1. Introduction

The skin is the largest organ of mammals, accounting for approximately 15% of total body weight. It plays a fundamental role in maintaining homeostasis, protecting against external aggressors, thermoregulation, sensory perception, and immune defense [

1,

2]. Structurally, the skin is composed of three main layers—epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis—which provide a physical and biochemical barrier and support wound repair [

3,

4]. In veterinary medicine, wound healing is of relevance in post-surgical care, as it directly impacts patient recovery, infection risk, and overall prognosis [

5].

Wound healing is a dynamic and tightly regulated biological process that unfolds in three overlapping phases: inflammation, proliferation, and remodelling [

5,

6]. Each stage is coordinated through interactions between inflammatory cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, cytokines, and extracellular matrix components [

7,

8]. Several factors influence the quality and speed of healing, including tissue oxygenation, vascularization, pH, comorbidities, and hormonal status [

9,

10,

11]. Notably, recent studies have highlighted the importance of maintaining an acidic skin pH in preventing pathogen colonization and modulating enzyme activity essential for epidermal renewal [

17].

Photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT), particularly using Class IV therapeutic LASERs, has emerged as a promising tool in regenerative medicine. Class IV LASERs emit high-power infrared light (typically 780–980 nm), which penetrates deep into tissue, stimulating mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase and enhancing ATP production, cellular proliferation, collagen synthesis, and angiogenesis [

5,

12,

13]. These effects have been shown to positively modulate all stages of the healing process: reducing inflammation and oxidative stress in the initial phase, promoting fibroblast and keratinocyte migration and proliferation in the proliferative phase, and contributing to organized extracellular matrix remodelling during the final maturation phase [

6,

14,

15,

16].

Despite the growing body of literature supporting PBMT in both human and veterinary applications, studies focusing specifically on its use in companion animals, especially cats, remain limited. Moreover, there is a lack of controlled intraindividual comparisons assessing the differential healing response within the same subject and surgical site [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of Class IV therapeutic LASER application on surgical wound healing in Canis familiaris and Felis catus. Using a split-wound design, this preliminary study investigates intraindividual differences in healing parameters—such as suture thickness, skin colour, regional fluids, local temperature, and presence of hematoma—over an 8-day postoperative period. The findings contribute to the growing understanding of PBMT’s clinical utility in veterinary wound management and may support the development of standardized protocols for its use in small animal practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Animal Selection

This prospective, intra-individual, controlled study included 49 animals (n = 49), comprising 25 dogs (

Canis familiaris) and 24 cats (

Felis catus) of both sexes (27 females and 22 males) and various breeds. All animals were hospitalized at the “Centro de Medicina Veterinária Anjos de Assis” and underwent surgical procedures across multiple specialties. Each patient had a surgical incision evaluated, with one half of the wound treated with Class IV therapeutic laser (cranial section) and the other half left untreated (caudal section), serving as intra-subject control [

8,

9,

25].

Inclusion criteria were clinical stability, absence of active oncologic disease (current or past), and the ability to complete an 8-day postoperative follow-up. Written informed consent was obtained from all animal owners. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee (Ref. 015/2022).

2.2. Laser Treatment Protocol

Laser therapy was performed using a Class IV diode laser system (Doctor Vet Therapy Laser, LAMBDA®) with a combination of wavelengths (660, 808, and 915 nm) in continuous wave (CW) mode. The cranial portion of the incision was irradiated based on the estimated treatment area, as follows:

Post-op S: 5 cm2 area, 25 seconds, 2 W output, total energy 50 J;

Post-op M: 25 cm2 area, 2 min 5 s, 2 W output, total energy 250 J;

Post-op L: 50 cm2 area, 4 min 10 s, 2 W output, total energy 500 J.

Frequencies used included CW, 1, 2, 10, and 25 kHz, with distinct purposes:

1 kHz: epithelialization;

2 kHz: fibroblast stimulation;

10 kHz: infection control;

25 kHz: antimicrobial effect.

Each area was irradiated with at least two passes of the laser beam to ensure homogeneous energy delivery.

2.3. Evaluation Parameters and Timeline

The surgical suture line of each patient was divided into two equal parts:

Three postoperative timepoints were used for evaluation:

Wound healing was assessed using a validated scoring system adapted from Vitor & Carreira (2015) [

23], which included the following clinical parameters: temperature, skin colour, hematoma, fluid presence, and suture thickness. All evaluations were performed by the same investigator to minimize variability and ensure consistency.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data was recorded in Microsoft Excel and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29 (Windows). Descriptive statistics included means, standard deviations, and frequencies. Data normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variance via Levene’s test. Inferential statistics included:

Repeated Measures ANOVA, to assess intra-group changes over time for normally distributed variables;

Student’s t-test for independent samples: used when assumptions of normality and homogeneity were met;

Mann–Whitney U test, applied for non-normally distributed variables;

Fisher’s exact test, used for categorical associations with low frequency outcomes;

Cochran’s Q test for repeated binary outcomes across time.

Categorical variables were converted to binary (dummy) variables for statistical modelling. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characterization

The total sample consisted of 49 animals, of which 51% (n = 25) were

Canis familiaris (dogs) and 49% (n = 24) were

Felis catus (cats). Female animals represented 55.1% of the total sample. Most of the animals were neutered (67.3%), with higher prevalence in cats (83.3%) compared to dogs (52.0%). The mean age was 6.90 ± 4.30 years across all animals, 6.82 ± 4.64 years in dogs, and 7.13 ± 4.18 years in cats. Regarding body weight, dogs showed a higher average (17.50 ± 12.57 kg) than cats (4.27 ± 1.20 kg). The most frequent body condition score, based on the 9-point LaFlamme scale, was 6 in both species. Full descriptive data is presented in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Age, Body Weight, Sex, Body Condition Score, and Reproductive Status.

Table 1.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Age, Body Weight, Sex, Body Condition Score, and Reproductive Status.

| Parameters |

Total Sample (N = 49) |

Dog (n = 25) |

Cat (n = 24) |

| Age (years) |

6.90 ± 4.3% |

6.82 ± 4.6% |

7.13 ± 4.2% |

| Body Weight (Kg) |

12.00 ± 11.6% |

17.50 ± 12.6% |

4.27 ± 1.2% |

| Sex (Female) |

27 (55.1%) |

15 (60.0%) |

12 (50.0%) |

| Sex (Male) |

22 (44.9%) |

10 (40.0%) |

12 (50.0%) |

| Body Condition Score (1-9) |

Score 1: 2 ± 4.7% |

Score 1: 1 ± 4.5% |

Score 1: 1 ± 4.8% |

| |

Score 2: 4 ± 9.3% |

Score 2: 2 ± 9.1% |

Score 2: 2 ± 9.5% |

| |

Score 3: 3 ± 7.0% |

Score 3: 1 ± 4.5% |

Score 3: 2 ± 9.5% |

| |

Score 4: 7 ± 16.3% |

Score 4: 5 ± 22.7% |

Score 4: 2 ± 9.5% |

| |

Score 5: 10 ± 23.3% |

Score 5: 5 ± 22.7% |

Score 5: 5 ± 23.8% |

| |

Score 6: 11 ± 25.6% |

Score 6: 6 ± 27.3% |

Score 6: 5 ± 23.8% |

| |

Score 7: 4 ± 9.3% |

Score 7: 1 ± 4.5% |

Score 6: 6 ± 27.3% |

| |

Score 8: 2 ± 4.7% |

Score 8: 1 ± 4.5% |

Score 6: 6 ± 27.3% |

| Reproductive Status (Neutered) |

33 (67.3%) |

13 (52.0%) |

20 (83.3%) |

| Reproductive Status (Intact) |

16 (32.7%) |

12 (48.0%) |

4 (16.7%) |

3.2. Wound Healing Parameters

All parameters were assessed at five timepoints: T0 (immediate post-surgery), T1 SL (48 h without LASER), T1 CL (48 h with LASER), T2 SL (8 days without LASER), and T2 CL (8 days with LASER). The analysis was performed on the total sample, and separately for dogs and cats.

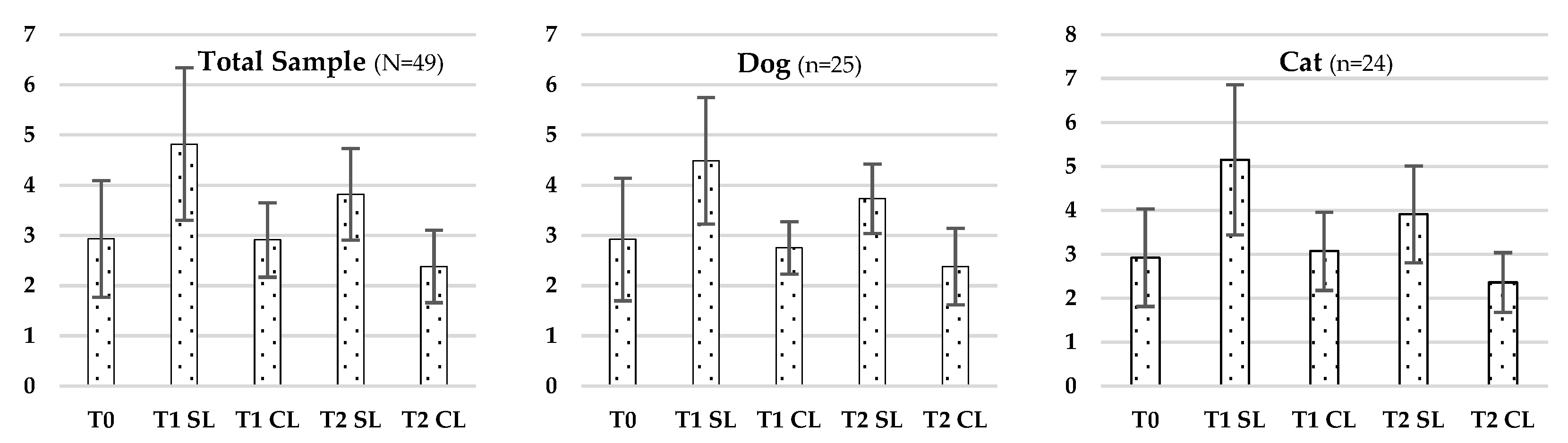

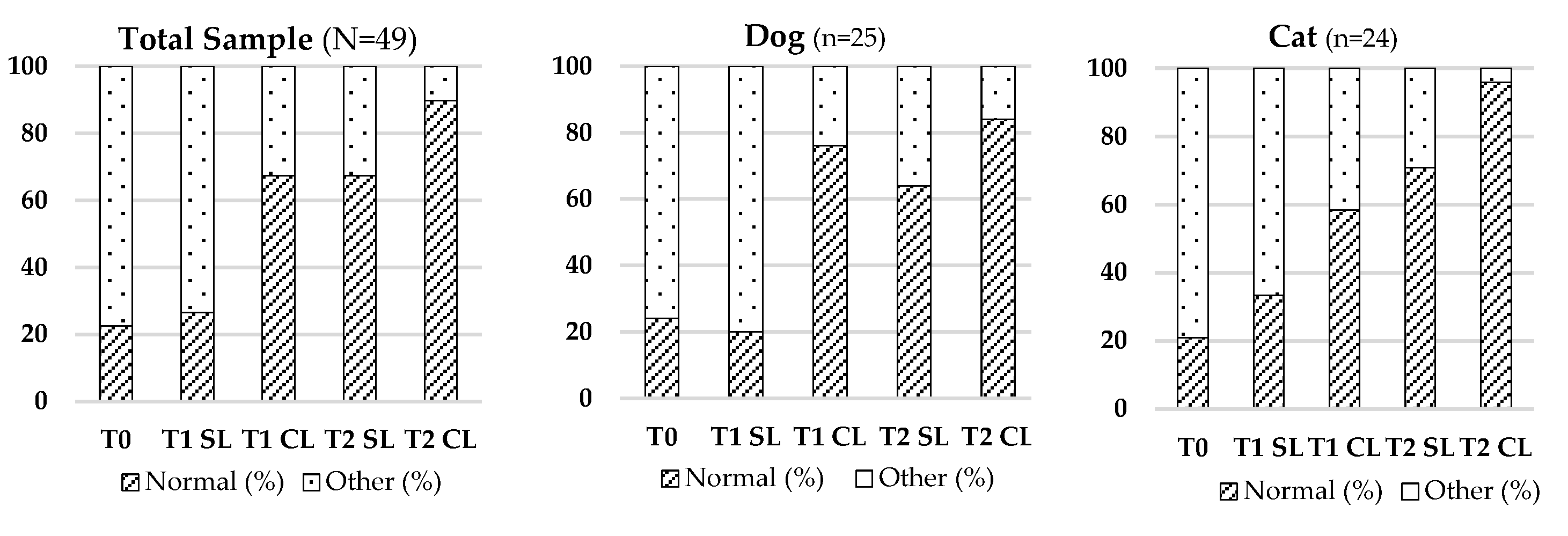

3.2.1. Skin Thickness

Statistically significant differences in skin thickness were observed across all timepoints in the Total Sample (F (4.192) = 80.008; p < 0.001), in dogs (F (4.21) = 17.756; p < 0.001) and cats (F (4.20) = 37.707; p < 0.001), as analysed by repeated-measures ANOVA. Post-op comparisons (Cochran’s test) revealed multiple significant differences between treatment conditions and timepoints. Full data are summarized in

Table 2 and

Figure 1.

Table 2.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Skin Thickness.

Table 2.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Skin Thickness.

| Evaluation Moment |

Total Sample (N = 49) |

Dog (n = 25) |

Cat (n = 24) |

| T0 |

2.93 ± 1.16% |

2.92 ± 1.22% |

2.92 ± 1.11% |

| T1 SL |

4.82 ± 1.52% |

4.49 ± 1.26% |

5.15 ± 1.71% |

| T1 CL |

2.91 ± 0.74% |

2.75 ± 0.52% |

3.07 ± 0.89% |

| T2 SL |

3.82 ± 0.91% |

3.73 ± 0.69% |

3.91 ± 1.10% |

| T2 CL |

2.38 ± 0.72% |

2.38 ± 0.76% |

2.36 ± 0.68% |

Figure 1.

Evolution of Skin Thickness in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

Figure 1.

Evolution of Skin Thickness in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

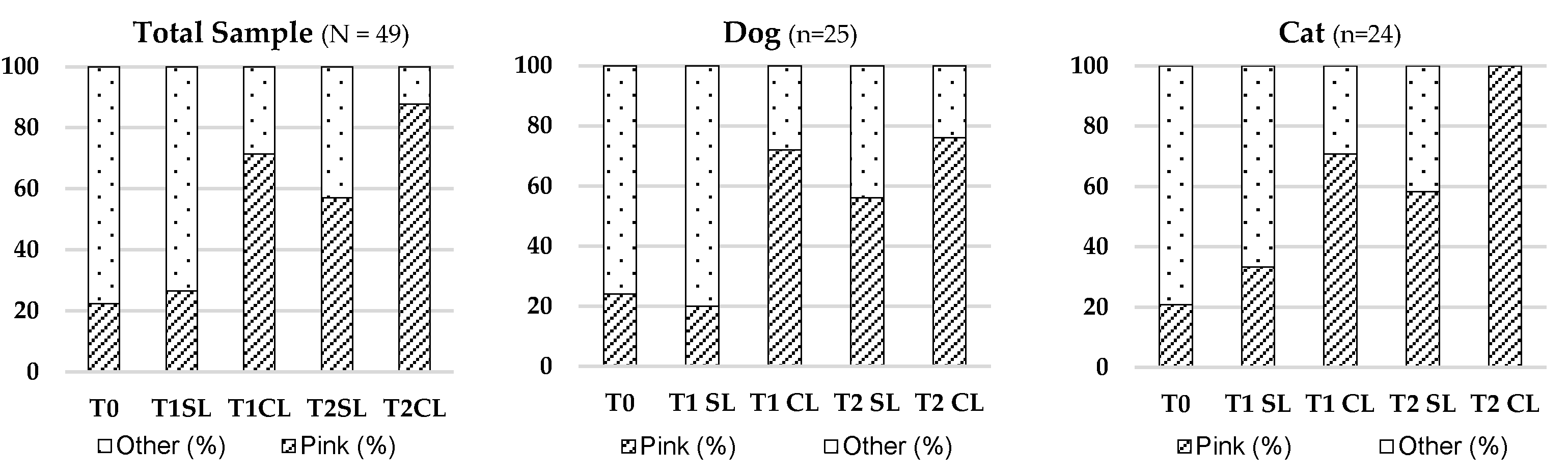

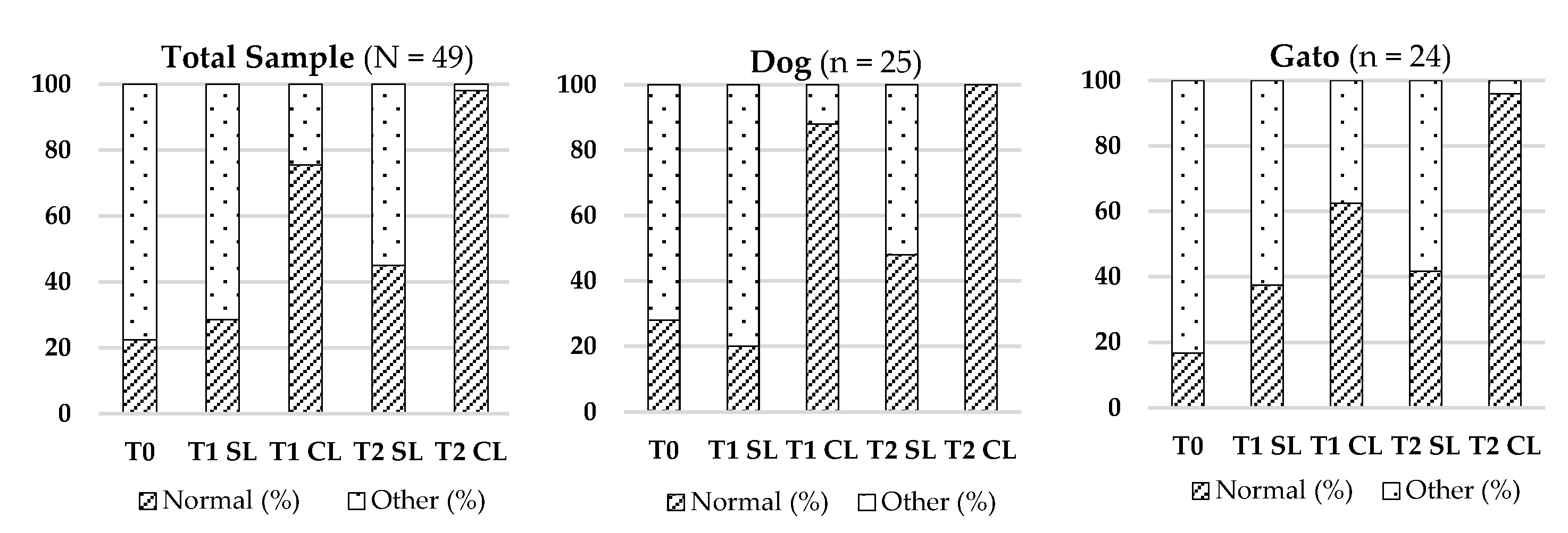

3.2.2. Skin Colour

Significant changes in skin colour were also detected (Cochran’s Q test), both in the Total Sample (χ

2 (4) = 59.535; p < 0.001) and by species. Improved normalization of skin colour (pinkish hue) was notably more frequent at T2 CL. Detailed results are illustrated in

Table 3 and

Figure 2.

Table 3.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Skin Coloration (%Normal / %Altered).

Table 3.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Skin Coloration (%Normal / %Altered).

| Evaluation Moment |

Total Sample (N = 49) |

Dog (n = 25) |

Cat (n = 24) |

| T0 |

22.4 / 77.6 |

24.0 / 76.0 |

20.8 / 79.2 |

| T1 SL |

26.5 / 73.5 |

20.0 / 80.0 |

33.3 / 66.7 |

| T1 CL |

69.4 / 30.6 |

76.0 / 24.0 |

62.5 / 37.5 |

| T2 SL |

79.6 / 20.4 |

72.0 / 28.0 |

87.5 / 12.5 |

| T2 CL |

95.9 / 4.1 |

96.0 / 4.0 |

95.8 / 4.2 |

Figure 2.

Evolution of Skin Colour in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

Figure 2.

Evolution of Skin Colour in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

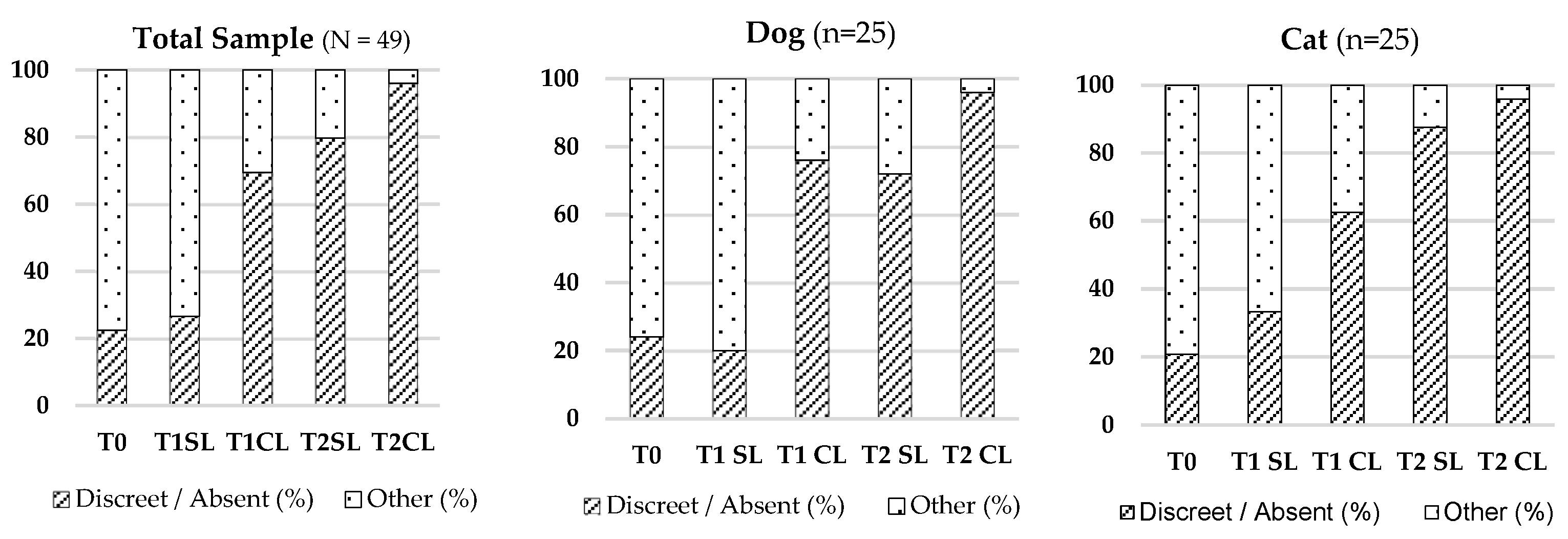

3.2.3. Presence of Haematoma

There was a significant reduction in hematoma presence across timepoints in the Total Sample (χ

2 (4) = 77.353; p < 0.001), dogs (χ

2 (4) = 41.941; p < 0.001), and cats (χ

2 (4) = 38.038; p < 0.001). The most marked reduction was seen at T2 CL. See

Table 4 and

Figure 3 for visualization.

Table 4.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Presence of Hematoma (% Discrete or Absent/ % Evident).

Table 4.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Presence of Hematoma (% Discrete or Absent/ % Evident).

| Evaluation Moment |

Total Sample (N = 49) |

Dog (n = 25) |

Cat (n = 24) |

| T0 |

22.4 / 77.6 |

24.0 / 76.0 |

20.8 / 79.2 |

| T1 SL |

26.5 / 73.5 |

20.0 / 80.0 |

33.3 / 66.7 |

| T1 CL |

69.4 / 30.6 |

76.0 / 24.0 |

62.5 / 37.5 |

| T2 SL |

79.6 / 20.4 |

72.0 / 28.0 |

87.5 / 12.5 |

| T2 CL |

92.9 / 4.1 |

96.0 / 4.0 |

95.8 / 4.2 |

Figure 3.

Evolution of Presence of Hematoma in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

Figure 3.

Evolution of Presence of Hematoma in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

3.2.4. Regional Temperature

Significant variations in regional temperature were observed across timepoints in the Total Sample (χ

2 (4) = 86.188; p < 0.001), dogs (χ

2 (4) = 53.438; p < 0.001), and cats (χ

2 (4) = 36.750; p < 0.001), with normalization more prominent in the LASER-treated area at T2. Refer to

Table 5 and

Figure 4.

Table 5.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Regional Temperature (% Normal/ % Other).

Table 5.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Regional Temperature (% Normal/ % Other).

| Evaluation Moment |

Total Sample (N = 49) |

Dog (n = 25) |

Cat (n = 24) |

| T0 |

22.5 / 77.6 |

24.0 / 76.0 |

20.8 / 79.2 |

| T1 SL |

30.6 / 69.4 |

24.0 / 76.0 |

37.5 / 62.5 |

| T1 CL |

71.4 / 28.6 |

84.0 / 16.0 |

58.3 / 41.8 |

| T2 SL |

87.8 / 12.2 |

88.0 / 12.0 |

87.5 / 12.5 |

| T2 CL |

98.0 / 2.0 |

100.0 / 0.0 |

95.8 / 4.2 |

Figure 4.

Evolution of Regional Temperature in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

Figure 4.

Evolution of Regional Temperature in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

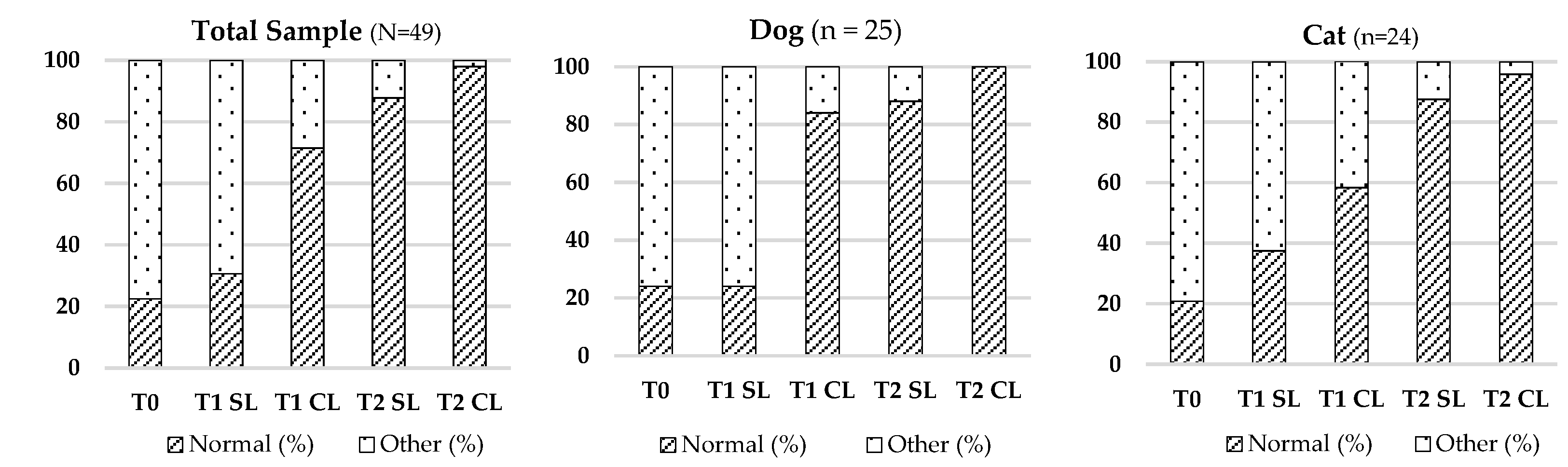

3.2.5. Skin Elasticity

Skin elasticity improved significantly over time in all groups, particularly after LASER application. These changes were confirmed by Cochran’s Q test (Total Sample: χ

2 (4) = 32.046; p < 0.001). Complete results are shown in

Table 6 and

Figure 5.

Table 6.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Skin Elasticity (% Normal/ % Other).

Table 6.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Skin Elasticity (% Normal/ % Other).

| Evaluation Moment |

Total Sample (N = 49) |

Dog (n = 25) |

Cat (n = 24) |

| T0 |

22.5 / 77.6 |

24.0 / 76.0 |

20.8 / 79.2 |

| T1 SL |

26.5 / 73.5 |

20.0 / 80.0 |

33.3 / 66.7 |

| T1 CL |

67.4 / 32.7 |

76.0 / 24.0 |

58.3 / 41.7 |

| T2 SL |

67.4 / 32.7 |

64.0 / 36.0 |

70.8 / 29.2 |

| T2 CL |

89.8 / 10.2 |

84.0 / 16.0 |

95.8 / 4.2 |

Figure 5.

Evolution of Skin Elasticity in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

Figure 5.

Evolution of Skin Elasticity in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

3.2.6. Presence of Fluids

There was a statistically significant reduction in fluid presence in all groups over time (Total Sample: χ

2 (4) = 73.508; p < 0.001). Near-complete resolution was observed at T2 CL. See

Table 7 and

Figure 6 for graphical data.

Table 7.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Presence of Fluids (% Normal/ % Other).

Table 7.

Characterization of the Total Sample (N = 49) and the two species groups considered in the study — Dog (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cat (Felis catus, n = 24) — regarding Presence of Fluids (% Normal/ % Other).

| Evaluation Moment |

Total Sample (N = 49) |

Dog (n = 25) |

Cat (n = 24) |

| T0 |

22.5 / 77.6 |

28.0 / 72.0 |

16.7 / 83.3 |

| T1 SL |

28.6 / 71.4 |

20.0 / 80.0 |

37.5 / 62.5 |

| T1 CL |

75.5 / 24.5 |

88.0 / 12.0 |

62.5 / 37.5 |

| T2 SL |

44.9 / 55.1 |

48.0 / 52.0 |

41.7 / 58.3 |

| T2 CL |

98.0 / 2.0 |

100.0 / 0.0 |

95.8 / 4.2 |

Figure 6.

Evolution of Presence of Fluids in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

Figure 6.

Evolution of Presence of Fluids in the Total Sample (N = 49), Dogs (n = 25), and Cats (n = 24) across Different Evaluation Timepoints (T0, T1, T2), Considering LASER-Treated (CL) and Untreated (SL) Regions.

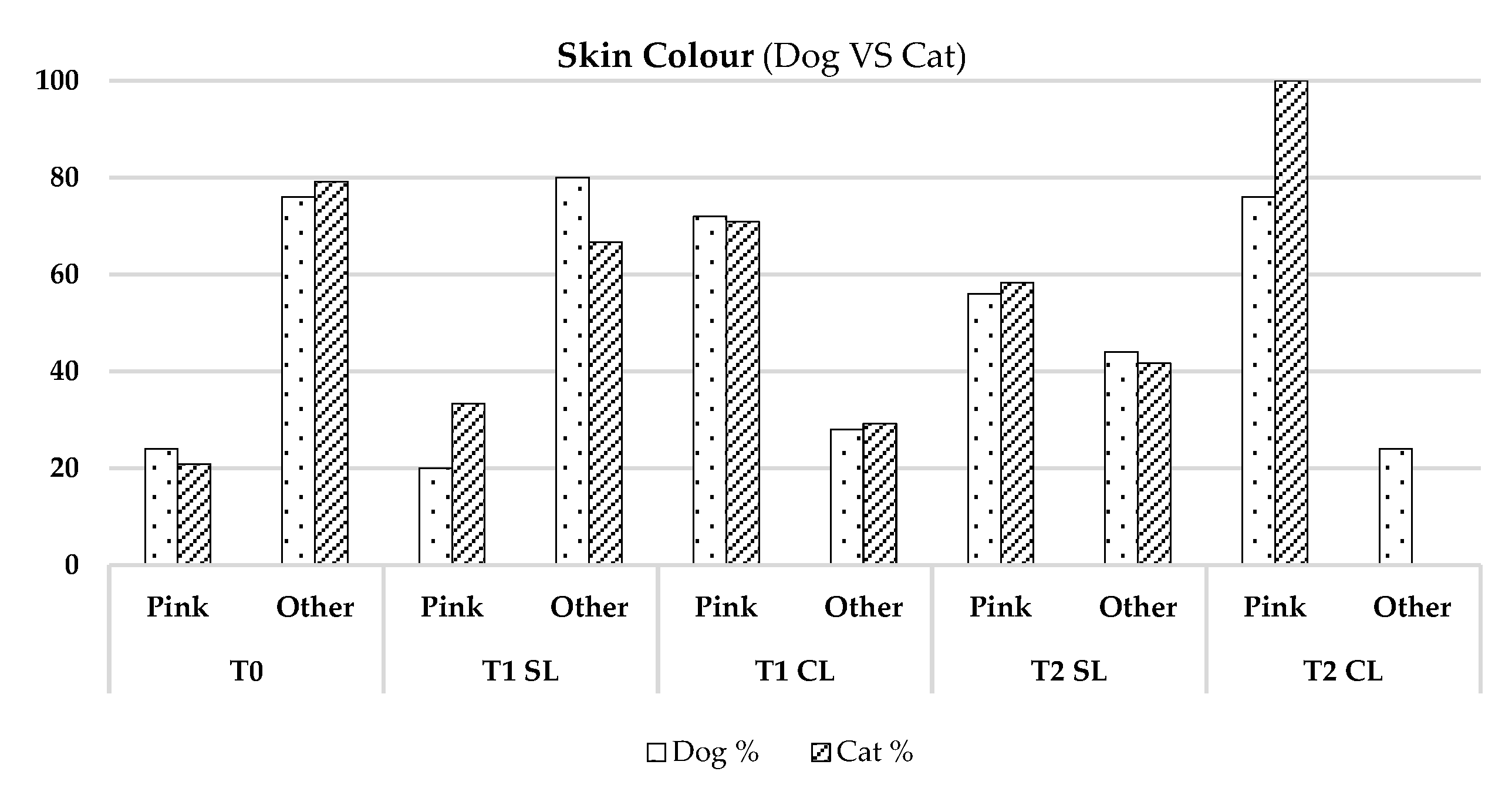

3.3. Inter-Species Comparison (Dogs VS Cats)

No significant differences in most parameters between dogs and cats, except for higher pink coloration in cats at T2 CL (p-value = 0.022) [

19]. Results are presented in

Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison between Dogs (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cats (Felis catus, n = 24)—regarding the Parameter: Skin Colour.

Figure 7.

Comparison between Dogs (Canis familiaris, n = 25) and Cats (Felis catus, n = 24)—regarding the Parameter: Skin Colour.

3.4. Influence of Age, Sex, and Body Condition

No age or sex differences were found for skin thickness or elasticity.

Logistic regression indicated that sex was a significant predictor for pinkish skin colour in the untreated area (SL) (p = 0.014), with females more likely to present normal colour. No significant predictors were identified for the treated area (CL) (

Table 8) [

7,

20].

Table 8.

Logistic regression statistics illustrating the influence of age, gender and body condition on skin colouring.

Table 8.

Logistic regression statistics illustrating the influence of age, gender and body condition on skin colouring.

| Parameters / Coefficient |

B |

SD |

Wald |

df |

p-value |

| |

Gender |

-1,421 |

0,881 |

2,601 |

1 |

0,107 |

| SL |

Body Condition |

0,570 |

0,254 |

5,053 |

1 |

0,025 |

| |

Age |

0,001 |

0,106 |

0,000 |

1 |

0,993 |

| |

Gender |

-18,911 |

876,77 |

0,000 |

1 |

0,998 |

| CL |

Body Condition |

-0,040 |

0,477 |

0,007 |

1 |

0,933 |

| |

Age |

0,032 |

0,210 |

0,023 |

1 |

0,880 |

In the SL area, body condition score was a significant predictor (p = 0.025), with worse condition associated with fewer visible hematomas. No significant effects were found in the CL area. Results are detailed in

Table 9 [

14,

20].

Table 9.

Logistic regression statistics illustrating the influence of age, gender and body condition on the parameter: Presence of Haematomas.

Table 9.

Logistic regression statistics illustrating the influence of age, gender and body condition on the parameter: Presence of Haematomas.

| Parameters / Coefficient |

B |

SD |

Wald |

df |

p-value |

| |

Gender |

1,764 |

0,719 |

6,024 |

1 |

0,014 |

| SL |

Body Condition |

0,367 |

0,222 |

2,864 |

1 |

0,091 |

| |

Age |

0,016 |

0,089 |

0,031 |

1 |

0,859 |

| |

Gender |

0,600 |

0,985 |

0,371 |

1 |

0,543 |

| CL |

Body Condition |

-0,114 |

0,298 |

0,147 |

1 |

0,701 |

| |

Age |

-0,091 |

0,124 |

0,541 |

1 |

0,462 |

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the therapeutic effects of Class IV LASER therapy on the healing process of post-surgical wounds in dogs and cats. The sample included 49 animals of varying ages, sex, weight, and body condition, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the biological effects of photobiomodulation using Class IV laser. The experimental design considered each animal as its own control. Each surgical incision was divided into two distinct anatomical zones: one treated with Class IV laser therapy (CL) and one left untreated (SL). This intraindividual approach isolated the independent variable (laser treatment), ensuring that all other intrinsic and extrinsic variables remained constant. This design substantially increased control over confounding factors, reducing bias and providing higher internal validity and statistical robustness to the findings. This model is aligned with other studies that advocate for intraindividual experimental designs, such as the “split wound” model, which is recognized as a gold standard for evaluating the effects of specific parameters in clinical trials [

1,

2,

3,

4,

8,

15,

16,

18].

Skin thickness significantly decreased in the laser-treated areas (CL) across all time comparisons, indicating not only a lower local inflammatory response but also reduced extracellular matrix (ECM) density. During the inflammatory phase, vasodilation and increased vascular permeability facilitate immune cell infiltration and protein extravasation, leading to localized swelling. The progression into the proliferative phase is characterized by reduced inflammation, granulation tissue formation, and fibroblast proliferation. Class IV laser therapy accelerates this transition by modulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β) and increasing anti-inflammatory mediators like IL-10 [

5,

25]. Furthermore, laser stimulation activates cytochrome C oxidase in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, enhancing ATP production and cellular metabolism. This bioenergetic effect promotes fibroblast proliferation, collagen type III synthesis, and differentiation into myofibroblasts, which support wound contraction and tissue remodelling [

5,

6]. The action of growth factors such as TGF-β, FGF, and IGF is enhanced following laser exposure, contributing to the observed reduction in skin thickness as a marker of rapid and efficient healing.

No significant differences in skin thickness were observed between dogs and cats, or across different ages and sexes, indicating that the laser consistently modulated healing mechanisms regardless of physiological profile. While estrogens typically promote tissue regeneration by enhancing epidermal thickness, vascularization, and collagen synthesis, and androgens suppress these processes [

7,

8,

11], the uniform effect observed here suggests that laser therapy can override baseline hormonal differences.

Skin coloration, an indicator of vascular perfusion and oxygenation, was visibly improved in the CL areas, especially at T2, which corresponds with the proliferative phase peak. This phase involves angiogenesis mediated by VEGF, FGF, and TGF-β [

9,

27]. Class IV laser therapy enhances angiogenesis by increasing ATP and VEGF expression in endothelial and fibroblast cells, leading to improved vascularization and more vibrant skin coloration. This angiogenic effect was more prominent in cats, possibly due to their thinner epidermis, lower subcutaneous fat, and more superficial vascular networks, facilitating better light absorption [

10].

In untreated zones (SL), females showed more pronounced pinkish coloration than males, likely due to estrogenic-mediated vasodilation and angiogenesis. However, in laser-treated areas (CL), this gender difference disappeared, suggesting that the laser-induced vascular response compensated for hormonal variability. The involvement of ROS and mitochondrial pathways (especially cytochrome C oxidase) likely contributed to the increased VEGF expression and vascular homogeneity.

Hematoma resolution was notably faster in CL areas, reflecting more effective inflammation control and vascular repair. Laser therapy is thought to stimulate lymphatic drainage, nitric oxide release, and endothelial stabilization. These effects facilitate macrophage recruitment, erythrocyte phagocytosis, and degradation of extravascular haemoglobin [

11,

12,

24,

27]. ROS-mediated signalling and cytochrome C oxidase activation also reduce capillary permeability and enhance macrophage activity [

4,

6,

12,

24]. Although sex hormones affect vascular fragility, the laser’s modulatory effects likely overrode these influences, promoting consistent hematoma resolution across groups. Interestingly, animals with higher body condition scores exhibited prolonged hematoma presence in SL areas, possibly due to greater subcutaneous fat and associated vascular fragility. Yet, this difference was mitigated in CL areas, where the laser’s anti-inflammatory and lymphatic activation effects were effective.

Skin temperature increased significantly over time in CL regions, consistent with the metabolic activation induced by laser therapy. Enhanced mitochondrial function leads to ATP production, vasodilation, and improved perfusion—key indicators of active tissue repair [

4,

6,

13]. These effects, absent in SL areas and unaffected by sex, age, or species, further support the uniform physiological response elicited by Class IV laser.

Elasticity, a biomechanical marker of ECM quality, improved significantly in laser-treated areas. The synthesis of collagen types I and III, elastin, and fibronectin was stimulated by ATP and fibroblast activation, improving tissue resilience [

14,

23]. Laser therapy also regulates MMPs and TIMPs, ensuring balanced ECM remodelling [

13,

15]. While estrogens enhance elasticity and androgens impair it, these hormonal effects were neutralized by laser-induced fibroblast stimulation and ECM regulation, resulting in homogeneous outcomes.

Finally, the presence of regional fluids, including lymphatic and serosanguinous exudate, decreased more rapidly in CL areas. This improvement was attributed to enhanced endothelial and lymphatic recovery via cytochrome C oxidase activation and ATP-driven cellular function [

4,

6,

16,

26]. Ion channel activity and aquaporin regulation facilitated interstitial fluid reabsorption, supported by decreased histamine release due to reduced inflammatory cytokine expression [

14,

17,

23,

27]. The resulting vascular stabilization and reactivation of lymphatic flow created a more favourable wound environment. The laser’s robust effect, unaffected by species, sex, or age, highlights its broad therapeutic applicability in surgical wound management.

5. Conclusions

This preliminary study demonstrated that Class IV laser therapy significantly enhances the post-surgical wound healing process in dogs and cats. The intraindividual design enabled a controlled evaluation of the photobiomodulation effects, showing consistent benefits across various physiological profiles regardless of species, age, or sex. Laser-treated regions (CL) presented faster resolution of inflammation, reduced skin thickness, improved elasticity, enhanced vascularization, and more efficient fluid drainage compared to untreated regions (SL). These findings suggest that Class IV laser therapy is a promising, non-invasive adjunct for improving wound healing outcomes in veterinary practice.

Further studies with larger sample sizes and long-term follow-up are recommended to confirm these results and to better elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed clinical effects.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AL, PA and LMC; Methodology: AL, PA and LMC.; Software, AL.; Validation: AL, PA and LMC; Formal Analysis: AL.; Investigation: AL, PA and LMC; Resources: AL, PA and LMC; Data Curation: AL, PA and LMC.; Writing—original draft preparation: AL; Writing—review and editing: AL, PA and LMC, Visualization: AL, PA and LMC; Supervision: LMC; Project Administration, AL and LMC; Funding Acquisition, LMC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Research and Teaching of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine — University of Lisbon under reference 015/2022

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Interdisciplinary Centre of Research in Animal Health (CIISA), Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Lisbon, 1300-477 Lisbon, Portugal; and to Anjos of Assis Veterinary Medicine Centre (CMVAA), 2830-077 Barreiro, Portugal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECM |

Extracellular Matrix |

| CL |

Cranial LASER-treated area |

| SL |

Caudal non-treated area |

| ATP |

Adenosine Triphosphate |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| NO |

Nitric Oxide |

| VEGF |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| FGF |

Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| TGF-β

|

Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| IL-1β

|

Interleukin 1 Beta |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin 10 |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| MMP |

Matrix Metalloproteinase |

| TIMP |

Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase |

| T0, T1, T2 |

Timepoints: immediately post-op, 48h, day 8 |

| PBMT |

Photobiomodulation Therapy |

| IGF |

Insulin-like Growth Factor |

References

- Junqueira, L.C.; Carneiro, J. Histologia Básica, 12th ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hyttel, P.; Sinowatz, F.; Vejlsted, M. Embriologia Veterinária; Elsevier: Rio de Janeiro, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B. Dyce, Sack, and Wensing’s Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy, 5th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zachary, J.F.; McGavin, M.D. Bases da Patologia em Veterinária, 5th ed.; Elsevier: São Paulo, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J.R. Current Concepts in Wound Management and Wound Healing Products. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2015, 45, 537–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, H.N.; Hardman, M.J. Wound Healing: Cellular Mechanisms and Pathological Outcomes. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eming, S.A.; Wynn, T.A.; Martin, P. Inflammation and Metabolism in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Science 2017, 356, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enwemeka, C.S.; Parker, J.C.; Dowdy, D.S.; Harkness, E.E.; Harkness, L.E.; Woodruff, L.D. The Efficacy of Low-Power Lasers in Tissue Repair and Pain Control: A Meta-Analysis Study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2004, 22, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltese, G.; Karalliedde, J.; Rapley, H.; Amor, T.; Lakhani, A.; Gnudi, L. A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Class IV Lasers on Nonhealing Neuroischemic Diabetic Foot Ulcers in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, e152–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choung, H.-W.; et al. Effectiveness of Low-Level Laser Therapy with a 915 Nm Wavelength Diode Laser on the Healing of Intraoral Mucosal Wound. Medicina 2019, 55, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özer, H.; İnci, M.A. Effect of Low-Level Laser Therapy in Wound Healing of Primary Molar Teeth Extraction. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; et al. The Nuts and Bolts of Low-Level Laser (Light) Therapy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Sen, C.K. miRNA in Wound Inflammation and Angiogenesis. Microcirculation 2012, 19, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorg, H.; Sorg, C.G.G. Skin Wound Healing: Of Players, Patterns, and Processes. Eur. Surg. Res. 2023, 64, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boixeda, P.; Calvo, M.; Bagazgoitia, L. Recent Advances in Laser Therapy and Other Technologies. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018, 99, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.S.; Stephens, B.J. Veterinary Laser Therapy in Small Animal Practice; 5m Books: Great Easton, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schreml, S.; et al. The Impact of the pH Value on Skin Integrity and Cutaneous Wound Healing. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2010, 24, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaac, C.; et al. Processo de Cura das Feridas: Cicatrização Fisiológica. Rev. Med. 2010, 89, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, H.A.; Marsella, R. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Dermatology, 3rd ed.; BSAVA: Gloucester, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guillamat-Prats, R. The Role of MSC in Wound Healing, Scarring and Regeneration. Cells 2021, 10, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, C.J.; Miller, L.A. (Eds.) Laser Therapy in Veterinary Medicine – Photobiomodulation; Wiley: New Jersey, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. The Quantum Theory of Radiation. Phys. Z. 1917, 18, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J.P.; Zeiger, H.J.; Townes, C.H. Molecular Microwave Oscillator and New Hyperfine Structure in the Microwave Spectrum of NH3. Phys. Rev. 1954, 95, 282–284. [Google Scholar]

- Maiman, T.H. Stimulated Optical Radiation in Ruby. Nature 1960, 187, 493–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitor, M. Proposta de uma Escala para Avaliação do Processo de Cicatrização de Ferida Cirúrgica no Cão e Gato. Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler, T.W. Langman’s Medical Embryology, 12th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Capon, A.; Mordon, S. Can Thermal Lasers Promote Skin Wound Healing? Lille University Hospital, 2003.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).