1. Introduction

Coal mining has long driven industrial growth, yet its legacy—waste dumps and tailings—continues to degrade ecosystems and soil health well beyond site closure. With sustainability now a global priority, restoring these landscapes has become increasingly urgent [

1]. Surface mining severely disrupts soil structure and microbial communities, impairing nutrient cycling and ecological resilience. Effective reclamation must rebuild soil fertility and biodiversity to support future land use [

2]. Beyond ecological recovery, the integration of tailings dumps into agricultural use offers a dual benefit: mitigating mining’s environmental impact while promoting sustainable development with lasting economic, ecological, and social gains.

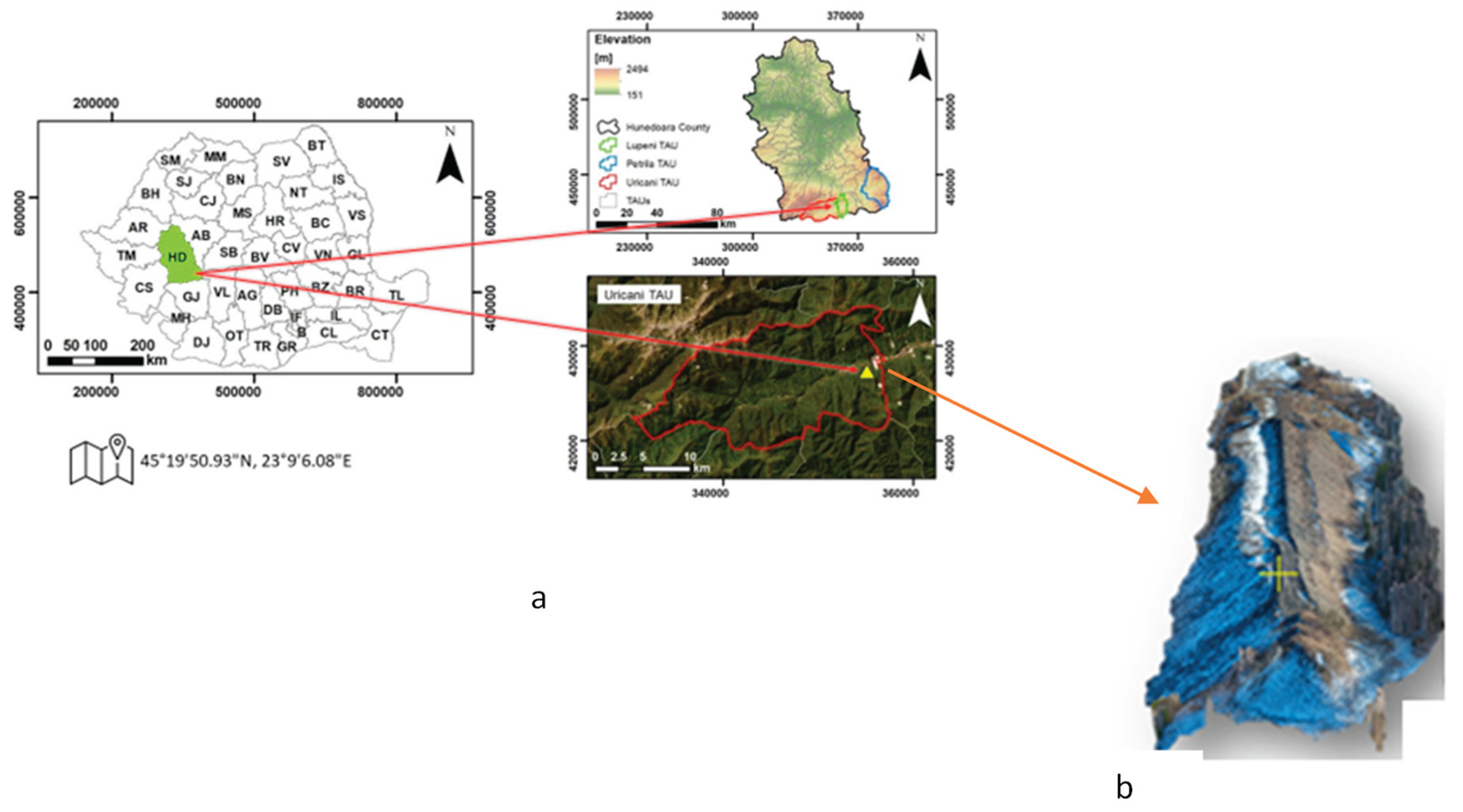

In Romania, mining activities have affected roughly 17,000 hectares, leaving behind 137 waste dumps and six tailing ponds containing nearly 2 billion cubic meters of residual material. Yet, only a fraction—about 2,000 hectares—has been reclaimed. The Jiu Valley region exemplifies both the scale of degradation and the promise of restoration, with 64 dumps covering over 250 hectares and holding approximately 37 million cubic meters of waste [

3]. Sites like the dormant E.M. Uricani dump underscore the pressing need for eco-logical rehabilitation, especially as Romania advances toward sustainable land use and a green economy [

4,

5].

Tailings dumps are typically marked by poor structure, low biological activity, and severe nutrient deficiencies, despite containing macronutrients (N, P, K, Ca, Mg) and micronutrients (Fe, Cu, Mn, Mo, Zn) alongside heavy metals that complicate reclamation efforts [

6]. Their coarse texture, high bulk density, and limited water infiltration hinder natural regeneration, which can take several generations—nitrogen levels alone may require up to 200 years to match those of native forest soils [

7]. Reclaimed soils often lose up to 80% of organic carbon and 50% of total nitrogen compared to undisturbed counterparts [

8], though long-term studies show that soil properties can improve over time, following polynomial recovery trajectories influenced by substrate composition, topography, microclimate, and reclamation strategy [

9,

10,

11]. Technical reclamation typically involves land reshaping, amendment application, and vegetation establishment to stabilize substrates and initiate ecological succession [

12]. Vegetation enhances soil development through root growth, litter deposition, and exudates that stimulate microbial communities essential for nutrient cycling and detoxification [

13,

14].

Robinia pseudoacacia is widely used for its nitrogen-fixing ability and tolerance to poor soils [

9,

15], while spontaneous succession—though slower—promotes biodiversity, improves soil structure, and attenuates heavy metals through natural ecological processes [

16,

17].

To evaluate the agricultural viability of reclaimed tailings, detailed soil chemical analyses are essential for tracking improvements in fertility, structure, and contaminant attenuation. Long-term revegetation efforts in Transylvania have demonstrated measurable gains in soil quality [

18], and broader studies confirm that both spontaneous and targeted vegetation enhance organic matter, nutrient cycling, and reduce toxic metal bioavailability [

12,

15]. Misebo et al. (2021) [

19] showed that vegetation type influences bulk density and water retention, with grasses and forbs improving topsoil and trees benefiting deeper layers. Hu et al. (2020) [

20] found that

Elymus nutans restoration increased organic matter and nitrogen while lowering pH and stabilizing cadmium, chromium, and lead. In tropical settings, Saidy et al. (2024) [

21] reported that vegetation combined with organic amendments reduced exchangeable aluminum and improved nutrient retention, supporting plant growth and limiting metal uptake.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of vegetation in restoring coal mine tailings, with a focus on soil nutrient dynamics and heavy metal distribution. By comparing soils without vegetation, soils with spontaneous herbaceous cover, and soils planted with Robinia pseudoacacia, the research investigates how vegetation type influences substrate quality over time. Soil parameters were assessed at two key intervals—3 and 6 years after plantation—to capture the early and intermediate stages of amelioration. Through integrated field sampling, laboratory analysis, and ecological evaluation, the study seeks to identify viable strategies for transforming degraded mining landscapes into ecologically stable and productive environments.

3. Results

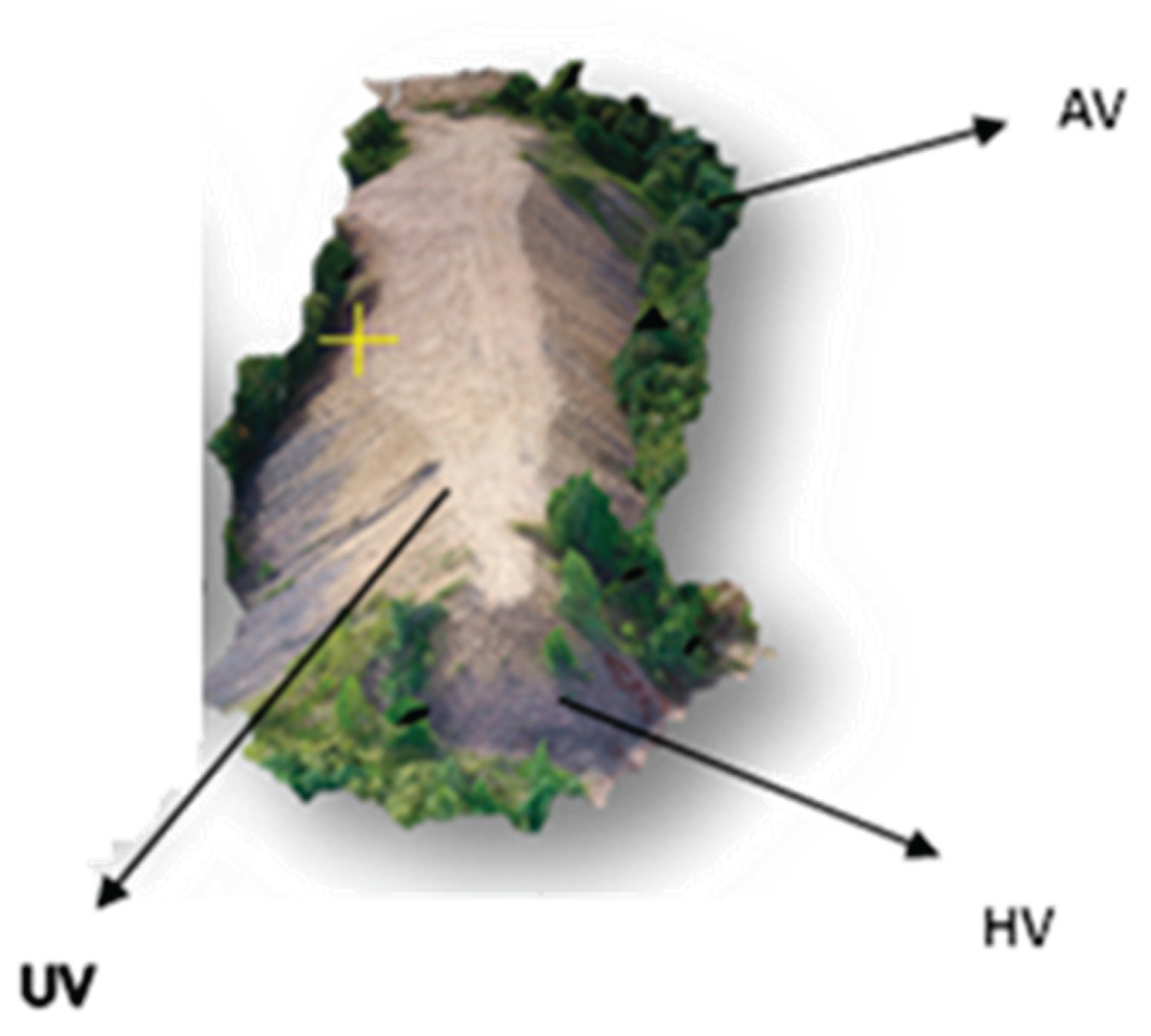

Table 1 summarizes the temporal dynamics of soil macronutrients across three vegetation types—arboreal (AV), herbaceous (HV), and unvegetated (UV)—over monitoring period atop coal mine tailings.

Soil pH measurements in 2021 and 2024 revealed a predominantly alkaline environment across all experimental plots, with values influenced by vegetation type. In 2021, arboreal vegetation (AV) plots had a mean pH of 8.13, herbaceous vegetation (HV) plots recorded 8.05, and unvegetated (UV) surfaces showed the highest pH at 8.57. By 2024, a consistent decline in pH was observed: AV dropped to 8.07, HV to 7.89, and UV to 8.52. These changes suggest progressive acidification driven by biological activity and environmental factors, with the most pronounced shift occurring in HV plots.

The data reveal consistent patterns in total nitrogen (TN) concentrations across vegetation types during the three-year monitoring interval. In both 2021 and 2024, soils under arboreal (AV) and herbaceous vegetation (HV) exhibited higher TN levels compared to unvegetated (UV) plots. Specifically, AV soils recorded a mean TN content of 0.230% in 2021, while HV soils showed a slightly lower value of 0.210%, indicative of active nitrogen turnover driven by plant-microbe interactions. In contrast, UV soils had the lowest TN concentration (0.163%), reflecting minimal biological input. By 2024, TN levels increased most notably in AV (0.247%) and HV (0.230%), whereas UV soils remained comparatively nitrogen-poor (0.170%), suggesting subdued microbial activity in the absence of vegetation.

Parallel trends were observed in organic carbon (OC) content, with vegetation presence strongly influencing carbon accumulation. In 2021, HV soils exhibited the highest OC levels (21.51 g kg-1), followed closely by AV soils (20.26 g kg-1). UV soils remained significantly lower (14.51 g kg-1), consistent with minimal organic matter input. In 2024, both HV and AV variants sustained elevated OC concentrations (22.63 and 21.13 g kg-1, respectively), while UV soils showed only a slight increase (15.63 g kg-1), reinforcing the role of vegetation in enhancing soil carbon stocks through litter deposition and microbial activity.

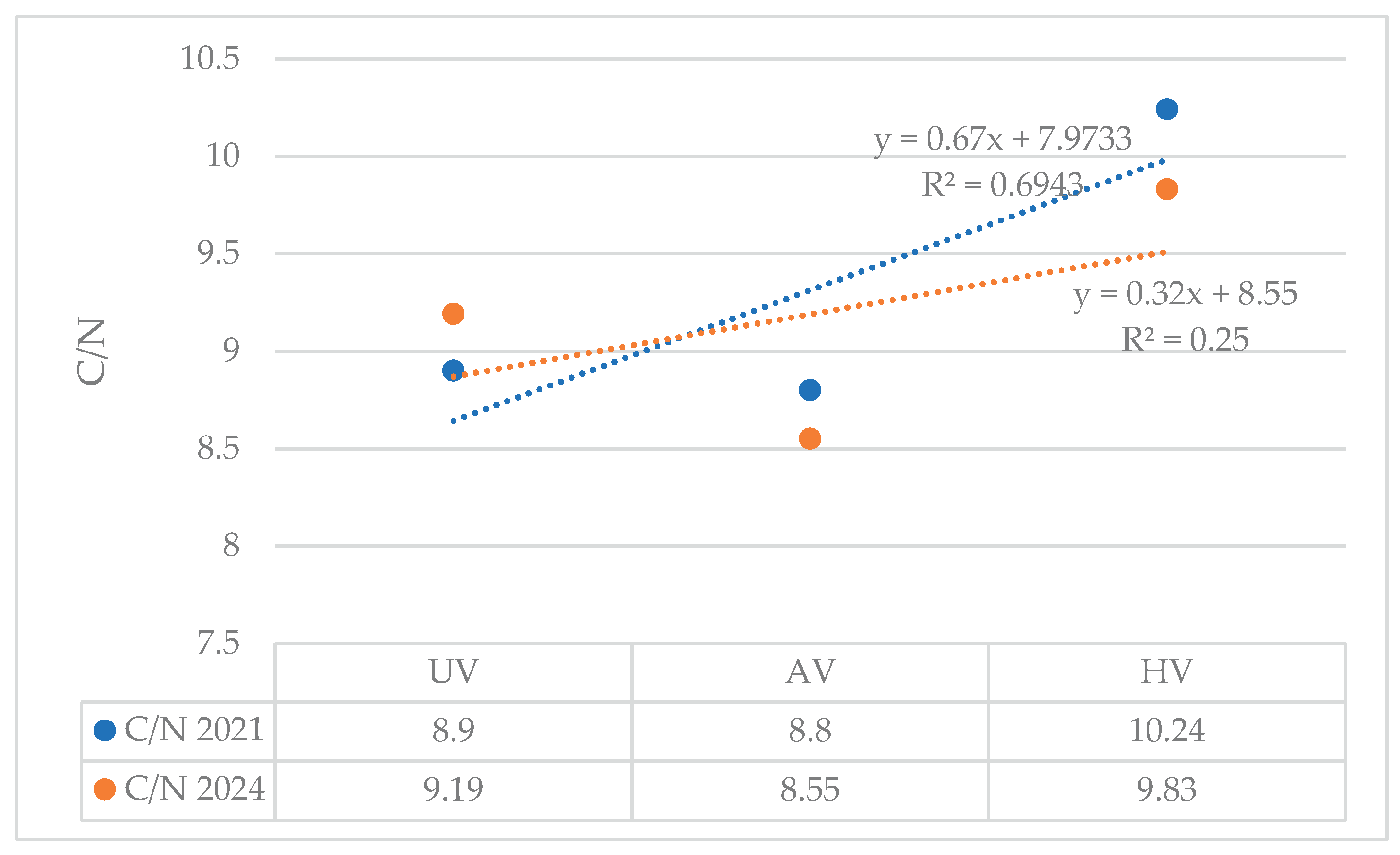

Figure 3 captures notable temporal variations in the organic carbon-to-total nitrogen (OC/TN) ratio across different vegetation types, underscoring the distinct influence of plant cover on soil organic matter dynamics.

In both years, a positive linear trend is evident, indicating that C/N ratios generally increase with vegetation complexity. The 2021 dataset exhibits a steeper regression slope (y = 0.67x + 7.9733, R² = 0.6943) compared to 2024 (y = 0.32x + 8.55, R² = 0.25), suggesting a stronger correlation between vegetation type and C/N ratio in 2021. The highest C/N values were recorded in HV plots, followed by AV, with UV plots consistently showing the lowest ratios. Notably, the 2024 data show a flatter slope and lower coefficient of determination, indicating greater variability and weaker predictability in C/N behavior across vegetation types.

The moderately alkaline pH observed across the study area provided a stable geochemical setting that supports mineral preservation while permitting biologically mediated nutrient transformations. Soils under arboreal vegetation (AV) consistently exhibited the highest concentrations of both exchangeable (P

AL) and total phosphorus (P

T) (

Table 1), with values rising from 0.024 mg kg

-1 and 448 mg kg

-1 in 2021 to 0.029 mg kg

-1 and 467 mg kg

-1 in 2024. These elevated levels are likely attributable to deep-rooting systems and substantial organic matter inputs from tree biomass, which enhance phosphorus mobilization even under alkaline conditions. Unexpectedly, unvegetated (UV) soils showed markedly higher levels of P

AL—0.226 mg kg

-1 in 2021 and 0.260 mg kg

-1 in 2024—alongside moderate P

T concentrations (403–432 mg kg

-1). This pattern may reflect surface-level accumulation and limited biological uptake due to the absence of vegetation. Herbaceous vegetation (HV) plots recorded the lowest concentrations of both P

AL and P

T, indicating restricted phosphorus mobilization—likely due to shallower root architecture and reduced organic inputs

Potassium concentrations followed a similar trend, with AV soils showing enrichment in both exchangeable and total forms. KAL ranged from 149 to 166 mg kg-1, while KT varied between 635 and 670 mg kg-1. Although KT slightly lower than in UV soils, the presence of vegetation suggests active nutrient cycling and uptake, promoting turnover rather than passive accumulation. KAL in HV soils were marginally lower than those in AV plots, while total potassium remained comparable, suggesting minimal variation in long-term accumulation. In contrast, UV soils exhibited the highest KT concentration in 2024 (1127 mg kg-1), likely resulting from continued weathering of potassium-bearing minerals such as feldspar, in the absence of biological export mechanisms.

As shown in

Table 1, soils under arboreal vegetation (AV) exhibited exceptionally high available calcium (Ca

av)concentrations (2854–3062 mg kg

-1), indicative of accelerated calcite dissolution likely driven by biological activity. Magnesium availability in these soils was also elevated (758–869 mg kg

-1), suggesting active biotite weathering facilitated by root exudates and microbial interactions typical of tree-dominated systems. In contrast, soils under herbaceous vegetation (HV) displayed reduced calcium and magnesium levels relative to both AV and unvegetated (UV) soils, pointing to subdued mineral weathering and diminished nutrient retention. Mg

av concentrations in HV soils showed a modest increase in 2024 (810 mg kg

-1), potentially reflecting seasonal variation or enhanced biotite decomposition during that period. Unvegetated soils presented intermediate Ca

av (1298–1563 mg kg

-1) and the lowest magnesium concentrations among all vegetation types (323–503 mg kg

-1). These findings suggest limited biotite degradation and poor nutrient retention dynamics in the absence of biological mediation.

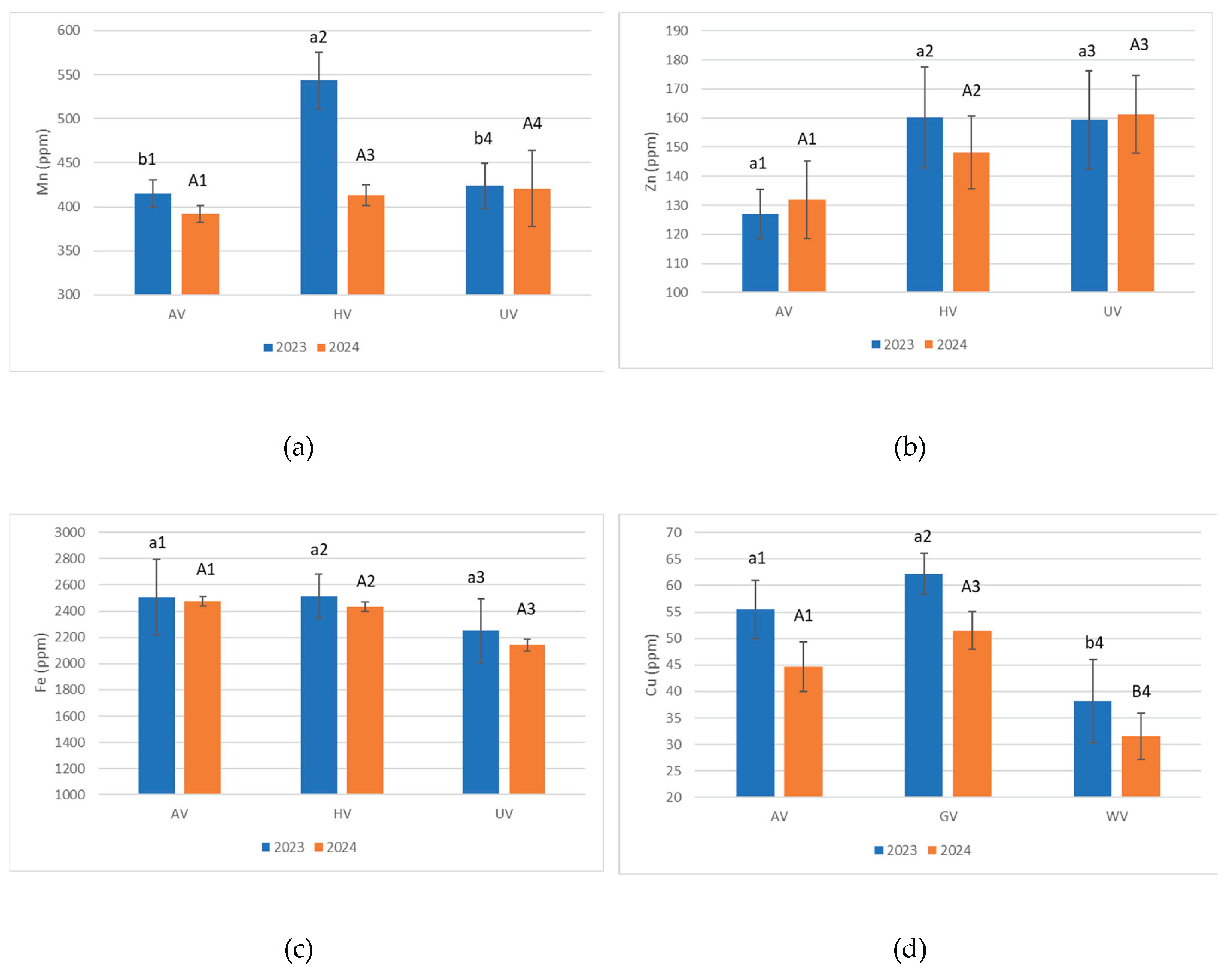

Pseudo-total Manganese (Mn) concentrations in the analyzed samples (

Figure 4a) ranged from 392 to 543 mg kg. The highest Mn levels were recorded in the HV plots (543 mg kg

-1 in 2021; 413 mg kg

-1 in 2024), indicating enhanced Mn mobilization under herbaceous vegetation. A comparative analysis revealed a decline in Mn concentrations between 2021 and 2024: −130 mg kg

-1 in HV and −23 mg kg

-1 in AV, suggesting diminished retention or elevated biological uptake and leaching. Conversely, UV exhibited a slight increase (+6 mg kg

-1), potentially attributable to surface accumulation in the absence of active plant uptake.

Pseudo-total zinc (Zn) concentrations (

Figure 4b) varied between 127.03 and 161.20 mg kg

-1. In 2024, UV plots exhibited the highest Zn level (161.20 mg kg

-1), whereas HV showed the peak value in 2021 (160.17 mg kg

-1). Relative to 2021, Zn concentrations in 2024 increased in AV and UV plots, while HV experienced the most substantial reduction (−11.94 mg kg

-1).

Pseudo total iron (Fe) concentrations ranged from 2144 to 2508 mg kg

-1 (

Figure 4c). The AV variant recorded the highest Fe content (2475 mg kg

-1 in 2021; 2508 mg kg

-1 in 2024), likely linked to interactions between deeper root systems and Fe-rich minerals such as biotite. UV samples (2250 mg kg

-1 in 2021; 2144 mg kg

-1 in 2024) presented consistently lower values, underscoring the influence of vegetation in Fe stabilization and mobilization. All variants experienced pseudo-total Fe reductions from 2021 to 2024, with the steepest decline observed in UV (−106 mg kg

-1), presumably due to rainfall-induced leaching in the absence of stabilizing vegetation. Lesser declines in AV and HV may be attributed to root-mediated retention processes.

Pseudo-total copper (Cu) concentrations (

Figure 4d) were generally higher in 2021, ranging from 38.25 to 62.19 mg kg

-1, compared to 2024 values, which declined to a range of 31.52 to 51.53 mg kg

-1. The highest Cu concentration was recorded in herbaceous vegetation (HV) plots in 2021 (62.19 mg kg

-1), suggesting active Cu cycling driven by the dense, shallow root systems and rapid organic matter turnover typical of herbaceous cover. In contrast, unvegetated (UV) plots consistently exhibited the lowest Cu levels, with a minimum of 31.52 mg kg

-1 in 2024. A uniform decline in Cu concentrations across all vegetation types in 2024—most notably in HV plots, which showed a reduction of 10.66 mg kg

-1—may reflect increased leaching susceptibility or intensified uptake during peak vegetative growth.

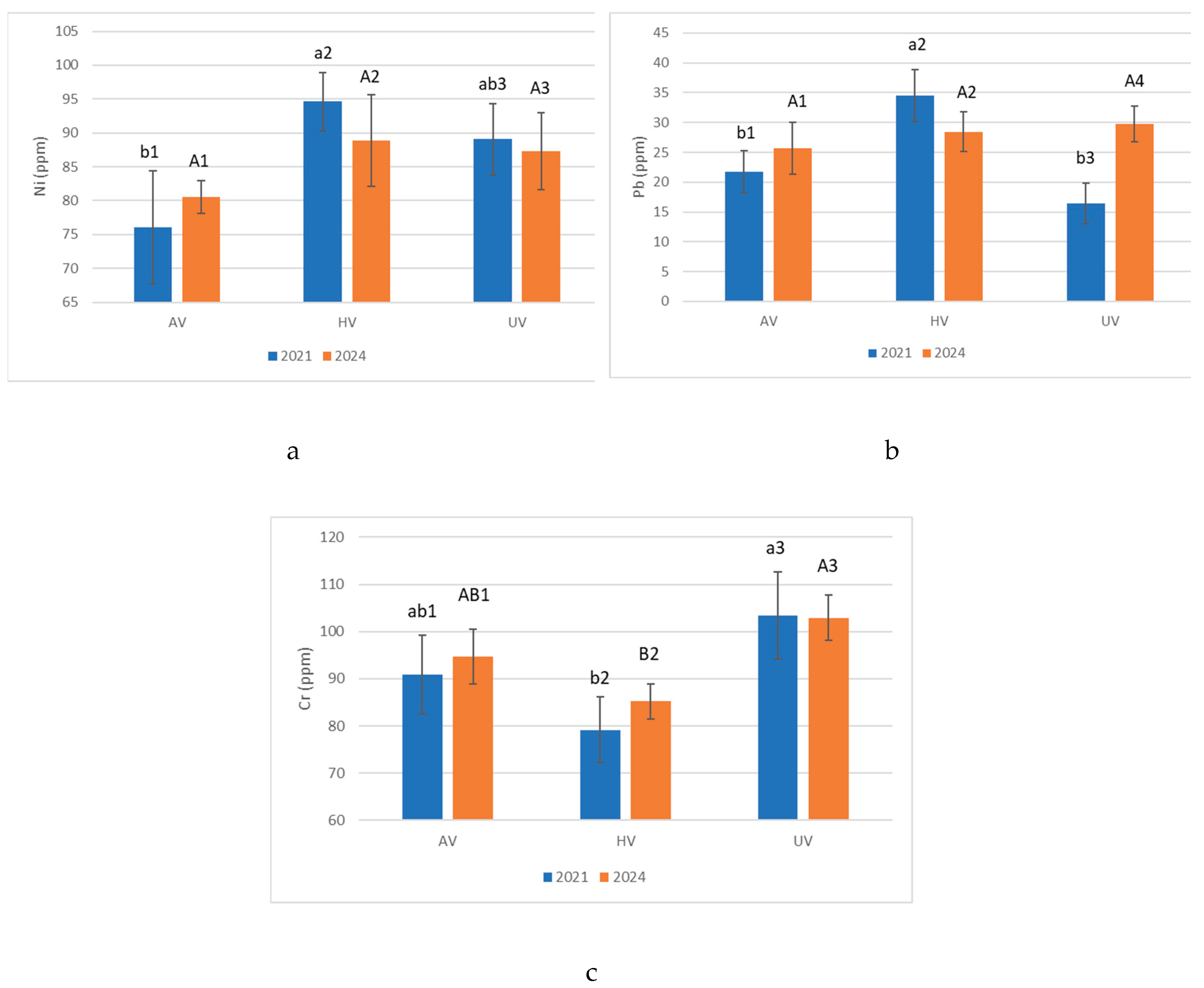

Pseudo-total heavy metal concentrations presented in

Figure 4 showed notable year-to-year variation across vegetation types. Pb levels decreased in HV soils but increased in AV and UV plots from 2021 to 2024. Ni and Cr concentrations generally rose in AV soils, while HV and UV plots exhibited slight declines or stabilization. These shifts suggest vegetation cover influences metal retention and mobility over time.

To contextualize the heavy metal concentrations reported in

Figure 5, soil data from 2021–2024 were compared against European agricultural soil thresholds and guideline values established by Tóth et al. (2016) [

25]. Across all samples, Pb concentrations ranged from 16.47 to 34.56 mg kg

-1, remaining below the EU threshold of 60 mg kg and well under both the lower (200 mg kg

-1) and upper (750 mg kg

-1) guideline values. These findings suggest minimal immediate risk to food safety. However, the elevated Pb levels observed in HV plots—particularly the 2021 peak—may warrant continued monitoring due to potential seasonal accumulation and root-zone interactions. Nickel concentrations, ranging from 76.08 to 94.62 mg kg

-1, exceeded the EU threshold of 50 mg kg

-1 in all variants. Several samples, especially those from HV and UV plots, approached the ecological risk guideline of 100 mg kg

-1. These elevated values raise concerns regarding potential phytotoxicity and the risk of leaching into groundwater, particularly in areas lacking deep-rooted vegetation that could buffer metal mobility. Chromium concentrations varied between 79.17 and 103.37 mg kg

-1, hovering near the EU threshold of 100 mg kg

-1. UV soils slightly exceeded this benchmark in 2024, suggesting enhanced surface accumulation in the absence of vegetative stabilization. Although Cr levels remained below the ecological risk guideline of 200 mg kg

-1, their proximity to critical thresholds—combined with the potential toxicity of hexavalent Cr—calls for cautious interpretation and further investigation.

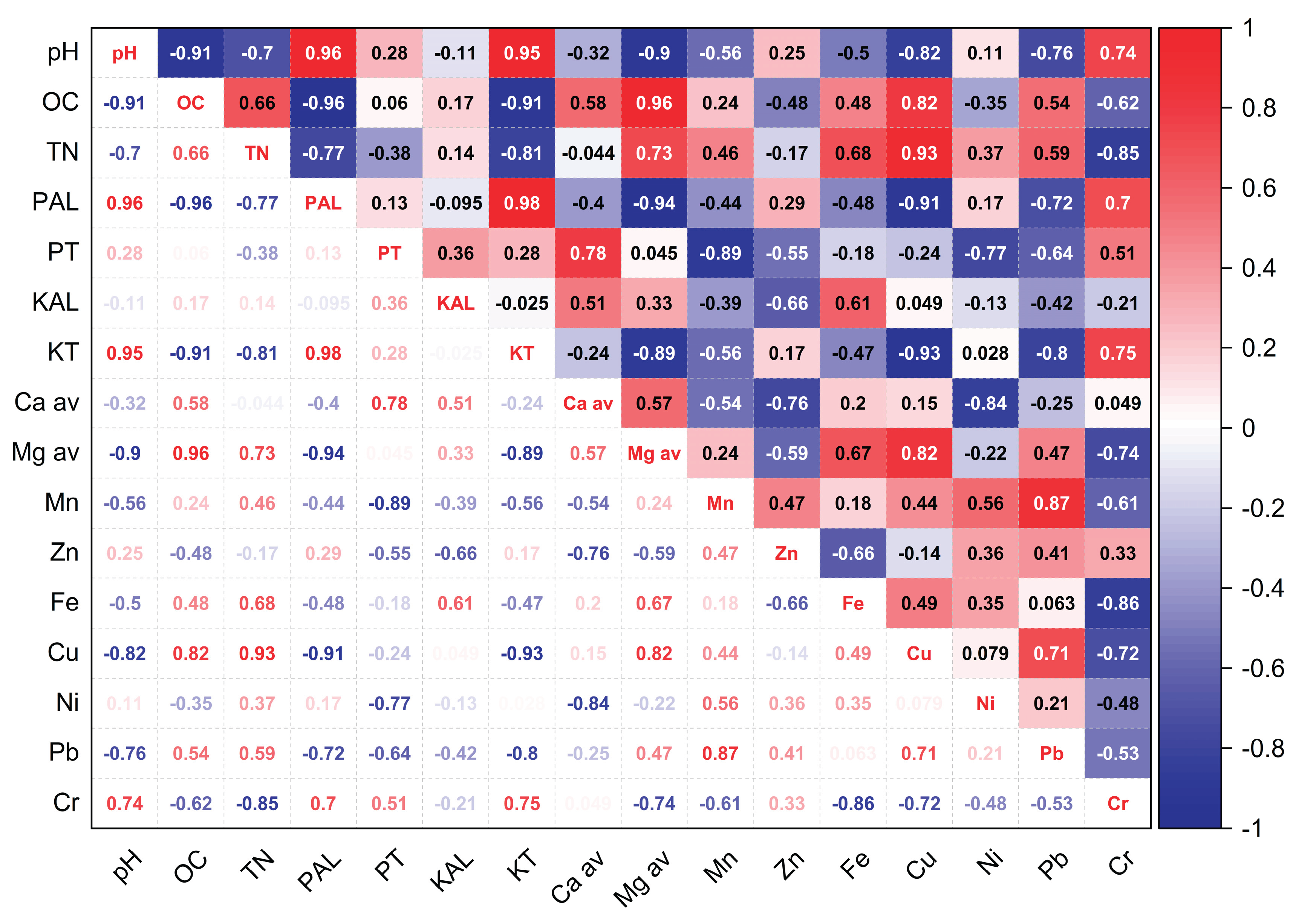

The Pearson correlation analysis revealed consistent patterns across both years, highlighting strong interdependencies among soil chemical properties. In 2021 (

Figure 6), organic carbon (OC) showed strong positive correlations with TN (R = 0.91), P

AL (R = 0.88), and Ca

av (R = 0.85), indicating that nutrient accumulation is closely linked to organic matter enrichment. Soil pH was positively correlated with Ca

av (R = 0.76) and Mg

av (R = 0.72), suggesting that higher pH levels favor the availability of base cations. In contrast, heavy metals such as lead (Pb), nickel (Ni), and chromium (Cr) exhibited moderate to strong negative correlations with pH (R = –0.67, –0.70, and –0.74, respectively), implying increased metal mobility under acidic conditions. Notably, Pb also showed negative associations with OC (R = –0.62) and TN (R = –0.59), reinforcing the antagonistic relationship between heavy metal presence and soil fertility indicators.

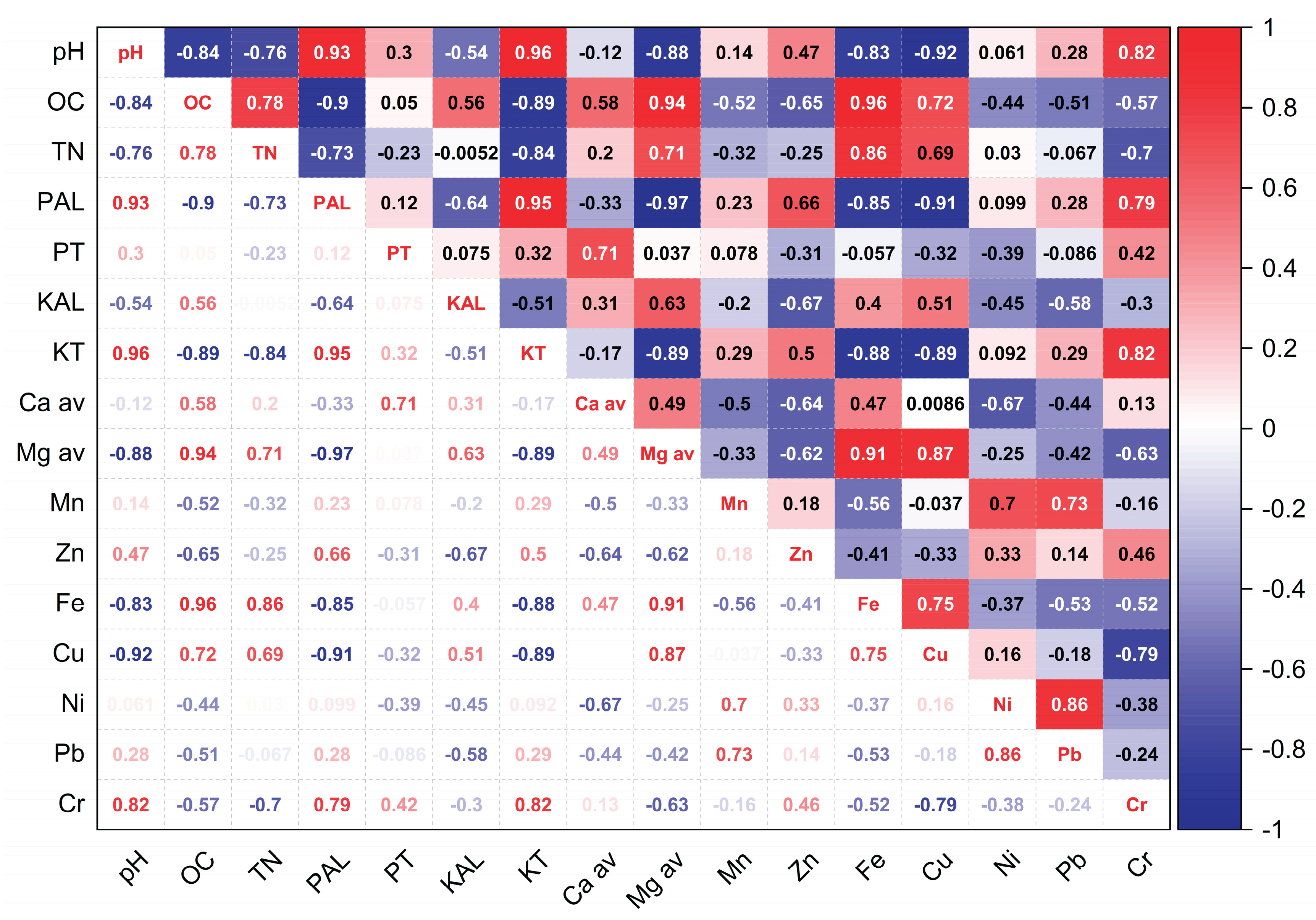

By 2024, Pearson correlation analysis presented in

Figure 7, revealed strong interrelationships among soil chemical parameters, indicating early signs of substrate transformation. Organic carbon (OC) exhibited a robust positive correlation with total nitrogen (TN, R = 0.93), available phosphorus (P

AL, R = 0.89), and exchangeable calcium (Ca

av, R = 0.86), suggesting that organic matter accumulation is tightly linked to nutrient availability. Soil pH showed moderate positive correlations with Ca

av (R = 0.74) and Mg av (R = 0.71), while negatively correlating with P

AL (R = –0.62) and heavy metals such as Fe (R = –0.69), Ni (R = –0.66), and Cr (R = –0.68), indicating that lower pH may enhance metal solubility and limit phosphorus retention. Notably, Pb and Cr displayed negative associations with OC (R = –0.61 and –0.64, respectively), reinforcing the antagonistic relationship between heavy metal presence and organic matter buildup. These early-stage correlations highlight the role of vegetation and organic inputs in improving soil fertility and buffering contaminant mobility in degraded substrates.

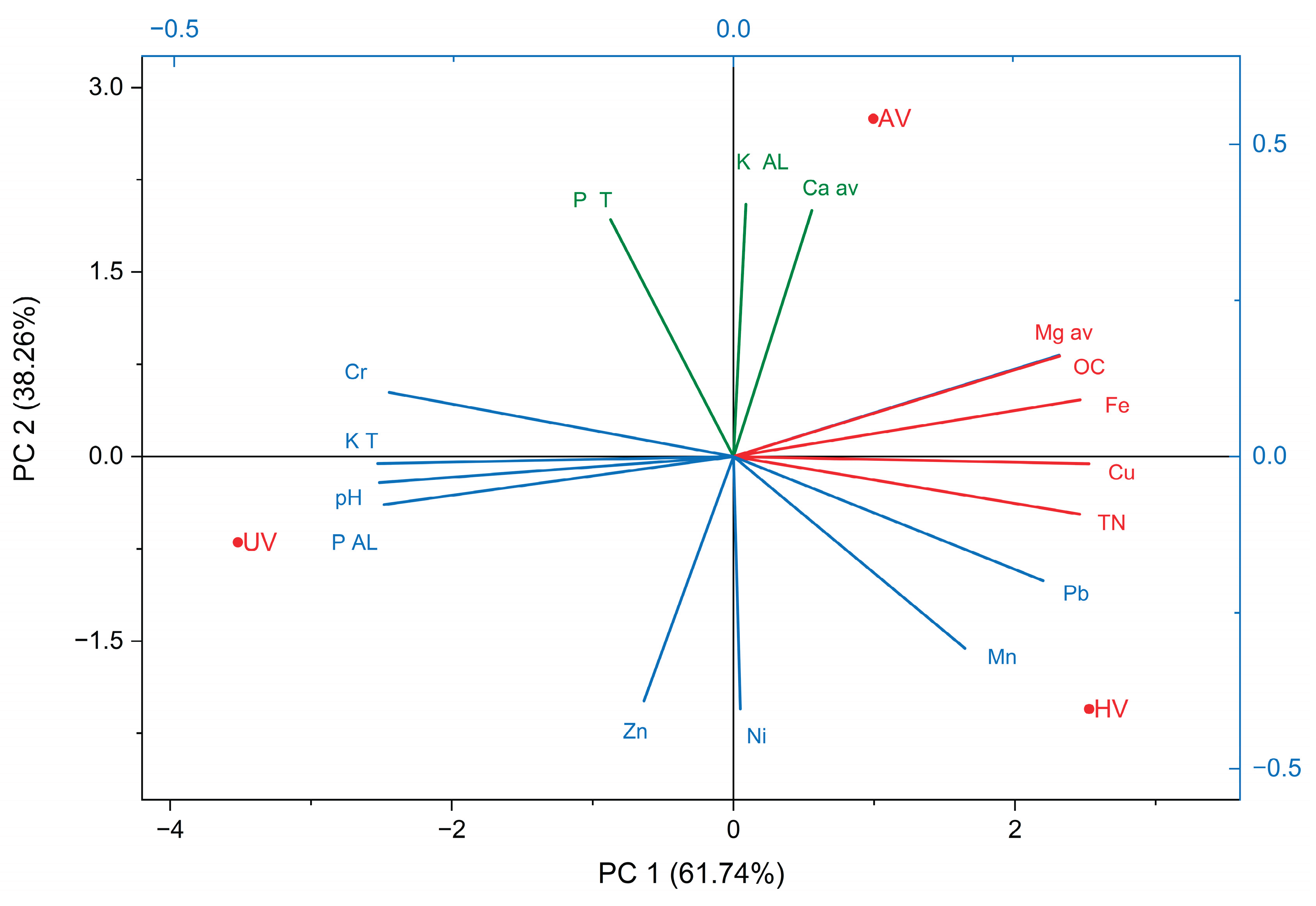

The PCA analysis offers a clear perspective on the complex interactions among soil chemical parameters under varying vegetation covers. The extraction of two principal components, together explaining 100% of the total variance, reflects a well-defined structure within the dataset. In 2021 (

Figure 8), three years after

Robinia pseudoacacia cultivation, PC1 accounted for 61.74% of the total variation and was positively associated with total nitrogen (TN), organic carbon (OC), and pseudototal forms of copper (Cu), iron (Fe), and available magnesium (Mg

av). These variables reflect early signs of biological activity and nutrient enrichment. PC1 also showed strong negative loadings for pH, available phosphorus (P

AL), and total potassium (K

T), which are typically elevated in unvegetated substrates due to limited biological uptake. PC2 explained the remaining 38.26% of the variance and was characterized by positive contributions from total phosphorus (P

T), exchangeable potassium (K

AL), and available calcium (Ca

av), while showing negative loadings for manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and nickel (Ni).

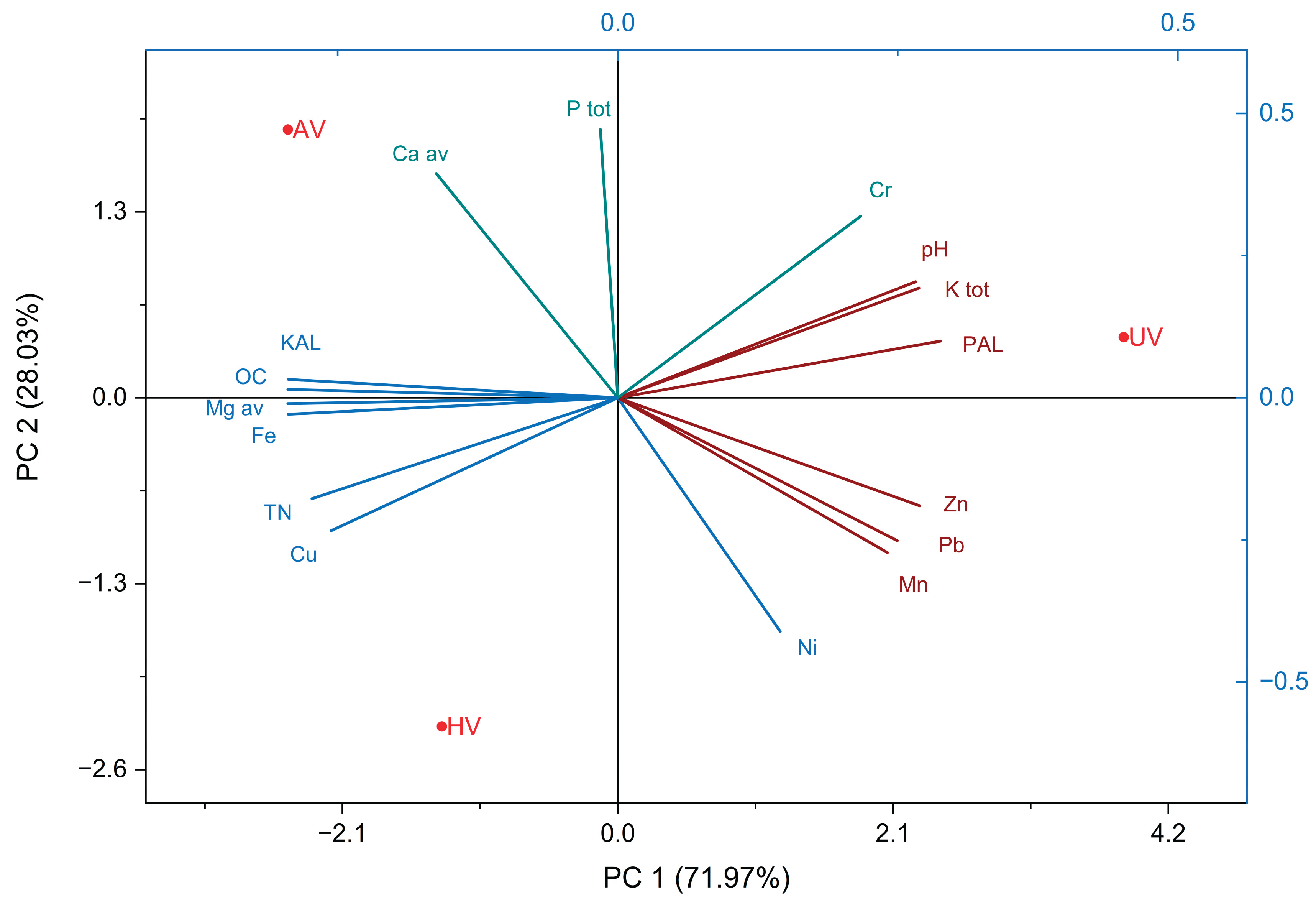

In 2024 (

Figure 9), six years post-cultivation, PCA revealed further divergence among vegetation types. PC1, explaining 71.97% of the total variation, showed strong positive correlations with pH, K

T, and P

AL—parameters predominantly influenced by the UV variant. This suggests that unvegetated plots maintain elevated baseline levels of these elements due to limited biological cycling. Conversely, PC1 exhibited pronounced negative loadings for OC, TN, Mg

av, and Fe and Cu, which are more abundant in vegetated plots due to organic matter input and microbial activity. PC2 accounted for 28.03% of the variance and was positively associated with P

T, Ca

av, and pseudototal chromium (Cr), while negatively correlated with pseudototal nickel (Ni).

4. Discussions

Soil pH remained alkaline across all plots in both 2021 and 2024, largely due to the presence of calcite—a strong buffering mineral within the coal mining waste. Quartz and potassium feldspar, being chemically inert, had minimal impact on pH regulation. Over time, a consistent decline in pH was observed, indicating ongoing biogeochemical changes [

26]. Vegetated plots (arboreal and herbaceous) showed lower pH values than unvegetated ones, highlighting the acidifying effects of biological activity. Herbaceous plots exhibited the most pronounced pH reduction, likely driven by fibrous roots enhancing microbial activity and organic acid production. Despite differences in root structure, both vegetation types contributed to acidification through organic matter turnover, root exudation, and CO₂ release, which forms carbonic acid in soil moisture. In contrast, unvegetated plots maintained higher pH levels, dominated by geochemical buffering in the absence of biological influence [

18].

Vegetation type strongly influenced TN concentrations across plots. Arboreal vegetation (AV) plots recorded the highest TN levels, likely due to stable retention mechanisms such as deeper roots and slower biomass turnover [

27]. Herbaceous vegetation (HV) plots showed elevated TN through rapid litter decomposition and active nutrient cycling. From 2021 to 2024, TN increased across vegetated plots, reflecting early pedogenic processes like organic matter accumulation and microbial colonization [

28,

29]. In contrast, unvegetated (UV) plots maintained low TN levels, constrained by the lack of biological inputs and limited microbial activity, despite mildly alkaline pH conditions [

30,

31].

OC concentrations followed a similar vegetation-driven gradient: highest in HV plots, moderate in AV, and lowest in UV. Herbaceous species enhanced surface carbon through fast decomposition and dense roots, while arboreal vegetation supported long-term stabilization via woody biomass and extensive root systems. UV plots lacked organic inputs and microbial colonization, resulting in persistently low OC levels despite favorable pH [

32]. The upward trend in OC and TN from 2021 to 2024 signals ongoing soil development and aligns with reclamation trajectories reported by Chan et al. (2014) [

33].

C/N ratio patterns further highlight vegetation effects. In 2021, steeper slopes and higher R² values indicated strong vegetation control over organic dynamics. By 2024, reduced slopes and R² suggested increased variability due to complex biotic–abiotic interactions. HV plots consistently showed higher C/N ratios, reflecting rapid carbon input and microbial stimulation [

34], while AV plots contributed to long-term carbon retention. UV plots exhibited the lowest ratios, reinforcing the critical role of vegetation in soil nutrient recovery [

35].

The findings on phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium concentrations in the studied soils highlight the intertwined roles of mineralogical composition and vegetation cover in governing nutrient availability and cycling within reclaimed mining substrates. Vegetation-induced biological processes play a pivotal role in mobilizing nutrients—particularly phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium—whereas the absence of plant cover shifts nutrient dynamics toward mineral-derived persistence and surface accumulation [

36]. Phosphorus behavior varied notably across vegetation types. Arboreal vegetation (AV) plots exhibited the highest levels of bioavailable phosphorus (P

AL) and total P, reflecting intensified microbial activity and organic matter turnover. These biological mechanisms are known to enhance phosphorus solubilization and retention in disturbed soils undergoing reclamation [

37]. Interestingly, unvegetated (WV) plots also showed elevated P

AL concentrations, likely due to limited plant uptake and surface accumulation—patterns previously observed in post-mining environments where phosphorus remains largely unutilized [

6]. The presence of minerals such as biotite may serve as slow-release sources of phosphorus, contributing to long-term fertility potential [

38]. Potassium concentrations peaked in WV soils, particularly in K

T, suggesting ongoing abiotic weathering of potassium feldspar. This supports earlier research indicating that feldspar-rich substrates gradually release potassium in the absence of biological uptake [

39]. In contrast, AV and herbaceous vegetation (HV) plots maintained moderate K levels, consistent with active nutrient cycling facilitated by plant uptake. Biotite, a more reactive mineral than feldspar and abundant in the soil matrix, likely contributes to the exchangeable K pool in vegetated soils [

40]. The elevated K

T in WV soils further confirms the mineral origin of potassium where biological extraction is absent. Available calcium (Ca

av) concentrations were highest in AV soils, likely driven by enhanced calcite dissolution mediated by root exudates and microbial acidification. This aligns with the known buffering capacity of calcite-rich substrates and their role in releasing calcium under biologically active conditions [

6]. In contrast, WV soils exhibited lower Ca

av levels, indicating reduced mineral weathering in the absence of vegetation. These results reinforce the importance of plant cover in accelerating carbonate breakdown and facilitating nutrient mobilization [

41]. Available magnesium (Mg

av)levels were most pronounced in AV and HV soils, reflecting intensified biotite weathering—a mineral that hosts both Mg and K. Vegetation enhances Mg availability through synergistic interactions between roots and soil microbes, as well as through organic matter decomposition [

42]. WV soils, by comparison, showed diminished Mg

av concentrations, consistent with limited biotite degradation and poor nutrient retention. This pattern supports previous findings that magnesium cycling is closely tied to biological activity and organic inputs [

6].

In 2024, microelement concentrations declined in vegetated plots due to sustained plant uptake, enhanced microbial activity, and reduced geogenic input from tailing weathering. Vegetation functions as both a sink and a stabilizer, modulating nutrient availability through root absorption, organic matter turnover, and rhizosphere interactions [

43,

44]. High annual precipitation (~878 mm year

-1) further facilitates leaching and ion mobility, intensifying nutrient cycling in vegetated soils while promoting surface accumulation and erosion in unvegetated (WV) areas. The mineral matrix—dominated by quartz, K-feldspar, calcite, and biotite—offers limited nutrient release. Quartz and feldspar are largely inert, while calcite buffers pH and influences metal solubility. Biotite contributes Fe and Mg under biologically active conditions, especially when weathering is accelerated by root exudates and microbial processes [

45,

46]. Manganese concentrations were highest in HV plots, driven by shallow fibrous roots that intensify organic matter decomposition and microbial mobilization. These conditions promote Mn solubilization and uptake. AV plots showed moderate Mn levels, buffered by deeper root systems that regulate nutrient fluxes. WV plots had the lowest Mn, reflecting minimal biological mobilization and limited microbial activity [

47]. Zinc levels varied spatially and temporally. HV plots maintained elevated Zn due to active cycling and rhizosphere acidification. AV plots consistently recorded lower Zn, likely due to canopy-mediated immobilization and reduced bioavailability. WV plots showed Zn accumulation, attributed to limited biological uptake and surface leaching. Sorption onto quartz and feldspar surfaces may further stabilize Zn in unvegetated substrates [

45,

46]. Iron peaked in AV plots, where deep roots access Fe-bearing minerals like biotite. Organic exudates enhance Fe solubilization and transport, especially in biologically rich soils [

44,

46]. HV plots had slightly lower Fe, possibly due to competitive uptake among dense root networks. WV plots showed minimal Fe retention, constrained by the absence of vegetation and microbial facilitators. Copper was lowest in WV soils, likely due to leaching and immobilization in non-bioavailable forms. AV plots showed intermediate Cu levels, stabilized by root depth and moderated uptake. HV plots recorded the highest Cu concentrations, consistent with rhizosphere acidification and enhanced microbial cycling that increase Cu bioavailability and mobility [

50].

Vegetation cover is a key driver of microelement retention and heavy metal distribution. Herbaceous species (HV) enhanced Mn, Zn, Cu, and Pb concentrations through dense root mats and rapid organic turnover, which stimulate microbial activity and rhizosphere acidification [

43,

51,

52]. Arboreal vegetation (AV) stabilized Fe and reduced Pb and Cr levels via deeper root systems and mineral buffering, limiting erosion and metal redistribution [

53]. In contrast, unvegetated (UV) plots lacked biological uptake, resulting in greater metal mobility and surface accumulation, especially under hydrological stress. From 2021 to 2024, pseudo-total concentrations of Pb, Ni, and Cr increased across all vegetation types, reflecting active geochemical weathering, seasonal variation, and potential anthropogenic inputs. With ~870 mm annual precipitation, leaching and vertical migration are plausible, particularly in UV soils with minimal infiltration resistance. Substrate mineralogy further shaped metal behavior, quartz and K-feldspar, being inert and low in cation exchange capacity, contributed to metal mobility [

54]. In contrast, biotite adsorbs metals via interlayer exchange, and calcite buffers pH and facilitates metal precipitation as carbonates under alkaline conditions—mechanisms that help retain Pb, Ni, and Cr [

55,

56]. Although pseudo-total measurements include both bioavailable and residual fractions, environmental risk remains uncertain without speciation data. Nonetheless, observed concentrations approach or exceed thresholds that may impair plant growth and pose food safety risks through bioaccumulation [

57,

58]. Elevated Ni and Cr levels in HV and UV plots suggest emerging ecological concerns that warrant further investigation.

The comparison of Pearson correlation matrices from 2021 and 2024 underscores the influential role of vegetation and soil chemical dynamics in driving nutrient cycling, while also revealing notable changes in the relationships among soil parameters over time. In unvegetated soils, correlations among nutrients and heavy metals were generally weaker and more erratic, reflecting limited biological activity and poor substrate structure. The emergence of herbaceous vegetation introduced more coherent patterns, particularly among organic carbon, nitrogen, and available macroelements, suggesting early-stage biological stabilization and nutrient cycling.

Robinia pseudoacacia, a nitrogen-fixing species with deeper rooting systems, further intensified positive correlations among organic matter, nutrient availability, and base cations, indicating enhanced soil development and amelioration. Simultaneously, negative associations between pH and heavy metals became more pronounced, implying improved buffering capacity and reduced metal mobility in vegetated plots. These evolving correlation structures underscore the role of vegetation—especially leguminous trees—in accelerating soil functional recovery and mitigating contamination risks on post-mining landscapes [

59].

Principal Component Analyses (PCA) conducted in both 2021 and 2024 consistently underscore the ecological impact of vegetation cover on key soil parameters. While this overarching trend remains evident, the evolution of principal component structures across the two years reveals the dynamic nature of soil–vegetation interactions. In 2021, the PCA captured early-stage differentiation among soil samples based on vegetation type. Unvegetated (UV) plots were distinctly separated from those with spontaneous herbaceous (HV) and cultivated arboreal (AV) cover, indicating that even three years post-intervention, vegetation had begun to influence soil chemistry. The clustering of AV samples suggests that Robinia pseudoacacia was already contributing to soil transformation—likely via litter deposition, root exudation, and microbial stimulation. The biplot further illustrates that the AV variant exerted strong influence over PT, KAL, and Caav, pointing to initial nutrient accumulation under Robinia cover. In contrast, HV plots were associated with elevated total nitrogen (TN) and pseudototal concentrations of Pb and Cu, reflecting the effects of spontaneous colonization. UV plots remained linked to higher pH, PAL, and KT values, consistent with the characteristics of minimally altered waste substrates. By 2024, the PCA reveals a more pronounced separation of AV samples from both UV and HV plots, signifying that Robinia pseudoacacia had markedly transformed the soil environment over six years. The shift in AV cluster positioning suggests cumulative improvements in soil quality—potentially driven by enhanced nutrient cycling, organic matter buildup, and contaminant stabilization. These patterns emphasize the dominant role of AV cover in shaping Caav and PT levels, reflecting sustained nutrient enrichment and soil amelioration under Robinia pseudoacacia. Moreover, the data continue to highlight the contrast between active (AV) and passive (HV) revegetation strategies in steering soil chemical trajectories.