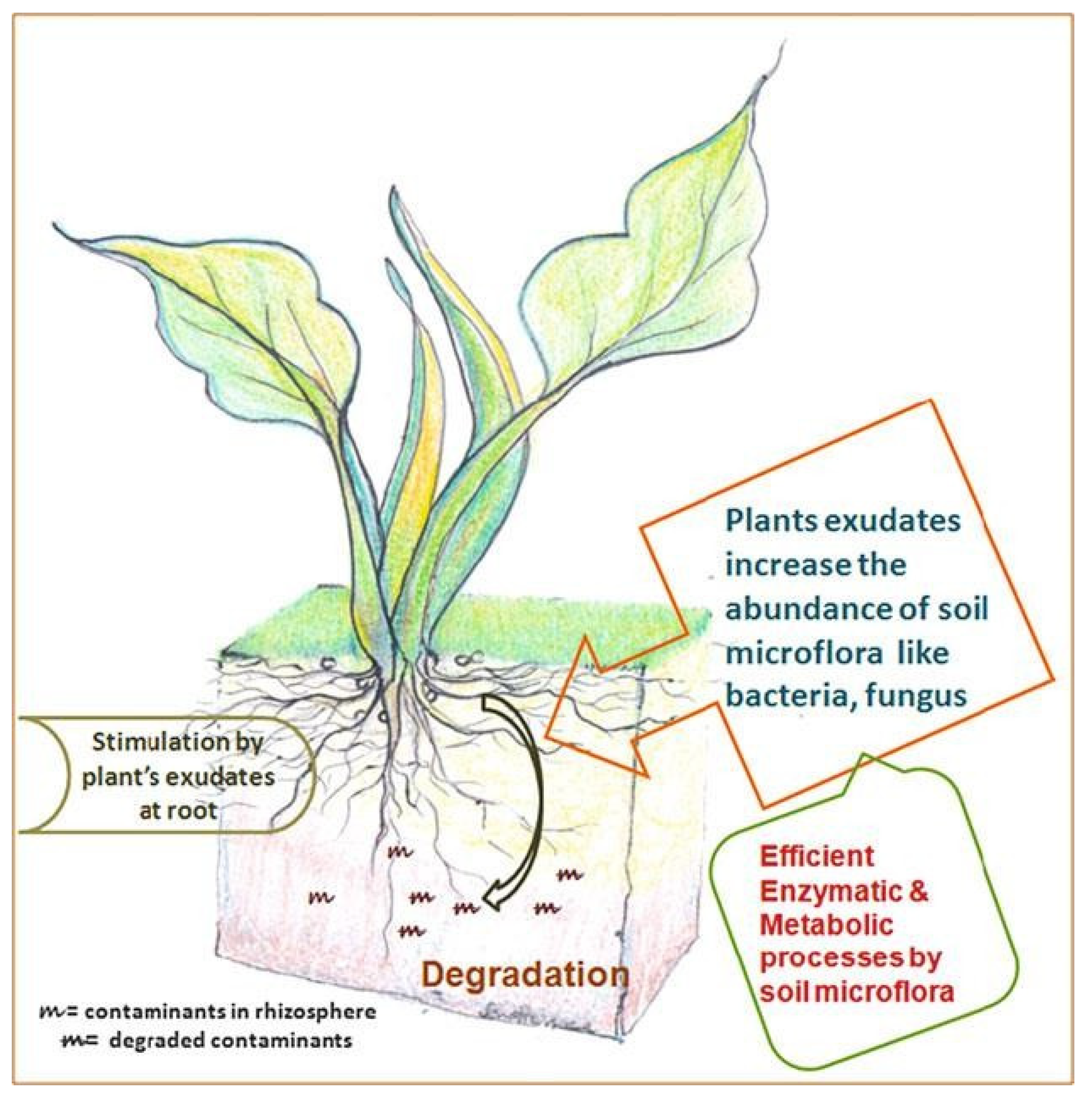

2.2.6. Phyto Stimulation

2.3. Phytoremediation Advantages

- ♦

- It can use solar energy to survive.

- ♦

- It’s easy to manage and easy to install.

- ♦

- Its maintenance is low.

- ♦

- It’s very economically feasible.

- ♦

- It can reduce exposure to pollutants in the environment and the ecosystem.

- ♦

- It can be applied over a large-scale field easily.

- ♦

- Stabilizing heavy metals can reduce the risk of spreading contaminants by preventing the metal from leaching and erosion.

- ♦

- Releasing various organic matter into the soil improves the soil fertility.

- ♦

- It can easily be disposed of when the time comes.

Chapter 3: Phytoremediation in Action

3.1. Environmental Applications of Phytoremediation

3.1.1. Soil

3.1.2. Water Treatment

3.1.3. Air

3.1.4. Heavy Metal Sites

3.2. Potential Biodiverse Flora

| Common name | Scientific name | Contaminants | References |

| Colonial bentgrass | Agrostis capillaris | As, Pb, Cu, Ni | (sladkovska et al., 2022), (kukreja & |

| goutam, 2012) | |||

| Creeping bentgrass | Agrostis stolonifera | Cd, Pb, Zn, As, Cu | (sladkovska et al., 2022), (kukreja & |

| goutam, 2012) | |||

| Mouse ear cress | Arabdidopsis helleri | Cd, Zn | (kafle, et al.,2022), (sabir etal., |

| 2015), (sladkovska et al., 2022), | |||

| Mouse-ear cress | Arabidopsis thaliana | Cd | (sladkovska et al., 2022), (sabir etal., |

| 2015) | |||

| Water velvet | Azolla caroliniana | As | (kafle et al.,2022), (sladkovska et |

| al., 2022 | |||

| Desert broom | Baccharis sarothroids | Pb, Cr, Cu, Ni, Zn and | (kukreja & goutam, 2012), (sabir |

| gray | As | etal., 2015) | |

| Indian mustard | Brassica juncea | Pb, Cd | (kafle et al.,2022), (sabir etal., |

| 2015), (kukreja & goutam, 2012), (islam et al., 2024) | |||

| Broccoli | Brassica oleracea var. | Se | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| Italica | 2024) | ||

| Boxwood | Buxaceae | Ni | (kukreja & goutam, 2012), (sabir |

| etal., 2015) | |||

| Water starwort | Callitriche lusitanica | As | (islam et al., 2024), (kafle et |

| al.,2022), | |||

| Vetivergrass | Chrysopogon zizanioides | As | (kukreja & goutam, 2012), (sabir |

| etal., 2015) | |||

| Commelina | Commelina communis | Cu | (kafle et al.,2022), (kukreja & |

| goutam, 2012) | |||

| Bermuda grass | Cynodon dactylon | As, Zn, Pb | (sabir etal., 2015), (kukreja & |

| goutam, 2012) | |||

| Cocksfoot grass | Dactylis glomerata | Cd, Zn, Pb | (sladkovska et al., 2022), (kukreja & |

| goutam, 2012) | |||

| Water hyacinth | Eichhornia crassipes | Fe, Cr, Cu, Cd, Zn, Ni, | (islam et al., 2024), |

| As | (kafle et al.,2022), | ||

| Cactus-like succulents | Euphoribiaceae | Ni | (kukreja & goutam, 2012), |

| (sladkovska et al., 2022 | |||

| Festuca rubra | Zn, Pb | (sladkovska et al., 2022), (kukreja & | |

| goutam, 2012) | |||

| Sunflower | Helianthus annuus | Cs (roots) and Sr | (kukreja & goutam, 2012), (kafle et |

| (shoots) | al.,2022) | ||

| Common rush | Juncus effuses | Ammonium | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| 2024) | |||

| Mangrove | Kandelia candel (l.) | Phenanthrene (ph) and | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| Druce | pyrene (py) | 2024) | |

| Lettuce | Lactuca sativa | Ni, Co, Pb, Cr, Cu and | (kafle et al.,2022), (kukreja & |

| Fe | goutam, 2012), (islam et al., 2024) | ||

| Bottle gourd | Lagenaria siceraria | Pb, Zn | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| 2024) | |||

| Annual ryegrass | Lolium italicum | Zn, pb | (sladkovska et al., 2022), (kukreja & |

| goutam, 2012) | |||

| Perennial rye grass | Lolium perenne | Ni, Co, and Fe | (kafle et al.,2022), (sladkovska et |

| al., 2022 | |||

| Sweet yellow clover | Melilotus officinalis | Zn, Pb, Cu | (islam et al., 2024), (sladkovska et |

| al., 2022 | |||

| Vygies | Mesembryanthemum | Pb | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| criniforum | 2024) | ||

| Tobacco | Nicotiana tabacum | Cd | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| 2024) | |||

| Atra Paspalum | Paspalum atratum | Zn, Cd | (islam et al., 2024), (sladkovska et |

| al., 2022 | |||

| Geranium | Pelargonium hortorum | Pb | (kafle et al.,2022), (sladkovska et |

| al., 2022 | |||

| Geranium | Pelargonium hortorum | Pb | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| 2024) | |||

| Garden geranium | Pelargonium hortorum | Pb, Cd | (kafle et al.,2022) |

| Napier grass | Pennisetum purpureum | Zn, Cr, Cu | (islam et al., 2024), (kafle et |

| al.,2022), | |||

| Perennial reed grass | Phragmites australis | Ibuprofen | (islam et al., 2024), (kafle et |

| al.,2022), | |||

| Rabbitfoot grass | Polypogonmon | As | (islam et al., 2024), (kafle et |

| speliensis | al.,2022) | ||

| Chinese brake ferns | Pteris vittate | Arsenic (as) | (kafle et al.,2022), (sabir etal., |

| 2015), (islam et al., 2024) | |||

| Paitara/ Murta | Schumannianthus | BOD, COD, Nitrate, | (sladkovska et al., 2022), |

| Dichotomus | Nitrite. | ||

| Saltmarsh bulrush | Scirpus robustus | Se | (islam et al., 2024), (kafle et |

| al.,2022), | |||

| Sedum alfredii hance | Sedum alfredii | Pb | (kafle et al.,2022), (kukreja & |

| goutam, 2012) | |||

| Rattlebush | Sesbania drummondii | Pb | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| 2024) | |||

| Black nightshade | Solanum nigrum | Cd, pb | (kafle et al.,2022), (sladkovska et |

| al., 2022 | |||

| Alpine pennygrass | Thlaspi caerulescens | Cd, Zn, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb | (kafle et al.,2022), (sabir etal., |

| 2015), (kukreja & goutam, 2012) | |||

| Berseem clover | Trifolium olexandrinum | Zn, Cd, Pb, Cu | (sladkovska et al., 2022), |

| Cattail | Typha angustifolia | Cu, Pb, Ni, Fe, Mn, and | (islam et al., 2024), (kafle et |

| Zn | al.,2022) | ||

| Common cocklebur | Xanthium strumarium | Cd, Pb, Ni, Zn | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| 2024) | |||

| Corn | Zea mays | Pb, Ti | (kafle et al.,2022), (islam et al., |

| 2024) |

3.3. Global Cases of Phytoremediation

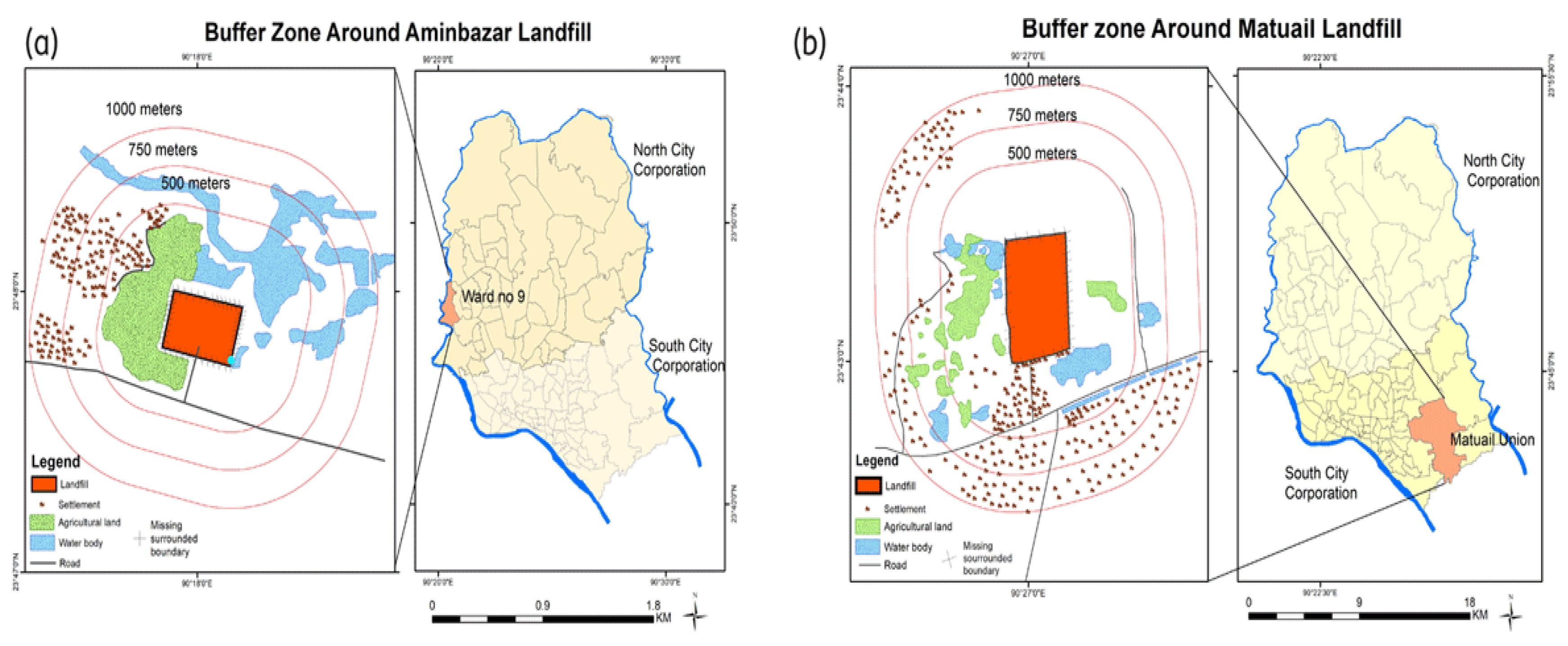

Chapter 4: A Rising Green Technology in Bangladesh: Phytoremediation

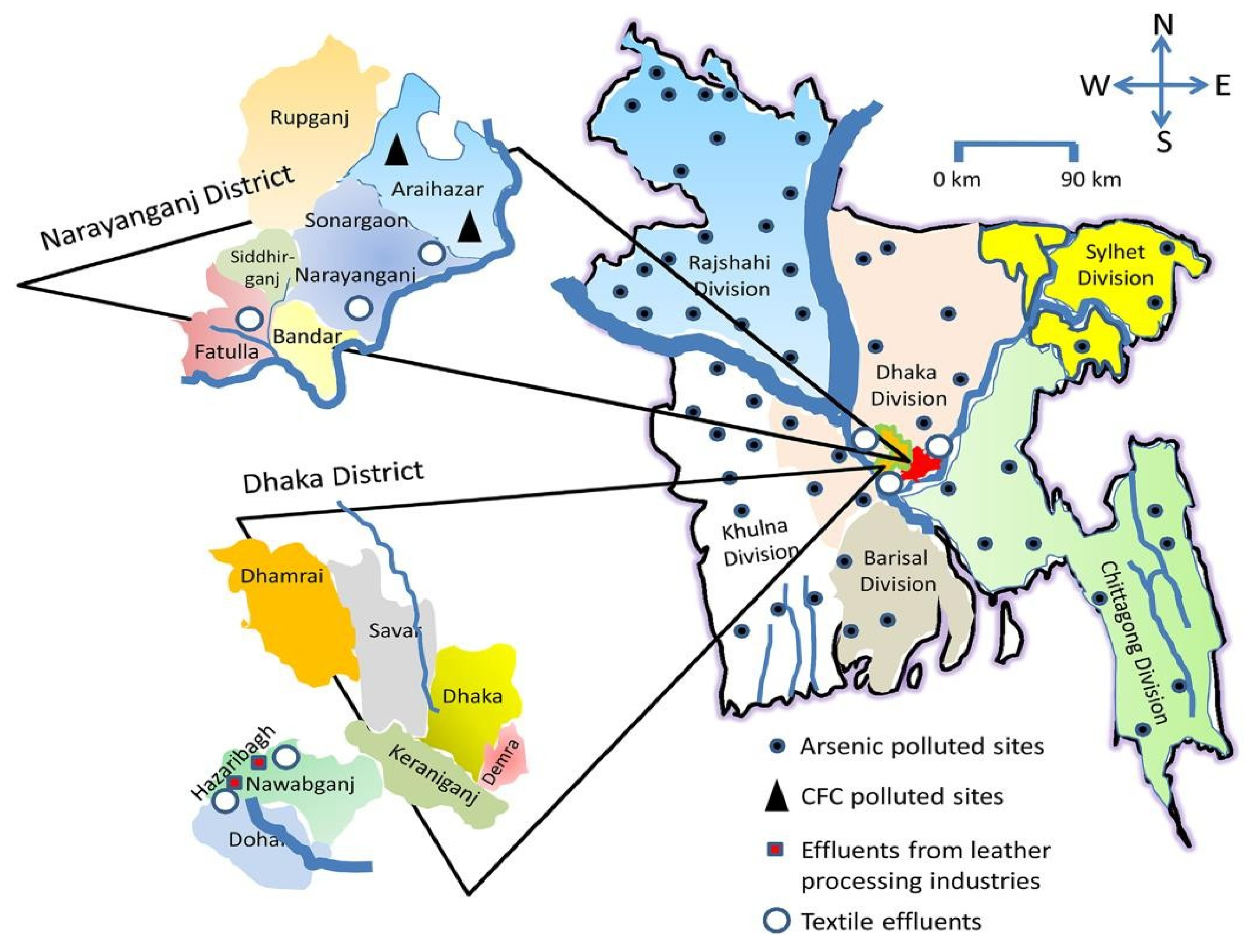

4.1. Bangladesh Overview

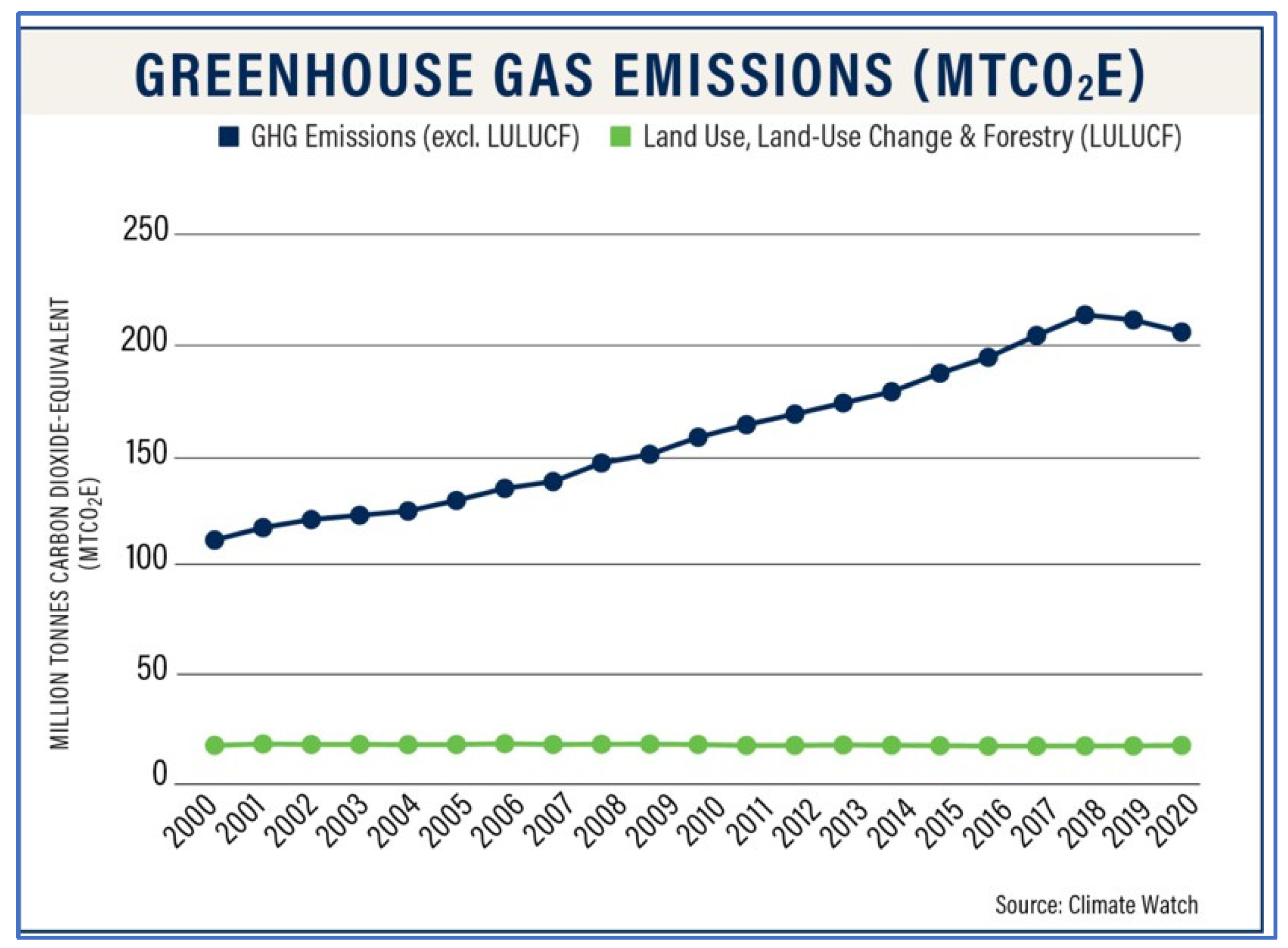

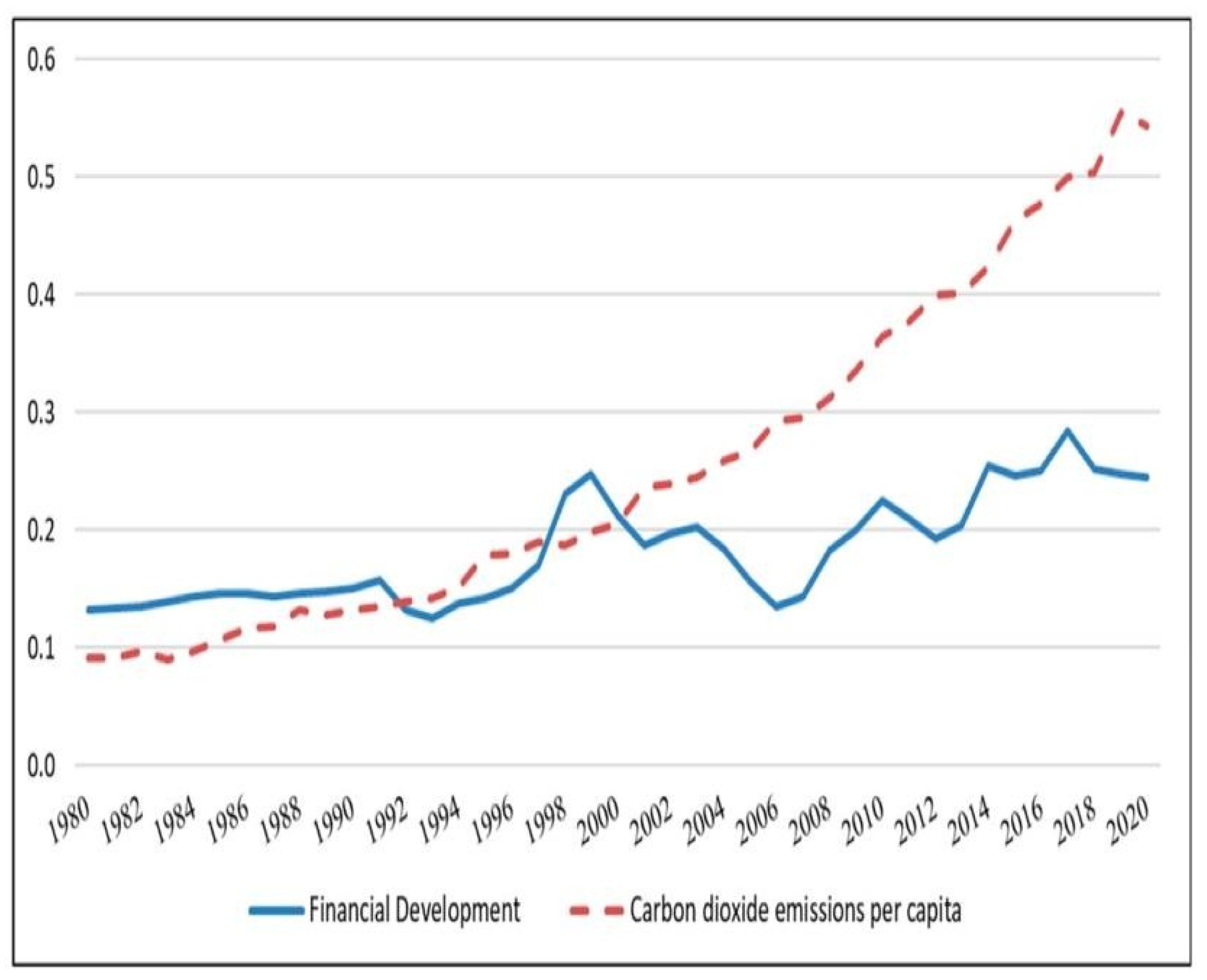

4.2. Carbon Emission in BD

4.3. Remediation Scenario in Bangladesh

| Regulations | Year | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act 1995, amended in 2000, 2002, and 2010 |

1995 | DoE |

| National Environmental Management Action Plan | 1995 | DoE |

| Environmental Conservation Rules 1997 | 1997 | DoE |

| Lead Acid Battery Recycling Related Circular | 2006 | DoE |

| Medical Waste (Management and Handling) Rules 2008 | 2008 | DoE |

| National 3R Strategy for Waste Management 2010 | 2010 | DoE |

| Local Government (City Corporation) (Amended) Act 2011 |

2011 | LGD |

| Hazardous Waste and Ship Breaking Waste Management Rules 2011 |

2011 | DoE |

| Ship Breaking and Recycling Rules 2011 | 2011 | Ministry of Industries |

| National Environmental Policy 2013 | 2013 | DoE |

| Seventh Five Years Plan (FY 2016–FY 2020) | 2015 | Ministry of Planning |

| Electrical and Electronic Product Induced Waste (E- waste) Management Rules 2017 |

2017 | DoE |

| Draft Solid Waste Management Rules 2018 | 2018 | DoE |

4.4. Phytoremediation Prospects in Bangladesh

Chapter 5: Obstacles to Implementing Phytoremediation in Bangladesh

5.1. Challenges & Future Prospects

5.2. Conclusions

References

- Abdel-Shafy, H. I., & Mansour, M. S. M. (2018). Solid waste issues: Sources, composition, disposal, recycling, and valorization. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum, 27(4), 1275–1290.

- Adnan, M., Xiao, B., Ali, M. U., Xiao, P., Zhao, P., Wang, H., & Bibi, S. (2024). Heavy metals pollution from smelting activities: A threat to soil and groundwater. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 274, 116189.

- Akbar, S. A., Lestari, A. N., Fazli, R. R., & Gunawan, G. (2025). Harnessing macroalgae for heavy metal phytoremediation: A sustainable approach to aquatic pollution control. In BIO Web of Conferences (Vol. 156, p. 02013). EDP Sciences.

- Alam, M. S., Han, B., & Pichtel, J. (2020). Assessment of soil and groundwater contamination at a former Tannery district in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 42(7), 1905-1920.

- Ali, H., Khan, E., & Sajad, M. A. (2013). Phytoremediation of heavy metals—concepts and applications. Chemosphere, 91(7),869-881.

- Ali, S., Abbas, Z., Rizwan, M., Zaheer, I. E., Yavaş, İ., Ünay, A., … & Kalderis, D. (2020). Application of floating aquatic plants in phytoremediation of heavy metals polluted water: A review. Sustainability, 12(5), 1927.

- Alkorta, I., Hernández-Allica, J., Becerril, J. M., Amezaga, I., Albizu, I., & Garbisu, C. (2004). Recent findings on the phytoremediation of soils contaminated with environmentally toxic heavy metals and metalloids such as zinc, cadmium, lead, and arsenic. Reviews in Environmental Science and Biotechnology, 3, 71-90. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:RESB.0000040059.70899.3d.

- Alsafran, M., Usman, K., Ahmed, B., Rizwan, M., Saleem, M. H., & Al Jabri, H. (2022). Understanding the phytoremediation mechanisms of potentially toxic elements: a proteomic overview of recent advances. Frontiers in plant science, 13, 881242.

- Ashraf, S., Ali, Q., Zahir, Z. A., Ashraf, S., & Asghar, H. N. (2019). Phytoremediation: An environmentally sustainable way for the reclamation of heavy metal polluted soils. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, 174, 714-727.

- Aweng, E. R., Irfan, A. M., Liyana, A. A., & Aisyah, S. S. (2018). Potential of phytoremediation using Scirpus validus for domestic waste open dumping leachate. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management, 22(1), 74-78.

- Azubuike, C. C., Chikere, C. B., & Okpokwasili, G. C. (2016). Bioremediation techniques–classification based on site of application: principles, advantages, limitations and prospects. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 32, 1-18. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/S11274-016-2137-X.

- Babu, S. M. O. F., Hossain, M. B., Rahman, M. S., Rahman, M., Ahmed, A. S. S., Hasan, M. M., Rakib, A., Emran, T. B., Xiao, J., & Simal-Gandara, J. (2021). Phytoremediation of Toxic Metals: A Sustainable Green Solution for Clean Environment. Applied Sciences, 11(21), 10348. [CrossRef]

- Baeder-Bederski-Anteda, O. (2003). Phytovolatilisation of organic chemicals. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 3, 65-71.

- Bakshe, P., & Jugade, R. (2023). Phytostabilization and rhizofiltration of toxic heavy metals by heavy metal accumulator plants for sustainable management of contaminated industrial sites: A comprehensive review. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, 10, 100293.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, (2020). Bangladesh- An Overview. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. BBC News, (2024). Bangladesh country profile. BBC News.

- Bezie, Y., Taye, M., & Kumar, A. (2021). Recent advancement in phytoremediation for removal of toxic compounds. In Nanobiotechnology for Green Environment (pp. 195-228). CRC Press.

- Bisht, R., Chanyal, S., & Srivastava, R. K. (2020). A systematic review on phytoremediation technology: removal of pollutants from waste water and soil. Int J Res Eng Sci Manag, 3, 54-59.

- Boyle, R. (2024). Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Bangladesh. Emission Index.

- Briffa, J., Sinagra, E., & Blundell, R. (2020). Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans. Heliyon, 6(9).

- Chandan, Md. S. K. (2021). A tale of a landfill and its ravages. The Daily Star.

- Chatterjee, S., Mitra, A., Datta, S., & Veer, V. (2013). Phytoremediation protocols: an overview. Plant-based remediation processes, 1-18.

- Chen, C. C., Lin, M. S., Cheng, P. C., Huang, C. Y., & Cheng, S. F. (2024). Strategy of Phytoremediation for Sustainable Use of Arsenic-Rich Farmland. Engineering Proceedings, 74(1), 8.

- Chojnacka, K., Moustakas, K., & Mikulewicz, M. (2023). The combined rhizoremediation by a triad: plant-microorganism-functional materials. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(39), 90500-90521.

- Cohen, A. J., Brauer, M., Burnett, R., Anderson, H. R., Frostad, J., Estep, K., … & Forouzanfar, M. H. (2017). Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. The lancet, 389(10082), 1907-1918.

- Cundy, A. B., Bardos, R. P., Puschenreiter, M., Mench, M., Bert, V., Friesl-Hanl, W., … & Vangronsveld, J. (2016). Brownfields to green fields: Realising wider benefits from practical contaminant phytomanagement strategies. Journal of Environmental Management, 184, 67-77.

- Cunningham, S. D., & Lee, C. R. (1995). Phytoremediation: Plant-based remediation of contaminated soils and sediments. Bioremediation: Science and applications, 43, 145-156. Available online: https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.2136/sssaspecpub43.c9.

- Desa U (2019) World population prospects 2019: highlights. In: New York (US): United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs, 11(1): 125.

- Devi, P., & Kumar, P. (2020). Concept and application of phytoremediation in the fight against heavy metal toxicity. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 12(6), 795-804.

- Dhaliwal, S. S., Singh, J., Taneja, P. K., & Mandal, A. (2020). Remediation techniques for removal of heavy metals from the soil contaminated through different sources: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(2), 1319-1333. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11356-019-06967-1.

- Dushenkov, V., Kumar, P. N., Motto, H., & Raskin, I. (1995). Rhizofiltration: the use of plants to remove heavy metals from aqueous streams. Environmental science & technology, 29(5), 1239-1245.

- Ekperusi, A. O., Sikoki, F. D., & Nwachukwu, E. O. (2019). Application of common duckweed (Lemna minor) in phytoremediation of chemicals in the environment: State and future perspective. Chemosphere, 223, 285-309.

- Etim, E. E. (2012). Phytoremediation and its mechanisms: a review. Int J Environ Bioenergy, 2(3), 120-136.

- GeeksforGeeks, 2024, Overview on Phytoremediation: Process, Types, and Application. GeeksforGeeks.

- Ghosh, M., & Singh, S. P. (2005). A review on phytoremediation of heavy metals and utilization of its by-products. Asian J Energy Environ, 6(4), 18.

- Gour, A., Panwar, M., & Sahu, N., (2018). STUDY OF PHYTOREMEDIATION POTENTIAL IN CATHARANTHUS ROSEUS (PERIWINKLE). GLOBAL JOURNAL OF ENGINEERING SCIENCE AND RESEARCHES, 457–461.

- Greipsson, S. (2011) Phytoremediation. Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):7.

- Gurjat, B. G., Molina, L., & Ojha, C. (2010). Air Pollution: Health and Environmental Impacts. Boca Raton, London, New York: CRC Press.

- Guya, G. L. T. T. K.(n.d.) Impacts of Tannery Effluent on the Environment and Human Health. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234664866.pdf.

- Hamidpour, M., Nemati, H., Abbaszadeh Dahaji, P., & Roosta, H. R. (2020). Effects of plant growth-promoting bacteria on EDTA-assisted phytostabilization of heavy metals in a contaminated calcareous soil. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 42(8), 2535-2545.

- HariharaSudhan, C., Anuradha, B., Jayadevsivani, S., & Gokul, K. (2021). Polluted Landfill adaptation into agricultural soil: heavy metal phytoremediation with Indian Black Mustard (Brassica Nigra) and Dolomitic Lime Fertilizer. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 1026, No. 1, p. 012005). IOP Publishing.

- Hasan, M. M., Uddin, M. N., Ara-Sharmeen, I., F. Alharby, H., Alzahrani, Y., Hakeem, K. R., & Zhang, L. (2019). Assisting Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals Using Chemical Amendments. Plants, 8(9), 295.

- Hasan, S. M. M., Akber, M. A., Bahar, M. M., Islam, M. A., Akbor, M. A., Siddique, M. A. B., & Islam, M. A. (2021). Chromium contamination from tanning industries and Phytoremediation potential of native plants: A study of Savar tannery industrial estate in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 106(6), 1024-1032.

- Hegazy, A. K., Hussein, Z. S., Mohamed, N. H., Safwat, G., El-Dessouky, M. A., Imbrea, I., & Imbrea, F. (2023). Assessment of Vinca rosea (Apocynaceae) potentiality for remediation of crude petroleum oil pollution of soil. Sustainability, 15(14), 11046.

- Hossain, M. B., Masum, Z., Rahman, M. S., Yu, J., Noman, M. A., Jolly, Y. N., Begum, B. A., Paray, B. A., & Arai, T. (2022). Heavy Metal Accumulation and Phytoremediation Potentiality of Some Selected Mangrove Species from the World’s Largest Mangrove Forest. Biology, 11(8), 1144.

- Huang D, Hu C, Zeng G, Cheng M, Xu P, Gong X, Wang R, Xue W. (2016) Combination of Fenton processes and biotreatment for wastewater treatment and soil remediation. Sci. Total Environ 574: 1599–1610.

- Islam, M. M., Saxena, N., & Sharma, D. (2024). Phytoremediation as a green and sustainable prospective method for heavy metal contamination: a review. RSC Sustain 2: 1269–1288.

- Juel, M. A. I., Dey, T. K., Akash, M. I. S., & Das, K. K. (2021). Heavy Metals Phytoremidiation Potential of Napier Grass Cultivated on Tannery Sludge in Bangladesh. Journal of Engineering Science, 12(1), 35–41.

- Kafle, A.,Timilsina, A.,Gautam, A.,Adhikari, K.,Bhattarai, A., Aryal, N., (2022). Phytoremediation: Mechanisms, plant selection and enhancement by natural and synthetic agents. Volume 8.

- Khanm, F., Zaman, H., & Rahman, M. K. (2024). Phytoremediation Potentiality of Bottle Gourd Plant (Lagenaria siceraria). Journal of Biodiversity Conservation and Bioresource Management, 10(1), 59–74. [CrossRef]

- Khatun, F., Saadat, S. Y., Ashraf, K., (n.d.). BREATHING UNEASY: An Assessment of Air Pollution in Bangladesh. Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).

- Kukreja, S., & Goutam, U. (2013). Phytoremediation: a new hope for the environment. Front Recent Develop Plant Sci, 1, 149-171.

- Kumar, A., Dadhwal, M., Mukherjee, G., Srivastava, A., Gupta, S., & Ahuja, V. (2024). Phytoremediation: Sustainable Approach for Heavy Metal Pollution. Scientifica, 2024, 3909400. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M., Seth, A., Singh, A. K., Rajput, M. S., & Sikandar, M. (2021). Remediation strategies for heavy metals contaminated ecosystem: A review. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, 12, 100155.

- Kurwadkar, S., Kanel, S. R., & Nakarmi, A. (2020). Groundwater pollution: Occurrence, detection, and remediation of organic and inorganic pollutants. Water Environment Research, 92(10), 1659-1668.

- Lacalle, R. G., Bernal, M. P., Álvarez-Robles, M. J., & Clemente, R. (2023). Phytostabilization of soils contaminated with As, Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn: Physicochemical, toxicological and biological evaluations. Soil & Environmental Health, 1(2), 100014.

- Linacre, N. A., Whiting, S. N., & Angle, J. S. (2015). Incorporating project uncertainty in novel environmental biotechnologies.

- Mahmud, R., Inoue, N., Kasajima, S. ya, & Shaheen, R. (2008). Assessment of Potential Indigenous Plant Species for the Phytoremediation of Arsenic-Contaminated Areas of Bangladesh. International Journal of Phytoremediation, 10(2), 119–132.

- Mallick, S. R., Proshad, R., Islam, M. S., Sayeed, A., Uddin, M., Gao, J., & Zhang, D. (2019). Heavy metals toxicity of surface soils near industrial vicinity: A study on soil contamination in Bangladesh. Archives of agriculture and environmental science, 4(4), 356-368.

- Malone S (2022) Developments in Industrial Waste Biodegradation and Bioremediation. J Res Development. 10:191.

- Manikandan, M., Kannan, V., Mahalingam, K., Vimala, A., & Chun, S. (2015). Phytoremediation potential of chromium-containing tannery effluent-contaminated soil by native Indian timber-yielding tree species. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology, 46(1), 100–108.

- Matheson, S., Fleck, R., Irga, P. J., & Torpy, F. R. (2023). Phytoremediation for the indoor environment: a state-of-the-art review. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology, 22(1), 249-280.

- McNeil, K. R. and Waring, S. (1992): – In Contaminated Land Treatment Technologies (ed. Rees J. F.), Society of Chemical Industry. Elsevier Applied Sciences, London.; pp. 143-159.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2017). Bangladesh: An Introduction. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bangladesh.

- Mishra, A., Mishra, S. P., Arshi, A., Agarwal, A., & Dwivedi, S. K. (2020). Plant- microbe interactions for bioremediation and phytoremediation of environmental pollutants and agro-ecosystem development. Bioremediation of Industrial Waste for Environmental Safety: Volume II: Biological Agents and Methods for Industrial Waste Management, 415-436.

- Mostafa, E., Dina, S. F., & Hossain, M. N. (2024). Prospects and Challenges of Heavy Metal Pollution Mitigation in the Bay of Bengal by Phytoremediation o. Haya Saudi J Life Sci, 9(4), 139-148.

- Mustafa, H. M., & Hayder, G. (2021). Recent studies on applications of aquatic weed plants in phytoremediation of wastewater: A review article. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 12(1), 355365.

- Newman, L. A., & Reynolds, C. M. (2004). Phytodegradation of organic compounds. Current opinion in Biotechnology, 15(3), 225-230.

- Nizam, M. U., Wahid-U-Zzaman, M., Rahman, M. M., & Kim, J.-E. (2016). Phytoremediation potential of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.), mesta (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.), and jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) in arsenic-contaminated soil. Korean Journal of Environmental Agriculture, 35(2), 111–120.

- OB, A., & Muchie, M. (2010). Remediation of heavy metals in drinking water and wastewater treatment systems: processes and applications. Int. J. Phys. Sci, 5, 1807- 1817.

- Oh, K., Cao, T., Li, T., & Cheng, H. (2014). Study on application of phytoremediation technology in management and remediation of contaminated soils. Journal of Clean Energy Technologies, 2(3), 216-220.

- Okon, E., Udo, O. O., Archibong, I. A., & Victor, I. A. (2020). Phytomechanistic processes in environmental clean-up: a biochemical perspective. Int J Res Innov Appl Sci, 213, 222.

- Oleksińska, Zuzanna (2015) Plants on duty – phytotechnologies and phytoremediation at a glance.

- Ouvrard, S., Leglize, P., & Morel, J. L. (2014). PAH phytoremediation: rhizodegradation or rhizoattenuation? International Journal of Phytoremediation, 16(1), 46-61.

- Pandey, V. C., & Bajpai, O. (2019). Phytoremediation: from theory toward practice. In Phytomanagement of polluted sites (pp. 1-49). Elsevier.

- Poitras, A. (2019). Phytodegradation and Environmental Remediation. RADIX ECOLOGICAL SUSTAINABILITY CENTER.

- Rahman, M. A., Rahaman, M. H., Yasmeen, S., Rahman, M. M., Rabbi, F. M., Shuvo, R., and Usamah, M. (2022). Phytoremediation Potential of Schumannianthus Dichotomus in Vertical Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetland.

- Rao, T. S., Panigrahi, S., & Velraj, P. (2022). Transport and disposal of radioactive wastes in the nuclear industry. In Microbial biodegradation and bioremediation (pp. 419-440). Elsevier.

- Sabir, M., Waraich, E. A., Hakeem, K. R., Öztürk, M., Ahmad, H. R., & Shahid, M. (2015). Phytoremediation: mechanisms and adaptations. Soil Remediation Plants, 4, 85-105.

- Saran, A., Imperato, V., Fernandez, L., Gkorezis, P., d’Haen, J., Merini, L. J., … & Thijs, S. (2020). Phytostabilization of polluted military soil supported by bioaugmentation with PGP-trace element tolerant bacteria isolated from Helianthus petiolaris. Agronomy, 10(2), 204.

- Shackira, A. M., & Puthur, J. T. (2019). Phytostabilization of heavy metals: understanding of principles and practices. Plant-metal interactions, 263-282.

- Sharma, J. K., Kumar, N., Singh, N. P., & Santal, A. R. (2023). Phytoremediation technologies and their mechanism for removal of heavy metal from contaminated soil: An approach for a sustainable environment. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1076876.

- Sharma, P., Singh, S. P., Pandey, S., Thanki, A., & Singh, N. K. (2020). Role of potential native weeds and grasses for phytoremediation of endocrine-disrupting pollutants discharged from pulp paper industry waste. In Bioremediation of pollutants (pp. 17-37). Elsevier.

- Sladkovska, T., Wolski, K., Bujak, H., Radkowski, A., & Sobol, Ł. (2022). A Review of Research on the Use of Selected Grass Species in Removal of Heavy Metals. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2587.

- Smith, B. (1993): Remediation update funding the remedy. – Waste Management. Environ. 4: 24-30.

- Song Z, Williams CJ, Edyvean RJ, (2000); Sedimentation of tannery wastewater.Water Res.. 34.

- Swetha, T. N., Rajasekar, B., Hudge, B. V., Mishra, P., & Harshitha, D. N. (2023). Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soils Using Various Flower and Ornamentals. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science, 35(18), 747-752.

- Tangahu, B. V., Przybysz, A., Mashudi, M., Popek, R., Faz, M. R. I., Titah, H. S. L., … & Mangkoedihardjo, S. (2024). Indoor CO2 phytoremediation using ornamental plants: A case study in Gresik, Indonesia. Ecological Research. Available online: https://esj-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1440-1703.12511.

- Teiri, H., Pourzamani, H., & Hajizadeh, Y. (2018). Phytoremediation of VOCs from indoor air by ornamental potted plants: a pilot study using a palm species under the controlled environment. Chemosphere, 197, 375-381.

- Timalsina, H., Gyawali, T., Ghimire, S., & Paudel, S. R. (2022). Potential application of enhanced phytoremediation for heavy metals treatment in Nepal. Chemosphere, 306, 135581.

- Urme, S.A., Radia, M.A., Alam, R., Chowdhury, M.U., Hasan, S., Ahmed, S., Sara, H.H., Islam, M.S., Jerin, D.T., Hema, P.S., Rahman, M., Islam, A.K.M.M., Hasan, M.T. and Quayyum, Z. (2021) ‘Dhaka landfill waste practices: addressing urban pollution and health hazards’, Buildings and Cities, 2(1), p. 700–716.

- Vinceti, M., Filippini, T., Biswas, A., Michalke, B., Dhillon, K. S., & Naidu, R. (2024). Selenium: A global contaminant of significant concern to the environment and human health. In Inorganic Contaminants and Radionuclides (pp. 427-480). Elsevier.

- Waste Management Department (WMD), (2021). WASTE MANAGEMENT REPORT. Dhaka South City corporation.

- World Bank Group, (2022). High Air Pollution Level is Creating Physical and Mental Health Hazards in Bangladesh: World Bank. World Bank Group.

- World Bank Group, (2022). Urgent Climate Action Crucial for Bangladesh to Sustain Strong Growth. World Bank Group.

- World Bank Group, (2024). Addressing Environmental Pollution is Critical for Bangladesh’s Growth and Development. World Bank Group.

- World Bank, (2024). Bangladesh Overview: Development news, research, data. World Bank.

- World Population Prospects, (2024). Dhaka Overview. United Nations.

- Yan, A., Wang, Y., Tan, S. N., Mohd Yusof, M. L., Ghosh, S., & Chen, Z. (2020). Phytoremediation: a promising approach for revegetation of heavy metal-polluted land. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 359.

- Yanitch, A., Kadri, H., Frenette-Dussault, C., Joly, S., Pitre, F. E., & Labrecque, M. (2020). A four-year phytoremediation trial to decontaminate soil polluted by wood preservatives: phytoextraction of arsenic, chromium, copper, dioxins and furans. International Journal of Phytoremediation, 22(14), 1505-1514.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).