Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

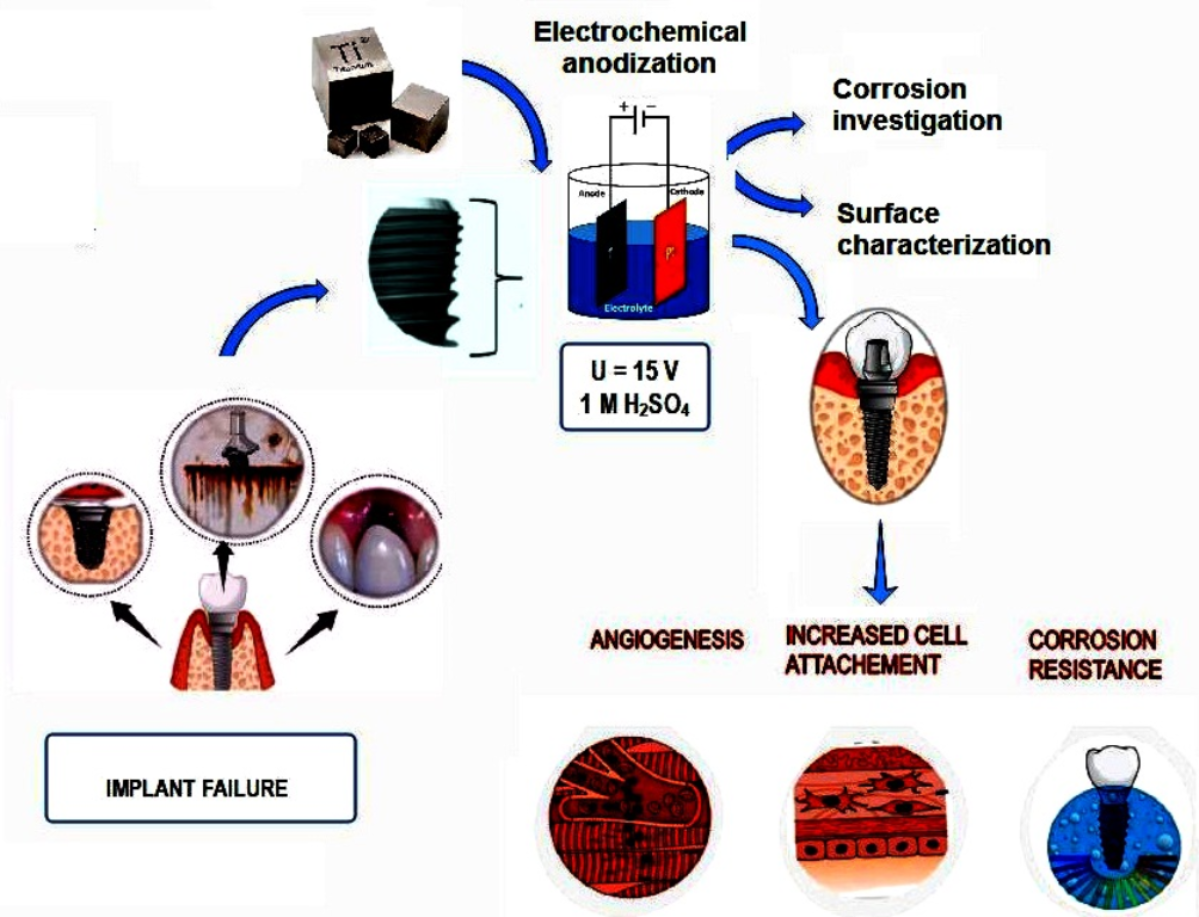

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Anodization and Characterization of Oxidized Titanium

2.1.1. Anodization

2.1.2. Color Measurements

2.1.3. SEM and EDS Characterization

2.1.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Measurements

2.1.4. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Measurements

2.2. Corrosion Measurements

2.3. Biocompatibility

2.3.1. Mitochondrial Activity Assay (MTT Assay)

2.3.2. Gene Expression

2.3.3. Contact Angle Measurements

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Anodization and Characterization of Oxidized Titanium

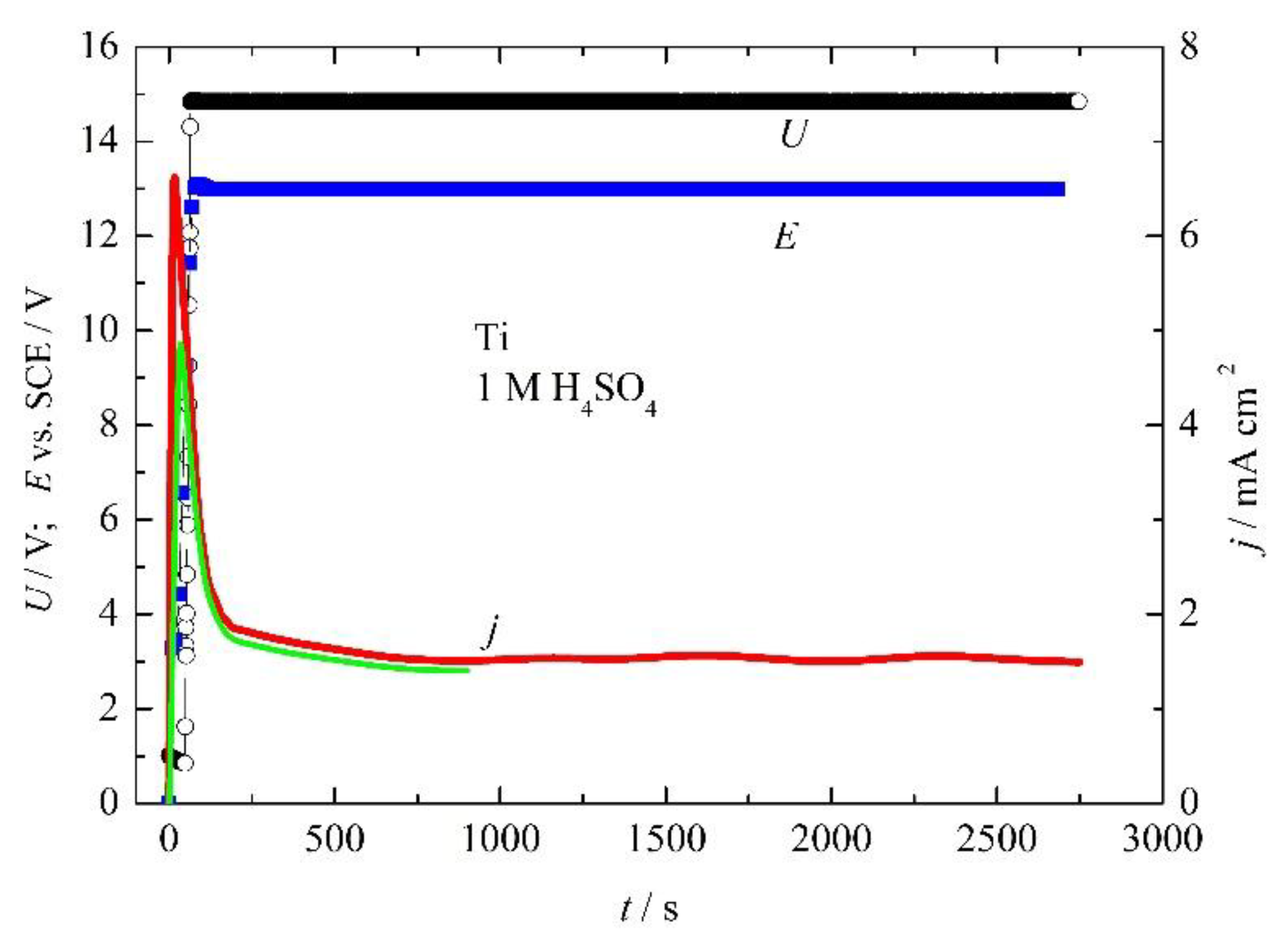

3.1.1. Titanium Anodization

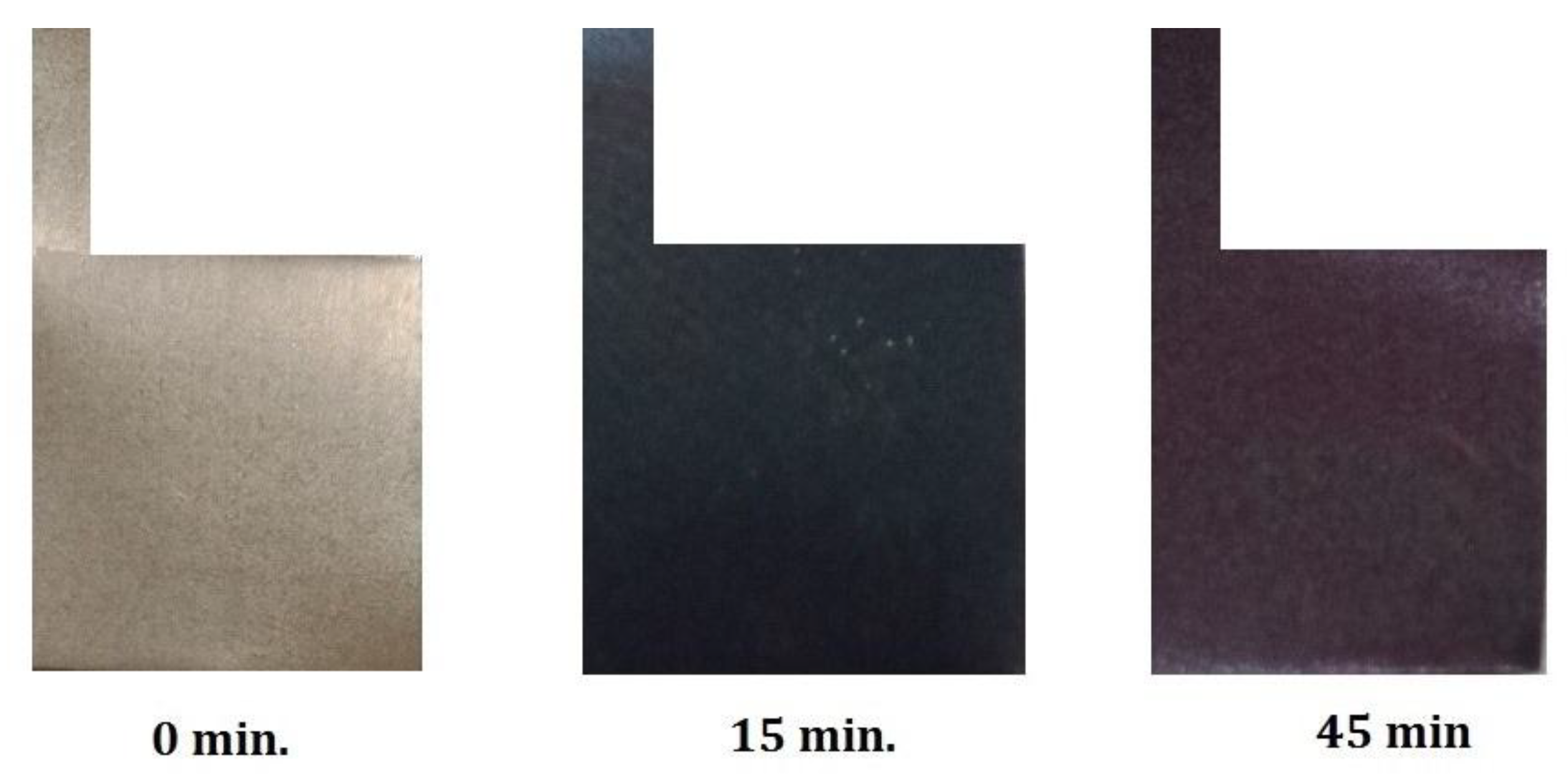

3.1.2. Color Measurements

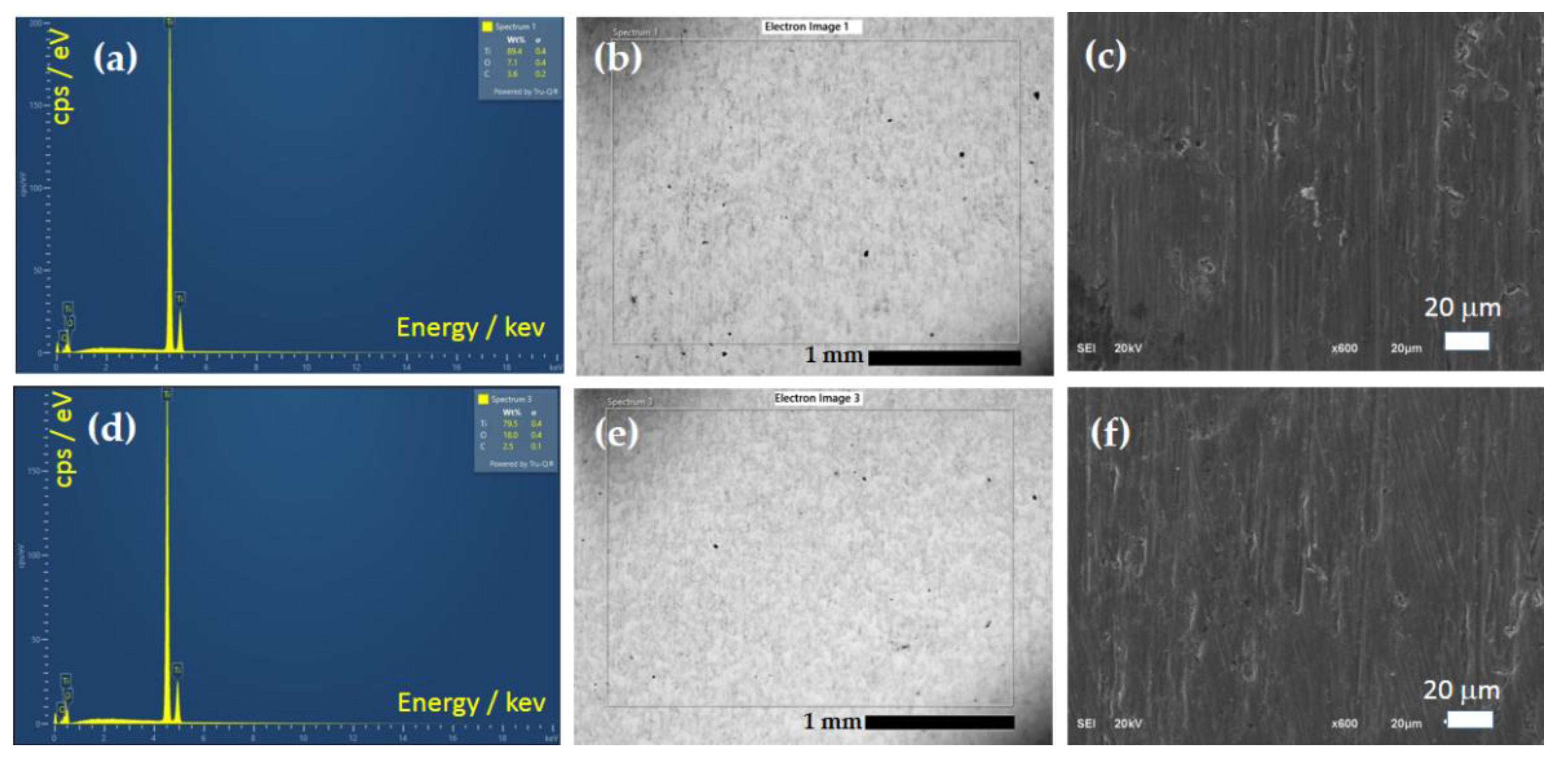

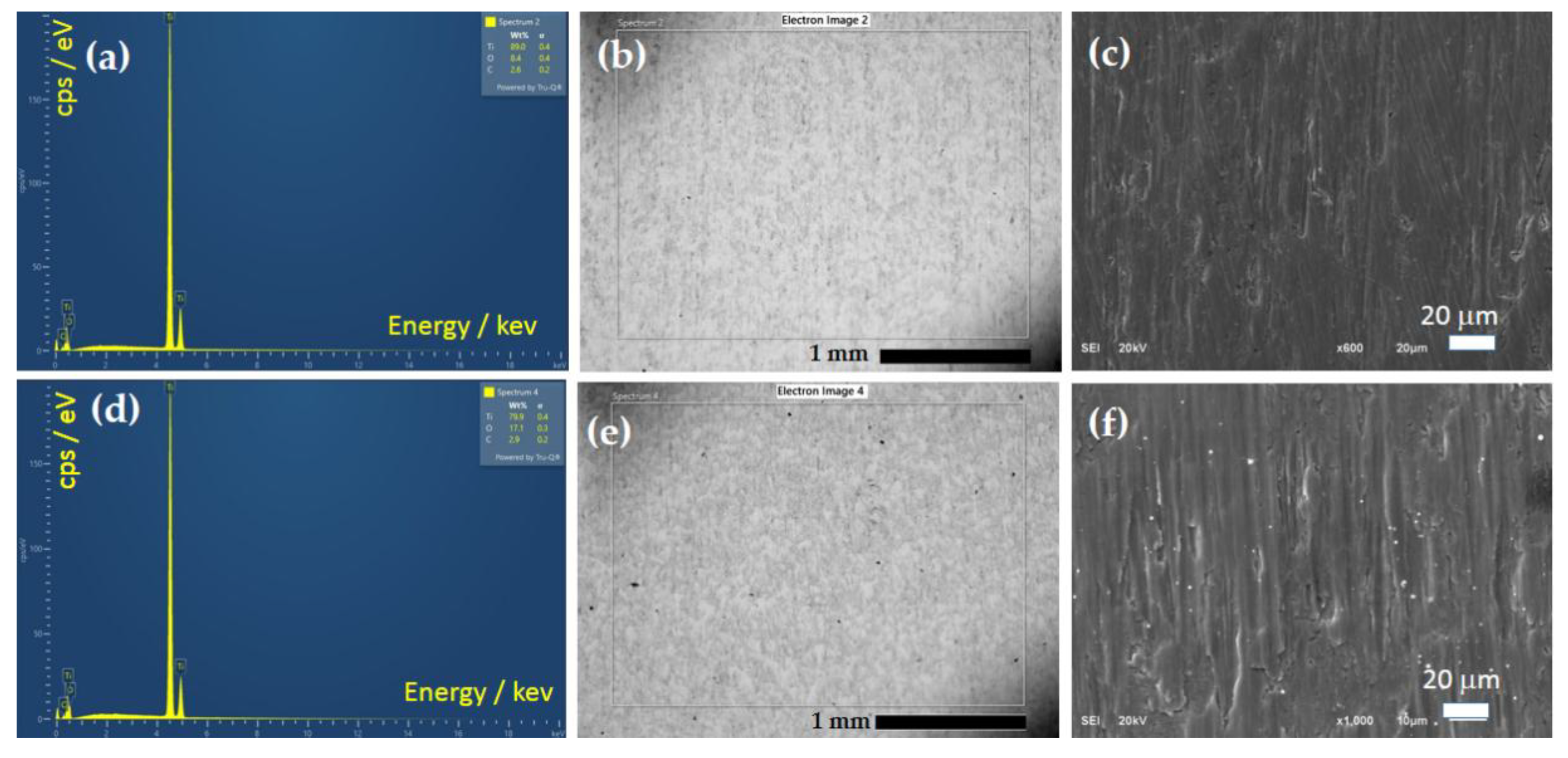

3.1.3. EDS and SEM Analysis

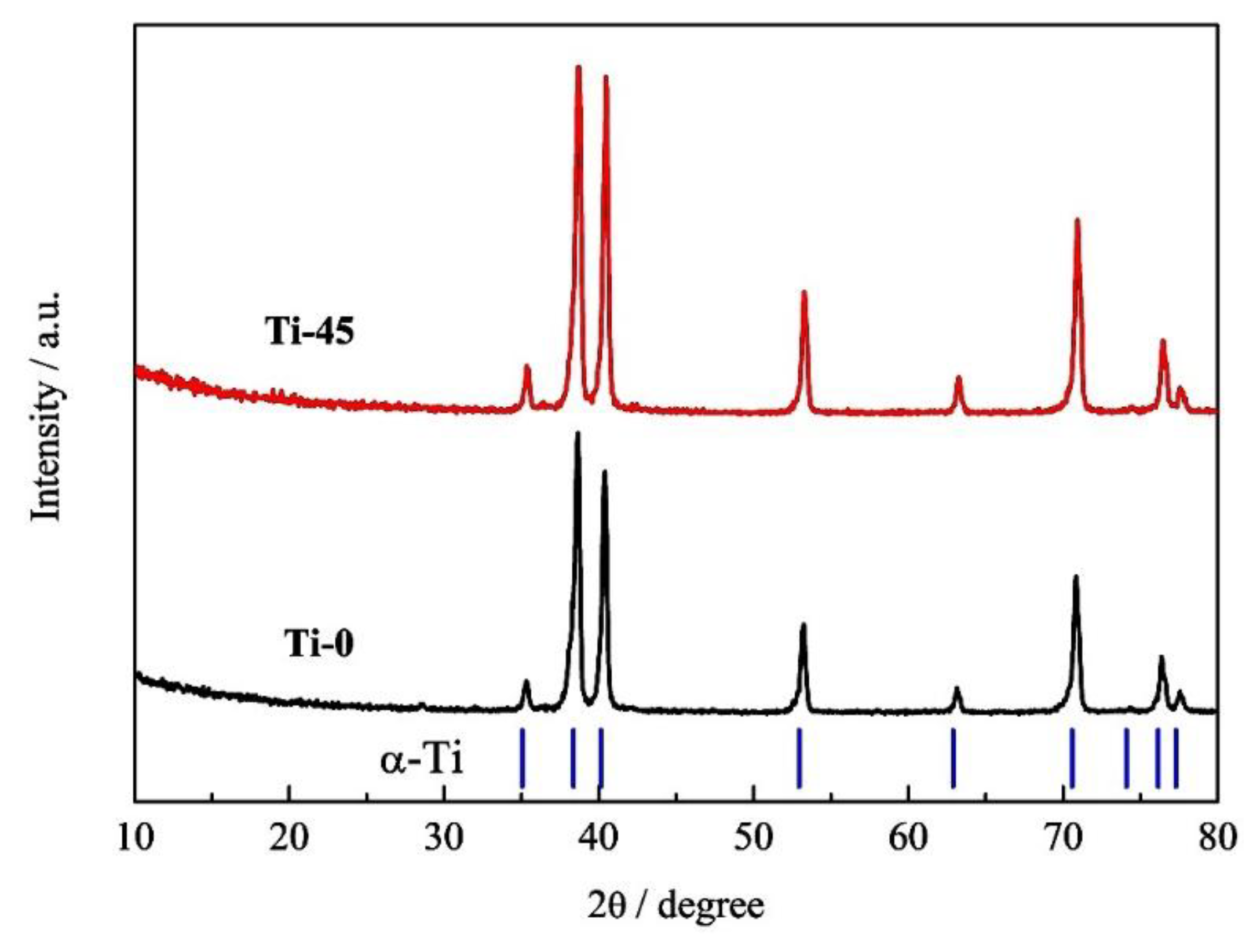

3.1.4. XRD Analysis

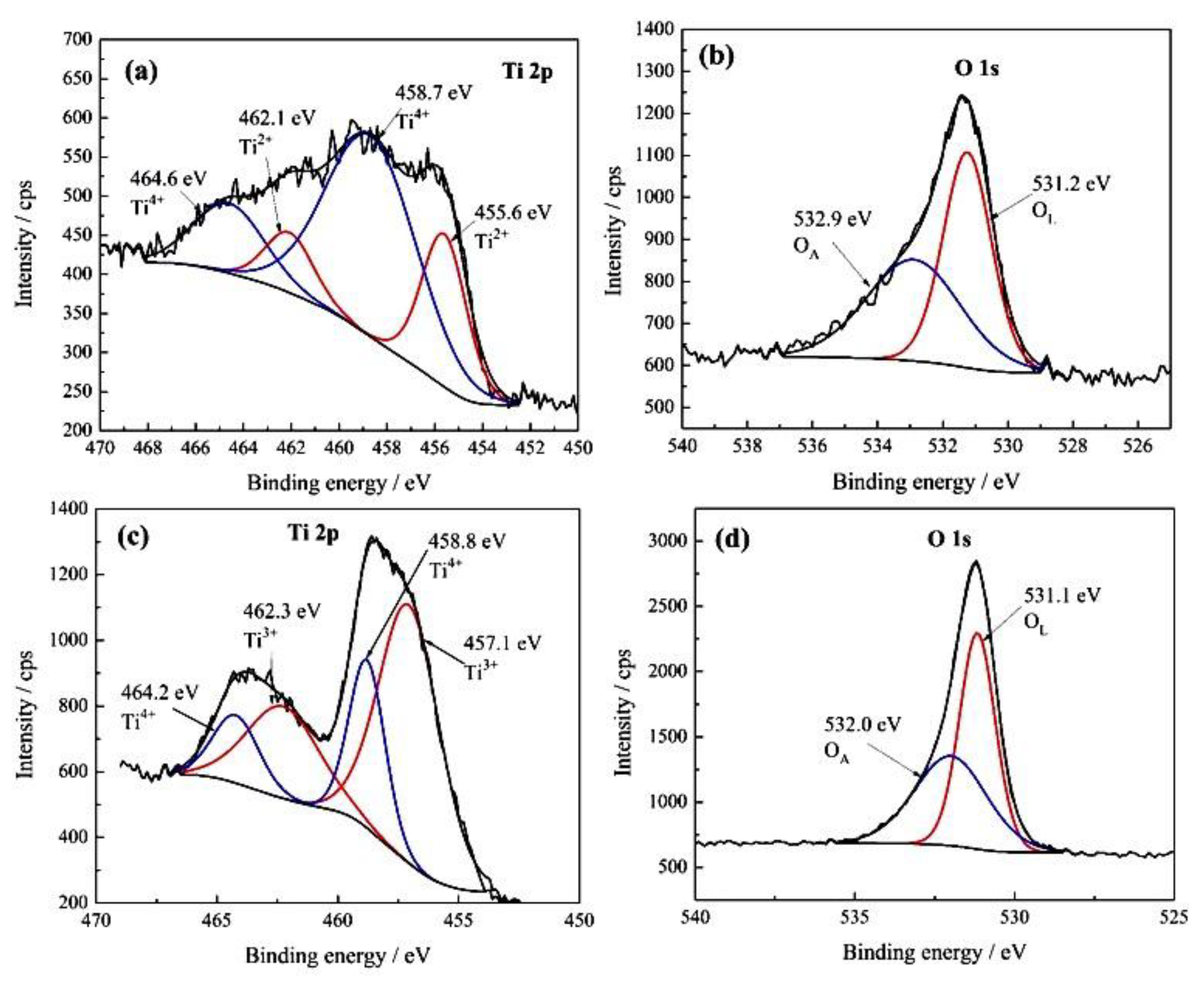

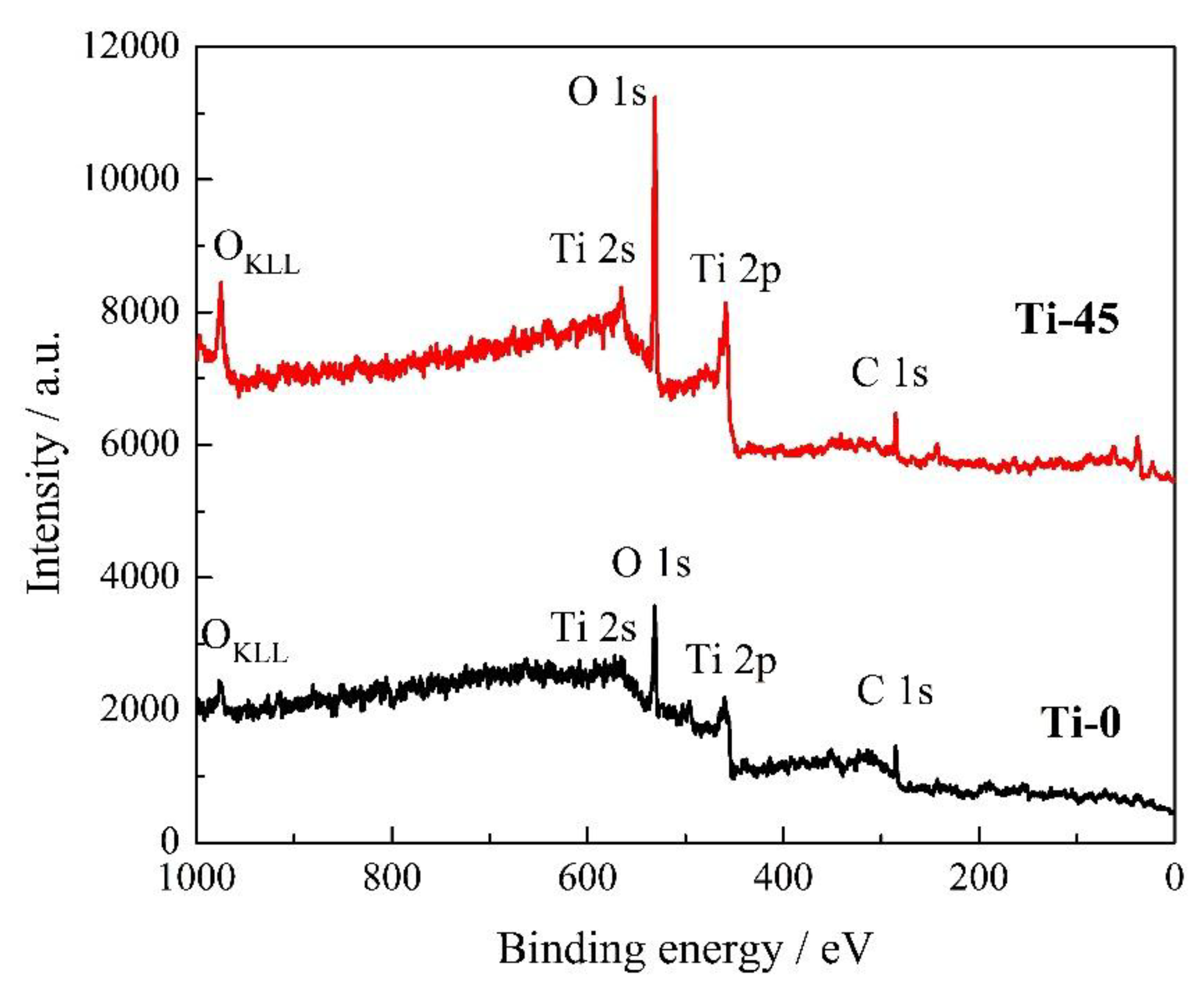

3.1.5. XPS Analysis

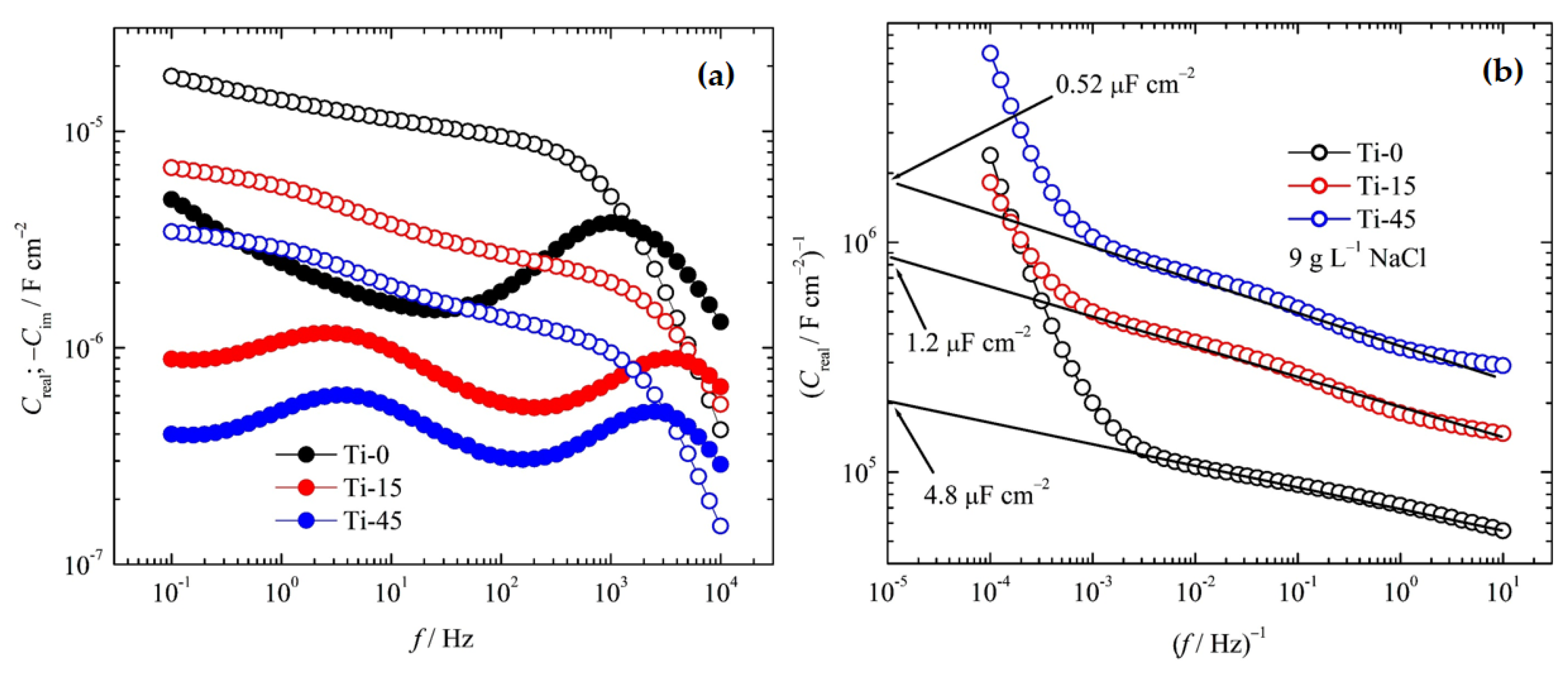

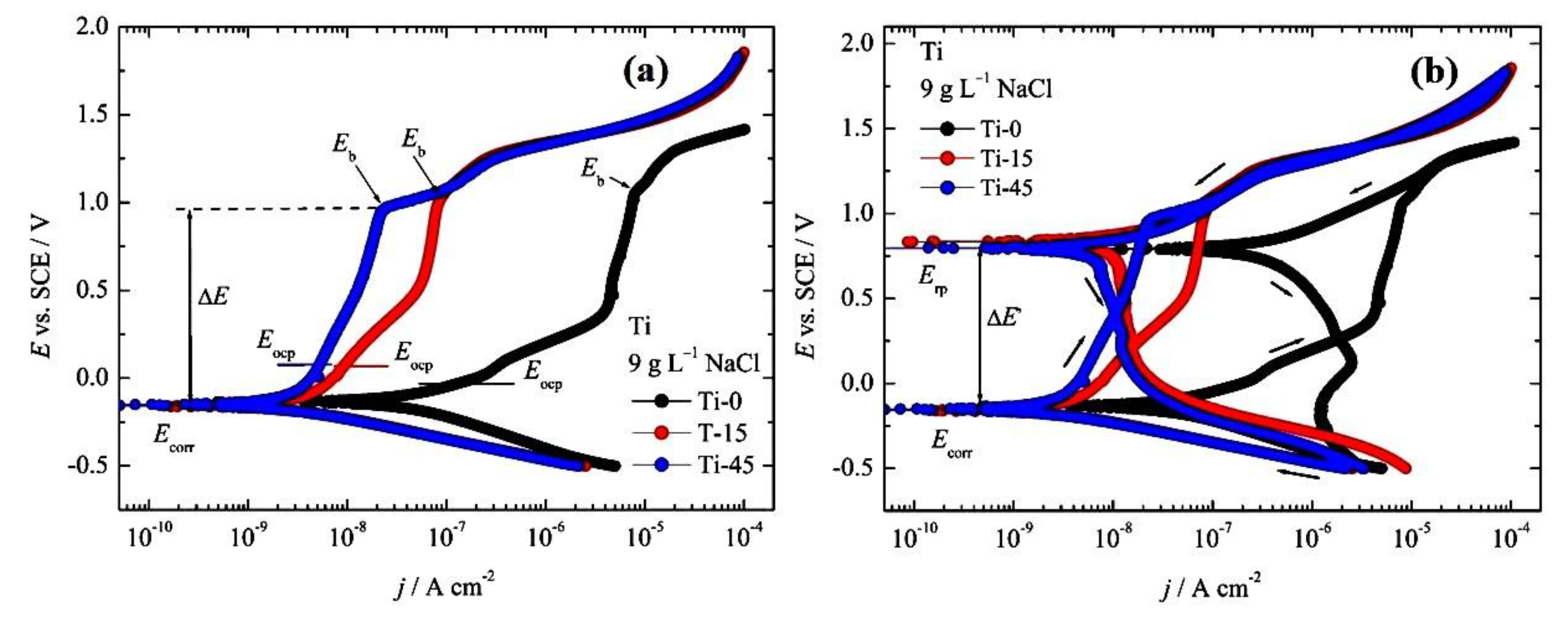

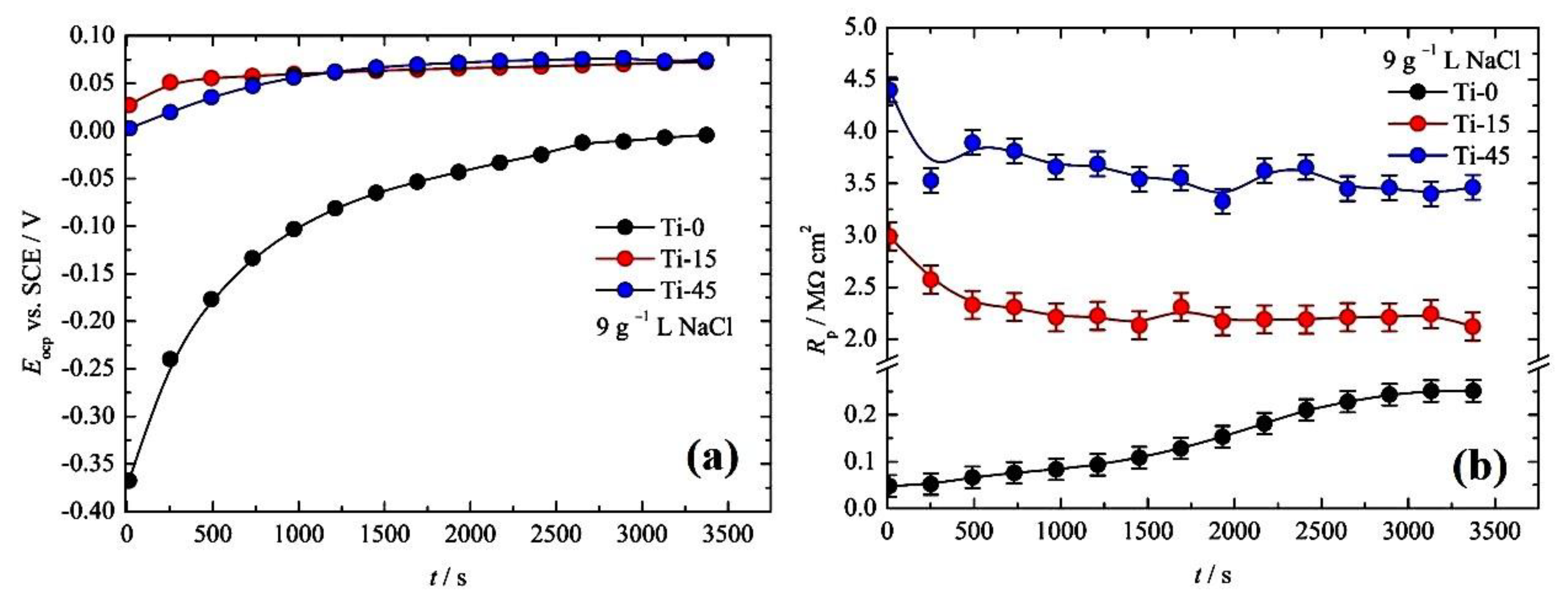

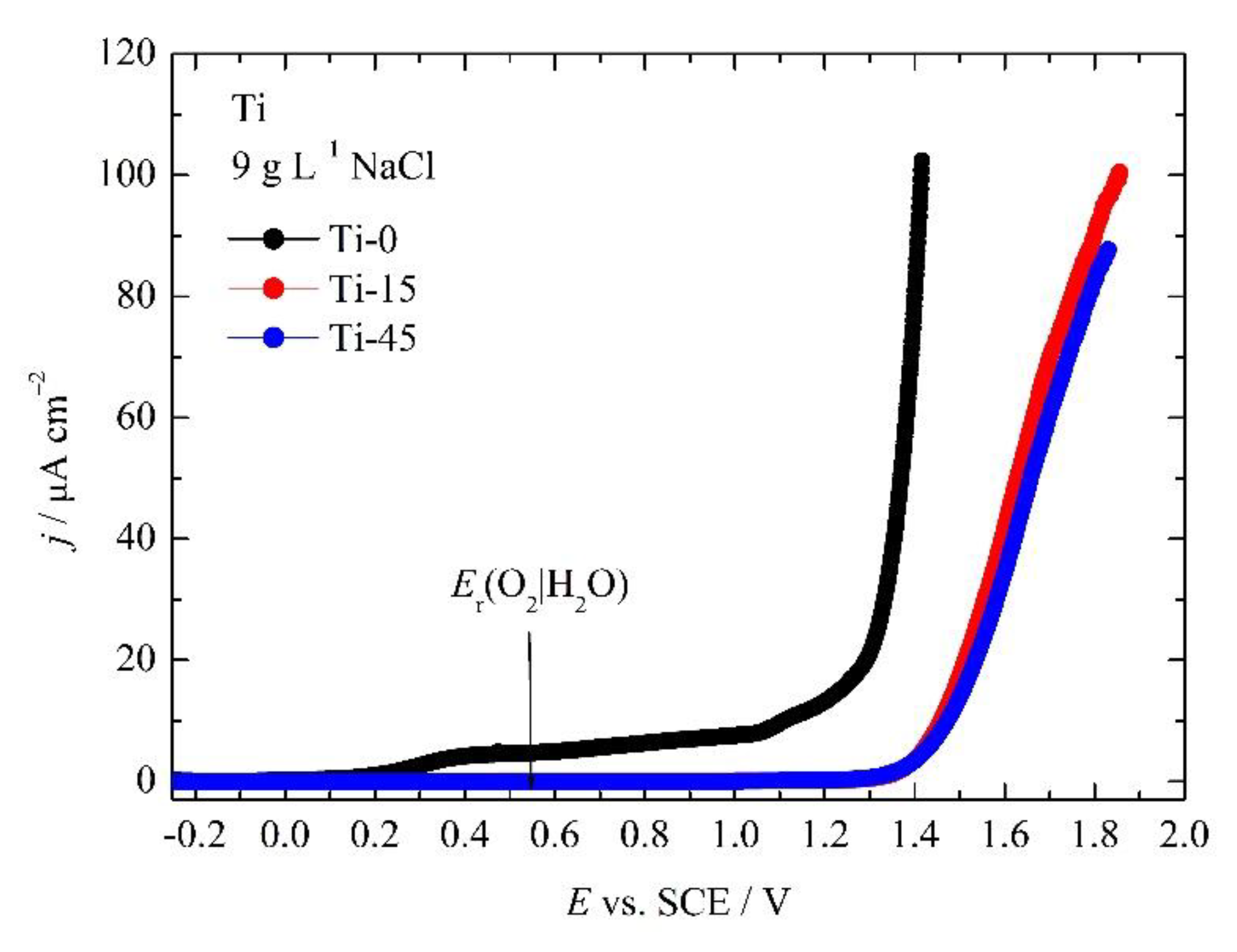

3.2. Corrosion Measurements

3.2.3. SEM and EDS Analysis After Corrosion

3.3. Biocompatibility

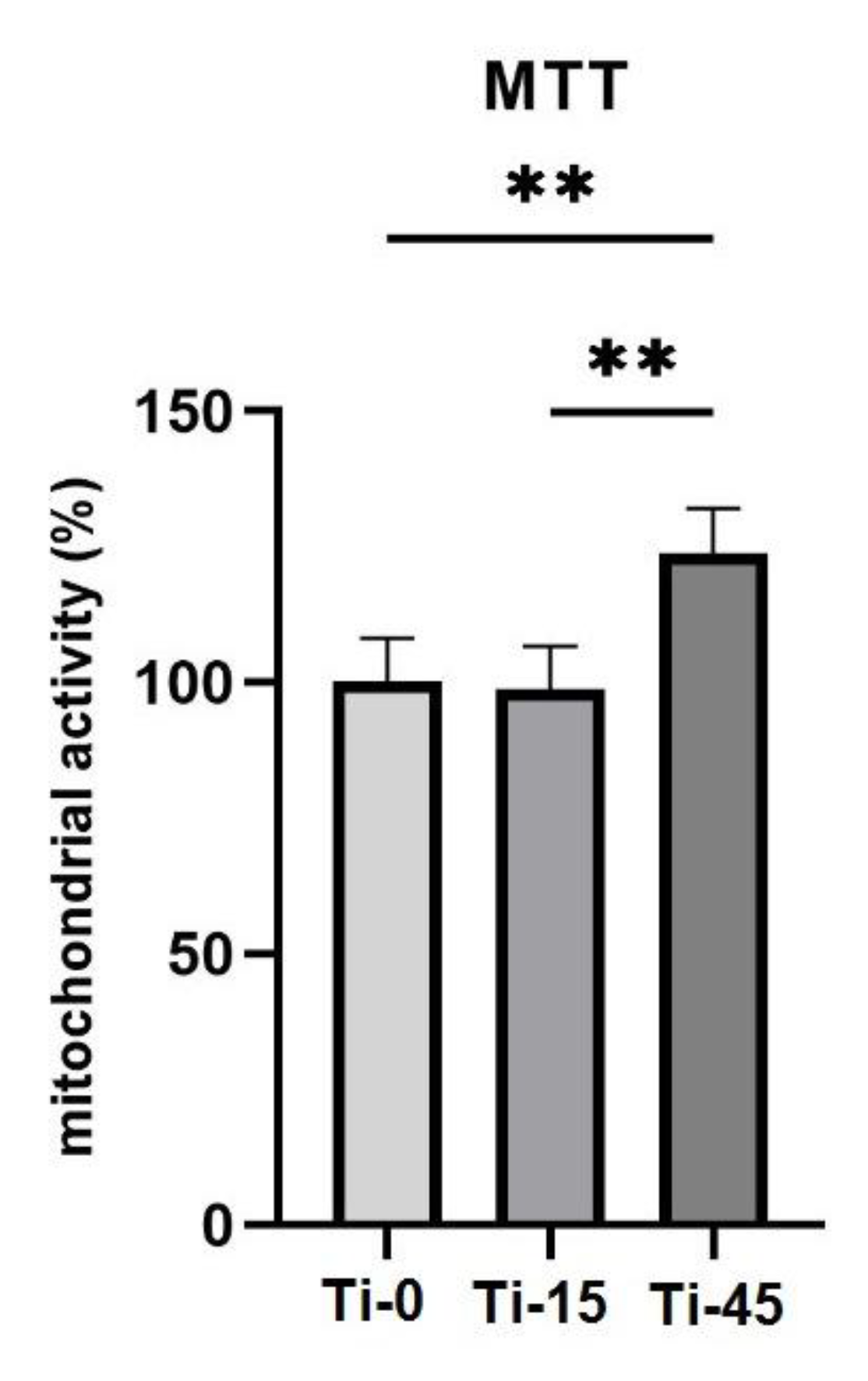

3.3.1. MTT Assay

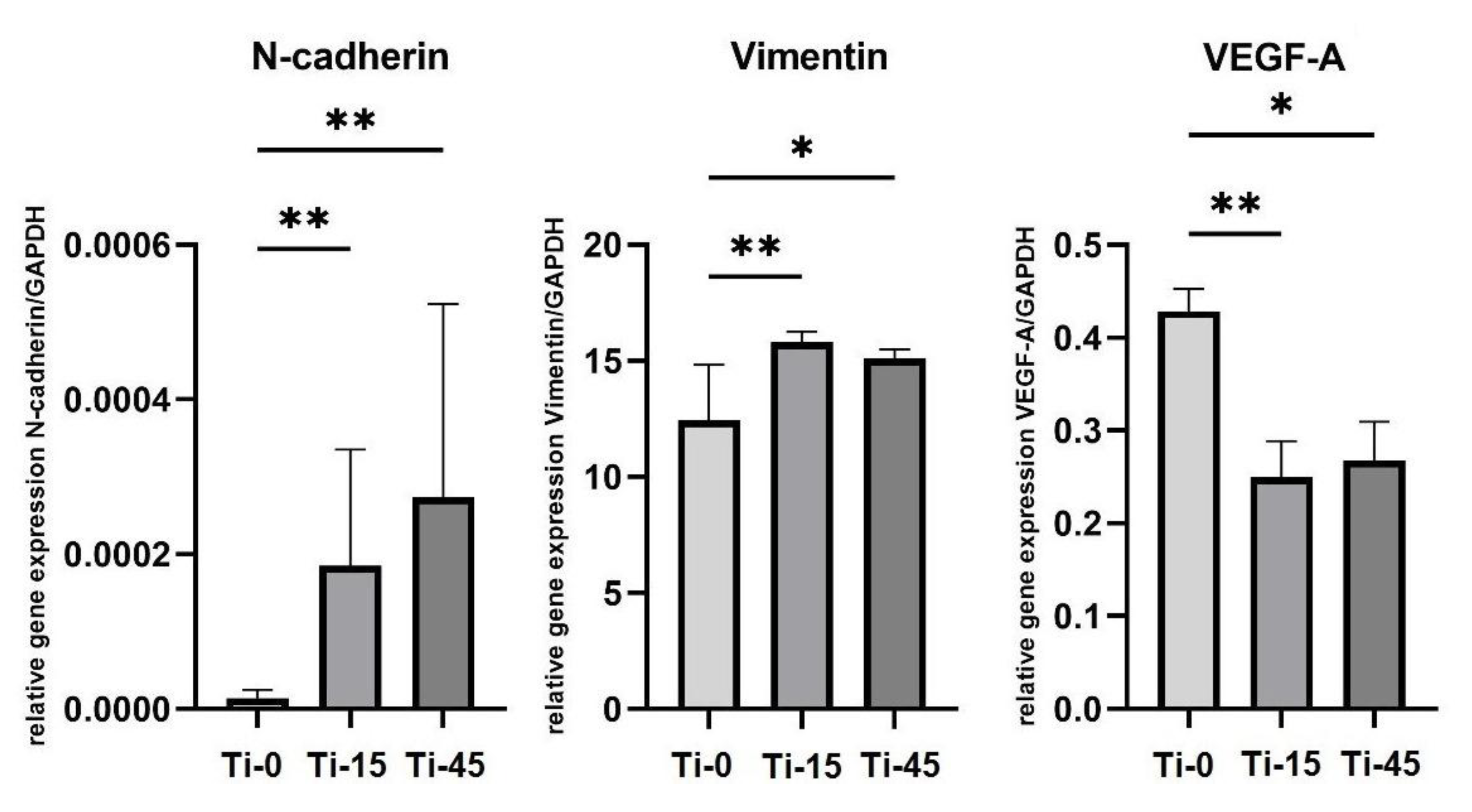

3.3.2. Gene Expression

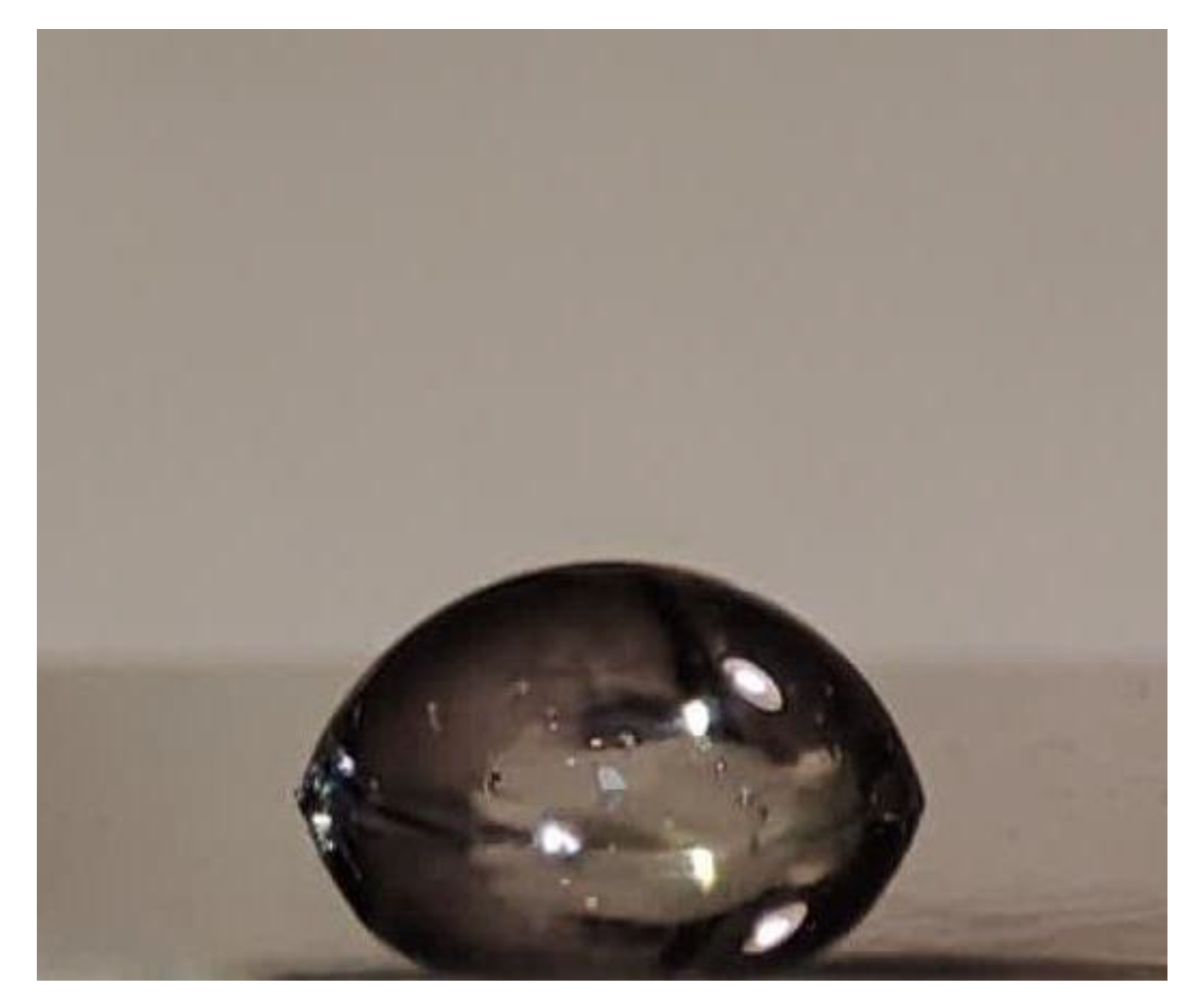

3.3.3. Wettability

3.3.4. Biological Activity

4. Conclusions

- cpTi is successfully anodized in 1 M H2SO4 at constant voltage of 15 V for 15 and 45 min.

- The thickness of anodized samples are determined by newly developed method by the analysis of frequency dependent capacitance.

- For 15 min anodization the thickness was estimated to ~40±15 nm, and for 45 min 90±30 nm

- From EDS, XRD and XPS analysis it is confirmed that oxide layer is very complex.

- Anodized samples has a superior corrosion stability in 9 g L–1 NaCl than pyre cpTi.

- By the SEM analzsis, after cyclic polarization, it is concluded that all three samples do not undergo pitting corrosion, and that the oxygen evolution reaction is the main one.

- Anodized samples enhances surface hydrophility

- Anodized samples produces a surface-driven stimulation of human gingival fibroblasts by activating their adhesion and spreading mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- F.C. Eichmiller.; Titanium applications in dentistry. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 134 (3), 347–349. [CrossRef]

- Prando, D.; Brenna, A.; Diamanti, M.V.; Beretta, S.; Bolzoni, F.; Ormellese, M.; Pedeferri, M. Corrosion of titanium: Part 2: Effects of surface treatments. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2018, 16, 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Zhu, J.; Jing, Y.; He, S.; Cheng, L.; Shi, Z. A comprehensive review of surface modification techniques for enhancing the biocompatibility of 3D-Printed titanium implants. Coatings 2023, 13 (11), 1917. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. F. Biocompatibility pathways and mechanisms for bioactive materials: The bioactivity zone. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 10, 306–322. [CrossRef]

- Barberi, J.; Spriano, S. Titanium and Protein Adsorption: An Overview of Mechanisms and Effects of Surface Features. Materials, 2021, 14, 1590. [CrossRef]

- Romanos, G. Biomolecular Cell-Signaling Mechanisms and Dental Implants: A review on the regulatory molecular biologic patterns under functional and immediate loading. Int. .J Oral. Maxillofac. Implants. 2016, 31 (4), 939–951. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, C.; Rokaya, D.; Bhattarai, B. P. Contemporary Concepts in Osseointegration of Dental Implants: A review. Bio. Med. Research. International. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Tracy, L.E.; Minasian, R.A.; Caterson, E.J. Extracellular matrix and dermal fibroblast function in the healing wound. Adv. Wound. Care. (New Rochelle) 2016, 5, 119–136. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Ju, L. S.; Irudayaraj, J. Oxygenated wound dressings for hypoxia mitigation and enhanced wound healing. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20 (7), 3338–3355. [CrossRef]

- Gaona-Tiburcio, C.; Jáquez-Muñoz, J. M.; Nieves-Mendoza, D.; Maldonado-Bandala, E.; Lara-Banda, M.; Lira-Martinez, M. A.; Reyes-Blas, H.; Baltazar-Zamora, M. Á.; Landa-Ruiz, L.; Lopez-Leon, L. D.; Almeraya-Calderon, F. Corrosion behavior of titanium alloys (Ti CP2, Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo, Ti-6Al-4V and Ti Beta-C) with anodized and exposed in NaCl and H2SO4 Solutions. Metals 2024, 14 (2), 160. [CrossRef]

- Almeraya-Calderón, F.; Jáquez-Muñoz, J. M.; Lara-Banda, M.; Zambrano-Robledo, P.; Cabral-Miramontes, J. A.; Lira-Martínez, A.; Estupinán-López, F.; Tiburcio, C. G. Corrosion behavior of titanium and titanium alloys in Ringer ́s Solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17 (7), 220751. [CrossRef]

- Jáquez-Muñoz, J.; Gaona-Tiburcio, C.; Chacón-Nava, J.; Cabral-Miramontes, J.; Nieves-Mendoza, D.; Maldonado-Bandala, E.; Delgado, A.; Rios, J. F.-D. L.; Bocchetta, P.; Almeraya-Calderón, F. Electrochemical corrosion of titanium and titanium alloys anodized in H2SO4 and H3PO4 solutions. Coatings 2022, 12 (3), 325. [CrossRef]

- Milošev, I.; Sačer, D.; Kapun, B.; Rodič, P. The effect of metallographic preparation on the surface characteristics and corrosion behaviour of TI-6AL-4V alloy in simulated physiological solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171 (11), 111503. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Tang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhou, X.; Xiang, L. Nanostructured Titanium Implant Surface Facilitating Osseointegration from Protein Adsorption to Osteogenesis: The Example of TiO2 NTAs. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2022, 17, 1865–1879. [CrossRef]

- Eisenbarth, E.; Velten, D.; Müller, M.; Thull, R.; Breme, J. Biocompatibility of β-stabilizing elements of titanium alloys. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 5705–5713. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, L. A Review on biomedical titanium alloys: recent progress and prospect. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1801215. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Che, S.; Yang, Z.; Tian, Y. Chemical Leveling Mechanism and Oxide Film Properties of Additively Manufactured Ti–6Al–4V Alloy. Journal of Materials Science 2019, 54, 13753–13766. [CrossRef]

- Vattanasup, C.; Kuntiyaratana, T.; Rungsiyakull, P.; Chaijareenont, P. Color formation on titanium surface treated by anodization and the surface characteristics: A review. Dent. J. 2023, 44 (2), 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Lu, Q.; Fan, Z. Changes in the esthetic, physical, and biological properties of a titanium alloy abutment treated by anodic oxidation. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 121 (1), 156–165. [CrossRef]

- Gulati, K.; Prideaux, M.; Kogawa, M.; Lima-Marques, L.; Atkins, G. J.; Findlay, D. M.; Losic, D. Anodized 3D-printed titanium implants with dual micro- and nano-scale topography promote interaction with human osteoblasts and osteocyte-like cells. J. Tissue. Eng. Regen. Med. 2016, 11 (12), 3313–3325. [CrossRef]

- Regonini, D.; Bowen, C. R.; Jaroenworaluck, A.; Stevens, R. A review of growth mechanism, structure and crystallinity of anodized TiO2 nanotubes. Mat. Sci. Eng. R: Rep. 2013, 74 (12), 377–406. [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Han, A.; Cheng, H.; Ma, S.; Tian, M.; Liu, L. Effects of organic solvents in anodization electrolytes on the morphology and tube-to-tube spacing of TiO2 nanotubes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 735, 136776. [CrossRef]

- Kieser, T. A.; Kunst, S. R.; Morisso, F. D. P.; Machado, T. C.; Oliveira, C. T. Anodização de titânio em ácido cítrico. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11 (8), e25311830872. [CrossRef]

- Pilipenko, A.; Maizelis, A.; Pancheva, H.; Zhelavska, Y. Electrochemical oxidation of VT6 titanium alloy in oxalic acid solutions. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2020, 14 (2), 221–226. [CrossRef]

- İzmir, M.; Ercan, B. Anodization of titanium alloys for orthopedic applications. Frontiers of Chem. Sci. Eng. 2018, 13 (1), 28–45. [CrossRef]

- Karambakhsh, A.; Afshar, A.; Ghahramani, S.; Malekinejad, P. Pure commercial titanium color anodizing and corrosion resistance. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2011, 20 (9), 1690–1696. [CrossRef]

- Wadhwani, C. P. K.; O’Brien, R.; Kattadiyil, M. T.; Chung, K.-H. Laboratory technique for coloring titanium abutments to improve esthetics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 115 (4), 409–411. [CrossRef]

- Wadhwani, C.; Brindis, M.; Kattadiyil, M. T.; O’Brien, R.; Chung, K.-H. Colorizing titanium-6aluminum-4vanadium alloy using electrochemical anodization: Developing a color chart. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 119 (1), 26–28. [CrossRef]

- Webster, T. J.; Ross, N. Anodizing color coded anodized Ti6Al4V medical devices for increasing bone cell functions. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2013, 109. [CrossRef]

- Khadiri, M.; Elyaagoubi, M.; Idouhli, R.; Koumya, Y.; Zakir, O.; Benzakour, J.; Benyaich, A.; Abouelfida, A.; Outzourhit, A. Electrochemical study of anodized titanium in phosphoric acid. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 2020 (1). [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, K. F.; Ulfah, I. M.; Kozin, M. Effect of anodic oxidation voltages on the color and corrosion resistance of commercially pure titanium (CP-Ti). Journal of Evrimata. 2023, 18–23. [CrossRef]

- Tamilselvi, S.; Murugaraj, R.; Rajendran, N. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopic studies of titanium and its alloys in saline medium. Mater. Corros. 2007, 58 (2), 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kushwaha, M. K. Surface modification of titanium alloy by anodic oxidation method to improve its biocompatibility. Curr. Sci. 2021, 120 (5), 907. [CrossRef]

- 34 Capek, D.; Gigandet, M.-P.; Masmoudi, M.; Wery, M.; Banakh, O. Long-time anodisation of titanium in sulphuric acid. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 202 (8), 1379–1384. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, S.N.; Corbett, R.A. An Assessment of ASTM F 2129 Electrochemical testing of small medical implants-lessons learned.; NACE, 2007; p. NACE-07674. Available on-line at: https://corrosionlab.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/NACE2007.pdf.

- ISO 10271:2009: Dentistry - Corrosion test methods for metallic materials, International Organization for Standardization; Switzerland, Geneva, 2009.

- ASTM F 2129-01:.Standard test method for conducting cyclic potentiodynamic polarization measurements to determine the corrosion susceptibility of small implant devices. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International; 2001.

- Grgur, B. N.; Lazić, V.; Stojić, D.; Rudolf, R. Electrochemical testing of noble metal dental alloys: The influence of their chemical composition on the corrosion resistance. Corr. Sci., 2021, 184, 109412. [CrossRef]

- Lazić, M. M.; Majerič, P.; Lazić, V.; Milašin, J.; Jakšić, M.; Trišić, D.; Radović, K. Experimental investigation of the biofunctional properties of Nickel–Titanium alloys depending on the type of production. Molecules 2022, 27 (6), 1960. [CrossRef]

- Prando, D.; Fajardo, S.; Pedeferri, M.; Ormellese, M. Titanium anodization efficiency through real-time gravimetric measurement of oxygen evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167 (6), 061507. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Z. Z.; Xia, Y.; Huang, Z.; Lefler, H.; Zhang, T.; Sun, P.; Free, M. L.; Guo, J. A novel chemical pathway for energy efficient production of Ti metal from upgraded titanium slag. Chem. Eng. Journal 2015, 286, 517–527. [CrossRef]

- Sul, Y.-T.; Johansson, C. B.; Jeong, Y.; Albrektsson, T. The electrochemical oxide growth behaviour on titanium in acid and alkaline electrolytes. Med. Eng. Phys. 2001, 23 (5), 329–346. [CrossRef]

- Uudsemaa, M.; Tamm, T. Calculations of hydrated titanium ion complexes: structure and influence of the first two coordination spheres. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 342 (5–6), 667–672. [CrossRef]

- Kallies, B.; Meier, R. Electronic structure of 3d [M(H2O)6]3+ Ions from ScIII to FeIII: A quantum mechanical study based on DFT computations and natural bond orbital analyses. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40 (13), 3101–3112. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Thompson, G. E. Formation of porous anodic oxide film on titanium in phosphoric acid electrolyte. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 24 (1), 59–66. [CrossRef]

- Spajić, I.; Rodič, P.; Šekularac, G.; Lekka, M.; Fedrizzi, L.; Milošev, I. The effect of surface preparation on the protective properties of Al2O3 and HfO2 thin films deposited on cp-titanium by atomic layer deposition. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 366, 137431. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ding, W. F.; Dai, J. B.; Xi, X. X.; Xu, J. H. A comparison between conventional speed grinding and super-high speed grinding of (TiCp + TiBw) / Ti–6Al–4V composites using vitrified CBN wheel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 72 (1–4), 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Bail, A. L. Whole powder pattern decomposition methods and applications: A retrospection. Powder Diffr. 2005, 20 (4), 316–326. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. J.; Zhong, X.; Walton, J.; Thompson, G. E. Anodic film growth of titanium oxide using the 3-electrode electrochemical technique: effects of oxygen evolution and morphological characterizations. J. Electrochem. Soc 2015, 163 (3), E75–E82. [CrossRef]

- Milićević, N.; Novaković, M.; Potočnik, J.; Milović, M.; Rakočević, L.; Abazović, N.; Pjević, D. Influencing surface phenomena by Au diffusion in buffered TiO2-Au thin films: Effects of deposition and annealing processing. Surf. Interfaces. 2022, 30, 101811. [CrossRef]

- Esmailzadeh, S.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Sarlak, H. Interpretation of cyclic potentiodynamic polarization test results for study of corrosion behavior of metals: A review. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2018, 54 (5), 976–989. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H.; Park, K.; Choi, K.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, S.; Jeong, C.-M.; Huh, J.-B. Cell adhesion and in vivo osseointegration of Sandblasted/Acid Etched/Anodized dental implants. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2015, 16 (5), 10324–10336. [CrossRef]

- Mary, S.; Charrasse, S.; Meriane, M.; Comunale, F.; Travo, P.; Blangy, A.; Gauthier-Rouvière, C. Biogenesis of N-Cadherin-dependent cell-cell contacts in living fibroblasts is a microtubule-dependent kinesin-driven mechanism. Mol Biol. Cell. 2002, 13, 285–301. [CrossRef]

- Miron-Mendoza, M.; Poole, K.; DiCesare, S.; Nakahara, E.; Bhatt, M.P.; Hulleman, J.D.; Petroll, W.M. The role of vimentin in human corneal fibroblast spreading and myofibroblast transformation. Cells 2024, 13, 1094. [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.; Kodra, A.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Golinko, M. S.; Ehrlich, H. P.; Brem, H. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in wound healing. J. Surg. Res. 2008, 153 (2), 347–358. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Christ, S.; Correa-Gallegos, D.; Ramesh, P.; Gopal, S. K.; Wannemacher, J.; Mayr, C. H.; Lupperger, V.; Yu, Q.; Ye, H.; Mück-Häusl, M.; Rajendran, V.; Wan, L.; Liu, J.; Mirastschijski, U.; Volz, T.; Marr, C.; Schiller, H. B.; Rinkevich, Y. Injury triggers fascia fibroblast collective cell migration to drive scar formation through N-cadherin. Nat Comm. 2020, 11 (1). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Shen, Y.; Mohanasundaram, P.; Lindström, M.; Ivaska, J.; Ny, T.; Eriksson, J.E. Vimentin Coordinates Fibroblast Proliferation and Keratinocyte Differentiation in Wound Healing via TGF-β-Slug Signaling. Cheng, F.; Shen, Y.; Mohanasundaram, P.; Lindström, M.; Ivaska, J.; Ny, T.; Eriksson, J. E. Vimentin coordinates fibroblast proliferation and keratinocyte differentiation in wound healing via TGF-β–Slug signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016, 113 (30). [CrossRef]

- Crenn, M.-J.; Dubot, P.; Mimran, E.; Fromentin, O.; Lebon, N.; Peyre, P. Influence of Anodized Titanium Surfaces on the Behavior of Gingival Cells in Contact with: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Crystals 2021, 11 (12), 1566. [CrossRef]

- Jokanović, V.; Čolović, B.; Nenadović, M.; Petkoska, A. T.; Mitrić, M.; Jokanović, B.; Nasov, I. Ultra-high and near-zero refractive indices of magnetron sputtered thin-film metamaterials based on TIXOY. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2016, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Yeniyol, S.; Bölükbaşı, N.; Bilir, A.; Çakır, A.F.; Yeniyol, M.; Ozdemir, T. Relative contributions of surface roughness and crystalline ttructure to the biocompatibility of titanium nitride and titanium oxide coatings deposited by PVD and TPS coatings. Int. Sch. Res. Notices. 2013, 2013, 783873. [CrossRef]

- Čolović, B.; Kisić, D.; Jokanović, B.; Rakočević, Z.; Nasov, I.; Petkoska, A. T.; Jokanović, V. Wetting properties of titanium oxides, oxynitrides and nitrides obtained by DC and pulsed magnetron sputtering and cathodic arc evaporation. Mater. Sci. Pol. 2019, 37 (2), 173–181. [CrossRef]

- Arima, Y.; Iwata, H. Effect of wettability and surface functional groups on protein adsorption and cell adhesion using well-defined mixed self-assembled monolayers. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3074–3082. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yan, C.; Zheng, Z. Functional Polymer Surfaces for Controlling Cell Behaviors. Materials Today 2018, 21, 38–59. [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzam, N.; Alazzam, A. Micropatterning of cells via adjusting surface wettability using plasma treatment and graphene oxide deposition. PLoS ONE 2022, 17 (6), e0269914. [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, C.P.; Keerthi Krishnan, K.; Sudeep, U.; Ramachandran, K.K. Osteogenic and Antibacterial Properties of TiN-Ag Coated Ti-6Al-4V Bioimplants with Polished and Laser Textured Surface Topography. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2023, 474, 130058. [CrossRef]

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

| N-cadherin: | AGGGTGGACGTCATTGTAGC | CTGTTGGGGTCTGTCAGGAT |

| VEGF-A: | GGGAGCTTCAGGACATTGCT | GGCAACTCAGAAGCAGGTGA |

| Vimentin: | TCTACGAGGAGGAGATGCGG | GGTCAAGACGTGCCAGAGAC |

| GAPDH: | TCATGACCACAGTCCATGCCATCA | CCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGT |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | Approximate color appearance |

| Ti-0 | 57,43 | 1,33 | 4,74 |  |

| Ti-15 | 36,44 | 6,19 | -12,87 |  |

| Ti-45 | 32,79 | 10,14 | -10,17 |  |

| Sample | Ti wt.% | O wt.% | Ti at.% | O at.% |

| Ti-0 | 98.4 | 7.1 | 82.2 | 17.8 |

| Ti-45 | 81.5 | 18.5 | 59.5 | 40.5 |

| Lattice parameters, space group P63/mmc | |||

| Sample | a [Å] | b [Å] | c [Å] |

| Ti-0 | 2.9531 | 2.9531 | 4.6900 |

| Ti-45 | 2.9516 | 2.9516 | 4.6877 |

| Sample |

Eocp mV |

jocp nA cm–2 |

Rp MΩ cm2 |

jp,c nA cm–2 |

Ecorr mV |

bc mV dec–1 |

jcorr nA cm–2 |

jpass nA cm–2 |

Eb mV |

Erp mV |

ΔE mV |

| Ti-0 | 0 | 139 | 0.25 | 103 | –134 | –177 | 29 | ~5500 | 968 | 794 | 1102 |

| Ti-15 | 69 | 9.8 | 2.14 | 12 | –152 | –115 | 2.42 | 7-80 | 1032 | 835 | 1180 |

| Ti-45 | 75 | 4.9 | 3.48 | 7.3 | –154 | –116 | 1.84 | 4-20 | 1062 | 801 | 1225 |

| Sample |

Eocp mV |

Ecorr mV |

j at Ecorr+0.3 V nA cm–2 |

Eb V |

jb nA cm–2 |

| Ti-0 | 0 | –134 | 650 | 0.968 | 8500 |

| Ti-15 | 69 | –148 | 12.1 | 0.1032 | 90 |

| Ti-45 | 75 | –163 | 4.7 | 0.1062 | 21 |

| Ti wt.% | O wt.% | Ti at.% | O at.% | |

| Ti-0 | 91.4 | 8.6 | 78.0 | 22.0 |

| Ti-45 | 82.4 | 17.6 | 61.0 | 39.0 |

| Reference liquid | Sample | Mean | St. dev | Min | Max |

| Distilled water | Ti-0 | 50.01 | 3.83 | 45.20 | 54.81 |

| Distilled water | T-15i | 42.43 | 1.90 | 39.88 | 44.98 |

| Distilled water | T-45i | 40.27 | 3.13 | 36.53 | 44.66 |

| Diiodomethane | Ti-0 | 36.10 | 1.73 | 33.90 | 38.23 |

| Diiodomethane | T-15i | 27.64 | 2.14 | 26.40 | 29.06 |

| Diiodomethane | Ti -45 | 24.20 | 1.60 | 22.5 | 25.4 |

| Ethylene-glycol | Ti-0 | 46.66 | 2.47 | 43.64 | 49.12 |

| Ethylene-glycol | Ti-15 | 36.05 | 2.15 | 33.90 | 37.06 |

| Ethylene-glycol | Ti 45 | 21.51 | 1.13 | 20.05 | 23.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).