1. Introduction

The combination of medicine and technology is currently one of the most intensively developed fields of materials engineering due to the high and constant demand for newer and better possibilities to improve or extend people's lives. For this purpose, among other things, numerous studies of various biomaterials are carried out and newer and more efficient techniques for their application are created [

1].

Biomaterials are the basis for the development of medicine because they allow safe contact with a living organism. They are used for surgical tools and other medical devices that come into contact with tissues. They are also used for implants. The use of implants, whether biomechanical or aesthetic, is becoming common nowadays and allows the body to continue functioning. Biomaterials are a very specific group of materials that include materials that vary significantly in terms of type, chemical composition, mechanical and physical properties. However, it has a common feature without which a given material could not be referred to as a biomaterial, and this is biocompatibility [

1,

2,

3].

Currently, one of the biomaterials most often used for implants is titanium [

3,

4,

5] and its alloys [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Titanium, apart from its modulus of elasticity similar to bone, which is the smallest among metal biomaterials, has a number of other advantages [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. First of all, it is characterized by very high resistance to crevice, stress and general corrosion corrosion, even in chloride environments, all thanks to the ability to self-passivation, which results in the formation of a barrier TiO

2 oxide layer [

4,

5]. This is an extremely important element when it comes to use in implantology. In addition, titanium also has the highest biotolerance among currently available and used metallic biomaterials. This metal also has an appropriate ratio of yield strength to tensile strength. It also has high mechanical strength, mainly fatigue strength, and this is an important element when it comes to the durability of implants. It has a low density of 4.54 g cm

−3 and paramagnetic properties [

11,

12,

13].

Among all available varieties of titanium, Grade 4 has the highest mechanical strength. At the same time, it has good plasticity and good impact properties at low temperatures. It can be processed like other classes, cold or hot. It can be welded and cast. It is most often used in the production of aircraft and marine engines, in chemical processing plants and, above all, in medicine [

4,

5,

11].

The surface of titanium can be modified in various ways using for example tytan plasma spray (TPS) [

14], sandblasting leading to obtaining an resorbable blast media surface (RBM) [

4,

15], deposition of hydroxyapatite (HA) [

16,

17], double eatching (DE) [

18], Sandblasting Large-grit Acid-eatching (SLA) [

19], obtaining a hydrophilic surface (SLActive) [

20], oxidation (anodizing) [

21,

22,

23] including plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) also known as micro arc oxidation (MAO) [

24]. The creation of differentiated pores on its surface has become very important, thanks to which it connects with the bone tissue much more easily, and due to the elastic modulus being similar to bone, such an implant does not loosen. The porous surface of biomaterials has a biomimetic nature because it imitates the structure of trabecular bone, so it can find numerous applications. One of them is intelligent drug delivery systems (DDS) [

25,

26,

27]. Thanks to the porous structure resembling a sponge, the medicinal substance can be applied to the pore spaces, surrounded by polymer and delivered to the living organism. Such a drug carrier releases the drug in a controlled manner, so there is no need to constantly take tablets, maintain appropriate time intervals between doses, and in addition, the phenomenon of exceeding the limits of the maximum and minimum amount of the drug substance in the body is eliminated. This is an extremely important element because the drug does not become toxic to the body if the maximum dose is exceeded, nor does it lose its therapeutic power if the minimum dose is exceeded, but it is dosed continuously in an appropriately selected amount. This makes the therapy more effective, safe and comfortable.

Particularly interesting is the possibility of producing porous oxide layers on titanium surface by anodizing [

21,

22,

23,

24,

28,

29]. Many factors determine the outcome of the oxidation process. Important factors include, among others, the applied voltage, current density, time, chemical composition of the electrolyte, electrolyte temperature, its pH, blowing the electrolyte with inert gas or mixing. In the case of titanium anodizing, the most frequently used electrolytes are solutions based on orthophosphoric(V) acid with the addition of hydrofluoric acid, because this method introduces phosphorus into the layer, which is the main component of bone and contributes to faster integration of the implant with the bone. The voltage applied to the workpiece can range from 0.5 to 300 V, and the type of oxide layer formed depends on the applied voltage. A continuous oxide layer, porous oxide layer or nanotubular oxide layers may be created. The layers created by anodizing can be crystalline or amorphous, stoichiometric and non-stoichiometric, with various morphologies and phase structures.

Anodizing, when performed properly, allows the creation of an oxide layer with a porous structure. This surface is beneficial for implants because it facilitates connection with the bone tissue, which bonds with the pores. The diameter of such pores should be from 300 to 500 μm, because this size combines best with bone tissue. Porous layers also have a lower modulus of elasticity, even more similar to bone, which additionally reduces stress and extends the life of such an implant. The thicker the layer, the greater the corrosion resistance and biocompatibility of the material. Oxide layers also limit the penetration of ions from the implant surface into the body [

8,

9].

Inspired by the presented possibilities of development of modern biomaterials, this work was devoted to developing a new method for the production of porous oxide layers on the surface of commercially pure titanium Grade 4 (CpTi G4) for use in medicine. The proposed research was inspired by intelligent systems for releasing medicinal substances in the body and was to result in the development of a new generation of drug carriers to improve the effectiveness, safety and convenience of therapy. The first stage was to prepare the surface of titanium samples for testing by mechanical grinding and electrochemical polishing. The second stage was the selection of an appropriate bath and anodizing parameters to create porous oxide layers on the CpTi G4. The third stage was the characterization of the microstructure, chemical composition and roughness of the CpTi G4 surface before and after the anodizing process. The fourth stage was the characterization of the release kinetics of gentamicin sulfate from the produced oxide films as potential drug carriers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of CpTi G4 Substrate

Disk-shaped CpTi G4 samples (Bibus Metals, Dąbrowa, Poland) with a diameter of 10 mm and a height of 5 mm were mechanically ground using the metallographic grinding and polishing machine Metkon Forcipol 102 (Metkon Instruments Inc., Bursa, Turkey) on SiC abrasive paper with a grain size of 600# (Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL, USA). The polished CpTi G4 samples were cleaned for 20 min in the USC 300 TH ultrasonic cleaner (VWR International, Radnor, PA, USA), first in acetone (Avantor Performance Materials Poland S.A., Gliwice, Poland), and then in ultrapure water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ cm (Milli-Q® Advantage A10 Water Purification System, Millipore SAS, Molsheim, France).

2.2. Electrochemical Oxidation of CpTi G4 Surface

Electrodes were made from CpTi G4 samples by attaching an insulated copper wire to the back wall using chemically resistant epoxy resin (Elecrodag 915 silver paint, TAAB Laboratories Equipment Ltd., UK). The resin provided electrical conductivity between the CpTi G4 sample and the Cu wire. The next step was to protect the back wall of the samples and their sides with two-component epoxy glue (Distal Classic, Libella Ltd., Warszawa, Poland). The electrodes prepared in this way were electrolytically polished in an acid-free solution containing 200 cm3 of ethylene alcohol, 800 cm3 of ethylene glycol, 58.5 cm3 of sodium chloride, and 10 cm3 of ultrapure water. Then, each electrode was immersed in an electrochemical polishing solution poured into a 100 ml beaker and connected as an anode to a Kikusui PWR800H Regulated DC Power Supply (Kikusui Electronics Corporation, Yokohama, Japan). The cathode in the two-electrode system was a mesh made of a platinum-iridium alloy, which had previously been cleaned in HNO3 dissolved in ultrapure water in 1:1 proportions, rinsed thoroughly with ultrapure water, and then air-dried before immersion in the electrochemical polishing solution. Electrochemical polishing was performed at room temperature and the applied constant voltage (U) was 20 V. The time of the first polishing part (t) was 50 min. Each electrode was then disconnected and rinsed with ultrapure water, then reconnected and electrochemical polishing continued under the same conditions for another 10 min.

Then, the process of electrochemical oxidation of the CpTi G4 surface was carried out in the same system as in the electrochemical polishing process. A solution of 1M ethylene glycol with the addition of 40 g of ammonium fluoride was used for the electrochemical oxidation process. The anodizing was carried out at a voltage of 20 V and for 2, 18, 24 and 48 hours at room temperature. After anodizing, the anode was rinsed with ultrapure water.

2.3. Materials Characterization

The CpTi G4 surface before and after electrochemical oxidation was subjected to microstructure tests using a Hitachi HD-2300A field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) (Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in a low vacuum of 50 Pa and an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, and Hitachi 25 TM4000/TM4000Plus II - Hitachi High Technologies (Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in a low vacuum with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. Thanks to the high efficiency of the secondary electron detector, it was possible to obtain high resolution FE-SEM images. A quantitative examination of the surface chemical composition and the surface distribution of elements was also performed using an energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) detector.

The surface roughness of the obtained oxide layers and the CpTi G4 substrate was measured using the contact profilometry method using a Mitutoyo Surftest SJ-210 profilometer (Mitutoyo Corporation, Kanagawa, Japan). Contact measurement of the geometric structure of the tested surfaces was performed in accordance with the ISO 21920-3:2022-06 standard [

30]. The speed of the measuring needle was 0.5 mm s

−1, and the measurement covered a section of 4 mm. Five measurements were recorded for each sample and their average was presented as the result.

2.4. Implementation and Release Kinetics of Gentamicin Sulfate from the Oxidized Surface of CpTi G4

To assess the possibility of using the porous oxide layers obtained on the CpTi G4 surface as drug carriers, the selected drug was implemented in the form of gentamicin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MI, USA). Before drug implementation, the CpTi G4 samples with porous oxide layers were subjected to surface functionalization by heparinization by mixing 40.00 mg mL−1 heparin with 19.06 mg mL−1 N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide, hydrochloride (EDAC) and 11.50 mg mL−1 N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS). This mixture was added to 10 mL of MES buffer (2-(N-morpholine) ethanesulfonic acid) with pH = 4.5(1) and mixed together for 10 minutes (solution I). To the solution thus obtained, a solution consisting of 102.20 mg mL−1 of dopamine and 1 ml of MES buffer with a pH of 4.5(1) was added (solution II). Each CpTi G4 sample with a porous oxide layer was placed in a separate container with the obtained mixture, tightly secured against spilling and subjected to a heparinization reaction using mixing with a laboratory shaker at a speed of 40 rpm for 12 h. After this time, the samples were removed from the solution, dried, and then immersed in a solution containing 250 mg of gentamicin sulfate dissolved in 5 mL of ultrapure water. The samples were kept in the drug solution for 48 h at 37 °C.

The release kinetics of gentamicin sulfate from porous oxide layers obtained on the CpTi G4 surface was examined by immersing the samples in 15 mL of phosphate buffer (PBS), the pH of which was 7.4(1) at 37 °C. The release kinetics of the implemented drug substance was examined every 24 hours for 48 hours, and every hour in the first 3 hours. Each time, 1.5 mL of the solution was taken and the same amount of fresh solution was added. The study was performed using the UV-VIS absorption spectroscopy method (Biochrom WPA Biowave II UV/Visible Spectrophotometer, Cambridge, England). Absorbance values were measured at a wavelength of λ = 275 nm using a quartz measuring cell. Initially, the absorbance value of the drug solution before and after the implementation of the drug was characterized, and then of the sampled solution after drug implementation.

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Measurements

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurements involved passing an infrared light beam through the tested samples and revealing the amount of energy absorbed at each wavelength. Thanks to this, it was possible to generate transmittance or absorbance spectra, and their analysis made it possible to learn the details of the molecular structure of the tested samples. Infrared radiation covered the range of 400–4000 cm−1. 30 scans were performed. The result of the study was an interferogram transformed into an absorption spectrum. The spectra were taken using the attenuated total reflection - Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) method. A Shimadzu IR Prestige-21 FTIR spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used for the study, which was equipped with an ATR reflectance adapter with a diamond. The ATR-FTIR method was used in the research to confirm the presence of gentamicin sulfate incorporated into porous oxide layers on the Ti G4 surface.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Electrochemical Characteristics of the Process of Creating Porous Oxide Layers on the Surface of Cp Ti G4

Changes in the anodic current density at a voltage of U = 20 V during 2, 18, 24 and 48 h of electrochemical oxidation of the Ti G4 surface to produce porous oxide layers are shown in

Figure 1a-d, respectively.

Based on the shape of the obtained current-time characteristics for the CpTi G4 under the proposed electrochemical oxidation conditions, one can notice the repeatability of the course of the obtained curves shown in

Figure 1a-d. Electrochemical noise is also visible resulting from the semiconductive properties of the oxide layers formed on the surface of the CpTi G4 substrate. At the beginning part of each curve, there is a sudden drop in the anodic current density from initial values in the range of 0.014 to 0.040 A cm

−2 to values close to 0 A cm

−2 (stage 1), after which the anodic current density increases to a value oscillating around 0.005 A cm

−2 (stage 2). Then, a plateau is observed, the length of which increases with the anodizing time, which ranged from 2 to 48 h (stage 3). This nature of changes in the anodic current density as a function of time during the electrochemical oxidation of CpTi G4 proves the multi-stage process of creating a porous oxide layer, described by the Equations (1)− (4). In the process of anodizing CpTi G4 in an aqueous solution, the oxidation reaction (1), oxide dissolution reactions (2, 3) and the reaction of releasing oxygen from water (4) take place [

21,

22,

23]:

In the first stage, a thin (0.01 - 0.1 μm) and compact barrier layer is created by thickening the self-passive oxide layer (TiO

2). In the second stage, the barrier layer is rebuilt at the interface of oxide layer | electrolyte and a porous layer is formed. The volume of TiO

2 formed is larger than the volume of the reacted metal, as a result of which tensile stresses appear in the oxide layer, which lead to cracks in the barrier layer. The emerging cracks promote the formation of pores and the diffusion of electrolyte into them. The moment at which the anodic current density is stabilized at the level of 0.005 A cm

−2 corresponds to the beginning of the process of producing an oxide layer with a porous microstructure (

Figure 1). In the third stage, only thickening of the porous layer is observed in the range from several to 150 μm. The increase in the thickness of the oxide layer occurs through the deepening of the pores formed as a result of two competing processes, namely the formation of a porous oxide film and its dissolution by the electrolyte.

3.2. FE-SEM Characterization of the CpTi G4 Microstructure before and after the Electrochemical Oxidation Proces

FE-SEM images of the CpTi G4 microstructure after initial mechanical grinding on #600 grit abrasive paper and electrochemical polishing are shown in

Figure 2a and b, respectively.

The microscopic FE-SEM image of the CpT G4 surface after mechanical grinding shows numerous scratches and micro-cavities remaining after grinding (

Figure 2a). One can see that obtaining a mirror-like surface of the CpTi G4 requires subsequent stages of mechanical grinding using abrasive papers of higher gradation and mechanical polishing using polishing pastes or suspensions. The surface morphology of the CpTi G4 after electrochemical polishing is smoothed (

Figure 2b). Based on the obtained FE-SEM results, it can be concluded that electrochemical polishing significantly improved the surface quality of the CpTi G4, removing imperfections in the surface microstructure and allowing to obtain a continuous and uniform oxide layer, which can additionally increase the corrosion resistance in a biological environment compared to an ultra-thin self-passive oxide layer [

4].

The microstructure of the oxide layers produced on the CpTi G4 surface at a voltage of 20 V for electrochemical oxidation times of 2, 18, 24 and 48 h is shown in FE-SEM images in

Figure 3a-d. In all obtained microscopic images, the porous microstructure of the surface of the oxide layers can be observed.

Based on the obtained FE-SEM images visible in

Figure 3a-d, it can be concluded that the longer the electrochemical oxidation time, the more extensive the pore microstructure on the CpTi G4 surface becomes. During electrochemical oxidation lasting 2 h, pores were formed in the form of points distributed on the solid surface. Electrochemical oxidation for 18, 24 and 48 h provided a more developed microstructure, which is characterized by a complex pore structure. It can be observed that smaller pores were formed in larger pores, and the resulting microstructures began to resemble the structure of the spongy (cancellous) substance found in bone [

31]. The creation of such a homogeneous and porous microstructure during electrochemical oxidation was possible thanks to the previously prepared CpTi G4 surface, which was electrochemically polished.

3.3. EDS Study of Chemical Composition

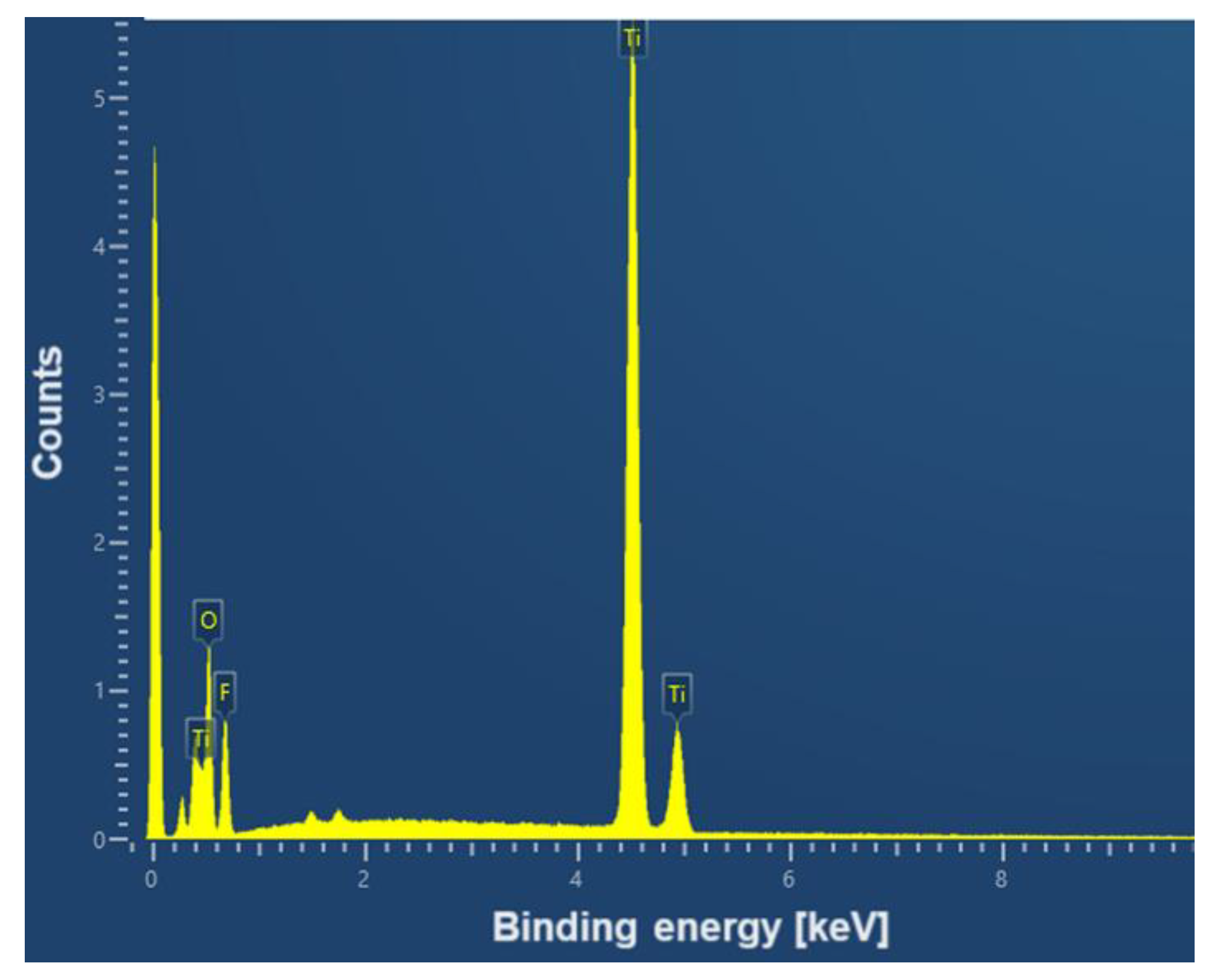

Figure 4a-d show exemplary maps of the surface distribution of elements identified in the examined micro-area on the CpTi G4 surface after electrochemical oxidation at 20 V for 48 h, obtained using the EDS method.

Qualitative analysis of the surface chemical composition performed for all obtained porous oxide layers showed the presence of elements such as titanium, oxygen and fluorine, and revealed their uniform distribution. The presence of oxygen results from the electrochemical oxidation process and the formation of oxide layers on the surface of CpTi G4. EDS microanalysis also showed the presence of fluorine in the tested oxide layers, which results from the chemical composition of the electrolyte in the form of 1M ethylene glycol with the addition of 40 g of ammonium fluoride used for oxidation. Fluoride ions originating from ammonium fluoride had the ability to be incorporated from the electrolyte into the porous oxide layers formed during the anodizing process. The incorporation of fluorine into oxide layers is a beneficial phenomenon because fluorine has bactericidal properties and can therefore inhibit the growth of bacteria after implantation [

32].

An example EDS spectrum showing the dependence of the number of counts as a function of binding energy for the CpTi G4 surface after electrochemical oxidation at 20 V for 48 h is shown in

Figure 5. The EDS microanalysis confirmed the presence of chemical elements with atomic numbers Z of 22, 8 and 9, i.e. titanium, oxygen and fluorine, respectively.

Local measurement of the chemical composition of the tested materials using the micro-analytical EDS method showed that titanium, as the substrate material, has the highest weight percentage, which reaches 53.9(4) wt%. The oxygen content was estimated at 29.0(4) wt%, and fluorine at 17.1(3) wt%. However, it should be noted that the EDS method has limitations when determining the quantitative content of light elements, whose characteristic radiation is absorbed more intensively by the tested samples.

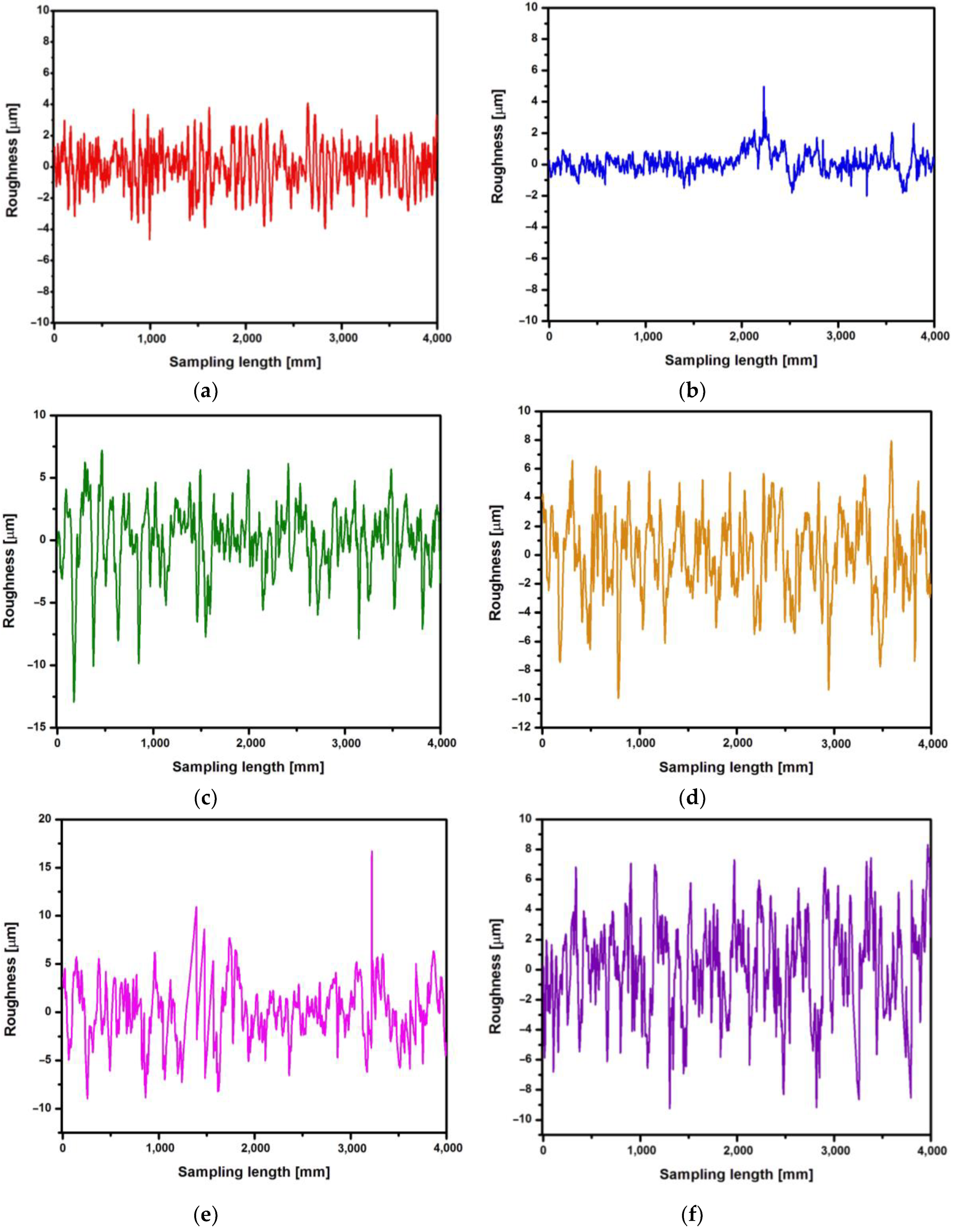

3.4. Surface Roughness Study

First, the roughness measurement was performed for the CpTi G4 surface before electrochemical oxidation, i.e. for the surface after mechanical grinding (

Figure 6a) and after electrochemical polishing (

Figure 6b). Then, roughness profiles were obtained for the CpTi G4 surface after anodizing at 20 V for 2, 18, 24 and 48 h (

Figure 6c-f).

Table 1 summarizes the obtained quantitative results of roughness measurements in the form of the arithmetic mean of the roughness profile ordinates (Ra), the highest height of the roughness profile (Rz) and the square mean of the profile ordinates (Rq) along with standard deviations for the CpTi G4 surface before and after electrochemical oxidation. Analyzing the results presented in

Table 1, it can be seen that the lowest value of the Ra parameter has the electrochemically polished CpTi G4 surface, which is more than half the value of the mechanically ground surface. The obtained results confirm the fact that the electropolished surface is much smoother, which is also confirmed by microscopic observations (

Figure 2a-b). The produced oxide layers are characterized by a much higher Ra parameter, as much as four or five times, compared to the surface of the CpTi G4 after electropolishing. This proves the formation of unevenness on the CpTi G4 surface in the form of a porous microstructure, the presence of which was confirmed by microscopic observations (

Figure 3). It can also be noticed that the longer the electrochemical oxidation time of the CpTi G4, the higher the value of the Ra parameter, which indicates an increasingly developed porous microstructure. A similar relationship applies to the Rq parameter, with one difference that the value of the Rq parameter increases up to an oxidation time of 24 hours and maintains the same level with an oxidation time of 24 and 48 hours. The value of the Rz parameter in the case of mechanical grinding is also half as high as in the case of an electropolished surface, and the highest Rz values were determined for the produced oxide layers.

The porous oxide layers produced under the proposed anodizing conditions contribute to increasing the surface roughness of CpTi G4. Moreover, the Ra parameter for the produced oxide layers takes values from the optimal range of 1 < Ra < 3, which is specified for dental implants [

4].

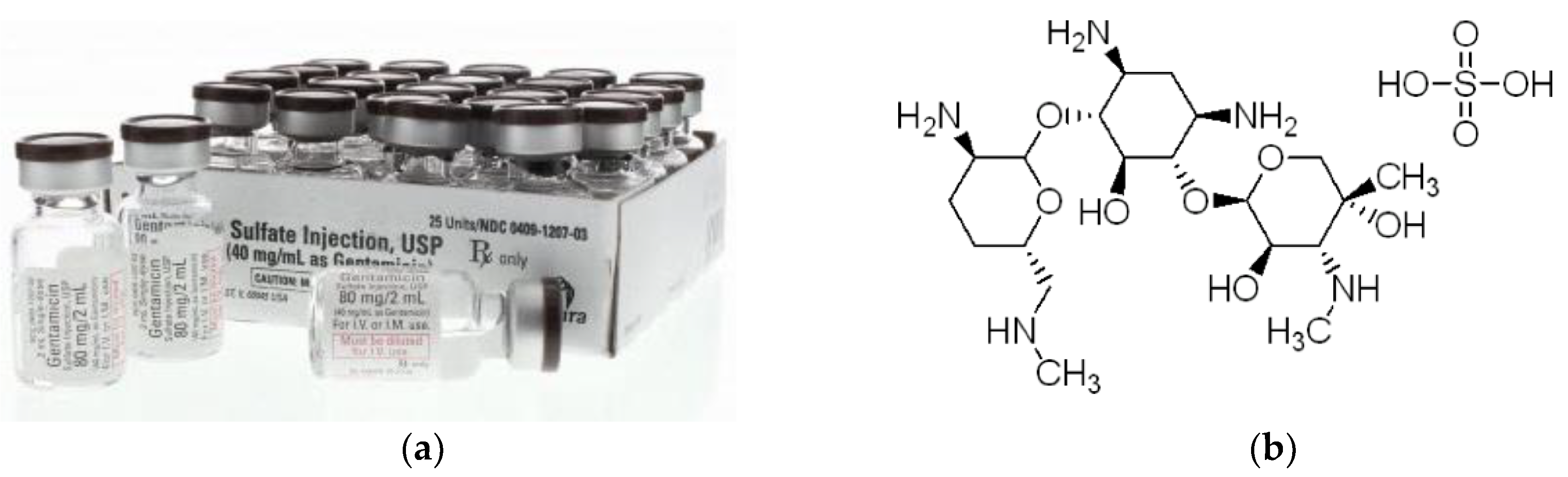

3.4. Release Kinetics of Gentamicin Sulfate from Porous Oxide Layers on CpTi G4

In order to use the produced oxide layers on the CpTi G4 surface as potential drug carriers, gentamicin sulfate commercially available was loaded into the pores (

Figure 7a) [

33]. The structure of gentamicin sulfate is shown in

Figure 7b [

34]. Gentamicin sulphate is a medicinal substance that belongs to the group of aminoglycoside antibiotics and has a bactericidal effect [

33,

34]. It is used in clinical practice in the case of infection of both hard tissues, bones and soft tissues, and prophylactically to prevent postoperative infections. The mechanism of action of gentamicin sulfate is to block the synthesis of bacterial proteins. Its action depends on the drug's penetration into the bacterial cell, where the ribosomes are located.

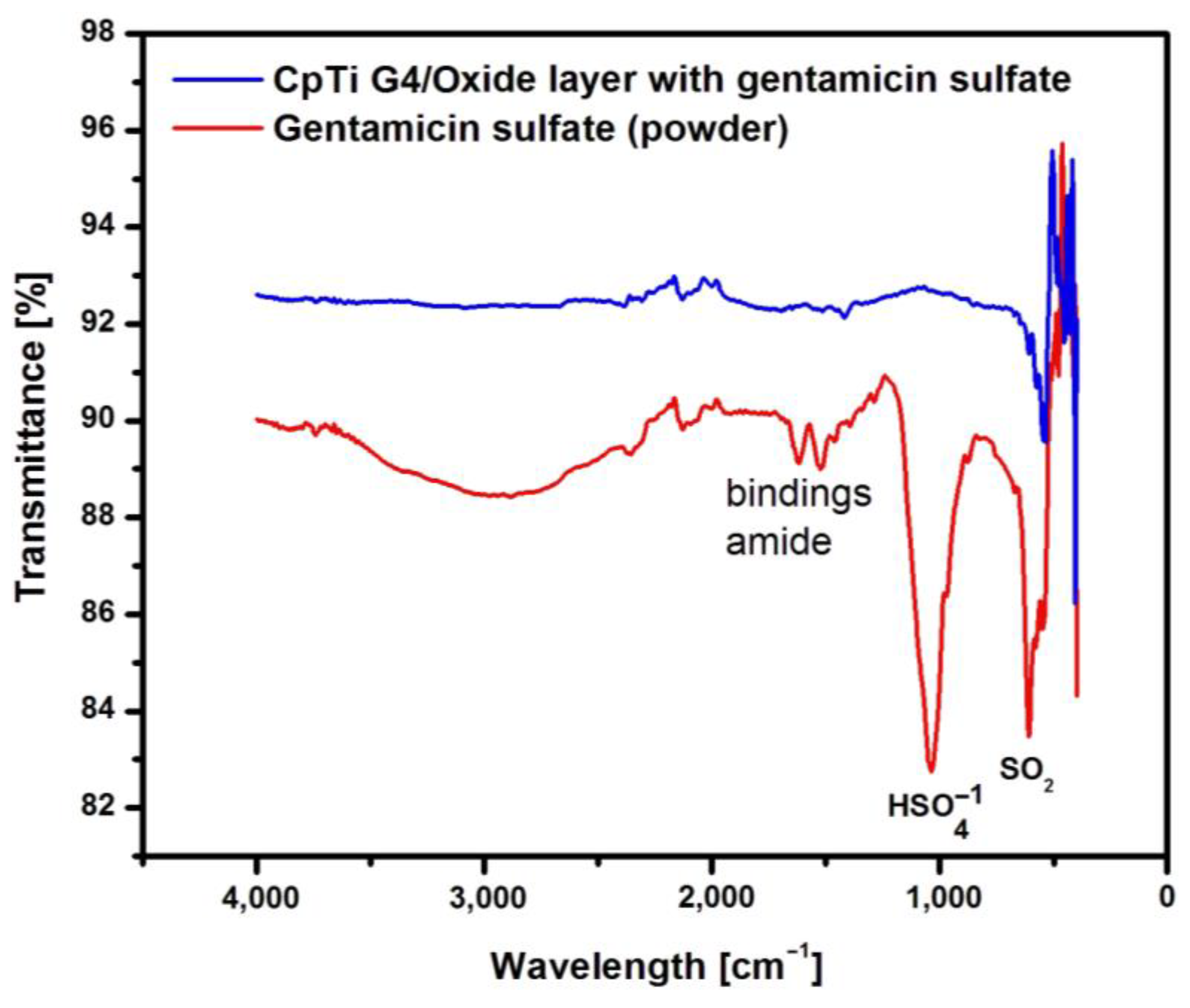

The presence of the loaded drug into porous oxide layers on the CpTi G4 surface was confirmed by measurements carried out using the ATR-FTIR method. ATR-FTIR tests were carried out on a sample of gentamicin sulfate in powder form, i.e. in the initial state, and on the CpTi G4 sample with porous oxide layers with the drug loaded.

Figure 8 shows an example ATR-FTIR spectrum for a porous oxide layer formed on the CpTi G4 surface in the electrochemical oxidation process at a voltage of 20 V for 48 hours with the loaded drug and, comparatively, for gentamicin sulfate powder.

Analysis of the ATR-FTIR spectrum for gentamicin sulfate in the form of powder shown in

Figure 8 showed the presence of absorption bands located at a wavelength of 1654 cm

−1, which indicates stretching vibrations of the amide bond of the C=O group, and deformation vibrations of the amide N-H group at 1531–1453 cm

−1 [

35]. There are also visible bonds originating from the I and II amide groups present in the drug at 1029 cm

−1 (

group) and 623 cm

−1 (SO

2 group).

The CpTi G4 sample after electrochemical oxidation with the drug loaded inside the porous microstructure of the oxide layer was also subjected to ATR-FTIR examination (

Figure 8). In this case, the ATR-FTIR spectrum showed the presence of an absorption band in the range of 1650–1453 cm

−1, which confirmed the implementation of gentamicin sulfate into the pores.

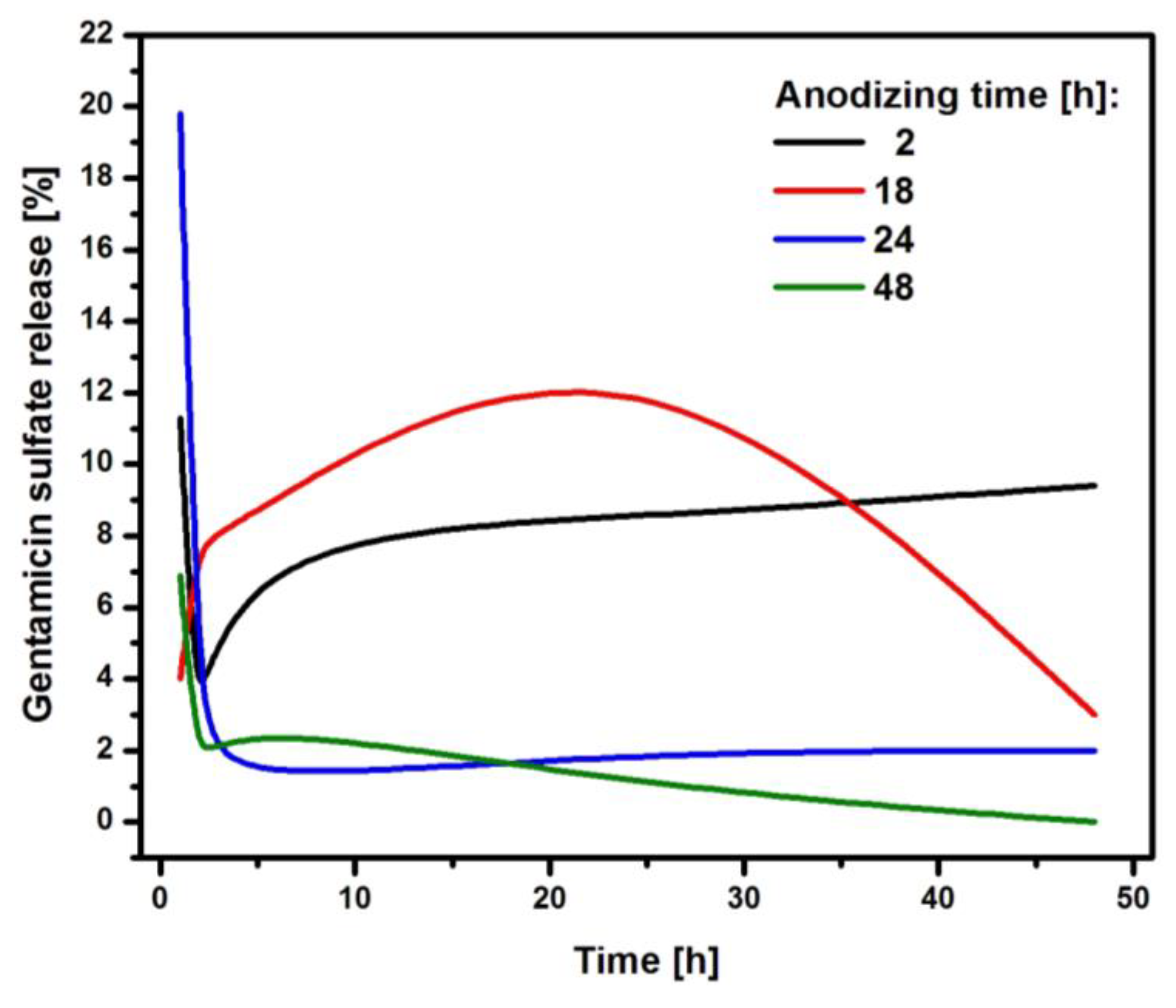

The CpTi G4 samples with porous oxide layers formed after all applied electrochemical oxidation times with loaded gentamicin sulfate were subjected to drug release kinetics examination using UV-VIS absorption spectroscopy.

Table 2 shows the amount of drug loaded into the pores depending on the anodizing time of the CpTi G4.

The data in

Table 2 show that as the anodizing time increases, and thus the film microstructure becomes more developed, the amount of drug loaded inside the pores decreases. Based on the resulting relationship and the appearance of the microstructure in the FE-SEM microscopic photos in

Figure 3a-d, it can be concluded that larger and more extensive pores are not conducive to drug loading.

The CpTi G4/Oxide layer samples after various anodizing times and loaded with the drug were subjected to a kinetics study of the release of gentamicin sulfate, which lasted 48 h. The obtained results were summarized in graphs showing the amount of the released drug as a function of the release time (

Figure 9).

After an anodizing time of 2 hours, the CpTi G4 sample released 11.3 % of the drug substance after the first hour, and then the released amount decreased to 1.2 % after the second hour. After this collapse, the amount of drug released increased again to 8 %, which was recorded after the third hour. This value stabilized and remained at a similar level until the end of the study, because after 24 hours the amount of drug released was 8.5 %, and at the end of the study, after 48 hours, it was 9.4 %. It can be concluded that the substance medicinal drug was released in a regular dose. The CpTi G4 sample anodized for 18 hours after the first hour released 4 % of the drug and this value increased until the 24 hours, when it amounted to 15 %. Then, a gradual decrease in the amount of substance released was noted until 48 hours, after which the amount of drug released was 3 %. The CpTi G4 sample, after anodizing for 24 hours after the first hour, showed the highest and most rapid release of the drug substance, which amounted to as much as 19.8 % of the drug loaded inside the pores. In the following hours, the amount of released drug substance stabilized at approximately 2 % and remained at this level until the end of the study. The CpTi G4 sample anodized for 48 hours released 6.9 % of the drug after the first hour and this value decreased to 1.1 % after the second hour. Then, after the third hour, there was a slight increase in the amount of drug released, which amounted to 3 %. After this time, the amount of drug released began to decrease again. After 24 hours it was only 1 %, and at the end of the study, i.e. after 48 hours, it was 0 %, which means that the drug stopped being released after that time.

Comparing the obtained results of drug release kinetics, it can be concluded that the CpTi G4 sample, which was electrochemically oxidized at a voltage of 20 V for 2 h, shows the most favorable course of the drug release process, because it stabilizes within the first three hours, after which the drug substance is released in a regular dose and in a controlled manner. Thanks to this, the oxide layer obtained under these anodizing conditions can be used in controlled drug delivery systems. Porous oxide layers obtained by anodizing for 24 and 48 hours tend to release the drug too suddenly and too quickly, which, unfortunately, does not have a positive effect on the controlled delivery of the drug substance. For this reason, it would be necessary to use an additional layer of an appropriate polymer that would slow down the drug release and stabilize it at one level. Based on the results obtained, it can be concluded that the medicinal substance in the form of gentamicin sulfate is released from the interior of the porous oxide layers formed on the CpTi G4 surface in accordance with Fick's first law [

35], which states that the amount of substance diffusing per unit of time through the surface perpendicular to the direction is directly proportional to the area of this surface and the concentration gradient of the substance in the system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.O. and B.Ł.; methodology, P.O. and B.Ł.; software, D.N. and P.O.; validation, D.N. and P.O.; formal analysis, D.N. and P.O.; investigation, D.N. and P.O.; resources, D.N. and P.O.; data curation, D.N. and P.O.; writing—original draft preparation, D.N.; writing—review and editing, P.O. and B.Ł.; visualization, D.N. and P.O.; supervision, B.Ł.