Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Variables Design

2.3. Anthropometric Variables

2.2. Metabolic and Oxidative Parameters

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristic of the University Students

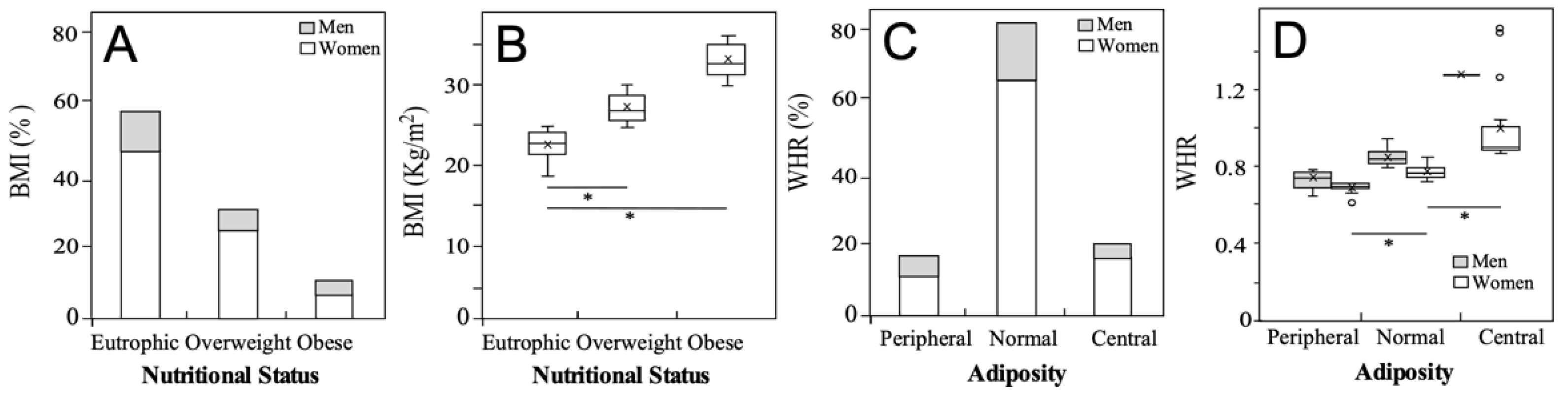

3.2. Nutritional status of the university students

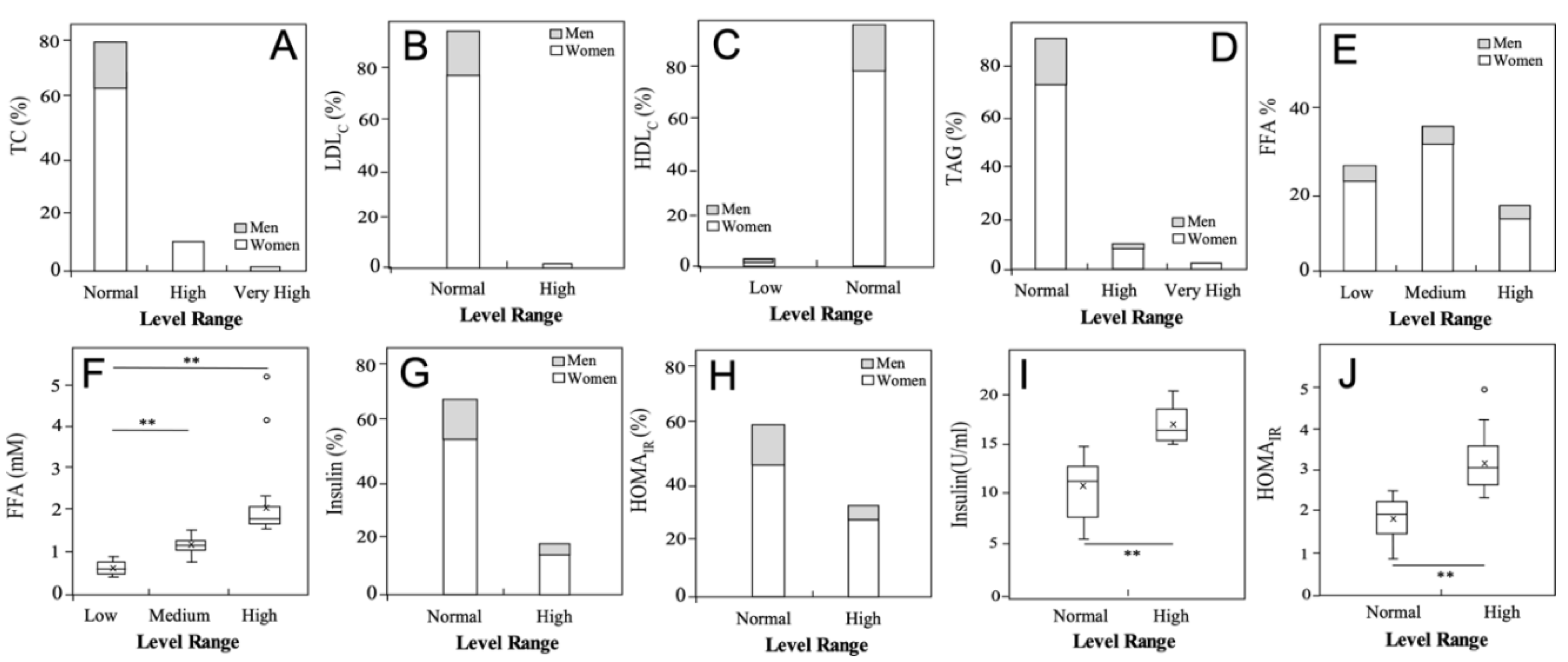

3.3. Metabolic status of the university students

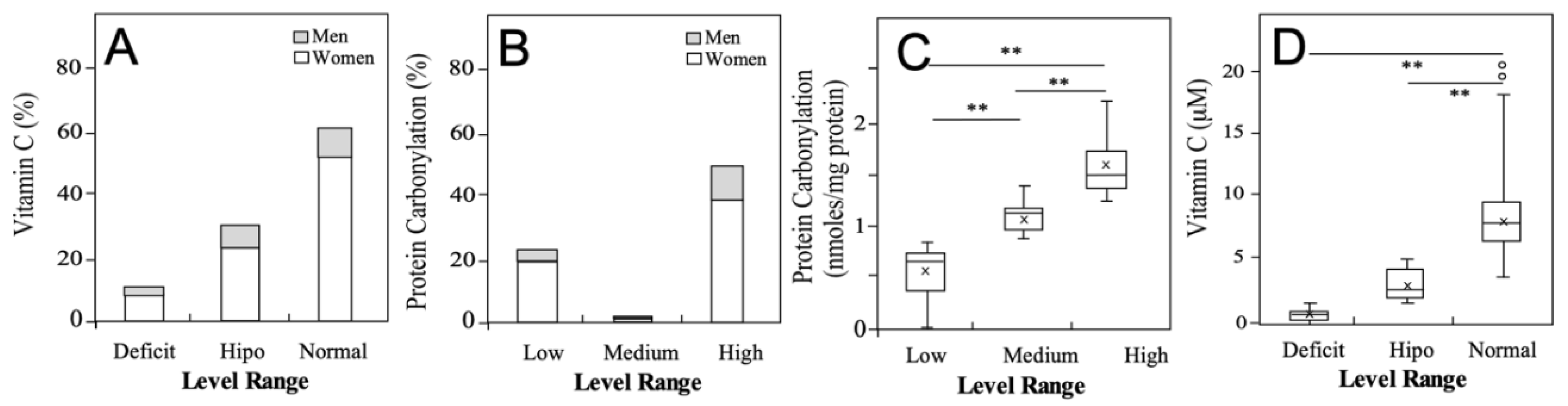

3.3. Oxidative Status of the University Students

3.4. Association between Altered Anthropometric, Metabolic and Ooxidative Parameters in University Students

3.5. Association of Altered Anthropometric, Metabolic and Oxidative Parameters with Unhealthy Behaviors in theUuniversity Students

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Obesidad y sobrepeso. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Phelps, N.H.; Singleton, R.K.; Zhou, B.; Heap, R.A.; Mishra, A.; Bennett, J.E.; Paciorek, C.J.; Lhoste, V.P.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Stevens, G.A.; et al. Worldwide Trends in Underweight and Obesity from 1990 to 2022: A Pooled Analysis of 3663 Population-Representative Studies with 222 Million Children, Adolescents, and Adults. The Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilean National Ministry of Health National Health Survey Report (ENS) 2016–2017 2018.

- Li, X.; Braakhuis, A.; Li, Z.; Roy, R. How Does the University Food Environment Impact Student Dietary Behaviors? A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 840818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas-Lange, J. Sobrepeso y Obesidad En Chile: Consideraciones Para Su Abordaje En Un Contexto de Inequidad Social. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2023, 50, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, L.; Pazos, M.; Molinar-Toribio, E.; Sánchez-Martos, V.; Gallardo, J.M.; Rosa Nogués, M.; Torres, J.L.; Medina, I. Protein Carbonylation Associated to High-Fat, High-Sucrose Diet and Its Metabolic Effects. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis-Morales, C.A.; Perez-Bravo, F.; Ibañes, L.; Sanzana, R.; Hormazabal, E.; Ulloa, N.; Calvo, C.; Bailey, M.E.S.; Gill, J.M.R. Insulin Resistance in Chileans of European and Indigenous Descent: Evidence for an Ethnicity x Environment Interaction. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, S.; Blüher, M.; Hoffmann, R. Plasma Levels of Free Fatty Acids Correlate with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 2661–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241501491 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- WHO Consultation on, Obesity. 1999: Geneva S.; Organization W.H. Obesity : preventing and managing the global epidemic : report of a WHO consultation; World Health Organization, 2000; ISBN 978-92-4-120894-9. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.A.; Lee, A.; Vinson, D.; Seale, J.P. Use of AUDIT-Based Measures to Identify Unhealthy Alcohol Use and Alcohol Dependence in Primary Care: A Validation Study. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37 Suppl 1, E253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacarías, I.; Olivares, S. Alimentación Saludable. In Nutrición en el ciclo vital; Editorial Mediterráneo: Santiago, 2014; pp. 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Mardones, L.; Muñoz, M.; Esparza, J.; Troncoso-Pantoja, C.; Mardones, L.; Muñoz, M.; Esparza, J.; Troncoso-Pantoja, C. Hábitos alimentarios en estudiantes universitarios de la Región de Bío-Bío, Chile, 2017. Perspect. En Nutr. Humana 2021, 23, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedewald, W.T.; Levy, R.I.; Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of the Concentration of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Plasma, Without Use of the Preparative Ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis Model Assessment: Insulin Resistance and ?-Cell Function from Fasting Plasma Glucose and Insulin Concentrations in Man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Handel, E. Rapid Determination of Total Lipids in Mosquitoes. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1985, 1, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for Lipid Peroxides in Animal Tissues by Thiobarbituric Acid Reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido, R.; Bravo, L.; Saura-Calixto, F. Antioxidant Activity of Dietary Polyphenols As Determined by a Modified Ferric Reducing/Antioxidant Power Assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3396–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnettler, B.; Denegrí, M.; Miranda, H.; Sepúlveda, J.; Orellana, L.; Paiva, G.; Grunert, K.G. Hábitos Alimentarios y Bienestar Subjetivo En Estudiantes Universitarios Del Sur de Chile. Nutr. Hosp. 2013, 28, 2221–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Denegri, M.; Hueche, C.; Poblete, H. Life Satisfaction of University Students in Relation to Family and Food in a Developing Country. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Piero, A.; Bassett, N.; Rossi, A.; Sammán, N. [Trends in food consumption of university students]. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 31, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes Narvaez, S.; Canto, M.O. Conocimientos Sobre Alimentación Saludable En Estudiantes de Una Universidad Pública. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2020, 47, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, Y.; Aljohani, N.H.; Salem, G.A.; Ashour, F.M.; Own, S.A.; Alajrafi, N.F. Predictability of the Development of Insulin Resistance Based on the Risk Factors Among Female Medical Students at a Private College in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, V.; Crovetto, M.; Valladares, M.; Oñate, G.; Fernández, M.; Espinoza, V.; Mena, F.; Aguero, S.D.; Vera, V.; Crovetto, M.; et al. Consumo de Frutas, Verduras y Legumbres En Universitarios Chilenos. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2019, 46, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Socarrás, V.; Aguilar Martínez, A. Food habits and health-related behaviors in a university population. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 31, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Salvadó, J.; Díaz-López, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Basora, J.; Fitó, M.; Corella, D.; Serra-Majem, L.; Wärnberg, J.; Romaguera, D.; Estruch, R.; et al. Effect of a Lifestyle Intervention Program With Energy-Restricted Mediterranean Diet and Exercise on Weight Loss and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: One-Year Results of the PREDIMED-Plus Trial. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajardo, D.; Gómez, G.; Carpio-Arias, V.; Landaeta-Díaz, L.; Ríos, I.; Parra, S.; Araneda Flores, J.A.; Morales Illanes, G.R.; Meza, E.; Núñez, B.; et al. Association between Low Dairy Consumption and Determinants of Health in Latin American University Students: A Multicenter Study. Nutr. Hosp. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfossi Lubascher, M.; Hiche Schwarzhaupt, F.; Nacrur Pinto, M.J. Relación Entre Circunferencia de Cintura, Parámetros Metabólicos y Presión Arterial En Universitarios de Primer Año de La Facultad de Medicina de La Universidad Del Desarrollo. Rev. Confluencia 2021, 4, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Cervantes, M.I.; Castillo-Hernández, J.R.; Martel-Gallegos, M.G.; Maldonado-Cervantes, E.; Patiño-Marín, N.; García-Rangel, M.; Torres-Rodríguez, L. La Circunferencia de La Cintura Es La Única Variable Antropométrica Que Predice El HOMA-IR: Estudio de Una Cohorte de Mujeres Jóvenes. REVMEDUAS 2022, 12, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Rodríguez, J.; Moncada Espinal, O.M.; Domínguez, Y.A. Utilidad Del Índice Cintura/Cadera En La Detección Del Riesgo Cardiometabólico En Individuos Sobrepesos y Obesos. Rev. Cuba. Endocrinol. 2018, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Caceres, M.; Teran, C.G.; Rodriguez, S.; Medina, M. Prevalence of Insulin Resistance and Its Association with Metabolic Syndrome Criteria among Bolivian Children and Adolescents with Obesity. BMC Pediatr. 2008, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Farai, H.H.; Al-Aboodi, I.; Al-Sawafi, A.; Al-Busaidi, N.; Woodhouse, N. Insulin Resistance and Its Correlation with Risk Factors for Developing Diabetes Mellitus in 100 Omani Medical Students. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2014, 14, e393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Bai, H.; Li, Z.; Fan, M.; Li, G.; Chen, L. Association of the Oxidative Balance Score with Obesity and Body Composition among Young and Middle-Aged Adults. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1373709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, A.I.S.; Blindauer, C.A.; Stewart, A.J. Changes in Plasma Free Fatty Acids Associated with Type-2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Larsson, S.C. An Atlas on Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes: A Wide-Angled Mendelian Randomisation Study. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 2359–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, G.; Guillen-Grima, F.; Muñoz, S.; Belmar, C.; Schifferli, I.; Muñoz, A.; Soto, A. Factores de Riesgo Cardiovascular En Universitarios de Primer y Tercer Año. Rev. Médica Chile 2017, 145, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermúdez-Cardona, J.; Velásquez-Rodríguez, C. Profile of Free Fatty Acids and Fractions of Phospholipids, Cholesterol Esters and Triglycerides in Serum of Obese Youth with and without Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2016, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokotou, M.G.; Mantzourani, C.; Batsika, C. S Lipidomics Analysis of Free Fatty Acids in Human Plasma of Healthy and Diabetic Subjects by Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS). Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.C. Plasma Free Fatty Acid Concentration as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Metabolic Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, N.; Fried, J.C.; Kim, C.; Sidhom, E.-H.; Brown, M.R.; Marshall, J.L.; Arevalo, C.; Dvela-Levitt, M.; Kost-Alimova, M.; Sieber, J.; et al. FALCON Systematically Interrogates Free Fatty Acid Biology and Identifies a Novel Mediator of Lipotoxicity. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 887–905.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, K.N.; Cruzat, V.F.; Carlessi, R.; De Bittencourt, P.I.H.; Newsholme, P. Molecular Events Linking Oxidative Stress and Inflammation to Insulin Resistance and β -Cell Dysfunction. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine; Oxford University Press, 2015; ISBN 978-0-19-871748-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Deng, M.; Wu, J.; Luo, L.; Chen, R.; Liu, F.; Nie, J.; Tao, F.; Li, Q.; Luo, X.; et al. Associations of Oxidative Balance Score with Total Abdominal Fat Mass and Visceral Adipose Tissue Mass Percentages among Young and Middle-Aged Adults: Findings from NHANES 2011–2018. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1306428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Bai, H.; Li, Z.; Fan, M.; Li, G.; Chen, L. Association of the Oxidative Balance Score with Obesity and Body Composition among Young and Middle-Aged Adults. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P.; Melnyk, S.; Bennuri, S.C.; Delhey, L.; Reis, A.; Moura, G.R.; Børsheim, E.; Rose, S.; Carvalho, E. Redox Imbalance and Methylation Disturbances in Early Childhood Obesity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 2207125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choromańska, B.; Myśliwiec, P.; Łuba, M.; Wojskowicz, P.; Dadan, J.; Myśliwiec, H.; Choromańska, K.; Zalewska, A.; Maciejczyk, M. A Longitudinal Study of the Antioxidant Barrier and Oxidative Stress in Morbidly Obese Patients after Bariatric Surgery. Does the Metabolic Syndrome Affect the Redox Homeostasis of Obese People? J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Lima, S.M.; Almondes, K.G. de S.; Clímaco Cruz, K.J.; Aguiar, H.D. de S.P.; Simplício Revoredo, C.M.; Slater, B.; Silva Morais, J.B.; Marreiro, D. do N.; Nogueira, N. do N. Consumption of Nutrients with Antioxidant Action and Its Relationship with Lipid Profile and Oxidative Stress in Student Users of a University Restaurant. Nutr. Hosp. 2017, 34, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.-L.; Tsao, C.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C. Vitamin C Attenuates Predisposition to High-Fat Diet-Induced Metabolic Dysregulation in GLUT10-Deficient Mouse Model. Genes Nutr. 2022, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Wahab, Y.; O’Harte, F.; Mooney, M.; Barnett, C.; Flatt, P. Vitamin C Supplementation Decreases Insulin Glycation and Improves Glucose Homeostasis in Obese Hyperglycemic (Ob/Ob) Mice. Metabolism 2002, 51, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshawarz, A.; Joehanes, R.; Ma, J.; Lee, G.Y.; Costeira, R.; Tsai, P.-C.; Masachs, O.M.; Bell, J.T.; Wilson, R.; Thorand, B.; et al. Dietary and Supplemental Intake of Vitamins C and E Is Associated with Altered DNA Methylation in an Epigenome-Wide Association Study Meta-Analysis. Epigenetics 2023, 18, 2211361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Orgado, J.; Martínez-Vega, M.; Silva, L.; Romero, A.; De Hoz-Rivera, M.; Villa, M.; Del Pozo, A. Protein Carbonylation as a Biomarker of Oxidative Stress and a Therapeutic Target in Neonatal Brain Damage. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollineni, R.C.; Fedorova, M.; Blüher, M.; Hoffmann, R. Carbonylated Plasma Proteins as Potential Biomarkers of Obesity Induced Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 5081–5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madian, A.G.; Regnier, F.E. Profiling Carbonylated Proteins in Human Plasma. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 1330–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Ruiz, M.C.; Soler-Vázquez, M.C.; Díaz-Ruiz, A.; Peinado, J.R.; Nieto Calonge, A.; Sánchez-Ceinos, J.; Tercero-Alcázar, C.; López-Alcalá, J.; Rangel-Zuñiga, O.A.; Membrives, A.; et al. Influence of Protein Carbonylation on Human Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total | Men | Women |

| N | 190 | 49 | 142 |

| Age (years) | 19.9±1.6 | 19.9±1.6 | 20.0±1.7 |

| Residence (%) | |||

| In the Commune | 48.7 | 52,1 | 47.9 |

| <45 Km | 49.2 | 47.9 | 50.0 |

| >45 Km | 2.1 | 0 | 2.1 |

| Family Income Quintile (USD per cápita, %) | |||

| 1 (< 80.00) | 2.2 | 0 | 2.8 |

| 2 (80.00 to 133.00) | 10.1 | 22.2 | 7.0 |

| 3 (133.00 to 200.00) | 20.2 | 16.7 | 21.1 |

| 4 (200.00 to 380.00) | 23.6 | 22.2 | 23.4 |

| 5 (> 380.00) | 43.8 | 38.9 | 45.1 |

| Years of University (%) | |||

| 1 | 61.8 | 89.7 | 58.7 |

| 2 | 26.9 | 5.1 | 27.5 |

| 3 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 8.7 |

| 4 | 3.8 | 0 | 5.1 |

| Carreer (%) | |||

| Kinesiology | 13.8 | 26.1 | 27.5 |

| Medical Technology | 4.7 | 6.5 | 3.1 |

| Medicine | 31.7 | 45.6 | 37.2 |

| Nursing | 8.4 | 8.7 | 8.4 |

| Nutrition and Dietetics | 41.9 | 19.5 | 37.2 |

| Behaviors (%) | |||

| Healthy | 39.9 | 30.6 | 43.3 |

| Moderately healthy | 44.3 | 38.8 | 46.3 |

| Unhealthy | 15.8 | 30.6 | 10.4 |

| Tobacco Consumption (%) | |||

| Never | 95.0 | 89.7 | 96.7 |

| Moderate | 4.2 | 3.4 | 5.5 |

| Frecuent | 1.7 | 3.4 | 2.2 |

| Alcohol Consumption (%) | |||

| Never | 34.1 | 31.0 | 35.2 |

| <2 at month | 34.1 | 37.9 | 33.0 |

| 2-4 at month | 21.7 | 27.0 | 19.8 |

| Weekly | 6.7 | 3.4 | 7.7 |

| 2-4 at week | 3.3 | 0.0 | 4.3 |

| Variable1 | Glycemia | Insulin | HOMAIR |

| BMI | 0.292 | <0.01* | <0.01* |

| WHR | 0.325 | 0.857 | 0.590 |

| TC | 0.651 | 0.189 | 0.323 |

| LDLc | 0.985 | 0.545 | 0.560 |

| HDLc | 0.324 | 0.124 | 0.314 |

| TAG | 0.927 | <0.01* | 0.002# |

| FFA | 0.454 | <0.01* | <0.01* |

| Vitamin C | 0.302 | 0.968 | 0.554 |

| PC | 0.926 | 0.270 | 0.291 |

| TBARS | 0.308 | 0.009# | 0.006# |

| Variable1 | TC | LDLc | HDLc | TAG | FFA |

| BMI | 0.621 | 0.433 | 0.529 | 0.011# | 0.011# |

| WHR | 0.244 | 0.078 | 0.440 | 0.637 | 0.543 |

| Vit C | 0.131 | 0.319 | 0.747 | 0.069 | 0.087 |

| PC | 0.814 | 0.826 | 0.837 | 0.495 | 0.003# |

| TBARS | 0.171 | 0.693 | 0.026#& | 0.871 | 0.006#& |

| Variable1 | BMI | Insulin | HOMAIR | FAA | VitC | PC |

| Age | 0.726 | 0.663 | 0.371 | 0.660 | 0.537 | 0.646 |

| Residence | 0.039# | 0.707 | 0.088 | 0.523 | 0.326 | 0.237 |

| Family Income | 0.218 | 0.874 | 0.760 | 0.358 | 0.531 | 0.688 |

| Years in university | 0.129 | 0.707 | 0.459 | 0.576 | 0.265 | 0.733 |

| Healthy score | 0.508 | 0.744 | 0.418 | 0.267 | 0.687 | 0.416 |

| >2 vegetables/day | 0.407 | 0.633 | 0.841 | 0.403 | 0.021# | 0.902 |

| >3 fruits /day | 0.710 | 0.758 | 0.307 | 0.824 | 0.361 | 0.421 |

| >2 dairy food portion/day | 0.459 | 0.828 | 0.732 | 0.794 | 0.315 | 0.256 |

| >3 cup of water/day | 0.552 | 0.292 | 0.456 | 0.227 | 0.463 | 0.399 |

| <3 pieces of bread/day | 0.787 | 0.408 | 0.908 | 0.049# | 0.655 | 0.589 |

| >3 legumes portion/week | 0.978 | 0.379 | 0.978 | 0.480 | 0.523 | 0.832 |

| >1 fish portion/week | 0.758 | 0.791 | 0.574 | 0.338 | 0.159 | 0.034# |

| >1 chicken portion /week | 0.349 | 0.188 | 0.220 | 0.703 | 0.114 | 0.585 |

| eat skimmed dairy foods | 0.550 | 0.448 | 0.694 | 0.544 | 0.513 | 0.442 |

| eat not-sweet foods | 0.085 | 0.011# | <0.01* | 0.125 | 0.617 | 0.933 |

| Avoid sweet foods | 0.385 | 0.085 | 0.045# | 0.338 | 0.745 | 0.871 |

| Avoid sausages | 0.365 | 0.704 | 0.730 | 0.533 | 0.436 | 0.064 |

| Take breakfast /lunch | 0.289 | 0.398 | 0.202 | 0.282 | 0.301 | 0.289 |

| Check food labels | 0.407 | 0.570 | 0.409 | 0.246 | 0.653 | 0.745 |

| Cheek well, eat slow | 0.015# | 0.135 | 0.335 | 0.457 | 0.603 | 0.491 |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.032# | 0.212 | 0.180 | 0.725 | 0.376 | 0.679 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).